Learning phonic sounds

Phonics teaching step-by-step | TheSchoolRun

Sort your phonemes from your graphemes, decoding from encoding and digraphs from trigraphs with our parents' guide to phonics teaching. Our step-by-step explanation takes you through the different stages of phonics learning, what your child will be expected to learn and the vocabulary you need to know.

or Register to add to your saved resources

What is phonics?

Phonics is a method of teaching children to read by linking sounds (phonemes) and the symbols that represent them (graphemes, or letter groups). Phonics is the learning-to-read method used in primary schools in the UK today.

What is a phoneme?

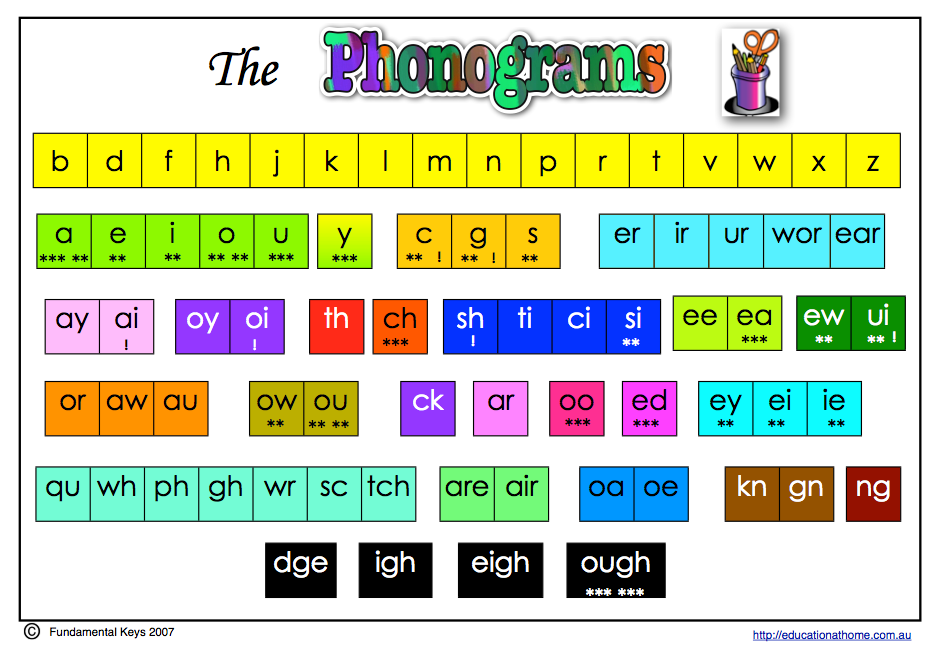

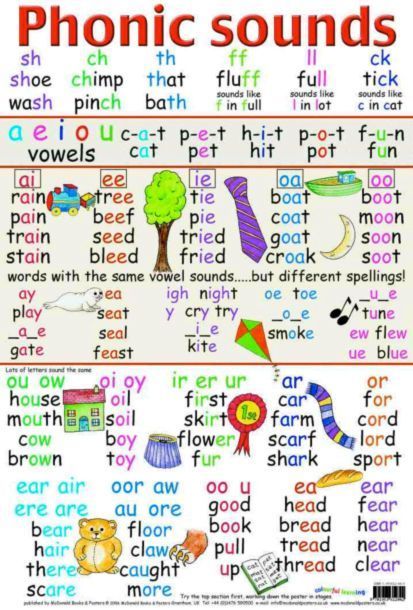

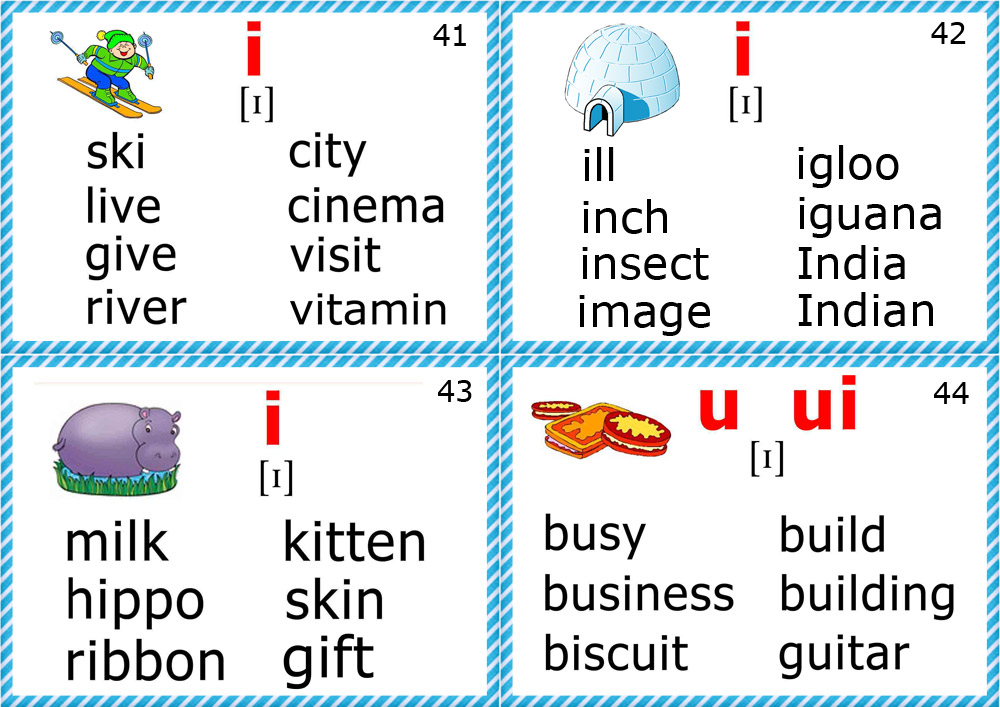

A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound. The phonemes used when speaking English are:

Print out a list of phonemes to practise with your child or listen to the individual sounds being spoken with our phonics worksheets.

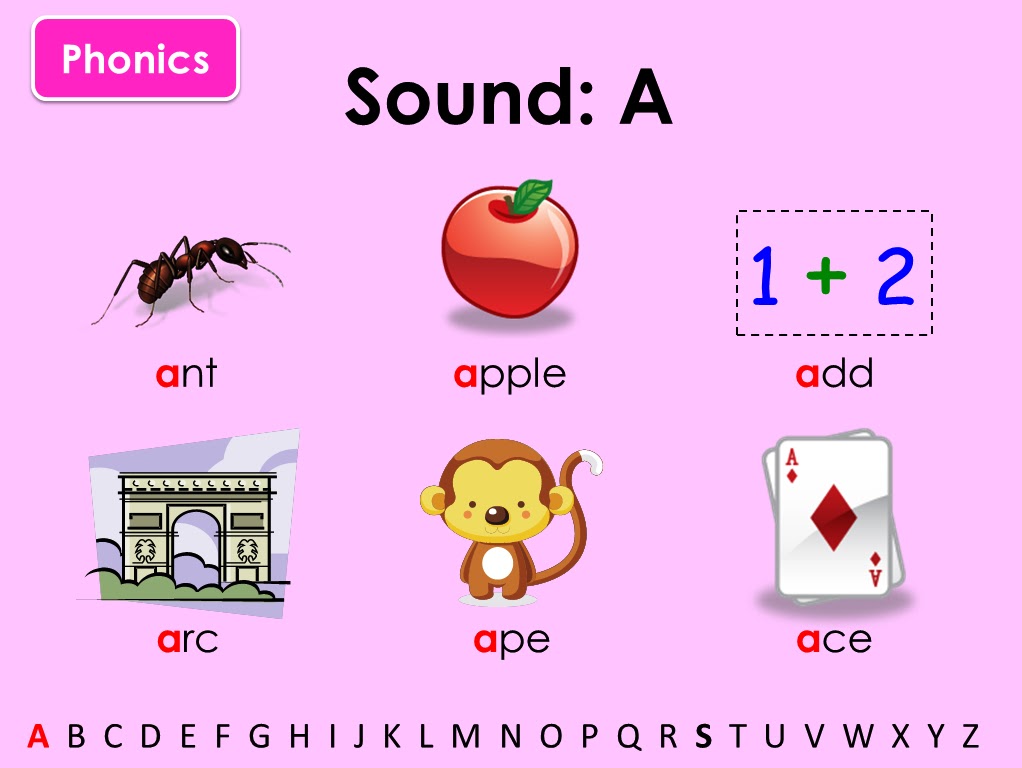

Phonics learning step 1: decoding

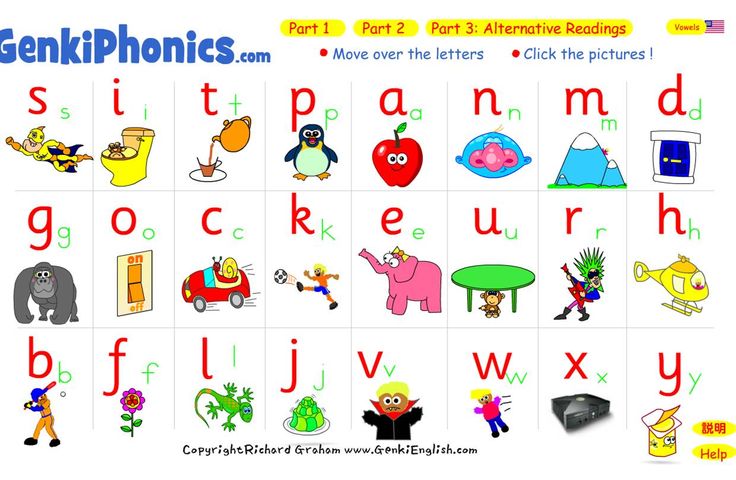

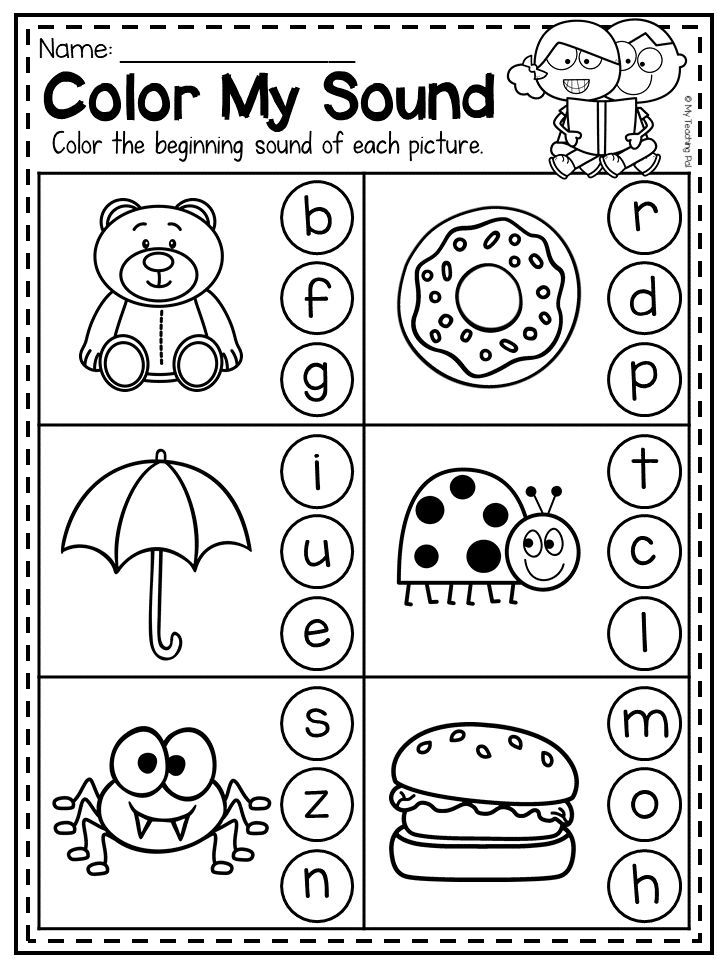

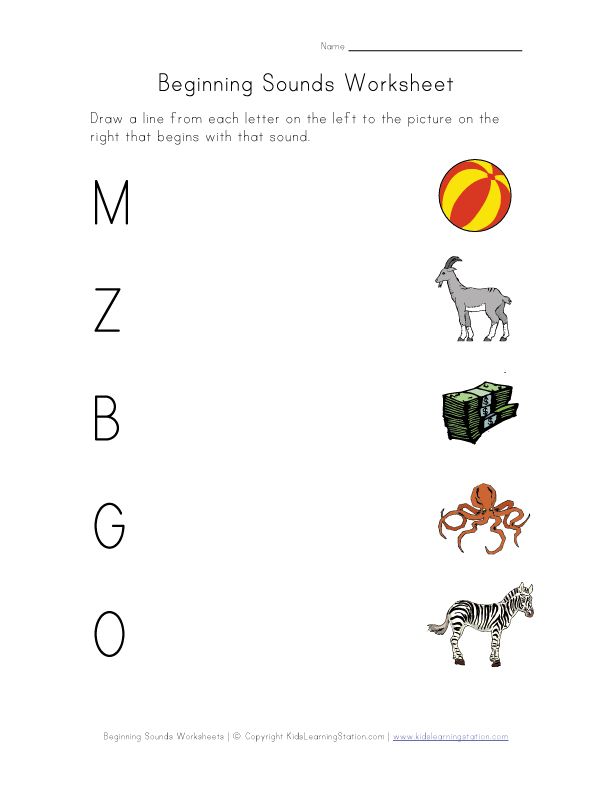

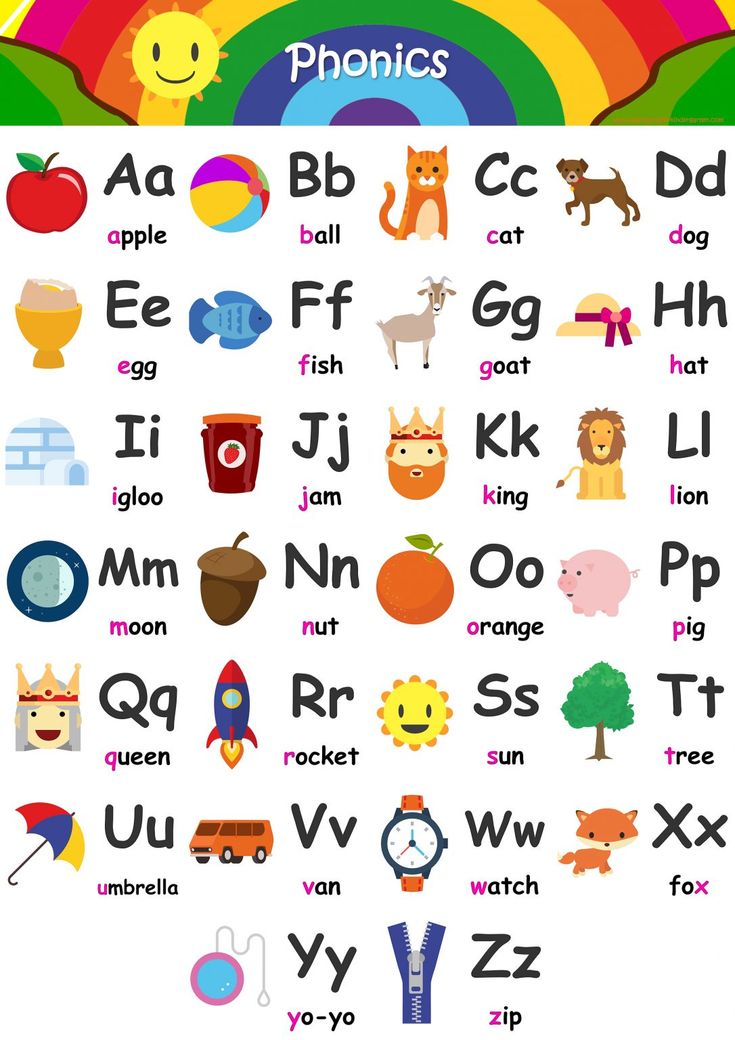

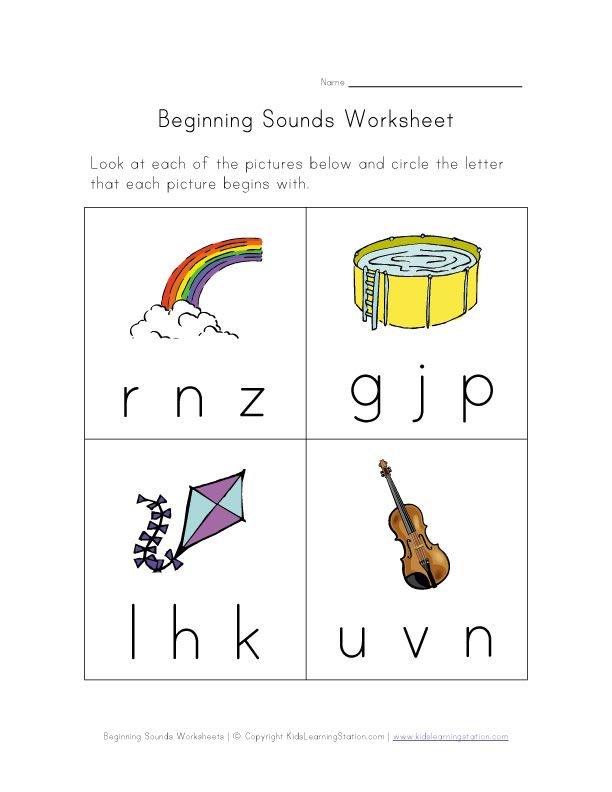

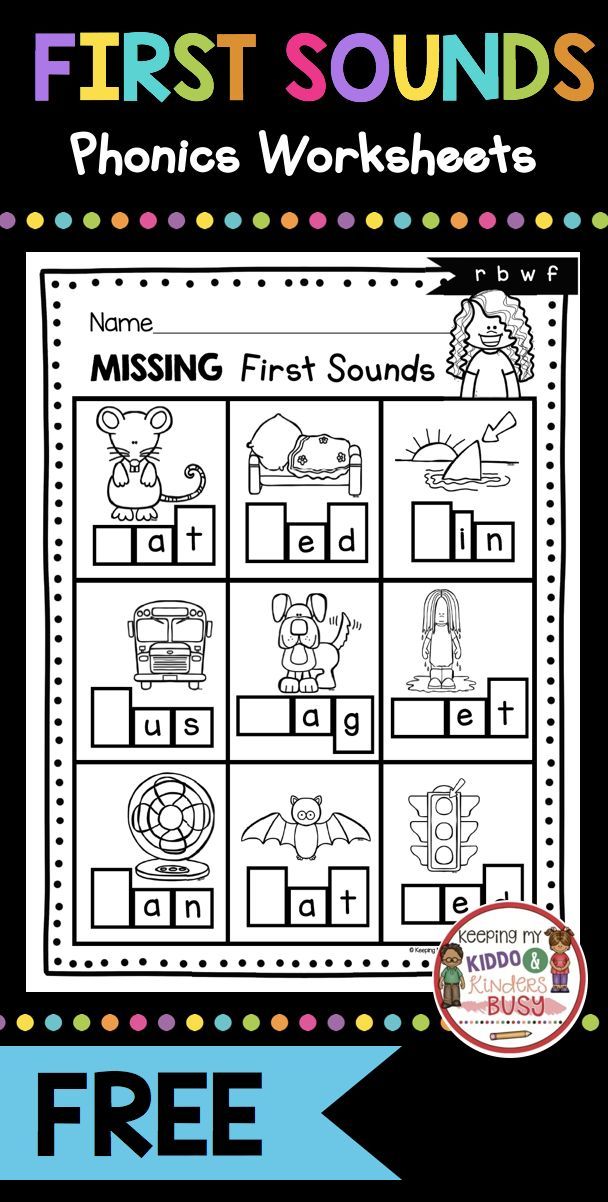

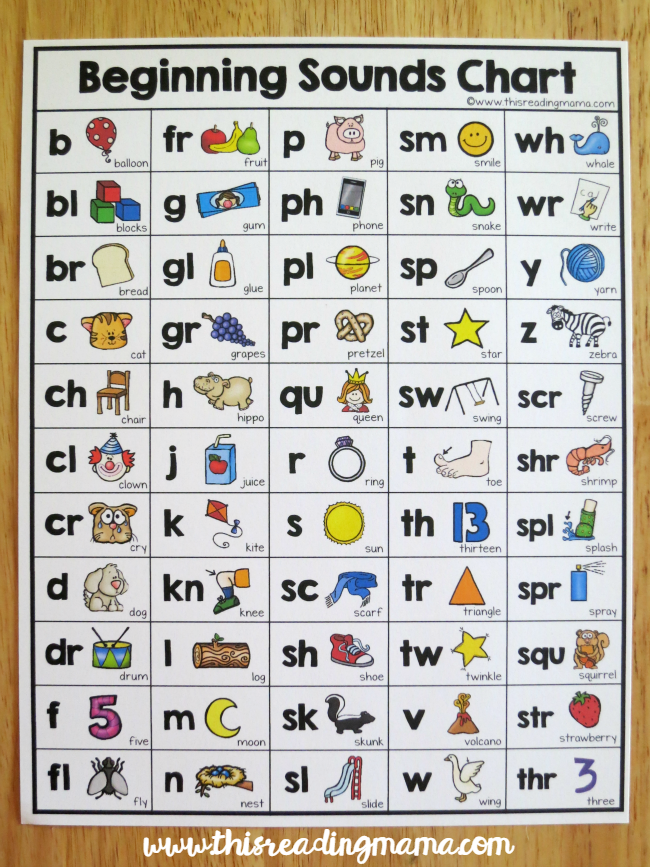

Children are taught letter sounds in Reception. This involves thinking about what sound a word starts with, saying the sound out loud and then recognising how that sound is represented by a letter.

The aim is for children to be able to see a letter and then say the sound it represents out loud. This is called decoding.

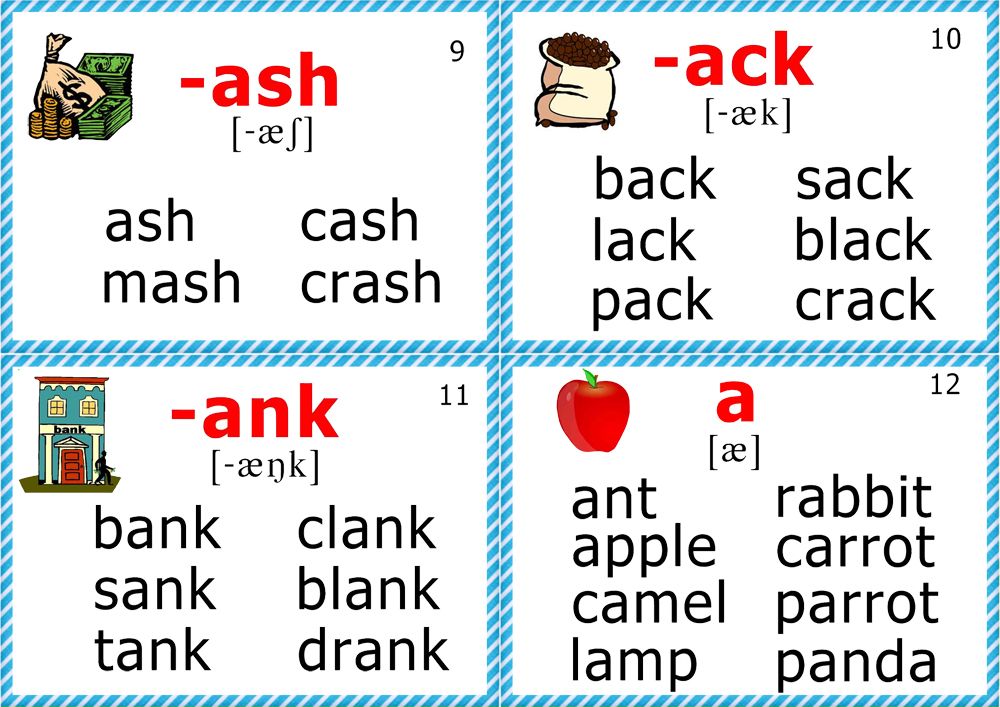

Some phonics programmes start children off by learning the letters s, a, t, n, i, p first. This is because once they know each of those letter sounds, they can then be arranged into a variety of different words (for example: sat, tip, pin, nip, tan, tin, sip, etc.). While children are learning to say the sounds of letters out loud, they will also begin to learn to write these letters (encoding).

They will be taught where they need to start with each letter and how the letters need to be formed in relation to each other. Letters (or groups of letters) that represent phonemes are called graphemes.

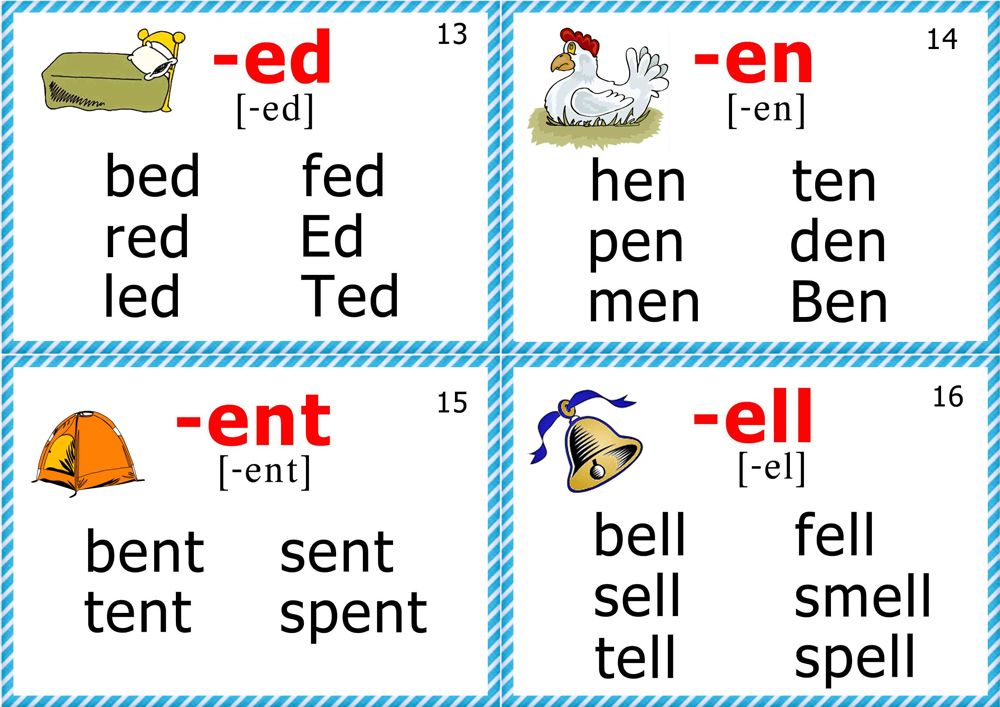

Phonics learning step 2: blending

Children then need to go from saying the individual sounds of each letter, to being able to blend the sounds and say the whole word. This can be a big step for many children and takes time.

Phonics learning step 3: decoding CVC words

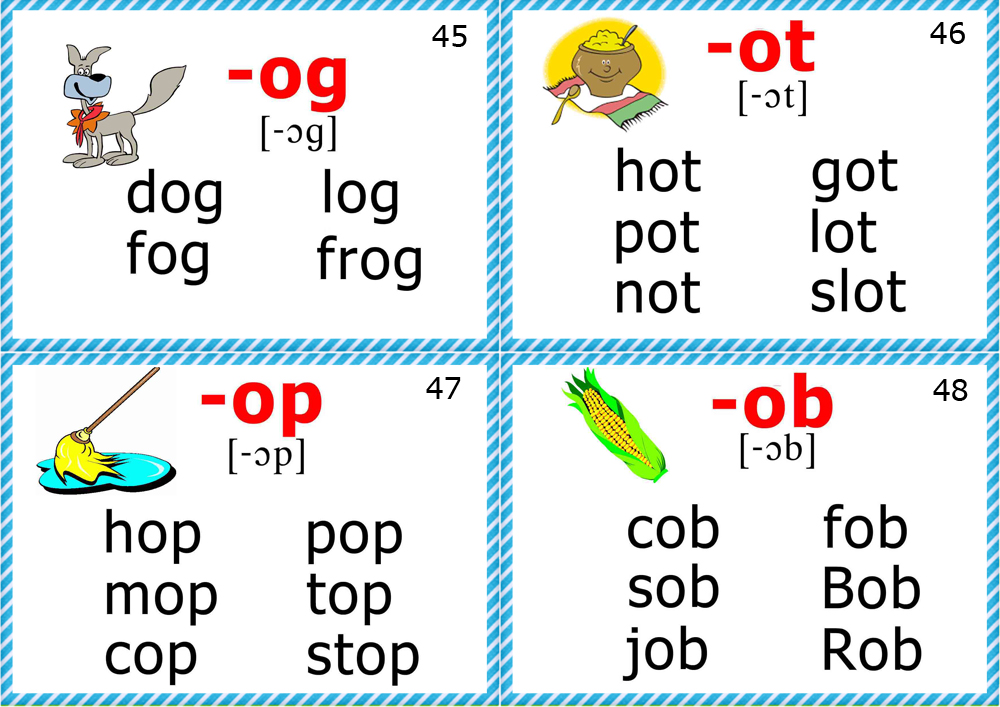

Children will focus on decoding (reading) three-letter words arranged consonant, vowel, consonant (CVC words) for some time.

They will learn other letter sounds, such as the consonants g, b, d, h and the remaining vowels e, o, u. Often, they will be given letter cards to put together to make CVC words which they will be asked to say out loud.

Phonics learning step 4: decoding consonant clusters in CCVC and CVCC words

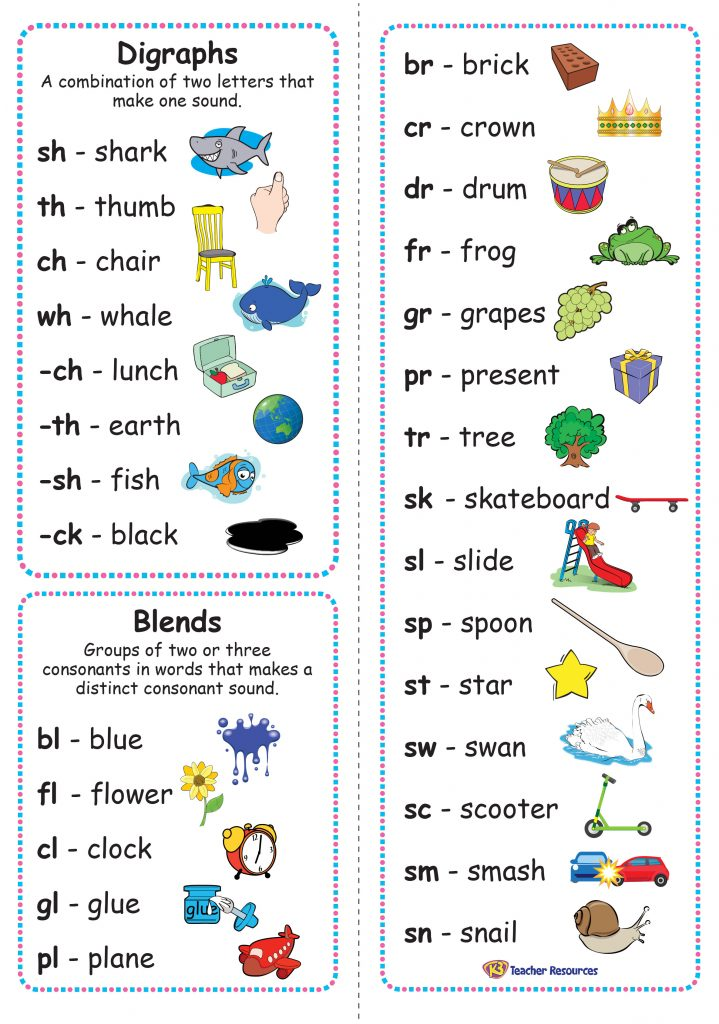

Children will also learn about consonant clusters: two consonants located together in a word, such tr, cr, st, lk, pl. Children will learn to read a range of CCVC words (consonant, consonant, vowel, consonant) such as trap, stop, plan.

They will also read a range of CVCC words (consonant, vowel, consonant, consonant) such as milk, fast, cart.

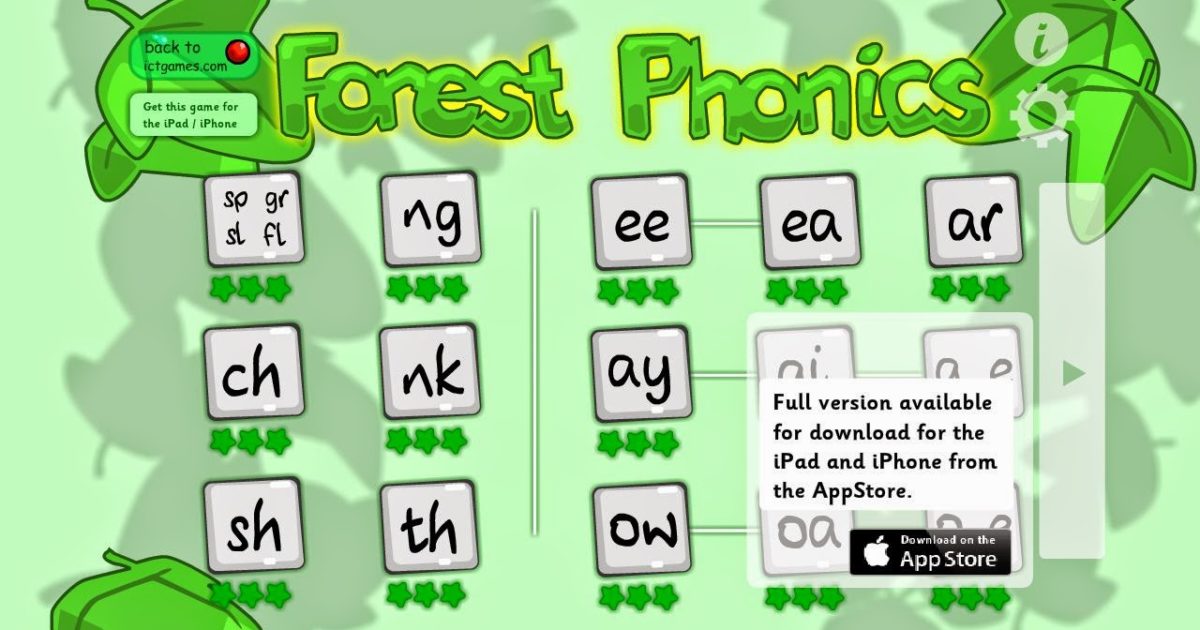

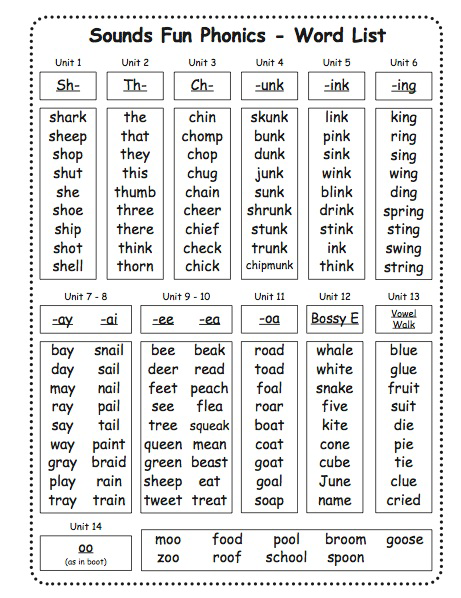

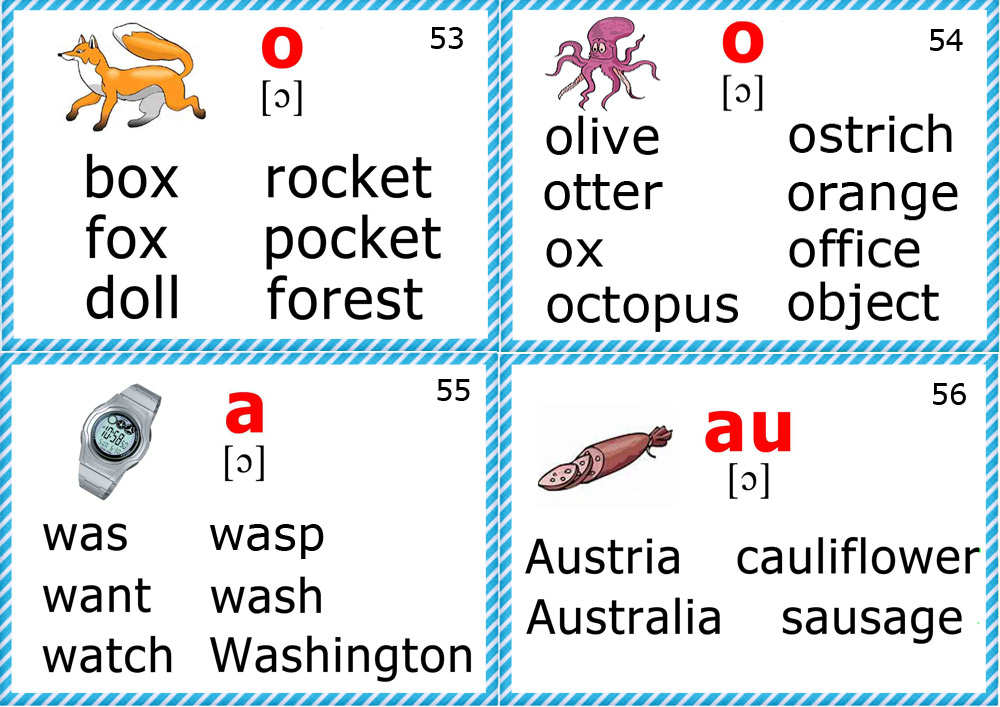

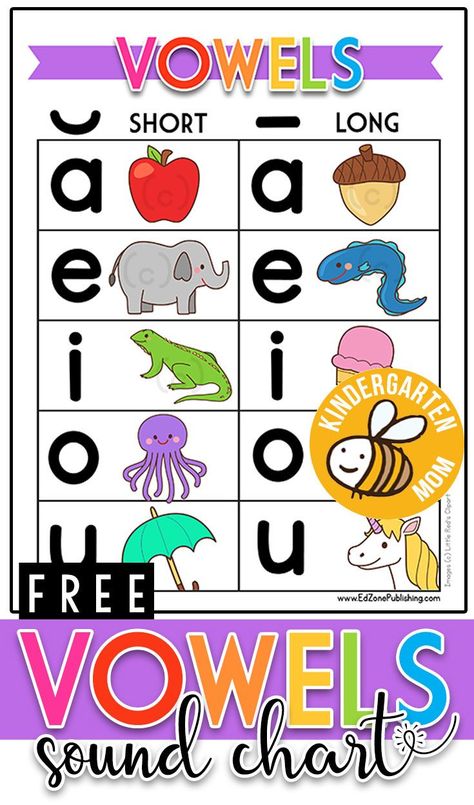

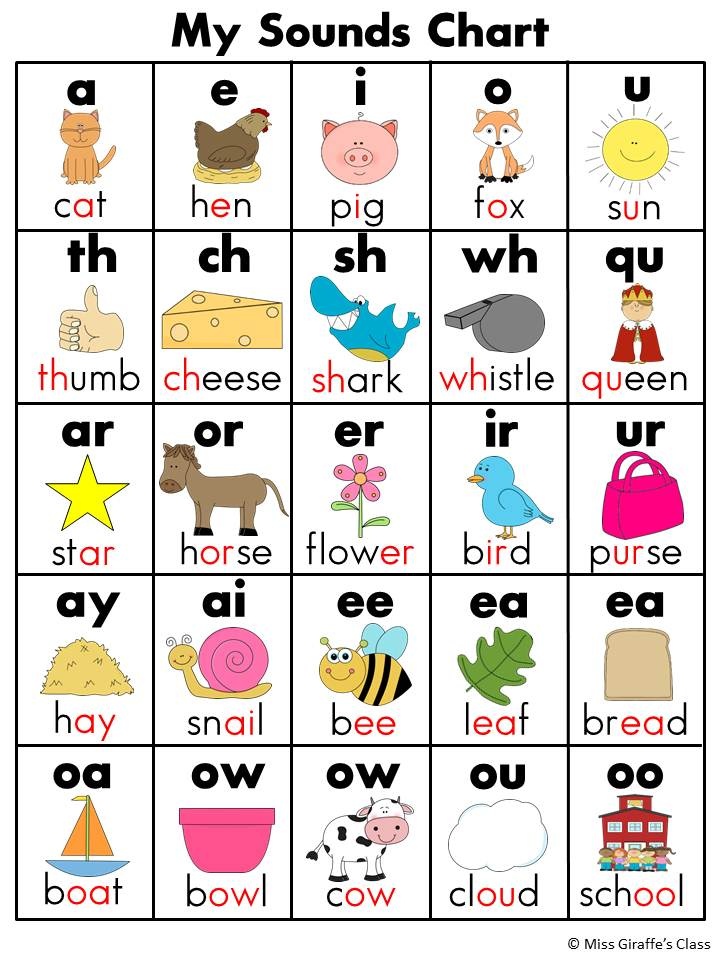

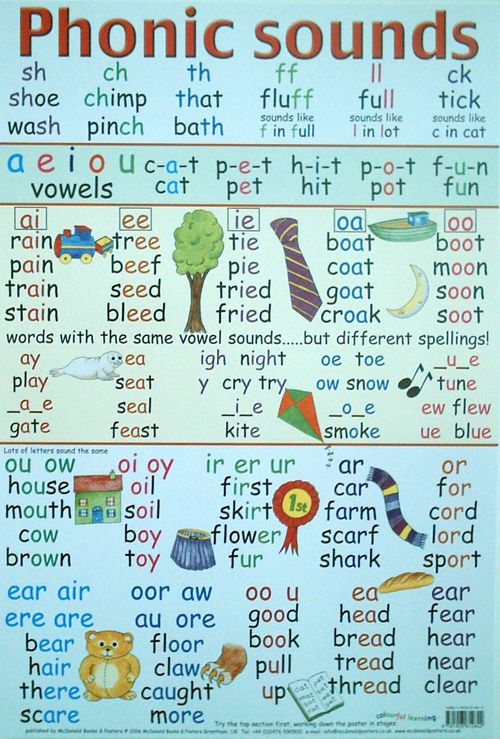

Phonics learning step 5: vowel digraphs

Children are then introduced to vowel digraphs. A digraph is two vowels that together make one sound such as: /oa/, /oo/, /ee/, /ai/. They will move onto sounding out words such as deer, hair, boat, etc. and will be taught about split digraphs (or 'magic e').

They will also start to read words combining vowel digraphs with consonant clusters, such as: train, groan and stool.

Phonics learning step 6: consonant digraphs

Children will also learn the consonant digraphs (two consonants that together make one sound) ch and sh and start blending these with other sounds to make words, such as: chat, shop, chain and shout.

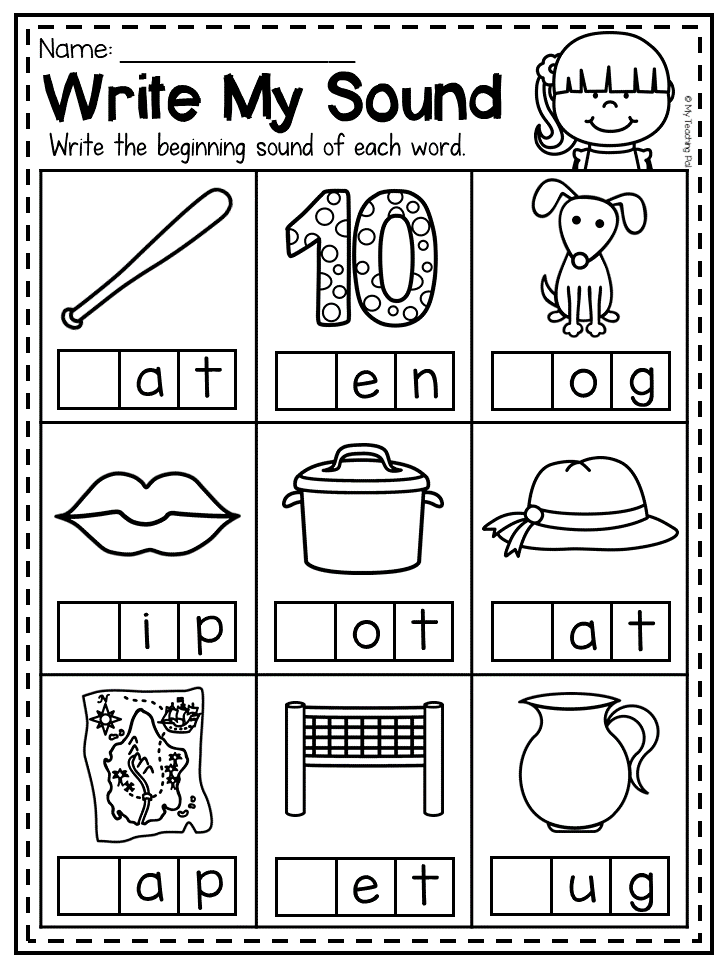

Encoding, or learning to spell as well as read

Alongside this process of learning to decode (read) words, children will need to continue to practise forming letters which then needs to move onto encoding. Encoding is the process of writing down a spoken word, otherwise known as spelling.

Encoding is the process of writing down a spoken word, otherwise known as spelling.

They should start to be able to produce their own short pieces of writing, spelling the simple words correctly.

It goes without saying that reading a range of age-appropriate texts as often as possible will really support children in their grasp of all the reading and spelling of all the phonemes.

Phonics learning in KS1

By the end of Reception, children should be able to write one grapheme for each of the 44 phonemes.

In Year 1, they will start to explore vowel digraphs and trigraphs (a group of three letters that makes a single sound, like 'igh' as in 'sigh') further.

They will begin to understand, for example, that the letters ea can make different sounds in different words (dream and bread). They will also learn that one sound might be represented by different groups of letters: for example, light and pie (igh and ie make the same sound).

Children in Year 2 will be learning spelling rules, such as adding suffixes to words (such as -ed, -ing, -er, -est, -ful, -ly, -y, -s, -es, -ment and -ness). They will be taught rules on how to change root words when adding these suffixes (for example, removing the 'e' from 'have' before adding 'ing') and then move onto harder concepts, such as silent letters (knock, write, etc) and particular endings (le in bottle and il in fossil).

They will be taught rules on how to change root words when adding these suffixes (for example, removing the 'e' from 'have' before adding 'ing') and then move onto harder concepts, such as silent letters (knock, write, etc) and particular endings (le in bottle and il in fossil).

Free phonics worksheets and information for parents

For more information about the phonics system look through our phonics articles, including ways to boost phonics confidence, details of the Year 1 Phonics Screening Check, parents' phonics questions answered and more.

We also have a large selection of free phonics worksheets to download for your child.

More like this

Phonics phases explained

10 ways to boost phonics confidence

Spelling in Year 1

Common phonics problems sorted

What is a grapheme?

Phonics games

Blending sounds: teachers' tips

Best phonics learning tools

Teachers' tricks for phonics

Phonics: In Practice | Reading Rockets

Phonics instruction teaches common letter-sound relationships, including sounds for common letter patterns, so that readers can apply them in decoding unfamiliar words.

The purpose of phonics instruction

In this section:

Only a small percentage of English words have irregular spellings and letter-sound relationships. This means that nearly all English words can be read by applying knowledge of letter-sound relationships and blending sounds together to form a whole word. To learn more, see How Words Cast Their Spell.

Being able to decode words effortlessly (convert spelling into speech sounds) means children are able to focus their attention on comprehending what they read.

Beginning phonics lessons

Regardless of grade, start phonics lessons with consonant letter sounds that are easy to pronounce and less often confused with similar letter sounds. This enables students to master one letter sound before having to learn a similar letter sound. For example, students may confuse the letter sounds for t and d. Since the letter t is more common, instruction should introduce t many lessons before introducing d.

Learning sounds for letters is basically rote learning, and for rote learning, the use of memory cues can be very helpful. For instance, for short a, children can learn that the letter a looks like an apple with a broken stem, and short a represents /a/ as in apple. Multi-sensory activities, such as repeatedly tracing the vowel letter and saying its sound, are often useful as well.

Start explicit phonics instruction with short vowel words because these vowels have one predictable spelling (with few exceptions) and are the most commonly occurring vowel sounds in English. Because the short vowel sounds are highly confusable, they should be taught individually, not all at the same time.

Phonics Terms

- Phoneme

The smallest unit of sound in our spoken language. Pronouncing the word cat involves blending three phonemes: /k/ /ae/ /t/. - Grapheme

A written letter or a group of letters representing one speech sound. Examples: b, sh, ch, igh, eigh.

Examples: b, sh, ch, igh, eigh. - Onset

An initial consonant or consonant cluster. In the word name, n is the onset; in the word blue, bl is the onset. - Rime

The vowel or vowel and consonant(s) that follow the onset. In the word name, ame is the rime. - Digraph

Two letters that represent one speech sound (diphthong). Examples: sh, ch, th, ph. - Vowel digraph

Two letters that together make one vowel sound. Examples: ai, oo, ow. - Schwa

The vowel sound sometimes heard in an unstressed syllable and that most often sounds like /uh/ or the short /u/ sound. Example: the "a" in again or balloon. All English vowels have a schwa sound. - Morpheme

The smallest meaningful units of language. The word cat is a morpheme. Not all morphemes stand alone as words; some are attached to words, usually as affixes. These are called bound morphemes. Examples include: non-, -est, -ing, -er, -ion.

The word cat is a morpheme. Not all morphemes stand alone as words; some are attached to words, usually as affixes. These are called bound morphemes. Examples include: non-, -est, -ing, -er, -ion.

Kindergarten phonics lessons

Phonics lessons in kindergarten focus on students becoming automatic at letter naming, single-grapheme letter sounds, and reading single-syllable words with short vowel spellings. Instruction may include common digraphs (ch, sh, th, wh, and ck). For some kindergarten students, articulating some consonant sounds may be difficult, but this does not prevent them from reading and comprehending words with those sounds.

To learn more about when kids learn different consonant sounds, see this Speech-Sound Development chart.

Back to top

First grade phonics lessons

In first grade, phonics lessons start with the most common single-letter graphemes and digraphs (ch, sh, th, wh, and ck). Continue to practice words with short vowels and teach trigraphs (tch, dge). When students are proficient with earlier skills, teach consonant blends (such as tr, cl, and sp).

Continue to practice words with short vowels and teach trigraphs (tch, dge). When students are proficient with earlier skills, teach consonant blends (such as tr, cl, and sp).

Ensure students understand the difference between blends, digraphs, and trigraphs: that each letter in a blend retains its own sound, while the letters in digraphs and trigraphs represent one sound.

In first grade, we may also include two-syllable words with short vowel sounds (e.g., cat∙fish, pic∙nic, kit∙chen). Inflectional endings such as ing, er, and s would also be included. When students have mastered short vowel spelling patterns, introduce r-controlled (e.g., er, ur, or, ar), long vowel (e.g., oa, ee, ai), and other vowel sound spellings (e.g., oi, aw, oo, ou, ow).

Teaching of common syllable types is also very useful for first-graders. By the end of first grade, typical readers should be able to decode a wide range of phonetically regular one-syllable words with all of these letter patterns and syllable types, including one-syllable words with common inflectional endings (e.g., sliding, barked, sooner, floated).

By the end of first grade, typical readers should be able to decode a wide range of phonetically regular one-syllable words with all of these letter patterns and syllable types, including one-syllable words with common inflectional endings (e.g., sliding, barked, sooner, floated).

Teaching syllable types in first grade

Teaching children about syllable types is useful because vowel sounds in English vary, and knowledge about syllable types can help children determine the vowel sound of a one-syllable word. Later, once they have learned some rules for dividing long words, children can also apply their knowledge of syllable types to decode two-syllable and multisyllabic words.

Instruction in syllable types should focus on children’s abilities to classify words correctly (e.g., sort one-syllable words that are closed from one-syllable words that are not closed) rather than on children’s abilities to recite rules or definitions. However, it is very important for us to present clear, consistent definitions of the syllable types, in order to avoid inadvertently confusing instruction.

The six syllable types common in English are closed, silent e, open, vowel combination, vowel r, and consonant-le. The chart below lists these syllable types along with their typical vowel sounds, definitions, some examples, and some additional comments.

The specific order in which syllable types are taught can vary substantially, depending on the phonics program being used. However, the closed syllable type is usually taught first, because closed syllables are common in English, and it is virtually impossible to write even a very simple story for children that contains no closed syllables. Conversely, consonant-le syllables always occur as part of two-syllable (or longer) words, so that syllable type would often be taught last.

| Syllable Type (Synonyms) | Vowel Sound | Definition | Examples | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed | Short | Has only one vowel and ends in a consonant. | splash, lend, in, top, ask, thump, frog, mess | The main prerequisite when children learn the closed syllable type is that they first have to be able to classify letters as either vowels or consonants. |

| Silent e (magic e) | Long | Has a –VCE pattern (one vowel, followed by one consonant, followed by a silent e that ends the syllable) | plane, tide, use, chime, theme, ape, stroke, hope | Words like noise, prince, and dance are not silent e, even though they end in a silent e, because they do not have the -VCE pattern; noise has a –VVCE pattern and prince and dance have a -VCCE pattern. |

| Open | Long | Has only one vowel that is the last letter of the syllable. | he, she, we, no, go, flu, by, spy | This syllable type becomes especially useful as children progress to two-syllable words. For example, the ti in title, lo in lotion, and ra in raven are all open syllables. For example, the ti in title, lo in lotion, and ra in raven are all open syllables. |

| Vowel combination (vowel team) | Varies depending on the specific vowel pattern; children must memorize sounds for these individual vowel patterns. | Has a vowel pattern in it (e.g., ay, ai, aw, all, ie, igh, ow, ee, ea). | stay, plain, straw, fall, pie, piece, night, grow, cow | Vowel patterns do not always involve two vowels but can also consist of a vowel plus consonants, if this pattern has a consistent sound (e.g, igh almost always represents long /i/; all almost always represents /all/). Also, some vowel patterns can have more than one sound. For example, ow can represent long /o/ as in grow or /ow/ as in cow. For these patterns, children learn both sounds and, when decoding an unfamiliar word, they try both sounds to see which one makes a real word. |

| Vowel r (bossy r, r- controlled) | Varies depending on the specific vowel r unit; children must memorize sounds for these units (e.g., ar, er, ir, or, ur). | Has only one vowel followed immediately by an r | ark, charm, her, herd, stir, born, fork, urn | Does not include words in which the vowel r unit is followed by an e (e.g., stare, cure, here) or in which the r follows a vowel combination (e.g., cheer, fair, board). These words can usually be taught as silent e (in the first case) or vowel combination (in the second). |

| Consonant-le | Schwa | Has a –CLE pattern (one consonant, followed by an l, followed by a silent e which ends the syllable) | -dle as in candle, -fle as in ruffle, -ple as in maple, -gle as in google, -tle as in title, -ble as in Bible | Consonant-le syllables never stand alone; they always are part of a longer word. Also, they are never the accented syllable of a longer word. Also, they are never the accented syllable of a longer word. |

Video: Learning ‘b’ and ‘d’ and Reading Short Vowel Words

In this video, reading expert Linda Farrell works with Aiko on a common letter reversal — confusing the letters ‘b’ and ‘d’. Ms. Farrell coaches Aiko to look at the letters during b/d practice and to look at the words while she works with Aiko to read short vowel words accurately. See more videos here: Looking at Reading Interventions.

Back to top

Second grade, third grade, and beyond

As students enter Grade 2, they should be learning to decode a wide range of two-syllable and then multisyllable (i.e., three syllables or more) words. Instruction in decoding these longer words should include attention to common syllable division patterns and syllabication rules.

Common syllable division patterns

To decode words of more than one syllable, children need a strategy for dividing longer words into manageable parts. They can then decode the individual syllables by applying their knowledge of syllable types and common letter-sound patterns, blending those syllables back into the whole word.

The chart below provides some useful generalizations for teaching students how to divide (syllabicate) two-syllable words with various common patterns, in order to decode them. These generalizations also are useful for decoding multisyllabic words, those with three or more syllables.

| Pattern | Generalization | Examples | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

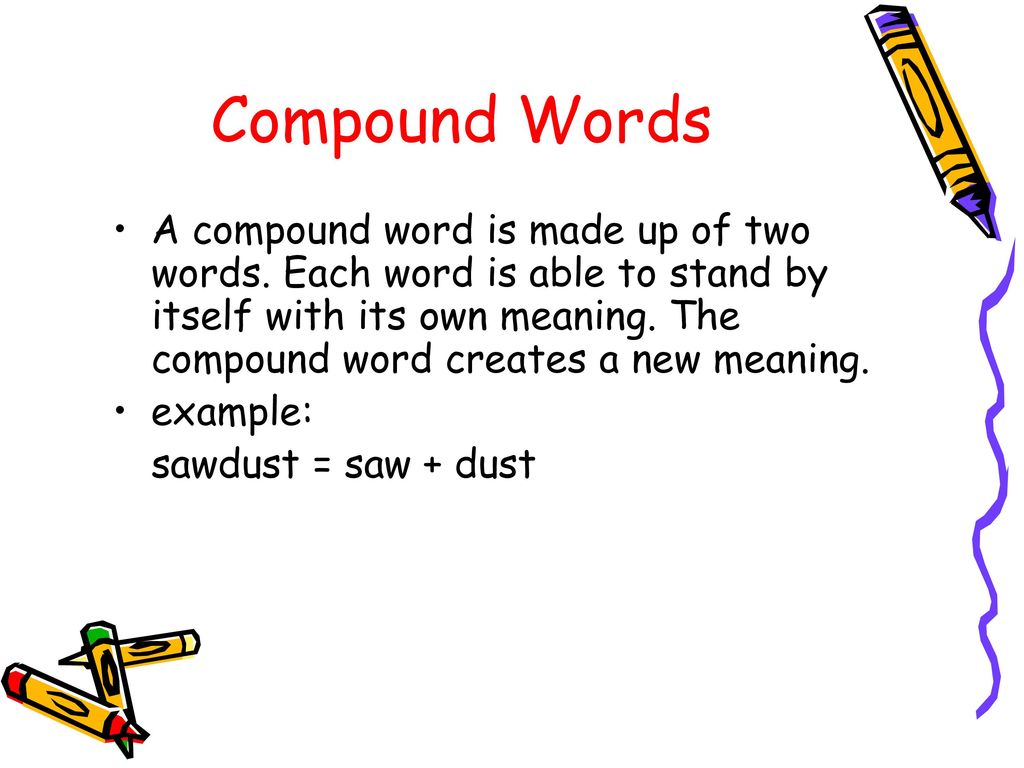

| Compound | In a compound word, divide between the two smaller words. | back/pack, lamp/shade, bed/room, bath/tub, work/book | To be a true compound word, each of the smaller words must carry meaning in the context of the word (e. g., carpet is not a compound word, because a carpet is not a pet for your car or a car for your pet). g., carpet is not a compound word, because a carpet is not a pet for your car or a car for your pet). |

| VCCV | If a word has a VCCV (vowel-consonant-consonant-vowel) pattern, divide between the two consonants. | or/bit, ig/loo, tun/nel, lan/tern, tar/get, vel/vet | There is an exception if the two consonants form a consonant digraph (a single sound), as in bishop, rather, gopher, or method. In these cases, treat the word as a VCV word, not VCCV (see below). |

| -CLE | If a word ends in a consonant-le syllable, always divide immediately before the -CLE. | ma/ple, stum/ble, i/dle, nee/dle, gig/gle, mar/ble, tur/tle | |

| -VCV | If a word has a VCV (vowel-consonant-vowel) pattern, first try dividing before the consonant and sounding out the resulting syllables; if that does not produce a recognizable word, try dividing after the consonant. | hu/mid, ra/ven, mu/sic, go/pher; plan/et, com/et, tim/id, bish/op, meth/od, rath/er | To recognize the correct alternative, the child needs to have the word in his/her oral vocabulary. If the student does not recognize the correct alternative, we can have them try both options (e.g., hu/mid with a long u vs. hum/id with a short u). Then, if necessary, just tell the child the correct pronunciation of the word, with a brief explanation of its meaning. |

| Prefix | In word with a prefix, divide immediately after the prefix. | pre/view, mis/trust, un/wise, re/mind, ex/port, un/veil | See below. |

| Suffix | In a word with a suffix, divide immediately before the suffix. | glad/ly, wise/ly, sad/ness, care/less, hope/ful, frag/ment, state/ment, na/ture, frac/tion | Depending on its origin, the base word in a word containing prefixes or suffixes will not always be a recognizable word. However, the key point is that, when dividing a longer word, prefixes and suffixes are units that always stay together as patterns; never divide in the middle of a prefix or in the middle of a suffix. However, the key point is that, when dividing a longer word, prefixes and suffixes are units that always stay together as patterns; never divide in the middle of a prefix or in the middle of a suffix. |

Continue explicit phonics instruction through second grade with increasingly complex spelling patterns. By third grade, shift explicit phonics instruction mostly to explicit morphology instruction. Students move from learning about letter/sound relationships to sounds for prefixes, suffixes, roots, base words, and combining forms.

Vocabulary and spelling can be integrated with instruction in reading words. For example, as children learn to read the root geo, they learn that it means earth and that it will have a stable spelling across related words such as geology, geologist, geological, geography, geographic, etc.

Although many word-reading skills are developed by the end of Grade 3, children may be learning some of these skills even beyond Grade 3. Developing an understanding of etymology (word origins) is one example of this more advanced kind of skill for reading words.

Developing an understanding of etymology (word origins) is one example of this more advanced kind of skill for reading words.

For instance, j is pronounced /h/ in words of Spanish origin, and this pronunciation is retained in English words borrowed from Spanish, such as jalapeno and junta.

As another example, words that end in –ique such as boutique, antique, and mystique are borrowed from French and retain the French pronunciation for this pattern, /eek/.

Children do not need to learn sounds for all letter patterns in every language, but if they understand that many words in English are borrowed from other languages, and that these words often retain at least part of their pronunciation in the original language, this can benefit their word reading as well as their spelling.

Back to top

Phonics lesson planning

Lesson plans for explicit phonics instruction start with a clear, achievable objective. An objective may be learning two to three new consonant sounds, one new vowel sound, or a new phonics concept (e.g., in one-syllable words, ck spells the sound /k/ after one vowel letter and only at the end of a word). Lesson plans will likely span many days and include multiple layers of instruction and practice.

An objective may be learning two to three new consonant sounds, one new vowel sound, or a new phonics concept (e.g., in one-syllable words, ck spells the sound /k/ after one vowel letter and only at the end of a word). Lesson plans will likely span many days and include multiple layers of instruction and practice.

Lesson plans can start with a review and include previously taught concepts throughout the lesson. Lessons pull forward everything taught previously.

New concepts (e.g., letter sounds) are explicitly taught before being practiced. All practice should include an “I do, We do, You do” practice. In “I do,” model the activity. In “We do,” guide the group through practice. In “You do,” have students practice individually and model proficiency.

Build scaffolded instruction and practice into activities. Each subsequent practice activity contains less scaffolding until students are independently proficient. Practice activities move from isolated skills to skills that are more complex. For example:

For example:

- Students read and spell letter name and letter sounds in isolation.

- Students read words sound by sound.

- Students read word chunks and word patterns.

- Students read whole words, sounding out only to resolve reading errors.

- Students spell words sound by sound, and practice spelling chains where only one letter changes from one word to the next (e.g., sap to lap to lip to lit to slit)

- Students may learn word meanings to understand sentences and passages, but vocabulary instruction is typically outside the phonics instruction block.

- Students read decodable phrases, sentences, and passages once for accuracy and again for fluency.

- Students spell short decodable sentences.

Have students read individually for accuracy and again for fluency while reading lists as well as sentences and passages. This need not be included in every activity.

Assess each student’s skills individually before introducing new concepts. When individual students have not mastered the objective, use your best judgment. Should the group move forward? Should the individual student receive extra practice? The answer will vary based on the composition of the group and the proportion of students in it who are struggling.

When individual students have not mastered the objective, use your best judgment. Should the group move forward? Should the individual student receive extra practice? The answer will vary based on the composition of the group and the proportion of students in it who are struggling.

Back to top

Sample beginning phonics lessons

Phonics lessons flow naturally out of phonemic awareness activities. For example,

- In phonemic awareness, ask students to segment words with the sounds short a, /m/, /p/, and /t/.

- Explain that the letter m spells the sound /m/, etc.

- Have students individually practice saying letter names in isolation.

- Have students individually practice reading letter sounds in isolation.

- Introduce three to four irregularly spelled high-frequency words to learn by sight.

- Ask students to segment words with the sounds short a, /m/, /p/, and /t/, and then arrange letter tiles to spell the segmented words.

- Demonstrate how to point to each letter and say the sound. Then blend the letters to read words (called "touch and say" or "touch and read").

- Have students individually practice sounding out three to five words, then re-read the words they sounded out previously.

- Ask individual students to read a list of words (comprised of only the sounds explicitly taught and practiced to date).

- Students read once for accuracy and again for fluency.

- When a student misreads a word, guide the student through sounding out the word. Then the student re-reads the whole group of words to the end by reading accurately.

- Lead students in a review of the irregularly spelled high-frequency words taught earlier in the lesson and from prior lessons. Learn more in this article, A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words.

- Guide students through reading phrases, sentences, and (eventually) passages comprised of decodable words with the sounds explicitly taught and practiced to date along with some irregularly spelled high-frequency words.

- Students read once for accuracy and again for fluency.

- When a student misreads a word, guide the student through sounding out the word. Then the student re-reads the whole phrase, sentence, or portion of the passage to the end by reading accurately.

- Students spell letter sounds, decodable words, and short decodable sentences.

Beginning phonics lessons introduce only three or four new consonant sounds and only one new vowel sound in a lesson. Continue with this lesson until all students in the group are reading at 95–98% accuracy on a first attempt. Move to the next lesson, introducing another three or four consonant sounds and another new vowel sound.

Children in a general education classroom will vary widely in how easily they acquire word recognition skills. We should make use of flexible groups to meet the needs of children who can move ahead quickly in their word-reading skills, or conversely, the needs of those who require more practice.

Children who consistently perform at a high rate of mastery in their word recognition skills can focus on other valuable literacy activities such as independent reading and writing, while we are working with flexible groups who require continued phonics instruction.

Back to top

Phonics lesson routines

Include instructional routines in lesson activities. Instructional routines are repeatable routines used to practice a new skill.

For example, guide the reading group to use "touch and say" to read a list of words containing the lesson’s focus letter sounds. The steps for the activity are:

- Model "touch and say" with one word.

- Have the group use "touch and say" to read three words together.

- Have each student use "touch and say" to read five words and then re-read the list without "touch and say."

- Ask the whole group to read the same five words chorally. Use this routine daily during the phonics lesson as the activity that precedes reading whole words.

Instructional routines reduce students’ memory load. Students do not have to remember the steps in a routine while simultaneously remembering the new concept. As a result, routines provide support and stability and improve the pace of the lesson.

Moats, L. and Hall, S. (2010). LETRS Module 7: Teaching Phonics, Word Study, and the Alphabetic Principle (Second Edition). Longmont, CO: Sopris West.

Back to top

Instruction for all: the value of a multisensory approach

Teaching experience supports a multisensory instruction approach in the early grades to improve phonemic awareness, phonics, and reading comprehension skills. Multisensory instruction combines listening, speaking, reading, and a tactile or kinesthetic activity.

NOTE: Research does not yet have definitive answers about how multisensory instruction works. Literacy expert Tim Shanahan offers this perspective in his blog post, What About Tracing and Other Multisensory Teaching Approaches?.

Phonics instruction lends itself to multisensory teaching techniques, because these techniques can be used to focus children’s attention on the sequence of letters in printed words. As such, including manipulatives, gestures, and speaking and auditory cues increases students’ acquisition of word recognition skills. An added benefit is that multisensory techniques are quite motivating and engaging to many children.

Multisensory activities provide needed scaffolding to beginning and struggling readers and include visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile activities to enhance learning and memory. As students practice a learned concept, reduce the multisensory scaffolds until the student is using only the visual for reading. Employ the multisensory techniques to fix errors and then practice without the scaffold.

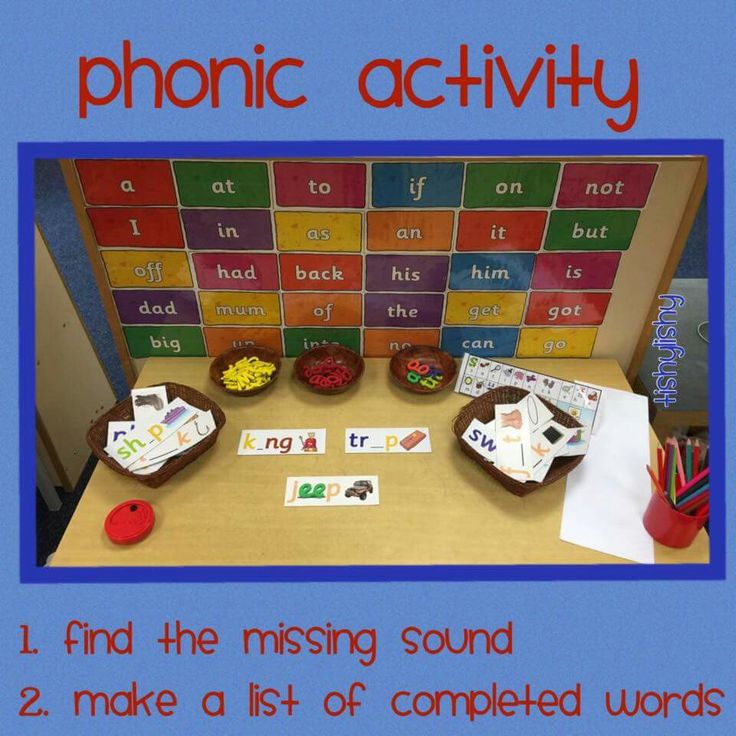

Examples of multisensory phonics activities:

- Dictate a word using say, touch, and spell. Students say each sound in the word and place a manipulative (e.

g., a tile with a letter or letter pattern on it, such as sh, ch, ck) to represent each sound in the word.

g., a tile with a letter or letter pattern on it, such as sh, ch, ck) to represent each sound in the word.For example, when we say fin, students move the letter tiles for f, i, and n, to spell the word, while at the same time saying and stretching the sounds orally. If we then say fish, students replace the tile with n on it with one that has an sh.

Subsequent examples of words in the chain could be wish, wig, wag, bag, brag, and so on. The activity should use only letter sounds/pattern sounds that children have been taught.

Letter tiles also should represent sounds at the phoneme level. For example, fish would be spelled with three tiles (f, i, sh), because it has three phonemes, whereas brag would be spelled with four tiles (b, r, a, g), reflecting four phonemes.

Place ending spelling patterns and beginning consonants (or consonant blends) on cards. Have students work in pairs and arrange as many words as they can on a table. Do a table walk and have each pair read the words they created. Give other teams an opportunity to create a new word.

- Organize spelling around the vowel letter. Assign a gesture to each vowel sound. Dictate a word and have students make the gesture for the vowel sound in the word.

- Assign a gesture to /sh/ and /ch/. Dictate words. Ask students to individually make the gesture associated with /sh/ or /ch/ when they hear those sounds in a word.

- Paddle pop: Teach letter clusters such as ing and ink. Write these clusters on card stock and staple to popsicle sticks. Dictate words and ask students to pop up the paddle containing the letter cluster in the word.

- Sounding out words:

- Single syllable "touch and read": Students touch each letter with a finger or pencil point and say the letter sound, then sweep left to right below the word and read the word.

- Multi syllable touch and read: Students touch each syllable with a finger or pencil point and say the syllable, then sweep left to right below the word and read the word.

Include two or three of these multisensory activities in each lesson: speaking, listening, moving, touching, reading, and writing. They fully engage the brain and make learning more memorable. These activities can be fun games or part of a daily practice routine.

Multisensory activities are the scaffold for early practice. As students become proficient in the new skill or concept, reduce and then remove the multisensory scaffolds.

Back to top

Adapting instruction for different readers

Research supports explicit phonics instruction for beginning readers and for struggling readers whose reading skills did not develop as expected. Two areas that affect reading acquisition are working memory and executive function.

Working memory refers to the memory we use to hold and manipulate information. For example, when a beginning reader sounds out a word, the student holds the letter shapes, sequence, and sounds in working memory to first sound out the word, then blend the sounds and read the word. Information held in working memory is fragile and held briefly (approximately 10 seconds) unless actively engaged.

For example, when a beginning reader sounds out a word, the student holds the letter shapes, sequence, and sounds in working memory to first sound out the word, then blend the sounds and read the word. Information held in working memory is fragile and held briefly (approximately 10 seconds) unless actively engaged.

If not attended to, the information in working memory vanishes. While this is true for everyone, some of us sustain information in working memory for seconds longer, some for less time. There are techniques that help students practice attending to information in working memory. See the articles, 10 Strategies to Enhance Students' Memories and Making It Stick: Memorable Strategies to Enhance Learning.

Executive function refers to the part of the brain that governs attention, impulse (starting and stopping), organization, reasoning, processing speed, and other higher order functions. It is the area of the brain that gets things done. It is also the last area of the brain to fully mature (mid to late 20s). Learn more: Executive Function Fact Sheet.

Learn more: Executive Function Fact Sheet.

To support students who struggle with working memory, attention, executive function, or processing speed issues, the following instructional adaptations can be helpful:

Itemized instructions

Hand out itemized instructions, and discuss what is expected in each step. Teach students how to check each step in a process off the instruction sheet to track work completed. Students with working memory and executive function weaknesses benefit greatly from learning how to use lists.

Intermittent instructions

Whenever possible, provide intermittent instructions so students do not need to remember a long list of steps. Remind the class to check any itemized instructions.

Instructional routines

Use repeated routines to practice skills and complete assignments. Repeated routines are not boring to students. They reduce the memory load on students and enable them to focus on new skills or concepts.

Repeat-safe environment

Build into the explicit instruction, practice, and assessment an opportunity to repeat instructions or information. It can be as simple as, “Anyone need me to repeat that?” or “Can I repeat the instructions for the next steps?” or “Remember. You can always ask me to repeat something.” This creates an environment in which students with attention or working memory weaknesses feel safe asking for instructions or information to be repeated.

It can be as simple as, “Anyone need me to repeat that?” or “Can I repeat the instructions for the next steps?” or “Remember. You can always ask me to repeat something.” This creates an environment in which students with attention or working memory weaknesses feel safe asking for instructions or information to be repeated.

Rehearsing

Rehearsing can include having students state something aloud before writing. It can also include briefly practicing an activity that will later be assigned as homework. By rehearsing, a procedural memory or episodic memory is created which later supports students when they attempt to work independently.

Note taking

Explicitly teach note taking and build it into classroom routines. Every student will benefit by note taking as a study skill, as a stage of writing, and as an organizational tool. There are different note taking strategies depending on the task. Explicitly teach those note-taking strategies, and build them into lesson procedures. If students learn multiple note-taking strategies, you will need to review with them which one to implement in each setting, especially for students who struggle with working memory or executive function.

If students learn multiple note-taking strategies, you will need to review with them which one to implement in each setting, especially for students who struggle with working memory or executive function.

Writing aids

- Provide a list of words pertinent to the writing assignment which have new or difficult spellings. This reduces the load on working memory by helping remove an obstacle to writing.

- Provide an itemized rubric of the things the writing assignment must contain and explicitly teach the class to review their writing for each item on the list. Students with working memory weaknesses cannot easily review their writing for multiple things (e.g., check punctuation at the same time as checking for at least three supporting details and the reasons they support the topic sentence).

Organizational and place-keeping strategies

Being organized and knowing how to break a complex task into subtasks are not always innate skills. This is especially true for students with working memory and executive function weaknesses.

We support all students by taking time to explicitly teach how to be organized: how to organize a binder, how to break a complex task into logical steps, how to allocate time on homework, etc. This requires more time at first, but as the school year progresses, less time is required. Students will benefit from this skill set through the rest of their academic careers.

Back to top

References

Barkley, R. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 65–94.

Gathercole, S. and Alloway, T. (2008). Working memory and learning: A practical guide for teachers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Giedd J., Blumenthal J., Jeffries N., Castellanos F., Liu H., Zijdenbos A., Paus T., Evans A., & Rapoport J. (1999). Brain development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal MRI study. Nature Neuroscience 2(10), 861–3.

Next: Phonics Assignments >

Methods of studying phonetics.

Purposes of studying phonetics - to reveal to students the role of the sound side of the language, to show the connection of the latter with vocabulary and grammar.

Cognitive goals : to give schoolchildren an idea about the sound system of the Russian language, to prevent everyday mixing of sound and letters, to acquaint them with the norms of literary pronunciation.

Practical goals : formation of educational and linguistic (phonetic) phenomena: to recognize the sounds of the Russian language, classify them by analyzing the sound composition of the word (phonetic analysis), apply to orthograms

Speech skills : development of pronunciation and auditory culture.

In training content includes knowledge and skills. The main unit of the phonetic level of the language is represented in the school course by sound.

Sound is considered in 3 aspects: functional, physiological and acoustic. From a physiological point of view, sound is considered as a system, a creative product of the organs of speech and articulation. By virtue of the fixed everyday idea of a soft sign about the identity of a letter and sound in those words where softness in writing is indicated by a soft sign. From an acoustic point of view, speech sounds are considered as physical phenomena perceived by the organ of hearing, the ratio of voice and noise. From a functional point of view, the sounds of speech are studied in their relation to the semantic side of speech.

The content of the phonetics course includes the study of the sounds of the Russian language as a system. The concept of opposition of sound units is learned if the teacher pays attention to the following wording: Most voiced and voiceless consonants, hard and soft, form pairs. The main thing in the teacher's work should be the education of speech culture.

The content of studying phonetics at school includes consolidating students' knowledge about the syllable . In grade 5, it seems appropriate for them to offer words with the simplest cases of syllable division (ci-lindr) during phonetic analysis, or we ask you to indicate only the total number of syllables. At school, students learn the rules of word wrapping.

Principles :

1. Relying on the speech hearing of the students themselves,

2. consideration of sound in a morpheme,

3. Comparison of sound and letter.

When studying phonetics, the most common methods are observation of the sound side of speech, use in pronunciation, sound-letter (phonetic) analysis, grouping of words with certain sounds, and installation reading. When organizing observations, one must take into account the principle from sound to letter (Peshkovsky).

Phonetic analysis is not only a learning technique, but also a means of consolidating, generalizing and repeating information on phonetics. The order of phonetic analysis: 1. Syllables, stress, 2. Vowels: stressed, unstressed, 3. Consonants: voiced / deaf, soft / hard, 4. number of letters and sounds.

The order of phonetic analysis: 1. Syllables, stress, 2. Vowels: stressed, unstressed, 3. Consonants: voiced / deaf, soft / hard, 4. number of letters and sounds.

Pay attention to speech. A letter stands for a sound, a sound stands for a letter. Interest in the study of phonetics is created through the use of game tasks, search tasks. These techniques activate students and contribute to the formation of distinguish between sound and letter.

Attention!

If you need help writing a paper, we recommend that you contact professionals. Over 70,000 authors are ready to help you right now. Free corrections and improvements. Find out the value of your work.

Calculation costGuaranteesReviews

We will help you to write any work for a similar subject

-

Abstract

Methods of studying phonetics.

From 250 rubles

-

Control job

Methods of studying phonetics.

From 250 rubles

-

Coursework

Methods of studying phonetics.

From 700 rubles

Get a job done or expert advice on your educational project

Find out the cost

What does phonetics study? - "Virtual Academy"

- Home →

- News→

- What does phonetics study?

Each of us at school learned not only Russian, but also a foreign language. However, over the years, most of what was studied in school years has been forgotten. And now you are unlikely to remember, for example, what phonetics studies.

And now you are unlikely to remember, for example, what phonetics studies.

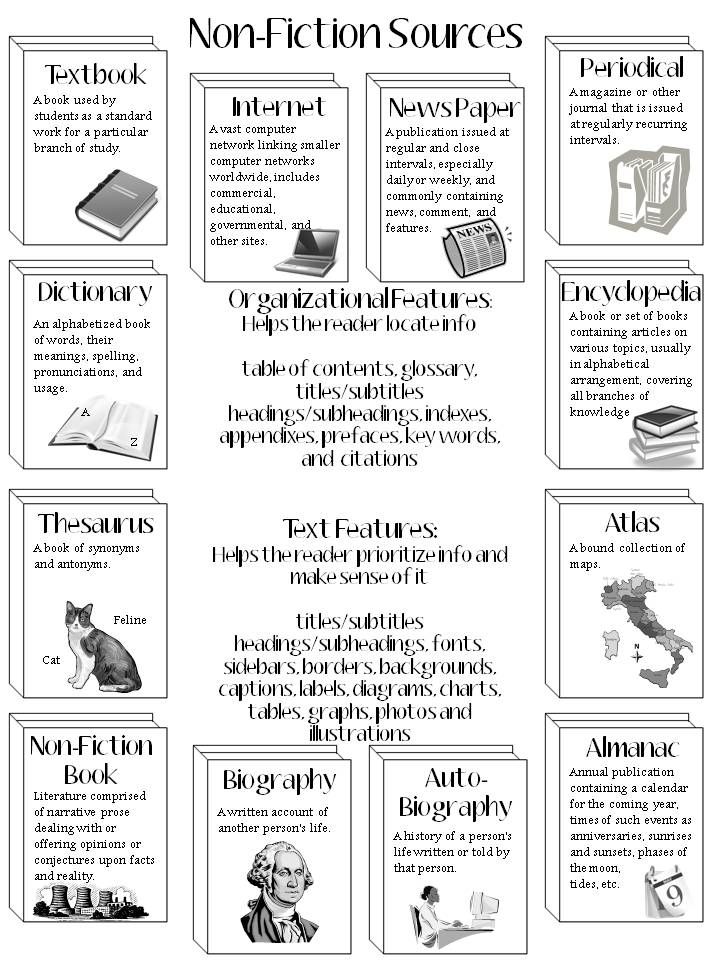

Phonetics describes the sound composition and basic sound processes of a language. This is a section of linguistics that studies the sound units of a language (sound combinations, syllables, patterns of connecting sounds into a speech chain).

Phonetics is an independent branch of linguistics, which has its own subject and tasks. The subject of this section of linguistics is the relationship between oral, written and inner speech. Phonetics, unlike other linguistic disciplines, in addition to the language function, also studies the material side of its object, namely the work of the pronunciation apparatus, the acoustic characteristics of sound phenomena, as well as their perception by native speakers. In addition, phonetics considers sound phenomena as elements of a language system that serve to translate words into a material sound form.

Tasks of phonetics:

- to establish the sound composition of the language in a certain period of its development;

- learn a language in a static state or in development;

- determine changes in speech sounds, find out the reasons for these changes;

- to study the phonetic phenomena of the language in comparison with the phonetic phenomena of related languages;

- study the sound structures of several languages in order to find their common and specific.

Like all linguistic sciences, phonetics studies linguistic phenomena in terms of diachrony or synchrony. The study of phonetics in terms of diachrony is the study of phonetic phenomena in change, time, or in the transition of one phenomenon to another. The study of phonetics in terms of synchrony is the study of the phonetics of a language as a ready-made system of interdependent elements.

What does phonetics study? These can be phonetic systems of individual languages (the so-called private phonetics). There is also a general phonetics that studies the sounds of speech of all languages. It determines the possibilities of articulation of sounds by the speech apparatus, finds out the general sound laws in languages, explores the nature of sounds, analyzes the conditions for their formation, studies syllable, intonation, and stress.

Also distinguished:

- Comparative phonetics, which compares the sound system of a language with other languages. This is necessary in order to see and learn the features of a foreign language. However, such a comparison also helps to shed light on the laws of the native language. In some cases, the comparison of related languages allows one to penetrate deep into their history.

However, such a comparison also helps to shed light on the laws of the native language. In some cases, the comparison of related languages allows one to penetrate deep into their history.

- Historical phonetics, tracing the development of a language over a long period of time.

- Descriptive phonetics, considering the sound structure of a particular language at a certain stage.

- Articulatory phonetics, considering the anatomical and physiological basis of the speech apparatus and the mechanisms of speech production.

- Perceptual phonetics, which studies the features of the perception of sounds by the human organ of hearing. Perceptual phonetics is designed to answer the question of what sound properties are essential for human speech perception (for example, for phoneme recognition), taking into account the changing articulatory and acoustic characteristics of speech signals. It also takes into account the fact that in the process of perceiving sounding speech, people extract information not only from the acoustic properties of a particular statement, but also from the linguistic context and the situation of communication, predicting the general meaning of the message. Perceptual phonetics reveals the specific and universal perceptual characteristics that are inherent in the sounds of a language in general and the sounds of specific languages.

Perceptual phonetics reveals the specific and universal perceptual characteristics that are inherent in the sounds of a language in general and the sounds of specific languages.

Depending on the goals facing phonetics, practical and theoretical phonetics are distinguished. Theoretical phonetics solves issues related to the sound side of the language, the conditions for the formation of sounds, the patterns of change and combination of sounds, the division of the speech flow. The study of the sound side of the language makes it possible to understand grammatical phenomena, explains the historical processes of the development of the language.

What does practical phonetics study? First of all, it relies on the provisions of theoretical phonetics. The study of sounds in practice is important for setting the correct pronunciation of the sounds of the language, for spelling, and so on. These phonetics are used in deaf pedagogy and speech therapy.

Three aspects of phonetic research can be distinguished:

- anatomical and physiological - explores speech sounds from the point of view of their creation;

- acoustic - considers sound as an air vibration, fixing its physical characteristics: duration, frequency and strength;

- functional - studies the functions of sounds, operates with phonemes.

At first glance, phonetics may seem like a boring subject, but for those who are seriously interested in linguistics and learn foreign languages, the study of the sound units of a language is of great interest.

An interesting article? Share it with others:

-

08.12.2021

What percentage of words in Russian are borrowed

-

24.10.2021

Education in England for Russians after grade 11

-

07/12/2021

The most important words in English with transcription

-

06/21/2021

How many words does a native English speaker know

-

06/09/2021

How many words are used in English

-

31.

01.2022

01.2022 How to choose a tutor for distance learning

-

24.01.2022

Where to get a decent musical education in Moscow

-

01/17/2022

Why do schoolchildren write off

-

10.01.2022

What are the advantages of the Olympiad for schoolchildren

-

01/03/2022

Where to apply after graduating from medical college

-

08/27/2021

Calculation of the number of days for sowing

-

08/27/2021

Difference between highest and lowest temperature

-

27.

Learn more