Learning sounds for reading

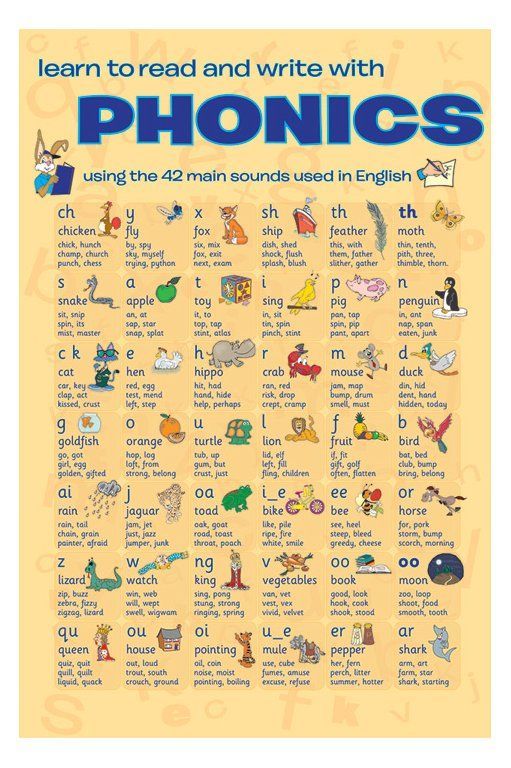

Phonics: In Practice | Reading Rockets

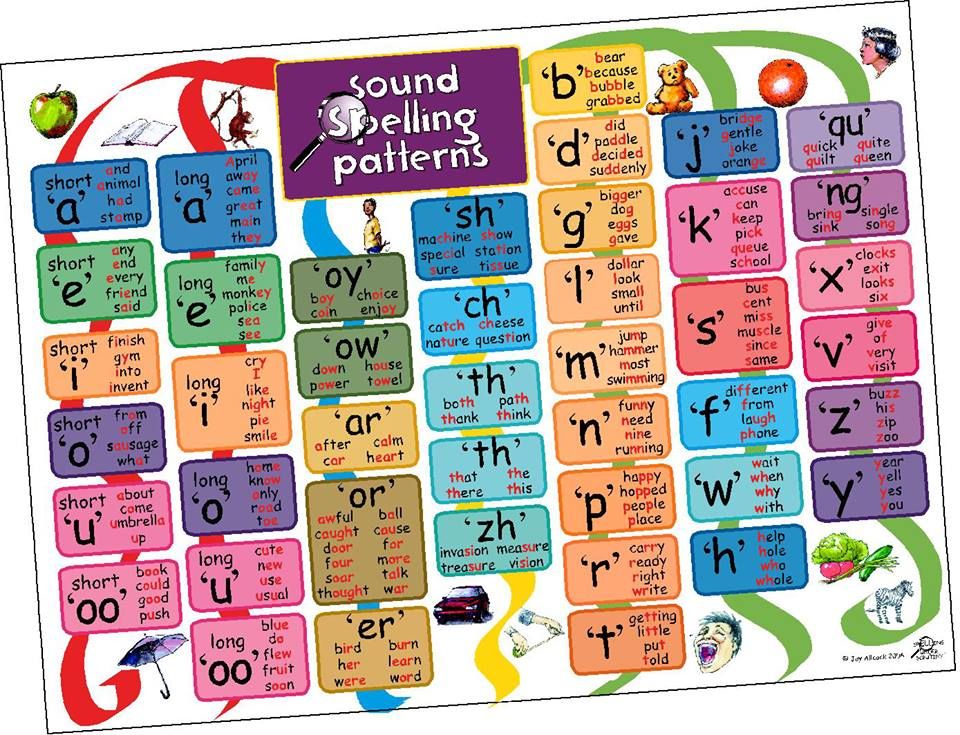

Phonics instruction teaches common letter-sound relationships, including sounds for common letter patterns, so that readers can apply them in decoding unfamiliar words.

The purpose of phonics instruction

In this section:

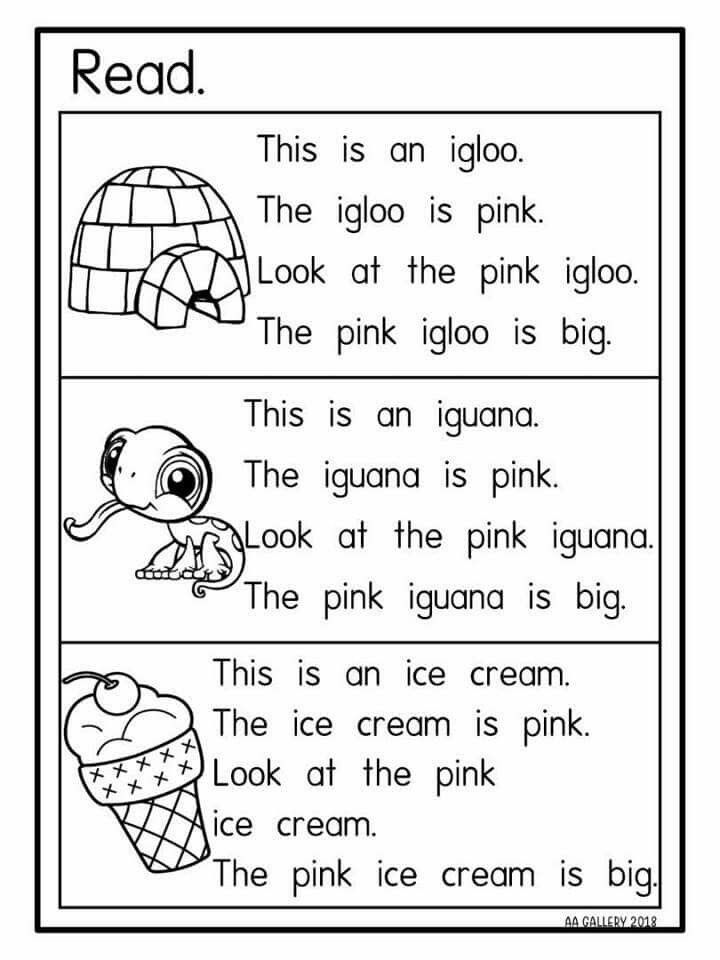

Only a small percentage of English words have irregular spellings and letter-sound relationships. This means that nearly all English words can be read by applying knowledge of letter-sound relationships and blending sounds together to form a whole word. To learn more, see How Words Cast Their Spell.

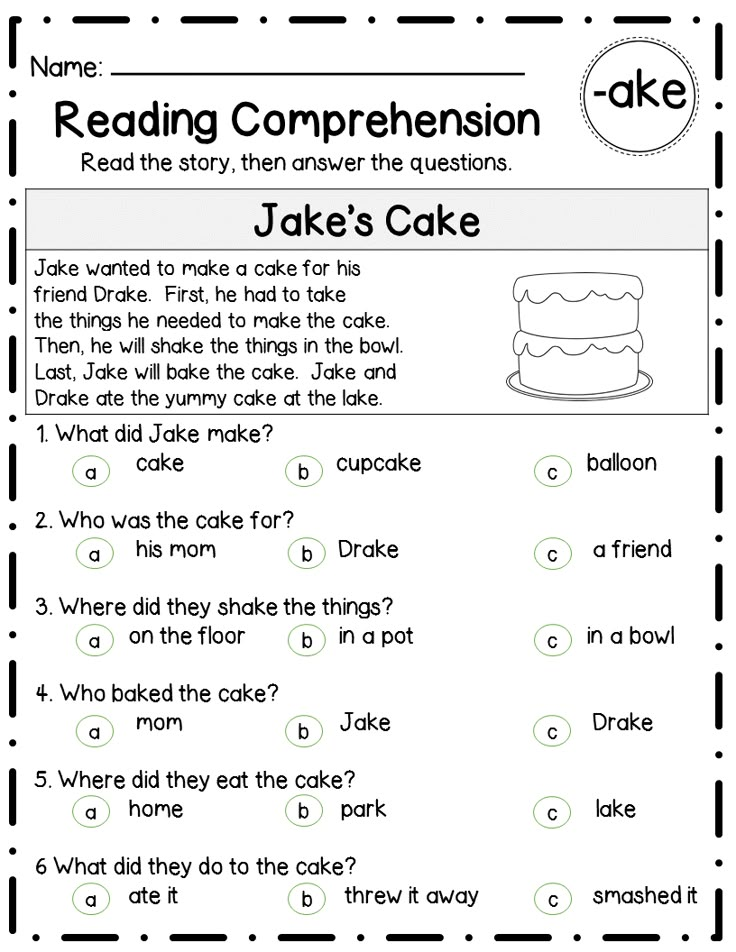

Being able to decode words effortlessly (convert spelling into speech sounds) means children are able to focus their attention on comprehending what they read.

Beginning phonics lessons

Regardless of grade, start phonics lessons with consonant letter sounds that are easy to pronounce and less often confused with similar letter sounds. This enables students to master one letter sound before having to learn a similar letter sound. For example, students may confuse the letter sounds for t and d. Since the letter t is more common, instruction should introduce t many lessons before introducing d.

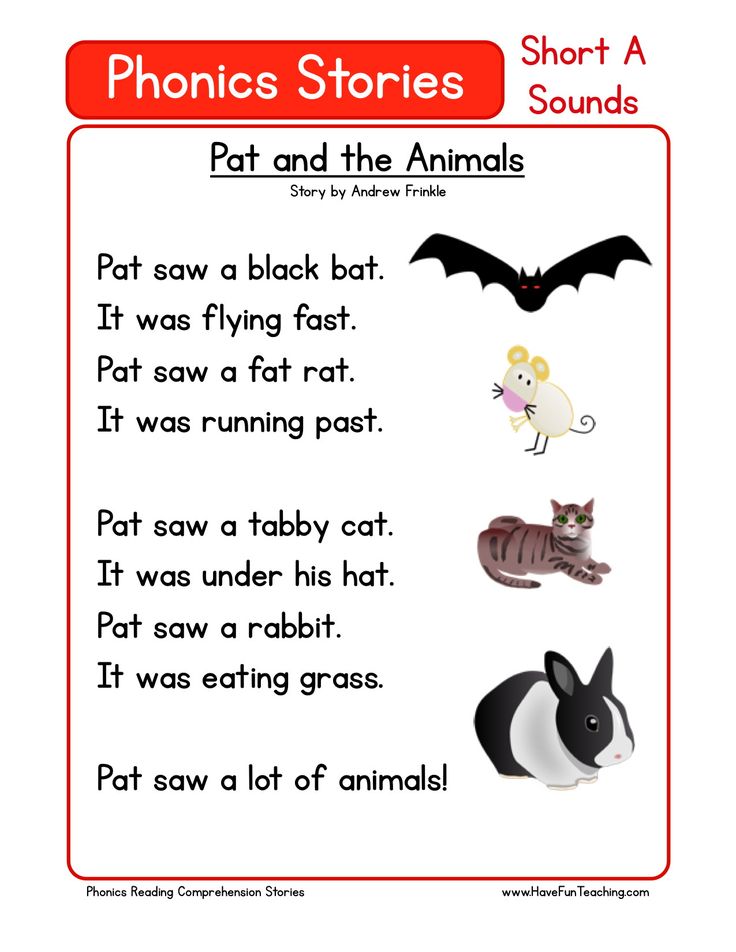

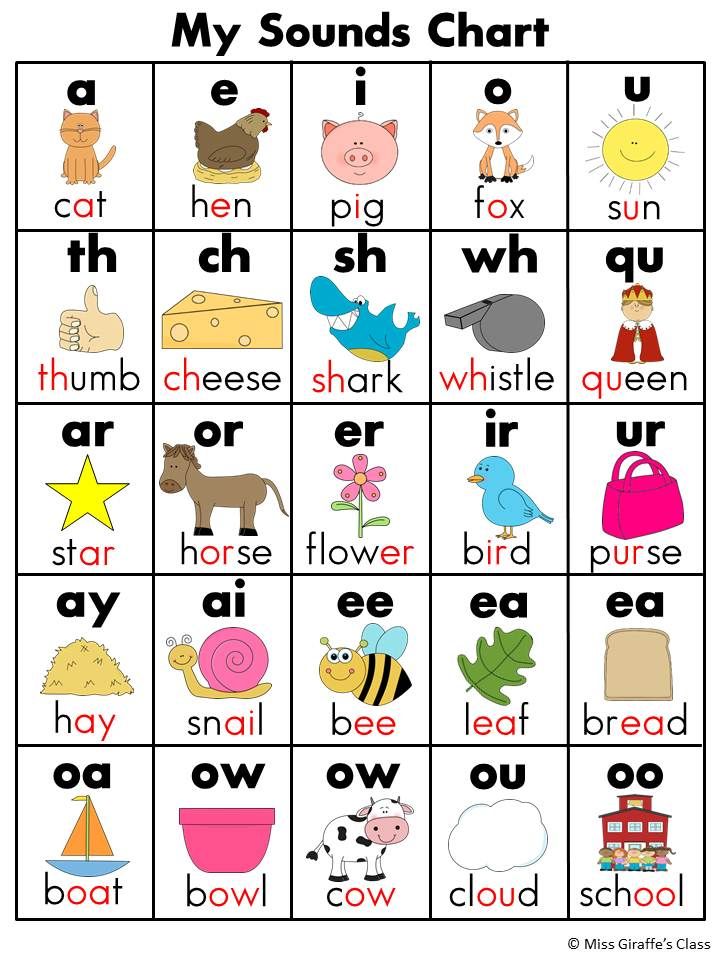

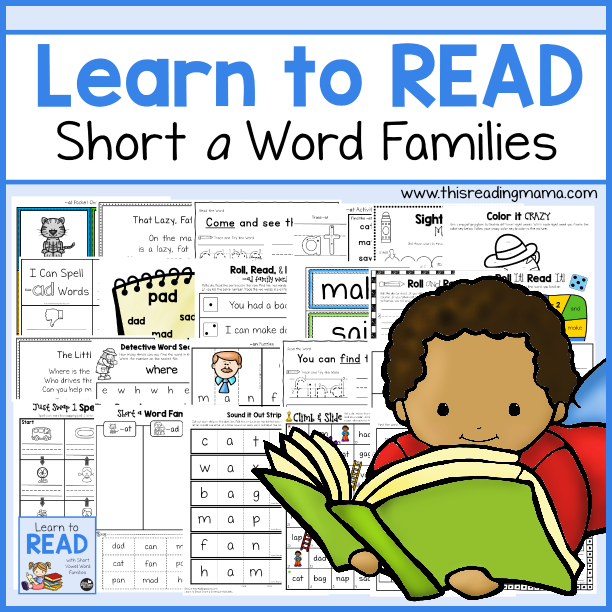

Learning sounds for letters is basically rote learning, and for rote learning, the use of memory cues can be very helpful. For instance, for short a, children can learn that the letter a looks like an apple with a broken stem, and short a represents /a/ as in apple. Multi-sensory activities, such as repeatedly tracing the vowel letter and saying its sound, are often useful as well.

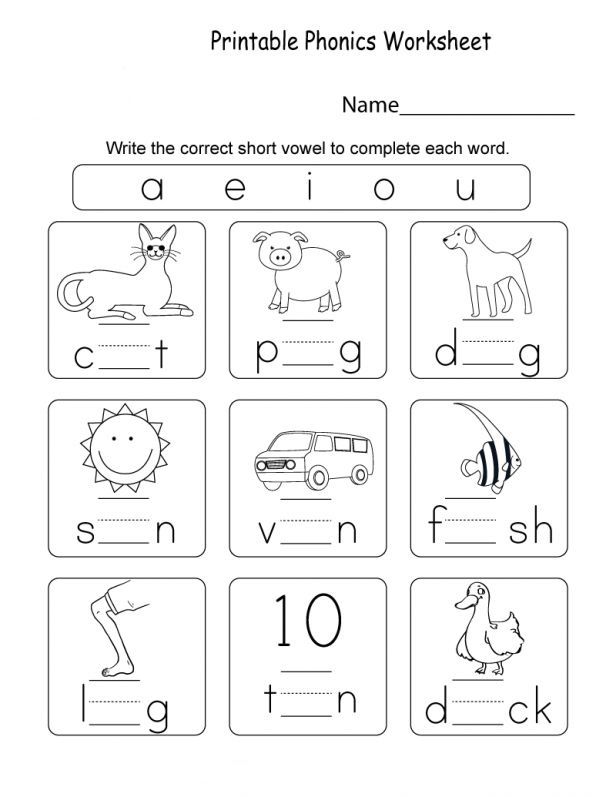

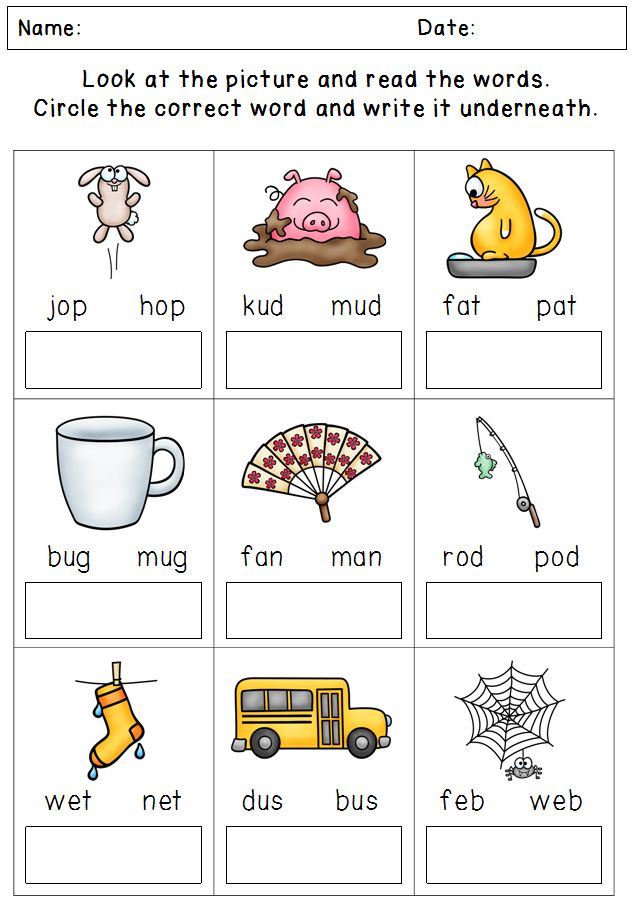

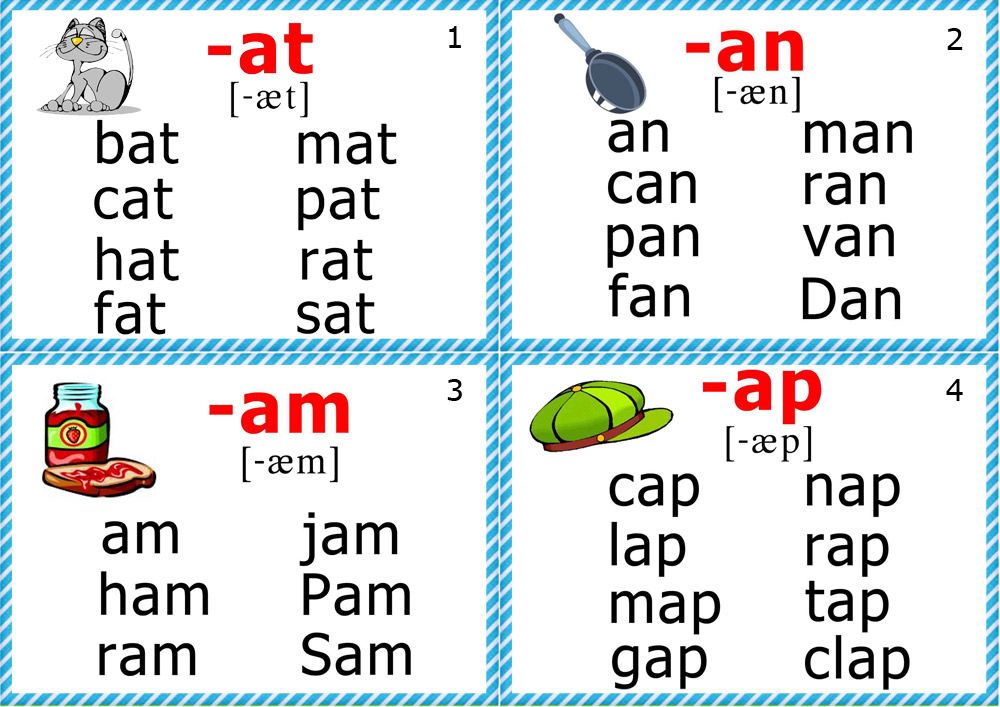

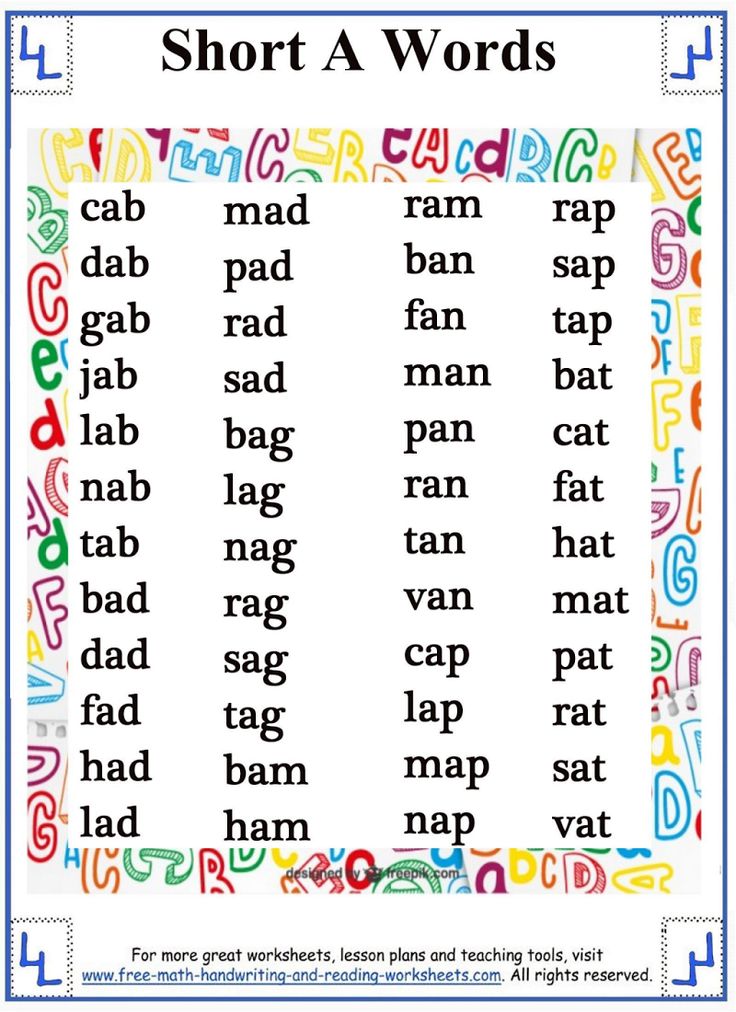

Start explicit phonics instruction with short vowel words because these vowels have one predictable spelling (with few exceptions) and are the most commonly occurring vowel sounds in English. Because the short vowel sounds are highly confusable, they should be taught individually, not all at the same time.

Phonics Terms

- Phoneme

The smallest unit of sound in our spoken language. Pronouncing the word cat involves blending three phonemes: /k/ /ae/ /t/.

Pronouncing the word cat involves blending three phonemes: /k/ /ae/ /t/. - Grapheme

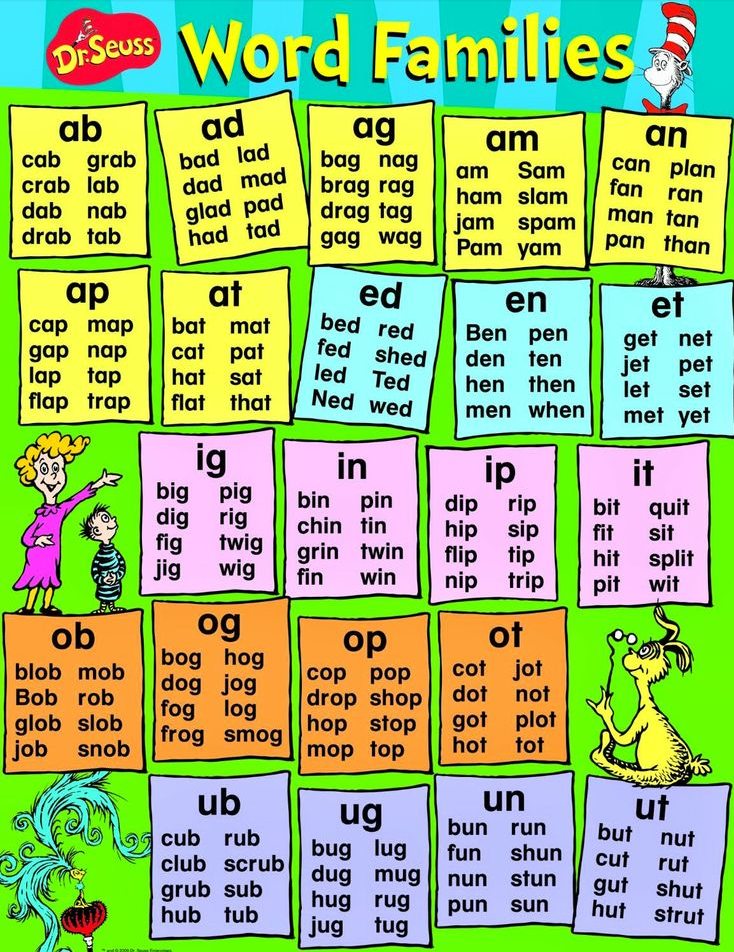

A written letter or a group of letters representing one speech sound. Examples: b, sh, ch, igh, eigh. - Onset

An initial consonant or consonant cluster. In the word name, n is the onset; in the word blue, bl is the onset. - Rime

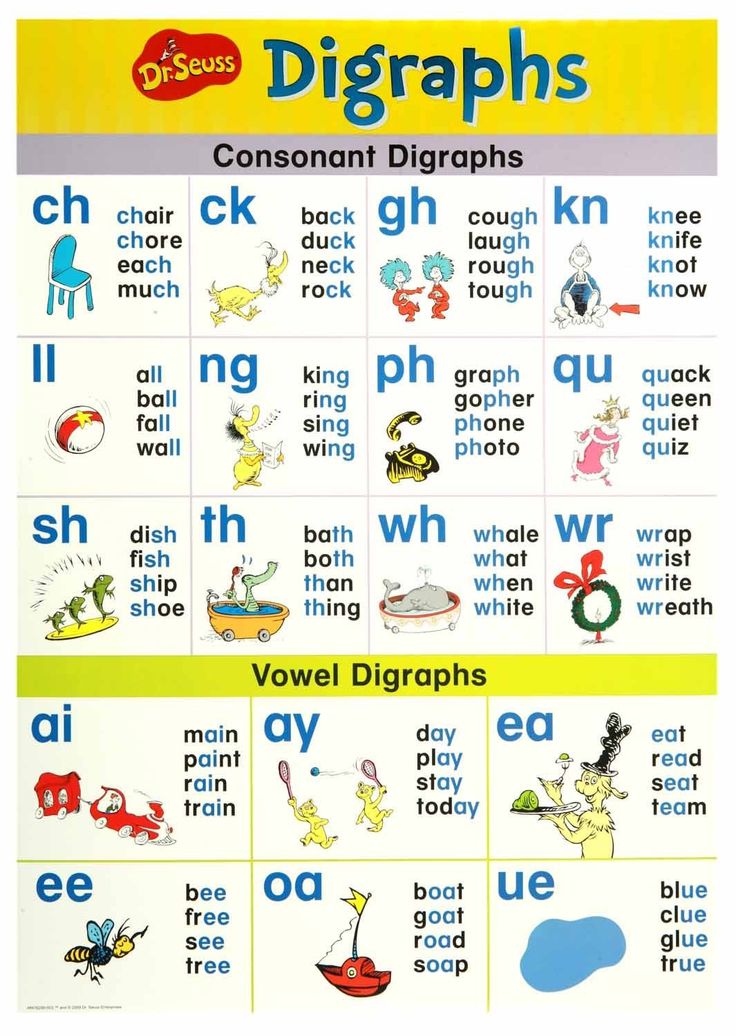

The vowel or vowel and consonant(s) that follow the onset. In the word name, ame is the rime. - Digraph

Two letters that represent one speech sound (diphthong). Examples: sh, ch, th, ph. - Vowel digraph

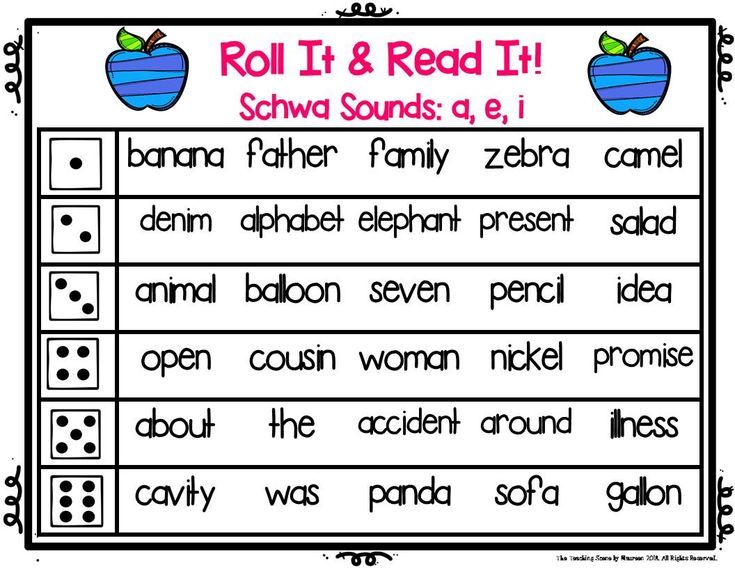

Two letters that together make one vowel sound. Examples: ai, oo, ow. - Schwa

The vowel sound sometimes heard in an unstressed syllable and that most often sounds like /uh/ or the short /u/ sound. Example: the "a" in again or balloon. All English vowels have a schwa sound.

Example: the "a" in again or balloon. All English vowels have a schwa sound. - Morpheme

The smallest meaningful units of language. The word cat is a morpheme. Not all morphemes stand alone as words; some are attached to words, usually as affixes. These are called bound morphemes. Examples include: non-, -est, -ing, -er, -ion.

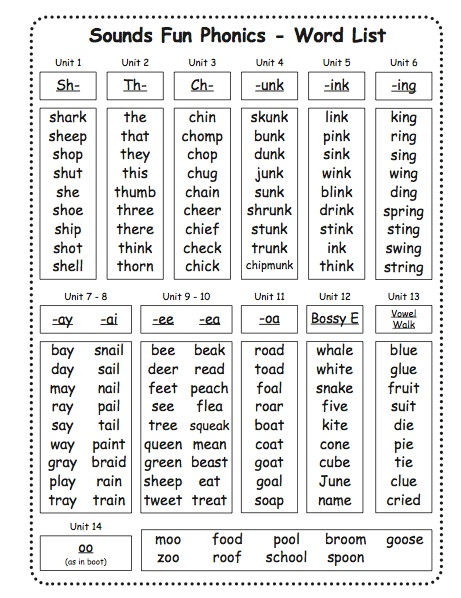

Kindergarten phonics lessons

Phonics lessons in kindergarten focus on students becoming automatic at letter naming, single-grapheme letter sounds, and reading single-syllable words with short vowel spellings. Instruction may include common digraphs (ch, sh, th, wh, and ck). For some kindergarten students, articulating some consonant sounds may be difficult, but this does not prevent them from reading and comprehending words with those sounds.

To learn more about when kids learn different consonant sounds, see this Speech-Sound Development chart.

Back to top

First grade phonics lessons

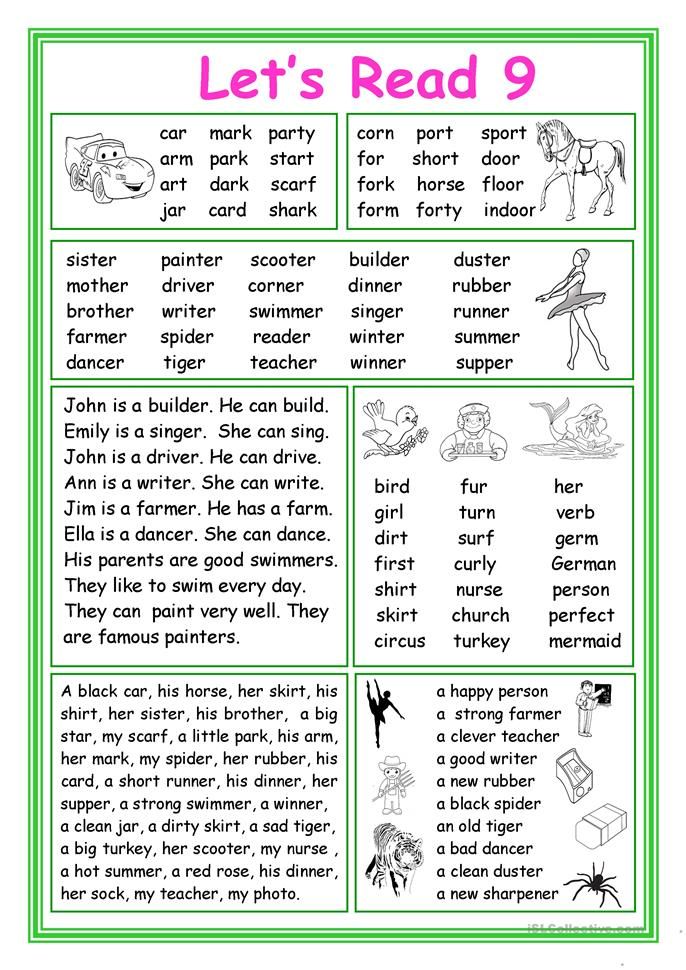

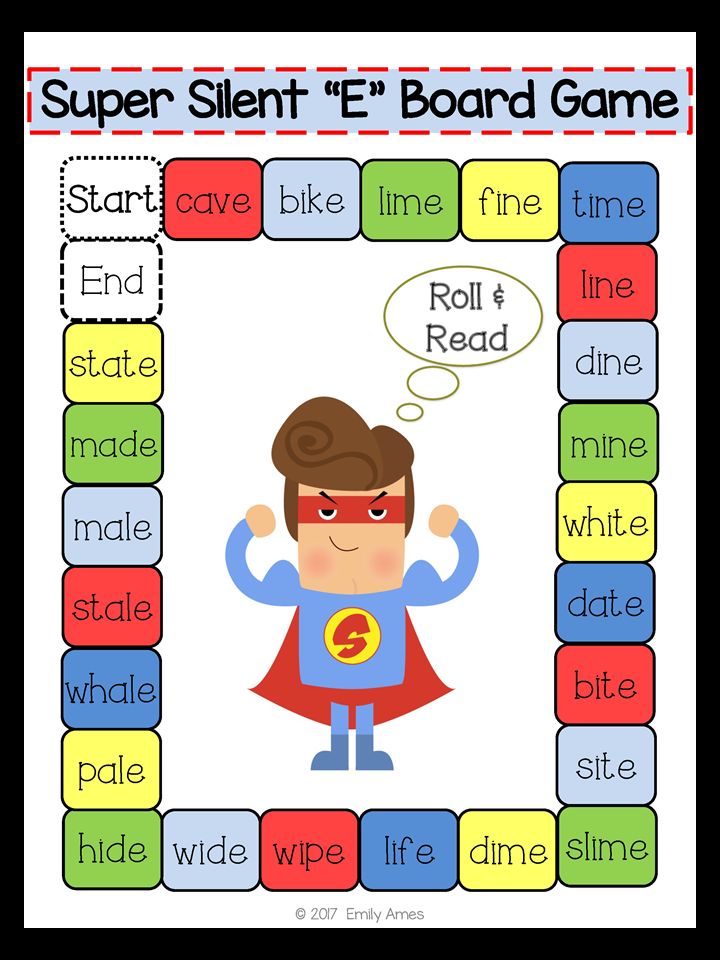

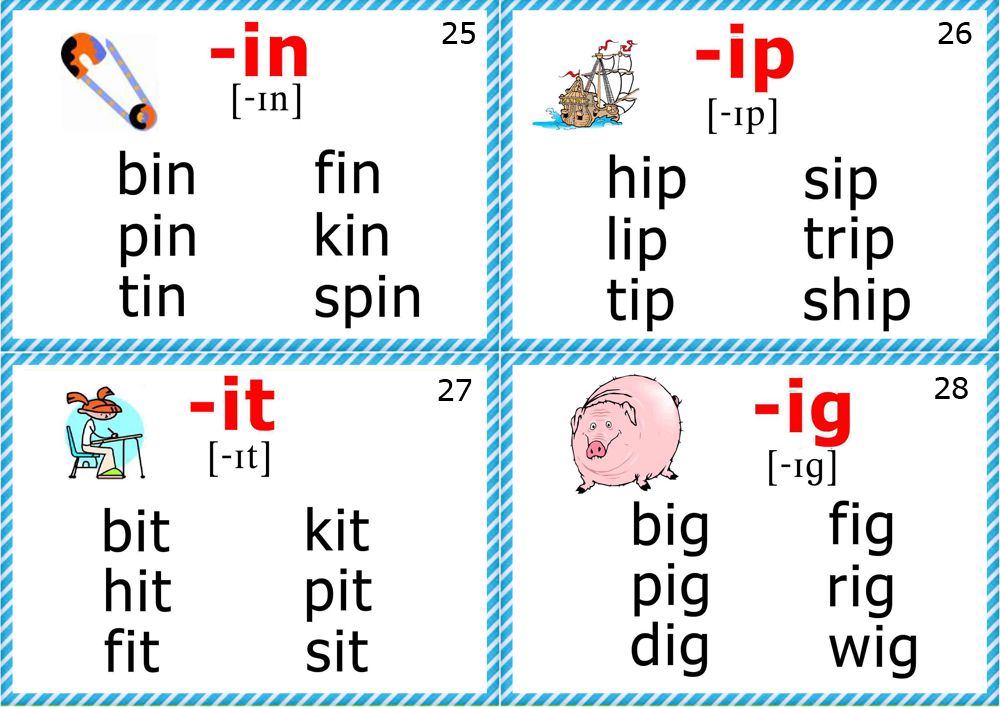

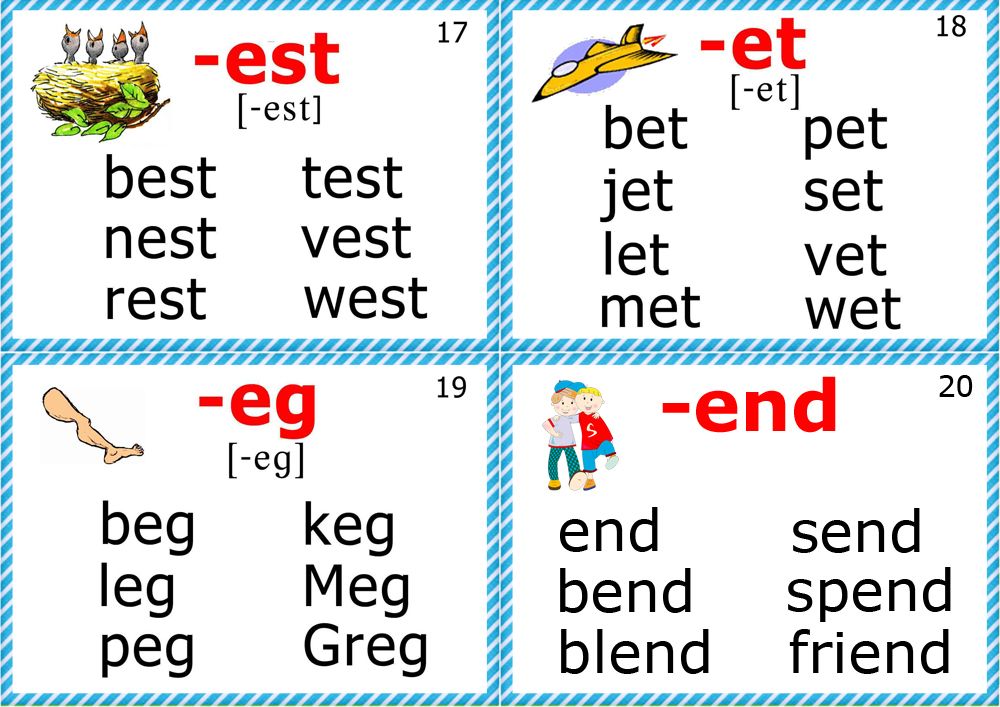

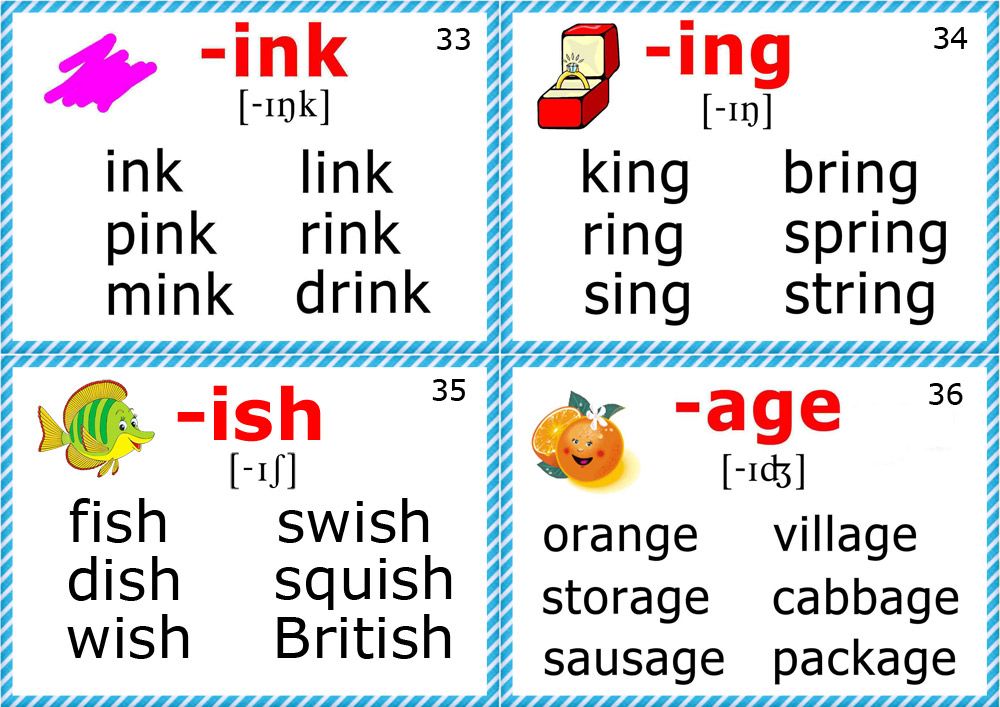

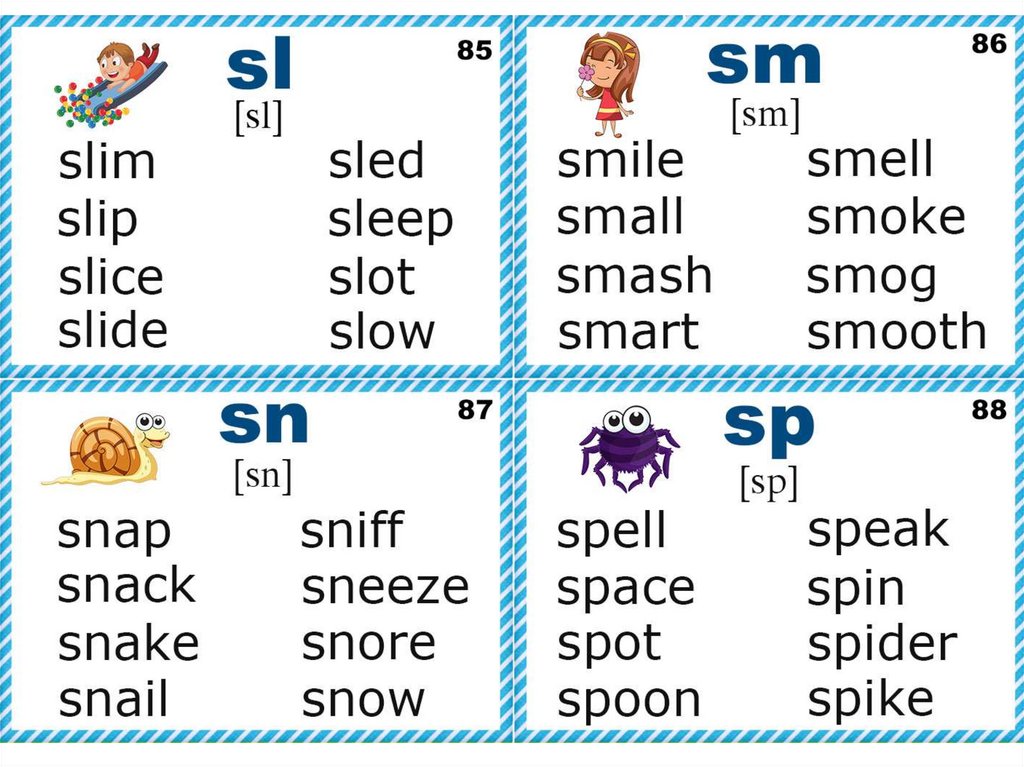

In first grade, phonics lessons start with the most common single-letter graphemes and digraphs (ch, sh, th, wh, and ck). Continue to practice words with short vowels and teach trigraphs (tch, dge). When students are proficient with earlier skills, teach consonant blends (such as tr, cl, and sp).

Ensure students understand the difference between blends, digraphs, and trigraphs: that each letter in a blend retains its own sound, while the letters in digraphs and trigraphs represent one sound.

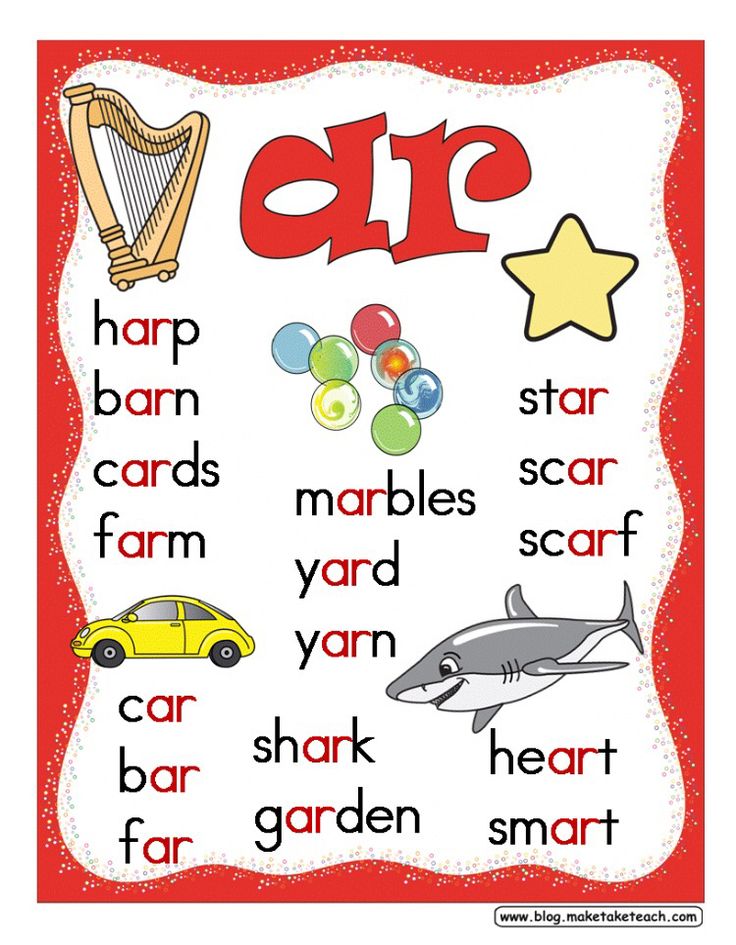

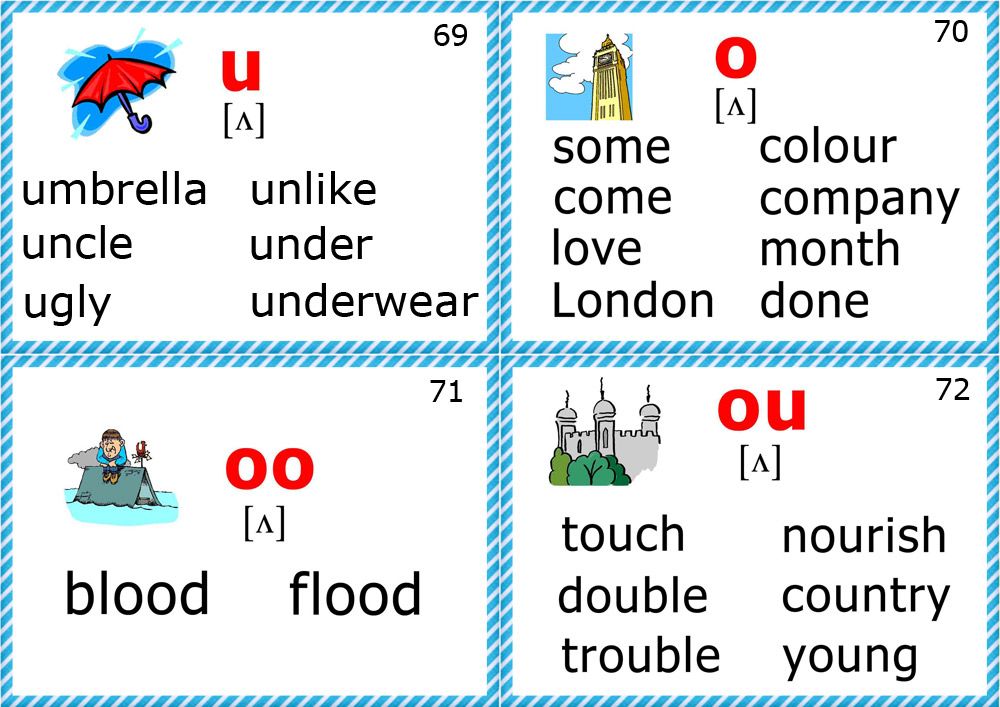

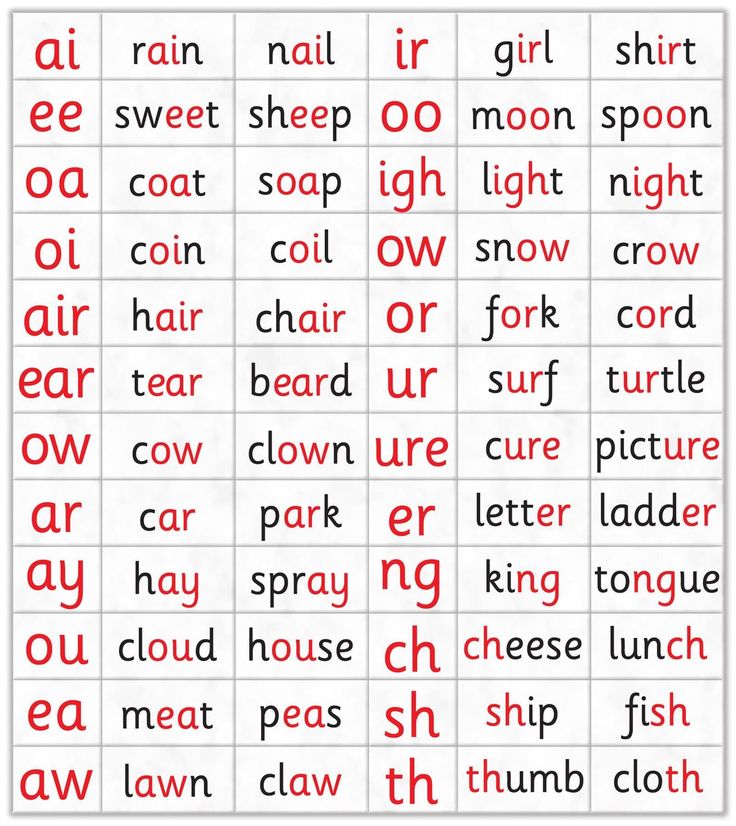

In first grade, we may also include two-syllable words with short vowel sounds (e.g., cat∙fish, pic∙nic, kit∙chen). Inflectional endings such as ing, er, and s would also be included. When students have mastered short vowel spelling patterns, introduce r-controlled (e.g., er, ur, or, ar), long vowel (e. g., oa, ee, ai), and other vowel sound spellings (e.g., oi, aw, oo, ou, ow

).

g., oa, ee, ai), and other vowel sound spellings (e.g., oi, aw, oo, ou, ow

).

Teaching of common syllable types is also very useful for first-graders. By the end of first grade, typical readers should be able to decode a wide range of phonetically regular one-syllable words with all of these letter patterns and syllable types, including one-syllable words with common inflectional endings (e.g., sliding, barked, sooner, floated).

Teaching syllable types in first grade

Teaching children about syllable types is useful because vowel sounds in English vary, and knowledge about syllable types can help children determine the vowel sound of a one-syllable word. Later, once they have learned some rules for dividing long words, children can also apply their knowledge of syllable types to decode two-syllable and multisyllabic words.

Instruction in syllable types should focus on children’s abilities to classify words correctly (e. g., sort one-syllable words that are closed from one-syllable words that are not closed) rather than on children’s abilities to recite rules or definitions. However, it is very important for us to present clear, consistent definitions of the syllable types, in order to avoid inadvertently confusing instruction.

g., sort one-syllable words that are closed from one-syllable words that are not closed) rather than on children’s abilities to recite rules or definitions. However, it is very important for us to present clear, consistent definitions of the syllable types, in order to avoid inadvertently confusing instruction.

The six syllable types common in English are closed, silent e, open, vowel combination, vowel r, and consonant-le. The chart below lists these syllable types along with their typical vowel sounds, definitions, some examples, and some additional comments.

The specific order in which syllable types are taught can vary substantially, depending on the phonics program being used. However, the closed syllable type is usually taught first, because closed syllables are common in English, and it is virtually impossible to write even a very simple story for children that contains no closed syllables. Conversely, consonant-le syllables always occur as part of two-syllable (or longer) words, so that syllable type would often be taught last.

| Syllable Type (Synonyms) | Vowel Sound | Definition | Examples | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed | Short | Has only one vowel and ends in a consonant. | splash, lend, in, top, ask, thump, frog, mess | The main prerequisite when children learn the closed syllable type is that they first have to be able to classify letters as either vowels or consonants. |

| Silent e (magic e) | Long | Has a –VCE pattern (one vowel, followed by one consonant, followed by a silent e that ends the syllable) | plane, tide, use, chime, theme, ape, stroke, hope | Words like noise, prince, and dance are not silent e, even though they end in a silent e, because they do not have the -VCE pattern; noise has a –VVCE pattern and prince and dance have a -VCCE pattern. |

| Open | Long | Has only one vowel that is the last letter of the syllable. | he, she, we, no, go, flu, by, spy | This syllable type becomes especially useful as children progress to two-syllable words. For example, the ti in title, lo in lotion, and ra in raven are all open syllables. |

| Vowel combination (vowel team) | Varies depending on the specific vowel pattern; children must memorize sounds for these individual vowel patterns. | Has a vowel pattern in it (e.g., ay, ai, aw, all, ie, igh, ow, ee, ea). | stay, plain, straw, fall, pie, piece, night, grow, cow | Vowel patterns do not always involve two vowels but can also consist of a vowel plus consonants, if this pattern has a consistent sound (e.g, igh almost always represents long /i/; all almost always represents /all/). Also, some vowel patterns can have more than one sound. For example, ow can represent long /o/ as in grow or /ow/ as in cow. For these patterns, children learn both sounds and, when decoding an unfamiliar word, they try both sounds to see which one makes a real word. For example, ow can represent long /o/ as in grow or /ow/ as in cow. For these patterns, children learn both sounds and, when decoding an unfamiliar word, they try both sounds to see which one makes a real word. |

| Vowel r (bossy r, r- controlled) | Varies depending on the specific vowel r unit; children must memorize sounds for these units (e.g., ar, er, ir, or, ur). | Has only one vowel followed immediately by an r | ark, charm, her, herd, stir, born, fork, urn | Does not include words in which the vowel r unit is followed by an e (e.g., stare, cure, here) or in which the r follows a vowel combination (e.g., cheer, fair, board). These words can usually be taught as silent e (in the first case) or vowel combination (in the second). |

| Consonant-le | Schwa | Has a –CLE pattern (one consonant, followed by an l, followed by a silent e which ends the syllable) | -dle as in candle, -fle as in ruffle, -ple as in maple, -gle as in google, -tle as in title, -ble as in Bible | Consonant-le syllables never stand alone; they always are part of a longer word. Also, they are never the accented syllable of a longer word. Also, they are never the accented syllable of a longer word. |

Video: Learning ‘b’ and ‘d’ and Reading Short Vowel Words

In this video, reading expert Linda Farrell works with Aiko on a common letter reversal — confusing the letters ‘b’ and ‘d’. Ms. Farrell coaches Aiko to look at the letters during b/d practice and to look at the words while she works with Aiko to read short vowel words accurately. See more videos here: Looking at Reading Interventions.

Back to top

Second grade, third grade, and beyond

As students enter Grade 2, they should be learning to decode a wide range of two-syllable and then multisyllable (i.e., three syllables or more) words. Instruction in decoding these longer words should include attention to common syllable division patterns and syllabication rules.

Common syllable division patterns

To decode words of more than one syllable, children need a strategy for dividing longer words into manageable parts. They can then decode the individual syllables by applying their knowledge of syllable types and common letter-sound patterns, blending those syllables back into the whole word.

The chart below provides some useful generalizations for teaching students how to divide (syllabicate) two-syllable words with various common patterns, in order to decode them. These generalizations also are useful for decoding multisyllabic words, those with three or more syllables.

| Pattern | Generalization | Examples | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | In a compound word, divide between the two smaller words. | back/pack, lamp/shade, bed/room, bath/tub, work/book | To be a true compound word, each of the smaller words must carry meaning in the context of the word (e. g., carpet is not a compound word, because a carpet is not a pet for your car or a car for your pet). g., carpet is not a compound word, because a carpet is not a pet for your car or a car for your pet). |

| VCCV | If a word has a VCCV (vowel-consonant-consonant-vowel) pattern, divide between the two consonants. | or/bit, ig/loo, tun/nel, lan/tern, tar/get, vel/vet | There is an exception if the two consonants form a consonant digraph (a single sound), as in bishop, rather, gopher, or method. In these cases, treat the word as a VCV word, not VCCV (see below). |

| -CLE | If a word ends in a consonant-le syllable, always divide immediately before the -CLE. | ma/ple, stum/ble, i/dle, nee/dle, gig/gle, mar/ble, tur/tle | |

| -VCV | If a word has a VCV (vowel-consonant-vowel) pattern, first try dividing before the consonant and sounding out the resulting syllables; if that does not produce a recognizable word, try dividing after the consonant. | hu/mid, ra/ven, mu/sic, go/pher; plan/et, com/et, tim/id, bish/op, meth/od, rath/er | To recognize the correct alternative, the child needs to have the word in his/her oral vocabulary. If the student does not recognize the correct alternative, we can have them try both options (e.g., hu/mid with a long u vs. hum/id with a short u). Then, if necessary, just tell the child the correct pronunciation of the word, with a brief explanation of its meaning. |

| Prefix | In word with a prefix, divide immediately after the prefix. | pre/view, mis/trust, un/wise, re/mind, ex/port, un/veil | See below. |

| Suffix | In a word with a suffix, divide immediately before the suffix. | glad/ly, wise/ly, sad/ness, care/less, hope/ful, frag/ment, state/ment, na/ture, frac/tion | Depending on its origin, the base word in a word containing prefixes or suffixes will not always be a recognizable word. However, the key point is that, when dividing a longer word, prefixes and suffixes are units that always stay together as patterns; never divide in the middle of a prefix or in the middle of a suffix. However, the key point is that, when dividing a longer word, prefixes and suffixes are units that always stay together as patterns; never divide in the middle of a prefix or in the middle of a suffix. |

Continue explicit phonics instruction through second grade with increasingly complex spelling patterns. By third grade, shift explicit phonics instruction mostly to explicit morphology instruction. Students move from learning about letter/sound relationships to sounds for prefixes, suffixes, roots, base words, and combining forms.

Vocabulary and spelling can be integrated with instruction in reading words. For example, as children learn to read the root geo, they learn that it means earth and that it will have a stable spelling across related words such as geology, geologist, geological, geography, geographic, etc.

Although many word-reading skills are developed by the end of Grade 3, children may be learning some of these skills even beyond Grade 3. Developing an understanding of etymology (word origins) is one example of this more advanced kind of skill for reading words.

Developing an understanding of etymology (word origins) is one example of this more advanced kind of skill for reading words.

For instance, j is pronounced /h/ in words of Spanish origin, and this pronunciation is retained in English words borrowed from Spanish, such as jalapeno and junta.

As another example, words that end in –ique such as boutique, antique, and mystique are borrowed from French and retain the French pronunciation for this pattern, /eek/.

Children do not need to learn sounds for all letter patterns in every language, but if they understand that many words in English are borrowed from other languages, and that these words often retain at least part of their pronunciation in the original language, this can benefit their word reading as well as their spelling.

Back to top

Phonics lesson planning

Lesson plans for explicit phonics instruction start with a clear, achievable objective. An objective may be learning two to three new consonant sounds, one new vowel sound, or a new phonics concept (e.g., in one-syllable words, ck spells the sound /k/ after one vowel letter and only at the end of a word). Lesson plans will likely span many days and include multiple layers of instruction and practice.

An objective may be learning two to three new consonant sounds, one new vowel sound, or a new phonics concept (e.g., in one-syllable words, ck spells the sound /k/ after one vowel letter and only at the end of a word). Lesson plans will likely span many days and include multiple layers of instruction and practice.

Lesson plans can start with a review and include previously taught concepts throughout the lesson. Lessons pull forward everything taught previously.

New concepts (e.g., letter sounds) are explicitly taught before being practiced. All practice should include an “I do, We do, You do” practice. In “I do,” model the activity. In “We do,” guide the group through practice. In “You do,” have students practice individually and model proficiency.

Build scaffolded instruction and practice into activities. Each subsequent practice activity contains less scaffolding until students are independently proficient. Practice activities move from isolated skills to skills that are more complex. For example:

For example:

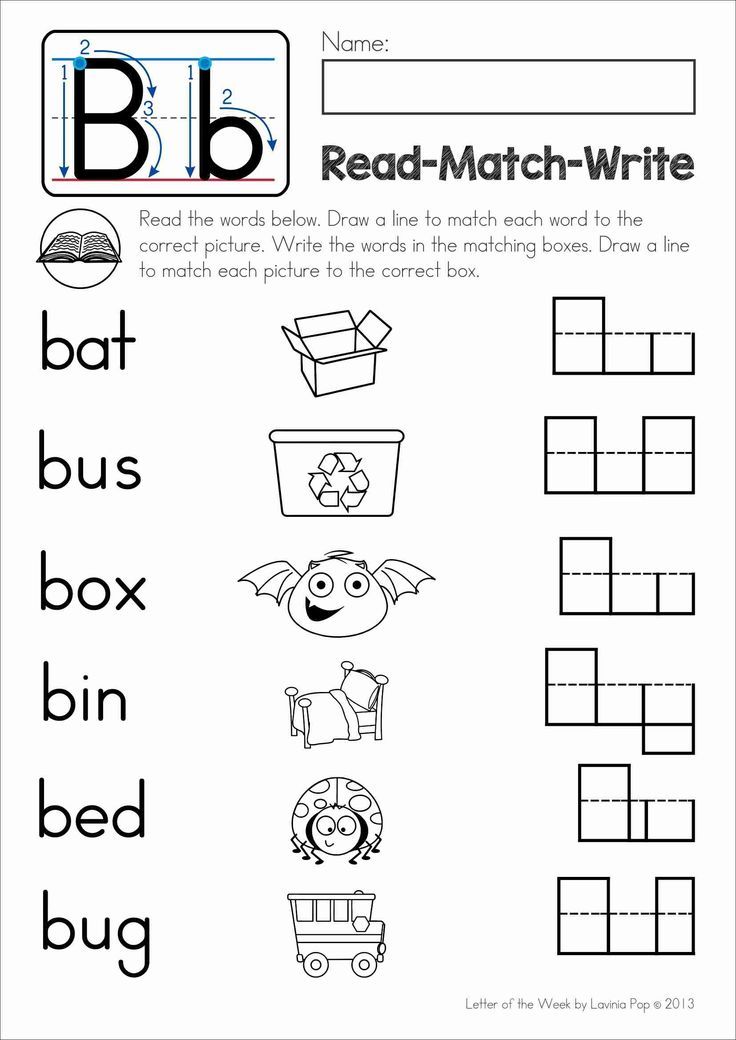

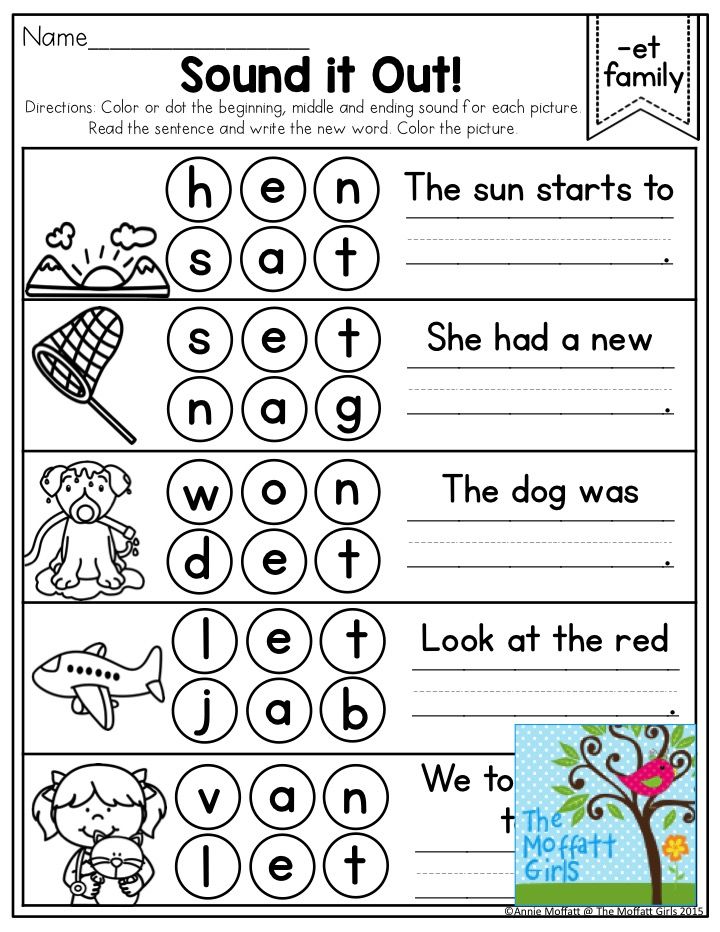

- Students read and spell letter name and letter sounds in isolation.

- Students read words sound by sound.

- Students read word chunks and word patterns.

- Students read whole words, sounding out only to resolve reading errors.

- Students spell words sound by sound, and practice spelling chains where only one letter changes from one word to the next (e.g., sap to lap to lip to lit to slit)

- Students may learn word meanings to understand sentences and passages, but vocabulary instruction is typically outside the phonics instruction block.

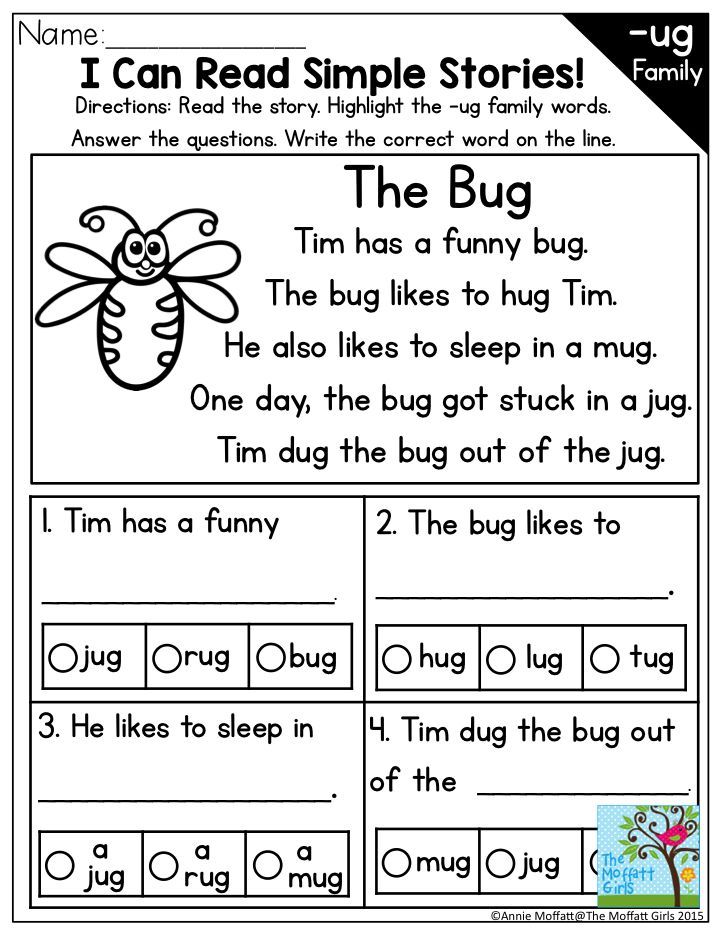

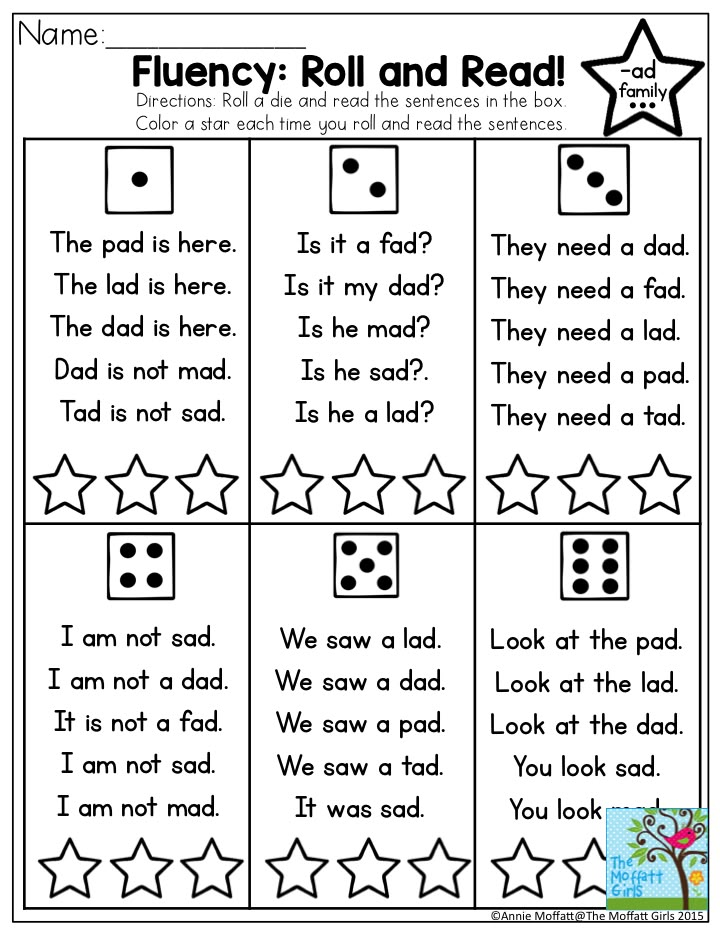

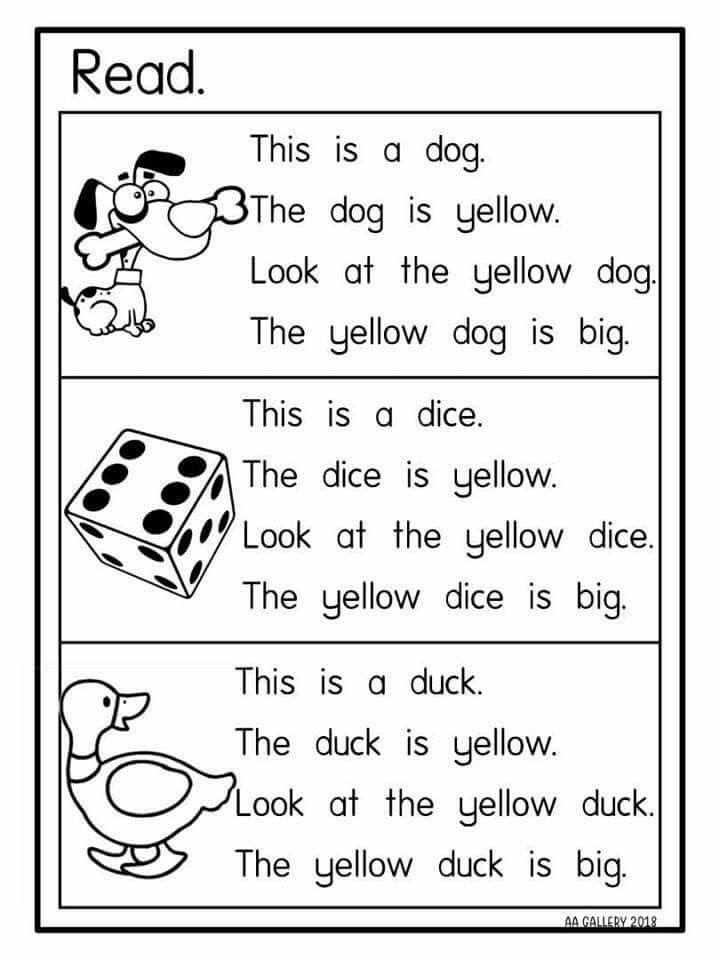

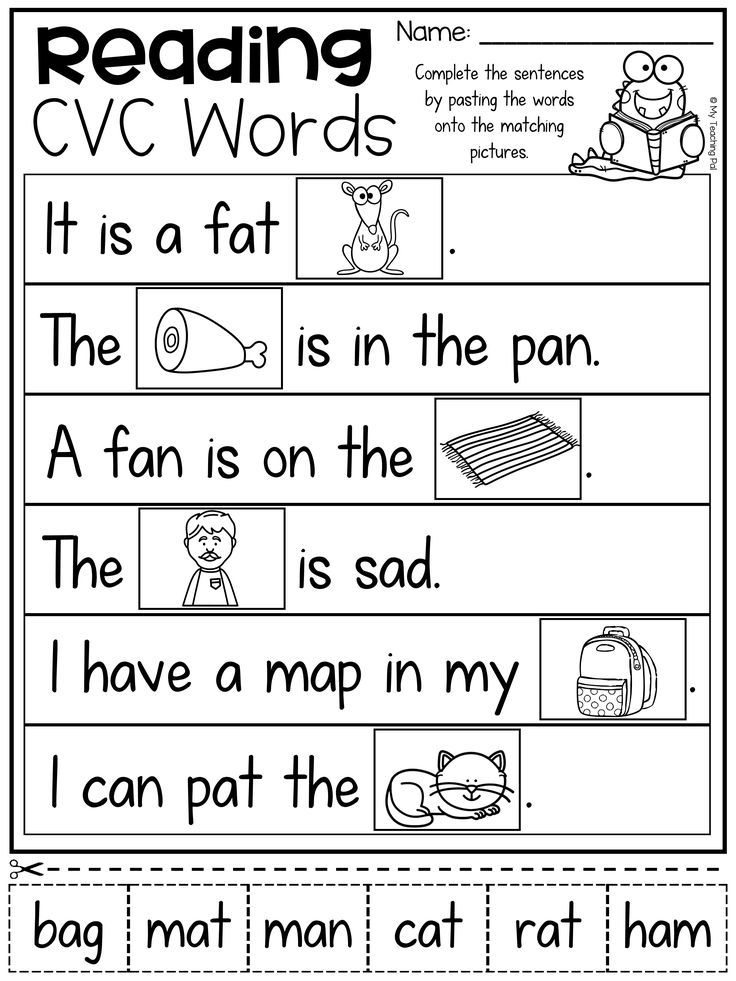

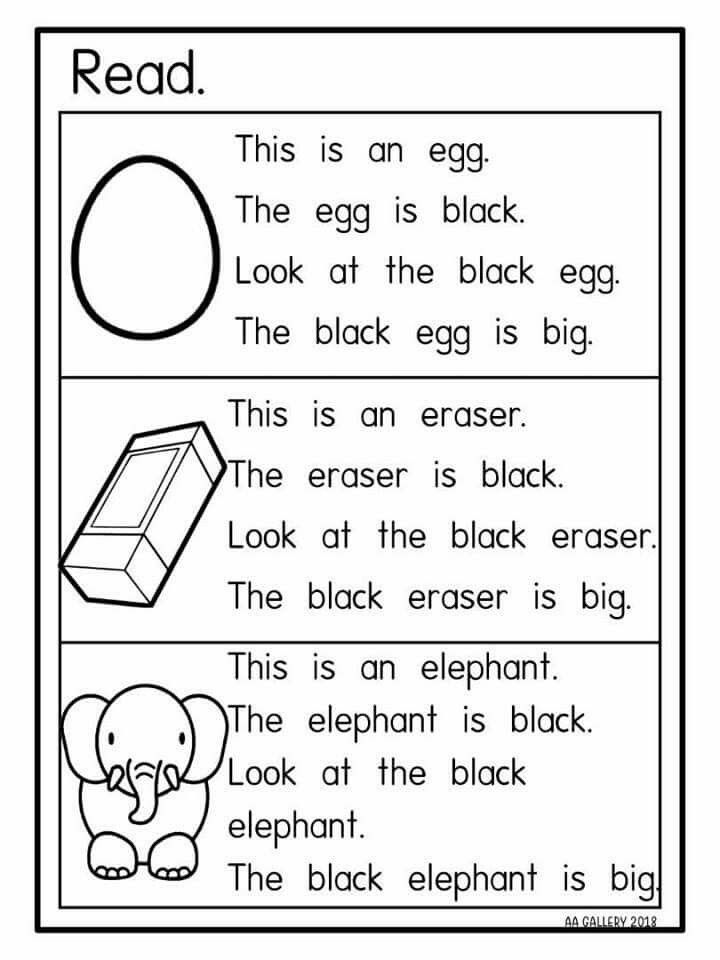

- Students read decodable phrases, sentences, and passages once for accuracy and again for fluency.

- Students spell short decodable sentences.

Have students read individually for accuracy and again for fluency while reading lists as well as sentences and passages. This need not be included in every activity.

Assess each student’s skills individually before introducing new concepts. When individual students have not mastered the objective, use your best judgment. Should the group move forward? Should the individual student receive extra practice? The answer will vary based on the composition of the group and the proportion of students in it who are struggling.

When individual students have not mastered the objective, use your best judgment. Should the group move forward? Should the individual student receive extra practice? The answer will vary based on the composition of the group and the proportion of students in it who are struggling.

Back to top

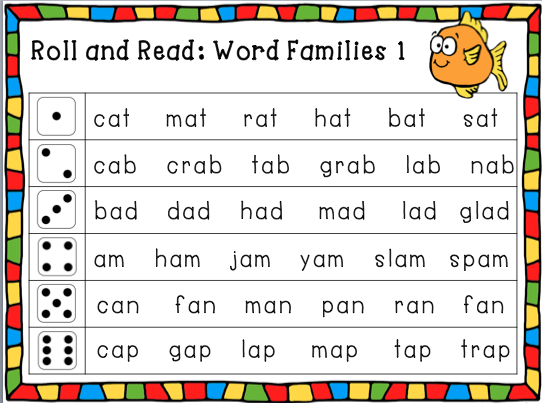

Sample beginning phonics lessons

Phonics lessons flow naturally out of phonemic awareness activities. For example,

- In phonemic awareness, ask students to segment words with the sounds short a, /m/, /p/, and /t/.

- Explain that the letter m spells the sound /m/, etc.

- Have students individually practice saying letter names in isolation.

- Have students individually practice reading letter sounds in isolation.

- Introduce three to four irregularly spelled high-frequency words to learn by sight.

- Ask students to segment words with the sounds short a, /m/, /p/, and /t/, and then arrange letter tiles to spell the segmented words.

- Demonstrate how to point to each letter and say the sound. Then blend the letters to read words (called "touch and say" or "touch and read").

- Have students individually practice sounding out three to five words, then re-read the words they sounded out previously.

- Ask individual students to read a list of words (comprised of only the sounds explicitly taught and practiced to date).

- Students read once for accuracy and again for fluency.

- When a student misreads a word, guide the student through sounding out the word. Then the student re-reads the whole group of words to the end by reading accurately.

- Lead students in a review of the irregularly spelled high-frequency words taught earlier in the lesson and from prior lessons. Learn more in this article, A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words.

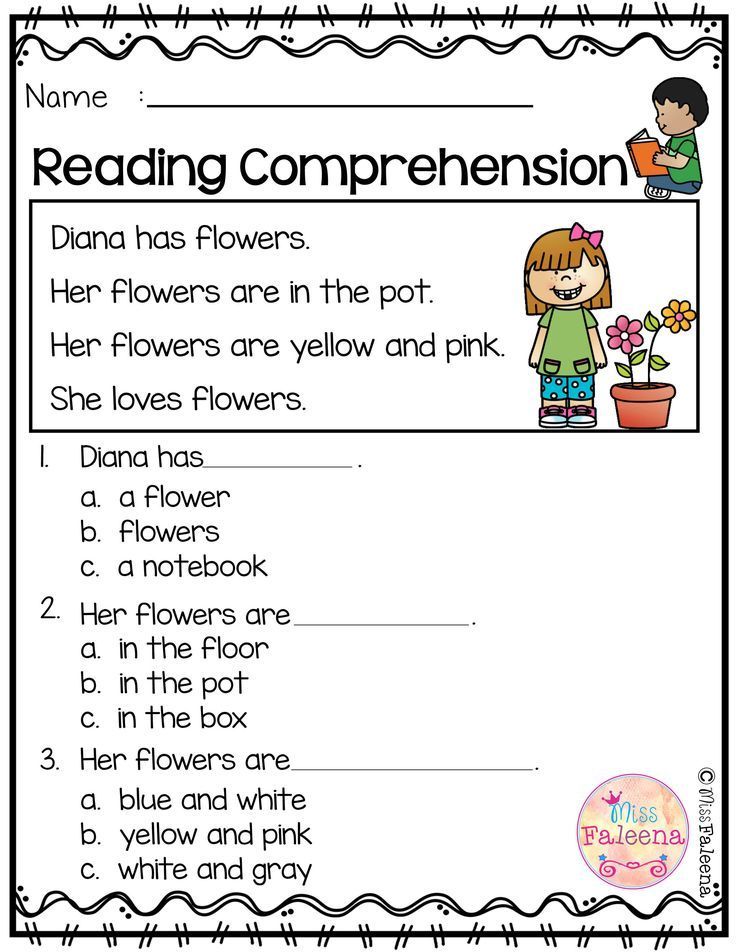

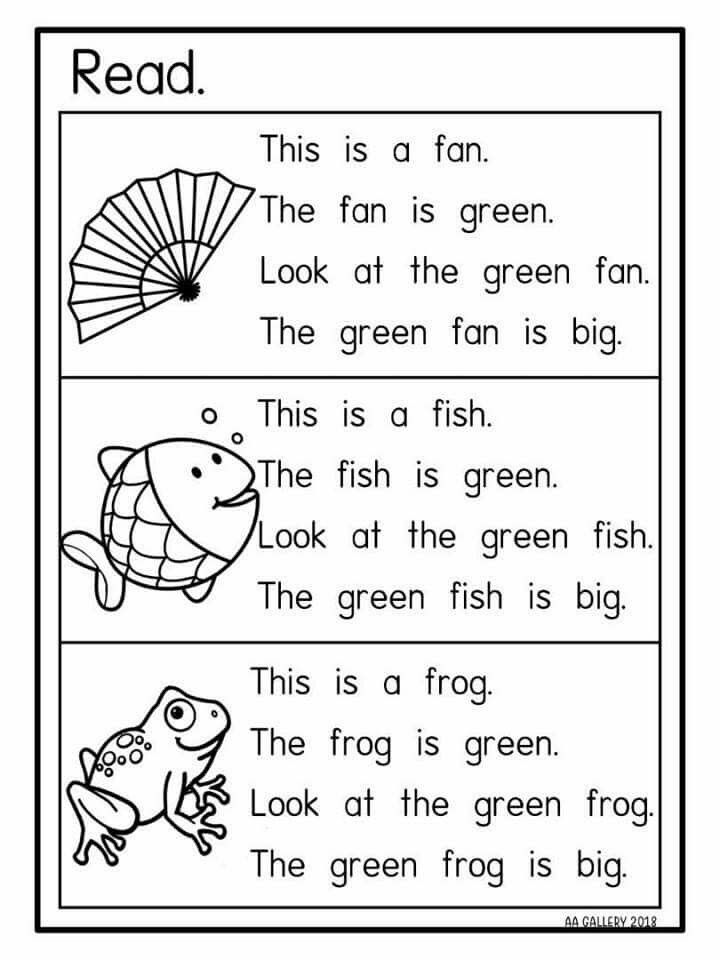

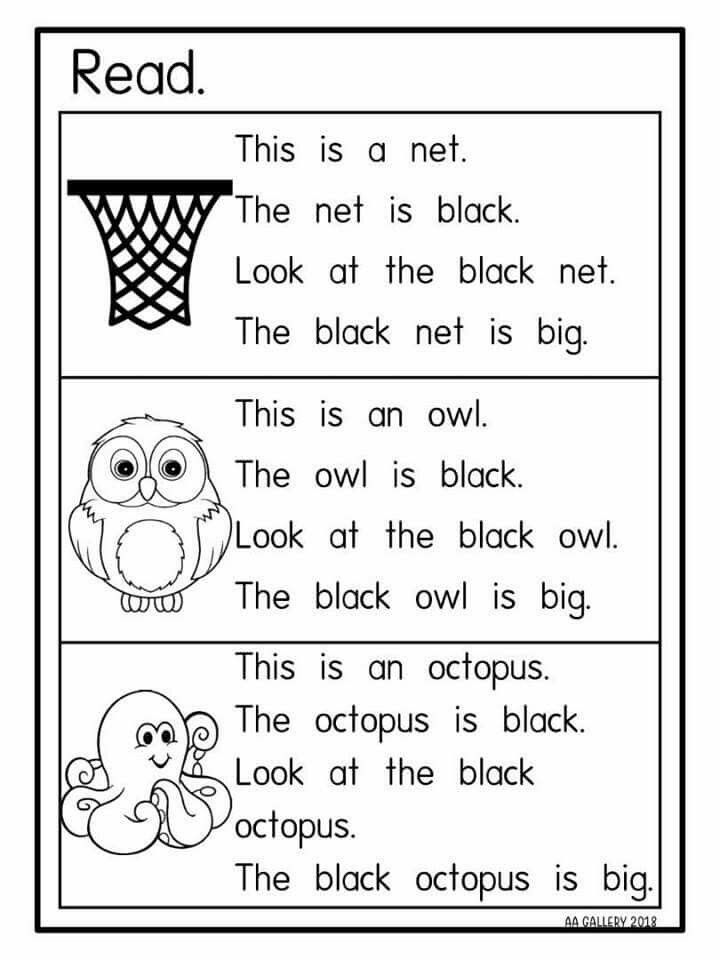

- Guide students through reading phrases, sentences, and (eventually) passages comprised of decodable words with the sounds explicitly taught and practiced to date along with some irregularly spelled high-frequency words.

- Students read once for accuracy and again for fluency.

- When a student misreads a word, guide the student through sounding out the word. Then the student re-reads the whole phrase, sentence, or portion of the passage to the end by reading accurately.

- Students spell letter sounds, decodable words, and short decodable sentences.

Beginning phonics lessons introduce only three or four new consonant sounds and only one new vowel sound in a lesson. Continue with this lesson until all students in the group are reading at 95–98% accuracy on a first attempt. Move to the next lesson, introducing another three or four consonant sounds and another new vowel sound.

Children in a general education classroom will vary widely in how easily they acquire word recognition skills. We should make use of flexible groups to meet the needs of children who can move ahead quickly in their word-reading skills, or conversely, the needs of those who require more practice.

Children who consistently perform at a high rate of mastery in their word recognition skills can focus on other valuable literacy activities such as independent reading and writing, while we are working with flexible groups who require continued phonics instruction.

Back to top

Phonics lesson routines

Include instructional routines in lesson activities. Instructional routines are repeatable routines used to practice a new skill.

For example, guide the reading group to use "touch and say" to read a list of words containing the lesson’s focus letter sounds. The steps for the activity are:

- Model "touch and say" with one word.

- Have the group use "touch and say" to read three words together.

- Have each student use "touch and say" to read five words and then re-read the list without "touch and say."

- Ask the whole group to read the same five words chorally. Use this routine daily during the phonics lesson as the activity that precedes reading whole words.

Instructional routines reduce students’ memory load. Students do not have to remember the steps in a routine while simultaneously remembering the new concept. As a result, routines provide support and stability and improve the pace of the lesson.

Moats, L. and Hall, S. (2010). LETRS Module 7: Teaching Phonics, Word Study, and the Alphabetic Principle (Second Edition). Longmont, CO: Sopris West.

Back to top

Instruction for all: the value of a multisensory approach

Teaching experience supports a multisensory instruction approach in the early grades to improve phonemic awareness, phonics, and reading comprehension skills. Multisensory instruction combines listening, speaking, reading, and a tactile or kinesthetic activity.

NOTE: Research does not yet have definitive answers about how multisensory instruction works. Literacy expert Tim Shanahan offers this perspective in his blog post, What About Tracing and Other Multisensory Teaching Approaches?.

Phonics instruction lends itself to multisensory teaching techniques, because these techniques can be used to focus children’s attention on the sequence of letters in printed words. As such, including manipulatives, gestures, and speaking and auditory cues increases students’ acquisition of word recognition skills. An added benefit is that multisensory techniques are quite motivating and engaging to many children.

Multisensory activities provide needed scaffolding to beginning and struggling readers and include visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile activities to enhance learning and memory. As students practice a learned concept, reduce the multisensory scaffolds until the student is using only the visual for reading. Employ the multisensory techniques to fix errors and then practice without the scaffold.

Examples of multisensory phonics activities:

- Dictate a word using say, touch, and spell. Students say each sound in the word and place a manipulative (e.

g., a tile with a letter or letter pattern on it, such as sh, ch, ck) to represent each sound in the word.

g., a tile with a letter or letter pattern on it, such as sh, ch, ck) to represent each sound in the word.For example, when we say fin, students move the letter tiles for f, i, and n, to spell the word, while at the same time saying and stretching the sounds orally. If we then say fish, students replace the tile with n on it with one that has an sh.

Subsequent examples of words in the chain could be wish, wig, wag, bag, brag, and so on. The activity should use only letter sounds/pattern sounds that children have been taught.

Letter tiles also should represent sounds at the phoneme level. For example, fish would be spelled with three tiles (f, i, sh), because it has three phonemes, whereas brag would be spelled with four tiles (b, r, a, g), reflecting four phonemes.

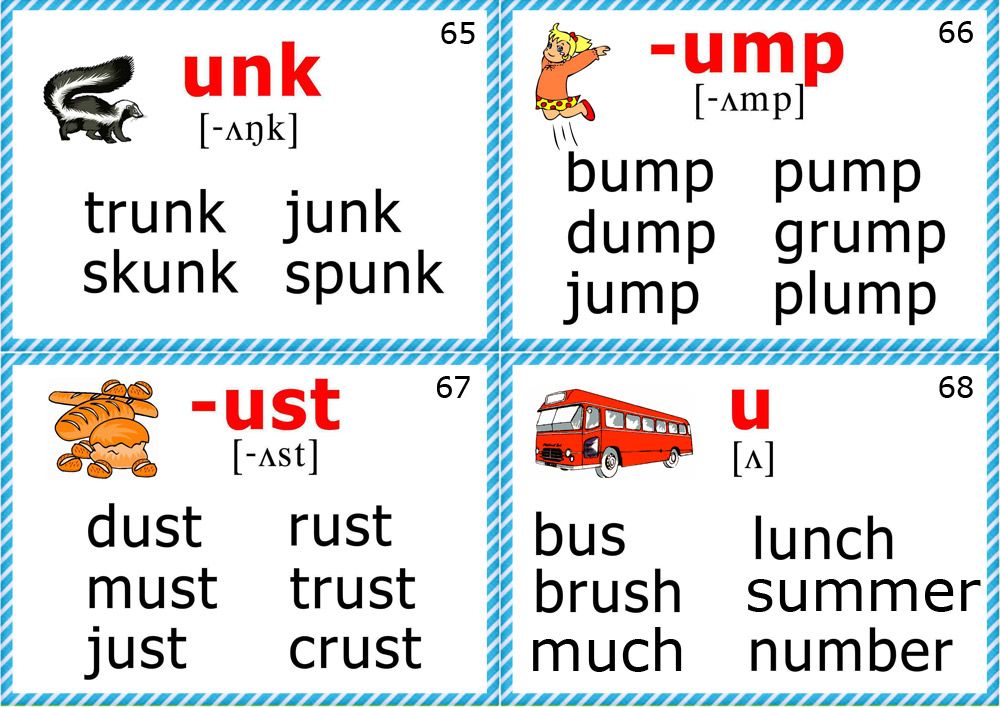

Place ending spelling patterns and beginning consonants (or consonant blends) on cards. Have students work in pairs and arrange as many words as they can on a table. Do a table walk and have each pair read the words they created. Give other teams an opportunity to create a new word.

- Organize spelling around the vowel letter. Assign a gesture to each vowel sound. Dictate a word and have students make the gesture for the vowel sound in the word.

- Assign a gesture to /sh/ and /ch/. Dictate words. Ask students to individually make the gesture associated with /sh/ or /ch/ when they hear those sounds in a word.

- Paddle pop: Teach letter clusters such as ing and ink. Write these clusters on card stock and staple to popsicle sticks. Dictate words and ask students to pop up the paddle containing the letter cluster in the word.

- Sounding out words:

- Single syllable "touch and read": Students touch each letter with a finger or pencil point and say the letter sound, then sweep left to right below the word and read the word.

- Multi syllable touch and read: Students touch each syllable with a finger or pencil point and say the syllable, then sweep left to right below the word and read the word.

Include two or three of these multisensory activities in each lesson: speaking, listening, moving, touching, reading, and writing. They fully engage the brain and make learning more memorable. These activities can be fun games or part of a daily practice routine.

Multisensory activities are the scaffold for early practice. As students become proficient in the new skill or concept, reduce and then remove the multisensory scaffolds.

Back to top

Adapting instruction for different readers

Research supports explicit phonics instruction for beginning readers and for struggling readers whose reading skills did not develop as expected. Two areas that affect reading acquisition are working memory and executive function.

Working memory refers to the memory we use to hold and manipulate information. For example, when a beginning reader sounds out a word, the student holds the letter shapes, sequence, and sounds in working memory to first sound out the word, then blend the sounds and read the word. Information held in working memory is fragile and held briefly (approximately 10 seconds) unless actively engaged.

For example, when a beginning reader sounds out a word, the student holds the letter shapes, sequence, and sounds in working memory to first sound out the word, then blend the sounds and read the word. Information held in working memory is fragile and held briefly (approximately 10 seconds) unless actively engaged.

If not attended to, the information in working memory vanishes. While this is true for everyone, some of us sustain information in working memory for seconds longer, some for less time. There are techniques that help students practice attending to information in working memory. See the articles, 10 Strategies to Enhance Students' Memories and Making It Stick: Memorable Strategies to Enhance Learning.

Executive function refers to the part of the brain that governs attention, impulse (starting and stopping), organization, reasoning, processing speed, and other higher order functions. It is the area of the brain that gets things done. It is also the last area of the brain to fully mature (mid to late 20s). Learn more: Executive Function Fact Sheet.

Learn more: Executive Function Fact Sheet.

To support students who struggle with working memory, attention, executive function, or processing speed issues, the following instructional adaptations can be helpful:

Itemized instructions

Hand out itemized instructions, and discuss what is expected in each step. Teach students how to check each step in a process off the instruction sheet to track work completed. Students with working memory and executive function weaknesses benefit greatly from learning how to use lists.

Intermittent instructions

Whenever possible, provide intermittent instructions so students do not need to remember a long list of steps. Remind the class to check any itemized instructions.

Instructional routines

Use repeated routines to practice skills and complete assignments. Repeated routines are not boring to students. They reduce the memory load on students and enable them to focus on new skills or concepts.

Repeat-safe environment

Build into the explicit instruction, practice, and assessment an opportunity to repeat instructions or information. It can be as simple as, “Anyone need me to repeat that?” or “Can I repeat the instructions for the next steps?” or “Remember. You can always ask me to repeat something.” This creates an environment in which students with attention or working memory weaknesses feel safe asking for instructions or information to be repeated.

It can be as simple as, “Anyone need me to repeat that?” or “Can I repeat the instructions for the next steps?” or “Remember. You can always ask me to repeat something.” This creates an environment in which students with attention or working memory weaknesses feel safe asking for instructions or information to be repeated.

Rehearsing

Rehearsing can include having students state something aloud before writing. It can also include briefly practicing an activity that will later be assigned as homework. By rehearsing, a procedural memory or episodic memory is created which later supports students when they attempt to work independently.

Note taking

Explicitly teach note taking and build it into classroom routines. Every student will benefit by note taking as a study skill, as a stage of writing, and as an organizational tool. There are different note taking strategies depending on the task. Explicitly teach those note-taking strategies, and build them into lesson procedures. If students learn multiple note-taking strategies, you will need to review with them which one to implement in each setting, especially for students who struggle with working memory or executive function.

If students learn multiple note-taking strategies, you will need to review with them which one to implement in each setting, especially for students who struggle with working memory or executive function.

Writing aids

- Provide a list of words pertinent to the writing assignment which have new or difficult spellings. This reduces the load on working memory by helping remove an obstacle to writing.

- Provide an itemized rubric of the things the writing assignment must contain and explicitly teach the class to review their writing for each item on the list. Students with working memory weaknesses cannot easily review their writing for multiple things (e.g., check punctuation at the same time as checking for at least three supporting details and the reasons they support the topic sentence).

Organizational and place-keeping strategies

Being organized and knowing how to break a complex task into subtasks are not always innate skills. This is especially true for students with working memory and executive function weaknesses.

We support all students by taking time to explicitly teach how to be organized: how to organize a binder, how to break a complex task into logical steps, how to allocate time on homework, etc. This requires more time at first, but as the school year progresses, less time is required. Students will benefit from this skill set through the rest of their academic careers.

Back to top

References

Barkley, R. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 65–94.

Gathercole, S. and Alloway, T. (2008). Working memory and learning: A practical guide for teachers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Giedd J., Blumenthal J., Jeffries N., Castellanos F., Liu H., Zijdenbos A., Paus T., Evans A., & Rapoport J. (1999). Brain development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal MRI study. Nature Neuroscience 2(10), 861–3.

Next: Phonics Assignments >

5 Fun And Easy Tips

Letter sounds are one of the very first things your child will encounter when they begin to explore reading.

By recognizing the phonetic sounds that alphabetic letters make, your child will take their first big step toward associating words with their individual sounds, an essential tool for, when the time is right, sounding out words.

Most new readers start from the same place — by learning their letters! And no matter where your child is on their reading journey, working with them on their letter sounds is a great way to help strengthen their fundamental skills.

Here are five fun and effective tips for working on letter sounds with your child.

5 Fun And Easy Ways To Teach Letter Sounds

1) Touch And Feel Letters

Humans are tactile creatures, and we depend on touch to tell us a lot about the world around us. This is especially true of kids when they’re learning!

Although most traditional reading curriculums focus on auditory and visual cues for letters and their sounds, touch can be helpful, too. We have five senses, after all, so we might as well take advantage of them!

We have five senses, after all, so we might as well take advantage of them!

As opposed to relying solely on how a letter looks when it’s written (and flat), adding in a physical sensory element can help your child build a stronger connection to the letter sound they’re trying to learn.

Doing this engages an extra part of their brain while they learn. Not only will they know what the letter looks and sounds like but also what it “feels” like. Associating the “feel” of a letter with its pronunciation may help them gain a better understanding of letter sounds more quickly.

There are plenty of options for exploring reading through your child’s sense of touch. The best part? Your child will get to do one of their favorite things — make a mess! Letting them get messy with letters provides a great incentive to learn.

If you’d like to try this tactile learning style, you can get started by grabbing a few blank pieces of paper. Using a thick, dark marker, write out the letters you want your child to work on.

Then, you can simply grab whatever you have around the house that is malleable enough to form into letters. PlayDoh or kinetic sand are both great options.

We recommend saying the associated letter sound as your child looks at and forms the written letter with the PlayDoh or kinetic sand. You can also encourage them to shape their material over the outlined letter on the page if they need some extra guidance.

Feel free to also brainstorm words with them that share the letter sound they’re practicing. This could help them make even more connections to the letter and its sound!

If you don’t mind a little extra clean up, shaving cream can also be a great option! Simply spread out the shaving cream on a flat surface. Trace out the letter for them in the shaving cream, then ask them to do the same while you repeat the letter sound.

2) Connect Letter Sounds To Familiar Symbols

Letters and their sounds might be unfamiliar to your child. By making a connection between letter sounds and items or symbols your child might already be familiar with, you can help bridge the gap between what they don’t know yet and what they do!

Utilizing things that your child already knows and loves may encourage them to get more engaged with learning their letter sounds. Familiar ideas will also make them feel more confident and comfortable while learning.

Familiar ideas will also make them feel more confident and comfortable while learning.

For example, if you want to start with the letter “T,” consider printing out pictures of things that start with “T” that your child loves, such as trucks and tigers. Let your child choose which pictures to use, and then help them create their very own alphabet book with those images!

Working with your child to construct their personal letter-sound alphabet — a mixture of the specific picture you want them to learn to associate with a particular letter sound — is an easy and fun craft project that will pay off in the long run.

The more personalized you can make the learning process the more fun your young learner will have!

Familiarity can also help your child beyond simply learning the letter sound: it helps them build confidence! The more your child feels like they understand and know what they’re reading, the more likely they’ll be to develop an enthusiasm for learning.

3) Repetition, Repetition, Repetition

This technique focuses on repetition, which is great for getting your child familiar with their letter sounds. By consistently repeating the same letter sounds to them, you can help your child more easily pick up on them.

By consistently repeating the same letter sounds to them, you can help your child more easily pick up on them.

A great idea might be to focus on introducing your child to one letter sound at a time. You could make a “letter of the week” jar for your child. Place an empty jar on your counter labeled with the letter sound for the week.

Every time your child points out a word they’ve heard that starts with the letter sound of the week, they earn a “ticket” or “point” in the letter sound jar (you could also use stickers on a poster if you don’t have a jar handy).

Challenge your child to gain three or four points (or more!) during the day. You’ll want the jar to be somewhere your child sees it often — maybe in the kitchen so you can prompt your learner to think of a word while you’re making dinner or washing dishes!

They don’t have to rely on only the things they hear or see in real life, especially when it comes to those trickier letter sounds (like x, q, or z). Consider using some of your daily reading time to flip through magazines or books and point out the letter sound whenever you come across it.

Emphasizing repetition this way really gives your child the chance to focus intensely on a single letter and explore the primary sound it represents!

Giving them ample amounts of time, practice, and exposure to one sound at a time may help them with their learning longevity.

4) Digital Letters In The 21st Century

Technology is a huge new factor in modern-day learning. Not only do children learn how to read and write texts, but now they also have to learn how to use a keyboard at a very young age.

While too much media time can be bad for your child, there are ways to be mindful about media consumption and incorporate media into their letter-sound learning. Especially for busy families, media can be a really useful asset to add to your parenting tool belt.

If you’re looking for a safe, personalized, and reliable place for your child to work on their reading and letter-sound skills, our online learning center has tons of playful games and exercises!

Your child can also use a simple keyboard to engage their letter-sound skills. For this activity, you can call out the sound of a letter and ask your child to hit or point to the letter it matches on a keyboard.

For this activity, you can call out the sound of a letter and ask your child to hit or point to the letter it matches on a keyboard.

This exercise is easy and versatile, as you can use any keyboard you have around — on your phone, your computer, or a device designed for kids. And your child will probably love pretending to be a grown-up just like you!

5) Bingo

Classics are classics for a reason. And Bingo is a time-tested, kid-approved game!

If you’d like to take a shot at this activity, draw or print out a Bingo sheet that has pictures of things your child is familiar with (remember tip #2!). We recommend sticking to things they see daily, like apples (for the “a” letter sound), bikes (for the “b” letter sound), and so on.

To play, call out a letter sound and instruct your child to mark off the picture that begins with the same sound. If your child has siblings or neighborhood friends, consider inviting them to play along (it makes for a great virtual game, too).

The first to make it to bingo wins!

Making Letter Sounds Fun And Functional

We hope these tips were helpful and gave you some creative ideas for how to get your child engaged with letter sounds (while having a blast along the way!).

We always want to leave you with a reminder that on the journey toward helping your child become a confident, enthusiastic reader, it may take some time to discover what learning strategies are the perfect fit for them. That’s OK!

If you ever need a little extra help or want to switch up your child’s learning routine, our learning center is always open and full of engaging and effective exercises for your emerging reader!

Author

Learning vowels tasks for preschoolers 5-6 years old in a playful way

Learning to read begins with the study of letters and sounds. The kid learns them separately, and then begins to put them into syllables, and later into words. So that acquaintance with letters does not turn out to be too difficult for the baby, you need to organize it correctly. Let's find out how to quickly learn vowel sounds with your child.

So that acquaintance with letters does not turn out to be too difficult for the baby, you need to organize it correctly. Let's find out how to quickly learn vowel sounds with your child.

How to start learning vowels

Many parents begin to teach their children the alphabet, looking at all the letters in a row, in alphabetical order. This is not the correct method. It is better to divide the letters into vowels and consonants and learn each group separately. This approach will greatly facilitate the child's task.

Start with vowels. First, explain to your child the difference between vowels and consonants. Vowels are sounds that are pronounced by the voice. They are sonorous, from which you can sing, stretch your voice.

To show your child the difference between vowels and consonants, give him a mirror and ask him to pronounce different sounds. Let him see how the position of the mouth changes during the pronunciation of vowels and consonants. When pronouncing vowels, the mouth is freely open, the tongue lies and does not move, and the air freely leaves the throat. The pronunciation of consonants involves lips, tongue, teeth.

The pronunciation of consonants involves lips, tongue, teeth.

When the child learns to distinguish between these two groups of sounds, you can move on to a more detailed study of vowels.

Method for studying vowels

There are ten vowels in the Russian alphabet - A, O, U, Y, I, Y, E, Y, Y, E. To make it easier for a child to remember them, make them from cardboard (or buy ) cards with their image.

Letters A, O, U, Y, E write in one color, for example, red. And the letters I, Yo, Yu, I, E - in a different color, for example, blue. This is necessary so that the child learns to distinguish between "hard" and "soft" vowels.

Arrange the cards in pairs: A-Z, O-E, U-Y, Y-I, E-E and show the child. Explain that paired sounds are similar to each other, only A, O, U, S, E are pronounced firmly and with a wide open mouth, and I, E, Yu, I, E have a soft sound and when they are pronounced, the lips stretch or fold into tubule.

Let the child practice pronouncing sounds in pairs by observing his facial expressions in the mirror.

Letter games

Children learn best through play. So turn the boring memorization of sounds into a fun game.

- Shuffle the cards and place them face up on the table. The task of the kid is to fold the cards with red and blue letters (A-Z, O-Yo, etc.) in pairs.

- Shuffle the cards like playing cards. Pull out one, show the child and ask what kind of letter is written on it. If he answered correctly, the card goes to him, if incorrectly, it is returned to you. To make it easier for the baby, first show the letters in pairs (A, then Z, etc.), and then at random.

- Draw or give a task a child to draw a house with ten windows - five in two rows. Write in each box of the first row the letters A, O, U, Y, E, and then ask the child to write in the boxes of the second row a pair for each letter. Then erase the letters and enter in the first row of boxes I, Yo, Yu, I, E and ask the baby to enter their pair in the second row.

Then erase all the letters again and invite the child to enter all the pairs in both rows of boxes.

Then erase all the letters again and invite the child to enter all the pairs in both rows of boxes. - name words that begin with vowels, and ask your child to name this sound (watermelon, donkey, snail, spinning top, apple, Christmas tree, blackberry, needle, exam). Then the child must come up with words that begin with each vowel sound. Invite him to name a word that starts with Y. After unsuccessful attempts to do this, explain that in Russian this letter never occurs at the beginning of a word. Name the words in which Y is in the middle (fish, lynx, skis) or at the end (teeth, mushrooms, mountains).

- Find pictures of objects with three letters in the name , one of which is the vowel (cat, onion, cheese, crayfish, beetle, etc.). Ask the child to name the object shown in the picture, determine what vowel sound is in this word and where it is located (at the beginning, middle or end of the word).

- Take a pencil and write any vowel in the air. The kid must guess what exactly you wrote.

Magnetic letters will be a good help in learning. They are bright, multi-colored, they can be attached to any metal surfaces. The kid will be happy to play with them.

Play these games every day to be effective. If the child does not want to play at the moment, do not force him. Postpone exercise for the evening. Don't do it for too long so your baby doesn't get bored. Let him look forward to the next time.

When the baby learns the vowels well, you can move on to studying consonants, composing syllables, and then to full reading. If you do not have time to teach your child to read before entering school, do not worry. First graders begin to learn to read from the first days of September. And if the child already knows letters and sounds, this process will not seem difficult to him.

Simple rules for reading in English ∣ Enguide.

ru

ru Reading in English has many features. They are quickly mastered in practice, but first you have to learn the basic rules for pronunciation of sounds. In this article, we have tried to present them clearly and simply.

Reading rules in English cannot be called simple. But you have to understand them at the very beginning of training - otherwise you will not be able to move on. Therefore, the rules for reading English for beginners (and for children) are usually set out concisely and clearly - and thanks for that. Transcriptions with examples and other supporting materials (tables, exercises) and, of course, constant practice (reading aloud and listening to audiobooks) are very helpful.

Transcription of is the transfer of sound in writing with the help of special conventional signs. In transcription, each sound has its own special sign.

True, there are features of transcription of reading in English, which are difficult for Russian-speaking students. These difficulties are due to objective differences in pronunciation in English and Russian. We simply have “the language is different” since childhood, and relearning is always difficult. Especially when you consider that often sounds in English are not pronounced the way they are written. Historically, this has happened because of the large number of dialects in which the same letters and combinations of letters were read differently. But it doesn't make it any easier for us.

These difficulties are due to objective differences in pronunciation in English and Russian. We simply have “the language is different” since childhood, and relearning is always difficult. Especially when you consider that often sounds in English are not pronounced the way they are written. Historically, this has happened because of the large number of dialects in which the same letters and combinations of letters were read differently. But it doesn't make it any easier for us.

Rules for reading transcription in English

Different English teachers solve this difficult task in different ways. For example, they use the so-called “English transcription in Russian”, that is, the recording of English words in Russian letters. Frankly, we do not support this technique. Because it does not allow you to truly learn English pronunciation correctly. One can only very roughly convey the pronunciation of English words in Russian letters. Well, there are no some English sounds in Russian, and the seemingly similar pronunciation of English and Russian sounds is still different.

Therefore, we are in favor of trying and from the very beginning, nevertheless, to learn the phonetic signs with which transcriptions are recorded. This will help to understand and remember the rules of reading English for beginners. And further English lessons will be given much easier. As for the transmission of English sounds in Russian letters, this technique is needed for transliteration (as transliteration of Russian names and surnames into English), but not for pronunciation training.

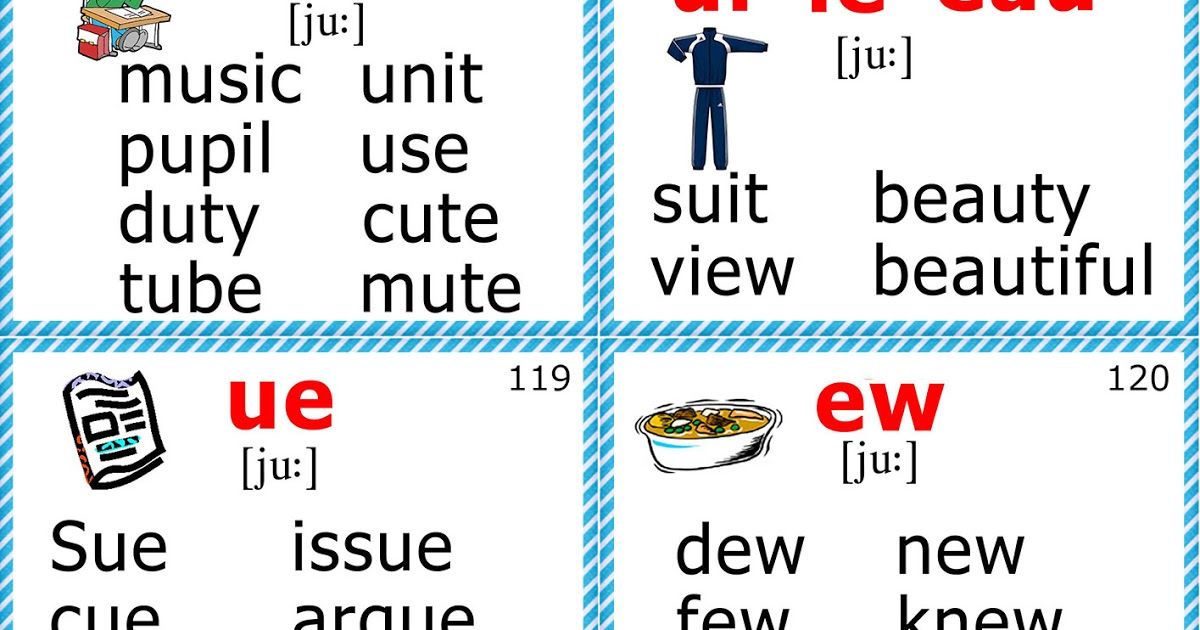

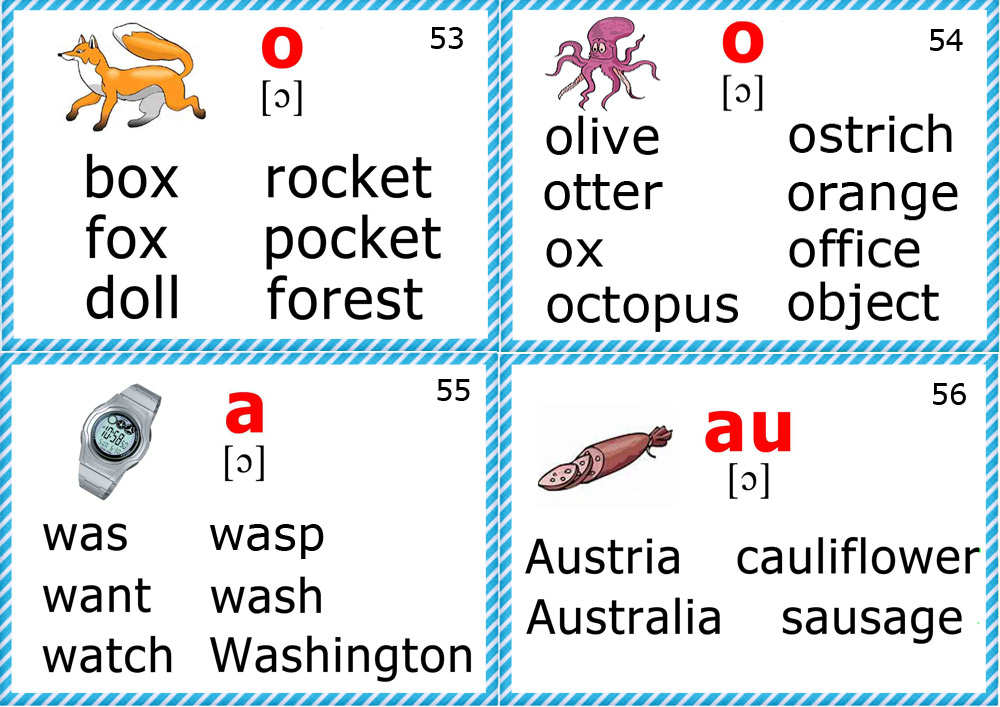

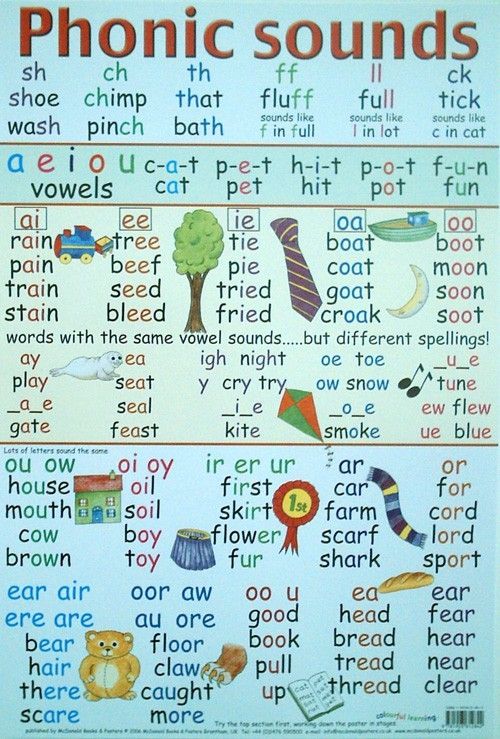

Rules for reading vowels in English

As we have already noted, letters and sounds in English often do not match. Moreover, there are much more sounds: 44 sounds for only 26 letters. Linguists even joke about this:

“We write Liverpool and we read Manchester”

So great is the difference between the written word and its pronunciation in English. Well, let's start in order. From syllables that affect the reading of vowels. Syllables in English (as in any other) are open and closed:

Syllables in English (as in any other) are open and closed:

- The open syllable ends in with the vowel . It can be in the middle of a word or be the last one in a word. For example: age, blue, bye, fly, go, etc.

- Closed syllable ends in consonant . It can also be in the middle of a word or be the last in a word. For example: bed, big, box, hungry, stand, etc.

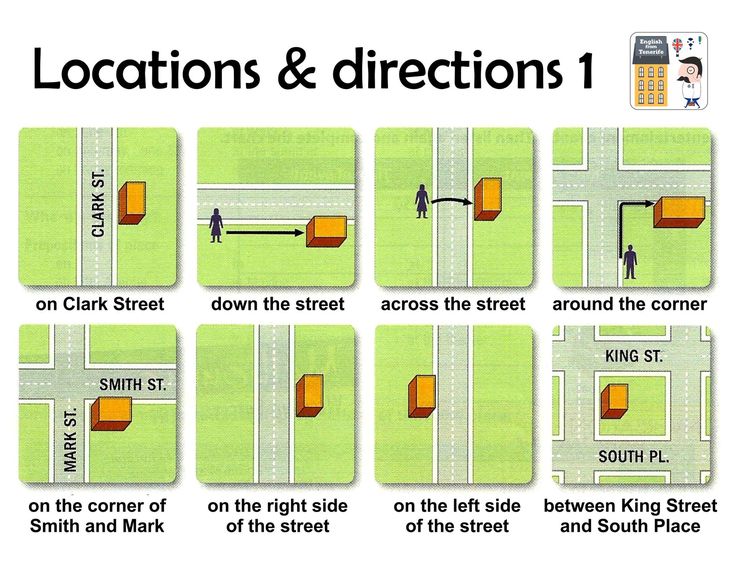

Here is a table that explains how the same letter is read differently in closed and open syllables and in different positions in a word:

A | |

| A [ei] - in open syllable | lake, make |

| A [æ] - in a closed syllable | rat, map |

| A [a:] - in a closed syllable on r | car, bar |

| A [εə] - word-final vowel + re | care, fare |

| A [ɔ:] - combinations all, au | all, tall |

O | |

| O [əu] - in an open syllable | no, home |

| O [ɒ] - in a closed stressed syllable | lot, boss |

| O [ɜ:] - in some words with "wor" | word, work |

| O [ɔ:] - in a closed syllable on r | horse, door |

| O [u:] - combined with "oo" | too, food |

| O [u] - in combination "oo" | good, look |

| O [aʊ] - in the combination "ow" in the stressed syllable | now, clown |

| O [ɔɪ] - combined with "oy" | boy, joy |

U | |

| U [yu:], [yu] - in an open syllable | blue, duty |

| U [ʌ] - in a closed syllable | butter, cup |

| U [u] - in a closed syllable | put, bull |

| U [ɜ:] - combined with "ur" | purse, hurt |

E | |

| E [i:] - in an open syllable, the combination "ee", "ea" | he, meet, leaf |

| E [e] - in a closed syllable, combination "ead" | head, bread |

| E [ɜ:] - in combinations "er", "ear" | her, pearl |

| E [ɪə] - in combinations "ear" | near, dear |

I | |

| i [aɪ] - in an open syllable | nice, fine |

| i [aɪ] - combined with "igh" | high, night |

| i [ɪ] - in a closed syllable | big, in |

| i [ɜ:] - combined with "ir" | bird, girl |

| i [aɪə] - in combination "ire" | hire, tired |

Y | |

| Y [aɪ] - at the end of a word under stress | my, cry |

| Y [ɪ] - at the end of a word without stress | happy, family |

| Y [j] - at the beginning of a word | yes, yellow |

Rules for reading consonants in English

Consonants in English are less difficult than vowels. Only some of them (C, S, T, X and G) are read differently depending on the position in the word and neighboring sounds. And for clarity - again the table:

Only some of them (C, S, T, X and G) are read differently depending on the position in the word and neighboring sounds. And for clarity - again the table:

C | |

| C [s] - before i, e, y | place, cinema |

| C [tʃ] - in combinations ch, tch | children, catch |

| C [k] - otherwise | cat, picnic |

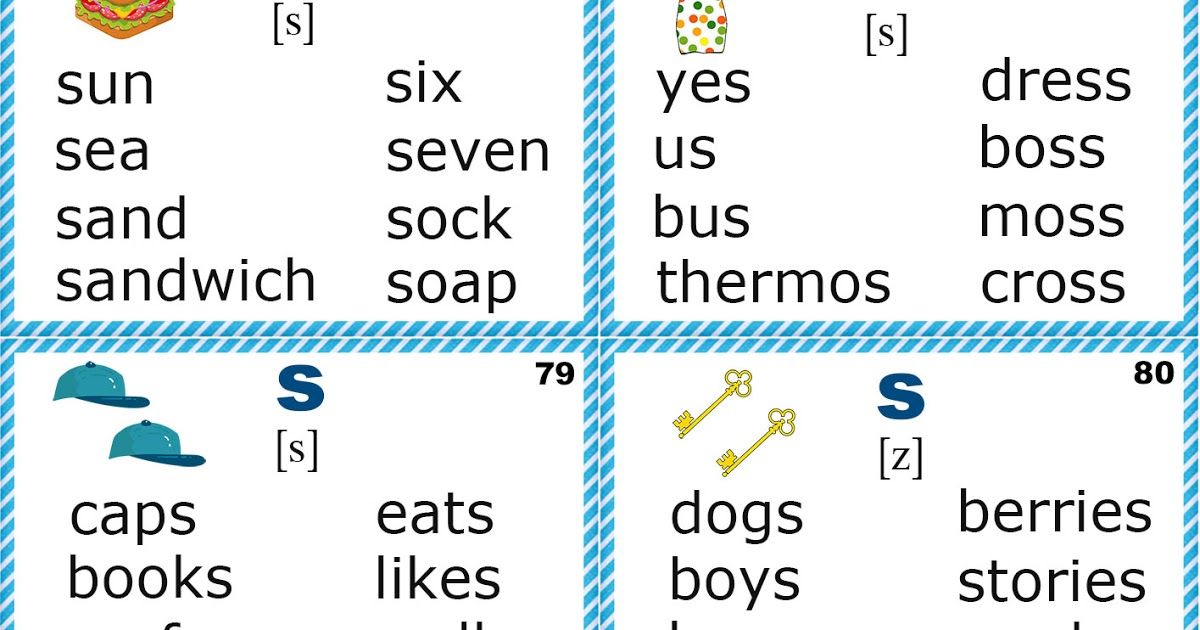

S | |

| S [z] - at the end of words after vowels and voiced consonants | places, dogs |

| S [ʃ] - combined with sh | she, show |

| S [s] - otherwise | sport, dress |

T | |

| T [t] - except combinations th | tell, time |

| T [ð] - combined th | the brother |

| T [θ] - combined th | think, fifth |

X | |

| X [ks] — at the end of words, before a consonant, before an unstressed vowel | box, fix, fox, next, six, text |

| X [gz] - before stressed vowel | exam, example, exact |

G | |

| G [dʒ] - before e, i, y | page, energy |

| G [ŋ] - combined with ng at the end of the word | song, interesting |

| G [g] - otherwise | go big |

How are letter combinations read in English?

So, after vowels and consonants, we got to letter combinations. Now we will talk about the rules for reading syllables, not individual letters. And rightly so - because in words the letters are just combined, so we rarely have to read individual sounds. And in syllables, sounds influence each other, so the following table contains the basic rules for reading syllables and combinations of consonants:

Now we will talk about the rules for reading syllables, not individual letters. And rightly so - because in words the letters are just combined, so we rarely have to read individual sounds. And in syllables, sounds influence each other, so the following table contains the basic rules for reading syllables and combinations of consonants:

| oo | [ʊ] | look, book, cook, good, foot | [lʊk] [bʊk] [kʊk] [ɡʊd] [fʊt] |

| [uː] | pool, school, Zoo, too | [puːl] [skuːl] [zuː] [tuː] | |

| ee | [iː] | see, bee, tree, three, meet | [ˈsiː] [biː] [triː] [θriː] [miːt] |

| ea Exceptions: | [iː] | tea, meat, eat, read, speak | [tiː] [miːt] [iːt] [riːd] [spiːk] |

| [e] | bread, head, breakfast, healthy | [bred] [hed] [ˈbrekfəst] [ˈhelθi] | |

| to | [eɪ] | away, play, say, may | [əˈweɪ] [pleɪ] [ˈseɪ] [meɪ] |

| ey | grey, they | [ɡreɪ] [ˈðeɪ] | |

| nk | [ŋk] | ink, thank, monkey, sink, bank | |

| ph | [f] | telephone, phonetics, phrase | |

| sh | [ʃ] | she, bush, short, dish, fish, sheep, shook | |

| tch | [tʃ] | catch, kitchen, watch, switch, stretch | |

| th | [ð] | at the beginning of service words; between vowels: these, that, there, mother, they, with, them, then | |

| [θ] | in combination th at the beginning and at the end of significant words: thick, thin, thanks, three, think, throw, fifth, tooth | | |

| wh | [w] | what, why, when, while, white, where | |

| w+o | [h] | who, whom, whose, whole, wholly | |

| wr | [r] | write, wrong, wrist, wrap, wrest, wrap | |

Living and other reading rules in English

All students have different language and listening abilities. If reading rules in English are difficult, use one of the tricks:

If reading rules in English are difficult, use one of the tricks:

- Live English Reading Rules . This is a fairly well-known technique for teaching reading and pronunciation in English. It is designed mainly for children, and the rules of English reading are presented as accessible as possible. Memorization is facilitated by funny verses and tongue twisters. It makes sense to try to interest the child in English from the very beginning of the study.

- Applications for learning English . We recently discussed a range of programs and apps that help you learn a foreign language. In most of them, you can not only read, but also listen to new words. The same function is available in online translators - use it more often.

- Exercises on reading rules . There are many of them, but they all come down to training the skill to distinguish between different sounds. For example:

Given a list of words ( what, who, wrestling, when, why, whose, wrong, where, whom, write, white, which, whole, wrangler ).