Letter a learning activities

15 SIMPLE Letter A Activities

Are you looking for activities to practice the letter A?

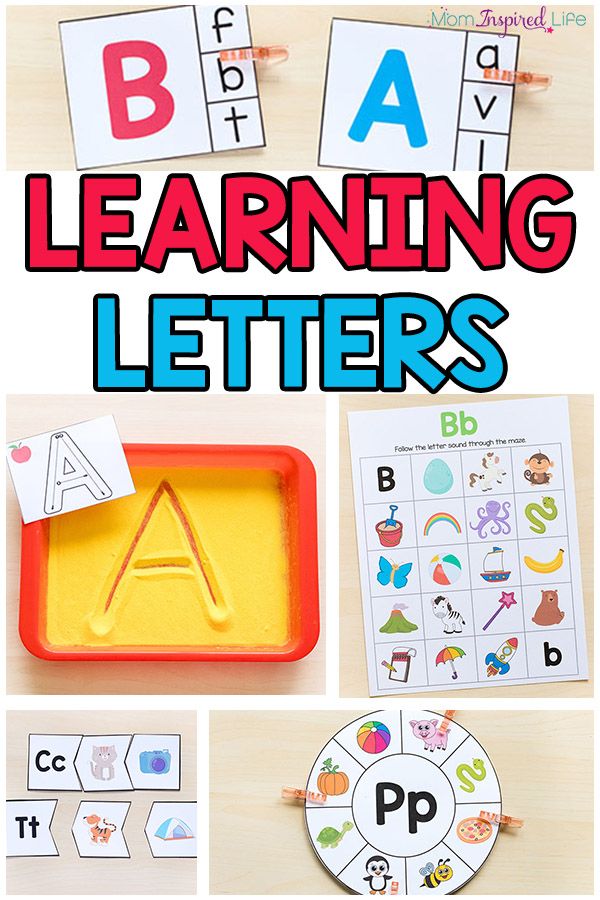

I have 15 engaging activities that will help your child learn about the letter A! These activities are perfect to use in the classroom, or you can do them right at home! These play-based learning strategies will have your kids hooked on each activity!

Giving your student or child the opportunity to learn one letter at a time will help them remember each letter. By doing these fun activities, your child will create memories of each letter!

Let’s dive into my exciting activities to learn the letter A!

Activity #1: Letter Collages

Letter collages are a great way to practice letter recognition! Focusing on one specific letter and creating something special will help them recognize and remember the letter.

For the letter A, we did apple printing!

Apple printing is fun for kids to experiment with since it’s a different way to create art! I picked apple printing since apples start with the letter A.

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- cardstock paper

- apples

- washable paint (red, green, and yellow)

- art tray

- knife

View Amazons Price

2. Set-up: Cut an apple in half using a knife (make sure you are the one doing this part). Make sure both sides of the apple are smooth. Lastly, print and cut out the letters and paste them to cardstock paper.

3. Activity: Let your little one dip the apples into the washable paint on an art tray. They will make prints with the apples on the letter A.

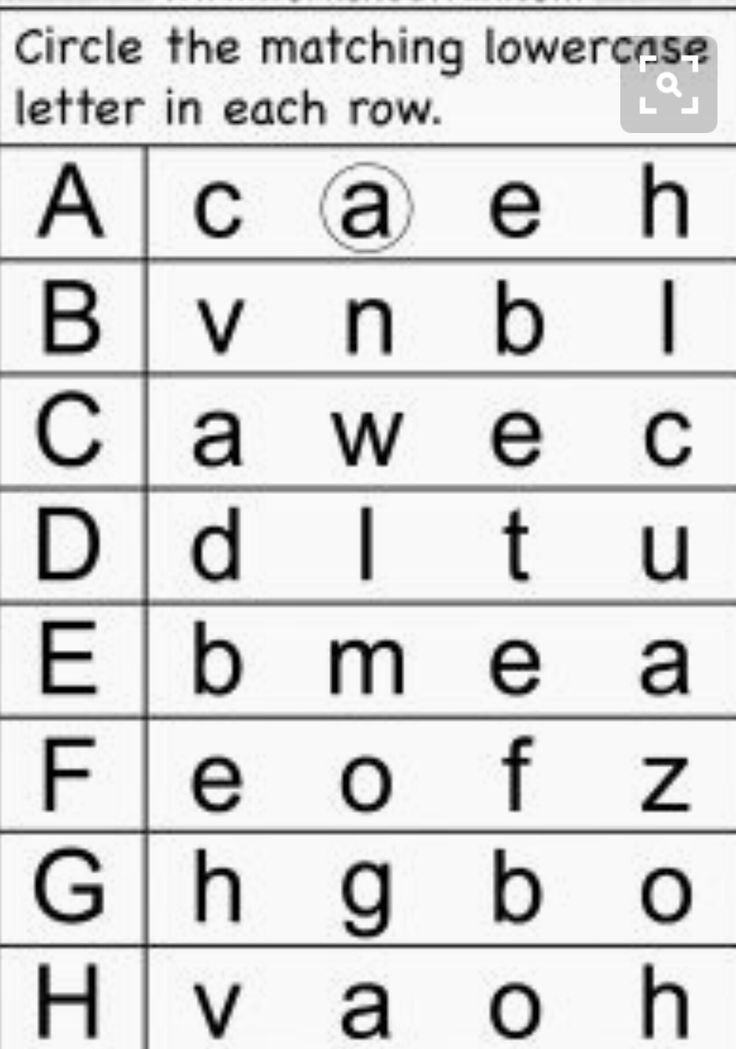

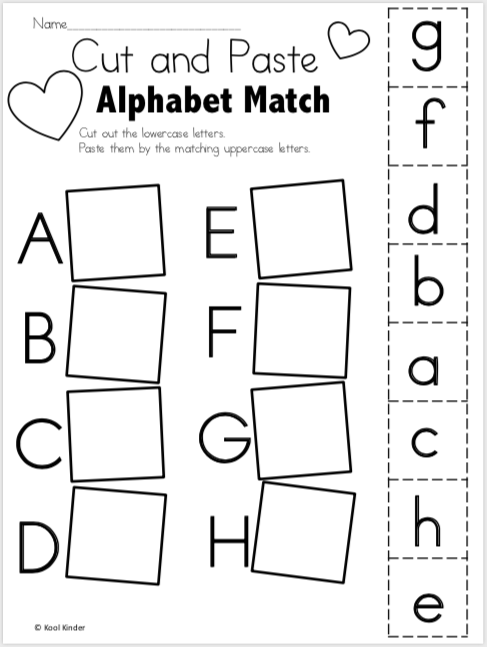

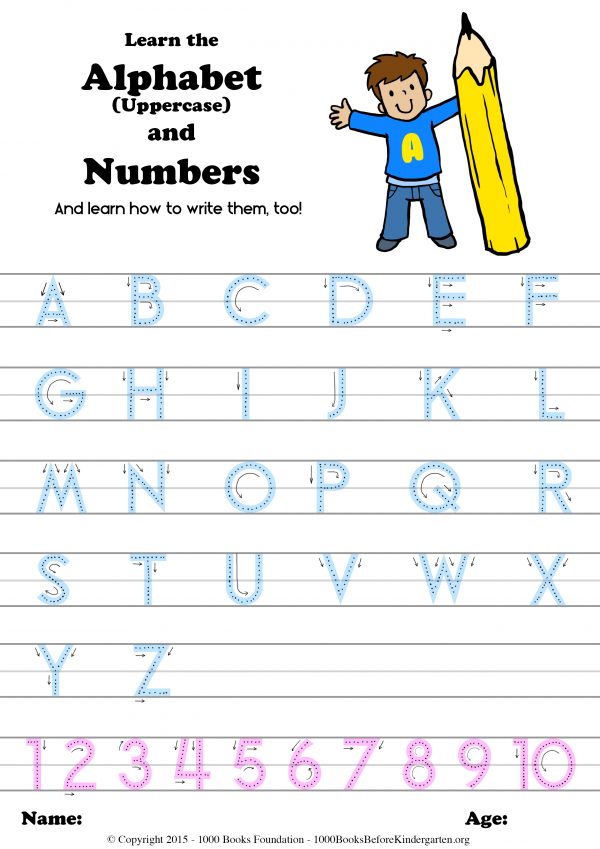

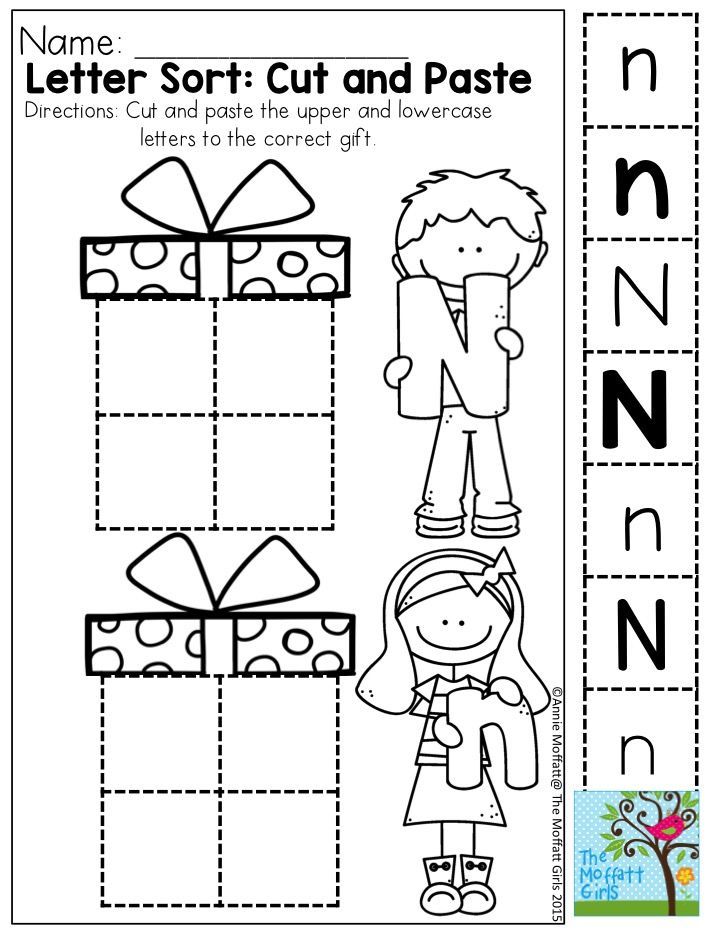

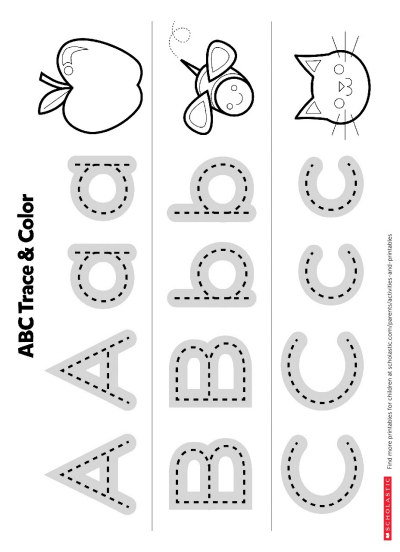

Focusing on both the upper and lower case letters is crucial for children to know before entering kindergarten. They will be asked about both on the kindergarten readiness assessment.

RELATED: 30 Kindergarten Activities For Kids

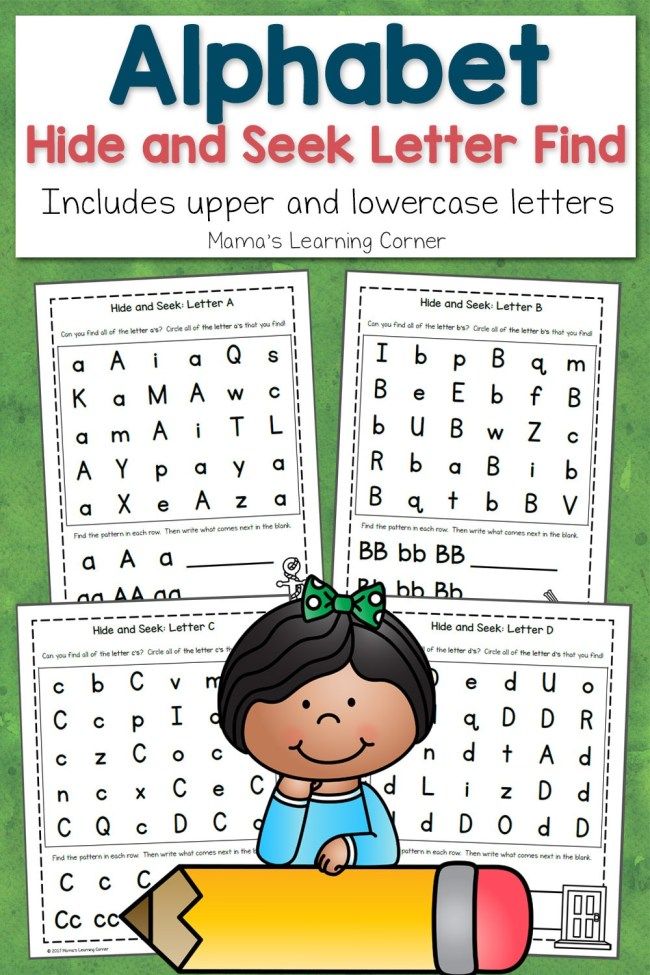

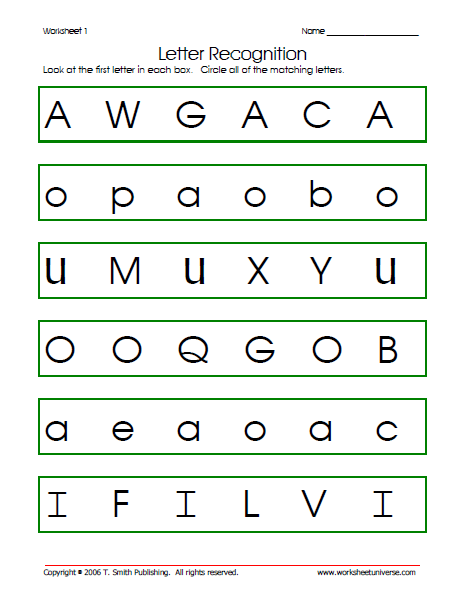

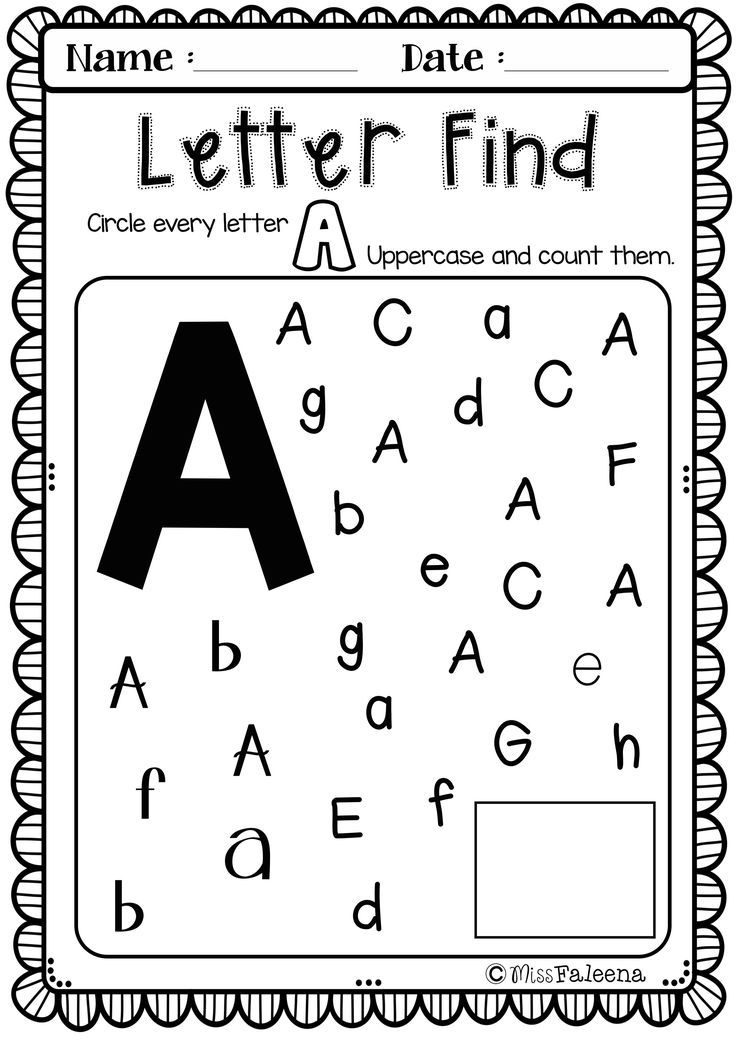

Activity #2: Do-A-Dot Letter Search

Who doesn’t love mess-free art?! Do-A-Dot paint markers pretty mess-free as long as your little one doesn’t wipe them all over their hand, wishful thinking, right?!

This printable is a perfect way to let you know if your little one can differentiate letters!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

Materials you need:

- FREE Do-A-Dot Letters Printables

- Do-A-Dot markers

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: Print off the pages and get the paint markers ready!

3. Activity: Your little ones with use the paint markers to place a dot on only the letter A. See if they can find all the letter A’s on their own. To extend the learning, have them count how many letter A’s they found on the sheets.

RELATED: Teaching Resources

Activity #3: Letter A Search and Match

My kids are OBSESSED with search and match activities. Honestly, whenever I create a game using this same set-up, even though they have done it so many times, it’s always their favorite.

It’s effortless to set up and takes only a few minutes to prep!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- colored cardstock paper

- sticky notes

- markers

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: Draw an upper and lower case letter on cardstock paper. Tape it up on the wall! On post-it’s, write a bunch of upper and lower case letters, then hide them around your house or classroom.

Set-up: Draw an upper and lower case letter on cardstock paper. Tape it up on the wall! On post-it’s, write a bunch of upper and lower case letters, then hide them around your house or classroom.

3. Activity: Have your kids search for the post-it notes! Once they find one, have them place it on the matching letter they see on the paper. Once all of them are found, hide them again and repeat!

I wouldn’t be surprised if you do this activity several times through!

RELATED: Alphabet Activities for Preschoolers

Activity #4: Alligator Craft and Feed

A is for alligator! Isn’t this the cutest alligator you ever saw? This was a major hit with both my kids! I had to make several more because they even made up a game with the alligator clothespins!

How cute are these colored clothespins? I use them for so many different activities!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- colored clothespins

- letter A toys

- pipe cleaners

- cardstock

- hot glue and gun

- googly eyes

- white paint stick

- Q-tips

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: Cut a small strip of green cardstock paper and two small strips of white paper. Hot glue the small strip of green cardstock on top of the clothespin. The white strips should be in a zig-zag pattern to look like teeth. Glue those onto the sides of the clothespin. Then glue the googly eyes on top! I added some red paint on to be the tongue.

Set-up: Cut a small strip of green cardstock paper and two small strips of white paper. Hot glue the small strip of green cardstock on top of the clothespin. The white strips should be in a zig-zag pattern to look like teeth. Glue those onto the sides of the clothespin. Then glue the googly eyes on top! I added some red paint on to be the tongue.

3. Activity: Use the alligator craft to do an engaging activity to focus on the letter A! The alligator only wants to eat the letter A. Use letter toys and have the kids pick out a letter. They will use the alligator to eat only the letter A’s!

Activity #5: Letter Fill

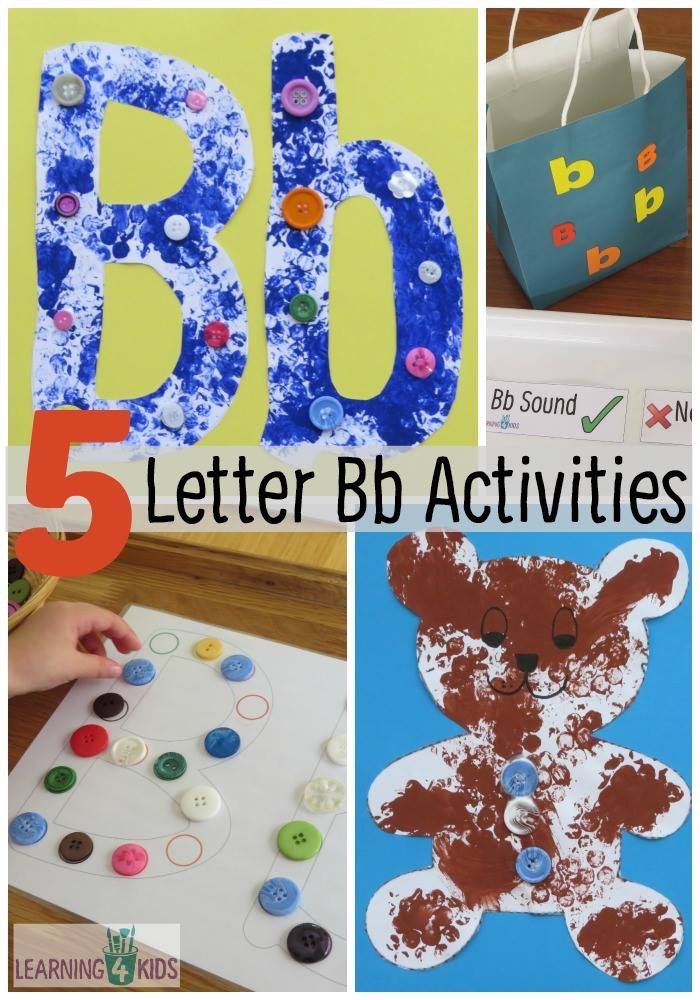

Letter fill activities are quickly becoming one of my favorite activities to do with the kids.

They love using loose parts to be able to make the letters look beautiful! I like this process too because there are so many possibilities with the objects you can use!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- cardboard

- Sharpie

- glue

- pom-poms

- colored rice

- pipe cleaners

- stickers

View Amazon's Price

There could be other materials that you could use, but the list would go on forever!

2. Set-up: On a piece of cardboard paper, draw a bubble letter A with a sharpie. Either you or your little one can squirt glue on the entire letter. This is one circumstance where they can add a bunch of glue and not have a disaster :).

3. Activity: Your child will put the object that you chose all over the letter! So if you chose pom-poms, for example, have them try to cover all the glue lines up with the pom-poms. To extend the learning, count how many items that were placed inside the letter.

To extend the learning, count how many items that were placed inside the letter.

Activity #6: Salt Painting

Have you ever tried salt painting? It always turns out SO pretty!

Kids love watching the paint flow throughout the salt. It’s a relaxing way to paint, and the kids will love trying a new way to create art.

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- cardboard

- pencil

- glue

- salt

- watercolors

- paintbrush

- art tray

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: On your piece of cardboard, draw the letter A with a pencil. Then, outline the letter in glue. Make sure to place the cardboard on an art tray for the next part! Shake a whole bunch of salt all over the glue the dump the access in the trash.

*You have to let the glue dry before you start painting, or else it will be REALLY messy!*

3. Activity: Have your little ones use the watercolor paints to paint the salt! It looks terrific, too, when you mix different colors throughout the letter.

Activity: Have your little ones use the watercolor paints to paint the salt! It looks terrific, too, when you mix different colors throughout the letter.

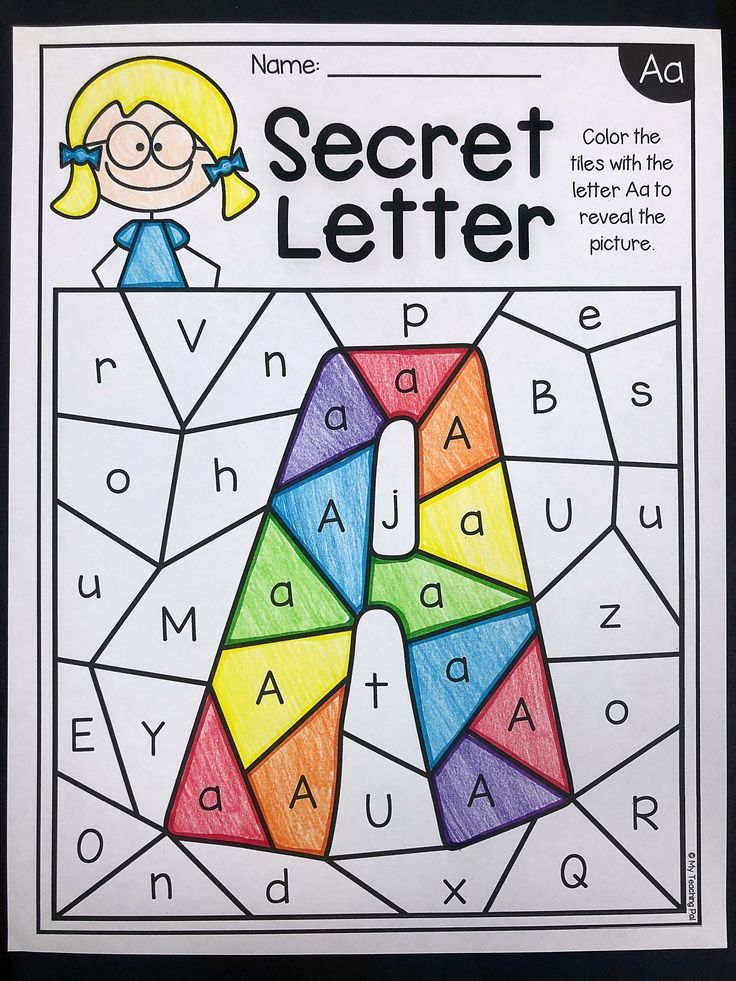

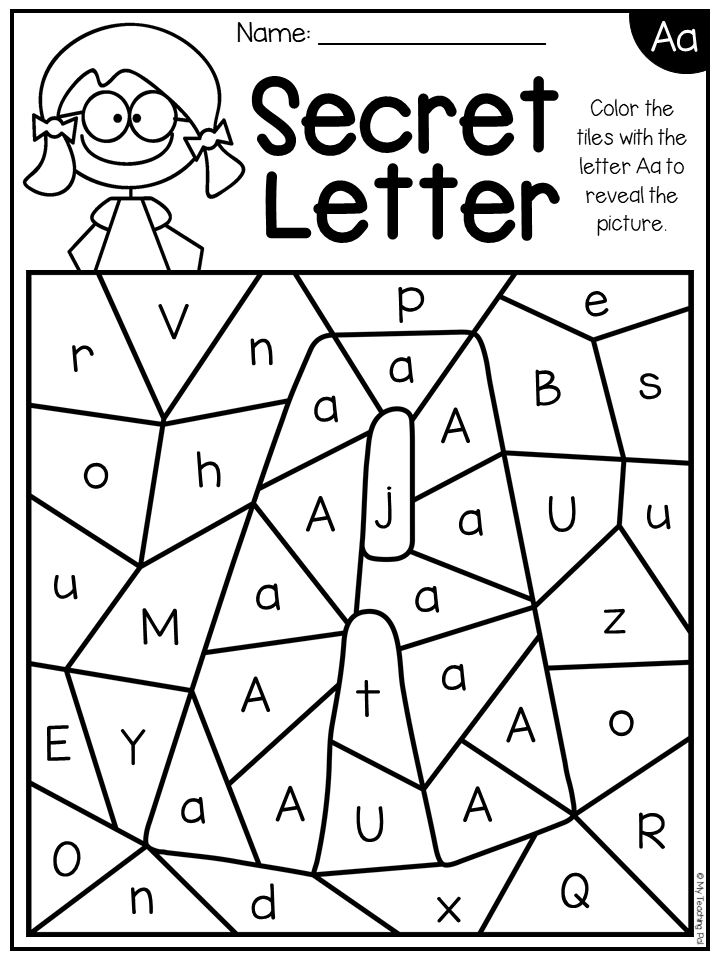

Activity #7: Secret Letters

Kids love the element of surprise! Who doesn’t? I still do!

Secret letter activities are really engaging for kids because they can’t see the letters on the paper, so when they paint over the piece of paper, they will see letters magically pop up!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- white cardstock paper

- watercolors

- paintbrush

- white crayon

- art tray

2. Set-up: On a white piece of cardstock, use a white crayon to write the letter A all over the paper. You can do upper and lower case or just focus on one.

3. Activity: Your kiddo will use watercolors to paint all over the paper. They will see the letters start to pop up! If you mixed upper and lower case letters, make sure to ask them which kind they found.

They will see the letters start to pop up! If you mixed upper and lower case letters, make sure to ask them which kind they found.

When you are all done, ask them how many they found! Also, you can talk about the colors that they used for color recognition.

RELATED: How to Teach your Toddler Colors

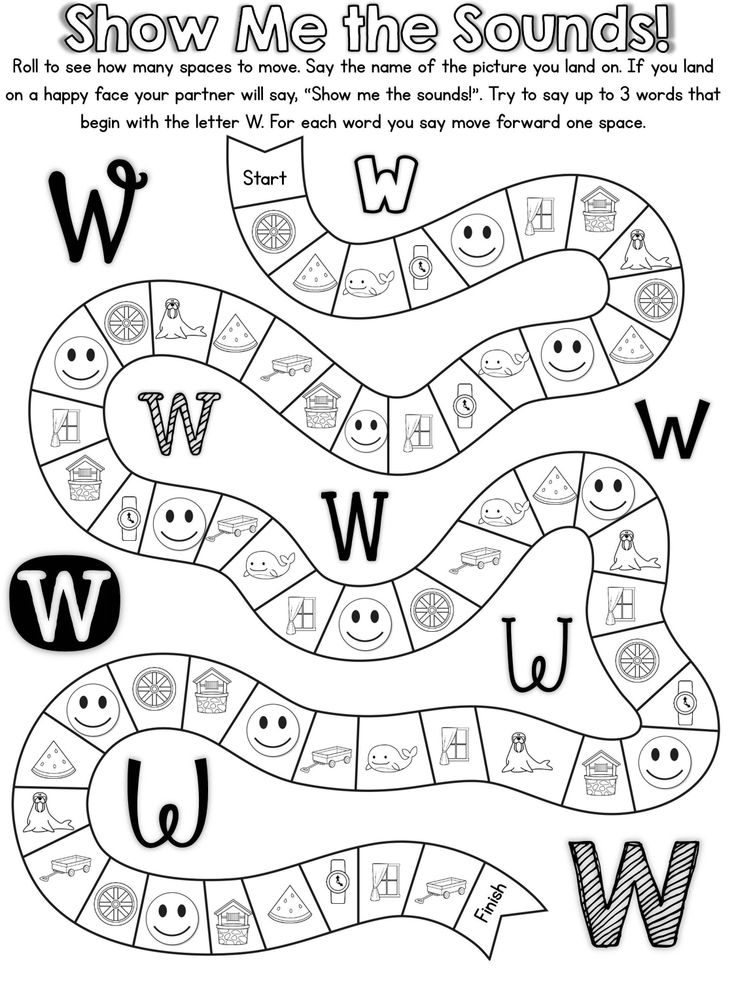

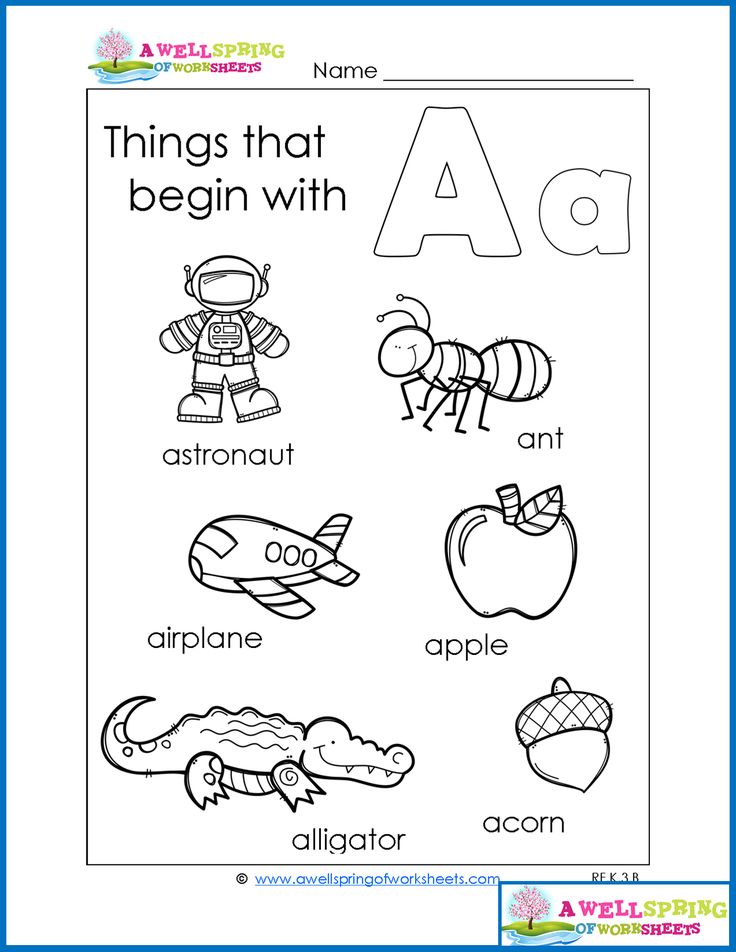

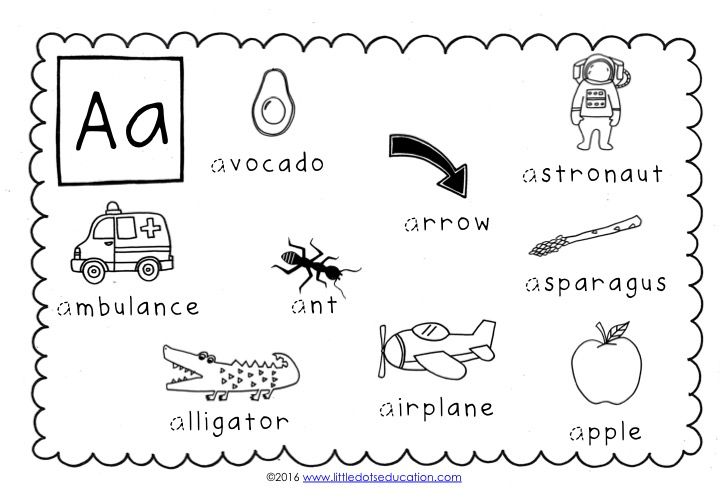

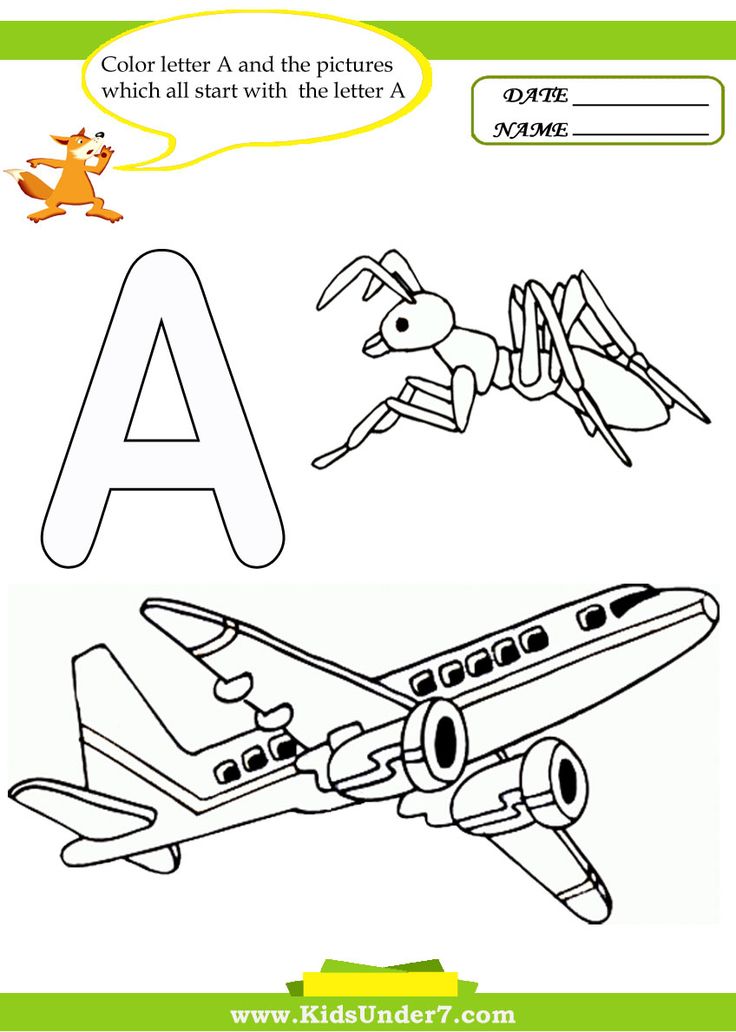

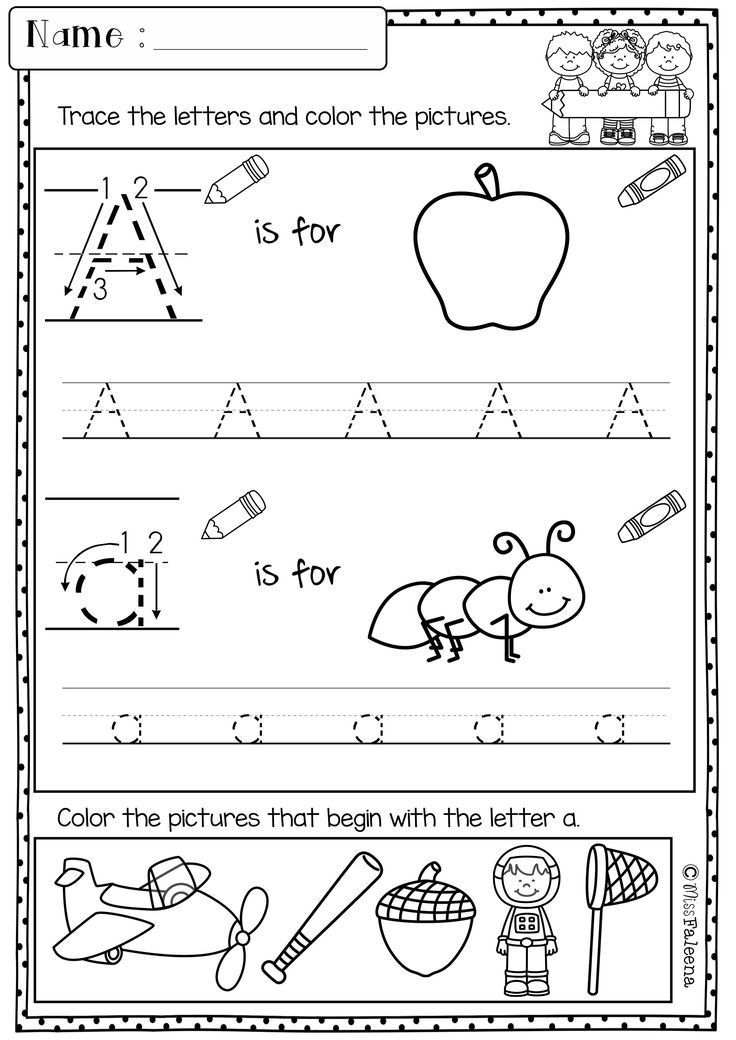

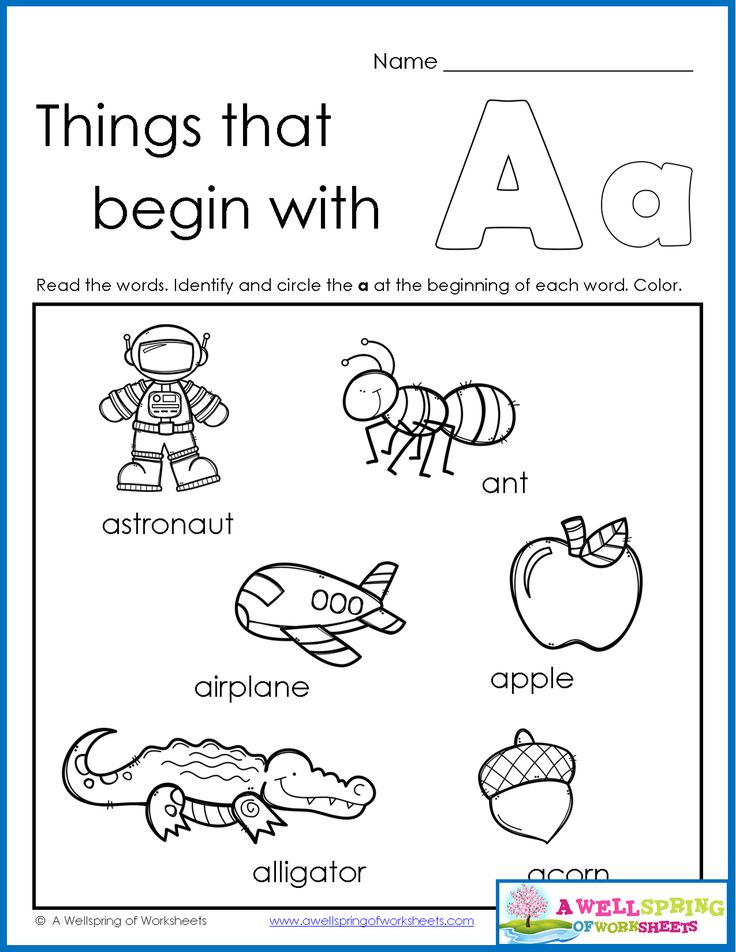

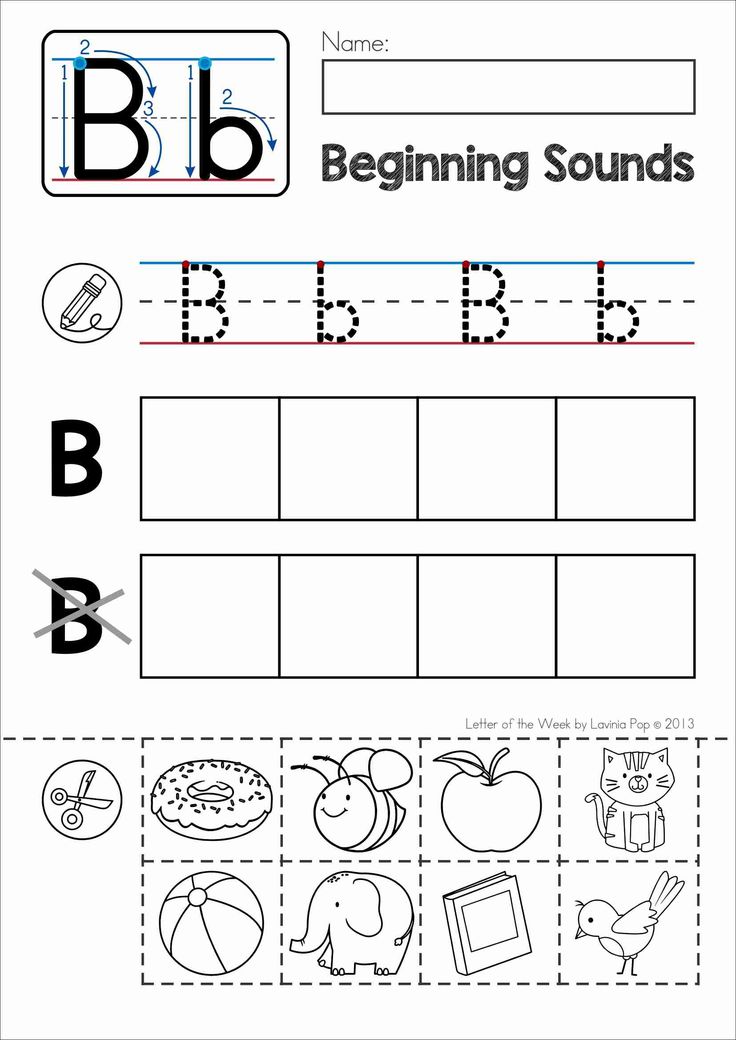

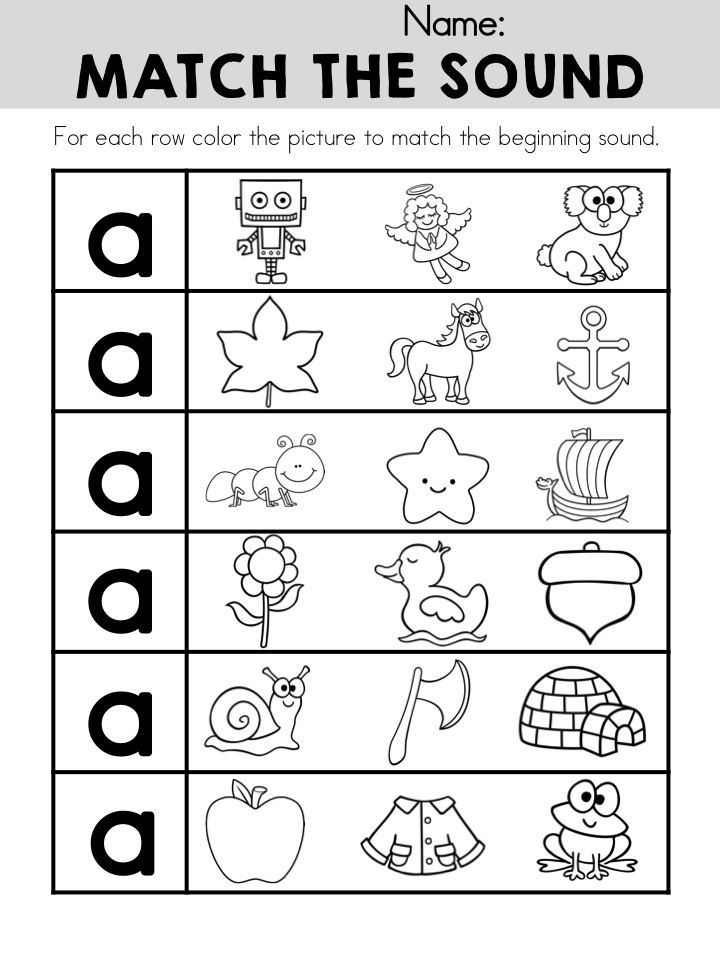

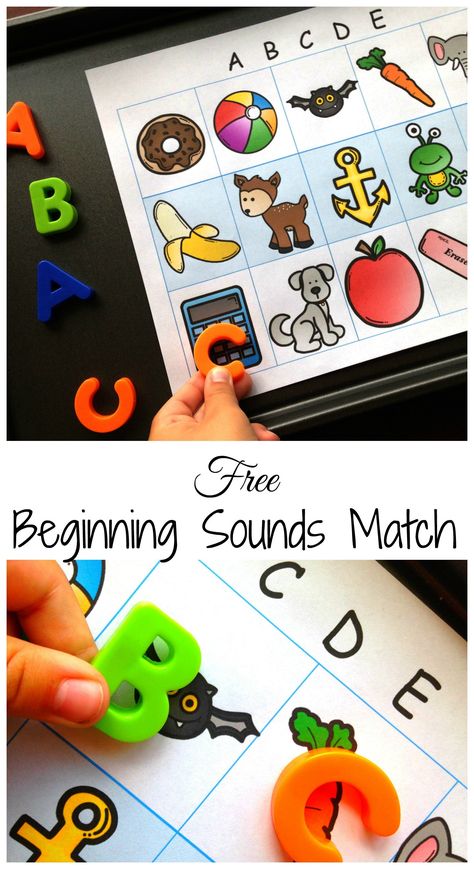

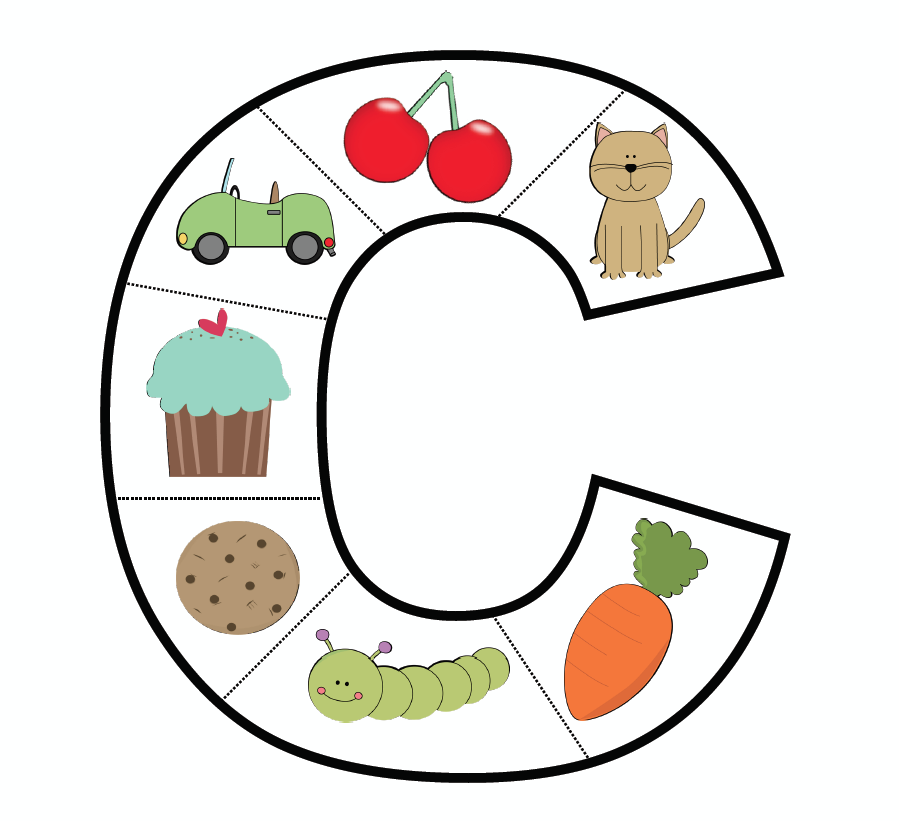

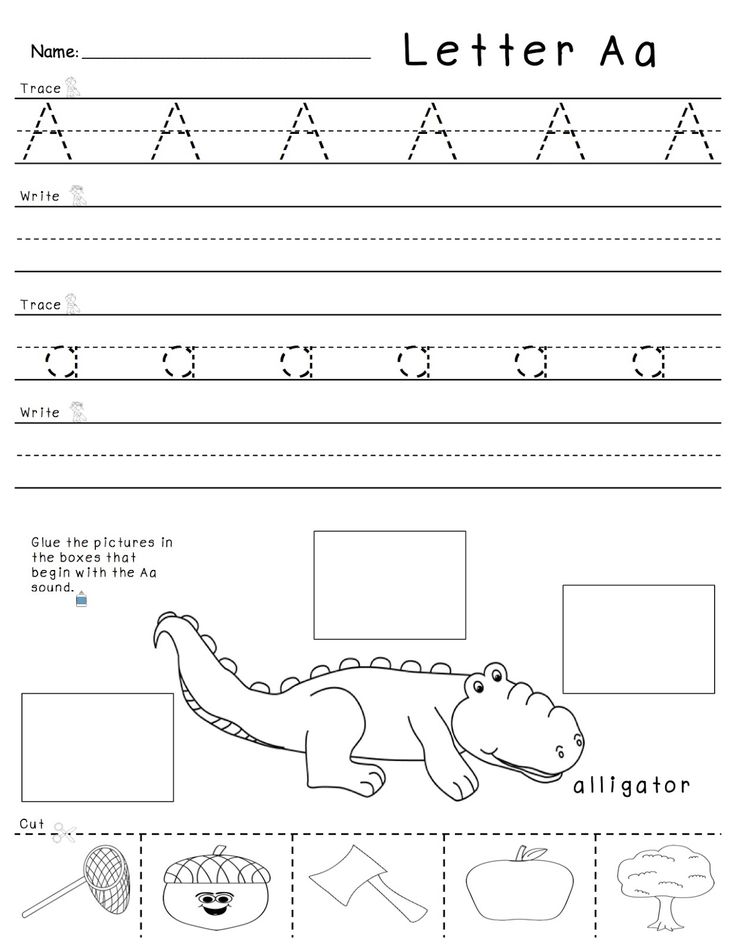

Activity #8: Beginning Sounds

Talking about animals or objects that start with the letter A will help bring the letter to life for your little one.

These beginning letter worksheets are a perfect way to show your little one some fun things that start with the letter A!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- CLICK HERE FOR My beginning sounds letter A worksheet (I have letters A-Z available!)

- crayons

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: Print off the worksheet and grab your crayons!

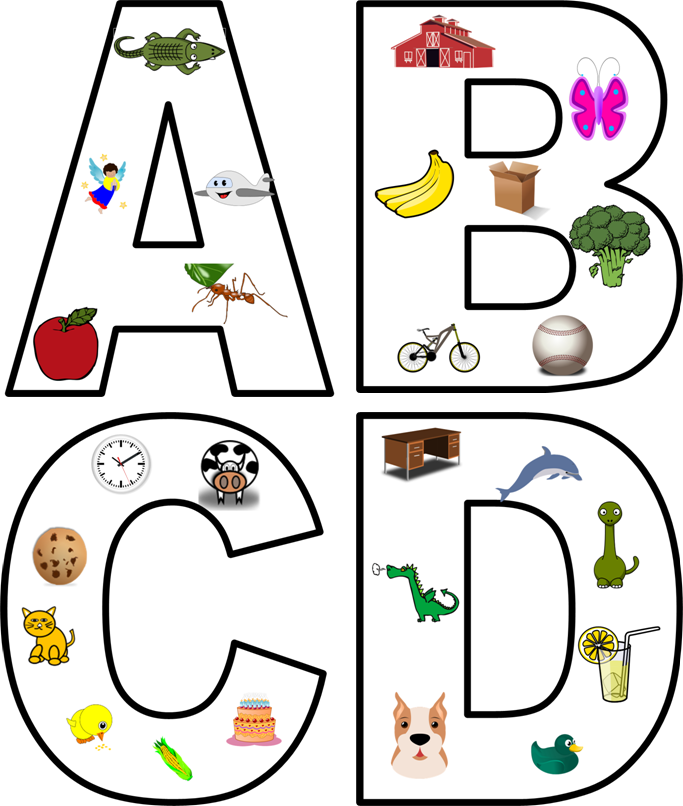

3. Activity: Go through each of the objects or animals that are inside the letter A. Say the name of each thing and make each object’s beginning sound before saying the whole word. This will help your little one understand the starting sound of each picture they see.

Activity: Go through each of the objects or animals that are inside the letter A. Say the name of each thing and make each object’s beginning sound before saying the whole word. This will help your little one understand the starting sound of each picture they see.

They will color each thing that starts with the letter A!

I have beginning sound sheets for each letter of the alphabet! Create a booklet to go over each of the sounds that the letters make. This will make for a great resource to use repeatedly.

Activity #9: Alphabet Apple Tree Matching

Dot stickers are one of my favorite supplies! They are so versatile. In this specific activity, they work perfectly as pretend apples!

This is a great activity to learn about the differences between upper and lower case letters.

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- cardstock paper

- toilet paper rolls

- dot stickers

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: Create the trees by making a tree shape on the cardstock paper. Write an upper case letter on one tree and a lower case letter on the other. Then cut two small slits in the toilet paper roll at the top. Place the cardstock paper inside the slits.

Set-up: Create the trees by making a tree shape on the cardstock paper. Write an upper case letter on one tree and a lower case letter on the other. Then cut two small slits in the toilet paper roll at the top. Place the cardstock paper inside the slits.

Write a bunch of upper and lower case letters on red, yellow, and green dot stickers!

3. Activity: Have your little ones peel off the dot stickers and place them on the correct tree! Peeling the stickers is a great fine motor activity for kids to practice. The kids can also count many upper and lower case letter dots there are.

RELATED: FUN Fine Motor Activities For Kids

Activity #10: Ripped Letter Craft

Ripped paper crafts are a favorite around here. Kids love the chance to be able to rip paper! They actually get to rip something without getting in trouble!

This is a simple and craft for adults to prep and for kids to do!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

Materials you need:

- white cardstock paper

- red, green, and brown construction paper

2. Set-up: Create an upper and lower case letter A on cardstock paper.

3. Activity: Your child will rip construction paper and paste them all around the letters. The goal is to try to cover the entire letter!

Activity #11: Letter Sensory Bin

Rainbow rice is a colorful and exciting sensory filler to play with! Kids love the rice feel, it stays good for months, and the colors are amazing!

Making rainbow rice is really simple, and it takes only about 5 minutes to make it!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- My FREE Rainbow Letter Mats

- fine motor tools

- letter A toys (from puzzles, wood letters, or magnetic letters)

- rice

- food coloring

- ziplock bags

- parchment paper

- baking sheet

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: Create the rainbow rice and print off the letter A rainbow letter mats.

Set-up: Create the rainbow rice and print off the letter A rainbow letter mats.

*How to create rainbow rice*

a. Dump 1 cup of rice into a ziplock bag.

b. Add in a few drops of food coloring or liquid watercolors.

c. Close the bag and shake it up until it’s covering all the rice

d. On a baking sheet, place parchment paper down and dump the rice onto the paper to dry. Make sure to spread it out to dry quicker.

e. Repeat this process for all the colors you want to do!

3. Activity: Once the rice dries, dump it into a sensory bin! Place all your letter A toys in the bin. You can place them on top or hide them in the rice. Your little ones will use the fine motor tools to search through the rice to find the letters. They will then place them on the correct upper or lower case mat!

RELATED: The BEST Sensory Bins for Kids

Activity #12: Letter Scavenger Hunt

Do you kids like to sit and learn all the time, or do you think they would love to move and learn?

I was a physical education teacher for 10 years, so I know in most cases, kids love movement and want to be active while they learn and not just sit!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

Materials you need:

- painter’s tape

- hula hoop

- letter A objects

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: With painter’s tape, make the letter A on the floor. Then, place a hula hoop over that letter!

3. Activity: Have your little ones go around the house and find objects that start with the letter A. If you have a younger one, place the objects out around the house so it’ll be easier for them to find. If you have an older one, challenge them to search for these objects and figure out which things would start with the letter A.

RELATED: Entertaining Indoor Activities For Kids

Activity #13: Letter Sprinkle Sweep

When are sprinkles not a good idea?

When you mention that sprinkles are involved in a learning activity, I promise your kids are going to come bounding in ready to see what’s going on.

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

Materials you need:

- art tray

- cardstock paper

- marker

- sprinkles

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: On a piece of cardstock paper, write a big bubble letter A. Place a tray underneath the paper to help with the mess.

3. Activity: Dump a bunch of cookie sprinkles onto the tray. Ask your little one to use the paintbrush to “sweep” the sprinkles into the letter. They will use as many sprinkles as they need to to try to fill in as much of the letter as they can!

This is an excellent activity to work on fine motor skills and letter recognition, and pre-writing skills!

RELATED: FUN Handwriting Activities For Kids

Activity #14: LEGO Letters

Got a kiddo who loves to use building with blocks? This activity will be right up their alley!

LEGO’s are an open-ended toy that I absolutely love using for learning activities. The possibilities are endless when it comes to using them!

The possibilities are endless when it comes to using them!

Building letters is just one way that they can be used! This is a wonderful hands-on learning activity that helps kids understand how each letter shape is formed!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- CLICK HERE FOR My LEGO Letter Building Mats

- LEGO’s

View Amazon's Price

2. Set-up: Print off the sheets and grab your LEGO’s

3. Activity: Your child will use the blocks that you have to create the letter A. You can have them use little or DUPLO blocks for this activity. This activity asks them to identify what each letter is they create and how many blocks it took for them to create the letter. If you decide to do more letters than just A, they can see the letters’ differences!

RELATED: The BEST Open-Ended Toys For Kids

Activity #15: Popsicle Stick Letter Building

Building letters with popsicle sticks work on SO many different learning skills.

This specific activity works on letter recognition, counting skills, STEM skills, and pre-writing skills! It’s perfect for school centers or just for home learning!

How to do this activity:

1. Materials you need:

- CLICK HERE FOR My popsicle stick letter cards

- popsicle sticks

- pencil

View Amazons Price

2. Set-up: Print off the letter cards and grab the popsicle sticks!

3. Activity: Your kids will use the cards to help them know how to create each letter! Count how many popsicle sticks it takes to create the letters.

Final Thoughts and Conclusion

Individual letter activities are a fantastic way for kids to really grasp letter recognition of each letter of the alphabet! Doing some of these activities will help your little ones remember each letter of the alphabet.

To go along with these activities, I suggest reviewing the alphabet letters once a day for at least 5 minutes. That’s it! 5 minutes is all it takes if you consistently go over the information with them; you’re going to see how they can pick up the information if repeated daily.

That’s it! 5 minutes is all it takes if you consistently go over the information with them; you’re going to see how they can pick up the information if repeated daily.

Do you have a favorite activity that you do in your classroom or at home with your kids for the letter A? Our community would love to hear about it! We all benefit from sharing our teaching strategies and activities. Leave a comment below to let us know about some ways you like to teach the letter A.

Happy Learning!

12 Awesome Letter A Crafts & Activities

ByLiz Updated on

It is time to get creative with these Letter A crafts! A is the first letter of the alphabet. Apples, angels, alligators, airplanes, apple trees, avocados, aardvark…there are many words that start with the letter A. Today we have some fun preschool letter A crafts & activities to practice letter recognition and writing skill building that work well in the classroom or at home.

Learning the Letter A Through Crafts & Activities

These awesome letter A crafts and activities are perfect for kids ages 2-5. These fun letter alphabet crafts are a great way to teach your toddler, preschooler, or kindergartener their letters. So grab your paper, glue stick, and crayons and start learning the letter A!

Related: More ways to learn the letter A

This article contains affiliate links.

Letter A Crafts For Kids

1. A is for Angel Craft

This angel made from the letter A is a fun project and is easy to make. It’s so easy to make with paper, feathers, googly eyes, and pipe cleaners. Don’t forget the black marker to give the angel a smiley face.

2. A is for Apple Craft

This paper plate apple craft is the easiest apple craft we have here at Kids Activities Blog that makes it a great alphabet craft for even toddlers!

3. A Is For Alligator Craft

Make an A is for alligator craft where we turn the letter a into a green alligator! via Miss Marens Monkeys

The angel has angelic wings!4.

Ants On The Apple Craft

Ants On The Apple CraftTo work on the lowercase a, make this ants on the apple craft. Grab your red paint, black paint, and green paper, for this letter a craft. via Pinterest

5. A is for Alien Craft

Use your handprint to make a letter a alien. via Red Ted Art

6. A is for Acorn Craft

Use a lowercase a to make a paper acorn. via MPM School Supplies

7. Apple Tree Craft for the Letter A

Make an apple tree from construction paper and use a stickers to place apples on them! via 123 Homeschool 4 Me

8. Toilet Paper Roll A is for Airplane Craft

Turn the letter A into a toilet roll airplane! This is the perfect way to learn the letter a as well as recycle. So grab your paint and popsicle sticks use different colors to make the coolest airplane. via Sunshine Whispers

9. A is for Astronaut Craft

The best way to learn is by hands on crafts. This letter a astronaut is a fun alphabet craft. via Glued To My Crafts Blog

Aliens start with A and look very silly!Letter A Activities for Preschool

10.

Letter A Sound Activity

Letter A Sound ActivityUse this printable to work on the letter A sound and identify which images start with the letter a. This is such a great way to learn about letter sounds. via The Measured Mom

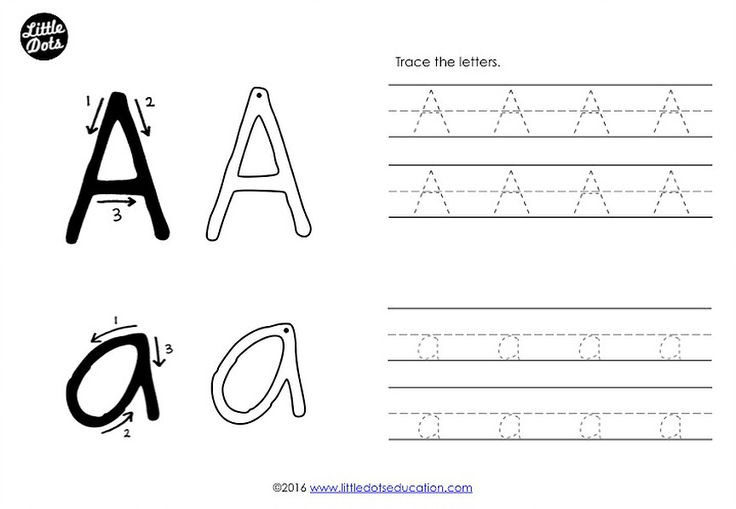

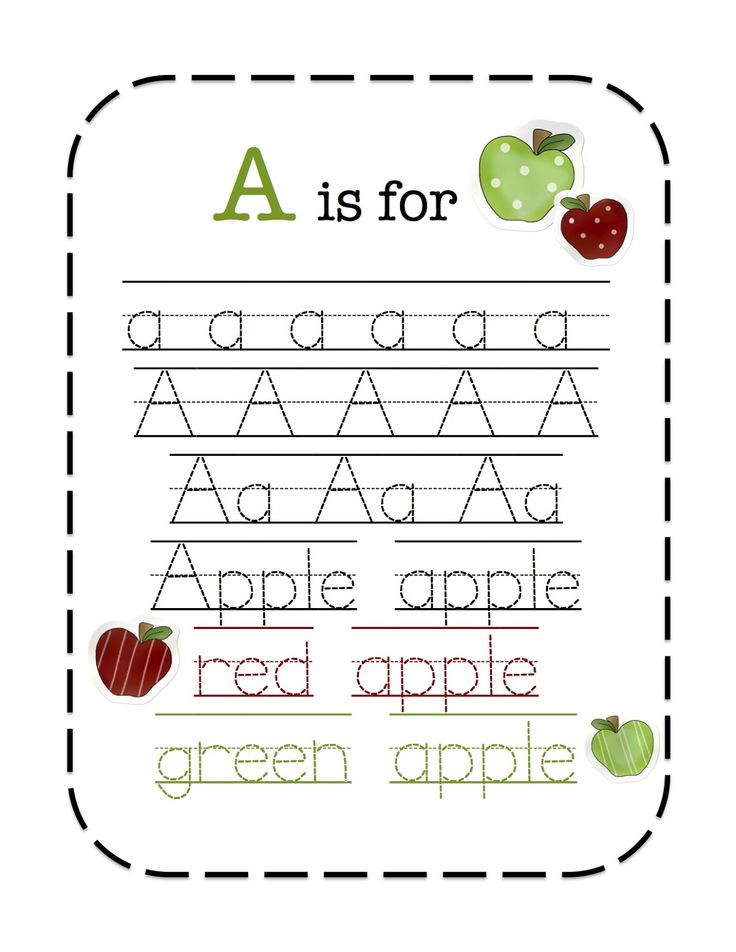

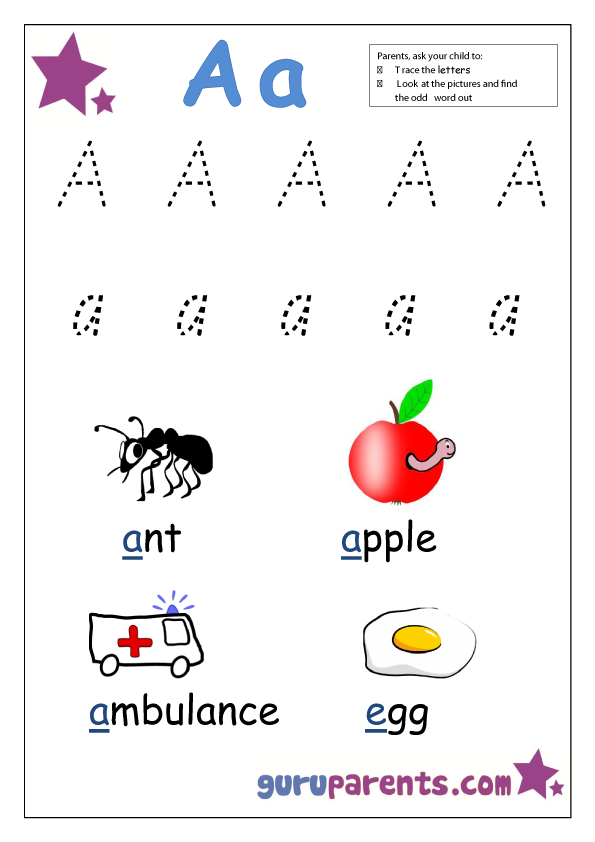

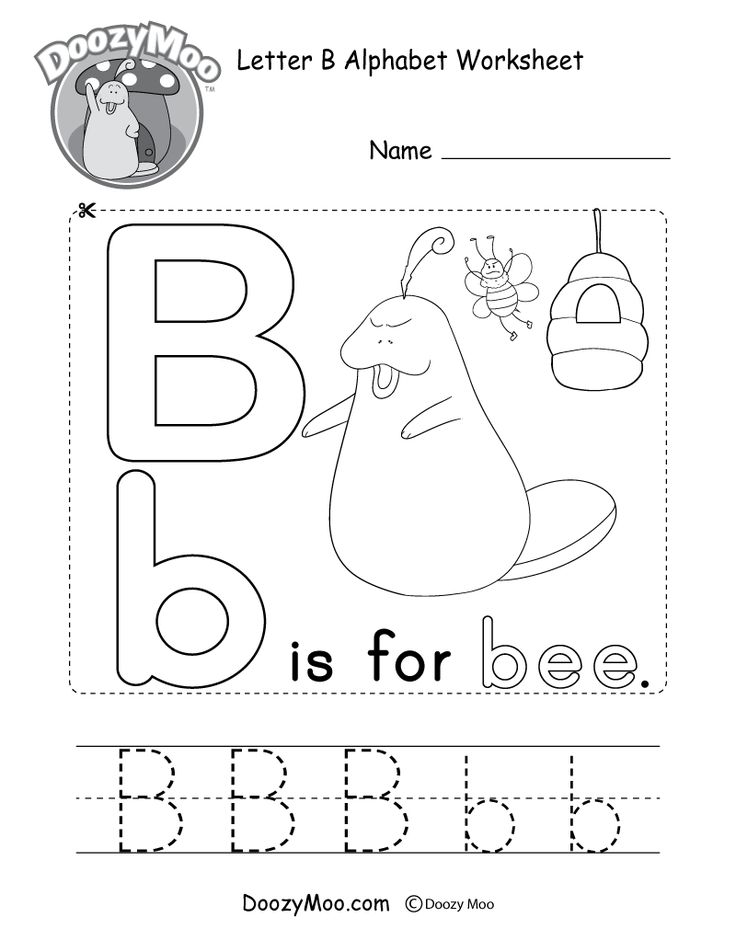

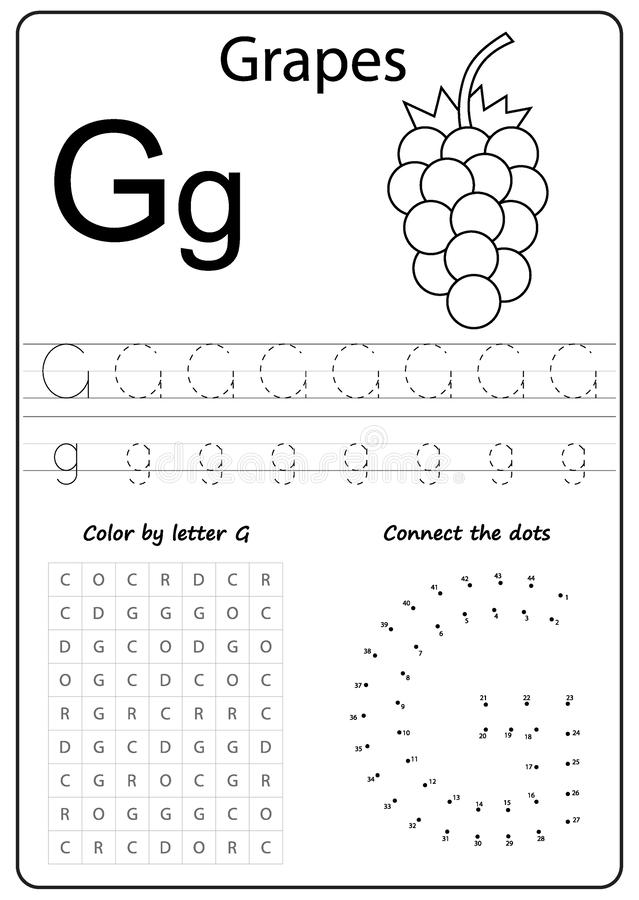

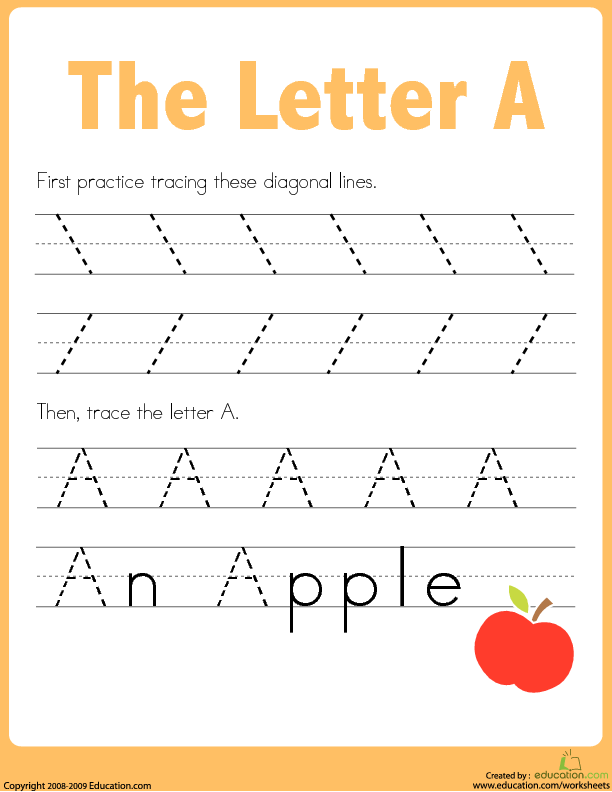

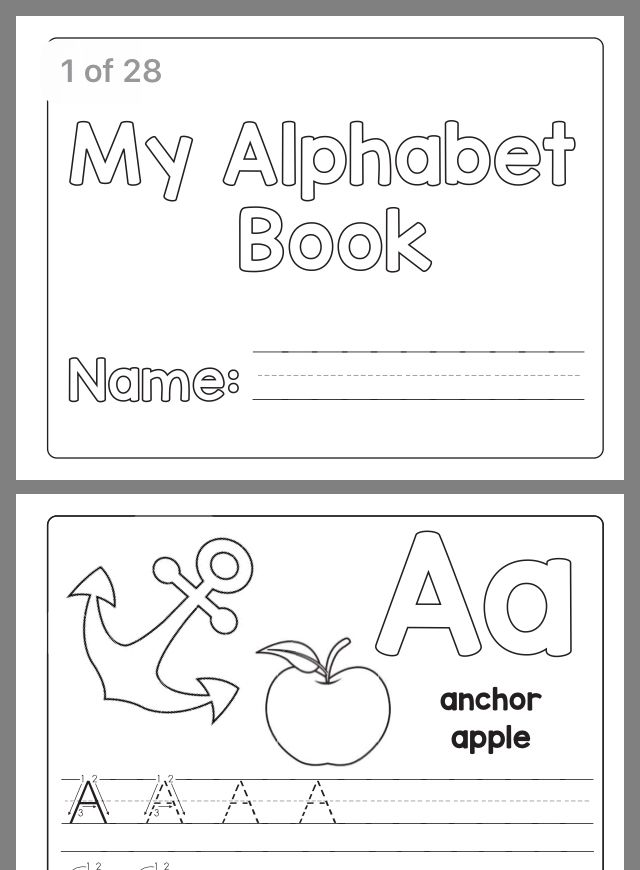

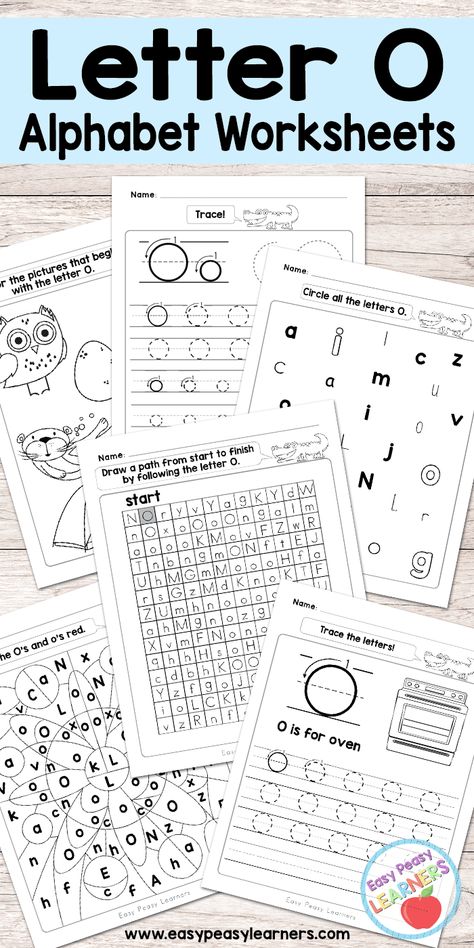

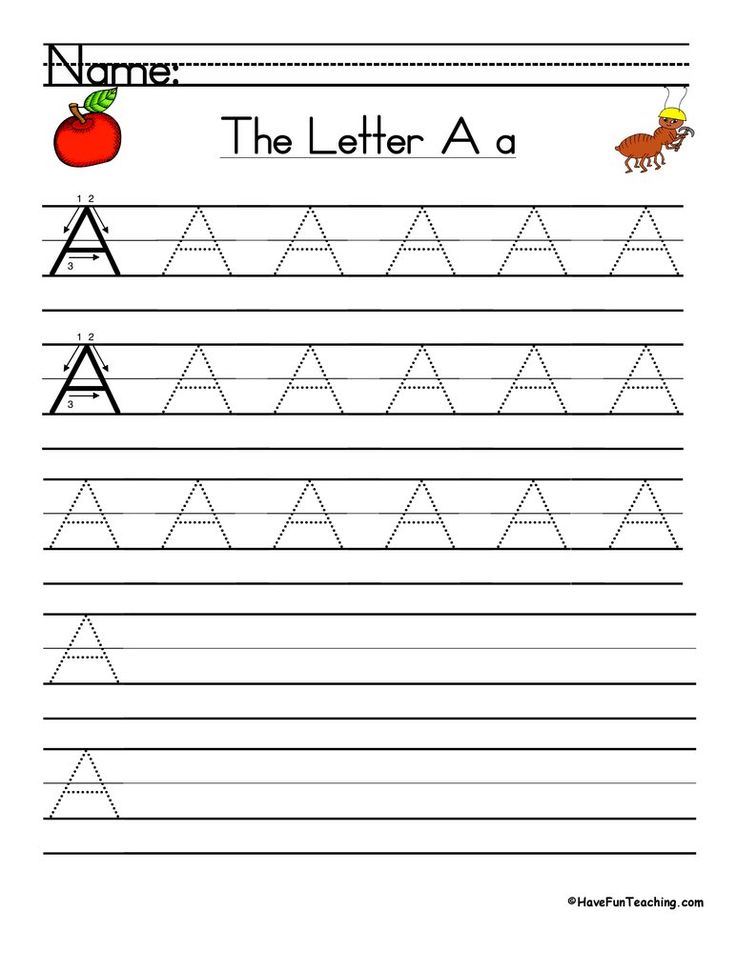

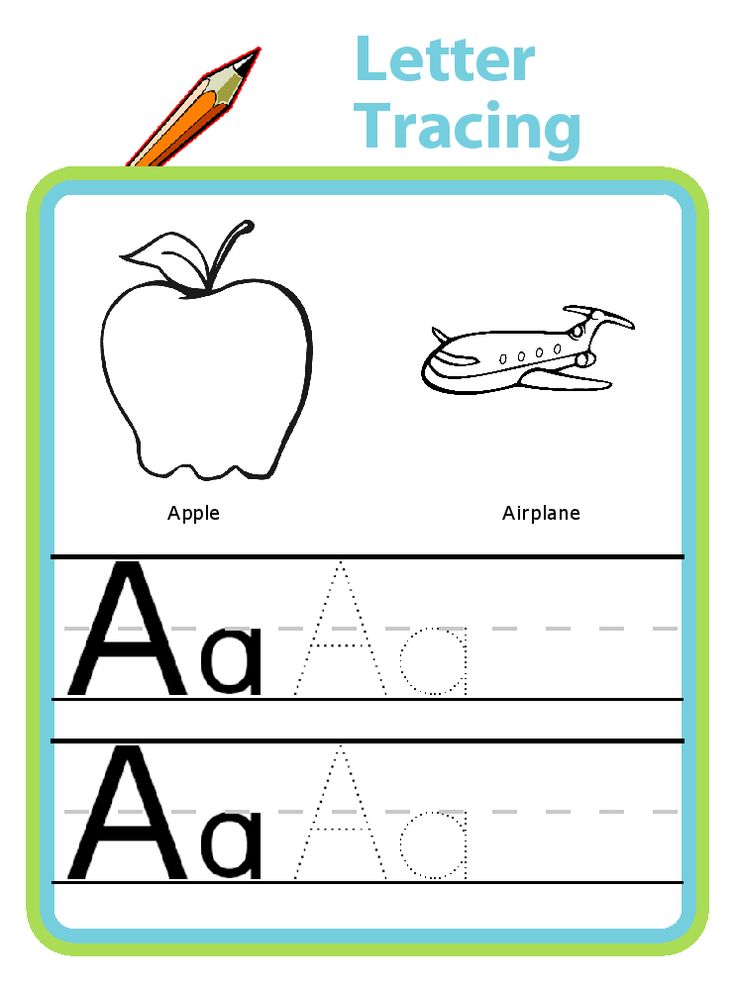

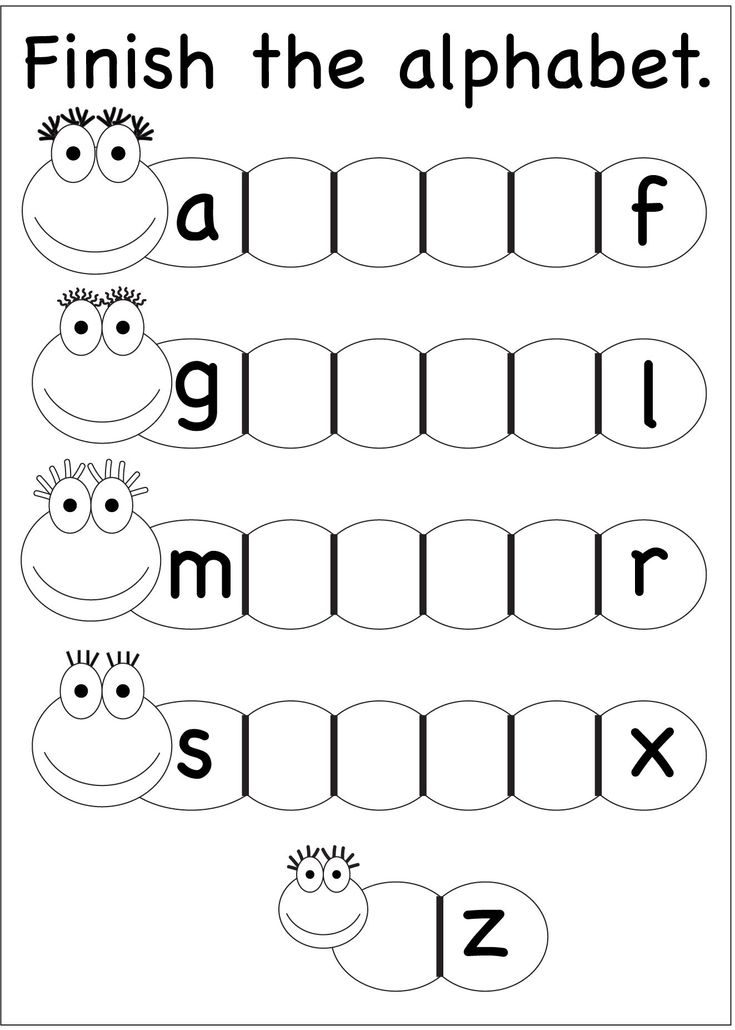

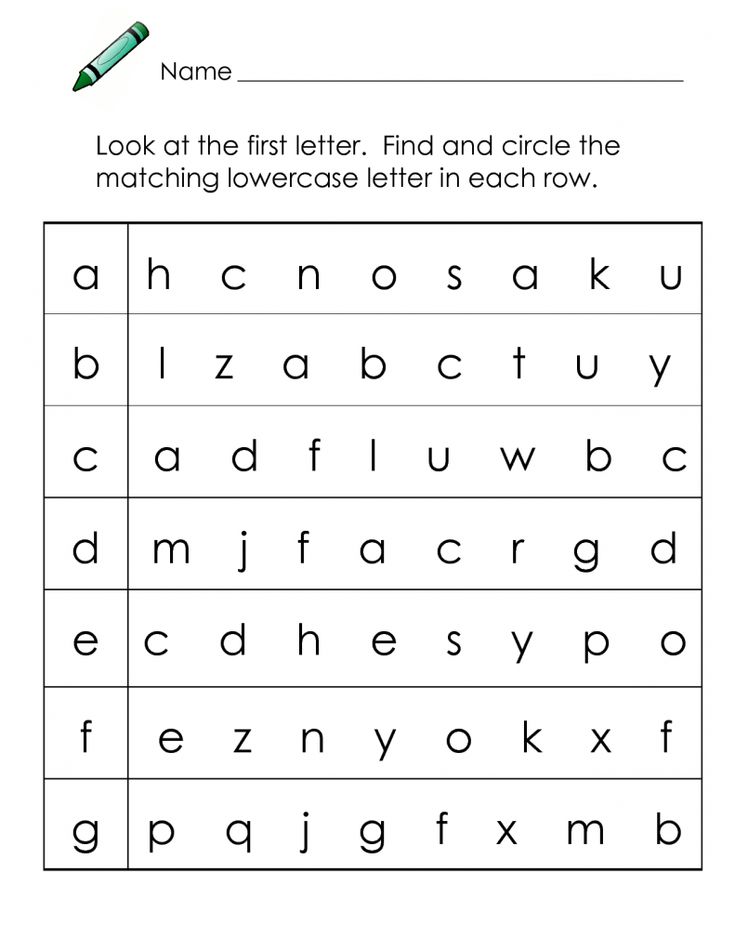

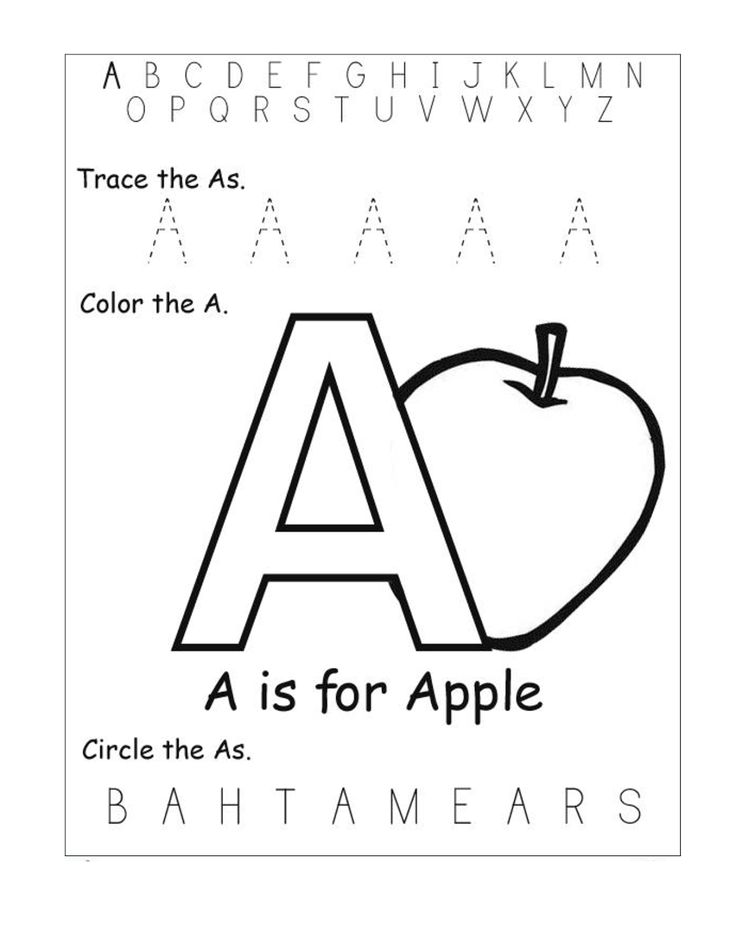

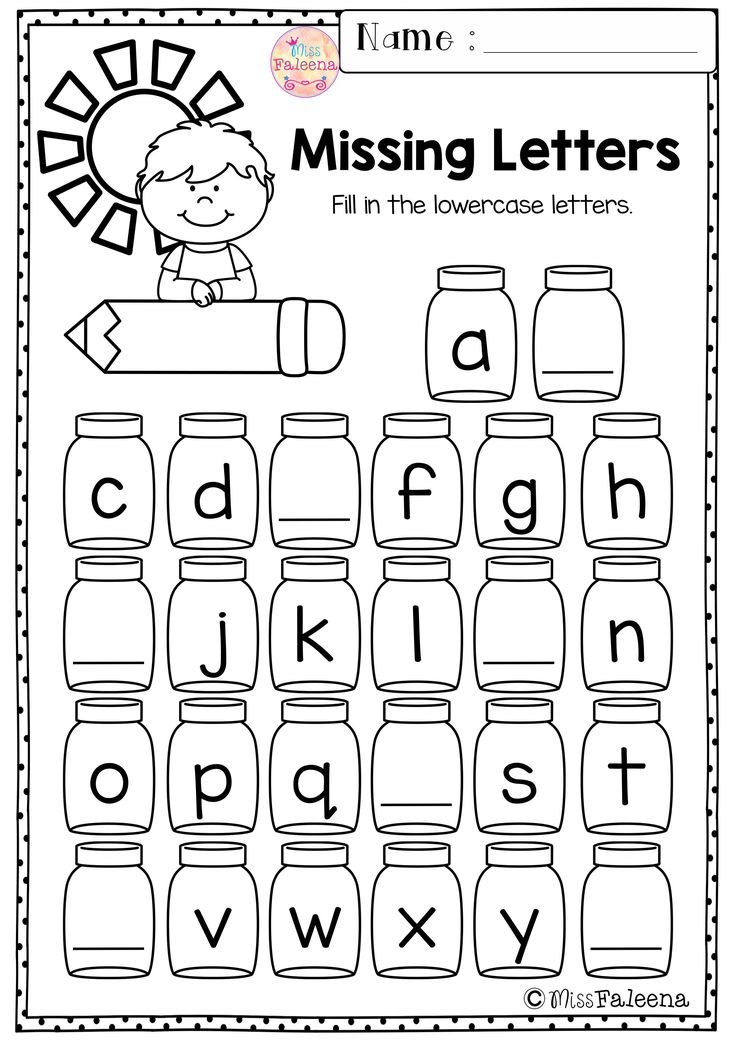

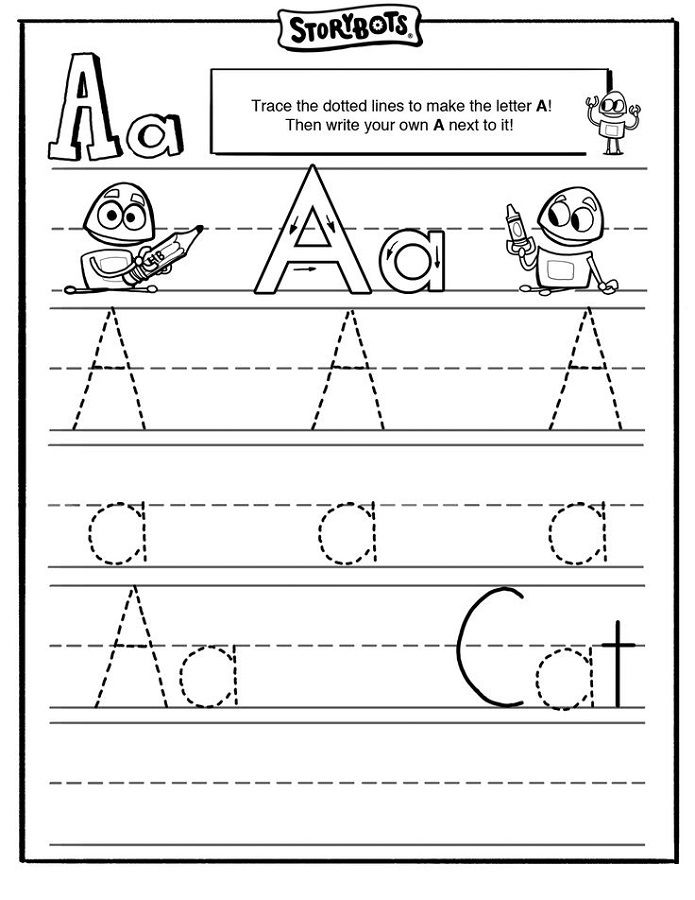

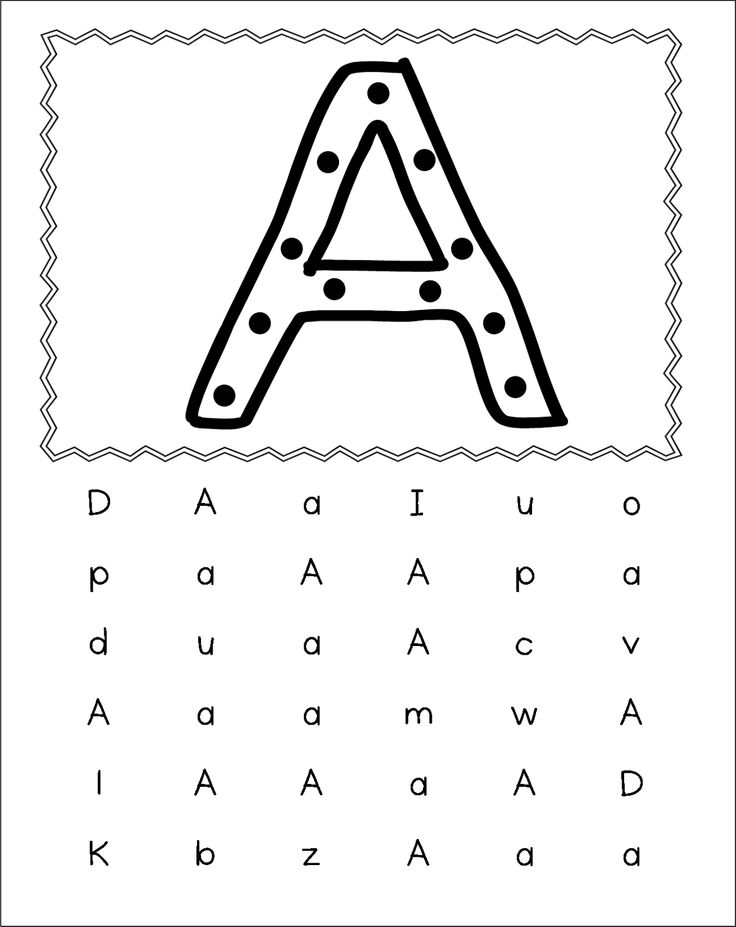

11. Letter A Worksheets

Grab these free letter A worksheets to work on tracing the letter and identifying which objects start with an a. What a great way to learn about upper case letters and lower case letters.

12. DIY Letter A Lacing Cards

Use these letter a lacing cards to practice the letter a and things that start with it. Plus, this is a great way to work on fine motor skills as well. Paper is great, but for a sturdier lacing card, you could back them with craft foam. via Homeschool Share

More Letter A Crafts & Printable Worksheets from Kids Activities Blog

We have even more alphabet craft ideas and letter A printable worksheets for kids. Most of these are also great for toddlers, preschoolers, and kindergarteners (ages 2-5).

- Free practice tracing the letter a worksheets are perfect for reinforcing the letter a and its uppercase letter and its lowercase letter.

- Use tissue paper to make this super amazing apple craft.

- Grab your paint, pom poms, and paper plates to make this apple tree craft.

- These alligator coloring pages are so much fun and an easy letter a craft.

- Here is another alligator craft! How cute are these little alligators?

More Alphabet Crafts & Preschool Worksheets

Looking for more alphabet crafts and free alphabet printables? Here are some great ways to learn the alphabet. These are great preschool crafts and preschool activities , but these would also be a fun craft for kindergarteners and toddlers as well.

- These gummy letters can be made at home and are the cutest abc gummies ever!

- These free printable abc worksheets are a fun way for preschoolers to develop fine motor skills and practice letter shape.

- These super simple alphabet crafts and letter activities for toddlers are a great way to start learning abc’s.

- Older kids and adults will love our printable zentangle alphabet coloring pages.

- Oh so many alphabet activities for preschoolers!

Which letter a craft are you going to try first? Tell us which alphabet craft is your favorite!

Liz

Liz chronicles her adventures in mommyhood at Love & Marriage.

I'm just a mom keeping it real about how little I sleep, how often I get puked on and how much I love them.

Competency-activity model of academic writing | Putilovskaya

1. Ostrovskaya E.S., Vyshegorodtseva O.V. Academic Writing: the concept and practice of academic writing in English // Higher education in Russia. 2013. No. 7. S. 104-113.

2. Bazanova E.M. Scientific Communication Laboratory: Russian Experience // Higher Education in Russia. 2015. No. 8/9. pp. 135-143.

3. Leontiev A.A. Language, speech, speech activity. Moscow: Education, 1969. 216 p.

4. Zimnyaya I.A. Linguistic psychology of speech activity. M., Voronezh: MODEK, 2001. 429 p.

5. Whitaker A. Academic Writing Guide 2010. Step-by-Step Guide to Writing Academic Papers. Bratislava, 2009. 29 p.

6. McCormack J, Slaght J. Extended Writing and Research Skills. Reading: Garnet Education, 2012. 52 p.

7. Korotkina I.B. Own and someone else's: problems of using sources in a scientific text // Higher education in Russia. 2015. No. 2. S. 142-150.

8. Mitrofanova O.D. Scientific style of speech: learning problems: method. allowance. M.: Russian language, 1985. 128 p.

9. Pleshchenko T.P., Fedotova N.V., Chechet R.G. Stylistics and culture of speech: textbook. allowance / Ed. P.P. Fur coats. Minsk: TetraSystems, 2001. 544 p.

10. Kotyurova M.P., Bazhenova E.A. Culture of scientific speech: text and its editing: textbook. allowance. M.: Flinta; Nauka, 2008. 280 p.

11. Greasy L.K. Formation of professionally oriented communicative competence in writing // Izvestiya SFU. Technical science. 2011. No. 10 (123). pp. 123-129.

Technical science. 2011. No. 10 (123). pp. 123-129.

12. Smirnova N.V. Academic literacy and writing at the university: from theory to practice // Higher education in Russia. 2015. No. 6. S. 58-64.

13. Graves D, Hansen J. The Author's Chair // Language Arts. 1983 Vol. 60(2). P. 176-183.

14. Zemach D.E., Rumisek L.A. Academic Writing from Paragraph to Essay. Macmillan Education, 2009. 138 p.

15. Sowton C. 50 Steps to Improving Your Academic Writing. Reading: Garnet Education, 2012. 272 p.

16. Dobrynina O.L. Grammatical errors in English academic writing: causes and correction strategies // Higher education in Russia. 2017. No. 8/9. pp. 100-107.

17. Popova N.G., Koptyaeva N.N. Academic Writing: IMRAD Articles. Yekaterinburg: IFiP URO RAN, 2014. 160 p.

18. Dugartsyrenova V.A. Difficulties in teaching foreign language academic writing // Higher education in Russia. 2016. No. 6 (202). pp. 106-112.

19. Mironov E.V. Formation of academic literacy of students: experience of the faculty of public administration // Higher education in Russia. 2013. No. 7. P. 101-104.

2013. No. 7. P. 101-104.

20. Popova N.G. Introduction to a scientific article in English: structure and composition // Higher education in Russia. 2015. No. 6. S. 52-58.

21. Korotkina I.B. Text as an input to scientific discussion: what is "focus"? // Higher education in Russia. 2015. No. 6. S. 44-51.

22. Haggan M. Research paper titles in literature, linguistics and science: dimensions of attraction // Journal of Pragmatics. 2004 Vol. 36. P. 293-317.

23. Abramov E.G. Selection of keywords for a scientific article // Scientific periodicals. 2011. No. 2. C. 35-40.

24. Leki I. Academic Writing: Exploring Processes and Strategies. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.464 p.

25. National standard of the Russian Federation. System of standards on information, librarianship and publishing. Bi-bliographic link. General requirements and rules for compilation. OKS 01.140.30. Introduction date 2009-01-01.

26. Modern Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. A Common European Framework of Reference. Council for Cultural Cooperation. Education Committee. Strasbourg (1998). 224p.

A Common European Framework of Reference. Council for Cultural Cooperation. Education Committee. Strasbourg (1998). 224p.

27. Putilovskaya T.S. The role of the strategic component of communicative competence in teaching academic writing // Sociology. Journal of the Russian Sociological Association. 2017. No. 4. pp. 200-210.

28. Putilovskaya T.S. Competence-activity structure of speech behavior in situations of business, professional and scientific communication // Sociology. Journal of the Russian Sociological Association. 2018. No. 1. pp. 123-135.

What develops and what does not develop the educational activity of younger schoolchildren

When any system of developmental training or education is discussed, it is customary to indicate the development of which particular abilities of the child this system undertakes to provide. It is not customary, however, to ask what this system of education cannot develop, the development of what age-related potentials it hinders. Putting the question in this way, I want to emphasize the danger and responsibility choosing the direction of development , which adults make for the child, placing him in one or another educational institution, that is, offering him a completely specific (note: not determined by the child) subject of joint activity and an equally specific type of educational relationship.

Putting the question in this way, I want to emphasize the danger and responsibility choosing the direction of development , which adults make for the child, placing him in one or another educational institution, that is, offering him a completely specific (note: not determined by the child) subject of joint activity and an equally specific type of educational relationship.

Declaring its goals and intentions, that is, denoting the direction of development of its pupils, each domestic psychological and pedagogical school, in the self-name or self-definition of which there is the word "development", swears allegiance to the ideas of L. S. Vygotsky. All these schools proceed from a single premise about the potentially universal and universal nature of man [19], but they interpret the relationship between learning and development in their own way. A constructive result of the simultaneous existence of different schools, deriving their genealogies from a single theoretical source, was a non-linear representation of the zone of proximal development, and, consequently, the relationship between learning and development. It became obvious that different psychological and pedagogical schools intend to lead the child from the same point of actual development in different directions, using their own specific educational technologies for this. But the same child cannot be led both to the left and to the right at the same time.

It became obvious that different psychological and pedagogical schools intend to lead the child from the same point of actual development in different directions, using their own specific educational technologies for this. But the same child cannot be led both to the left and to the right at the same time.

Of course, the choice of the possible direction of a child's development is a matter of purely value and is not verified in the scientific categories of truth or falsity. The disputes raging today between adherents of various areas of developmental education or education often flare up on the sovereign and untouchable territory of the value self-determination of each psychological and pedagogical school. Meanwhile, the question of the merits of one or another technology of developmental education and the compatibility of the best elements of different technologies is correct to raise only where the directions of development chosen on value grounds basically coincide. Within the scientific community, all of us - the creators and designers of educational systems - are obliged to be responsible for the consistency of the declared goals and the means of developmental education used. Precisely specifying the goals of education, that is, honestly saying what a certain educational system develops and what does not develop, is our duty to teachers and parents who choose this or that educational system, based mainly on what its authors promise.

Within the scientific community, all of us - the creators and designers of educational systems - are obliged to be responsible for the consistency of the declared goals and the means of developmental education used. Precisely specifying the goals of education, that is, honestly saying what a certain educational system develops and what does not develop, is our duty to teachers and parents who choose this or that educational system, based mainly on what its authors promise.

All these eternally difficult problems of choice are doubly difficult for those whose personal and professional development took place under Soviet rule, because in the USSR the problem of choosing the direction of a child's development through the choice of the educational system did not exist. In all schools of a vast territory, a single general education school reigned, which quite successfully, of course, with a certain percentage of defects, fulfilled the main state order: it molded the type of thinking and personality that the totalitarian regime demanded - conscientious and diligent workers who did not have independence and initiative in accepting decisions, people committed to the goals of the team and uncritical in relation to the leaders.

The Elkonin-Davydov system, one of the most influential "new" educational systems, which arose in line with the Vygotsky school in the late 1950s, could not receive wide social recognition until recently and remained a purely academic study of the age-related capabilities of children of primary school age [3]. In terms of its values, this educational system was essentially dissident, because it contradicted the social order of the state and, moreover, sought to develop in its pupils qualities that were dangerous and inconvenient in the Soviet community: independence of judgments and actions, independence from authorities, criticality towards one’s own and other people's actions, initiative in setting new tasks, the ability and inclination to transform existing modes of action if they conflict with the new conditions of action.

Based on the concept of psychological age as a space of children's opportunities, only partially realized by the education system, D. B. Elkonin formulated the hypothesis that the level of intellectual achievements, which, under the then existing (and prevailing to this day) system of primary education, is demonstrated only by gifted children of 6-12 years old, becomes available to the majority of younger schoolchildren when teaching a different type [16]. It was about the ability of gifted children, after the first attempts to solve a new problem, to single out its most essential conditions and then, focusing on them, solve all problems of the same class "from the spot", practically without errors [1]. D. B. Elkonin suggested that if, at the very first step of teaching a new subject, an adult helps children to do what the gifted do without outside help: to identify and fix the connections that are most significant for this subject, then most of the younger students can form the ability to reflect , which, with spontaneous development, is considered the lot of the elite. To transform this hypothesis into a theory of learning activity as a form of development of the theoretical consciousness of junior schoolchildren [5], a forty-year experiment was required, conducted under the guidance of V.

B. Elkonin formulated the hypothesis that the level of intellectual achievements, which, under the then existing (and prevailing to this day) system of primary education, is demonstrated only by gifted children of 6-12 years old, becomes available to the majority of younger schoolchildren when teaching a different type [16]. It was about the ability of gifted children, after the first attempts to solve a new problem, to single out its most essential conditions and then, focusing on them, solve all problems of the same class "from the spot", practically without errors [1]. D. B. Elkonin suggested that if, at the very first step of teaching a new subject, an adult helps children to do what the gifted do without outside help: to identify and fix the connections that are most significant for this subject, then most of the younger students can form the ability to reflect , which, with spontaneous development, is considered the lot of the elite. To transform this hypothesis into a theory of learning activity as a form of development of the theoretical consciousness of junior schoolchildren [5], a forty-year experiment was required, conducted under the guidance of V. V. learning and a new system for diagnosing its developmental effects [10].

V. learning and a new system for diagnosing its developmental effects [10].

The main novelty of this system of education lies in the idea of VV Davydov that an introduction to a subject should begin with the discovery by children of the most general properties of this subject. Students discover these common properties as a result of actions to transform the original subject of study in its sensually perceived form and fix it in the model. Further study of the subject unfolds as concretization, enrichment of the original general concept when meeting with new facts [4]. The movement from the general to the particular, or, in the terminology of W. F. Hegel, "the ascent from the abstract to the concrete" occurs in situations where children encounter contradictions between the knowledge fixed in the model and a new fact. The resolution of these contradictions leads to the enrichment of the original concept.

Let me illustrate this general point using the example of teaching Russian spelling to children. It has the following general law: there are sounds that can be designated by letters by ear (act according to the rule "what I hear, I write"), and there are sounds for which several letters "argue" and which are risky to write by ear. These sounds form orthograms, and the choice of a letter when writing an orthogram presents an orthographic task. There are several dozen such classes of spelling problems, private ways to solve them children are taught for 6-8 years; and this is what the traditional teaching of spelling in the Russian school boils down to.

It has the following general law: there are sounds that can be designated by letters by ear (act according to the rule "what I hear, I write"), and there are sounds for which several letters "argue" and which are risky to write by ear. These sounds form orthograms, and the choice of a letter when writing an orthogram presents an orthographic task. There are several dozen such classes of spelling problems, private ways to solve them children are taught for 6-8 years; and this is what the traditional teaching of spelling in the Russian school boils down to.

In the Elkonin-Davydov system, before teaching children particular ways of solving certain classes of spelling problems, they are taught the general way of setting any spelling problem [8]. In the 1st grade, even before studying specific types of orthograms, children discover the very existence of a spelling as a problem of choosing a letter and learn to ask (adult, dictionary, reference book) about each spelling unknown to them. If it is possible to teach a child systematic "spelling doubt", which is based on the ability to separate known and unknown spellings, then it is possible to ensure error-free writing long before knowing all the specific spelling rules. A special check [13] showed that at the end of class III 92% of the students who studied according to the Elkonin-Davydov system were able to write an extremely complex dictation without errors precisely because they were able to ask all the necessary spelling questions. Only 24% of the students who studied according to the traditional system coped with this task.

If it is possible to teach a child systematic "spelling doubt", which is based on the ability to separate known and unknown spellings, then it is possible to ensure error-free writing long before knowing all the specific spelling rules. A special check [13] showed that at the end of class III 92% of the students who studied according to the Elkonin-Davydov system were able to write an extremely complex dictation without errors precisely because they were able to ask all the necessary spelling questions. Only 24% of the students who studied according to the traditional system coped with this task.

Such a difference in the ability of children to independently set new spelling tasks is determined primarily by the way they learn. Some children knew the general concept "spelling", on the basis of which one can recognize any, even for the first time, spelling, think about choosing a letter, ask an adult for the missing information and not make a mistake, other children knew only particular methods for solving certain classes of spelling problems, and in unknown cases, they acted at random, unaware of the possibility of making a mistake.

Now let's do a thought experiment. Let us invite all these children to further improve their literacy on their own by providing them with excellent reference books, self-study books and the schedule of work of teacher-advisers. Which group of children will be in a better position? Of course, the one that knows how to independently determine what they do not yet know, what to ask the consultant about, what to look for in the handbook, that is, they know how to set new learning goals. In other words, education according to the Elkonin-Davydov system forms ability to teach yourself on your own . Reflexive in nature, the ability to separate the known from the unknown and to make an assumption about the content of the unknown (but not yet the ability to independently look for ways to test the stated hypotheses) is the level of educational independence that is available to most 10-11-year-old schoolchildren who studied in elementary school according to the system Elkonin - Davydov [10].

The works of VV Davydov describe in detail the subject and structure of children's learning activities aimed at finding and developing common methods for solving problems. Therefore, here I will allow myself to very briefly name only the most essential characteristics of educational activity; At the same time, the focus of consideration will not be a practical question: how it is organized, but a semantic question: why is it organized in this way.

1. Why and how is the educational activity of younger students organized?

When a child first sits down at a desk, he already has his own concept of numbers, words, social norms - everything that they are going to be taught at school. The child's naive, worldly concept is significantly different from the adult, teacher's, but the child is unaware of this. Because of this, situations of multi-subject interaction often arise in the classroom, when children and adults use the same term to name different objects. If the teacher, sharing the goals and values of the creators of the system of educational activities, sees in the child not tabula rasa , and the person with whom it is necessary to negotiate the general grounds for joint action , i.e. to build a common concept (common both for the class of tasks and for all participants in joint educational activities), then he has to almost simultaneously solve the following pedagogical tasks:

If the teacher, sharing the goals and values of the creators of the system of educational activities, sees in the child not tabula rasa , and the person with whom it is necessary to negotiate the general grounds for joint action , i.e. to build a common concept (common both for the class of tasks and for all participants in joint educational activities), then he has to almost simultaneously solve the following pedagogical tasks:

I. To create a situation in which the child discovers: a) his own, as a rule, non-normative, idea of the phenomenon under discussion, b) the existence of other ideas, other points of view, c) the insufficiency of his idea for solving a new problem, or to defend your own opinion. If the teacher manages to present to the children the sides of a conceptual contradiction through the clash of their own points of view, then educational task , aimed at introducing a new concept, can be considered set, that is, emotionally captured by children. It is clear that the setting of the educational task is achieved only through the organization of discussion in which the teacher helps the children to fix all the expressed points of view and see the internal logic of each of them. It is also clear that in elementary school the setting of a learning task should be carried out primarily in the form of objective and game actions that provide a sensory-figurative basis for emerging concepts, and not only in the form of verbal disputes [7], [18].

It is clear that the setting of the educational task is achieved only through the organization of discussion in which the teacher helps the children to fix all the expressed points of view and see the internal logic of each of them. It is also clear that in elementary school the setting of a learning task should be carried out primarily in the form of objective and game actions that provide a sensory-figurative basis for emerging concepts, and not only in the form of verbal disputes [7], [18].

II. To give the child a tool for retaining and analyzing a sensually elusive abstraction before its verbal description. This tool is schemes and other sign-symbolic means that describe both the subject of study and the method of its transformation [12]. Schemes, which in the practice of educational activity are used primarily as a means of obtaining and storing new knowledge, are at the same time a written monument of the discoveries made by children; the scheme is what the most dramatic event of educational activity is molded into - the search for a solution to the educational problem. The schema built by a class as a result of the acutely experienced drama of ideas and the struggle of opinions, even if it is exactly similar to the schemas built in a hundred other classes, is copyright work; pointing a finger at it, the child says: "We discovered it ourselves. And now I have the right to use this discovery as the basis of my action." It is not necessary to imagine the scheme, which is the first language for the student to describe his knowledge and ignorance, as dry theoretical jargon, alienated from the speaker, devoid of sensuality and emotionality. Such a language of schemes can become if it turns from a means of educational communication into its ultimate goal, if the student builds a scheme in order to complete the task of the teacher and earn his praise, and not in order to solve a problem that is significant for him or express his point of view .

The schema built by a class as a result of the acutely experienced drama of ideas and the struggle of opinions, even if it is exactly similar to the schemas built in a hundred other classes, is copyright work; pointing a finger at it, the child says: "We discovered it ourselves. And now I have the right to use this discovery as the basis of my action." It is not necessary to imagine the scheme, which is the first language for the student to describe his knowledge and ignorance, as dry theoretical jargon, alienated from the speaker, devoid of sensuality and emotionality. Such a language of schemes can become if it turns from a means of educational communication into its ultimate goal, if the student builds a scheme in order to complete the task of the teacher and earn his praise, and not in order to solve a problem that is significant for him or express his point of view .

III. To make the task meaningful, for this the question should be asked not by the teacher, but by the children. The transition from the relationship "asking teacher - answering student" to the relationship "asking student - teacher helping the child to formulate his question and find an answer to it" - this is the main condition for educating a younger student as a subject educational, and not performing activity. The most difficult pedagogical task of a teacher who builds learning (and not any other) activity is the task of self-change: the teacher has to overcome the stable illusion that the child is learning when he finds the right answers to the teacher's questions. The child learns when he asks himself, he himself builds hypotheses about the unknown and seeks to test them (for example, with the help of a teacher who organized the situation of asking and searching for the unknown). Answering questions not asked by children is, unfortunately, the single principle of constructing most traditional curricula and manuals, the general way teachers work in most schools and universities. If it is possible to educate a student who asks the teacher, and not only answers the teacher's questions, then such a student develops the ability to learn - independently set new learning goals and independently find means to achieve them [14].

The transition from the relationship "asking teacher - answering student" to the relationship "asking student - teacher helping the child to formulate his question and find an answer to it" - this is the main condition for educating a younger student as a subject educational, and not performing activity. The most difficult pedagogical task of a teacher who builds learning (and not any other) activity is the task of self-change: the teacher has to overcome the stable illusion that the child is learning when he finds the right answers to the teacher's questions. The child learns when he asks himself, he himself builds hypotheses about the unknown and seeks to test them (for example, with the help of a teacher who organized the situation of asking and searching for the unknown). Answering questions not asked by children is, unfortunately, the single principle of constructing most traditional curricula and manuals, the general way teachers work in most schools and universities. If it is possible to educate a student who asks the teacher, and not only answers the teacher's questions, then such a student develops the ability to learn - independently set new learning goals and independently find means to achieve them [14].

In the course of experiments on the organization of educational activities in elementary school lessons, it was proved that the first children's questions and hypotheses are born most successfully if the teacher organizes the joint actions of the children themselves so that different points of view on the problem under discussion are distributed not between a child and an adult, and between peers - equally ignorant, equally inept, equally imperfect partners [13]. At the same time, children almost inevitably discover the inconsistency of different logics, the partiality of their own rightness.

So, the specific content built in the logic of ascending from the most general, essential to more and more specific properties of the subject being studied, and the specific form of cooperation, which allows polarizing different points of view to identify their foundations, distinguish learning activity from other types of activity existing in the school at every lesson. The purpose of the learning activity: by organizing a search for common ways of action , an adult creates conditions for the development in children of the ability to separate the known from the unknown and formulate questions - hypotheses about the unknown. The basis of these skills is defining reflection , which reveals itself in the student's objective actions as the ability to learn new skills, in communication - as the ability to see the difference in points of view, in self-consciousness - as an interest in self-change. The connection of a new (reflexive) type of generalization with a new (positional, allowing one to distinguish the positions of partners) method of communication - is the connection of the INTRA- and INTERpsychic stages of development of the ability (ability) to teach and change oneself, i.e. to go beyond the boundaries of one's own knowledge and skills.

The purpose of the learning activity: by organizing a search for common ways of action , an adult creates conditions for the development in children of the ability to separate the known from the unknown and formulate questions - hypotheses about the unknown. The basis of these skills is defining reflection , which reveals itself in the student's objective actions as the ability to learn new skills, in communication - as the ability to see the difference in points of view, in self-consciousness - as an interest in self-change. The connection of a new (reflexive) type of generalization with a new (positional, allowing one to distinguish the positions of partners) method of communication - is the connection of the INTRA- and INTERpsychic stages of development of the ability (ability) to teach and change oneself, i.e. to go beyond the boundaries of one's own knowledge and skills.

2. Why and how to distinguish learning activities from other activities present in the lesson?

The basis for posing such a question is the very concept of "leading activity", which can perform its function (set the main direction, leading theme, leitmotif of development) not as a solo instrument for the formation of new abilities (new formations), but only in a symphony of others ( non-leading) activities. The basis for answering this question can be the periodization of the leading types of activity proposed by D. B. Elkonin [17]. Taking into account the fact that any activity of a child begins as a joint activity with an adult and peers, the periodization of the leading forms of activity can be simultaneously read as a periodization of the leading forms of communication and cooperation specific to each activity.

The basis for answering this question can be the periodization of the leading types of activity proposed by D. B. Elkonin [17]. Taking into account the fact that any activity of a child begins as a joint activity with an adult and peers, the periodization of the leading forms of activity can be simultaneously read as a periodization of the leading forms of communication and cooperation specific to each activity.

Scheme 1 is a kind of score for designing and reading a lesson in all the variety of cooperative and communicative processes taking place there.

It differs from the classical scheme of DB Elkonin in two extensions. The first extension is related to the idea of E. Erickson [20] that no age ends with the onset of the next age. Once having appeared, this or that form of activity and cooperation should live while its bearer is alive. When it is born, it performs the leading function, that is, it determines the general direction of the child's mental development. Later, it continues to serve the range of life tasks for which it is intended, it has its own territory and its own tools (its own motives, goals, subject matter, means). If this does not happen, if one of the forms of cooperation does not develop or perishes, then this inevitably leads to a certain inferiority of the entire mental life of a person. The most difficult thing is the loss of basic trust in oneself, in the world and in people - a person reacts to the loss or impoverishment of direct-emotional communication - the earliest, basic form of a child's connection with the world. But no less traumatic are other injuries in the living body of cooperation. So, about a person who has not mastered object-manipulative cooperation (let me remind you that the improvement of this line also lasts a lifetime) they say that he has “both hands are left”, because the acquisition of any manual skill is given to him with difficulty. A person who has not learned or has forgotten how to play suffers from a poverty of imagination, which limits his creative possibilities.

Later, it continues to serve the range of life tasks for which it is intended, it has its own territory and its own tools (its own motives, goals, subject matter, means). If this does not happen, if one of the forms of cooperation does not develop or perishes, then this inevitably leads to a certain inferiority of the entire mental life of a person. The most difficult thing is the loss of basic trust in oneself, in the world and in people - a person reacts to the loss or impoverishment of direct-emotional communication - the earliest, basic form of a child's connection with the world. But no less traumatic are other injuries in the living body of cooperation. So, about a person who has not mastered object-manipulative cooperation (let me remind you that the improvement of this line also lasts a lifetime) they say that he has “both hands are left”, because the acquisition of any manual skill is given to him with difficulty. A person who has not learned or has forgotten how to play suffers from a poverty of imagination, which limits his creative possibilities. And the lack of formation of educational cooperation leads to the inability to learn, that is, to improve oneself in the sphere of thinking and activity for the rest of one's life.

And the lack of formation of educational cooperation leads to the inability to learn, that is, to improve oneself in the sphere of thinking and activity for the rest of one's life.

The second extension of DB Elkonin's scheme is a consequence of the first one. If none of the types of activity and cooperation mastered by the child, having given rise to its mental neoplasms, subsequently dies off, then the question of how it is restructured under the influence of the subsequent age-related achievements of the child and how it retains its morphological and functional autonomy is logical. As an example, direct-emotional communication between a child and an adult is improved under the influence of speech and other psychological neoplasms of the following ages and at the same time remains itself: an activity aimed at "cognizing and evaluating another person and searching for, clarifying the relationship of an adult to oneself" [ eleven; 279-280]? This question is answered by the periodization of forms of communication created by M. I. Lisina and her followers [6], which exists within other joint activities, not coinciding with them either in terms of goals or means.

I. Lisina and her followers [6], which exists within other joint activities, not coinciding with them either in terms of goals or means.

Scheme 1. Age periodization of the leading and undying forms of joint activity of a child and an adult

Double icons of scheme 1 indicate transitional forms of joint actions. Thus, the icon {©\"} denotes the communication of a child acting with an object with a loving adult who expressively accepts and evaluates the child as an actor and his unique manner of acting. It is clear that without such a layer of relations, a layer of proper object-business relationships oriented to patterns of objective actions.Other doubled icons are read similarly.0003

The main task of this scheme is to ensure such a completeness of the forms of jointness in the lesson, in which the entrance to learning activities will be open to children with a variety of personal orientations and values: not only to learners, but also to communicators, dreamers, practitioners, aesthetes . .. For this The lesson as a unit of the life of a younger student should be presented as a fusion of various forms of cooperation built by an adult with an accurate knowledge of its ingredients and their proportions.

.. For this The lesson as a unit of the life of a younger student should be presented as a fusion of various forms of cooperation built by an adult with an accurate knowledge of its ingredients and their proportions.

Scheme 2 serves as a tool for answering the question of what task the student is solving in the lesson, that is, the subject of what activity he is, when the teacher invites him to educational cooperation. It is extremely important to determine this, because far from always a child solves exactly the task that an adult sets before him. Thus, the teacher often offers the child a learning task aimed at finding a way to solve a new problem, and the child, imperceptibly for the teacher, replaces the learning task with a performing, playing or communicative one. The substitution of the subject of the educational task is determined only with the help of special diagnostic \"traps\". A directly observable behavioral criterion that makes it possible to determine what form of cooperation a child enters into is the method of proactively inviting a partner to communicate, derived from two other characteristics of cooperation that are irreducible to each other: 1) the method of interaction between partners, b) the system of mutual expectations of partners ( scheme 2, lines 2-4).

It has been experimentally established that the form and content of joint leading activity are noncoinciding factors of development [13], which makes it possible to separate two types of neoplasms (Scheme 2, lines 5-6). The functioning of neoplasms associated with the development of new objectivity ensures the success of individual activity. Neoplasms associated with mastering a new form of cooperation make a person capable of establishing certain relationships with other people and with himself. This scheme did not include new formations of self-consciousness, which most likely arise in crisis ages [9] and not coinciding with the identified two types of neoplasms of stable ages.

2. 1. Educational activity and direct-emotional communication

The brightest event of the first lessons in the 1st grade is not learning activity, but direct-emotional communication, which children tend to enter into with the teacher. The birth of educational cooperation begins in the same way as the birth of human communication: intense eye contact, the desire for bodily contact (to touch clothing, cuddle, caress), motor and vocal animation, a smile when a teacher appears - all these easily recognizable components of the infant "complex first graders, like all people in the world, use to involve a new and extremely significant adult in the activity from which the basic conditions of any other activity grow: emotional well-being, trust, openness. Children are usually extremely proactive in non-verbal expressions of kindness and attention to the teacher. If this is not observed, if it is not possible to establish eye contact with a child who has just sat down at a desk, if the child does not smile, avoids touching, then this serves as an alarming signal for the teacher and school psychologist of trouble precisely in the directly emotional sphere; with such a child, it is necessary to immediately establish, first of all, trusting, warm relations - and only after that to build educational cooperation.

The birth of educational cooperation begins in the same way as the birth of human communication: intense eye contact, the desire for bodily contact (to touch clothing, cuddle, caress), motor and vocal animation, a smile when a teacher appears - all these easily recognizable components of the infant "complex first graders, like all people in the world, use to involve a new and extremely significant adult in the activity from which the basic conditions of any other activity grow: emotional well-being, trust, openness. Children are usually extremely proactive in non-verbal expressions of kindness and attention to the teacher. If this is not observed, if it is not possible to establish eye contact with a child who has just sat down at a desk, if the child does not smile, avoids touching, then this serves as an alarming signal for the teacher and school psychologist of trouble precisely in the directly emotional sphere; with such a child, it is necessary to immediately establish, first of all, trusting, warm relations - and only after that to build educational cooperation.

Scheme 2 . The main characteristics of the leading forms of activity and their developing effects

| Leading characteristics: | Direct-emotional communication | Subject-manipulative activity | Play activities | Educational activities |

| 1. Contents | Another person and myself as a source of love, understanding, acceptance and appreciation | Ways of using human tools and signs | Social norms and meanings of human relations | General methods for solving classes of problems |

| 2. | Symbiotic Fusion | Literal imitation, pattern action | Conditional, imaginary, symbolic imitation | Finding a common course of action for partners in the absence of a sample |

| 3. The nature of the partner's initiative invitation to cooperate | Expressions of kindness (predominantly non-verbal) | “Show me how! Right? Good? It doesn’t work ... ”- Request for Sample, Control and Evaluation | "Come on as if ... You will ... And I will ... "- alternation of the game and inter-game communications about the ways of interaction | “I can solve this problem if. |

| 4. What a child expects from an adult partner | Presence, empathy, support, acceptance, appreciation | Sample demonstration, step-by-step help, control and evaluation | Building a shared vision and freedom to improvise within an agreement | Help in testing hypotheses expressed by the child, pointing out contradictions |

| 5. New formations arising from mastering content leading activities | Fundamental faith and hope, basic trust in people, in oneself and in the world | Speech, object actions | Imagination, symbolic function | Reflection |

| 6. | Need for another person, ability to trust people, openness to novelty | Ability to imitate | Ability to coordinate actions, taking into account the playing role of a partner | Ability (skill) to learn |

| 7. With the full formation of age-related neoplasms, the following is observed: | Trust in self and others, resilience to emotional stress, empathy | Ability to learn from samples and instructions | Ability to act in the mind, to create; social skills of cooperation with adults and peers | Knowing the limits of one's capabilities and the ability to overcome them: setting and solving problems of changing one's ZUNs |

| 8. | Inability to love and trust, lack of self-confidence, low self-esteem | Toollessness, difficulty in acquiring skills, disorganization | Poor fantasy, difficulty in dealing with unusual situations, social egocentrism | Lack of ability to learn, predominance of rational thinking |

| 9. With hypertrophy the development of age-related neoplasms is observed: | Dependence on emotional support and evaluation of other people, need for overprotection, loss of the object of cooperation, withdrawal into interpersonal communication | Need for instructions, lack of opinion, lack of criticality, performance attitudes, difficulty in sample analysis | Departure into fantasy, lack of a sense of reality, loss of focus on results, willfulness in goal setting | Disregard for the performing part of an action after finding a common way to carry it out, cognitive partiality |

| 10. | Trust in the teacher, the need to establish a relationship with him, self-confidence, openness to new experience | Ability and propensity to imitate the teacher's patterns, follow instructions and rules | Mastering the role of a student and the rules of life of a “real student”, readiness for an educational discussion | Youthful ability to learn independently |

The teacher will not be able to start building a new (learning) community with children without relying on children's gullibility and openness of communication, uncritical acceptance of an adult (with any curriculum) as a universal source of care, goodwill and protection in the new, unknown school world . For the teacher's business-like detachment, distance, emotional closeness, children pay with school anxiety. For the desire of some children to reduce all relationships in the classroom to direct-emotional relationships, the teacher pays with the loss of any objectivity of joint actions, except for the objectivity of direct-emotional communication: the evaluative side of the relationship "I am the other." Children who strive to reduce all communication to directly emotional revel in the personal attention of the teacher, consider praise and signs of sympathy addressed to them as the only content of the lesson, strive to prolong bodily contact with the teacher, keep him near them, and for this willingly and ingenuously demonstrate their helplessness and affection , tears and other emotional means achieve hyper-custody, intellectual "spoon-feeding".

For the teacher's business-like detachment, distance, emotional closeness, children pay with school anxiety. For the desire of some children to reduce all relationships in the classroom to direct-emotional relationships, the teacher pays with the loss of any objectivity of joint actions, except for the objectivity of direct-emotional communication: the evaluative side of the relationship "I am the other." Children who strive to reduce all communication to directly emotional revel in the personal attention of the teacher, consider praise and signs of sympathy addressed to them as the only content of the lesson, strive to prolong bodily contact with the teacher, keep him near them, and for this willingly and ingenuously demonstrate their helplessness and affection , tears and other emotional means achieve hyper-custody, intellectual "spoon-feeding".

These extreme cases only set off the norm: all children with a normally developed need for acceptance, emotional support and benevolence from the teacher strive to enter into direct emotional communication with him, in which any objectivity of joint action is dissolved, emasculated. Therefore, the teacher faces the most difficult task of maneuvering between the Scylla of non-objectivity and uncritical trust and the Charybdis of unemotionality and independence of judgment.

Therefore, the teacher faces the most difficult task of maneuvering between the Scylla of non-objectivity and uncritical trust and the Charybdis of unemotionality and independence of judgment.

Ways of building evaluative relationships in the classroom - this is the bridge through which the teacher transfers children who are primarily oriented towards relationships into learning activities. Against the background of an invariably benevolent attitude towards the personality of the student, the teacher teaches children the most differentiated business self-esteem. Let us give only one method of such training (see table). After each written work, the children evaluate it according to several criteria, for example, put crosses on the rulers in the middle column of the table.

Checking children's work, the teacher puts his grades on the same rulers, and the next day congratulates those children "who have already learned to evaluate themselves as a real teacher" and explains to the others the reasons for the discrepancy between the children's and the teacher's grades. For example, if a child rated himself too low, the teacher says: “You solved four examples for subtraction. Two, i.e. half , you decided correctly. That's why I put my cross exactly in the middle of the ruler. Your cross is much lower. You did a better job than you think. I ask you today, when evaluating your work, to be fair to yourself. "

For example, if a child rated himself too low, the teacher says: “You solved four examples for subtraction. Two, i.e. half , you decided correctly. That's why I put my cross exactly in the middle of the ruler. Your cross is much lower. You did a better job than you think. I ask you today, when evaluating your work, to be fair to yourself. "

Table 1.

| I'm sure I've solved everything addition examples correct | |------x-------| | I'm sure I solved all the addition problems WRONG |

| I am sure that I solved all subtraction problems correctly | |---------------x------| | I am sure that I solved all the subtraction problems WRONG |

| I wrote the work very beautifully | |--x-----| | I wrote the work very ugly |

Daily comparing their own assessment of their work with the teacher's and participating in the creation of assessment criteria, children learn objective assessment criteria and quite early stop mixing the global personal assessment of themselves as a worthy and beloved student, and a partial assessment that does not affect acceptance / rejection his skill in spelling, counting and other academic prowess. Distinguishing personal and business evaluation and mastering business self-esteem are the means to avoid confusion between the two types of cooperation - educational and direct-emotional.

Distinguishing personal and business evaluation and mastering business self-esteem are the means to avoid confusion between the two types of cooperation - educational and direct-emotional.

2. 2. Educational and object-manipulative activity

Educational activity is constantly mixed with object-manipulative activity leading in the development of children in the first three years of life [15], [17]. Even in early childhood, a child begins to learn from an adult various actions with tools and signs, the main feature of which is that "neither its social function nor the method of its rational use is written on the object" [15; 6]. A child is not able to discover a method of action with any human tool and sign without samples of action , which he masters only in joint action with an adult - the carrier of these samples. The method of object-manipulative cooperation between a child and an adult is imitation , or action according to a model. The formula for this type of cooperation is: "Do it with me, and now do it yourself, but is the same as I am ". Unlike a one-year-old child, a first grader is already capable of delayed imitation based on verbal instruction. A six-seven-year-old child is a virtuoso imitator, capable of reproducing the finest features of the sample, but not yet able to single out the essential in the sample - what needs to be imitated, and the non-essential - what can and should be done in his own way.

The formula for this type of cooperation is: "Do it with me, and now do it yourself, but is the same as I am ". Unlike a one-year-old child, a first grader is already capable of delayed imitation based on verbal instruction. A six-seven-year-old child is a virtuoso imitator, capable of reproducing the finest features of the sample, but not yet able to single out the essential in the sample - what needs to be imitated, and the non-essential - what can and should be done in his own way.

Such a global, undifferentiated, contextual reproduction of the teacher's models of action, and most importantly, the very tendency to imitate, gives rise to a special type of schoolchildren who are extremely diligent and diligent, act well according to the instructions, but get lost in the actual educational situation, when the teacher does not give any sample solutions new task, but encourages children to search for independent solutions, to make assumptions. Instead of acting in their own way, children with an exaggerated tendency to imitate begin to initiate the adult help that they need. They call the teacher and touchingly, childishly complain about their helplessness: “I can’t do it ... I don’t know what to do ... Show me how to solve ... " In other words, these children voluntarily refuse to independently search and ask an adult to give a ready-made sample or instruction, which they will willingly follow. The skills and abilities of such children are formed successfully, but each new task confuses them again and again. If this tendency to imitate is not overcome in the course of schooling, then the student will not develop the ability to learn - to independently set and solve new problems.

They call the teacher and touchingly, childishly complain about their helplessness: “I can’t do it ... I don’t know what to do ... Show me how to solve ... " In other words, these children voluntarily refuse to independently search and ask an adult to give a ready-made sample or instruction, which they will willingly follow. The skills and abilities of such children are formed successfully, but each new task confuses them again and again. If this tendency to imitate is not overcome in the course of schooling, then the student will not develop the ability to learn - to independently set and solve new problems.

The main means of overcoming reproductive tendencies and transferring children focused primarily on the implementation of rules, obedience and imitation into educational activities is the systematic organization of joint work of students, which takes place in relative independence from the adult - the bearer of samples [13]. At the same time, the optimal content of the joint educational work of children is unsolvable or underdetermined tasks. "Write the answer where possible. If you cannot solve the problem, ask me what will help you solve it. But each group has the right to ask me only one question," the teacher says to the first graders and offers them tasks of this type:

"Write the answer where possible. If you cannot solve the problem, ask me what will help you solve it. But each group has the right to ask me only one question," the teacher says to the first graders and offers them tasks of this type:

A = B A = B

C

___ ___

A? C A? C

"How to solve a second example?" - ask the teacher a child focused on reproductive action and asking for a role model. In the joint action of children, much more often than in individual action, a different kind of appeal to the teacher arises: "Is B more than C or less?" - for the sake of this question, all the work was started. When the student is able to ask the teacher for the missing data, he has taken the first step towards the ability to separate the known from the unknown and formulate a question regarding the unknown. Such a request for missing knowledge is strikingly different from the complaint of a child-imitator, indicating to an adult the limits of his abilities: "I myself (a) cannot. Show me what to do!" Now the child communicates to the teacher a much more optimistic and independent thought, which contains not only an indication of the limit of the child's possibilities, but also an assumption about what is beyond this limit - the hypothesis of the unknown: "I will succeed if I find out something and so-and-so."

Show me what to do!" Now the child communicates to the teacher a much more optimistic and independent thought, which contains not only an indication of the limit of the child's possibilities, but also an assumption about what is beyond this limit - the hypothesis of the unknown: "I will succeed if I find out something and so-and-so."

2. 3. Educational and play activities