Letter name and sound

When to Teach Letter Names

by Shirley Houston

I recently received an email posing this question:

We are teaching systematic phonics to our little ones, but we are conflicted as when to teach letter names. When and how should letter names be taught to children?”

The timing of the introduction of letter names is important, so I’ll frame my thoughts using the Goldilocks principle – not too early, not too late, but at just the right time. It is a developmental concern, rather than a grade/year- or age-related concern.

Not Too Early

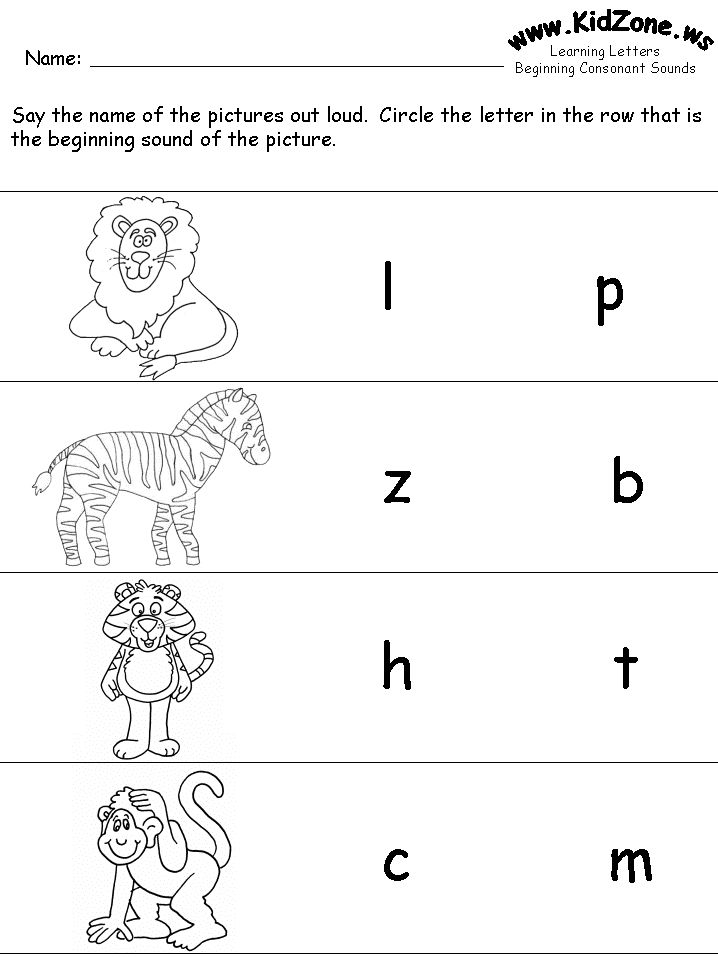

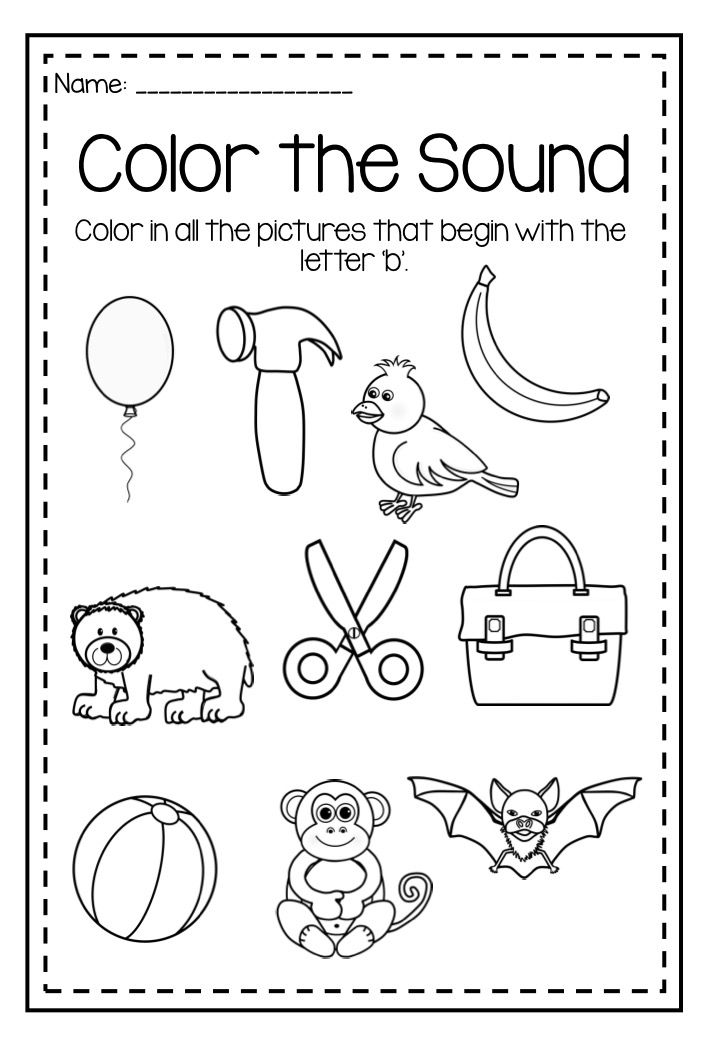

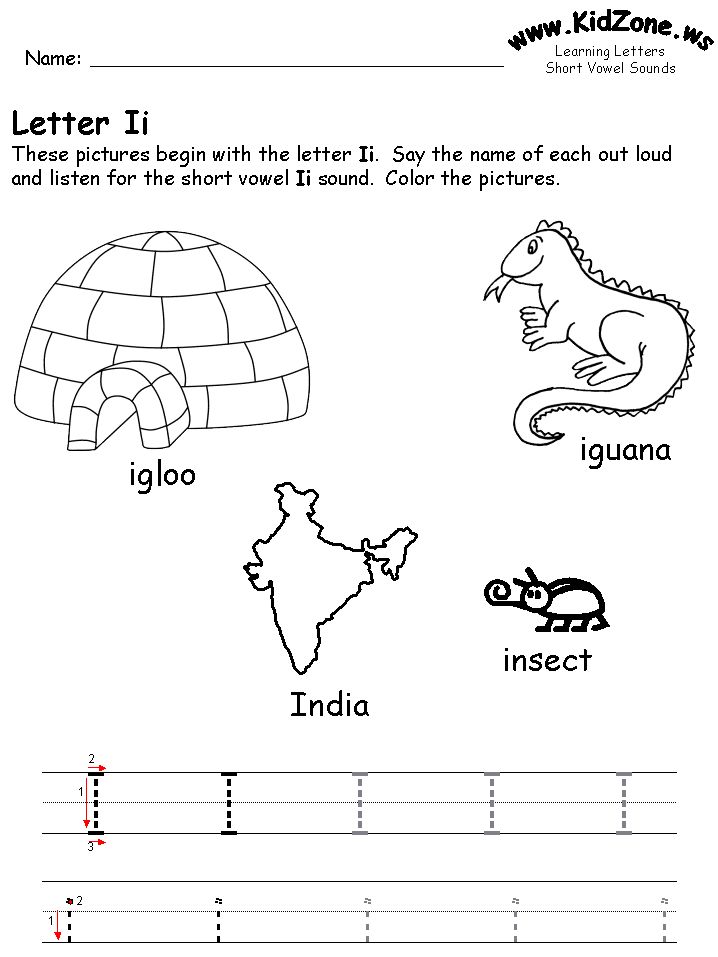

Should you teach letter names or sounds first?

Letters are used as a code for the sounds in our speech so are meaningless without knowledge of the sounds. Any squiggle/shape could represent a sound, for example:

Letter names provide abstract labels for the letters, not representations of how the letters actually sound within our language. That is why teaching a child to sing the alphabet song before the child receives formal reading instruction has limited value. The first important step towards literacy success is development of phonemic awareness and not letter name singing.

Why not teach letter names and sounds together?

So, if letters make no sense without sounds, why not teach letter sounds and names side by side? The simple answer is because of the cognitive load. Working memory has to work hardest when a task is novel and therefore has a heavy cognitive load. For the beginning learner, identifying individual sounds in a word, from left to right, is quite a novel task. Forming letter shapes and discriminating between letter shapes are novel tasks. Remembering the name of a letter is a novel task. Linking a specific letter with a specific sound is a novel task.

Is it any wonder that some children, especially those with a weak working memory, struggle with reading and spelling? Cognitive load theory makes it clear that we can and should do what is necessary to reduce cognitive load. It is not necessary for school beginners to know the names of letters for reading and spelling, so, in my opinion, the teaching of letter names should be postponed until letter names are necessary. This allows students to begin to write and read more quickly.

It is not necessary for school beginners to know the names of letters for reading and spelling, so, in my opinion, the teaching of letter names should be postponed until letter names are necessary. This allows students to begin to write and read more quickly.

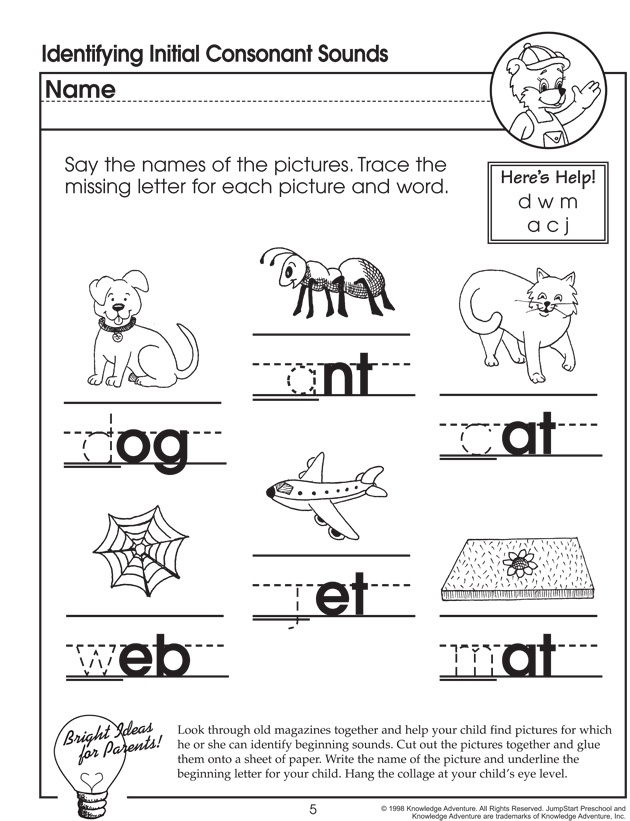

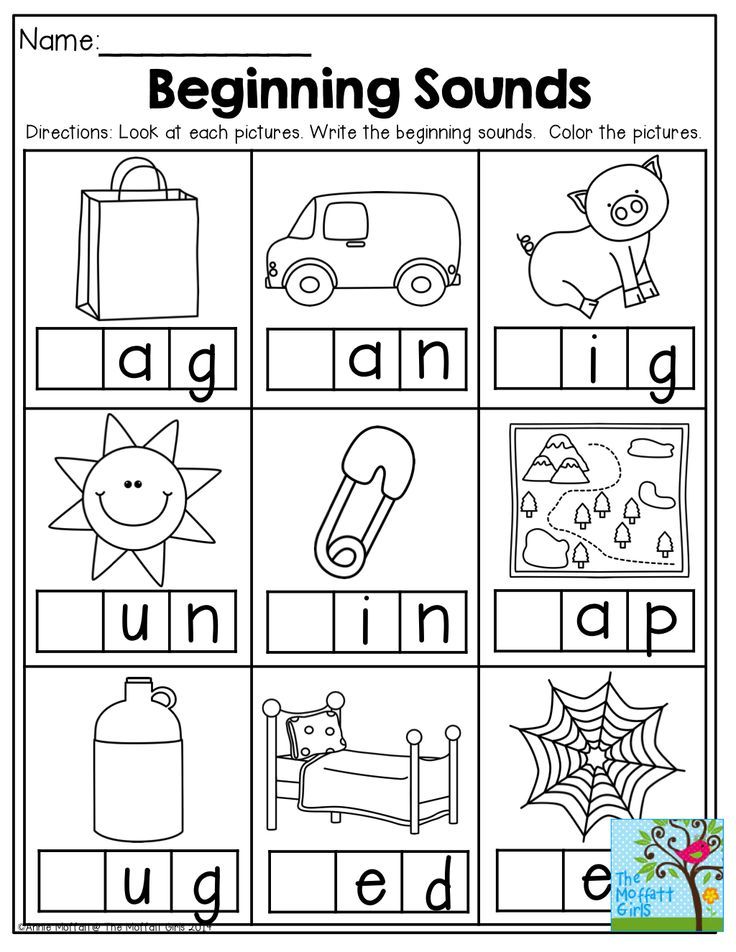

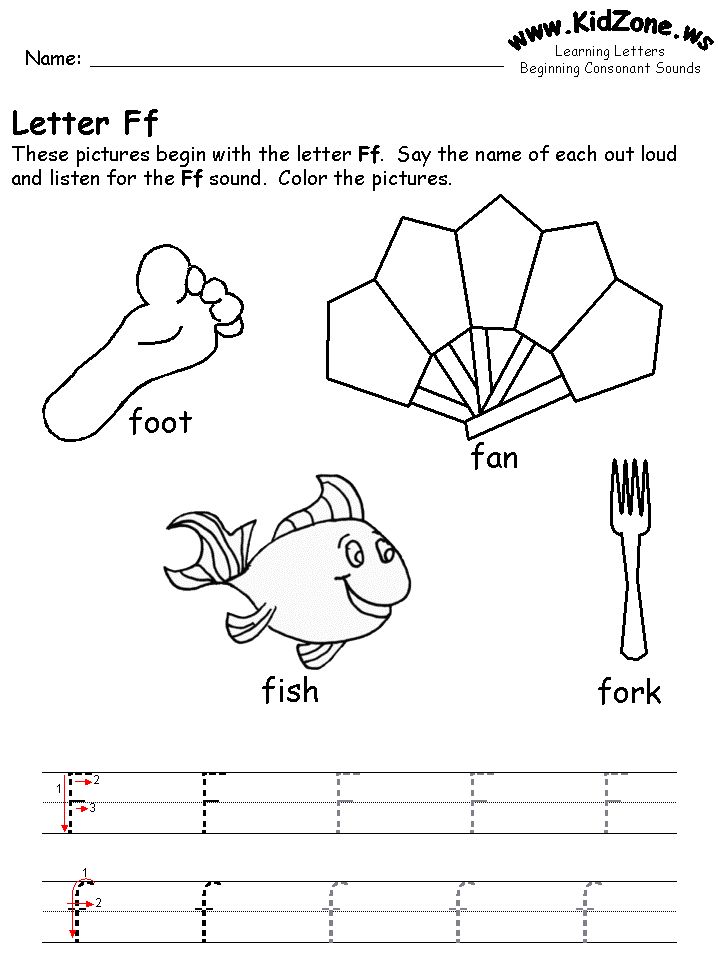

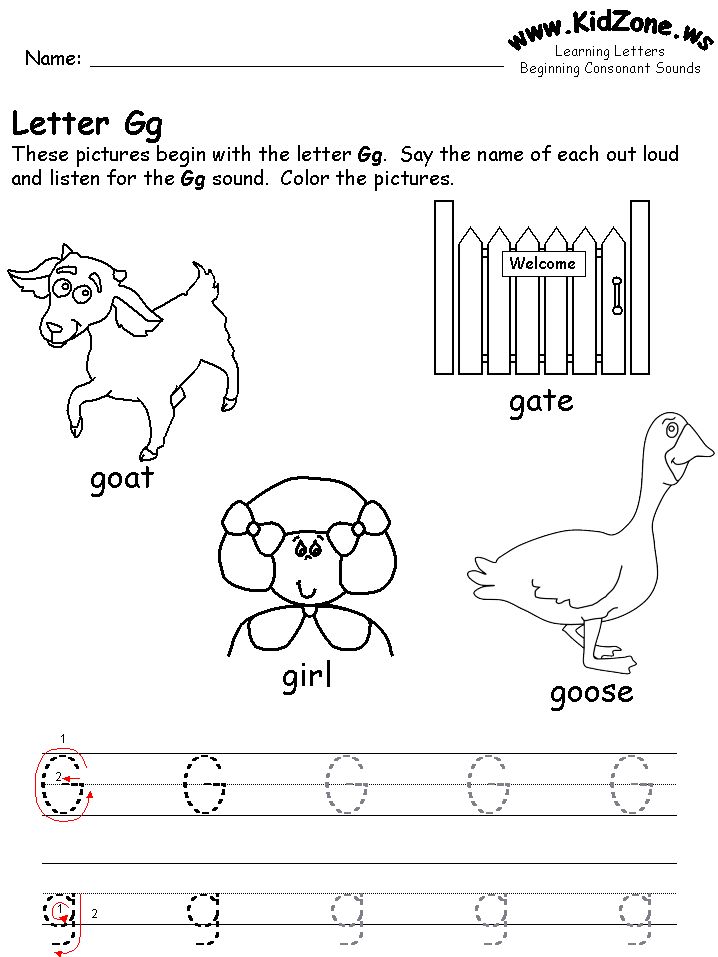

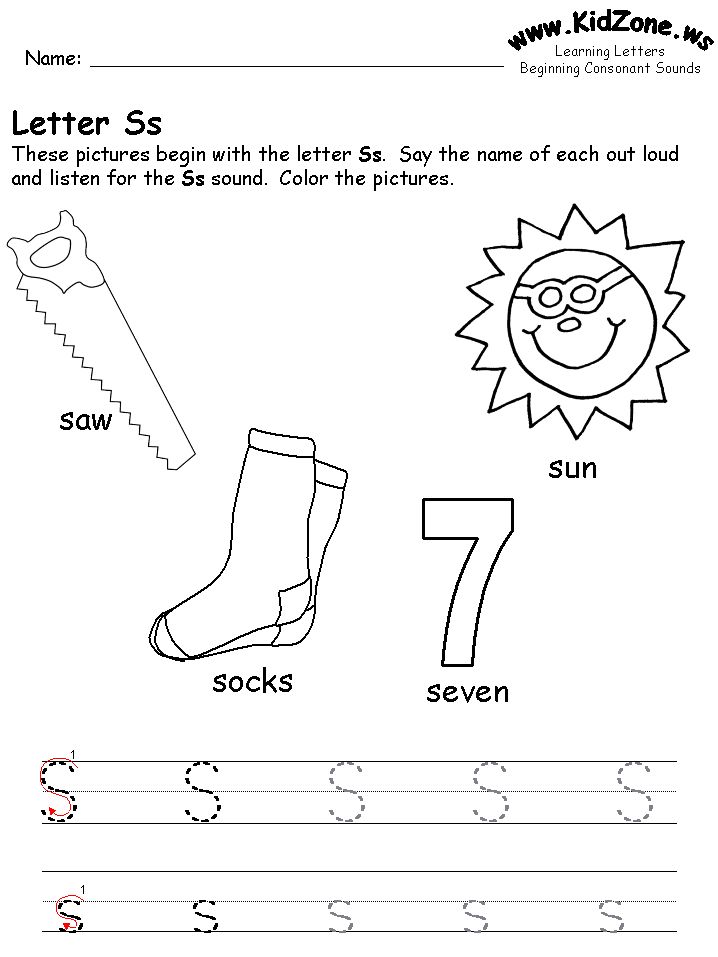

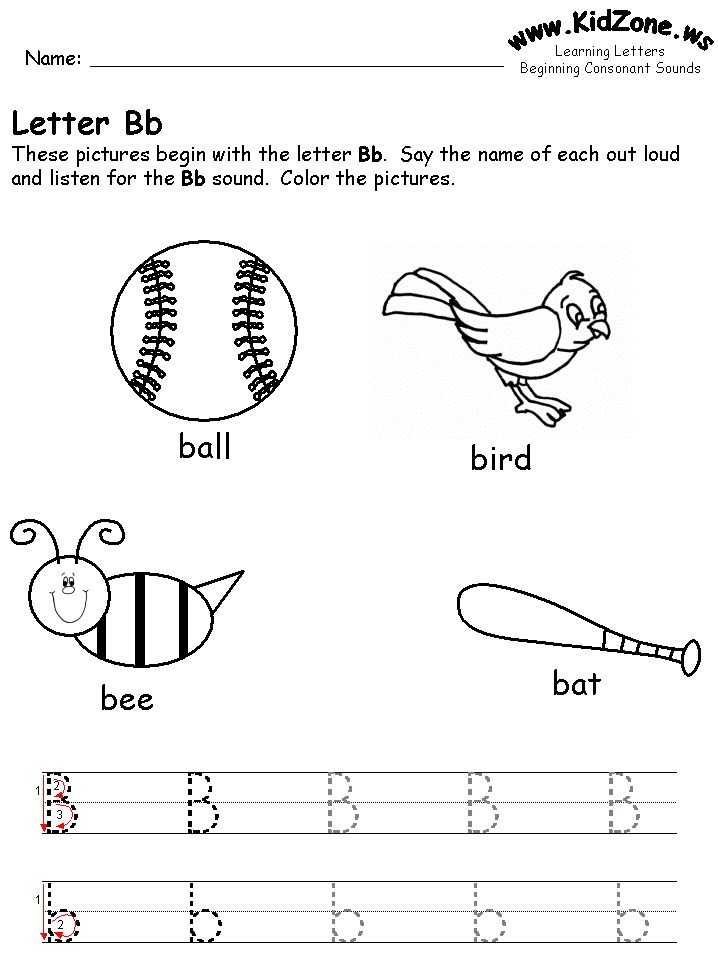

Teach letter-sound correspondences initially, without teaching letter names

Students need to learn letter-sound correspondences for reading and spelling. When a beginning reader is learning the single letter-sound correspondences, you do have to talk about the squiggles we make for sound symbols as ‘letters’, but that does not mean that you should refer to the letter names. Instead, the teacher can say:

or

When the child is spelling, the prompt can be:

Teaching letter names too early can confuse beginning readers

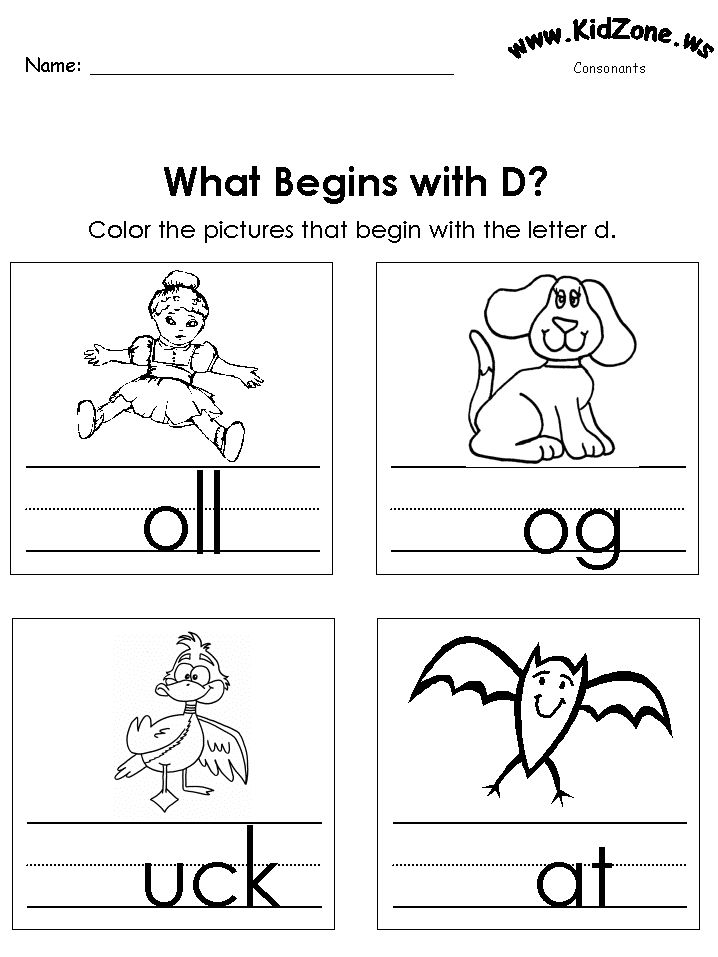

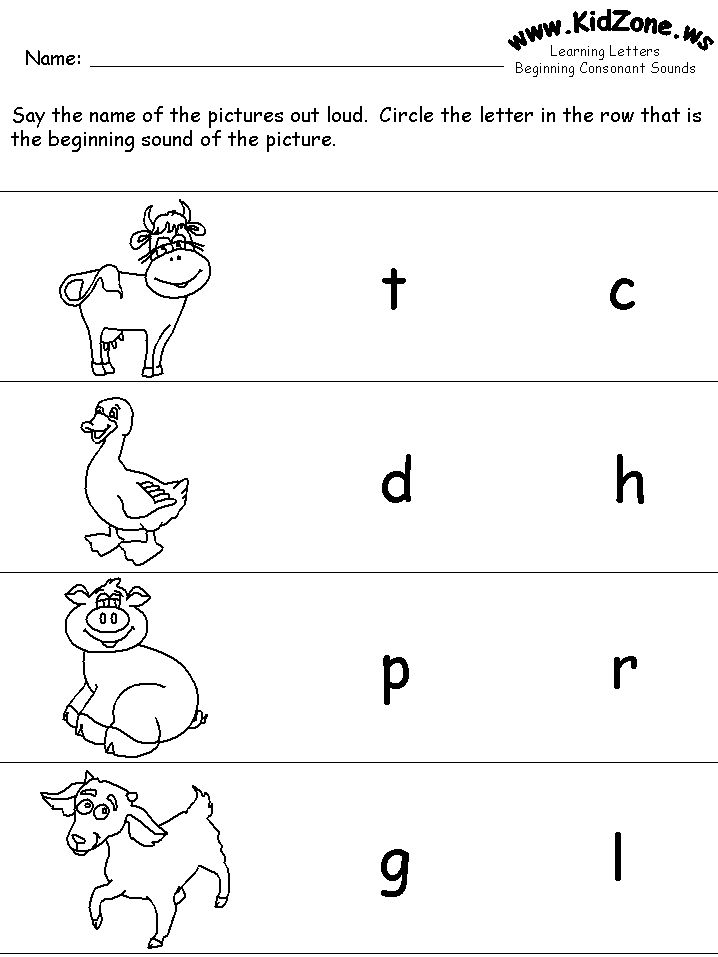

Letter names will not help a child to decode words: the word ‘cat’ is not read as ‘seeaytee’. While some may argue that teachers can use aspects of letter names as cues for students to identify the sounds they represent, the potential for confusion outweighs any benefits if letter names are introduced too early.

Children learning to read who have received more instruction in letter names than letter sounds are more likely to look at a word and read:

| ‘w’ | /d/ (for ‘doubleyou’) – refers to the shape of the letter, not the sound |

| ‘y’ | /w/ (for ‘why’) |

| ‘u’ | /y/ (for ‘you’) |

| ‘c’ | /s/ (for ‘see’) – this is less common than /k/ |

| ‘g’ | /j/ (for ‘jee’) – this is less common than hard /g/ |

| ‘h’ | long /a/ (as in ‘a itch’) |

| ‘f’, ‘l’, ‘m’, ‘n’, ‘s’, ‘x’ | short /e/ (as in ‘ef’, ‘el’, ‘em’, ‘en’, ‘es’, ‘ex’) |

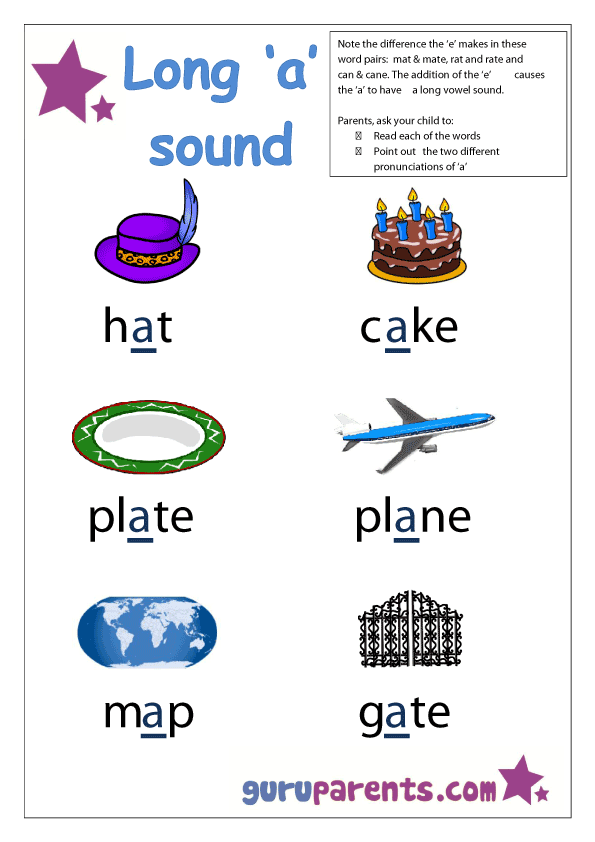

If they are taught letter names before letter sounds, beginning readers will expect vowel letters to represent a long vowel sound in words, reading, for example, ‘got’ as ‘goat’. The most common sound represented by a vowel letter is its short sound, and it is usually VC and CVC words, containing short vowel sounds, to which beginning readers are first exposed.

The most common sound represented by a vowel letter is its short sound, and it is usually VC and CVC words, containing short vowel sounds, to which beginning readers are first exposed.

…and beginning spellers

Children learning to spell who have received more instruction in letter names than letter sounds are more likely to use letter names in their spelling e.g.

Not Too Late

It will be harder for a teacher to help children who have not been taught letter names with their spelling. In the photo below, you can see what a five-year-old, who doesn’t know the letter names, produced when she asked how to spell ‘bean’ and the parent responded with letter names:

If a child asks how to spell the long /ee/ sound in ‘beach’, it is not appropriate to say “Write /eh/ then /ah/”, because blending those sounds together does not create the long /ee/ sound. You must use letter names e. g. “We spell the long /ee/ sound in ‘beach’ with the letter ‘e’ followed by the letter ‘a’. They make a

vowel team.” Similarly, if you ask a child how ‘seek’ is spelled, it is not sufficient for the child to say “/s/, long /ee/, /k/” because there are several possible spellings for each of those sounds. Developing the language that allows discussion of letter-sound correspondences is important to reading and spelling success.

g. “We spell the long /ee/ sound in ‘beach’ with the letter ‘e’ followed by the letter ‘a’. They make a

vowel team.” Similarly, if you ask a child how ‘seek’ is spelled, it is not sufficient for the child to say “/s/, long /ee/, /k/” because there are several possible spellings for each of those sounds. Developing the language that allows discussion of letter-sound correspondences is important to reading and spelling success.

When you are helping a child to encode or decode an irregular tricky word, you need to be able to draw attention to the parts that are not regular, for example by saying “The letters ‘a’ and ‘i’ together in this word, ‘said’, are representing the short /e/ sound.” Irregular words cannot be fully sounded out so knowledge of letter-sound correspondences is insufficient.

Just the Right Time

Research indicates that letter name instruction will actually strengthen letter sound knowledge. When a student understands the way in which the alphabetic code works, letter names become important. Many letters have more than one possible sound, and many sounds can be produced by a variety of different letters, so it is important to be able to reference each letter independently of the sound it makes.

Many letters have more than one possible sound, and many sounds can be produced by a variety of different letters, so it is important to be able to reference each letter independently of the sound it makes.

Teach letter names when they are needed:

To talk about alternative spellings

e.g.

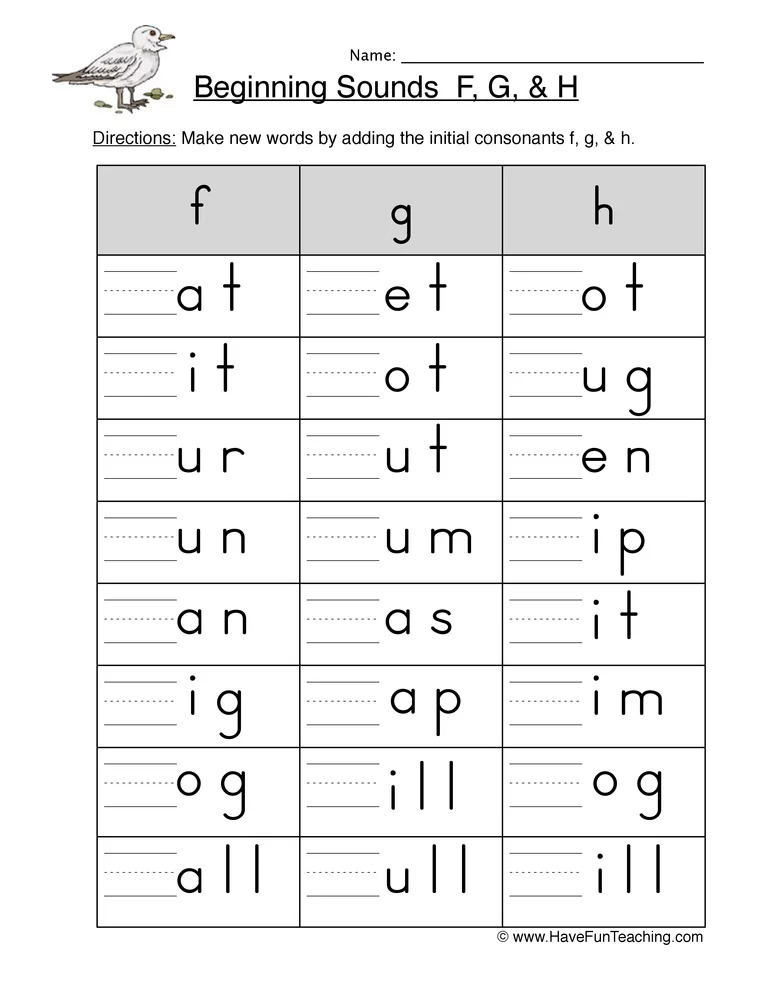

Teach letter names as soon as you need to talk about alternate spellings in reading and/or spelling. Typically, the first time you need to do this will be when students learn that ‘c’, ‘k’ and ‘ck’ are all alternatives for spelling /k/. You will need to talk about where children will see these alternatives:“We usually see the letter ‘k’ representing /k/ before an ‘e’ or ‘i’ at the beginning of a word.”

“The letter ’c’ usually represents /k/ before an ‘a’, ‘o’ or ‘u’.”

“We use the letters ‘c’ and ‘k’ together after a weak vowel at the end of a word.”

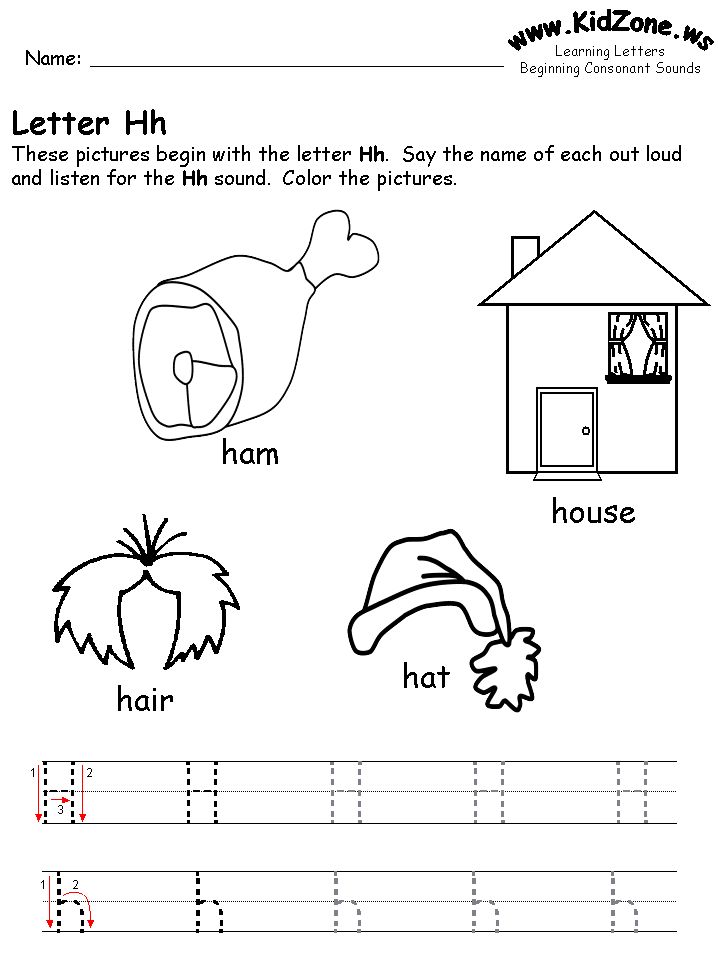

Letter names must be taught for discussion of digraphs e.

g. “Because we have 44 sounds but only 26 letters in English, we have to combine some letters. The two-letter combination of ‘c’ and ‘h’ represents the sound /ch/.” When the alternative spellings of long /ee/ are taught (ea, ee, ie, ei, ey) it is no longer sufficient to just refer to ‘two-letter e’ – you must name the vowels that can be combined to represent a vowel sound, and their order.

g. “Because we have 44 sounds but only 26 letters in English, we have to combine some letters. The two-letter combination of ‘c’ and ‘h’ represents the sound /ch/.” When the alternative spellings of long /ee/ are taught (ea, ee, ie, ei, ey) it is no longer sufficient to just refer to ‘two-letter e’ – you must name the vowels that can be combined to represent a vowel sound, and their order.To talk about capital letters

If you are teaching students about the use of a capital letter at the beginning of a sentence or name, you must refer to a letter name. There is no such thing as a capital sound! You will also need to refer to letter names when helping children to recognise letters when reading text in different fonts.To communicate the spelling of a word to someone else

Familiarity with letter names allows the teacher to respond, from a distance, to the question “How do I spell the /ie/ in ‘night’?” with “It’s the i-g-h spelling”, rather than having to go and write it down for the child. When someone asks you to spell your name, do you give him/her the sounds of your name or do you provide the letter names? Of course, you give the latter. Not to do so would require the person to go through every alternative representations of the sounds and make a choice. That could take a lot of time if your name was derived from another alphabet, like ‘Siobhan’! Consequently, a teacher may have to teach specific letter names earlier to a child with a name that cannot be sounded out easily or has an unusual spelling.

When someone asks you to spell your name, do you give him/her the sounds of your name or do you provide the letter names? Of course, you give the latter. Not to do so would require the person to go through every alternative representations of the sounds and make a choice. That could take a lot of time if your name was derived from another alphabet, like ‘Siobhan’! Consequently, a teacher may have to teach specific letter names earlier to a child with a name that cannot be sounded out easily or has an unusual spelling.To teach homophones

When the sounds of two words are the same, you must be able to describe them using their letter names. e.g. “The ‘bean’ you eat is spelled with the letters ‘e’ and ‘a’, as in the word ‘eat’. The other ‘been’ is the past tense of ‘be’ and is spelled with two e’s.”

How Do You Teach Letter Names?

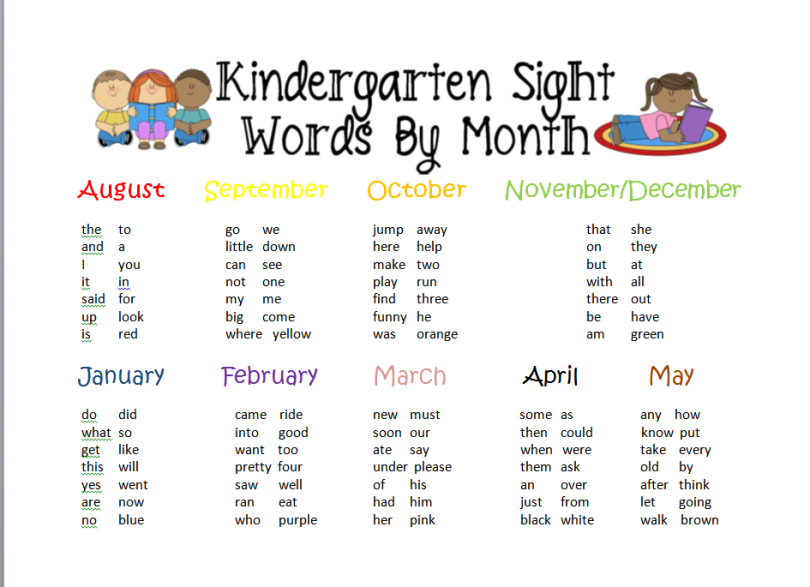

Follow the order of your synthetic phonics program in choosing which letter names to teach, when. Using our earlier example, the c/k/ck alternative spellings of /k/ are the first typically met in a synthetic phonics program (in level 6 of Phonics Hero’s Playing with Sounds order and level 2A of Letters and Sounds, so these should probably be taught first, then the letters that make up consonant digraphs (l, s, f, h, t, w, n and g).

Using our earlier example, the c/k/ck alternative spellings of /k/ are the first typically met in a synthetic phonics program (in level 6 of Phonics Hero’s Playing with Sounds order and level 2A of Letters and Sounds, so these should probably be taught first, then the letters that make up consonant digraphs (l, s, f, h, t, w, n and g).

Teach the most common letter names first, the less common letter names last (q, z, x.). Every syllable of every word must have a vowel sound and there are many alternative spellings of vowel sounds, so it is very important that students have a sound knowledge of these.

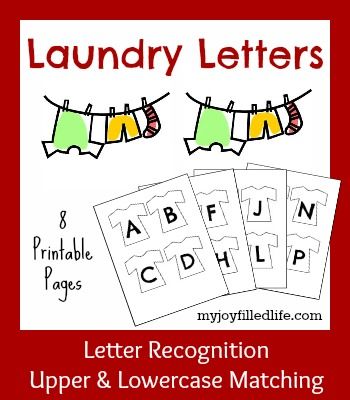

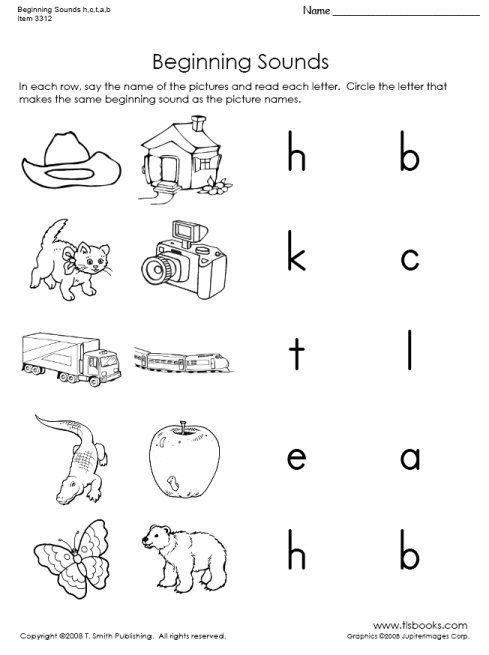

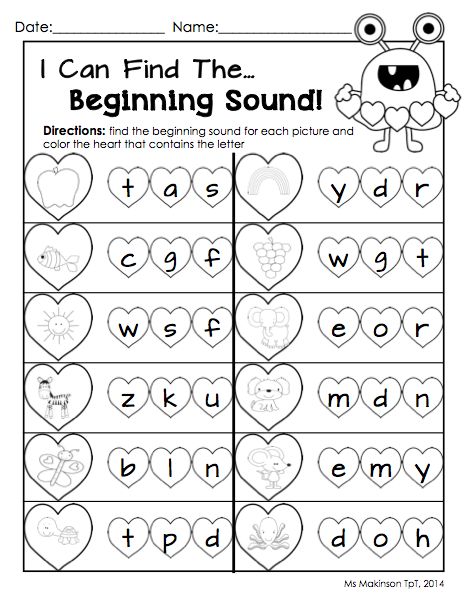

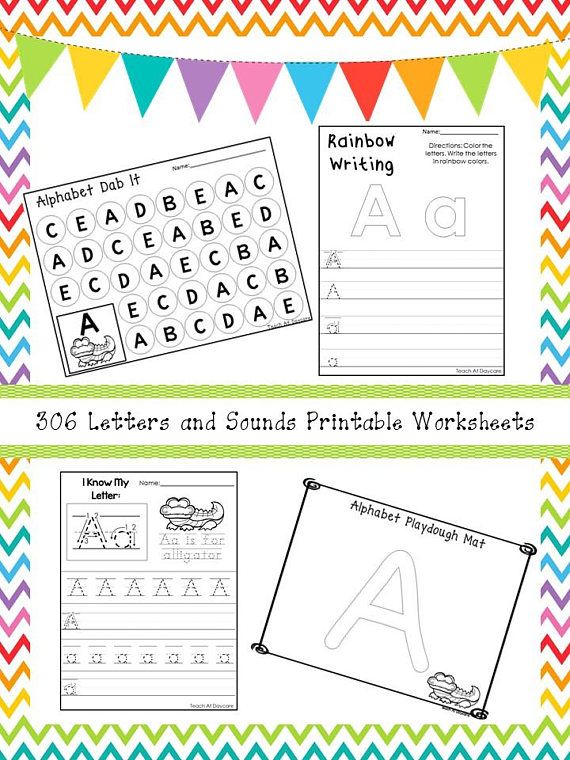

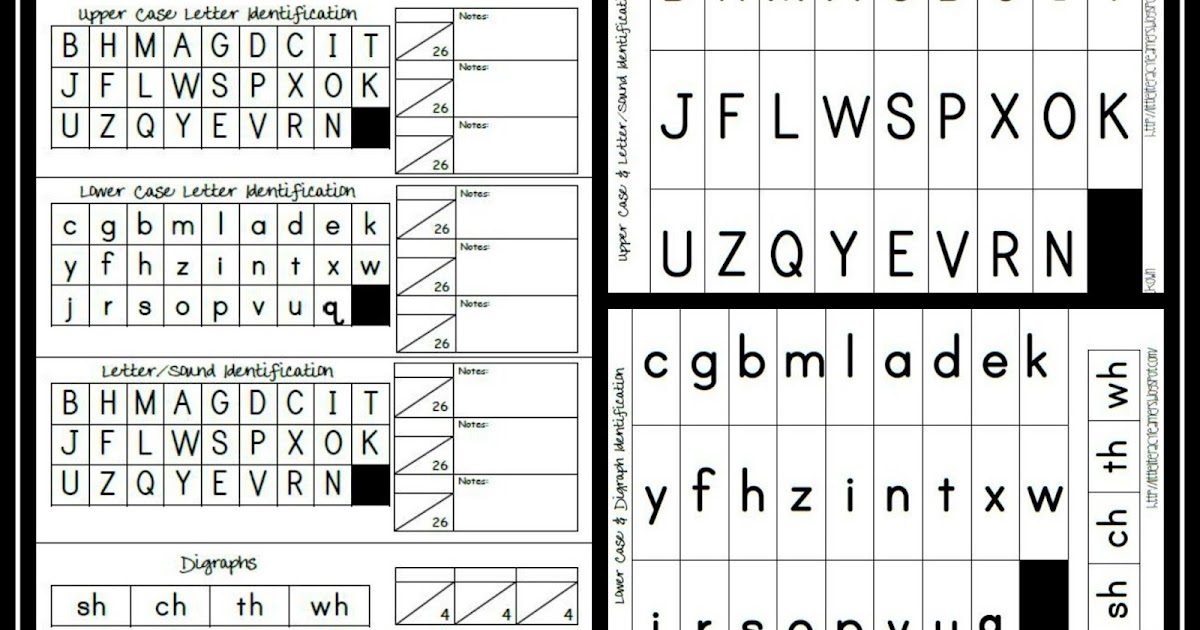

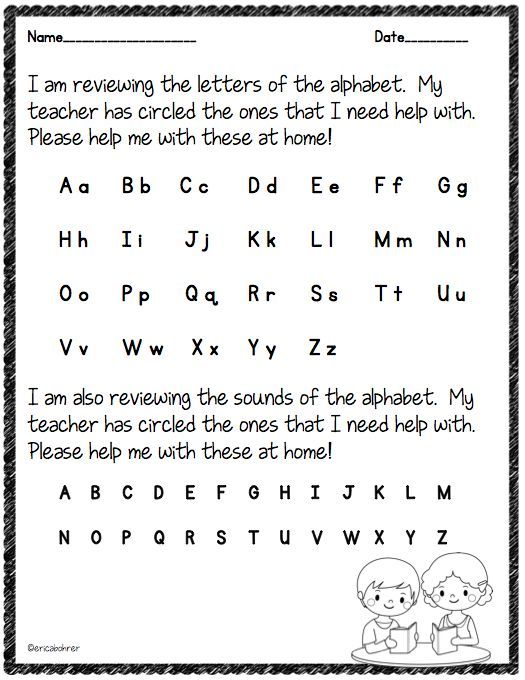

In order to have true fluency in letter recognition, children must be able to identify letters and say their names in and outside of context and in and out of sequence. It’s not just accuracy, but also automaticity, that contributes to long-term literacy success. Here are a few ideas for developing automaticity in letter naming:

- Direct instruction: “This letter’s name is __.

What letter is it? Point to another ___ on the board.”

What letter is it? Point to another ___ on the board.” - Teach letter names alongside letter formation. Have the child say the name of the letter as he or she writes it.

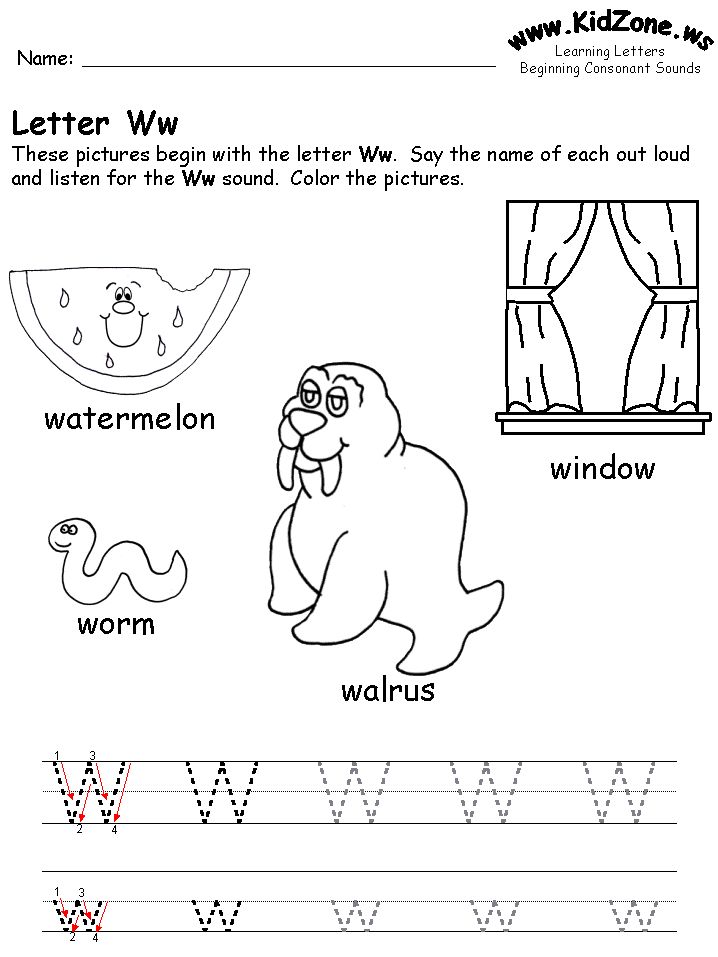

Have a letter of the day and reward the child for finding that letter in the classroom, in a shared book, etc. Print our free Letter of the Day poster and use it to display the letter at the front of your classroom.

Letter searches: “Circle each letter ‘p’ in this line of letters.”

- Bingo: Call out a letter name and have the child place a counter on the corresponding letter. We’ve created a free Letter Name Bingo template you can use.

- Have the student pull a letter out of a mystery bag, a sandbox etc and name it.

- Use the child’s name and other family names to practise letter recognition.

- Print out letters on paper or write them with chalk. Have children jump on/run to a letter when you call out a letter name.

Once the student can accurately name all 26 letters, return your focus to letter-sound correspondences. There are many more sounds than letters to learn and knowledge of those correspondences are key to reading and spelling successfully!

Still have questions about how or when to teach letter names to children? Leave us a comment below!

Author: Shirley Houston

With a Masters degree in Special Education, Shirley has been teaching children and training teachers in Australia for over 30 years. Working with children with learning difficulties, Shirley champions the importance of teaching phonics systematically and to mastery in mainstream classrooms. If you are interested in Shirley’s help as a literacy trainer for your school, drop the team an email on [email protected]Letter Names or Sounds First?

Teacher question:

I teach kindergarten. We are trying to follow the science of reading. We believe that is the best way to go. However, my colleague and I are disagreeing over one aspect of our program. Should we teach the letters first, the sounds first, or should we teach them together?

However, my colleague and I are disagreeing over one aspect of our program. Should we teach the letters first, the sounds first, or should we teach them together?

Shanahan response:

This is such a practical question and often research fails to answer such questions. That shouldn’t be too surprising since researchers approach reading a bit differently than the classroom teacher. A good deal of psychological study of letters and words over the past century hasn’t been so much about how best to teach reading as much as an effort to understand how the human mind works.

In this case, there is a research record that at least provides some important clues as to what the best approach may be.

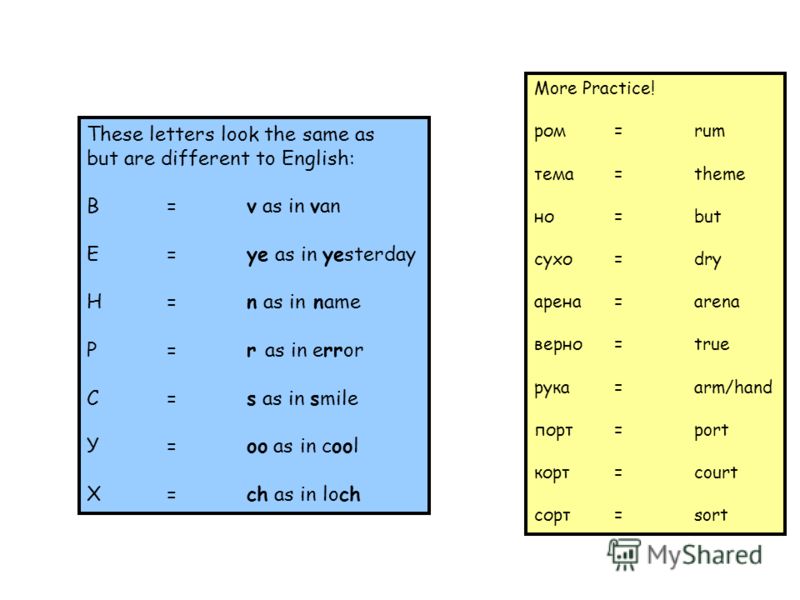

There has been some disagreement over whether it is a good idea to teach letter names at all. Back in the 1970s, S.J. Samuels conducted some small studies with an artificial orthography and found that the “letter” names were neither necessary nor useful for college students learning to read this new spelling system. Later, Diane McGuiness (2004) in her popular book argued against teaching letter names because they can be a hindrance in some situations. An example of this were my first graders who figured that “what” must begin with the /d/ sound (using the name of the letter “w” as a clue to its sound, an approach that works often but not always).

Later, Diane McGuiness (2004) in her popular book argued against teaching letter names because they can be a hindrance in some situations. An example of this were my first graders who figured that “what” must begin with the /d/ sound (using the name of the letter “w” as a clue to its sound, an approach that works often but not always).

Nevertheless, newer and more relevant research has shown that letter names may play an important role in early literacy learning. Those confusions do occur, but more often the letter names facilitate the learning of letter sounds – because the names and sounds are usually in better agreement than in the confusing instances (Treiman, et al., 2008; Venezky, 1975) and letter names seem to be more effective than sounds in supporting learning early in the progression (Share, 2004; Treiman, 2001). One instructional study with preschoolers found that teaching letter names together with letter sounds led to improved letter sound learning when compared to just teaching the sounds alone (Piasta, Purpura, & Wagner, 2010) – and this benefit was clearly due to the combination and not to any differences in print exposure, instructional time or intensity. Another study (Kim, Petscher, Foorman, & Zhou, 2010) found that letter name knowledge had a larger impact on letter-sound acquisition than the reverse, and that phonological awareness had a larger impact on letter sound learning when letter names were already known.

Another study (Kim, Petscher, Foorman, & Zhou, 2010) found that letter name knowledge had a larger impact on letter-sound acquisition than the reverse, and that phonological awareness had a larger impact on letter sound learning when letter names were already known.

That learning advantage may be something specifically American, however. In the U.S., children tend to learn letter names quite early – look at the number of toys that emphasize this knowledge (type “letter name toys for infants” into Google and you get more than 8 million hits) or the Head Start curriculum. Old fashioned toys like wooden blocks emphasize letter naming, as do the latest technological gadgets. That means that many kids start school knowing at least some of the letter names and that knowledge may be the reason why letters do more to help sound learning, rather than the opposite.

One cool natural experiment compared children in the U.S. with those in England, where letter names are introduced later than letter sounds. There, the kids use their knowledge of sounds to help in the mastery of the letter names (Ellefson, Treiman, & Kessler, 2009). Essentially, the researchers figured that learning that first list of letters or sounds is just arbitrary memorization. Then, when the kids try to learn the second list, they use what they already know to make the task go easier. If I know my letter names, and they give me a clue that will help me learn the sounds, then I do that. On the other hand, if I already have mastered the sounds, then they may be used to facilitate my learning of the letter names.

There, the kids use their knowledge of sounds to help in the mastery of the letter names (Ellefson, Treiman, & Kessler, 2009). Essentially, the researchers figured that learning that first list of letters or sounds is just arbitrary memorization. Then, when the kids try to learn the second list, they use what they already know to make the task go easier. If I know my letter names, and they give me a clue that will help me learn the sounds, then I do that. On the other hand, if I already have mastered the sounds, then they may be used to facilitate my learning of the letter names.

If English was more like Finnish, with everyone pronouncing the language pretty consistently, and a written symbol for every phoneme in the language, I would conclude from all of this that we only need to teach letter sounds. English is more complicated than that both in terms of the range of dialects and the conditionality of the spellings – particular sounds are often represented by multiple letters (think of the letter “s” in sick, sure, ship, and use). Having a name for the letter separate from the mélange of sounds that it will represent is helpful – it provides some stability to work with. Even in England, by the time kids are taking on English spelling in its full complexity, letter names will usually have been learned. (It should also be pointed out that consistent letter names also provide a useful consistent anchor for the visual forms of the letters as well:

Having a name for the letter separate from the mélange of sounds that it will represent is helpful – it provides some stability to work with. Even in England, by the time kids are taking on English spelling in its full complexity, letter names will usually have been learned. (It should also be pointed out that consistent letter names also provide a useful consistent anchor for the visual forms of the letters as well:

In the U.S., given that many children come to school knowing at least some letter names, it makes the greatest sense to start right there. The studies show that letters are a better base for sound learning in American schools, but they don’t reveal whether this sequence is superior to a combined approach, teaching letters and sounds simultaneously. None of the studies compared this.

My sense of this as a teacher? If kids come to school knowing a bunch of letter names – at whatever age, I would turn my focus to the letter sounds – that available letter name knowledge will be a boon. On the other hand, if they know few letters when we start, I might vary my approach a bit… with the preschoolers I’d focus more on the letter names for a while, and not sweat the sounds. While in kindergarten and grade 1, I’d try to teach names and sounds together. I think there’d be less chance that I’d confuse those kids with a combined approach – their attention spans are a bit longer. I expect that I’ll hear from preschool teachers telling of their success in teaching letters and sounds in combination, and K-1 teachers of their one skill at a time triumphs… but that just means it probably won’t matter much, one way or the other, if you can make your approach work efficiently.

On the other hand, if they know few letters when we start, I might vary my approach a bit… with the preschoolers I’d focus more on the letter names for a while, and not sweat the sounds. While in kindergarten and grade 1, I’d try to teach names and sounds together. I think there’d be less chance that I’d confuse those kids with a combined approach – their attention spans are a bit longer. I expect that I’ll hear from preschool teachers telling of their success in teaching letters and sounds in combination, and K-1 teachers of their one skill at a time triumphs… but that just means it probably won’t matter much, one way or the other, if you can make your approach work efficiently.

I definitely wouldn’t start with the sounds first, though that doesn’t seem to be a problem in the U.K. I think of the unifying value of letter names as being foundational knowledge, so I feel more comfortable starting there. That approach, however, is an opinion rather than a data-based, science of reading claim. That opinion is drawn from my experiences in teaching children and in my estimation of my own pedagogical skills (those with greater skills may be able to succeed with less likely bets).

That opinion is drawn from my experiences in teaching children and in my estimation of my own pedagogical skills (those with greater skills may be able to succeed with less likely bets).

Finally, I’d add something you didn’t ask about. When teaching the letter names or sounds I’d teach students to print the letters. There is no reason to leave printing out of this equation – this added demand requires students to look at the letters more thoroughly, gaining purchase on their distinguishing features and it may increase the chances of the letters and sounds ending up in long term memory. Kids are hands on… they like to stack blocks, fingerpaint, decorate Christmas cookies, sit in water (don’t ask), and put their hands in stuff I don’t even want to think about… they like to mark on paper too, and getting them physically involved in literacy is not a bad thing. Letters then sounds, or letters and sounds together, but writing included with either approach. To me, that’s the winning hand.

References

Ellefson, M. R., Treiman, R., & Kessler, B. (2009). Learning to label letters by sounds or names: A comparison of england and the united states. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102(3), 323-341. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.jecp.2008.05.008

Piasta, S. B., Purpura, D. J., & Wagner, R. K. (2010). Fostering alphabet knowledge development: A comparison of two instructional approaches. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 23(6), 607-626. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1007/s11145-009-9174-x

Share, D. L. (2004). Knowing letter names and learning letter sounds: A causal connection. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88(3), 213-233. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.jecp.2004.03.005

Treiman, R., Pennington, B. F., Shriberg, L. D., & Boada, R. (2008). Which children benefit from letter names in learning letter sounds? Cognition, 106(3), 1322-1338. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.06.006

doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.06.006

Treiman, R., Sotak, L., & Bowman, M. (2001). The roles of letter names and letter sounds in connecting print and speech. Memory & Cognition, 29(6), 860-873. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.3758/BF03196415

Venezky, R.L. (1975). The curious role of letter names in reading instruction. Visible Language, 9, 7-23.

Sounds and letters of the Russian language - scheme, table, transcription

Contents:

• What is sound?

• What sounds are there?

• How are sounds pronounced?

• Transcription of the word

• Color scheme

Sounds belong to the phonetics section. The study of sounds is included in any school curriculum in the Russian language. Acquaintance with sounds and their main characteristics occurs in the lower grades. A more detailed study of sounds with complex examples and nuances takes place in middle and high school. This page provides only basic knowledge of the sounds of the Russian language in a compressed form. If you need to study the device of the speech apparatus, the tonality of sounds, articulation, acoustic components and other aspects that are beyond the scope of the modern school curriculum, refer to specialized textbooks and textbooks on phonetics.

If you need to study the device of the speech apparatus, the tonality of sounds, articulation, acoustic components and other aspects that are beyond the scope of the modern school curriculum, refer to specialized textbooks and textbooks on phonetics.

What is sound?

Sound, like words and sentences, is the basic unit of language. However, the sound does not express any meaning, but reflects the sound of the word. Thanks to this, we distinguish words from each other. Words differ in the number of sounds (port - sport, crow - funnel), set of sounds (lemon - estuary, cat - mouse), sequence of sounds (nose - dream, bush - knock) up to a complete mismatch of sounds (boat - boat, forest - park ).

What sounds are there?

In Russian, sounds are divided into vowels and consonants. There are 33 letters and 42 sounds in Russian: 6 vowels, 36 consonants, 2 letters (ь, ъ) do not indicate a sound. The discrepancy in the number of letters and sounds (not counting b and b) is due to the fact that there are 6 sounds for 10 vowels, 36 sounds for 21 consonants (if we take into account all combinations of consonant sounds deaf / voiced, soft / hard). On the letter, the sound is indicated in square brackets.

On the letter, the sound is indicated in square brackets.

There are no sounds: [e], [e], [yu], [i], [b], [b], [g '], [w '], [c '], [th], [h ], [sch].

How are sounds pronounced?

We pronounce sounds while exhaling (only in the case of the interjection "a-a-a", expressing fear, the sound is pronounced while inhaling.). The division of sounds into vowels and consonants is related to how a person pronounces them. Vowel sounds are pronounced by the voice due to the exhaled air passing through the tense vocal cords and freely exiting through the mouth. Consonant sounds consist of noise or a combination of voice and noise due to the fact that the exhaled air meets an obstacle in its path in the form of a bow or teeth. Vowel sounds are pronounced loudly, consonant sounds are muffled. A person is able to sing vowel sounds with his voice (exhaled air), raising or lowering the timbre. Consonant sounds cannot be sung, they are pronounced equally muffled. Hard and soft signs do not represent sounds. They cannot be pronounced as an independent sound. When pronouncing a word, they affect the consonant in front of them, make it soft or hard.

Vowel sounds are pronounced loudly, consonant sounds are muffled. A person is able to sing vowel sounds with his voice (exhaled air), raising or lowering the timbre. Consonant sounds cannot be sung, they are pronounced equally muffled. Hard and soft signs do not represent sounds. They cannot be pronounced as an independent sound. When pronouncing a word, they affect the consonant in front of them, make it soft or hard.

Transcription of a word

Transcription of a word is a recording of sounds in a word, that is, in fact, a record of how the word is pronounced correctly. Sounds are enclosed in square brackets. Compare: a is a letter, [a] is a sound. The softness of consonants is indicated by an apostrophe: p - letter, [p] - hard sound, [p '] - soft sound. Voiced and voiceless consonants are not marked in writing. The transcription of the word is written in square brackets. Examples: door → [dv'er '], thorn → [kal'uch'ka]. Sometimes stress is indicated in transcription - an apostrophe before a vowel stressed sound.

There is no clear correspondence between letters and sounds. In the Russian language, there are many cases of substitution of vowel sounds depending on the place of stress of a word, substitution of consonants or dropping out of consonant sounds in certain combinations. When compiling a transcription of a word, the rules of phonetics are taken into account.

Color scheme

In phonetic parsing, words are sometimes drawn with color schemes: letters are painted with different colors depending on what sound they mean. Colors reflect the phonetic characteristics of sounds and help you visualize how a word is pronounced and what sounds it consists of.

All vowels (stressed and unstressed) are marked with a red background. Iotated vowels are marked green-red: green means a soft consonant sound [y ‘], red means the vowel following it. Consonants with solid sounds are colored blue. Consonants with soft sounds are colored green. Soft and hard signs are painted in gray or not painted at all.

| Vowels | ao u e i y y y y e e |

| Consonants | c w w b c d d h k l m n n r s t f x h y |

| b, b | b b |

Designations:

- vowel, - iotated, - hard consonant, - soft consonant, - soft or hard consonant.

The blue-green color is not used in the schemes for phonetic analysis, since a consonant cannot be both soft and hard at the same time. The blue-green color in the table above is only used to show that the sound can be either soft or hard.

Words with the letter ё must be written through ё. Phonetic parsing of the words "everything" and "everything" will be different!

letters and sounds in Russian (with audio)

4Mar 03/21/2022What letters and sounds are there in Russian? Which letters represent which sounds? What is the difference between soft and hard consonants? When is a consonant hard and when is it soft? Why do we need soft (b) and hard signs (b)?

Want to find answers to all these questions? Then read on!

Below you will find an interactive Russian alphabet with audio. For each letter [in square brackets], the sounds that it can stand for are indicated, as well as examples of words with this letter.

For each letter [in square brackets], the sounds that it can stand for are indicated, as well as examples of words with this letter.

And here, for sure, you will immediately have two questions:

№1 Why do some letters have two sounds?

This is a feature of the Russian language. Some letters can represent two different sounds: a hard and a soft consonant. To clearly demonstrate this principle, I specially selected two examples for such letters: one with a hard consonant, and the other with a soft consonant.

#2 Why are no sounds shown for 'ь' and 'ъ'?

These are soft and hard signs. By themselves, they do not represent any sounds. They show us how to read the previous consonant: a consonant before a hard sign will be hard, and a consonant before a soft sign will be soft.

Also, sometimes we need to separate a consonant from a vowel, and for this we will write one of these signs between them. This is how we distinguish, for example, the words “seed” [s′ém′ʌ] and “family” [s′im′jʌ́].

Now, when you listen to the audio, pay attention to these pronunciation features.

But how do you know when a consonant is hard and when soft?

Very easy! You need to look at the next letter.

- Before with a hard sign (Kommersant) , before other consonants and before the vowels A , O , in , E, 9 s consonant - hard .

- Before soft sign (b) and in front of the vowels I , Y , U , E , and CONTARTS 9007

Ref: consonant w , w , c 90 073 -+a = d′+a

See? This [th]-component makes the consonant soft!

Finally, let's move from theory to practice! Try to read these words.