Math reading success

Math More Than Reading Is the Best Predictor of Future Academic Achievement – SumoMath Blog

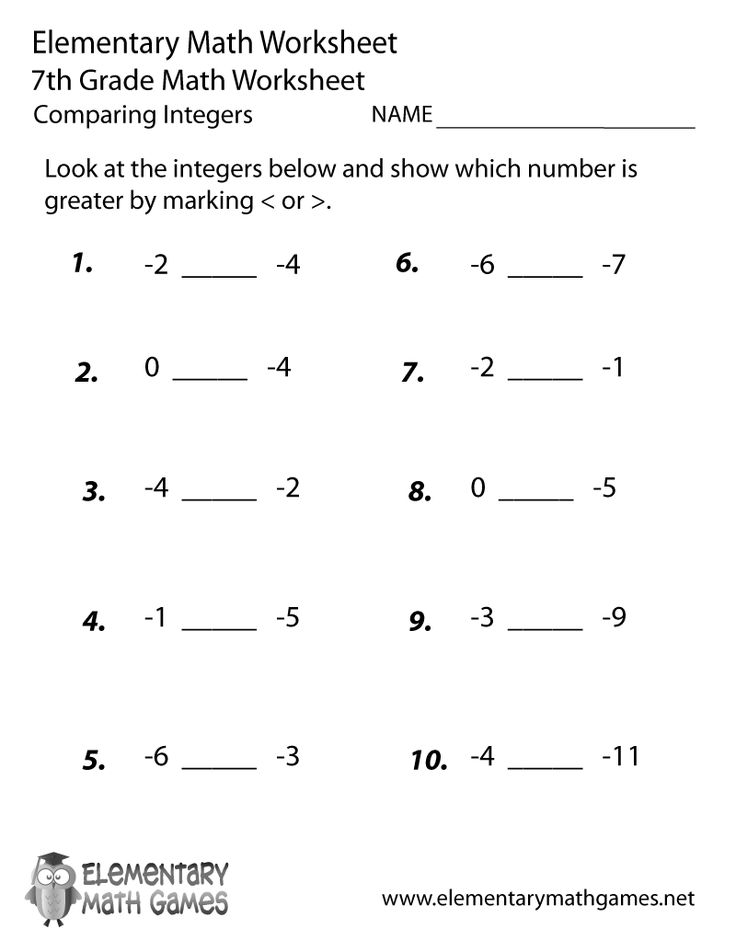

You might, as I did, find this article surprising if you have a young learner just about to enter kindergarten. According to research conducted by a group of university professors called “School Readiness and Later Achievement“, math skills entering kindergarten are the best predictor of future academic success more so than reading skills, attention skills, or socio-emotional behaviors.

Mathematics rightly viewed not only possesses truth but supreme beauty.

by Bertrand Russel

We all know math is important but these results may alter long held beliefs about what really affects later academic achievement as students enter kindergarten. The study goes on to say that pre-school math skills such as knowledge of numbers and ordinality are equally good predictors of future reading achievement.

In other words, early development of mathematic skills also produces future reading success! The California Kindergarten Association states: “How important is math in the early years when compared to other domains like reading, attention, or socio-emotional development? Very.“

As professor Duncan sites in the research report, President George W. Bush endorsed Head Start reforms that focus on building early academic skills, observing that “on the first day of school, children need to know letters and numbers. They need a strong vocabulary. These are the building blocks of learning, and this nation must provide them”. But the debate over which preschool skills really produce later academic achievement vary over a wide gamut of ideas. Kindergarten teachers describe the preschool challenge as “weaknesses in academic skills, problems with social skills, trouble following directions, and difficulty with independent and group work as key issues for student academic success”. Others argue “the elements of early intervention programs that enhance social and emotional development are just as important as the components that enhance linguistic and cognitive competence”. But Duncan and his colleagues have shown early math skills are the dominant predictor of future learning.

But Duncan and his colleagues have shown early math skills are the dominant predictor of future learning.

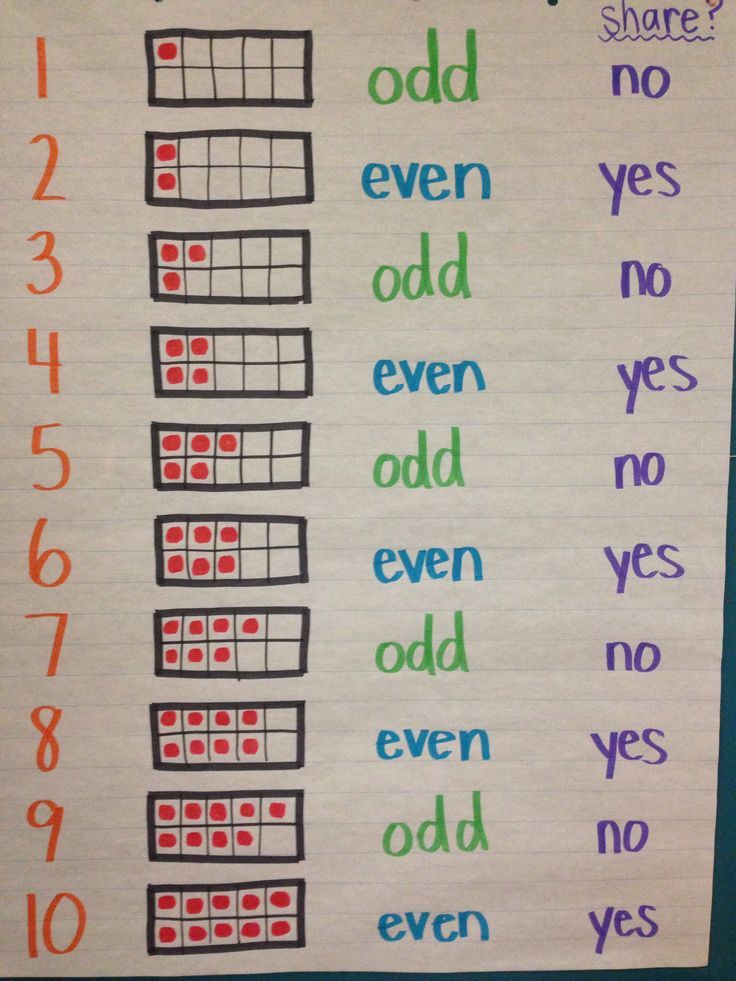

The skills children possess when entering school might result in different achievement patterns in later life. According to Duncan, “if achievement at older ages is the product of a sequential process of skill acquisition, then strengthening skills prior to school entry might lead children to master more advanced skills at an earlier age and perhaps even increase their ultimate level of achievement”. The School Readiness study looked at 6 preschool skills and behaviors: math, reading, attention, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and social skills to determine what best predicts future academic achievement.

As we would expect preschoolers with math skills such as basic numeracy and number sense should produce better future math outcomes. As well we would expect reading skills such as basic literacy and vocabulary should impact future reading outcomes. Common sense would suggest that students that can maintain attention and concentration should affect their future achievement due to their increased engagement and classroom participation. We can also understand how interpersonal skills or behavioral problems might influence student participation and learning outcomes. What was not expected is how dominant a predictor of future academic achievement it turns out math is!

Common sense would suggest that students that can maintain attention and concentration should affect their future achievement due to their increased engagement and classroom participation. We can also understand how interpersonal skills or behavioral problems might influence student participation and learning outcomes. What was not expected is how dominant a predictor of future academic achievement it turns out math is!

Math was by far the strongest predictor of academic achievement with reading half as strong and attention less than a quarter as strong a predictor compared to math. None of the socio-emotional behaviors had any significant predictive power. Preschool reading skills are a better predictor of future reading achievement than they are of future math achievement. However, much less expected were the results showing math skills were as good a predictor of reading achievement as were early reading skills. This is a striking research finding.

Student’s attention skills to a much lesser degree were equally important a predictor for both math and reading achievement. Also surprisingly the study shows the association between school-entry skills and later achievement declines more quickly over time for reading than for math outcomes. So it seems early math skills not only are a better predictor of future academic achievement but pay larger dividends over a longer time period than early reading skills, attention, or socio-emotional behaviors. Based on these findings we need more focus on early math education.

Also surprisingly the study shows the association between school-entry skills and later achievement declines more quickly over time for reading than for math outcomes. So it seems early math skills not only are a better predictor of future academic achievement but pay larger dividends over a longer time period than early reading skills, attention, or socio-emotional behaviors. Based on these findings we need more focus on early math education.

The results of this study indicate that early math skills such as basic numeracy and number sense are the most powerful predictors of later learning. Less powerful predictors were early language and reading skills such as vocabulary, knowing letters, words, and beginning and ending word sounds. A surprising result worth repeating is early math is a more powerful predictor of later reading achievement than early reading is on later math achievement. However the question of why remains unanswered.

This research clearly suggests that parents, educators, preschools, and elementary schools should take note of the importance of early math skills and the impact it has not just on future math achievement but also on later reading achievement. Although schools teach both reading and math, there seems to be slightly more focus on reading and writing than in early math education. This study clearly suggests we might produce better future learning outcomes if education policies placed more emphasis on early math education.

Although schools teach both reading and math, there seems to be slightly more focus on reading and writing than in early math education. This study clearly suggests we might produce better future learning outcomes if education policies placed more emphasis on early math education.

How should we consider this research in terms of existing curricula and possibly new curricula that should be produced. The study suggests curricula focusing on the most powerful learning predictors of academic and attention skills that are fun and engaging would produce the best future achievement results. It is with this information, mindset, and objective we built the rightlobemath.com online abacus math program focusing on basic numeracy, number sense, arithmetic, and engaged student concentration. If we want to move the needle in terms of better future learning outcomes and graduation rates, we must deliver effective early math education that is not only universally available to early learners but self-motivating and engaging. We must place math at the forefront of every students’ early learning agenda. Doing so, will focus our efforts where we may see the largest societal benefits for the investment made.

We must place math at the forefront of every students’ early learning agenda. Doing so, will focus our efforts where we may see the largest societal benefits for the investment made.

Math tutoring offers multisensory experience

If a child struggles with math at school, those difficulties are sometimes blamed on “just being bad at math” — a dismissive notion that reinforces the child’s frustration and feeling of failure. If an adult has no idea now to split the check at a restaurant or is confused by the monthly bank statement, that’s often shrugged off as “not having a knack for numbers,” a gentler phrase that still assumes a lifetime of bafflement during any encounter with math.

It doesn’t have to be that way.

Reading Success Plus was founded to help people with reading disabilities, but from the beginning many of its students had similar difficulties with math and wanted help. So RSP began offering math tutoring, in person and online, using the same multisensory Orton-Gillingham (OG) principles that are the foundation of the reading program. It helps students learn the why of math in an explicit, direct and multisensory manner.

It helps students learn the why of math in an explicit, direct and multisensory manner.

“When I was a kid, I used to struggle with numbers big-time,” says Lawrence Kloth, co-founder of Reading Success Plus and a tutor in the math program. Lawrence has dyslexia as well as dyscalculia, a math-based learning difference. His experiences as a youngster helped shape the Reading Success Plus programs. “If I had been taught this way, it would have been a lot easier for me because I would have understood the basics more.”

Making abstract ideas real

The OG Academic Math program takes the abstract concepts of math and, with practice, makes them concrete. Students from early elementary through middle school use their senses of vision, hearing and touch to learn addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. They also learn the vocabulary of math, the strategy of solving word problems, time, money, measurement, fractions, percentages, decimals and more. Ideally, tutoring sessions are twice a week, though parents can choose to meet once weekly.

Like other Reading Success Plus programs, math is taught only one-on-one, so students can get the time and attention they need. Concepts are taught at a pace that fits the student, not a timetable built into a curriculum written for an entire school district or state.

New students are given a screening to determine what their math skills and weaknesses are, so instruction starts at an appropriate level. The screening team also finds out if a student is receiving accommodations in school so the tutoring can reflect that.

“The goal is getting them up to speed, getting them caught up with their classmates,” says Dawn Henretty, director of RSP’s Troy office and an RSP math tutor. Dawn, a former high school math teacher, helped design the RSP math program.

“We want to help students get over their fear of math and get them feeling comfortable working with numbers.”

Lawrence and Dawn emphasized the value of individual attention. “It’s always in a one-on-one setting,” Lawrence says. “And we go at the pace of the student.”

“And we go at the pace of the student.”

Matching students’ learning styles

RSP’s math tutoring matches the learning style of the student, not the preferred style of the school.

“Our program is multisensory,” Lawrence says. “That is huge, because one kid might be a better visual learner or another might be an auditory learner. The ADHD students need kinesthetic (movement) learning; dyslexics need more visual.

“And there’s not a lot of multisensory math out there. Unfortunately, a lot of the kids in the population that we deal with don’t get the schooling they need. I don’t blame the teachers, because they have 50 other kids they have to teach. But we can give our kids more personal attention in the learning style that works for them.”

Because tutoring can be done in person or online, help is available to anyone, anywhere.

According to the website for OG Academic Math, which is the source for much of the following material, it isn’t surprising that many reading students also need support for math. While dyslexia is associated with reading difficulty, it really is a difference in how the student processes information. As with most other subjects, schools teach math in a linear, sequential manner. Dyslexic brains aren’t “wired” to learn that way, in reading, math or anything else.

While dyslexia is associated with reading difficulty, it really is a difference in how the student processes information. As with most other subjects, schools teach math in a linear, sequential manner. Dyslexic brains aren’t “wired” to learn that way, in reading, math or anything else.

Further, scientists believe there is a genetic overlap between dyslexia and dyscalculia. Experts say dyscalculia affects as much as 10 percent of the population (about the same as dyslexia), but 40 percent of dyslexics also have dyscalculia.

On top of that, many students with reading difficulty have other disabilities that contribute to learning problems. Memory disabilities, visual and auditory discrimination disabilities, spatial or directional disabilities, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder all affect math performance as well as reading.

Orton-Gillingham is applied to math

Because of these common factors, RSP uses an Orton-Gillingham based math program that employs the same principles as the Barton Reading and Spelling System that has helped so many students.

The OG Academic Math program recognizes various learning styles by using visual, auditory, kinesthetic (muscle memory) and tactile approaches. The kinesthetic and tactile methods are particularly effective in reaching struggling math learners. The program uses “manipulatives” — colored blocks that students use to represent numbers. They use these blocks to build equations, then manipulate them in mathematical operations such as addition and subtraction. The abstract ideas of math become something concrete that students can hold in their hands. In addition, students are asked to trace or write on textured surfaces, something especially helpful when learning to write numerals.

Students engage their senses by following the Build-Draw-Name process. In the first step, they Build by using blocks to represent the numbers and manipulate the blocks to represent the equation at a physical level. Next, they Draw blocks that represent the number. Students can still see what each number represents, but they are using a less concrete form. Finally, they Name the concept using mathematical symbols such as numerals and an “equals” sign. Even at this level, students can use drawings or objects to trigger their memories.

Finally, they Name the concept using mathematical symbols such as numerals and an “equals” sign. Even at this level, students can use drawings or objects to trigger their memories.

Build-Draw-Name can be used to represent something as simple as a number or as complex as an equation.

How it works The Build-Draw-Name process helps students understand math problems on several levels.Here, the student is asked to solve the addition problem 4+7. By using the blocks, the student makes the problem something they can touch and understand at the most concrete level. By drawing the problem, the student still can “see” the problem, but it becomes more abstract. Finally, by naming the problem using numerals and mathematical symbols and reading it out loud, the student tackles it at a conceptual level. Students can prove the equation is correct by looking at the manipulatives to see the problem being solved. Abstract numbers become visual and concrete solutions, and, with practice, are hard-wired into memory.

Once students understand the basics, they begin learning how to apply this knowledge.

“We let them know what is the purpose, why they learn math, why some of the concepts are important in their everyday lives,” Dawn says. Understanding length and width and calculating area and perimeter are commonly used skills. Math helps you balance your checkbook or figure out how many cans of paint you need to cover a room. Even the often-despised story problems are examples of using math to solve real-life problems. (Someday you really will want to know how long it takes your car to go from point A to point B.)

“Our students are bright, curious kids,” Lawrence says. “They always want to know the ‘why’ of everything – why do I have to take math, why do we have to do things this way. This program addresses the why.”

Reading Success Plus has offices in Grand Rapids and Troy and offers one-on-one tutoring online or in person in reading, math and writing. For more information, call 833-229-1112.

For more information, call 833-229-1112.

Children's success in reading and maths depends on their personality traits

Personality traits of children influence their reading and maths success

A team of researchers from the USA conducted a large-scale study based on information obtained during the Texas Twin Project traits affect children's reading and math skills.

In a new study by Dr. Margherita Malancini and her colleagues at the University of Texas at Austin, researchers found that traits associated with openness—like intellectual curiosity and confidence—help kids excel in math and reading more than traits associated with openness. with diligence, perseverance and conscientiousness. The study was published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Self-discipline is the ability to control behavior and inner state in the face of conflicting or distracting situations and urges.

In cognitive psychology, individual differences in self-discipline are often measured through tests based on results in executive functioning. In personality psychology, on the other hand, individual differences in self-discipline are usually assessed using measures based on impulse control, persistence of motivation, and perseverance.

In personality psychology, on the other hand, individual differences in self-discipline are usually assessed using measures based on impulse control, persistence of motivation, and perseverance.

"Previous studies have linked differences in academic skills to differences in self-discipline, or how well children are able to control their behavior and state of mind in the face of conflict or distractions and urges," the authors say. "However, self-discipline is a broad construct that includes and intellectual abilities such as executive functioning; and personality traits such as conscientiousness."

To understand the core skills and traits of self-discipline and how they affect differences in reading and math abilities, researchers analyzed data from a study of 1019twins aged 7.8 to 15.5 years in the Texas Twin Project.

Even adjusting for intelligence, the team found a strong link between executive functioning—the ability to plan, organize, and complete tasks—and the ability to read and solve math problems. This relationship is largely due to genetic factors.

This relationship is largely due to genetic factors.

Children with higher levels of executive functioning showed increases in levels of openness, intellectual curiosity and confidence. These associations were classified as common genetic factors (60%) and environmental factors (40%).

However, the researchers did not see that the same personality characteristics described how conscientious or diligent a child is.

"This indicates that some of the genetic factors that predispose children to academic excellence are the same genetic factors that predispose children to be open to new challenges, creativity, intellectual curiosity, and confidence in their academic ability," says co-author research by Dr. Elliot Tucker-Drob.

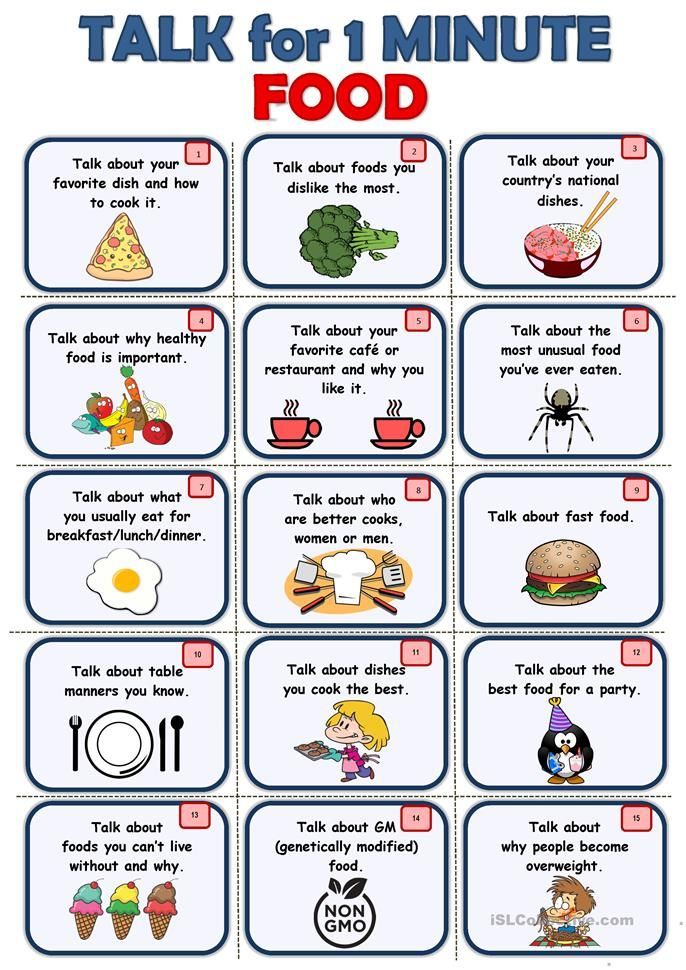

The role of reading in teaching mathematics

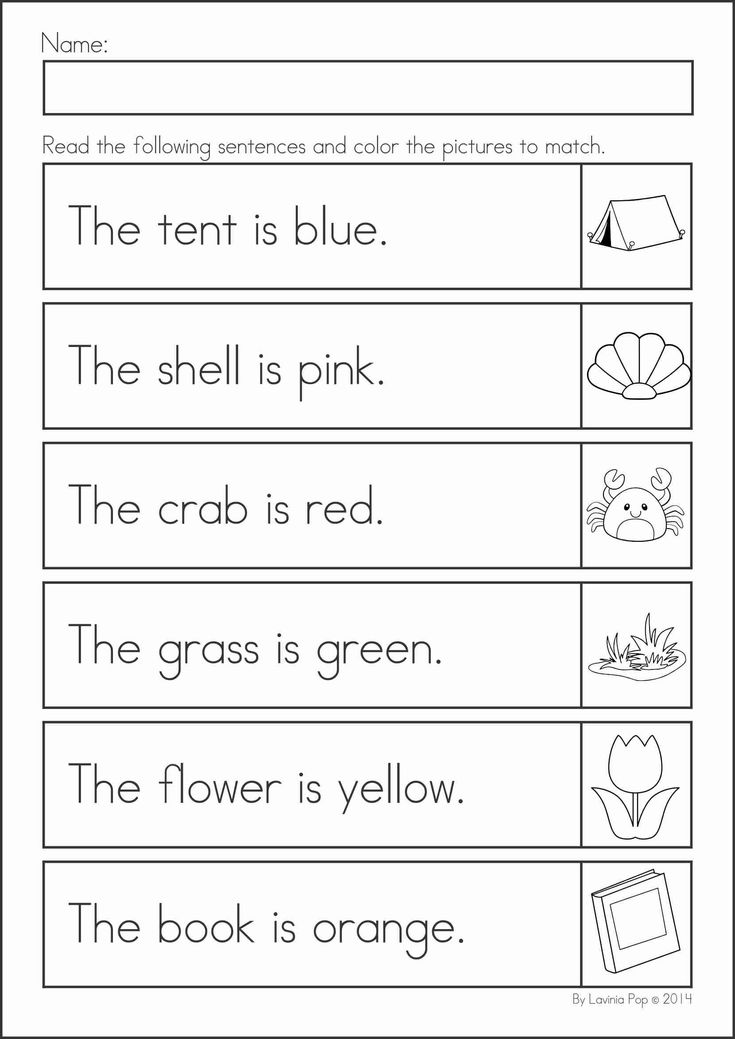

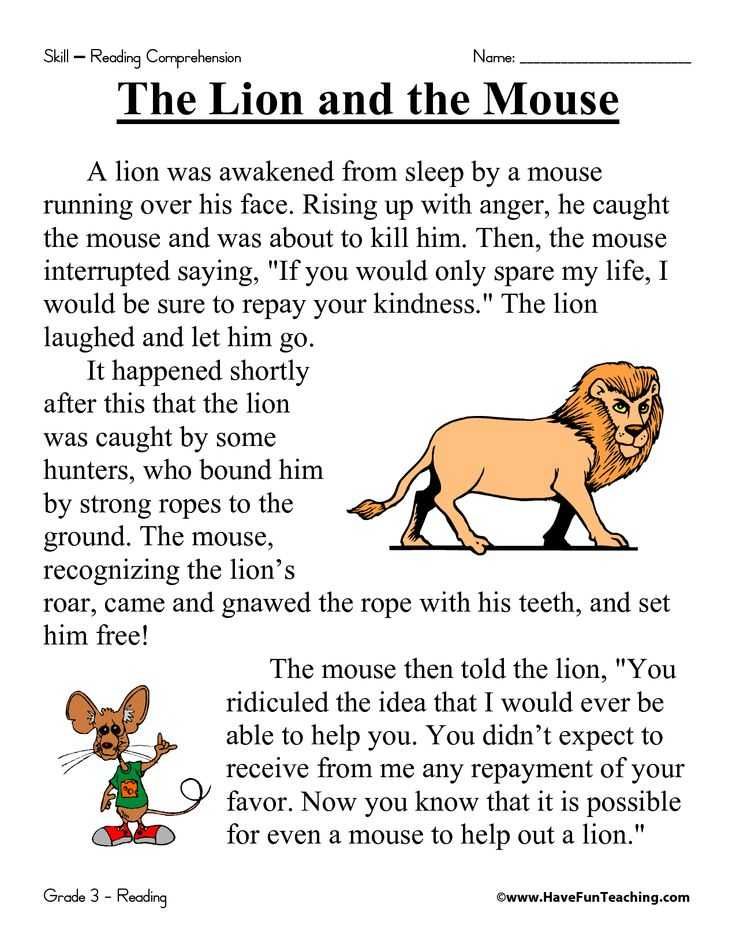

One of the important keys that open the door to understanding and success in mathematics (and not only) is reading .

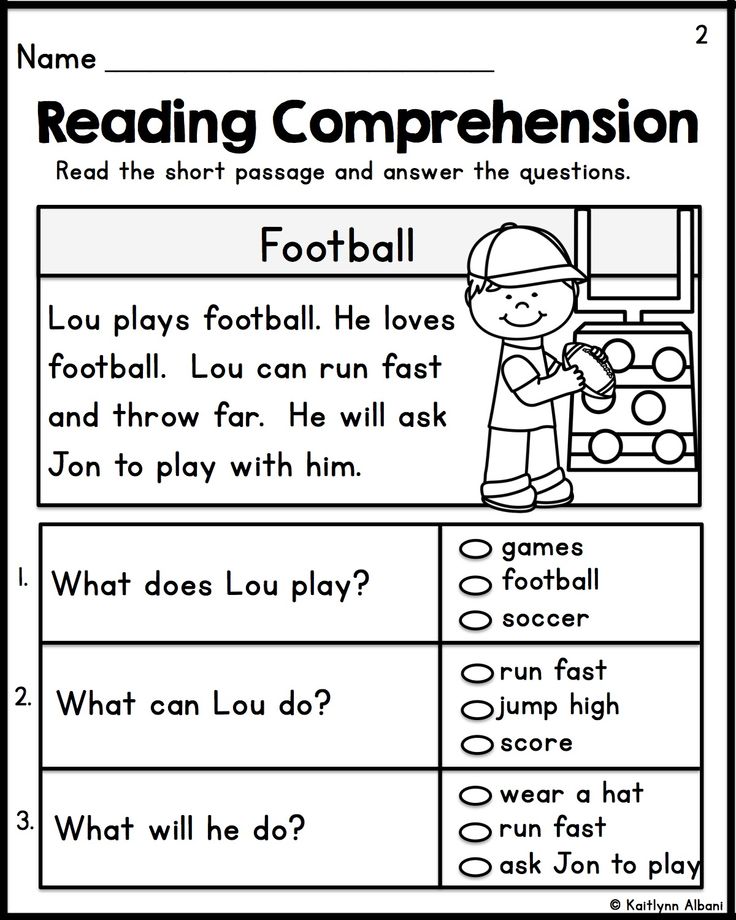

The ability to read, and most importantly, to understand what is read is important not only when reading fiction, but also when solving mathematical problems.

Therefore, a decent level of a child in reading is simply necessary for successful solution of mathematical problems . It gives the student an understanding of what exactly is being discussed in the problem, what is missing to answer the main question, and what, on the contrary, is redundant information.

Why is reading so important?

Understanding conditions of the problem provides an opportunity to accurately determine the course of the solution, if the formulation of the condition differs from the usual one, to which the algorithm was developed solutions during the study of the main types of tasks. Without understanding the meaning of the condition task, even a slight deviation of its formulation from the usual condition can bring the child into a state of stupor.

A student simply must read a lot , not only to improve his cultural, spiritual, educational level, but also to develop his brain, the ability to think, reflect, think.

Necessary from a very early age, conduct conversations with the child about what has been read, determine his understanding of the text, leading questions to teach to reveal the essence, to identify important and useful.

The information that enters our brain in verbal and written form requires much more analytical and creative efforts from it than the information presented in a video sequence or pictures. In pictures (for example, in currently popular comics) and video sequences, already formed images are presented. Yes, they cause sensual, emotional reactions, but do not give the brain the opportunity independently analyze, draw, create in your imagination an image of what is being discussed.

And it is precisely that which is being strained that develops. Reading and communication , that is, the written and verbal forms of receiving information, are full . They combine emotions and logic, sensory perception and analytics. Therefore, by reading and communicating, our brain develops in all directions.

Each of your donations increases the amount of useful and interesting information on the site Easy-Math.ru!

Having learned to read, one should not linger for a long time on reading simple texts made up of monosyllabic sentences. It is necessary to gradually and persistently increase the complexity of the readable .

How are reading and mathematics related?

When reading complex texts that contain various literary devices, for example, participial and adverbial phrases, phraseological units, allegories, etc., the child learns that the same words , written in different combinations and situations, can transmit different meanings .

Pushing off from the examples he saw in the literature, the child learns independently put words into coherent, meaningful sentences and texts.

It is complex texts that provide the necessary basis for logic . Having learned to logically transform the material most familiar to him from childhood - the word, the child transfers this skill to abstract concepts - numbers.

/pic4314753.jpg)