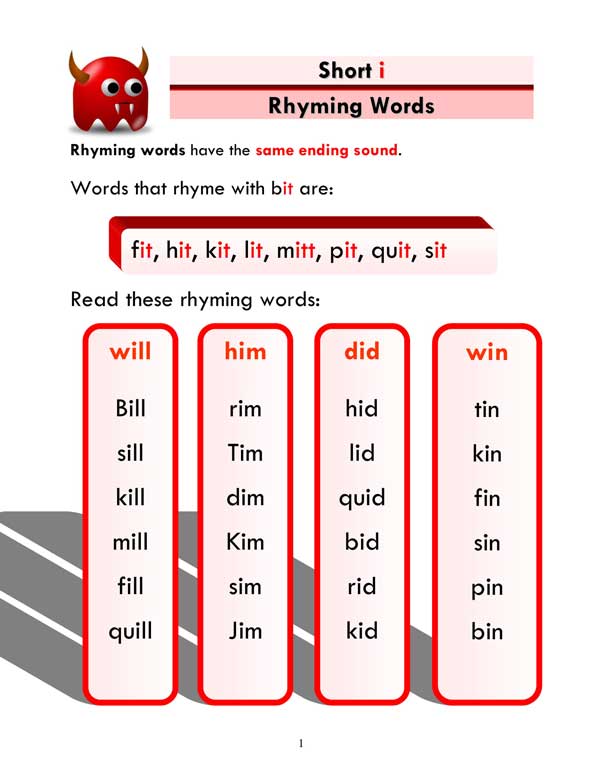

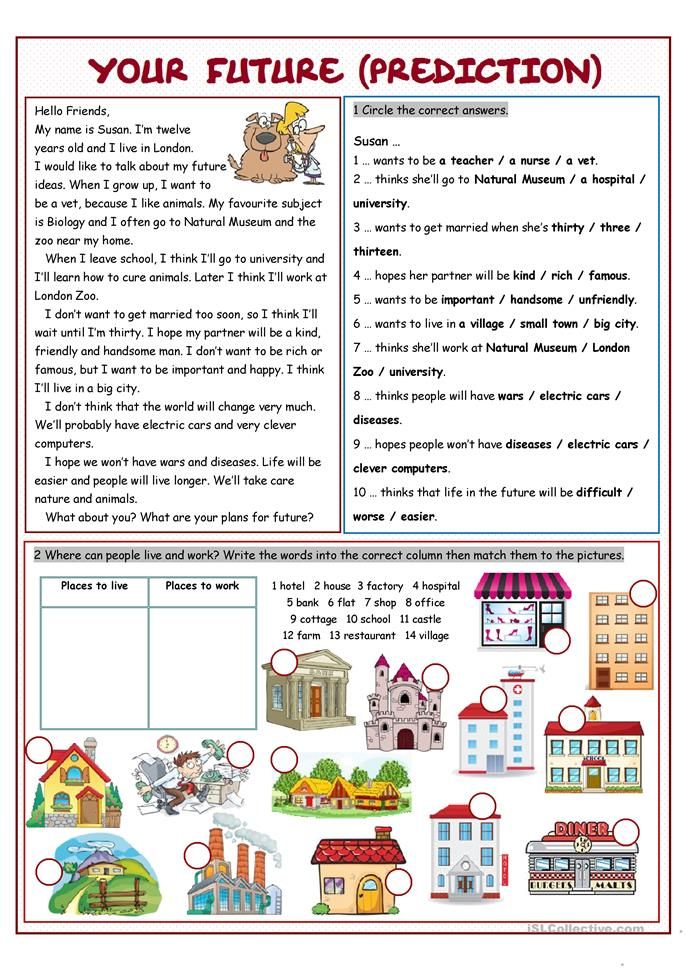

Predicting reading activities

3 Activities for Making Predictions

Making predictions is something that proficient readers naturally do, even without knowing it. As soon as we pick up a new book on the library or book store shelf, we are making predictions and judgments about that book based on the cover as we thumb through the book. Today, I’m sharing 3 activities for making predictions in our 10-week Reading Comprehension Strategies Series.

*This post contains affiliate links.

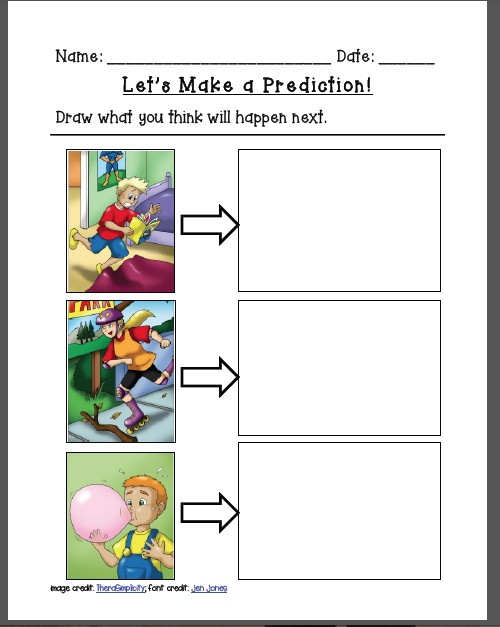

In this post, you will find 3 different activities for making predictions {with a free printable pack which can be found at the end.} We will explore making simple predictions with

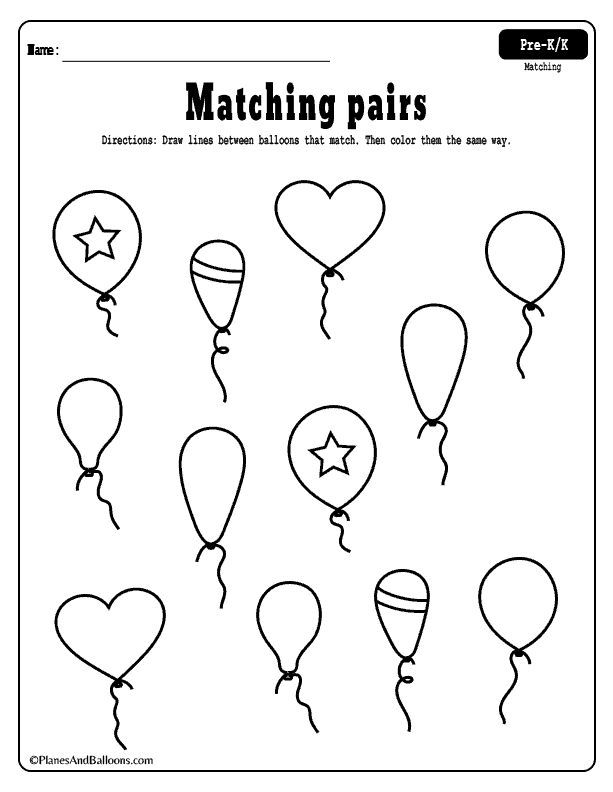

1- Pre-K/K, including pre-writers,

2- making and changing predictions with older kids {2nd through 5th grades} and

3- making predictions with nonfiction text.

Hang with me here because there’s a lot of information!

Teaching Kids to Make Predictions

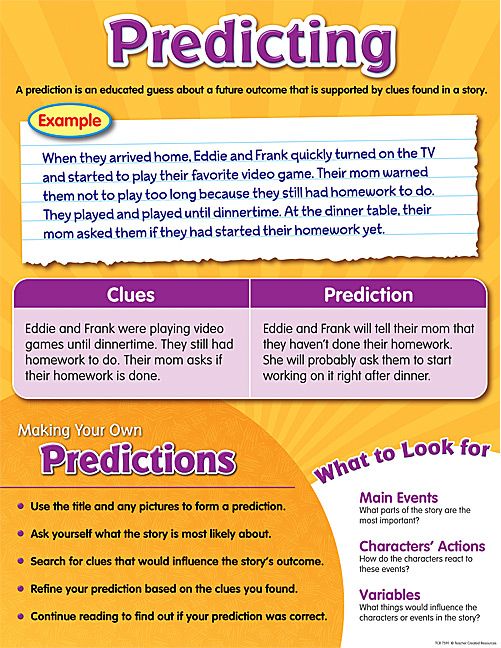

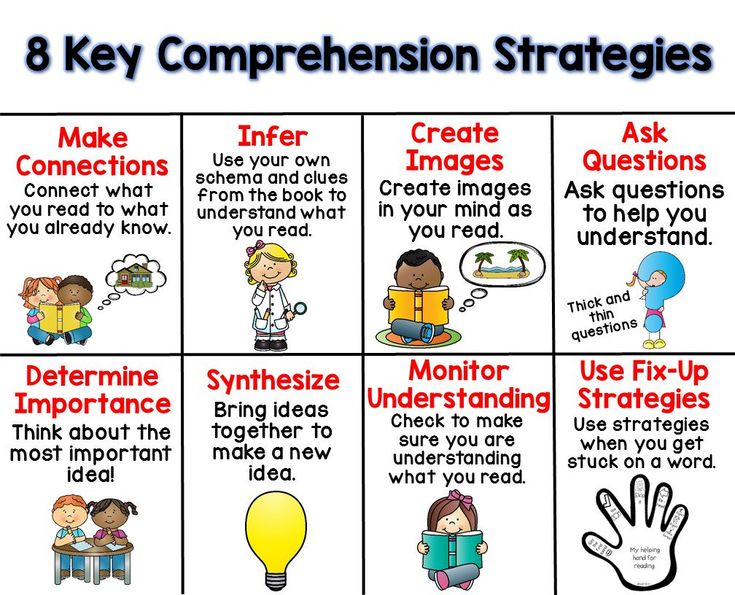

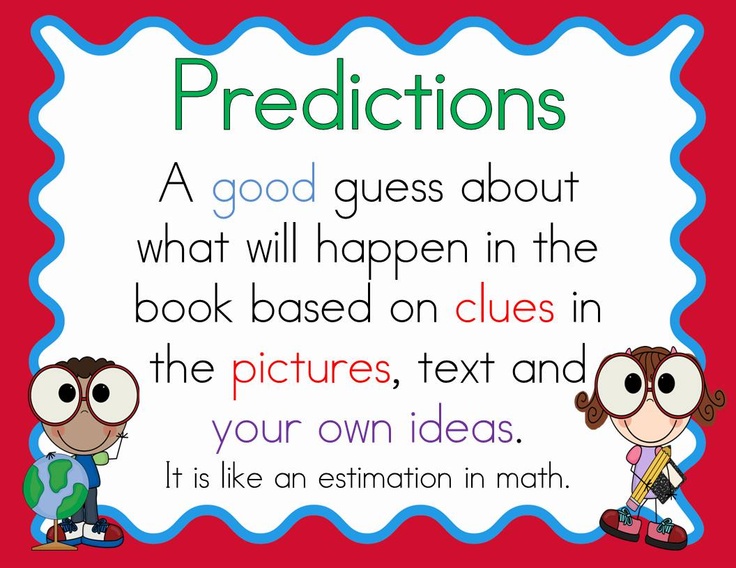

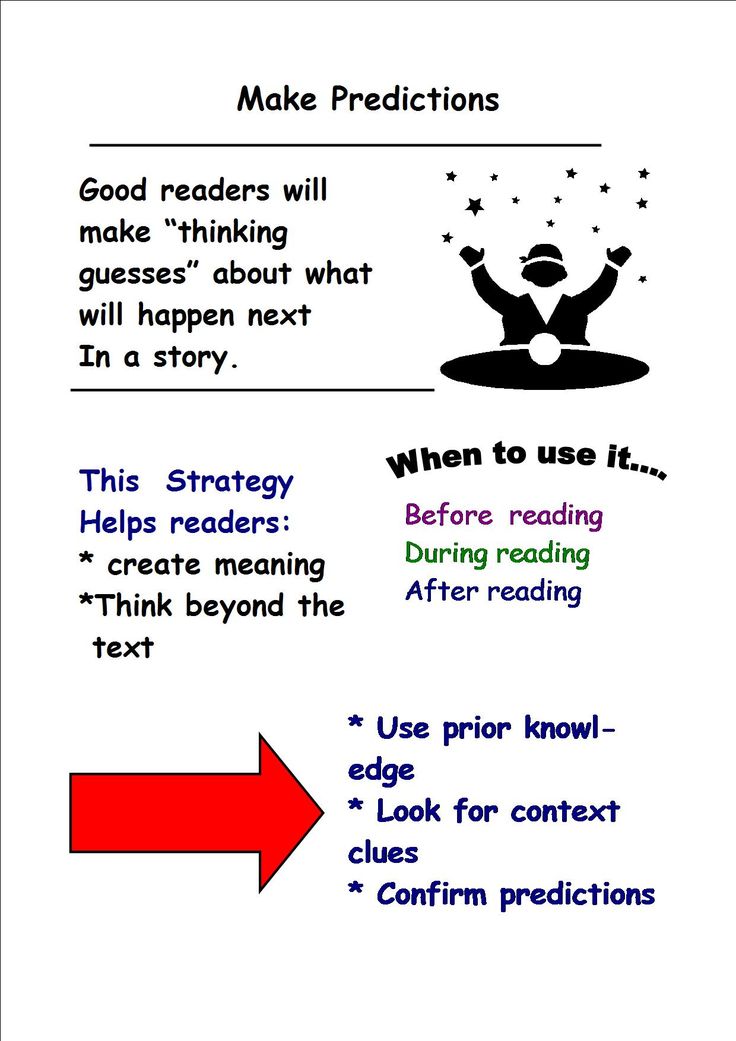

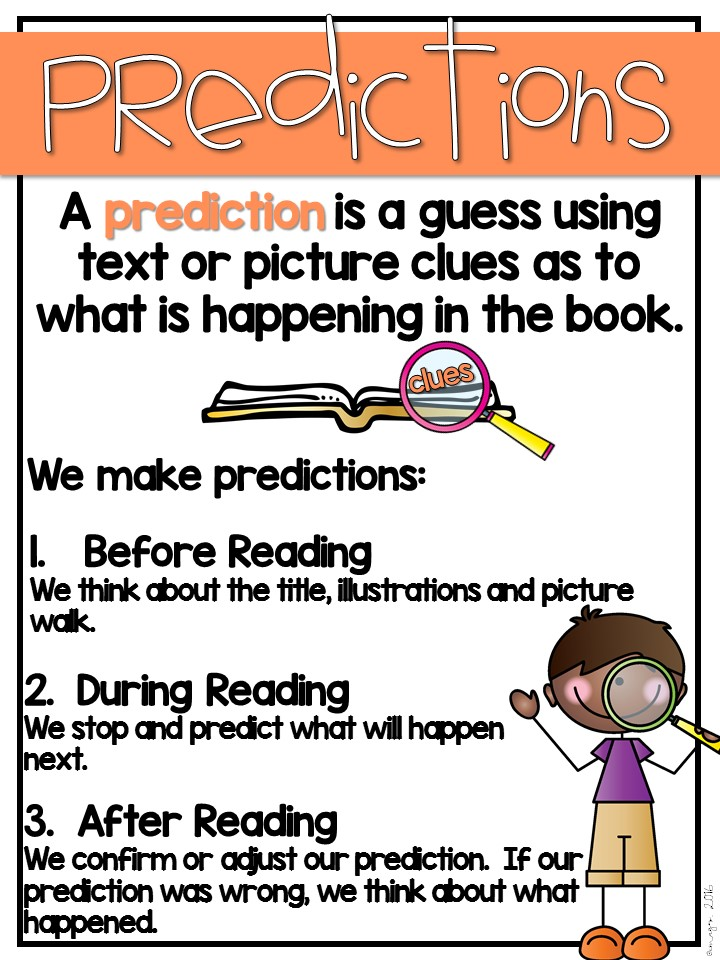

What is a prediction? Predictions are created by combining TWO things: 1- clues the author leaves for the reader, such as the words, pictures or text features and 2- what you know {your schema}.

Justifying predictions: When asking kids to make predictions {or use any other comprehension strategy}, I firmly believe it is important to ask kids WHY they think that. In their answer, I’m listening for them to connect to the text in some way and/or to use their schema or background knowledge.

Asking readers why takes them a step deeper into the comprehension strategy and gets them thinking about their thinking {remember this term from our introduction post: metacognition.} The printables in this pack will also ask kids to justify their answers.

Prepping a Book: It is important when you want to model a comprehension strategy that you look through the book ahead of time and think about how you want to share your thinking and what you want to say. I’ve been teaching comprehension for 12 years now and I still have to prep my thoughts {also known as a think aloud}. Doing it “on the fly” is never as effective as preparing ahead of time.

I even like to post sticky notes within the book where I want to stop and share my thoughts ahead of time. Otherwise, I’ll probably forget. 🙂

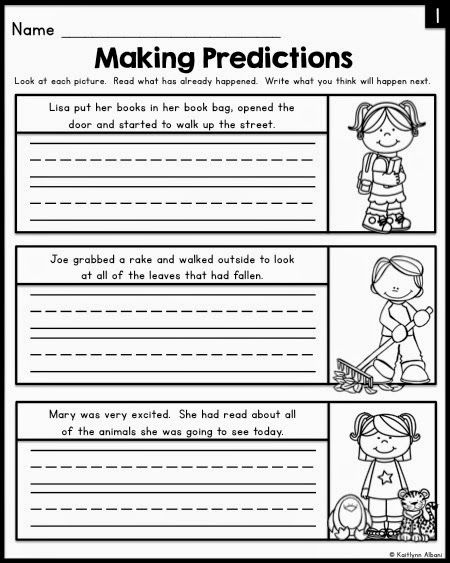

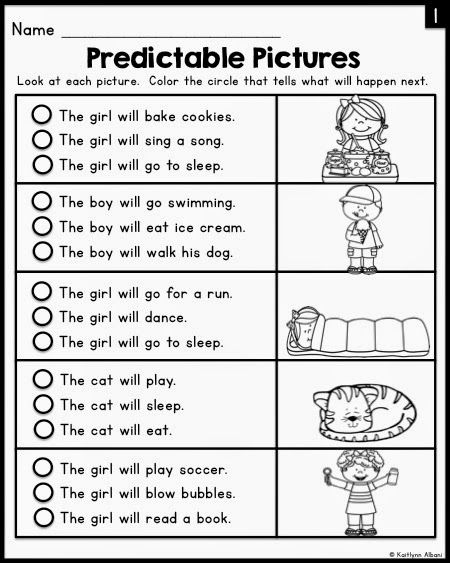

Making Predictions with Young Readers

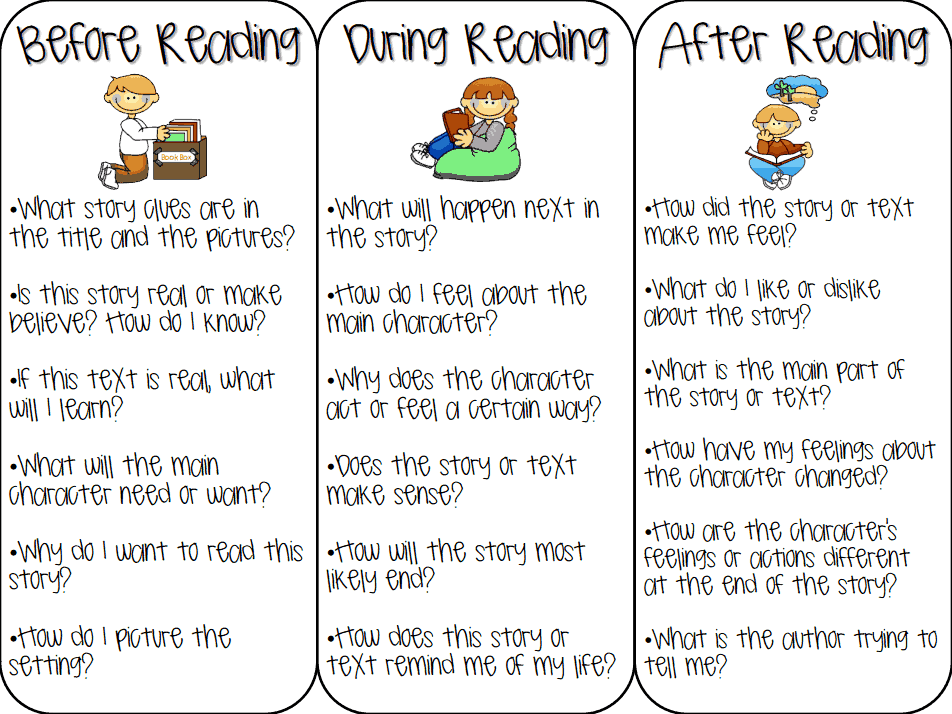

Making predictions is a simple place for young readers to begin their comprehension journey. This can easily be modeled and discussed as you read books together. While looking at the cover and reading the title together, you can share what you think the book will be about; or you can ask your child what he thinks. Before you turn the page in certain parts of the book, you can say, “I think … will happen next because…” or “What do you think will happen next?” Even the youngest of readers can do this.

Just recently, we borrowed a copy of Elmer and Rose by David McKee from the library. This was a book we had never read before {which is important for this comprehension strategy.} The story line is set up to keep readers guessing as to what color Rose’s herd is. I read to certain spot in the book that I had pre-planned, then I stopped. I asked my kids to predict what they thought would happen in the text, namely what color would Rose’s herd be.

I read to certain spot in the book that I had pre-planned, then I stopped. I asked my kids to predict what they thought would happen in the text, namely what color would Rose’s herd be.

MBug {age 4} guessed Gray. When I asked her why, she said because that was the color of Elmer’s herd.

NJoy {Kindergarten} guessed pink because Rose is pink. When I pressed a little further, he also mentioned that Rose said the gray elephants looked “strange”, so her herd was probably not gray.

Making and Changing Predictions

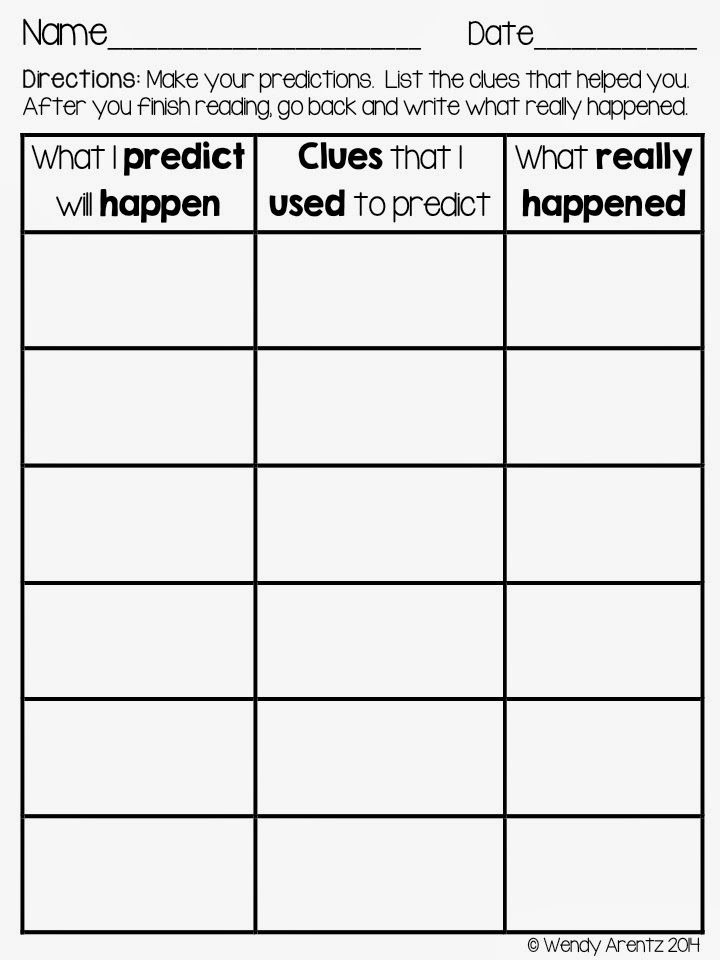

As readers grow in their understanding of making predictions, it is important to help them see that we constantly monitor our predictions, tweaking ours or making new ones entirely if necessary. This is an activity I did with my 3rd grader. While younger kids can do this too, all the writing it requires was of no interest to my Kindergartner.

To do this, I created a T-chart. The left side of the chart asks for predictions, while right side asks for justification of the predictions. {Why did you make that prediction?}

{Why did you make that prediction?}

First, I modeled with Chester’s Way by Kevin Henkes, showing how I wanted him to think and use the printable T-Chart. By the end of the text, I was asking for his input, giving lots of support.

The next day, we used the text Piggie Pie by Margie Palatini. This time, I released more of the responsibility to him, but I was still there to offer support when needed. He started with the cover, making predictions about the book on the left side, then justifying predictions on the right side {using reasons from the book mixed with his background knowledge.} He did this throughout the entire book.

Once the book was over, we went back through his predictions on the left side of the chart. I said, “Let’s go through all your predictions and ask ourselves, ‘Was your prediction confirmed?'” If it was, he added a check. If it wasn’t, he crossed it out. His last prediction was never confirmed, so he included a question mark beside that one.

Making Predictions with Nonfiction Text

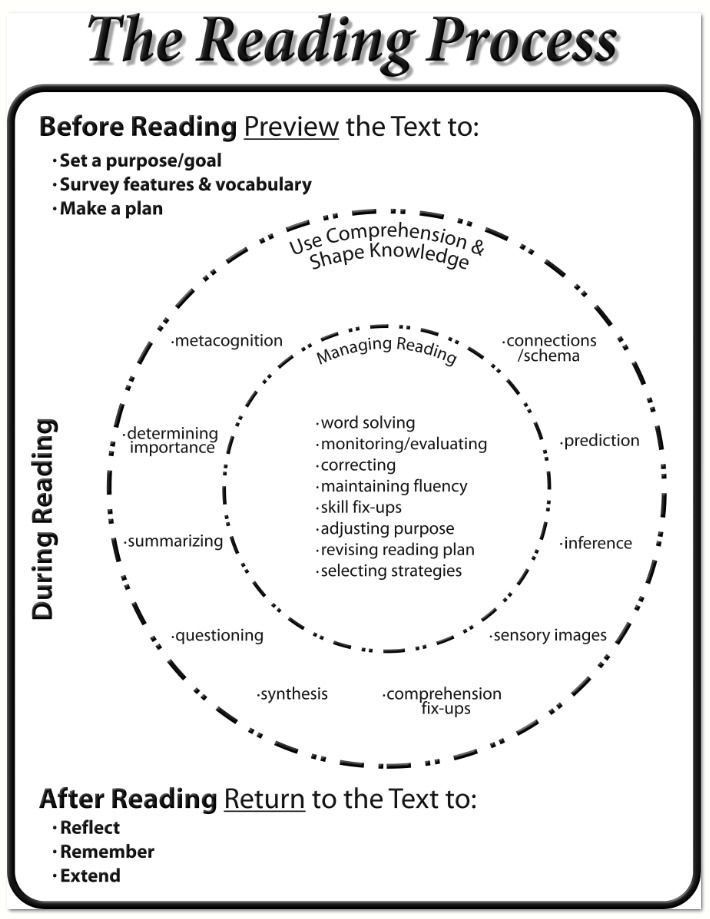

Making predictions is probably paired more with fiction, but readers can also predict with nonfiction. Below is simple activity reader can do before reading. As proficient readers, we automatically do this, but with younger readers, we have to make a switch to manual mode {out of automatic} so that they can “see” our thinking and hear our thoughts.

I modeled this with Hurricanes by Gail Gibbons and he did this with my help using a Discovery Kids book {like this one}, a book he had picked out at the library. For this activity to be effective, the text needs to have plenty of text features for the reader to use. While it doesn’t have to have all the text features mentioned in the list on top of the printable page, it needs to have a good number.

First, ask the reader to look through the text at the text features. {If the reader you’re teaching doesn’t understand what text features are, it would be good to start there first. I have several resources here.} Based on what he observes with various text features from the book, ask the reader to predict what he thinks the book will be about. Making predictions before reading with nonfiction {as well as fiction} is a great activity to help kids set a purpose for reading.

I have several resources here.} Based on what he observes with various text features from the book, ask the reader to predict what he thinks the book will be about. Making predictions before reading with nonfiction {as well as fiction} is a great activity to help kids set a purpose for reading.

I feel like I’ve just shared a load of information in one post. And truth be told, I’ve just skimmed the surface of making predictions!

>>Download our FREE Making Predictions Pack HERE.<<

See all the posts in our Reading Comprehension Strategies series.

Enjoy teaching,

~Becky

Want MORE Free Teaching Resources?

Join thousands of other subscribers to get hands-on activities and printables delivered right to your inbox!

5 Ways to Teach Making Predictions in Reading with Elementary Students

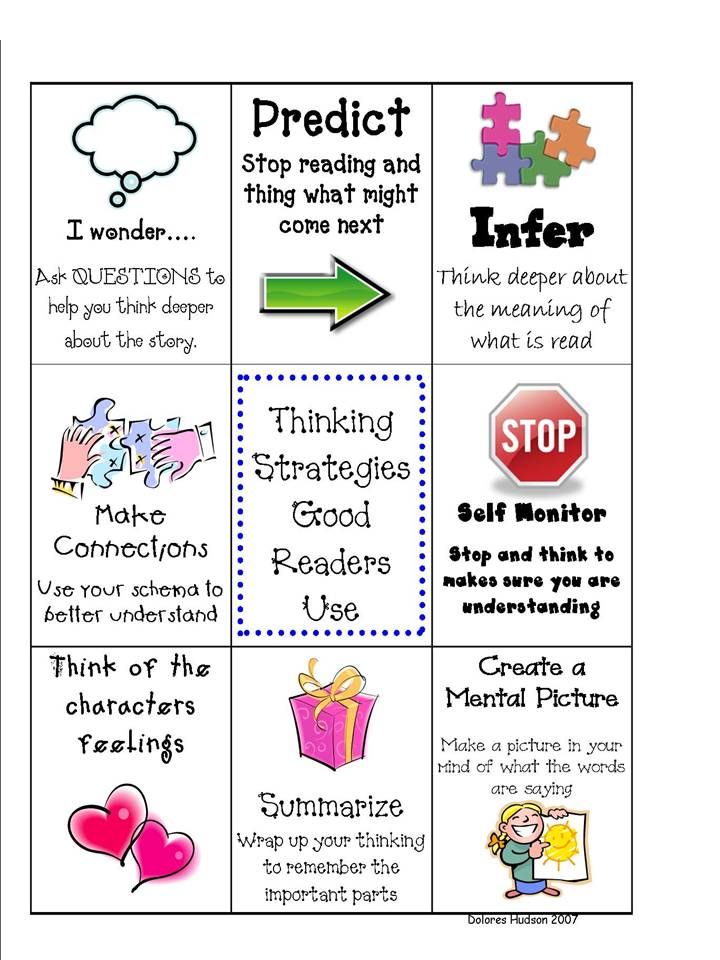

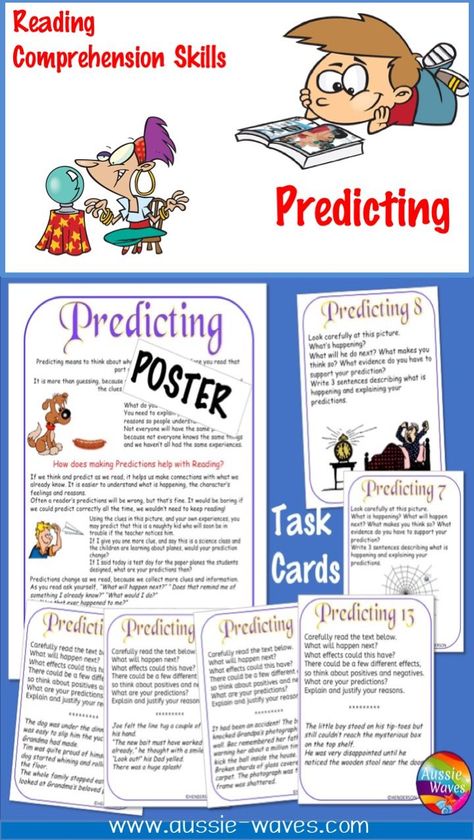

Making predictions is a critical reading comprehension strategy to teach and practice with students. It requires students to use what they have read and know about a topic in order to anticipate what will happen in a text, or what a text will be about.

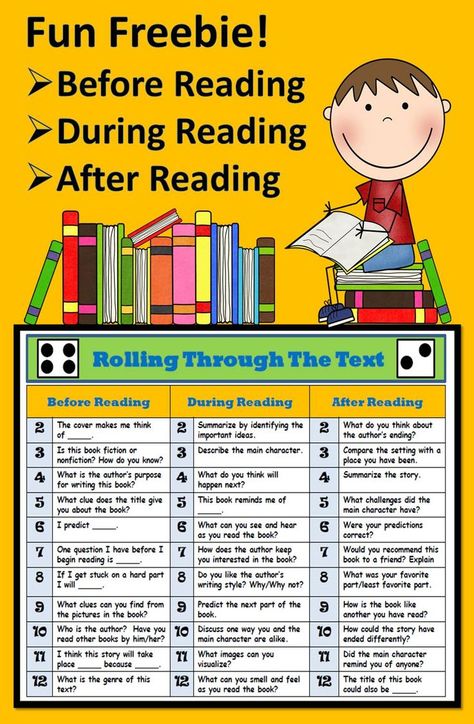

Making predictions before, during, and after reading comes very naturally to skilled readers, but for struggling readers, this skill can be just the opposite. Therefore, it is important that teachers model making predictions and continually provide ways for students to practice this reading comprehension strategy independently.

WHY IS MAKING PREDICTIONS IN READING AN IMPORTANT COMPREHENSION STRATEGY?

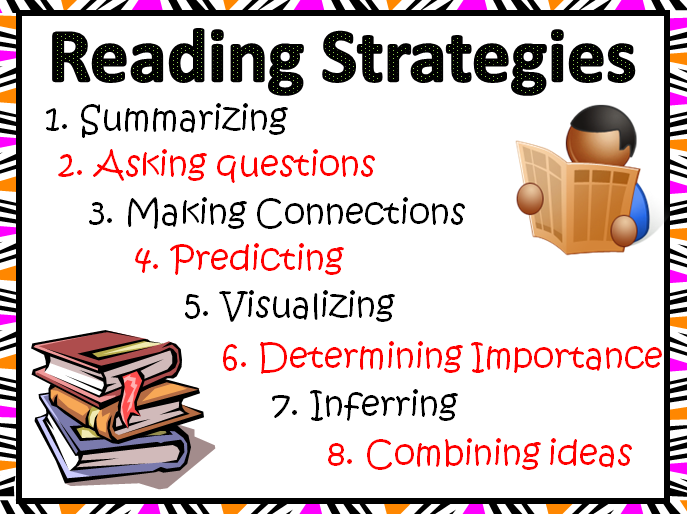

Making predictions helps students to:

- Choose texts they believe will interest them or that are appropriate for whatever their purpose is for reading.

- Set a purpose for reading before, during, and after reading.

- Actively read and interact with a text.

- Critically think about what they are reading.

- Monitor their own comprehension and clarify any misunderstandings while reading.

- Stay engaged in reading in order to find out if their predictions are on track or if they need to be revised.

- Ask meaningful questions.

HOW CAN STUDENTS PRACTICE MAKING PREDICTIONS IN READING?

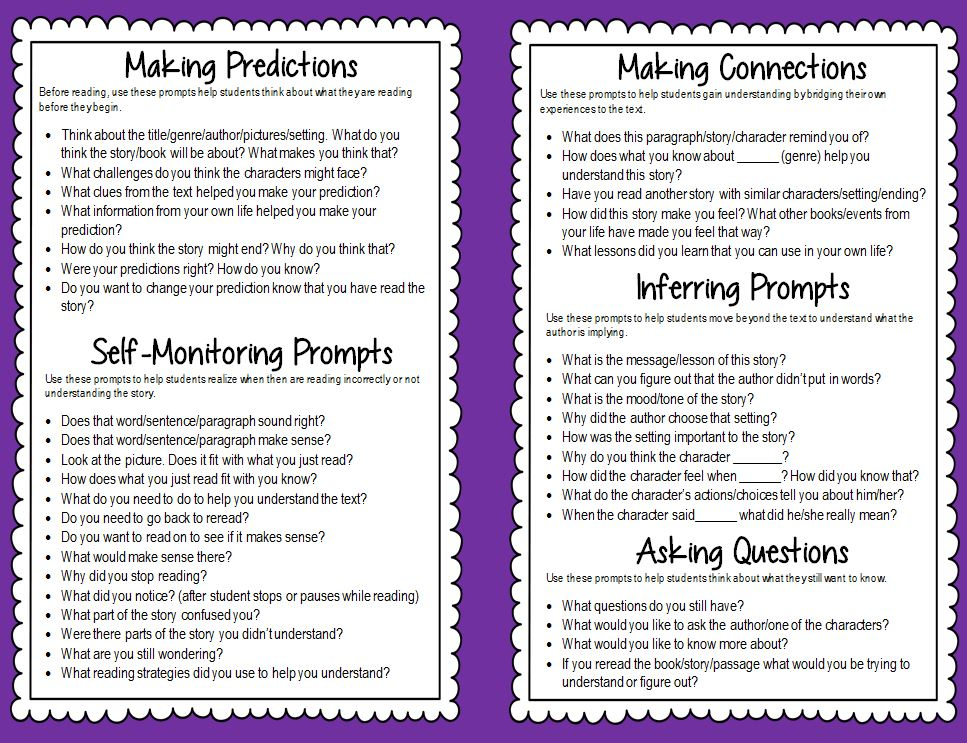

Growing readers can have a difficult time making predictions that are meaningful and logical. By modeling and practicing this reading strategy often, students learn to create strong predictions based on text evidence and background knowledge. Below are five ways students can practice making predictions as a class or individually.

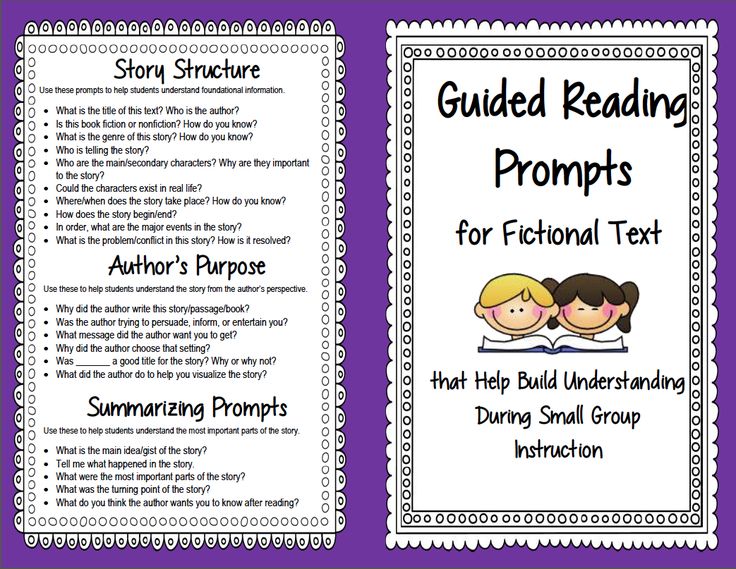

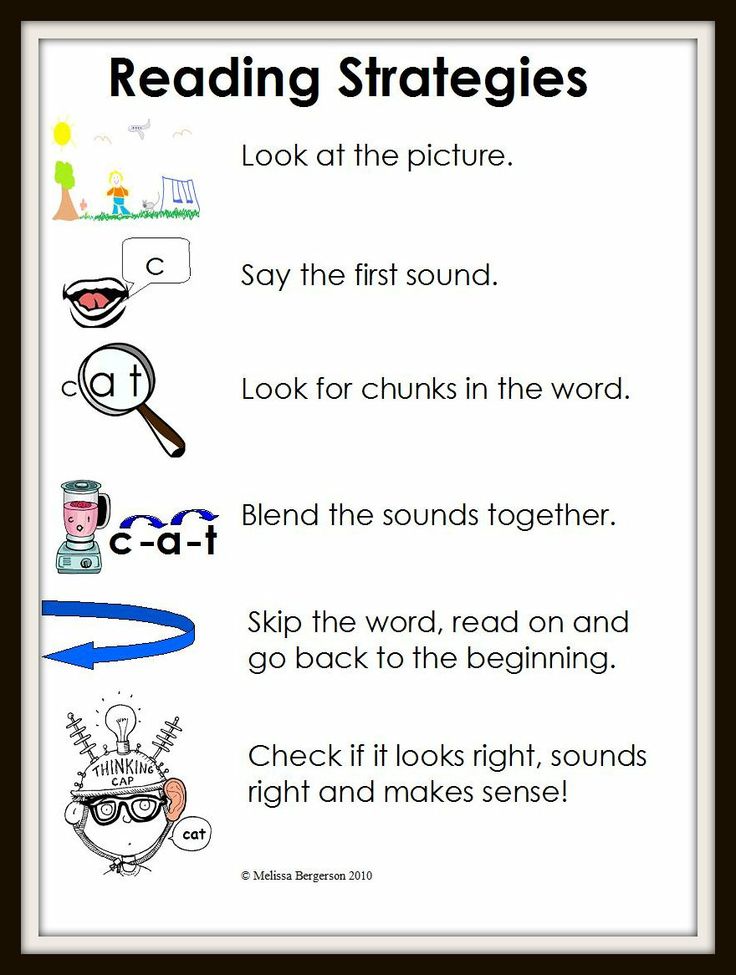

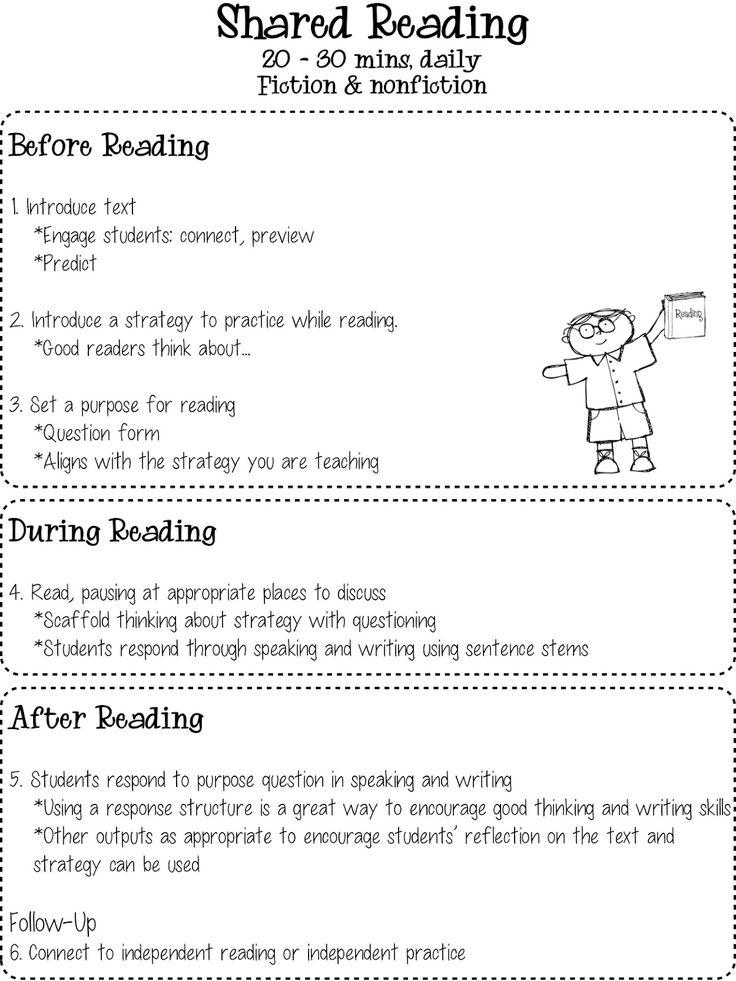

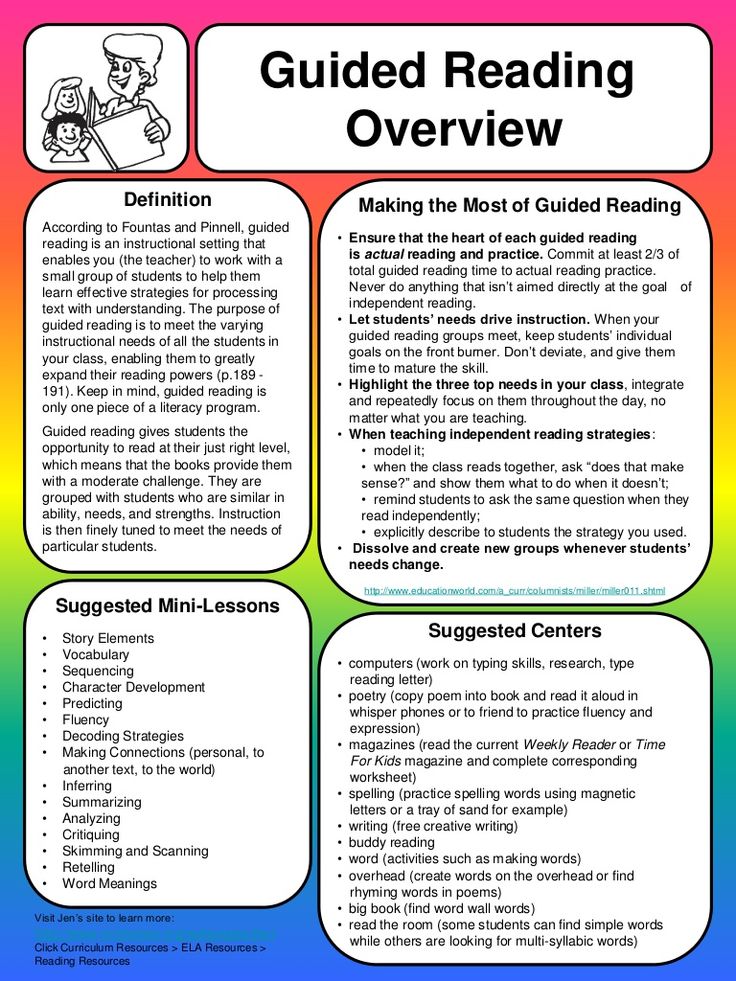

1. TEACHER THINK ALOUD

When reading aloud any piece of text, teachers can use a think aloud technique to model how good readers continually make predictions before, during, and after reading. This technique can be thoughtfully planned ahead before implementing, but is also effective to demonstrate often with any piece of text read aloud in class. Teachers can show how they piece together evidence from the text to pose predictions, as well as how they revise their predictions as they continue to read.

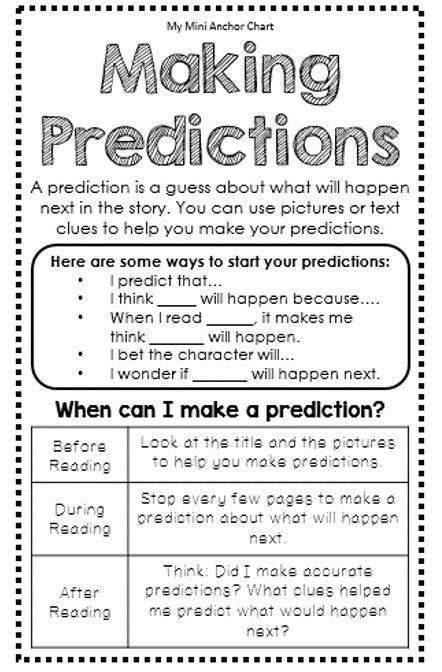

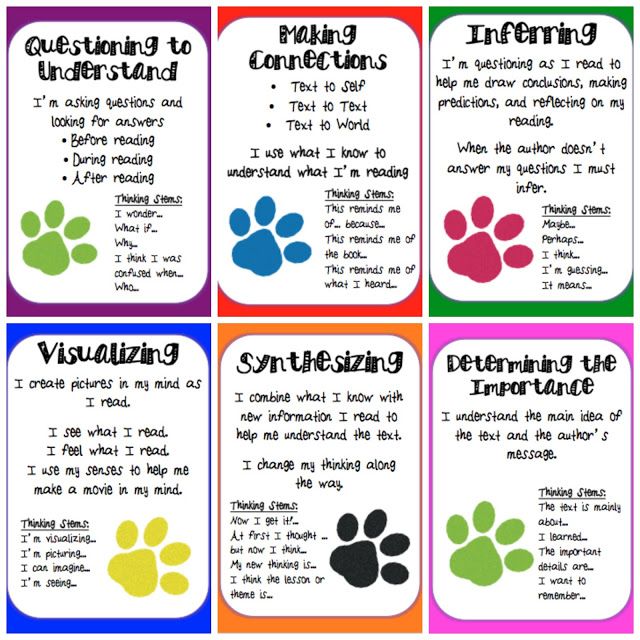

2. PROVIDE THINKING STEMS:

Giving students thinking stems is helpful to make using reading comprehension strategies more concrete. Offering 2 part thinking stems (i.e. “I think___because___”) is important with making predictions since they require students to have a clear reason to support their prediction.

Offering 2 part thinking stems (i.e. “I think___because___”) is important with making predictions since they require students to have a clear reason to support their prediction.

You can display these on an anchor chart or poster for the entire class to reference.

Some examples of thinking stems for fiction texts include:

“I think_____ will happen, because___”

“Next, I think the characters will___because___”

“I can predict that___because___”

“Since____ happened, I think___”

“Based on clues from the story, my guess is___”

Some examples of thinking stems for nonfiction texts include:

“Based on the title, I think the text will be about___”

“Based on the headings/subheadings, I think the text will be about”

“Because I know that_____, I predict that___”

“Based on what I know about _____, my guess is___”

You could also give students students their own individual reference sheet or bookmark.

3. INDIVIDUAL OR CLASS CRYSTAL BALL:

Students write their predictions on sticky notes and put them in the crystal ball on an anchor chart or white board. You can make the anchor chart re-usable by keeping it general with a question like “What do we predict will happen next?”

You can make the anchor chart re-usable by keeping it general with a question like “What do we predict will happen next?”

Students could also use their own crystal ball graphic organizer for a more detailed prediction.

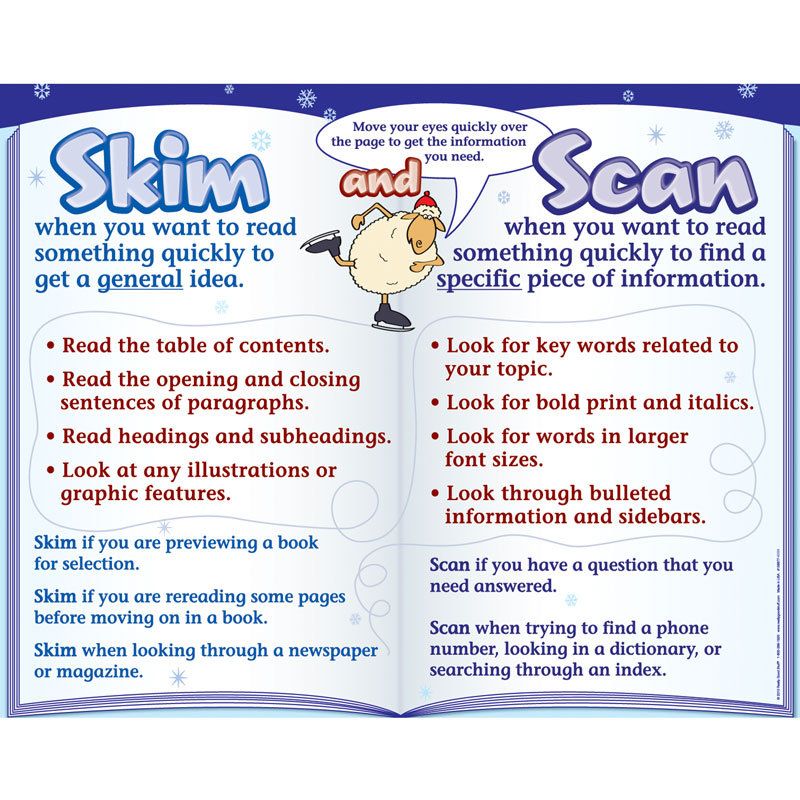

4. NONFICTION READING: MAKING PREDICTIONS BASED ON NONFICTION TEXT FEATURES

Students skim the text features of an informational text (table of contents, headings, images/captions, etc.) to make a prediction about the text. You could do this similar to a picture walk with students as a class, or have students complete this activity independently with their own informational texts.

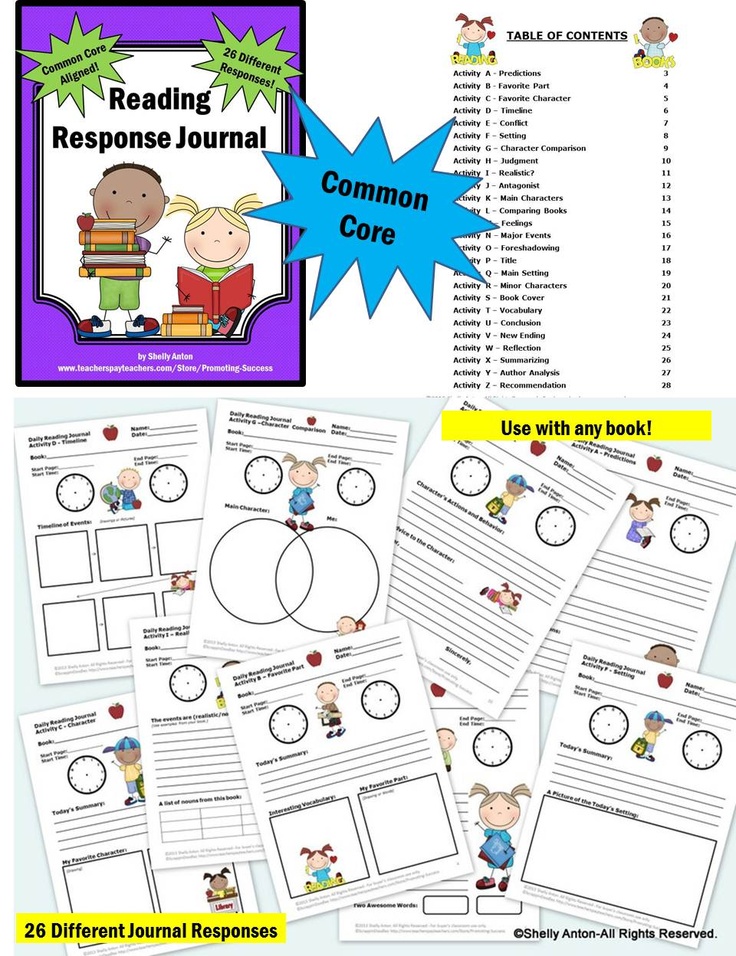

5. SUPPORTED INDEPENDENT READING RESPONSE:

Offering multiple ways that students use reading strategies independently can keep students engaged and help reach the many types of learners in a classroom.

It can sometimes be difficult to find a text to use for practicing a particular reading strategy. I like to first use these differentiated fiction and nonfiction passages specifically written for students to

use making predictions.

Then, students can apply what they have learned through these activities to any text. Graphic organizers can be a very powerful supportive tool for students to use while reading fiction or nonfiction.

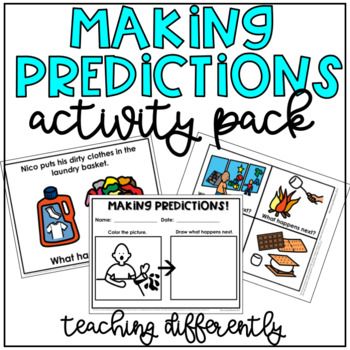

Below is also an example of Making Predictions Reading Strategy Crafts. They are similar to traditional graphic organizers, but the format really engages visual and hands-on learners.

All resources pictured in this blog post can also be found in the Making Predictions Reading Strategy Bundle!

Looking for more tips on teaching reading comprehension strategies? Check out this blog post: Teaching Students to Use Background Knowledge

90,000 probabilistic forecasting in the perception of information in the text Information gaps

Prediction of further text

Emotional reactions

Foreign language

Activity of the reader

Authority of the text

Selective mobilization of attention 9000 that everything is simple with reading: the author wrote or said something, the other person read or heard the text - and perceived the very information that the author of the message (text) wanted to convey. But in reality, everything is not so simple. Reading the same text, different readers extract very different information from it.

But in reality, everything is not so simple. Reading the same text, different readers extract very different information from it.

Information gaps

Who is not familiar with this situation. In a noisy airport hall, a person is waiting for the announcement of the arrival of the flight he needs. And here is a voice from the loudspeaker: “The plane arriving on flight number ( further - something illegible ) is late for ( and again illegible ) minutes.” What's the matter: why did a person understand all the words of the message well, but did not understand the most important words for him - the flight number and the length of delay? It is unlikely that the announcer uttered these words less clearly .. Such information gaps in the perception of the text is a common occurrence. Why were the rest of the words clearly understood despite the noise? Yes, because they were expected with a high probability. The perception of those words that were expected, predicted in advance by a person, is facilitated by this probabilistic forecast 1 .

The ability of a person to probabilistic prediction is what allows him to correctly perceive what he hears, despite the noise in the room, or the fuzzy articulation of the speaker, or defects in his own hearing.

The same applies to reading - visual perception of the text. Here, the role of a noisy factor can be the fuzziness of the font (even more so - written by hand), poor paper quality, poor lighting, etc.

Not only that. The perception of a "noisy" word can lead not only to its misunderstanding, but (even more dangerously) to a false understanding. For example, at a lecture, the professor said that the infection is carried by rodents, and less often by cats. And the student heard: "and red cats ." So I wrote it down in my notebook and remembered it that way.

So, speaking at a lecture something that is not expected, not predictable by the listener, one must be especially clear in articulation. Better yet, duplicate it on the screen. This is especially important when there are dates, little-known words, surnames, special terms, etc. in the oral text.

This is especially important when there are dates, little-known words, surnames, special terms, etc. in the oral text.

Prediction of further text

The ability to probabilistic forecasting allows the person reading the text to "look ahead", to predict the further development of information in the text. Already the title of a work of art sets the reader up and to some extent determines his perception of the text. Nekrasov's poem is read differently, whether it is called "Russian Women" or "Decembrists" (as it was originally with the author).

It is well known that the text read in the audience is perceived differently - whether the speaker reads from a written text or speaks "without paper". This is also connected with forecasting, with “looking ahead”. The intonation of the phrase uttered by the speaker depends on what will happen next in the text. Before the mental gaze of the speaker, speaking "without a piece of paper", is not what his language says, but the forthcoming part of the text. This is what gives the spoken text good expressiveness, bright intonations. When reading "on a piece of paper" it is impossible, or at least not necessary, to look ahead with the mind's eye. And reading becomes dull, inexpressive.

This is what gives the spoken text good expressiveness, bright intonations. When reading "on a piece of paper" it is impossible, or at least not necessary, to look ahead with the mind's eye. And reading becomes dull, inexpressive.

Let's take an example. The text contains a question asked by one person to another:

- Were you there yesterday?

Reading this phrase, you can place accents in different ways. Any of the four words of this phrase can be highlighted, and the meaning of the question changes. The answer to the question of which word to highlight intonationally becomes clear to the reader only further down the text - by what is the answer to the question. Here are four different answers (according to the number of words in the question):

- No, there was NN. (If the emphasis is on the word "you")

- No, I was sick. (If the emphasis is on the word "were")

- No, I was there the day before yesterday. (If the emphasis is on the word "yesterday")

- No, I was here. (If the emphasis is on the word "there" in the question)

(If the emphasis is on the word "there" in the question)

But since a person reading the text "on a piece of paper" may not "look ahead", the question will be read in gray, without an accent. If the speaker's mind's eye is ahead of his tongue, the reading of the question will be very clear, the question will sound quite definite.

Emotional reactions

The emotional reaction of a person is very essential for the perception of a text (both by sight and by hearing) and its memorization. What is read with a distinct affective reaction is better perceived and more firmly lodged in memory. One of the essential factors that cause an affective reaction is the mismatch between the probabilistic forecast of the reader and what the text tells him. This is the basis for the emotional impact of detective novels, most of the anecdotes. Their text is constructed in such a way that the reader forms a certain prediction of the further development of events, and then events develop in a completely different way than the reader predicted.

Poetry gives us many examples of how the author "collides" the reader's probabilistic forecast (formed by the author) with reality. Robert Burns has an epigram, which in Marshak's translation sounds like this:

No, he does not have a false look,

His eyes do not lie ...

They truthfully say,

That their owner is a rogue!

The emotionality of this quatrain is achieved only by the fact that the last word - "rogue" - collides with the reader's expectation of the previous text. Indeed, if you only say: “You can see in your eyes that you are a rogue,” there will be no emotional reaction. But Burns says just that. But as said!

The book by GGGranik et al. 2 convincingly shows the importance of probabilistic forecasting in reading. Summing up this issue, they write: “Without probabilistic forecasting, no reasonable human activity is possible, including the understanding of the text.” The title, the part of the text already read, the grammatical structure of the sentence - all this affects the probabilistic forecast of the reader.

The fact that the reader always "looks ahead", predicts the most probable continuation of the text, was well understood by Pushkin. In "Eugene Onegin" (Chapter 4, XLII) he wrote:

And the frosts are already cracking,

and are silvering in the middle of the fields ...

(the reader is waiting for rhyme rhyme;

on, take it soon!)

Foreign language

Very substantially probabilistic forecasting when teaching a foreign language (N. Krelenstein 3 ). In an insufficiently familiar foreign language, probabilistic forecasting is very difficult. Therefore, the legibility of the text should be particularly clear. Krelenshtein offers special exercises to train and improve students' probabilistic forecasting when reading in a foreign language.

Reader activity

Each text is addressed to someone. And if the author of the text had in mind a different addressee than the real reader, then the resulting text may be misunderstood or even misunderstood by him. The point is that perception is an active process . It is based not only on what has entered the brain from the sense organs. In addition to this sensory (receptor) component, an important role is played by the active component of perception, which is based on the knowledge of the reader, the orientation of his interests, his past experience (including language experience). As an example, I will give a reading of an excerpt from Pushkin's "Eugene Onegin". There is such a place (chapter 1, XVI):

The point is that perception is an active process . It is based not only on what has entered the brain from the sense organs. In addition to this sensory (receptor) component, an important role is played by the active component of perception, which is based on the knowledge of the reader, the orientation of his interests, his past experience (including language experience). As an example, I will give a reading of an excerpt from Pushkin's "Eugene Onegin". There is such a place (chapter 1, XVI):

Entered: and a cork in the ceiling.

The fault of the comet spurted current.

I witnessed how a schoolboy read, "correcting", as it seemed to him, a grammatical error in the text. He read: "Vina camet splashed current." He imagined a vivid picture: the bottle was uncorked, and the wine splashed out of it like a comet. But Pushkin addressed his poems not to this reader. The addressee of "Eugene Onegin" is a Petersburger of the 30-40s of the nineteenth century, this is a contemporary of Pushkin. Pushkin clearly names his reader already at the beginning of the novel:

Pushkin clearly names his reader already at the beginning of the novel:

Friends of Ludmila and Ruslan!

With the hero of my novel

Without preface, this very hour

Let me introduce you;

Onegin, my good friend,

Born on the banks of the Neva,

Where, perhaps, you were born,

Or shone, my reader.

And this reader - a Petersburger, a contemporary of Pushkin - knew perfectly well what "comet wine" was. In 1811, a comet with a tail was visible in the sky with the naked eye. The following year, she was remembered as a heavenly omen of Napoleon's invasion. And in the 30s, the wine of the rich harvest of 1811 was called “wine of the comet”. Comet wine is a good, old, aged wine. For the reader to whom Pushkin addressed his poems, this was understandable.

Each text created by its author is addressed to someone - a personal letter, a poem, and a story. Even a personal diary, which the author does not show to anyone, has an addressee - the author himself many years after writing.

Different readers perceive the same text differently. Reading Swift's Gulliver's Travels, the child perceives a funny tale about the country of the Lilliputians and the country of giants, and the thoughtful adult reader perceives a sharp satire on the English society of Swift's time, and even on a later society, which Swift did not even think about. Each reading of a book is an active and unique process. We usually do not notice this: after all, each person only knows about his reading of the book. But the variety of illustrations by different artists to the same text is evidence of this. After all, the artist, unlike the ordinary reader, makes his (the artist's) reading of the book visible to others.

So, it is important for the author of a text (both artistic, scientific, and business) to clearly imagine the addressee - the reader of this text. And the great works of art are those that allow the reader - including the reader of a much later time - to see in the text being read the problems that concern his time, problems that were unknown to the author who once wrote the text.

The activity of the author of the text

But it is also important for the reader to imagine the author of the text being read. Any text reflects not only what is described, but also reflects the author of the description. Two cameras shooting the same object at the same time from the same place will produce the same photographs. And two people observing the same events can give very different descriptions of that event. Which one is correct? Yes, both can be correct. The poem "The Twelve" - a true description of events 1917 years in Russia, seen through Blok's eyes. And "Days of the Turbins" - through the eyes of Bulgakov. And the requirement to give an "objectively correct" description does not make sense. Blok sees one thing as objective, Bulgakov another.

The same is true in scientific literature. The great naturalist Isaac Newton, looking at the fall of an apple, saw (and described) the manifestation of universal gravitation. And a humanist or a poet, looking at an apple falling from a tree, sees a reminder that not only in nature, but sometimes in society an apple does not fall far from an apple tree . “Looking” and “seeing” are not the same thing at all! Big scientist, looking at . it would seem that. things that are insignificant and open to the gaze of any person, sees the previously unknown Law of Nature. The joke "Looks at figure - and writes Book " admits such an understanding.

“Looking” and “seeing” are not the same thing at all! Big scientist, looking at . it would seem that. things that are insignificant and open to the gaze of any person, sees the previously unknown Law of Nature. The joke "Looks at figure - and writes Book " admits such an understanding.

So, it is important for the reader to imagine the author of the text being read, and also to whom the author addressed the written text 4 .

Selective attention mobilization

The method of selective (selective) mobilization of attention developed by us together with V.L. It is based on the circumstance that for different readers of a book or different listeners of a lecture, different parts of the text presented may be especially important. Particularly important to the reader are those places in the text where new (new to him) material is presented that is at odds with the concepts of this reader or listener. According to this method Before presenting certain material in a lecture, the audience is asked a question related to this material, and several answers to this question are offered. Listeners respond with colored cards so that the listener's answer is visible only to the lecturer and invisible to other listeners. All this takes only a few minutes. The listener, whose answer differs from the presentation of the lecturer, turns out to be more attentive, listens with affect (Pavlov's “what is it?”). Another listener who gave the correct answer (coinciding with the lecturer's opinion) may be calmer and less stressful. Thus, in different places of the presentation of the material, those listeners for whom this particular place of presentation is essential turn out to be especially attentive. After all, their a priori opinion (before presenting the material) and predicting the correct answer turned out to be in conflict with the answer proposed by the lecturer. Therefore, we called this method the method of selective attention mobilization.

According to this method Before presenting certain material in a lecture, the audience is asked a question related to this material, and several answers to this question are offered. Listeners respond with colored cards so that the listener's answer is visible only to the lecturer and invisible to other listeners. All this takes only a few minutes. The listener, whose answer differs from the presentation of the lecturer, turns out to be more attentive, listens with affect (Pavlov's “what is it?”). Another listener who gave the correct answer (coinciding with the lecturer's opinion) may be calmer and less stressful. Thus, in different places of the presentation of the material, those listeners for whom this particular place of presentation is essential turn out to be especially attentive. After all, their a priori opinion (before presenting the material) and predicting the correct answer turned out to be in conflict with the answer proposed by the lecturer. Therefore, we called this method the method of selective attention mobilization.

Physiology of activity

The question of reading and perception of the text of oral speech, which is very relevant for pedagogy, is part of a wide range of ideas about the higher nervous activity of a person, about the psychophysiology of perception. René Descartes (1596-1650) was the first to draw attention to the fact that the actions of an animal and a person can be considered as a response to some external influence on the body.

This observation of Descartes was the beginning of a long and productive development of the reflex theory, which dominated for more than 300 years. This theory is based on the idea that the action of an animal and a person is the result of a certain stimulus on receptors, from which nervous excitation passes along the reflex arc to the effector, to the muscles, the contraction of which implements the action. Reflex arcs are embedded in the very structure of the nervous system.

IP Pavlov drew attention to those actions of the body that are not innate, but are developed individually under certain conditions. Standing firmly on the positions of the reflex theory, Pavlov called these actions conditioned reflexes, the reflex arc of which is formed in the nervous system under certain conditions. However, with further study of conditioned reflexes, more and more contradictions began to come to light. They manifested themselves especially clearly in the study of the higher nervous activity of man, in which speech plays a leading role. The idea of a second signaling system arose in Pavlov's school. Persistent attempts (in the 1940s and early 1950s) to canonize Pavlov's ideas led to a dead end. In the history of science, it happened more than once that the canonization of even progressive views for their time turned out to be a brake on science in the future.

Standing firmly on the positions of the reflex theory, Pavlov called these actions conditioned reflexes, the reflex arc of which is formed in the nervous system under certain conditions. However, with further study of conditioned reflexes, more and more contradictions began to come to light. They manifested themselves especially clearly in the study of the higher nervous activity of man, in which speech plays a leading role. The idea of a second signaling system arose in Pavlov's school. Persistent attempts (in the 1940s and early 1950s) to canonize Pavlov's ideas led to a dead end. In the history of science, it happened more than once that the canonization of even progressive views for their time turned out to be a brake on science in the future.

As an alternative to reflex physiology, activity physiology , brilliantly developed by N.A. Bernstein , arose. The animal is not a reactive being, reflexively responding to external influences, but an active being, having its own needs, goals, to achieve which its actions are directed. The action is preceded by the emergence of what Bernstein called the image (or model) of the required future. If the paradigm of reflex physiology dealt only with the past and the present (cause and effect), then the physiology of activity included in the consideration of physiology and the future - the goal that must be achieved by actions, the planning of these actions. Problems of physiology and psychology have closed.

The action is preceded by the emergence of what Bernstein called the image (or model) of the required future. If the paradigm of reflex physiology dealt only with the past and the present (cause and effect), then the physiology of activity included in the consideration of physiology and the future - the goal that must be achieved by actions, the planning of these actions. Problems of physiology and psychology have closed.

The bit of activity physiology that I had the opportunity to develop was called probabilistic prediction . It is based on the idea that, relying on his individual past experience - more precisely, on the probabilistic structure of past experience - a person is able to predict, foresee the most likely path for the further development of a dynamic situation and prepare for adequate actions ahead of time, without waiting for this situation to arise. Changing the situation does not take the body by surprise. He is ready for it in advance and therefore meets it, having already prepared for action. From here - both the big speed of action, and its big profitability. If the upcoming situation is predicted with a very high probability (close to 100%), then the body reacts not only by preparing for action (presetting), but fully deploys activities that are adequate to the upcoming situation (outstripping the development of external events). The classical procedure for developing a conditioned reflex in Pavlov's school is precisely such that the animal is placed in artificial conditions in which the future is unequivocally predicted. A conditioned reflex is not a “reflex” (an action in response to what has already happened), but an anticipation of the situation - an action that is adequate to what should come, more precisely, to what is predicted as the most probable.

From here - both the big speed of action, and its big profitability. If the upcoming situation is predicted with a very high probability (close to 100%), then the body reacts not only by preparing for action (presetting), but fully deploys activities that are adequate to the upcoming situation (outstripping the development of external events). The classical procedure for developing a conditioned reflex in Pavlov's school is precisely such that the animal is placed in artificial conditions in which the future is unequivocally predicted. A conditioned reflex is not a “reflex” (an action in response to what has already happened), but an anticipation of the situation - an action that is adequate to what should come, more precisely, to what is predicted as the most probable.

Memory and probabilistic forecasting

Probabilistic forecasting is based on individual memory. It seems to me that probabilistic forecasting is the most important function of memory . Memory is a function directed not to the past, but to the future. To do this, it uses probabilistically organized information about the past. In the process of evolution, memory was formed precisely as a function useful to the body, providing probabilistic forecasting and preparation for actions adequate to the upcoming (more precisely, predicted as the most probable) situation. My monograph "Probabilistic Forecasting in Human Activity and Animal Behavior" is based on this idea. It also outlines the structure of memory that provides probabilistic forecasting.

Memory is a function directed not to the past, but to the future. To do this, it uses probabilistically organized information about the past. In the process of evolution, memory was formed precisely as a function useful to the body, providing probabilistic forecasting and preparation for actions adequate to the upcoming (more precisely, predicted as the most probable) situation. My monograph "Probabilistic Forecasting in Human Activity and Animal Behavior" is based on this idea. It also outlines the structure of memory that provides probabilistic forecasting.

Conclusion

It is on these positions of the physiology of activity that our ideas and recommendations in training are based. The reader and listener perceive the text actively. And this perception is different for different readers. Many factors influence his perception of the text. Here are the interests of the reader, and his knowledge on this topic, as well as about the author, about the author's attitude to what is described in the text, and the reader's idea of \u200b\u200bwho the author addressed the text to.

---------------------------------------------- -------------

1 Feigenberg I.M. Probabilistic forecasting in human activity and animal behavior. Ed. Newdiamed, Moscow 2010.

2 Granik G.G., Kontsevaya L.A., Bondarenko S.M. When the book teaches Moscow, 1991.

3 Krelenstein N. Probabilistic Prediction in Teaching and Mastering Foreign Language. In: 10th European Conference on Learning and Instruction. Padova, Italy, August 26-30, 2003, p.141.

4 Feigenberg I.M. We learn all our lives. Ed. "Meaning", Moscow, 2008. (Chapter "The observed and the observer - two things are inseparable").

5 “Probabilistic forecasting and memory in learning activities”. In: Probabilistic Forecasting in Human Activity and Animal Behavior. Moscow, 2008.

6 Bernstein N.A. Physiology of movements and activity. Ed. Nauka, Moscow, 1990. (In the Classics of Science series).

Popular about the life and work of Bernstein is described in the book: Feigenberg I.M. Nikolay Bernshtein - from a reflex to a model of the future. Ed. Smysl, Moscow, 2004.

Popular about the life and work of Bernstein is described in the book: Feigenberg I.M. Nikolay Bernshtein - from a reflex to a model of the future. Ed. Smysl, Moscow, 2004.

Submitted by the author on September 26, 2011

for discussion at the seminar

Reading as one of the ways of teaching English Text of a scientific article in the specialty "Linguistics and Literary Studies"

UDK 372.ss1.111.1

-2019-1-110-114

READING AS ONE OF THE WAYS OF TEACHING ENGLISH

E.G. Zheleznova

Southern Institute of Management, Krasnodar, Russian Federation

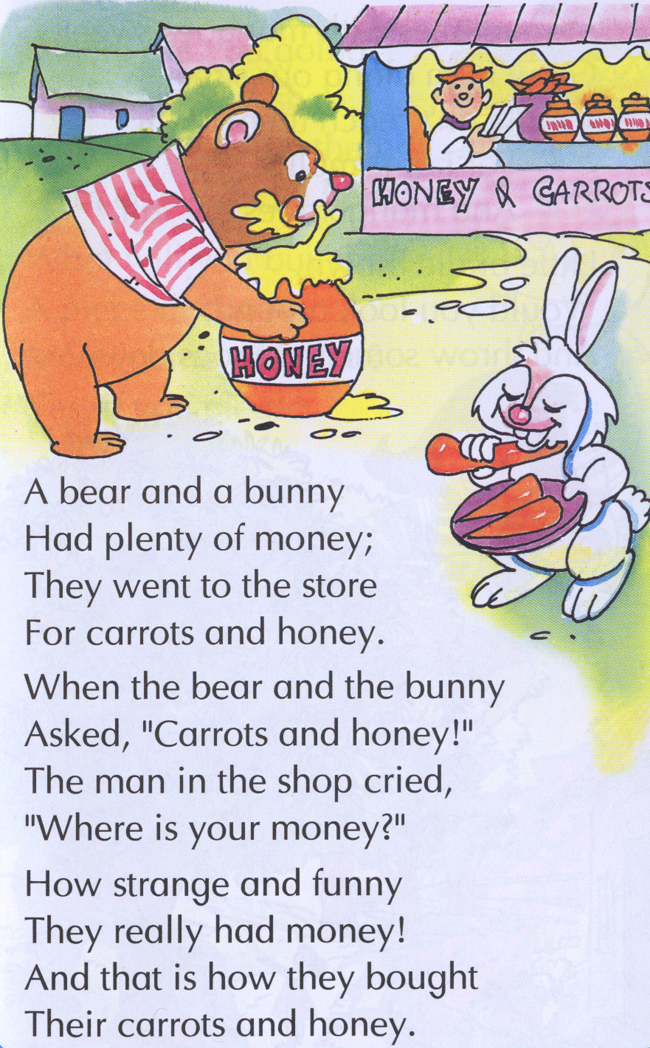

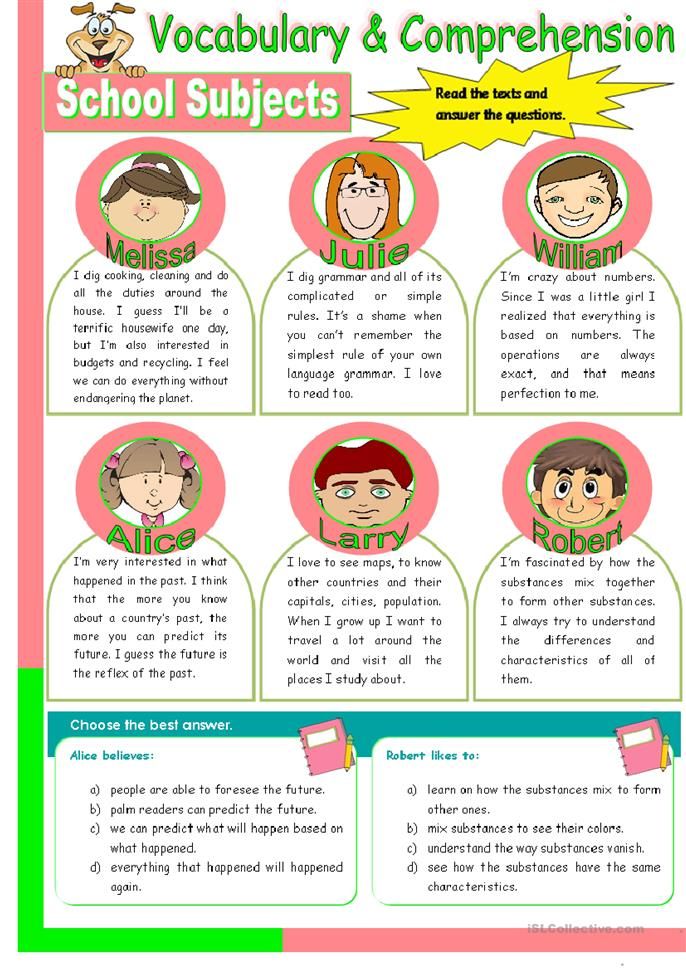

Abstract. English is currently considered one of the most famous and widespread languages in almost all countries in the world. The ever-growing need for fluency in English around the world has led to the fact that scientists - linguists, teachers give priority to finding more effective ways to teach language skills, one of which is reading. Possessing this type of communicative activity, a person understands everything that he reads and adequately reacts to what he read, converting his thoughts into a response. Reading any text in a foreign language and answering questions about the text or expressing his opinion about what he read, the student masters the skills of monologue speech. The speech feature of reading as a type of communicative activity plays a special role at various stages of mastering the English language, which is why every modern English teacher must include reading tasks in his lesson. In this article, the author considers the importance of reading in learning and teaching English or any other foreign language, presents approaches to teaching reading that can be used when reading and parsing any text, introduces various strategies for teaching reading, and also describes common ways to teach students to read. in the classroom. Keywords: reading, reading strategy, methods of teaching reading, types of reading For citation: Zheleznova E.G. Reading as one of the ways of teaching English // Scientific Bulletin of the Southern Institute of Management. 2019. No. 1. pp. 110-114. https://doi.

Reading any text in a foreign language and answering questions about the text or expressing his opinion about what he read, the student masters the skills of monologue speech. The speech feature of reading as a type of communicative activity plays a special role at various stages of mastering the English language, which is why every modern English teacher must include reading tasks in his lesson. In this article, the author considers the importance of reading in learning and teaching English or any other foreign language, presents approaches to teaching reading that can be used when reading and parsing any text, introduces various strategies for teaching reading, and also describes common ways to teach students to read. in the classroom. Keywords: reading, reading strategy, methods of teaching reading, types of reading For citation: Zheleznova E.G. Reading as one of the ways of teaching English // Scientific Bulletin of the Southern Institute of Management. 2019. No. 1. pp. 110-114. https://doi. org/10.31775/2305-3100-2019-1-110-114

org/10.31775/2305-3100-2019-1-110-114

No conflict of interest

READING AS A WAY OF TEACHING ENGLISH

Elena G. Zheleznova

Southern Institute of Management, Krasnodar Russian Federation

Abstract. English is one of the most widely spoken languages in almost all countries of the world. The evergrowing need for fluency in English throughout the world has led linguists and teachers to prioritize the search for more effective ways of teaching language skills, one of which is reading. Owning this type of communicative activity, a person understands everything he reads, and responds adequately to what he has read, converting his thoughts in response. Reading any text in a foreign language and answering questions about the text or expressing their opinion about the read, the student learns the skills of monologue speech. The speech feature of reading as a type of communicative activity plays a special role at various stages of mastering the English language, which is why every modern teacher or English teacher necessarily includes reading tasks in his lesson. In this article, the author considers the importance of reading in the study and teaching of English or any other foreign language, presents approaches to teaching reading that can be used in reading and parsing any text, introduces various strategies in teaching reading, and describes common ways of teaching reading to students in the classroom.

In this article, the author considers the importance of reading in the study and teaching of English or any other foreign language, presents approaches to teaching reading that can be used in reading and parsing any text, introduces various strategies in teaching reading, and describes common ways of teaching reading to students in the classroom.

Keywords: reading, reading strategy, methods of teaching reading, types of reading

For dtation: Zheleznova E.G. Reading as a way of teaching English. Scientific Bulletin of the Southern Institute of Management. 2019; (1): 110-114. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.31775/2305-3100-2019-1-110-114

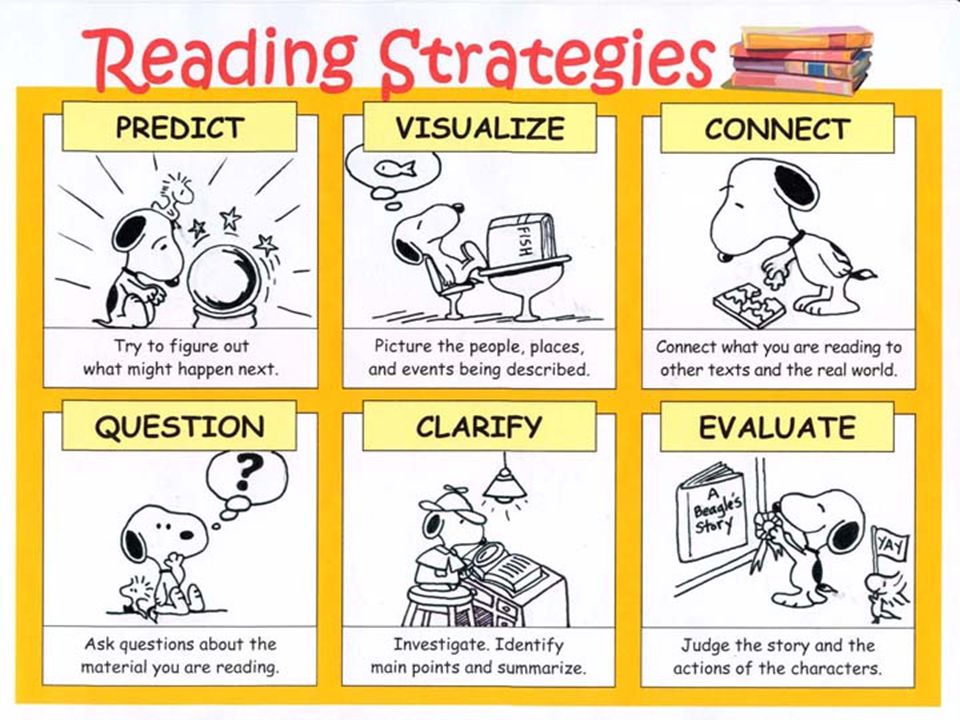

give the following definition of the term "reading" - the relationship between the reader and the text. Language scientists believe that mastering such a communicative skill as reading requires extensive and versatile knowledge about the world and about a given topic, as well as perfect knowledge of the language. According to linguists-educators, reading requires extensive background or, as they are called, basic knowledge, as well as certain skills and abilities in order to understand texts.

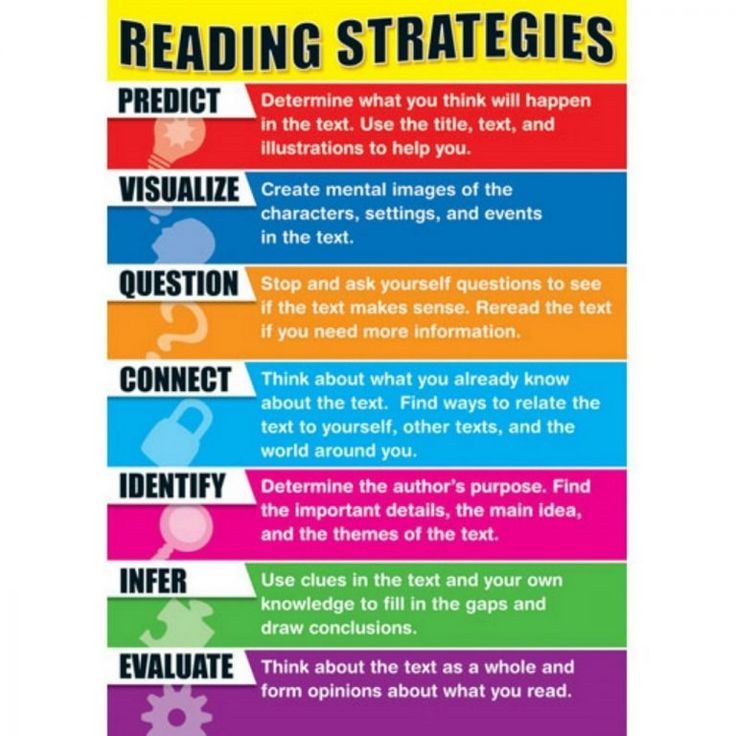

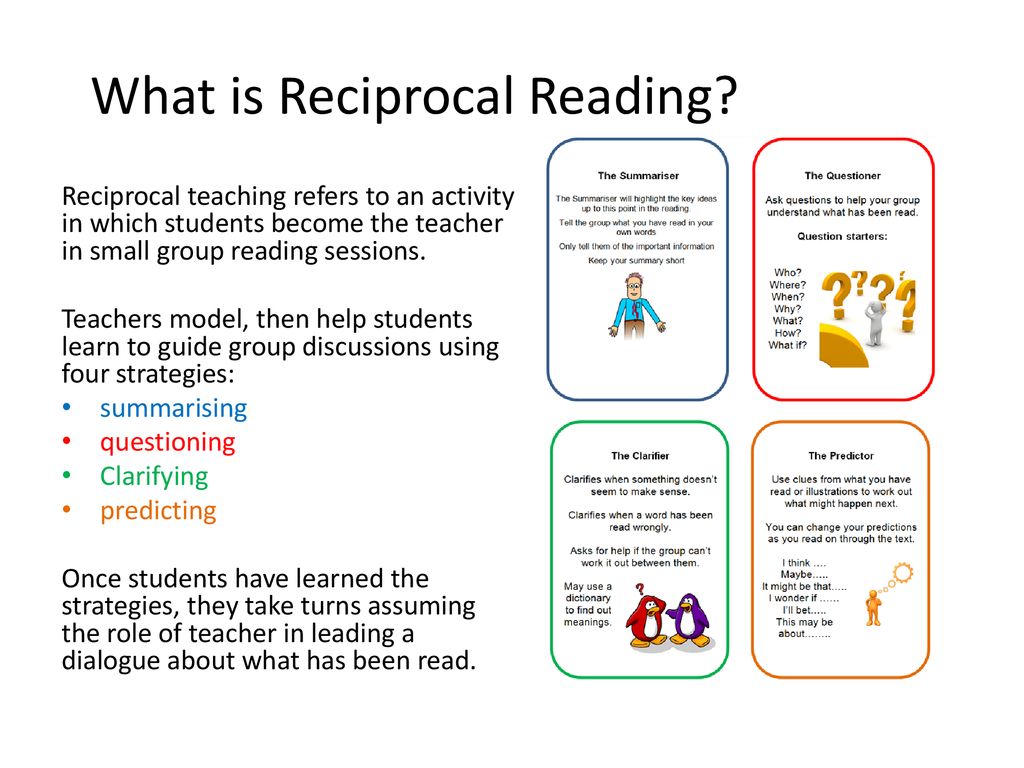

In addition, other scholars agree that good readers must perform some other activity in order to understand a text: they must associate new text with past experience or, as it can be called, basic knowledge, namely, interpret, evaluate, synthesize and consider alternative interpretations. When performing this task, students should also know some strategies that can help them easily understand reading comprehension [1].

Reading is one of the four fundamental skills in learning English or any other language, and is also considered one of the most difficult skills for a person who learns a foreign language.

As in listening, there are bottom-up and top-down approaches to teaching reading. In a bottom-up approach, the reader assembles letters to form words, sentences, sentences, and paragraphs in order to capture meaning. Thus, at the same time, reading activity is carried out according to the structure of the text, which is read by students studying the language. According to Carrell, bottom-up text processing structures the meaning of the text from the smallest units of the language to the largest, and then changes the learner's existing basic knowledge and his predictions about the text based on the information that occurs in the text [1]. According to Miller, the bottom-up approach, or as it is also called, bottom-up processing, helps students become fast and good readers, but, on the other hand, without effective knowledge of the second language, this processing will not be successful [1].

According to Carrell, bottom-up text processing structures the meaning of the text from the smallest units of the language to the largest, and then changes the learner's existing basic knowledge and his predictions about the text based on the information that occurs in the text [1]. According to Miller, the bottom-up approach, or as it is also called, bottom-up processing, helps students become fast and good readers, but, on the other hand, without effective knowledge of the second language, this processing will not be successful [1].

On the other hand, other researchers are focusing on a top-down, top-down, or top-down approach as it is also called. This approach encourages students to use their accumulated knowledge up to the moment of reading in order to make predictions about the texts they have read. When reading in English or a foreign language, the reader,

applying the top-down approach, is not only an active participant in the reading process, predicting and processing textual information. Knowledge accumulated by readers, or basic knowledge, plays a significant role in teaching reading. Miller, in his study on teaching reading, presents certain strategies for teaching reading [1]. He argues that reading was based on top-down skills some forty years ago, with learners' primary concern in using their background knowledge to improve reading comprehension. However, there has recently been a shift from bottom-up skills to top-down skills; it primarily focuses on a precise, literal understanding of the text [5].

Knowledge accumulated by readers, or basic knowledge, plays a significant role in teaching reading. Miller, in his study on teaching reading, presents certain strategies for teaching reading [1]. He argues that reading was based on top-down skills some forty years ago, with learners' primary concern in using their background knowledge to improve reading comprehension. However, there has recently been a shift from bottom-up skills to top-down skills; it primarily focuses on a precise, literal understanding of the text [5].

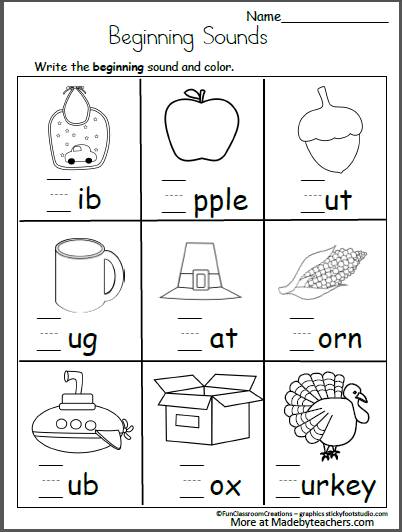

Other researchers have found that students used different reading strategies and approaches in their research. In the first stages of learning, students use a dictionary while reading, try to memorize or memorize words, take notes and translate word for word. At a later stage of learning, having the necessary skills and abilities, they guess the meanings of the words contained in the text from the context. At the final stages, students use strategies such as "use of transitional words", "search for clues in the text" and the use of accumulated and background knowledge [2].

Reading skills are often confused with strategies in teaching reading. Reading skill is defined as a tool a student uses to improve their ability to read. Unfortunately, many students do not understand what they are reading.

A reading strategy is a plan or a way to do something; a specific procedure used to perform a skill.

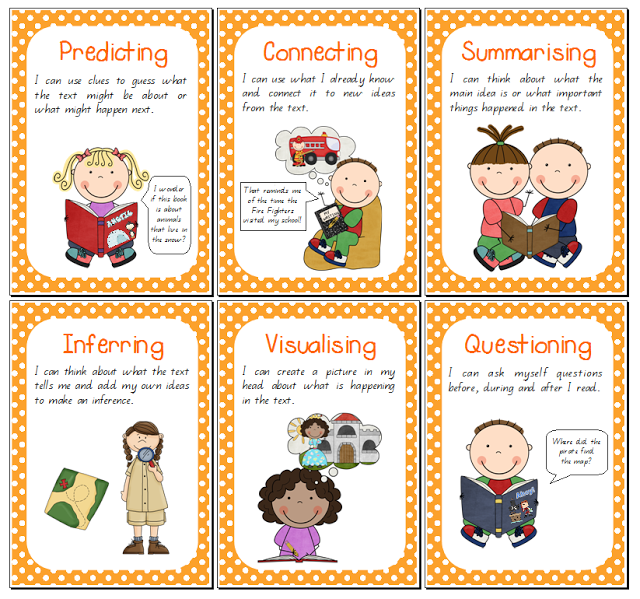

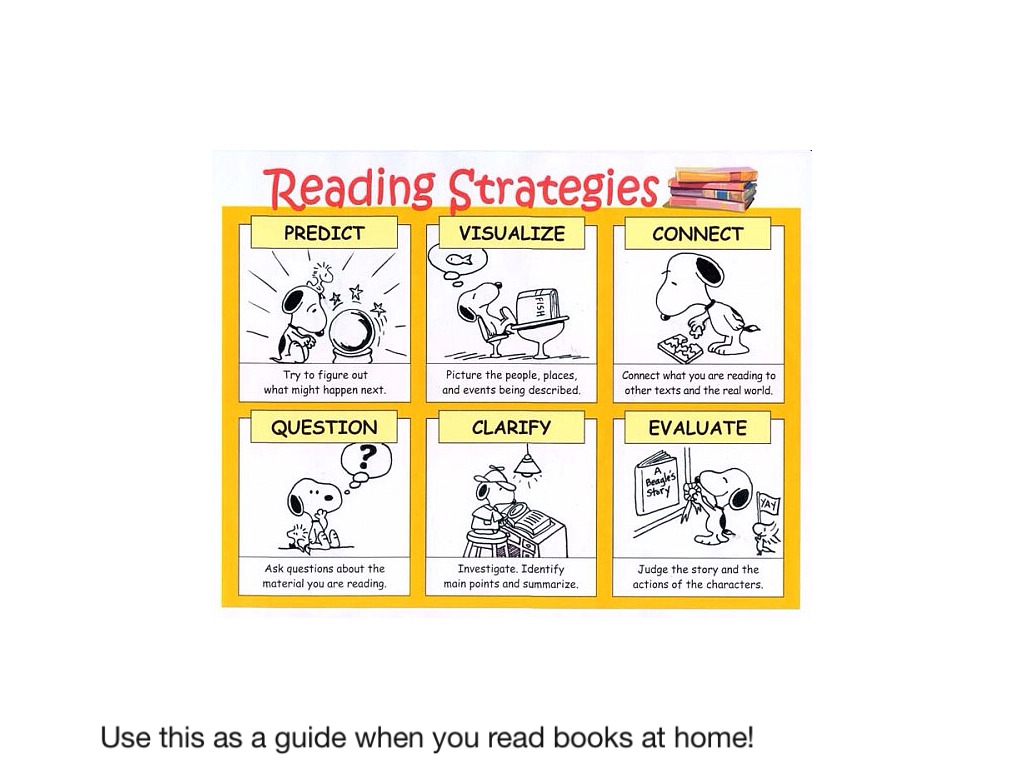

For example, students have difficulty completing a short reading task, such as a newspaper article. This difficulty is related to the lack of ability to focus and concentrate on the written words. Because of this, many students need guidance and strategies to help them focus on reading and do more than just read words on paper. The content skills of a strategic reader can be broken down into seven areas, namely:

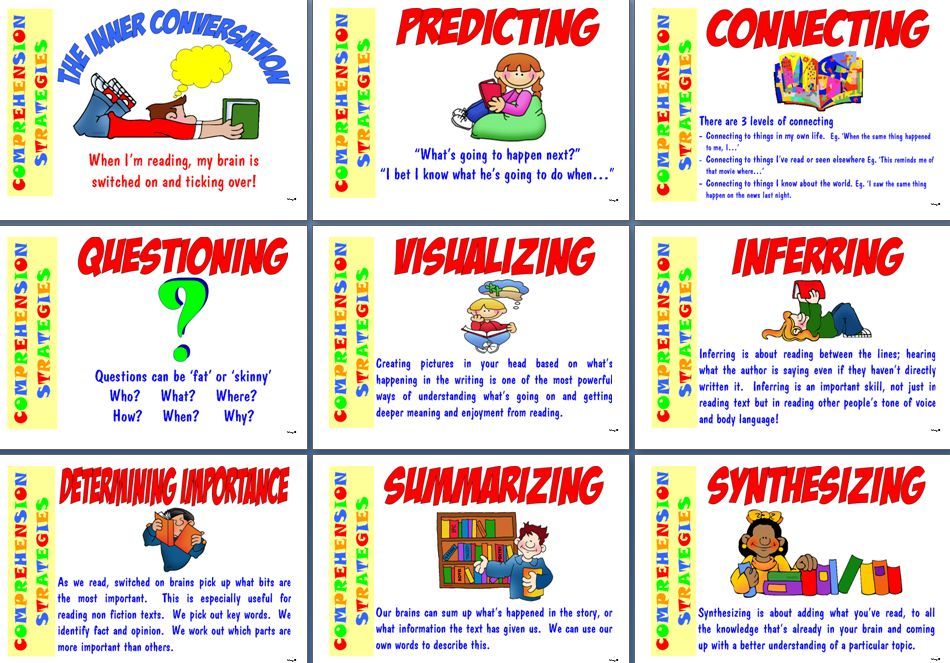

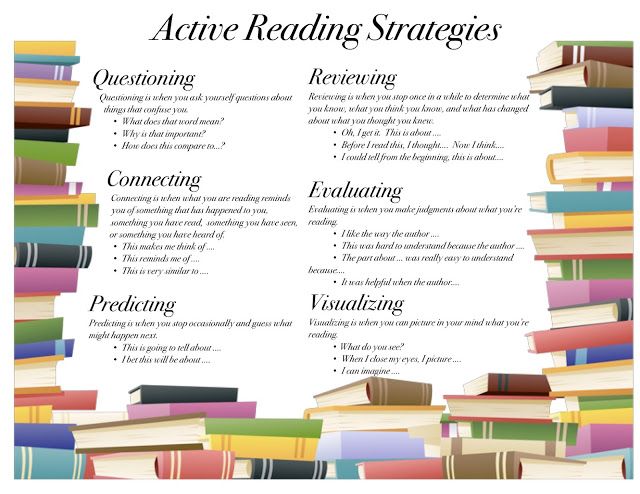

1. Forecasting - prediction based on observations and/or personal experience.

2. Visualization - the formation of mental images of scenes, characters and events.

3. Linking - linking two or more things together or seeing the connection while reading the text.

4. Question - asking or considering.

5. Clarification - to make clear or to become clear and free from confusion.

6. Summarization - concisely define the essence of the text.

7. Evaluation - to form an opinion about what has been read [1].

In order to develop English reading skills, linguists offer the teacher the following strategy - to teach students to focus on the text itself, and not on the sentences in it. To understand most of what you read, you need to learn to understand the structure of such long units, such as a paragraph or an entire text. To do this, it is necessary to start with a global understanding of the text and move towards a detailed understanding, and not vice versa, the learner also needs to use authentic text when possible. Authentic text does not make learning more difficult. Difficulty depends on the activity that is required of students, and not on the text itself. In other words, the teacher should evaluate the assignments he gives for reading, not the reading itself;

- should focus on reading skills and learning strategies and plan comprehension exercises for each of them;

- Do not force your own interpretation on students. They should be taught to think by providing sufficient evidence to enable them to follow the right path;

They should be taught to think by providing sufficient evidence to enable them to follow the right path;

- should not be superimposed on the text of the exercise. You don't have to use a lot of exercise to spoil the pleasure of reading.

- help students increase their reading speed.

- different procedures must be used when managing a student's reading. Self-correcting exercises are extremely beneficial [4].

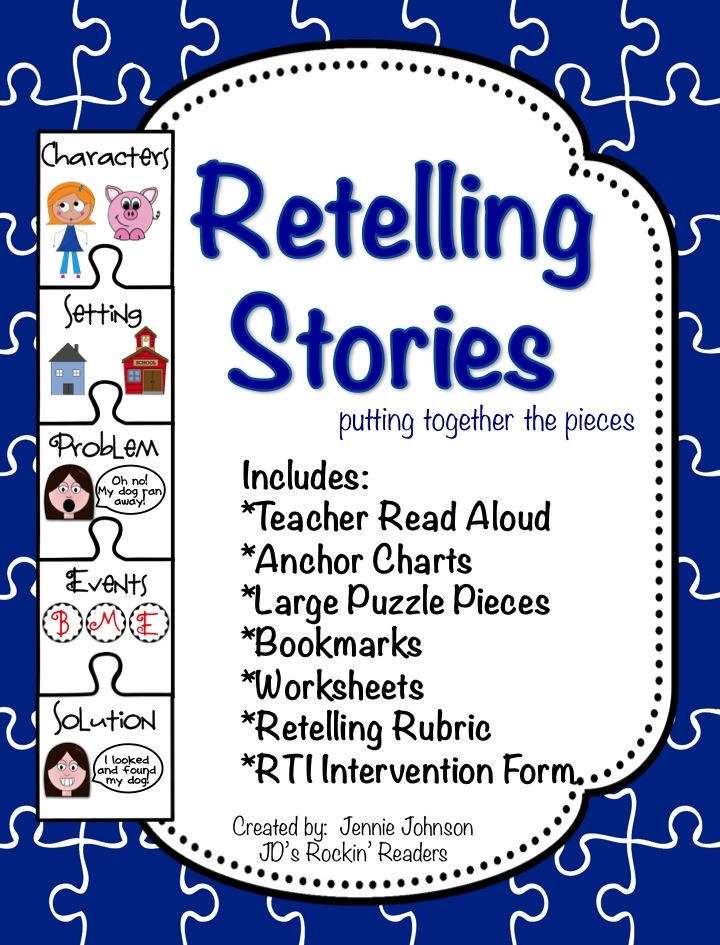

There are many strategies in teaching reading that many researchers believe are very important. It is difficult to decide which strategies are the most significant. But some of the most effective scientists identify the following: the challenge of the relevant basic knowledge; predicting what will be learned and what will happen; creating mental images; self-control and self-correction; using corrective strategies such as rereading or seeking help; identifying the most important ideas and events and observing how they are connected; the ability to draw conclusions, justify your opinion; compare and contrast what is read and background knowledge, find out unknown words, summarize what has been read [1].

As mentioned earlier, one of the most important preconditions for reading is background knowledge. Scholars argue that knowledge is an essential component of reading comprehension. Various studies have shown that the amount of a reader's prior knowledge can be a very strong determinant of how much the reader can understand the text they are reading. The accumulated knowledge helps students interpret reading materials personally, on an individual basis. Thus, it is necessary for teachers to teach students how to use their own basic knowledge when reading a text as a strategy for its text. A student with strong background knowledge will have a better ability to understand and represent what the author is trying to portray in the text. Thus, it can be argued that a strong prior knowledge base has a very strong effect on how well the reader will understand the text.

When students make predictions, they decide their reading goals. Text prediction interacts closely with background knowledge. Using their background knowledge, students figure out or predict what will happen next. In addition, they are engaged in making predictions before reading, first relying on basic knowledge. By applying this strategy, students are given the opportunity to integrate what they know while reading, as well as being exposed to new information that may conflict with their own assumptions, which in turn can strengthen critical thinking skills [3].

Using their background knowledge, students figure out or predict what will happen next. In addition, they are engaged in making predictions before reading, first relying on basic knowledge. By applying this strategy, students are given the opportunity to integrate what they know while reading, as well as being exposed to new information that may conflict with their own assumptions, which in turn can strengthen critical thinking skills [3].

In self-monitoring or self-correction, students demonstrate the ability to recognize that what they are reading does not make sense and apply various strategies to deal with this problem. When a student comes across an unfamiliar word while reading, he needs to decide whether to reread the sentence, read on, voice the word, or look it up in a dictionary.

Identifying the main events or ideas in a text is something students with reading skills should do. They should constantly look for ideas in the text they are reading and identify the main points in each section of the reading. In addition, students have the opportunity to learn and discuss the main events taking place in the text. In addition, these readers also have the ability to ignore information that is not important.

In addition, students have the opportunity to learn and discuss the main events taking place in the text. In addition, these readers also have the ability to ignore information that is not important.

Summarization is a strategy that many students have difficulty applying. It is very closely related to the previous strategy

. This strategy is important because it helps them build an information base. Scholars define generalization as: removing unnecessary and unimportant information, dividing information into groups, finding and using the author's main ideas, and compiling and explaining one's own main idea if the author of the text did not clearly formulate the idea.

Drawing conclusions and asking questions is another strategy that learners often describe as boring and uninteresting. Perhaps this point of view is due to the fact that students are used to their teachers themselves asking them questions, and not vice versa. But if teachers ask all questions about the text, students will not become strategic readers. Instead, they need to learn to ask themselves questions while reading. This strategy leads to a more complete understanding of the text [1].

Instead, they need to learn to ask themselves questions while reading. This strategy leads to a more complete understanding of the text [1].

The reading teaching strategies outlined above can be applied to teaching reading in English. As students become more competent readers they, in turn, become more motivated to learn the language. According to linguist research, motivating students to learn is extremely complex and continues to challenge researchers with its conceptualization and re-conceptualization, and incorporation and operationalization into interventional research. In addition, research has shown that learning motivation should be seen as a concept that is intertwined with learning strategy. Thus, students, in order to become strategic, self-regulating readers, must also be attracted by readers [1].

Linguists have developed many fairly effective methods of teaching reading that teachers can use to motivate students to focus on either one or more reading strategies. When reviewing most of the literature in this area, there are many examples of lessons. Let's briefly consider some of them that are especially useful and can be easily applied in the classroom.

When reviewing most of the literature in this area, there are many examples of lessons. Let's briefly consider some of them that are especially useful and can be easily applied in the classroom.

I. Procedural hints.

Procedural prompts can be used to help students generate questions and be able to summarize what they have read. Linguists argue that this should be the first step in teaching students about cognitive strategies. It is procedural prompts that serve to develop the basic knowledge of students and provide support for knowledge,

which they can use. For example, to compose questions about a narrative text, teachers recommend that teachers and students give or formulate clues that are based on the grammar of the text itself:

- Who are the main characters?

- What problem did the main character face?

- What attempts were made to solve the problem?

- How was the problem finally solved?

- What is the theme of the story?[2].

II. Text discussion.

In order to teach students how to use different reading strategies, teachers should use 'activities' such as discussion to encourage students to relate the topic of the text to their own experience. Since learners of reading cannot retell or recount all the events that occur in a text, teachers should help students understand the meaning of the text they are reading using their own background knowledge. An effective way to encourage students to turn to background knowledge is to engage them in discussion before reading. At 19In 1996, scholars explored ways to use informative text through discussion. They looked at research from experienced readers who analyzed conversations about themselves before, during, and after reading. It was found that these readers have the ability to better comprehend the ideas in the text, make predictions and hypotheses using previously acquired knowledge, and are able to critically evaluate what they read.

First, individual students silently read the highlighted text. They are then given four value statements that are relevant to reading choice and possibly controversial. They are then asked to write down how the other members of the group would react. Finally, students are regrouped to compare predictions and should challenge and support each other's answers by supporting arguments using textual information and prior knowledge. In addition, this exercise allows students to control their understanding and check the accuracy of their predictions [3].

They are then given four value statements that are relevant to reading choice and possibly controversial. They are then asked to write down how the other members of the group would react. Finally, students are regrouped to compare predictions and should challenge and support each other's answers by supporting arguments using textual information and prior knowledge. In addition, this exercise allows students to control their understanding and check the accuracy of their predictions [3].

III. W and H (who, what, when, where, why and how).

To teach students how to generate questions or make predictions, scientists suggest using a strategy called the 5 S&N. During class, the teacher asks students questions before they read the passage. First, she or he models questions, literal or logical. The students should then read the passage looking for answers. Students

are then divided into small groups or pairs and asked to create their own questions, which they will later share with other students. When applying this strategy, it is necessary to first teach students to distinguish between questions that require one-word answers and questions that require more detailed answers [3].

When applying this strategy, it is necessary to first teach students to distinguish between questions that require one-word answers and questions that require more detailed answers [3].

Scientists - linguists distinguish the following types of reading:

Reading. This type of reading can be defined as the activity of "skimming" and scanning. For others, it is the amount of material read.

Home reading. In this type of activity, the teacher selects material for reading, then this material is read by students at home.

Extensive reading. This type of reading is an individual lesson of the student, which can be not only in the classroom, but also at home. In this activity, students may be allowed to choose their own reading materials according to their interests and language level.

Intensive reading. This type of reading is associated with short texts used by students to learn the language. They are used in the study of lexical, syntactic or discursive aspects of the target language [1].

REFERENCES

1. Birkner V. Reading Comprehension in Teaching English as a Foreign Language [Internet]. Available from: https://www.monografias.com/trabajos68/readins-comprehension-teaching-english/readins-compre-hension-teaching-english3.shtml

2. Gordeeva I.V. Reading as one of the types of speech activity in English lessons // Young scientist. 2015. No. 19. pp. 569-571.

INFORMATION ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Zheleznova Elena Grigorievna,

Senior Lecturer, Department of Linguistics and Translation, Southern Institute of Management, Krasnodar, Russia. Tel.: (906) 434 08 70, e-mail: [email protected]

3. Rustemova S.K., Alimzhanova B.E., Baigoshkarova M.I., Babzhanova R.Zh. Methods of teaching reading at English lessons // Young scientist. 2015. No. 11. S. 1478-1481.

4. Muñoz Marín J.H. Exploring Teachers' Practices for Assessing Reading Comprehension Abilities in English as a Foreign Language. Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, [S. l.], p. 71-84, july 2009. Available at: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/11443/36796.

l.], p. 71-84, july 2009. Available at: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/11443/36796.

5. Brumfit C. The Teaching of Advanced Reading Skills in Foreign Languages, with Particular References to English as a Foreign Language. Language Teaching & Linguistics: Abstracts. 1977; 10(2): 73-84. doi:10.1017/ S0261444800003311

REFERENCES

1. Birkner V. Reading Comprehension in Teaching English as a Foreign Language [Internet]. Available from: https://www.monografias.com/trabajos68/readins-comprehension-teaching-english/readins-compre-hension-teaching-english3.shtml

2. Gordeeva I.V. Reading as one of the types of speech activity in English lessons. young scientist. 2015; (19): 569-571. (In Russ.)

3. Rustemov S.K., Alimzhanov B.E., Baiguskarov M.I., Bazhanov R.J. Methods of teaching reading at English lessons. young scientist. 2015; (11): 1478-1481. (In Russ.)

4. Muñoz Marín J.H. Exploring Teachers' Practices for Assessing Reading Comprehension Abilities in English as a Foreign Language.