Preschool opposites song

Activity: Sing Together: “The Opposite Song”: Resources for Early Learning

Standards

MA Standards

Speaking and Listening/SL.PK.MA.1a: Observe and use appropriate ways of interacting in a group (e.g., taking turns in talking, listening to peers, waiting to speak until another person is finished talking, asking questions and waiting for an answer, gaining the floor in appropriate ways).

Head Start Outcomes

Social Emotional Development/Self-Regulation: Follows simple rules, routines, and directions.

Logic and Reasoning/Reasoning and Problem Solving: Classifies, compares, and contrasts objects, events, and experiences.

Language Development/Receptive Language:

Attends to language during conversations, songs, stories, or other learning experiences.

PreK Learning Guidelines:

English Language Arts/Language 1: Observe and use appropriate ways of interacting in a group (taking turns in talking; listening to peers; waiting until someone is finished; asking questions and waiting for an answer; gaining the floor in appropriate ways).

English Language Arts/Reading and Literature 12: Listen to, recite, sing, and dramatize a variety of age-appropriate literature.

Sing Together: “The Opposite Song”

© Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Department of Early Education and Care (Jennifer Waddell photographer). All rights reserved.

ELA Focus Skills: Phonological Awareness (Rhythm, Rhyme, and Repetition), Vocabulary (Opposites)

Remind children that in the book The Ugly Vegetables, the little girl thought the other gardens were beautiful but she felt her garden was ugly. Explain that the words beautiful and ugly mean two completely different things. Say, They are opposite words.

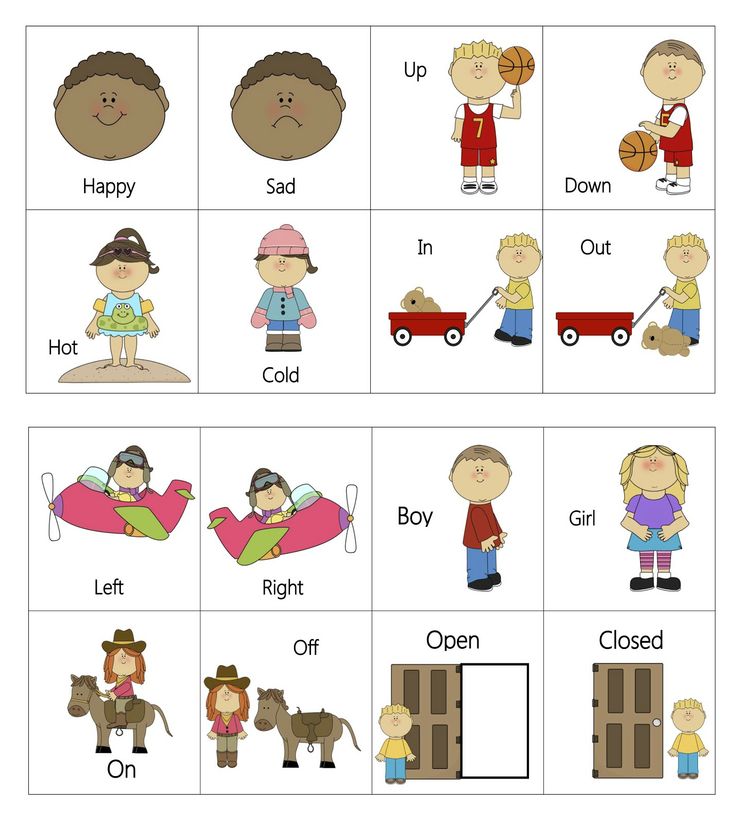

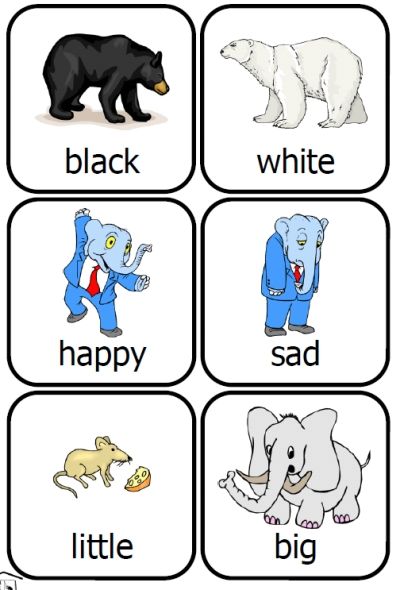

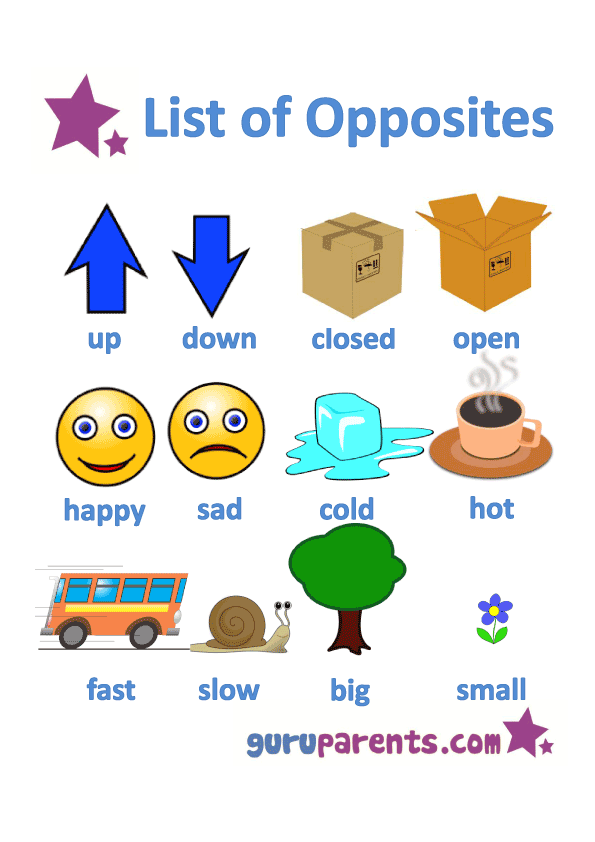

- Give a few more examples of opposite words. Say The opposite of the word yes is no. The opposite of the word up is down. Ask, What do you think the opposite of the word hot is? (cold) What about the opposite of the word happy? (sad)

- When you feel children have grasped the concept of opposite words, tell them you are going to teach them a song about opposites.

Sing “The Opposite Song” for children. As you sing the second and third verses, say the first word in each opposite pair, then start the next line and cue children to supply the opposite word. For example, you say stop/children say go. Repeat with yes/no, fast/slow, low/high, hi/bye, and wet/dry.

The Opposite Song

(sung to the tune of “Do You Know The Muffin Man?”)

Oh, do you know some opposites,

Some opposites,

Some opposites?

Oh, do you know some opposites?

Opposites are fun.

If I say stop, then you say go.

If I say yes, then you say no.

If I say fast, then you say slow.

Oh, opposites are fun.

If I say low, then you say high.

If I say hi, (wave hand), then you say bye.

If I say wet, then you say dry.

Oh, opposites are fun.

Take It Further: Encourage children to think of other opposites to include in the song. Other opposites might include dark/light, day/night, left/right, young/old, bought/sold, hot/cold, low/high, sell/buy, ground/sky.

30 Best Preschool Songs

Preschool songs aid in a child’s growth and development by making learning fun and engaging; no wonder children are exposed to songs from an early age. Whether in the classroom or singing them a lullaby, this exposure ignites their development. This is why it’s important to incorporate music (singing and dancing) in your lesson plans.

Singing and dancing are excellent teaching tools and a source of joy for preschool children as they love moving around and making noise. While singing and dancing, children learn about their body movements, develop their vocabulary, begin to understand the concept of numbers, build their confidence, engage their brains, and improve social skills.

Songs for preschoolers by category

Research shows that a child’s brain development and music are closely linked. Therefore, exposing children to songs early will support their development. Naturally, children are more engaged and learn better through fun and play. Preschool songs can introduce new concepts to your classroom through things like rhyming lyrics and repetitive melodies. Below are some of the best preschool songs for children.

Action and movement preschool songs

Action and movement songs combine music and movement by encouraging children to move their bodies or “act out” the lyrics. These songs strengthen children’s memory, help develop fine and gross motor skills, enhance hand-eye coordination, and foster self-confidence. Furthermore, these songs also build your child’s concentration, listening, and balancing skills.

1. The Hokey Pokey

This is a popular preschool song that most children and teachers enjoy and is easy to follow. Have the children form a circle and slowly demonstrate how you’ll act out the song. Act out the lyrics as the song plays.. You can also use toys to demonstrate this.

Act out the lyrics as the song plays.. You can also use toys to demonstrate this.

2. I'm a Little Teapot

Hold a cup or teapot and act out the song showing the handle, tipping it over, and pouring. This is an engaging movement song that will exercise your children’s gross and motor skills.

3. Teddy Bear, Teddy Bear

This song allows children to dance and wiggle around with their favorite toys. Continue acting out the song and imitating the actions like jumping up, wiggling, and touching your nose.

Circle time songs

You can sing these songs as children gather in a circle to participate in a guided activity. These songs help children build language and social skills, remind them it’s time to gather together, and help calm them down.

4. Come to the Carpet

This song signals children to stop or wrap up whatever they’re doing and come to the carpet and sit. Repeat the verse several times so that children can sing along with you.

5.

If You’re Happy and You Know It

If You’re Happy and You Know ItGuide your children to do the actions in the song. For instance, if the song says, “clap your hands,” encourage them to clap their hands. Ensure you move at their pace. This is also a great transition song to use as you prepare for circle time.

6. The Farmer in the Dell

This preschool song will boost your children’s memory, vocabulary, and listening skills. As each verse builds upon the last, have children form a circle and sing along.

Welcome songs

Welcome preschool songs can be used to make children feel welcome and set a tone for the rest of the day. You can sing welcome songs as you begin the school day or after children have transitioned from one activity.

7. Hello Neighbor

This preschool song is a great way to start the day on a friendly note by having children interact with each other and greet their neighbors.

8. Hello, Hello, Can You Clap Your Hands?

This welcome song is perfect to start your day or calm your children as they warm their bodies. Children can also sing this song as they take breaks.

Children can also sing this song as they take breaks.

9. Good Morning Song

This is another fun welcome song to add to your morning routine. This pre-k song is easy to learn, fun, and will encourage your children to dance around as they prepare for the day.

Early math, numbers, and counting

Numbers and counting songs for preschoolers help them memorize the order of numbers. You can ask them to count up, for instance, from one to 10, or down, from 10 to one. These songs also help children grasp number concepts such as addition and subtraction.

10. Five Little Ducks

This song will help develop your preschoolers' cognitive and math skills. As you sing, use your fingers to show numbers like one, two, and three. You can also use pencils or straws to count out the numbers.

11. Five Little Speckled Frogs

For this song, grab green items to represent the speckled frogs as you sing the song. Repeat verses until there are no “speckled frogs” left.

12. One, Two, Buckle My Shoe

Sing this song as you use your fingers. For instance, if the song says one, point out one finger, and continue up to 10. Then, start all over again from one. As you do this, show children numbers by writing them out or using your fingers or blocks.

13. Ten Green Bottles

With this song, you can incorporate bottles or plastic glasses to illustrate this concept better. Continue singing the verses from 10 down to one, and then start all over again.

Source

Parts of the body songs

Your children will love these interactive songs. These will help improve motor skills, coordination, and help your child learn the names of their different body parts. These songs are also easy to demonstrate and follow along.

14. Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes

Act out the song with the children and teach the names of different body parts.

15. My Hands

You can sing this song while standing or during circle time. Act out the song and do the actions as you sing along with your children. For instance, when the song says “my hands,” show children your hands and ask them to do the same.

Act out the song and do the actions as you sing along with your children. For instance, when the song says “my hands,” show children your hands and ask them to do the same.

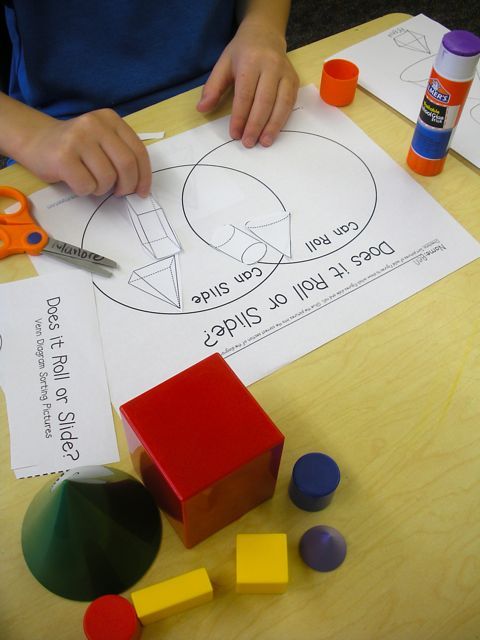

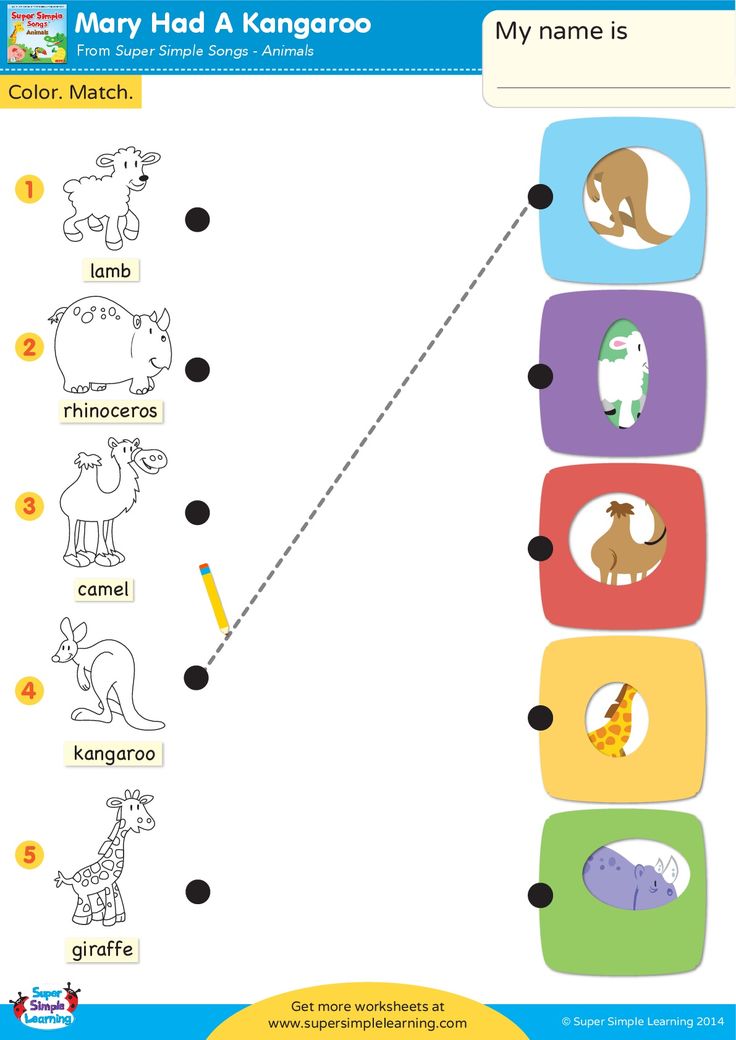

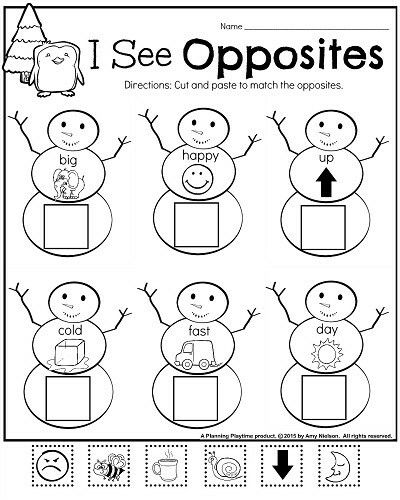

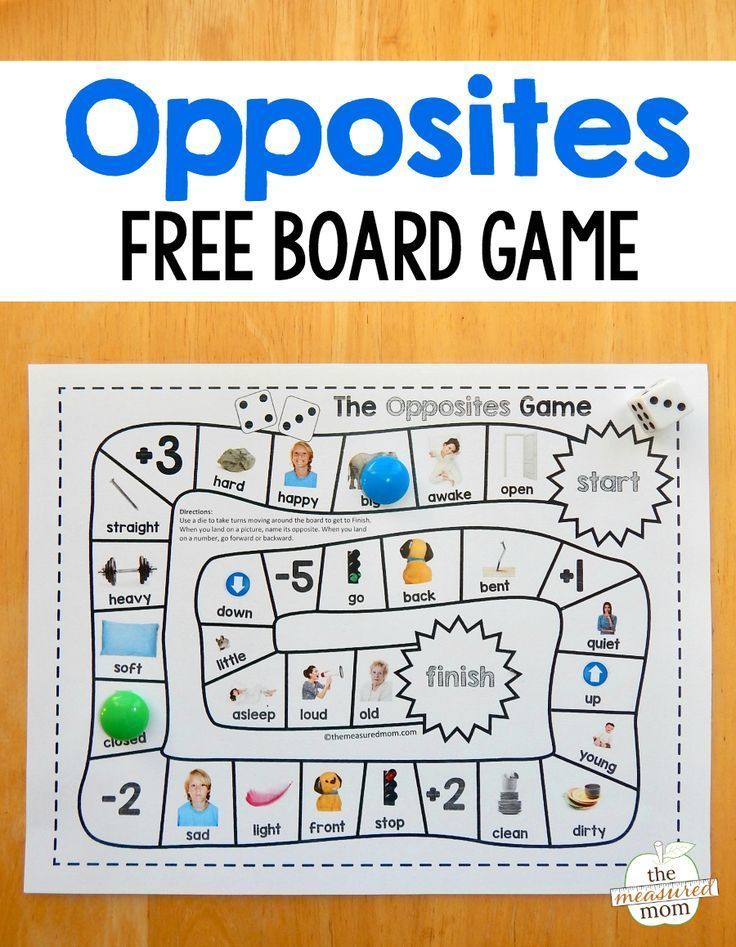

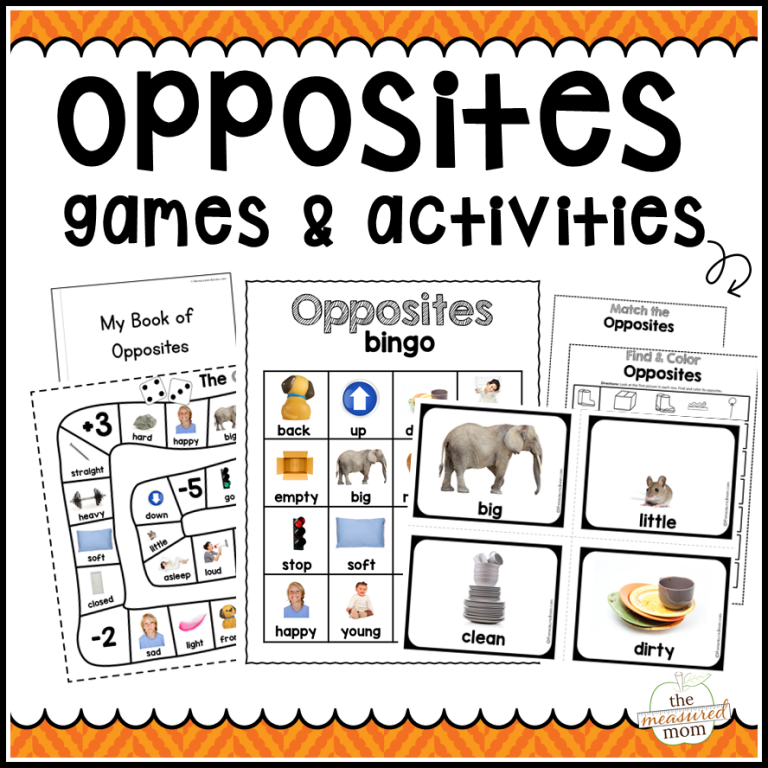

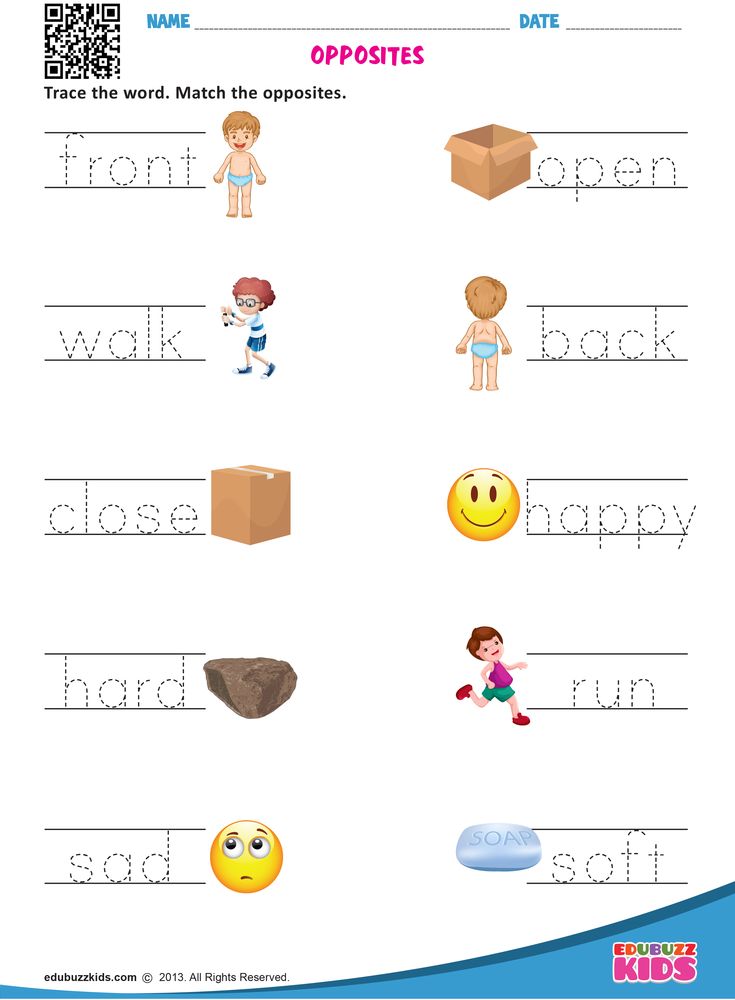

Opposites preschool songs

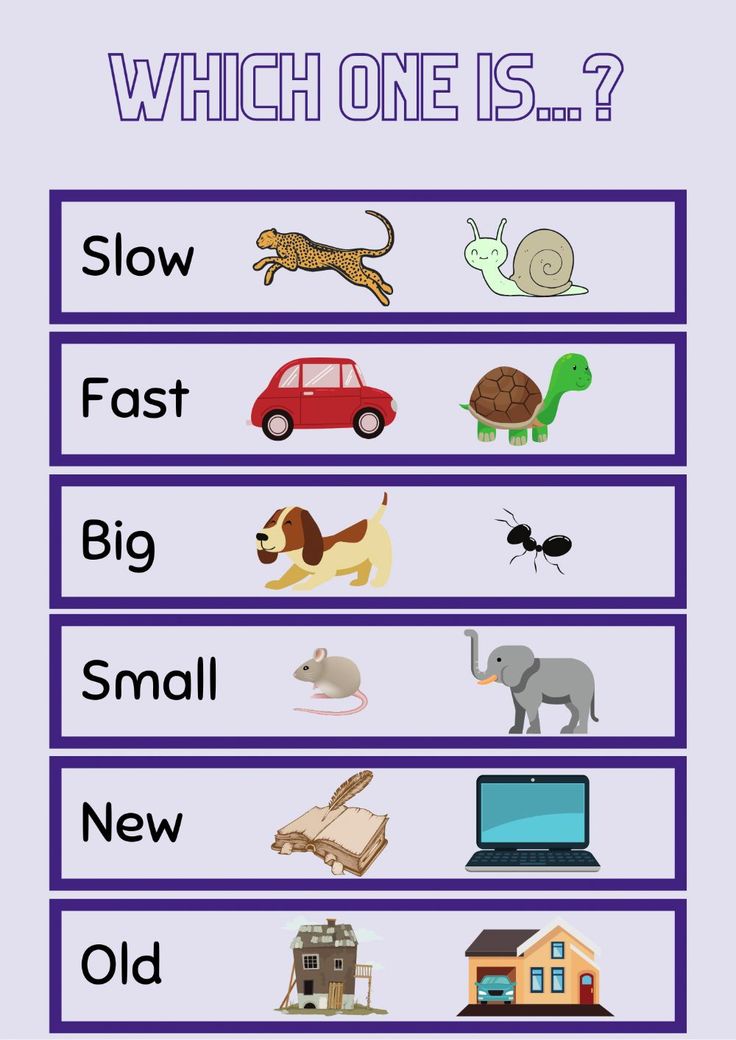

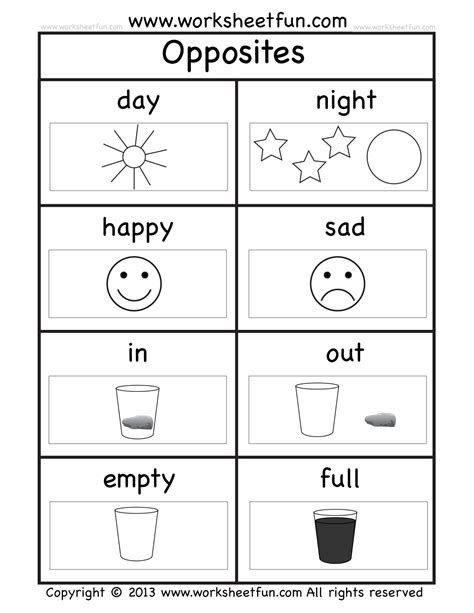

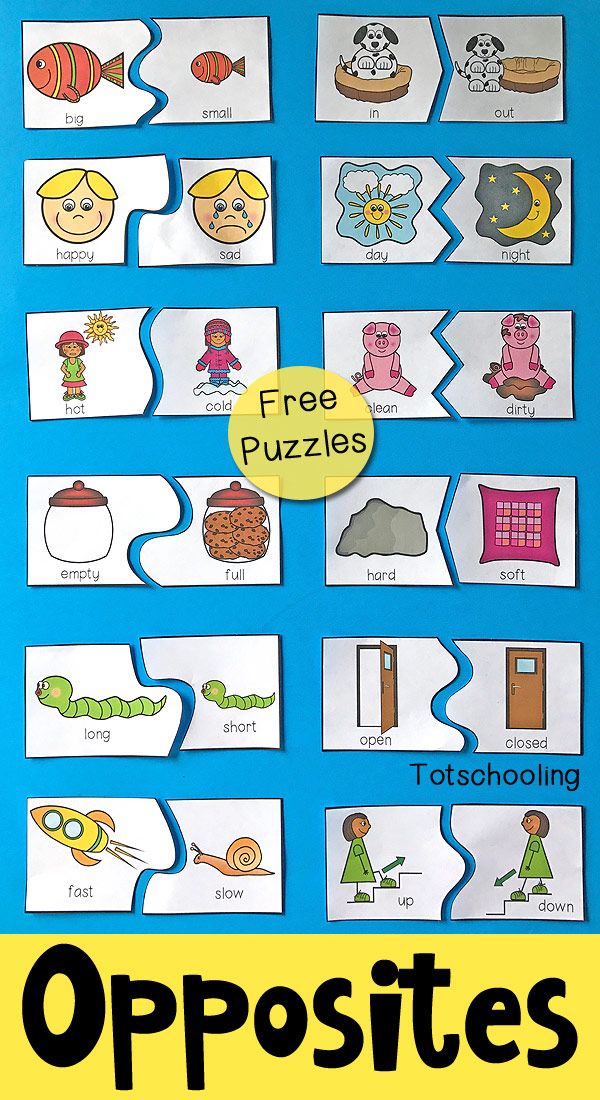

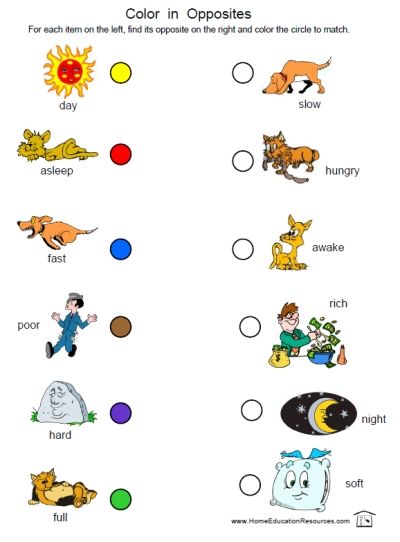

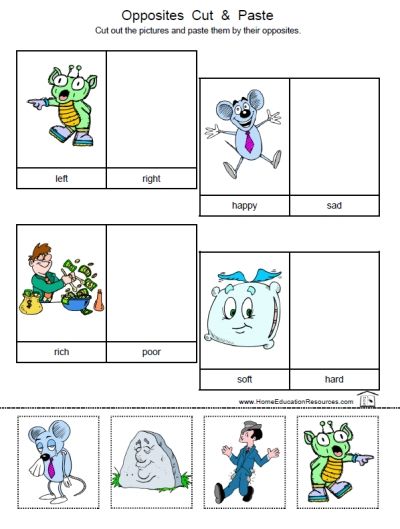

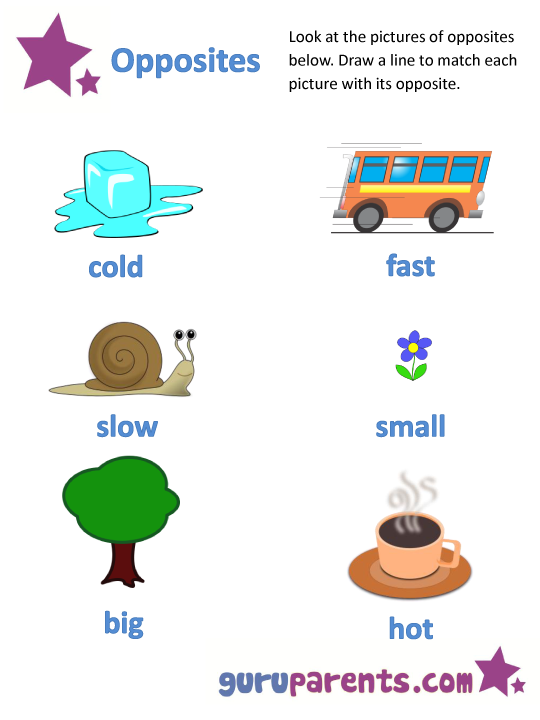

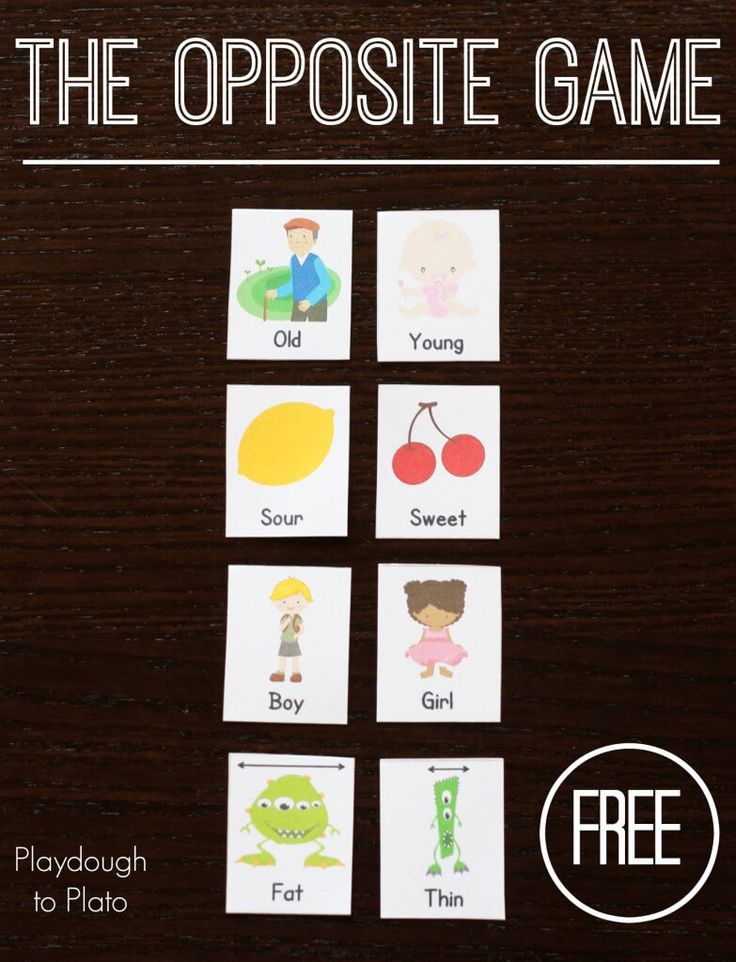

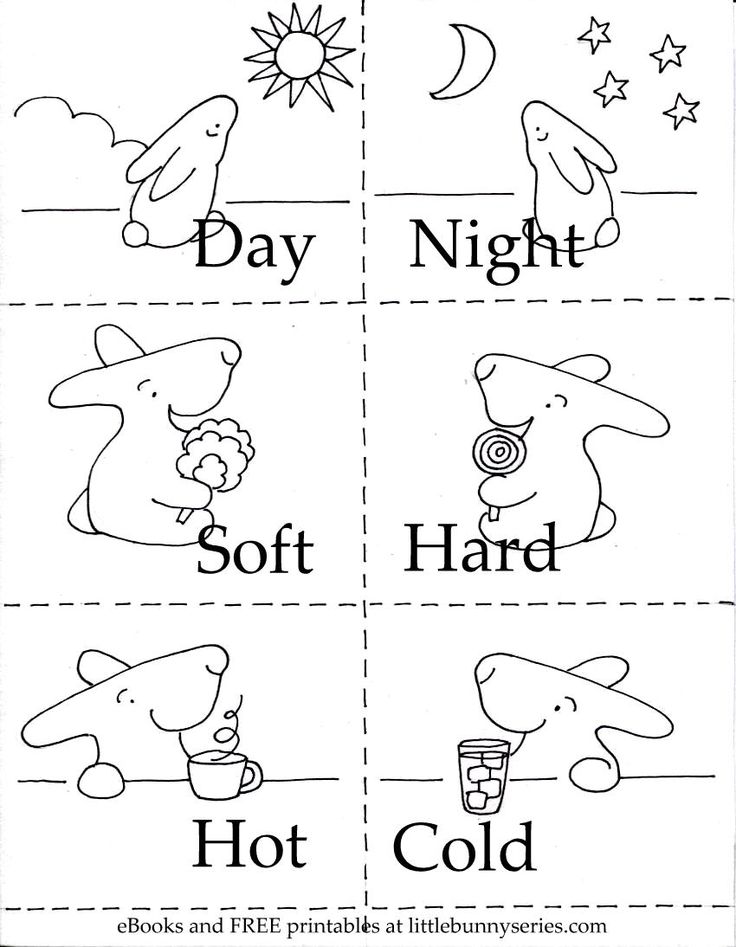

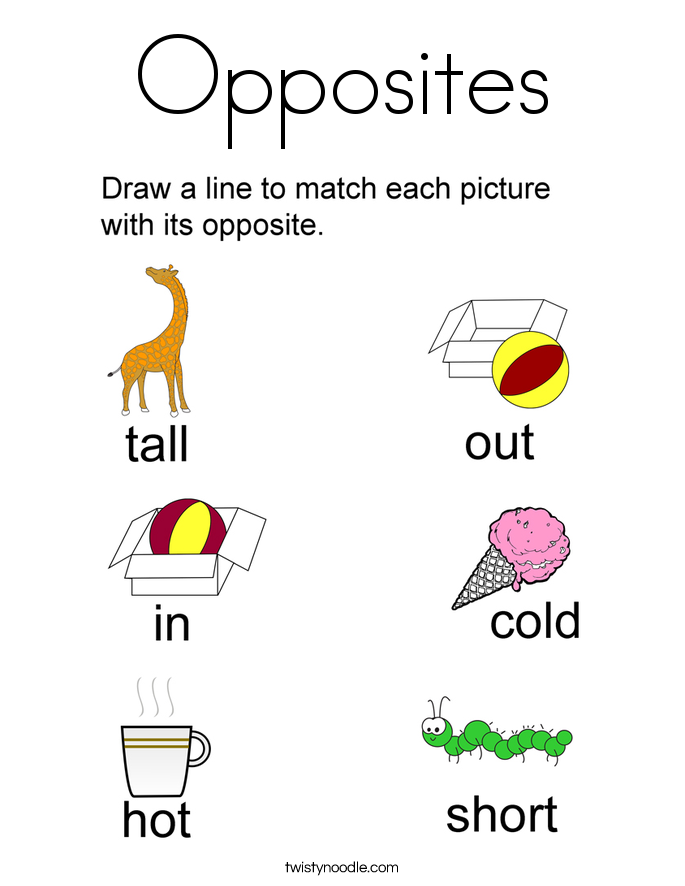

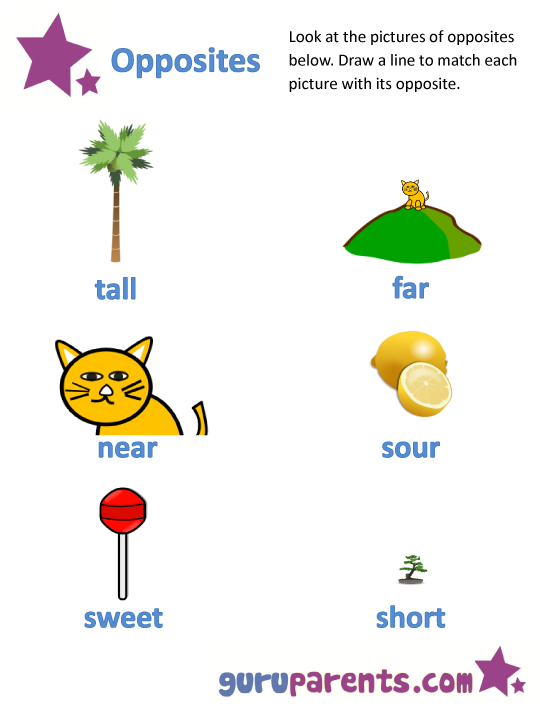

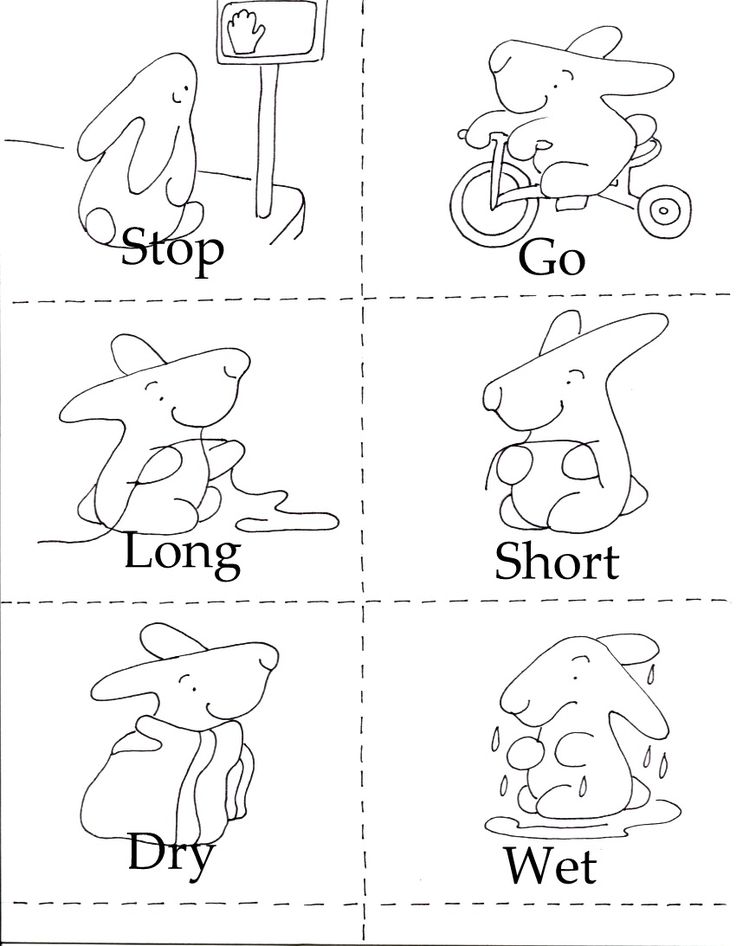

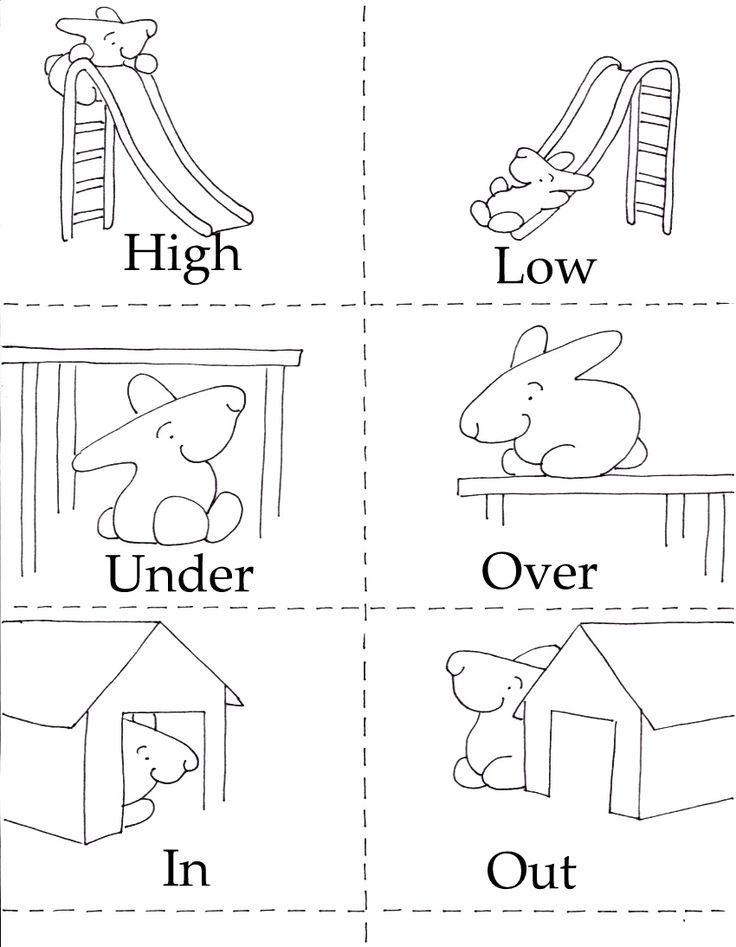

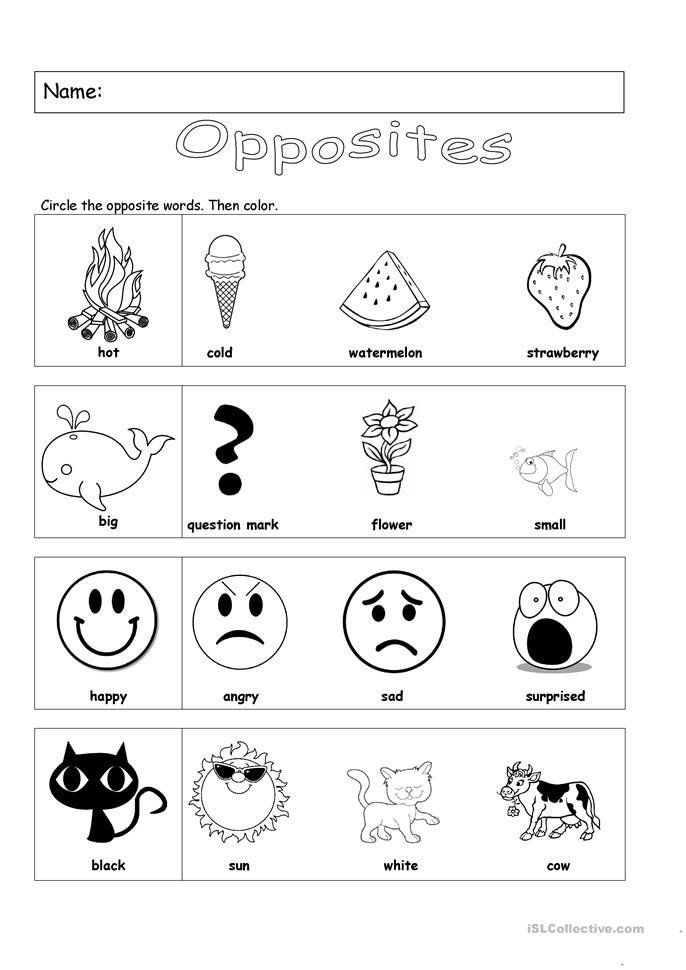

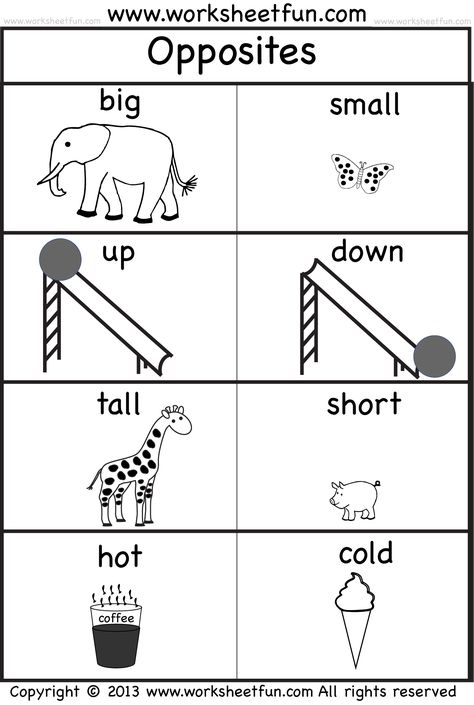

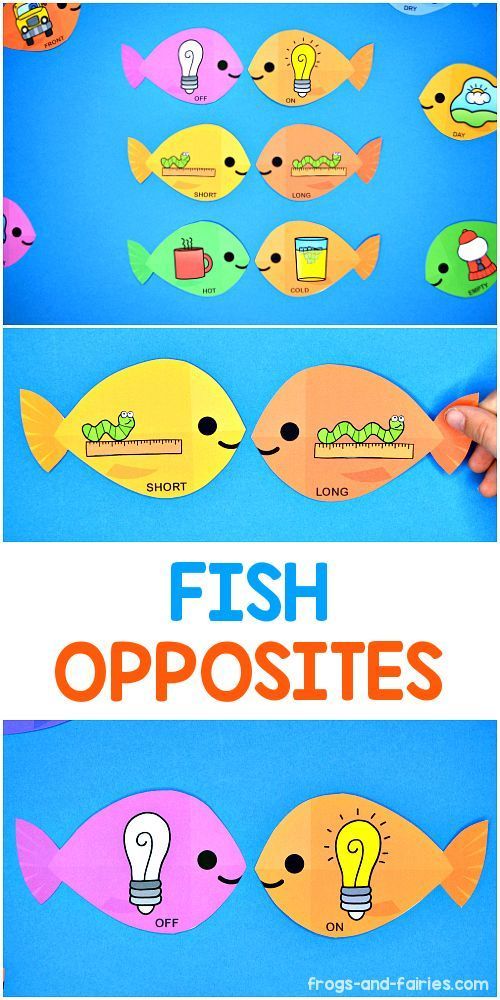

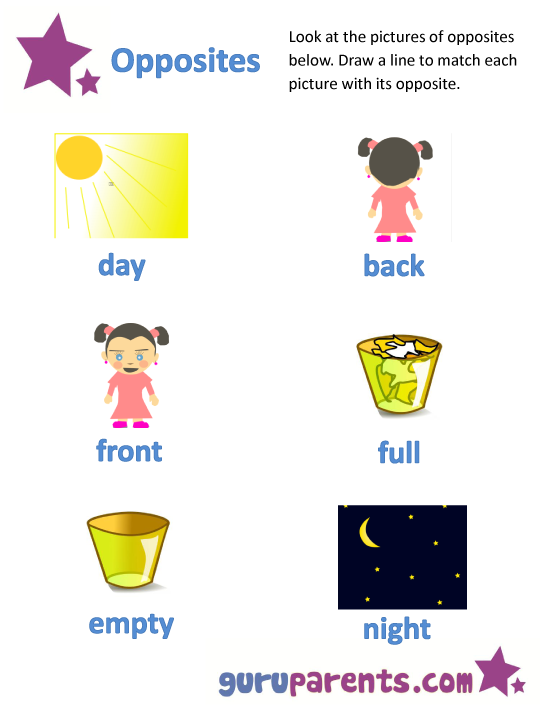

Singing “opposites” songs help children understand specific concepts such as soft vs. hard, high vs. low, big vs. small, and also helps them to compare two different things.

16. Open Shut Them

To make this song more fun, pick out one child and act out the song together. When you say “open,” the child says “shut.” When you say “big,” the child says “small”.

17. The Opposites Song

You can reinforce the opposite concept in this song by pairing it with flash cards to illustrate the different examples in the song.

Weather and seasons songs

Weather and seasons preschool songs help children learn and understand how the four seasons change throughout the year and the different kinds of weather associated with each season. You can play these songs at the beginning or end of a particular season.

18. The Seasons Song

This song will help you teach children about different seasons. You can use flashcards to show children the different seasons, such as, the sun to represent summer or snow to show winter.

19. Autumn Leaves Are Falling Down

As you sing, dance, and jump forward and backward with your children, imitate leaves falling down and raking leaves with your hands. Give children paper leaves or real leaves to drop as you all sing the song.

20. How’s the Weather?

This simple song teaches children about the various types of weather—sunny, cloudy, rainy, or snowy!

21. Rain Rain Go Away

This song is a great introduction to weather, especially rain! It will also help children practice the days of the week.

Values and virtues songs

It’s vital to teach children about the importance of good values, such as being polite, saying thank you, and being patient. One of the best ways to do that is through songs.

22.

Please and Thank You Song

Please and Thank You SongIntroduce the concept of saying “please” and “thank you” to your classroom with this catchy tune.

23. The Respect Song

You can use this song to teach children about the value of respect. The lyrics discuss the importance of having respect for the people and things around you.

24. Thank You Song

This song will teach children the simple practice of being grateful for the things they have. Use this song to prompt children to think about the specific things in their life that they are thankful for.

Farm songs

If you incorporate a farm theme into your lesson plans, these farm songs will help reinforce lessons about raising animals or growing food.

25. Baa Baa Black Sheep

This song incorporates different colors and counting, with lyrics that are easy to sing along.

26. Hickety Pickety My Black Hen

This song teaches rhyming and numbers. As the children sing this song, have some prop “eggs” handy and help them count how many eggs are in the hay.

27. Old Macdonald Had a Farm

This classic song exposes children to the different animals found on a farm and their sounds.

Colors and shapes songs

Teaching shapes and colors to children is an important part of their cognitive development. Consider incorporating songs like this into your lesson plans, along with activities that reinforce colors and shapes.

28. What Color Am I Wearing?

This is the perfect song to teach children about different colors. If children are wearing a particular color mentioned in the song, point it out, and ask them to stand, or you can hold up different colored objects that correspond to the color in the song.

29. I Love Colors Song

This song reinforces colors of common items children are exposed to. Continue the lesson after this song by having children identify different colored items in your classroom. For example, you could ask, “Can you find something red?”

30. The Shapes Song

Pair this song with other activities, such as drawing shapes, building with blocks, or creating shapes with playdough.

Incorporate preschool songs in your lesson plans to reinforce key learning objectives. Download our daily lesson plan template and customize to suit your teaching style and children's needs.

Bottom line

Singing preschool songs helps children learn, fosters development, and should be incorporated into every curriculum. With so many songs to choose from, it’s easy to find a song to enhance your classroom activities and keep children engaged in the learning process.

Brightwheel is the complete solution for early education providers, enabling you to streamline your center’s operations and build a stand-out reputation. Brightwheel connects the most critical aspects of running your center—including sign in and out, parent communications, tuition billing, and licensing and compliance—in one easy-to-use tool, along with providing best-in-class customer support and coaching. Brightwheel is trusted by thousands of early education centers and millions of parents. Learn more at mybrightwheel.com

Learn more at mybrightwheel.com

The mood of the fifth and the children's song - Ditina Waldorf

About the feelings of a small child

The use of the term "mood of the fifth" goes back to a report read by Rudolf Steiner on March 7, 1923 in Stuttgart, where the musical experience associated with various qualities of intervals is brought into interconnection with changing in the process of child development ways of experiencing the world. “Until the ninth year of life, a child is not yet able to truly understand the majors and minors ... The child still lives very strongly “in the mood of a fifth,” no matter how little we would like to.

Of course, I want to take for school those pieces that already have thirds. But if we want to approach the child in the right way, then we need to understand the fifth. It will be a great boon for a child if he gets acquainted with the major and minor, with the third as such, already after the age of nine, when he begins to ask us important questions.

He then develops a craving for life in the major and minor thirds. In the same way, for example, around the 12th year, we try to stimulate children's understanding of the octave. Thus, what is presented to the child should be appropriate for his age.

We can say that here we are talking about one of the central instructions of R. Steiner regarding musical pedagogy, which in practice turn out to be extremely fruitful. The important thing is exactly how Steiner characterizes the child entering school age: "The child lives mostly still in the mood of the quint."

As always, he does not give any simple recipes like: “Play music with small children pentatonic! ". Instead, with the help of small remarks, he directs the "listening" attention of the teacher and educator to the big secret of the child's being. In the autobiographies of many people, one can find childhood memories that more or less clearly reflect the metamorphoses of mental states through various age stages. A musician familiar with the anthroposophical doctrine of man will recognize in these descriptions the moods of the various intervals. Let us try to illustrate this with the help of some excerpts from the memoirs of Ernst Bloch.

Let us try to illustrate this with the help of some excerpts from the memoirs of Ernst Bloch.

“The feeling was amazing. The wind in the leaves, the bushes, the garden behind the house, very neglected - you do not dare to go into it. And if you close your eyes, then the little black pump will not see you. The bush behind it and the young dog I named Meintwegen are my first friends. Also, the wooden goats for the tub were also called that, no, they were called like this: “meint” was called a long one, and “wegen” was a transverse board. Absolutely understandable. The goats were not only called that, but they themselves spoke continuously. The streets on the way there looked completely different than the way back. Therefore they lived. We ran to the place where the baker and the evil witch lived and struck the tower clock ... And at the age of eight, the most surprising thing seemed to me a small roller box for sewing supplies. Something was depicted on it in small colored spots: a hut was visible, a yellow moon shone high in the winter sky, and a red light burned in the window. I was unspeakably shocked by this and the red window could never forget. Every person must experience this at some point, whether it be words or pictures that come across to him.

I was unspeakably shocked by this and the red window could never forget. Every person must experience this at some point, whether it be words or pictures that come across to him.

These are his very early experiences, but if they didn't end at the same early age, then the picture would be more important to him than himself, and even more important than his whole life. It happened to me the same year when I was walking in the woods and suddenly felt "me" as someone who feels himself, who looks out, who can never be rid of again - it is both terrifying and magnificent - who forever sits with a globe in his hut; who always remains, even if he is no longer with his comrades, and who eventually dies alone, but he has a red window behind which he always sits.

“At the age of twelve, anxiety appears, you have already matured, and at the same time a certain sobriety appeared. There are a lot of rude boys in the class, you no longer want to go to school. Friends: black-haired boy, we do all sorts of outrages, love and respect each other, which is so important at our age. A blond boy with an unhealthy complexion, some strange sweater was put on him, but he wore it with dignity and strength was visible in his green eyes. He gave us books to read in which the sea wind whistled. We also had postage stamps, a magnet and a spyglass. Iron pulled, and glass took us to distant things and we wanted to go somewhere very far away. At that time, I wondered: why are things differently heavy? and wrote it down for himself.

A blond boy with an unhealthy complexion, some strange sweater was put on him, but he wore it with dignity and strength was visible in his green eyes. He gave us books to read in which the sea wind whistled. We also had postage stamps, a magnet and a spyglass. Iron pulled, and glass took us to distant things and we wanted to go somewhere very far away. At that time, I wondered: why are things differently heavy? and wrote it down for himself.

In these descriptions, the relation of the inner world of the soul to the real outer world is very clearly manifested. In the first 8-9 years, the border is still indistinct, highly transparent. As a rule, the child still feels himself in unity with the world, moreover, in a fabulously imaginative way, where dead objects are still experienced as living beings. With the advent of the experience of one's own separate Self, around the ninth year of life, this "blessed world" splits in two. The child now interacts with the outside world in a completely new way, now looks at his parents and teachers with a critical eye, taking a certain distance in relation to them. It is striking that now the child notes the beauty of the landscape, which was previously uninteresting for him.

It is striking that now the child notes the beauty of the landscape, which was previously uninteresting for him.

In contrast, in the inner space of the soul for the first time there is a premonition of the fatefulness of one's own existence. Anticipating the time of puberty, when this process really deepens and differentiates, the child from that time on experiences a still vague, as if inexpressible "endless longing" for the fulfillment of his destination (Bloch: "I want to go somewhere far away"). Against this background of life, which is still inaccessible to consciousness, the boredom of “philistine” everyday life suddenly makes itself felt. The experience of beauty is now accompanied by pain.

* * *

In the studies of musical ingenuity and hearing in children undertaken during the First World War, cognitive interest was directed to a very indefinite area, hitherto not amenable to direct access to empirical-physiological studies and tests.

Those very subtle differences in experiences, which are undoubtedly observed in musical pedagogical practice, are difficult to fix in isolated test situations. The interactions of melody, rhythm, meter, tempo, consonance, tonality, form are too multilayered in this non-conceptual field, direct access to which is open only to feelings.

The interactions of melody, rhythm, meter, tempo, consonance, tonality, form are too multilayered in this non-conceptual field, direct access to which is open only to feelings.

Therefore, one should not be surprised when test-based music pedagogy research on certain aspects often gives conflicting results. Nevertheless, the studies carried out allow us to see in general terms the features of musical development, which I will try to briefly describe here.

The musical world of a child differs from the world of an adult. The melodic contour is, apparently, the most important feature by which babies distinguish a melody. They do not yet recognize absolute intervals and specific pitches. They perceive the melody in its entirety and recognize only by the melodic contours, the sound range and the characteristic rise and fall of the melody. Some light on the gradual formation of a sense of tonality is shed by the fact that children under six years of age consider a melody complete when it stops sounding, no matter what sound it ends on. Then we see how the sense of tonality is layered on the sense of harmonic hearing: it seems that only from the age of 11-12 children begin to feel the relationship between the sounds of the scale and the main functions of the harmonic cadence: at this age they already understand the tonic-subdominant-dominant cadence scheme. tonic and are already able to distinguish whether the melody accompanied by chords is complete or not. Children under nine years of age do not yet know the difference between major and minor.

Then we see how the sense of tonality is layered on the sense of harmonic hearing: it seems that only from the age of 11-12 children begin to feel the relationship between the sounds of the scale and the main functions of the harmonic cadence: at this age they already understand the tonic-subdominant-dominant cadence scheme. tonic and are already able to distinguish whether the melody accompanied by chords is complete or not. Children under nine years of age do not yet know the difference between major and minor.

And even at the age of nine, they will not recognize a familiar melody if it is harmonized. In the rhythmic area, the peculiarities of the perception of a small child also affect. Five-year-olds and even eight-year-olds have great difficulty in recognizing a melody if it is repeated with an altered rhythm. As early as five years old, many children experience rhythms very clearly: when the rhythm slams or stomps, they call it “the clatter of horses” or they think that some little men are working and making noise. Preschool children are easier to slap the rhythmic pattern of speech than the meter of the verse. They do not yet know pauses as a musical event. If they have pauses, then only from the need to inhale - therefore, they are irregular in duration. The feeling of meter develops from the age of nine and a half: then the time relations within the measure are already distinguished and maintained.

Preschool children are easier to slap the rhythmic pattern of speech than the meter of the verse. They do not yet know pauses as a musical event. If they have pauses, then only from the need to inhale - therefore, they are irregular in duration. The feeling of meter develops from the age of nine and a half: then the time relations within the measure are already distinguished and maintained.

Study of traditional children's songs

The interest of scholars in children's song was awakened around 1800. The first milestone was the popular collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy Had a Wonderful Horn) (1808). This marked the beginning of an active collection of children's songs, which revealed all the richness of traditions. When considering the latest studies of children's songs written after the Second World War, it is striking that they are mostly of interest to historians and folklorists and only occasionally touch upon issues of developmental psychology. The few attempts to determine the essence of a children's song are almost always limited to the study of the content of the text, sometimes also include consideration of the metrical form. Melody questions seem unworthy of attention.

Melody questions seem unworthy of attention.

The qualities characteristic of a traditional children's song could be illustrated by the example of the song “As our Adam had seven sons” (“Adam hatte sieben Sonne”) known to many generations.

Like our Adam

Had seven sons.

They didn't eat, they didn't drink,

They did everything like me:

With fingers - type, type, type,

And with the head - nick, nick, nick,

With legs - top, top, top,

With handles - clap, clap clap.

You are rutabaga, you are rutabaga,

You are the best plants.

When the father will marry,

We will dance.

Adam hatte sieben Sonne,

Sieben Soehn’ hatt’ Adam.

Sie assen nicht, sie tranken nicht,

Sie machten alle so wie ich:

Mit dem Fingerchen tip, tip, tip Haendchen klapp, klapp, klapp.

Koehlrueberchen, Koehlrueberchen,

Das sind die besten Pflanzen,

Und wenn mein Vater Hochzeit haelt,

Dann fangen wir an zu tanzen.

The song has no development (like, say, in a ballad). It seems unfinished and can be repeated as much as you like. In the content, unrelated motifs appear in succession: the sons of Adam, parts of the body, plants, a wedding dance. Only partially rhyming versions correspond to the two-bar musical triads produced by the speech rhythm (2/4). Two motives are distinguished here:

1) (c) | g g a a | g (f) e (c) |

2) a | g f e 1 a | g f e |

In the first motive one can easily guess the old children's trichord song g a | g e. F and c appear here only as unstressed passing sounds. Musical motifs appear here as interchangeable and can match any song text.

In this regard, I would like to cite one remark of the great German folk song collector Franz Magnus Boehme: “A real children's song is extremely simple in its sound ... It knows, in fact, only one single melody. The latter comes from a major, has a two-quarter time and is a constant repetition of one two-bar motif. However, is our melody really already in a major? Isn't it rather still in the neutral region, preceding major and minor? True, if we proceed from the way of hearing a modern adult, we can state in it the main sound c, but how weakly and imperceptibly it acts here, appearing only four times and, moreover, in an unstressed position! It is not given any final force. Wouldn't it be more appropriate for the melodic unfolding of the song to feel the "centrality" of the g sound and the absence of the root? In the open soaring of the melody, a reflection of the above-mentioned spiritual mood of the child is felt. The main tone does not yet have its own position.

However, is our melody really already in a major? Isn't it rather still in the neutral region, preceding major and minor? True, if we proceed from the way of hearing a modern adult, we can state in it the main sound c, but how weakly and imperceptibly it acts here, appearing only four times and, moreover, in an unstressed position! It is not given any final force. Wouldn't it be more appropriate for the melodic unfolding of the song to feel the "centrality" of the g sound and the absence of the root? In the open soaring of the melody, a reflection of the above-mentioned spiritual mood of the child is felt. The main tone does not yet have its own position.

Likewise, the text, with its non-binding, spasmodic stringing of different motifs, does not yet contain that solidity, from the point of view of which the world appears accurate and objective. Here the world, being thoroughly imbued with the forces of fantasy, is still in constant change.

It was in this mood that one six-year-old kid once composed a poem:

When pigs grow on trees,

Then spring comes.

Both cows and people

They also grow on trees.

First there are kidneys,

And then pigs, and cows, and people.

James Crews very aptly commented on this: "Undoubtedly the poem is childish, undoubtedly it is not bad and undoubtedly its illogicality is perfectly legitimate within that blessed, powerful world in which spring and birth, kidneys, piglet, calf and baby are naturally equal. and man takes his place after pigs and cows. An adult, reading this six-line, enters paradise with longing and surprise.

Ruth Lorbe comes to very similar conclusions based on an analysis of the texts of numerous children's songs: “Everything that a child encounters must participate in the process of transformation ... Without hesitation, the child joins what he perceives and what he transforms to each other without any connection, if only it is combined in rhythm ... As the things of the external world, as if in play, are accepted by the child into themselves, in the same way they undergo their transformation in the deepest spheres of the child's being in play. What is played out in children's games and children's songs is, as it were, a child's fantasy and material from the outside world merged together.

What is played out in children's games and children's songs is, as it were, a child's fantasy and material from the outside world merged together.

In his extremely interesting book "Early Forms of Cognition", the Egyptologist E. Brunner-Traut gives the following description of the tale: correlative interlacings. We are talking about an ancient Egyptian fairy tale, but this characterization is entirely suitable for a modern children's song. E. Brunner-Traut shows in various spheres of life many parallels between modern children's consciousness and the consciousness of the ancient Egyptian (based, for example, on texts in which the body is understood as the sum of its parts, and not as an organism with interconnected members). In the song we are considering, this corresponds to the place where it is sung: “Fingers - type, type, type ...”.

Such parallels make it clear why Steiner used the term "mood of the fifth" both to characterize the self-perception of a small child and to characterize consciousness in a bygone stage of human history.

Tips from Rudolf Steiner

In 1900, the “centenary of the child” was proclaimed. Along with many reformist pedagogics, the youth movement that emerged from the youth tourism organization tried to rethink the old tradition in the field of music - an interest arose in folk songs, guitar, recorder. This youth music movement (Fritz Jode, Walter Hansel, etc.) had a strong influence on music pedagogy in Germany. Representatives of Waldorf pedagogy should not forget that the slogan "education through music" comes from here. And the widespread tradition of playing recorders in Waldorf schools can hardly be imagined without the influence of this youth musical movement.

Indicative of the strength of this explosive mood that prevailed in the 20s of the last century, is the fact that two such significant composers as Carl Orff and Zoltan Kodály gave, each in their own way, powerful impulses for musical pedagogy. At the same time, Kodály went to bring children through methodically constructed singing to conscious and understanding listening, while Orff strove for “interpenetration and complementarity of musical education and movement education” (the so-called Dionysian approach). Moreover, Orff invented a special way of exercising for the improvised mastering of musical elements on "rhythmically oriented and relatively light instruments close to the human body." At the same time, Rudolf Steiner gives his views in this area, which his students (composers Paul Baumann, Elisabeth and Heinrich Ziemann-Molitor, Edmund Pracht, Alois Künstler) rework in their own way.

Moreover, Orff invented a special way of exercising for the improvised mastering of musical elements on "rhythmically oriented and relatively light instruments close to the human body." At the same time, Rudolf Steiner gives his views in this area, which his students (composers Paul Baumann, Elisabeth and Heinrich Ziemann-Molitor, Edmund Pracht, Alois Künstler) rework in their own way.

Paul Baumann as a music teacher was a member of the board of teachers of the first Waldorf school. After receiving his musical education, he worked for some time as a bandmaster. With great enthusiasm, he put his composing talent at the service of the new pedagogy. If you look at his extraordinarily fruitful songwriting, first of all, the harmonic attire of piano accompaniment to very simply composed children's melodies is striking, reminiscent of romance. At 19In 27, in one of his musical articles, P. Baumann wrote: “The teacher should look for the “mood of the fifth” in the child himself through his inner mood: then he will be able to choose the right exercises and compositions. ”

”

Elisabeth Ziemann-Molitor began teaching instrumental music at the Hamburg Waldorf School in 1926. For her early work, her husband, engineer Heinrich Ziemann perfected pentatonic flutes and metallophones. In their numerous publications, the Ziemann-Molitor couple developed Steiner's guidelines for musical pedagogy. For practical use, their collection "200 Old German Folk Songs for Pentatonic Flute" was published.

Edmund Pracht came to the Goetheanum in Dornach as a young pianist in the 1920s. After founding the anthroposophic curative pedagogy in 1924, he worked as an accompanist in eurythmy classes at the Sonnenhof Medical Pedagogical Institute in Arlesheim, later also as a music teacher. He gained fame thanks to the introduction of a completely new, vaguely reminiscent of the ancient lyre, which in 1926 was made with the help of the sculptor Lothar Gärtner. In connection with the appearance of this new instrument, which was first used in medical and pedagogical work, many new compositions arose, including children's songs. Pracht used for his songs in the mood of a fifth mainly the scale d e g a h d 1 e 1 i.e. pentatonic scale, where the total volume of nona can be easily perceived as paired fifths around the central sound a. In contrast to the traditional children's song with its stereotyped subordination of sounds to any text, Pracht managed, by limiting the children's song to pentatonic monophony, to achieve consistency in melodic and verbal images in many of his songs. At the same time, Pracht was a man who always summed up the exact conceptual base for everything he did. For example, his book The Development of Musical Life in Childhood, written in the 1950s, is a solid work that has not lost its value to this day.

Pracht used for his songs in the mood of a fifth mainly the scale d e g a h d 1 e 1 i.e. pentatonic scale, where the total volume of nona can be easily perceived as paired fifths around the central sound a. In contrast to the traditional children's song with its stereotyped subordination of sounds to any text, Pracht managed, by limiting the children's song to pentatonic monophony, to achieve consistency in melodic and verbal images in many of his songs. At the same time, Pracht was a man who always summed up the exact conceptual base for everything he did. For example, his book The Development of Musical Life in Childhood, written in the 1950s, is a solid work that has not lost its value to this day.

Alois Künstler was the exact opposite of Pracht: he never gave any theory in his life, but his children's songs had a profound impact and were in great demand. Kunstler was a self-taught musician. As a 19-year-old gardener and educator in a school camp, in 1924 he first encountered the newly emerging anthroposophic curative pedagogy, with which he associates himself while working as a musician in the orphanage Gerswald (Uckermark). Inspired by musical eurythmy and Steiner's speeches on the experience of sounds mentioned above, he creates song gems drawing his inspiration from children.

Inspired by musical eurythmy and Steiner's speeches on the experience of sounds mentioned above, he creates song gems drawing his inspiration from children.

Musician educator Julius Knierim , whose musical work within the framework of anthroposophic curative pedagogy began in 1946 at the Stuttgart seminar for Waldorf teachers, consciously drew on the impulses given by Pracht and Künstler. He worked intensively on methodological and pedagogical issues for several decades, and his pamphlet "Songs in the Mood of Quinta", published in 1970, had a significant impact on a new generation of musicians and educators. Knierim also uses the scale already preferred by Pracht and Künstler d e g a h d 1 e 1 . This practice goes back to that place from R. Steiner's report of March 7, 1923, which says: “in antiquity, for a long time after the Atlantic period, the gamma was exactly this: d, e, g, a, h and again d, e. No f's and c's."

The mood of a fifth can always be reproduced by an adult only approximately and depends on many factors: the sound of the instrument used and the voice; on whether the rhythm is free from the meter or tied to it; from the presence or absence of a functional-harmonic corset; from the relationship between hearing, singing, playing and moving; from the language and, of course, from the intervals and qualities of individual sounds. Sound union d e g a h d 1 e 1 is especially predisposed to playing music in the mood of a fifth, just like the very sound of instruments such as a children's harp or a pentatonic "Choroi" flute - but we never have the right to say, for example, such things as "mood fifths are d e g a h d 1 e 1 "! The merit of Knirim is that he gave a methodically reliable way of exercises for the adult to get used to the world of the mood of the fifth, completely alien to him at first. His melodic-rhythmic models come from the central sound a and make it possible to overcome the habit of hearing to focus on the tonic.

Sound union d e g a h d 1 e 1 is especially predisposed to playing music in the mood of a fifth, just like the very sound of instruments such as a children's harp or a pentatonic "Choroi" flute - but we never have the right to say, for example, such things as "mood fifths are d e g a h d 1 e 1 "! The merit of Knirim is that he gave a methodically reliable way of exercises for the adult to get used to the world of the mood of the fifth, completely alien to him at first. His melodic-rhythmic models come from the central sound a and make it possible to overcome the habit of hearing to focus on the tonic.

Analysis of some songs

J. Knierim, “After the Rain”

Ein Farbenbogen steht gespannt,

Wie schoen er leuchtet uebers Land,

Er ist so rotine, blau, gelb und gruchasse sechen do

!

A rainbow of colors stretched above,

How beautiful it shines above the earth,

She is so red,

blue and green,

I wish I could walk along her street!

Here appear the forces of lightness characteristic of the mood of fifths, as opposed to the forces of gravity in music, which is oriented towards the main sound. It could be argued that children would never sing like that on their own initiative. Perhaps that is the way it is. But one might also think that the melodic formulas of traditional children's songs in bipartite meter are also not inherent in children by nature: unless the child grasps them more easily. Anyone who has the opportunity to hear the singing of preschoolers or first-graders in both manners will immediately notice the refined effect of the new song style from the changed method of singing: children listen differently. In the light of the qualitative decline in our time of this basic human ability, such songs are assigned a huge educational and therapeutic role (which, however, does not mean that children are sung exclusively in this manner). In addition, it should be assumed that in the past, the bearers of traditional children's songs were most likely children in the second seven years of age (perhaps up to 12 years old), whose age was fully consistent with the solidity and strong incarnation element of song forms with a two-part meter.

It could be argued that children would never sing like that on their own initiative. Perhaps that is the way it is. But one might also think that the melodic formulas of traditional children's songs in bipartite meter are also not inherent in children by nature: unless the child grasps them more easily. Anyone who has the opportunity to hear the singing of preschoolers or first-graders in both manners will immediately notice the refined effect of the new song style from the changed method of singing: children listen differently. In the light of the qualitative decline in our time of this basic human ability, such songs are assigned a huge educational and therapeutic role (which, however, does not mean that children are sung exclusively in this manner). In addition, it should be assumed that in the past, the bearers of traditional children's songs were most likely children in the second seven years of age (perhaps up to 12 years old), whose age was fully consistent with the solidity and strong incarnation element of song forms with a two-part meter. So for today's kids under 9years, growing up in a super-technical and intellectualized world, it is important to find in music such forms that are able to counteract the threatening acceleration and mental hardening.

So for today's kids under 9years, growing up in a super-technical and intellectualized world, it is important to find in music such forms that are able to counteract the threatening acceleration and mental hardening.

A. Künstler, "Oh, my bird"

Ei, mein Voegelein,

Schwingst die Fluegelein,

Bringstdem Kinde Sonnenschein?

Ei, du liebes Voegelein!

Oh, my bird,

Spread your wings.

Will you bring us a ray of sunshine?

My dear bird!

Light, airy, summer mood. A small bird is in a gentle wave of the wing, which is “drawn” in space by a 2-sound motif of the first measure. The question in the third measure, expanding the motif to three sounds, follows the sounds of the speech melody. The fourth measure - a joyful, affectionate exclamation - picks up the motive of the third measure, transforming it. The ending is open and light. Did the bird fly away? (Try a different final note instead of d2 and see what the effect is. )

)

Unknown author, The Nightingale Canon

(Wrongly attributed to J. Haydn, as well as W. Mozart)

Alles schweiget,

Nachtigallen

lokken mit suessen Melodien

Traenen ins Auge,

Schwermut ins Herz.

Everything soars,

Nightingale's sweet melody

Brings tears to the eyes,

longing in the heart.

When is this song sung? Perhaps on one of the beautiful summer evenings in nature, maybe also at a singing lesson in the classroom. Of course, the nightingales are unlikely to be present at the same time. Here we are talking, first of all, not about the musical-speech display of an external event, but more about the expression of the inner world of feelings, for which the external world is only an unclear reason. The words speak for themselves: sweet melodies, tears, longing. The melody is composed entirely of the harmonic consonance of the three-voice canon and follows a simple but strong cadenza form. 11-12-year-old children (as well as those adults in whose souls something lives from the attitude of a 12-year-old child) will sing such a song with great dedication. A six-year-old child, having heard it or trying to sing it along with everyone, will remain indifferent to the beauty of the canon bordering on sentimentality.

A six-year-old child, having heard it or trying to sing it along with everyone, will remain indifferent to the beauty of the canon bordering on sentimentality.

In comparison with the Nightingale Canon, the originality of the song about the bird by Alois Künstler is very clearly visible. Attention should also be paid to how different the role of the meter is in both songs and how differently the composers deal with speech rhythm.

* * *

Life in the mood of a fifth, of course, includes not only musical experiences. Therefore, we are talking about the requirement for the parental home, kindergarten and elementary grades - to respect and understand this open perception of the world, which has the character of a fifth, and to meet it accordingly. The actual musical element here is only part of the picture. Songs and mobile musical games-dances today especially help to open up the shaky, frightened and, in a sense, “asleep” sense of hearing.

First published in Ditina #5-6, 2003.

Opposites attract: the story of a married couple from the Moscow Longevity project: New pensioner

Thursday, 07/08/2021, 09:53:01

Every year on July 8, Russia celebrates the Day of Family, Love and Fidelity. Alexander and Natalya Kazansky, participants in the Moscow Longevity project, celebrate the 50th anniversary of their married life on this very day. They registered their marriage on July 8, 1971 in Tashkent.

The spouses will spend a significant day surrounded by nine more anniversary couples from the Moscow Longevity project: on July 8, a festive online event will be held on the project’s YouTube channel. The central event will be a ceremony honoring married couples who are celebrating their golden wedding this year. The spouses will talk about the personal secrets of family longevity and put their signatures in the Book of Significant Events of the Shipilovsky registry office.

Natalya and Alexander Kazantsevs met in their student years when they studied at the same course at the Architectural Institute in Tashkent. Alexander is sure it was love at first sight. In the last year, the couple decided to tie the knot in their love. The Kazantsevs specifically chose the day of memory of the Orthodox saints Peter and Fevronia of Murom, the patrons of family and love, as the date of the wedding.

Alexander is sure it was love at first sight. In the last year, the couple decided to tie the knot in their love. The Kazantsevs specifically chose the day of memory of the Orthodox saints Peter and Fevronia of Murom, the patrons of family and love, as the date of the wedding.

Spouses admit - they are two opposites. But Natalya and Alexander are sure that these differences did not become a disadvantage, but only strengthened their marriage.

“My husband believes that our family is kept precisely by the fact that we are different. Of course, over time, we have common interests, children who unite us. But everyone still has their own passion and hobby. We respect each other's choice, we can always compromise and give the opportunity to live our own interests,” says Natalya Kazanskaya.

In the Moscow Longevity project, each of the spouses found a hobby to their liking. Alexander, before switching to a remote format, was engaged in fitness and table tennis, and Natalia was engaged in Nordic walking and English. The couple differ not only in hobbies, but also in characters. At the same time, the different temperaments of the couple perfectly complement and balance each other.

The couple differ not only in hobbies, but also in characters. At the same time, the different temperaments of the couple perfectly complement and balance each other.

“Sasha is the soul of our family. In the most difficult moments, when I lose my head and do not understand anything, he calms me down and amuses me. He has a lighter outlook on life than I do, ”Natalya shares.

The key to a strong relationship for a couple is respect, love and trust, as well as common bright and pleasant memories, which have accumulated a lot over 50 years.

You can find out the stories of other golden anniversaries of married life by connecting to the online broadcast at the link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pk8a0QFVAow.

The event will take place on July 8, 2021 at 14:00.

Category:

Calendar

Tags:

People Moscow About pensioners

Share:

Subscribe:

Subscribe to our newsletter to be the first to receive the most interesting news pension system in Russia, articles on legislation and law, information about charitable and social programs, an overview of cultural, sports, foreign and other news.