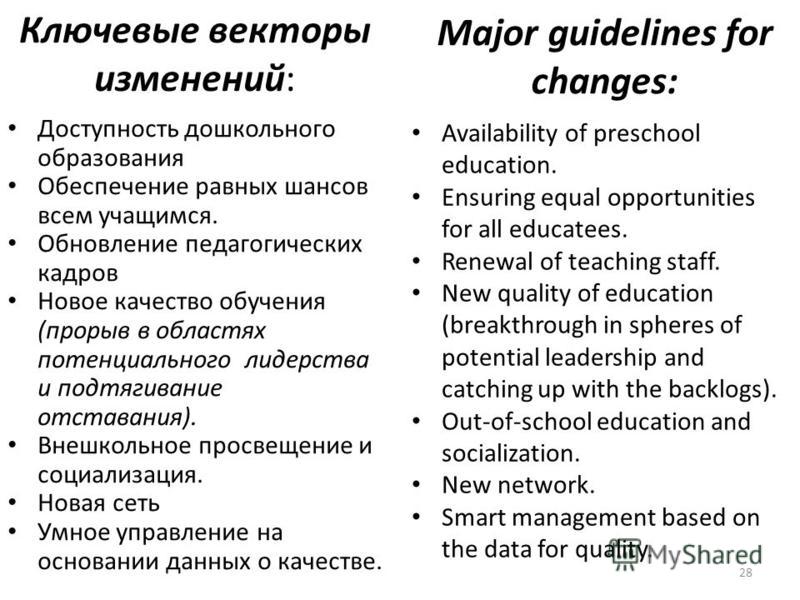

Preschool socialization skills

How to raise kind and competent kids

© 2006- 2020 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

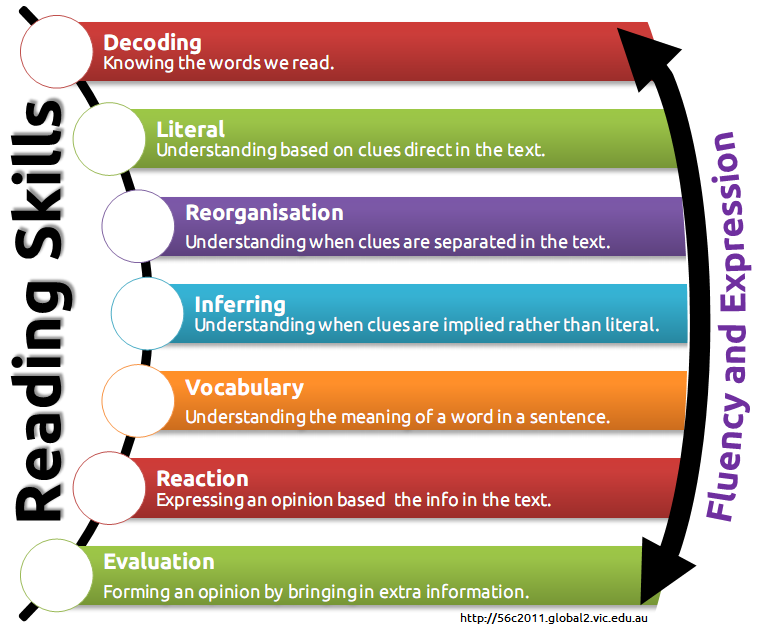

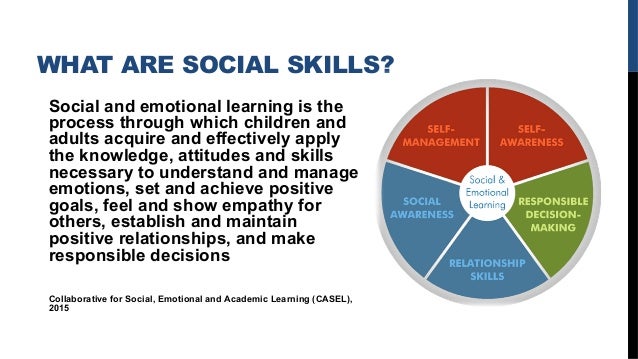

Preschool social skills depend several core competencies, including self-control, empathy, and verbal ability. And while they include a knowledge of basic etiquette — like knowing when to say “please” and “thank you” — the most crucial skills are psychological.

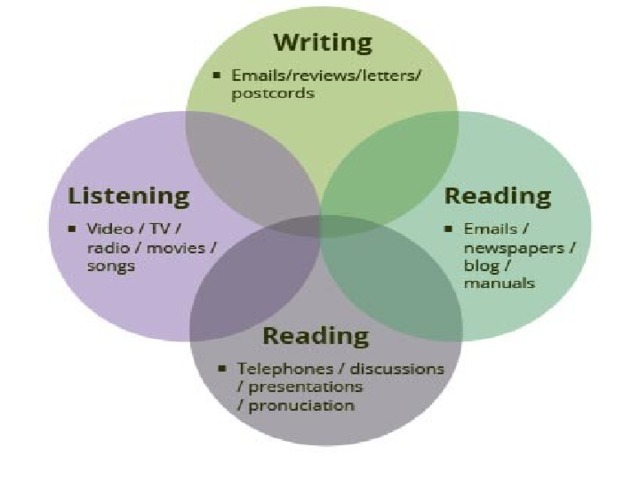

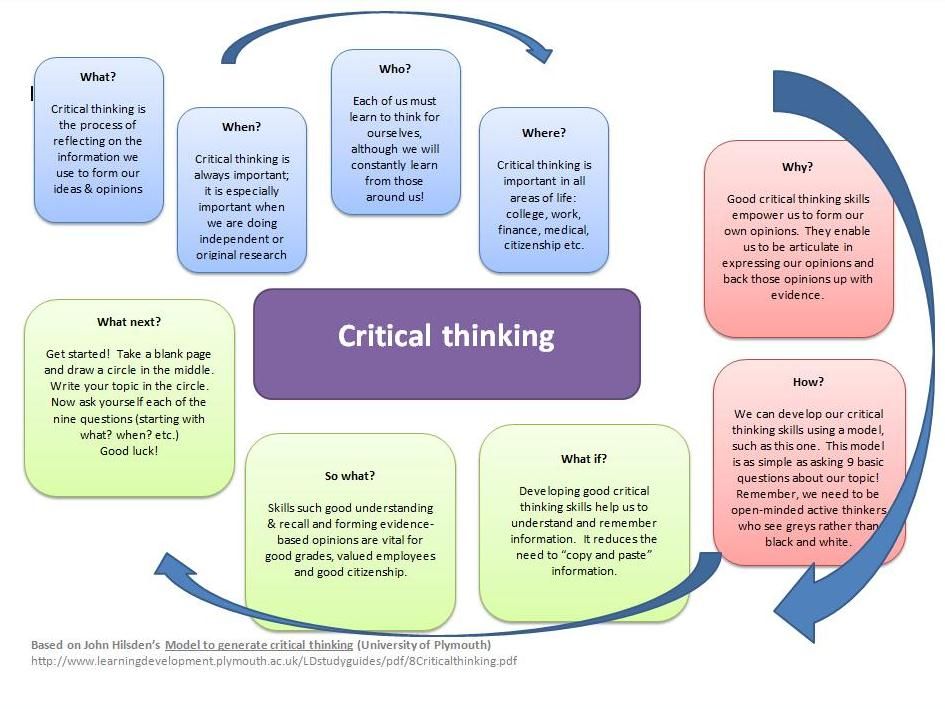

To become socially adept, kids need to learn a lot about emotions and human nature. They need to learn how to

- cope with negative emotions, like anger and sadness;

- pay attention the social cues around them;

- recognize what emotions other people are feeling;

- consider other perspective and points of view;

- notice when someone is struggling, and offer help;

- express sympathy;

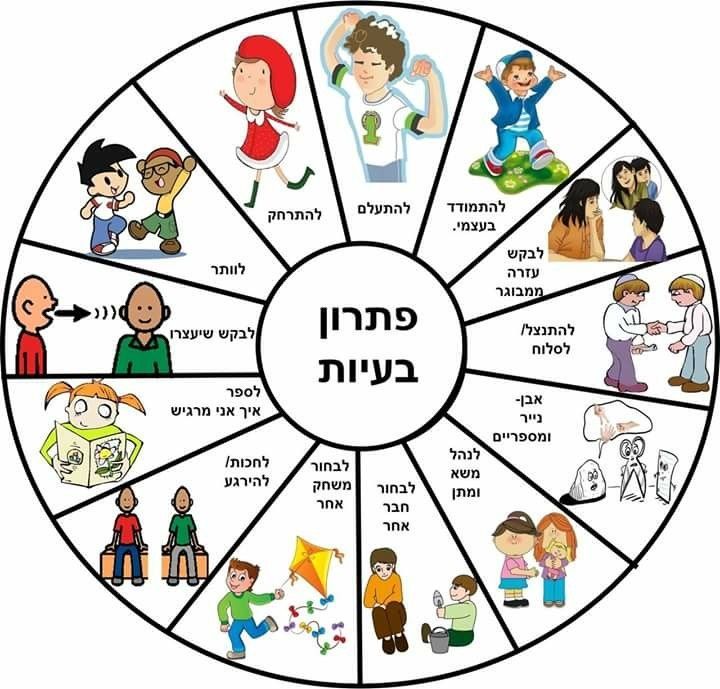

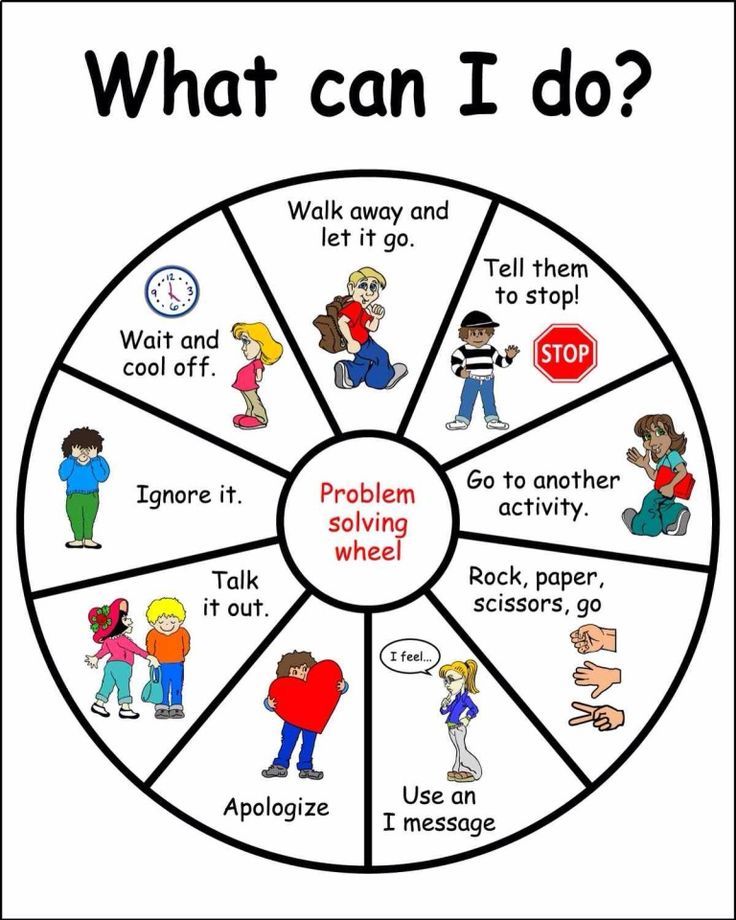

- resolve conflict without resorting to aggression;

- form and maintain friendships;

- offer forgiveness; and

- express remorse and make amends after a transgression.

That’s a lot to tackle, and there isn’t any one end point. We can keep honing our social abilities throughout our lives. But the rewards can be great.

Young children with strong social skills are more likely to be accepted by their peers (Blandon et al 2010). They are more likely to excel academically, and less likely to develop behavior problems (Arnold et al 2012; Bornstein et al 2012).

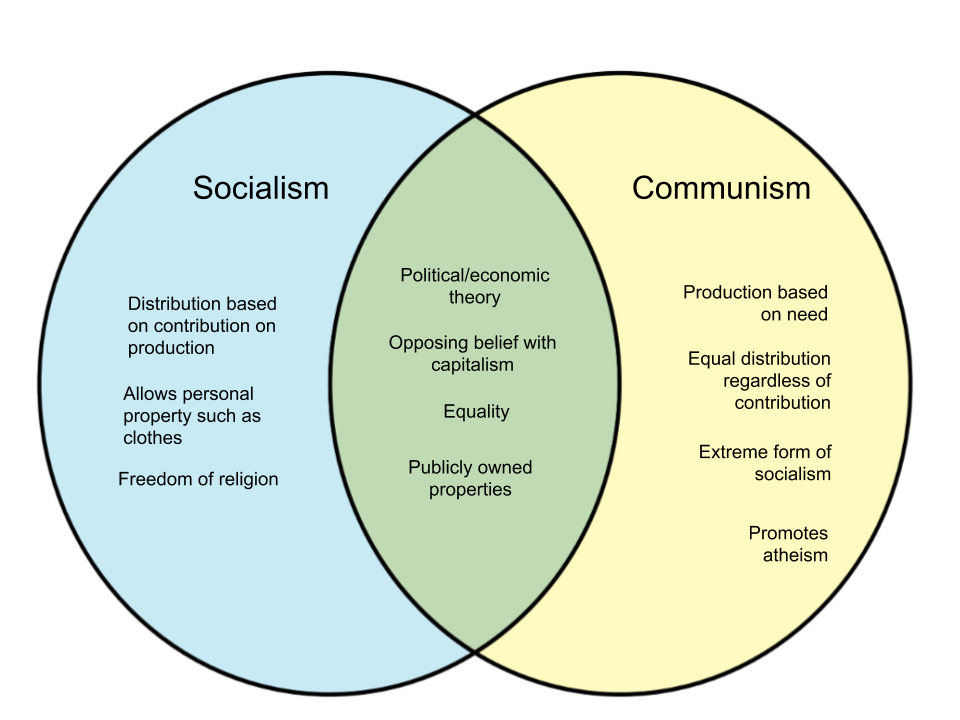

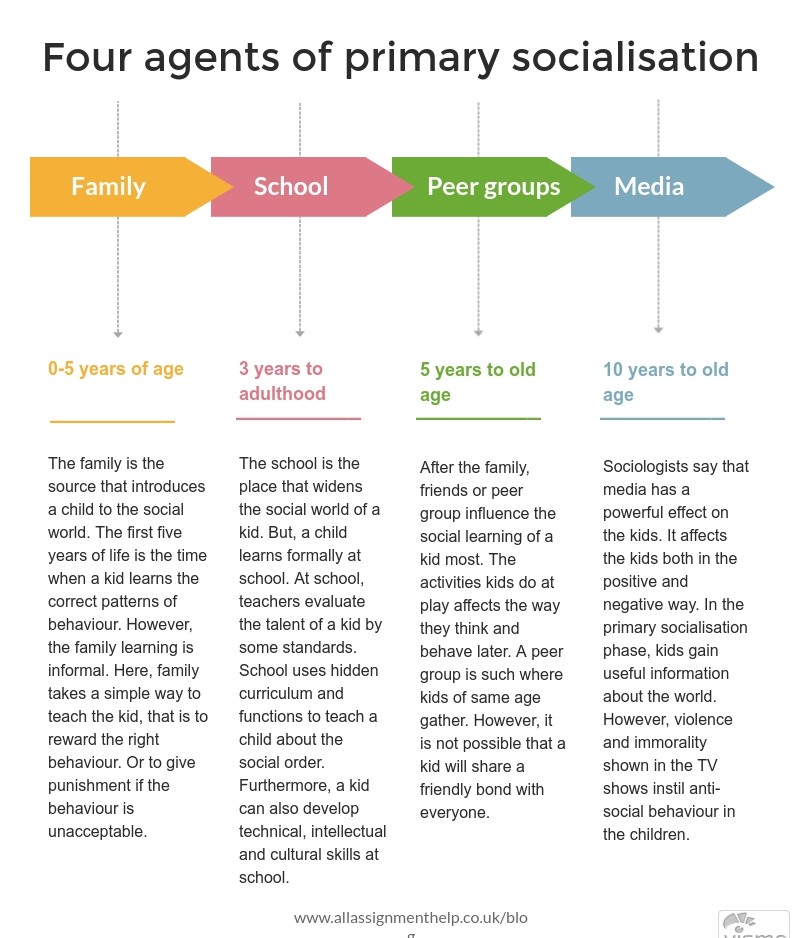

So how do we nurture preschool social skills? I’ve heard people claim that young children need to spend a lot of time with kids their own age. But history and anthropology tell us otherwise.

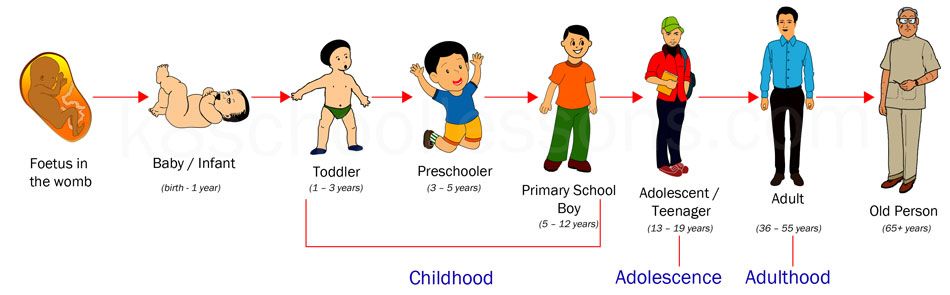

In most past societies, children socialized in mixed-age playgroups, not preschools. Toddlers learned crucial social skills from adults, adolescents, and older children — not from other toddlers. And how could it be otherwise?

Young children are less likely to model the right behaviors and responses. They are social novices, so they aren’t the best social tutors.

No, the most helpful social influences are older kids, teens, and adults. They’re more experienced and knowledgeable. They have a more extensive emotional and cognitive tool kit for solving problems, making them more reliable role models.

They’re more experienced and knowledgeable. They have a more extensive emotional and cognitive tool kit for solving problems, making them more reliable role models.

And parents? Parents are especially important. They don’t merely serve as potential role models and tutors. They also shape their children’s early environment — making kids feel secure; buffering kids from stress; helping ensure that kids get enough sleep. And all of these things have an impact on social behavior.

So here are some suggestions for boosting your child’s social-savvy: Evidence-based tips for fostering preschool social skills.

1. Maintain a loving, secure relationship with your child.

When parents show themselves to be caring and dependable — sensitive and responsive to their children’s needs — children are more likely to develop secure attachment relationships.

And children who are securely-attached are more likely to show social competence (Groh et al 2014; Rydell et al 2005). For instance:

For instance:

- Preschoolers with secure attachments at ages 2 and 3 have demonstrated greater ability to solve social problems, and less evidence of loneliness (Raikes and Thompson 2008).

- Young children with secure attachments are more likely to show empathy, and come to the aid of people in distress (Waters et al 1979; Kestenbaum et al 1989; Barnett 1987; Elicker et al 1992).

- Preschoolers with more secure attachments are more likely to share, and more likely to show generosity towards individuals they don’t like (Paulus et al 2016).

Why are secure attachments connected with social competence?

It probably has something to do with stress. As I note elsewhere, secure attachments buffer kids from the effects of toxic stress. Kids are less likely to experience anxiety. They are less likely to feel threatened.

So securely-attached children probably feel more comfortable reaching out to others, and they are better able to focus on learning social skills.

This causal pathway may be particularly strong for some kids. Studies indicate that some individuals possess genes that make them especially sensitive to the beneficial effects of secure attachment relationships (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al 2008; Bakermans-Kranenburg and van Iizendoorn 2011; Knafo et al 2011; Kochanska et al 2011).

But let’s be clear: Sensitive, responsive parenting doesn’t guarantee that your child will become a social super-star. It doesn’t even guarantee that your child will become securely-attached. Many other factors — including genetic factors — also play a role.

For example, a child’s ability to pay attention is influenced, in part by genetic factors (Faraone and Larsson 2018). And poor attention skills can interfere with both the development of secure attachments and the development of social skills (Storebø et al 2016; Papp et al 2013).

So sensitive, responsive parenting shouldn’t be the only item on our checklist. The development of secure attachments — and social skills — is more complicated than that. But sensitive, responsive parenting is a crucial starting point. You can read more about the many health benefits of sensitive, responsive parenting in this Parenting Science article.

But sensitive, responsive parenting is a crucial starting point. You can read more about the many health benefits of sensitive, responsive parenting in this Parenting Science article.

2. Be your child’s “emotion coach.”

Emotional competence is the key to strong preschool social skills (Denham 1997). The better children understand emotions, the more they are liked by peers (Denham et al 1990; McDowell et al 2000).

For example, shy children are at greater risk of being rejected by peers, but when shy children possess a well-developed ability to recognize emotions, this risk is much reduced (Sette et al 2016).

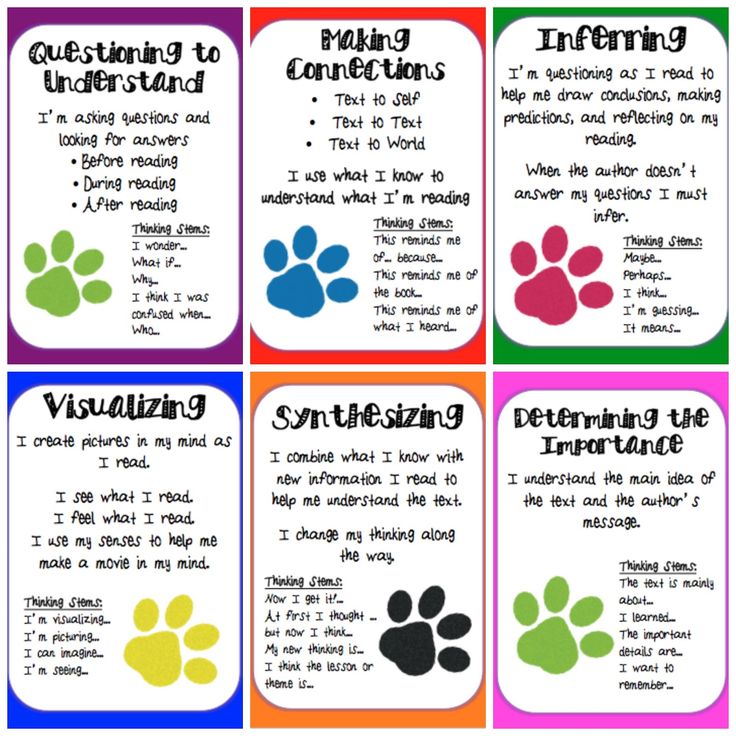

So how can we help kids understand emotions? By engaging them in conversation. By talking with them the situations and events that trigger emotions.

What makes us feel angry? What makes us feel sad? What makes us feel happy? Worried? Frightened? When adults explain emotions and their causes — and share constructive suggestions for coping with negative feelings — kids learn how to better regulate themselves.

In one study, parents who used “more frequent, more sophisticated” language about emotions had kids who could better cope with anger and disappointment (Denham et al 1992).

In another, parents who were specifically encouraged to coach their children were rewarded with improvements in behavior. Preschoolers were better able to handle their frustration (Loop and Roskam 2016).

For advice about helping kids understand emotions, check out my guide to being your child’s emotion coach.

In addition, see the Parenting Science article, “Teaching empathy: Evidence-based tips for fostering empathy in children.”

3. Be calm and supportive when children are upset, and don’t dismiss their negative emotions.

This goes hand in hand with being your child’s emotion coach. When a child launches into a seemingly irrational crying jag, it’s natural to want to shut him or her up. But simply telling a child to be quiet doesn’t help that child learn.

Research suggests that children are more likely to develop social-emotional competence if we acknowledge bad feelings, and show children better ways to solve their problems. Examples?

Examples?

In a study tracking toddlers for twelve months, parents who took this approach were more likely to end up with highly prosocial children. This was true even after researchers adjusted for a child’s initial tendencies to (1) become distressed, and (2) engage in prosocial acts (Eisenberg et al 2017).

Other studies indicate that young children who receive emotional support are less likely to direct negative emotions at peers (Denham 1989; Denham and Grout 1993). They are also better liked by peers (Sroufe et al 1984), and rated as more socially-competent by teachers (Denham et al 1990; Denham 1997).

4. Make sure your child is getting enough sleep.

You’ve already noticed that a poor night’s sleep makes your child moody and less attentive. But what if the condition is chronic? What it a child experiences a regular sleep deficit?

Studies keep telling us the same thing: Sleep duration is linked with social skills and behavior problems.

For example, in a study of preschoolers, researchers found that kids were more likely to exhibit good social and emotional skills if they logged more time asleep each night. These good sleepers were also more likely to be accepted by their peers (Vaughn et al 2015).

These good sleepers were also more likely to be accepted by their peers (Vaughn et al 2015).

And another study found that preschoolers with sleep problems were more likely to develop attention and hyperactivity problems (Touchette et al 2007) — problems that impact a child’s social functioning.

So it’s important not to overlook the impact of good sleep habits. Having trouble? See this Parenting Science guide to solving bedroom problems.

5. Practice inductive discipline.

Across the world, many parents use inductive discipline, the practice of explaining the reasons for rules, and talking — calmly and sensitively — with children when they misbehave (Robinson et al 1995).

Inductive discipline is one of the key components of authoritative parenting, a style of child-rearing associated with fewer behavior problems. And there is evidence that this conversational approach to discipline promotes the development of empathy and moral awareness (Krevans and Gibbs 1996; Knafo and Plomin 2006; Patrick and Gibbs 2012; Spinrad and Gal 2018).

For example, in a study that tracked approximately 300 preschoolers over the course of three years, Deborah Laible and her colleagues found that children were more prosocial if their mothers practiced inductive discipline (Laible et al 2017).

And an earlier study found that the preschool children of “inductive” mothers were more prosocial, and more popular with peers. They were also less likely to engage in disruptive, anti-social behavior (Hart et al 1992).

Are you struggling with such behavior? Check out these evidence-based tips for handling aggression and defiance in children.

And for general tips on how to keep kids on track without resorting to threats and punishments, see my positive parenting tips.

6. Seize everyday opportunities to induce empathy.

Empathy is part of human nature. Even babies show signs of empathy. But that doesn’t mean that empathy develops automatically, without any feedback from the environment. The development of empathy depends, in part, on learning. And that’s something we can help kids with.

And that’s something we can help kids with.

If someone is suffering, we can call attention to the fact, and ask kids to imagine how that individual feels.

Research on elementary school students suggests that simply asking kids to reflect on someone else’s plight is enough to increase their feelings of empathy (Sierksma et al 2015).

And researchers have used training exercises in caring — asking kids to actively think about the emotions of other people — to foster greater empathy and social skills in preschoolers (Flook et al 2015).

7. Teach kids to take turns, and encourage them to practice turn-taking in everyday life.

Taking turns is essential for all sorts of social interactions. It promotes a sense of order, mutual respect, and reciprocity. And as Rodolfo Cortes Barragan and Carol Dweck discovered, it may even trigger acts of kindness.

In a series of experiments, the researchers showed that young children became more altruistic after engaging in a simple, reciprocal activity.

After a brief game — rolling a ball back and forth with stranger — these kids showed generosity toward their new playmate. Given the opportunity, they were more likely to share a prize.

By contrast, kids were less giving if they had experienced only “parallel play,” playing alongside a stranger, but without exchanging a ball (Cortes Barragan and Dweck 2014).

8. Inspire children with encouraging words —

not criticism.Young children thrive on praise, particularly when we praise their good choices and actions.

What about criticism? Here we must tread carefully, because kids can get the impression that we view them as inherently inferior or bad. And that perception undermines their motivation to improve.

So it’s advisable to avoid negative language when a child’s social behavior disappoints. Stop being mean. I can’t take you anywhere.You’re out of control! Why are you so shy? In the heat of the moment, such talk might seem justified. But it isn’t helpful, and you risk making things worse.

But it isn’t helpful, and you risk making things worse.

What works better is a constructive approach — challenging children to think of ways they could do better. Read more about it in my article, “Correcting behavior: The magic words that help kids cope with mistakes.

9. Provide children with free, unforced opportunities to experience the

emotional rewards of giving.Why do people act generously toward each other? There are many reasons. We feel empathic concern for people in need. We may feel a sense of responsibility. Or a moral imperative to act.

But there’s also a self-serving motive. Giving feels good. It gives us a pleasant rush. It lifts our mood. And even young children experience this effect (Paulus and Moore 2017).

So we can foster prosocial behavior by encouraging children to engage in everyday acts of generosity. Kids learn that good deeds are emotionally rewarding, and become more generous over time.

But be careful not to force the issue. When kids are forced to give, they probably won’t experience that pleasant, emotional rush. And an experience of “forced giving” doesn’t teach preschoolers to be more generous. On the contrary, it makes them less likely to engage in future acts of spontaneous generosity (Chernyak and Kushnir 2013).

When kids are forced to give, they probably won’t experience that pleasant, emotional rush. And an experience of “forced giving” doesn’t teach preschoolers to be more generous. On the contrary, it makes them less likely to engage in future acts of spontaneous generosity (Chernyak and Kushnir 2013).

Your best bet? Follow an approach tested by researchers: Provide your child with free, unforced opportunities to be generous. Is somebody sad? Does somebody need support? Talk with your child about what would make this person feel better, and allow your child to make a choice (Chernyak and Kushnir 2013).

10. Be careful about offering

material rewards for acts of kindness.Research on toddlers and primary school children suggests that we might undermine our kids’ impulses to be helpful when we bribe them with tangible rewards for being kind. For details, see this Parenting Science article on the perils of rewarding prosocial behavior.

If your child has social problems with peers, encourage a positive, constructive attitude. Let your child know that everybody gets rebuffed and rejected sometimes. In one study, about half of all preschooler social overtures were rejected by peers (Corsaro 1981).

Let your child know that everybody gets rebuffed and rejected sometimes. In one study, about half of all preschooler social overtures were rejected by peers (Corsaro 1981).

Kids with the strongest social skills treat rebuffs as temporary setbacks that can be improved. We can encourage this attitude by helping children interpret rejection in a less threatening light. Maybe doesn’t want to play because he’s shy. Maybe she just wants to play by herself right now.

In addition, we can help children brainstorm solutions, and encourage them to predict how different social tactics might work.

Such thought experiments encourage children to consider what other people are feeling (Zahn-Waxler et al 1979). They also help children to explore ways they can adapt and “fit in.”

For instance, a child who’s met with resistance (“You can’t play firefighter with us because there isn’t enough room in the fire engine”) might find another way to join the game (“Help! My house is on fire!”). This is one of the secrets of children with strong preschool social skills. They are responsive to the play of others, and they know how to mesh their behavior with the behavior of potential playmates (Mize 1995).

This is one of the secrets of children with strong preschool social skills. They are responsive to the play of others, and they know how to mesh their behavior with the behavior of potential playmates (Mize 1995).

12. Show kids how to apologize, make amends, and offer forgiveness.

Fascinating experiments on toddlers show that they understand the difference between the unintentional harm they cause and the harm caused by others. For example, when 2- and 3-year-olds believe they caused an accident, they feel a greater urge to help make things right (Hepach et al 2017).

Moreover, experiments indicate that young children notice when transgressors fail to apologize and offer to help. It might not lift a victim’s bad mood, but it can mend bad feelings toward the transgressor. When transgressors fail to reach out in this way, they harm their standing with peers. Over time, they may find themselves increasingly rejected by other kids.

So children are ready to learn about reconciliation, and have a natural incentive to do so. But what exactly should you do after you’ve gotten too pushy, and knocked over somebody’s castle of blocks? Or blurted out something mean-spirited that makes someone cry?

But what exactly should you do after you’ve gotten too pushy, and knocked over somebody’s castle of blocks? Or blurted out something mean-spirited that makes someone cry?

It can be hard for young children to figure out what to do in these situations. We can help by showing them concrete actions to take — how to speak up, apologize, pitch in to help reverse the damage, and offer the victim something cheering or friendly (like an opportunity to play a game together).

We can also show kids how to accept apologies with grace, and remember that everyone makes mistakes. It’s important for kids to adopt an effort-based mindset: An understanding that people aren’t good or bad, but rather imperfect individuals capable of learning from their mistakes.

Studies show this mindset protects children from feeling overwhelmed and helpless to change. For more information, see these Parenting Science articles about the effort mindset and ways that adults can help children adopt it.

13.

Model — and talk about — gratitude.

Model — and talk about — gratitude.Expressions of gratitude help grease the wheels of the social machine. They are essential for getting along in polite society. But experiments suggest that they also improve our mood and outlook. They make us feel less alienated, and more connected to friendly, caring others. In fact, just remembering a received kindness can make us more prosocial.

For these reasons, researchers who design preschool social skills programs emphasize the importance of gratitude.

In a preschool curriculum developed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, children read stories about the acts of everyday kindness that people perform for each other throughout the world. They learn about people in their communities who help others (like firefighters, doctors, and bus drivers), and take on the roles of these people through pretend play. Teachers share their own feelings of gratitude, and show, by example, how to express it (Flook et al 2015).

Researchers are making this curriculum available to the public for free. You can sign up for a copy here.

You can sign up for a copy here.

14. Introduce kids to cooperative games.

As I explain in this article, cooperative games are better-suited to the developmental capacities of preschoolers. And — like turn-taking games — cooperative games appear to encourage children to behave more generously toward each other (Toppe et al 2019).

15. Provide opportunities for pretend play with older kids and adults.

During the preschool years, pretend play is one of the most important ways that children forge friendships (Gottman 1983; Dunn and Cutting 1999).

Preschoolers who pretend together are less likely than other kids to quarrel or have communication problems (Dunn and Cutting 1999).

And dramatic pretend play — where kids act out specific scenarios, and portray the actions and emotions of different characters — may help children develop certain forms of self-control.

For example, a recent experimental study found that four-year-old kids improved their emotional control after participating in group sessions of dramatic pretend play (Goldstein and Lerner 2018).

So pretend play is a promising tool for buildling social competence, but keep in mind: Preschoolers may need a nudge from us to reap the full benefits.

In the experimental study of dramatic pretend play, the researchers didn’t just tell preschoolers to play make-believe. They assigned kids specific challenges (like, “put on a chef’s hat and bake me birthday cake”). Adults encouraged kids to “physically enact the games, and to stay on task” (Goldstein and Lerner 2018). And that adult involvement might have been crucial.

Another point to consider? It’s important to avoid being bossy. Research indicates that kids with strong preschool social skills have parents who play with them in a cheerful, collaborative, way (MacDonald 1987).

For more information, see my Parenting Science article about the benefits of play, including pretend play.

16. Don’t put off conversations about race.

This is a common miscalculation that some parents — especially white parents — make. They assume that their children are too young to begin talking about race. My child hasn’t even noticed that racial categories exist. And isn’t that a good thing? Won’t that help ensure that my child will grow up free of racial prejudice?

They assume that their children are too young to begin talking about race. My child hasn’t even noticed that racial categories exist. And isn’t that a good thing? Won’t that help ensure that my child will grow up free of racial prejudice?

It might seem intuitive. But studies confirm that our children are picking up on racial cues long before they have learned to speak. They get exposed to racial stereotypes in the popular culture. And when we fail to talk with our children, opening and honestly about race and racial bias in society, our kids are more likely to develop racial biases of their own.

For more information, see my article, “6 mistakes that white parents make about race.”

17. Choose TV content that is non-violent and age-appropriate.

Research suggests that it makes a difference.

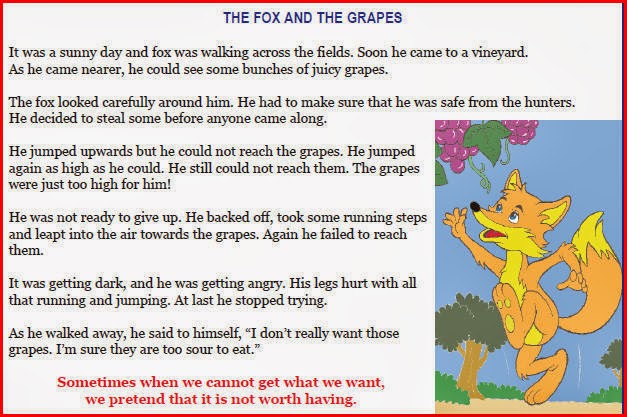

In a randomized, controlled study, Dimitri Christakis and his colleagues assigned some parents to substitute nonviolent, educational TV shows (like Sesame Street and Dora the Explorer) for the more violent programs their preschoolers usually watched.![]()

Six months later, children in this group exhibited better preschool social skills — and fewer behavior problems — than did children in the control group (Christakis et al 2013).

18. Realize that some forms of sharing are easier than others.

Some types of sharing are relatively easy for preschoolers. If there is a large supply of goodies to share, giving has little downside. But what if giving is a zero-sum game — like loaning your favorite toy to someone so you can’t play with it yourself?

As noted above (#8), such acts of generosity can make children feel good. But the good feelings arise when kids share voluntarily. When we try to force it, the tactic backfires. Kids end up feeling less generous in the future.

So we need to be patient, and recognize the challenges that children face when they are asked to share. Young children in particular can have more difficulty thinking beyond the here-and-now. If we ask them to loan their toy, they may have trouble believing that they will get their toy back. And, to be fair, sometimes the kids who borrow toys are reluctant to return them.

And, to be fair, sometimes the kids who borrow toys are reluctant to return them.

The takeaway? We should be selective about what we ask our kids to share, and avoid forcing the issue.

19. Break up cliques with a negative vibe, and watch out for peer rejection.

Sometimes kids bring out the worst in each other. For example, in one study researchers observed children during free play periods at a preschool. They noticed which kids tended to play together, and watched their behavior.

Some of the groups featured an unusual amount of emotion negativity and antisocial behavior, and these negative groups were rated as less socially competent by their teachers and parents.

Moreover, participation in a negative group was predictive of poor preschool social skills a year later (Denham et al 2001).

What should we do if we see this kind of negativity?

If kids are struggling with aggressive behavior problems, we need to teach how to handle conflicts peacefully. These Parenting Science tips can help. And sometimes it’s best to take the additional step of breaking up the clique — finding new playmates for your child to socialize with.

These Parenting Science tips can help. And sometimes it’s best to take the additional step of breaking up the clique — finding new playmates for your child to socialize with.

What if your child is on the recieving end of negative behavior — being rejected by peers? It’s equally important to get involved, and research suggests we can help kids by coaching them in the art of making friends.

Studies show that a single peer friendship can protect preschoolers from continued aggression and rejection (Criss et al 2002; Hodges et al 1999). And preschoolers are more likely to win over peers if they behave prosocially (Vitaro et al 1990; Cote et al 2002; Eisenberg et al 1999) and respond appropriately to conversation (Kemple et al 1992).

For tips on helping kids make friends, see this Parenting Science article.

20. Don’t take it personally.

Despite the popular Hollywood image of kids as wise cynics who know better than their parents, young children are hampered by a poorer understanding of the world.

For instance, they have trouble tracking the mental perspectives of other people. In particular, most children under the age of 4 haven’t yet mastered the notion that different people can believe different things–even things that are objectively false (Gopnik et al 1999).

So it’s not surprising that children also have trouble grasping the concept of a “lie” (Mascaro and Sperber 1999). Young children tend to characterize all false statements–even statements that a speaker believes to be true–as lies (Berthoud-Papandropoulou and Kilcher 2003).

And while they understand that lying is bad, they lack an older child’s ability to anticipate how their words will make other people feel. The impact of lying–and the morality of lies–is something they must learn.

If your preschooler says something rude or hurtful, don’t take it personally. But don’t ignore it either. Take the opportunity to explain how words can hurt our feelings. When your child gains insight into the power of words, he will improve his preschool social skills.

More reading

Looking for activities that promote social competence? See this Parenting Science guide to social skills activities for kids.

And for advice about helping kids develop friendships, see my article, “How to help kids make friends.”

A great deal of research has been conducted on preschool social skills. In addition to the scholarly references cited in this article, any introductory textbook on cognitive development should help you gain insight into your child’s preschool social skills.

Online, Jacquelyn Mize and Ellen Abell, professors of child development, offer a research-based guide to teaching preschool social skills in “Encouraging social skills in young children: Tips teachers can share with parents.”

You will also find advice about preschool social skills in chapters 7-8 of Einstein Never Used Flash Cards (2004) by K. Hirsh-Pasek, R. Michnick Golinkoff, and D. Eyer.

If you found this article on preschool social skills helpful, check out other offerings at ParentingScience. com.

com.

Image credits for “Preschool social skills”:

image of preschoolers eating lunch on the grass by iStock / Nicole S. Young

image of father and son with basketball by istock monkeybusiness images

image of sleeping girl by istock/ Deepak Sethi

image of father talking to toddler boy in bed by istock / Liderina

image of girl covering eyes and boy smiling by shutterstock / YanLev

woman smiling at child with plastic nesting cups by Rawpixel / istock

image of young boy consoling toddler on the beach by KarinaBost / istock

Content last modified 12/2020

Social Development in Preschoolers - HealthyChildren.org

During your child's preschool-age years, they'll discover a lot about themselves and interacting with people around them.

Once they reach age three, your child will be much less selfish than they were before. They'll also be less dependent on you, a sign that their own sense of identity is stronger and more secure. Now they'll actually play with other children, interacting instead of just playing side by side. In the process, they'll recognize that not everyone thinks exactly as they do and that each of their playmates has many unique qualities, some attractive and some not. You'll also find your child drifting toward certain kids and starting to develop friendships with them. As they create these friendships, children discover that they, too, each have special qualities that make them likable—a revelation that gives a vital boost to self-esteem.

Now they'll actually play with other children, interacting instead of just playing side by side. In the process, they'll recognize that not everyone thinks exactly as they do and that each of their playmates has many unique qualities, some attractive and some not. You'll also find your child drifting toward certain kids and starting to develop friendships with them. As they create these friendships, children discover that they, too, each have special qualities that make them likable—a revelation that gives a vital boost to self-esteem.

There's some more good news about your child's development at this age: As they become more aware of and sensitive to the feelings and actions of others, they'll gradually stop competing and will learn to cooperate when playing with her friends. They take turns and share toys in small groups, though sometimes they won't. But instead of grabbing, whining, or screaming for something, they'll actually ask politely much of the time. You can look forward to less aggressive behavior and calmer play sessions. Three-year-olds are able to work out solutions to disputes by taking turns or trading toys.

Three-year-olds are able to work out solutions to disputes by taking turns or trading toys.

Learning how to cooperate

However, particularly in the beginning, you'll need to encourage this cooperation. For instance, you might suggest that they "use their words" to deal with problems instead of acting out. Also, remind them that when two children are sharing a toy, each gets an equal turn. Suggest ways to reach a simple solution when your child and another child want the same toy, such as drawing for the first turn or finding another toy or activity. This doesn't work all the time, but it's worth a try. Also, help children with the appropriate words to describe their feelings and desires so that they don't feel frustrated. Above all, show by your own example how to cope peacefully with conflicts. If you have an explosive temper, try to tone down your reactions in their presence. Otherwise, they'll mimic your behavior whenever they're under stress.

When anger or frustration gets physical

No matter what you do, however, there probably will be times when your child's anger or frustration becomes physical. When that happens, restrain them from hurting others, and if they don't calm down quickly, move them away from the other children. Talk to them about her feelings and try to determine why they're so upset. Let them know you understand and accept her feelings, but make it clear that physically attacking another child is not a good way to express these emotions.

When that happens, restrain them from hurting others, and if they don't calm down quickly, move them away from the other children. Talk to them about her feelings and try to determine why they're so upset. Let them know you understand and accept her feelings, but make it clear that physically attacking another child is not a good way to express these emotions.

Saying sorry

Help them see the situation from the other child's point of view by reminding them of a time when someone hit or screamed at them, and then suggest more peaceful ways to resolve their conflicts. Finally, once they understand what they've done wrong—but not before—ask them to apologize to the other child. However, simply saying "I'm sorry" may not help your child correct their behavior; they also needs to know why they're apologizing. They may not understand right away, but give it time; by age four these explanations will begin to mean something.

Make-believe play

Fortunately, the normal interests of three-year-olds keep fights to a minimum. They spend much of their playtime in fantasy activity, which tends to be more cooperative than play that's focused on toys or games. As you've probably already seen, preschooler enjoy assigning different roles in an elaborate game of make-believe using imaginary or household objects. This type of play helps develop important social skills, such as taking turns, paying attention, communicating (through actions and expressions as well as words), and responding to one another's actions. And there's still another benefit: Because pretend play allows children to slip into any role they wish—including superheroes or the fairy godmother—it also helps them explore more complex social ideas. Plus it helps improve executive functioning such as problem-solving

They spend much of their playtime in fantasy activity, which tends to be more cooperative than play that's focused on toys or games. As you've probably already seen, preschooler enjoy assigning different roles in an elaborate game of make-believe using imaginary or household objects. This type of play helps develop important social skills, such as taking turns, paying attention, communicating (through actions and expressions as well as words), and responding to one another's actions. And there's still another benefit: Because pretend play allows children to slip into any role they wish—including superheroes or the fairy godmother—it also helps them explore more complex social ideas. Plus it helps improve executive functioning such as problem-solving

By watching the role-playing in your child's make-believe games, you may see that they're beginning to identify their own gender and gender identity. While playing house, boys naturally will adopt the father's role and girls the mother's, reflecting whatever they've noticed in the hemworld around them.

Development of gender roles & identity

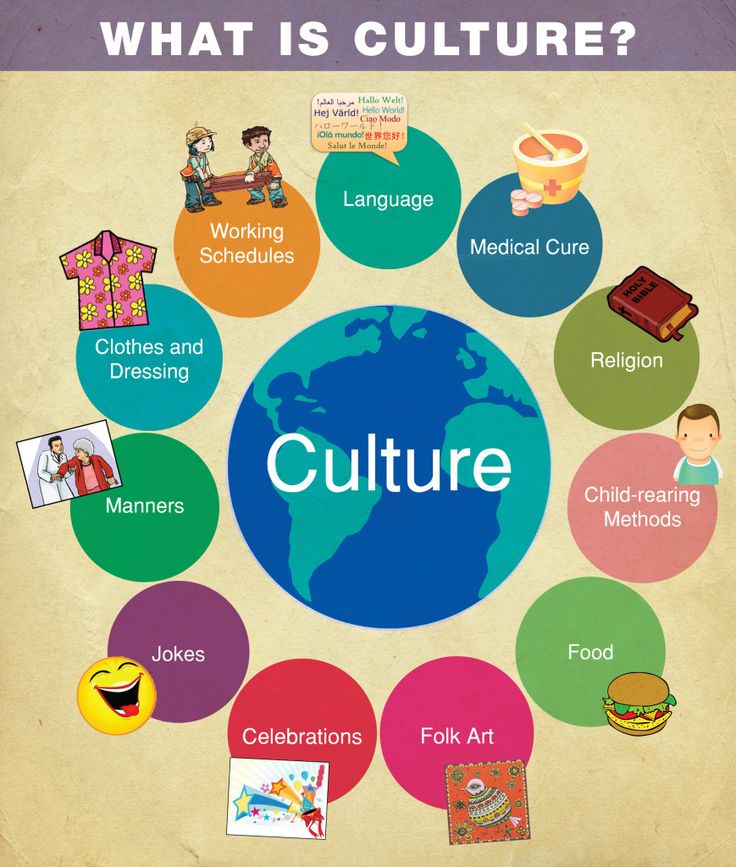

Research shows that a few of the developmental and behavioral differences that typically distinguish boys from girls are biologically determined. Most gender-related characteristics at this age are more likely to be shaped by culture and family. Your daughter, for example, may be encouraged to play with dolls by advertisements, gifts from well-meaning relatives, and the approving comments of adults and other children. Boys, meanwhile, may be guided away from dolls in favor of more rough-and-tumble games and sports. Children sense the approval and disapproval and adjust their behavior accordingly. Thus, by the time they enter kindergarten, children's gender identities are often well established.

As children start to think in categories, they often understand the boundaries of these labels without understanding that boundaries can be flexible; children this age often will take this identification process to an extreme. Girls may insist on wearing dresses, nail polish, and makeup to school or to the playground. Boys may swagger, be overly assertive, and carry their favorite ball, bat, or truck everywhere.

Boys may swagger, be overly assertive, and carry their favorite ball, bat, or truck everywhere.

On the other hand, some girls and boys reject these stereotypical expressions of gender identity, preferring to choose toys, playmates, interests, mannerisms, and hairstyles that are more often associated with the opposite sex. These children are sometimes called gender expansive, gender variant, gender nonconforming, gender creative, or gender atypical. Among these gender expansive children are some who may come to feel that their deep inner sense of being female or male—their gender identity—is the opposite of their biologic sex, somewhere in between male and female, or another gender; these children are sometimes called transgender.

Given that many three-year-old children are doubling down on gender stereotypes, this can be an age in which a gender-expansive child stands out from the crowd. These children are normal and healthy, but it can be difficult for parents to navigate their child's expression and identity if it is different from their expectations or the expectations of those around them.

Experimenting with gender attitudes & behaviors

As children develop their own identity during these early years, they're bound to experiment with attitudes and behaviors of both sexes. There's rarely reason to discourage such impulses, except when the child is resisting or rejecting strongly established cultural standards. If your son wanted to wear dresses every day or your daughter only wants to wear sport shorts like her big brother, allow the phase to pass unless it is inappropriate for a specific event. If the child persists, however, or seems unusually upset about their gender, discuss the issue with your pediatrician.

Your child also may imitate certain types of behavior that adults consider sexual, such as flirting. Children this age have no mature sexual intentions, though; they mimic these mannerisms. If the imitation of sexual behavior is explicit, though, they may have been personally exposed to sexual acts. You should discuss this with your pediatrician, as it could be a sign of sexual abuse or the influence of inappropriate media or videogames.

Play sessions: helping your child make friends

By age four, your child should have an active social life filled with friends, and they may even have a "best friend." Ideally, they'll have neighborhood and preschool friends they see routinely. But what if your child is not enrolled in preschool and doesn't live near other children the same age? In these cases, you might arrange play sessions with other preschoolers. Parks, playgrounds, and preschool activity programs all provide excellent opportunities to meet other children.

Once your preschooler has found playmates they seems to enjoy, you need to take initiative to help build their relationships. Encourage them to invite these friends to your home. It's important for your child to "show off" their home, family, and possessions to other children. This will establish a sense of self-pride. Incidentally, to generate this pride, their home needn't be luxurious or filled with expensive toys; it needs only be warm and welcoming.

It's also important to recognize that at this age your child's friends are not just playmates. They also actively influence their thinking and behavior. They'll desperately want to be just like them, even when they break rules and standards you've taught them rrm birth. They now realize there are other values and opinions besides yours, and they may test this new discovery by demanding things you've never allowed him—certain toys, foods, clothing, or permission to watch certain TV programs.

Testing limits

Don't despair if your child's relationship with you changes dramatically in light of these new friendships. They may be rude to you for the first time in their life.Hard as it may be to accept, this sassiness actually is a positive sign that they're learning to challenge authority and test their independence. Once again, deal with it by expressing disapproval, and possibly discussing with them what they really mean or feel. If you react emotionally, you'll encourage continued bad behavior. If the subdued approach doesn't work and they persist in talking back to you, a time-out (or time-in) is the most effective form of punishment.

If the subdued approach doesn't work and they persist in talking back to you, a time-out (or time-in) is the most effective form of punishment.

Bear in mind that even though your child is exploring the concepts of good and bad, they still have an extremely simplified sense of morality. When they obey rules rigidly, it's not necessarily because they understand them, but more likely because they wants to avoid punishment. In their mind, consequences count but not intentions. When theybreaks something of value, they'll probably assume they are bad, even if they didn't brea it on purpose. They need to be taught the difference between accidents and misbehaving.

Separate the child from their behavior

To help them learn this difference, you need to separate them from their behavior. When they do or say something that calls for punishment, make sure they understand they are being punished for the act not because they're "bad." Describe specifically what they did wrong, clearly separating person from behavior. If they are picking on a younger sibling, explain why it is wrong rather than saying "You're bad." When they do something wrong without meaning to, comfort them and say you understand it was unintentional. Try not to get upset, or they'll think you're angry at them rather than about what they did.

If they are picking on a younger sibling, explain why it is wrong rather than saying "You're bad." When they do something wrong without meaning to, comfort them and say you understand it was unintentional. Try not to get upset, or they'll think you're angry at them rather than about what they did.

It's also important to give your preschooler tasks that you know they can do and then praise them when they do them well. They are ready for simple responsibilities, such as setting the table or cleaning their room. On family outings, explain that you expect them to behave well, and congratulate them when they do. Along with responsibilities, give them ample opportunities to play with other children, and tell him how proud you are when they shares or is helpful to another child.

Sibling relationships

Finally, it's important to recognize that the relationship with older siblings can be particularly challenging, especially if the sibling is three to four years older. Often your four-year-old is eager to do everything their older sibling is doing; just as often, your older child resents the intrusion. They may resent the intrusion on their space, their friends, their more daring and busy pace, and especially their room and things. You often become the mediator of these squabbles. It's important to seek middle ground. Allow your older child their own time, independence, and private activities and space; but also foster cooperative play appropriate. Family vacations are great opportunities to enhance the positives of their relationship and at the same time give each their own activity and special time.

They may resent the intrusion on their space, their friends, their more daring and busy pace, and especially their room and things. You often become the mediator of these squabbles. It's important to seek middle ground. Allow your older child their own time, independence, and private activities and space; but also foster cooperative play appropriate. Family vacations are great opportunities to enhance the positives of their relationship and at the same time give each their own activity and special time.

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

Socialization skills in preschool children

2020 has shown us that communication is very important. Not only outside, but also on the scale of one apartment.

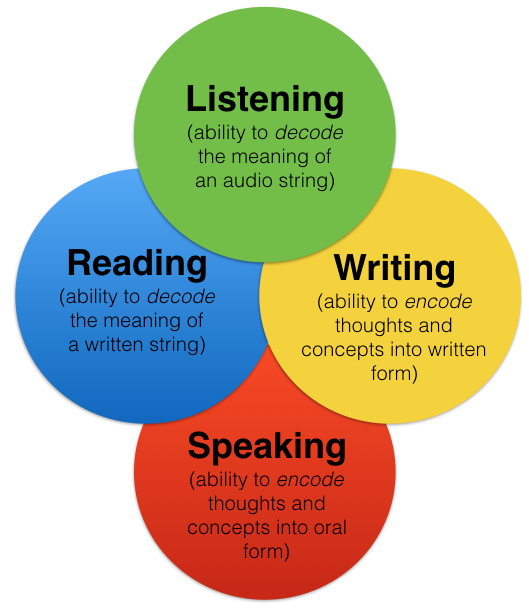

First of all, you need to understand that communication is a skill of effective communication. This is the ease in establishing contact, maintaining a conversation, the ability to negotiate and defend one's interests.

This is the ease in establishing contact, maintaining a conversation, the ability to negotiate and defend one's interests.

Every parent asks the question "when and how to socialize a child?" and “is it possible to compensate for communication skills at home without going to kindergarten?” nine0003

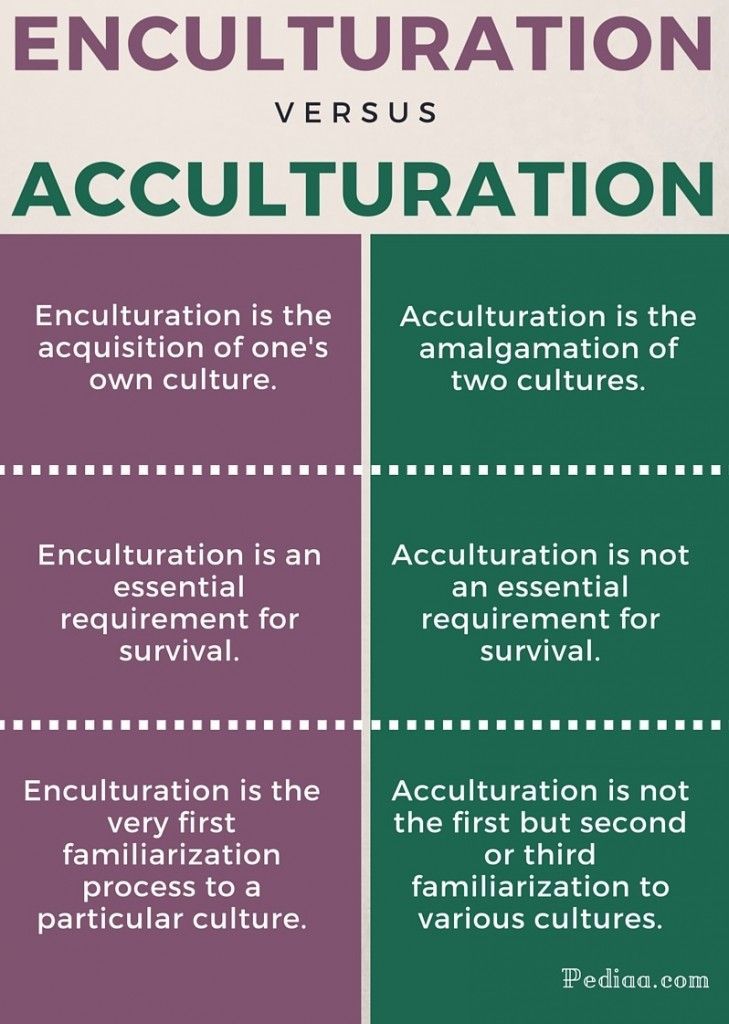

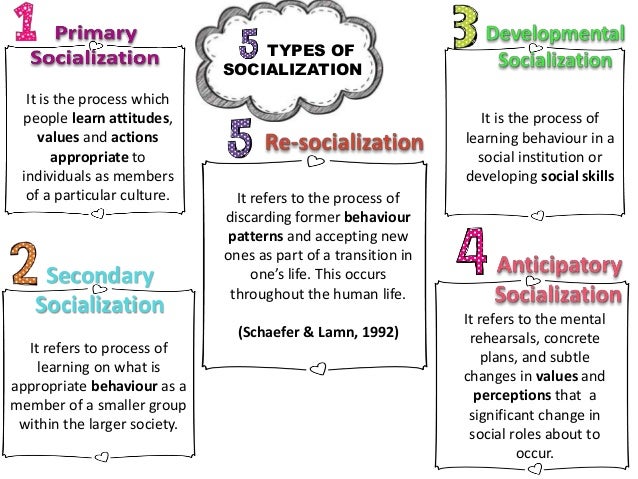

Let's figure it out. A child's communication begins at birth. The newborn "reads" the behavior and reactions of the parents. It adapts to them and shows its desires with its behavior. At this age, the only tool a child has is crying. With tears, the child conveys to the parent all his desires, worries, attracts attention. With age, more and more tools for communication appear and the range of interests of the child expands. Of course, a child should receive a number of skills at home. Namely: what is the "correct" way of life should be in the family. How relationships are built between its members, what kind of hierarchy is in the house, the appropriateness of behavior and reactions to situations. This is all the child will embody, including in adulthood. And here it is important to understand the possible consequences of the actions of parents in relation to children or in general in the family. For example, consider several situations. nine0003

This is all the child will embody, including in adulthood. And here it is important to understand the possible consequences of the actions of parents in relation to children or in general in the family. For example, consider several situations. nine0003

- If you overly admire the actions of a child and indulge all whims, then this can lead to the fact that he will grow up pampered and capricious, will painfully perceive the lack of adoration from other people;

- If a child is taught that it is important to observe only outward decorum, then in the future he may grow up to be a hypocrite;

- If a child is constantly punished for every wrongdoing or disobedience, then this can lead to a self-perception "I am a difficult child";

- If the child's desire to help ignore or praise someone else, then this can become the basis for the development of envy and self-doubt; nine0003

But let's assume that the parents don't make possible mistakes. Will parents, especially in the context of a pandemic and confined spaces, be able to replace their child's communication with a peer and harmoniously develop communication skills?

Will parents, especially in the context of a pandemic and confined spaces, be able to replace their child's communication with a peer and harmoniously develop communication skills?

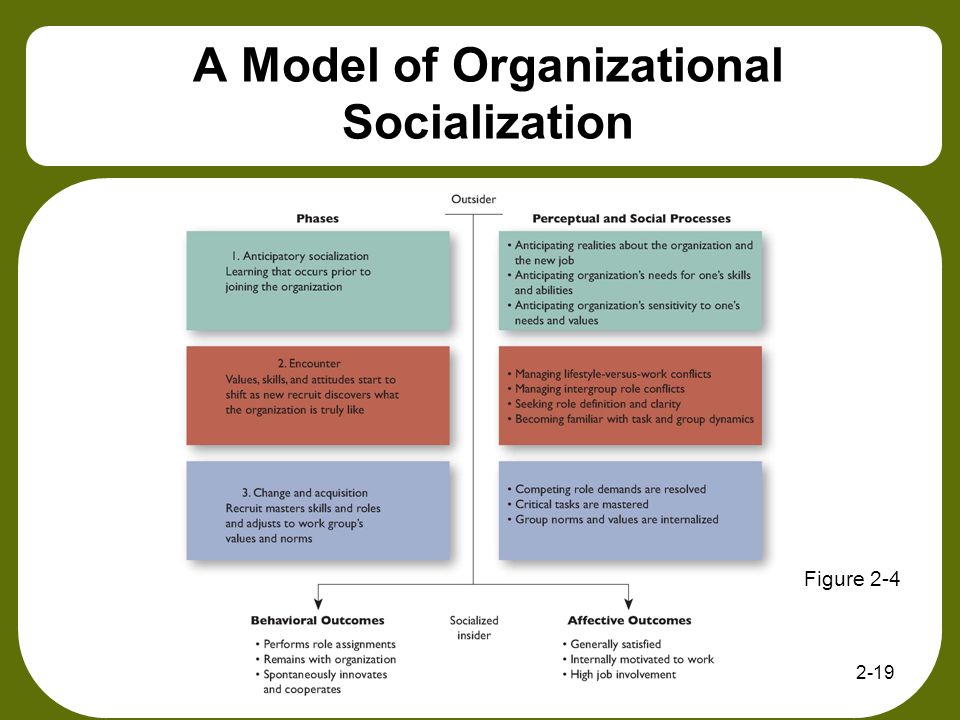

What a child learns in communication:

-

Introduce yourself and get to know each other. But how will he learn this with the parents he has known all his life?

-

Negotiate and play together. How do parents model possible situations and reactions of other children? And even if we imagine that at some point the mother will begin to play the situation, for example, a greedy boy or a bully boy, will the child be able to correctly understand why his beloved mother offends him? nine0003

-

Explain exactly what the child needs and why. Everything is a little simpler here, but just like in the previous case, not all situations can be modeled by parents and show the whole range of possible reactions of their peers.

Let's look at the most popular qualities that parents want to see in their children:

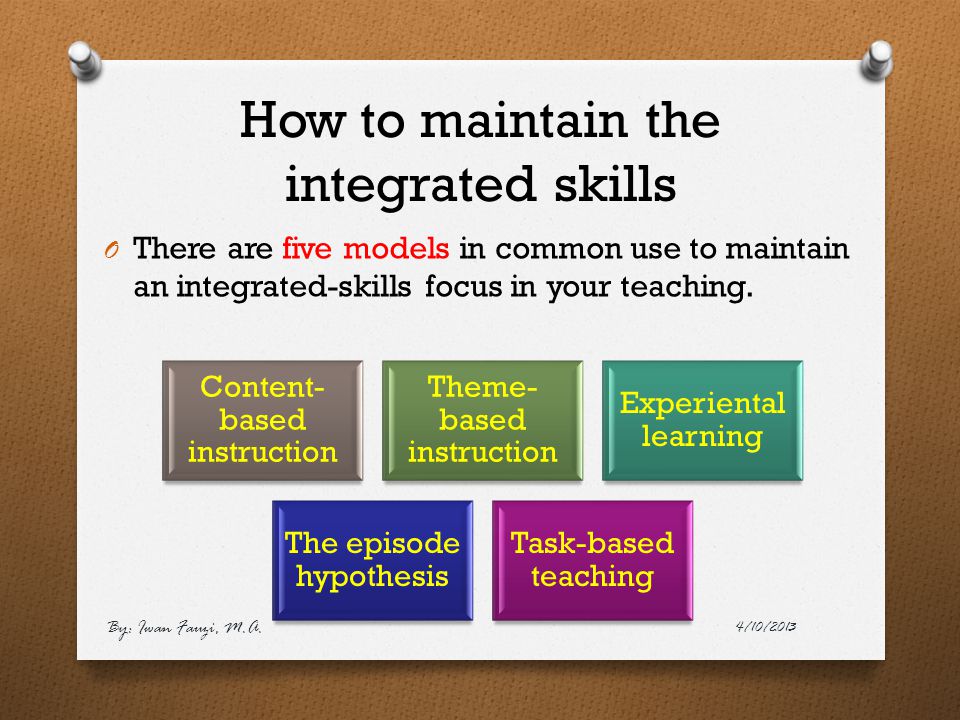

-

Leadership. The child must learn to take responsibility for the decisions he makes and the people around him. For example, if no one wants to play, it should not be difficult for the child to suggest or organize the game himself. If all the time parents organize games or solve all problems, then the child will be passive. Of course, a child can try to involve his parents in the game, try to show himself, but adults always have a lot of worries, household chores or remote work, and they are not up to games. Then the child becomes invisible to himself. nine0003

-

Work in a group or team. Having learned to work in a group, the child will not be afraid to follow the rules of the game, accept his role and enjoy it. The family is certainly also a group, but a group with already formed rules.

A family cannot be different every day - this would lead to a violation of the family model itself.

A family cannot be different every day - this would lead to a violation of the family model itself. -

Emotional intelligence. This skill helps to manage your emotions, avoid neurosis, depression and apathy in time. The spectrum of emotions is wide, and all of them are important: both positive and negative. It is also important to feel them in the right dosage and in the right situational conditions. Will parents be able to correctly model situations and predict how the child will react to them. And keep the line so as not to turn the life of a child into a theater. nine0003

There have always been and will always be parents who are against socialization through preschool institutions. They believe that 30-60 minutes of “dosed” society per day in the form of developmental or sports sections is enough for a child to form communication skills. But they do not take into account that children are subject at that moment to the rules of the lesson or the purpose of the lesson and do not have the opportunity for free communication and the exchange of personal experience. Of course, the pandemic has made its own adjustments, fear for the family: no one wants to get sick with an insidious virus. And this pushes parents to isolation from society. It is important to evaluate all the consequences of your actions. After all, a person pathologically needs communication, it is it that gives all the benefits and satisfactions. And an important duty of a parent is the need not only to provide a healthy and safe childhood, but also to give him all the tools so that he grows into a happy person. And that tool is communication skills. nine0003

Of course, the pandemic has made its own adjustments, fear for the family: no one wants to get sick with an insidious virus. And this pushes parents to isolation from society. It is important to evaluate all the consequences of your actions. After all, a person pathologically needs communication, it is it that gives all the benefits and satisfactions. And an important duty of a parent is the need not only to provide a healthy and safe childhood, but also to give him all the tools so that he grows into a happy person. And that tool is communication skills. nine0003

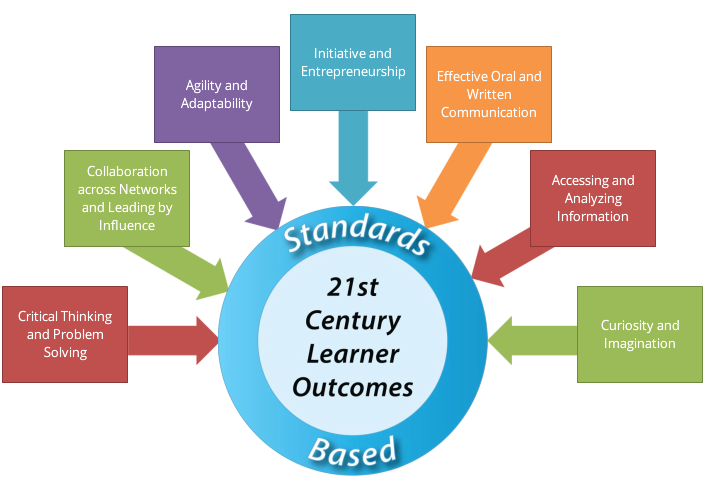

Social skills of preschoolers - the development of social skills in children

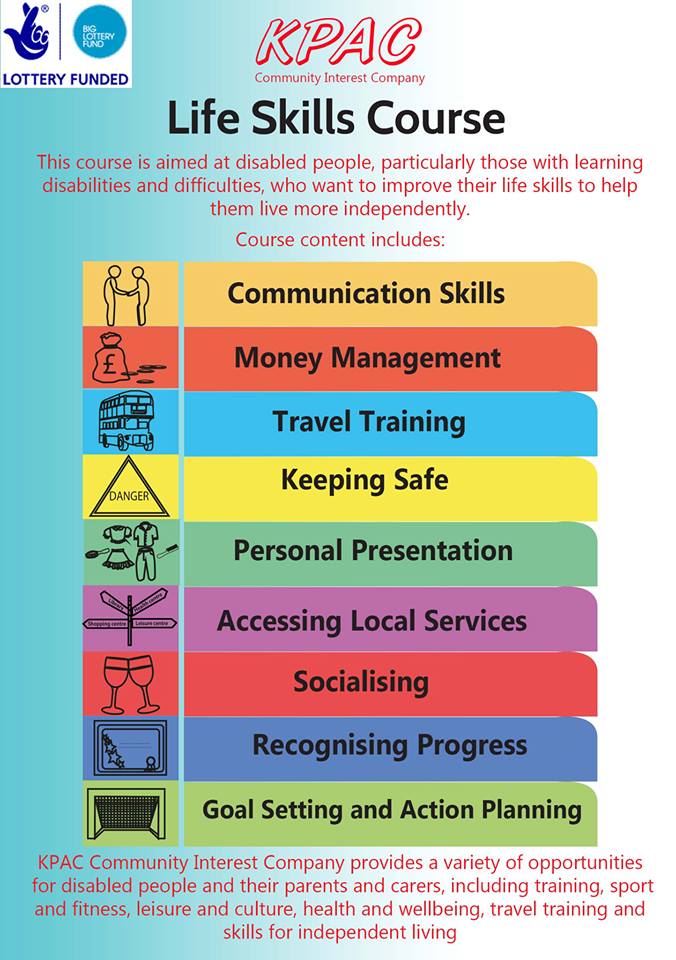

The development of social skills is a necessary point of education. A child with a high degree of socialization will quickly get used to kindergarten, school, any new team; in the future will easily find a job. Social skills have a positive effect on interpersonal relationships - friendship, the ability to cooperate.

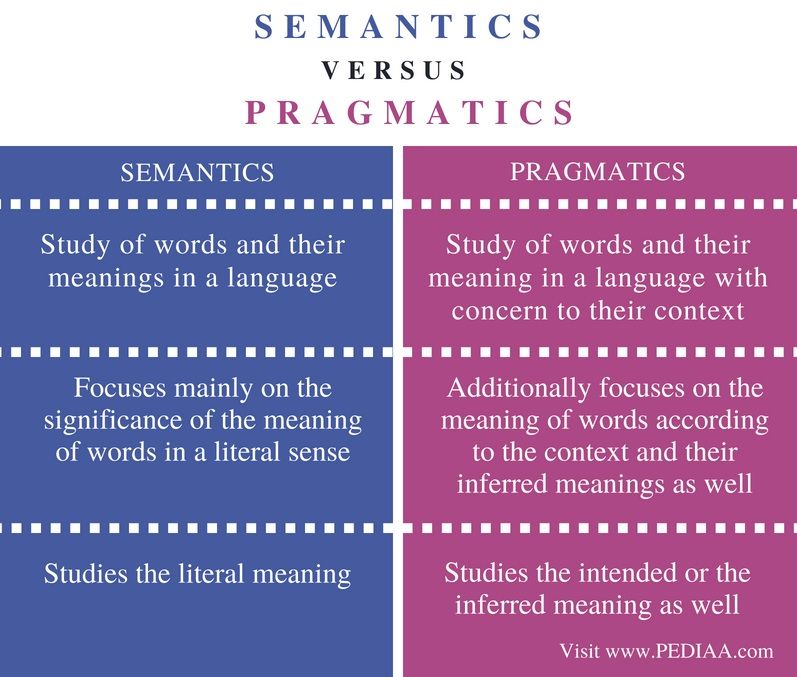

Let's figure out what social skills are.

What are social skills and why develop them? nine0061

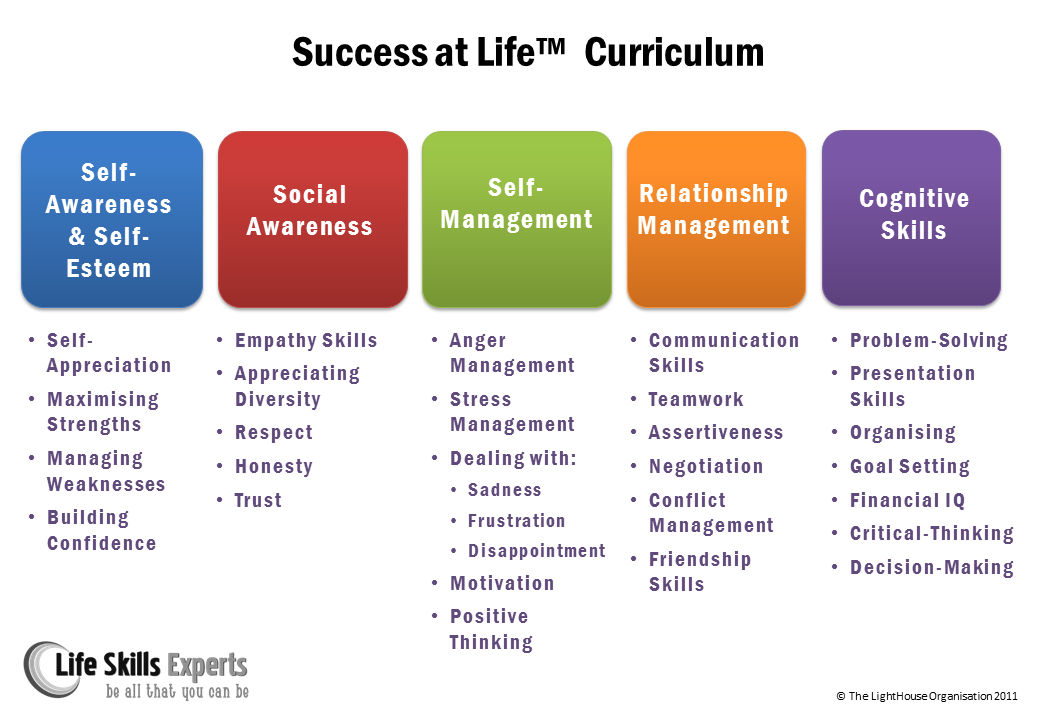

Social skills - a group of skills, abilities that are formed during the interaction of a person with society and affect the quality of communication with people.

Man is a social being: all our talents and aspirations are realized thanks to other members of the group. Others evaluate our actions, approve or condemn our behavior. It is difficult to reach the pinnacle of self-actualization alone.

That is why social skills are important. They should be developed from early childhood and honed throughout life. nine0003

Social skills are a reflection of the child's emotional intelligence, to which educators and teachers assign an important role in the process of personality development. Without this group of skills, a smart child will not be able to apply the acquired knowledge in practice: it is not enough to create something outstanding, you need to be able to correctly convey thoughts to the public.

Sometimes people mistakenly believe that social skills relate exclusively to the topic of communication, communication. In fact, skills include many multidirectional aspects: an adequate perception of one's own individuality, the ability to empathize, work in a team, etc.

In fact, skills include many multidirectional aspects: an adequate perception of one's own individuality, the ability to empathize, work in a team, etc.

Why do we need social skills?

- Regulate the area of interpersonal relationships: the child easily makes new friends, finds like-minded people.

- Minimize psychological stress: children with developed social skills quickly adapt, do not feel sad due to changes in external circumstances.

- They form an adequate self-esteem from childhood, which positively affects life achievements and development in adulthood.

- Social skills cannot be separated from building a successful career: the best specialists must not only understand the profession, but also have high emotional intelligence. nine0026

Development of social skills in a child

Social skills need to be developed from preschool age, but older children and even teenagers may well learn to interact with the world.

It is recommended to pay attention to areas of life that bring discomfort to the child, significantly complicate everyday life.

- Friends, interesting interlocutors: the kid does not know how to join the team, he prefers to sit in the corner while the others play.

- Verbal difficulties. The child does not understand the rules of conversation, is poorly versed in the formulas of etiquette (when you need to say hello, say goodbye, offer help). nine0026

- Problems with the non-verbal side of communication. Such a baby does not recognize the shades of emotions, it is difficult to understand how others relate to him. Cannot "read" faces and gestures.

- Does not know the measure in expressing a point of view: too passive or, conversely, aggressive.

- The child bullies classmates (participates in bullying) or is a victim.

In case of severe moral trauma, one should consult a psychologist: for example, school bullying is a complex problem that children are not able to cope with on their own. The involvement of parents and teachers is required. nine0003

The involvement of parents and teachers is required. nine0003

In other cases, family members may well be able to help the child develop social skills.

What are the general recommendations?

1. Be patient

Don't push your child to get things done. Let them take the initiative: for example, do not rush to help during school gatherings, let the baby work on the problem on his own. The same goes for lessons and other activities.

2. Support undertakings

Children's dreams seem trifling to adults, but the initiative turns into a habit over the years and helps to discover new projects, meet people, and experiment. nine0003

3. Criticize the right way

When making negative comments, remember the golden rule of criticism: analyze the work, highlighting both positive and negative aspects in a polite way. Commenting on the specific actions of the child, and not his personality or appearance - this will lead to problems with self-esteem.

4. The right to choose

It is important for children to feel that their voice is taken into account and influences the course of events. Invite your child to personally choose clothes, books, cartoons. Ask about ideas, plans: “We are going to have a rest together at the weekend. What are your suggestions? nine0003

5. Personal space

Make sure that the baby has a place where he can be alone, take a break from talking. Personal things should not be touched: rearrange without prior discussion, read correspondence with friends, check pockets, etc.

Children, noticing the respectful attitude of adults, quickly begin to pay in the same coin; the atmosphere in the family becomes warm and trusting.

What social skills should be developed in a child? nine0061

Let's dwell on the main qualities and skills, the development of which is worth paying attention to.

1. The ability to ask, accept and give help

Without the ability to ask for help, the child will deprive himself of valuable advice; the lack of the ability to accept help will lead to losses, and the inability to provide help will make the baby self-centered.

- Let the child help those in need: for example, a lagging classmate.

- Explain to your child that getting help from friends and teachers is not a shame. nine0026

- Show by personal example that mutual help enriches experience: tell how you exchange advice with colleagues, friends.

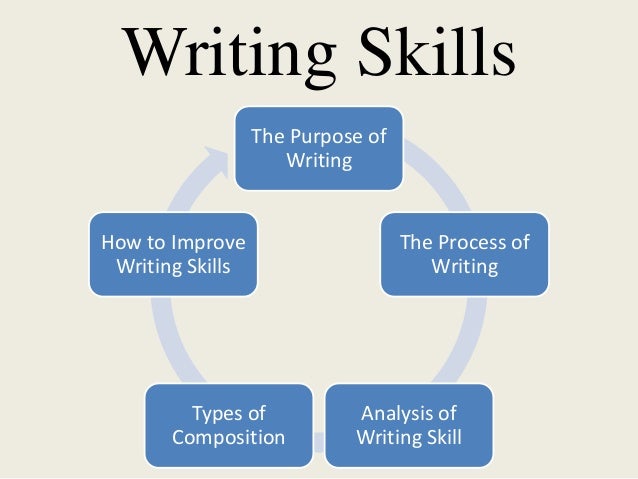

2. The ability to conduct a conversation and get the right information

Being a good conversationalist is difficult, but the skill is honed over time and brings a lot of benefits.

- Prompt your child for dialogue development options: for example, you can start a conversation with a relevant question, a request for help.

- Do not leave the child in the role of a silent listener: when discussing pressing issues at home, ask the opinion of the baby. nine0026

- Support children's public speaking: reports at school, performances, funny stories surrounded by loved ones will add confidence.

3. Empathy

Empathy is the ability to recognize the emotions of others, put yourself in the place of another person, empathize.

This ability will make the child humane, prudent. How can it be developed?

- Start by recognizing the child's feelings - it is useless to listen to people if the person does not feel personal experiences. Ask your baby: “How do you feel after a quarrel with friends?”, “Do you want to relax today?” nine0026

- After conflicts with classmates, ask your child how the children with whom the quarrel may feel now.

- While watching cartoons, reading books, pay your child's attention to the emotional state of the characters.

4. Ability to work in a team

Many children can easily cope with tasks alone, but this is not a reason to refuse to work in a team. It gives the opportunity to exchange ideas and experience, delegate tasks, achieve goals faster and more efficiently. nine0003

- If the child does not communicate with members of the team, try to introduce him to another social group: for example, the lack of communication with classmates can be compensated by a circle of interests, where the child will feel calmer.

- Make the family a friendly team in which the child has his own "duties": for example, do housework, remind parents of upcoming events. Any activity related to the well-being of other family members will do. nine0151

- Respect the child's personal boundaries: do not enter the nursery without warning, do not rummage through personal belongings and correspondence, if the life and safety of the baby is not at stake.

- If the child violates other people's boundaries (takes toys without permission, asks uncomfortable questions), talk about it in private.

- Talk about problems calmly, without raising your voice. Do not put pressure on the child with parental authority unnecessarily: the child is a separate person who has the right to an opinion.

- Do not judge people for views that differ from those of your family but do not affect your well-being. Show your child that the world is very different. nine0026

- You can demonstrate to children the basics of a civilized dispute, explain what arguments are, etc. It is advisable to teach this child in kindergarten.

5. Respect for personal boundaries

The absence of an obsessive desire to interfere in other people's lives is a valuable skill that helps to win people's sympathy.

6. Ability to overcome conflict situations

It is difficult to imagine our life without conflicts. The task of the child is to learn how to culturally enter into a discussion, defend his point of view, and not be led by the provocations of his interlocutors.

7. Self-confidence

Stable and adequate self-esteem is a quality that not all adults possess.

It is formed under the influence of many factors: relationships between parents, the role of the child in the family circle, the characteristics of the environment that surrounded the child in early childhood.

It is important that the child does not grow up to be either a narcissistic narcissist with fragile self-esteem, or an overly shy person.