Reading in phonics

Phonics Instruction | Reading Rockets

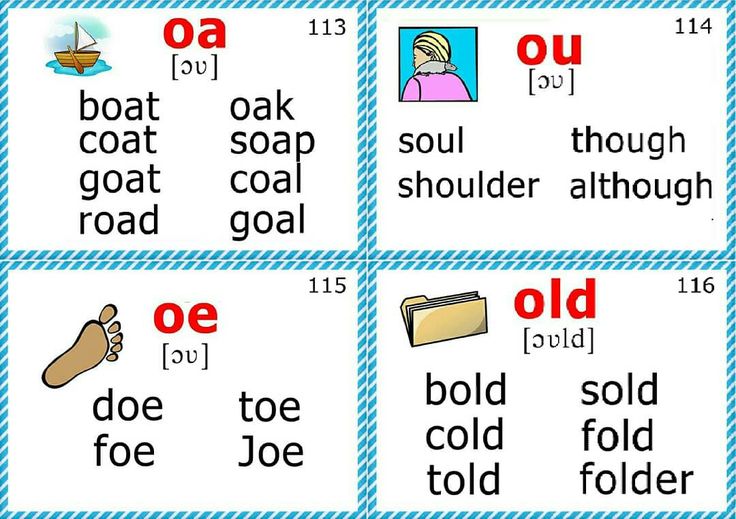

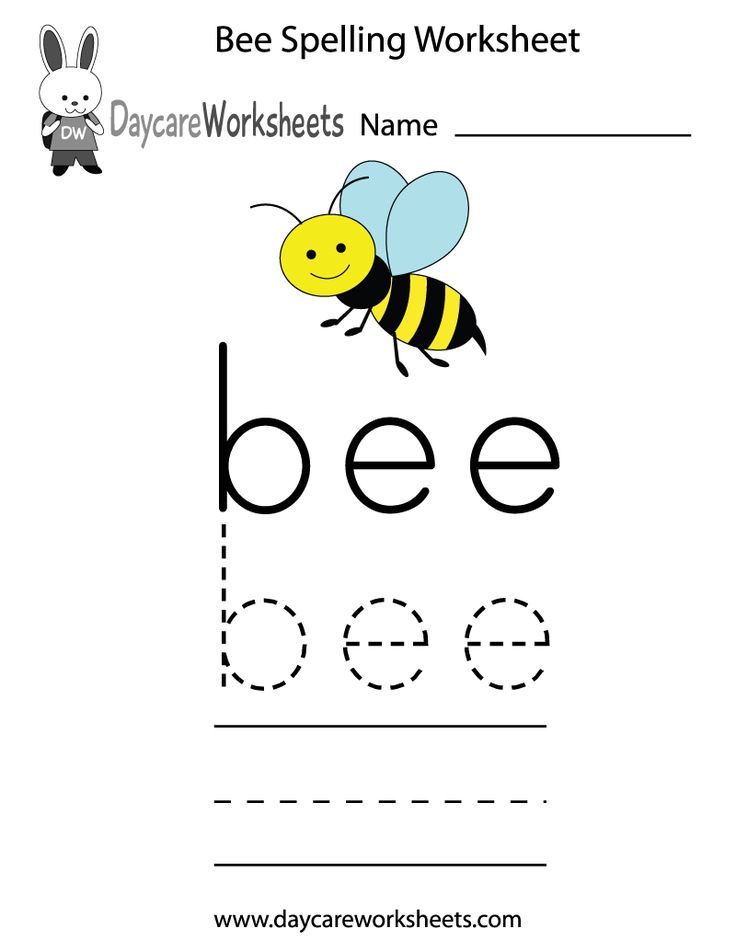

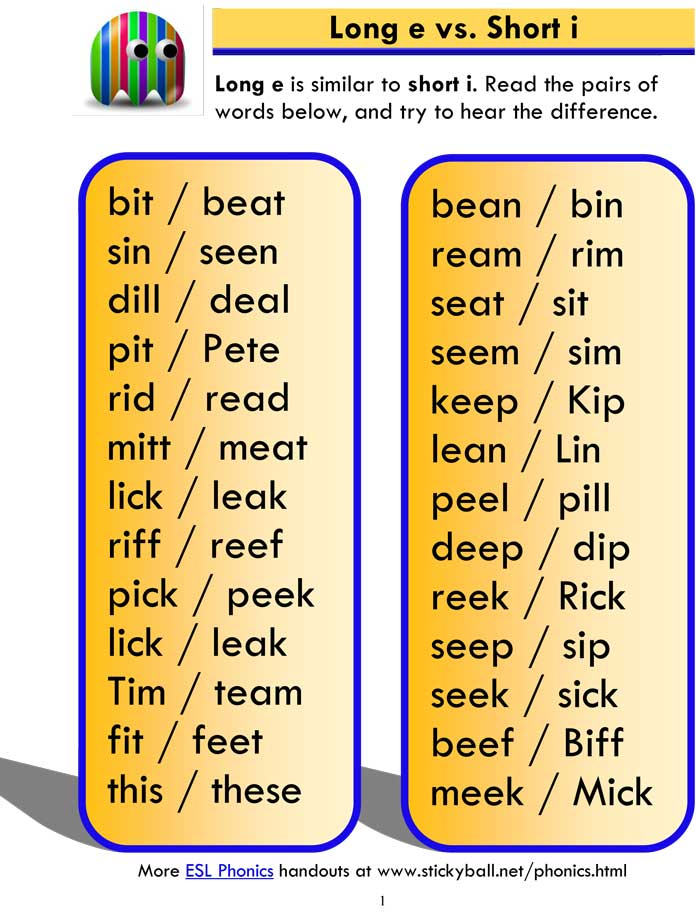

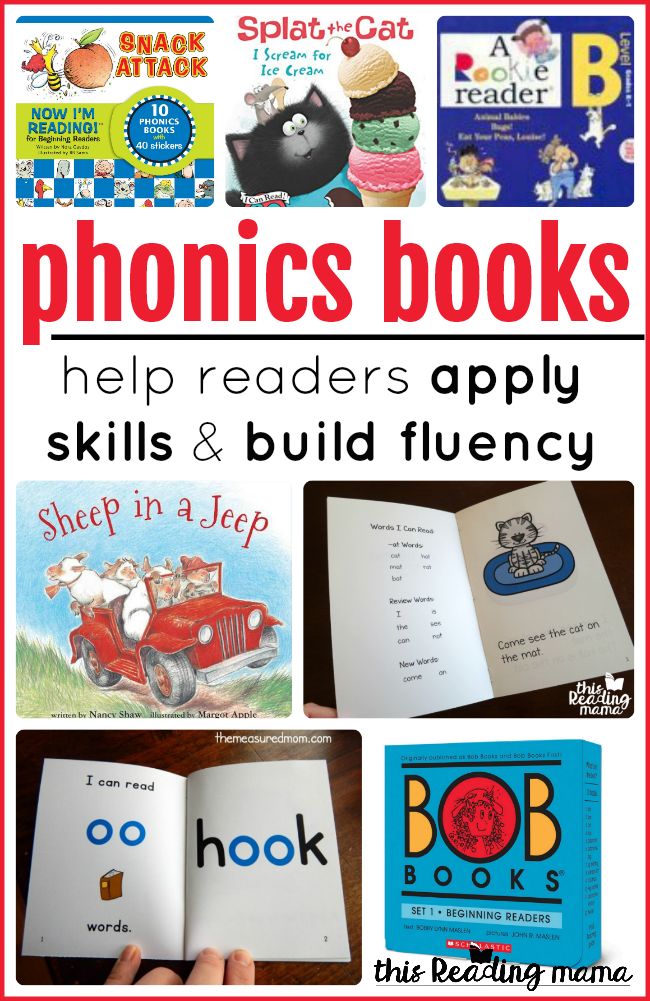

The primary focus of phonics instruction is to help beginning readers understand how letters are linked to sounds (phonemes) to form letter-sound correspondences and spelling patterns and to help them learn how to apply this knowledge in their reading.

Phonics instruction may be provided systematically or incidentally. The hallmark of a systematic phonics approach or program is that a sequential set of phonics elements is delineated and these elements are taught along a dimension of explicitness depending on the type of phonics method employed. Conversely, with incidental phonics instruction, the teacher does not follow a planned sequence of phonics elements to guide instruction but highlights particular elements opportunistically when they appear in text.

Types of phonics instructional methods and approaches

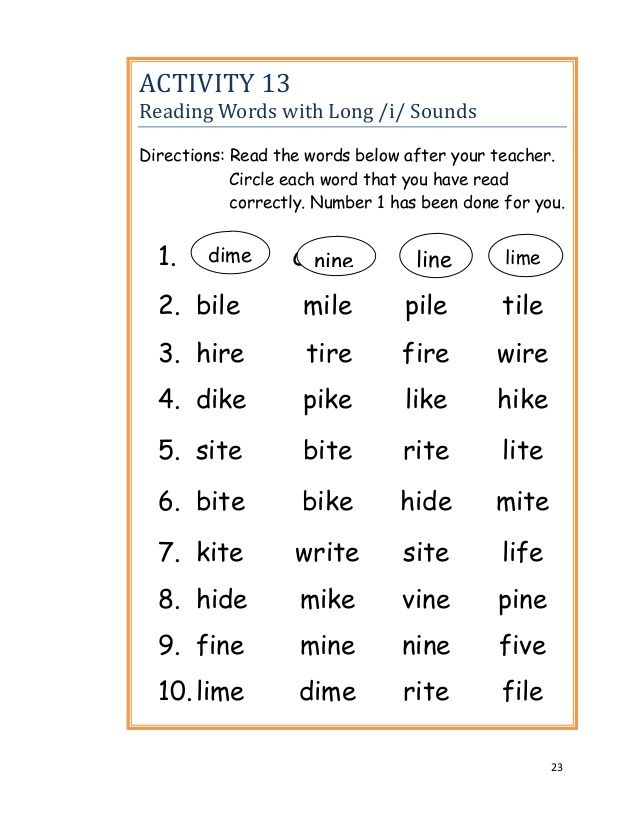

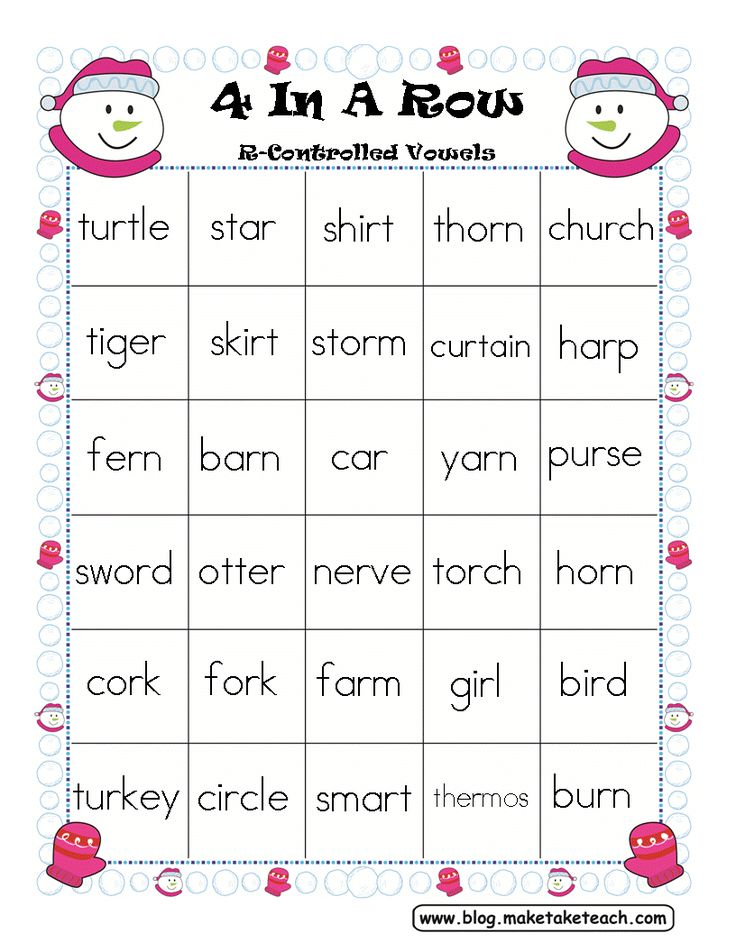

This table depicts several different types of phonics instructional approaches that vary according to the unit of analysis or how letter-sound combinations are represented to the student. For example, in synthetic phonics approaches, students are taught to link an individual letter or letter combination with its appropriate sound and then blend the sounds to form words. In analytic phonics, students are first taught whole word units followed by systematic instruction linking the specific letters in the word with their respective sounds.

Phonics instruction can also vary with respect to the explicitness by which the phonic elements are taught and practiced in the reading of text. For example, many synthetic phonics approaches use direct instruction in teaching phonics components and provide opportunities for applying these skills in decodable text formats characterized by a controlled vocabulary. On the other hand, embedded phonics approaches are typically less explicit and use decodable text for practice less frequently, although the phonics concepts to be learned can still be presented systematically.

- Analogy phonics

Teaching students unfamiliar words by analogy to known words (e.

g., recognizing that the rime segment of an unfamiliar word is identical to that of a familiar word, and then blending the known rime with the new word onset, such as reading

brick by recognizing that -ick is contained in the known word kick, or reading stump by analogy to jump).

g., recognizing that the rime segment of an unfamiliar word is identical to that of a familiar word, and then blending the known rime with the new word onset, such as reading

brick by recognizing that -ick is contained in the known word kick, or reading stump by analogy to jump). - Analytic phonics

Teaching students to analyze letter-sound relations in previously learned words to avoid pronouncing sounds in isolation.

- Embedded phonics

Teaching students phonics skills by embedding phonics instruction in text reading, a more implicit approach that relies to some extent on incidental learning.

- Phonics through spelling

Teaching students to segment words into phonemes and to select letters for those phonemes (i.e., teaching students to spell words phonemically).

- Synthetic phonics

Teaching students explicitly to convert letters into sounds (phonemes) and then blend the sounds to form recognizable words.

Findings and determinations

The meta-analysis revealed that systematic phonics instruction produces significant benefits for students in kindergarten through 6th grade and for children having difficulty learning to read. The ability to read and spell words was enhanced in kindergartners who received systematic beginning phonics instruction. First graders who were taught phonics systematically were better able to decode and spell, and they showed significant improvement in their ability to comprehend text. Older children receiving phonics instruction were better able to decode and spell words and to read text orally, but their comprehension of text was not significantly improved.

Systematic synthetic phonics instruction (see table for definition) had a positive and significant effect on disabled readers' reading skills. These children improved substantially in their ability to read words and showed significant, albeit small, gains in their ability to process text as a result of systematic synthetic phonics instruction. This type of phonics instruction benefits both students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students who are not disabled. Moreover, systematic synthetic phonics instruction was significantly more effective in improving low socioeconomic status (SES) children's alphabetic knowledge and word reading skills than instructional approaches that were less focused on these initial reading skills.

This type of phonics instruction benefits both students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students who are not disabled. Moreover, systematic synthetic phonics instruction was significantly more effective in improving low socioeconomic status (SES) children's alphabetic knowledge and word reading skills than instructional approaches that were less focused on these initial reading skills.

Across all grade levels, systematic phonics instruction improved the ability of good readers to spell. The impact was strongest for kindergartners and decreased in later grades. For poor readers, the impact of phonics instruction on spelling was small, perhaps reflecting the consistent finding that disabled readers have trouble learning to spell.

Although conventional wisdom has suggested that kindergarten students might not be ready for phonics instruction, this assumption was not supported by the data. The effects of systematic early phonics instruction were significant and substantial in kindergarten and the 1st grade, indicating that systematic phonics programs should be implemented at those age and grade levels.

The NRP analysis indicated that systematic phonics instruction is ready for implementation in the classroom. Findings of the Panel regarding the effectiveness of explicit, systematic phonics instruction were derived from studies conducted in many classrooms with typical classroom teachers and typical American or English-speaking students from a variety of backgrounds and socioeconomic levels.

Thus, the results of the analysis are indicative of what can be accomplished when explicit, systematic phonics programs are implemented in today's classrooms. Systematic phonics instruction has been used widely over a long period of time with positive results, and a variety of systematic phonics programs have proven effective with children of different ages, abilities, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Discussion

These facts and findings provide converging evidence that explicit, systematic phonics instruction is a valuable and essential part of a successful classroom reading program. However, there is a need to be cautious in giving a blanket endorsement of all kinds of phonics instruction.

However, there is a need to be cautious in giving a blanket endorsement of all kinds of phonics instruction.

It is important to recognize that the goals of phonics instruction are to provide children with key knowledge and skills and to ensure that they know how to apply that knowledge in their reading and writing. In other words, phonics teaching is a means to an end.

To be able to make use of letter-sound information, children need phonemic awareness. That is, they need to be able to blend sounds together to decode words, and they need to break spoken words into their constituent sounds to write words. Programs that focus too much on the teaching of letter-sound relations and not enough on putting them to use are unlikely to be very effective.

In implementing systematic phonics instruction, educators must keep the end in mind and ensure that children understand the purpose of learning letter sounds and that they are able to apply these skills accurately and fluently in their daily reading and writing activities.

Of additional concern is the often-heard call for "intensive, systematic" phonics instruction. Usually the term "intensive" is not defined. How much is required to be considered intensive?

In addition, it is not clear how many months or years a phonics program should continue. If phonics has been systematically taught in kindergarten and 1st grade, should it continue to be emphasized in 2nd grade and beyond? How long should single instruction sessions last? How much ground should be covered in a program? Specifically, how many letter-sound relations should be taught, and how many different ways of using these relations to read and write words should be practiced for the benefits of phonics to be maximized? These questions remain for future research.

Another important area is the role of the teacher. Some phonics programs showing large effect sizes require teachers to follow a set of specific instructions provided by the publisher; while this may standardize the instructional sequence, it also may reduce teacher interest and motivation.

Thus, one concern is how to maintain consistency of instruction while still encouraging the unique contributions of teachers. Other programs require a sophisticated knowledge of spelling, structural linguistics, or word etymology. In view of the evidence showing the effectiveness of systematic phonics instruction, it is important to ensure that the issue of how best to prepare teachers to carry out this teaching effectively and creatively is given high priority.

Knowing that all phonics programs are not the same brings with it the implication that teachers must themselves be educated about how to evaluate different programs to determine which ones are based on strong evidence and how they can most effectively use these programs in their own classrooms. It is therefore important that teachers be provided with evidence-based preservice training and ongoing inservice training to select (or develop) and implement the most appropriate phonics instruction effectively.

A common question with any instructional program is whether "one size fits all. " Teachers may be able to use a particular program in the classroom but may find that it suits some students better than others. At all grade levels, but particularly in kindergarten and the early grades, children are known to vary greatly in the skills they bring to school. Some children will already know letter-sound correspondences, and some will even be able to decode words, while others will have little or no letter knowledge.

" Teachers may be able to use a particular program in the classroom but may find that it suits some students better than others. At all grade levels, but particularly in kindergarten and the early grades, children are known to vary greatly in the skills they bring to school. Some children will already know letter-sound correspondences, and some will even be able to decode words, while others will have little or no letter knowledge.

Teachers should be able to assess the needs of the individual students and tailor instruction to meet specific needs. However, it is more common for phonics programs to present a fixed sequence of lessons scheduled from the beginning to the end of the school year. In light of this, teachers need to be flexible in their phonics instruction in order to adapt it to individual student needs.

Children who have already developed phonics skills and can apply them appropriately in the reading process do not require the same level and intensity of phonics instruction provided to children at the initial phases of reading acquisition. Thus, it will also be critical to determine objectively the ways in which systematic phonics instruction can be optimally incorporated and integrated in complete and balanced programs of reading instruction. Part of this effort should be directed at preservice and inservice education to provide teachers with decision-making frameworks to guide their selection, integration, and implementation of phonics instruction within a complete reading program.

Thus, it will also be critical to determine objectively the ways in which systematic phonics instruction can be optimally incorporated and integrated in complete and balanced programs of reading instruction. Part of this effort should be directed at preservice and inservice education to provide teachers with decision-making frameworks to guide their selection, integration, and implementation of phonics instruction within a complete reading program.

Teachers must understand that systematic phonics instruction is only one component – albeit a necessary component – of a total reading program; systematic phonics instruction should be integrated with other reading instruction in phonemic awareness, fluency, and comprehension strategies to create a complete reading program.

While most teachers and educational decision-makers recognize this, there may be a tendency in some classrooms, particularly in 1st grade, to allow phonics to become the dominant component, not only in the time devoted to it, but also in the significance attached. It is important not to judge children's reading competence solely on the basis of their phonics skills and not to devalue their interest in books because they cannot decode with complete accuracy. It is also critical for teachers to understand that systematic phonics instruction can be provided in an entertaining, vibrant, and creative manner.

It is important not to judge children's reading competence solely on the basis of their phonics skills and not to devalue their interest in books because they cannot decode with complete accuracy. It is also critical for teachers to understand that systematic phonics instruction can be provided in an entertaining, vibrant, and creative manner.

Systematic phonics instruction is designed to increase accuracy in decoding and word recognition skills, which in turn facilitate comprehension. However, it is again important to note that fluent and automatic application of phonics skills to text is another critical skill that must be taught and learned to maximize oral reading and reading comprehension. This issue again underscores the need for teachers to understand that while phonics skills are necessary in order to learn to read, they are not sufficient in their own right. Phonics skills must be integrated with the development of phonemic awareness, fluency, and text reading comprehension skills.

Explaining Phonics Instruction | Reading Rockets

By: International Literacy Association

This ILA brief explains the basics of phonics for parents, offering guidance on phonics for emerging readers, phonological awareness, word study, approaches to teaching phonics, and teaching English learners.

This 2018 brief explains the what, the when and the how of phonics instruction to parents, offering guidance on phonics for emerging readers, phonological awareness, word study, approaches to teaching phonics, and teaching English learners.

Key takeaways:

- Students should have acquired phonological awareness, concepts of print, concepts of word of text and alphabetic principles before beginning to learn phonics.

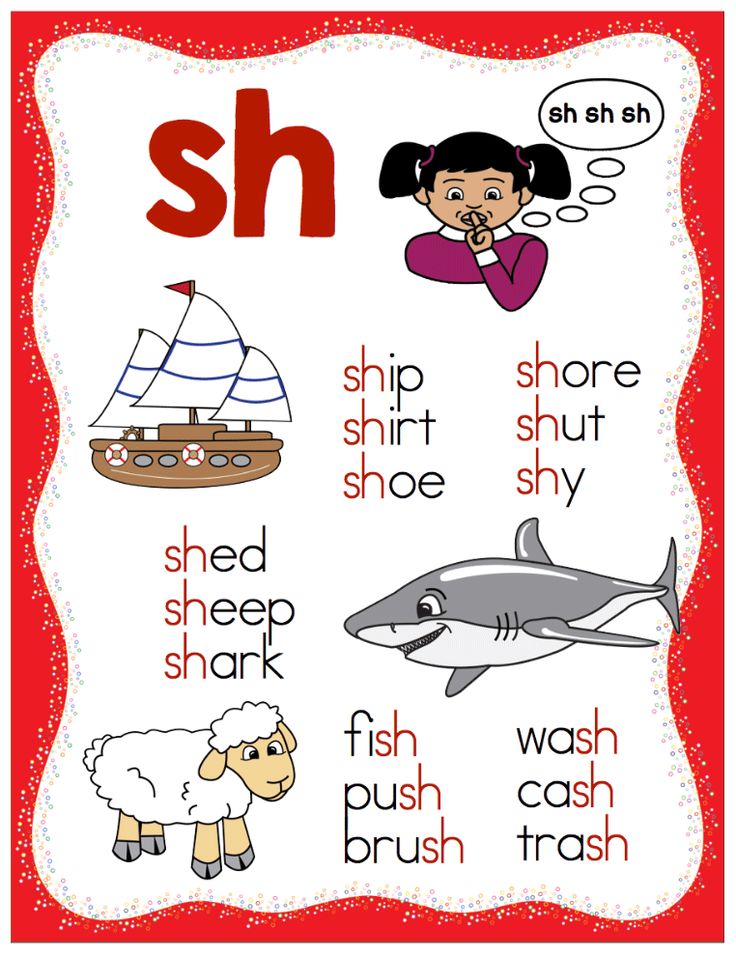

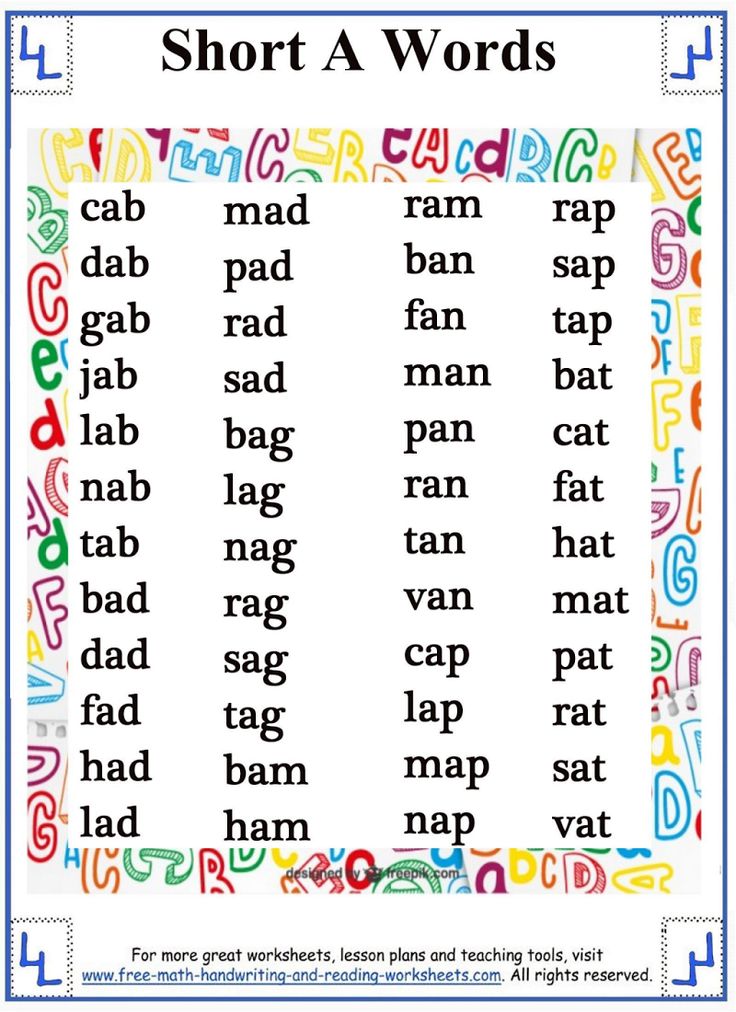

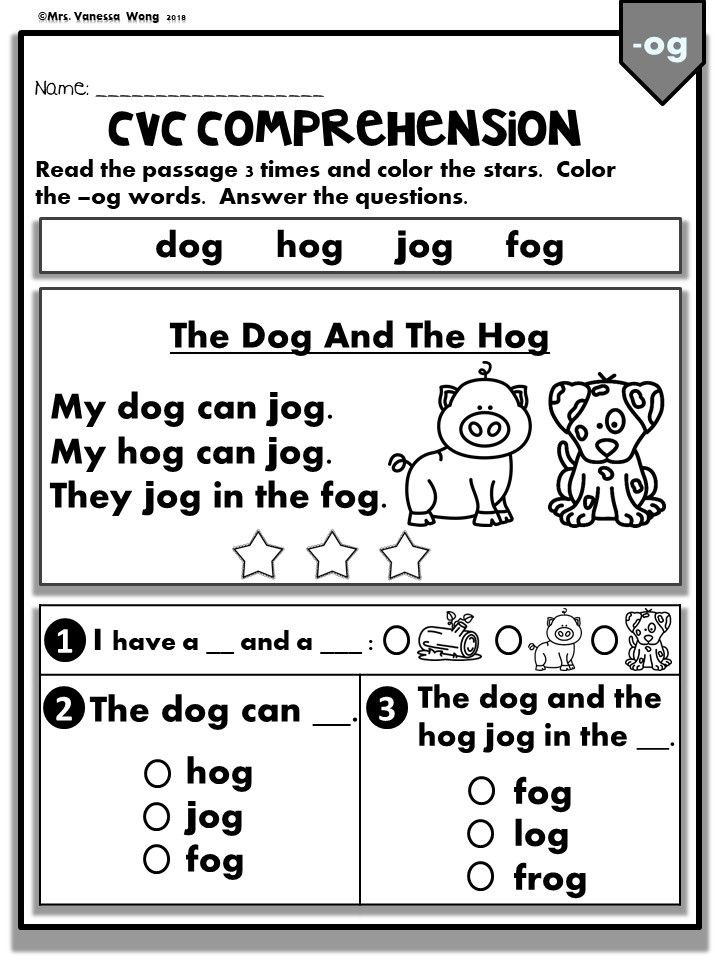

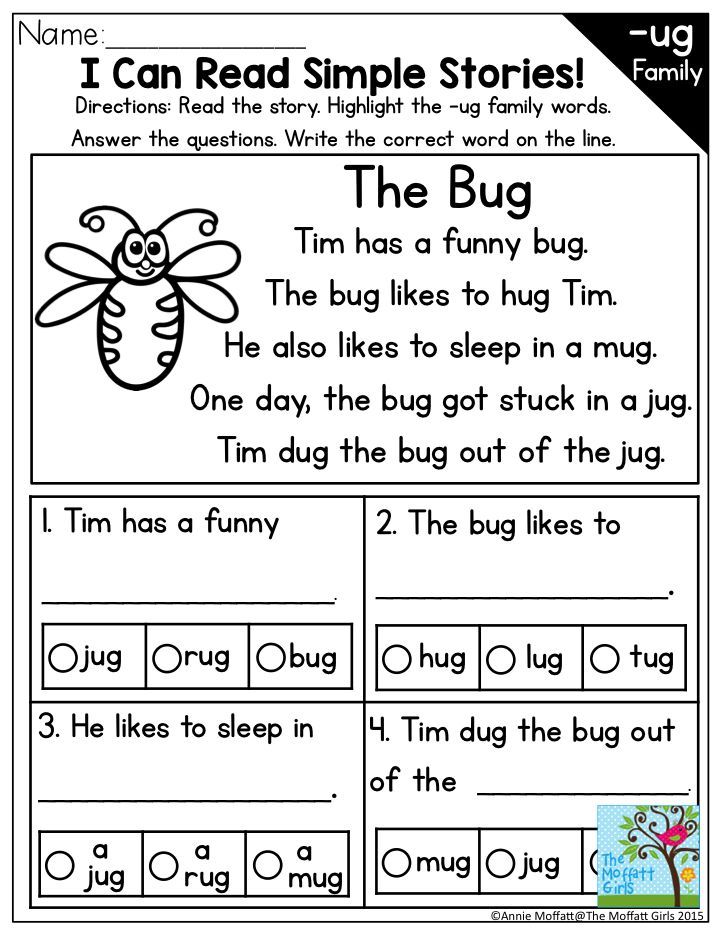

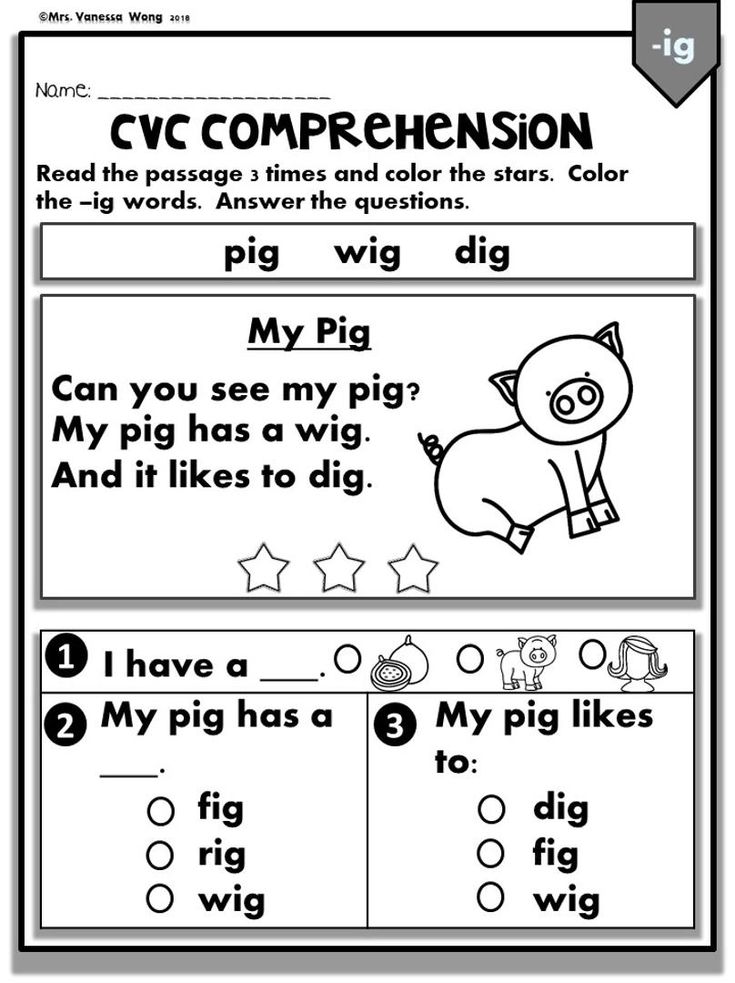

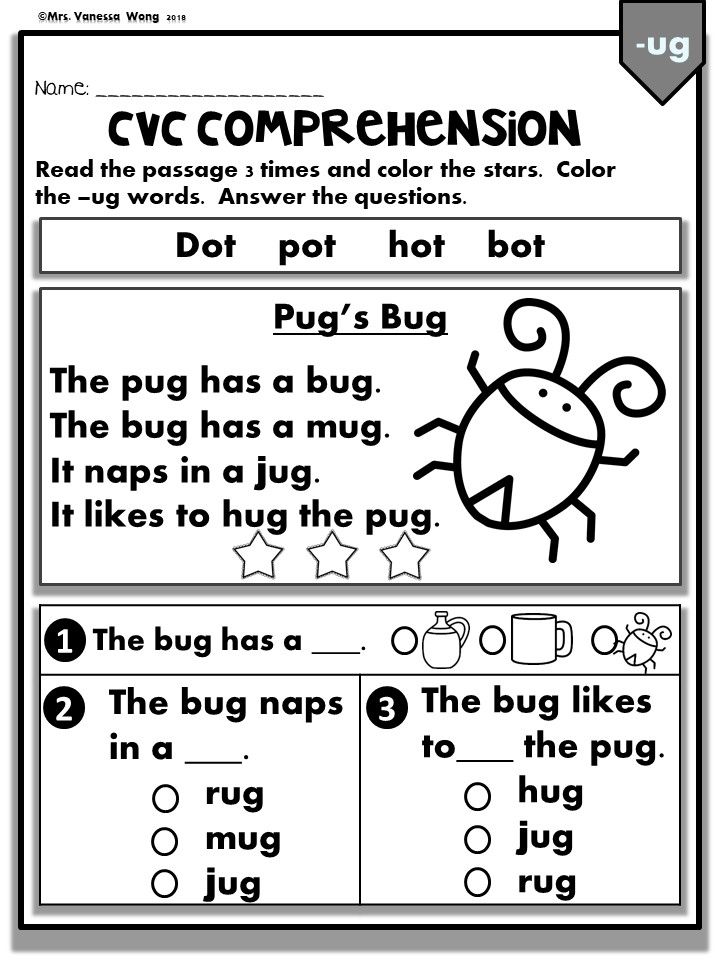

- Most phonics programs incorporate both analytic and synthetic activities. In analytic instruction, students compare words to identify patterns and apply this knowledge to new words (e.g., ran/can), or they examine word families to make analogies between segments of words (e.

g., onset and rime, r-an/c-an/f-an/m-an/p-an). In synthetic phonics, students blend individual letter sounds together to form words (e.g., c-a-t/cat).

g., onset and rime, r-an/c-an/f-an/m-an/p-an). In synthetic phonics, students blend individual letter sounds together to form words (e.g., c-a-t/cat). - Word study is an approach to teach the alphabetic layer (basic letter–sound correspondences) and pattern layer (consonant–vowel patterns) of the writing system by including spelling instruction that is differentiated by students’ development.

- Phonics instruction depends on the characteristics of a specific language; students who learn to read in multiple languages apply phonics that fit the respective letter–sound, pattern and meaning layers.

- Emergent bilingual readers and writers use their knowledge of one language to learn other languages.

See the full brief, Explaining Phonics Instruction: An Educator’s Guide.

International Literacy Association (2018)

Reprints

You are welcome to print copies for non-commercial use, or a limited number for educational purposes, as long as credit is given to Reading Rockets and the author(s). For commercial use, please contact the author or publisher listed.

For commercial use, please contact the author or publisher listed.

Related Topics

Early Literacy Development

Phonics and Decoding

Spelling and Word Study

New and Popular

100 Children’s Authors and Illustrators Everyone Should Know

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

7 Great Ways to Encourage Your Child's Writing

All Kinds of Readers: A Guide to Creating Inclusive Literacy Celebrations for Kids with Learning and Attention Issues

Screening, Diagnosing, and Progress Monitoring for Fluency: The Details

Phonemic Activities for the Preschool or Elementary Classroom

Our Literacy Blogs

Shared Reading in the Structured Literacy Era

Kids and educational media

Meet Ali Kamanda and Jorge Redmond, authors of Black Boy, Black Boy: Celebrating the Power of You

Get Widget |

Subscribe

Method of analytical phonetics in teaching reading

- Come on, put down your name.

Filipok said:

- Hwe-i-hvi, le-i-li, pe-ok-pok.

Leo Tolstoy “Philippok”

Having learned the alphabet does not mean that he has begun to read fluently. Children have to memorize what sounds letters express in various combinations. Given the number of exceptions, the process of learning to read is being delayed. To know how to teach, let's look at the main methods for developing reading skills and the benefits of analytical phonetics.

In England in the nineties of the twentieth century, along with native English schoolchildren, children of parents who had moved to live in the British Isles from other countries began to appear in schools. Teachers soon noticed the fact that immigrant students were better at reading non-native English than native English. Teachers conducted an experiment by introducing the method of inductive phonetics into the teaching of reading in their native language. The result was impressive! Since then, a huge number of studies have been carried out that have proven the effectiveness of this method of teaching reading, many teachers in England began to resort to the method of inductive phonetics. Now it is impossible to imagine the educational process in English-speaking countries without this technique.

Now it is impossible to imagine the educational process in English-speaking countries without this technique.

There are two methods of teaching reading in the methodology: deductive and inductive phonetics . The difference between deductive (analytic phonics, analytical phonics) and inductive phonetics (synthetic phonics) is that learning to read is based on the process of transition from word to sound, and not vice versa. Also in deductive phonetics there is no mixing of sounds into words, as inductive. Using the method of analytical phonics, it is far from always possible for a teacher to be sure that students will be able to read similar words with an approximately similar set of letters or sounds. As a rule, students just memorize the reading of the learned words and intuitively analyze other words while reading. Inductive phonetics is a kind of speed reading technique. It is used in schools in England at the initial stage of teaching children.

The use of inductive phonetics does not preclude the use of deductive phonetics. In English, there are words that cannot be divided into sounds, and students need to memorize them using visual memory - these are sight words. These include:

In English, there are words that cannot be divided into sounds, and students need to memorize them using visual memory - these are sight words. These include:

- frequently used words;

- words that are not read according to the general phonetic rules (one, two).

Principles of the method of analytical phonetics

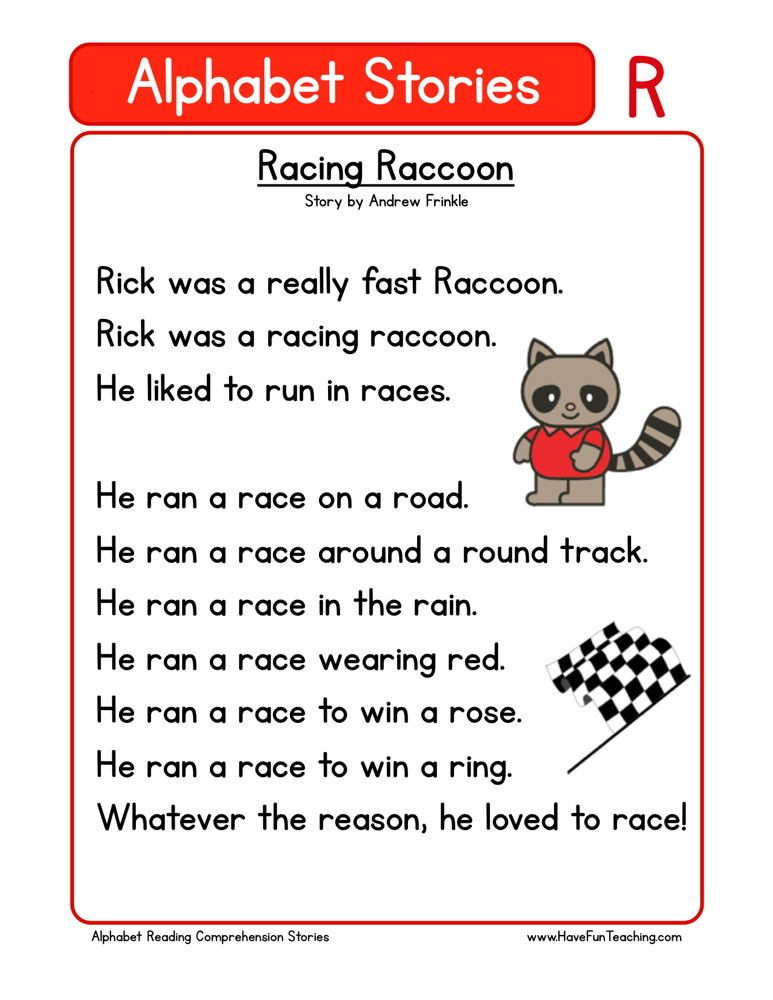

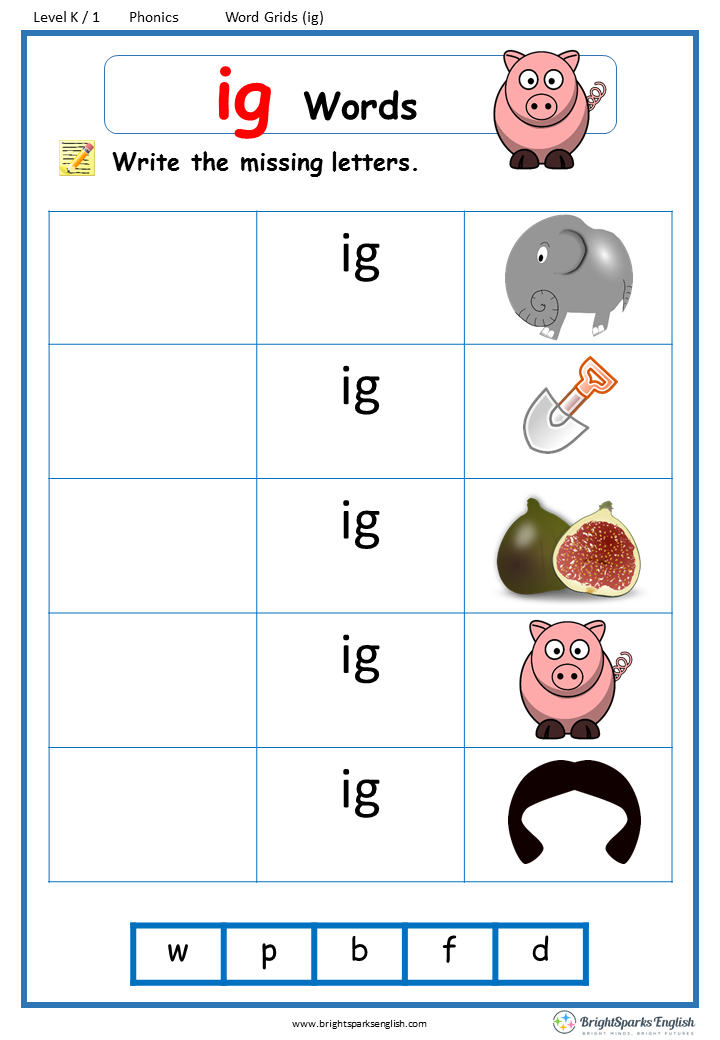

- Children try to guess how a word is read after reading a group of similar words.

- The emphasis is on the first sound of the word.

- Slow learning - one sound per week is introduced.

- No logical order for introducing new sounds.

- Exceptions to the rules are dealt with, although not all, but only the main ones.

- Parsing the correct spelling of a word is often skipped.

- Illustrations are used for hints, the child guesses what word is in front of him and “reads” it from the picture

It should be noted that the methodology is suitable for Russian students who are just starting to learn English at school. In EMC for children, it is proposed to combine both approaches - to enter letters and sounds before reading them in words, but also to guess many rules based on reading groups of words with the same letter combinations. Children are different, use the methods of analytical and synthetic phonetics so that everyone can achieve excellent results.

In EMC for children, it is proposed to combine both approaches - to enter letters and sounds before reading them in words, but also to guess many rules based on reading groups of words with the same letter combinations. Children are different, use the methods of analytical and synthetic phonetics so that everyone can achieve excellent results.

Earn with Skyeng

Skyteach

An open community for English teachers. We bring together people who strive to make learning relevant, exciting, effective

Add to bookmarks

Share link

Phonetics and rules for reading English

Phonetics and rules for reading English  Tel. (972)54-5466290 Tel. (972)54-5466290 | |

| main | new | tests | dictionaries | golden rules | methodology | all languages alphabetically | with or without a teacher | author | required | advertise |

Ukrainian, Polish, Czech, Serbian, Bulgarian and other Slavic languages

German, Yiddish, Dutch, Danish, Icelandic, Swedish and other Germanic languages

French, Spanish, Italian and other Romance languages

Latin and other Italian languages

Indo-Iranian languages

Baltic languages

Irish

Other languages of the Indo-European family

Finnish, Hungarian and other languages of the Uralic family

Georgian and other Caucasian languages

Hebrew, Arabic and other Semitic-Hamitic languages

Turkish, Mongolian and other languages of the Altaic family

Sino-Tibetan languages

Japanese, Ryukyu and Korean languages

Other natural languages

Hebrew languages of different families

Artificial languages

English phonetics presents a serious difficulty at the initial stage of language learning. At first sight, the rules of reading in English almost do not appear, and in relation to the most important words, it seems that they do not exist at all! At first sight, the rules of reading in English almost do not appear, and in relation to the most important words, it seems that they do not exist at all! Discrepancies between writing and pronunciation are explained by the conservatism of English orthography. Today English words are spelled as they were read 500-600 years ago. Therefore, at the first stage (until experience has been gained and intuition developed) the pronunciation of some words has to be memorized. Worse: words, spelled the same can be pronounced differently. For example, read [ri:d] 'read', but read [red] 'read'; reading ['ri:dıŋ] 'reading', but Reading ['redıŋ] 'Reading (city name)'; live [lıv] 'to live', but live [laıv] 'alive'; wind [wınd] 'wind', but wind [waınd] 'to wind'. To memorize such words, I recommend make phrases like I read [red] a red book about Reading 'I read the red book on Reading'. The word bow is pronounced [bau] when it means 'to bend, to bow'. However, when it means 'bow', it sounds [bou].  To remember this, let's make a phrase: I refuse to bow to a clown 'I refuse bow to the clown', where the words bow and clown contain the same diphthong [au]. To remember this, let's make a phrase: I refuse to bow to a clown 'I refuse bow to the clown', where the words bow and clown contain the same diphthong [au]. The word row can also be pronounced in two ways. Pronounced [rou], it means 'row' and for it remembering in this meaning the phrase We have rows of rose bushes is useful in the garden 'We have rows of rose bushes in the garden', in which the words rows and rose sound the same. The word row can also sound like [rau], then it means 'quarrel'. In the phrase There was a terrible row in the house 'In this house there was terrible quarrel' the words row and house are characterized by one and the same diphthong. There are 46 sounds in modern English, and the Latin alphabet has only 26 letters. The quantitative difference is especially great in relation to vowels. To convey 22 vowel sounds, English uses only 6 letters, one of which ( y ) sometimes behaves like a consonant. So, for one vowel, there are approximately 4 vowel sound.  Loading... Advertising: English in the Kalininsky district - effective courses at an affordable price. And yet - THE RULES OF READING IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARE PRESENT! To understand them (especially in terms of pronunciation of vowels), you will have to discard the usual many reading principle sound -> letter and master a new one, in which the word is divided into syllables. At the same time depending on the type of syllable, the same vowel takes on different sound values. |