Reading music kids

🎼 FREE Learn How to Read Music Printables for Kids

If you are looking for some handy, free music printables for teaching children how to read music, you will love these music worksheets and music activities for kids. These pages will help kindergarten, first grade, 2nd grade, 3rd grade, and 4th graders learn to read music. Simply print pdf file with reading music notes projects and you are ready to play and learn!

Reading Music for Kids

Teaching children to read music does not have to be with the purpose of learning to play an instrument or sing long term. This can be an activity that children do for a little, and never pick up fully. On the other hand, though, teaching children to read music is the first step of them learning to play an instrument. These Reading Music Printables are a great way to introduce children to this concept. Use this

reading musical notes with kindergartners, grade 1, grade 2, grade 3, and grade 4 students.

How to read music for kids

Start by scrolling to the bottom of the post, under the terms of use, and click on the text link that says >> _____ <<. The pdf file will open in a new window for you to save the freebie and print the template.

Learning to read music worksheets

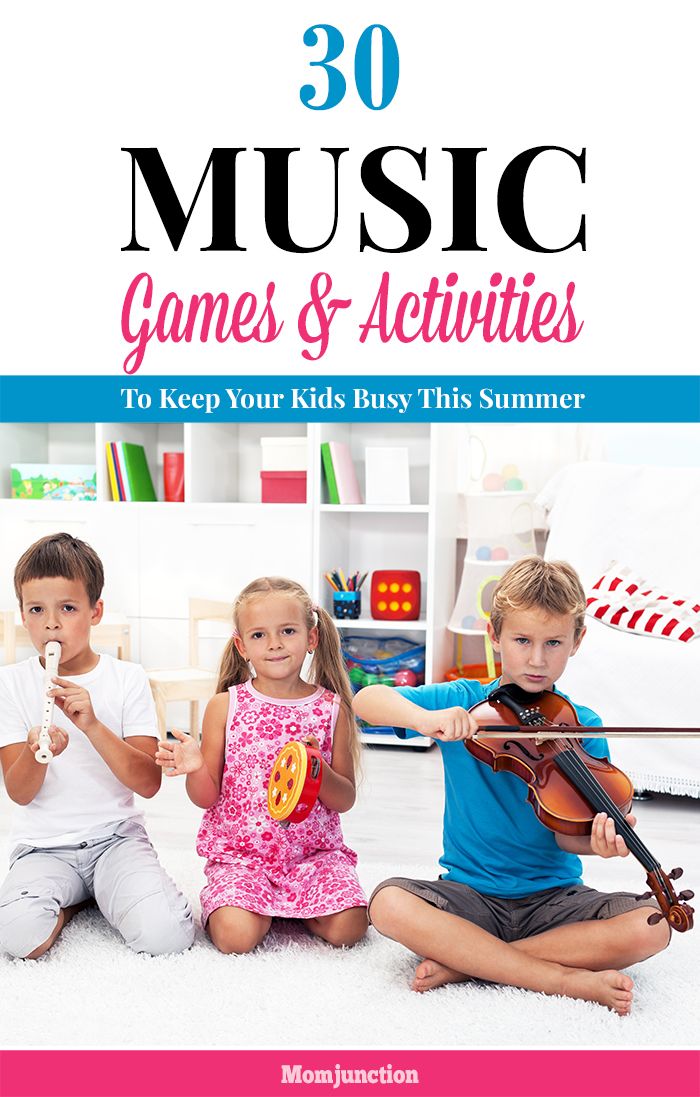

There are fantastic benefits to reading music that go beyond the music. While learning to play an instrument and being involved in music is extremely beneficial for children, reading music alone is too.

- Brain Growth: Studies show that exposure to music can help brain function increase. Whether your child is singing, playing an instrument or strictly listening to music, it can be beneficial in stimulating the brain and creating new formations.

- Language Skills: Children who are exposed to music at a young age typically have stronger speech development and can even learn to read earlier than those children who are not exposed to music.

- Math: Music can help children with math skills by listening to the beat, being introduced to fractions and of course numbers. Music also helps children strengthen spatial intelligence and ability to form mental pictures of objects, which is crucial for math development.

- Coordination: Playing an instrument or dancing to the beat can help children with their gross motor skills. Music helps connect the mind to the body.

- Confidence: Playing an instrument can help a child with their self confidence by giving them great opportunities for achievement.

How to read music printable

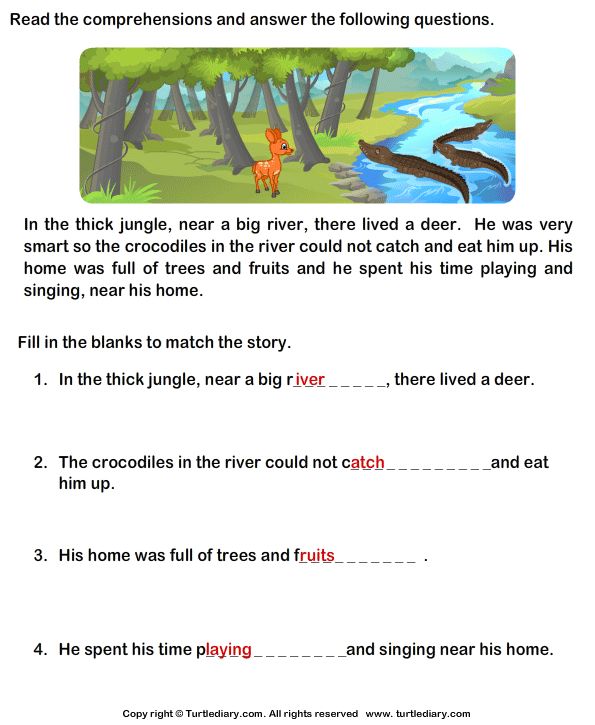

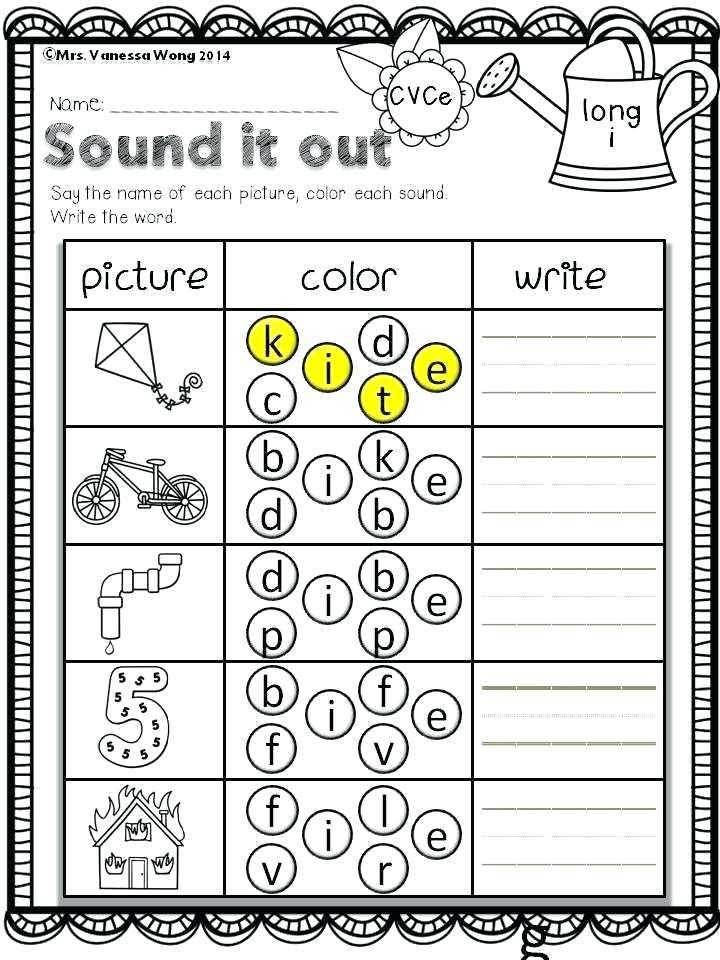

These music printables are perfect for introducing reading music to children. We have included pages that can be used:

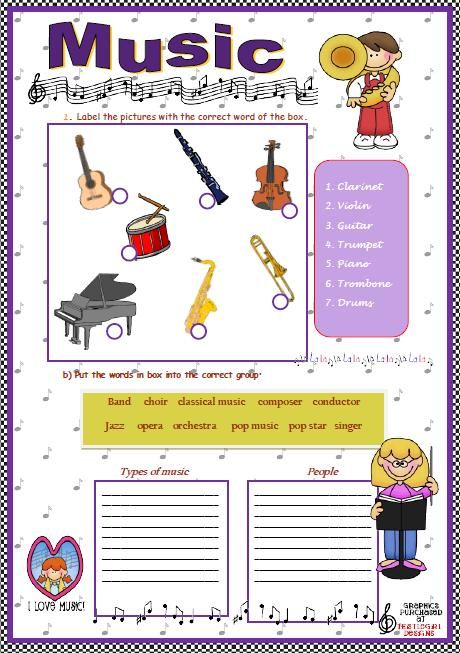

- Posters to hang on the wall or leave on a table for reference – This includes where the various notes fall on a music staff as well as a chart of the different symbols that are associated with music.

- Two interactive activities for learning to read music

Learn to read music worksheets

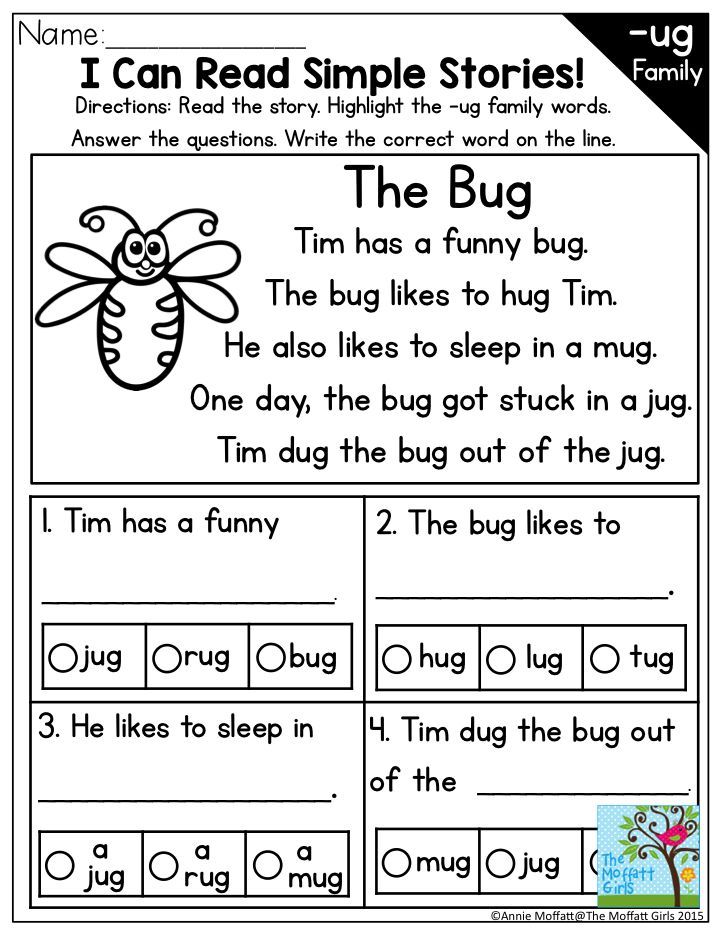

The first is a music symbols matching game. This can be played in two different ways. If you look at the bottom of the page, there are the symbols inside boxes. These can be cut out and pasted next to the word that matches. This helps children learn and identify the symbols that music entails.

Teaching kids to read music

The second is to write the correct notes on the music staff. The notes are just like whole notes, with the circle empty on the inside. This leaves room for children to fill in the circle of what the notes are.

Exposure to music is calming, helps children develop and it is fun! These printables are just the start to helping your children learn to read music and enjoy the world of music.

Music for Kids

Looking for more fun and free printables and resources to teach kids music? Try these:

- FREE Music Theory Worksheets for kids to learn all about MUSIC

- Printable piano flashcards

- Paper Plate Tambourine Musical Instrument Craft

- Super cute Piano practice sheets

- Musical Instruments Worksheets for kids to learn math and literacy skills while learning about instruments for kids

- Free Printable Music Flash cards

- Introduction to Music Theory for Kids printable book to read, color, and learn

- Free Music Notes Chart

- FUN Homemade Musical Instruments for kids

- Nature Noisemaker Music Activities for Preschoolers

- Create Music Instruments for Kids with these printable playdough mats!

Learn to read music pdf

By using resources from my site you agree to the following:

- This is for personal or personal classroom use

- This may NOT be sold, hosted, reproduced, or stored on any other site (including blog, Facebook, Dropbox, etc.

)

) - All materials provided are copyright protected. Please see Terms of Use.

- Graphics Purchased and used with permission from Dancing Crayon Designs and Rebecca B. Designs

- I offer free printables to bless my readers AND to provide for my family. Your frequent visits to my blog & support purchasing through affiliates links and ads keep the lights on so to speak. Thanks you!

>> Music Worksheets <<

Deanna

Deanna Hershberger is a work at home mom, coffee obsessed, a diy addict and a Netflix binger. She spends her days playing and making with her daughter and enjoys quiet nights at home with her husband. She shares all of this on her blog Play Dough & Popsicles.

How to Teach Kids to Read Music Notes

By Arctic Meta,

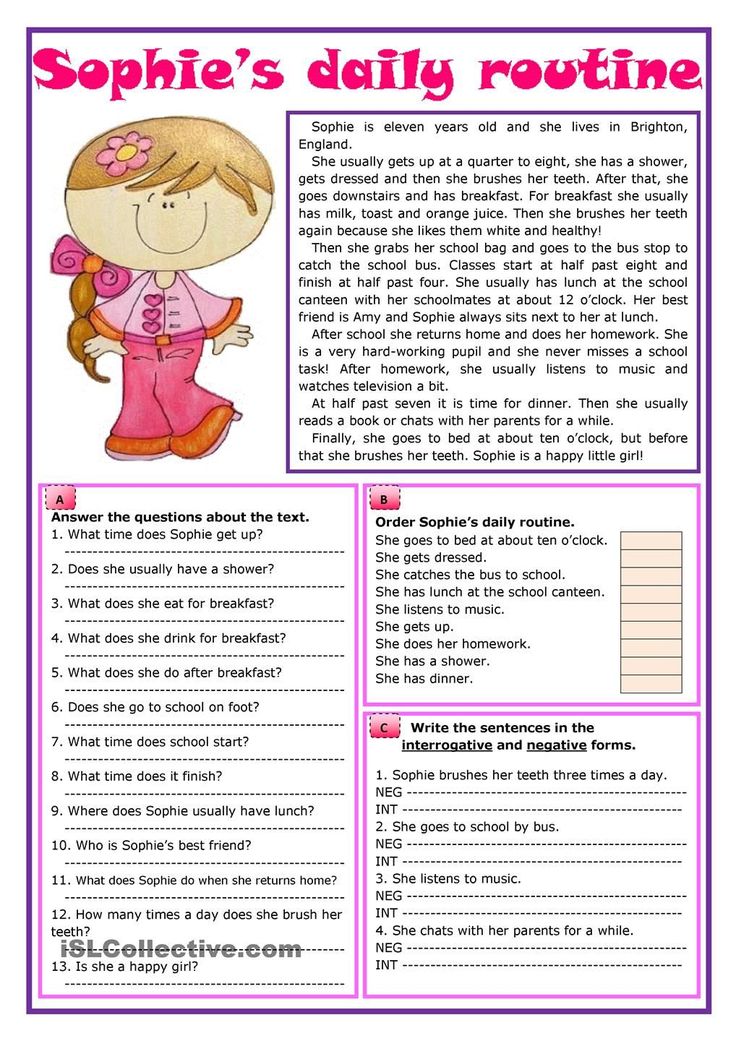

Learning to read music is an impressive and useful skill to have, even if you never plan on being a professional musician. The ability to take written sheet music and know how to transform it into something that can be played, enjoyed and listened to is something most would love to have.

Although it is possible to play instruments without ever undertaking a formal musical education, learning to read and accurately play music notes helps to build a strong foundation that gives a music student much more freedom and control over their abilities.

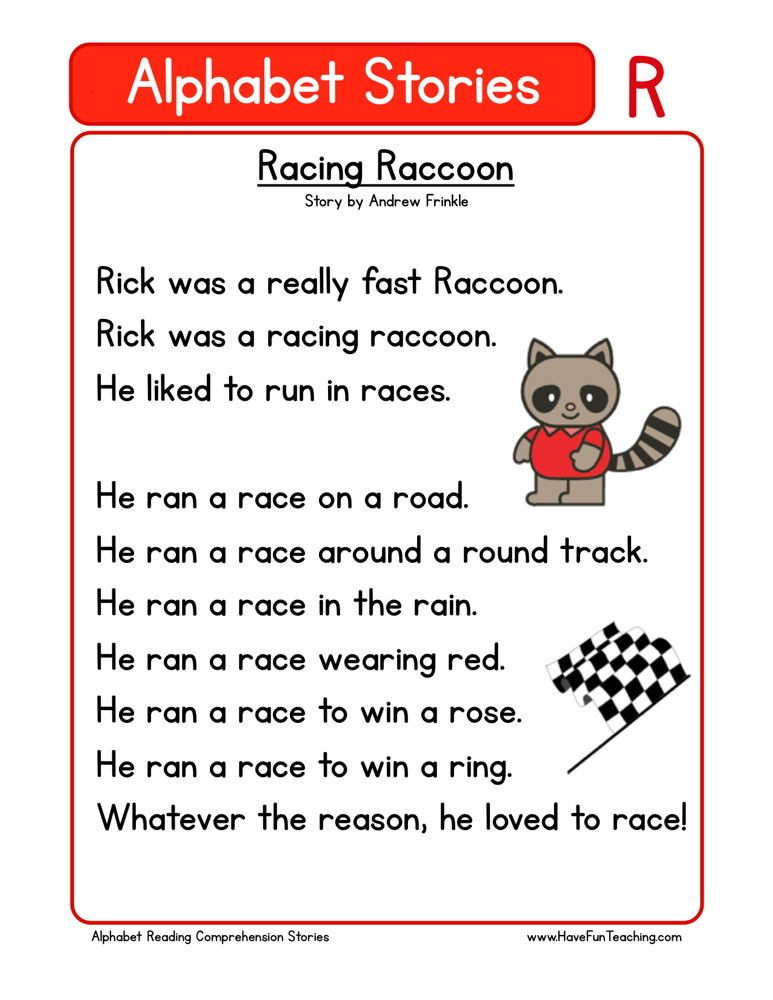

Teaching students to read music can seem a bit scary. It’s basically like learning a whole new language that is completely alien to them. The lucky thing is that, especially when they are young, kids have brains that are perfectly primed to take in new information and learn new skills.

To successfully learn how to read music, there needs to be some practice, repetition and commitment, but it doesn’t mean it has to be boring.

So what’s the best way to start teaching kids to read music? What are some exercises and tips? How can you make it fun? Read on to find out all this and more.

First Steps For Kids Learning to Read Music

For most kids, they start learning how to read music because they are learning how to play a particular instrument. This is a great way to get the ball rolling because the student will learn the notes as they go. They get to pick up music knowledge almost on the fly, and they see the results of their education almost in an instant.

This is a great way to get the ball rolling because the student will learn the notes as they go. They get to pick up music knowledge almost on the fly, and they see the results of their education almost in an instant.

Still, there are a few steps music teachers, and parents can take to help make the learning process easier and more fun for students.

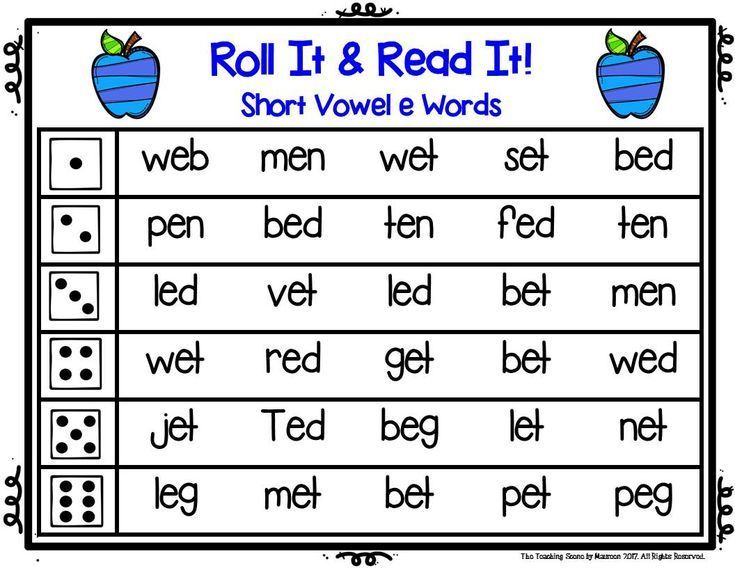

Learning the Note Time ValuesIn written music, there are different time values for notes. It’s a bit like learning the value of ‘number 1’ and then learning that you can also have a ‘half, quarter, eighth’ and so on. Depending on how old the student is, this can be taught through explaining the math, or it can be done with some games that involve rhythm.

The different note time values can also be introduced like a family. A whole note can be the Grandma, a half note the Mom, then a quarter can be a big sis and the eighth a little sis.

Learning the Names of the NotesOnce students have a firm grasp of how different notes can have different time values, it’s a good idea to introduce them to the proper names of these notes. This is where students can first see that each sound in music has a letter value attached to it.

This is where students can first see that each sound in music has a letter value attached to it.

Piano keyboards are made out of a collection of white and black keys. The black keys are always in groups of twos and threes. If you find a group of two black keys on a piano, the white key immediately to the left of the first black key will be a ‘C’ note.

From there, the white keys are given the values, ‘C, D, E, F, G, A, B’, which makes an octave. The next ‘C’ starts a new octave.

If you have access to a piano or keyboard, a fun game can be to label the notes in an octave, so the student gets used to their position, then for fun, remove the visual aid and ask them to find different notes on the piano, just like in a game of memory.

SolfegeIt sounds like it could be an expensive dish at a French restaurant, but Solfege is just another method for learning the order of notes in music theory. It’s that old ‘Do-Re-Me’ song almost everyone has heard at some point in their lives.

It’s that old ‘Do-Re-Me’ song almost everyone has heard at some point in their lives.

The basic principle of Solfege is to replace the music notes with one-syllable sounds that are easy to sing.

C becomes Do

D becomes Re

E becomes Mi

F becomes Fa

G becomes So

A becomes La

B becomes Ti

So a full rotation of the notes is; Do-Re-Mi-Fa-So-La-Ti. The reason this method has been used for so long is that it really helps to cement the sounds of the notes in the memory of a student. To prove a point, anyone who remembers the above song from ‘The Sound of Music,’ can accurately produce a ‘C’ note just by singing that song.

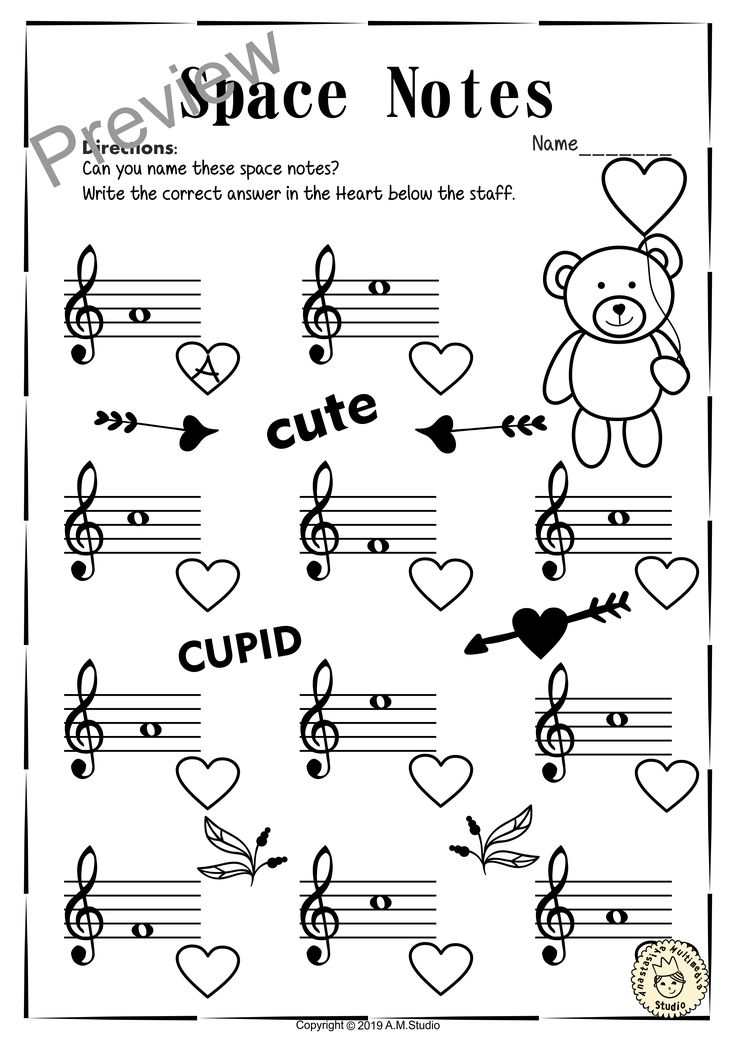

Understanding the Stave and the ClefsThis can be a part of music theory that makes many teachers nervous because it might seem like a gargantuan task to explain what exactly these things are, why they are important and how they work.

The simplest way to introduce a student to staves and clefs is to explain that they are just tools that help people write and understand music. Just like in math, symbols stand for things, and there’s a specific way of writing so that it can be understood by everyone.

Just like in math, symbols stand for things, and there’s a specific way of writing so that it can be understood by everyone.

The stave is the place musical notes are written, and clefs help people to understand if the music is low or high. It’s that simple.

Methods For Teaching Kids to Read Music

There are probably as many methods for teaching kids to read music as there are instruments to play. One of the great things about this is that there’s no real limit to how inventive a teacher can be in the music classroom.

Even though the different approaches are limitless, there are some points that should be included to make sure students get the most out of their musical education.

1. Learning Lines and Spaces

This is where students can explore the musical stave and understand how it is formed and what each of its components does.

The musical stave is made up of 5 horizontal lines; each of them is set apart equally. In sheet music, each line on the musical stave represents a note, and so does each space between the lines.

When a note is written on a stave, the line or space it sits on determines what note it is.

Teach the 5 Line NamesThis is where a little bit of poetic creativity can be an asset. On the musical stave, each line represents a note. Starting from the very bottom line and moving upwards, the notes are E, G, B, D, F.

One of the simplest ways to get students to memorise this is to teach them a phrase where each word starts with the letter of the note it represents.

A great example of this is; Every Good Burger Deserves Fries. It’s a great phrase because it’s easy to remember, and to be honest, it’s one hundred per cent true.

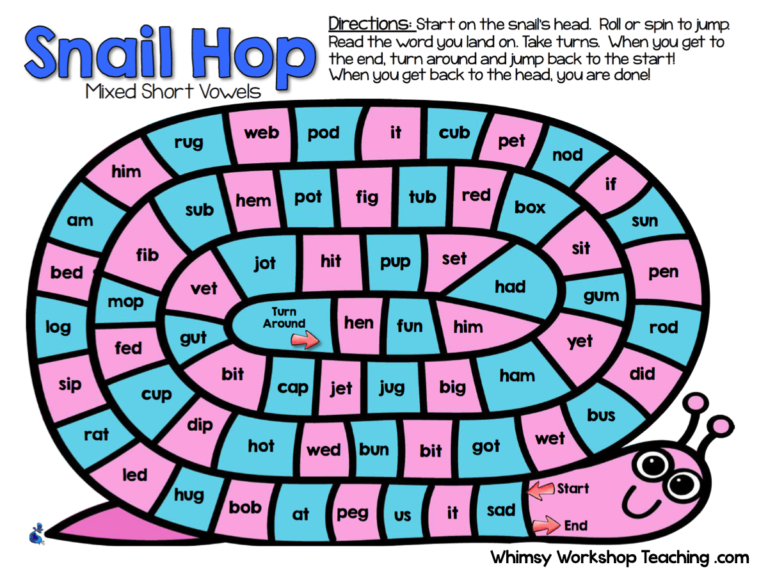

Teach the SpacesOnce students have learned the notes that the lines of the stave represent, it’s time to learn the spaces.

When it comes to learning the notes of the spaces, the word of the moment is FACE. Starting from the bottom and moving up, the notes in the spaces of the musical stave are F, A, C and then E.

The brilliance of this (if the student is a native English speaker) is that the notes already spell a word they are familiar with.

Practice the Naming of NotesThis can be done by simply using the hands. If a teacher positions a hand with the palm towards their face and spreads the fingers apart, it can perfectly mimic a musical stave.

Each finger represents a line, and the spaces between them represent, well, the spaces.

Starting from the pinky finger, the notes can be alternated between finger and space. The pinky finger is E, the first space is F, the ring finger is G, the second space is A and so on.

By simply using hands to demonstrate this, a student is given a new perspective on the musical stave that can go with them anywhere.

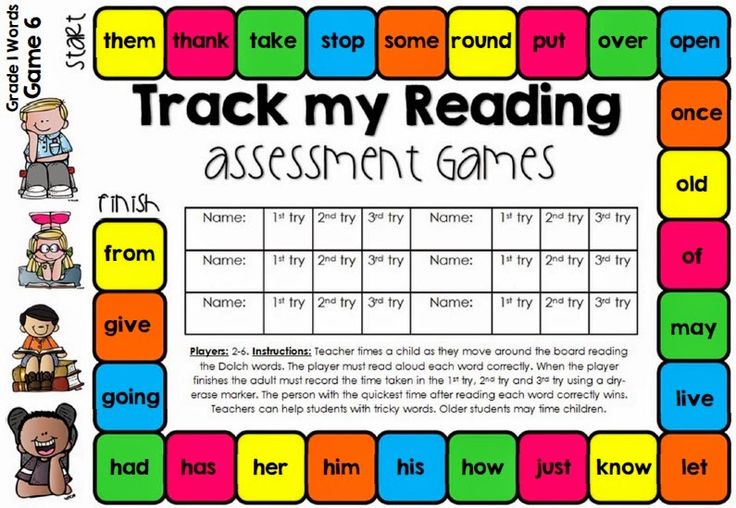

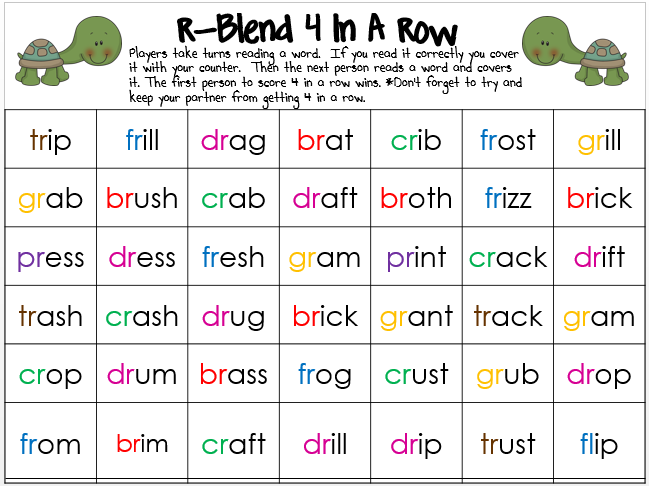

Introduce Flashcard Games for MemorisingAdding the element of play into any kind of lesson is bound to pique the interest of students and further cement the concepts they are learning into their conscious brains.

Flashcards and games are an easy and effective way to strengthen the work that is done in the classroom. An easy flashcard game could be to draw some notes on music staves. If the student picks the note out from the deck of flashcards, they need to correctly play it on the piano to win a point.

This kind of game can also be done with pairs of notes like a version of ‘memory.’ If students are more advanced, the flashcards could contain sections of music that they need to arrange together in the correct order to be able to play it.

Teach the RhythmOnce the students have understood pitch, it’s time to teach them rhythm. The best way to begin this is to get them to focus on being able to keep a single steady beat. A great real-life example of this is to march. Marching (like a soldier) can get them up on their feet but also experiencing the concept of rhythm in real-time.

A great exercise could be to play different pieces of music, and the student needs to figure out how slow or fast they need to march to match it.

Another simple exercise is to clap a rhythm and see if the students are able to clap it back instantly. This can be mixed up with different kinds of percussion; handclaps, shoulder taps, thigh slaps and so on.

Familiarity With Individual NotesIt’s incredibly beneficial to get students familiar with the appearance and shape of musical note symbols as early as possible. This can be started by simply showing a large image of the symbol and asking the students to describe it. This will get them thinking about what makes this symbol unique.

Then, take the time to explain what the symbols mean, introduce their proper names and how they work in a piece of music. Encourage students to ask questions or share any interesting things they notice about the symbols because this will help commit them to memory.

Introduce Music Notation GamesJust like with learning another language, in music theory, it’s also important to practice listening, reading, and writing.

Just as with the other elements, a teacher can inject some fun into music notation by doing it through games and challenges. Start simple by playing notes on the piano that the students are familiar with and see if they are able to use the correct symbol in the correct space or line on the music stave.

Prizes are always a great motivator, whether they be stickers, treats or free time to bash something out on that drum kit every single one of them is drawn to when they enter the music classroom.

Teach PitchIn music, pitch refers to the placement of individual sounds in a possible scale of sounds. Some are higher, and some are lower. When these sounds are given a value, that’s what is referred to as a note.

Music is basically a combination of pitch and rhythm, and both of these concepts are the basis from which students should build their musical education. They can be taught at the same time, but eventually, they tend to meld into one element.

However a teacher decides to address pitch in the early stages of music education, it’s important that it remains interesting and fun. A concept like pitch can very easily become overwhelming, so keeping it as light and hands-on as possible will ensure the best results.

2. Word Rhythm Association

In this kind of activity, students explore the mathematical relationships between rhythm values.

For example, they can be given words like; walk, run, hop, jump. Each one of these words corresponds to a rhythm value. So if walk is a full count of 4 and run is a half, then run needs to be twice as fast as walk.

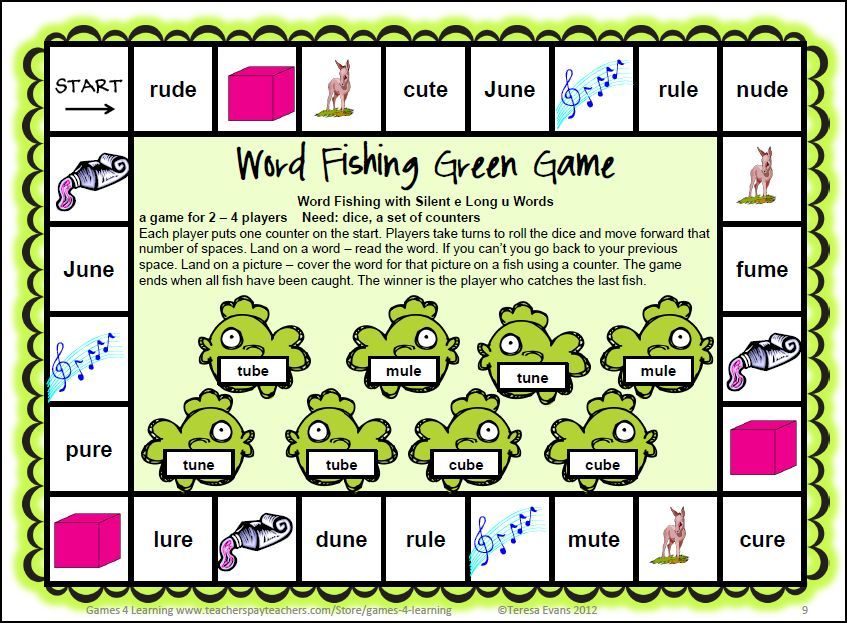

3. Associate Pitch With Colours

Associating pitch with colours doesn’t necessarily add anything for all students, but it has been shown to provide success with some.

The basic idea behind it is to associate a specific pitch with a solid colour. When a student sees that colour, their task is to name and play or sing the pitch. There are simple instruments available that have solid colour coordination to them, like xylophones, that are perfect for this exercise.

There are simple instruments available that have solid colour coordination to them, like xylophones, that are perfect for this exercise.

There are even unique people who see music as colours. This rare condition is called chromesthesia.

Kids Can Learn to Read Music Through Apps

There’s an app for just about everything now. Everything from grocery shopping to booking a doctor’s appointment to even finding the best app for something, has an app. The same can now be said about helping kids learn to read music.

The Mussila music school is an award-winning app that combines play with technology to give students a completely comprehensive music education that they can access from the comfort of their own living rooms.

Mussila has been designed with the student in mind, and the best part about it is it can be used without parent supervision. It’s great to be involved in your child’s life, but it is also nice to have an activity they can do that doesn’t need constant supervision.

Mussila takes a student through different learning streams to cultivate a complete music education that includes music theory and plenty of practical exercises.

Mussila is a great way to take advantage of the technology available to give students a solid understanding of music theory. To find out more about how Mussila works, click here.

Kids Can Learn to Read Music Through Online Games and Websites

There are thousands of great websites available that can provide some tools for music education. Many of them offer worksheets, games, lessons, hints and other activities to complement the musical education a student might already be involved in.

A good piece of advice is to test some out as a parent first. See what the process is and if it will be a good fit for the student. Any piece of additional exposure to music education is always a helpful tool.

Help Kids to Learn Music Theory

Many parents are afraid that they will ‘get in the way’ of their child’s musical education, especially if they aren’t musically educated themselves. The truth of the matter is that parental involvement in the education process is incredibly beneficial to kids.

The truth of the matter is that parental involvement in the education process is incredibly beneficial to kids.

Many studies have shown that even just helping kids with homework provides immense long-term benefits like better critical thinking skills, better academic performance and better communication skills. It’s also just a great time to bond with kids and get to know what is currently making them tik.

Taking the time to help children understand music theory isn’t just beneficial; it’s fun and a great time to bond and explore together. If the parent doesn’t have any music education, they might also learn something for free.

Conclusion

Learning to read music is an essential skill for any student who wants to pursue a musical endeavour. It’s one of the most fundamental pieces of the musical education puzzle, and it might seem like a daunting task, but it doesn’t have to be.

Learning to read music can be a fun experience for all involved. One that makes lasting impressions on young people and inspires them to continue to learn later in life.

Books about music for children - children's musical literature

Music is limitless! Ageless classics, rebellious rock, free-spirited jazz… The basics of musical trends and acquaintance with key performers are in a selection of books about music for children from Umnaziah.

STORIES ABOUT GREAT COMPOSERS

Nina Dashevskaya Seasons. Musical history »

Nina Dashevskaya is a professional musician, that's why all her books are filled with genuine love for music. The story about Vivaldi for children is an amazing story about the composer. First, the author introduces readers to the young Antonio, and then, through the conversation of our contemporaries, the boy and his grandfather, shares his impressions and thoughts about his immortal "Seasons".

Edition features:

- A fascinating story, not just a dry biography of the musician.

- Fine illustrations by Alexandra Semyonova create a special, airy atmosphere of the publication.

- The book includes Vivaldi's sonnets "The Seasons" translated by Mikhail Yasnov + musicological commentary.

For whom? Children aged 5 and over.

Edition features: 64 pages, offset printing.

Alexander Tkachenko « Johann Sebastian Bach »

A book from the Nastya and Nikita series. An excellent, accessible summary of Bach's biography for children who are learning to read on their own. The brilliant composer appears before us as a living person, and it is this acquaintance that is remembered most vividly.

Chips of the edition:

- Instead of the boring “I was born, studied, wrote music”, fascinating moments from the life of Bach are presented. For example, how he played with his feet in front of the future king of Sweden.

Or as a little boy at night, in the dark, he copied notes.

Or as a little boy at night, in the dark, he copied notes. - A4 format, large print - ideal for independent reading.

For whom? Children aged 5 and over.

Edition features: 24 pages, offset printing.

Sergey Georgiev « Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Bright Angel »

Ask anyone to name the great composers - and Mozart's name will be among the first. The book by Sergei Georgiev tells about the path of little Wolfgang to world fame.

Book tokens:

- Beautiful book design: fabulous illustrations turn the story into a real theatrical performance.

- Fascinating biography-journey of Mozart through European cities.

- Large format, large print, clear text - what beginner readers need.

For whom? Children of primary school age.

Features: 32 pages, coated paper.

Boris Evseev “ Tchaikovsky, or a magic feather ”

Book “Tchaikovsky, or Magic Feather” briefly tells about the world famous author of the “Shchelkunchik” and Slagkunchika Lake ". Facts from real life are wonderfully intertwined with fiction. Victoria Fomina's illustrations create a magical mood.

In this biography for children, Tchaikovsky appears not as a musical star of the first magnitude, which cannot be reached, but as a person with his own experiences and feelings.

Features of the book:

- Fascinating illustrations and overall beautiful design of the book.

- An unusual plot with a philosophical moral: "The most magical fairy tale sometimes turns out to be truer than any story."

- A great gift for those who are passionate about music.

For whom? Children of secondary school age.

Features: 72 pages, coated paper.

Acquaintance with the classics

Book series “ Musical classics for children ”

The books of this series presented a world classic, including Russian musical culture. World famous ballets, operas, orchestral concerts, musical biographies…. "Romeo and Juliet", "The Nutcracker", "Cinderella", "Swan Lake" - a real concert hall in your home! Simple but captivating texts will help you feel the spirit of the work and ... immediately begin to listen to it.

Chips:

- Two dozen books from which you can collect a collection of masterpieces of world musical culture.

- Included with each book is a CD or QR code with a recording of the work(s).

- Gorgeous artwork.

For whom? Children of preschool and primary school age.

Edition features: 32 pages (each book), coated paper.

Robert Levin « Music. Children's encyclopedia. The history and magic of the classical orchestra »

In the first part of the encyclopedia, the young reader briefly gets acquainted with representatives of the world musical culture who lived and worked in different eras and in different styles. Mozart, Tchaikovsky, Bach, Vivaldi and other great names.

The second part is devoted to the structure of the orchestra and talks about what instruments are involved in it, how they look and sound.

Features of the book:

- Guide to the world of classical music, Orchestral Bob, leads the reader through secret paths behind the scenes of the classics.

- References to specific pieces of music.

- Simple and understandable language of presentation.

For whom? For primary and secondary school age.

Edition features: 96 pages, offset printing.

Marx Anthony « Classical music »

The author has managed to create a book that will interest even younger students in the classics. Colorful, informative, and even with stickers!

Book chips:

- Stickers are the key to attracting even the youngest audience!

- The book is decorated very subtly, stylishly and tastefully.

- QR codes for scanning and listening to music as you read.

For whom? For children and adults. The book will be of particular interest to children who have begun to study music.

Edition features: 32 pages, softcover, stickers.

Modern musical directions

World Musical culture would be incomplete without such a iconic current, as rock. Book chips: For whom? Good for the first acquaintance with the rock of children and teenagers, and as a gift to a music lover. Edition features: 48 pages, offset printing. Discover jazz together with your children: get to know the movement in general, famous jazzmen and their instruments. Chips of the book: For whom? According to the author, "it is for children and the younger generation - so that they immediately start listening to jazz from the very best that has been done in this genre." Edition features: 96 pages, offset printing. Even more interesting musical tasks are waiting for the child in the exciting online course from Umnaziah called “Composers and classical music”. Even those children who were not at all interested in the classics, after it they will be able to distinguish the works of one composer from another, learn interesting facts about music and its creators. Developing the horizons of children aged 6-13 In just a couple of months, your child will master the basic topics of erudition: from famous Russian artists to great civilizations, objects of architecture and scientific discoveries learn more Original taken from duchesselisa in Music, dancing, drawing and reading for children of the nobility As for the Russian language, after mastering the initial literacy, it was usually given almost no attention, believing that "it will sweeten itself." In the aristocratic environment, Russian was considered one of the secondary ones, similar to Swedish or Polish, which you can know, but, due to the limited use, it is not necessary. In fact, it was only possible to communicate with servants on it, and this did not require much eloquence. The situation of French-speaking people in 1812 looked almost tragicomic, when in the diaries and correspondence of the Russian nobility "the greatest hatred for the French was expressed in the purest French." The impetus for mastering the Russian language was the educational policy and personal example of Nicholas I. As they said, the very next day after his accession, the emperor, going out in the morning to the courtiers, loudly greeted them in Russian, saying: "Good morning, ladies and gentlemen" . At the end of the 1820s, the first two detailed and systematic grammatical manuals in Russia written by N. I. Grech arrived in time: "Practical Russian Grammar" (1827) and "Short Russian Grammar" (1828) - and began to be used as textbooks, Well, literature did the rest. The desire to read Pushkin, Lermontov and Gogol soon forced even foreigners to learn Russian. As B. The most suitable age to start learning to dance was considered to be five or six years old. Classes were held from two to four times a week, for several hours, both individually and in a group. Children were taught almost as seriously as professional ballet dancers: they mastered ballet positions, pas (steps) and entrecha (jumps), memorized rather complex figures of ballroom and characteristic dances. For many children, especially boys, dancing was a heavy burden. At the dance lessons, they mastered the entire classical and fashionable dance repertoire. They taught to dance "Hungarian", and "bolero", and "kachucha", and "in Tyrolean", and "in gypsy", and "a la Greek", and various other "manners", because in addition to fashionable pairs dances, the program of balls (especially on the occasion of home holidays) necessarily included solo performances and small ballets performed by small and large children (this was called a "dance surprise"), including the famous pas de châle (dance with a shawl), in which , as you remember, Katerina Ivanovna shone at Dostoevsky's graduation ball, and pas de couronne (dance with a wreath), and all kinds of tarantellas, "Persian dances", etc. In turn, the young "ladies" used the children's balls to rehearse adult relationships. Memoirist E. A. Naryshkina, who grew up in the countryside and therefore not very secular, recalled (1850s): "Sometimes we were taken to children's balls ... The girls we met represented a special new type for me. They were elegant and smart like real little ladies, and were able to speak in secular jargon about secular things. Girls were taught to play the piano or harp, boys were also taught the piano, violin or flute. The number and duration of music lessons could vary - from two lessons a week for boys, who considered music less necessary, to daily classes for girls, for whom playing a musical instrument was not only a way to subsequently "please" a spouse, but also a means of attracting secular attention. Therefore, as it was often recalled, music lessons from the age of seven became at first "a cross carried out of humility, then a torture to which they obeyed in the name of discipline." Musical mentor could be your own yard musician or a European celebrity - A. Henselt, J. Field and others, who taught many talented offspring of the capital's nobility. Of all the "pleasant arts", drawing was given the least attention, unless the child was so carried away that he begged for additional lessons. In general, it can be said that the education of the nobility was noticeably improved. The number of subjects taught was reduced: the random was cut off, the necessary was added. No upbringing and education is possible without extensive and systematic reading; it forms the thinking of a person, his worldview, contributes to the development of self-consciousness. For a long time, the influence of reading on Russian noble education was hampered by two circumstances: the lack of habit and the absence of the books themselves. Until the second half of the 18th century, and in the provinces even before the 19th century, in a rare house one could find some kind of book, and then mainly of a spiritual content - the Psalter or the Saints, or Engalychev’s medical manual or some kind of calendar, like in Onegin’s uncles: Gradually, however, things got off the ground. Already A. T. Bolotov read quite a lot - everything that came to hand. He especially remembered "The Adventures of Telemachus" in Russian translation. “Through it I received the concept of mythology, of ancient wars and customs, of the Trojan War…,” he recalled. “In a word, this book served as the first stone laid in the foundation of my future learning, there were so few Russian books that not only libraries, but not the slightest collections were anywhere in the houses. Ya. P. Polonsky, who was brought up at the beginning of the 19th century, also in the provinces (his parents did not know French and spoke Russian in the family), recalled: “When I was over seven years old, I already knew how to read and write and I read everything that came to hand, and all the old, sometimes very old books came to my hand, in leather bindings with dried bugs between the pages: editions of the time of Catherine - Plavilshchikov's comedies, and especially the memorable "Mermaid" - a magical performance with transformations and verses. Here, if I'm not mistaken, is the beginning of one verse: I had an excellent memory for poetry, for eight or nine years I already knew by heart the best fables of Krylov, all the fairy tales of Dmitriev, the monologues from the comedies of Knyaznin and some of the tragedies of Ozerov. I read poems aloud, and to whom? To my nanny and all the illiterate household, who, as it seemed to me then, listened to me with great pleasure, even gasped with pleasure!0391 AP Butenev read Bogdanovich's Darling, poems by Sumarokov, Lomonosov and Karamzin, the first volume of Leveque's History of Russia translated from French, and Fenelon's novel Telemachus. For a long time, neither parents nor tutors interfered in the relationship of a child with a book, unless they found that reading interferes with the child's lessons, and then they locked the books (from under which young book lovers still found ways to get them). It was not until the second third of the 19th century that parents came to the conclusion that adults should control their children's reading and that before allowing a child to take a book, they should definitely read it themselves. Especially many restrictions arose in adolescence, when all literature that was even slightly questionable in relation to morality, mainly French novels, was banned. It must be said that many of the adults who were brought up in their time on non-children's literature did not understand this system of prohibitions. So, I. I. Dmitriev wrote: “Reading novels had no harmful effect on my morality. I even dare to say that they were for me an antidote against everything low and vicious. The Adventures of Cleveland, The Adventures of Marquis G. elevated my soul I have always been captivated by good examples and willingly wished to follow them. M. K. Tsebrikova found that even books that were incomprehensible to children did not bring "anything but benefit. The incomprehensible aroused a thirst to understand; poorly understood was understood correctly after a few times; children learned to correct their mistakes." In addition, "children generally understand much more than their educators imagine." After the first translated children's books, it was time for the writings of our own Russian authors. Pretty soon, by the beginning of the 19th century, children's literature began to be published in different countries, and English was considered the best. In the 19th century, talking about literature and book novelties became an obligatory topic of secular communication not only in the capitals, but also in the provinces. Now all worthy books were diligently read by society ladies and young people and then discussed in a decent manner. More mature men, due to lack of time, did not always have time to follow the literature, but they also tried to "correspond". So, Emperor Alexander I, who valued the reputation of an amiable secular person, used the retellings of his wife, Empress Elizabeth Alekseevna. During joint dinners, she told him about worthy novelties, reported her own opinion, and Alexander was fully equipped to maintain an easy conversation. Characters who read little or thoughtlessly often became a laughingstock. The Moscow beauty Princess Urusova, impeccable in everything except her intellect, once became famous for answering the question of a ballroom cavalier: "What are you reading now?" - she murmured: "A pink little book. It can be said that by the middle of the 19th century, both the traditions and the circle of children's reading were fully formed. In addition to children's books for different ages, there are Russian and world classics, books about travel, about animals, and historical works.

Susana Monagudo “ Illustrated History of Rock ” 9000 9000  Cult bands and musicians, legendary albums and songs, styles, festivals, fans, record companies, music media - all this is described briefly but succinctly in the encyclopedia. The publication covers the period from 1950s to early 21st century.

Cult bands and musicians, legendary albums and songs, styles, festivals, fans, record companies, music media - all this is described briefly but succinctly in the encyclopedia. The publication covers the period from 1950s to early 21st century.

Nelli Zakirova « Jazz. Children's encyclopedia » (+ CD)  The encyclopedia is written in a clear and interesting language. The book is not overflowing with information, but it allows you to feel the very essence of jazz, and this is much more important!

The encyclopedia is written in a clear and interesting language. The book is not overflowing with information, but it allows you to feel the very essence of jazz, and this is much more important!

And at the end - a final test to consolidate knowledge and a valuable certificate for your child's portfolio!

And at the end - a final test to consolidate knowledge and a valuable certificate for your child's portfolio! Music, dance, drawing and reading for noble children

A. M. Turgenev testified: "I knew a crowd of princes Trubetskoy, Dolgoruky, Obolensky, Khovansky, Volkonsky, Meshchersky ... who could not write even two lines in Russian." Many owned a very limited vocabulary, not going beyond narrow everyday topics, used common language forms (such as "nadys", "eftot", "nadot", etc.) and found it difficult to freely conduct a conversation.

Those who were brought up abroad often returned to Russia, completely unable to speak Russian. Prince D.V. Golitsyn, who had been governor-general of Moscow for about 20 years, lived abroad until the age of eighteen and at first hardly spoke Russian. Subsequently, he learned, but spoke Russian, although quite correctly, but with a noticeable accent, like a foreigner.

Prince P. A. Vyazemsky recalled about his father that he, "like almost all people of his time, spoke more French. Zhukovsky, who was brought into our house by Karamzin, told me that he was always surprised by speed, dexterity and the ease with which, in conversation, my father translated into Russian thoughts and phrases that, apparently, were formed in his head in French.

Many of the Decembrists did not know Russian at all or almost. So, MP Bestuzhev-Ryumin during the investigation, sitting in the Peter and Paul Fortress, was forced, answering interrogation points, to leaf through the French-Russian lexicon for hours in order to correctly translate his testimony, which he composed in French. M. S. Lunin hardly spoke Russian. The brothers Muravyov-Apostles, who were brought up in France, knew the language rather poorly - of them, Matvey Ivanovich subsequently, in Siberia, by ear and thanks to reading Russian books, mastered the language quite well, and Sergei, due to his early death, did not have time, even hesitated to write in Russian. Russian, etc.

Poor knowledge of the Russian language was also facilitated by the fact that throughout the entire 18th and early 19th centuries it was constantly changing, generally recognized grammatical norms were practically unknown, and grammar textbooks were almost absent.

Many, following M. A. Dmitriev, could say: "They did not teach me Russian grammar, but there was no one to teach: no one even knew the spelling."

In general, they learned their native language mainly by copying copybooks and memorizing a few Russian poems - about the same as foreign ones. And in most cases, they did not think about spelling. Even Princess E. R. Dashkova, the president of two Academies and the author of articles in the explanatory dictionary of the Russian language, signed her last name "Dashkava".

Since his predecessor, Alexander I, always greeted in French, the most perceptive of the courtiers immediately felt that new times were coming. And so it turned out. From that time on, Nicholas spoke in French only with diplomats and ladies and was very annoyed if a subject could not keep up the conversation in Russian. And to write - letters to his sons and business papers - Nikolai also began to write in Russian, since he had good teachers and he did it quite competently. As a result, in a matter of months, the French language disappeared from Russian office work (with the exception of the diplomatic department), and the courtiers and the nobility of the capital vied with each other to invite teachers to study in Russian.

From that time on, Nicholas spoke in French only with diplomats and ladies and was very annoyed if a subject could not keep up the conversation in Russian. And to write - letters to his sons and business papers - Nikolai also began to write in Russian, since he had good teachers and he did it quite competently. As a result, in a matter of months, the French language disappeared from Russian office work (with the exception of the diplomatic department), and the courtiers and the nobility of the capital vied with each other to invite teachers to study in Russian.

A. D. Galakhov turned out to be one of these mentors, in demand by the Moscow "light". First, he was invited to the house of Prince P. P. Gagarin. “A young prince of 14 years old,” Galakhov recalled, “already had an excellent command of French, much better than his native language. in the family of the prince and in the circle of his acquaintance, French was almost constantly heard. Thanks to the recommendation of the prince, I soon found lessons in other houses where I faced the same difficulty, that is, the dominance of the French language. However, both the students and their parents. Both liked the way they expressed my method, and the whole merit of this method lay in the clarity of interpretation, and perhaps even in the fact that, knowing French grammar, I often resorted to it to explain Russian grammar. and the fact that I was of the nobility and behaved differently in the lessons than teachers from seminarians, either who did not know French at all, or, with knowledge, frightened their pupils and pupils with a nasty reprimand, which was then paid special attention, appreciating it higher theoretical knowledge, no matter how capital it is ...

However, both the students and their parents. Both liked the way they expressed my method, and the whole merit of this method lay in the clarity of interpretation, and perhaps even in the fact that, knowing French grammar, I often resorted to it to explain Russian grammar. and the fact that I was of the nobility and behaved differently in the lessons than teachers from seminarians, either who did not know French at all, or, with knowledge, frightened their pupils and pupils with a nasty reprimand, which was then paid special attention, appreciating it higher theoretical knowledge, no matter how capital it is ...

"Agility in all bodily exercises" and "pleasant arts"  N. Chicherin recalled: “The physical side was not forgotten in our upbringing. Father insisted that we acquire dexterity in all bodily exercises. ten, fifteen miles on horseback. Tenkat (tutor) taught me to swim decently, which was always a great pleasure for me. We began to learn fencing already in Moscow ... Dance classes began at the age of twelve, and this was the only lesson that, especially at first , was a real torment for me ... My father knew that all the dexterity and skill acquired in a hostel, acquired by a person, constitute an advantage for him.

N. Chicherin recalled: “The physical side was not forgotten in our upbringing. Father insisted that we acquire dexterity in all bodily exercises. ten, fifteen miles on horseback. Tenkat (tutor) taught me to swim decently, which was always a great pleasure for me. We began to learn fencing already in Moscow ... Dance classes began at the age of twelve, and this was the only lesson that, especially at first , was a real torment for me ... My father knew that all the dexterity and skill acquired in a hostel, acquired by a person, constitute an advantage for him.

Items that helped a child to become a man of the world, a true representative of his class, were given special attention.  Particularly difficult in dancing are the "first position", in which the heels of the legs are connected and the toes are turned so far to the sides that the feet form a perfectly straight line, and also the "fifth position", when the legs are crossed and the feet are placed one against the other, so that the toe one foot touches the heel of the other.

Particularly difficult in dancing are the "first position", in which the heels of the legs are connected and the toes are turned so far to the sides that the feet form a perfectly straight line, and also the "fifth position", when the legs are crossed and the feet are placed one against the other, so that the toe one foot touches the heel of the other.

BN Chicherin recalled what a punishment for him - already a teenager - these lessons were. He was painfully embarrassed about his dance costume, "girly" shoes with bows, the need to take dance poses in public and jump. “I wanted to be a serious young man, I spent whole days delving into books, and they dressed me in a jacket and shoes and forced me to dance. I could not digest this ... Dressing for dancing became a tragic event, each step of which required violence against myself.”

Chicherin studied so-so (although later he considered that the constant breaking of himself in dance lessons was good for his character) and subsequently suffered somewhat from this. “Over time, moving in the big Moscow world, I saw that my parents were quite right in insisting that we learn this very natural exercise in youth meetings, and even regretted that, under the influence of childish prejudices, I never wanted to learn him okay."

“Over time, moving in the big Moscow world, I saw that my parents were quite right in insisting that we learn this very natural exercise in youth meetings, and even regretted that, under the influence of childish prejudices, I never wanted to learn him okay."

Russian dances were also very popular. Already in the second half of the 18th century, slightly ennobled ballet dances in the Russian style were staged, necessarily, almost every evening, performed by imperial artists in theatrical "divertissement" - small combined concerts, which traditionally ended in those days. every performance. "In Russian" fashionable French dancers often danced here. Similar "Russian dances", which retained all the traditional movements, but a little "dramatized" dance master, were taught to noble children, and many parents, including very noble ones, willingly demonstrated the talents of their children. So, in Moscow at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries, the young Countess Anna Alekseevna Orlova was very famous for her ability to dance in Russian. Many contemporaries recalled how, during balls, her father, Count A. G. Orlov, ordered the musicians to play the Russian song "I walked through the flowers," and Countess Anna received well-deserved admiration for her dancing art. Her dance teacher Balashov, the choreographer of the dance, was usually here, and he also received compliments.

Already in the second half of the 18th century, slightly ennobled ballet dances in the Russian style were staged, necessarily, almost every evening, performed by imperial artists in theatrical "divertissement" - small combined concerts, which traditionally ended in those days. every performance. "In Russian" fashionable French dancers often danced here. Similar "Russian dances", which retained all the traditional movements, but a little "dramatized" dance master, were taught to noble children, and many parents, including very noble ones, willingly demonstrated the talents of their children. So, in Moscow at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries, the young Countess Anna Alekseevna Orlova was very famous for her ability to dance in Russian. Many contemporaries recalled how, during balls, her father, Count A. G. Orlov, ordered the musicians to play the Russian song "I walked through the flowers," and Countess Anna received well-deserved admiration for her dancing art. Her dance teacher Balashov, the choreographer of the dance, was usually here, and he also received compliments.

In the provinces, especially among the lower nobility, the main place at every ball was occupied by Russian dances, which were often taught directly from the peasants.

E. I. Stogov recalled the wedding of his relatives in Ruza near Moscow at the beginning of the 19th century: “First they sang a congratulatory song, remembered the names of their uncle and aunt; then a dance song. everyone praised. Aunt, well-dressed, slender, with cheerful eyes, also received general praise. Uncle danced both the trepak and the Cossack, but as he squatted, he only flickered, some of the guests even screamed with delight. The young opened the ball, I remember all the dances ended in kisses. The couples changed for a long time, it seems that everyone was dancing.

In a similar way - both by observing peasant women and by taking lessons from a dance master - Tolstoy's Natasha Rostova could also learn Russian dance. At the time when Tolstoy's novel was written, of course, few of the nobles danced in Russian, but at the time of the book, this was a completely ordinary thing.

Dances were taught mainly by ballet actors - current and retired. In the 1800s, among them were such famous people as Didlo (mentioned by Pushkin), Kolosova, Novitskaya; in the 1830s-1840s - Munaretti, Gyullen-Sor, etc. About the end of the century, Princess L.V. Vasilchikova recalled: "From childhood, my contemporaries and generations older than me took lessons from the old man Troitsky. We lined up at one end hall, and he sat on the other opposite us and, crossing his legs, stroking his whiskers and clapping his hands if we made a mistake, commanded us like soldiers. Woe to the clumsy - then Troitsky mimicked us and humiliated us publicly.

The task of the dance master was to teach not only to dance, but also to freely stay in society, to move easily and naturally. Therefore, much attention was paid to bows and curtseys, the development of a beautiful posture, the position of arms and legs, even a special, "decent in society" facial expression. Here is how it was described in a dance textbook of the early 19th century: “The eyes, which serve as a mirror of our soul, should be modestly open, meaning pleasant gaiety. showing teeth."

showing teeth."

In the dance master's classes, they learned to sit down, walk, cross the hall, put on and take off their hats and gloves, get into the carriage, fan themselves with a fan, respectfully take and serve various objects, etc. There were subtleties in all this: for example, good tone did not allow neither when walking, nor when talking, to wave your arms, and the main sign of graceful gait was considered if the soles of the walker were not visible.

Dance masters, on the other hand, quite often arranged so-called children's balls. They were conceived specifically for teenagers aged 13-16, who already knew how to dance tolerably, but had not yet gone out into society due to their infancy. Children's balls, or children's holidays, as they were also called, were organized either in noble families on the occasion of the name day of one of the children, or by famous dance masters in their schools on common holidays - at Christmas, on Maslenitsa, etc.

In addition to teenagers, who were the majority at children's balls, adults also came there, and children had the opportunity to practice dancing and ballroom communication with "real" partners. If the ball was given by the dance master, he invited all his former students to the children's party. Children's balls began and ended earlier than usual congresses, and this made it possible for adults to go directly from there to the theater, and then to the big ball.

If the ball was given by the dance master, he invited all his former students to the children's party. Children's balls began and ended earlier than usual congresses, and this made it possible for adults to go directly from there to the theater, and then to the big ball.

Among the Moscow dance masters, the most probably famous, almost a legend, was Pyotr Andreevich Yogel, who came from France and began to teach Moscow children to dance in 1800, and stopped when he was already well over eighty, in the early 1850s years. He was a recognized master of his craft, through whose hands half the city passed. In addition to private lessons, he taught dancing to pupils of the University Noble Boarding School, including V. A. Zhukovsky, A. S. Griboyedov, M. Yu. Lermontov. By the end of Yogel's life, at his children's balls, the great-granddaughters met with their great-grandmothers, since both of them were the master's students. Naturally, when Leo Tolstoy wrote "War and Peace", he could not bypass the figure of Yogel with his attention and gave him his Natasha Rostova as a student.

In this respect I was aware of their unconditional superiority over me; I felt that I would never have spoken to them about what filled my head and my heart, so my role with them was rather passive.

If dances were taught to children of the nobility back in the time of Peter the Great, then the fashion for music lessons came later. In any case, S. A. Tuchkov remarked: “I never heard from the old people that any of the noble people in the reign of Peter I, Catherine I and even Anna was engaged in music: it seems that this custom has been made since the time of Peter III because he himself loved to play the violin and knew music, and then, perhaps, in imitation of Frederick II, whom he recklessly revered.

In the second half of the 18th century, music became one of those "pleasant arts" that diversify the leisure of a secular person, and it was included in the list of compulsory subjects for study.

Most of the girls practiced music every day for three or four hours: an hour lesson before lunch, after-dinner learning of the set and after tea an hour to play solo or four hands with their sister.

Technique, speed, and the ability to briskly play pieces and memorize these pieces without error, "for which one passage had to be hammered out for half an hour," were valued most of all in the game. The presence of abilities and even an ear for music was considered not the main thing (“after all, it’s not you, but you should be listened to”). Well, thanks to the excessive "musical duty" absolutely everyone was taught to play. At that time, it was generally believed that there was no such art that could not be learned. Except that it didn’t always work out with singing: few people agreed to listen to voiceless singing.

The presence of abilities and even an ear for music was considered not the main thing (“after all, it’s not you, but you should be listened to”). Well, thanks to the excessive "musical duty" absolutely everyone was taught to play. At that time, it was generally believed that there was no such art that could not be learned. Except that it didn’t always work out with singing: few people agreed to listen to voiceless singing.

MI Glinka, like later PI Tchaikovsky, was initially taught music by their governesses.

M. I. Glinka recalled: “Although music, i.e., playing the piano and reading music, we were taught mechanically, but I quickly managed to do it. Varvara Fedorovna (governess) was cunning at inventions. somehow disassemble the notes and hit the keys, now she ordered to attach the board to the piano over the keys so that it was possible to play, but it was impossible to see the hands and the key, and from the very beginning I got used to playing, despite the fingers.

E. A. Sushkova was taught music by her aunt, and here the results were less impressive. “At first she taught me the names of the keys. Then she somehow explained the notes, not saying that there are quarters, eighths, white, without explaining what a pause, treble, bass, tone are, and she showed everything from her hands and somehow she interpreted that "re" on the middle octave is written like this, on the lower octave - it always ended with her favorite phrase: "All this will come by itself, just take it apart more, and you will get used to reading notes like a book. " Without having the slightest idea about theory music, I had never seen or worked on scales, but they directly planted me for the plays of Steinbelt and Field ... Unfortunately for me, I was addicted to music, I studied it for four hours a day, but I must admit that no one ever recognized that I was drumming, something so familiar was heard, but out of hand ugly.  Usually one or two years, one lesson a week, was enough for the child to learn how to use a pencil and watercolor brush and master the skills of copying from "originals" - that is, exemplary lithographs or drawings made by professional artists - and the basics of composition. If more serious training was required, as was the case with M. I. Glinka, who passionately wanted to learn how to draw in childhood, then the child was seated for "drawing from the eyes, noses, ears, etc., demanding unaccountable mechanical imitation."

Usually one or two years, one lesson a week, was enough for the child to learn how to use a pencil and watercolor brush and master the skills of copying from "originals" - that is, exemplary lithographs or drawings made by professional artists - and the basics of composition. If more serious training was required, as was the case with M. I. Glinka, who passionately wanted to learn how to draw in childhood, then the child was seated for "drawing from the eyes, noses, ears, etc., demanding unaccountable mechanical imitation."

In some noble families, in the second half of the 18th century, they began to teach children and crafts. At the origins of this tradition was Emperor Peter, who, as you know, mastered almost thirty crafts in his life, including the ability to remove teeth. Peter was especially fond of working on a lathe, which occupied his hands and unloaded his head, and greatly contributed to raising the prestige of this occupation. Some of Peter's associates imitated him, and their own turners, one might say, came into fashion, especially since some other European sovereigns were also fond of similar "pure" crafts, for example, the unfortunate Louis XVI, who ended his days on the guillotine, who liked to tinker with all kinds of mechanics, assembled and repaired locks, clocks, etc. Catherine the Great knew how to cut stones and, at her leisure, successfully copied antique cameos; Empress Maria Feodorovna, wife of Emperor Paul I, like Peter, loved to sharpen things made of wood and bone on a lathe and often gave her husband her own products (he died clinging to the turned balusters that adorned the desk she presented).

Catherine the Great knew how to cut stones and, at her leisure, successfully copied antique cameos; Empress Maria Feodorovna, wife of Emperor Paul I, like Peter, loved to sharpen things made of wood and bone on a lathe and often gave her husband her own products (he died clinging to the turned balusters that adorned the desk she presented).

That's why the Russian nobles taught their children the "royal" turning art (as we remember, the old prince Bolkonsky also liked to relax at the lathe in "War and Peace"), watchmaking and bookbinding. At the end of the 18th century, this fashion received additional nourishment: to the ordeals of the French aristocrats expelled from their country by the revolution, the most far-sighted Russian parents took care to teach their children to do at least something useful with their hands, so that in which case they would not die of hunger  Languages ceased to be a means of showing off and became an instrument of knowledge; humanitarian subjects were filled with life specifics, grasping grew into erudition - all this served to form a truly refined personality, an aristocracy not only in blood, but also in spirit.

Languages ceased to be a means of showing off and became an instrument of knowledge; humanitarian subjects were filled with life specifics, grasping grew into erudition - all this served to form a truly refined personality, an aristocracy not only in blood, but also in spirit.

What to read?

And the calendar of the eighth year:

An old man, having many things to do,

He did not look at other books.

Most of the nobles did not read anything at all; others thought that too diligent reading of books, including the Bible, could drive a person crazy. Even in aristocratic families, until the time of Elizabeth Petrovna, there were almost no home libraries.

Due to the paucity of book collections, children for a long time grabbed literally everything they could reach, and all these were books for adults: classics in the language spoken in the family, a few translations into Russian, works by Russian authors.

A lot of different testimonies have been preserved about what exactly fell into the hands of children (and the first books read are best remembered).

Men in the world

Like flies cling to us,

Having in the subject,

To deceive us.

Sometimes there were also new, for that time, publications, such as "Memorable Russia" (with pictures), and the then "Picturesque Review". The first verses I read already encouraged me to imitate them. Most often, poems by Karamzin and Prince Dolgorukov came across in the publications of that time.

The first verses I read already encouraged me to imitate them. Most often, poems by Karamzin and Prince Dolgorukov came across in the publications of that time.

D. N. Sverbeev, at the age of nine or eleven, mastered everything that he found in his father’s small library: Russian poets of the 18th century, historical works, Karamzin’s “Letters from a Russian Traveler” and the “Moscow Journal” published by him, “And My Trifles” I. I. Dmitriev, the mystical writings of Jacob Bem, John Masson, Eckartshausen, fashionable in 1810–1820, the book of Jung Stilling, known in Russian translation as "Threats of Light Easters" and "Zion Collection" by A. F. Labzin.

I. Dmitriev, the mystical writings of Jacob Bem, John Masson, Eckartshausen, fashionable in 1810–1820, the book of Jung Stilling, known in Russian translation as "Threats of Light Easters" and "Zion Collection" by A. F. Labzin.

The same unsystematic reading continued much later. If a child was seized by a passion for reading, he was ready to grab any text in a binder, if only to satisfy this passion.

In many families from Russian literature, Pushkin was considered inconvenient for teenage reading for a long time. Ya. P. Polonsky testified: “Pushkin in those distant years was considered a poet not quite decent. Young people were not given his poems into their hands. But the forbidden fruit seemed more expensive, as if justifying Pushkin’s own poems: Heaven is not heaven for us.

Young people were not given his poems into their hands. But the forbidden fruit seemed more expensive, as if justifying Pushkin’s own poems: Heaven is not heaven for us.

Many hand-written poems by Pushkin went through the hands of high school students. So, not in print, but in hand-written notebooks, for the first time I managed to read both "Count Nulin" and "Eugene Onegin".

According to the story of Prince S. M. Volkonsky, his grandfather, the Decembrist S. G. Volkonsky, "when his son, a fifteen-year-old boy, wanted to read "Eugene Onegin", marked with a pencil on the side all the verses that he considered subject to censorship exclusion; can you imagine how easy it was to skip a line with the lightness of Pushkin's verse. Other contemporaries also recalled a similar practice - sticking or smearing Pushkin's lines with ink. Completely "rehabilitated" "Eugene Onegin" only in the second half of the XIX century.

Actually, children's literature was born in the second half of the 18th century, at a time when moralists and educators spoke more and more loudly about childhood - not only as a time of life, but also as a special stage in the formation of a person. Since then, gradually comes the understanding that a child is not an inferior adult (weaker physically and mentally, not formed bodily and incapable of reproduction), but a child, with his own level of worldview, abilities, rudiments of character, etc., that children it is difficult to read "big" books and one has to write specifically for them, so that it is both short and entertaining, and even written in simple language, without long scholarly words - and books appeared that were intended specifically for children's understanding.

Since then, gradually comes the understanding that a child is not an inferior adult (weaker physically and mentally, not formed bodily and incapable of reproduction), but a child, with his own level of worldview, abilities, rudiments of character, etc., that children it is difficult to read "big" books and one has to write specifically for them, so that it is both short and entertaining, and even written in simple language, without long scholarly words - and books appeared that were intended specifically for children's understanding.

The authors of the first such books were mainly teachers - German, and then English. The very first was the German Joachim Heinrich Campe (1746–1818). In the early 1770s, he published a little book called "Children's Library". It was a collection of songs and stories, fables and skits, intended for reading by both very young and grown-up children.

The success with the readers was so great that Campe soon published a second book, followed by a third, and so on, so that a little later the "Children's Library" really turned into a whole library, consisting of two dozen plump volumes. There were not only stories, poems and moralizing conversations, but also detailed descriptions of numerous journeys, glorifying the power of the human spirit and reasonable Divine predestination.

There were not only stories, poems and moralizing conversations, but also detailed descriptions of numerous journeys, glorifying the power of the human spirit and reasonable Divine predestination.

Almost immediately, in 1776, a Russian translation of Campe appeared under the title "A new kind of toy, or Amusing and moralizing tales for the use of the smallest children." This book was the beginning of children's literature in Russia.

Soon a whole library of children's reading - translations of the future children's classics: "Don Quixote", "Robinson Crusoe", etc. and the magazine "Children's Reading for the Heart and Mind" (1785–1789 - was created by N. I. Novikov. "' "Children's Reading" was perhaps the best book of all published for children in Russia, - later recalled M.A. Dmitriev. - I remember with what pleasure even adult children read it. Moskovsky Vedomosti "".

Alexander Semyonovich Shishkov (1754–1841) became one of the first children's poets. An outstanding statesman and public figure, admiral, minister of education and president of the Russian Academy, Shishkov was also a gifted poet. True, he was embarrassed to publish his poems for children in a separate book and "hid" them on the pages of the next translation of Campe's Children's Library, modestly writing in the preface: "This book is partly a translation, partly an imitation of the works of Mr. Campe."

It soon became clear that Shishkov was shy in vain. It was his poems that readers first noticed, thanks to them his book gained great fame and was in every educated family. And, starting to read, the children very quickly memorized the poems of Alexander Semenovich, for example, these:

We have all the joys,

Small children.

Toys and laughter,

And many things.

And my sister - a blue one."

And my sister - a blue one."

B. N. Chicherin recalled that his first introduction to literature occurred at the age of four, when his father, gathering around the table in the evenings of all the household, read aloud to them Krylov's fables, as well as other poems - Yazykov, Karamzin, Dmitriev, excerpts from " Boris Godunov" by Pushkin et al. dealing with them." The circle of children's reading included Nekrasov with his "Grandfather Mazai" and "General Toptygin", and "The Life of Animals" by Brem, and the books of Jules Verne, Fenimore Cooper, Mine Reed, and Alexandre Dumas, previously forbidden for teenagers - but everyone read this not only little nobles, but also every literate child from any cultured family.

Learn more