Recognizing emotions in others

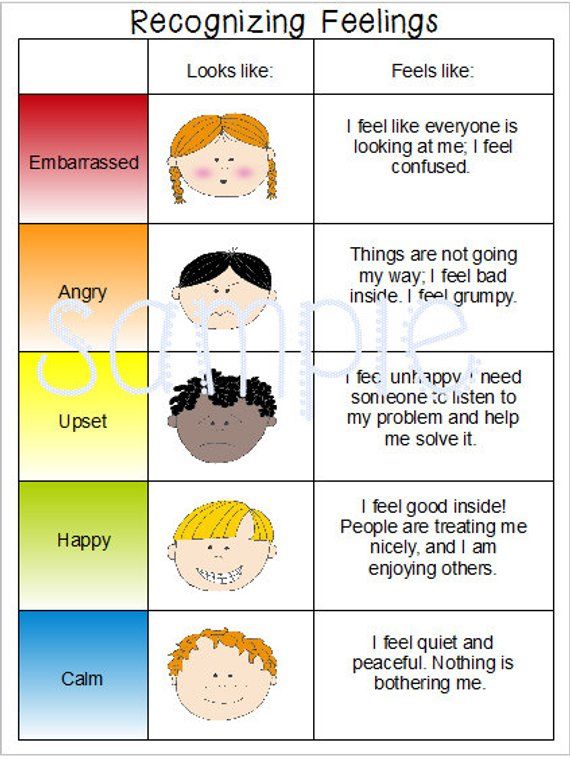

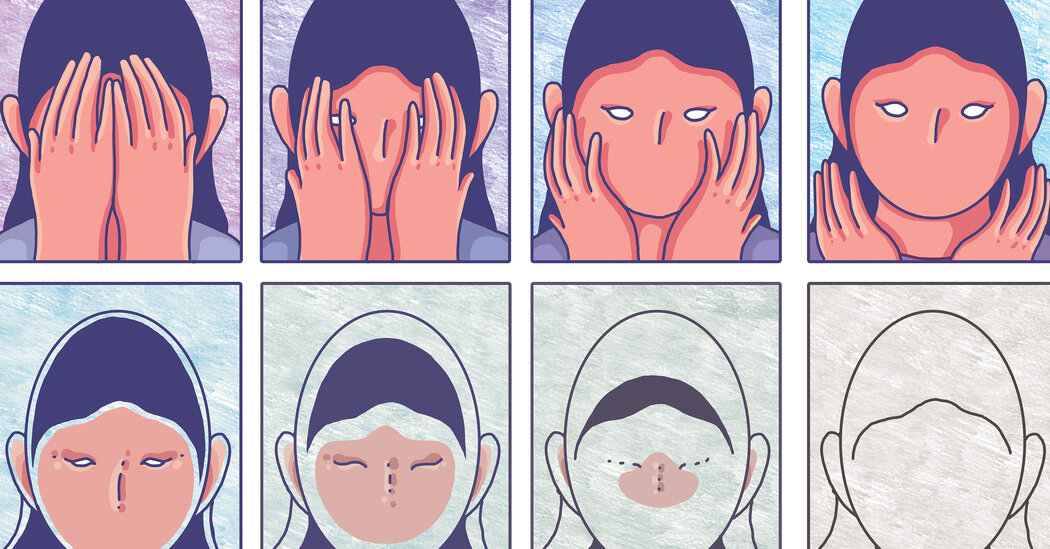

Social-Emotional Learning: Identifying Emotions in Others

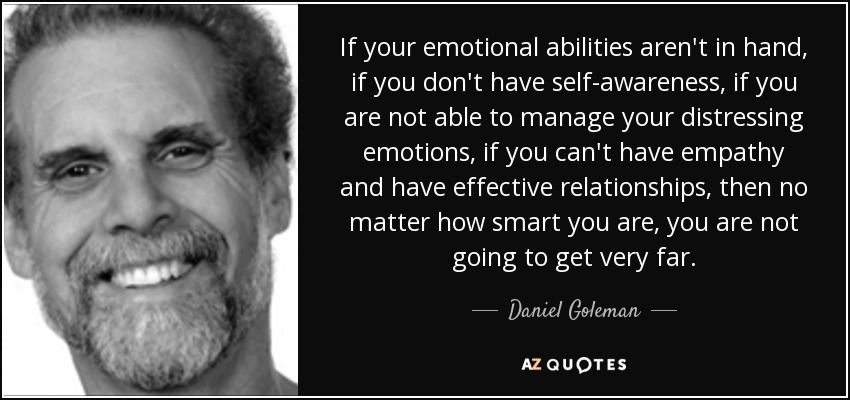

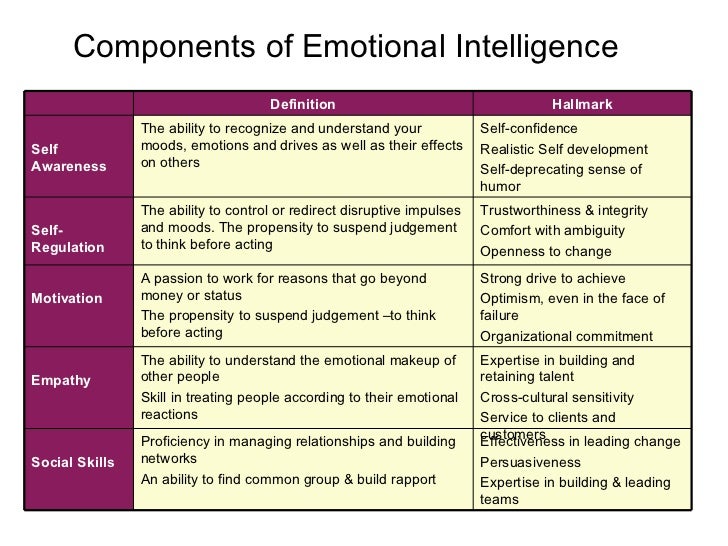

In a recent article, I focused on an essential aspect of EI (emotional intelligence): being able to accurately identify one’s emotions. This article addresses why and how to teach young people to attune to others’ emotional states.

Identifying and managing our own emotions is essential to our personal well-being and happiness. Accurately identifying others’ emotions is essential to our social well-being and happiness. The ability to pick up on others’ emotions helps us manage, communicate, and collaborate with them more effectively. Put simply, it enables us to get along better with people in general. The inability or non-conscious choice not to identify how people are feeling can easily lead to conflict and problems. When I was teaching middle school, I noticed this skill deficit in a number of my students. During my first year or two supervising the middle school cafeteria during lunch (I did this for eleven years), students who were the most challenging to manage were often those who didn’t accurately read other students’ emotions, or mine.

I remember when a particularly aggressive 7th grader who seemed to enjoy intimidating his peers, did not get the usual immediate compliance when he told a smaller boy to get out of his chair in the cafeteria: “Get outta my seat, runt.” It was obvious to me that the smaller boy, Sebastian, was paralyzed by fear and humiliation. When Sebastian didn’t move, Jason erupted. “Who do you think you are, you scrawny little wimp!” he shouted as he started to push him out of his chair. Talking to Jason afterwards, it became clear that he had misinterpreted Sebastian’s fear, erroneously perceiving it as a challenge. As Goleman writes in Emotional Intelligence, “Schoolyard bullies . . . often strike out in anger because they misinterpret neutral messages and expressions as hostile” (1995, p 271). I arranged for Jason to have lunch with me for the next week, during which I gave him some special tutoring in identifying feelings in others and self-control.

Because I worked on having a friendly (not buddy) relationship with students, some students misperceived me as being permissive. Therefore, sometimes when I addressed their inappropriate behavior, they would think I was “just kidding.” I occasionally had to say to them something like, “Look at my face. Listen to my voice. Hear my words. I am not kidding. Stop playing hacky sack on the stairs. Now.” While most students are pretty good at picking up on “the teacher look” (or voice), there are many who seem to be emotionally visually and hearing impaired. This unawareness of others’ feeling states can have a wide range of unfortunate and unintended consequences, from getting in trouble at school to damaging the important relationships in our lives.

Therefore, sometimes when I addressed their inappropriate behavior, they would think I was “just kidding.” I occasionally had to say to them something like, “Look at my face. Listen to my voice. Hear my words. I am not kidding. Stop playing hacky sack on the stairs. Now.” While most students are pretty good at picking up on “the teacher look” (or voice), there are many who seem to be emotionally visually and hearing impaired. This unawareness of others’ feeling states can have a wide range of unfortunate and unintended consequences, from getting in trouble at school to damaging the important relationships in our lives.

What follows are some meetings, activities, and resources to help students gain insight into others’ feelings and learn to attune their behavior to them.

Class Meeting: You can use class meetings to introduce the topic of “Identifying Emotions in Others.” I encourage you to have the students sit in a circle and use a Kooshball, talking stick, or other device to designate the speaker. I typically use the “Define, Personalize, Challenge” format for the discussion prompts.

I typically use the “Define, Personalize, Challenge” format for the discussion prompts.

Define:

Today we’re going to discuss the importance of being able to identify emotions in others. I don’t think we have any terms that need to be defined, but we might need to consider whose feelings it would be important to identify and where it is important to identify emotions.

1) Whose emotions would it be important to identify and why?

2) Why would it be important to identify people’s feelings at home? At school? At work?

3) Where else might it be useful to identify emotions?

Personalize:

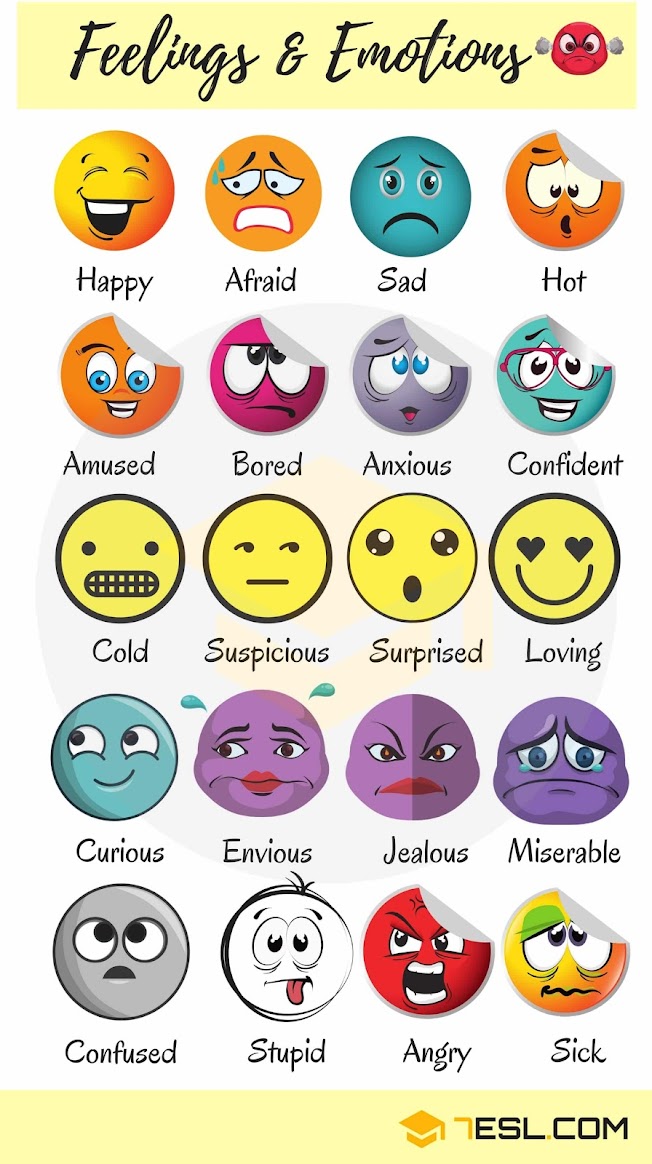

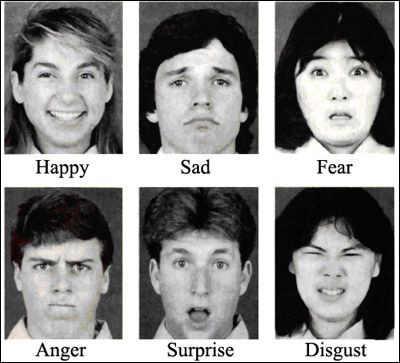

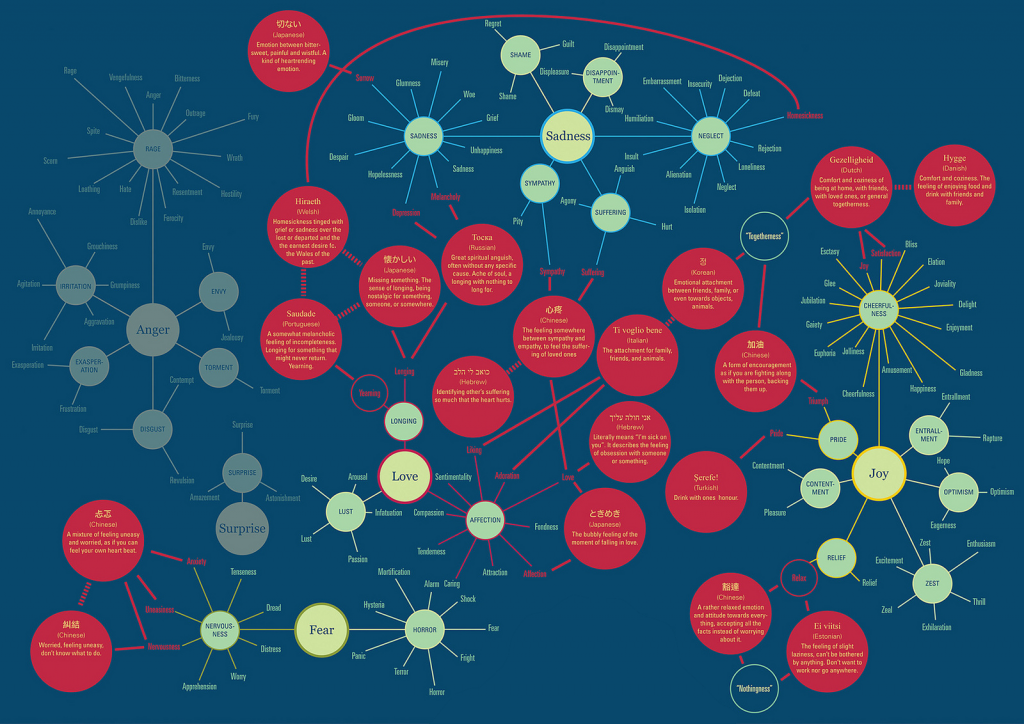

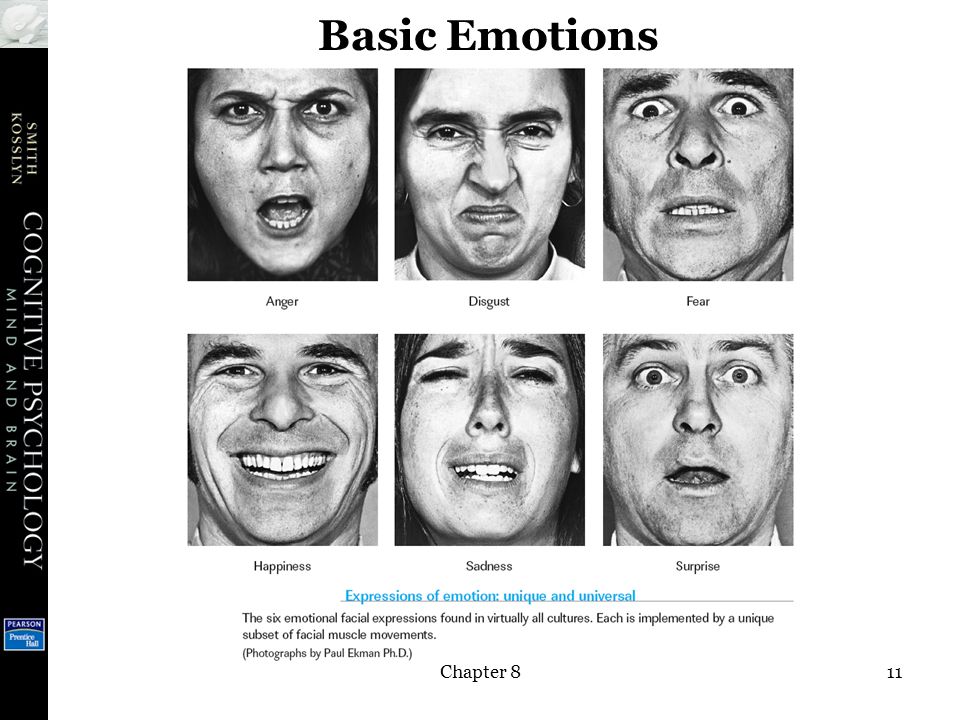

1) Let’s take the primary emotions: love, anger, fear, sadness, and joy. How would someone know when you are feeling those feelings? What does your face look like? What does your body (posture, gestures, etc.) look like? (Take each of these emotions and have students discuss, show, and model them). If you have a drama department at your school, see if you can get some students to come to class or create a video demonstrating facial expressions of various emotions.

2) Can we always read someone’s emotions from their face or body language?

3) Are there times you put on a “social mask,” so to speak and try to hide your feelings? Why?

4) When you are feeling _________, what kind of behavior do you want or need from others?

Challenge:

1) How can we use what we’ve discussed today about identifying others’ emotions?

2) How might what we discussed today benefit you?

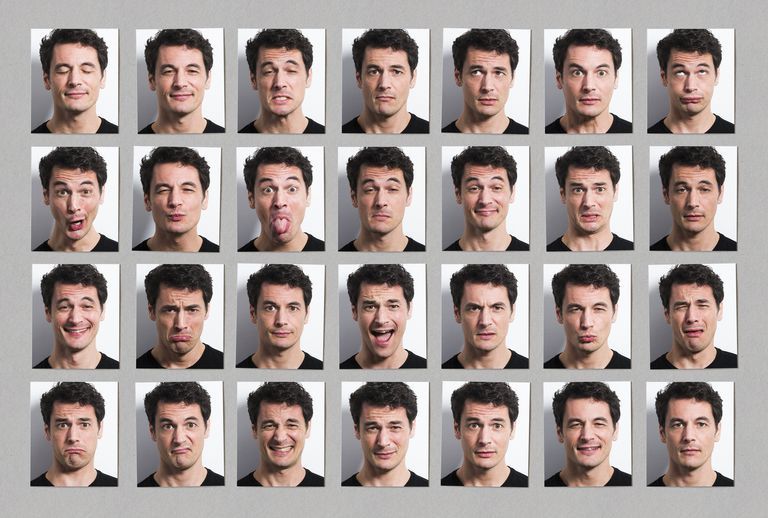

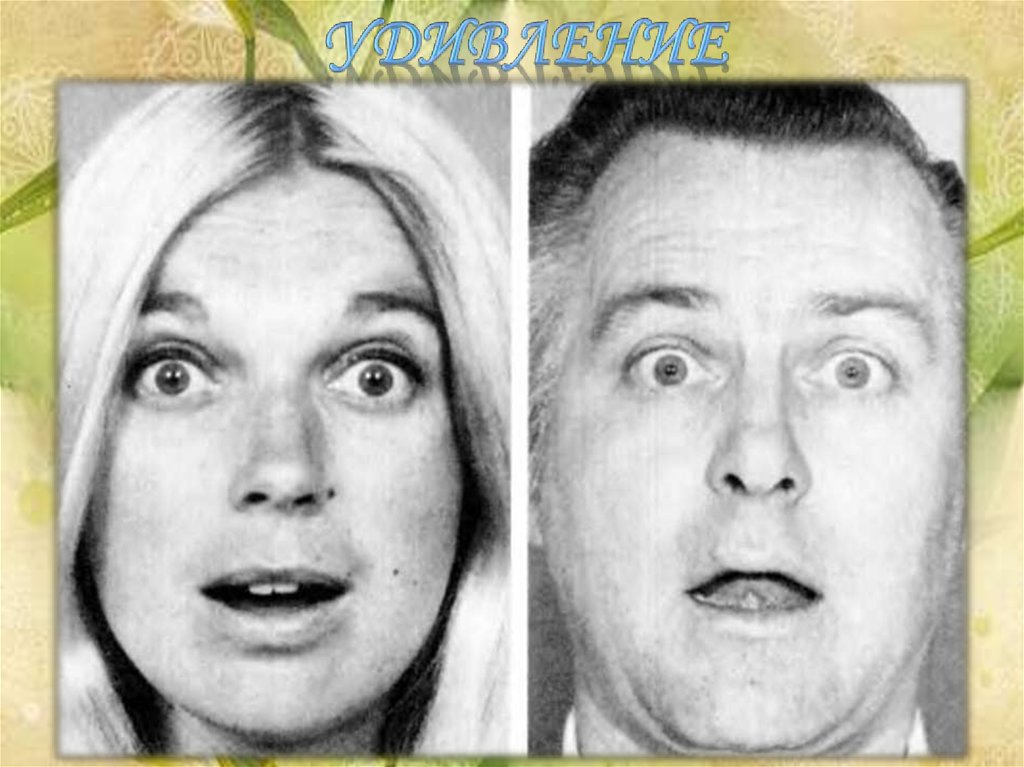

Direct Instruction: You might want to show your students some examples of the primary facial expressions. I suggest you visit DataFace. Click on the “Emotions” tab, go to the bottom of the page, and click on “Emotion Expressions” at the bottom of the page and you will learn the general characteristics of each expression.

Practice Identifying Facial Expressions

The Feeling Game: For younger students or students who have a greater need for identifying emotions from facial expressions, there are several website dedicated to helping them. One is www.Do2Learn.com. Here children can practice identifying facial expressions and receive immediate feedback.

One is www.Do2Learn.com. Here children can practice identifying facial expressions and receive immediate feedback.

Feeling Flashcards: Go to www.mes-english.com/flashcard. Download feeling flashcards to help your elementary students practice. You might try using the Inside-Outside Circle structure, students swapping cards after each drill.

Create your own Feelings Match Game: This game can be used with any age group.

1. Materials: Invite your students to bring in magazines from home. The more variety the better; news magazines, sports, health, music, etc. Cut out or have students cut out pictures of people (trying to avoid including the setting the picture was taken in) expressing a variety of emotions. Matte the pictures and laminate them, if possible. Then create a simple playing area by printing the following emotions on card stock and spreading them out on a table top for a small group, or on the floor in the center of a class meeting: Joy, Anger, Sadness, Fear, Surprise, and Love.

2. Procedure: Individually (or in small groups) students discuss each facial expression and place it near the emotion they think it best fits. Older students might be encouraged to identify the secondary or tertiary emotion expressed. Then the class should share and discuss their answers. What is it about the facial expression that suggests that emotion? Is there any body language involved? What strength, on a scale of one to ten, is the person feeling this emotion? Is there another name for that feeling?

Other Non-Verbal Messages:

Body Language

Direct Instruction: Explain that only a small percentage of the messages we send when we interact with others is through the words we choose. Our facial expressions say a lot. So do our bodies – through posture and gestures. Demonstrate, or have students or another adult you’ve rehearsed with, show posture and gestures communicate messages by non-verbally showing:

Sadness Fear

Excitement Contentment

Anger Confidence

Impatience Exhaustion

Illness Confusion

Acting 101:

As a large group, have students demonstrate, using only their facial expressionand gestures, the feelings or moods you call out. Call out each of the following (or others) and give them some time to act out the emotion or mood:

Call out each of the following (or others) and give them some time to act out the emotion or mood:

· Happy

· Sad

· Scared

· Angry

· Impatient

· Proud

· Worried

· Frustrated

· Puzzled

· Thrilled

· Exhausted

· Etc.

Variation: Give individual students cards with emotions listed on them. Have them act out the emotion for 10 seconds. (Tell the audience not to blurt out the emotion,) After the time is up or the actor is through, ask students, “What emotion ____ is expressing?” and “What gave it away.”

Variation 2: For younger students, give each student a set of index cards with the primary emotions – Joy, Anger, Sadness, Fear, Surprise, and Love – one emotion per card. Act out an emotion for up to 10 seconds, then say, “What’s my emotion?” and have the students hold up the card with the emotion they think you are expressing. Again, ask them what gave it away.

Proximity:

Another aspect of non-verbal communication is proximity, the distance one person is from another during a conversation. You might hold a class meeting about proximity, in which you do some direct instruction as you go.

Class Meeting: “Proximity”

Define:

1. Explain that proximity is the distance between people in different situations.

2. Do different situations call for different proximity? Can you give some examples? (Their answers might include: friends are more comfortable being closer than acquaintances; people at a crowded concert of movie theater are more comfortable being close than people in a restaurant; girls are more comfortable being close than boys, except in contact sports; informal social conversation is comfortable at a greater distance than an intimate conversation between good friends or a couple.)

Personalize:

1. Have you ever been in a conversation where you felt uncomfortable because the person you were talking to was too close? Too far away? (You might bring up the close-talker segment of Seinfeld, if students remember the show. )

)

2. How might proximity affect the way you perceive someone’s emotions or intentions?

Challenge:

1. What do you think is a good rule of thumb is for conversational proximity? (In America and northern Europe, about an arm’s length is generally considered comfortable for friendly acquaintances. You might mention that in other cultures, closer or more distant proximity may be the norm. If you have students from other cultures, ask them to share their perceptions of proximity.)

Tone of Voice:

Direct Instruction: Explain how important tone of voice is to communication. Demonstrate this by using the same phrase and achieving several different meanings simply by changing your tone of voice. You might use the phrase, “I really love riding my brother’s bike to school in the rain.” Say it:

1) Sincerely

2) Sarcastically

o With the accent on “love.”

o With the accent on “school.”

o With the accent on ”in the rain.”

3) Enthusiastically

o With the accent on “really love. ”

”

o With the accent on “my brother’s.

o With the accent on “in the rain.”

4) As a question

5) With no energy at all.

6) Any other way you can change the meaning.

Discuss all the variations of meaning that can come from the same 12 words. You might have students try it with a partner, using the phrase, “I really like watching news on TV.”

Ask a few talented actors to demonstrate the different meanings they can achieve through tone of voice alone.

These activities are fun for most children and adolescents, they build positive relationships between you and the young people you spend time with, and they improve relationships among the kids themselves. While these benefits are important, if the discussions and activities above are not integrated into the classroom, family, or group on an ongoing and intentional basis, their full potential will not become reality. Think about how emotional and social intelligence can become an ongoing theme in your classroom, organization, or home. Discussions, curriculum, and projects can almost always be based on or integrate a human emotional dimension. Over time, taking feelings into consideration in every interaction becomes a habit. And all the benefits that accompany being a considerate person, ranging from an increased sense of self-worth to improved human relationships, become a reality.

Discussions, curriculum, and projects can almost always be based on or integrate a human emotional dimension. Over time, taking feelings into consideration in every interaction becomes a habit. And all the benefits that accompany being a considerate person, ranging from an increased sense of self-worth to improved human relationships, become a reality.

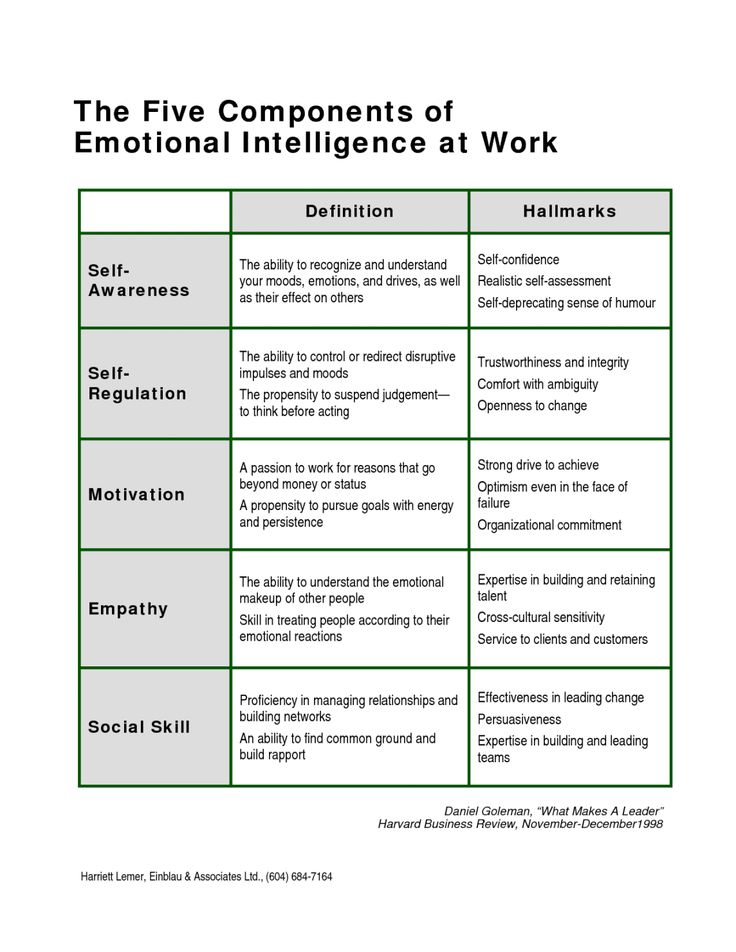

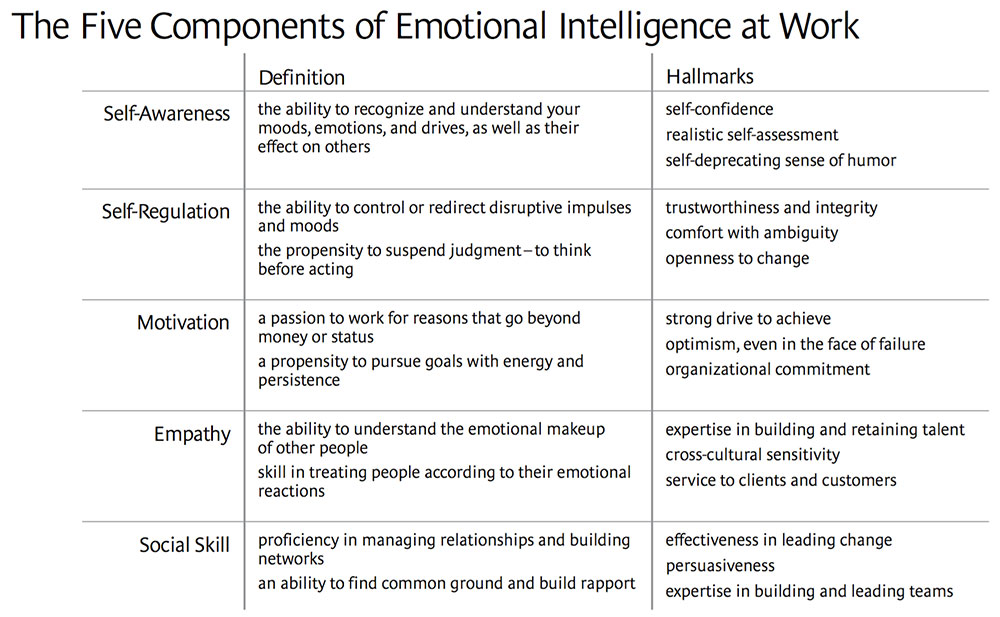

Great Leaders Recognize Others' Emotions

Great Leaders Recognize Others’ Emotions

“When dealing with people, remember that you are not dealing with creatures of logic, but with creatures of emotion”

Dale Carnegie

How many times a day do you ask a coworker how they’re doing, only to hear a standard “fine”? Do you tend to follow up their response with another question? Many leaders ask others at work about their emotions without really considering how important it is to be in touch with their moods. It may be a good idea to start paying more attention to how your coworkers feel, as leaders who pay close attention to others’ emotions are less likely to experience career derailment and more likely to be viewed as transformational leaders. 1

1

Leaders who can accurately recognize others’ emotions are closely attuned to the emotional environment of their workplace and can better sense changes in their direct reports’ motivation or in clients’ level of satisfaction. Those who have good emotional recognition closely attend to others’ nonverbal emotional cues (e.g., facial expressions and body language) to identify others’ feelings. Workers who are better at recognizing emotions in others have a heightened understanding of social dynamics at work, which may facilitate more cooperation with coworkers, and in turn, higher annual salary.2

In assessing your ability to recognize others’ emotions effectively, ask yourself the following questions:

- Am I comfortable talking about emotions at work?

- Do I regularly check in with my colleagues to see how they are feeling?

- When someone is talking to me, do I pay attention to their body language?

- Do I ask people what they are feeling when I’m unsure?

Improve Your Emotion Recognition Skills

Accept different comfort levels: Some leaders avoid talking about emotions at work, as emotions could seem too personal for a professional context. However, discussing emotions can help direct reports feel comfortable bringing their authentic selves to work, and can help leaders understand how to support their team (e.g., delegating work for a stressed direct report). Ongoing conversations about positive and negative feelings can increase motivation and improve working relationships. Just remember that not everyone feels comfortable sharing their emotions at work, especially with their leaders. It is important to be respectful of what others are willing to share, and to acknowledge that this may look different for everyone.

However, discussing emotions can help direct reports feel comfortable bringing their authentic selves to work, and can help leaders understand how to support their team (e.g., delegating work for a stressed direct report). Ongoing conversations about positive and negative feelings can increase motivation and improve working relationships. Just remember that not everyone feels comfortable sharing their emotions at work, especially with their leaders. It is important to be respectful of what others are willing to share, and to acknowledge that this may look different for everyone.

Build trust: Others will feel more comfortable opening up to you about how they feel if they trust you. One way of building trust is by noticing how you’re feeling and sharing your own emotions with others. When you share more details about your own thoughts and feelings, your colleagues are more likely to feel compelled to share their own feelings. In addition, keeping these conversations confidential and having the other person’s best interests at heart are essential for building trust.

Use communication tools thoughtfully: Remote work is becoming increasingly popular, and with it comes many new methods of communication (e.g., instant messages and video calls). Be sure to use communication tools that align with the purpose of your conversations. For difficult or sensitive conversations, where recognizing others’ emotions is important, suggest a face-to-face or video call where you can read nuanced nonverbal expressions. However, for less formal conversations where there is little room for misunderstanding, audio- or text-only methods are likely to be sufficient.

Improve Your Emotion Recognition Skills

The following steps can help you become better at recognizing the emotions of others:

- Start with media and those closest to you. It can be easier to identify emotions in the media you consume, as well as in people who you already feel close to. Make it a goal to pay more attention to the expressions of others in television shows or movies, and close coworkers or family members in conversations.

Note their facial expressions, gestures, and posture. Using these clues, try to make guesses about how they are feeling. For example, if you notice your coworker is not participating in a meeting and has visibly slumped shoulders, you can guess at whether they may be feeling unsatisfied with their work or are tired from poor sleep.

Note their facial expressions, gestures, and posture. Using these clues, try to make guesses about how they are feeling. For example, if you notice your coworker is not participating in a meeting and has visibly slumped shoulders, you can guess at whether they may be feeling unsatisfied with their work or are tired from poor sleep.

. - Focus on tone. In addition to watching someone’s body language to identify their emotions, try to pay attention to the sound of their voice.3 Although people may try to conceal their emotions in the words they speak (e.g., saying “I’m fine with it”), their tone of voice can provide clues about how they are really feeling. In a face-to-face conversation, you can gaze briefly at a distant object and focus solely on the sound of your conversation partner’s voice. See if you can describe their tone with words like “tight, high, calm, trembling, playful, or sarcastic.”

. - Test your assumptions. Our information about someone else’s internal feelings is never perfect, so it’s a good idea to double-check your initial guess about how someone is feeling with them.

You can ask them a question, such as “How is it going for you?”, or “How can I support you?”. Try to leave your questions open-ended so that you are not making assumptions about how they feel, and they can fully share what is on their mind. If you cannot directly ask the person who spoke about how they felt, try to ask another observer for their impressions.

You can ask them a question, such as “How is it going for you?”, or “How can I support you?”. Try to leave your questions open-ended so that you are not making assumptions about how they feel, and they can fully share what is on their mind. If you cannot directly ask the person who spoke about how they felt, try to ask another observer for their impressions.

Resources

WATCH: 5 Warning Signs Your Star Performer is Burned Out

READ: All the Feels: Why It Pays to Acknowledge Emotions in the Workplace

DEVELOP: Develop your ability to recognize others’ emotions by taking advantage of SIGMA’s coaching services

Interested in a hard copy of this handout? Download your PDF copy of our EI Series Handout

Download the PDF Guide

Contact

Contact SIGMA for coaching on developing your skills as a leader.

SIGMA Assessment Systems, Inc.

Email: [email protected]

Call: 800-265-1285

1 Rubin, R. S., Munz, D. C., & Bommer, W. H. (2005). Leading from within: The effects of emotion recognition and personality on transformational leadership behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 845-858.

H. (2005). Leading from within: The effects of emotion recognition and personality on transformational leadership behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 845-858.

2 Momm, T., Blickle, G., Liu, Y., Wihler, A., Kholin, M., & Menges, J. I. (2014). It pays to have an eye for emotions: Emotion recognition ability indirectly predicts annual income. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1), 147-163.

3 Kraus, M. W. (2017). Voice-only communication enhances empathic accuracy. American Psychologist, 72(7), 644–654.

biases and distortions - Monoclair

Headings : Neuroscience, Latest articles, Psychology

Did you find something useful here? Help us stay free, independent and free with any donation:

Donate

Scientists on how our prejudices distort the perception of reality and others, and why emotion recognition is not our forte.

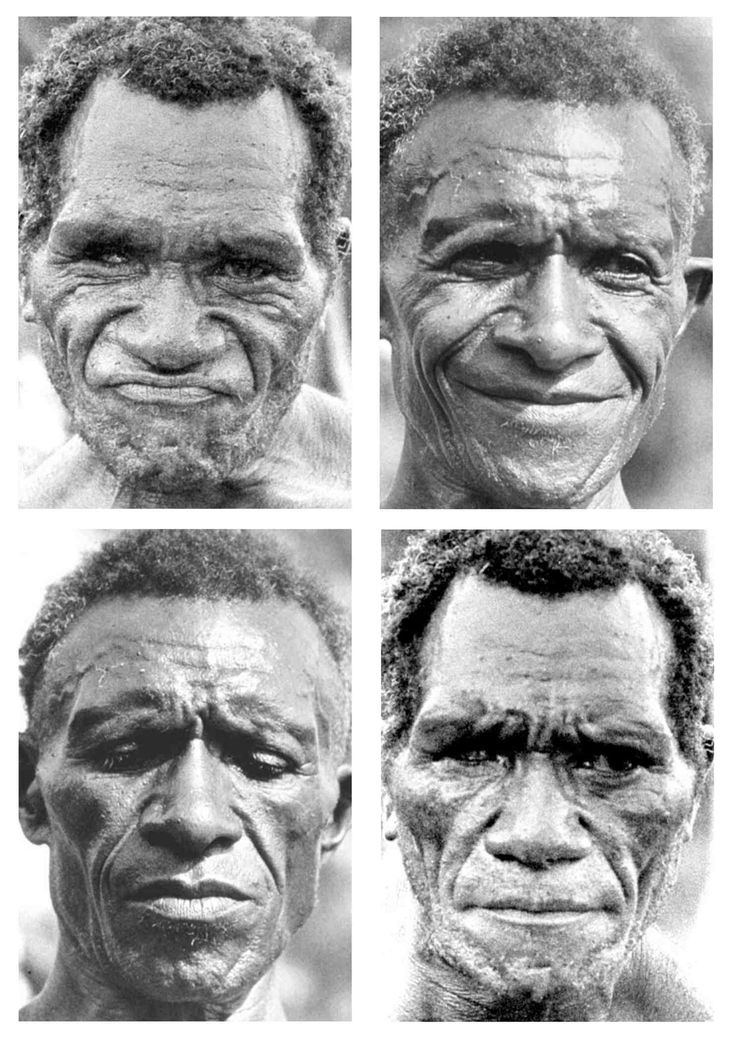

Do you remember the Soviet science fiction “I and Others”, in which we were shown a series of experiments proving how suggestible we are, not independent in our judgments and dependent on the opinions of others? In one of the tests, the participants were shown a portrait of the same person, first imagining him as a scientist or a murderer, after which the respondents had to draw up a psychological portrait of the person they presented. Of course, those who described the "killer" noticed the cruelty in the eyes, and the sly grin, and secrecy. Those who described the prominent scientist saw kindness, decency, intelligence in the same portrait. But is it really only a matter of a person's suggestibility and natural tendency to conformity (they said a murderer means a murderer)?

Of course, those who described the "killer" noticed the cruelty in the eyes, and the sly grin, and secrecy. Those who described the prominent scientist saw kindness, decency, intelligence in the same portrait. But is it really only a matter of a person's suggestibility and natural tendency to conformity (they said a murderer means a murderer)?

There is another study conducted by scientists from the US, New Zealand and France already in the 2000s, which confirms the hypothesis that our initial impression of the emotions of other people distorts our subsequent perception of their facial expressions and memory of it.

That is, as soon as we interpret an ambiguous or neutral look as anger or joy, we subsequently remember or actually see this particular emotion.

As study co-author Petr Winkelman, professor of psychology at the University of California, points out, their paper poses a “good old question”:

"Do we see reality as it is, or is what we see a result of our preconceptions?"

According to him, the results do confirm that what we think has a noticeable effect on our perception, and the recognition of human emotions becomes biased. Another study co-author, Jamin Halberstadt of the University of Otago in New Zealand, explains:

“We imagine that our expression of emotions is an unambiguous way of communicating and conveying feelings. But in real social interaction, a facial expression is a mixture of several emotions - and it is open to interpretation. This means that two people may have different memories of the same emotionally charged episode, but both may be right about what they "saw". So when my wife perceives my smirk as cynicism, she is right: her explanation of my facial expression at a certain point distorts her perception.

But it's also true that if she had explained my expression as empathy, I wouldn't have had to sleep on the couch. It's a paradox - the more we look for meaning in the emotions of others, the less accurately we remember them.

The researchers note that the phenomenon under study goes far beyond everyday interpersonal misunderstandings—especially among those with persistent or dysfunctional ways of understanding emotions—for example, people with anxiety disorder or those with psychological trauma.

For example, anxious people have a negative interpretation of other people's reactions, which can permanently color their perceptions of feelings and intentions and perpetuate their erroneous beliefs even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

Another area in which the results of the study could be applied is in eyewitness memory: a witness to a violent crime, for example, may attribute malice to the perpetrator, an impression that the researchers believe will influence the memory of the perpetrator's facial expression.

During the experiment, the researchers showed participants digitally processed photographs of faces that reflected ambiguous emotions and asked the respondents to think of these faces as angry or happy.

Participants then watched the facial expressions slowly change from angry to happy and had to find the photo they had originally seen.

People's initial interpretations affected their memories: faces initially interpreted as angry were more often recalled as angry than faces initially interpreted as happy.

Scientists were particularly interested in the fact that faces with a vague facial expression were perceived so ambiguously and caused such different reactions. By measuring subtle electrical signals from the muscles that control facial expressions, the researchers found that participants mimicked previously interpreted emotions on their faces when re-viewing faces with vague expressions.

In other words, when looking at a face that they once thought was evil, people were more likely to express angry emotions on their faces than people who looked at the same face but initially interpreted it as joyful.

As the researchers note, these are largely automatic processes - such mimicry reflects how people perceived a face with an ambiguous expression, and demonstrates that participants literally saw different expressions. Professor Winkelman of the University of California notes:

“In this way, we were able to discover that our body is an interface: a place where thoughts and perceptions meet. Our research supports the emerging field of "embodied consciousness" and "embodied emotion" research. And our bodily self is intimately intertwined with how and what we think and feel.”

See also

— How do emotions arise that we are unaware of?

— The nature of emotions: innate reactions or acquired constructs depending on the situation?

Adapted from: Halberstadt, J., Winkielman, P., Niedenthal, P. M., & Dalle, N. (2009). Emotional conception: How embodied emotion concepts guide perception and facial action. Psychological Science, 20, 1254-1261

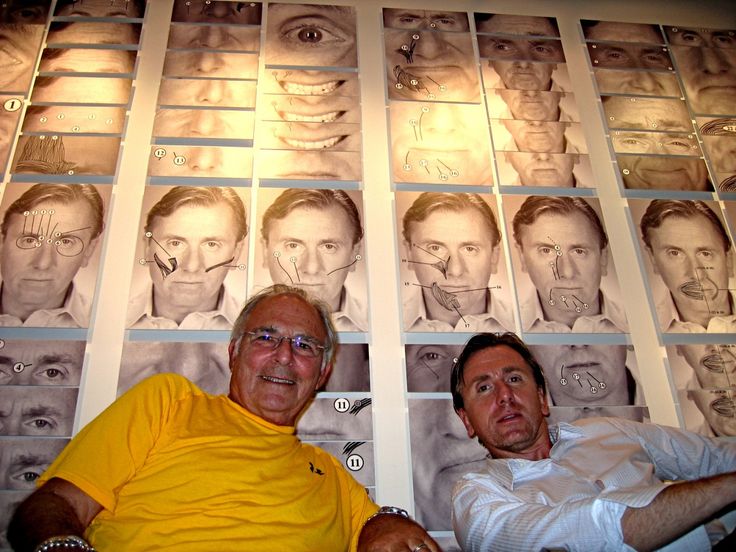

Cover: Guillaume Duchene with a subject during an experiment on facial muscle contractions

If you find an error, please highlight the text and press Ctrl+Enter .

research neuroscience emotions

similar articles

90,000 of emotions recognition of illegal actions of sexual nature - Psychology and LawRaising Psychic Psychot patients during compulsory treatment (PL) is possible due to profiling and individualization of programs of medical and rehabilitation measures. Need a closer psychological study of persons who have committed sexual OOD, located on the submarine, due to the fact that their number in hospitals This type of treatment ranges from 5 to 10%.

Note that specific forms already exist psychotherapeutic work in relation to persons who have committed sexual OOD [1]. This does not exclude the expediency of participation of this category of patients in other forms of rehabilitation work - trainings.

Sex offenders have specific personality characteristics, related both to the sphere of gender-role self-awareness, and to the features interpersonal interaction. Defective are social communicative skills, partnerships, empathy, predictive abilities behavior of another person [8]. Choice and attitude towards the sexual object attraction in individuals with various forms of sexual preference disorders also determined by specific disorders and distortions of emotional perception of a sexual partner[1].

expression, and from the posture of a person is an actual scientific and practical task aimed at solving problems of forecasting and prevention of repeated sexual OOD in persons with deviant behavior and without it.

The purpose of the study is to study the role of the ability to recognize emotions in persons who have committed sexual delicts in the genesis of illegal behavior for development of differentiated measures for the prevention of repeated OOD.

Research objectives

- Theoretical analysis of the problem of studying the perception of emotions in persons with conditional normal and in psychiatric disorders.

- Creation of new methodological tools for studying features emotional intelligence and its component - recognition of emotions with differentiation of stimulus material both by age and gender signs.

- Identification of normal-age patterns of emotion recognition in individuals with prosocial behavior and without sexual preference disorders.

- Comparative analysis of features of emotion recognition in individuals who committed sexual OOD, with a conditional norm.

- Determination of the relationship of features of emotion recognition and other structural components of emotional intelligence.

Study material

Empirical . In the first part of the pilot study, 96 students of secondary school No. 868 of Moscow were examined, of which 43 aged 11, 24 aged 14 and 29at the age of 16. Experiment consisted of two submissions. In the first, the subjects, in accordance with the specified the researcher in the order of emotions had to arrange the photographs in order each of the 6 people. In fact, this task was to recognize emotions. Then the cards were shuffled, and in the second presentation they were asked to put them in one group all people expressing the same emotion, which is very similar to the task on classification.

Experiment consisted of two submissions. In the first, the subjects, in accordance with the specified the researcher in the order of emotions had to arrange the photographs in order each of the 6 people. In fact, this task was to recognize emotions. Then the cards were shuffled, and in the second presentation they were asked to put them in one group all people expressing the same emotion, which is very similar to the task on classification.

80 people took part in the second part of the study, 30 of them − experimental group, which included 21 people who were on compulsory treatment in the Oryol PBSTIN and committed unlawful acts of a sexual nature, and 9people who committed sexual OOD, who were on an outpatient examination at the Federal State Institution “GNTSSSP named after A.I. V. P. Serbsky Ministry of Health and Social Development".

In the experimental group there were subjects who committed aggressive and violent acts of a sexual nature against women and children. The group of subjects who committed sexual OOD included subjects with paranoid schizophrenia - 15 people, with moderate mental retardation - 9 a person with a personality disorder due to mixed illnesses - three, with oligophrenia in the degree of debility - one, with a psychotic disorder, due to brain damage - two. Of these, persons who have committed violent acts of a sexual nature against women - 14; face, sexually assaulted children (pedophilia) - 9, of which - violent acts of a sexual nature in for girls - six, for boys - one.

The group of subjects who committed sexual OOD included subjects with paranoid schizophrenia - 15 people, with moderate mental retardation - 9 a person with a personality disorder due to mixed illnesses - three, with oligophrenia in the degree of debility - one, with a psychotic disorder, due to brain damage - two. Of these, persons who have committed violent acts of a sexual nature against women - 14; face, sexually assaulted children (pedophilia) - 9, of which - violent acts of a sexual nature in for girls - six, for boys - one.

The age of the subjects is from 23 to 61 years. By qualification of crimes: 3 person - Art. 105, 131 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation; 26 people - art. 131 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation; 1 person - Art. 119 131 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

The control group consisted of 50 people with normal behavior. The age of the examined is from 25 to 50 years.

The methodological complex included: a method for determining the level of emotional intellect N. Hall; method for diagnosing the level of empathy I. M. Yusupova; a technique for recognizing emotions (V. G. Bulygina, A. A. Makurin, 2009) [1] ; method for recognizing emotions by posture human (V. G. Bulygina, A. A. Makurin, 2010). Methodology on emotion recognition is designed to detect a person's ability to read emotions with facial expressions. Technique for recognizing emotions by posture of a person is designed to identify a person's ability to read emotions from position of the body in space. The artist schematically depicted poses of a person, reflecting 8 emotional states: pride, joy, anger, shame, sadness, fear, love, hate.

Hall; method for diagnosing the level of empathy I. M. Yusupova; a technique for recognizing emotions (V. G. Bulygina, A. A. Makurin, 2009) [1] ; method for recognizing emotions by posture human (V. G. Bulygina, A. A. Makurin, 2010). Methodology on emotion recognition is designed to detect a person's ability to read emotions with facial expressions. Technique for recognizing emotions by posture of a person is designed to identify a person's ability to read emotions from position of the body in space. The artist schematically depicted poses of a person, reflecting 8 emotional states: pride, joy, anger, shame, sadness, fear, love, hate.

Statistical data processing was carried out using statistical SPSS Statistics 17.0 software (frequency analysis, contingency tables, non-parametric variation statistics U - Mann-Whitney test, hierarchical cluster analysis, analysis of variance, one-way and correlation analysis). Graphic images were built in the program Excel.

Discussion of results

prepubertal period are better recognized (at the level of statistical significance) peer emotions. However, positively colored emotions like love, joy, older subjects learn better, regardless of the age of the depicted in the picture of people. An interesting fact was that the youngest children in surveyed sample recognize "anger", "hatred" and "shame" statistically significantly better than other subjects when presenting cards with faces of peers and young people. And at the same time, they recognize the same emotions in the faces of older people much worse. age.

In the second part of the experiment, it was found that when recognizing an emotion sadness for all presentations, there are differences between the control and experimental groups. At the same time, data on the recognition of sadness without taking into account grouping factors (boy-girl, boy-girl, man-woman) show identical percentages of errors and correct answers in both groups. However, taking into account grouping factors (boy-sadness (33%), girl-sadness (20%), sadness boy (73%), sadness girl (83%), sadness woman (13%), male sadness (46%)), the experimental group recognizes the emotion of sadness worse, than the control group ((boy-sadness (62%), girl-sadness (44%), sadness boy (86%), sadness girl (98%) female sadness (38%), sadness man (74%)).

However, taking into account grouping factors (boy-sadness (33%), girl-sadness (20%), sadness boy (73%), sadness girl (83%), sadness woman (13%), male sadness (46%)), the experimental group recognizes the emotion of sadness worse, than the control group ((boy-sadness (62%), girl-sadness (44%), sadness boy (86%), sadness girl (98%) female sadness (38%), sadness man (74%)).

When comparing significant differences by age, it was found that that the emotions of anger and sadness are better recognized in a girl and a boy, hatred in girls and boys, pride and sadness - in a man and a woman.

Sexual perpetrators have the most pronounced difficulties in recognizing the expression of emotions in adult males. Maximum the number of errors was recorded in the identification of emotions love, hatred, anger, sadness. Specific to perpetrators of sexual OOD, is the inability to correctly identify an emotion such as anger.

When recognizing children's emotions, anger and sadness are significantly worse, additionally, in relation to male children, emotion is less recognized shame.

In the experimental group, there are significant relationships between recognition positive and negative emotions (love-hate, joy-anger, joy-fear), normally such a connection is not traced. For this category of people better guess only positive emotions or only negative emotions, in this case, pairs of recognitions are organized, different from what is observed in norm.

Persons who have committed sexual delicts also have “adequate” connections, however, they are observed only when negative emotions are recognized (anger−hatred, sadness−hatred, anger−shame). Correlations between unimodal variables in recognizing positive emotions are traced only when presentation of images of a boy (joy-love).

In adult male emotion recognition, factors include multimodal emotions, among which pride and fear, anger and hatred, which may indicate an incorrect attribution of traits, that the average man should have.

For perpetrators of sexual OOD, emotions such as sadness, hatred, fear, shame in the perception of women are the most significant and at the same time are misinterpreted. The next important factor in recognizing emotions women for this category of persons is joy and love, while love is a less recognizable (correctly identified) emotion.

The next important factor in recognizing emotions women for this category of persons is joy and love, while love is a less recognizable (correctly identified) emotion.

Significant differences in the perception of emotions by posture of a person between persons who have committed sexual OOD, and persons with normative behavior do not discovered. At the same time, according to the frequency analysis, a decrease in the accuracy of emotion recognition in individuals who have committed OOD.

The experimental group showed statistically significant relationships between the following variables: fear-shame. This indicates that this the group is better at recognizing the emotion of fear and shame.

In the structure of emotional intelligence in persons who have committed sexual OOD, the emotions of other people are significantly worse recognized. The ability to empathize experiences in relation to the elderly and strangers is significantly lower than in persons with normal behavior.

In the control group, a positive contribution to the total empathy score the following variables: empathy for parents, for animals, for the elderly, children, heroes of fiction and strangers and high values variable is the recognition of other people's emotions. At the same time, empathy for children positively associated with empathy for parents, the elderly, and animals. Empathy towards strangers is positively associated with empathy for children. Recognition other people's emotions are positively related to emotional awareness and empathy for strangers.

The results obtained confirm the earlier views that sexual aggression towards women is formed in the process of male sexual socialization as a combination of rejection of femininity (and women as its embodiment) and reduced capacity for empathy and need for intimacy with others [7].

Identified in the present study, the deficiency of emotion recognition in perpetrators of sexual OOD suggests that one of its reasons for the lack of experience of emotional interaction in the family. Modern studies have found a link between a child's ability to recognize emotions and his experience of emotional interaction in the family (involvement in close relationship with one of the parents, the emotional background of the relationship between the mother and child, the intensity and severity of the emotional manifestations of the mother).

Modern studies have found a link between a child's ability to recognize emotions and his experience of emotional interaction in the family (involvement in close relationship with one of the parents, the emotional background of the relationship between the mother and child, the intensity and severity of the emotional manifestations of the mother).

In addition, male gender norms force males at an early stage ontogenesis to dismiss as "feminine" a wide range of characteristics that are universal: for example, the manifestation of emotional states fear, helplessness, vulnerability. Rejection of these emotions and intense emotional state in general determines the relative impoverishment of their emotional experience. In turn, this leads to a reduction in the need for intimacy with other people, because intimate communication tends to cause only intense emotional states that they fear and reject. Tem moreover, understanding the language of emotions requires not only knowledge of the general norms of expression emotions typical of the society. It also requires the ability and willingness analyze the specific language of the surrounding people and learn it.

It also requires the ability and willingness analyze the specific language of the surrounding people and learn it.

When implementing normative sexual behavior, the stage of emotion recognition is discrimination of the emotional state of another is a prerequisite for subsequent stages. The second stage, perspective assessment, involves interpreting emotional state that was "recognised" earlier. It is noted [9] that disruption of perspective assessment is essential for the realization of sexual aggressive behavior - rapists are not able to adequately understand the state of victims and therefore continue to attack. The third stage, empathy or emotional response, impaired in sexual abusers due to limited emotional repertoire. Finally, the fourth stage involves the choice act, action, based on the information obtained in the previous stages empathic process.

Returning to preventive and psycho-corrective tasks in relation to persons committed sexual OOD, revealed "defects" in the recognition of emotions in faces different age categories, taking into account gender differentiation, allow to recommend for them the training "Coping with anger" and the training of development communication skills. The purpose of anger management training is to teach patients with high levels of aggression or anger: recognizing emotions, controlling their emotions, managing them, ways to avoid escalating negative emotions. And the training of communication skills includes the development of skills not only verbal and non-verbal communication with the development of a wide register of techniques decoding own and partner's emotional state.

The purpose of anger management training is to teach patients with high levels of aggression or anger: recognizing emotions, controlling their emotions, managing them, ways to avoid escalating negative emotions. And the training of communication skills includes the development of skills not only verbal and non-verbal communication with the development of a wide register of techniques decoding own and partner's emotional state.

Conclusion

sexual aggression towards women is formed in the process of male sexual socialization as a combination of rejection of femininity (and women as its embodiment) and reduced capacity for empathy and need for intimacy with others [7].

Identified in the present study, the deficiency of emotion recognition in perpetrators of sexual OOD suggests that one of its reasons for the lack of experience of emotional interaction in the family.

Modern research has revealed a relationship between recognition success child of emotions and his experience of emotional interaction in the family (inclusion in a close relationship with one of the parents, emotional background relationship between mother and child, the intensity and severity of emotional manifestations of the mother).

In addition, male gender norms force males at an early stage ontogenesis to dismiss as "feminine" a wide range of characteristics that are universal: for example, the manifestation of emotional states fear, helplessness, vulnerability. Rejection of these emotions and intense emotional state in general determines the relative impoverishment of their emotional experience.

In turn, this leads to a decrease in the need for intimacy with others. people, because intimate intercourse tends to cause only intense emotional states they fear and reject. Especially since understanding the language of emotions requires not only knowledge of general norms for expressing emotions, typical of this society. It also requires the ability and willingness analyze the specific language of the surrounding people and learn it.

When implementing normative sexual behavior, the stage of recognizing emotions is discrimination of the emotional state of another is a prerequisite for subsequent stages.

The second stage, perspective assessment, involves interpreting the emotional state that was "recognised" earlier. It is noted [9] that the violation of the estimate perspective is essential to the realization of sexually aggressive behavior – perpetrators are not able to adequately understand the state of the victim and therefore continue to attack.

The third stage, empathy or emotional response, is disturbed in sexual abusers because of their limited emotional repertoire.

Finally, the fourth stage involves the choice of an act, action, based on the information received at the previous stages of the empathic process.

Returning to preventive tasks in relation to persons who committed sexual OOD, identified "defects" in the recognition of emotions in faces of various age categories, taking into account gender differentiation, allow us to recommend for them, the training "Coping with anger" and the training for the development of communicative skills.

The purpose of anger management training is to educate patients with high level of aggression or anger: recognizing emotions, controlling one's emotions, managing them, ways to avoid escalating negative emotions. training communication skills includes the development of skills not only verbal and non-verbal communication with the development of a wide register of decoding techniques own and partner emotional state.

Terminals

1. Normal age features of emotion recognition are:

- in the prepubertal period, better recognition of negative emotions in peers in combination with their poor recognition in adults;

- to the positive phase of puberty and adolescence positively colored emotions (as love, joy) are recognized better regardless of age the people in the picture.

2. For persons who committed sexual OOD, there are the most pronounced difficulties in recognizing expressions of emotions of children and women. Specific to persons who have committed sexual ood, is the inability to correctly identify an emotion anger.

Specific to persons who have committed sexual ood, is the inability to correctly identify an emotion anger.

3. For persons who committed sexual torts, “adequate” connections were also revealed, however they are observed only when recognizing negative emotions (anger − hatred, sadness-hatred, anger-shame). Correlations between unimodal variables at recognition of positive emotions can be traced only when presented images of a boy (joy − love).

4. Significant differences in the perception of emotions by the posture of a person between persons who have committed sexual OOD, and with normal behavior was not found.

5. In structure emotional intelligence in persons who have committed sexual OOD is significantly worse recognizing the emotions of others. The ability to empathize with attitude towards older people and strangers is significantly lower than among people with normative behaviour.

[1] Actors and people of other professions aged 20 to 55 were selected male and female, as well as children under the age of 10 years.