Red riding hood novel

Red Riding Hood by Sarah Blakley-Cartwright, David Leslie Johnson, Paperback

Red Riding Hood

By Blakley-Cartwright, Sarah

Poppy Copyright © 2011 Blakley-Cartwright, Sarah

All right reserved.

ISBN: 9780316176040

Part One

1

From the towering heights of the tree, the little girl could see everything. The sleepy village of Daggorhorn lay low in the bowl of the valley. From above, it looked like a faraway, foreign land. A place she knew nothing about, a place without spikes or barbs, a place where fear did not hover like an anxious parent.

Being this far up in the air made Valerie feel as if she could be someone else, too. She could be an animal: a hawk, chilly with self-survival, arrogant and apart.

Even at age seven, she knew that, somehow, she was different from the other villagers. She couldn’t help keeping them at a distance, even her friends, who were open and wonderful. Her older sister, Lucie, was the one person in the world to whom Valerie felt connected. She and Lucie were like the two vines that grew twisted together in the old song the elders of the village sang.

Lucie was the only one.

Valerie peered past her dangling bare feet and thought about why she had climbed up here. She wasn’t allowed to, of course, but that wasn’t it. And it wasn’t for the challenge of the climb, either—that had lost its thrill a year earlier, when she first reached the tallest branch and found nowhere left to go but the open sky.

She climbed up high because she couldn’t breathe down there, in the town. If she didn’t get out, the unhappiness would settle upon her, piling up like snow until she was buried beneath it. Up here in her tree, the air was cool on her face and she felt invincible. She never worried about falling; such a thing was not possible in this weightless universe.

“Valerie!”

Suzette’s voice sounded upward through the leaves, calling for her like a hand tugging Valerie back down to earth.

By the tone of her mother’s voice, Valerie knew it was time to go. Valerie pulled her knees up under her, rose to a crouch, and began her descent. Looking straight down, she could see the steeply pitched roof of Grandmother’s house, built right into the branches of the tree and covered in a thick shag of pine needles. The house was wedged in a flowering of branches as if it had lodged there during a storm. Valerie always wondered how it had gotten there, but she never asked, because something so wonderful should never be explained.

It was nearing winter, and the leaves had begun to loosen themselves from their branches, easing their autumn grasp. Some shuddered and fell free as Valerie moved down the tree. She had perched in the tree all afternoon, listening to the low murmur of women’s voices wafting up from below. It seemed like they were more cautious today, huskier than usual, as though the women were keeping secrets.

Nearing the lower branches that grazed the tree house roof, Valerie saw Grandmother float out onto the porch, her feet not visible beneath her dress. Grandmother was the most beautiful woman Valerie knew. She wore long layered skirts that swayed as she walked. If her right foot went forward, her silk skirt breezed to the left. Her ankles were delicate and lovely, like the tiny wooden dancer’s in Lucie’s jewelry box. This both delighted and frightened Valerie, because they looked like they could snap.

Valerie, herself unsnappable, leapt off the lowest branch and onto the porch with a solid thump.

She was not excitable like other girls, whose cheeks were pink or round. Valerie’s were smooth and even and pale white. Valerie didn’t really think of herself as pretty, or think about what she looked like, for that matter. No one else, though, could forget the corn-husk blonde with unsettling green eyes that lit up like they were charged by lightning. Her eyes, that knowing look she had, made her seem older than she was.

“Girls, come on!” her mother called from inside the house, anxiety bristling through her voice. “We need to be back early tonight.” Valerie made it down before anyone could see that she had been in the tree at all.

Through the open door, Valerie saw Lucie bustle over to their mother clutching a doll she had dressed in scraps that Grandmother had donated to the cause. Valerie wished she could be more like her sister.

Lucie’s hands were soft and round, a little bit pillowy, something Valerie admired. Her own hands were knobby and thin, tough with calluses. Her body was all angles. She felt deep inside that this made her unlovable, someone no one would want to touch.

Her older sister was better than she was, that much Valerie knew. Lucie was kinder, more generous, more patient. She never would have climbed above the tree house, where she knew sensible people didn’t belong.

“Girls! It’s a full moon tonight.” Her mother’s voice carried out to her now. “And it’s our turn,” she added sadly, her voice trailing off.

Valerie didn’t know what to make of it being their turn. She hoped it was a surprise, maybe a present.

Looking down to the ground, she saw some markings in the dirt that formed the shape of an arrow.

Peter.

Her eyes widening, she headed down the steep, dusty stairs from the tree house to examine the marks.

No, it isn’t Peter, she thought, seeing that they were just random scratches in the soil.

But what if—?

The marks stretched away from her into the woods. Instinctively, ignoring what she should do, what Lucie would do, she followed them.

Of course, they led nowhere. Within a dozen paces, the marks disappeared. Mad at herself for wishful thinking, she was glad that no one had seen her following nothing to nothing.

Before he’d left, Peter used to leave messages for her by drawing arrows in the dirt with the tip of a stick; the arrows guided her to him, often hiding deep in the woods.

He had been gone for months now, her friend. They had been inseparable, and Valerie still couldn’t accept the fact that he wasn’t coming back. His leaving had been like snipping off the end of a rope—leaving two unraveling strands.

They had been inseparable, and Valerie still couldn’t accept the fact that he wasn’t coming back. His leaving had been like snipping off the end of a rope—leaving two unraveling strands.

Peter hadn’t been like other boys, who teased and fought. He understood Valerie’s impulses. He understood adventure; he understood not following the rules. He never judged her for being a girl.

“Valerie!” Grandmother’s voice now called. Her calls were to be answered more urgently than Valerie’s mother’s because her threats might actually be carried out. Valerie turned from the puzzle pieces that had led to no prize, and hurried back.

“Down here, Grandmother.” She leaned against the base of the tree, delighting in the feel of the sandpaper bark. She closed her eyes to feel it fully—and heard the grumbling of wagon wheels like an approaching thunderstorm.

Hearing it, too, Grandmother slipped down the stairs to the forest floor. She wrapped Valerie in her arms, the cool silk of her blouse and the clunky jumble of her amulets pressing against Valerie’s face. Her chin on Grandmother’s shoulder, Valerie saw Lucie moving cautiously down the tall stairs, followed by their mother.

Her chin on Grandmother’s shoulder, Valerie saw Lucie moving cautiously down the tall stairs, followed by their mother.

“Be strong tonight, my darlings,” Grandmother whispered. Held tightly, Valerie stayed quiet, unable to voice her confusion. For Valerie, each person and place had its own scent—sometimes, the whole world seemed like a garden. She decided that her grandmother smelled like crushed leaves mingled with something deeper, something profound that she could not place.

As soon as Grandmother released Valerie, Lucie handed her sister a bouquet of herbs and flowers she’d gathered from the woods.

The wagon, pulled by two muscular workhorses, came bumping over the ruts in the road. The woodcutters were seated in clusters atop freshly chopped tree stumps that slid forward as the wagon lurched to a stop in front of Grandmother’s tree. Branches—the fattest ones at the bottom and the lightest on top—were piled between the men. To Valerie, the riders looked like they were made of wood themselves.

Valerie saw her father, Cesaire, seated near the back of the cart. He stood and reached down for Lucie. He knew better than to try for Valerie. He reeked of sweat and ale, and she stayed far away from him.

“I love you, Grandmother!” Lucie called over her shoulder as she let Cesaire help her and her mother over the side of the cart. Valerie scrambled up and in on her own. With a snap of the reins, the wagon lumbered to a start.

A woodcutter shifted aside to give Suzette and the girls room, and Cesaire reached over, landing a theatrical kiss on the man’s cheek.

“Cesaire,” Suzette hissed, casting him a quietly reproachful glance as side conversations picked up in the wagon. “I’m surprised you’re still conscious at this late hour.”

Valerie had heard accusations like this before, always veiled behind a false overtone of cleverness or wit. And yet it still jolted her to hear them said with such a tone of contempt.

She looked at her sister, who hadn’t heard their mother because she was laughing at something another woodcutter had said. Lucie always insisted that their parents were in love, that love was not about grand gestures but rather about the day to day, about being there, going to work and coming home in the evening. Valerie had tried to believe that this was true, but she couldn’t help feeling that there had to be something more to love, something less practical.

Lucie always insisted that their parents were in love, that love was not about grand gestures but rather about the day to day, about being there, going to work and coming home in the evening. Valerie had tried to believe that this was true, but she couldn’t help feeling that there had to be something more to love, something less practical.

Now she hung on tight as she leaned over the back rails of the wagon, peering down at the rapidly disappearing ground. Feeling dizzy, she turned to face back in.

“My baby.” Suzette pulled Valerie onto her lap, and Valerie let her. Her pale, pretty mother smelled like almonds and powdery flour.

As the wagon emerged from the Black Raven Woods and rumbled alongside the silver river, the dreary haze of the village came into full view. Its foreboding was palpable even at a distance: Stilts, spikes, and barbs jutted up and out. The granary’s lookout tower, the town’s tallest point, stretched high.

It was the first thing one felt while coming over the ridge: fear.

Daggorhorn was a town full of people who were afraid, people who felt unsafe even in their beds and vulnerable with each step, exposed with every turn.

The people had begun to believe that they deserved the torture—that they had done something wrong and that something inside them was bad.

Valerie had watched the villagers cowering in fear every day and felt her difference from them. What she feared more than the outside was a darkness that came from inside her. It seemed as if she was the only one who felt that way.

Other than Peter, that is.

She thought back to when he’d been there, the two of them fearless together and filled with reckless joy. Now she resented the villagers for their fear, for the loss of her friend.

Once through the massive wooden gates, the town looked like any other in the kingdom. The horses kicked up pockets of dust as they did in all such towns, and every face was familiar. Stray dogs roamed the streets, their bellies empty and drooping, sucked in impossibly tight at the sides so that their fur looked striped. Ladders rested gently against porches. Moss spilled out from crevices in roofs and crawled across the fronts of houses, and no one did anything about it.

Ladders rested gently against porches. Moss spilled out from crevices in roofs and crawled across the fronts of houses, and no one did anything about it.

Tonight, the villagers were hurrying to bring their animals inside.

It was Wolf night, just as it had been every full moon for as long as anyone could remember.

Sheep were herded and locked behind heavy doors. Handed off from one family member to another, chickens strained their necks as they were thrust up ladders, stretching them out so far that Valerie worried they would rip them clean off their own bodies.

As they reached home, Valerie’s parents spoke to each other in low voices. Instead of climbing up the ladder to their raised cottage, Cesaire and Suzette approached the stable underneath, which was darkened by the shady gloom of their house. The girls ran ahead of them to greet Flora, their pet goat. Seeing them, she clattered her hooves against the rickety boards of the pen, her clear eyes watery with anticipation.

“It’s time now,” Valerie’s father said, coming up behind Valerie and Lucie and laying his hands on their shoulders.

“Time for what?” Lucie asked.

“It’s our turn.”

Valerie saw something in his stance that she didn’t like, something menacing, and she backed away from him. Lucie reached for Valerie’s hand, steadying her as she always did.

A man who believed in speaking truthfully to his children, Cesaire plucked at the fabric of his pants and bent down to have a word with his two little girls. He told them that Flora was to be this month’s sacrifice.

“The chickens provide us with eggs,” he reminded them. “The goat is all we can afford to offer.”

Valerie stood in stupefied disbelief. Lucie knelt down sorrowfully, scratching her little fingernails up and down the goat’s neck and pulling softly at her ears in the way that animals will only allow children to do. Flora nudged Lucie’s palm with her newly sprouted horns, trying them out.

Suzette glanced at the goat and then looked at Valerie expectantly.

“Say good-bye, Valerie,” she said, resting her hand on her daughter’s slender arm.

But Valerie couldn’t—something held her back.

“Valerie?” Lucie looked at her imploringly.

She knew her mother and sister thought she was being cold. Only her father understood, nodding at her as he led the goat away. He steered Flora by a thin rope, her nostrils flaring and her eyes sharp with unease. Holding back bitter tears, Valerie hated her father, for his sympathy and for his betrayal.

Valerie was careful, though. She never let anyone see her cry.

That night, Valerie lay awake after her mother had put them to bed. The glow of the moon streamed through her window, stretching across the floorboards in one great pillar.

She thought hard. Her father had taken Flora, their precious goat. Valerie had seen Flora birthed on the floor of the stable, the mother goat bleating in pain as Cesaire brought the small, damp kid forth into the world.

She knew what she had to do.

Lucie padded along beside Valerie, leaving the warmth of their bed and heading down the loft ladder and to the front door.

“We’ve got to do something!” Valerie whispered urgently, beckoning for her sister to join her.

But Lucie stayed back, fearful, shaking her head and wordlessly willing Valerie to stay, too. Valerie knew that she couldn’t do as her elder sister did, huddling in the doorway, clutching her doe hide. She would not just stand by and watch the events of her life unfold. But just as Lucie had always admired Valerie’s commitment, Valerie admired her sister’s restraint.

Valerie wanted to cover up her uneasy sister now and tell her not to worry, to say, “Shhhh, sweet Lucie, everything will be all right by morning.” Instead, she turned, holding down the latch of the door with her thumb and letting it ease noiselessly into the jamb before she plunged into the cold.

The village was especially sinister that night, backlit by the brightness of the moon, the color of shells that had been bleached by the sun. The houses hulked like tall ships, and the branches of the trees jutted out like barbed masts against the night sky. As Valerie set out for the first time on her own, she felt like she was discovering a new world.

The houses hulked like tall ships, and the branches of the trees jutted out like barbed masts against the night sky. As Valerie set out for the first time on her own, she felt like she was discovering a new world.

To reach the altar more quickly, Valerie took a shortcut through the woods. She stepped through the moss, which had the texture of bread soaked through with milk, and avoided the mushrooms, white blisters whose tops were speckled with brown, as if dusted with cinnamon.

Something pulled at her out of the dark, clinging to her cheek like wet silk. A spider’s web. It felt like her entire body was crawling with invisible insects. She tore at her face, trying to brush off the filmy web, but the strands were too thin, and there was nothing to hold on to.

The full moon hung lifeless overhead.

Once she reached the clearing, her steps became more cautious. She felt queasy as she walked, the same feeling she got while cleaning a sharp knife—the feeling that one small slip could be disastrous. The villagers had dug a sinkhole trap into the soil, staked sharpened wooden rods into the ditch, and covered them with a false ground of grass. Valerie knew that the hole was somewhere near, but she had always been led safely around it. Now, even though she thought she’d passed it, she wasn’t entirely sure.

The villagers had dug a sinkhole trap into the soil, staked sharpened wooden rods into the ditch, and covered them with a false ground of grass. Valerie knew that the hole was somewhere near, but she had always been led safely around it. Now, even though she thought she’d passed it, she wasn’t entirely sure.

A familiar bleating pulled her on, though, and there ahead she could see Flora, pathetic and alone, stumbling in the wind and crying out. Valerie began to run toward the goat’s sad form struggling alone in the bone-white moonlit clearing. Seeing Valerie, Flora reared up wildly and craned her slender neck in Valerie’s direction as much as her rope would allow.

“I’m here, I’m here,” Valerie began to call out, but the words died in her throat.

She heard something bounding furiously over a great length at a quick pace, coming closer and closer still through the darkness. Valerie’s feet refused to move, much as she tried to continue.

In a moment, everything went still again.

And it appeared.

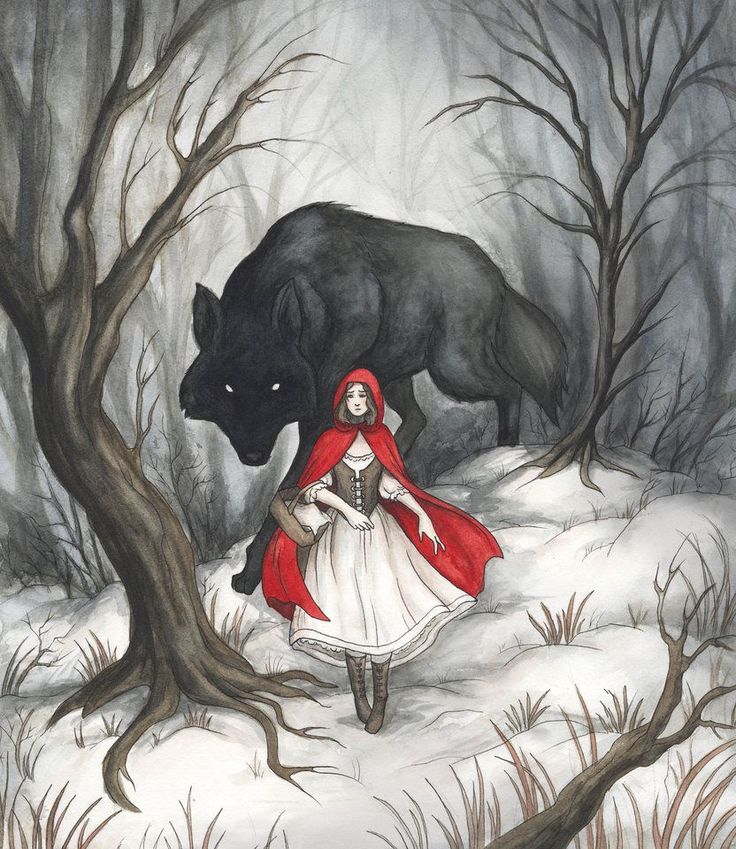

At first, just a streak of black. Then the Wolf was there, facing away from her, its back massive and monstrous, its tail moving seductively back and forth, tracing a pattern in the dust. It was so big that she could not see it all at once.

Valerie’s breath burst out in a gasp, jagged with fear. The Wolf’s ears froze, then quivered, and it turned its eyes to meet hers.

Eyes that were savage and beautiful.

Eyes that saw her.

Not an ordinary kind of seeing, but seeing in a way that no one had seen her before. Its eyes penetrated her, recognizing something. The terror hit her then. She crumpled to the ground, unable to look any longer, and burrowed deep into the refuge of darkness.

A great shadow loomed over her. She was so small and it was so immense that she felt the cover of the standing figure weigh down upon her as though her body were sinking into the ground. A shiver coursed through her body as it responded to the threat. She imagined the Wolf tearing through her flesh with its hooked canines.

She imagined the Wolf tearing through her flesh with its hooked canines.

There was a roar.

Valerie waited to feel the leap, to feel the snap of its jaws and the ripping of claws, but she felt nothing. She heard a scuffling and a tinkling of Flora’s bells, and it was only then that she realized the shape had lifted. From her crouch, she heard gnashing and gnarling. But there was something else, another sound that she couldn’t identify. Much later, she would learn that it was the roar of a dark rage being let loose.

Then there followed a panicked silence, a frenetic calm. Finally, she couldn’t resist slowly lifting her head to look for Flora.

All was still.

Nothing was left but the broken tether still tied to the stake, lying slack on the dusty ground.

Continues...

Excerpted from Red Riding Hood by Blakley-Cartwright, Sarah Copyright © 2011 by Blakley-Cartwright, Sarah. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Red Riding Hood - Plugged In

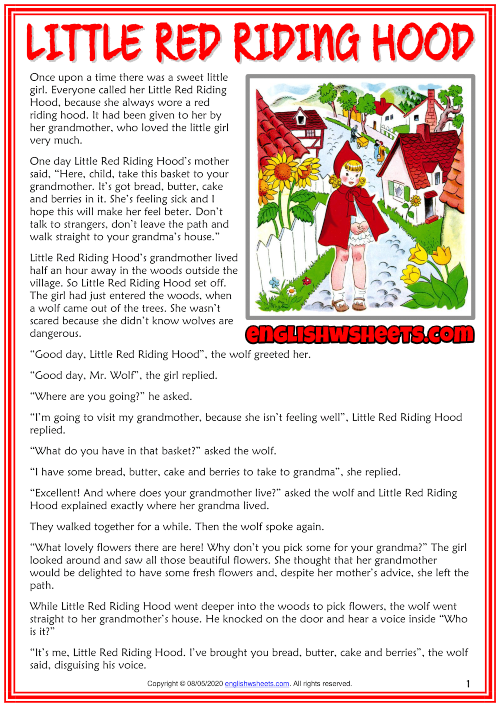

The villagers of Daggorhorn lead quiet lives except for when the full moon rises. Then they take turns leaving a sacrifice to appease the werewolf that stalks the woods. This uneasy truce was agreed to years earlier in order to keep the beast from killing the people within the town walls.

Valerie has always been different from her older sister, Lucie. Everyone in Daggorhorn loves Lucie’s grace and kindness, while most wonder at Valerie’s free spirit and peculiar ways. While her friends and Lucie all swoon over Henry, the blacksmith’s son, Valerie longs to know what lies outside the village walls.

The girls are excited when harvest time arrives because it means young men from other towns will come to work in the village. Valerie is shocked when her childhood friend Peter is among the workers. Peter had to flee Daggorhorn years earlier when his father was caught stealing and his horse reared and killed Henry’s mother. Valerie is surprised at her attraction to the brooding man she used to know.

Valerie is shocked when her childhood friend Peter is among the workers. Peter had to flee Daggorhorn years earlier when his father was caught stealing and his horse reared and killed Henry’s mother. Valerie is surprised at her attraction to the brooding man she used to know.

Valerie, Lucie and their friends sneak away from their chaperone when they camp out with other villagers to celebrate the harvest. Valerie meets clandestinely with Peter. After a thrilling horseback ride through the forest, he leaves her alone while he returns the horse to its owner.

Valerie sees the full, blood-red moon and hears a terrifying growl in the woods. She flees with the other festival-goers to the village and is assured her sister is safe at a friend’s house. In the morning, Valerie meets again with Peter. He’s learned that she’s been betrothed to Henry.

Valerie is shocked. Before she and Peter can run away together, they hear the church bell toll four times, signaling someone’s death by the werewolf. Valerie follows the villagers to Lucie’s mauled body. While mourners come to grieve with Valerie and her parents, she withdraws into herself, ignoring the sympathy of her betrothed and hoping that Peter will come.

Valerie follows the villagers to Lucie’s mauled body. While mourners come to grieve with Valerie and her parents, she withdraws into herself, ignoring the sympathy of her betrothed and hoping that Peter will come.

When Peter does arrive, Valerie’s mother convinces him to leave her daughter alone, knowing he will never be able to take care of Valerie like Henry, a wealthy blacksmith, can. Meanwhile Father Auguste, the local priest, sends word to a well-known cleric and werewolf hunter for help, but the men of the village set off to find the beast themselves. Before the night is out, the village reeve has brought home the body of a huge wolf, but not before it killed Henry’s father.

Father Solomon, the werewolf hunter, arrives with his guards to track the beast. He claims that the wolf killed by the Reeve is an ordinary wolf; otherwise it would have turned into its human form come daybreak. The villagers don’t want to believe him and instead plan another festival to celebrate.

During the height of the dancing, Henry and Peter fight over Valerie. She follows Peter to make sure he’s not hurt. He tries to evade her, remembering the promise he made to her mother, but when Valerie confesses her love for him, he whisks her away to the granary. They are interrupted in their tryst by men who need Peter’s help moving a keg.

Before the night is over, the werewolf scales Daggorhorn’s walls and attacks, killing several people. The wolf finds Valerie and her friend Roxanne, trapping them in an alley. Valerie is shocked to discover that she can understand the wolf’s growls. It threatens that it will kill everyone she loves if she doesn’t leave the village with it.

Before it can make good on its threats by killing her friend, they are found by Solomon and one of his bowman. The wolf escapes but promises to return for Valerie before the blood moon wanes. The next morning, Henry confesses he saw Valerie and Peter in the granary. He breaks off their engagement.

The villagers beg Solomon to take on the hunt for the beast. He agrees, but convinces them that the beast is one of them. He and his men investigate the town during the day, looking for people who practice witchcraft or who are in league with the Devil.

They take Claude, the town simpleton, in for questioning, but instead, they torture him, slowly burning him in a metal cage shaped like an elephant. Claude’s sister, Roxanne, tries to save his life by confessing Valerie’s conversation with the wolf. When Valerie admits the story is true, she is thrown into jail and used as bait to bring the wolf into town.

Henry and Peter work together to save the girl they both love. Henry forges an extra set of keys to free Valerie from the chains securing her to an altar in the town center. Solomon captures Peter and throws him into the metal elephant to be dealt with after they’ve killed the wolf. Unable to escape before the wolf or Solomon’s soldiers find them, Valerie and Henry flee toward the sanctuary of the churchyard.

They are stopped by Solomon, who captures Valerie. Once again using her as bait, he hopes to keep the werewolf in town until it can be killed or the sun rises. When an arrow fails to hit the animal, Solomon throws Valerie aside and attacks it himself. The werewolf bites off his hand and continues to stalk Valerie. She agrees to leave with the beast to save her family and friends. But the villagers won’t let her sacrifice herself for them.

One by one they step forward and pledge to defend her. The wolf escapes into the woods before sunrise. Enraged, Solomon attacks Valerie, promising that she will burn as a witch. He is stopped by the captain of the guard, who reminds the cleric that a man bitten by a werewolf under the blood moon is cursed to become one himself. The captain kills Solomon, and Valerie is taken to home to recover.

Valerie seeks out her grandmother, after a disturbing dream in which her grandmother turned into the werewolf. She meets Henry, who has joined the remaining guards to hunt for the monster. Valerie’s feelings for him have changed since he aided her escape, and she finds herself aching for what might have been between them.

Valerie’s feelings for him have changed since he aided her escape, and she finds herself aching for what might have been between them.

He tells her that no one has seen Peter since the werewolf attacked and hints that he believes his rival to be the beast. Henry promises to do what he has to if he finds Peter. Valerie runs through the woods to her grandmother’s house but comes upon Peter instead. Her love for him overcomes her doubts as to whether he is the wolf, and she decides to leave Daggorhorn with him.

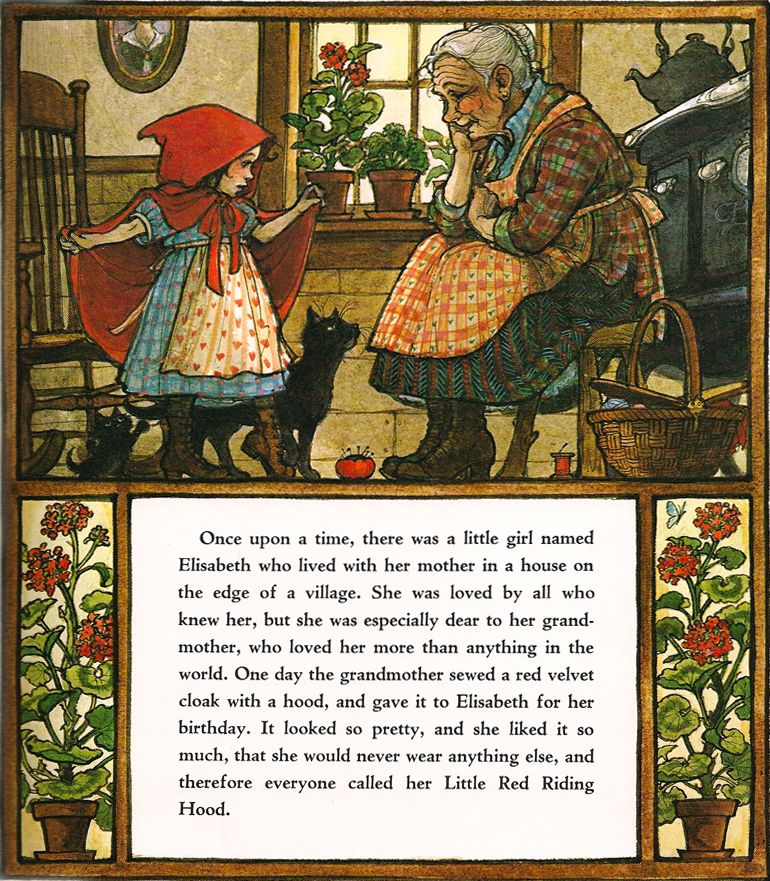

Beate Teresa Hanika. Say Little Red Riding Hood

Khanika B.T. Say Little Red Riding Hood: [novel] / Beate Teresa Hanika; [per. with him. V. Komarova]. - Moscow: CompassGuide, 2011. - 352 p. — (Generation www.).

This book continues to be discussed. Some say that showing teenagers, especially girls, the unsightly and sometimes “shameful” truth of life is useful and important, because knowing the “whole truth” will serve as a “vaccination” and help them cope with life's difficulties in the future if they suddenly arise. Others believe that the conflict presented in the book - a grandfather sexually harassing his own granddaughter - is “too much”, that “the average child is unlikely to face such an outrage in reality” and that such books should not confuse the immature minds of teenage readers . nine0003

To be honest, we believe that showing the teenage reader the truth is necessary, absolutely necessary. Because our children do not grow up in a greenhouse, not in an ivory tower, but in a rather unpredictable world that can turn out to be both beautiful and terrible, and the adults responsible for the children do not have the opportunity to warn the child “against everything”. No matter how we protect, no matter how we protect our offspring, you can’t foresee everything, and we will only have to be horrified: where did this attack come from? In this regard, books like the one under discussion are very useful: they0007 alert . They show that a person in life can suddenly have an ambiguous and dangerous situation, from which they will have to get out without outside help.

But simply showing the truth is not all. One should also think about what the reader will take out of what he has read.

…Because the reader takes something out of what they read anyway, even when they don't think about it. Of course, after reading, a person rarely forces himself to draw clear conclusions - "I read such and such a book and understood such and such." But the impression - albeit vague, not framed in folding words, not realized at the level of precise formulations - still remains with the reader. nine0003

So what impression does the reader get from a teenage novel about a “little red riding hood” almost eaten by a gray wolf in the guise of his own grandfather?

But what.

The girl Malvina finds herself in a difficult, incomprehensible and embarrassing situation (her own grandfather, as it was said, harasses his own granddaughter) and - does not find a way out of it . At the same time, the first, it would seem, the defenders of the child - the parents - defiantly turn away from their daughter, not even wanting to hear what happened to her and why she does not want to visit her grandfather. nine0003

The problem is solved mechanically: the grandfather has a stroke, and now he can no longer molest the girl. Hooray. And in a sense, the old man is not even "pityful."

What if he had iron health? And if the harassment continued? Could the girl find a way out of this situation? Alone, without the help of parents who would still turn a blind eye to "impossible" circumstances?

If Teresa Hanika had written about this… But she ended the novel on an optimistic note: her grandfather was admitted to the hospital, the girl nevertheless spoke out to her best friend, consoled herself and distracted herself from troubles with positive emotions, because, for now, this and that, in a good boy fell in love with her. nine0027 Oh, how well everything turned out, didn't it?

At the same time, we see that with the physical elimination of the grandfather from the life of the granddaughter, not only the problem itself is eliminated, but also its expected consequences. And this, sorry, is somehow hard to believe.

Reading this story, we understand that the immoral harassment of the old pervert seems to be supposed to injure the girl's psyche. But the text shows that the girl - by and large - at least something. When the time comes to cuddle with the boy, Malvina calmly hugs him and feels great. The disgusting actions of the grandfather did not scare the girl away from the normal manifestations of normal human physicality. On the one hand - well, thank God. On the other hand, does it happen? So that years of humiliating and unpleasant addiction do not affect the teenage girl in the least, do not damage the formation of her ideas about men, do not turn away from any contact with the opposite sex? nine0003

And an even more surprising thing: after everything that happened - after the parents left their daughter alone with trouble - Malvina does not get annoyed with them at all.

People! After all, the book is not about how an old pedophile inclines a child to incest, but about the fact that a child who finds himself in an intolerable situation cannot find protection. And not in the abstract "world of adults", not in the "humanitarian and social environment", but in one's own family.

A terrible thing happens to a child , he tries to call for help from mom and dad - and receives in response: "What nonsense" .

And my own mother, and my own father, and my brother and sister - they don't want to listen, they don't want to see, they don't want to believe Malvina. They leave her alone - without understanding, without help, without protection. After all, this is actually a betrayal! Isn't that a mental trauma for a girl? Not a terrible resentment for life?

Teresa Hanika does not write anything about this.

Let's say that "today", when the book ended, Malvina just feels good from the mere thought that grandfather is no longer dangerous and that the topic for family conflict has been closed. But what will happen tomorrow, the day after tomorrow? As an adult, and not only a reader, I understand that after a while Malvina will still have a lot of problems - with communication, with trust, with elementary female self-determination. And these problems cannot be mechanically “turned off” and put on the brakes. nine0003

So why was this story conceived and written?

To simply announce the existence of the problem - "what kind of bad grandfathers there are" - it is enough to write an essay in some family magazine. And if a novel is written for teenagers, the reader has the right to expect from the author some kind of... well, moral support or something... consolation, perhaps...

Poland and living next door to the "gray wolf". Frau Biczek generally understands what is happening with the "little red riding hood", but, characteristically, nothing expedient in the social sense does not undertake. She can sympathize with Malvina, feed her vegetable stew, tell about a long-standing story with a classmate who had a similar misfortune, and give the girl advice: "Everything can be changed if only you speak" .

A very useful and timely piece of advice!

Malvina is trying to speak! She wants to say , she is looking for words. .. But loving relatives, who wish only the best for the girl, deliberately turn these words so that there is no problem! Grandpas always kiss their granddaughters, there's nothing wrong with that...

Suppose Malvina found the strength to tell her best friend about everything. But, firstly, this happened after the grandfather was in the hospital. And secondly - if the girl does not have a best friend? Then how to be? And what can a best friend do - complain to social services?

Even my grandmother, my beloved grandmother, while she was alive, preferred to pretend that this was the way it should be. She allowed her husband to seduce her little granddaughter, pretending that nothing was happening. Suppose the grandmother was seriously ill and knew that she would not live long, but is this an excuse? nine0003

Do something like in this situation? How to be saved??? Go out to the square and sing a psalm? To whom shall we sing my sorrow, whom shall I call upon weeping?

No answer.

And so the story of the "Little Red Riding Hood" seems to me somehow ... useless, or something.

No, I am not saying that the usefulness of a book is the first and main criterion for evaluating its quality; but if we are dealing with a teenage reader, we should not forget that he is looking for answers to some of his everyday questions in the book, building a system of life principles and guidelines, comparing book experience with his own. nine0003

At a minimum, the book can make it clear that "here in such and such a situation, the heroine acted in such and such a way, and this is what came of it." And if the book shows that “the heroine tried to do this and that, but nothing came of it, and then everything settled down by itself,” this is somehow dishonest, or something.

“Everything is bad, life is terrible, enemies are all around, and you can’t do anything about it until it somehow resolves itself” – such an attitude, even if it is quite true, is suitable for books addressed to adults. In a book for teenagers, however, it is necessary to show whether there is a way out of this situation. At least look for it, this way out...

If the author of a "youth novel" takes his "little red riding hood" into the forest and unleashes a gray wolf on her, shouldn't there be at least two or three ways to get rid of such a misfortune?

Or did the author really mean to say that it is basically impossible to get rid of the wolf, unless the predator suddenly bursts from overeating? Nothing will save the girl until the grandfather has enough kondrashka? And if that's not enough, then the parents will be left with their egoism and indifference, Malvina - with their fear and shame, and the reader - with a sense of hopelessness? nine0003

In general, I would like to talk about this topic. And if you have something to say, the author of the Little Red Riding Hood, please say so. And preferably in more detail.

And if you have nothing to say, it's better to be silent.

Maria Poryadina

Alexa Riley ★ Little Red Riding Hood read the book online for free

1234567...28

Attention!

The text of the book is translated solely for the purpose of familiarization, not for material gain. Any commercial or other use other than introductory reading is prohibited. nine0003 Ruby is the proud owner of the "Pretty Red Basket", she recently moved to this city and wants to build her business here. But when the sexy sheriff, Dominic Wolfe, starts stealing her clients, she finds it's hard to go crazy when you're burning with desire. Dominic is a werewolf and his wolf craves Ruby. As for the second, he has his eye on her and struggles with having to mark her as his own. But when the Wedding Moon is full, he can no longer control his wolf. nine0003 Pranks and pleasures are the last thing that comes to mind when the lust for mating takes its toll and his obsession is put to the test. Attention: this story is sexually modified, unlike the classic fairy tale, which is about a red cloak, a basket of treats and a hungry wolf. Chapter 1 Ruby - We can't sell this! I look down at the items that are shaped like tiny penises and try to convince myself that I'm seeing food. It's 5:30 am and I haven't had coffee yet, so maybe my brain is still awake. I look down at the tray again, hoping I was wrong. Nope. Definitely tiny members. nine0003 - Why not? Gwen takes one of the dick-shaped cookies and bites off the head, making me cringe. I don't have a penis, but I can imagine how much it hurts. - They are tasty. I focused on pumpkin spices. Bitches love pumpkin spice. She nods her head, as if confirming that the bitches love pumpkin spices. She swallows the rest of the biscuits and groans contentedly. "Swallowing" takes on a whole new meaning in Pretty Little Red Basket. - Do bitches bite off heads too? nine0003 Gwen rubs her nose and looks at the batch of cookies on the cutting table. - They look like members, but they are actually brooms. “But even as she defends herself, she tilts her head to study them. - Pubic hair - I point to what should be broom bristles, then run my finger over what I assume should look like a real broom. - Member. The girl bites her lip and I can tell she's trying to find a way to prove me wrong. nine0003 - Gwen, if that's a damn broom, why is she coming? - At the end of the cookie there is a white icing that shoots out of it and clearly looks like sperm. - It's kind of magic coming out! Those are witch brooms! - she says it so seriously that I'm not sure who she's trying to convince here - me or herself. - Yes, it is noticeable that it is coming out. Suddenly we both laugh. I should be upset, but laughing is great. It's something I haven't done in a long time, and I laugh, enjoying the stupidity of the whole situation. nine0003 When we finally stop laughing, her face becomes alarmed. This book is written to make you smile, cheer you up and help you celebrate Halloween!

Learn more