School for kids who can't read good

Derek Zoolander Center for Kids

[Spoiler Alert: This post is not about Zoolander 2 — Sorry]

Hi all,

Hope you had another good week.

Welcome to Friday Thing/k — a brand storytelling canvas where I’d like to share with you smart, creative, inspiring, engaging, cool, and innovative content marketing ideas that take my digital marketing breath away once a week.

Derek Zoolander had a higher purpose. He knew that there was a lot more to his life as an influential model than just “being really, really, ridiculously good looking.” His larger aspiration and mission being, to build an education center.

Now hold that thought, we’ll get back to it shortly.

If you don’t already know, I love to discover content online and getting lost and always-always finding thing/ks. That’s how these posts are born.

In fact, not but just a few a days ago-Eureka! I came across an interesting article published last October on the Harvard Business Review about “How an Accounting Firm Convinced Its Employees They Could Change the World. ”

The article discusses the idea — and here’s where we get back to the significance of Zoolander — that a workforce motivated by a strong sense of higher purpose is essential to engagement.

A case study presented within the article from KPMG, one of the largest accounting firms in the world, described how vivid posters were created to celebrate and shine light on the variety of different employee stories being built:

Probably not the answers you would expect to hear from accountants when asked, “What do you do at KPMG?”

But that’s exactly how KPMG reshaped how its employees think about their own work via their Higher Purpose campaign.

As KPMG embarked on an initiative to build a stronger connection to the firm, they followed up the important question with answers received in the form of a video entitled, “We Shape History:”

As you can see, history coincides with the company

story — a great message to internal teams.

It reminded me of the historic event scenes Forrest Gump participated in for the movie — similar, but these really connect.

The video lit a flame for an inspiring cross-company storytelling campaign with additional posters celebrating the impact KPMG people have made on behalf of clients, and even an app that enabled content creation and distribution around their “10,000 Stories Challenge” goal.

According to HBR: 90% of employees reported that the Higher Purpose campaign increased pride in KPMG and improved overall morale.

Not sure about you, but I can always trust accountants with numbers.

To recap, why I love KPMG’s marketing initiative on so many levels:

- A campaign targeted to the brand’s most important target audience – The people, at the beginning and end of the day, are the ones who create and shape the brand.

- A creative campaign which is brilliantly executed –

Powerful, emotional, and inspiring on the part of these accountants. I think they have shown that anything can be story-fied. As William Shakespeare said, and I will never feel bad about quoting, “The world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players.”

I think they have shown that anything can be story-fied. As William Shakespeare said, and I will never feel bad about quoting, “The world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players.” - A campaign from the top of the company down –

From the chairmen to the interns — it encompassed everyone’s story. And through that approach, their goal for increased engagement with the brand was met. Talk about the holy grail of content marketing. - A campaign that happened with content – It doesn’t matter what industry, it’s all about finding what resonates.

So, if you were wondering what I’m doing at Outbrain, I’m helping the fifth pillar of democracy (journalism) stay strong and relevant.

See you next Friday.

As always, feedback is more than welcome, and needed so please leave comments below. Additionally, if you have anything/k in mind, I would love to discover it.

Just call me Joe.

Why Millions Of Kids Can't Read And What Better Teaching Can Do About It : NPR

LA Johnson/NPR

LA Johnson/NPR

Jack Silva didn't know anything about how children learn to read. What he did know is that a lot of students in his district were struggling.

What he did know is that a lot of students in his district were struggling.

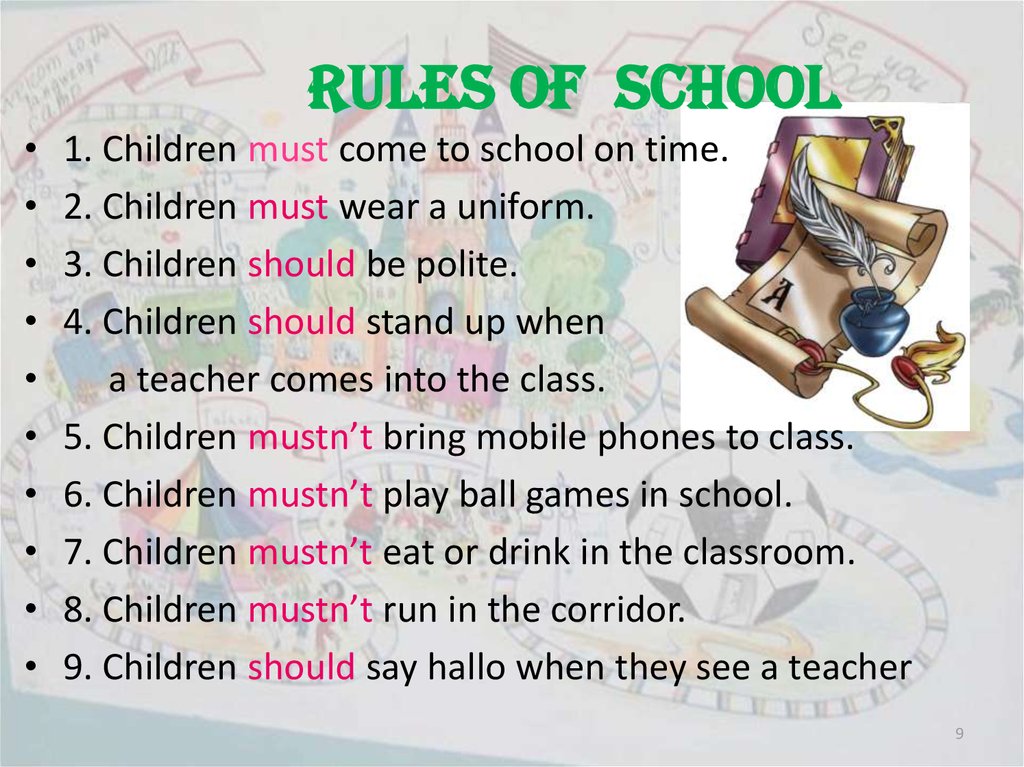

Silva is the chief academic officer for Bethlehem, Pa., public schools. In 2015, only 56 percent of third-graders were scoring proficient on the state reading test. That year, he set out to do something about that.

"It was really looking yourself in the mirror and saying, 'Which 4 in 10 students don't deserve to learn to read?' " he recalls.

Bethlehem is not an outlier. Across the country, millions of kids are struggling. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, 32 percent of fourth-graders and 24 percent of eighth-graders aren't reading at a basic level. Fewer than 40 percent are proficient or advanced.

One excuse that educators have long offered to explain poor reading performance is poverty. In Bethlehem, a small city in Eastern Pennsylvania that was once a booming steel town, there are plenty of poor families. But there are fancy homes in Bethlehem, too, and when Silva examined the reading scores he saw that many students at the wealthier schools weren't reading very well either.

Silva didn't know what to do. To begin with, he didn't know how students in his district were being taught to read. So, he assigned his new director of literacy, Kim Harper, to find out.

The theory is wrong

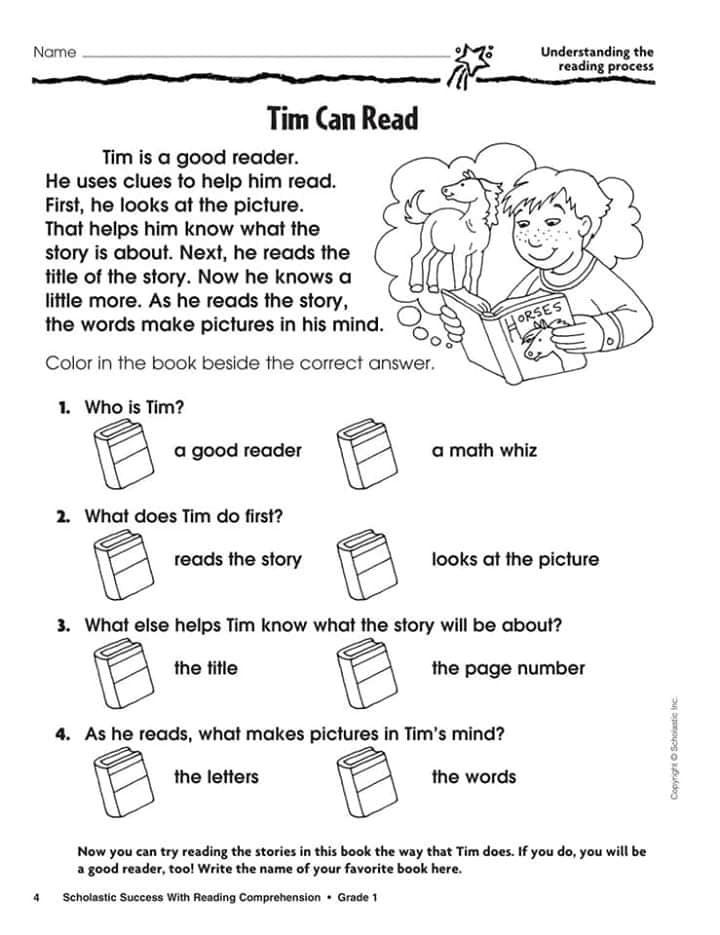

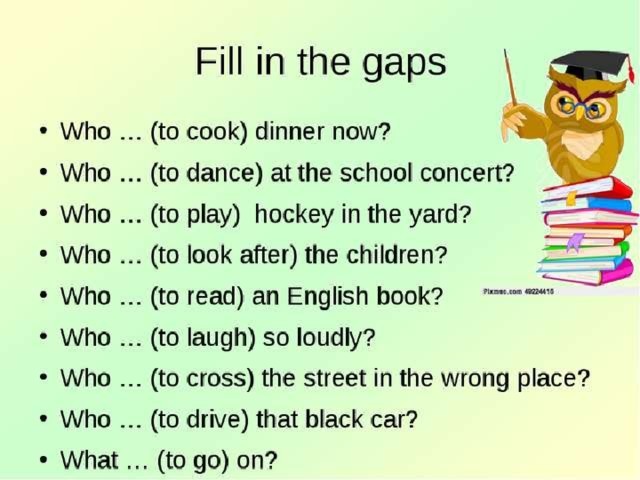

Harper attended a professional-development day at one of the district's lowest-performing elementary schools. The teachers were talking about how students should attack words in a story. When a child came to a word she didn't know, the teacher would tell her to look at the picture and guess.

The most important thing was for the child to understand the meaning of the story, not the exact words on the page. So, if a kid came to the word "horse" and said "house," the teacher would say, that's wrong. But, Harper recalls, "if the kid said 'pony,' it'd be right because pony and horse mean the same thing."

Harper was shocked. First of all, pony and horse don't mean the same thing. And what does a kid do when there aren't any pictures?

This advice to a beginning reader is based on an influential theory about reading that basically says people use things like context and visual clues to read words. The theory assumes learning to read is a natural process and that with enough exposure to text, kids will figure out how words work.

The theory assumes learning to read is a natural process and that with enough exposure to text, kids will figure out how words work.

Yet scientists from around the world have done thousands of studies on how people learn to read and have concluded that theory is wrong.

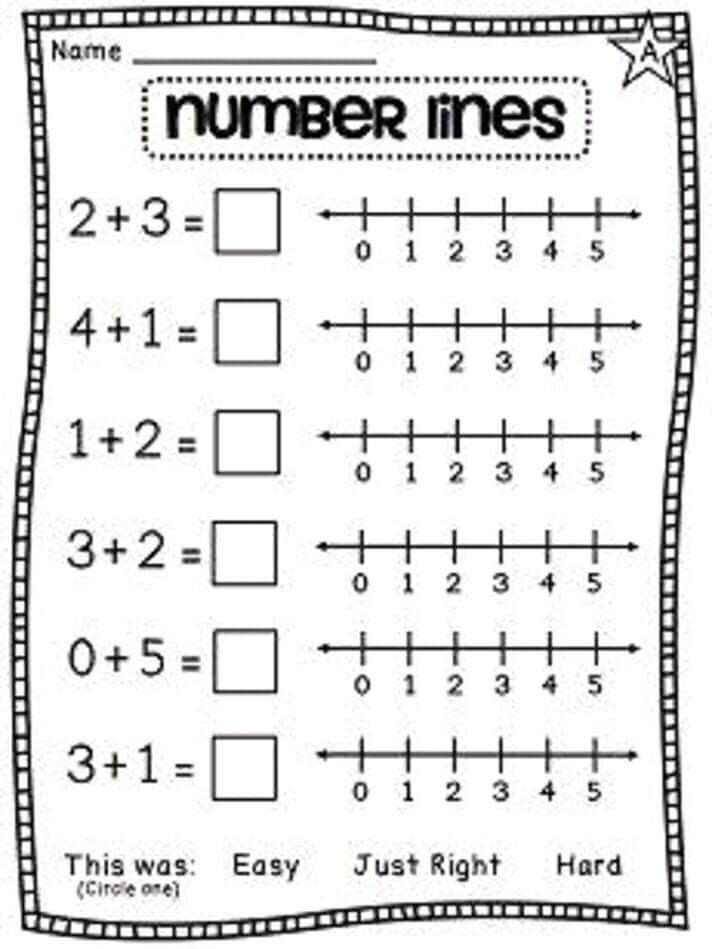

One big takeaway from all that research is that reading is not natural; we are not wired to read from birth. People become skilled readers by learning that written text is a code for speech sounds. The primary task for a beginning reader is to crack the code. Even skilled readers rely on decoding.

So when a child comes to a word she doesn't know, her teacher should tell her to look at all the letters in the word and decode it, based on what that child has been taught about how letters and combinations of letters represent speech sounds. There should be no guessing, no "getting the gist of it."

And yet, "this ill-conceived contextual guessing approach to word recognition is enshrined in materials and handbooks used by teachers," wrote Louisa Moats, a prominent reading expert, in a 2017 article.

The contextual guessing approach is what a lot of teachers in Bethlehem had learned in their teacher preparation programs. What they hadn't learned is the science that shows how kids actually learn to read.

"We never looked at brain research," said Jodi Frankelli, Bethlehem's supervisor of early learning. "We had never, ever looked at it. Never."

The educators needed education.

Learning the science of reading

Traci Millheim tries out a new lesson with her kindergarten class at Lincoln Elementary in Bethlehem, Pa. Emily Hanford/APM Reports hide caption

toggle caption

Emily Hanford/APM Reports

On a wintry day in early March 2018, a group of mostly first- and second-grade teachers was sitting in rows in a conference room at the Bethlehem school district headquarters. Mary Doe Donecker, an educational consultant from an organization called Step-by-Step Learning, stood at the front of the room, calling out words:

Mary Doe Donecker, an educational consultant from an organization called Step-by-Step Learning, stood at the front of the room, calling out words:

"Tell me the first sound you hear in 'Eunice'?"

"Youuu ... " the teachers responded.

Nope. "/Y/, /y/, before you get to the /oo/," Donecker explained. "How about "Charlotte?"

This was a class on the science of reading. The Bethlehem district has invested approximately $3 million since 2015 on training, materials and support to help its early elementary teachers and principals learn the science of how reading works and how children should be taught.

In the class, teachers spent a lot of time going over the sound structure of the English language.

Since the starting point for reading is sound, it's critical for teachers to have a deep understanding of this. But research shows they don't. Michelle Bosak, who teaches English as a second language in Bethlehem, said that when she was in college learning to be a teacher, she was taught almost nothing about how kids learn to read.

"It was very broad classes, vague classes and like a children's literature class," she said. "I did not feel prepared to teach children how to read."

Bosak was among the first group of teachers in Bethlehem to attend the new, science-based classes, which were presented as a series over the course of a year. For many teachers, the classes were as much about unlearning old ideas about reading — like that contextual-guessing idea — as they were about learning new things.

First-grade teacher Candy Maldonado thought she was teaching her students what they needed to know about letters and sounds.

"We did a letter a week," she remembers. "So, if the letter was 'A,' we read books about 'A,' we ate things with 'A,' we found things with 'A.' "

But that was pretty much it. She didn't think getting into the details of how words are made up of sounds, and how letters represent those sounds, mattered that much.

The main goal was to expose kids to lots of text and get them excited about reading. She had no idea how kids learn to read. It was just that — somehow — they do: "Almost like it's automatic."

She had no idea how kids learn to read. It was just that — somehow — they do: "Almost like it's automatic."

Maldonado had been a teacher for more than a decade. Her first reaction after learning about the reading science was shock: Why wasn't I taught this? Then guilt: What about all the kids I've been teaching all these years?

Bethlehem school leaders adopted a motto to help with those feelings: "When we know better, we do better."

"My kids are successful, and happy, and believe in themselves"

Cristina Scholl, first-grade teacher at Lincoln Elementary, uses a curriculum that mixes teacher-directed whole-class phonics lessons with small-group activities. Emily Hanford/APM Reports hide caption

toggle caption

Emily Hanford/APM Reports

Cristina Scholl, first-grade teacher at Lincoln Elementary, uses a curriculum that mixes teacher-directed whole-class phonics lessons with small-group activities.

Emily Hanford/APM Reports

In a kindergarten class at Bethlehem's Calypso Elementary School in March 2018, veteran teacher Lyn Venable gathered a group of six students at a small, U-shaped table.

"We're going to start doing something today that we have not done before," she told the children. "This is brand spanking new."

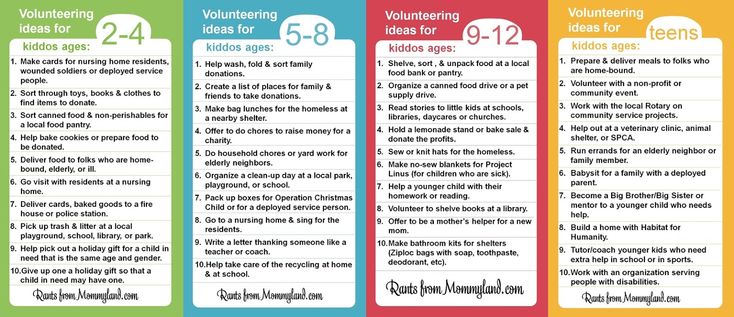

The children were writing a report about a pet they wanted. They had to write down three things that pet could do.

A little boy named Quinn spelled the word "bark" incorrectly. He wrote "boc." Spelling errors are like a window into what's going on in a child's brain when he is learning to read. Venable prompted him to sound out the entire word.

"What's the first sound?" Venable asked him.

"Buh," said Quinn.

"We got that one. That's 'b.' Now what's the next sound?"

Quinn knew the meaning of "bark." What he needed to figure out was how each sound in the word is represented by letters.

Venable, who has been teaching elementary school for more than two decades, says she used to think reading would just kind of "fall together" for kids if they were exposed to enough print. Now, because of the science of reading training, she knows better.

"My kids are successful, and happy, and believe in themselves," she said. "I don't have a single child in my room that has that look on their face like, 'I can't do this.' "

At the end of each school year, the Bethlehem school district gives kindergartners a test to assess early reading skills.

In 2015, before the new training began, more than half of the kindergartners in the district tested below the benchmark score, meaning most of them were heading into first grade at risk of reading failure. At the end of the 2018 school year, after the science-based training, 84 percent of kindergartners met or exceeded the benchmark score. At three schools, it was 100 percent.

Silva says he is thrilled with the results, but cautious. He is eager to see how the kindergartners do when they get to the state reading test in third grade.

He is eager to see how the kindergartners do when they get to the state reading test in third grade.

"We may have hit a home run in the first inning. But there's a lot of game left here," he says.

Emily Hanford is a senior correspondent for APM Reports, the documentary and investigative reporting group at American Public Media. She is the producer of the audio documentary Hard Words, from which this story is adapted.

https://www.apmreports.org/story/2018/09/10/hard-words-why-american-kids-arent-being-taught-to-read

What to do if the child does not want to learn to read: 3 tips

– I have been studying with the child for a long time, why doesn't he read?

- My reluctantly takes up a book, is capricious, looking for an excuse to evade.

- I have been studying with my daughter for several months, we go to school, but she still does not read and does not want to study.– I have been studying with my child for a long time, why doesn't he read?

- My reluctantly takes up a book, is capricious, looking for an excuse to evade.nine0004 - I have been studying with my daughter for several months, we go to school preparation, but she still does not read and does not want to study.

Despite the amazing opportunities that modern technology provides for education, parents often face a child's reluctance to study. But most of all it surprises in preschoolers 5-6 years old. - Where did it come from? After all, these are children, and they should be interested in everything new!

Schoolchildren's unwillingness to learn is, alas, a common symptom. In their case, the cause can be sought both within the family and outside: relationships with teachers at school, with classmates. In the case of preschoolers, there is only one reason - some mistake of parents in organizing classes, in relation to them. nine0012

Reading is a fun app for teaching children aged 3-7 to read

A colorful journey into the world of a fairy tale will allow your child to immerse themselves in the study of letters and syllables. Learning to read will no longer be a boring, routine task and will become a fun adventure to save the Magic Land. The game is based on the method of Zaitsev's cubes

Learning to read will no longer be a boring, routine task and will become a fun adventure to save the Magic Land. The game is based on the method of Zaitsev's cubes

In this article we will highlight 3 reasons why a child does not want to learn to read, and also offer 3 solutions. Pay attention to them, and your child's progress in learning will become more noticeable. nine0012

Why do we teach preschoolers to read?

If you open the school ABC, it will become clear to you that it was written for a child who is already reading. Gradually and imperceptibly, our children were no longer taught to read at school. For better or worse, the reasons why this happened are topics for a separate article. So we take it as a fact - the responsibility to teach the child to read and send it to school as a reader lies with the parents.

Therefore, parents not only teach their children to read, but try to succeed in it. They worry that if the child does not read well, then while the whole class will read the text and answer questions, their child will have difficulty connecting letters into words. This will lead to a backlog in other subjects. nine0012

This will lead to a backlog in other subjects. nine0012

From lagging behind to unsuccessful, and then to unsuccessful - no one wants such a development for a child. Therefore, parents try to prepare their children for school in advance, to prepare well.

To have more time and energy to adapt to new school realities. To make the child feel more confident, bolder, smarter. These are the correct and necessary arguments of loving parents. But what about children?

And with such an approach, they say that they are bored, incomprehensible, uninteresting... They begin to evade, avoid classes. They whimper, they whine. Parents force, insist, try to interest and sooner or later achieve results - the child goes to school as a reader. nine0012

Reason #1: Parents are chasing results and don't involve their child in the process

Adults require a result from a child - to be able to read fluently, to master the technique of reading. But they are not interested in the process itself (“I read because it is interesting”). In this case, the child will also be focused on the result over time (“I will read as much as you say, what you say and leave me alone”). For a child, reading becomes undesirable and even painful.

But they are not interested in the process itself (“I read because it is interesting”). In this case, the child will also be focused on the result over time (“I will read as much as you say, what you say and leave me alone”). For a child, reading becomes undesirable and even painful.

Thus, most parents strive to teach their child to read in order to prepare him for school, and formulate their task something like this: nine0012

“I teach a child to read so that in the first grade he feels no worse than others. To make it easier to adapt, get used to school, so that at first it would be easier for him to study.

At the same time, parents see the goal of learning to read as follows: the child knows letters, combines them into syllables, perceives the whole word, reads sentences. As a rule, having achieved this result, parents stop. They often stop when the child has gone to school, considering his task completed. nine0012

nine0012

But there is a second part of the “why am I teaching my child to read” problem that parents usually overlook. This is a long-term goal, the result of which is so far away that it can be overlooked. Here she is:

“I teach a child to read so that he loves reading”

A child who loves reading will read a lot and with interest, will learn much easier and faster to extract information from texts, understand different texts - artistic, scientific, informational, be able to analyze them, highlight the main thing. nine0012

Not noticing the second problem in learning to read is the same as not seeing the forest for the trees.

Therefore, in addition to achieving an immediate result, it is important to make sure that the very process of learning and reading gives the child pleasure. You read interesting books together (for preschoolers and elementary school), then the child begins to read books on his own, you help the child choose books according to age and interests, and discuss what he has read. Build an interest in reading before school, and support it in elementary and middle school. nine0012

Build an interest in reading before school, and support it in elementary and middle school. nine0012

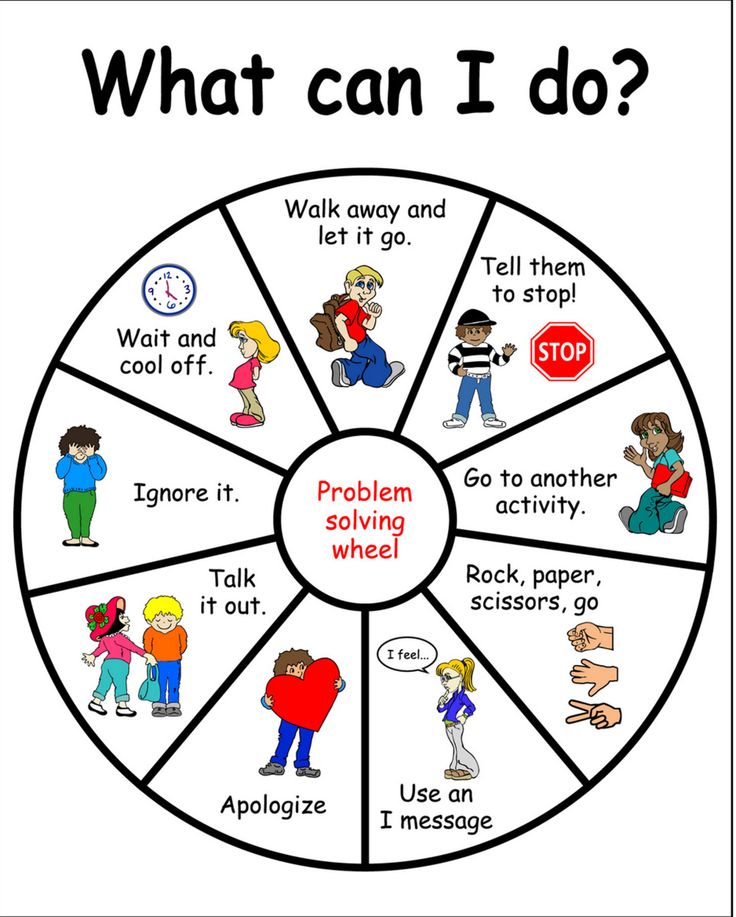

Solution 1: Switch to process. Remove controls and checks. Don't try to make sure that the child has learned, understood something in the technique of reading - all this is the desire to fix the result, the emphasis on which is now harmful for you and your child. Read books that are interesting to both of you as much as possible with your child, discuss them. The child should feel that reading is interesting.

Tatyana Chernigovskaya, a highly qualified specialist and scientist, talks about how to properly prepare a child for reading, so that he not only learns to read, but loves books with all his heart. nine0012

Reason #2: Adults underestimate the complexity of learning this task begins to seem to the child even more difficult than it really is.

It is not surprising that the child begins to avoid learning to read, and then to read in general.

It is not surprising that the child begins to avoid learning to read, and then to read in general. You learned to read a long time ago and most likely do not remember what difficulties you had in learning to read. You think learning to read is easy. And it's hard for a child. With their misunderstanding, skeptical attitude (“Yes, no one taught me at all, I learned it myself!”) Or pressure (“it’s time to read, soon to school!”) you unconsciously devalue the efforts of the child, thereby demotivating him and creating an attitude towards reading as something overwhelming and unpleasant. It is not surprising that subconsciously the child begins not want to learn to read and says: “boring, uninteresting, I don’t want to.” Science, by the way, confirms that learning to read is not easy. The scientists came to the conclusion that nine0012

learning to read is a complex cognitive process associated with the organization of memory, attention, and image manipulation.

Transforming them into a verbal-logical form and vice versa, decoding symbols (in the process of reading) into images, recognizing and manipulating them. Difficult, because different parts of the brain encode different information. The reading process involves departments that are responsible for processing sound and visual images, speech centers, short-term and long-term memory. There are about 17 areas of the brain in total. Each is responsible for its own area: one is for visual perception, the other correlates sounds and letters, the third recognizes the meaning of what is read. nine0012 T.V. Chernigovskaya, Doctor of Biological Sciences, neurolinguist

The rate of reading acquisition in children is determined by the rate of maturation of brain regions. This maturation occurs unevenly (heterochronously). Such uneven development is the norm for a child. As on a fruit tree, all the flowers do not bloom and all the fruits do not ripen at the same time.

Heterochrony of development partly explains the fact that often children in a certain period know the letters and they cannot or cannot read words to combine them into syllables - everything has its time. Just be flexible and be sympathetic to these temporary difficulties. nine0012

It is also worth adding that in addition to the heterochronous development of brain regions, which is relevant for everyone, Your child may have their own learning curve. To be equal to other children, to the opinion of specialists, of course, it is necessary, but do not attach too much importance to this. It will be right not to drive your child into someone else's framework, and notice, find its strengths and weaknesses. And in the future to use them for study, to reveal its development potential.

Solution 2 Be patient. Support the child. Instead of stressing that learning to read is easy, focus on that you believe and have no doubt that he will learn to read. Rejoice in every achievement.

Rejoice in every achievement.

If the child fails to learn to read quickly, if he has difficulties, do not discuss with relatives, especially in front of the child. After all, he hears everything and subconsciously adjusts to the ideas of his loved ones - mom and dad. Believe in the potential of the child and this belief will transform him amazingly, and your relationship will only benefit. whenever it seems to you that “he should have read a long time ago”, “I myself learned at his age ...”, remember the complexity of the task and the physiological conditions of the child's readiness. Switch to the process - and engage with your child for your pleasure. Yes, yes, just for fun. You should also be interested in activities with the child. nine0012

Be able to see the value for yourself in these activities! How? Look at your classes from a different angle. Your child is learning a difficult reading skill... But at this moment you are mastering an equally complex skill: you are learning to understand its capabilities and not to rush. This skill will be needed in the school period, and in adulthood. Observe the child, learn his features, overcome the first educational difficulties with him. So in a sense, you and your child have the same goal. nine0012

This skill will be needed in the school period, and in adulthood. Observe the child, learn his features, overcome the first educational difficulties with him. So in a sense, you and your child have the same goal. nine0012

Reason #3: The chosen method is not suitable for your child

An inappropriate teaching method that does not correspond to age characteristics will greatly slow down the process of learning to read. We are far from opposing sound and warehouse methods. A lot of literature has been written in defense of each of them. But if you notice that the child's problems in relation to reading are connected precisely with a misunderstanding of what you are explaining to him, it is likely that that you are facing this problem. nine0012

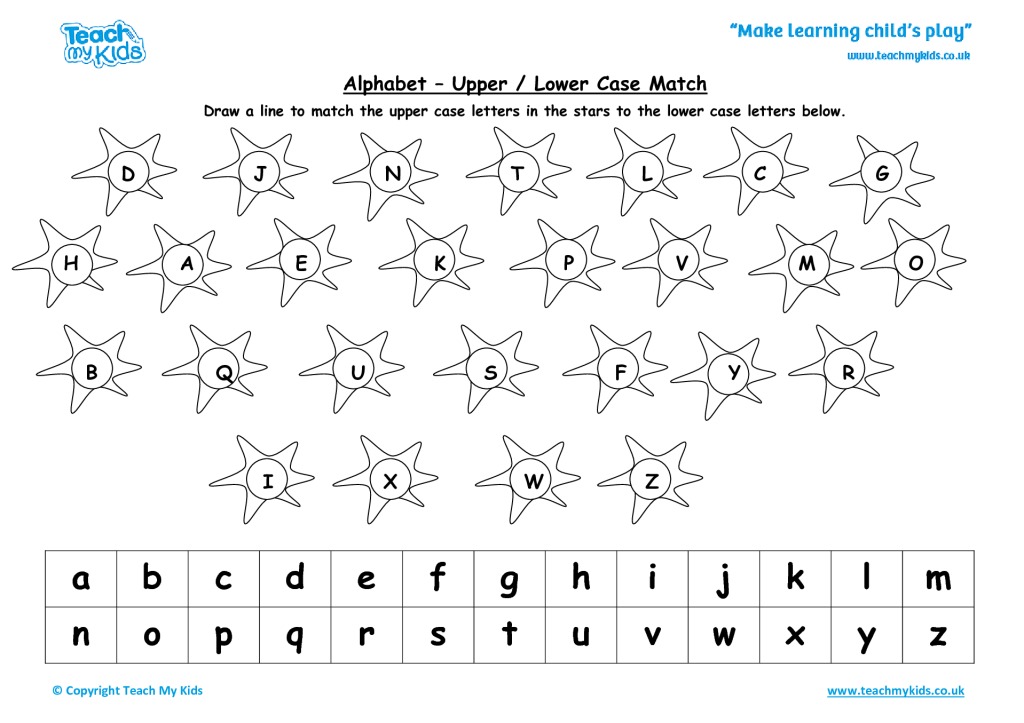

Read about the difference in methods of teaching reading in our article "How to teach a child to read". Here I will briefly say that the most common are two principles of teaching children to read: storage and sound. In addition to them, there are learning to read in whole words and other approaches, but here we will focus only on these two.

In addition to them, there are learning to read in whole words and other approaches, but here we will focus only on these two.

Russian people have been taught to read since antiquity. Gradually, the warehouse method became simpler. A warehouse is 1 or 2 letters (a consonant plus a vowel). This is how the words divided into warehouses will look like: s-to-l, ka-r-ti-na, a-r-bu-z, se-m-i. nine0012

- Skladovoi method in teaching children was used by L.N. He arranged warehouses in the table and on the faces of the cubes (Zaitsev's cubes). All warehouses are known, the child looks, writes, plays and gradually remembers them. Such training is suitable for younger preschoolers: the warehouse is perceived, remembered and pronounced by the child as a whole. When pronouncing warehouses in sequence, the whole word is obtained. nine0105

- The sound (phonetic) method of teaching reading was borrowed by the Russian nobility in the second half of the 19th century from the German language.

In it, each letter (more precisely, the sound) is strung like beads on a string to each other. This method was taken as a basis, developed and modified by Soviet pedagogy. If you send your child to prepare for school in a school, they will teach him in this way. With this approach, individual letters (sounds) are memorized, with the help of which the child learns to compose and parse words. nine0105

In it, each letter (more precisely, the sound) is strung like beads on a string to each other. This method was taken as a basis, developed and modified by Soviet pedagogy. If you send your child to prepare for school in a school, they will teach him in this way. With this approach, individual letters (sounds) are memorized, with the help of which the child learns to compose and parse words. nine0105

To learn to read by the sound method, the child must grow up. Analytical-synthetic functions of the brain necessary for teaching a child by this method (analyze the word, decompose it into sounds and synthesize them back into a word) arise in a child after 6-7 years. So it is only natural that children may have difficulty with this.

In addition, it is important for preschool children to play. The game is their age feature. It is important not to deprive the child of this need for the sake of classes. nine0012

Solution 3 Take a break from classes for 1-2 weeks, and then try another method, other aids. Embed your activities into the game, or vice versa - the game into the activities. Imagine, invent, try.

Embed your activities into the game, or vice versa - the game into the activities. Imagine, invent, try.

Reading - a fun app for teaching children aged 3-7 to read

A colorful journey into the world of a fairy tale will allow your child to immerse themselves in the study of letters and syllables. Learning to read will no longer be a boring, routine task and will become a fun adventure to save the Magic Land. The game is based on Zaitsev's cube technique. nine0012

Conclusions

- Emphasize process in learning. Be aware that learning to read can take time. Let other parents brag about “how their child quickly learned to read,” and your task is to learn to understand your child, notice its strengths and weaknesses. Share the fun of mastering this first difficult learning skill (the child learns to read and you learn to teach the child). The main thing is that every time you sit down to study, remember: you are not teaching a child to read, you are teaching him to love reading.

From this simple installation, everything you do will change. nine0105

From this simple installation, everything you do will change. nine0105 - Be patient. Support the child. Instead of stressing that learning to read is easy, focus on that you believe and have no doubt that he will learn to read. Rejoice in every achievement.

- Choose the method of teaching reading, as well as the degree of play presentation of the material in accordance with the age of the child. If something does not work out, take a break from classes and try other methods.

It is important not only to teach a child to read, but also to instill in him a love of reading. In the video, the author of the project on education and upbringing of children, Nadezhda Papudoglo, talks about how not to discourage a child's love of books and how to help him fall in love with reading. nine0012

In all incomprehensible cases, the game for learning to read READING will help you, which was created for the child to play and learn to read by himself, moving forward with interest and desire.

Successful teaching practices with children!

Natalia Sosnina

Co-author and methodologist of the Readings educational application. Since 2016, together with her husband and children, they have been developing a game to make learning to read interesting and understandable. The application is based on N.A. Zaitsev. In her free time she likes to spend time with her family and travel. nine0012

Learn more about Natalia on VK, Instagram and the Readings YouTube channel.

Our other articles

- How to teach a child to read

- Whole word reading method

- Nikolai Zaitsev's technique

- Maria Montessori Method

- The child has learned and repeats bad words, how to behave?

- When to start teaching a child to read

- A preschooler does not want to learn to read. What to do?

- What is the most important and difficult thing in preparing for school? nine0105

- Development of spatial thinking of a child

- 5 Best Practices for Teaching Reading to Preschoolers

- 3 Best Alphabet Learning Games

- Learning the alphabet for children in a playful way

Is it necessary to teach a child to read before school and how is this related to the further reading literacy of children?

A study by our colleagues in the Laboratory showed that educational inequality manifests itself even before school. This is due to how differently they deal with children in families with different levels of cultural capital. nine0012

This is due to how differently they deal with children in families with different levels of cultural capital. nine0012

firestock

Many schools now have an unwritten rule that children must be able to read by the first grade. But visiting kindergartens in our country is not mandatory. In addition, the problem of their availability is also far from being solved everywhere. Therefore, this difficult task - the formation of early reading literacy - falls on the shoulders of parents.

Andrey Zakharov and Anastasia Kapuza, members of the International Laboratory for Education Policy Analysis, decided to take a closer look at this issue and find out exactly how parents teach children to read in different families and what results these efforts bring. nine0012

Kapuza Anastasia Vasilievna

International Laboratory for Education Policy Analysis: Intern Researcher

We conducted a study based on the data of international monitoring PIRLS, which took place in 2011. It was attended by 4461 fourth-graders from 202 Russian schools. We were interested in how the level of literacy of children at school entry and in the 4th grade is associated with the cultural capital of the family, attendance at kindergarten, and various reading teaching practices used by parents with different levels of education. nine0012

It was attended by 4461 fourth-graders from 202 Russian schools. We were interested in how the level of literacy of children at school entry and in the 4th grade is associated with the cultural capital of the family, attendance at kindergarten, and various reading teaching practices used by parents with different levels of education. nine0012

How parents teach their children to read before school

Ways of teaching reading can be divided into formal and informal. Formal ones are more focused on the mechanics of the reading process. That is, on the perception and pronunciation of letters, syllables and words. For example, this is learning the alphabet or playing with words. In informal practices, more attention is paid to the comprehension of texts - this is the joint reading and discussion of books.

Andrey Zakharov

Deputy Head of the International Laboratory for Education Policy Analysis

In general, parents with higher education are more likely to start teaching their children to read before school. Moreover, strategies for engaging with children are also related to the level of education of parents. The longer a child goes to kindergarten, the more often parents without higher education work with him. That is, such children are taught to read both in the garden and at home. At the same time, parents more often use the whole diverse set of practices: both formal and informal. We called this approach “reinforcement strategy” . We assume that this strategy is a response to requests from kindergarten teachers who encourage parents to engage with their children.

Moreover, strategies for engaging with children are also related to the level of education of parents. The longer a child goes to kindergarten, the more often parents without higher education work with him. That is, such children are taught to read both in the garden and at home. At the same time, parents more often use the whole diverse set of practices: both formal and informal. We called this approach “reinforcement strategy” . We assume that this strategy is a response to requests from kindergarten teachers who encourage parents to engage with their children.

But parents with higher education use “compensation strategy” . In such families, they are more involved with children if they do not go to kindergarten. Moreover, such parents use predominantly informal practices - they try to instill in the child an interest in reading, are engaged in language development and general education. nine0012

The more often parents work with their children before school, the higher the level of reading literacy of children - both when they enter the first grade, and later, in the 4th grade. For children from families with a large amount of cultural capital, an increase in the level of reading literacy is associated with the use of informal practices by parents. But parents without higher education can apply any practice - the results of children will only get better.

For children from families with a large amount of cultural capital, an increase in the level of reading literacy is associated with the use of informal practices by parents. But parents without higher education can apply any practice - the results of children will only get better.

Reading Literacy and Kindergarten

A child's progress in reading also depends on whether he attended kindergarten. This is very important for families with little cultural capital. The longer a child goes to kindergarten, the better he reads when entering school. This is due to the combined effect of the joint efforts of teachers and parents.

But for children from families with a large amount of cultural capital, the duration of kindergarten attendance is not critical for their level of reading literacy.

- The compensation strategy probably works, the researchers conclude. - Parents with higher education compensated for the absence of a kindergarten by studying at home. nine0012

nine0012

As a result, children from families with low cultural capital, who did not go to kindergarten, find themselves in the most difficult situation. They are less likely to learn to read by grade 1, because neither teachers nor parents teach them. Such children are more likely to lag behind their peers in the classroom at school.

Parental support for children's reading in the 4th grade

Of course, schools do not leave children with poor reading skills unattended. They are trying to somehow influence families. Parents without higher education are more likely to join classes with children in the 4th grade. Apparently, under the pressure of the school (on average, students from such families read worse), such parents begin to pay more attention to reading to children and discussing what they have read with them. But in 4th grade it may be too late for that. nine0012

- We were surprised to see that frequent activities with children in the 4th grade were negatively associated with their reading literacy, the researchers say. - At first they didn't even believe it, so they made the same analysis for other PIRLS member countries. In many countries, the trend has repeated. This is explained by the fact that by the fourth grade children should already be able to read, and if they have to constantly do extra work with them at this age, it means that they have problems with reading.

- At first they didn't even believe it, so they made the same analysis for other PIRLS member countries. In many countries, the trend has repeated. This is explained by the fact that by the fourth grade children should already be able to read, and if they have to constantly do extra work with them at this age, it means that they have problems with reading.

Outgoing train

On the example of reading, we see that the strategies for teaching children, which are chosen by parents with different amounts of cultural capital, give different results:

Parents with higher education are involved in the education of children before school. They are like passengers who come to the train in advance and take good seats. As a result, their children show a higher level of reading literacy both when they enter the 1st grade and the 4th grade. Parents without higher education prefer to delegate the function of teaching to school. They are connected only when teachers begin to draw their attention to the need to work with children.