Sentences for kids

How To Make The Most Of Simple Sentences For Kids

When a child finally learns how to construct their own simple sentences, for kids (and parents!), it’s a really special moment.

Word combinations such as “knee sore” turn into, “Mommy, my knee is sore.” Or “now juice” develops into, “Can I have some juice?”

There’s no denying the importance of sentences — they help us better express our thoughts and feelings. So the only question now is: How can you help your child start constructing their own sentences so that they, too, can communicate better?

Two words: simple sentences.

When Do Kids Start Forming Sentences?

Children start forming sentences once they know a few words. But language development is quite a journey!

Somewhere between 18 and 24 months, a toddler will begin constructing two-word “sentences,” like “want milk” or “no sleep.” At this stage, they are linking two or more words together to express an idea. This is the first step and a big milestone.

By four years old (sometimes earlier), most children are speaking in complete sentences. But that doesn’t mean they’ve reached the end of their sentence journey.

While your child may be speaking in complete sentences, finding playful ways to expose four and five year olds to sophisticated aspects of sentences while being kid appropriate is beneficial. This will help them continue developing their language skills.

One of the best ways to do so is to encourage children to speak in complex sentences to express their ideas. How? This can be achieved by simply resisting the temptation to simplify our own speech.

Remember that children are learning sponges! They will naturally pick up on the language habits you expose them to. So, continue speaking in complex sentences while in their presence. It’s not a bad thing if your child asks, “What does that mean?”

Of course, simple sentences come first.

What Makes A Simple Sentence?

A simple sentence is the most basic form of a sentence. It contains only one independent clause — a group of words that forms a complete thought and is made up of a subject and predicate (which includes a verb and expresses what is said about the subject).

It contains only one independent clause — a group of words that forms a complete thought and is made up of a subject and predicate (which includes a verb and expresses what is said about the subject).

For example, in the simple sentence, Thomas kicks the ball, “Thomas” is the simple subject and “kicks the ball” is the predicate, with “kicks” being the verb, or simple predicate.

Simple sentences for kids are mostly short, but they can also be long. The length of the sentence isn’t the focus. What’s important is that the basic elements (subject and predicate) are always present.

When we communicate in our everyday lives, there’s usually a good mixture of both simple and more complex sentences without us even thinking about it. In order to help our kids reach this effortless communication stage, we need to help them understand the basics.

The good thing about the English language (and every other language, actually!) is that once you understand the basics, moving on to complicated structures is easier.

Simple Sentences For Kids To Act Out

One of the best ways for children to learn is through acting things out. If you have an active young child who enjoys moving around, why not use their energy to encourage some learning?

Here are some simple sentences for kids they will have fun acting out.

- He reads a book.

- The dog barks.

- The cat sits on the mat.

- I hop on one foot.

- The pig gobbles his food.

- The rooster crows.

With these sentences for kids, your child will have a blast while naturally learning what makes up a sentence!

Other Ways To Practice Sentences For Kids

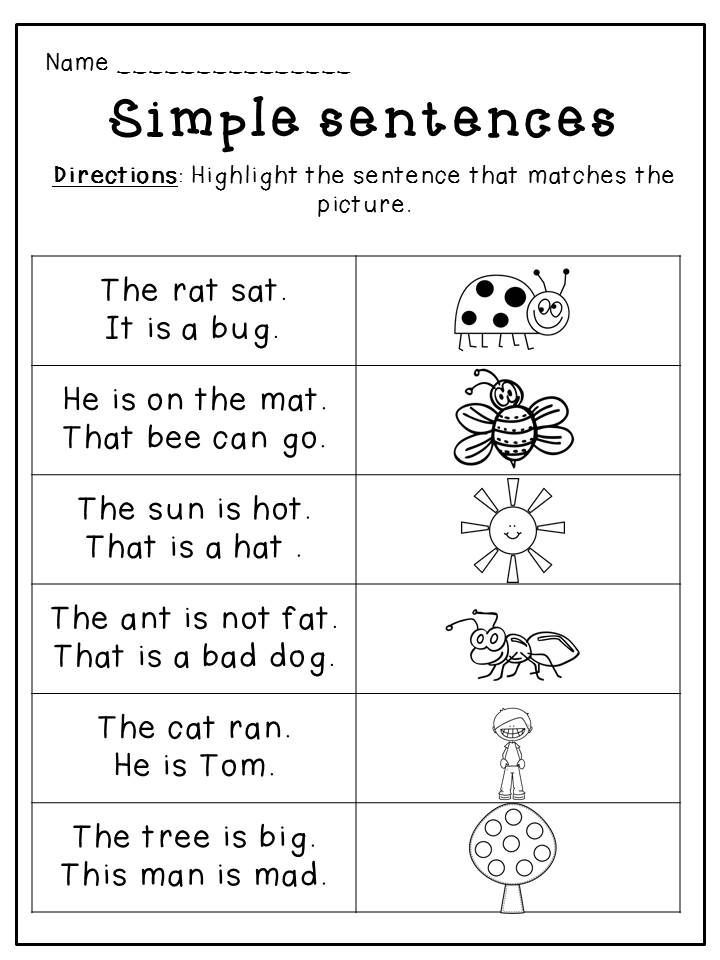

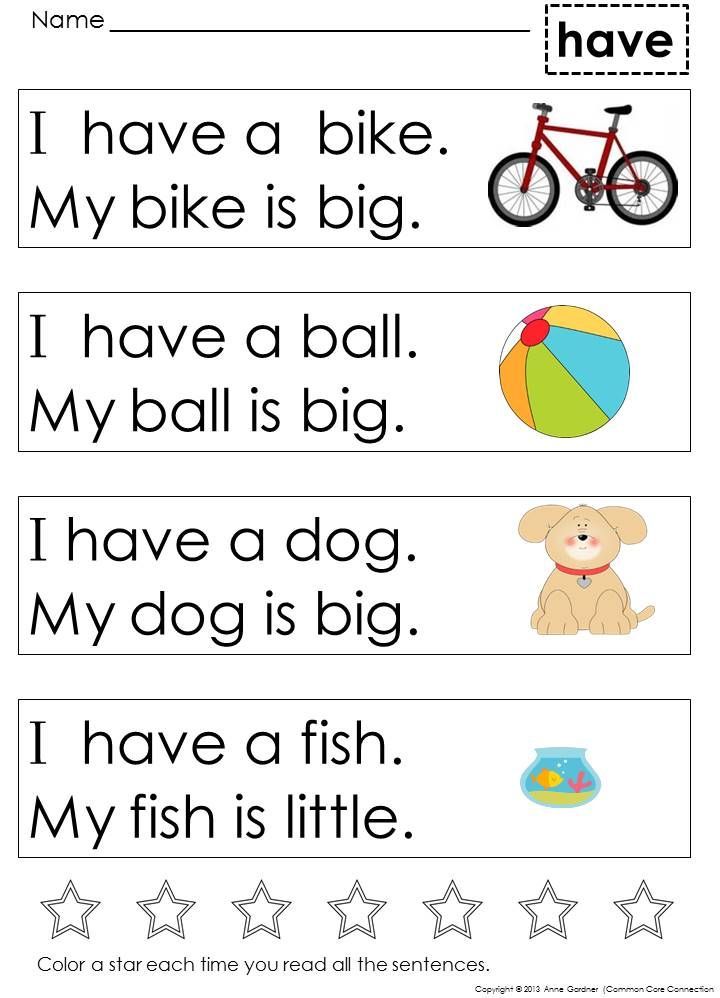

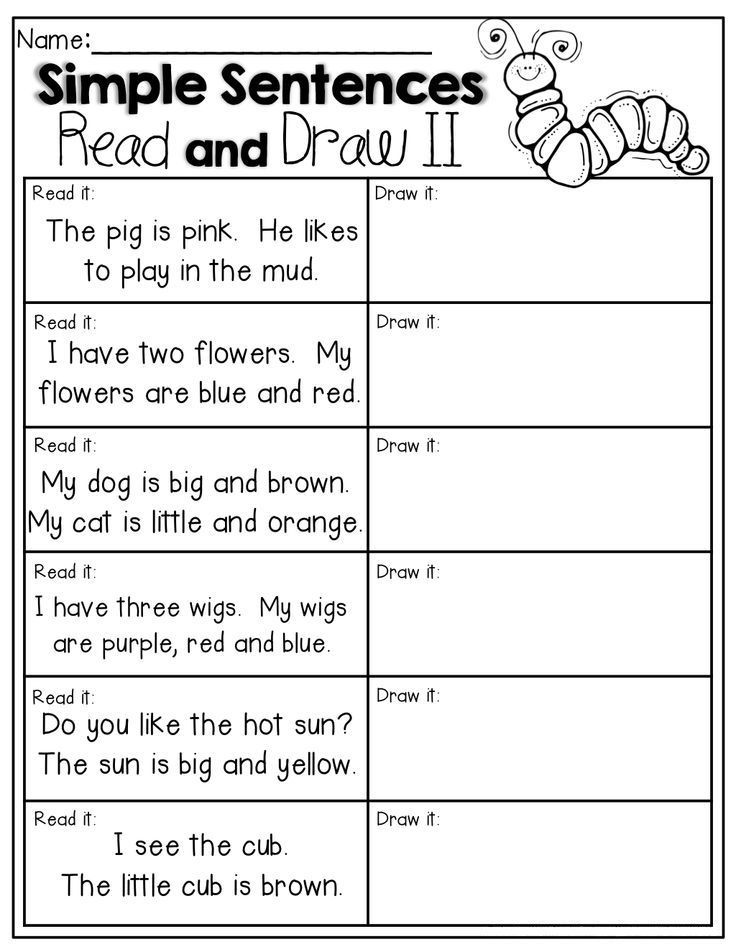

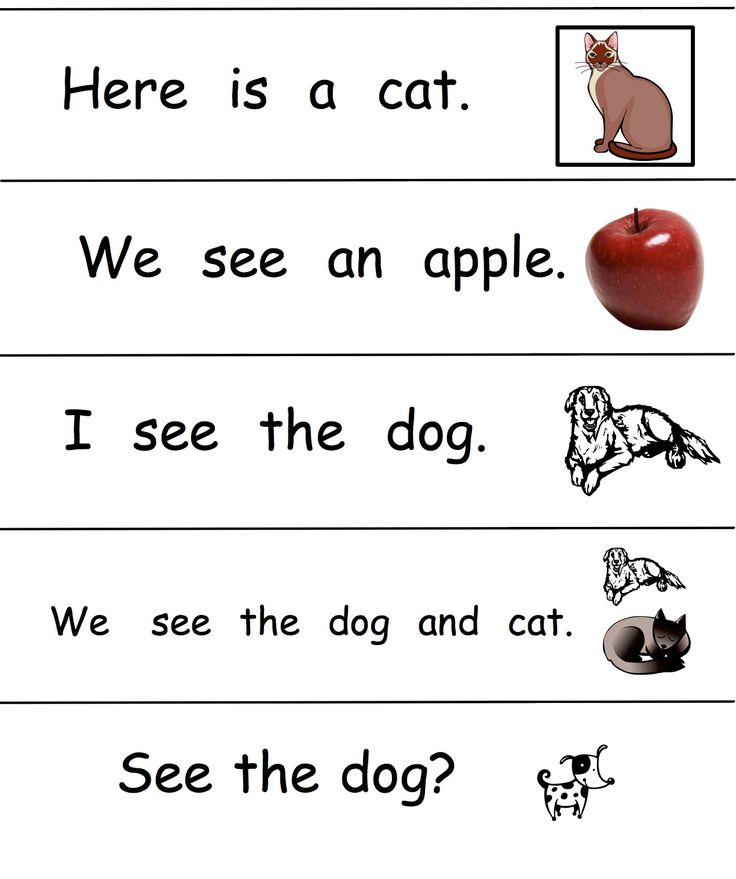

1) Use Pictures

We recommend having your child use pictures to make up stories. You can even record the stories and listen to them for a little added fun!

If your child wants to write their ideas, too, that’s great! But don’t worry about standard spelling; much more important is the creative effort involved in thinking of a great story composed of interesting sentences of their own creation.

You can use pictures of animals, nature, sports, or even family photos. Then encourage your child to share whatever comes to their mind after having a look at these images.

During the first session, your child may need a few verbal prompts to help them get started. Simple questions like, “What’s happening in the picture?” or “What does this image remind you of?” can help to get their creativity flowing.

If you have multiple children, you can allow them to share what they came up with about the same image. As individuals, they will most likely think of different sentences, so this is a great opportunity to emphasize how everyone has unique ideas.

We encourage you to allow your children creative freedom here. The idea is to place an image in front of them and let them create anything they feel like creating.

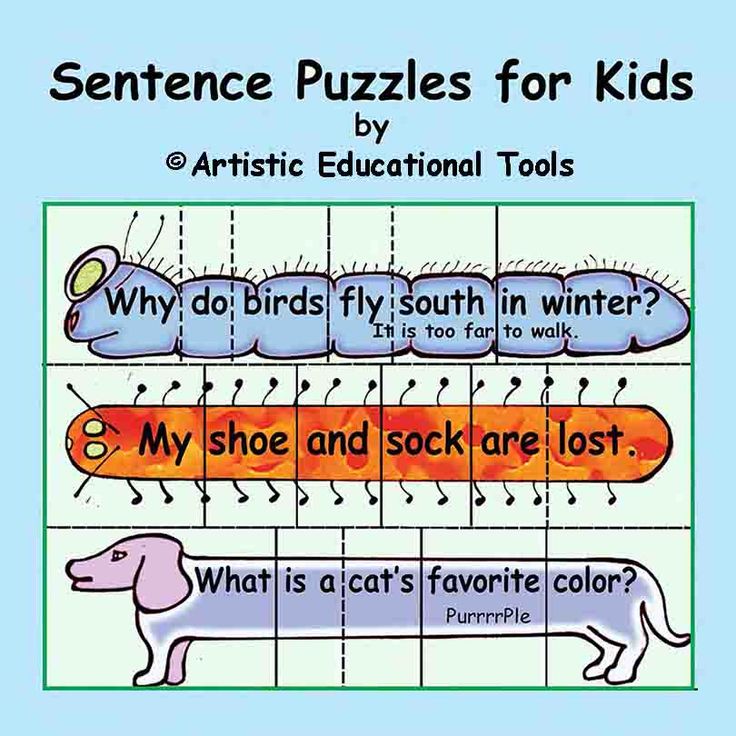

2) Play Sentence Games

If you’ve been following our blog for a while, you’ll know one thing for sure — the HOMER team loves a good game! Games are not only fun, but they’re also great ways to help children remember fundamental learning concepts.

One of our favorite sentence games is Sentence Mix & Match.

What You’ll Need:

- Several index cards

- Markers to write with

What To Do:

- Write interesting subjects on half of the index cards (Ideally, these are things that your child likes. For example: dinosaurs, ice cream, different shapes, colors, etc.).

- On the other half, write predicates or sentence endings that make sense with your individual subjects.

- After writing, place the cards so that they make realistic sentences.

- Then, turn all the cards over and shuffle them. At this point, you want to ensure that you separate sentence beginnings and endings.

- After the shuffle, turn your cards over and discover what silly sentences you get.

- Remember to begin the subject cards with capital letters and sentence-endings cards with a period.

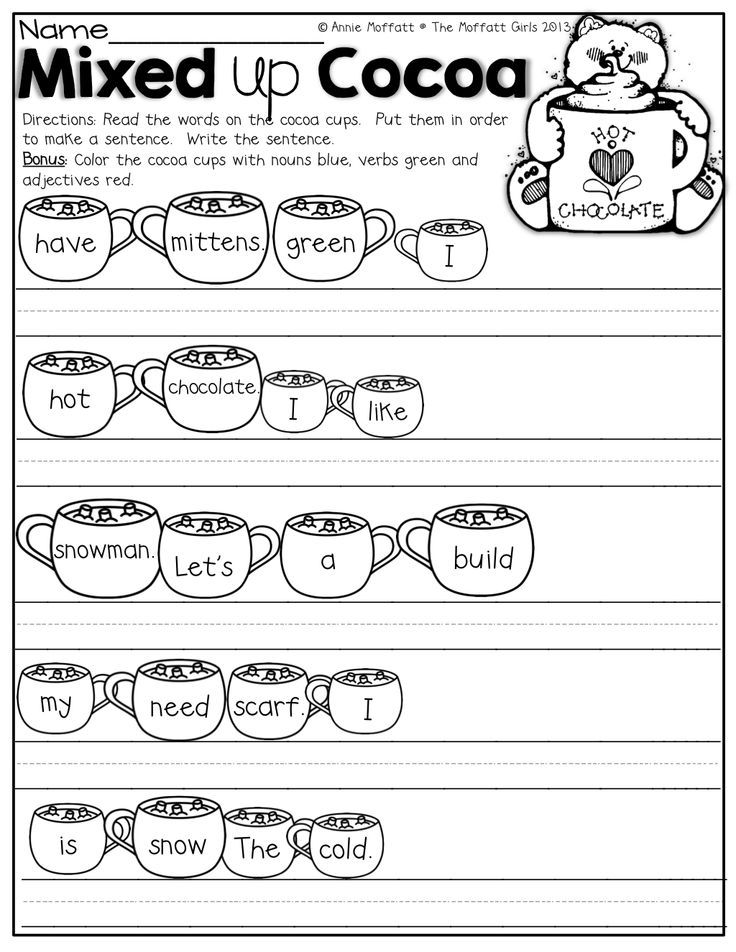

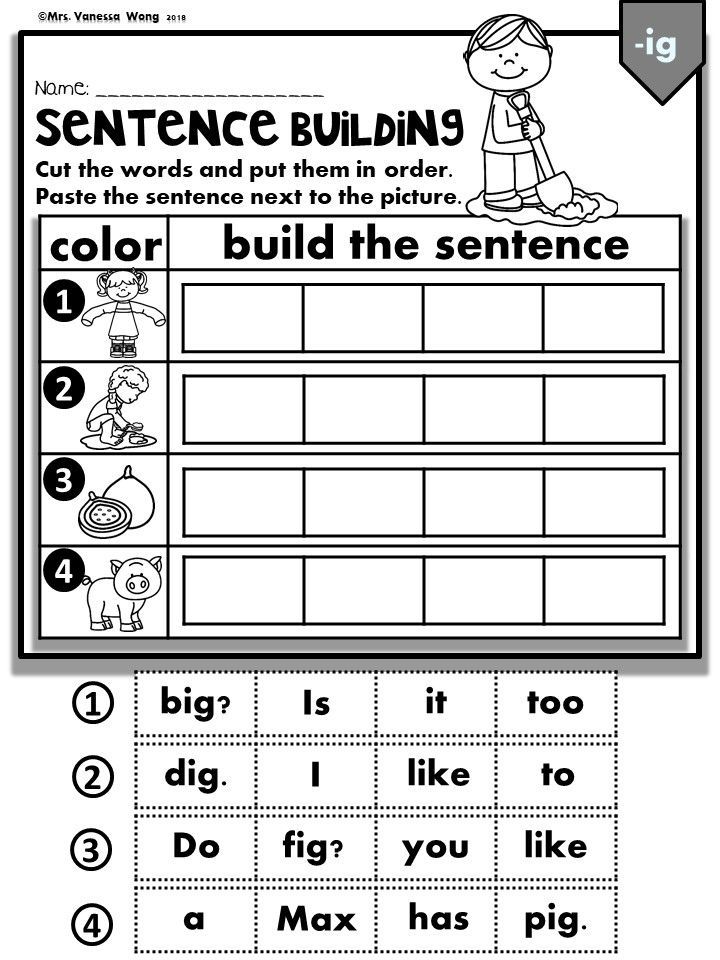

This is a fun activity to help children see that sentences are not always set in stone. They will also quickly learn that the meaning of a sentence can change when words get moved around.

3) Play With Types Of Sentences

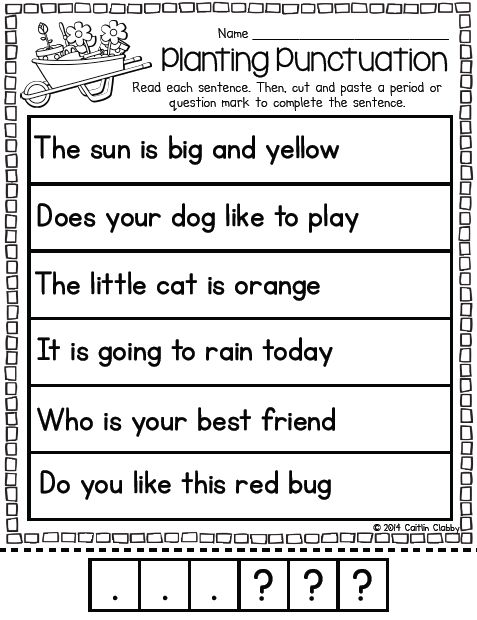

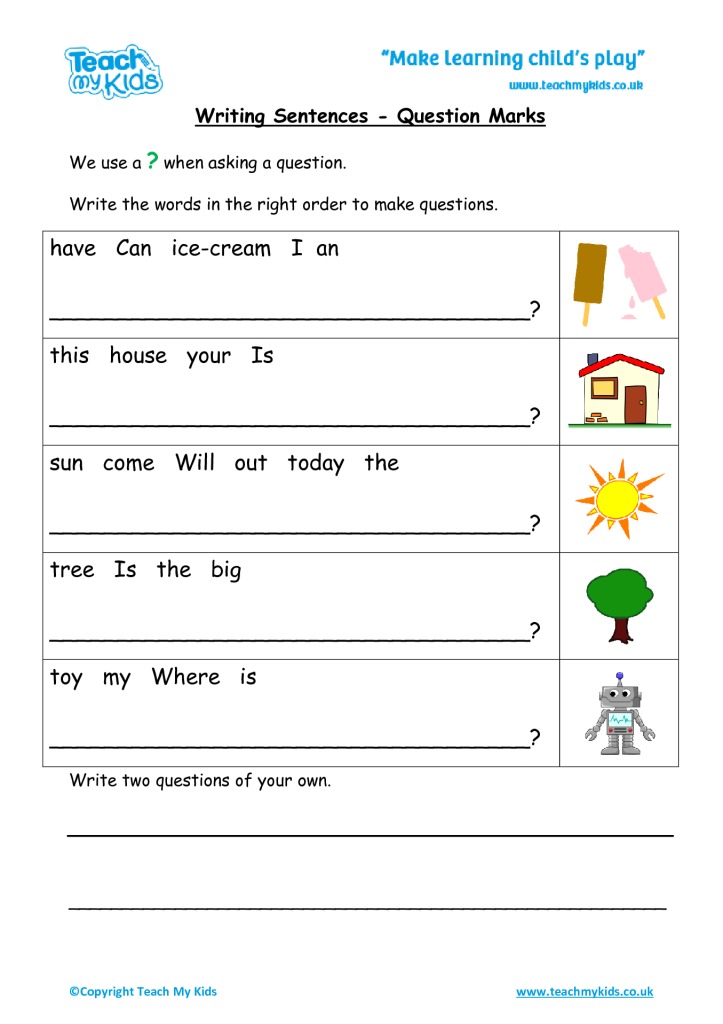

Sentence Mix & Match is not the only way to help children learn sentences for kids while also having fun. Another activity we’re huge fans of is playing with types of sentences. Specifically — statements, questions, and exclamations.

To get started, pick any simple sentence that your child will already be familiar with (e.g., “I like playing outside.”).

Next, encourage your child to say this same sentence as a statement, a question, and then an exclamation.

Similar to Sentence Mix & Match, this game helps children understand that minor tweaks can change the meaning of a sentence.

Children will come across punctuation marks during reading time, but they may not always understand the significance of each. This game will help your child learn how periods, question marks, and exclamation points affect a sentence.

5) Make A Switch

The subject and predicate for each simple sentence have a specific function. For children to use these correctly, they will need to understand what their roles are.

For children to use these correctly, they will need to understand what their roles are.

When kids start speaking as babies and then toddlers, they often repeat words, phrases, or the simple sentences they’ve heard from you, your partner, siblings, or other people around them.

At this stage, they haven’t fully grasped the functions of subjects and predicates. If we want to help our children develop their own sentences, we will need to help them understand the roles of these sentence parts.

A creative game they (and you!) will enjoy involves switching the subjects and predicates of a sentence.

Start with a simple three-word sentence, like, “A cat played.” Then take turns changing either the subject or the predicate of the sentence.

This may look something like this:

- A cat jumped

- A dog jumped

- A dog growled

- A gerbil growled

- A gerbil scampered

Once your young learner is confident switching three-word sentences, move on to four words, five words, and so forth.

Through this fun activity, your child will start understanding the roles of predicates and subjects in sentences.

Simple Sentences For The Win!

A child’s language journey is pretty incredible. It often starts with lots of babbling and moves to single words. Soon, you get two-word combinations, and before you know it, you’re given a detailed account of what happened in class today.

As you’re doing the activities we’ve mentioned, remember to allow your child creative freedom. We know that language has a lot of rules, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be fun! Encourage your young learner to be as imaginative as they want to be.

For instance, if they write or say, “The lion growls at the dinosaur,” let’s celebrate the correct sentence construction and, for a moment, imagine a world where lions and dinosaurs exist in the same age!

For more fun and effective learning activities, check out the HOMER Learn & Grow app.

Author

Teaching Kids How to Write Super Sentences

How do you encourage your students to write longer, more interesting sentences? You know what will happen if you simply ask them to write longer sentences… they’ll just add more words to the end, resulting in long, rambling run-ons!

After struggling with this problem myself, I developed a method that helped my students learn how to turn boring sentences into super sentences. I began by teaching them the difference between fragments, run-ons, and complete sentences. Then we practiced revising and expanding basic sentences to make them more interesting. After I modeled the activity and they practiced it in a whole group setting, they played a game called Sentence Go Round in their cooperative learning teams. The difference in their writing was dramatic! Before long, they were adding more detail to their sentences without creating run-ons in the process.

I began by teaching them the difference between fragments, run-ons, and complete sentences. Then we practiced revising and expanding basic sentences to make them more interesting. After I modeled the activity and they practiced it in a whole group setting, they played a game called Sentence Go Round in their cooperative learning teams. The difference in their writing was dramatic! Before long, they were adding more detail to their sentences without creating run-ons in the process.

Step 1: Mini-Lesson on Sentences, Fragments, and Run-ons

Begin by explaining that complete sentences can be short or long, but they must have two basic parts, a subject and a predicate. The subject tells who or what the sentence is about, and the predicate is the action part of the sentence, or the part that tells what the subject is doing. If it’s missing one of those parts, it’s a fragment. If it has a whole string of sentences that run on and on without proper punctuation, it’s a run-on sentence.

Next display a series of phrases or sentences and ask your students to decide if each on is a fragment, a complete sentence, or a run-on. Try these:

- Rabbits hop. (Your students will say it’s a fragment since it’s so short, but it’s actually a complete sentence.)

- The big brown fluffy rabbit in the garden. (Looks like a sentence, but it’s missing a predicate.)

- Rabbits love to eat carrots and one hopped into our garden and I thought it was cute even though it was eating the carrots. (A run-on of course … kids don’t usually have trouble spotting these, but you might want to have them find all the subjects and predicates to make your point.)

- The hungry rabbit hopped into the garden because he wanted to eat a carrot. (Even though this one is long, it’s not a run-on because it only had one subject and one predicate.)

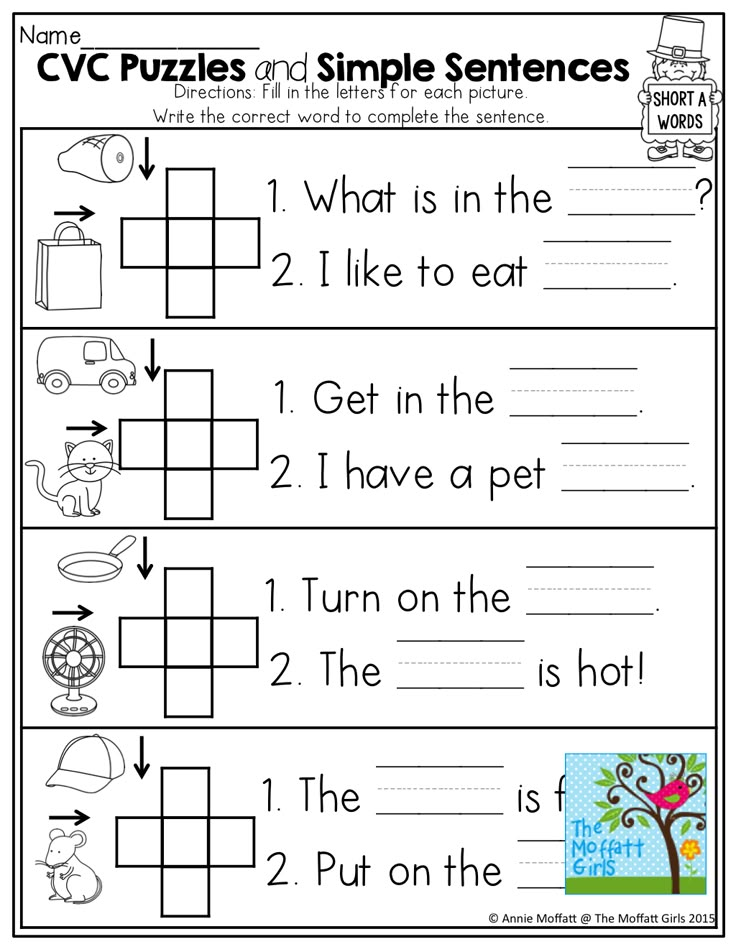

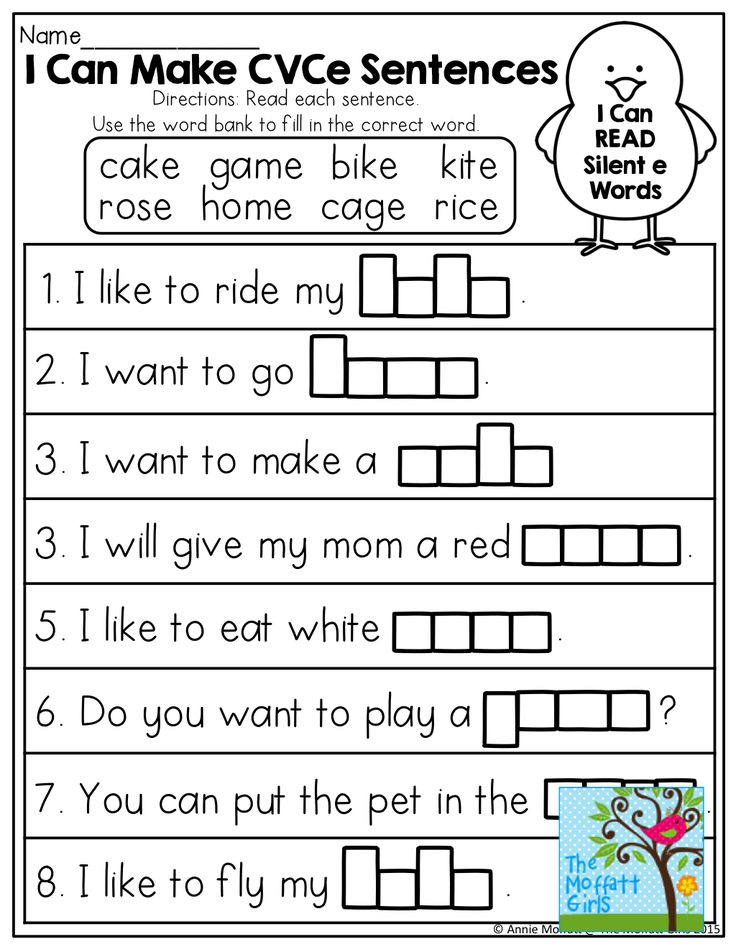

Step 2: Mini-Lesson on Revising & Expanding Sentences

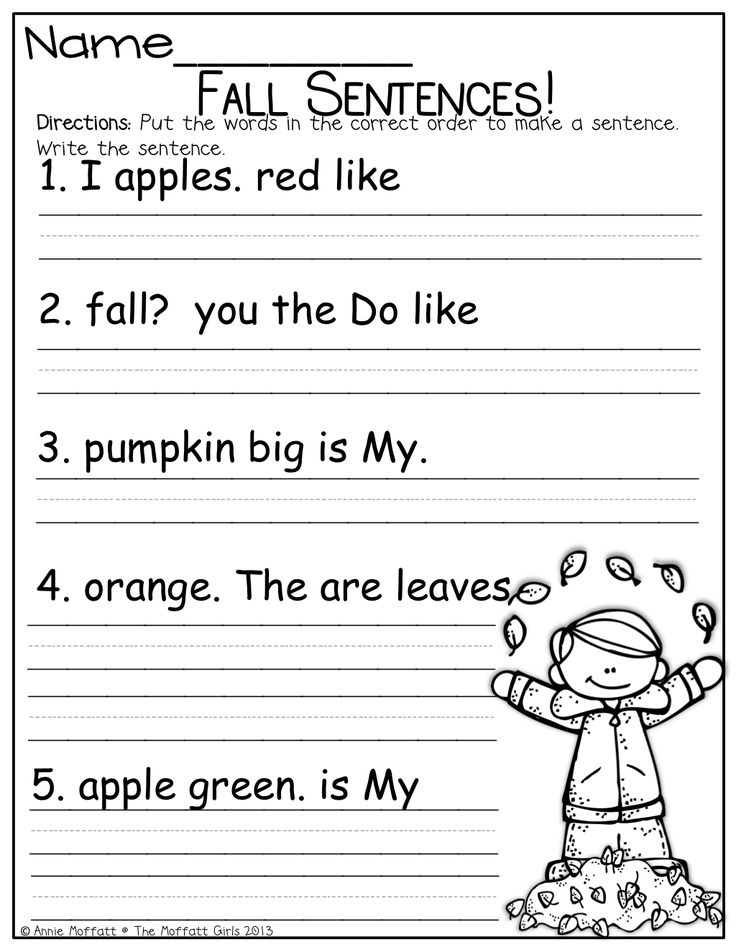

After your students can distinguish between fragments, run-ons, and complete sentences, it’s time for them to practice their sentence-writing skills by learning how to revise and expand basic sentences. This activity should be modeled in a whole group or guided literacy group first, and older children can do the activity later in cooperative learning teams. To start the activity, you need a set of task cards with basic sentences that lack detail. I used an example from the Fall Sentences to Expand freebie for this lesson, but you can use task cards from any of the seasonal freebies below.

This activity should be modeled in a whole group or guided literacy group first, and older children can do the activity later in cooperative learning teams. To start the activity, you need a set of task cards with basic sentences that lack detail. I used an example from the Fall Sentences to Expand freebie for this lesson, but you can use task cards from any of the seasonal freebies below.

Whole Class Modeling:

- Start by selecting a basic sentence from the Fall, Winter, Spring, or Summer task cards above. Let’s use the fall-themed sentence, “She picked apples.” Write the sentence on the board or show it to the class using a document camera.

- Explain that “She picked apples” is boring, but if we ask ourselves questions about it, we can add details that answer the question and make it more interesting. For example, if we ask “Who picked apples?” we can name someone specific. Demonstrate how to make the change as shown below.

- It’s still a boring sentence, so let’s ask, “How many?” and say that Mary picked a dozen apples.

- Go through the same process, each time repeating the revised sentence and asking another question. After 4 rounds of changes, it might look like the one in step 4 below.

Whole Class Interactive Lesson:

- Next, repeat the process and actively involve your students. Ask one student to randomly select a sentence card and write it on the board.

- Then ask all students to think about a question they could ask and how they could revise the sentence to add one detail. It can be more than one word, but it shouldn’t be more than a short phrase that answers that question. If all students have individual dry erase boards or chalkboards, ask them to write down their revisions and show them to you.

- Call on one student to come forward and display his or her revised sentence.

- Repeat the process three or four more times until you’ve created a sentence that’s detailed and interesting, but not a run-on.

Modification Idea: If you notice that some students are creating run-on sentences, ask everyone to pair with a partner before sharing with the class to make sure all sentences are complete sentences.

Step 3: Cooperative Learning Writing Activity

The first two steps are the perfect segue into Sentence Go Round, an activity for cooperative learning teams or small groups to practice expanding sentences. The product below includes sample sentences for the teacher to display, as well as printables for students and a sorting activity to practice identifying fragments, run-ons, and complete sentences. Sentence Go Round also includes activity directions and question cards to prompt students as they are creating their new sentences. To preview the entire resource, click over to see Sentence Go Round in my TpT store.

Step 4: Google Classroom Sentence Writing Practice

It’s important to follow up with independent practice, so I’ve created some Google Classroom resources to supplement the cooperative learning, hands-on activities in Sentence Go Round. Sensational Sentences: Sentence Writing Practice includes a Google slide presentation to introduce the concepts, 2 digital sentence sorting activities, 2 self-checking Google Quizzes, 2 sentence writing activities, and 3 editable templates.

If you want to use the cooperative learning activity Sentence Go Round AND the Google Classrooms materials, check out my Sensational Sensational Sentences Bundle which includes both resources at a discounted price.

I hope your students enjoy these lessons and Sentence Go Round as much as mine did, and that they will soon be writing super sentences instead of boring ones!

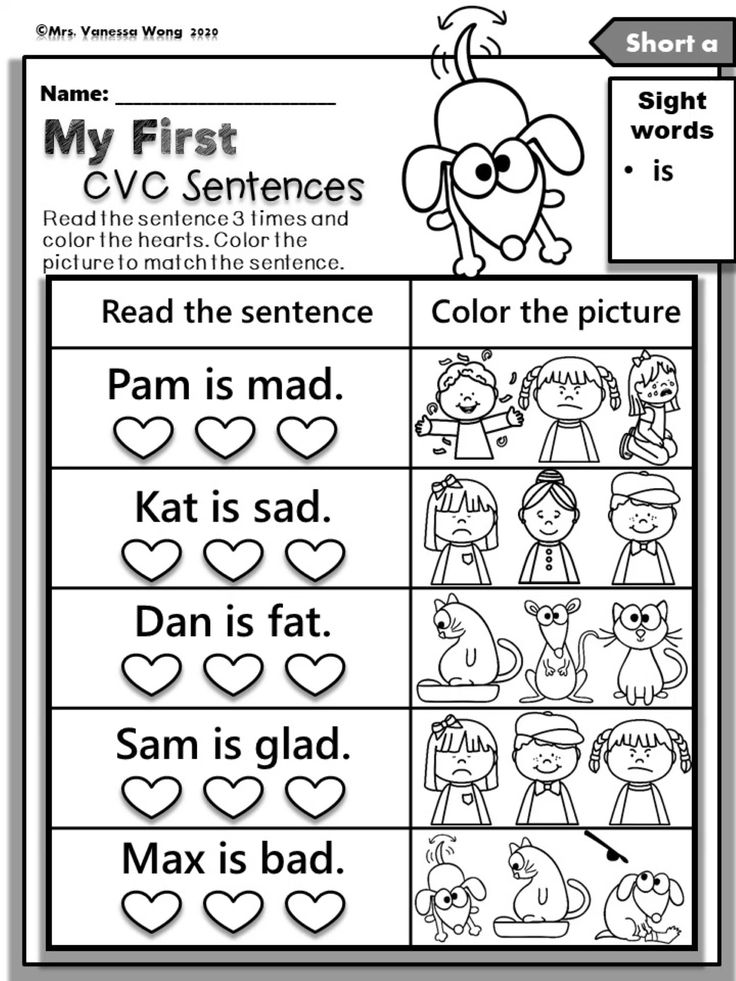

20 reading texts for children aged 5-6-7-8

A child who has learned to put sounds into syllables, syllables into words, and words into sentences needs to improve his reading skills through systematic training. But reading is a rather laborious and monotonous activity, and many children lose interest in it. Therefore, we offer texts of small size , the words in them are divided into syllables.

First read the work to the child yourself, and if it is long, you can read its beginning. This will interest the child. Then invite him to read the text. After each work, questions are given that help the child to understand what they have read and comprehend the basic information that they have learned from the text. After discussing the text, suggest reading it again.

After each work, questions are given that help the child to understand what they have read and comprehend the basic information that they have learned from the text. After discussing the text, suggest reading it again.

Mo-lo-dets Vo-va

Ma-ma and Vo-va gu-la-li.

In-va ran-sting and fell.

It hurts no-ha, but Vo-va does not cry.

Wow!

B. Korsunskaya

Answer questions .

1. What happened to Vova?

2. What made him sick?

3. Why is Vova doing well?

Clever Bo-beak

Co-nya and co-ba-ka Bo-beak gu-la-li.

So-nya played-ra-la with a doll.

That's why So-nya in-be-zha-la to-my, and the doll for-would-la.

Bo-beek found a doll-lu and brought it to So-ne.

B. Korsunskaya

Answer the questions.

1. Who did Sonya walk with?

2. Where did Sonya leave the doll?

3. Who brought the doll home?

Who brought the doll home?

The bird made a nest on a bush. De-ti our nest-up and took off on the ground.

- Look, Vasya, three birds!

In the morning, deti came, and the nest was empty. It would be a pity.

L. Tolstoy

Answer questions.

1. What did the children do with the nest?

2. Why was the nest empty in the morning?

3. Did the children do well? How would you do?

4. Do you think this work is a fairy tale, a story or a poem?

Pete and Mi-shi had a horse. They began to argue: whose horse. Did they tear each other apart.

- Give me - my horse.

- No, you give me - the horse is not yours, but mine.

Mother came, took a horse, and became nobody's horse.

L. Tolstoy

Answer the questions.

1. Why did Petya and Misha quarrel?

2. What did mother do?

3. Did the children play horse well? Why do you think so

?

9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000

015

9 9000 9000

FILVORDA for the development of reading, View here.

It will be interesting for children to read selected texts, they affect the emotional world of the child, develop his moral feelings and imagination . Children will get acquainted with the works of L. Tolstoy, K. Ushinsky, A. Barto, S. Mikhalkov, E. Blaginina, V. Bianchi, E. Charushin, A. Usachyov, E. Uspensky, G. Snegiryov, G. Oster, R. Rozhdestvensky, as well as fairy tales of different nations.

It is advisable to show children the genre features of poems, stories and fairy tales using the example of these works.

Fairy tale is a genre of oral fiction containing events unusual in the everyday sense (fantastic, wonderful or worldly) and distinguished by a special compositional and stylistic construction. In fairy tales there are fairy-tale characters, talking animals, unprecedented miracles happen.

Poem is a short poetic work in verse. The verses are read smoothly and musically, they have rhythm, meter and rhyme.

Story — small literary form; a narrative work of small volume with a small number of characters and the short duration of the events depicted. The story describes a case from life, some bright event that really happened or could happen.

In order not to discourage reading, do not force him to read texts that are uninteresting and inaccessible to his understanding. It happens that a child takes a book he knows and reads it “by heart”. Mandatory every day read to your child poems, fairy tales, stories.

Daily reading enhances emotionality, develops culture, horizons and intellect, helps to cognize human experience.

Literature:

Koldina D.N. I read on my own. - M .: TC Sphere, 2011. - 32 p. (Candy).

read the offer. Ekaterina Buneeva's home online literacy school

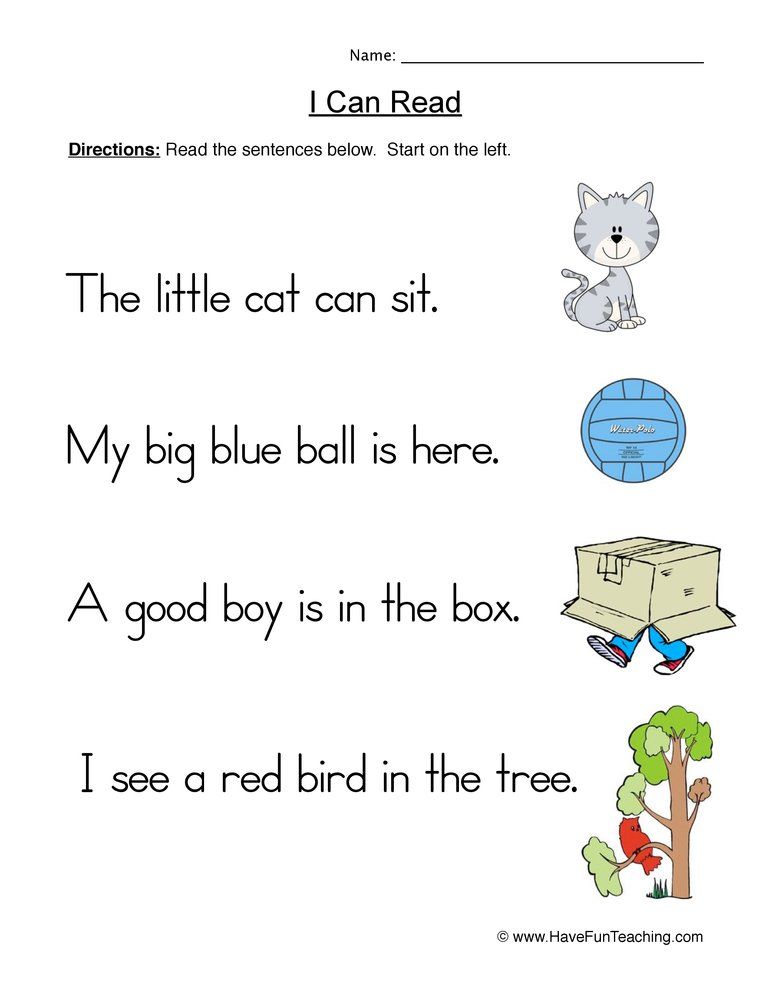

In order for a child to learn to understand a text, you must first work with a separate sentence. What does it mean? This means showing the child how to read all the factual information from the sentence, that is, teaching him to understand what the sentence says directly, explicitly. And then show that a separate sentence can also contain subtext information (something that is not directly stated, but the reader guesses).

And then show that a separate sentence can also contain subtext information (something that is not directly stated, but the reader guesses).

The tasks below are suitable for children who can already read. It can be older preschoolers, and first graders, and older children.

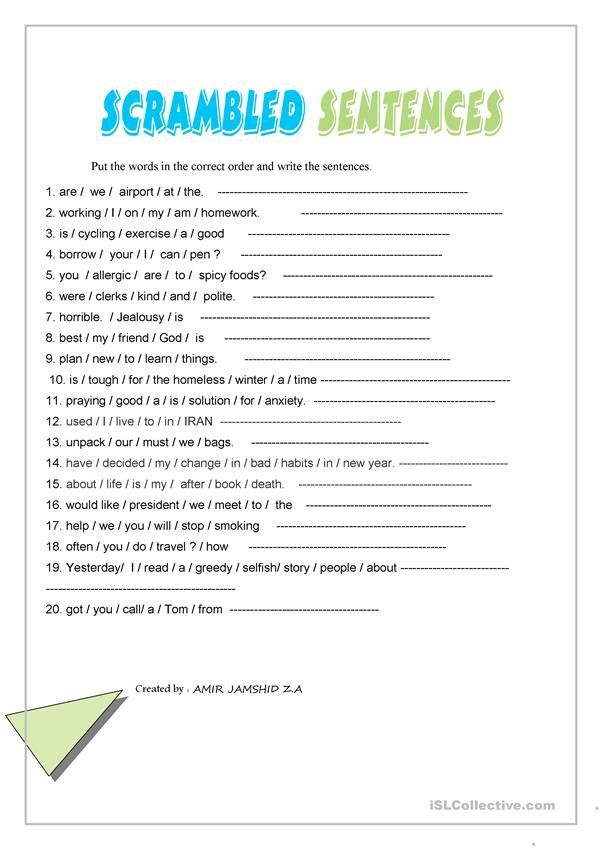

1. We teach the child to determine how many words are in a sentence and ask questions to these words. At the same time, we draw attention to the fact that the question can not be asked for every word. For example, in the sentence “Nikita has a machine with control” there are 5 words, and there will be 3 questions, because you cannot ask a question to the prepositions U and C: these words do not mean anything, they help to connect the words in the sentence. What are these questions? 1) Who has a machine with control? 2) What does Nikita have? 3) What kind of car does Nikita have?

But in the sentence “Peter stopped at the crossing”, questions can be asked to all words, except for the preposition U (Who stopped at the crossing? What did Petya do? Where did Petya stop?), and these will be questions for factual information. And you can also ask this: Why did Petya stop at the crossing? This is a question for subtext information. There is no answer to this question in the sentence, but we can guess and assume: either the red traffic light was on, or, if there was no traffic light, Petya stopped because cars were driving along the road. With the help of this exercise, we gradually teach the child to understand that the sentence contains not only information that is reported in finished form, but also that which is hidden “between the lines”, and you also need to be able to read it.

And you can also ask this: Why did Petya stop at the crossing? This is a question for subtext information. There is no answer to this question in the sentence, but we can guess and assume: either the red traffic light was on, or, if there was no traffic light, Petya stopped because cars were driving along the road. With the help of this exercise, we gradually teach the child to understand that the sentence contains not only information that is reported in finished form, but also that which is hidden “between the lines”, and you also need to be able to read it.

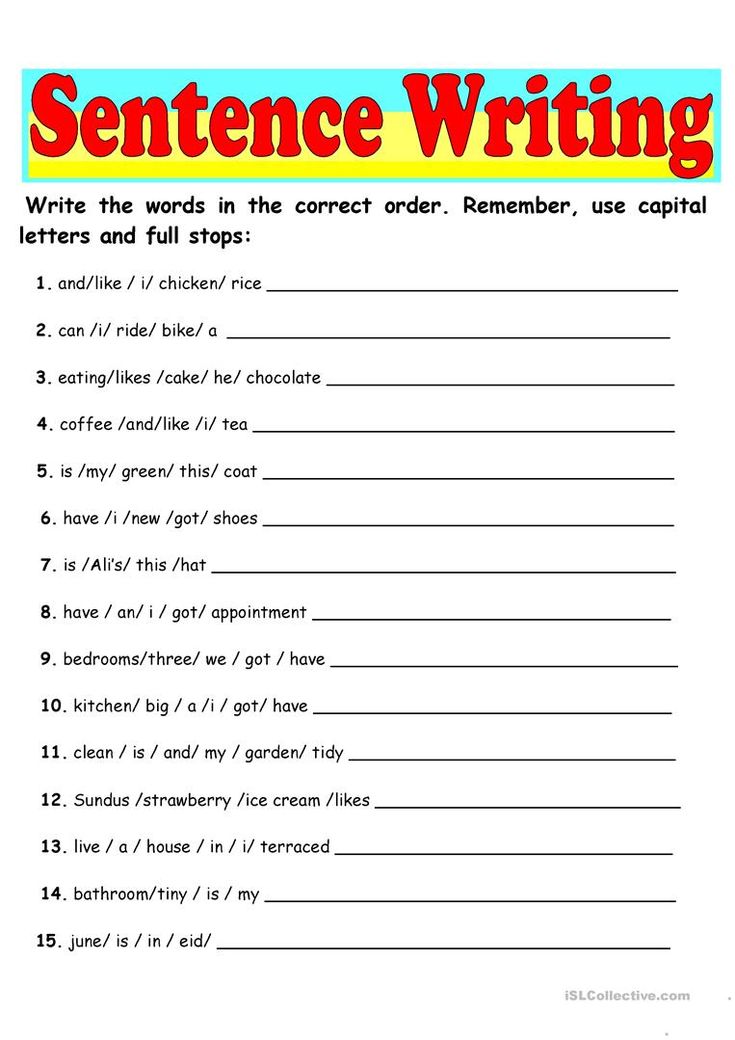

2. We learn to pay attention to word order and put logical stress. For example, we give a sentence where the word order is clearly violated (Children and pencils got the albums.) And we suggest correcting it - swapping words so that the meaning of the sentence becomes clear. And then we ask the child to read the sentence several times, highlighting a different word each time (we learn to put logical stress). For example: CHILDREN took out albums and pencils. If we highlight the word CHILDREN with our voice, this will be the answer to what question? (WHO got the albums and pencils?). Children GET out albums and pencils. And this is the answer to what question? (WHAT DID THE CHILDREN DO?), etc. You noticed that, while dealing with word order and logical stress, we essentially continue to teach how to ask questions to a sentence, but not directly, but through answers.

If we highlight the word CHILDREN with our voice, this will be the answer to what question? (WHO got the albums and pencils?). Children GET out albums and pencils. And this is the answer to what question? (WHAT DID THE CHILDREN DO?), etc. You noticed that, while dealing with word order and logical stress, we essentially continue to teach how to ask questions to a sentence, but not directly, but through answers.

3. We learn to see words in a sentence that are superfluous in meaning. In order for a child to find an extra word in a sentence, he must think about the meaning of the sentence and understand it. For example, in the sentence “Birds flew in and started nesting very much,” the extra word is very. Why? Here we will be helped by the ability to ask questions to words. The question started (how?) does not make much sense: another word is clearly needed here (immediately, soon ...), but it is not there, which means that the word is VERY superfluous, it needs to be removed.

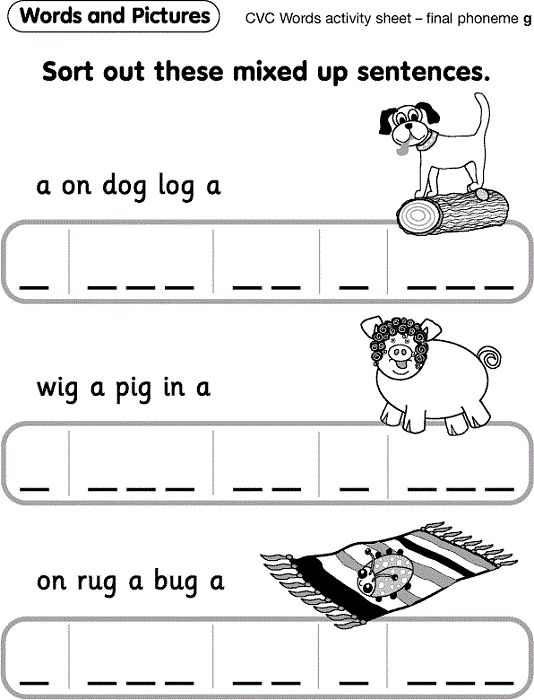

4. We check how we learned to read sentences: we perform complex tasks. Such tasks suggest that the child first composes a “scattered” sentence, excluding an extra word, and then asks questions to all independent words. For example, given the words: on, strong, was, sea, storm, ship. It is necessary to make a sentence, eliminating the extra word: There was a strong storm at sea. Then determine which words you can ask a question. There are 4 such words (all except for the preposition NA). It turns out 4 questions: What was at sea? Where was the storm? What was the storm? What does it say about a strong storm at sea?

We check how we learned to read sentences: we perform complex tasks. Such tasks suggest that the child first composes a “scattered” sentence, excluding an extra word, and then asks questions to all independent words. For example, given the words: on, strong, was, sea, storm, ship. It is necessary to make a sentence, eliminating the extra word: There was a strong storm at sea. Then determine which words you can ask a question. There are 4 such words (all except for the preposition NA). It turns out 4 questions: What was at sea? Where was the storm? What was the storm? What does it say about a strong storm at sea?

You can come up with a lot of similar tasks, you just need to choose the right sentences. You can always find them in children's books.

Working with a sentence is the first step by which you can teach a child to understand the text. The next steps are the compilation of the text based on the sentence, the comparison of the sentence and the text, and the actual work with the text.