Short imaginary stories about insects

Stories from Bug Garden | Mysite 1

Candlewick Press

Copyright © 2016 Lisa Moser

Illustrations Copyright © 2016 Gwen Millward

The story

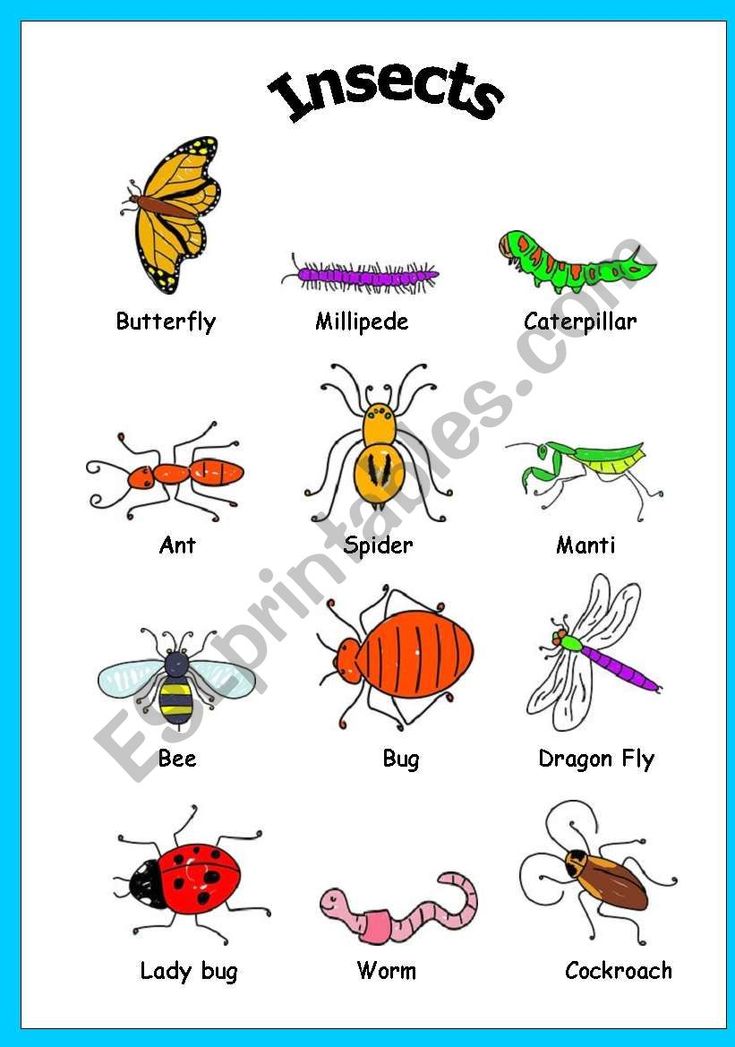

The garden is old and forgotten, so the bugs move in one by one by one. Stories from Bug Garden is a collection of 13 prose poems and short stories about each of the bugs who lives in the garden. Join Ladybug, Horsefly, Butterfly, Dragonfly, Bee, Roly-Poly, Big Ant, Little Ant, Cricket, Earthworm, Snail and Lightning Bug as they make friends and share adventures, and learn to call the garden Home.

How it was written. . .

Some days of my childhood are so etched into my memory, they feel as if they happened yesterday. One of the happiest, most carefree days was the inspiration to this book Stories from Bug Garden. I was on a Girl Scout trip, and our leader took us to her acreage for a day of playing and exploring. There was this little stream that cut through a meadow, and I remember falling in love with it.

I spent the entire sun-drenched afternoon playing by that stream, building villages and dams, digging pools and moats, and inventing all sorts of stories. I felt free and happy in this imaginary world that I created. That day was one of those gifts from God that I will always cherish.

I, also, remember hot, slow, dreamy Iowa summer days where I laid in the grass and studied whatever was happening around me. I’d watch a parade of ants marching a piece of bread back to their colony. I’d spy ladybugs on stems of grass and try to count their spots before they flew away. But the best bug memories of all happened at my school, Pence Elementary. My family would walk to the school at dusk and sit on the playground field, waiting. At first one small glimmer would appear. Then another. Before long, the whole field was lit up with lightning bugs. My sister, Sindy, and I would catch them in our hands and marvel at their brilliant lights. We’d let them go, and have another glorious chase.

Stories from Bug Garden is a tribute to all of those childhood memories. It’s a salute to playing outside, creating imaginary worlds and then coming home. Home is where the porch light glows brightly, beckoning us in. Home is where love lives.

Reviews

JUNIOR LIBRARY GUILD SELECTION

STARRED REVIEW IN KIRKUS REVIEWS

• "Compactly told in short lines, these pieces are part beginning-reader stories and part poetry. In spirit they remind me of Arnold Lobel's wonderful Frog and Toad books…These tales carry a sense of purpose, of meaning more than what's apparent. At their best they feel like little puffs of wisdom. Millward's watercolor, ink and pencil drawings highlight the stories' whimsy; her google-eyed characters and obsessive, scribbly vegetation add up to a rousing expression of cheer."

-The New York Times Book Review - Paul O. Zelinsky

• "An abandoned garden is the setting for joyful play by an array of small creatures. Prose poems, set on or next to doodly, delicate drawings, introduce this garden’s inhabitants, whose activities will appeal to young readers and listeners. . . With plentiful dialogue, these short scenes will be fun to read aloud. Whimsical and delightful, a celebration of imagination. "

Prose poems, set on or next to doodly, delicate drawings, introduce this garden’s inhabitants, whose activities will appeal to young readers and listeners. . . With plentiful dialogue, these short scenes will be fun to read aloud. Whimsical and delightful, a celebration of imagination. "

- Kirkus Reviews November 25, 2015

• "In 13 poetic stories, Moser (Kisses on the Wind) and Millward (How Do You Hug a Porcupine?) take readers on a whimsical jaunt into a garden buzzing with anthropomorphic insects. Playful language and exchanges dominate. “You know you’re not a horse,” Butterfly tells Horsefly as he gallops from flower to flower. “Well, you’re not butter, either,” retorts Horsefly. . . This pleasurable read will win over preschoolers and parents alike as it offers gentle reflections on persistence, pleasure, and perspective. "

- Publisher’s Weekly

Buy the book

Insects - Free Kids Books

Insects - Free Kids BooksMenu

Search:

Sort by: Popular Date

A little bee has lost his home and asks an elephant to help him find it. Sample Text from The Bee and the Elephant “I am lost,” said Little Bee. “I cannot find my home!” “Can you please help me, Mr. Elephant?” “Is this nest your home, Little Bee?” the elephant asked. “Oh no!” cried …

Sample Text from The Bee and the Elephant “I am lost,” said Little Bee. “I cannot find my home!” “Can you please help me, Mr. Elephant?” “Is this nest your home, Little Bee?” the elephant asked. “Oh no!” cried …

Reviews (2)

Druvi needs an umbrella to protect her wings from the rain. Join the dragonfly as she searches for the perfect leaf-umbrella. Sample Text from An Umbrella for Druvi Druvi the dragonfly has just learnt to fly. She flies near the pond with her friends. They tease the frogs and eat mosquitoes for lunch. In the …

Reviews (1)

In The Best Foot Forward the centipede gets confused over a simple task, yet is able to carry it out with ease when under stress. Have you ever got confused over a simple task? There is a reason why Centipede gets confused. Author: Rustom Dadachanji, Illustrator: Tanvi Bhat Sample Text from The Best Foor Forward …

Reviews

A Butterfly Smile – A Colourful Butterfly Biology Picturebook for young zoologist. This story is about the life cycle of butterflies. starting butterflies laying their eggs turning into cocoons and emerging into colourful butterflies. Author: Mathangi Subramanian Illustrator: Lavanya Naidu Follow along the story where Kavya a shy girl who just moved to Bengaluru to …

This story is about the life cycle of butterflies. starting butterflies laying their eggs turning into cocoons and emerging into colourful butterflies. Author: Mathangi Subramanian Illustrator: Lavanya Naidu Follow along the story where Kavya a shy girl who just moved to Bengaluru to …

Reviews (5)

Busy Ants – In this story we follow the ants as they show us what magnificent little creature they are. This book will keep your young readers entertained as they learn all about how busy the ants are and what they do, and more and us have in common. This book is one of the …

Reviews

In Shongololo’s Shoes, Shongololo’s lost his shoes and everyone tells him they haven’t seen them, but can you find Shongololo’s shoes on the pages of this cute book? And what does the lion want with all the shoes, find out more by reading this free picture book. This is a short picture book from BookDash …

Reviews (4)

One, Three, Five, HELP is a maths story that includes adding exercises and a lesson about odd and even numbers. See more books like this in our Maths category. See more books from the creators in our Pratham-Storyweaver category. Author: Kuzhali Manickavel Illustrator: Sonal Gupta Vaswani Text and Images from One, Three, Five, HELP …

See more books like this in our Maths category. See more books from the creators in our Pratham-Storyweaver category. Author: Kuzhali Manickavel Illustrator: Sonal Gupta Vaswani Text and Images from One, Three, Five, HELP …

Reviews (2)

In The Kung-Fu Grasshoppers, the grasshopper’s children are taken prisoner by a hungry monster. Two strangers arrive in the grasshopper village, an old man and his granddaughter. Who are they, and can they help to save the grasshopper children from the evil monster who holds them prisoner in the nearby woods? This suspense-filled tale of …

Reviews (1)

Wiggle-Jiggle is a cute and cuddly caterpillar story with very cute rhythm, rhyme, and repetition. Young children will love this short, beautifully illustrated picturebook. Young children will love all the fun sound words along with the bright pictures, and the inevitable ending. Illustrated by: Megan Vermaak Written by: Mathapelo Mabaso Designed by: Chenél Ferreira Edited …

Reviews (5)

In Off to See Spiders, we have a fun biology lesson about all the different types of spiders. Shama takes her two younger friends Kaveri and Shivi on a spider hunt. They find lots of different types of spiders, and Shama helps them learn about all the different names. The book combines some fun rhythm and …

Shama takes her two younger friends Kaveri and Shivi on a spider hunt. They find lots of different types of spiders, and Shama helps them learn about all the different names. The book combines some fun rhythm and …

Reviews (2)

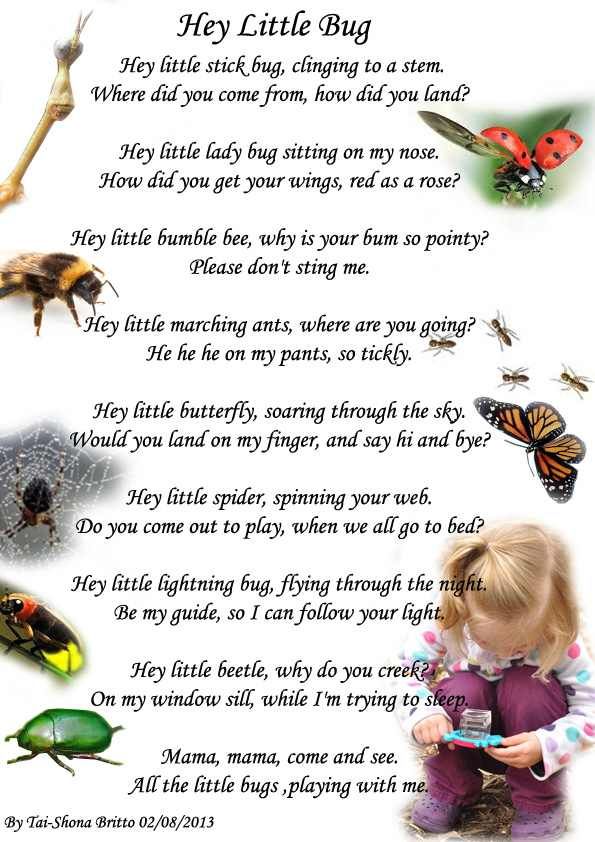

➤Insect stories for preschoolers

Contacts

Insect stories for preschoolers

- Details

- Author: Galina Obnorskaya

- Category: Reading

Rating: 5 / 5

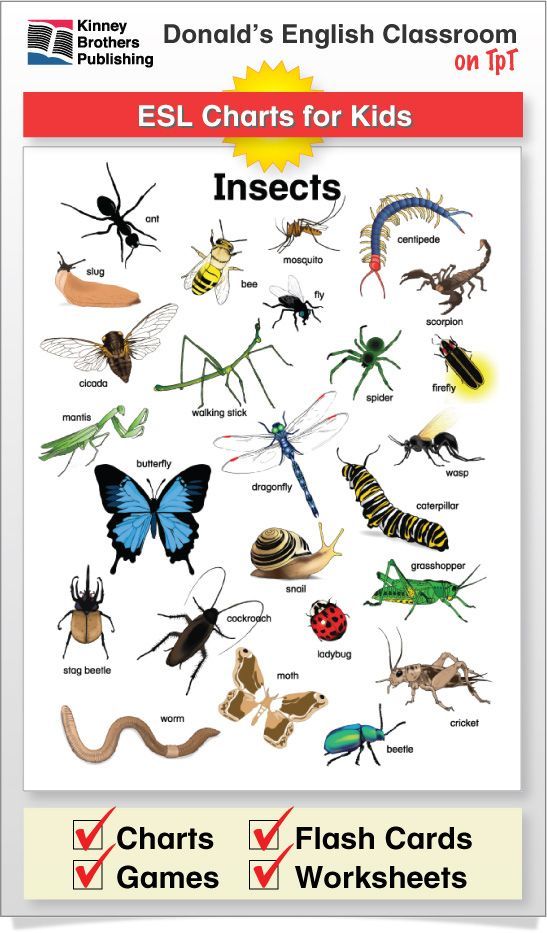

Please rate Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 These short stories about insects, like others, were written for children with attention and memory problems.

It is difficult for them to listen to long stories, to remember and retell them as well.

Nature stories are most suitable for the gradual development of self-control and learning to work with a book. It is useful to combine working with text with crafts from different materials, drawing.

Insect stories

The author of informative stories about insects is Galina Obnorskaya, a child psychologist.

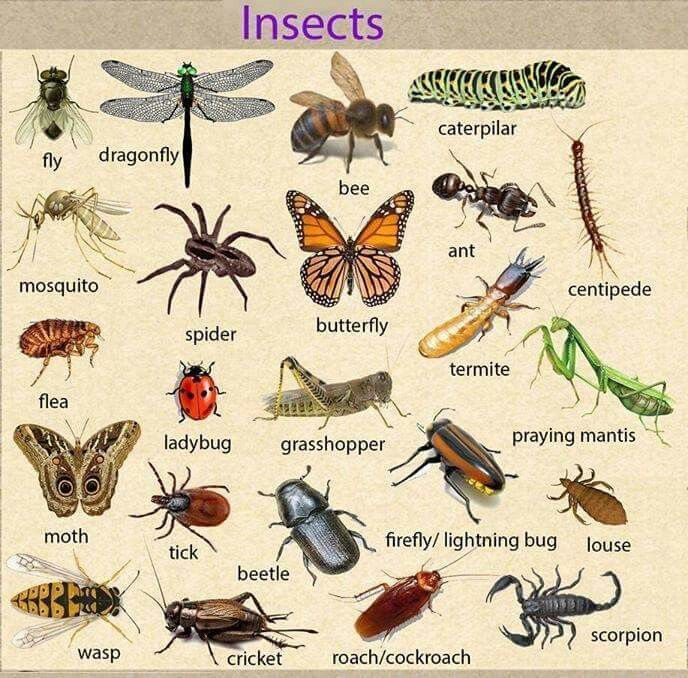

Why do bees dance

?The honey bee has a family. It's called Roy. Sisters - bees live together. The bee will find a lot of honey, tell the rest.

She can't speak! It just buzzes. It's true, he can't speak, but he can dance.

Bee's dance is simple. She flies in a circle or in a figure eight, buzzes loudly and wags her belly. As if saying:

- I found a lot of honey! Follow me quickly.

Questions.

- Why is a bee called a honey bee?

- What is the name of the bee family?

- How does a bee transmit information to other bees?

- Name the bee affectionately.

- How to call a very large bee, very small? ..

- Whose wings does the bee have?

Dragonfly

Dragonflies live near water: rivers, streams, lakes. The dragonfly flies very fast, deftly dodges. The speed is such that a person rushing on a bicycle can catch up.

Dragonflies are hunters. They have excellent eyesight. Dragonflies fly like helicopters over water in search of prey. Their prey are small mosquitoes, midges. A large dragonfly attacks smaller dragonflies. Does not disdain a caterpillar.

When a dragonfly flies, it folds its legs into a house. It turns out to be a trap. A mosquito gaped and got into the house from her tenacious paws. The dragonfly immediately sends it into the mouth.

Dragonflies are beautiful insects. Take care of them. They decorate nature.

Questions.

- Where do dragonflies live?

- What do they eat?

- How does a dragonfly hunt?

- Name a dragonfly affectionately.

- How to call a very large dragonfly, very small? ..

- Whose wings does the dragonfly have?

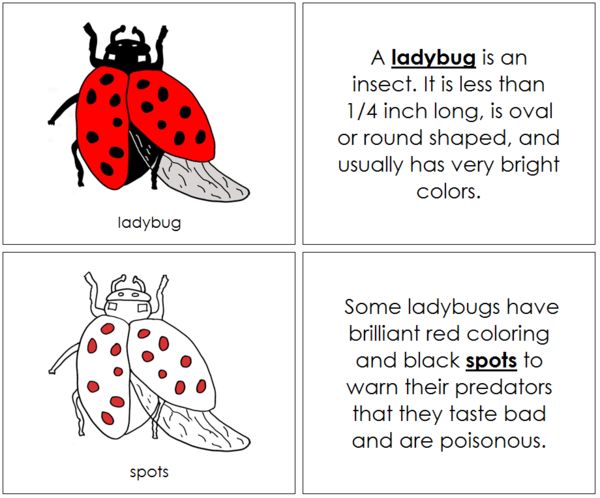

Ladybug

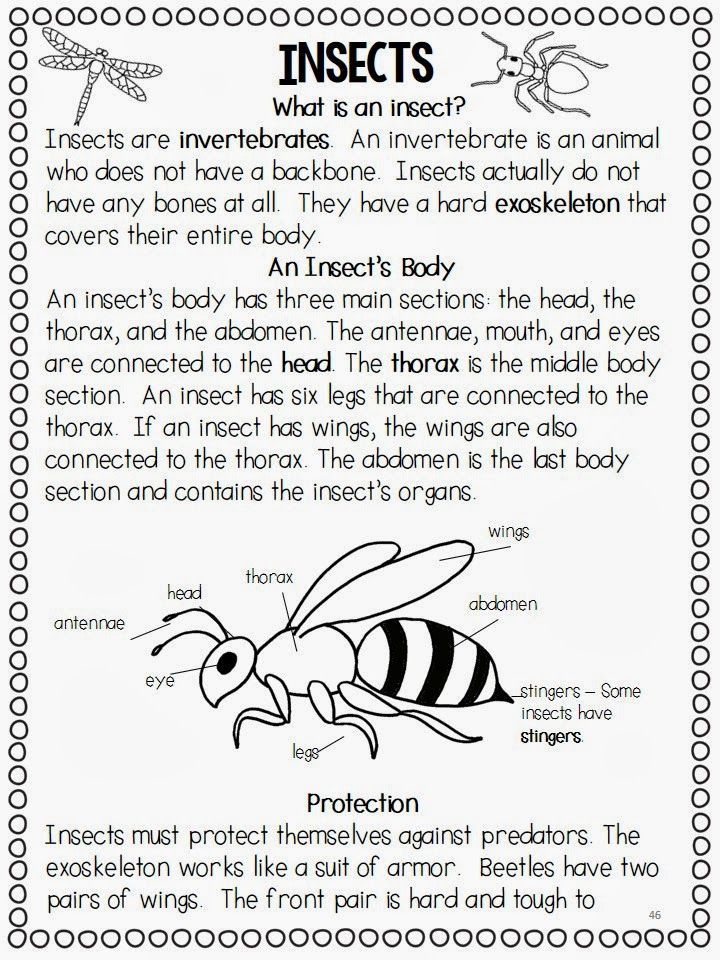

The small ladybug beetle is known to everyone. She has two rigid and strong wings of yellow, orange or red color with black dots. And under them soft wings are hidden.

Top wings for protection. Lower wings for flight. It is necessary for the ladybug to fly, the upper wings rise, the lower ones straighten out, and the beetle flies.

Don't hurt the ladybug. She is a true friend and helper. Pests - aphids - settle on plants in the garden and in greenhouses. Aphids suck juices from leaves. The leaves dry up, curl up and fall off.

A ladybug eats aphids to save plants. Ladybugs are specially bred and released into gardens. There she fights aphids, helping people.

Questions.

- Why does a ladybug need different wings?

- What does the beetle eat?

- How do aphids harm plants?

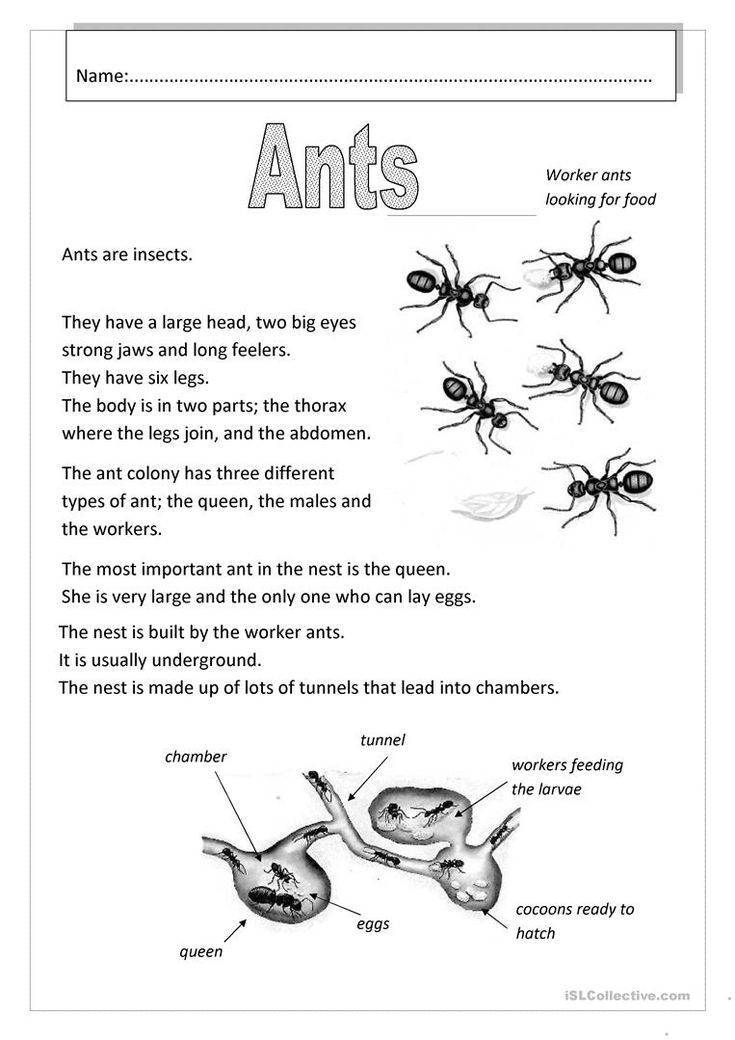

Ants

During the warm season, ants can be found everywhere. They run about their ant affairs back and forth. They seem so small and stupid. In fact, ants are smart insects. Their brain works like a powerful computer. That's what the scientists say.

They run about their ant affairs back and forth. They seem so small and stupid. In fact, ants are smart insects. Their brain works like a powerful computer. That's what the scientists say.

Ants are strong insects. An ant lifts a load 50 times heavier than itself.

The little ant won't be offended. He sprays the offenders with formic acid. Formic acid is caustic. It even causes burns.

People are not afraid of formic acid. But you can’t touch the ants, ruin the anthills. Ants are beneficial insects in the forest.

Questions.

- What is the name of the ant house?

- How does the ant's brain work?

- What does an ant spray on offenders?

- Name an ant affectionately.

- How to call a very large ant, very small? ..

- Whose head does the ant have?

Mukha

Everyone knows the fly. She is mean and annoying. Buzzing, buzzing.

The fly has six legs and four wings.

Transparent wings. Two front wings for flight. Hind wings for balance in flight. They are called bugs.

Two front wings for flight. Hind wings for balance in flight. They are called bugs.

The fly has Velcro on its feet. They help the fly crawl even upside down.

The fly carries various diseases. She crawls everywhere, and dirt with microbes sticks to her paws. A fly will crawl over a clean place and leave microbes on it.

Questions.

- Where does the fly live?

- What are the wings of a fly?

- Why can a fly crawl upside down?

- Why does a fly carry various diseases?

- Name the fly affectionately.

- How to call a very large fly, very small? ..

Butterflies

Butterflies are the beauty of nature. There are many around. Butterfly colors are different. It pleases our eyes.

Butterflies are small and large. Their body is covered with small scales.

Butterflies feed on the nectar of flowers. They drink it with their proboscis. In spring, when there are still few flowers, butterflies drink birch or maple sap.

Questions

- What color are the butterflies?

- What size are they?

- What is the body of butterflies covered with?

- What do butterflies eat?

Mosquito

Guess the riddle: "Grey. With two wings. It flies - it rings. It bites painfully." The mosquito has a mustache and a proboscis on its head. The mosquito makes no sound. The ringing comes from mosquito wings. A mosquito flies, and its wings rattle thinly. It makes a call.

We don't like mosquitoes. A mosquito will sit on a person or animal, pierce the skin with its proboscis and drink the blood. Poisonous mosquito saliva will get under the skin. Because of this poison, the bite site itches for a long time. Mosquitoes fly to heat. In the evenings and at night, warm animals are easier to find. Only mosquitoes bite us. And mosquitoes drink flower nectar. Their proboscis is very thin. They will not bite through thick human skin and animal skin.

Questions

- How many wings does a mosquito have?

- What sound does a mosquito make when it flies?

- Where does this sound come from?

- What do mosquitoes eat?

- How do mosquitoes find who to bite?

- Why does the bite site itch and itch for a long time?

- Name a mosquito affectionately.

- How to call a very large mosquito, very small? ..

- Whose wings does a mosquito have?

- Back

- Forward

Add a comment

Popular

- Short stories about animals

- Association games

- Texts to read by syllables

- Search for antonyms

- Minimal brain dysfunction (MMD)

- Insect stories for preschoolers

- Miramistin for babies

Home

90,000 Six-legged masters of the planet. Paleoentomologist talks about their formation and development

Paleoentomologist talks about their formation and development Insects have lived on Earth for over 400 million years. They were among the first to master the land and had a gigantic impact on other organisms, in particular, on vertebrates - for example, without insects, we could remain as hairy as chimpanzees. In A Brief History of Insects: The Six-Legged Masters of the Planet (Alpina Non-Fiction Publishing House), paleoentomologist Alexander Khramov explains what ancient insects were like, how they evolved, and how closely related to the rest of nature. We invite you to familiarize yourself with a fragment devoted to the appearance of insects leading a parasitic lifestyle.

Forest has always been Tasmania's main natural resource. In the 19th century from the blue eucalyptus they built transoceanic ships for the transport of emigrants, they harvested lumber for the fast-growing cities of neighboring Australia. When local trees became scarce, the Tasmanians began to plant North American radiant pine in place of the cut down forests. All was well until the 1950s. Horntail Sirex noctilio did not enter Tasmania. In Europe and Asia, this species of large sawfly, whose larvae live in the trunks of coniferous trees, does not cause much harm, but its introduction into the forests of the Southern Hemisphere turned into a real disaster. From the horntails, which spread at the speed of a forest fire, thousands of hectares of radiant pine dried out. Tasmania's logging industry is on the brink of collapse. Australian authorities have urgently created a government commission to counteract this pest ...

When local trees became scarce, the Tasmanians began to plant North American radiant pine in place of the cut down forests. All was well until the 1950s. Horntail Sirex noctilio did not enter Tasmania. In Europe and Asia, this species of large sawfly, whose larvae live in the trunks of coniferous trees, does not cause much harm, but its introduction into the forests of the Southern Hemisphere turned into a real disaster. From the horntails, which spread at the speed of a forest fire, thousands of hectares of radiant pine dried out. Tasmania's logging industry is on the brink of collapse. Australian authorities have urgently created a government commission to counteract this pest ...

Horntails are especially harmful because they stuff pines not only with their voracious larvae, but also with white rot. This variety of basidiomycete fungi is necessary for larvae to assimilate living wood. Without white rot, they simply cannot develop. Therefore, each female Sirex noctilio at the base of a powerful ovipositor, with which they saw through the bark, has two mikangia - special bags for transporting mushroom mycelium. When an insect lays an egg in a sawn hole, a portion of the mycelium is also sent there. However, this is not the case for all horntails. Females from genus Xeris , devoid of Mikangii, decided to cheat a little. Instead of supplying their offspring with mycelium themselves, they lay their eggs in the passages of other sawflies who have taken care of its presence. From here lies a direct path to the parasitoid way of life.

When an insect lays an egg in a sawn hole, a portion of the mycelium is also sent there. However, this is not the case for all horntails. Females from genus Xeris , devoid of Mikangii, decided to cheat a little. Instead of supplying their offspring with mycelium themselves, they lay their eggs in the passages of other sawflies who have taken care of its presence. From here lies a direct path to the parasitoid way of life.

As we already know, an insect that eats a plant, especially if it does so from the inside, is essentially a parasite. If you have learned to survive inside another living being, then by and large what difference does it make - a plant or an animal? The boundary between insects that parasitize on both is not so impenetrable as it might seem at first glance. For example, gall wasps evolved from normal wasps who, perhaps having difficulty finding prey, began to lay their eggs directly in leaves, and not in insects hiding there. Then some of the gall wasps returned to parasitism: instead of building their own galls, they began to lay their eggs in the galls of other species. It is believed that the same type of behavior aimed at expropriating foreign resources led to the emergence of the very first parasitoid hymenoptera at the beginning of the Jurassic.

It is believed that the same type of behavior aimed at expropriating foreign resources led to the emergence of the very first parasitoid hymenoptera at the beginning of the Jurassic.

Sawflies are considered to be the ancestors of parasitoids, which, like horntails Xeris , first stole food from other herbivorous endophages and then began to kill them. Indeed, why swallow someone else's sawdust in half with mold, if you can immediately eat their owner? It didn't cost anything for sawflies to switch to eating the inhabitants of wood, as soon as they learned to find their passages under the bark. This is exactly what sawflies belonging to the modern Orussidae family (Orussidae; Fig. 7.3) do. Their females lightly tap their antennae on the surface of the trunk, and perceive the resulting vibrations with their paws. This helps them to find cavities eaten by the larvae of horntails and borers, and lay eggs there. After hatching, the orussid larvae begin to eat the owner of the passage alive from the rear end of the body. The victim cannot offer any resistance, because the clearance of the passage is so narrow that it does not allow her to turn her head towards the offender.

The victim cannot offer any resistance, because the clearance of the passage is so narrow that it does not allow her to turn her head towards the offender.

The Orussids are a real transitional link, designed to shame the opponents of the theory of evolution. On the one hand, they look like typical herbivorous sawflies, in which the abdomen is connected to the chest without a narrow constriction at the base. Guided by this feature, entomologists combine orussids together with other sawflies into the suborder Sedentary (Symphyta). On the other hand, the presence of parasitoid larvae brings Orussids closer to the suborder Apocrita, which includes about 95 percent of Hymenoptera species. This suborder bears such a name, since its representatives have a stalk formed by a narrowing of the abdomen - the very well-known "wasp waist". The stalk was needed by parasitoids to increase the mobility of the abdomen. Thanks to the stem, riders can bend the abdomen upward at a right angle and direct the long ovipositor vertically downward, sticking it into the victim, just as St. George the Victorious, holding a spear in his raised hand, strikes a snake. Orussids, forced to do without a stalk, are unfinished riders, an unfinished sketch, the author of which abandoned the work halfway through. What else is needed to be convinced of the existence of evolution?

George the Victorious, holding a spear in his raised hand, strikes a snake. Orussids, forced to do without a stalk, are unfinished riders, an unfinished sketch, the author of which abandoned the work halfway through. What else is needed to be convinced of the existence of evolution?

The transition to a parasitic way of life was a real evolutionary breakthrough for Hymenoptera. Plant biomass, as we remember, is not the most digestible food. It takes a lot of time to extract the nutrients from it. Parasitoids are waiting for others to do this work for them, and they come (or rather, fly) to everything that is ready. Wood-feeding horntail larvae take one to three years to develop, while parasitoid larvae take only a few weeks to develop. Due to this, the change of generations in parasitoids occurs faster, and, consequently, their evolution also accelerates. At the beginning of the Jurassic, when ichneumons first appeared, their diversity was limited to only four families, but by the beginning of the Cretaceous period, the total number of families of parasitoid hymenoptera had already exceeded 20. Some scientists call this jump in diversity the Mesozoic parasitoid revolution.

Some scientists call this jump in diversity the Mesozoic parasitoid revolution.

The parasitoid revolution came in handy to keep the number of new groups of phytophages that arose in the Mesozoic. If not for parasitoids, the first flowering plants that appeared in the Cretaceous would have been eaten on the vine. Having relied on a high growth rate (which we will talk about later), flowering plants abandoned the tough, lignin-rich foliage characteristic of gymnosperms, which are better protected from phytophages, but grow more slowly. This strategy of flowering plants, which allowed them to take the lead, turned out to be advantageous only because herbivorous insects, in addition to predators, were tightly controlled by parasitoids. At least the fact that two-thirds of successful examples of the application of biological methods of controlling insect pests are associated with the use of parasitoid hymenoptera speaks for their effectiveness. You can groan and gasp as much as you like at the cunning and ruthlessness of parasitoids, but if not for them, the flowering ones would never have taken a dominant position in the plant world - they would simply be torn to pieces by an insatiable mob of caterpillars and beetles.