Sight word was

Browse Sight Word Educational Resources

Entire LibraryPrintable WorksheetsGamesGuided LessonsLesson PlansHands-on ActivitiesInteractive StoriesOnline ExercisesPrintable WorkbooksScience ProjectsSong Videos

481 filtered results

481 filtered results

Sight Words

Sort byPopularityMost RecentTitleRelevance

-

Filter Results

- clear all filters

By Grade

- Preschool

- Kindergarten

- 1st grade

- 2nd grade

- 3rd grade

- 4th grade

- 5th grade

- 6th grade

- 7th grade

- 8th grade

By Subject

- Coding

- Fine arts

- Foreign language

- Math

Reading & Writing

- Leveled Books

- Reading

- Writing

Grammar

- Phonics

Spelling

Sight Words

- High Frequency Words

- Irregularly Spelled Words

- Spelling Tools

- Spelling Strategies

- Spelling Patterns

- Language and Vocabulary

- Grammar and Mechanics

- Science

- Social emotional

- Social studies

- Typing

By Topic

- Arts & crafts

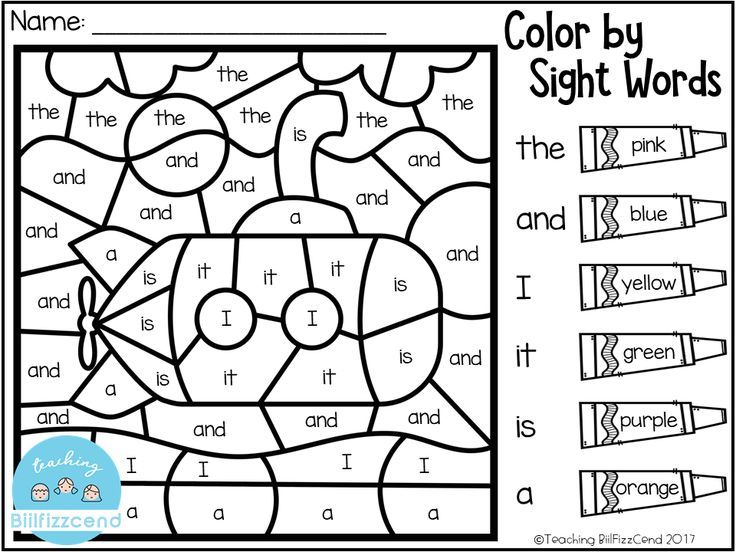

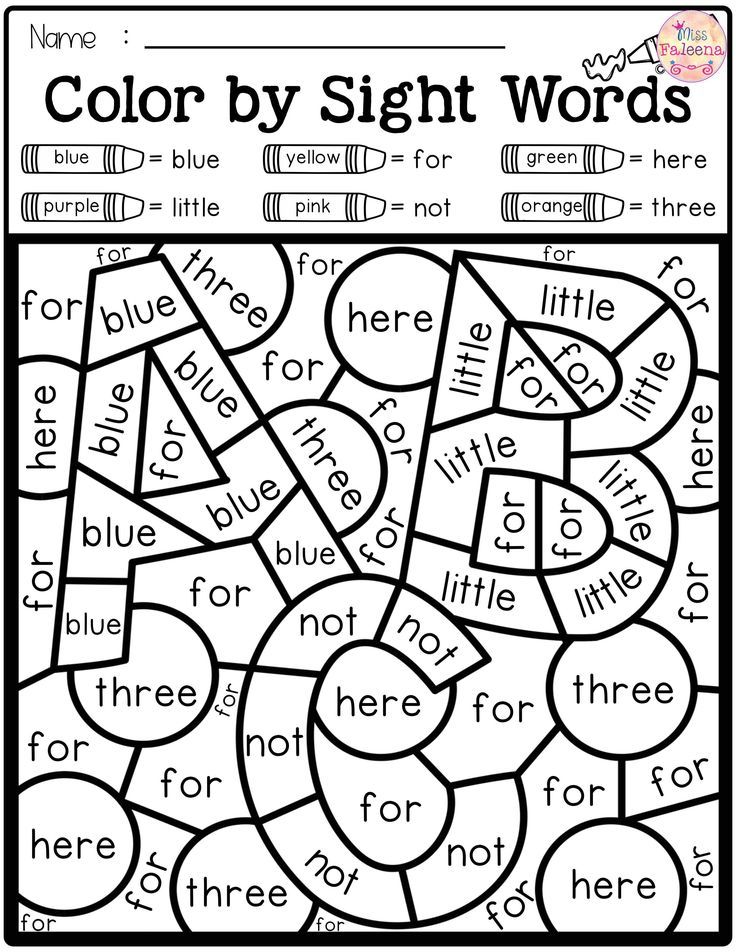

- Coloring

- Holidays

- Offline games

- Seasonal

By Standard

- Common Core

Sight Words 2

Guided Lesson

Sight Words 2

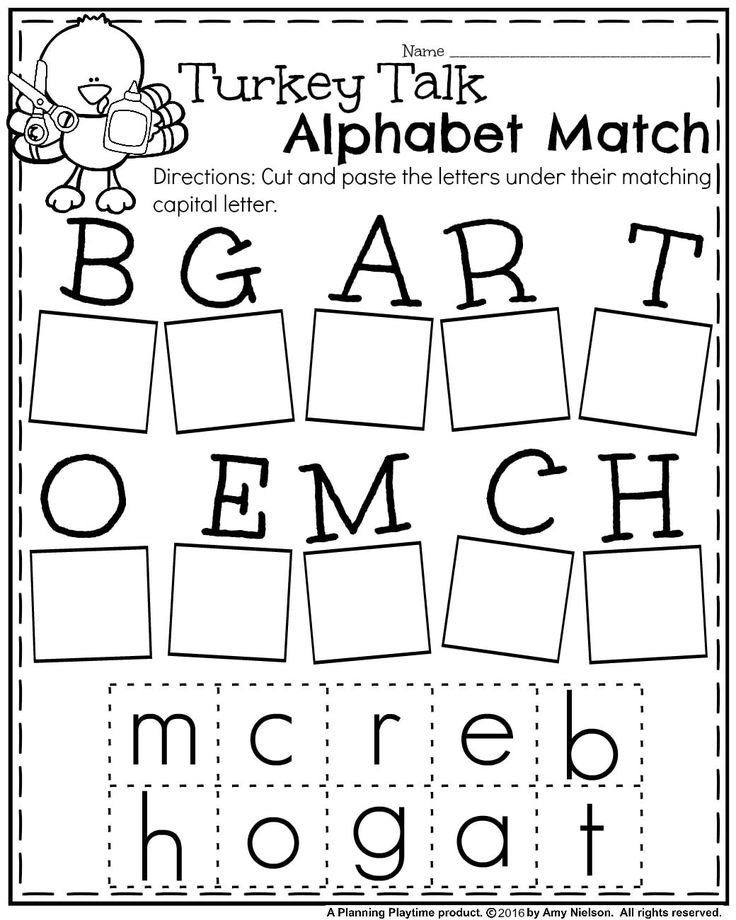

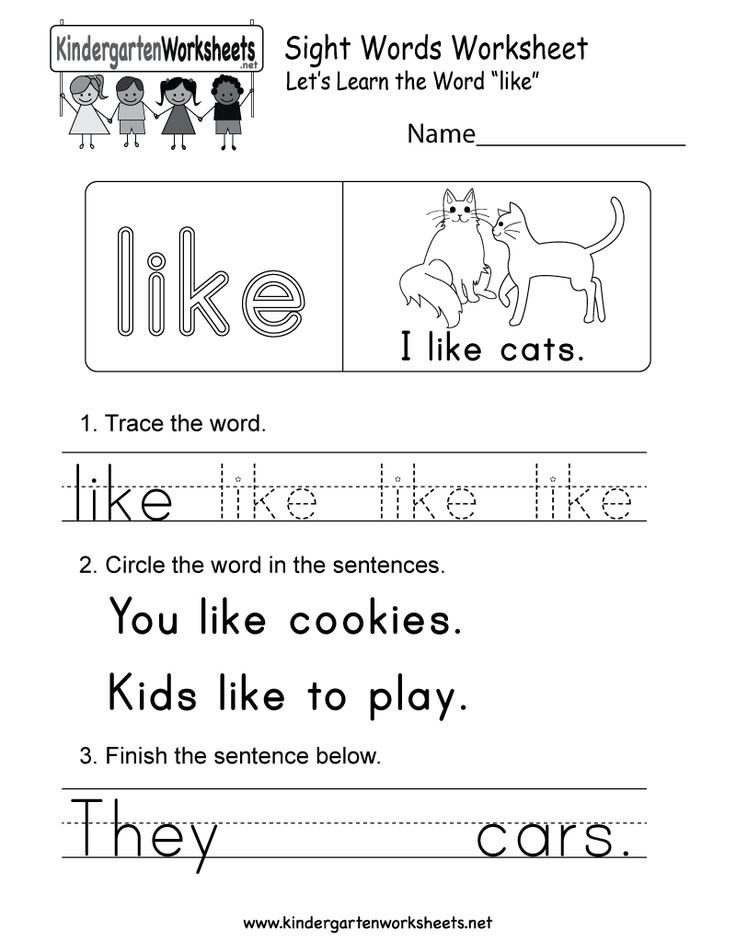

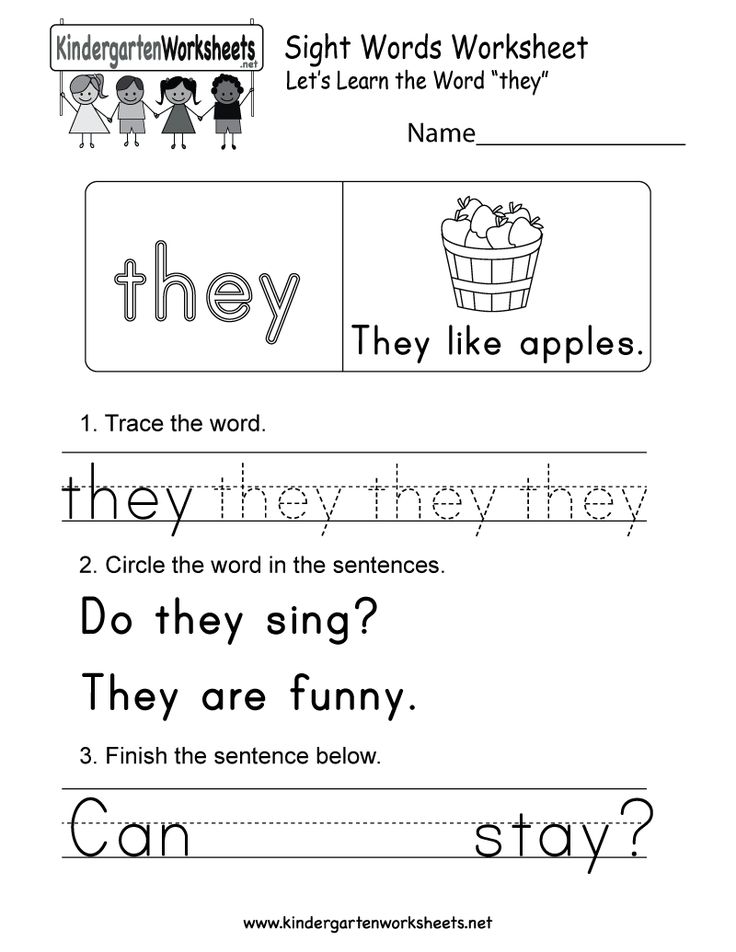

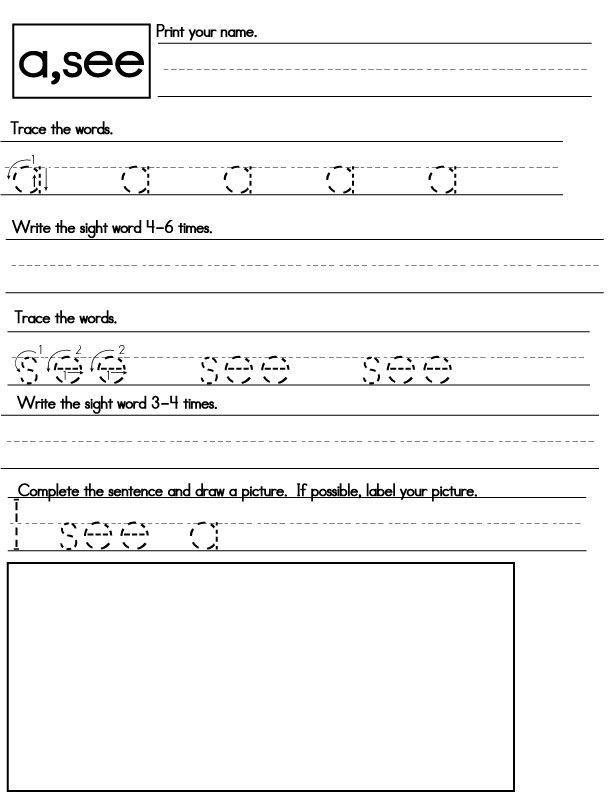

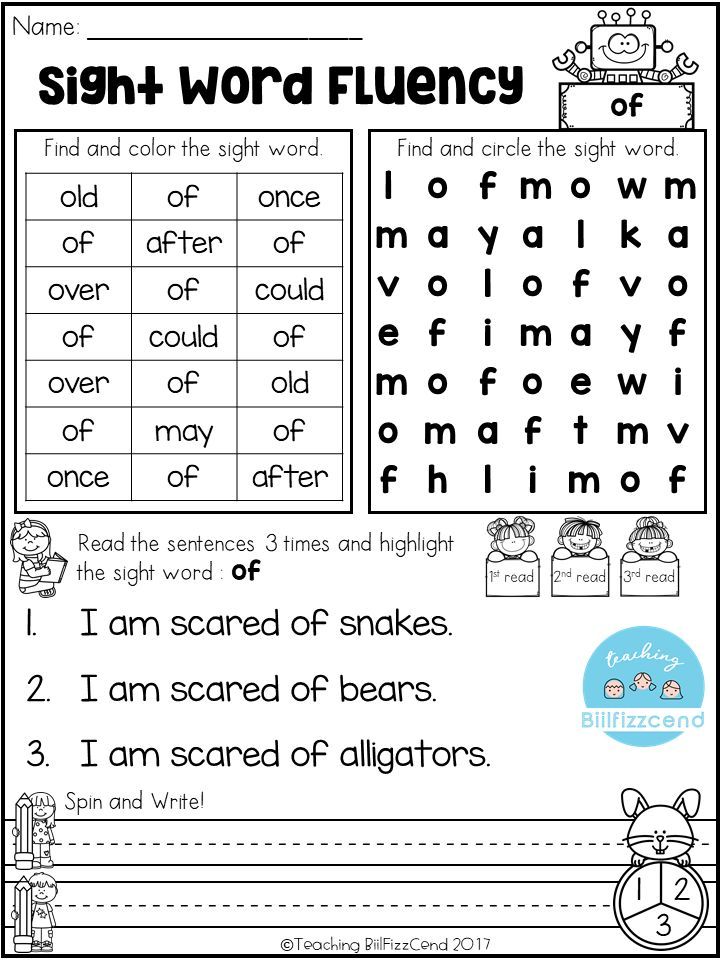

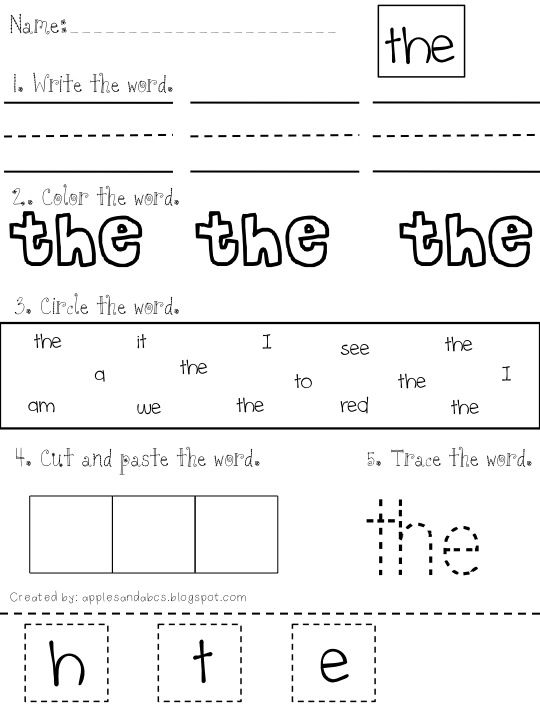

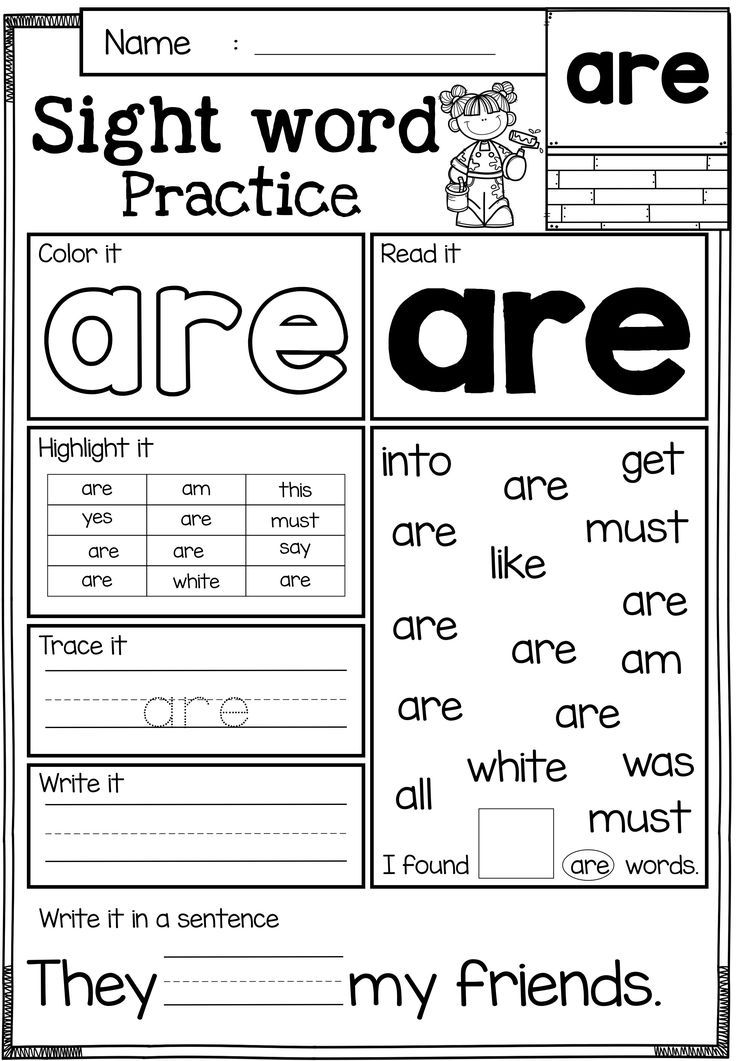

In kindergarten, kids are piecing together all the words and letters they can decode in order to build stronger reading fluency. This is why their understanding of sight words, or commonly occurring words, is so important. This guided lesson familiarizes first graders with the sight words they will most frequently encounter in texts, boosting their decoding and comprehension skills.

Kindergarten

Reading & Writing

Guided Lesson

Spelling 1

Guided Lesson

Spelling 1

Spelling is a core language arts skill in the third grade curriculum. You can support kids' spelling skills with this guided lesson that features targeted instruction in common spelling patterns, as well as plenty of chances to practice. The content of this lesson was created by our team of teachers and curriculum experts. For even more spelling practice, consider downloading and printing our recommended spelling worksheets.

3rd grade

Reading & Writing

Guided Lesson

Blending 2

Guided Lesson

Blending 2

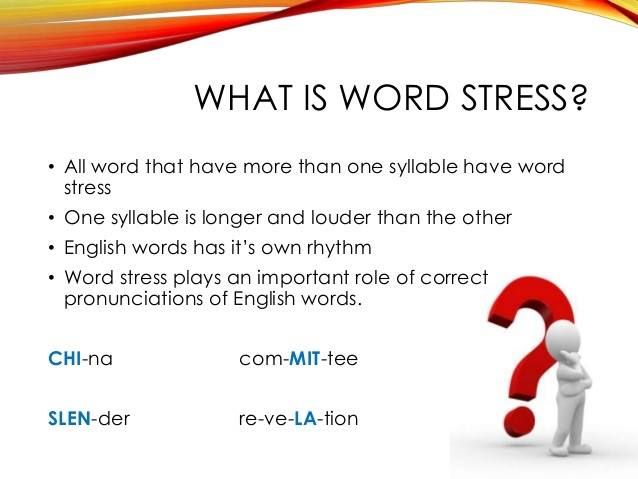

Teaching kids to blend, or combine, sounds in order to pronounce new words is an important element to first grade reading. Segmenting the sounds that make up a word, and then blending those sounds to pronounce them correctly, can be a tricky skill to master. This lesson helps take first graders through this process, with guided practice and helpful examples.

Segmenting the sounds that make up a word, and then blending those sounds to pronounce them correctly, can be a tricky skill to master. This lesson helps take first graders through this process, with guided practice and helpful examples.

1st grade

Reading & Writing

Guided Lesson

Search Sight Word Educational Resources

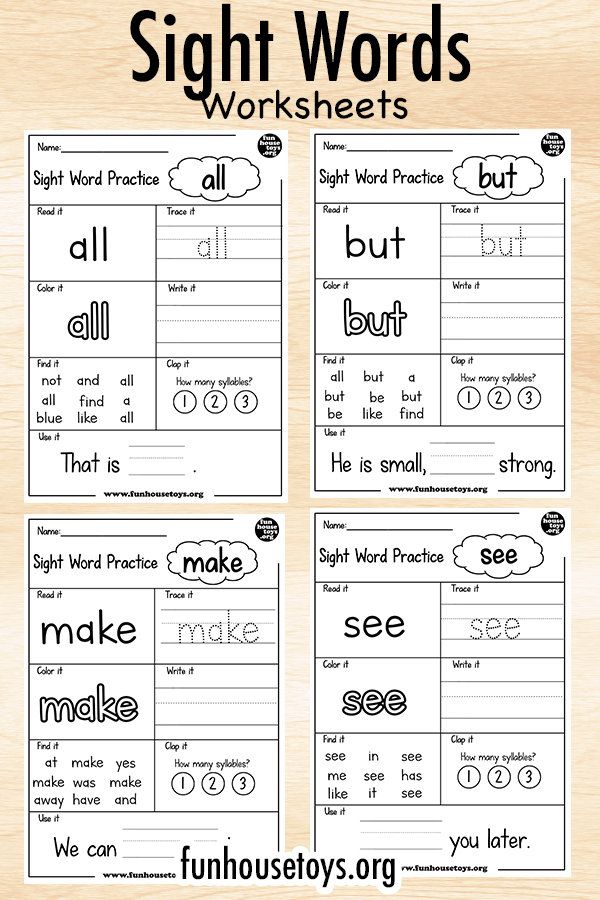

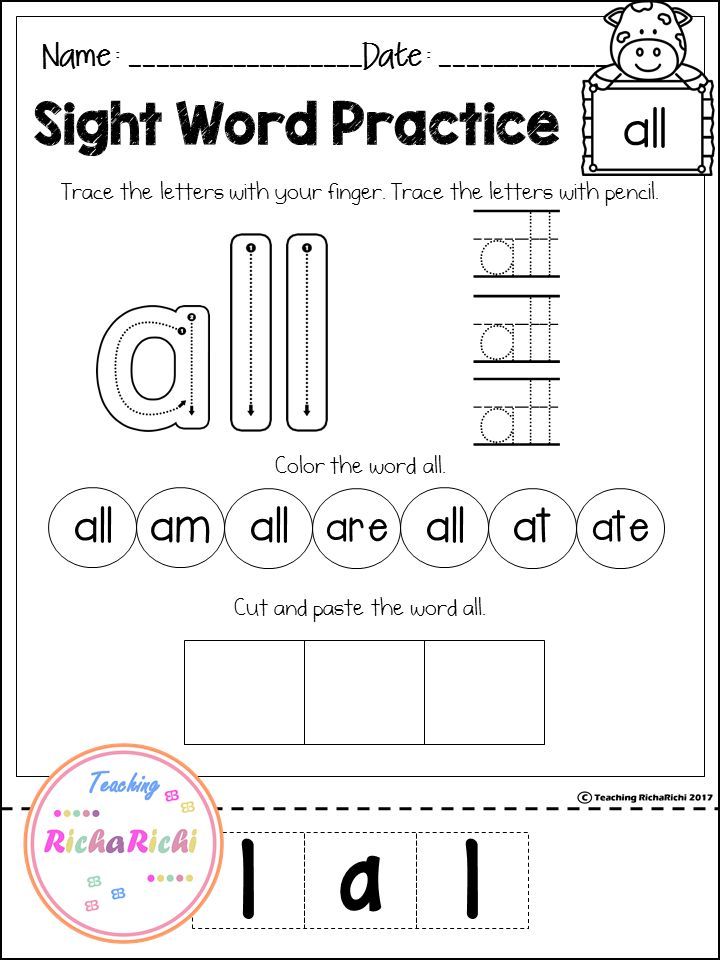

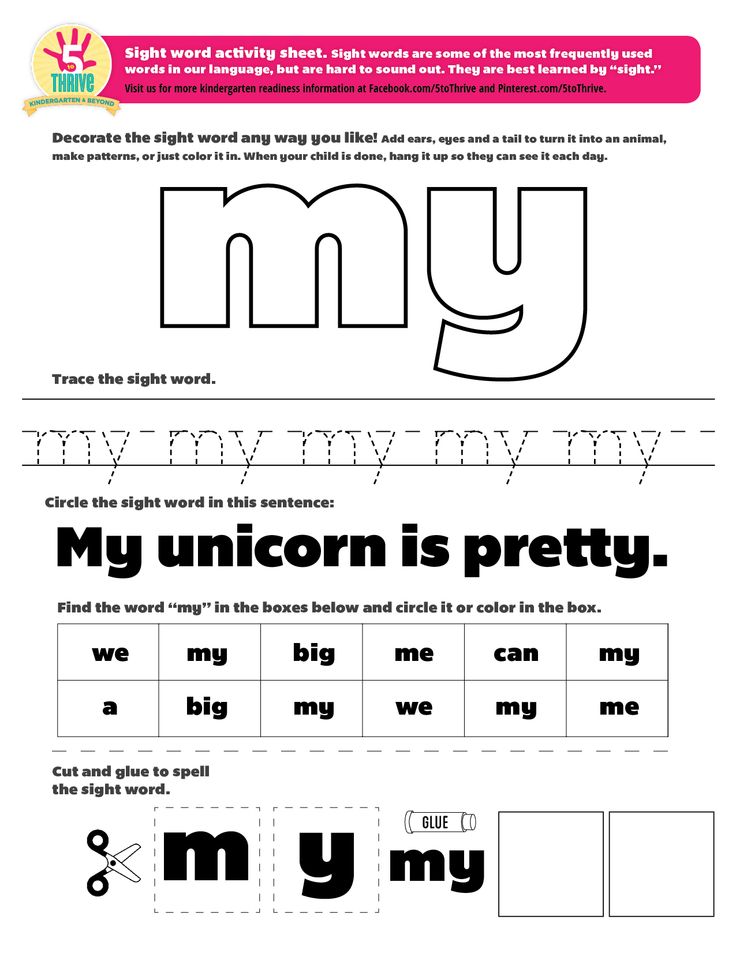

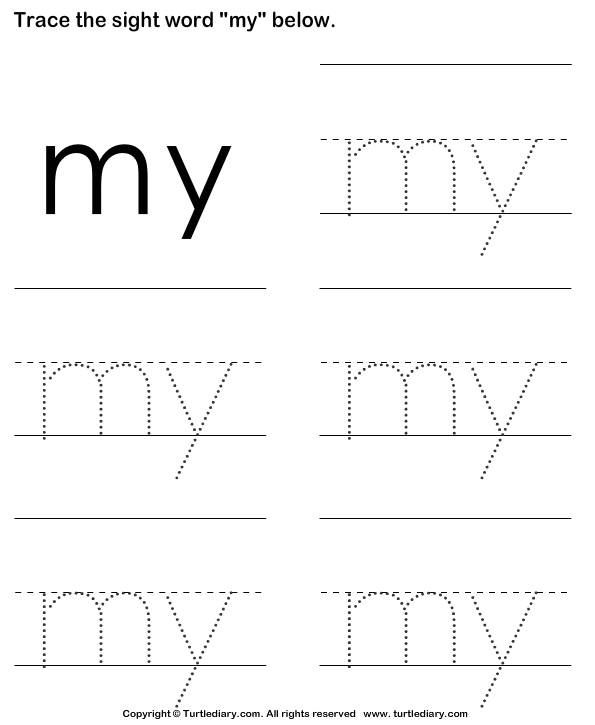

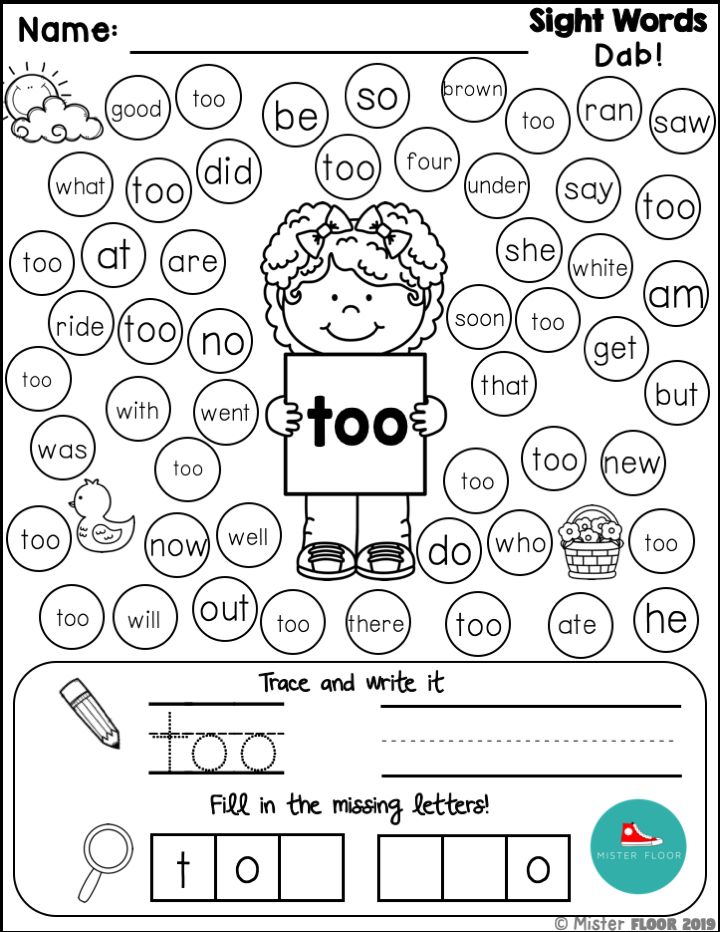

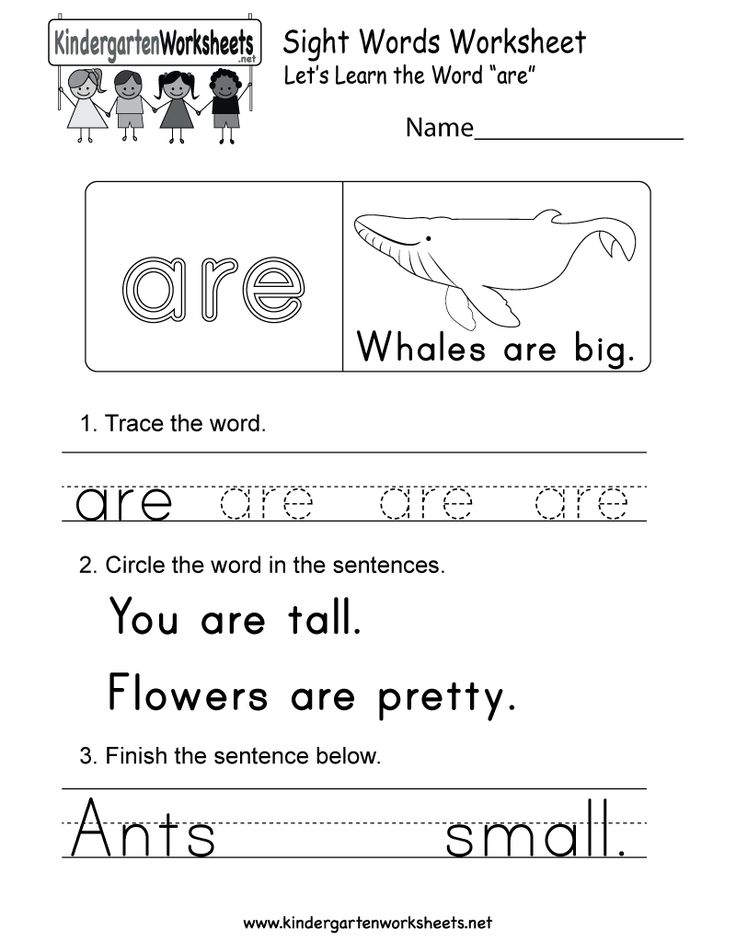

Learning sight words can be tricky for young children. These words are frequently used but don't always follow conventional spelling patterns, so it can take repeated exposure to help your child remember them. Our selection of worksheets, games, and other content is an excellent combination of sight words help to give to your child. Get additional reading help to boost your child's academic skills.

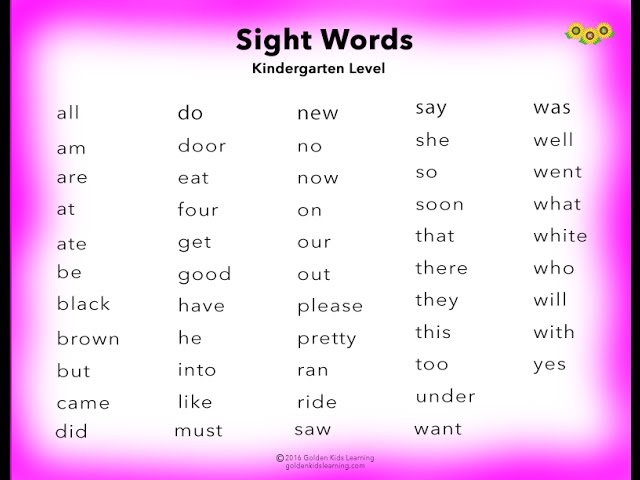

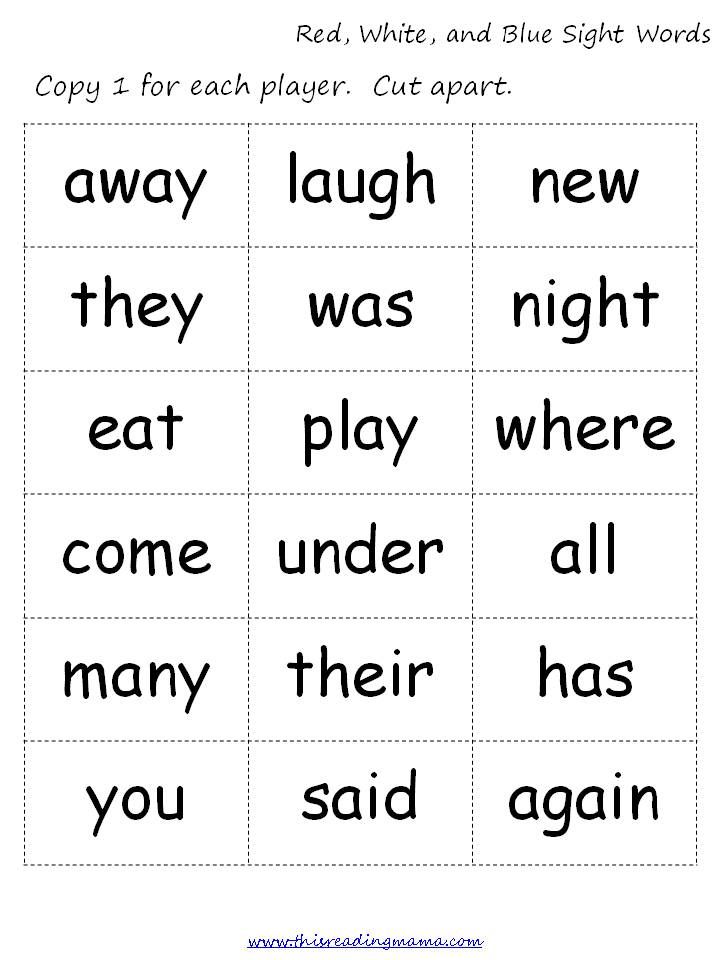

Sight Words 101

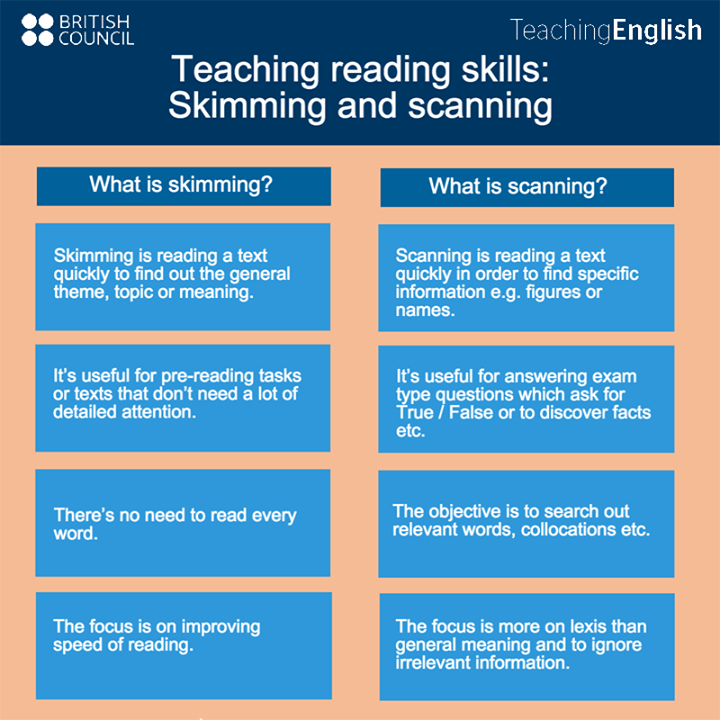

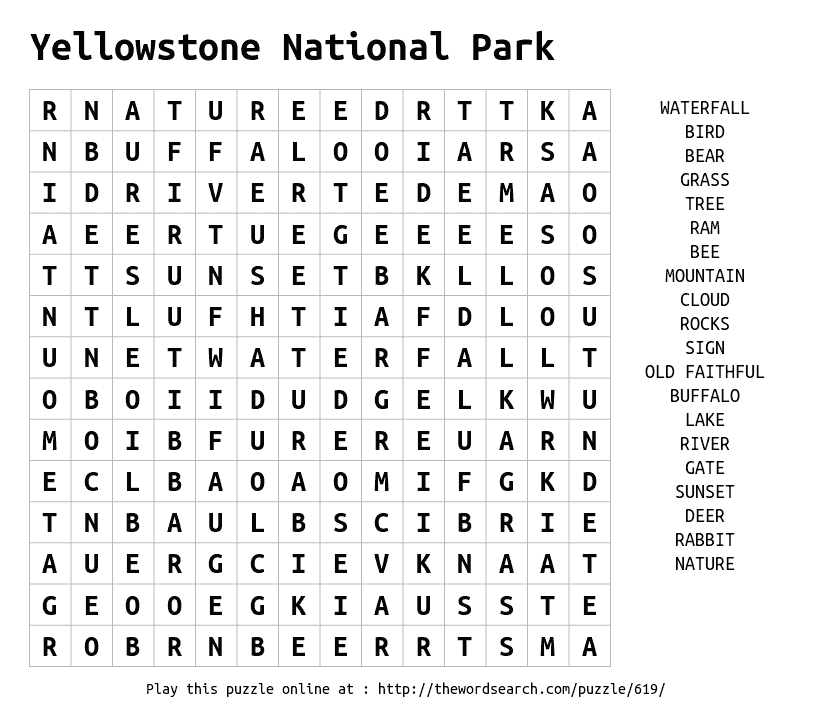

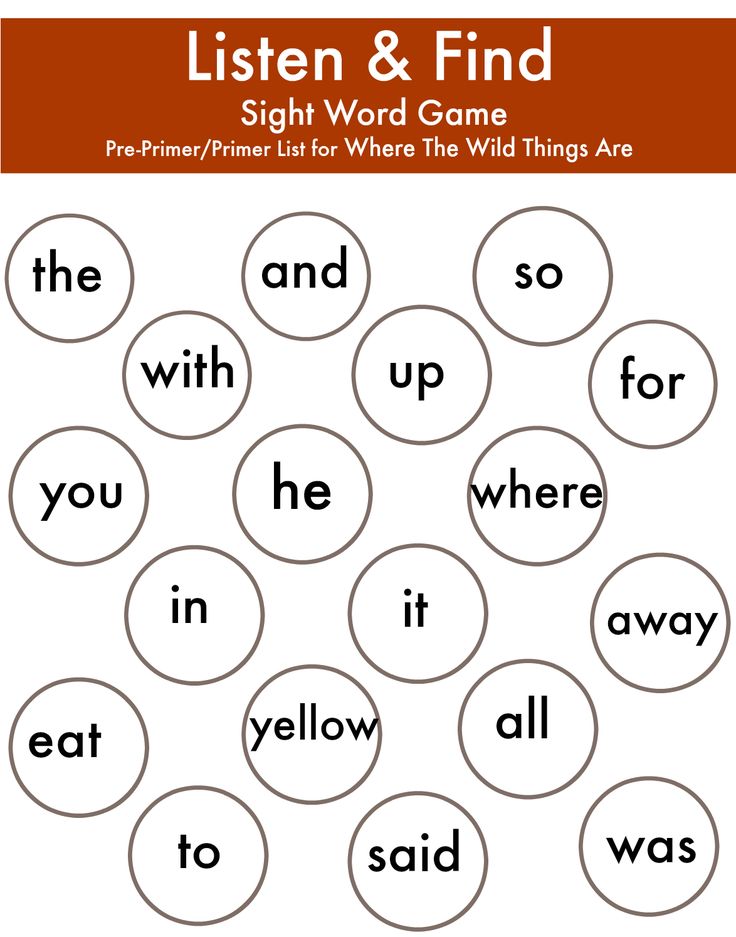

Learning to read can be difficult for early learners. Phonetically sounding out each word is a slow process that can hinder reading comprehension. Because of this, a list of 315 words has been developed and categorized as sight words.

The most widely accepted list of sight words is the Dolch Sight Words list. Comprised of 220 service words and 95 frequently occurring nouns, the list represents 80% of the words that would typically be found in children’s writings. Learning these words is a skill that will carry forwards as these words also represent 50% of the words found in adult writings.

Understanding and recognizing these words on sight will free students up to focus on pronouncing and understanding the remaining words in the text. These non-sight words will likely more specifically relate to the meaning of the text so this focus will increase reading comprehension.

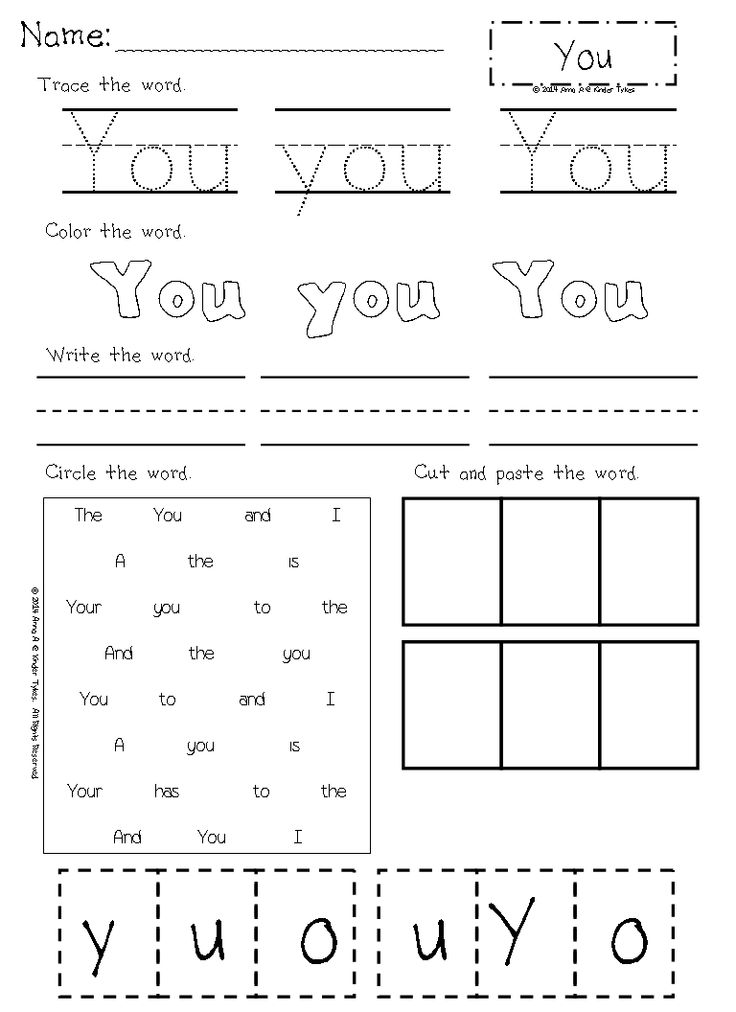

Repetition and memorization are paramount in learning sight words. Many of the common sight words are irregularly spelled words that would be difficult for early learners to phonetically sound out. Memorizing these words, their spellings, and their pronunciations can also help children as they encounter other irregularly spelled words. The vowel and consonant digraphs that make up these new sounds will be familiar to them because of the sight words.

The vowel and consonant digraphs that make up these new sounds will be familiar to them because of the sight words.

Using the resources provided by Education.com above may help students recognize and read these sight words, giving them the foundation necessary to become quality readers.

Teach Your Child to Read

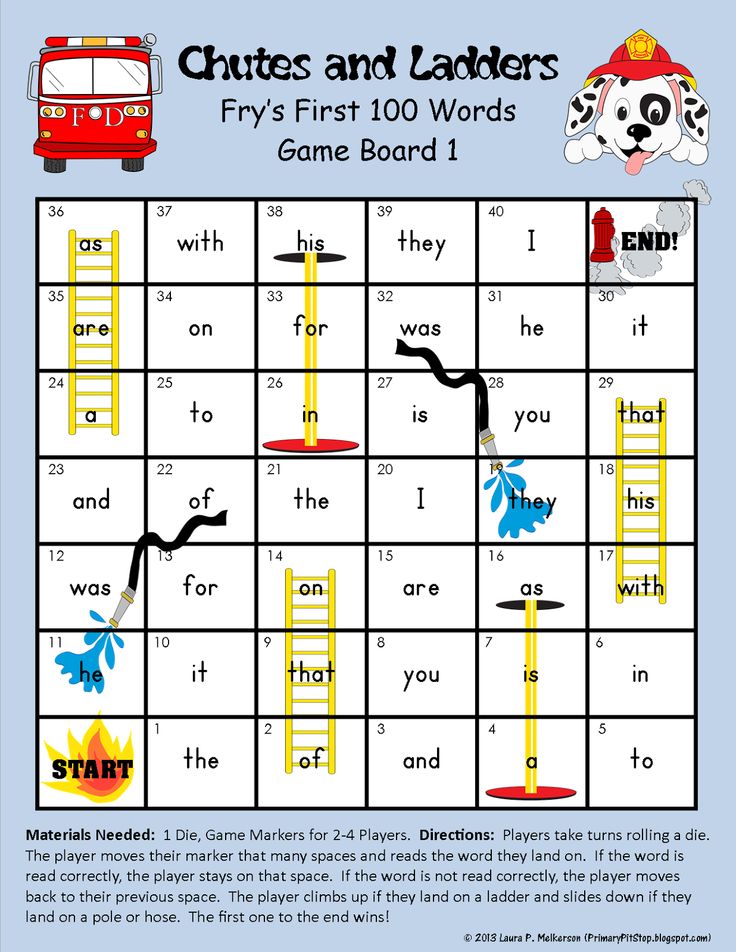

Print your own sight words flash cards. Create a set of Dolch or Fry sight words flash cards, or use your own custom set of words.

More

Follow the sight words teaching techniques. Learn research-validated and classroom-proven ways to introduce words, reinforce learning, and correct mistakes.

More

Play sight words games. Make games that create fun opportunities for repetition and reinforcement of the lessons.

More

Learn what phonological and phonemic awareness are and why they are the foundations of child literacy. Learn how to teach phonemic awareness to your kids.

More

A sequenced curriculum of over 80 simple activities that take children from beginners to high-level phonemic awareness. Each activity includes everything you need to print and an instructional video.

Each activity includes everything you need to print and an instructional video.

More

Teach phoneme and letter sounds in a way that makes blending easier and more intuitive. Includes a demonstration video and a handy reference chart.

More

Sightwords.com is a comprehensive sequence of teaching activities, techniques, and materials for one of the building blocks of early child literacy. This collection of resources is designed to help teachers, parents, and caregivers teach a child how to read. We combine the latest literacy research with decades of teaching experience to bring you the best methods of instruction to make teaching easier, more effective, and more fun.

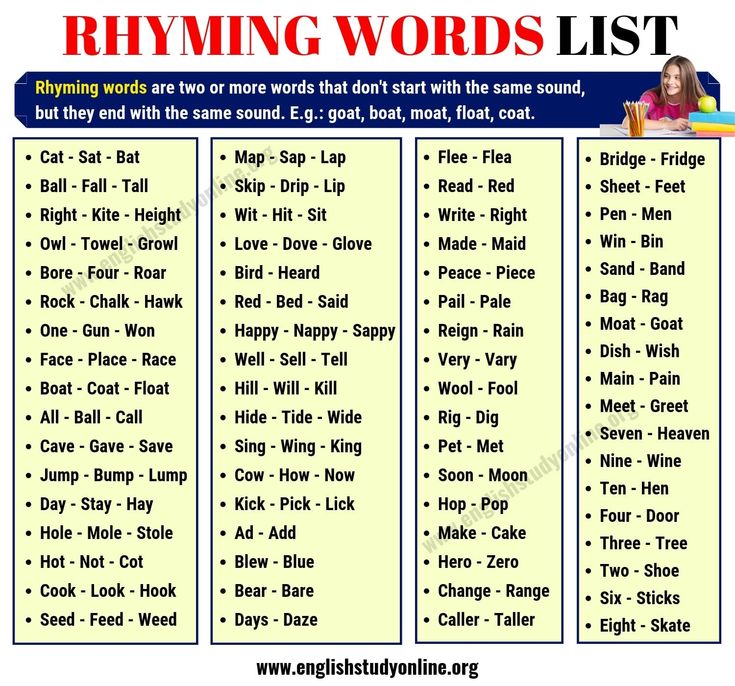

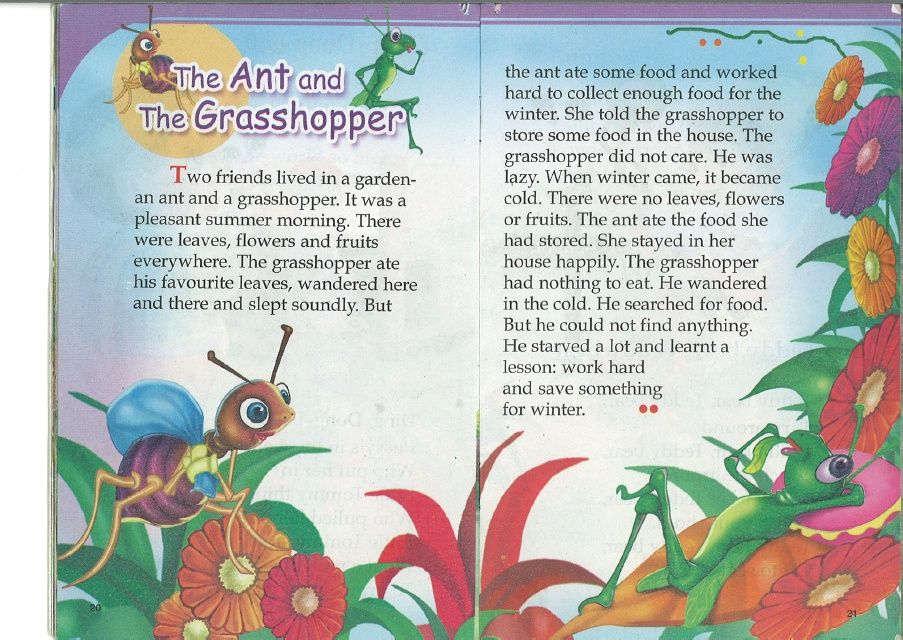

Sight words build speed and fluency when reading. Accuracy, speed, and fluency in reading increase reading comprehension. The sight words are a collection of words that a child should learn to recognize without sounding out the letters. The sight words are both common, frequently used words and foundational words that a child can use to build a vocabulary. Combining sight words with phonics instruction increases a child’s speed and fluency in reading.

Combining sight words with phonics instruction increases a child’s speed and fluency in reading.

This website includes a detailed curriculum outline to give you an overview of how the individual lessons fit together. It provides detailed instructions and techniques to show you how to teach the material and how to help a child overcome common roadblocks. It also includes free teaching aids, games, and other materials that you can download and use with your lessons.

Many of the teaching techniques and games include variations for making the lesson more challenging for advanced students, easier for new or struggling students, and just different for a bit of variety. There are also plenty of opportunities, built into the lessons and games, to observe and assess the child’s retention of the sight words. We encourage you to use these opportunities to check up on the progress of your student and identify weaknesses before they become real problems.

Help us help you. We want this to be a resource that is constantly improving. So please provide us with your feedback, both the good and the bad. We want to know which lessons worked for your child, and which fell short. We encourage you to contribute your own ideas that have worked well in the home or classroom. You can communicate with us through email or simply post a response in the comments section of the relevant page.

We want this to be a resource that is constantly improving. So please provide us with your feedback, both the good and the bad. We want to know which lessons worked for your child, and which fell short. We encourage you to contribute your own ideas that have worked well in the home or classroom. You can communicate with us through email or simply post a response in the comments section of the relevant page.

Excerpt from the book "Wordplay" by translator Vladimir Babkov - Snob

"Jean Mielo at his desk". 2nd half of the 15th century. Unknown miniaturist

Photo: Royal Library of Brussels / Wikipedia

The simplest definition of synonyms is as follows: these are words that are spelled and sound differently, but have the same or close meanings. Strictly speaking, for our purposes, it would have to be slightly modified, since we are interested not only in the direct meaning of each word, but also in all its “side” properties (in particular, how it is written and pronounced), and the latter sometimes turn out to be slightly is not more important than the first. It follows from this that two synonyms that are absolutely identical in the sense we need do not exist. One could reformulate the standard definition and say that synonyms are words that perform approximately the same role in a literary text, or define them even more briefly as interchangeable words (and sometimes combinations of words). But I suggest not to strive for scientific accuracy, otherwise we will get completely confused. Let's stick to the classical definition, let's just take into account that a) even when replacing a single word in a phrase with another, closest to it in direct meaning, this phrase changes, sometimes dramatically, and b) on the contrary, in a literary text even very distant from each other in the actual meaning of the words can be quite interchangeable. Try, for example, to replace any word in a phrase from some official document (and such a phrase can also be found in a novel) with its colloquial or dialectal counterpart, and you will see the validity of the first clause.

It follows from this that two synonyms that are absolutely identical in the sense we need do not exist. One could reformulate the standard definition and say that synonyms are words that perform approximately the same role in a literary text, or define them even more briefly as interchangeable words (and sometimes combinations of words). But I suggest not to strive for scientific accuracy, otherwise we will get completely confused. Let's stick to the classical definition, let's just take into account that a) even when replacing a single word in a phrase with another, closest to it in direct meaning, this phrase changes, sometimes dramatically, and b) on the contrary, in a literary text even very distant from each other in the actual meaning of the words can be quite interchangeable. Try, for example, to replace any word in a phrase from some official document (and such a phrase can also be found in a novel) with its colloquial or dialectal counterpart, and you will see the validity of the first clause. We have already seen examples illustrating the second when discussing the limits of translational freedom, and we will soon see new ones. nine0005

We have already seen examples illustrating the second when discussing the limits of translational freedom, and we will soon see new ones. nine0005

Even if we do not take into account words that are formally synonyms, but are too far from each other in stylistic coloring, our language is so rich that almost every word in an arbitrary Russian phrase can be found a completely acceptable replacement - and, as a rule, more than one . If, on the other hand, we include in the synonymic series and cognate words that differ only in suffixes (which is not only legal for the translator, but also necessary), they will become even longer.

Let's play some numbers. If every word in a small phrase—say, ten words—has at least three suitable synonyms, then the number of possible translations for the entire phrase is over a million: four to the tenth power, or 1,048,576. To calculate the number of possible translations English phrase of the appropriate length, this number should be increased at least several (or even several dozen) times, because there are often many more synonyms for words, and the syntactic structure of the translated phrase can be different. By the way, this means that the probability of two translations of the same phrase by different people being identical is practically zero. That is why it is so easy to recognize plagiarism in our business: even if a cunning student takes the trouble to change two or three words in each phrase he has copied from a friend, his dishonesty is unmistakably determined at a glance at both translations. nine0005

By the way, this means that the probability of two translations of the same phrase by different people being identical is practically zero. That is why it is so easy to recognize plagiarism in our business: even if a cunning student takes the trouble to change two or three words in each phrase he has copied from a friend, his dishonesty is unmistakably determined at a glance at both translations. nine0005

Let's leave the syntax aside and focus only on the vocabulary. How to choose the best translation of a phrase from all possible options, and is there one at all? Before trying to answer this question, let's discuss another, easier one: where do we look for synonyms for the words that make up our phrase?

The answer "on the Internet" is incorrect for several reasons. First: diving into the Internet for synonyms, albeit not every, but at least every fifth Russian word that comes to our mind, there is no physical possibility. Second: constantly turning to the Internet for synonyms is an admission of one's writing incompetence, not to say unsuitability. After all, not so long ago there was no Internet at all, and writers (who, of course, have the problem of choosing the most suitable words no less acute than translators) managed to write excellent books without it. You might argue that paper dictionaries used to replace Internet authors. Perhaps you even know that there are special dictionaries of synonyms in the world. Moreover, if not in Russian, then in English there are dictionaries designed specifically for writers (in the broad sense of the word), - for example, Roget’s Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases is a very good Thesaurus. Well, writers do use dictionaries, and sometimes quite willingly. However, they are much more willing to use their own heads, and in this respect, we, translators, should strive not only to catch up with them, but also to overtake them: after all, in terms of vocabulary, we should be the same generalists as in terms of stylistic devices. The hunt for new words contributes only to a very small extent to achieving this universality.

After all, not so long ago there was no Internet at all, and writers (who, of course, have the problem of choosing the most suitable words no less acute than translators) managed to write excellent books without it. You might argue that paper dictionaries used to replace Internet authors. Perhaps you even know that there are special dictionaries of synonyms in the world. Moreover, if not in Russian, then in English there are dictionaries designed specifically for writers (in the broad sense of the word), - for example, Roget’s Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases is a very good Thesaurus. Well, writers do use dictionaries, and sometimes quite willingly. However, they are much more willing to use their own heads, and in this respect, we, translators, should strive not only to catch up with them, but also to overtake them: after all, in terms of vocabulary, we should be the same generalists as in terms of stylistic devices. The hunt for new words contributes only to a very small extent to achieving this universality. We already know almost all the words that can be useful to us: if you still look for the necessary synonymous series on the Internet, do you often come across completely unfamiliar words in it? But if you just find the right word on the Internet, it will very soon return to the shelf in the far corner of your personal vocabulary. It is much more useful to strain your brains and remember it yourself - then the second time it will turn out faster, and then it will not require any special efforts at all. An experienced translator, at the sight of an English word known to him, immediately recalls not its only Russian equivalent, but a whole series of synonyms, and very quickly, almost automatically, chooses a better word from this series. nine0005

We already know almost all the words that can be useful to us: if you still look for the necessary synonymous series on the Internet, do you often come across completely unfamiliar words in it? But if you just find the right word on the Internet, it will very soon return to the shelf in the far corner of your personal vocabulary. It is much more useful to strain your brains and remember it yourself - then the second time it will turn out faster, and then it will not require any special efforts at all. An experienced translator, at the sight of an English word known to him, immediately recalls not its only Russian equivalent, but a whole series of synonyms, and very quickly, almost automatically, chooses a better word from this series. nine0005

There is a third reason why searching for synonyms on the Internet or paper dictionaries is not only ineffective, but also harmful, and it is especially relevant for translators. Translating another book, we always remain under its influence - in the words of Wells, "in a tiny bright world, completely cut off from everyday reality" (however, this world is sometimes a gray and rather gloomy place, but for some reason we are still drawn there ). Staying in the atmosphere created by the author is the most important condition for our success. Only under strict observance of this condition are we able to invent Russian phrases that are correct in spirit. With regard to vocabulary, this means that not all members of the synonymic series automatically come to mind, but only those that correspond to our text in style. The Internet offers these series in full; in this sense, he is like a conscientious idiot who goes out of his way to give helpful advice. At best, this can amuse us, but the desired mood will be lost in this case - as a rule, with sad consequences. So I would advise you to turn to the Internet only when you almost know exactly what you are looking for - when the word you need is, as they say, spinning on the tongue, but you just can’t remember it and are already seriously annoyed by this. Then your gaze will be more targeted, and you will immediately catch the cherished solution from the proposed list. nine0005

Staying in the atmosphere created by the author is the most important condition for our success. Only under strict observance of this condition are we able to invent Russian phrases that are correct in spirit. With regard to vocabulary, this means that not all members of the synonymic series automatically come to mind, but only those that correspond to our text in style. The Internet offers these series in full; in this sense, he is like a conscientious idiot who goes out of his way to give helpful advice. At best, this can amuse us, but the desired mood will be lost in this case - as a rule, with sad consequences. So I would advise you to turn to the Internet only when you almost know exactly what you are looking for - when the word you need is, as they say, spinning on the tongue, but you just can’t remember it and are already seriously annoyed by this. Then your gaze will be more targeted, and you will immediately catch the cherished solution from the proposed list. nine0005

And now it's time to finally discuss the main thing: how to choose the best words from the synonymous series. It would be most logical to borrow the algorithm for this procedure from our role model (it seems that this tracing paper is already firmly stuck in the Russian language) - namely, from the author of the original. The choice of words is an element of style, one of the components of writing technique, and we need to adopt it from writers.

It would be most logical to borrow the algorithm for this procedure from our role model (it seems that this tracing paper is already firmly stuck in the Russian language) - namely, from the author of the original. The choice of words is an element of style, one of the components of writing technique, and we need to adopt it from writers.

However, writers behave quite differently in this respect. Someone seems to be spitting words through his teeth, like a real macho, making do with a deliberately meager vocabulary, and someone flaunts his erudition, now and then taking out such boustrophedons and popokatepetli from his bosom, which we never dreamed of even in the most terrible dreams. Is there anything in common between the writers, or does the translator have to try on a new author every time, trying to unravel his special system? nine0005

I would answer yes to both parts of this question. Or rather, like this: if we do not take into account pronounced marginals, we will notice that with regard to lexical choice, most writers adhere to the golden mean, that is, they prefer words that are not the rarest, but not the most worn (I would say "not the most hackneyed" but I'm sorry to beat the words). And the reasons for this are quite understandable. As a rule, a good writer is not concerned with creating his own unique image in the eyes of the public, but with telling readers an interesting and important story for himself. If you tell this story in the most simple and familiar words, you can win in persuasiveness, but there is a risk that the reader will quickly get bored, and even accuse the author of incompetence or lack of effort. If, however, you constantly surprise the reader with exotic vocabulary, it will be difficult for him to follow the development of the plot, and in addition, he may suspect that the author wants to demonstrate his superiority over him, and this causes understandable irritation. Therefore, writers most often choose the middle way, using not the most standard, but not too outlandish words. nine0005

And the reasons for this are quite understandable. As a rule, a good writer is not concerned with creating his own unique image in the eyes of the public, but with telling readers an interesting and important story for himself. If you tell this story in the most simple and familiar words, you can win in persuasiveness, but there is a risk that the reader will quickly get bored, and even accuse the author of incompetence or lack of effort. If, however, you constantly surprise the reader with exotic vocabulary, it will be difficult for him to follow the development of the plot, and in addition, he may suspect that the author wants to demonstrate his superiority over him, and this causes understandable irritation. Therefore, writers most often choose the middle way, using not the most standard, but not too outlandish words. nine0005

Let's sum it up. If, with regard to the choice of vocabulary, the author of the book you are translating belongs to the conditional "middle peasants" (and the probability of this is quite high), then the most correct thing to do is to compose the necessary synonymous rows in your mind, arrange the words in them according to the frequency of use, from high to low (in this sequence we usually remember them), and look for a suitable word somewhere in the middle. If you notice that your author deviates from such a moderate lexical variety in one direction or another (I am talking here only about the use of words, but not about their stylistic coloring), you have no choice but to follow him. nine0005

If you notice that your author deviates from such a moderate lexical variety in one direction or another (I am talking here only about the use of words, but not about their stylistic coloring), you have no choice but to follow him. nine0005

You might get the impression that those writers who tend to use more primitive or more sophisticated vocabulary always make a mistake. This is not true. The writer may pretend to be direct and direct, or may be; can pretend to be a clever man and an erudite, or maybe he is. If you feel that the writer's unusual vocabulary is an organic element of his personality, that's all right - reproduce this unusualness, and the reader of your translation will also find it appropriate. We must also take into account the fact that the authors very often deliberately hide behind a specially invented mask, even if they are telling the story not from the first, but from the third person, from the point of view of an outside observer. Some also change their masks - this technique is very popular among postmodernists. So the golden mean, as applied to vocabulary, is nothing more than a guideline, the very fulcrum that allows the translator Archimedes to find the optimal position in space for his planet. nine0005

So the golden mean, as applied to vocabulary, is nothing more than a guideline, the very fulcrum that allows the translator Archimedes to find the optimal position in space for his planet. nine0005

Let's try to figure out one more thing: why, even with more or less similar tactics, we still choose such different words for our translations? Sometimes one simply wonders when looking at a dozen translations of the same short prose fragment: it seems that they have absolutely nothing in common. This is probably due to the fact that we treat words very differently - and not only because we differ from each other in age, character, upbringing, education, and so on, but also because each of us has a backpack behind us. with a unique life experience. In every word that we use, a colossal amount of impressions and memories associated with it is sewn up; our attitude to any particular word is largely determined by the situation in which and from whom (and where) we heard (or read) it for the first time, by what exactly it meant then, and even by what mood we were then, and this is true not only for those words that we use relatively rarely. Even the most popular words, as a rule, evoke quite definite and sometimes very different associations in us. If a character in an English book is riding a bicycle down the street, we will all imagine different bicycles and different streets while reading it; his bicycle will be similar to our own or the neighbor's, the street - to ours or the one along which we recently walked during a trip abroad. Well, so what, you say; a bicycle is a bicycle in Africa, and a street in the village of Khryukino is a street. These words will be included in the translation. nine0005

Even the most popular words, as a rule, evoke quite definite and sometimes very different associations in us. If a character in an English book is riding a bicycle down the street, we will all imagine different bicycles and different streets while reading it; his bicycle will be similar to our own or the neighbor's, the street - to ours or the one along which we recently walked during a trip abroad. Well, so what, you say; a bicycle is a bicycle in Africa, and a street in the village of Khryukino is a street. These words will be included in the translation. nine0005

You're probably right about that. If we talk about the translation of nouns, the translator usually does not have a wide choice (although you can almost always play around with suffixes). But there is a part of speech in the language that is especially sensitive to our individual differences and, moreover, plays an extremely important role in any artistic text. This is another adjective. It makes sense to talk more about how to translate adjectives - or epithets.

Spy "hello": what the former British agent teaches liberals | Article

The title of the work of the former director of the Government Communications Center and Deputy Home Secretary of Great Britain may suggest a documentary spy thriller. But Target Thinking is more like detailed lecture notes that the author gives at the Department of Military Studies at King's College London, at the Institute of Political Studies in Paris, and at the Defense University in Oslo. Lidia Maslova, a critic who is not indifferent to the elderly knights of the cloak, dagger and the Grand Cross of the Most Honorable Order of the Bath (was bestowed upon the author before retiring from service), could not pass by and presents the book of the week, especially for Izvestia. nine0005

Aimed thinking: Decision making according to the methods of British intelligence services

Moscow: Alpina Publisher, 2022. - trans. from English. — 376 p.

Omand carefully lists all other places of his previous activity, outlining an enviable career in British defense and intelligence institutions: from a cryptanalyst at the Government Communications Center, where he got in 1969, up to the head of this institution and "the first ever coordinator for UK Security and Intelligence" with the rank of Deputy Minister. nine0038 Of course, Omand was more involved in desk-analytical work than in the field, so it would be incorrect to consider him a "spy" in the everyday, pop-cultural sense of the word. Apparently, this is why Russian publishers refused the opportunity to translate the title of the book (How Spies Think) closer to the original and more invitingly - "Think like a spy", and limited themselves to careful "Aimed Thinking".

nine0038 Of course, Omand was more involved in desk-analytical work than in the field, so it would be incorrect to consider him a "spy" in the everyday, pop-cultural sense of the word. Apparently, this is why Russian publishers refused the opportunity to translate the title of the book (How Spies Think) closer to the original and more invitingly - "Think like a spy", and limited themselves to careful "Aimed Thinking".

It, in principle, correctly conveys the approach of the author, who advises both in intelligence, and in business, and in personal life to carefully aim and not get excited with conclusions, according to the principle "measure seven times - cut once." nine0038 This particular proverb is not in the book, but there is a related one, which also promotes prudence: "Trust, but verify." According to Omand, "President Reagan grew fond of this proverb during his years of seeking arms control agreements with the Soviet Union."

Spy hello_1

David Omand

Photo: NATO

The original subtitle of Ten Lessons in Intelligence plays on the fact that intelligence and intelligence are the same word in English. nine0038 Professor Omand diligently puts the promised lessons on the shelves, but in their wording one can hear either banality (“Lesson 1. Our knowledge of the world is always fragmentary and incomplete, and sometimes incorrect”), or a utopian dream (“Lesson 3. Suddenness should not be shock to us”), then a pessimistic recognition of the limitations of human thinking (“Lesson 5. We are likely to be misled by our own demons”).

nine0038 Professor Omand diligently puts the promised lessons on the shelves, but in their wording one can hear either banality (“Lesson 1. Our knowledge of the world is always fragmentary and incomplete, and sometimes incorrect”), or a utopian dream (“Lesson 3. Suddenness should not be shock to us”), then a pessimistic recognition of the limitations of human thinking (“Lesson 5. We are likely to be misled by our own demons”).

Lesson 10 "Subversion and Incitement: Now Digital", the emotional finale that the book seems to have been written for, does not teach any thought techniques or techniques at all. It is dedicated to exposing the intrigues of manipulators from “autocratic states” that have bred on the Internet, who continually strive to spoil the course of democratic elections in free countries. nine0038 On this topic, in the last chapter, Omand winds himself up rather energetically, drawing nightmarish dystopian pictures of 2027, when revolutionaries come to power in Britain as a result of carefully planned cyber attacks by foreign spies and saboteurs:

Quote author

but this was the year in which the British, in the wake of environmental populism and rejection of traditional representative democracy, elected a revolutionary administration by a tiny majority”

Having properly frightened readers with an apocalyptic forecast, Omand urges them to be vigilant in cyberspace, not to succumb to provocations and not to believe in network stuffing - this is the only way to preserve liberal values.

Spy hello_2

Photo: Depositphotos/blasbike

But amid Cold War rhetoric and bland analytics (using vintage tools like Bayes' theorem and Occam's razor), there are some touching genre scenes from espionage life in the book. Even if Omand himself did not participate in them, he describes them as a historian. nine0037 For example, the meeting of GRU Colonel Oleg Penkovsky with MI6 officers at the Mount Royal Hotel in London on April 20, 1961. Having handed over “two packs of handwritten information about Soviet missiles and other military secrets” to the waiting agents, Penkovsky decides to get moral satisfaction immediately and eats away the brains of the poor British for a long time:

Quote

that he considered it necessary to expose Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev's adventurism and brinkmanship policy to the West and explained the true nature of what he called the "rotten duplicitous Soviet regime" he served and his patriotic duty to Mother Russia" nine0005

This is not the only time when the Russian translation of the book suffers from grammatical inconsistencies. But even if the editing were more thorough, it would hardly add to the ease of reading. "Sighted Thinking" is mostly written in boring lecturer's language, and the anonymous translation further exacerbates the clerical style. For example, every now and then an unnecessary word "presence" or "present" in the most cumbersome context comes across:

But even if the editing were more thorough, it would hardly add to the ease of reading. "Sighted Thinking" is mostly written in boring lecturer's language, and the anonymous translation further exacerbates the clerical style. For example, every now and then an unnecessary word "presence" or "present" in the most cumbersome context comes across:

Quote author

“My experience is that having a methodology to analyze the decision-making process and establish an appropriate level of trust in them really helps in the work.”

Photo: Alpina Publisher

, Omand rarely remembers the promise he made at the beginning - to show how the principles of spy thinking can be applied to the business and personal life of an ordinary person. nine0038 Sometimes a British analyst does catch on and, for example, draws a parallel between an arms race and manifestations of jealousy: jealous. One day, Alice catches Bob with her phone reading text messages.

Learn more