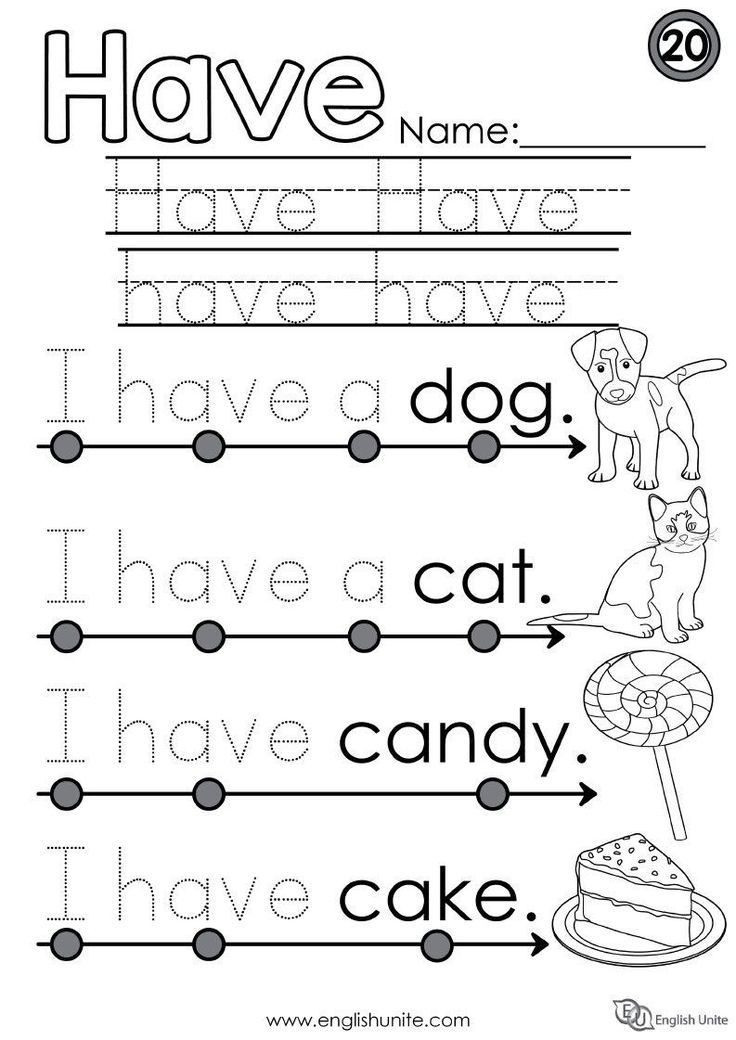

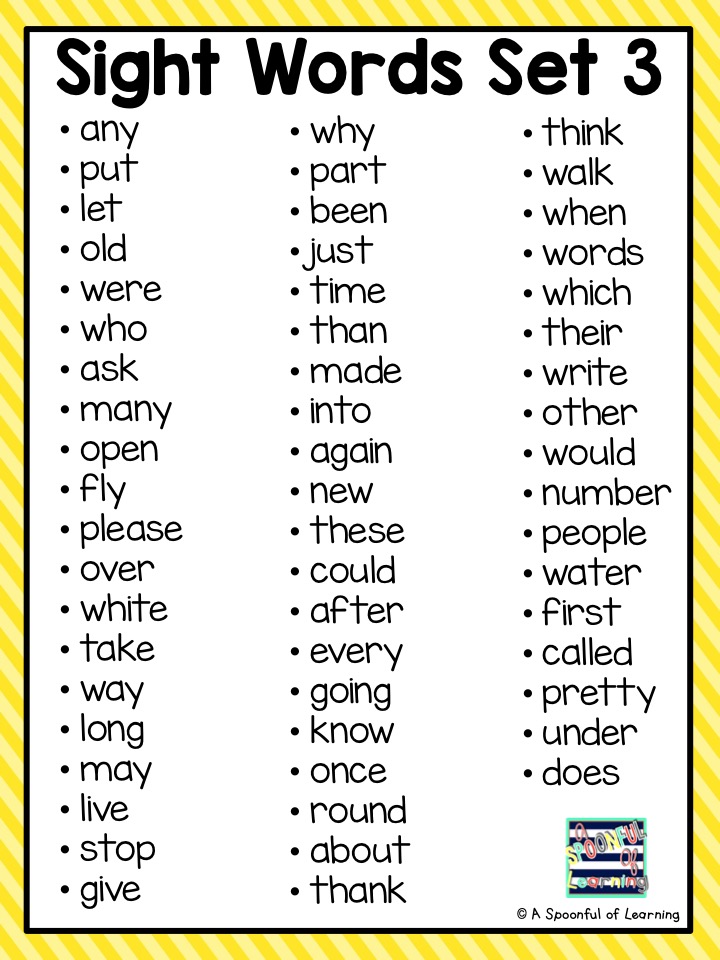

Sight words have

Sight Words Teaching Strategy | Sight Words: Teach Your Child to Read

A child sees the word on the flash card and says the word while underlining it with her finger.

The child says the word and spells out the letters, then reads the word again.

The child says the word and then spells out the letters while tapping them on her arm.

A child says the word, then writes the letters in the air in front of the flash card.

A child writes the letters on a table, first looking at and then not looking at the flash card.

Correct a child’s mistake by clearly stating and reinforcing the right word several times.

- Overview

- Plan a Lesson

- Teaching Techniques

- Correcting Mistakes

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Questions and Answers

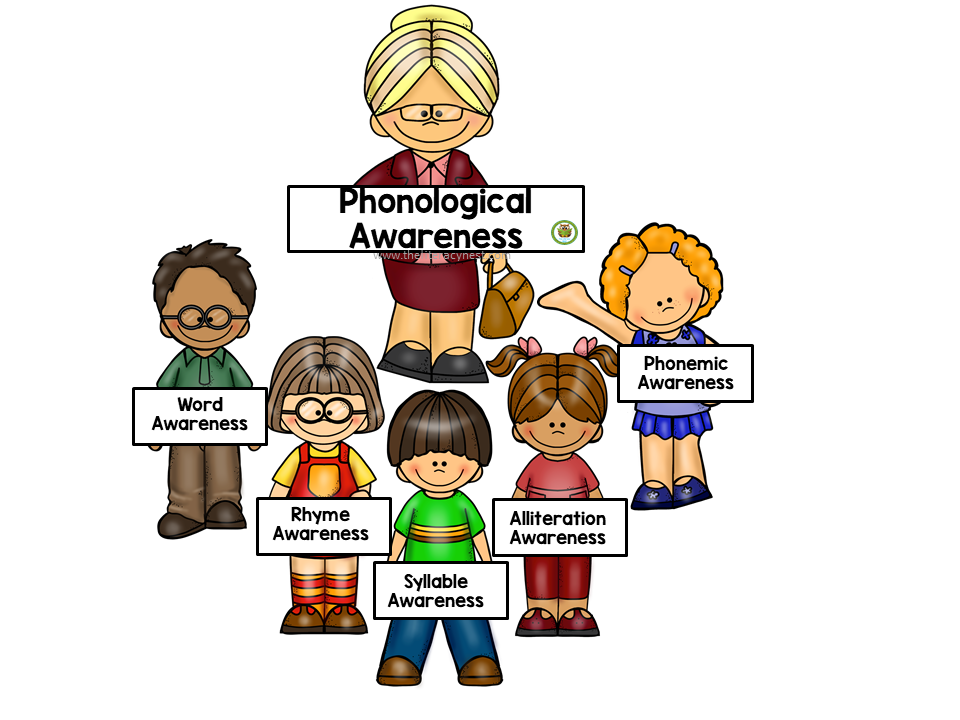

Sight words instruction is an excellent supplement to phonics instruction. Phonics is a method for learning to read in general, while sight words instruction increases a child’s familiarity with the high frequency words he will encounter most often.

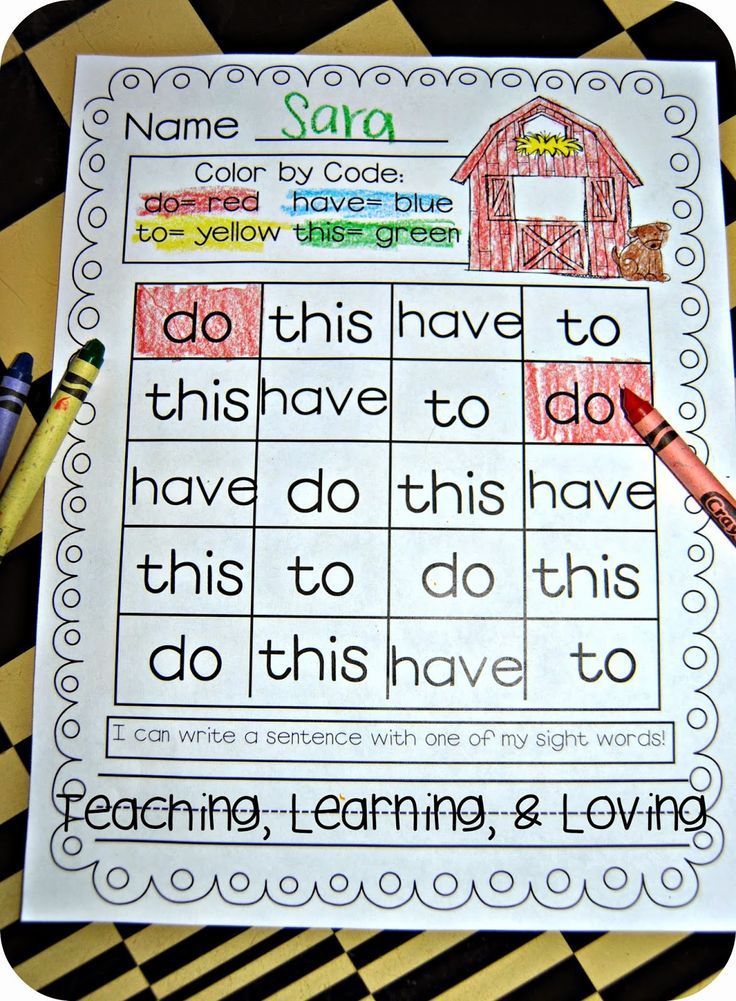

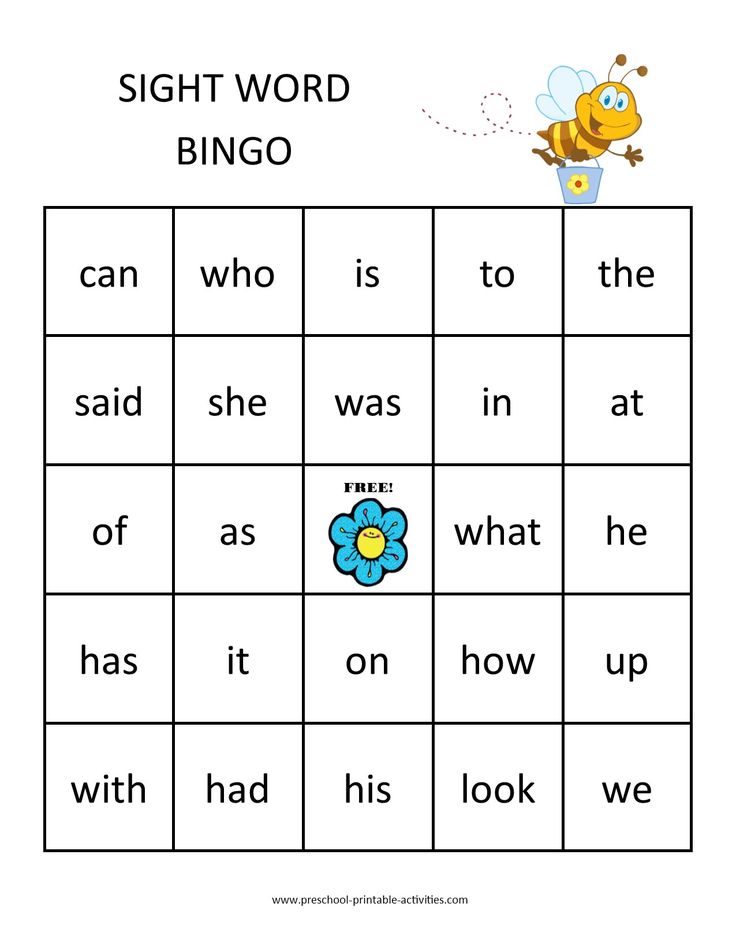

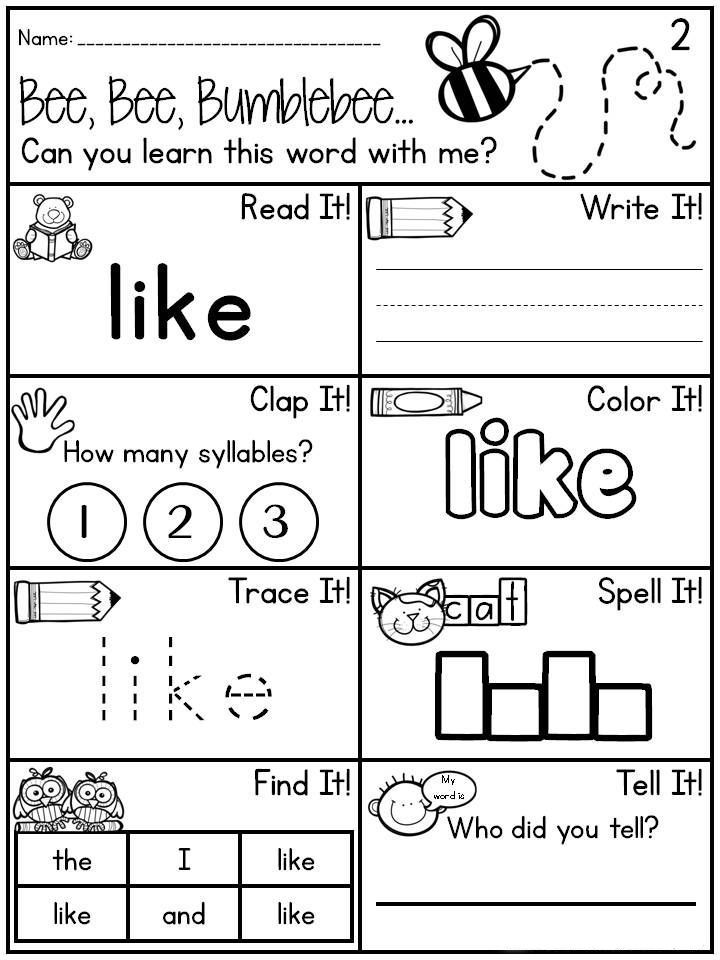

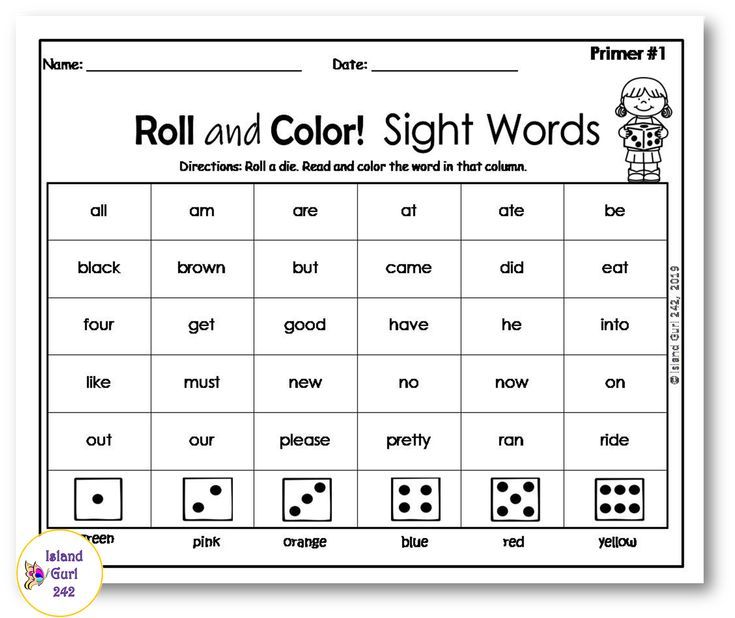

Use lesson time to introduce up to three new words, and use game time to practice the new words.

A sight words instruction session should be about 30 minutes long, divided into two components:

- Sight Words Lesson — Use our Teaching Techniques to introduce new words and to review words from previous lessons — 10 minutes

- Sight Words Games — Use our games to provide reinforcement of the lesson and some review of already mastered sight words to help your child develop speed and fluency — 20 minutes

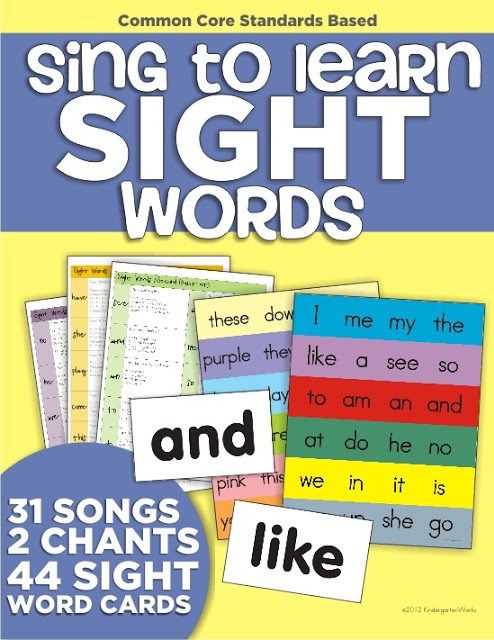

Video: Introduction to Teaching Sight Words

↑ Top

2.

1 Introduce New Words

1 Introduce New Words

When first beginning sight words, work on no more than three unfamiliar words at a time to make it manageable for your child. Introduce one word at a time, using the five teaching techniques. Hold up the flash card for the first word, and go through all five techniques, in order. Then introduce the second word, and go through all five teaching techniques, and so on.

This lesson should establish basic familiarity with the new words. This part of a sight words session should be brisk and last no more than ten minutes. As your child gets more advanced, you might increase the number of words you work on in each lesson.

2.2 Review Old Words

Begin each subsequent lesson by reviewing words from the previous lesson. Words often need to be covered a few times for the child to fully internalize them. Remember: solid knowledge of a few words is better than weak knowledge of a lot of words!

Go through the See & Say exercise for each of the review words. If your child struggles to recognize a word, cover that word again in the main lesson, going through all five teaching techniques. If he has trouble with more than two of the review words, then set aside the new words you were planning to introduce and devote that day’s lesson to review.

If your child struggles to recognize a word, cover that word again in the main lesson, going through all five teaching techniques. If he has trouble with more than two of the review words, then set aside the new words you were planning to introduce and devote that day’s lesson to review.

Note: The child should have a good grasp of — but does not need to have completely mastered — a word before it gets replaced in your lesson plan. Use your game time to provide lots of repetition for these words until the child has thoroughly mastered them.

2.3 Reinforce with Games

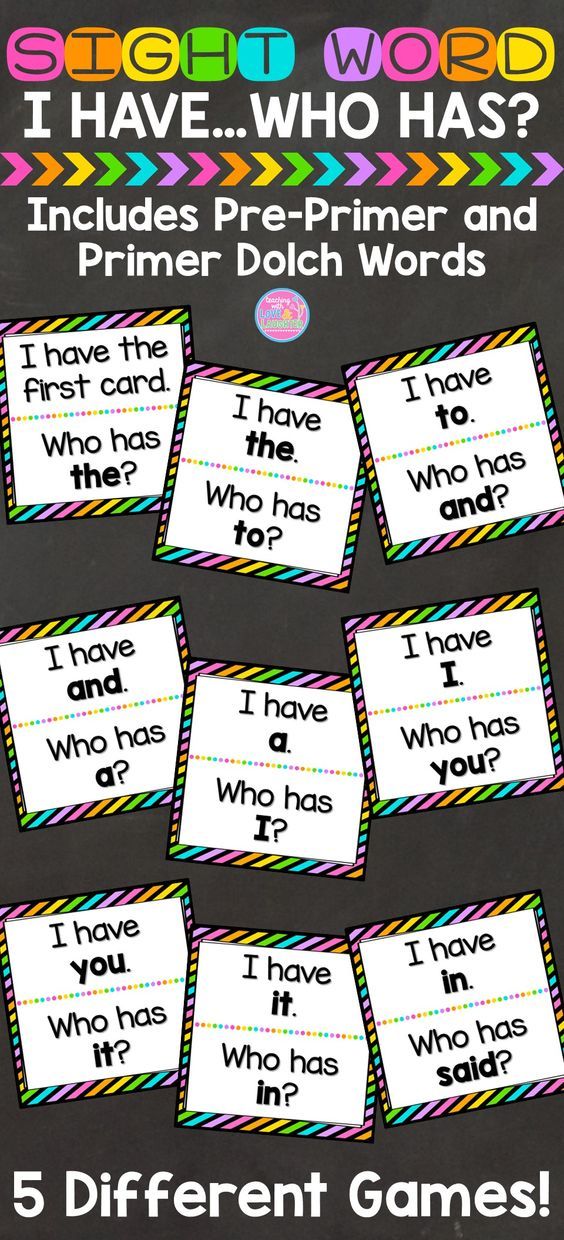

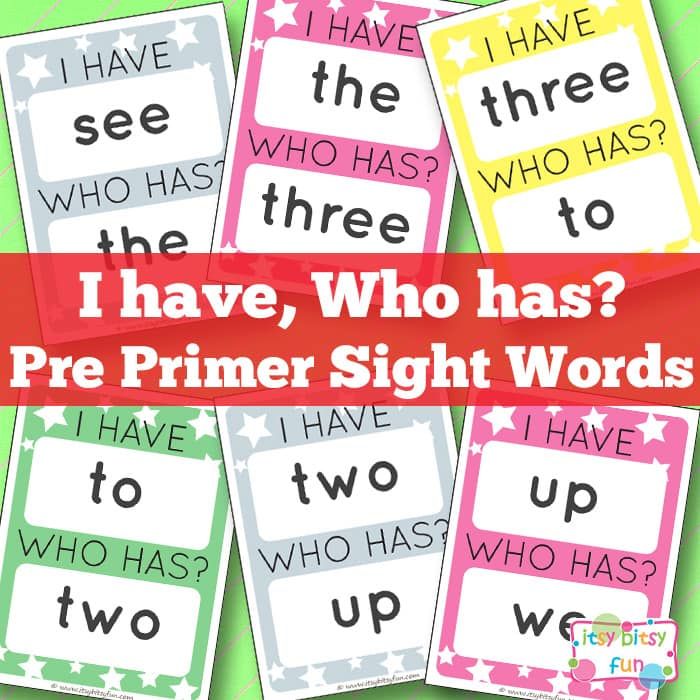

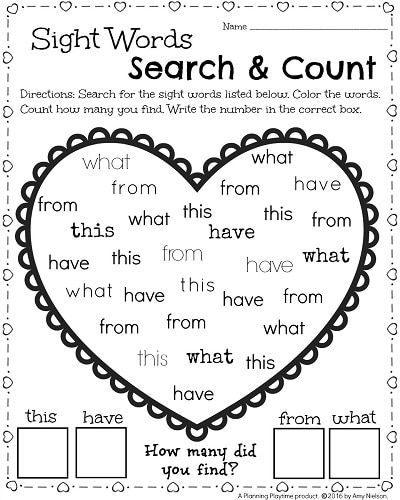

Learning sight words takes lots of repetition. We have numerous sight words games that will make that repetition fun and entertaining for you and your child.

The games are of course the most entertaining part of the sight words program, but they need to wait until after the first part of the sight words lesson.

Games reinforce what the lesson teaches.

Do not use games to introduce new words.

NOTE: Be sure the child has a pretty good grasp of a sight word before using it in a game, especially if you are working with a group of children. You do not want one child to be regularly embarrassed in front of his classmates when he struggles with words the others have already mastered!

↑ Top

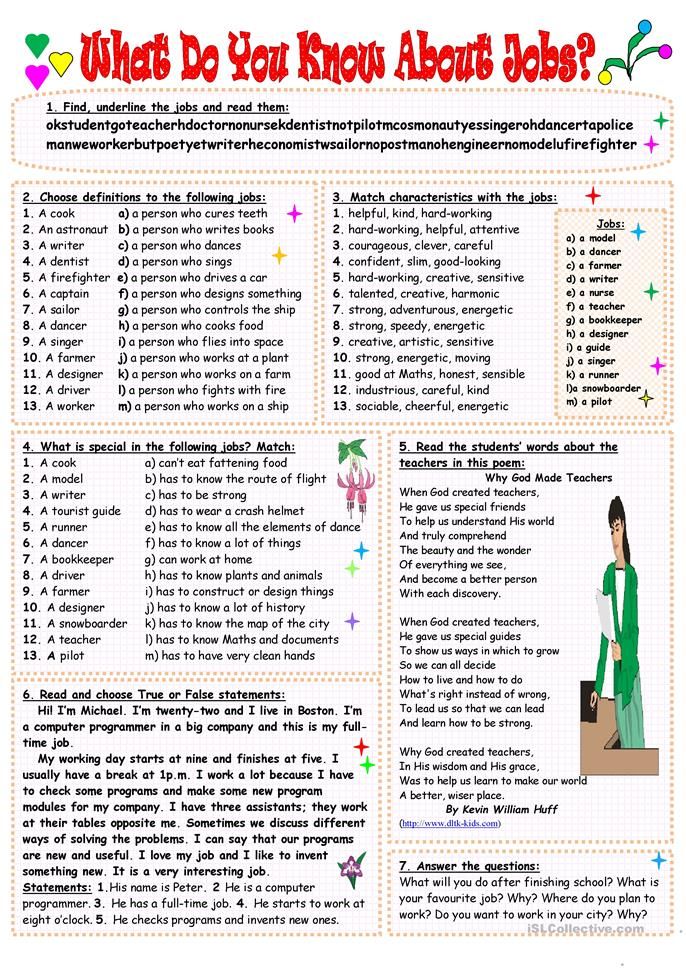

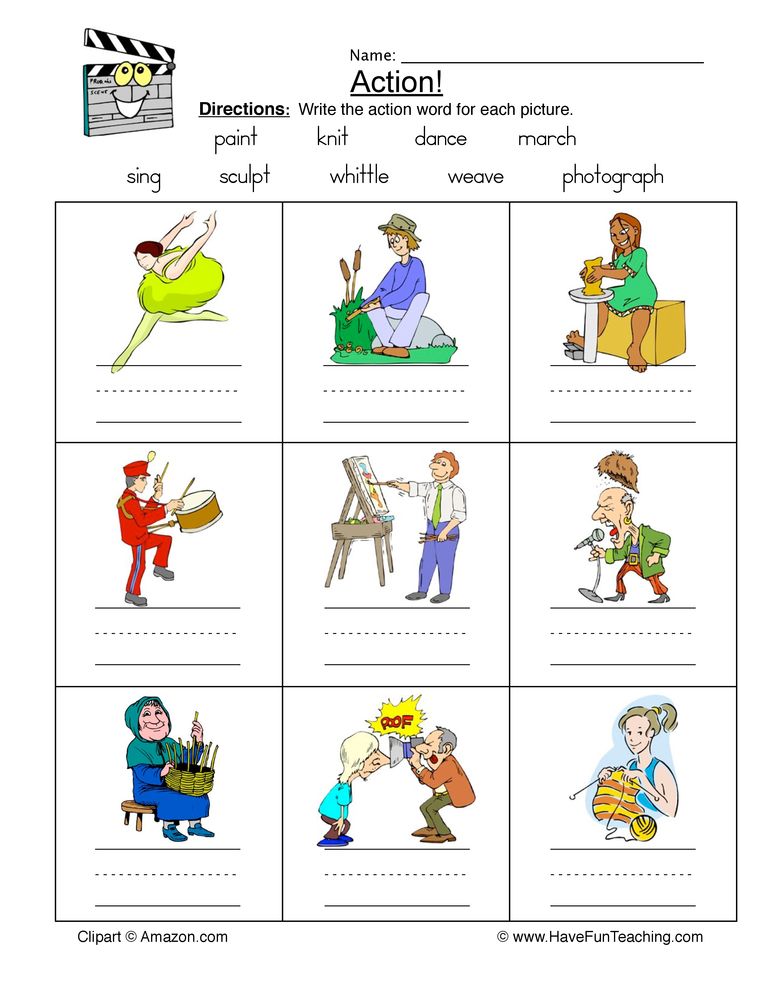

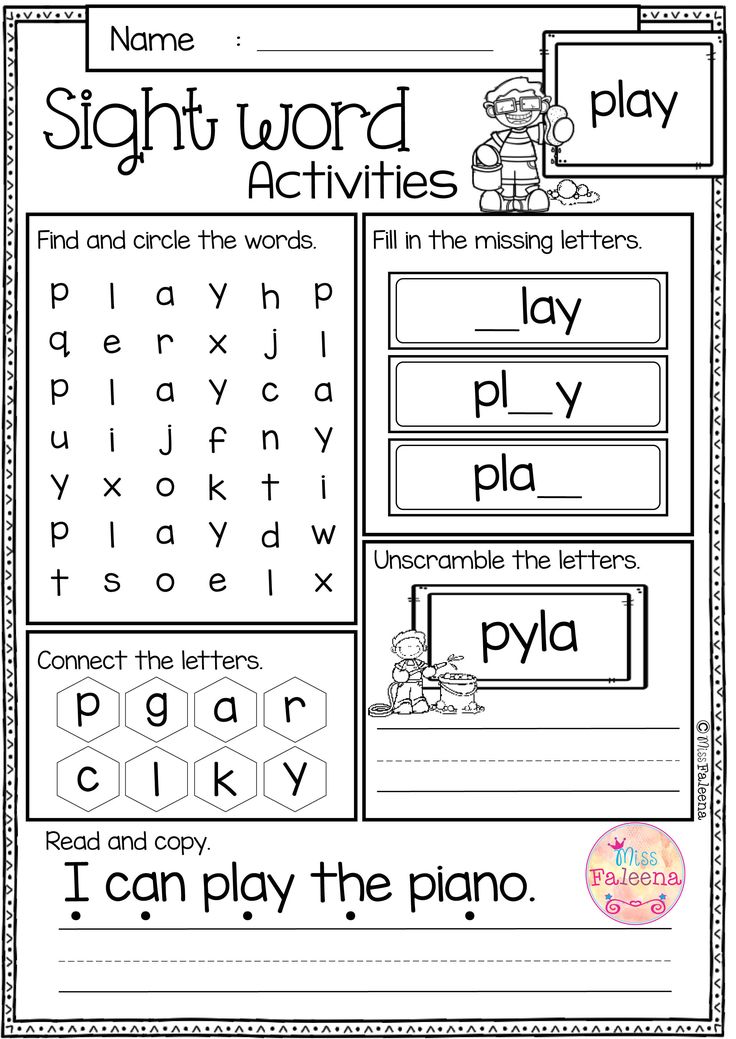

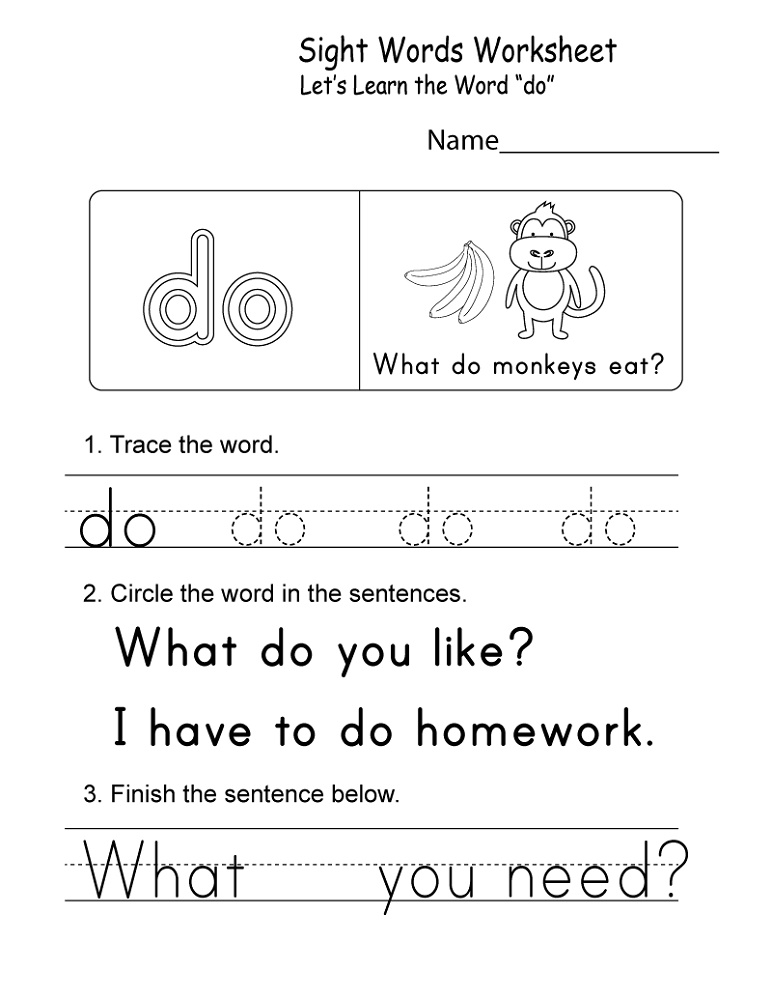

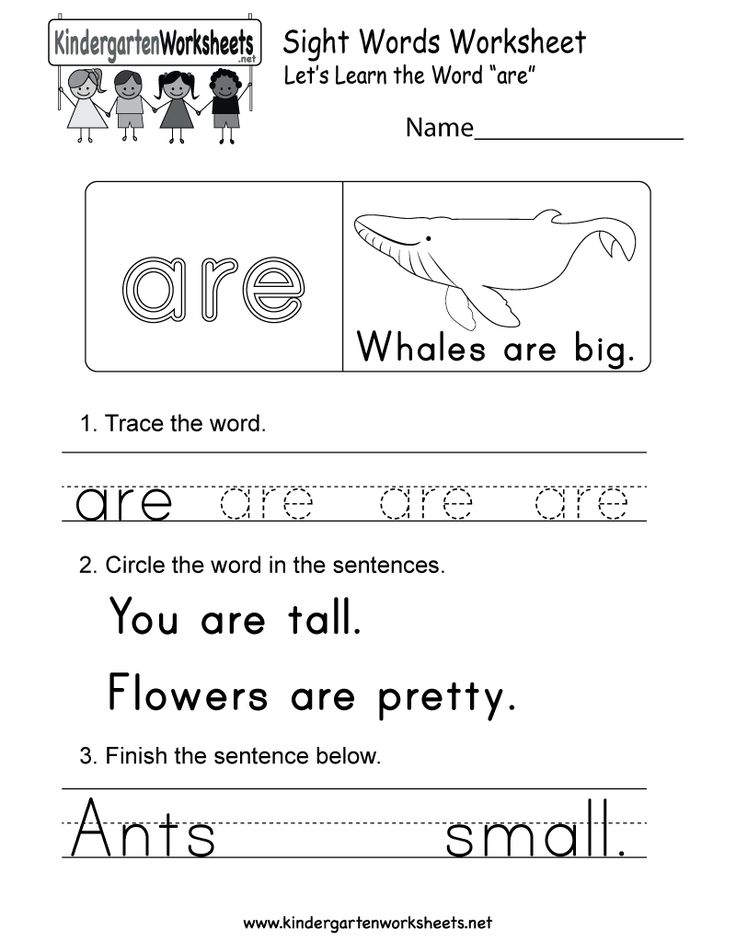

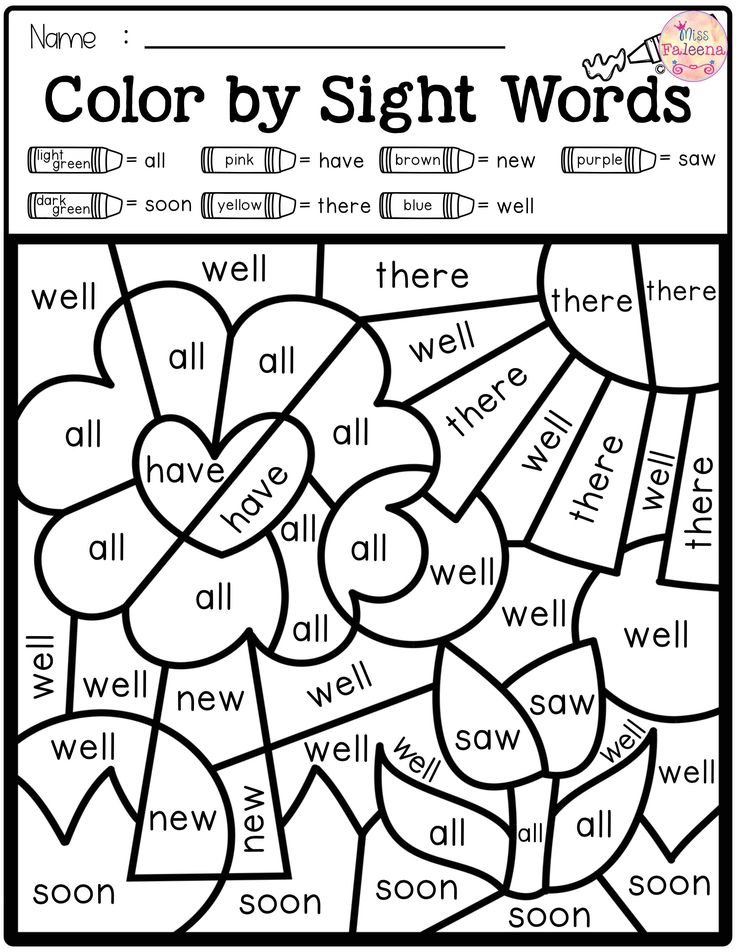

Introduce new sight words using this sequence of five teaching techniques:

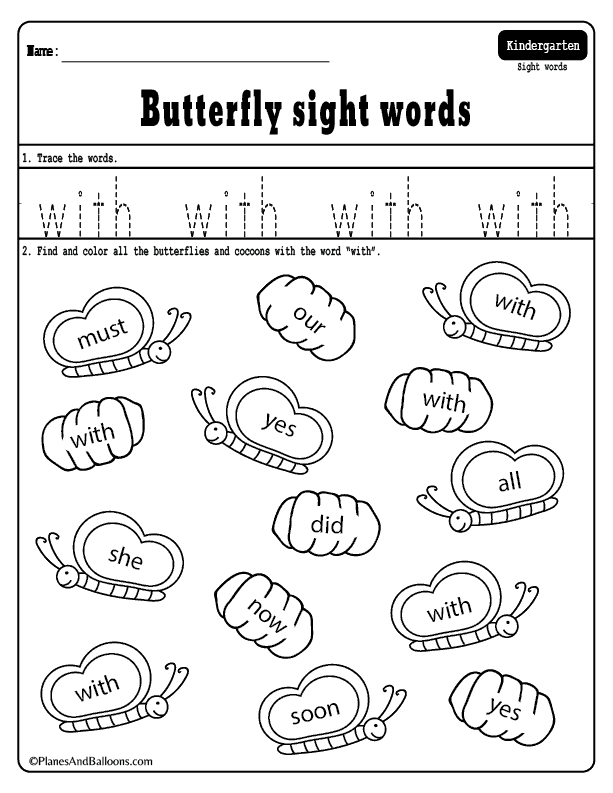

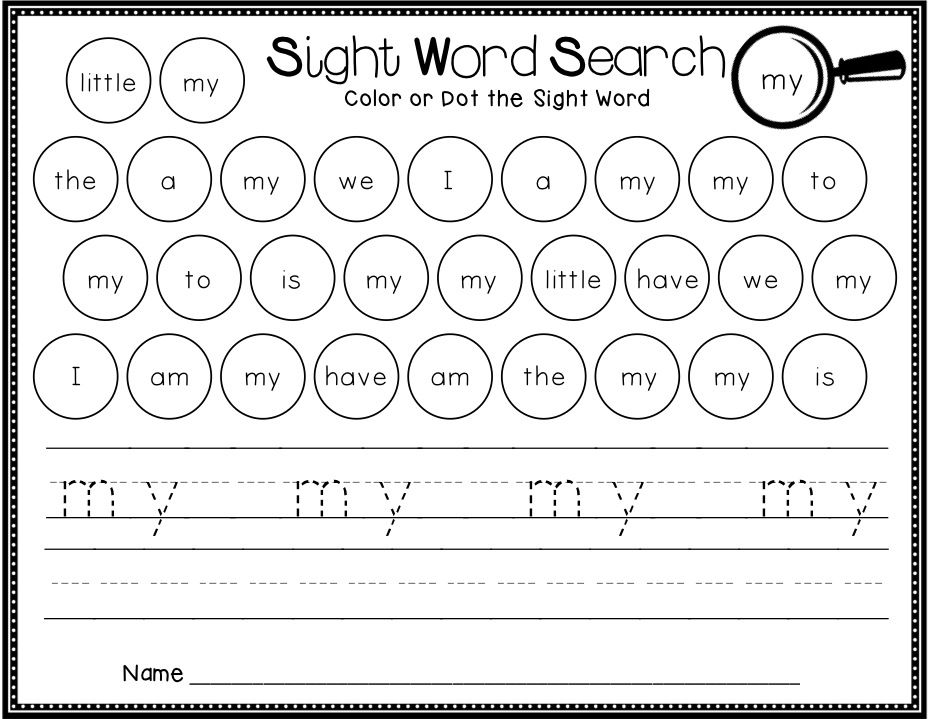

- See & Say — A child sees the word on the flash card and says the word while underlining it with her finger.

- Spell Reading — The child says the word and spells out the letters, then reads the word again.

- Arm Tapping — The child says the word and then spells out the letters while tapping them on his arm, then reads the word again.

- Air Writing — A child says the word, then writes the letters in the air in front of the flash card.

- Table Writing — A child writes the letters on a table, first looking at and then not looking at the flash card.

These techniques work together to activate different parts of the brain. The exercises combine many repetitions of the word (seeing, hearing, speaking, spelling, and writing) with physical movements that focus the child’s attention and cement each word into the child’s long-term memory.

The lessons get the child up to a baseline level of competence that is then reinforced by the games, which take them up to the level of mastery. All you need is a flash card for each of the sight words you are covering in the lesson.

↑ Top

Of course, every child will make mistakes in the process of learning sight words. They might get confused between similar-looking words or struggle to remember phonetically irregular words.

Use our Corrections Procedure every time your child makes a mistake in a sight words lesson or game. Simple and straightforward, it focuses on reinforcing the correct identification and pronunciation of the word. It can be done quickly without disrupting the flow of the activity.

Simple and straightforward, it focuses on reinforcing the correct identification and pronunciation of the word. It can be done quickly without disrupting the flow of the activity.

Do not scold the child for making a mistake or even repeat the incorrect word. Just reinforce the correct word using our script, and then move on.

↑ Top

Q: Progress is slow. We have been on the same five words for a week!

A: It is not unusual to have to repeat the same set of words several times, especially in the first weeks of sight words instruction. The child is learning how to learn the words and is developing pattern recognition approaches that will speed his progress. Give him time to grow confident with his current set of words, and avoid overwhelming the child with new words when he hasn’t yet become familiar with the old words.

Q: Do I really need to do all five techniques for every word?

A: Start out by using all five techniques with each new word. The techniques use different teaching methods and physical senses to support and reinforce the child’s memorization of the word. After a few weeks of lessons, you will have a sense for how long it takes your child to learn new words and whether all five exercises are necessary. Start by eliminating the last activity, Table Writing, but be sure to review those words at the next lesson to see if the child actually retained them without that last exercise. If the child learns fine without Table Writing, then you can try leaving out the fourth technique, Air Writing. Children who learn quickly may only need to use two or three of the techniques.

The techniques use different teaching methods and physical senses to support and reinforce the child’s memorization of the word. After a few weeks of lessons, you will have a sense for how long it takes your child to learn new words and whether all five exercises are necessary. Start by eliminating the last activity, Table Writing, but be sure to review those words at the next lesson to see if the child actually retained them without that last exercise. If the child learns fine without Table Writing, then you can try leaving out the fourth technique, Air Writing. Children who learn quickly may only need to use two or three of the techniques.

Q: How long will it take to get through a whole word list? I want my child to learn ALL the words!!!

A: That depends on a number of factors, including frequency of your lessons as well as your child’s ability to focus. But do not get obsessed with the idea of racing through the word lists to the finish line. It is much, much better for your child to solidly know just 50 words than to “kind of” know 300 words. We are building a foundation here, and we want that foundation to be made of rock, not sand!

It is much, much better for your child to solidly know just 50 words than to “kind of” know 300 words. We are building a foundation here, and we want that foundation to be made of rock, not sand!

↑ Top

Leave a Reply

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

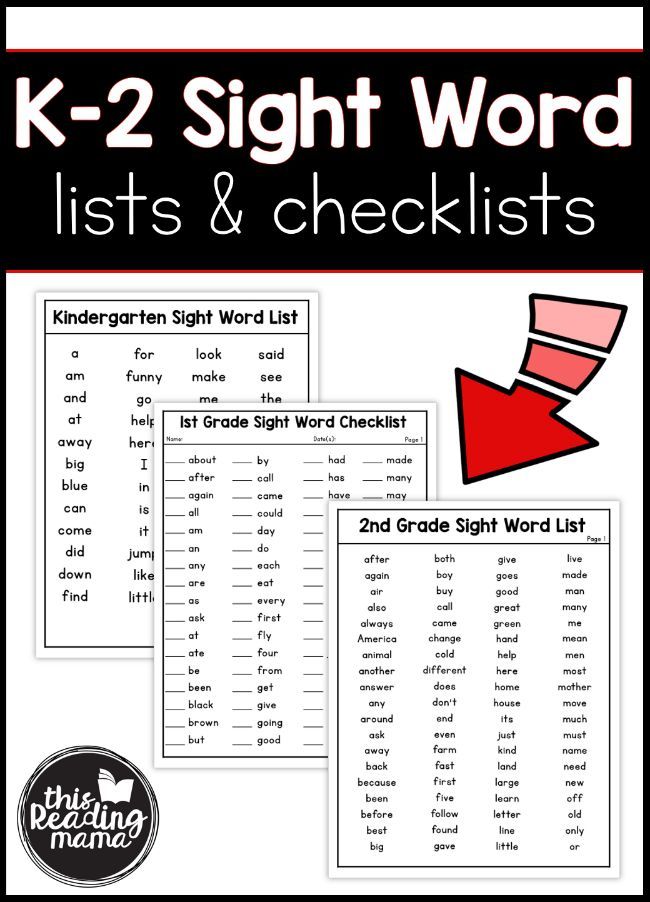

We have visited many schools to observe intervention lessons and core reading instruction. For years we have been struck that even schools embracing research-based reading instruction teach high-frequency words through rote memorization. It is as if the high-frequency words are a special set of words that need to be memorized and can’t be learned using sound–symbol relationships.

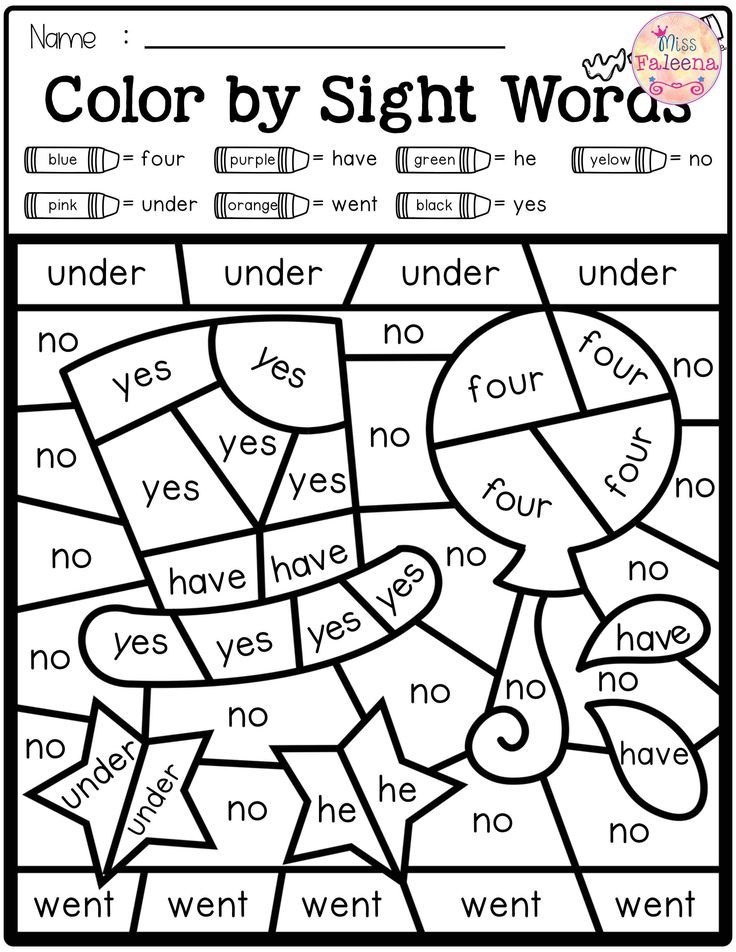

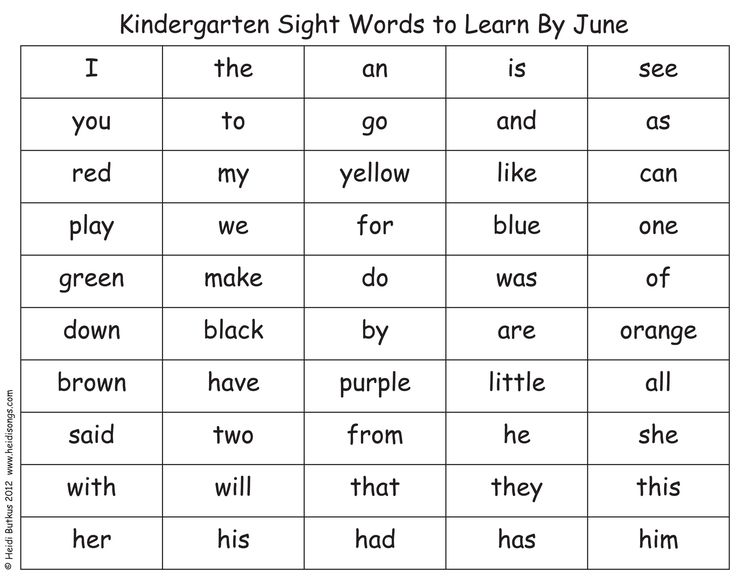

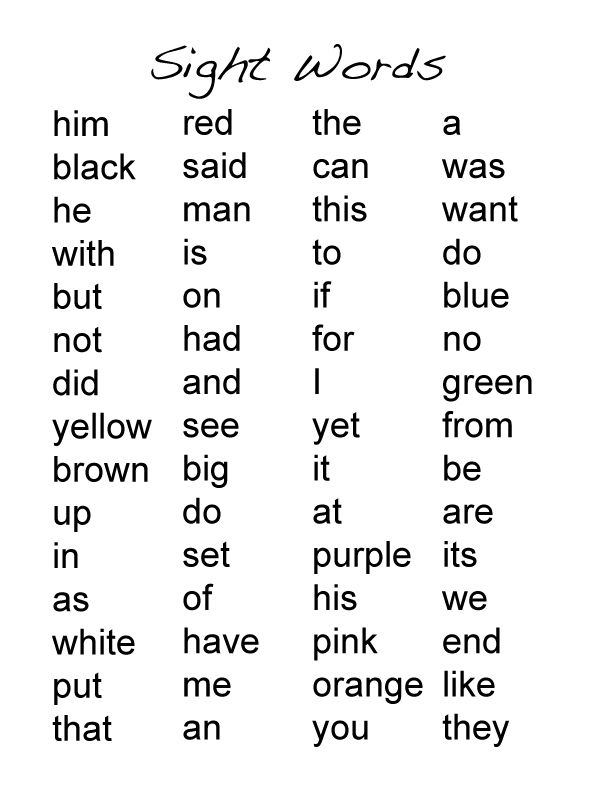

A number of years ago, a teacher we respect enormously asked for help because many of her Tier 2 students and all of her Tier 3 students in first and second grades were failing to learn high-frequency words, even though they were progressing in their phonics lessons. We observed her teaching the digraph th to a group of four Tier 3 first grade students. This lesson was in April. Her students had learned to read CVC words and this was their first lesson with digraphs. The high-frequency words the students were responsible for knowing in this lesson were the color words: blue, red, yellow, orange, purple, and green. None of the four students could spell more than two of the words accurately. All four students had difficulty reading those words when they were mixed into lists with other high-frequency words. (Indeed, they were having difficulty reading all the high-frequency words in the lists.)

We observed her teaching the digraph th to a group of four Tier 3 first grade students. This lesson was in April. Her students had learned to read CVC words and this was their first lesson with digraphs. The high-frequency words the students were responsible for knowing in this lesson were the color words: blue, red, yellow, orange, purple, and green. None of the four students could spell more than two of the words accurately. All four students had difficulty reading those words when they were mixed into lists with other high-frequency words. (Indeed, they were having difficulty reading all the high-frequency words in the lists.)

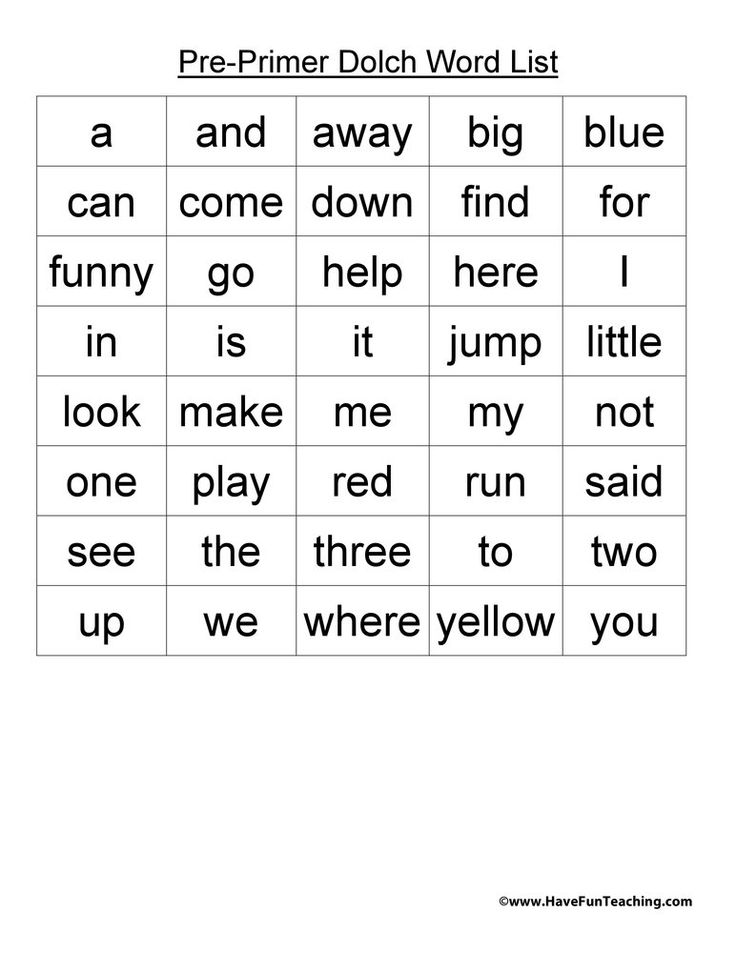

These students could read words that followed spelling patterns they had learned and practiced, but they struggled learning words that made no sense to them from a sound–spelling viewpoint. We suggested that the students learn high-frequency words according to spelling patterns, and not according to frequency number or theme.

Together with the teacher, we organized the high-frequency words to fit into the phonics lessons so that the words were tied to spelling patterns students were learning. First, we focused on identifying decodable high-frequency words such as but, him, and yes and integrating them into phonics lessons instead of teaching them as words that had to be memorized. Next, we identified irregularly spelled high-frequency words such as said, you, and from. These words have two or three letter sounds students knew and only one or two letters that had to be memorized. We integrated 2 or 3 of these words into a phonics lessons, and students learned to identify the letters spelled as expected and to learn “by heart” the letters not spelled as expected.

With this approach, students had an easier time learning to read the word said because they knew that only the letters ai are an unexpected spelling. Students also soon stopped confusing was and saw because they learned to think about the first sound before reading or spelling those words. The teacher told us that she, her students, and their parents were thrilled that they were no longer “banging their heads against the wall” going over and over the words as students tried to memorize how to read or spell high-frequency words with little success.

The teacher told us that she, her students, and their parents were thrilled that they were no longer “banging their heads against the wall” going over and over the words as students tried to memorize how to read or spell high-frequency words with little success.

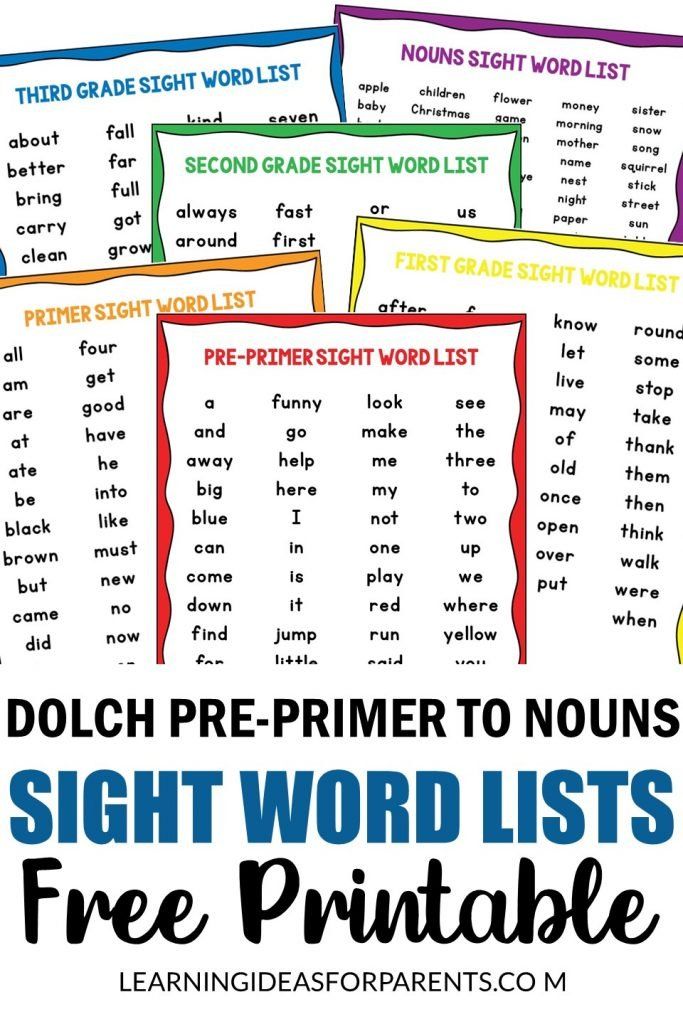

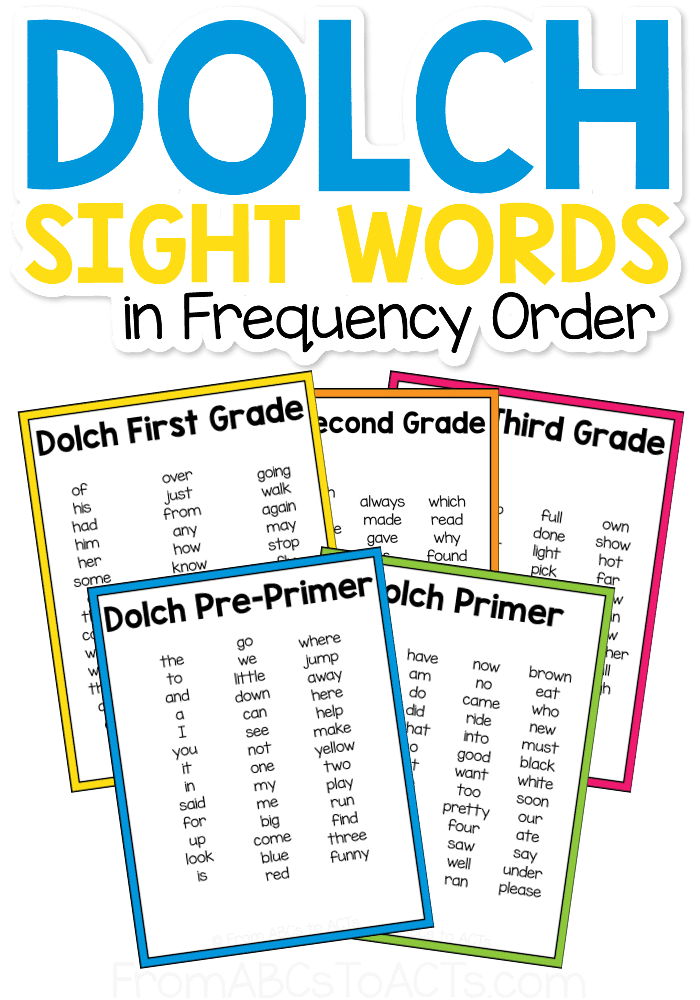

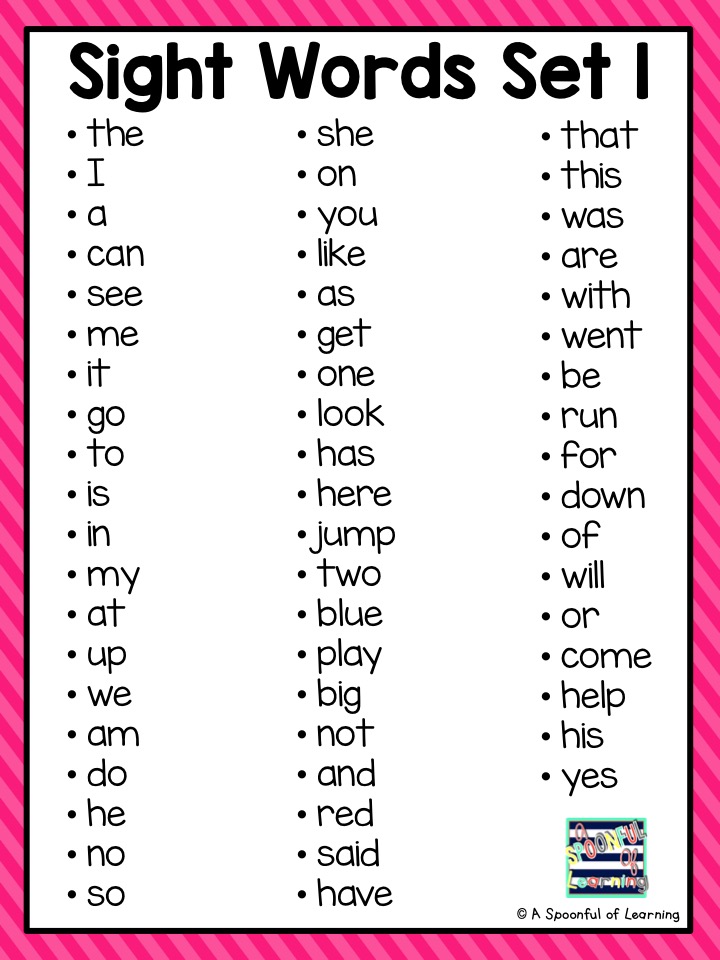

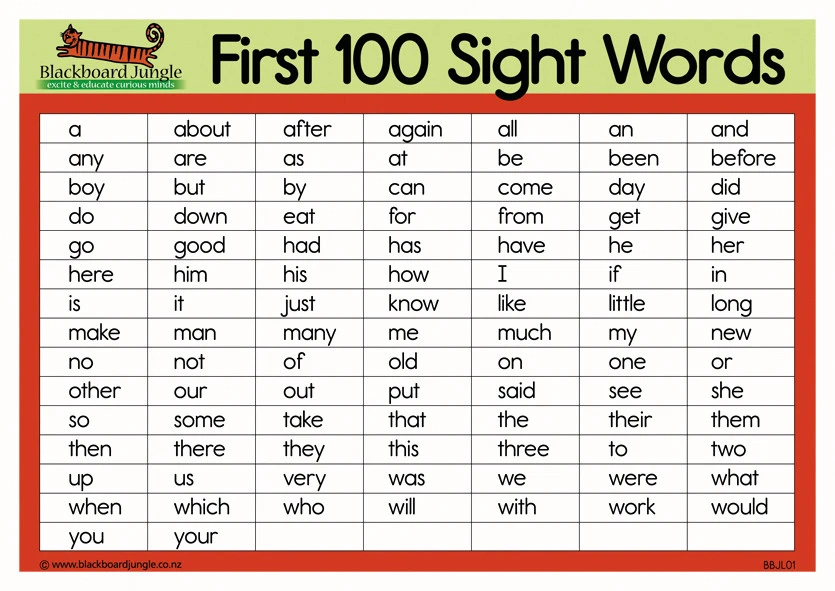

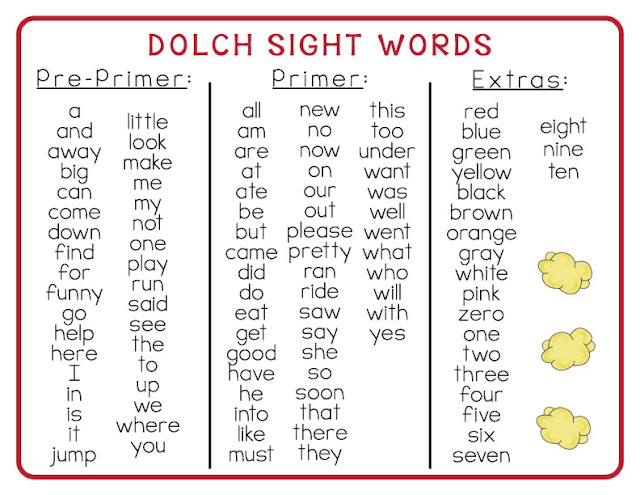

Current practices

High-frequency words are often referred to as “sight words”, a term that usually reflects the practice of learning the words through memorization. These words might be on the Dolch List, Fry Instant Words, or selected from stories in the reading program. Common practice often includes sending these “sight words” home for students to study and memorize, or drilling with flash cards in school. Students may start with word #1 and progress through the words in the order of frequency. Some teachers, like our friend above, group the words in categories, such as numbers or colors, whenever possible. In essence, high-frequency word instruction is often fully divorced from phonics instruction. While this method works for many students, it is an abysmal failure with others.

Overview of suggested restructuring

Integrating high-frequency words into phonics lessons allows students to make sense of spelling patterns for these words. To do this, high-frequency words need to be categorized according to whether they are spelled entirely regularly or not. Restructuring the way high-frequency words are taught makes reading and spelling the words more accessible to all students. The rest of this article describes how to “rethink” teaching of high-frequency words and fit them into phonics lessons.

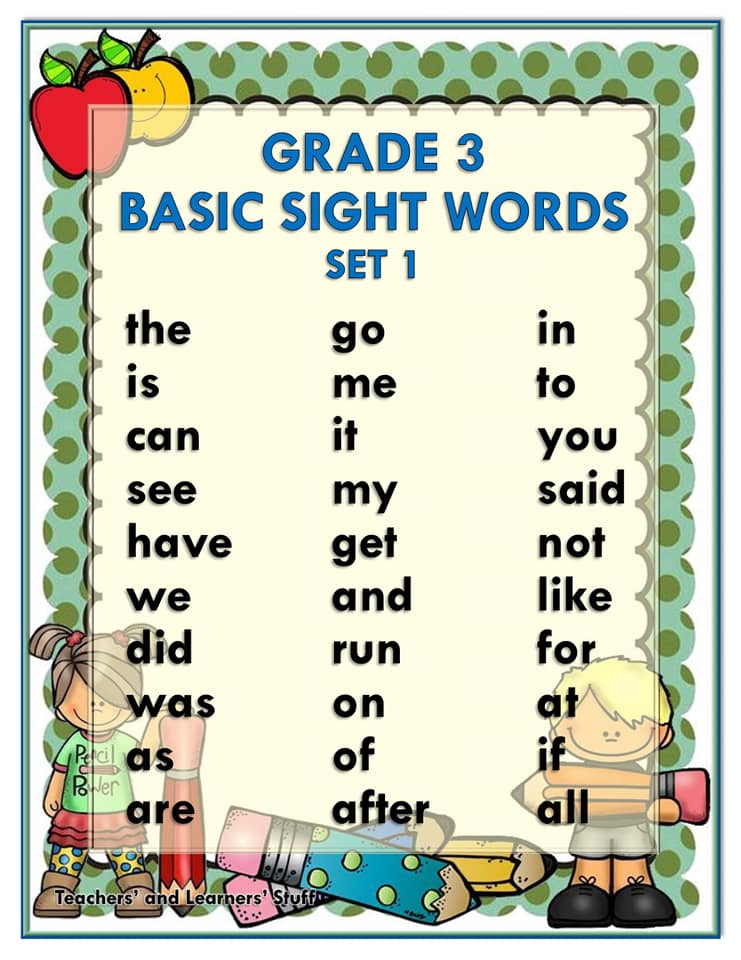

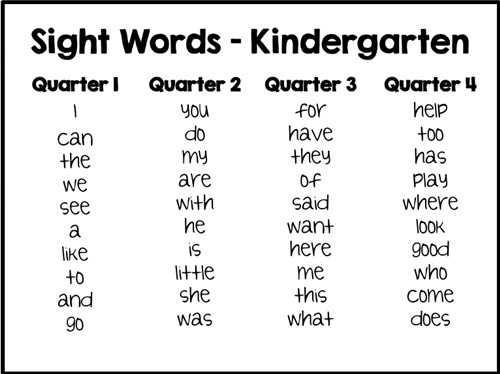

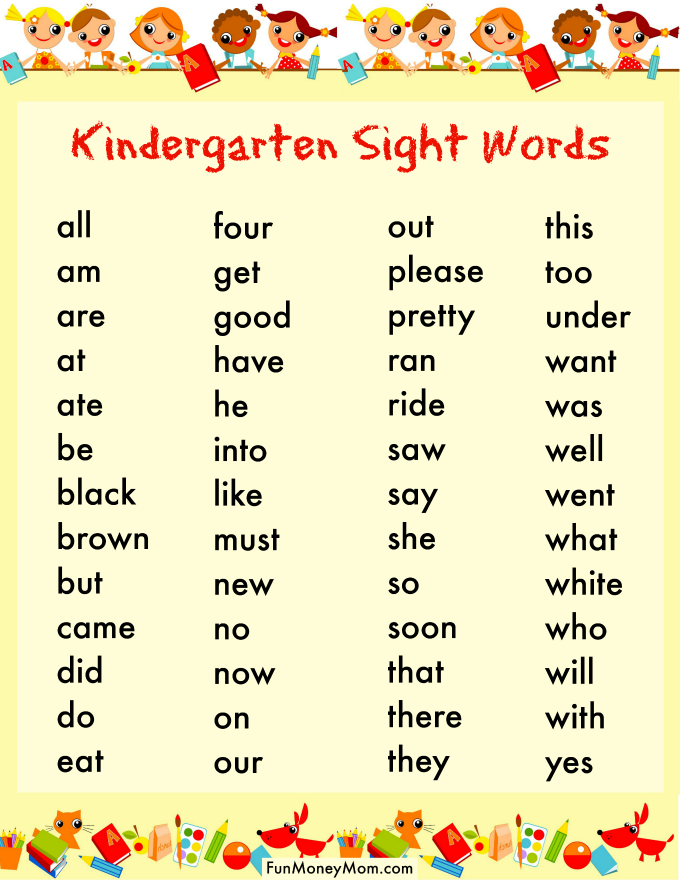

Teach 10–15 “sight words” before phonics instruction begins

Many kindergarten students are expected to learn 20 to 50, or even more, high-frequency words during the year. The words are introduced and practiced in class and students are asked to study them at home. Learning these “sight words” often starts before formal phonics instruction begins.

Children do need to know about 10–15 very-high-frequency words when they start phonics instruction. However, these words can be carefully selected so that they are the “essential words” that are not decodable when the short vowel patterns VC and CVC are taught. Words such as at, can, and had are easier for students to learn using phonics than by simply memorizing them.

However, these words can be carefully selected so that they are the “essential words” that are not decodable when the short vowel patterns VC and CVC are taught. Words such as at, can, and had are easier for students to learn using phonics than by simply memorizing them.

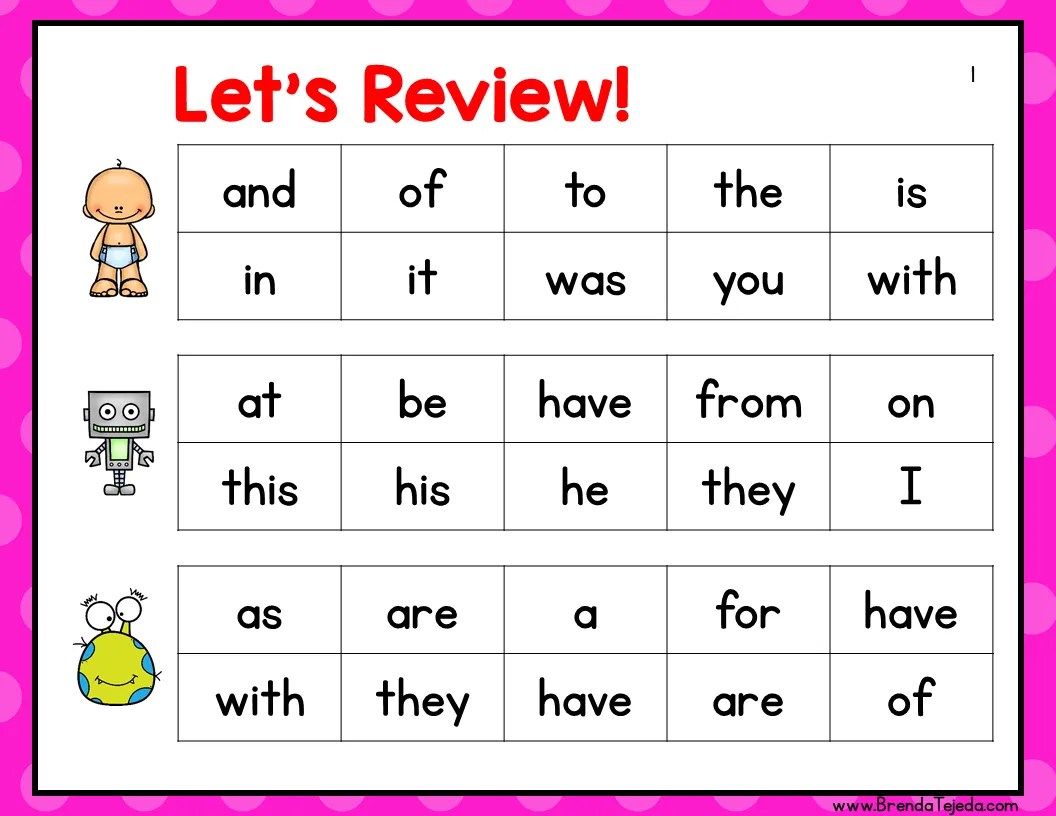

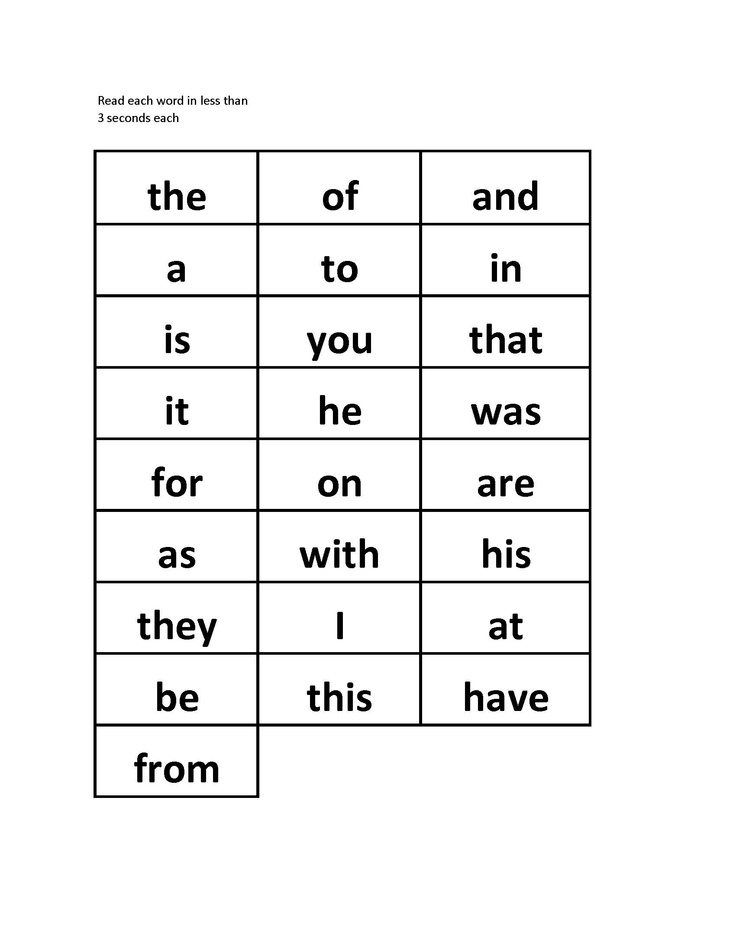

We recommend teaching 10–15 pre‐reading high-frequency words only after students know all the letter names, but before they start phonics instruction. (Students who have not learned their letter names inevitable struggle to learn words that have letters they cannot identify.) Teaching students to read the ten words in Table 1 as “sight words” even before they begin phonics instruction is unlikely to overburden even “at risk” students. These ten words can be used to write decodable sentences when phonics instruction begins. The words in Table 1 are suggestions only, and teachers may revise or add words based on their reading materials and their students. For example, the words are and said are often added.

To teach these ten pre-reading sight words, we recommend introducing one word at a time. Teaching these words in the order listed can minimize confusion for students. For example, the and a are unlikely to be confused, as are I and to. However, to and of are widely separated on the table because both are two-letter words with the letter o, and t and f have similar formations.

As we recommended above, the words in Table 1 should not be taught or practiced until a student knows all the letter names.

Students can demonstrate they know these words in a number of ways, including (1) finding the word in a list or row of other words, (2) finding the word in a text, (3) reading the word from a card, and (4) spelling the word.

If students know letter sounds and can identify the first sound in a word, the following words can be tied to beginning letter sounds because the initial sound is spelled as expected: to, and, was, you, for, is. The word I is easily recognized by students who know their letter names. On the other hand, the words the, a, and of cannot be tied to known letter sounds.

The word I is easily recognized by students who know their letter names. On the other hand, the words the, a, and of cannot be tied to known letter sounds.

Teaching a “ditty” to help students learn the, a, and of works for many students. Teachers have had success teaching students to sing the ditties below. It is important that students have the word in front of them when they say the ditty. They should point to the word when they say it in the ditty, and point to the letters when they say them in the ditty.

- The: I can say ‘thee’ or I can say ‘thuh’, but I always spell it ‘t’ ‘h’ ‘e’

- A: I can say ‘ā’ or I can say ‘uh’, but I always spell it with the letter ‘a’

- Of is hard to spell, but not for me. I love to spell of. ‘o’ ‘f’ of, ‘o’ ‘f’ of, ‘o’ ‘f’ of

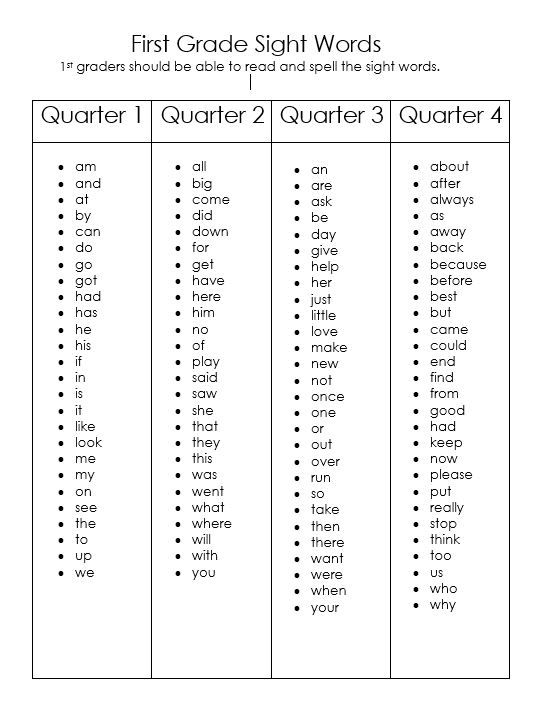

Table 1: 10 Sight Words for Pre-Readers to Learn

| Word | Dolch Frequency Rank | Fry Frequency Rank |

|---|---|---|

| the | 1 | 1 |

| a | 5 | 4 |

| I | 6 | 20 |

| to | 2 | 5 |

| and | 3 | 3 |

| was | 11 | 12 |

| for | 16 | 13 |

| you | 7 | 8 |

| is | 22 | 7 |

| of | 9 | 2 |

Dolch words are from: Dolch, E. W. (1936). A basic sight vocabulary. The Elementary School Journal, 36(6), 456-460.

W. (1936). A basic sight vocabulary. The Elementary School Journal, 36(6), 456-460.

Dolch Rankings were found on lists at K12 Reader and Mrs. Perkins Dolch Words.

Fry words and rankings are from: Fry, E., & Kress, J.K. (2006). The Reading Teacher’s Book of Lists. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco.

Flash Words and Heart Words defined

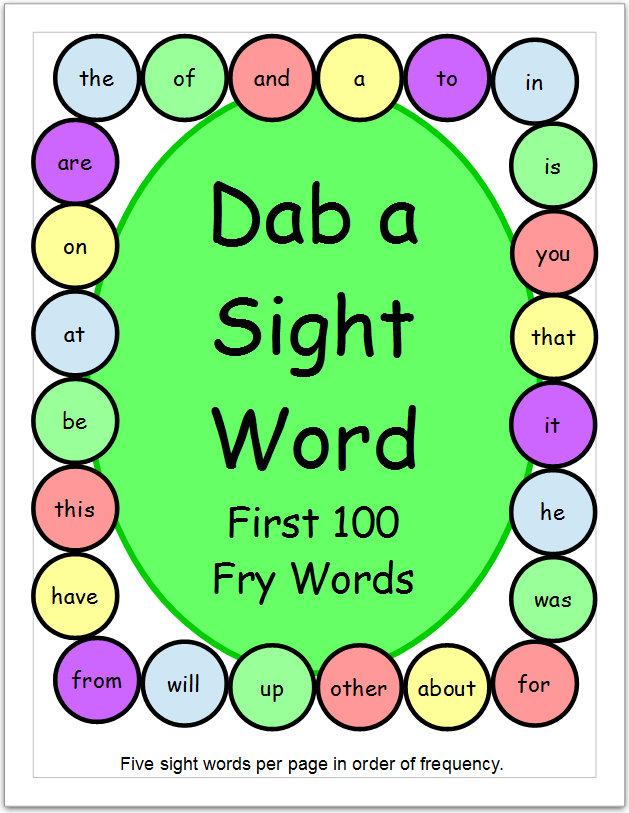

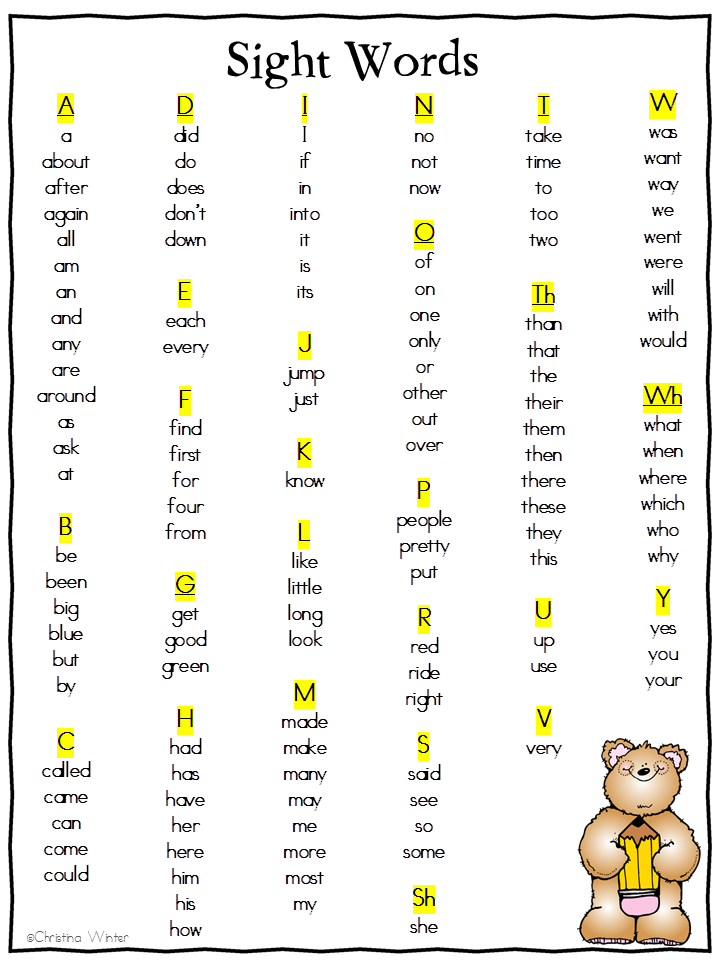

For instructional purposes, high-frequency words can be divided into two categories: those that are phonetically decodable and those with irregular spellings. We call high-frequency words that are regularly spelled and thus decodable “Flash Words”.

Although their spelling patterns are easily decoded, Flash Words are used so frequently in reading and writing that students need to be able to read and spell them “in a flash”. Examples of Flash Words at the CVC level are can, not, and did. Irregularly spelled words are called “Heart Words” because some part of the word will have to be “learned by heart. ” Heart Words are also used so frequently that they need to be read and spelled automatically. Examples of Heart Words are: said, are, and where.

” Heart Words are also used so frequently that they need to be read and spelled automatically. Examples of Heart Words are: said, are, and where.

Words on any high-frequency word list can easily be categorized into Flash Words and Heart Words. However, be cautioned that a word may change categories. For example, early in a phonics scope and sequence, see may be a Heart Word because the long e spelling patterns haven’t been taught. When students learn that ee spells long /e/, see becomes a Flash Word. Further, many of the Heart Words can be categorized into words with similar spellings. This article categorizes words on the Dolch List of 220 High-Frequency Words (Dolch 220 List)1. The method we use to categorize words on the Dolch 220 List works with any high-frequency word list.

Flash Words

One hundred and thirty-eight words (63%) on the Dolch 220 List are decodable when all regular spelling patterns are considered. Tables 2A, 2B, and 2C show the 138 decodable words categorized by spelling patterns. These tables can help teachers determine when to introduce the words during phonics lessons. Table 2A may be most useful for teachers of beginning reading because it lists the 60 one-syllable decodable words with the short vowel spelling pattern.

Tables 2A, 2B, and 2C show the 138 decodable words categorized by spelling patterns. These tables can help teachers determine when to introduce the words during phonics lessons. Table 2A may be most useful for teachers of beginning reading because it lists the 60 one-syllable decodable words with the short vowel spelling pattern.

Table 2A: Flash Words (Decodable Words)

60 One-Syllable Words with Short Vowel Spelling Patterns

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch frequency ranking)

| VC | CVC | Digraphs | Blends | Words Ending in NG and N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by digraph) | (Sorted by ending blends, then beginning blends) | (Sorted by ending letters) |

| at (21) | had (20) hot (203) | that (14) | and (3) | sing (213) |

| am (37) | can (42) but (19) | with (23) | just (78) | bring (155) |

| an (72) | ran (111) run (163) | then (38) | must (149) | long (167) |

| it (8) | him (22) cut (188) | them (52) | fast (182) | thank (216) |

| in (10) | did (45) get (51) | this (55) | best (210) | think (110) |

| if (65) | will* (59) yes (60) | much (142) | went (62) | drink (159) |

| on (17) | big (61) red (80) | pick (185) | ask (70) | |

| off* (132) | six (120) well* (109) | wish (217) | its (75) | |

| up (24) | sit (191) let (112) | when (44) | jump (98) | |

| us (169) | not (49) tell (141) | which (192) | help (113) | |

| got (93) ten (153) | stop (131) | |||

| black (151) |

*Students easily understand that two consonants at the end of a word spell one sound.

1The source for words on the Dolch 220 List is: Dolch, E. W. (1936). A basic sight vocabulary. The Elementary School Journal, 36(6), 456-460. Tables in this article show frequency rankings for words on the Dolch 220 list. Rankings for words on the Dolch 220 List can be found in many places, but we did not find a primary source that can be attributable to Dr. Dolch.

Rankings were retrieved on March 15, 2013, from K12 Reader and Mrs. Perkins Dolch Words.

Flash Words that can be taught with spellings students know will vary at any given time, depending on which phonics patterns students have been taught. For example, the words had, am, and can will be decodable when students have learned short /a/ and VC and CVC spelling patterns. That, when, pick, and much will be decodable after students learn digraphs and can read words with digraphs. The words just, went, black, and ask will be decodable when students learn to read words with blends.

Flash Words should be introduced when they fit into the phonics pattern being taught, which is different from teaching them based on their frequency of use. Flash Words are different from other decodable words only because of their frequency. They are called Flash Words because students will need lots of practice to read and spell these words “in a Flash”. These are called “Flash Words” instead of “sight words” because students do not have to memorize any part of Flash Words. They can use their knowledge of phonics patterns to read and spell the words.

Flash Words are different from other decodable words only because of their frequency. They are called Flash Words because students will need lots of practice to read and spell these words “in a Flash”. These are called “Flash Words” instead of “sight words” because students do not have to memorize any part of Flash Words. They can use their knowledge of phonics patterns to read and spell the words.

Flash Words with advanced vowels to teach with early phonics instruction

Table 2B shows 60 one-syllable words with more advanced vowel spelling patterns. A few of these are so frequent that they will need to be taught when students are still learning the short vowel spelling patterns (VC and CVC) during phonics lessons.

Table 2B: Flash Words (Decodable Words)

60 One-Syllable Words With R‐Controlled, Long, and Other Vowel Spellings

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

| r-Controlled Vowels | CV Long Vowel | VCe (silent e) | Vowel Teams with Long Vowel Sounds | Vowel Teams with Other Vowel Sounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel sound, then vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel sound, then vowel spelling) |

| for* (16) | I* (6) | came (69) | play (127) | out* (31) |

| or* (123) | he* (4) | take (94) | may (130) | round (140) |

| start (150) | she* (15) | make (114) | say* (183) | found (200) |

| far (205) | be* (33) | made (162) | see* (48) | down* (40) |

| her* (28) | we* (36) | gave (164) | green (99) | now* (66) |

| first (146) | me* (58) | ate (177) | sleep (116) | how* (88) |

| hurt (186) | go* (35) | like (53) | keep (143) | brown (117) |

| so* (47) | ride (76) | three (170) | look (26) | |

| no* (68) | five (119) | eat (125) | good (82) | |

| my* (56) | white (152) | read (197) | new (148) | |

| by* (103) | clean (208) | soon (161) | ||

| fly (138) | right (90) | draw (207) | ||

| try* (147) | light (184) | saw* (106) | ||

| why (198) | own (199) | |||

| show (202) | ||||

| grow (209) |

* Many programs teach these words as Heart Words when students are still learning to read words with short vowels.

Traditionally, many words in Table 2B would be taught as “sight words” and not included as part of phonics lessons. These words might be introduced as they are encountered in a story, or they might be taught in order. For example, he would be taught as high-frequency word #4, then she taught as high-frequency word #12, with we (#26), be (#33), and me (#58), following later.

Under the new model, words with asterisks in Table 2B are still introduced when short vowels are being taught. The difference in the new model is that these words are grouped together by vowel spelling pattern to make it easier for students to remember the words. Instead of teaching he in isolation as a word to be memorized, we teach he, be, we, me, and she together (as shown in the CV column in Table 2b) and point out that the letter e spells the long e sound. Go, no, and so can be taught together, as can my, by, and why.

Students will learn words more easily when grouped together by similar spelling than by memorizing words one at a time as whole units. If the curriculum requires a Flash Word to be taught before the vowel pattern has been introduced, teachers can refer to Table 2B to find words that can be grouped together.

Flash Words with two and three syllables

Table 2C shows 16 Flash Words with two syllables and one Flash Word with three syllables. We recommend teaching these words after students have learned to read two‐syllable words in phonics instruction. If these words must be introduced earlier, students will learn them more easily if the teacher breaks the words into syllables and shows any known letter sounds in each syllable. This way students learn to read each syllable and blend the syllables into a word, instead of having to memorize the whole word.

Table 2C: Flash Words (Decodable Words)

17 Two-Syllable Words and 1 Three-Syllable Word

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

| CVC | "A" Spells Schwa in First Syllable | Short Vowels and r-Controlled Vowels | Short Vowel and Long Vowel | All Other Two-Syllable Words | Three-Syllable Word |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seven* (134) | about* (84) | after (108) | myself (139) | little (39) | every** (96) |

| upon (211) | around* (85) | never (133) | open* (165) | over (73) | |

| away* (101) | better (172) | funny (175) | going (115) | ||

| under (196) | yellow 118) | ||||

| before (124) |

* These words have a schwa sound in the first or second syllable.

** This word is often pronounced with two syllables, especially in conversation.

Heart Words

The Dolch 220 List has 82 Heart Words (37%) that are shown on Tables 3A and 3B. Heart Words have Heart Letters, which are the irregularly spelled part of the word. For example, o is the Heart Letter in the words to and do.

Some of the Dolch Heart Words with similar spelling patterns can be grouped together, even though the spelling patterns are not regular. Table 3A (on the next page) shows 45 Heart Words grouped according to similar spelling patterns. The table also lists twelve words not on the Dolch List. These twelve words have similar spelling patterns to the Dolch words listed, and the words are likely to be words already in young students’ vocabularies. For example, could and would are Dolch words. We recommend adding should when could and would are taught, even though it is not on the Dolch 220 List.

The groups of words in Table 3A can be added to any phonics or spelling lesson, with the Heart Letters pointed out. For example, the words his, is, as, and has can all be taught as VC and CVC words in which the letter s is the Heart Letter because it spells the sound /z/.

For example, the words his, is, as, and has can all be taught as VC and CVC words in which the letter s is the Heart Letter because it spells the sound /z/.

Table 3A: Heart Words

59 Words Grouped by Similar Spelling Patterns

45 Words from the Dolch List and 14 Not on the Dolch List

(Numbers in Parentheses Are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

(Diamond [♦] indicates word is not on the Dolch List, but it fits the spelling pattern)

| Unusual Spelling Pattern | High-Frequency Words |

|---|---|

| s at the end of the word spells /z/ | his (13), is (27), as (32), has (166) |

| v is followed by e because no English word ends in v | have (34), give (144), live (206) |

| o-e spells short u /ŭ/ | some (30), come (64), done (180) |

| o spells /ōō/ (as in boot) | to (2), do (41), into (77) |

| rhyming words spelled with the same last four letters | there (29), where (95) |

| s spells /z/ in a vce word | those (179), these (212) |

| all spells /ŏll/ | all (25), call (167), fall (193), small (195), ball ♦ |

| oul spells /ŏŏ/ (as in cook) | could (43), would (57), should ♦ |

| e at the end is after a phonetic r-controlled spelling | were (50), are (63) |

| VCC and CVCC words with o spelling long o /ō/ | old (102), cold (136), hold (173), both (190) |

| CVCC words with i spelling long i /ī/ | find (167), kind (189), mind ♦ |

| words similar in meaning and spelling | one (54), once (160) |

| a after w sometimes spells short o /ŏ/ | want (86), wash (201), watch ♦ |

| ue spells /ōō/ as in boot | blue (79), glue ♦, clue ♦, true ♦ |

| u spells /ŏŏ/ (as in cook) | put (91), full (178), pull (187), push ♦ |

| rhyming words with silent l | walk (121), talk ♦ |

| rhyming words - the letter a spells short i or short e (depending on dialect) | any (83), many (218) |

| oo at the end of a word spells /ōō/ (as in boot) | too (92), boo ♦, moo ♦ |

| or spells /er/ | work (145), word ♦, world ♦ |

| uy spells long i /ī/ | buy (174), guy ♦ |

Teaching Heart Words

Table 3B shows 37 Heart Words not easily grouped by spelling patterns. Most of the words are more difficult for spelling than for reading.

Most of the words are more difficult for spelling than for reading.

As with all Heart Words, these words can also be incorporated into phonics instruction when students learn to read the regularly spelled letters a word. For example, when students know the digraph th, they and their can be introduced. The digraph th in both these Heart Words is a regular spelling for the sound /th/. The Heart Letters are ey in they and eir in their. Similarly, the Heart Letter in the word what is a, and the Heart Letter in the word from is o.

Table 3B: Heart Words

37 Words that Do Not Fit into Spelling Patterns

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

| the (1) | very (71) | here (105) | does (154) | use (181) |

| a (5) | yours (74) | two (122) | goes (156) | carry (194) |

| of (9) | from (81) | again (126) | write (157) | because (204) |

| you (7) | don’t (87) | who (128) | always (158) | together (214) |

| was (11) | know (89) | been (129) | only (168) | please (215) |

| said (12) | pretty (97) | eight (135) | our (171) | shall (219) |

| they (18) | four (100) | today (137) | warm (176) | laugh (220) |

| what (46) | their (104) |

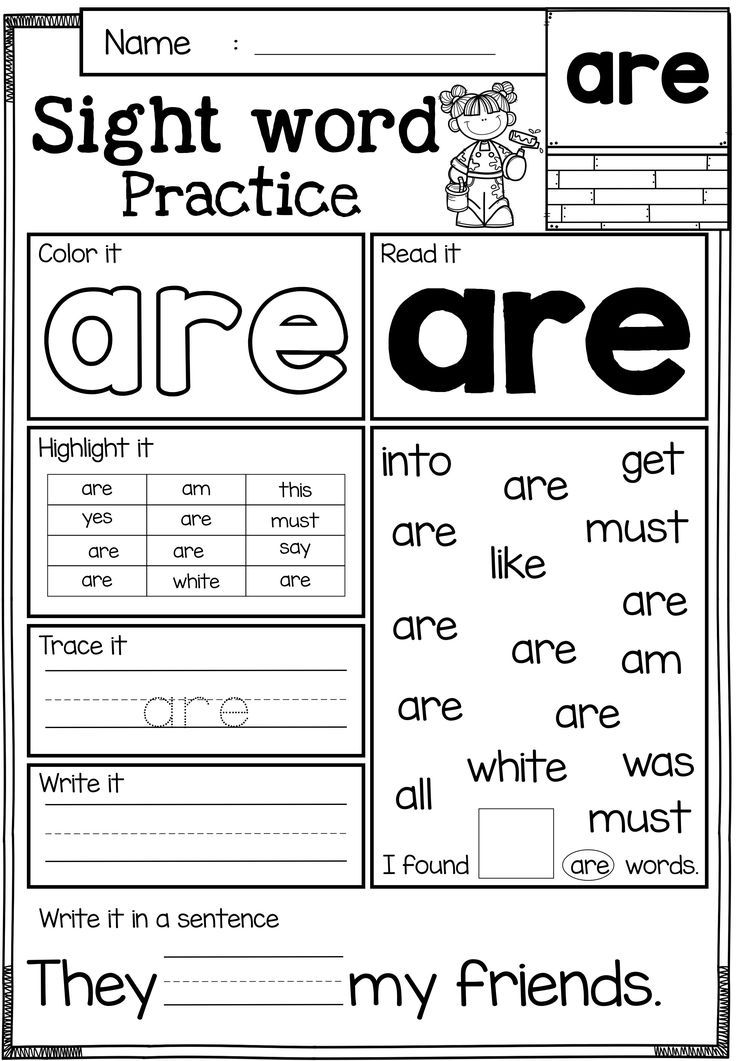

Students enjoy drawing a heart above Heart Letters, and the hearts help them remember the irregular spellings.

For example, in the word said, the hearts would go above ai because those letters are an unexpected spelling for short e (/ĕ/). A student’s practice card for the word said is shown at the right.

Implementing the new model

In order to implement the new phonics-based model for teaching high-frequency words, teachers will need to fit high-frequency words into phonics instruction. To do this, generally a committee of three or four kindergarten and first grade teachers organizes their lists of high-frequency words according to Heart Words and Flash Words by spelling patterns. Next they determine when and how high-frequency words fit into the phonics scope and sequence. These same teachers provide professional development to show other teachers how to implement the new model.

Sometimes a coordinated effort to change the way high-frequency words are taught is not an option, and teachers are able to only partially implement the suggestions in this article. These teachers continue to introduce the words as determined by their curriculum. However, they tell students whether the “sight word” is a Flash Word or a Heart Word, and they introduce the words by teaching letter–sound relationships as outlined in this article. Further, teachers introduce words with similar spelling patterns whenever possible. For example, if only the word would is scheduled to be introduced, they also teach could and should, which fit the spelling pattern. Finally, these teachers do not hold students accountable for high-frequency words that are beyond the spelling patterns that have been taught in phonics lessons.

These teachers continue to introduce the words as determined by their curriculum. However, they tell students whether the “sight word” is a Flash Word or a Heart Word, and they introduce the words by teaching letter–sound relationships as outlined in this article. Further, teachers introduce words with similar spelling patterns whenever possible. For example, if only the word would is scheduled to be introduced, they also teach could and should, which fit the spelling pattern. Finally, these teachers do not hold students accountable for high-frequency words that are beyond the spelling patterns that have been taught in phonics lessons.

The new model allows a different approach for working with students who have difficulty learning high-frequency words. For example, students working on short vowel patterns may confuse her and here, which are often introduced early as part of the “sight word” list. A teacher who recognizes the source of this confusion would not expect students to continue trying to memorize the two words. Instead, the teacher would include her as part of instruction on r-controlled vowels and include here when silent e is taught. Students will be less likely to misread or misspell these words when they understand the relation of the spelling er to the sound /er/ and the spelling ere to the sound /ēr/.

Instead, the teacher would include her as part of instruction on r-controlled vowels and include here when silent e is taught. Students will be less likely to misread or misspell these words when they understand the relation of the spelling er to the sound /er/ and the spelling ere to the sound /ēr/.

Traditionally, students would have continued struggling with and failing to memorize these easily confused words. With the new model, those students are not held accountable for accurately reading and spelling the words until they can understand and use the sound–spelling correspondences. All teachers using this approach say that students learn to spell and read the words much more easily than with the traditional approach.

About the authors

Linda Farrell and Michael Hunter are founding partners of Readsters, LLC. They provide professional development and write curriculum to support excellent reading instruction to students of all ages. Their favorite work is in the classroom where they can model effective reading instruction and coach teachers. Their most unusual work so far has been helping develop early reading instruction for children in Africa who are learning to read in 12 different mother tongue languages that Linda and Michael don’t even speak.

Their favorite work is in the classroom where they can model effective reading instruction and coach teachers. Their most unusual work so far has been helping develop early reading instruction for children in Africa who are learning to read in 12 different mother tongue languages that Linda and Michael don’t even speak.

Tina Osenga was a founding partner at Readsters, and she is now retired.

Vision as it is

In the simplest sense, vision is primarily two eyes that receive and process information about the world around us. In fact, human vision, of course, is much more complicated, and information from the sense organs (that is, the eyes) goes through several stages of processing: both by the eye itself and then by the brain. Together with the 3Z Ophthalmological Clinic, we tell how the human visual system forms an image of reality, and explain why we do not see the world upside down, small, shaking and divided into two parts.

From your school physics course, you may remember lenses - devices made of a transparent material with a refractive surface, which, depending on their shape, can collect or scatter the light falling on them. We owe it to lenses that there are cameras, video cameras, telescopes, binoculars and, of course, contact lenses and glasses that people wear in the world. The human eye is exactly the same lens, or rather, a complex optical system consisting of several biological lenses.

The first of these is the cornea, the outer shell of the eye, the most convex part of it. The cornea is a concave-convex lens that receives rays from every point on an object and transmits them further through the moisture-filled anterior chamber and pupil to the lens. The lens, in turn, is a biconvex lens, shaped like an almond or an oblate sphere.

Biconvex lens - converging: the rays passing through its surface are collected behind it at one point, after which a copy of the observed object is formed. An interesting point is that the image of an object formed at the back focus of such a lens is real (that is, it corresponds to the same observed object), inverted and reduced. The image that forms behind the lens is therefore exactly the same.

An interesting point is that the image of an object formed at the back focus of such a lens is real (that is, it corresponds to the same observed object), inverted and reduced. The image that forms behind the lens is therefore exactly the same.

The fact that the image is reduced allows the eye to see objects that are several tens, hundreds and thousands of times larger than it. In other words, the lens compactly folds the image and in the same form gives it to the retina, which lines most of the inner surface of the eye - the place of the back focus of the lens. Together, the cornea and lens are thus a component of the visual system that collects the scattered rays emanating from an object into one point and forms their projection on the retina. Strictly speaking, there is actually no “picture” on the retina: these are just traces of photons, which are then converted by the receptors and neurons of the retina into an electrical signal.

This electrical signal then travels to the brain where it is processed by the visual cortex. Together, these departments are responsible for converting signals about the location of photons - the only information that the eye itself receives - into meaningful images. At the same time, the brain is an interconnected system, and not only our eyes and visual system, but also other sensory organs that can receive information are responsible for how we perceive what is happening in reality. We do not see the world upside down due to the fact that our vestibular apparatus has information that we are standing straight, with two feet on the ground, and a tree growing from the ground, accordingly, should not be upside down.

Confirmation of this is an experiment that American psychologist George Stratton set up on himself in 1896: the scientist invented a special device - an invertoscope, whose lenses can also flip the image that the one who wears them looks at. In his device, Stratton walked for a week and at the same time did not go crazy from having to move in an inverted space. His visual system quickly adapted to the changed circumstances, and after a couple of days the scientist saw the world the way he used to see it since childhood.

His visual system quickly adapted to the changed circumstances, and after a couple of days the scientist saw the world the way he used to see it since childhood.

In other words, there is no special section in the brain that flips the image received on the retina: the entire visual system of the brain is responsible for this, which, taking into account information from other senses, allows us to accurately determine the orientation of objects in space.

3Z Clinics

As for the retina itself, in order to understand how vision works, you also need to take a closer look at its functioning and structure. The retina is a thin multilayer structure that contains neurons that receive and process light signals from the optical eye systems and send them to each other and to the brain for further processing. In total, three layers of neurons are distinguished in the retina and two more layers of synapses that receive and transmit signals from these neurons.

The first and main neurons involved in the processing of light stimuli are photoreceptors (light-sensitive sensory neurons). The two main types of photoreceptors in the retina are rods and cones, named for their rod and cone shape, respectively. Rods and cones are filled with light-sensitive pigments - rhodopsin and iodopsin, respectively. Rhodopsin is many times more sensitive to light than iodopsin, but only to light with one wavelength (about 500 nanometers in the visible region) - this is why rods containing rhodopsin are responsible for human vision in the dark: they catch even the smallest rays, helping us to distinguish the outlines of objects, while not allowing you to accurately determine their color. But the "daytime" photoreceptors - cones - are already responsible for color perception.

The two main types of photoreceptors in the retina are rods and cones, named for their rod and cone shape, respectively. Rods and cones are filled with light-sensitive pigments - rhodopsin and iodopsin, respectively. Rhodopsin is many times more sensitive to light than iodopsin, but only to light with one wavelength (about 500 nanometers in the visible region) - this is why rods containing rhodopsin are responsible for human vision in the dark: they catch even the smallest rays, helping us to distinguish the outlines of objects, while not allowing you to accurately determine their color. But the "daytime" photoreceptors - cones - are already responsible for color perception.

Light-sensitive iodopsin, which is part of cones, is of three types, depending on the wavelength of light it is sensitive to. In the normal state, the cones of the human eye respond to light with long, medium and short wavelengths, which roughly corresponds to red-yellow, yellow-green and blue-violet colors (or, more simply, red, green and blue). There are different numbers of cones that contain one or another type of iodopsin in the retina, and their balance helps to distinguish all the colors of the surrounding world. In the case when cones with one or another type of iodopsin are not enough or simply not present, they speak of the presence of color blindness - a feature of vision in which recognition of all or some colors is not available. The type of color blindness directly depends on which cones “do not work”, but deuteranopia is considered the most common in a person - with it there are no cones whose iodopsin is sensitive to medium wavelength light (that is, they perceive green color poorly or do not perceive it at all) .

There are different numbers of cones that contain one or another type of iodopsin in the retina, and their balance helps to distinguish all the colors of the surrounding world. In the case when cones with one or another type of iodopsin are not enough or simply not present, they speak of the presence of color blindness - a feature of vision in which recognition of all or some colors is not available. The type of color blindness directly depends on which cones “do not work”, but deuteranopia is considered the most common in a person - with it there are no cones whose iodopsin is sensitive to medium wavelength light (that is, they perceive green color poorly or do not perceive it at all) .

In this case, rods and cones do not cover the entire corresponding layer of the retinal surface: it contains the so-called blind spot, which does not contain photosensitive receptors at all. Since there are none, there is nothing to process the light within the borders of the spot - that is why those objects that fall into the "field of view" of the blind spot are invisible to humans. The vision of any person (fortunately or unfortunately) does not allow you to see these blind spots, but some diseases lead to the appearance of a scotoma (that is, a blind area in the visual field) and outside the corresponding place on the retina.

The vision of any person (fortunately or unfortunately) does not allow you to see these blind spots, but some diseases lead to the appearance of a scotoma (that is, a blind area in the visual field) and outside the corresponding place on the retina.

The signal received and processed by photoreceptors then passes to another layer of neurons - bipolar cells. Such cells are a kind of intermediaries that connect cones and rods with ganglion cells - retinal neurons that generate nerve impulses and then transmit them along the optic nerve to the visual cortex of the brain through the lateral geniculate body (a small tubercle on the surface of the thalamus).

The lateral geniculate body, having received signals from retinal ganglion cells, first transmits them to the primary visual cortex, the most evolutionarily ancient part of the visual system of the brain (also called V1 for convenience and brevity). At this point, the formation of an actual image of what is happening around us begins - the photons received by the eye begin to take shape, and the color, shape, presence of movement and other aspects of the image turn into electrical activity. Depending on what these signals convey (the movement of an object in space or its shape), they are then sent for processing along the ventral and dorsal pathways to other parts of the visual cortex. For example, the middle temporal visual area (its serial number is five, that is, it is briefly called V5) is considered part of the dorsal pathway, as it is responsible for motion processing, and the fourth zone (V4) is responsible for color processing, therefore it belongs to the ventral pathway.

Depending on what these signals convey (the movement of an object in space or its shape), they are then sent for processing along the ventral and dorsal pathways to other parts of the visual cortex. For example, the middle temporal visual area (its serial number is five, that is, it is briefly called V5) is considered part of the dorsal pathway, as it is responsible for motion processing, and the fourth zone (V4) is responsible for color processing, therefore it belongs to the ventral pathway.

Modern technologies help to solve vision problems. For the correction of myopia, hyperopia and astigmatism, 3Z clinics have collected 6 of the world's best vision correction practices: ReLEx SMILE, ReLEx FLEx, Femto Super LASIK, Super LASIK, PRK and implantation of phakic intraocular lenses. The technology is selected individually for each patient to ensure the best result. Therefore, visual acuity after surgery is often 120% or even 150%.

The departments responsible for processing information from the sense organs and, as we have already found out, helping to recreate a picture of the real world to the visual system, are not the only parts of the brain that are involved in the process of vision. The motor cortex, which is responsible for processing movements, also plays an important role. The motor cortex is important because the eyes are constantly moving: shifting your gaze helps you follow a moving image or see something that is not entirely in the field of view.

The motor cortex, which is responsible for processing movements, also plays an important role. The motor cortex is important because the eyes are constantly moving: shifting your gaze helps you follow a moving image or see something that is not entirely in the field of view.

In a calm state (when we look at a static object or even at the background), the eyes still move, making very fast synchronous movements (up to 80 milliseconds) - saccades. Information that the eye needs to change position is sent to it from the motor cortex. A little earlier, exactly the same (or at least similar) signal is sent to the visual cortex as a so-called "efferent copy". This gives the visual cortex information that the eye will move before the movement even starts, which helps the visual cortex to ignore possible small movements.

Finally, it remains to deal with one more point - why the picture of reality that we see is not divided into two parts. Humans, like other vertebrates, have one pair of eyes. They are located quite close to each other: the holes in the eye sockets of the skull provide the location of the eyes in such a way that each of the eyes, on the one hand, has its own field of view (about 90 degrees for each eye - that is, a little more than 180 in total), and on the other - 60 degrees of the central field of view, which intersect with each eye. Due to this intersection, the images received by one and the other eye are combined into one image in the center of the common field of view. The same intersection of visual fields provides us with stereoscopic (or binocular) vision and the ability to perceive depth. Binocularity of vision is lost in some forms of strabismus - and with them the normal ability to perceive depth is also lost.

They are located quite close to each other: the holes in the eye sockets of the skull provide the location of the eyes in such a way that each of the eyes, on the one hand, has its own field of view (about 90 degrees for each eye - that is, a little more than 180 in total), and on the other - 60 degrees of the central field of view, which intersect with each eye. Due to this intersection, the images received by one and the other eye are combined into one image in the center of the common field of view. The same intersection of visual fields provides us with stereoscopic (or binocular) vision and the ability to perceive depth. Binocularity of vision is lost in some forms of strabismus - and with them the normal ability to perceive depth is also lost.

Therefore, the mechanism of how the image of reality is formed in our brain is not only optics and chemical reactions occurring on the retina. The most important role in creating this picture is played by our brain - and not only the visual cortex, which makes the figures voluminous, separates them from the background and paints them in the right colors, but also other departments that are responsible for vital functions.

The 3Z clinic treats all types of visual impairments due to an irregular shape of the eye (nearsightedness and farsightedness) or excessive curvature of the cornea (astigmatism). Until July 15, vision correction in 3Z can be done in installments without an advance payment and overpayments. The promotion is valid for all types of laser vision correction, as well as for the implantation of phakic intraocular lenses (PIOL).

Elizaveta Ivtushok

Theme of vision in Russian and English

In this article we will tell you:

- The word eye meant "round stone", "amber"

- English eye - "eye" and "part of the face around the eye"

- The word vision meant "radiance", "glow"

- English vision - "vision", "vision", "imagination"

- The word lens comes from "lentil"

- English lens - “lens”, “lens”, “lentil”

- Mom, have you noticed that the lens looks like lentils?

Max, the eldest son of Lucy and Sasha, loves to surprise his parents with unexpected observations. But this question, in the silence of a Saturday morning, was especially difficult.

But this question, in the silence of a Saturday morning, was especially difficult.

“Um, no… Should I have?”

- Certainly! "Lens" in Latin means "lentil". They have the same shape, hence the name. I read it in the dictionary yesterday. And "eye" means "round pebble", can you imagine?

- It's really interesting! I didn't know you were interested in linguistics.

“Wait, that's not all. I also read about English. Here, listen!

The word eye meant "round stone", "amber"

In the Old Slavic language, the word "eye" meant "round pebble", "ball", "bead". Many linguists note the similarity of this concept with the Polish "głaz" - "boulder", "cobblestone", "piece of rock". In Old Germanic, the similar word "glas" was used to mean "amber".

Interestingly, until the 16th century, the organ of vision was called exclusively by the word "eye". According to some linguists, the displacement of this word began thanks to the colloquial phrase "roll out your eyes", that is, "look intently or in surprise."

According to some linguists, the displacement of this word began thanks to the colloquial phrase "roll out your eyes", that is, "look intently or in surprise."

The word “eye” has many ancient “relatives” that we don’t even know about: “head”, “nodule”, “iron”. They also came from words denoting different types of pebbles and shards.

In Russian there are many proverbs and sayings with the word "eye". Each of them has its own unique story. For example, the phrase "splurge" originated in the era of fisticuffs, when fighters used sandbags to temporarily disarm their opponents. This technique was banned by special decree in 1726. The phrase "splurge" has remained in the language in the sense of "to exaggerate the possibilities."

English eye

The Old English word ēage ("eye") is of Germanic origin. It has many "relatives" in other European languages - Swedish öga, Danish øie, Dutch oog. In its modern format, the word eye came into English after 1200. Interestingly, they denoted not only the organ of vision, but also the part of the face around the eyes, along with eyelashes, eyelids and eyebrows.

Interestingly, they denoted not only the organ of vision, but also the part of the face around the eyes, along with eyelashes, eyelids and eyebrows.

After the 14th century, the English word eye began to take on new meanings. Many of them still exist. So, eye is also “a buttonhole”, “a drawing in the form of an eye on a peacock feather”, “an apple on a horse's skin”, “needle eye” and “the center of a tropical cyclone”.

The English word "eye" has many interesting related words that have no analogues in Russian. For example, eye-opener (literally "eye opener") - "a sip of alcohol" or "amazing news", bulls-eye (literally "bull's eye") - "direct hit", eye-service (literally "eye service") - "work for the public" or "work under duress."

In English, as in Russian, there are a lot of catch phrases with the word "eye". So, the phrase Turn a blind eye (literally "turn a blind eye") is used in the meaning of "consciously ignore unwanted information." Linguists believe that Admiral Horatio Nelson became the creator of this phrase: during the naval battle of Copenhagen in 1801, he did not want to see his commander’s signals about the retreat and “looked” through the telescope with his absent eye.

The word vision meant "radiance", "glow"

This word comes from the Old Slavonic ZVRETI - “shine”, “shine”, “see”. Its closest “relatives” are the Serbian “behold” (“to see”), the Slovenian zreti (“to look”) and the Lithuanian žėrėti (“to shine”). The derivatives of this word are also associated with the ideas of light and radiance, for example: "dawn", "glow", "lightning", "illumination".

The immediate relatives of the word “sight” are “shame”, “sagacity” (the ability to see ahead), “mirror” (i.e., an object that is looked into), “ghost”, “guard”, etc. In modern language they are not are considered to be of the same root, but the semantic connection is obvious even now.

The origin of the word "pupil" is interesting. In Latin, there are the words pūpa (“little man”, “doll”, etc.) and pupilla, a derivative of it, “pupil”. The meaning was formed on the idea that a person looking into the eyes of the interlocutor sees his own small reflection in them. The ancient Slavs used this analogy: the word ZHRAK ("image", "vision") in the "pupil" - "little man in the eye."

The ancient Slavs used this analogy: the word ZHRAK ("image", "vision") in the "pupil" - "little man in the eye."

English vision - "vision", "vision", "imagination"

Linguists trace a direct connection between the Latin videre ("to see") and modern English vision. It is interesting that the original meaning of this word did not come down to the ability to perceive the world through the organs of vision, but to the imagination and the ability to see something supernatural. A similar trend was traced in Old French: vision - “presence”, “vision”, “unearthly appearance”.

In the meaning of “vision”, this word was fixed only at the end of the 15th century. In modern English, it has acquired additional semantic shades. For example, it is used when talking about insight, imagination, worldview, or the ability to see perspective.

The word vision, like the Russian “vision”, has several unexpected “relatives”. One of them is the popular English interjection voila (“voila”, borrowed from French), which can be translated as “here”. The same family includes visionary (“dreamer”, “seer”), evident (“obvious”) and vivid (“bright”, “alive”). French has visionnage (“view”) and visionneuse (“projector”), while German has Visionär (“seer”), Visionen (“plans”) and Visionsradius (“line of sight”).

The same family includes visionary (“dreamer”, “seer”), evident (“obvious”) and vivid (“bright”, “alive”). French has visionnage (“view”) and visionneuse (“projector”), while German has Visionär (“seer”), Visionen (“plans”) and Visionsradius (“line of sight”).

The English set expression range of vision is similar to the Russian "field of vision". Another interesting phrase twenty-twenty vision ("vision 20 to 20") means excellent vision, by analogy with the Russian "unit for both eyes." To denote a narrow outlook and limited views, the British and Americans use the expression tunnel vision - “tunnel vision”.

The word lens comes from "lentil"

The original source of this word is the Latin lens - "lentils". The shape of the lens resembles a legume, and it is this analogy that formed the basis of the word. In Russian, the concept of “linga” (“lens”) appeared in the 16th century, but it “got” to dictionaries relatively late - in the 19th century.03 year.

It is interesting that the analogy between an optical product and a plant of the legume family exists not only in Slavic, but also in other European languages: in French "

lentille ("lens" and "lentils"), in Spanish lente ("lens") and lenteja ("lentils"), in Italian lente ("lens") and lenticchia ("lentils").