Simple reading stories

Learn to Read English with Novels & Stories

Learning Languages

Lizzie Cooper-Smith

24 November, 2020

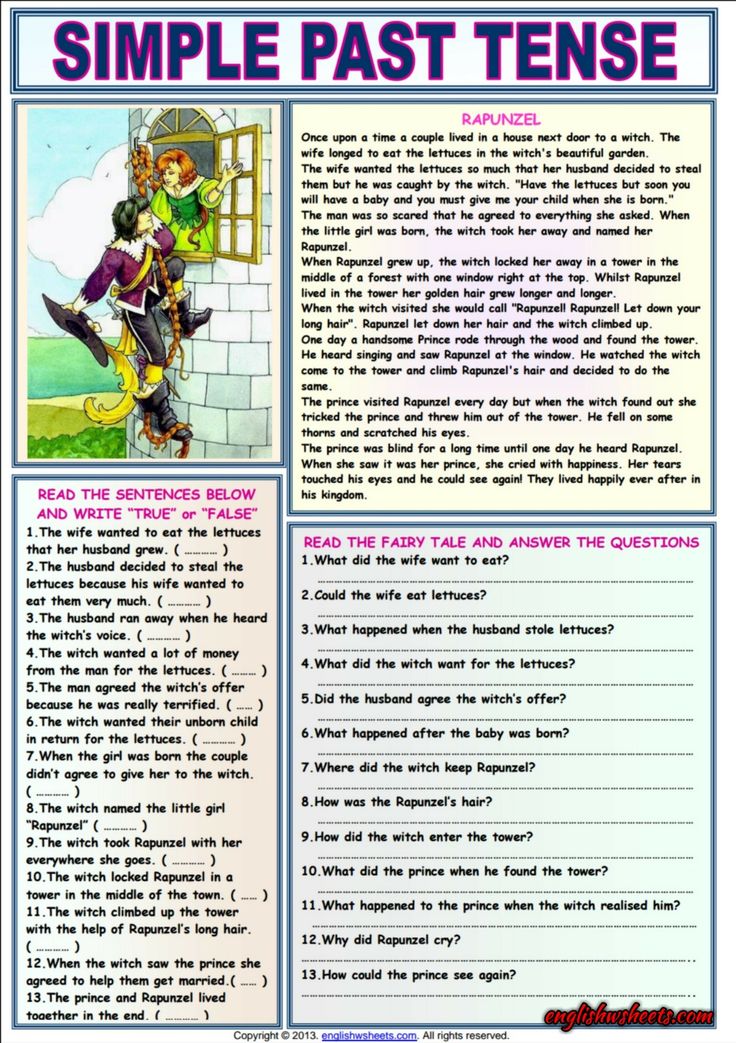

Reading classic books and novels is a fun, highly effective way of studying English language and culture. However, the prospect of diving into Great Expectations or Huckleberry Finn can be intimidating for beginners; there's just so many words you haven't learned yet! That's why many students like to start with simple stories that are easy to read like fairy tales, children's stories, and traditional texts. Many beginners choose easy novels and stories as an introduction to reading in English because it helps train them to eventually move on to more challenging texts. We've picked the best 6 to help you get started.

1. Danny the Champion of the World by Roald Dahl

Difficulty: Easy

Roald Dahl is one of the greatest writers of all time for both children and adults alike. His simple writing style and charming, beautiful stories are world famous. However, some of his stories can be prone to 'nonsense' words and old language. Danny the Champion of the World doesn't have this problem - it's a more adult story about a boy's relationship with his father - and his father's dark, secret past.

2. Charlotte's Web by E.B. White

Difficulty: Medium

This famous tale was written by a writer well known for his clean, simple writing style. He was so good that he even wrote an entire instruction manual about how to write clearly! Charlotte's Web is a story set on a farm about an unlikely friendship between a spider and a pig. If you like animals then this story is definitely for you!

3. The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde

Difficulty: Easy

The Happy Prince is one of Oscar Wilde's best short stories. Well-known for its heartbreaking finale, this simple parable centers on the relationship between a talking statue and a tiny bird. The language is straightforward and the story is short but beautiful.

The language is straightforward and the story is short but beautiful.

4. A Series of Unfortunate Events by Lemony Snicket

Difficulty: Medium

This charming book is very useful for readers looking to improve their English; the author actually explains some of the more difficult words! As the title suggests, this novel doesn't have a happy ending, but it's a fantastic adventure all the same! It tells the story of a family of children who lose their parents and are made to live with the mysterious Count Olaf.

5. The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

Difficulty: Medium

The Wind in the Willows is another classic of British literature and has inspired readers for generations. Its simple language is easy to read and the story is engaging and fun. It centers around a river in the English countryside and the adventures of the animals that live around it.

6. The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

Difficulty: Hard

This short novel earned Hemingway the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954 and is one of the greatest works ever written. Beginners may find this novel a little more difficult than the others, however, Hemingway is renowned for having some of the cleanest prose and simplest writing styles of any legendary writers. This intensely human, emotional tale is about one fisherman's struggle against nature.

Any other books we should include in our list? Let us know in the comment section below! Find out more about how you can improve your English reading skills with one of our English language courses.

Share this with your friends

author: Lizzie Cooper-Smith (16 Posts)

Lizzie Cooper-Smith is the copywriter at Kaplan International Languages' UK HQ in London. English is her first language, but she speaks some French, Spanish and Portuguese, and has a keen interest in how we learn different languages. She loves to travel, and has been to places all around the world including the United States, Australia and many European cities.

She loves to travel, and has been to places all around the world including the United States, Australia and many European cities.

28 English Short Stories with Big Ideas for Thoughtful English Learners

By aromiekim and Dhritiman Ray Last updated:

When it comes to learning English, what if you can understand big ideas with just a little bit of text?

I’m talking about award-winning short stories in English.

Stories are all about going beyond reality, and these will not only improve your English reading but also open your mind to different worlds.

Contents

- 1. “The Bogey Beast” by Flora Annie Steel

- 2. “The Tortoise and the Hare” by Aesop

- 3. “The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse” by Beatrix Potter

- 4. “The Night Train at Deoli” by Ruskin Bond

- 5. “There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury

- 6.

“Orientation” by Daniel Orozco

“Orientation” by Daniel Orozco - 7. “Paper Menagerie” by Ken Liu

- 8. “The Missing Mail” by R.K. Narayan

- 9. “Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr

- 10. “The School” by Donald Barthelme

- 11. “Girl” by Jamaica Kincaid

- 12. “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi” by Rudyard Kipling

- 13. Excerpt from “Little Dorrit” by Charles Dickens

- 14. “To Build a Fire” by Jack London

- 15. “Evil Robot Monkey” by Mary Robinette Kowal

- 16. “The Boarded Window” by Ambrose Bierce

- 17. “The Zero Meter Diving Team” by Jim Shepherd

- 18. “The Monkey’s Paw” by W.W. Jacobs

- 19. “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

- 20. “Little Red Riding Hood” by The Brothers Grimm

- 21. “A Tiny Feast” by Chris Adrian

- 22. “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson

- 23. “The Velveteen Rabbit” by Margery Williams

- 24. “Paul Bunyan,” adapted by George Grow

- 25. “The Happy Prince” by Oscar Wilde

- 26. “Cinderella” by Charles Perrault

- 27.

“The Friday Everything Changed” by Anne Hart

“The Friday Everything Changed” by Anne Hart - 28. “Hills Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway

- How to Use Short Stories to Improve Your English

-

- Use Illustrations to Enhance Your Experience

- Listen to Recordings of Stories

- Explore Stories Related to a Theme

- Choose the Right Reading Level

- Practice “Active Reading”

- Choose Only a Few Words to Look Up

- Make Your Own Summary

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

A woman finds a pot of treasure on the road while she is returning from work.

Delighted (very happy) with her luck, she decides to keep it. As she is taking it home, it keeps changing.

However, her enthusiasm refuses to fade away (disappear or faint slowly).

What Is Great About It: The old lady in this story is one of the most cheerful characters anyone can encounter in English fiction.

Her positive disposition (personality) tries to make every negative situation seem like a gift, and she helps us look at luck as a matter of our view rather than events.

This classic fable (story) tells the story of a very slow tortoise (turtle) and a speedy hare (rabbit).

The tortoise challenges the hare to a race. The hare laughs at the idea that a tortoise could run faster than he, but the race leads to surprising results.

What Is Great About It: Have you ever heard the English expression, “Slow and steady wins the race”? This story is the basis for that common phrase.

This timeless (classic) short story teaches a lesson that we all know but can sometimes forget: Natural talent is no substitute for hard work, and overconfidence often leads to failure.

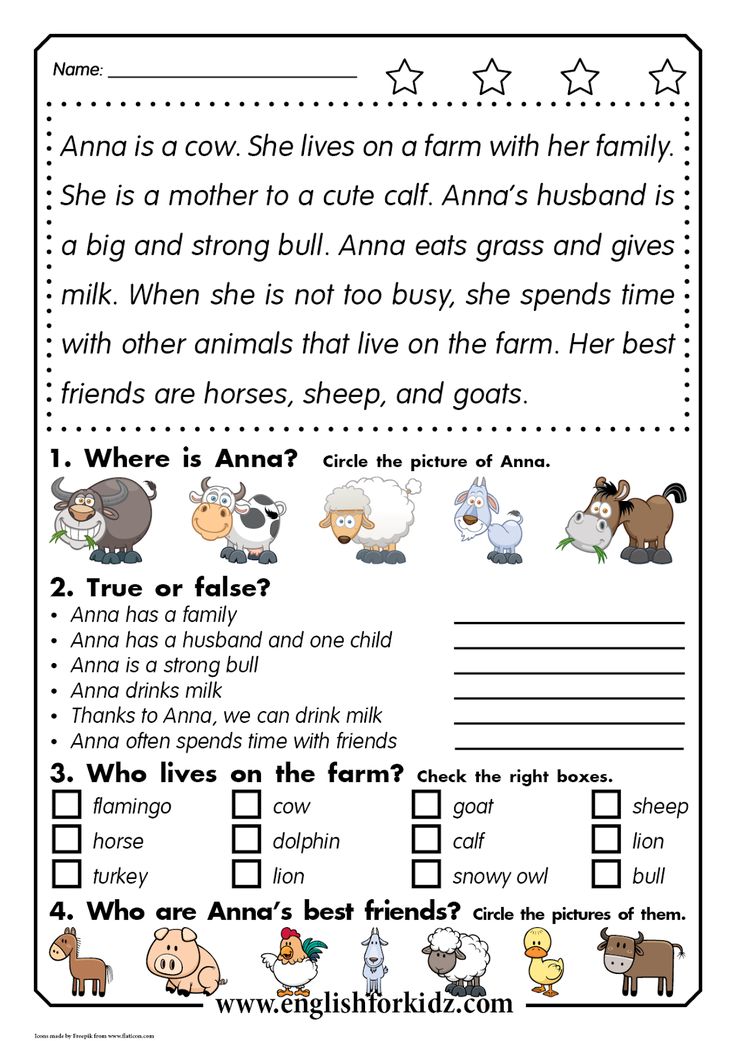

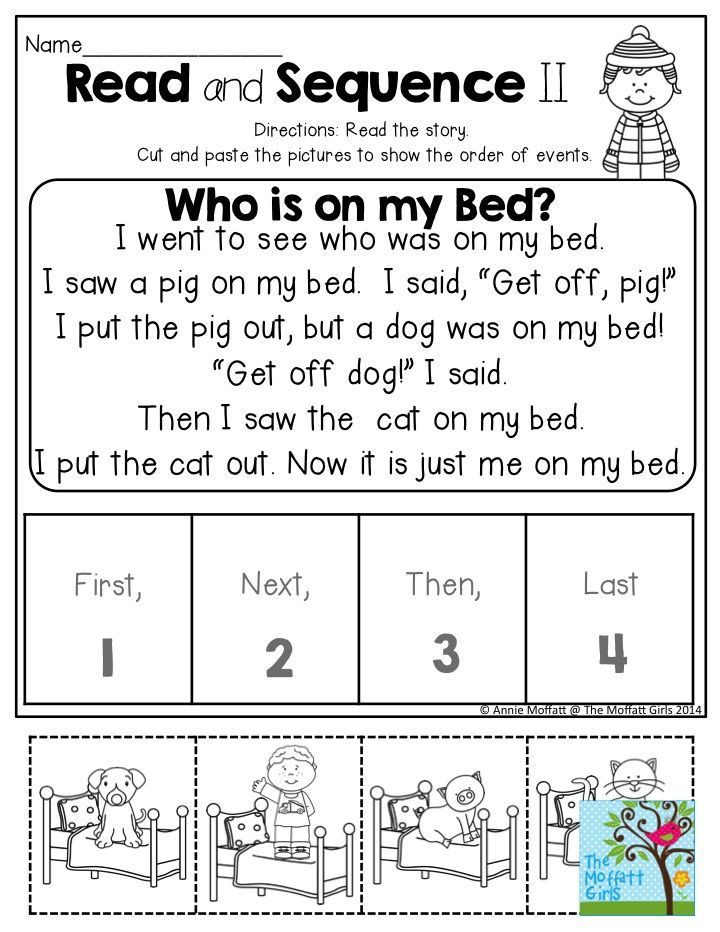

Timmie Willie is a country mouse who is accidentally taken to a city in a vegetable basket. When he wakes up, he finds himself at a party and makes a friend.

When he is unable to bear (tolerate or experience) the city life, he returns to his home but invites his friend to the village.

When his friend visits him, something similar happens.

What Is Great About It: Humans have been living without cities or villages for most of history.

That means that both village and city life are recent inventions. And just like every other invention, we need to decide their costs and benefits.

The story is precisely (exactly) about this debate. It is divided into short paragraphs and has illustrations for each scene. This is best for beginners who want to start reading immediately.

Ruskin Bond used to spend his summer at his grandmother’s house in Dehradun.

While taking the train, he always had to pass through a small station called Deoli. No one used to get down at the station and nothing happened there.

Until one day he sees a girl selling fruit and he is unable to forget her.

What Is Great About It: Ruskin Bond is a writer who can communicate deep feelings in a simple way.

This story is about our attachment to strangers and why we cherish (value or appreciate deeply) them even though we do not meet them ever again.

Earth has been destroyed by war and no one lives on it anymore.

The robots and the machines continue to function and serve human beings who have long ago died.

What Is Great About It: The title is taken from a poem that describes how nature will continue its work long after humanity is gone.

But in this story, we see that nature plays a supporting role and the machines are the ones who have taken its place.

They continue their work without any human or natural assistance. This shows how technology has replaced nature in our lives and how it can both destroy us and carry on without humanity itself.

This is a humorous story where the speaker explains the office policies, as well as gossip about the staff, to a new employee.

It is extremely easy to read as the sentences are short and without any overly difficult words.

Many working English learners will relate to it as it explains the absurdities (silly moments) of modern office life and how so little of it makes sense.

What Is Great About It: Modern workplaces often feel like theaters where we pretend to work rather than get actual work done. The speaker exposes this reality that nobody will ever admit to.

He over-explains everything from the view out the office window to the intimate details of everyone’s life—from the overweight loner to the secret serial killer.

It talks about the things that go unsaid; how people at the office know about the deep secrets of our home life, but do not talk about it.

Jack’s mother can make paper animals come to life.

In the beginning, Jack loves them and spends hours with his mom. But as soon as he grows up, he stops talking to her since she is unable to speak in English.

When his mother tries to talk to him through her creations, he kills them and collects them in a box.

After a tragic loss, he finally gets to know her story through a hidden message that he should have read a long time ago.

What Is Great About It: The story is a simple narration that touches on complex issues. It is about leaving your own country with the promise of a better life.

It is also about the conflicts that can occur between families when different cultures and languages collide. In this case, the tension is so high that it destroys the relationship between a mother and her son.

It also has a moving message about never taking your loved ones for granted.

This story is part of R.K. Narayan’s “Malgudi Days” short story collection.

Thanappa is the village mailman who is good friends with Ramanujam and his family. He learns about a failed marriage and helps Ramanujam’s daughter get engaged to a suitable match.

Just before the wedding, Thanappa receives a tragic letter about Ramanujam’s brother. He decides not to deliver it.

What Is Great About It: Despite the best of intentions, our actions can cause more harm to our loved ones than we ever intended.

The story is about the complicated relationships and feelings which are always present in our social circles, but we are often ignorant of them.

The year is 2081, and everyone has been made equal by force.

Every person who is superior in any way has been handicapped (something that prevents a person’s full use of their abilities) by the government.

Intelligent people are distracted by disturbing noises. Good dancers have to wear weights so that they do not dance too well.

Attractive people wear ugly masks so they do not look better than anyone else.

However, one day there is a rebellion, and everything changes for a brief instant.

What Is Great About It: Technology is always supposed to make us better. But in this case, we see that it can be used to disable our talents.

But in this case, we see that it can be used to disable our talents.

Moreover, the writer shows us how the mindless use of a single value like equality can create more suffering for everyone.

A school teacher is narrating all the recent incidents that have happened on campus.

First, they mention a garden where all the trees died. Pretty soon deaths of all kinds begin to occur.

What Is Great About It: Most of the adults do not know how to deal with death, even though they want to teach children about it.

It makes us realize how weak our education systems are because they can not help us deal with life’s most basic issues.

Eventually, the students start to lose faith in everything, and the adults have to put on a show of love to make themselves less frightened.

It shows how adults can fail to explain and understand death, and so they just pretend that they do. In this way, the cycle of misunderstanding and avoiding life’s issues continues.

11. “Girl” by Jamaica Kincaid

A mother is telling her daughter how to live her life properly. The daughter does not seem to have any say in it.

What Is Great About It: This may not be technically a story since there is no plot. “Girl” talks about how girls are taught to live restricted lives since childhood.

The mother instructs (tells) her to do all the household chores, indicating that it is her sole purpose (only aim or duty).

Sometimes the mother tells her to not attract attention, to not talk to boys and to always keep away from men.

On the other hand, she hints that she will have to be attractive to bakers and other suitable males in society to live a good life.

This story is about these conflicting ideas that girls face when growing up.

“Rikki-Tikki-Tavi” is about a Mongoose who regularly visits a family in India.

The family feeds him and lets him explore their house, but they worry that he might bite their son, Teddy.

One day a snake is about to attack him when the Mongoose kills it. Eventually, he becomes a part of the family forever.

What Is Great About It: This is a simple story about humans and animals living together as friends. It is old, but the language is fairly easy to understand.

It reminds us that animals can also experience feelings of love and, like humans, they will also protect the ones they love.

“Rikki-Tikki-Tavi” is part of Kipling’s short story collection “The Jungle Book,” which was famously made into a movie by Disney.

If you enjoy the story but need a break from reading, check out this captivating trailer for Disney’s newer version of the movie.

Dorrit is a child whose father has been in prison ever since she could remember. Unable to pay their debts, the whole family is forced to spend their days in a cell.

Dorrit thinks about the outside world and longs to see it (wishes to see it).

This excerpt introduces you to the family and their life in prison.

The novel is about how they manage to get out and how Dorrit never forgets the kindness of the people who helped her.

What Is Great About It: Injustice in law is often reserved for the poor. “Little Dorrit” shows clearly how it works in society.

It is about the government jailing people for not being able to return their loans, a historical practice the writer hated since his own father was punished in a similar way.

The story reveals how the rich cheat the poor and then put them into prisons instead of facing punishment.

A man travels to a freezing, isolated place called Yukon. He only has his dog with him for company.

Throughout his journey, he ignores the advice other people had given him and takes his life for granted.

Finally, he realizes the real power of nature and how delicate (easily broken) human life actually is.

What Is Great About It: The classic fight between life and death has always fascinated us. Nature is often seen as a powerful force that should be feared and respected.

The man in this story is careless and, despite having helpful information, makes silly mistakes. He takes the power of natural forces too lightly.

The animal is the one who is cautious and sensible in this dangerous situation. By the end, readers wonder who is really intelligent—the man who could not deal with nature or the dog who could survive?

Sly is a chimpanzee who is much smarter than the other chimpanzees. He loves to play with clay on a potter’s wheel all day and likes to keep to himself.

But one day when the school kids bully him, he loses his temper and acts out in anger. Seeing this, the teacher punishes him and takes away his clay.

What Is Great About It: Sly is a character who does not fit into society. He is too smart for the other chimps, but humans do not accept him. He is punished for acting out his natural emotions.

He is too smart for the other chimps, but humans do not accept him. He is punished for acting out his natural emotions.

But the way he handles his rage, in the end, makes him look more mature than most human beings. Nominated for the Hugo award, many readers have connected with Sly since they can see similarities in their own lives.

“The Boarded Window” is a horror story about a man who has to deal with his wife’s death. The setting is a remote cabin in the wilderness in Cincinnati, and he feels helpless as she gets sick.

There’s an interesting twist to this story, and the ending will get you thinking (and maybe feeling a bit disturbed!).

What is Great About It: If you enjoy older stories with a little suspense, this would be a good challenge for you–in fact, until now, it’s still included in a lot of horror story compilations.

It talks about the event that made a hermit decide to live alone for decades, with a mysterious window boarded up in his cabin.

Aside from what actually happens in the story, there’s also a lot of emphasis on psychology and symbolism.

The Chernobyl nuclear disaster was one of the most deadly accidents in the twentieth century.

This is a story about that event through the eyes of a father and his sons. The family was unfortunate enough to be close to the disaster area.

The story exposes the whole system of corruption that led to a massive explosion taking innocent lives and poisoning multiple generations.

The technical vocabulary and foreign words make this text a little more difficult. However, the story is relatively easy to follow.

What Is Great About It: It is no secret that governments lie to their own people. But sometimes these lies can cost lives.

Very often we accept this as normal, but this tale opens our eyes to the cost of our indifference (lack of concern).

The story is divided into small parts that make it both easy and exciting to read.

The various events are about life in general in what was then known as the Soviet Union. And just like any other good story, it is also about human relationships and how they change due to historic events.

A man brings a magical monkey’s paw from India, which grants three wishes to three people.

When the White family buys it from him, they realize that sometimes you do not want your wishes to come true.

What Is Great About It: Sometimes we wish for things, but we do not think about their consequences.

In this story, the characters immediately regret when their wishes come true because either someone dies or something worse happens.

They realize that they never thought about the ways their wishes could destroy people and their lives.

Mrs. Mallard has heart troubles that could kill her.

When her husband dies, the people who come to give her this news try to do so gently. When she is finally informed, she bursts into tears.

When she is finally informed, she bursts into tears.

Eventually, she goes to her room and locks herself in.

However, while thinking about the future, she is excited by the idea of freedom that could come after her husband’s death.

After an hour, the doorbell rings and her husband is standing there alive and well. When she sees him, she has a heart attack and dies.

What Is Great About It: Marriages can be like prisons for women. The one in this tale definitely seems like a heavy burden. Despite her grief, Mrs. Mallard is able to keep herself healthy with the hope of freedom from her husband.

But as soon as she realizes that she will have to go back to her old life, her body is unable to take it.

The story explores the conflicting range of human emotions of grief and hope in a short span, and the impact it can have on a person’s mind and body.

This is a story that every English-speaking child knows. It’s about a little girl who meets a wolf in the forest while going to see her sick grandmother.

It’s about a little girl who meets a wolf in the forest while going to see her sick grandmother.

The wolf pretends to be her grandmother in order to trick the little girl. There are actually different versions of it, with different endings–the one I’ve linked above is the most popular.

What Is Great About It: “Little Red Riding Hood” is a fairy tale, which is a story for kids that has been traditionally told through generations.

It’s often used to teach children that it’s bad to talk to strangers, since the image of being eaten by a wolf can be very scary.

It has been adapted into different movies and media, and you’ll still hear mentioned in pop culture a lot.

The basic characters are taken from Shakespeare’s famous play “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

However, in this story, the plot and the concept are entirely different.

Titania and Oberon are the rulers of fairies who have been dealing with problems in their marriage.

One day they find a human child and decide to adopt him. They hope that this child will help them save their relationship.

They hope that this child will help them save their relationship.

However, the child develops a deadly disease and the fairies have no idea what to do since they have never known illness or death.

This is a tragic tale about how they try to understand something they have never seen before and their deep love for a stranger who is so unlike them.

What Is Great About It: The story is able to explore human relationships through imaginary creatures. It explores the grief of parenthood and also the uncertainty of knowing whether your child will ever even know you.

It also beautifully captures the sense of the unknown and the helplessness which every human being faces when faced with it.

Every year, a small town holds an event known as “the lottery” that everyone attends.

During this event, someone from the community is randomly chosen…but for what reason?

What Is Great About It: The story makes you wonder about human behavior, particularly within a group of people.

Perhaps you may have heard of the term “mob mentality” and how it can allow for some pretty surprising things to happen.

This short story is considered to be one of the most famous short stories in American literature.

It shows an example of what is known as a dystopian society, where people live in a frightening way. To learn more, check out this TED-Ed video that tells you how to recognize a dystopia.

A simple, stuffed rabbit toy is given to a young boy as a Christmas present.

At first, the rabbit isn’t noticed, as the boy is distracted by much fancier gifts. While being ignored, the rabbit begins to wonder what it means to be “real.”

One day, a certain event brings the rabbit into contact with the boy. After that, the toy’s life changes dramatically (a lot).

What Is Great About It: Have you ever loved a toy or doll so much, that you treated it as if it were alive? This story shows the power of love from a very unexpected viewpoint: that of a fluffy stuffed rabbit.

The velveteen rabbit toy is loved dearly by its owner, regardless of how worn out he becomes.

Although this story was made for children, its message is for anyone of any age. The rabbit’s quest (journey) of becoming “real” can be understood in a very human way.

The story shows the importance of self-value, being true to yourself and finding strength in those who love you.

The story of Paul Bunyan has been around in the United States for many years. He’s the symbol of American frontier life, showing the ideal strength, work ethic and good morality that Americans work hard to imitate.

Some sources break down his story into even shorter versions.

What is Great About It: Paul Bunyan is considered a legend, so stories about him are full of unusual details, such as eating fifty eggs in one day and being so big that he caused an earthquake.

It can be a pretty funny read, with characters such as a blue ox and a dog that’s reversible.

This version of the story is also meant to be read out loud, so it’s fast-paced and entertaining.

In the middle of a city is a very fancy, decorated statue of a prince, and it is known as the Happy Prince.

One day, a swallow bird decides to rest on the statue, only to get wet by the tears of the crying statue.

The Prince, as it turns out, is not happy at all. When he was alive and living in his palace, he had no idea how much suffering was happening outside his home.

Now as a statue that stands high above the city, he can finally see the many injustices happening to the people.

At the Prince’s request, the swallow begins to take off pieces of the statue and give them away to the poor. Together, the two work to try and give what aid they can to the less fortunate.

What Is Great About It: It can be easy to ignore people who are struggling and having a hard time. However, it is not good to always “turn a blind eye” and pretend not to notice.

Sometimes, even one good deed (action) can make a big impact on both the person doing it and the person receiving it.

“The Happy Prince” is a story that shows the importance of charity and empathy. These two things can come with a lot of sacrifices, but you can gain a lot in other ways.

The story also points out that you should judge a person not by what they have, but by what they give.

You may already know the story of Cinderella; many people saw the Disney movie or read a children’s book of it.

However, there are actually many different versions of “Cinderella.”

This one by Charles Perrault is the most well-known one and is often the version told to children.

What Is Great About It: “Cinderella” is a loved story because it describes how a kind and hard-working person was able to get a happy ending.

Even though Cinderella’s stepsisters treated her awfully, Cinderella herself remained gentle and humble. It goes to show that even though you may experience hardships, it is important to stay kind, forgiving and mindful.

It goes to show that even though you may experience hardships, it is important to stay kind, forgiving and mindful.

Because only “strong boys” are allowed to do this, the girls are teased for being “weaker.”

Not only that, but the boys also get more privileges than the girls, such as being the first to get magazines.

One Friday, a girl asks the classroom teacher why girls are not allowed to get water as well. This one question causes a big reaction.

What Is Great About It: One brave act, from one brave person, can cause a big change for the better. In this story, a single girl speaks out against what she thinks is wrong.

Her courage surprises everyone, but she inspires the girls to stand up for themselves against the boys who mistreat them.

The story reflects on gender equality and how important it is to fight for fairness. Just because something is accepted as “normal” does not mean it is right.

At a Spanish train station, an American man and a young woman wait for a train that would take them to the city of Madrid.

The woman sees some faraway hills and compares them to “white elephants.”

This starts a conversation between the two of them, but what they discuss seems to have a deeper meaning.

What Is Great About It: This story is very well-known as a text that makes you “read between the lines”—in other words, you have to try to find a hidden meaning behind what you read.

Much of the story is a back-and-forth dialogue between two people, but you can tell a lot about them just from what they say to each other.

There is a lot of symbolism that you can analyze in this story, along with context clues. Once you realize what the real topic of the characters’ conversation is about, you can figure out the quiet, sadder meaning behind it.

How to Use Short Stories to Improve Your English

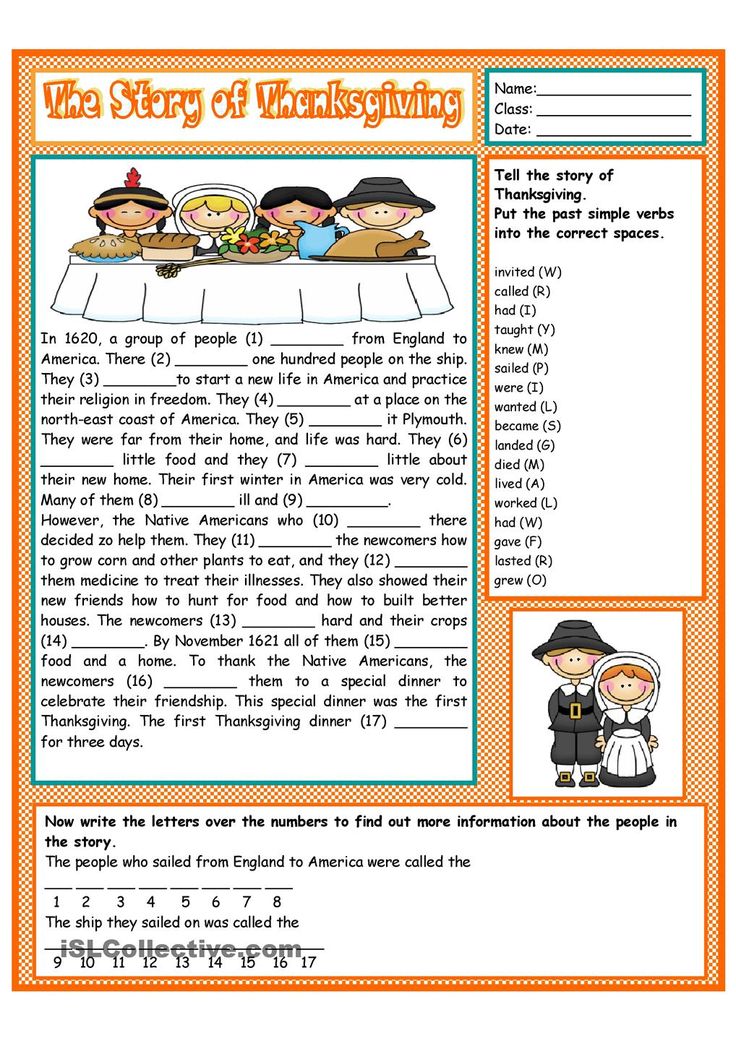

Short stories are effective in helping English learners to practice all four aspects of language learning: reading, writing, listening and speaking. Here’s how you can make the most out of short stories as an English learner:

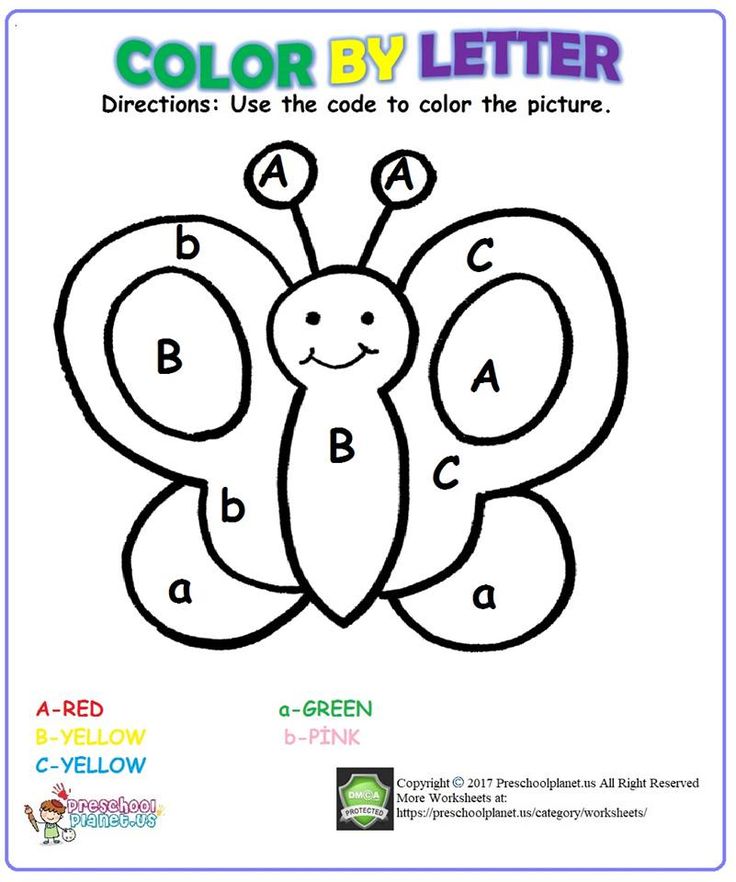

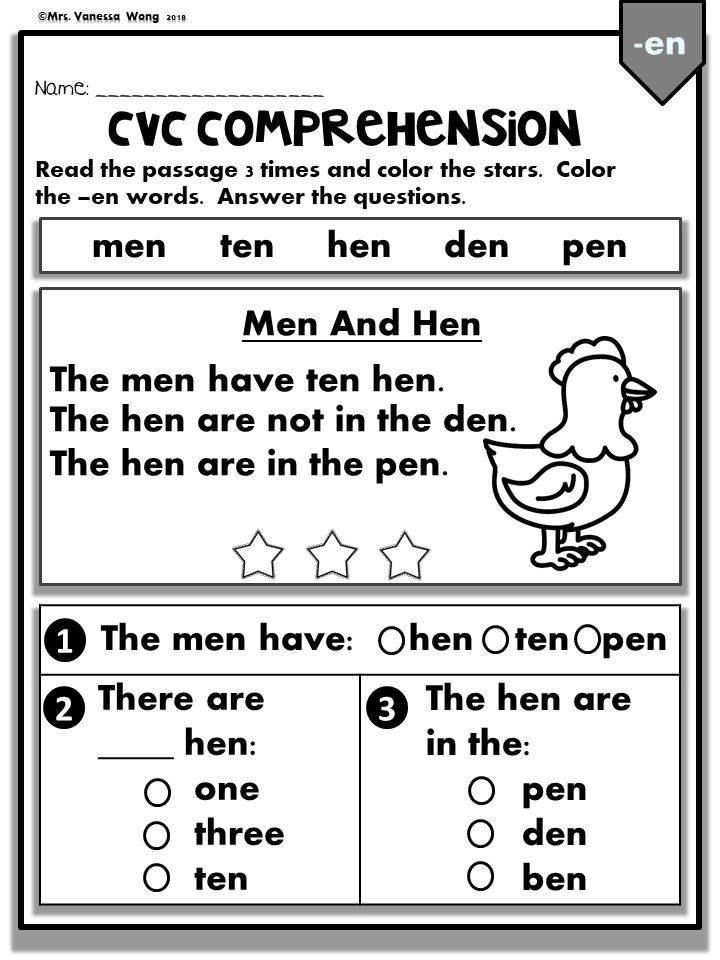

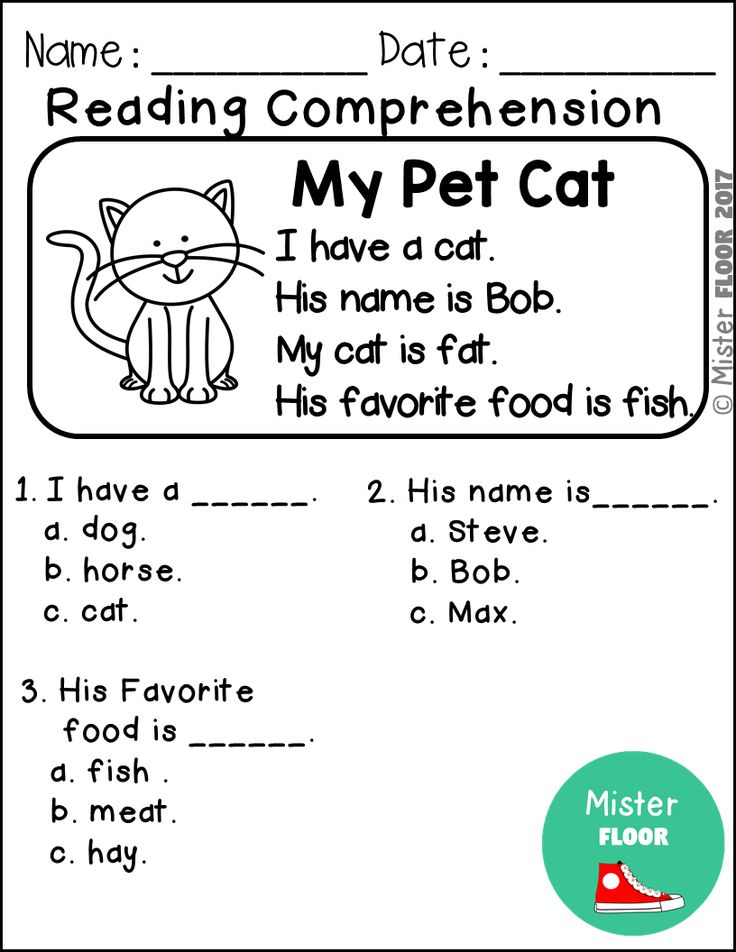

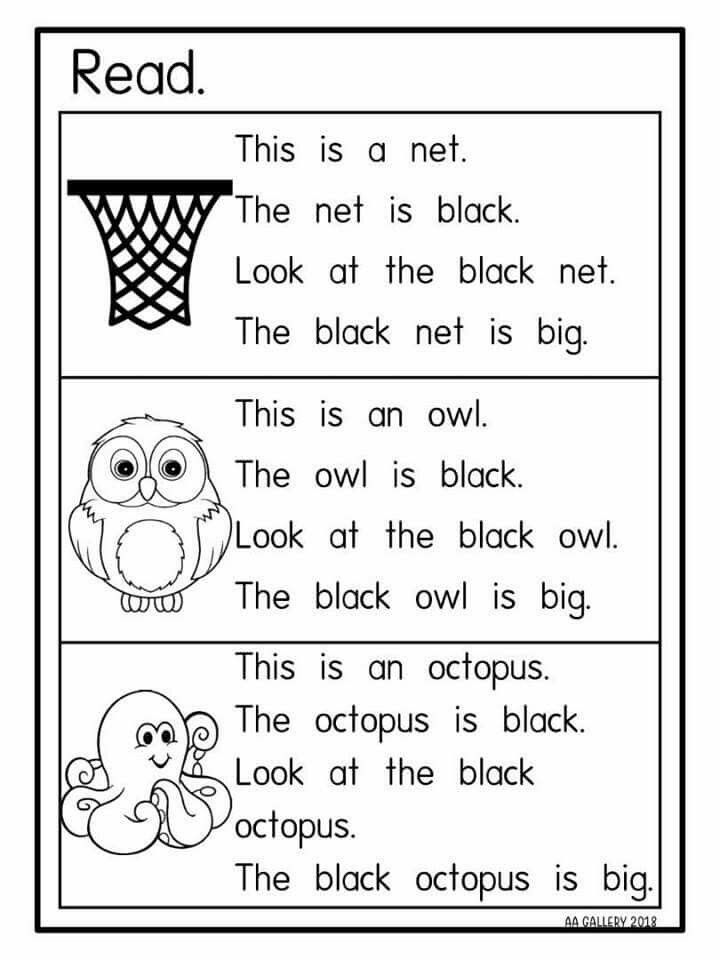

Use Illustrations to Enhance Your Experience

Some short stories come with illustrations. If you find a short story with illustrations, look at the pictures first to guess what the story is about.

If you find a short story with illustrations, look at the pictures first to guess what the story is about.

What are they doing in the illustration? What part of the story is illustrated? The illustrations will help you to understand the meaning of the story.

You can even write your own caption or description of the picture. It can be a sentence or one word.

When you look at the story, go back to your image description. How do they relate?

Listen to Recordings of Stories

In our fantastic digital age, it is possible to find wonderful short stories online in audio or video form.

If you find a video with English-language subtitles, you can read while also listening to how a native speaker pronounces words.

Some of the short stories above are available in video format on FluentU, which is an online English immersion program.

In addition to short story video tellings, the program has many types of authentic videos like movie clips, music videos and inspirational talks.

These can help you work on your listening comprehension and pronunciation alongside your reading skills. Each video has interactive subtitles and a video dictionary for unfamiliar words.

For example, here’s a video retelling of “The Tortoise and the Hare”:

If you’re doing a review quiz for the content, you have the option of speaking in the answers for some speaking practice.

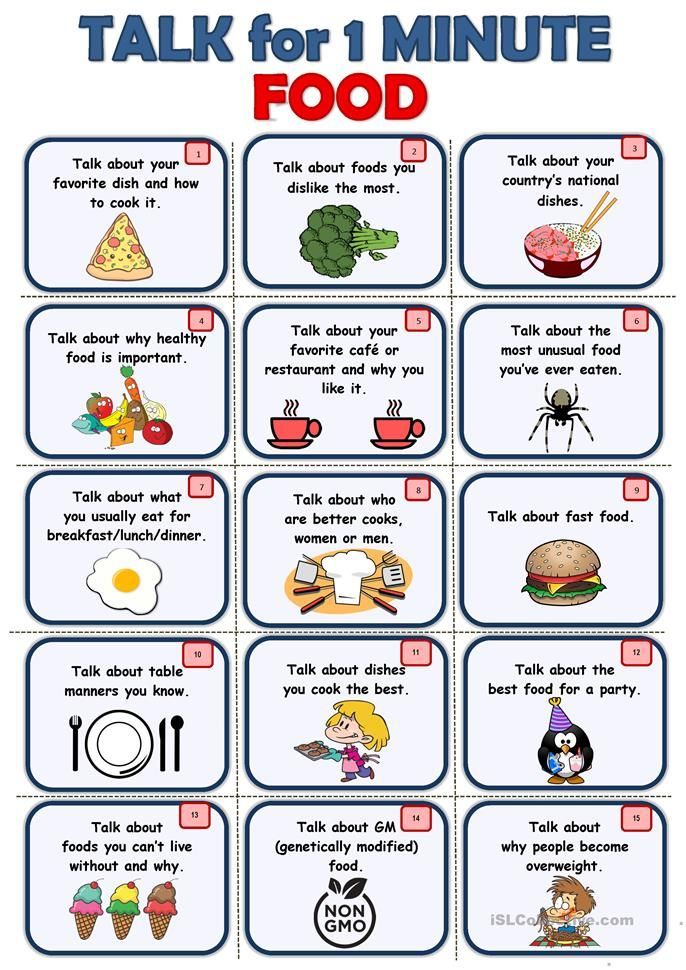

Explore Stories Related to a Theme

Like novels, short stories can be in any genre you can imagine. Do you like ghost stories? Science fiction? Romance?

You can find short stories, old and new, on the subject that you want. Some short stories teach a lesson, like fables do. Other short stories use a lot of metaphors or symbolism.

If you’re learning about hobbies, find a short story about something that you like to do. Are you learning about food? Find a short story with a lot of food vocabulary. The list goes on.

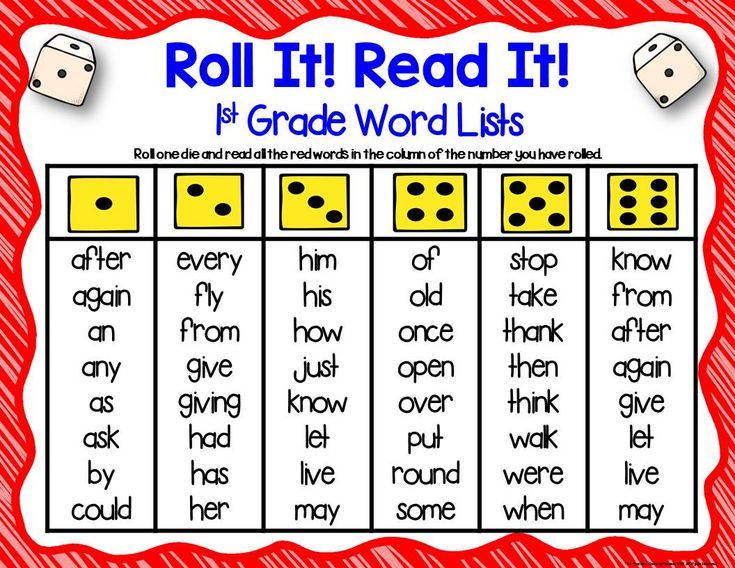

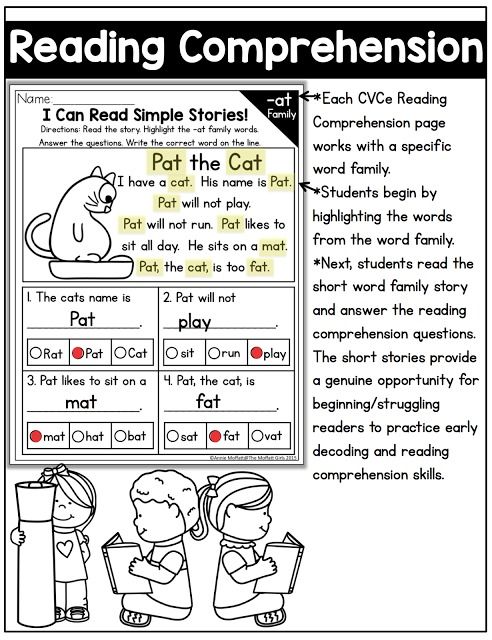

Choose the Right Reading Level

First, some short stories are over 5,000 words long while others can be as short as 50. When you’re selecting the right short story for you, you have many different types and lengths to choose from.

When you’re selecting the right short story for you, you have many different types and lengths to choose from.

If you choose a story that’s too difficult, you’ll spend too much time looking up vocabulary, missing the whole point of the story. If you choose a story that’s too easy, you’ll learn little to no new vocabulary and you may become bored.

Make sure that you always challenge yourself, even if you’re only learning a few new words.

Here’s an easy way to determine if the reading level is right for you.

Choose a paragraph in the story that you want to read. How many words can you identify?

Try the “five-finger test.” Hold up your fist while you read over the paragraph. Put up one finger for each word you don’t know. If you have all five fingers up before the end of the paragraph, try to find an easier text.

What if you really want to read a story, but the level is too hard? Try to read the story anyway. If the subject interests you, you’ll be motivated to learn the vocabulary you need to understand the story.

Bring the story to your English teacher. He or she will be happy to help you understand the words you don’t know so you’ll be able to enjoy the story on your own.

Practice “Active Reading”

Your reading will only help you learn if you read actively. You are reading actively when you’re paying very close attention to the story, its words and its meanings. Think about the vocabulary and grammar.

Start by looking over the text to get an idea of what the story is about. Read the text. Try to remember some of the things you read about. Finally, review the text again to get the best understanding.

Afterwards, discuss the story with your teacher and your classmates. If there’s something you don’t understand, write down your questions to ask during the discussion.

Talk about the stories and share your own opinions about the language, culture and messages within the story.

Choose Only a Few Words to Look Up

You don’t need to look up every single word you don’t know. Choose to look up only those words that will help you understand what the paragraph is about.

Choose to look up only those words that will help you understand what the paragraph is about.

If there’s a word you don’t know but you know everything else in the sentence, try to guess what the word is about by looking at the whole sentence. You can look this word up later to see if you guessed correctly.

For stories longer than 500 words, take breaks while you’re reading, especially if the vocabulary gets overwhelming. Don’t make yourself too tired, or you’ll become frustrated and give up.

If you find things are getting to be too difficult, walk away for about 15 minutes and come back and try again.

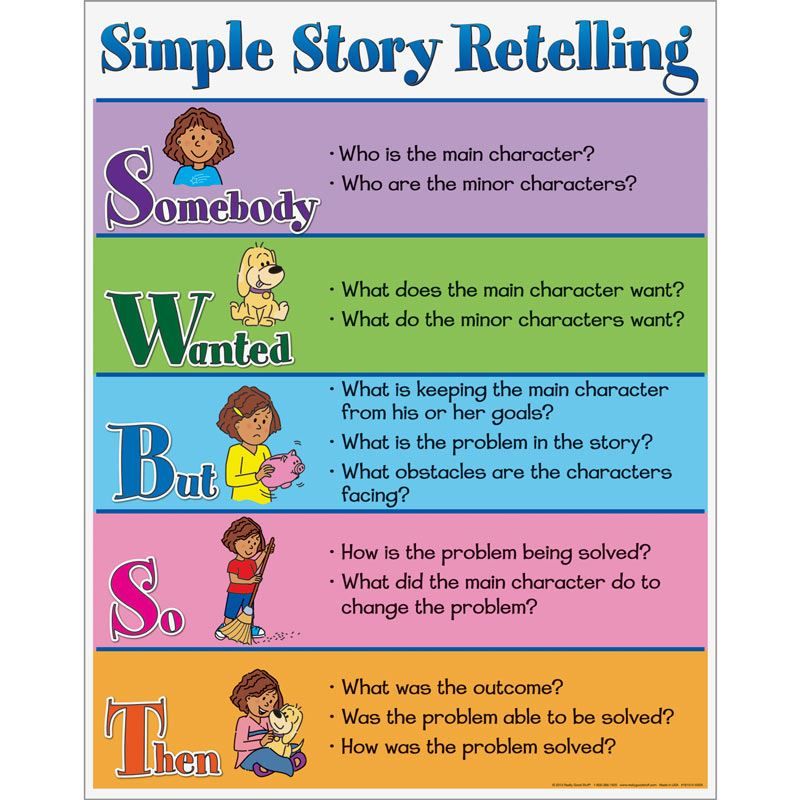

Make Your Own Summary

When you’ve finished reading the story, review it again. Do this later in the same day or the next day to let your reading really sink in. Take notes while you’re reading.

Retell the story or make a summary of the story to get even more practice.

You can make this more challenging by actually using the story as a model for writing your own English story. By writing your own stories, you get more practice in the use of vocabulary and creating your own sentences.

By writing your own stories, you get more practice in the use of vocabulary and creating your own sentences.

Why Short Stories Are Best for English Learning

Short stories are amazing resources for any English learner. That’s because:

- You can read a whole story in one sitting. Attention spans are very important for learning, and short stories are designed to give you maximum information with minimal effort.

- You get more time to focus on individual words. When a text is short, you can spend more time learning how every single word is used and what importance it has in the piece.

- It is best for consistency. It is far easier to read one story every day than trying to read a big novel that never seems to end.

- You can share them easily in a group. Since short stories can be read in a single sitting, they are ideal for book clubs and learning circles.

Most of the time these groups do not work because members have no time to read. Short stories are the perfect solution.

- You can focus more on ideas and concepts. Language is less about words and more about the meaning behind them.

If you spend all your time learning vocabulary and grammar, you will never be able to fluently speak a language because you will have little to talk about.

These short stories give you the opportunity to understand big ideas in context.

You can choose almost any short story and get something useful out of it. Each story has its own special features that you can appreciate.

The best kind of story will be one that is interesting, has a strong message and, of course, helps you to both practice and learn English.

It will be one that leaves an impact, both in your English education and in your imagination.

I hope you have fun with these stories while improving your English.

Happy reading!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

« Don’t Tell Me I Can’t! 12 Myths About Learning English

4 Top Resources for Help with Any Academic English Skill »

Reading for 15 minutes: "History of Reading" • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

- History

- Art

- Literature

- Anthropology

I'm lucky!

Literature, Anthropology

Alberto Mangel is an Argentine writer and publicist, head of the National Library in Buenos Aires. The Ivan Limbach Publishing House publishes a new edition of his book The History of Reading, translated by Maria Junger. Arzamas publishes an excerpt where Mangel recalls how he himself learned to read, and about a chance meeting with the blind Borges, which completely changed his life

Alberto Mangel, researcher, writer and publicist, was born in 1948 in Buenos Aires, but spent the first years of his life in Tel Aviv, where his father served as Argentina's ambassador to Israel. At the age of 16, studying at the National College of Buenos Aires, Mangel works in the Pygmalion bookstore, where he meets Jorge Luis Borges, and in 1964-1968 fulfills the duties of his reader (in the mid-1950s the writer went blind). He will call this period a turning point in his life.

B 19In the 70s, Alberto Mangel lived in France, Great Britain and Italy, where he found the friendly support of Julio Cortazar. He managed to briefly return to Argentina before the 1976 military coup, then went to Tahiti. Mangel collaborated with well-known publishing houses in Paris and London, tried himself in many forms of working with text, including journalism. In 1980, the first edition of his The Dictionary of Imaginary Places was published: this guide to the cities, islands and countries found in mythology and literature will be reprinted many times.

In the early 1980s, Mangel moved to Canada, where he spent about twenty years. In 1983, he prepared for publication an anthology of fantastic literature "Black Water" ("Black Water: The Book of Fantastic Literature"). At the same time, Mangel was engaged in literary translation, began teaching and lecturing (which he continues to do today). In 1992, his novel News from a Foreign Country Came won the McKittrick British Literary Award.

At the same time, Mangel was engaged in literary translation, began teaching and lecturing (which he continues to do today). In 1992, his novel News from a Foreign Country Came won the McKittrick British Literary Award.

In the early 2000s, Mangel returned to live in Europe, in the French province of Poitou. His legendary library of more than 30,000 books also moves there. Books and libraries as repositories of collective memory is a motif that is always present in his writings.

Sign the petition to help the book business

And help save publishers, bookstores and books

www.change.org

I first discovered I could read when I was four years old. Many times I have seen letters which I knew (because I was told so) to form the names of pictures. The boy, drawn in thick black lines, dressed in red shorts and a green shirt (all other images in the book were cut from the same material - dogs, cats, trees and skinny tall mothers), at the same time was three black icons located under the picture , as if his figure was embodied in them: the arm and torso in the letter "b"; round head in "o" and limp crossed legs in "y". <…>

<…>

Another reader - probably my nanny - explained the meaning of the letters to me, and now every time I saw a picture of this amazing boy, I knew what the icons under it meant. It was nice, but quickly became boring. The effect of surprise is gone.

And then one fine day from the car window (the purpose of that trip has long been forgotten) I saw a sign on the road. I hardly looked at her for a long time; most likely the car stopped for a moment or just slowed down, and yet I managed to make out large luminous letters, the same as those in my book, but in a combination that I had never seen before. And then I suddenly understood what they meant; I heard them in my head, from black lines on a white background they turned into a reliable, clear, obvious reality. I did it myself. No one helped me perform a miracle. We had a silent, respectful dialogue with the letters. I managed to turn simple lines into a living reality and became omnipotent. I learned to read. <…>

The readers into whose family I have unknowingly entered (we always feel that we are alone in our discoveries and that all our experience, from birth to death, is frighteningly unique), are united by the common art for all of us. Reading letters on a page is just one of its facets. An astronomer reading an ancient map of the starry sky, which now looks very different; a Japanese architect reading the land on which the house will be built to protect it from evil forces; a zoologist reading animal tracks in the forest; a card player who reads his partner's facial expressions before making a winning move; the dancer reading the directions of the choreographer and the audience reading the dancer's movements; a weaver reading the complex pattern of a future carpet; an organist reading the music recorded on the page; a mother reading a child's face in search of joy, fear, or curiosity; a Chinese soothsayer reading ancient signs on a tortoise shell; the lover who reads the body of his beloved in the night under the sheet; a psychiatrist who helps patients read their own frightening dreams; a Hawaiian fisherman reading ocean currents with his hand in the water; a farmer reading the weather in the sky—they all know the art of interpreting signs.

Reading letters on a page is just one of its facets. An astronomer reading an ancient map of the starry sky, which now looks very different; a Japanese architect reading the land on which the house will be built to protect it from evil forces; a zoologist reading animal tracks in the forest; a card player who reads his partner's facial expressions before making a winning move; the dancer reading the directions of the choreographer and the audience reading the dancer's movements; a weaver reading the complex pattern of a future carpet; an organist reading the music recorded on the page; a mother reading a child's face in search of joy, fear, or curiosity; a Chinese soothsayer reading ancient signs on a tortoise shell; the lover who reads the body of his beloved in the night under the sheet; a psychiatrist who helps patients read their own frightening dreams; a Hawaiian fisherman reading ocean currents with his hand in the water; a farmer reading the weather in the sky—they all know the art of interpreting signs. Some of these signs were created for a specific purpose by other people (such as musical notes or road signs) - or by gods - like a tortoiseshell or the night sky. Others are random. But, one way or another, it is the reader who understands their meaning; the reader finds reading material in some object, place or event; the reader communicates the meaning to the sign system and subsequently deciphers it. We all read ourselves and the world around us in the hope of understanding who we are and where we are. We read to understand, or at least begin to understand. We simply have no other choice. Reading is as essential to a person as breathing. <…>

Some of these signs were created for a specific purpose by other people (such as musical notes or road signs) - or by gods - like a tortoiseshell or the night sky. Others are random. But, one way or another, it is the reader who understands their meaning; the reader finds reading material in some object, place or event; the reader communicates the meaning to the sign system and subsequently deciphers it. We all read ourselves and the world around us in the hope of understanding who we are and where we are. We read to understand, or at least begin to understand. We simply have no other choice. Reading is as essential to a person as breathing. <…>

After I learned how to spell words, I began to read everything: books, notes, advertisements, tram tickets, letters thrown in the trash, yellowed newspapers found under a park bench, graffiti, magazine covers read by other passengers bus. I understood very well why Cervantes, in his thirst for reading, read "even scraps of paper lying on the street" Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra. The cunning hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha. Translation by N. Lyubimov .. This reverence for the book (on parchment, on paper or on the screen) can be called the cornerstone of an educated society. Islam went even further: the Qur'an is not only one of the creations of God, but also one of the attributes of God, just like omnipresence or compassion.

The cunning hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha. Translation by N. Lyubimov .. This reverence for the book (on parchment, on paper or on the screen) can be called the cornerstone of an educated society. Islam went even further: the Qur'an is not only one of the creations of God, but also one of the attributes of God, just like omnipresence or compassion.

<…> I think I read in at least two ways. There were books that I swallowed whole with bated breath, followed the development of the plot, carelessly neglecting the details, turning the pages at an accelerated pace - this is how I read Rider Haggard, The Odyssey, Conan Doyle and Karl May, the German writer of stories about the Wild West. Others I read very slowly, rereading the text in search of new meanings, enjoying the very sound of the words and what the words hid from me that I suspected was too terrible or too beautiful to remain on the surface. Books of this type - they have something of a detective - I attributed Lewis Carroll, Dante, Kipling and Borges. In addition, I read books in accordance with the impression that I had before reading (according to the author, publisher or other reader). At twelve I read Chekhov's "The Hunt" in a series of detective stories and became convinced that Chekhov was a Russian writer specializing in thrillers. Subsequently, I perceived The Lady with the Dog as a work from the pen of competitor Conan Doyle - and enjoyed it, although I found the intrigue rather transparent. <…>

In addition, I read books in accordance with the impression that I had before reading (according to the author, publisher or other reader). At twelve I read Chekhov's "The Hunt" in a series of detective stories and became convinced that Chekhov was a Russian writer specializing in thrillers. Subsequently, I perceived The Lady with the Dog as a work from the pen of competitor Conan Doyle - and enjoyed it, although I found the intrigue rather transparent. <…>

I wanted to live among books. In 1964, when I was sixteen, I started an after-school job at Pygmalion, one of three Anglo-German bookstores in Buenos Aires. The shop was owned by Lili Lebach, a Jewish woman from Germany who fled the Nazis in the late 1930s. It was my job to dust every single book in the store every day - Lily thought (and rightly so) that in this way I would quickly study the assortment and know exactly where which book was located. <…>

<…>

Jorge Luis Borges came into our shop one evening, accompanied by his 88-year-old mother. He was famous, but I only read a few of his poems and stories and was not particularly enthusiastic. Borges is almost completely blind. He refused to use a stick and held out his hands to the shelves as if his fingers could see the titles. He was looking for books that could help him learn Anglo-Saxon, his last passion, and we offered him Skeat's dictionary and The Battle of Maldon, The Battle of Maldon, an artistically brilliant historical song of late Anglo-Saxon literature. The real events that served as the basis for the song refer to 991, when, in the reign of King Æthelred the Indecisive, England was subjected to Scandinavian invasions. with comments. Borges' mother began to lose patience. "Oh Jorge," she said, "I don't know why you're wasting your time on Anglo-Saxon instead of learning something useful like Latin or Greek!" Finally he turned to me and asked for some books. Some I found, others I wrote down, and as he was about to leave, he asked if I was very busy in the evenings - he needed (he said this very apologetically) someone who could read to him, because his mother gets tired quickly. I agreed.

I agreed.

For the next two years, in the evenings, and if I could miss school, then in the mornings, I read to Borges, as did many other lucky people and casual acquaintances. The ritual was the same. Ignoring the elevator, I walked up the stairs (very similar to the one that Borges once climbed with a brand new volume of "Tales of 1001 Nights"; he did not notice the open window and was badly injured, the wound became inflamed, he began to delirium, and it seemed that he goes crazy), called, and the maid escorted me through the curtained door into the small living room, where Borges was already meeting me with a soft hand outstretched for greeting. There were no preliminary conversations; he sat down on the couch, I took my place in the chair, and, slightly out of breath, he offered the program for the evening. “Well, why don’t we take on Kipling today? A?" Of course, he did not expect an answer.

In this living room, under a Piranesi engraving depicting Roman ruins, I read Kipling, Stevenson, Henry James, several articles from the German Brockhaus Encyclopedia, poems by G. Marino, Enrique Bunches, Heine (although he knew the latter by heart, and I hardly he had time to start reading, when his stammering voice intervened and continued from memory; moreover, he stammered only in rhythm, not in words that he knew by heart). Most of the authors I had not read before, so our ritual was very curious: I discovered the text by reading it aloud, and Borges used his ears, as other readers use their eyes, to find a word, sentence or paragraph on the page that will confirm his memory. . During the reading, he often interrupted me, commenting on what he heard in order to (I think) focus on something.

Marino, Enrique Bunches, Heine (although he knew the latter by heart, and I hardly he had time to start reading, when his stammering voice intervened and continued from memory; moreover, he stammered only in rhythm, not in words that he knew by heart). Most of the authors I had not read before, so our ritual was very curious: I discovered the text by reading it aloud, and Borges used his ears, as other readers use their eyes, to find a word, sentence or paragraph on the page that will confirm his memory. . During the reading, he often interrupted me, commenting on what he heard in order to (I think) focus on something.

So, for example, stopping me after what he thought was a completely hilarious line from Stevenson's Suicide Club (“Colonel Geraldine was dressed and disguised as a press knight in somewhat cramped circumstances” Robert Stevenson. Suicide Club. Translation by T. Litvinova. - "How can a person be dressed in such a way? What do you think Stevenson meant, given that he is always incredibly accurate? Eh?"), He proceeded to analyze the stylistic device, in which someone or something is characterized with the help of images that seem to be accurate, but in fact force the reader to draw their own conclusions. He and his friend Adolfo Bioy Casares played on this idea in a nine-word piece: "Someone is walking up the stairs in the dark: thump thump thump."

- "How can a person be dressed in such a way? What do you think Stevenson meant, given that he is always incredibly accurate? Eh?"), He proceeded to analyze the stylistic device, in which someone or something is characterized with the help of images that seem to be accurate, but in fact force the reader to draw their own conclusions. He and his friend Adolfo Bioy Casares played on this idea in a nine-word piece: "Someone is walking up the stairs in the dark: thump thump thump."

When I was reading Kipling's story "Beyond the Fence" to Borges, he interrupted me after a scene in which an Indian widow sends a message to her lover, composed of various objects. He noted the poetic veracity of this, and wondered aloud whether Kipling himself invented this precise and capacious symbolic language At the time, neither I nor Borges knew that Kipling's messages were not his invention. According to Ignace J. Gelb. The History of Writing [Chicago, 1952]), in East Turkestan, a young woman sent her lover a handful of tea, a blade of grass, a red fruit - a dried apricot, an ember, a flower, a sugar cube, a pebble, a falcon feather and a nut. The message read: “I can’t drink tea anymore, I turned yellow like a blade of grass without you, I blush when I think of you, my heart burns like coal, you are beautiful like a flower and sweet like sugar, is your heart made of stone? I would fly to you if I had wings, I belong to you like a nut in your hand. Note. author.. Then, as if rummaging through a mental library, he compared it with the "philosophical language" of John Wilkins, in which each word is its own definition. <...> Sometimes he used reading in his own work. The ghostly tiger in Kipling's "Forward Rear Drummers," which we read shortly before Christmas, inspired one of his last stories, "The Blue Tigers"; "Two reflections in a pond" by Giovanni Papini led to the appearance of "August 24, 1982 years" - then this date still belonged to the future; the annoyance that Lovecraft caused him (we started and stopped reading his stories dozens of times) led to the emergence of a "corrected" version of one Lovecraft story - it appeared in the Brody Message.

The message read: “I can’t drink tea anymore, I turned yellow like a blade of grass without you, I blush when I think of you, my heart burns like coal, you are beautiful like a flower and sweet like sugar, is your heart made of stone? I would fly to you if I had wings, I belong to you like a nut in your hand. Note. author.. Then, as if rummaging through a mental library, he compared it with the "philosophical language" of John Wilkins, in which each word is its own definition. <...> Sometimes he used reading in his own work. The ghostly tiger in Kipling's "Forward Rear Drummers," which we read shortly before Christmas, inspired one of his last stories, "The Blue Tigers"; "Two reflections in a pond" by Giovanni Papini led to the appearance of "August 24, 1982 years" - then this date still belonged to the future; the annoyance that Lovecraft caused him (we started and stopped reading his stories dozens of times) led to the emergence of a "corrected" version of one Lovecraft story - it appeared in the Brody Message. Often he asked me to write something down on the flyleaf of the book we were reading - a link to the desired chapter or some thought. I do not know how he used it, but he adopted the habit of writing about books on their pages.

Often he asked me to write something down on the flyleaf of the book we were reading - a link to the desired chapter or some thought. I do not know how he used it, but he adopted the habit of writing about books on their pages.

There is a story by Evelyn Waugh in which a man who saved another in the wilds of the Amazonian jungle forces the rescued man to read Dickens aloud to him for the rest of his life See: Evelyn Waugh. A handful of dust. Translation by L. Bespalova .. I never perceived reading to Borges as a simple performance of duty; on the contrary, it was something like a pleasant addiction. I admired not even the texts that he forced me to rediscover (many of them, in the end, became my favorites), but his comments, which shone with the most extensive, but not at all intrusive erudition, were very funny, sometimes cruel, and almost always immutable. I felt like the proud owner of a unique, carefully commented edition, compiled for me personally. Of course, it wasn't like that; I (like many others) was just his notebook, a memo needed for a blind person to put his thoughts in order. And I readily allowed myself to be used in this way.

And I readily allowed myself to be used in this way.

Before I met Borges, I always read to myself, or at the very least, others read aloud to me the books I chose. Reading aloud to an old blind man revealed a lot of new things, because, despite the fact that I managed, although not without difficulty, to control the pace and tone of reading, it was Borges, the listener, who had power over the text. I was the driver, but the terrain we were driving through belonged to a passenger who had no other task than to unravel the mystery of the land spread outside the windows. Borges chose a book, Borges stopped me or asked me to continue, Borges interrupted the reading to comment on something, Borges let the words come to him.

<…> A year before graduation, in 1966, when the military junta of General Ongania came to power, I discovered another system for sorting books. Certain books and certain authors were considered communist and placed on a special list. During constant police raids in bars, cafes, bus stops and just on the streets, the absence of suspicious books mattered as much as the presence of the necessary documents. Banned authors—Pablo Neruda, Jerome David Salinger, Maxim Gorky, Harold Pinter—formed their own history of literature, since the connection between them was visible only to the keen eye of the censor.

Banned authors—Pablo Neruda, Jerome David Salinger, Maxim Gorky, Harold Pinter—formed their own history of literature, since the connection between them was visible only to the keen eye of the censor.

But not only the totalitarian government is afraid of reading. Readers are disliked in locker rooms and schoolyards, in prisons and government offices. Almost everywhere, the reading community has a dubious reputation for its high profile and apparent strength. Something about the special relationship between the reader and the book seems wise and fruitful, but on the other hand they imply a certain exclusivity, perhaps because the image of a person huddled in a corner, indifferent to worldly temptations, suggests an impenetrable desire for solitude, selfishness and a certain secret. (“Go live!” my mother used to say to me when she saw me reading a book, as if my occupation contradicted her ideas of what is called life. ) The general fear of what the reader might find between the pages of a book is akin to that eternal horror which men experience in front of the innermost particles of the female body, or ordinary people in front of what witches and sorcerers do in the dark behind closed doors. According to Virgil, the Gate of False Hope is made of ivory; Saint-Beuve believes that the reader's tower is made of the same material.

) The general fear of what the reader might find between the pages of a book is akin to that eternal horror which men experience in front of the innermost particles of the female body, or ordinary people in front of what witches and sorcerers do in the dark behind closed doors. According to Virgil, the Gate of False Hope is made of ivory; Saint-Beuve believes that the reader's tower is made of the same material.

Borges once said that at one of the demonstrations organized by the Peron government in 1950 against dissenting intellectuals, the demonstrators chanted: “Yes to shoes, no to books!” The objection "yes to shoes, yes to books" would not convince anyone. Reality - cruel, obvious reality - inevitably had to collide with the fictional world of books. For this reason, and all with great effect, the authorities everywhere tried to exacerbate the artificially created split between reading and real life. Popular regimes need us to lose our memory, which is why they call books a useless luxury; totalitarian regimes need us not to think, and therefore they ban, destroy [books] and impose censorship; both need to turn us into fools who will calmly accept their degradation, and therefore they prefer to encourage the consumption of nonsense. Under such circumstances, readers have no choice but to start an uprising.

Under such circumstances, readers have no choice but to start an uprising.

And so I confidently move from my reading history to the history of the reading process itself. Or rather, a story about reading—consisting of various personal circumstances—it will most certainly be just one of the stories, no matter how dispassionate it may be. Perhaps, after all, the history of reading is the history of readers. It even started by accident. In a review of a book on the history of mathematics published in the mid-1930s, Borges wrote that it had one "unfortunate flaw: the chronological order of events does not fit in with their natural and logical order. The definition of the elements of theory often comes last, practice precedes theory, for the unprepared reader, the works of the first mathematicians are less clear than those of their modern colleagues” J. L. Borges. Review of Men of Mathematics by E. T. Bell // El Hogar (Buenos Aires). July 8.1938. Approx. author.. Almost the same can be said about the history of reading. Its chronology cannot coincide with the chronology of political history. The Sumerian scribe, for whom reading was the most valuable privilege, felt his responsibility much more acutely than the readers of modern New York or Santiago, since it depended on his personal interpretation how people understood the article of laws or the account. The reading theory of the late Middle Ages, which determined when and how to read, and divided texts into those that should be read aloud and those that read only to themselves, was much more clearly formulated than a similar theory adopted at the end of the 19th century in Vienna or in Edwardian England. <...> The history of reading is not compatible with the chronology of the history of literature, because often the author begins his life in literature not thanks to the first book, but thanks to future readers: the Marquis de Sade was rescued from the dusty closet of pornographic literature, where his books spent more than 150 years , the bibliophile Maurice Heine and the French surrealists; William Blake, about whom no one has heard anything for more than two centuries, has been reborn in our time thanks to Sir Geoffrey Keynes and Northrup Fry - it is thanks to them that his works are now in the curriculum of any college.

Its chronology cannot coincide with the chronology of political history. The Sumerian scribe, for whom reading was the most valuable privilege, felt his responsibility much more acutely than the readers of modern New York or Santiago, since it depended on his personal interpretation how people understood the article of laws or the account. The reading theory of the late Middle Ages, which determined when and how to read, and divided texts into those that should be read aloud and those that read only to themselves, was much more clearly formulated than a similar theory adopted at the end of the 19th century in Vienna or in Edwardian England. <...> The history of reading is not compatible with the chronology of the history of literature, because often the author begins his life in literature not thanks to the first book, but thanks to future readers: the Marquis de Sade was rescued from the dusty closet of pornographic literature, where his books spent more than 150 years , the bibliophile Maurice Heine and the French surrealists; William Blake, about whom no one has heard anything for more than two centuries, has been reborn in our time thanks to Sir Geoffrey Keynes and Northrup Fry - it is thanks to them that his works are now in the curriculum of any college.

It is said that we, today's readers, are in danger of extinction, and therefore we must finally know what reading is. Our future - the future of the history of reading - was analyzed by Blessed Augustine, who tried to determine the difference between a text conceived and a text spoken aloud; Dante, who wondered if there were limits to the reader's ability to interpret a text; Murasaki Shikibu, who advocated an independent choice of reading order; Pliny, who studied the very process of reading and the relationship between the writer who reads and the reader who writes; the Sumerian scribes, who gave the act of reading political power; early bookmakers who found reading scrolls (similar to the way we use them on our computers today) too clumsy and restrictive, and instead gave us the ability to turn pages and take notes in the margins. The past of this story is before us, and on the last page, as a threatening warning, is the future described by Ray Bradbury in the story Fahrenheit 451, when books were stored in memory, and not on paper.

Like the process of reading, the history of reading is easily transferred to our time - to me, to my reading experience - and then returns back to distant pages of the past. She skips chapters, scrolls, chooses, rereads, refuses to follow the accepted path. Paradoxically, the fear that contrasts the reading of ordinary life that made my mother take the book from me and drive me out into the street recognizes the sad truth: “You cannot start life again, this one-way trip, after it is over,” writes Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk in the book "White Fortress" - but if you have a book in your hands, no matter how difficult it is to understand, after you finish it, you can, if you want, go back to the beginning and re-read it anew, to understand all the difficult places and thus understand life itself" Orkhan Pamuk. White fortress. Translation by V. Feonova..

Tags

Reading for 15 minutes

Microstrues

Daily short materials that we produced for the past three years

Frescoes of the day

Riddles from Pompeii

Advertising of the day

Polt

Hike

Soto about autumn

Archive

Anthropology

Rice, the walking dead, wax-painted textiles and paper roosters

About the projectLecturersTeamLicencePrivacy PolicyFeedback

Radio ArzamasGooseGooseArzamas stickers

OdnoklassnikiVKYouTubePodcastsTwitterTelegramRSSHistory, literature, art in lectures, cheat sheets, games and expert answers: new knowledge every day

© Arzamas 2023. All rights reserved

All rights reserved

4 90 Taylor Reading book 1. Simple stories. English

Catalog

Free shipping on orders over $4000.00

Delivery Payment

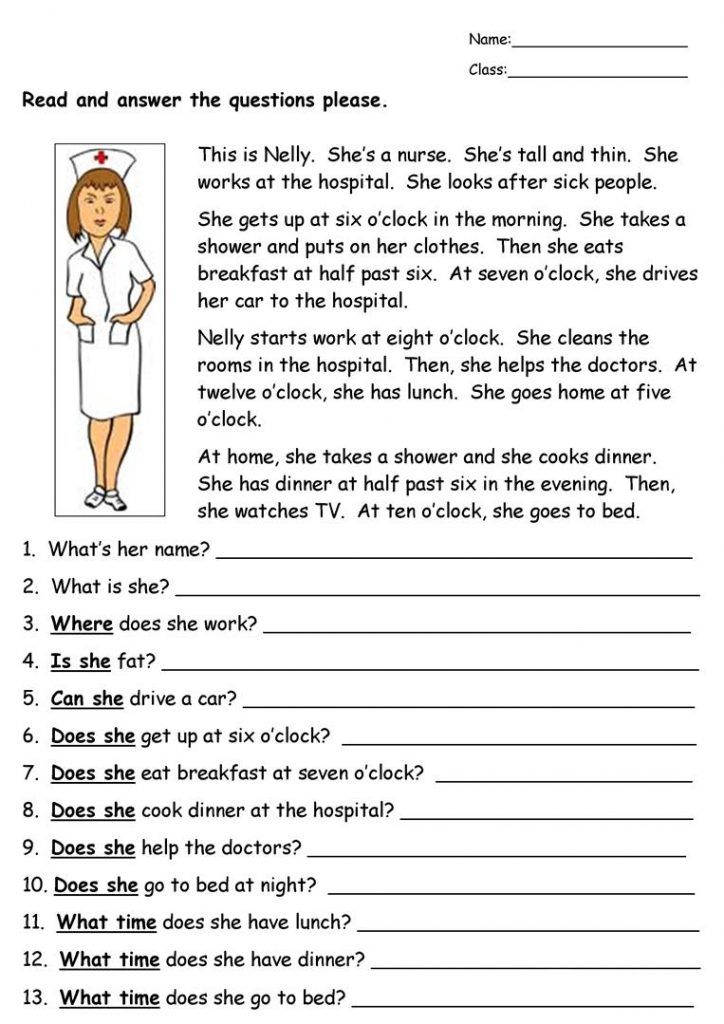

Anna Taylor. Reading book 1. Simple stories. English

| Author | Anna Taylor / Anna Taylor |

| Publisher | Title |

| ISBN | 978-5-86866-917-0 |

| Weight, g | 176 |

| Dimensions | 27.5 x 20 cm |

| Number of pages | 72 | Cover type | cover |

Price: $368. 00

00

Quantity

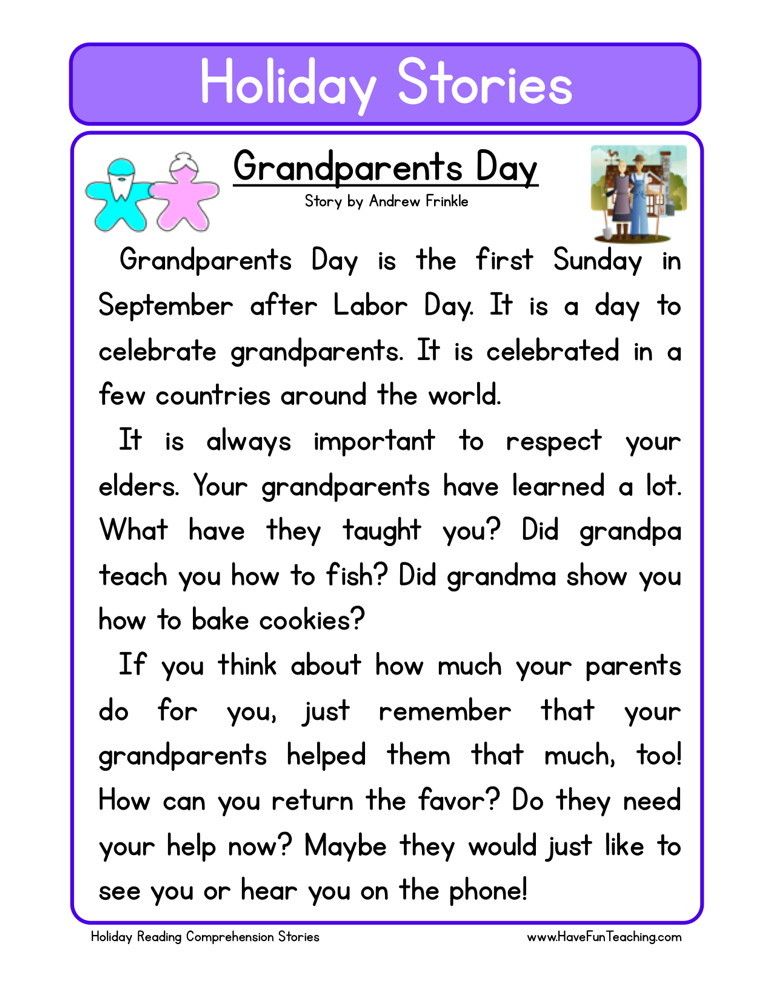

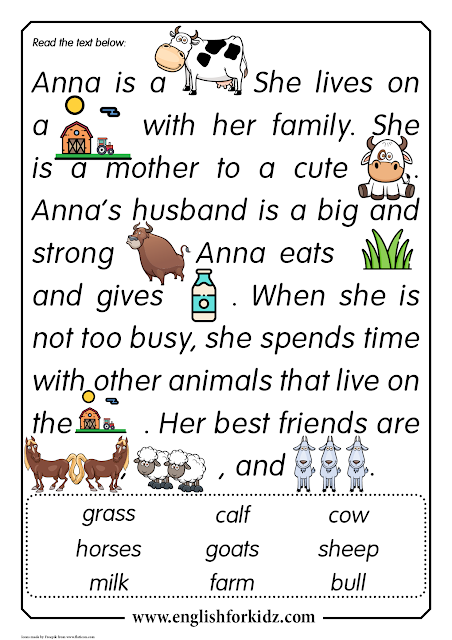

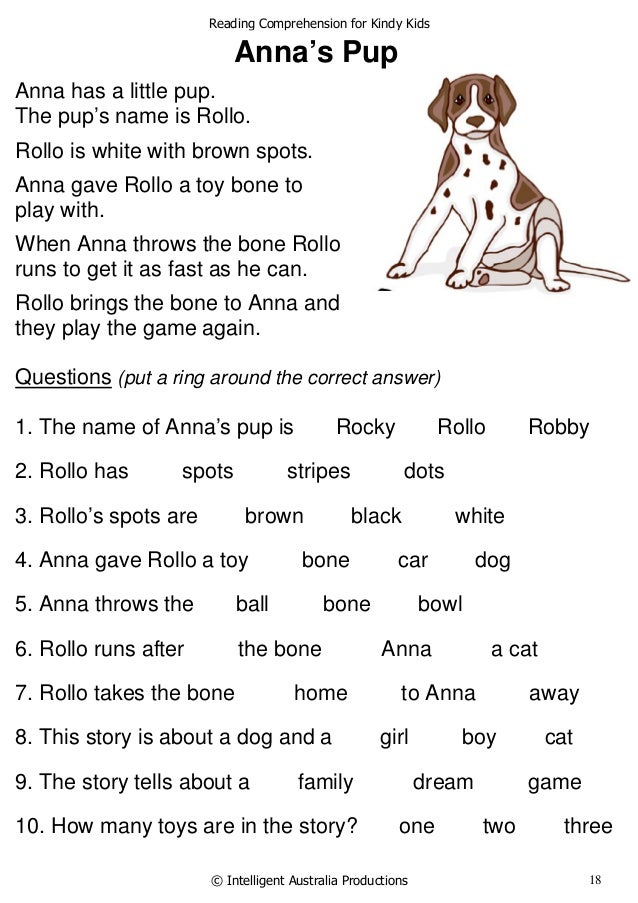

This book is the start of the Easy Stories series of English reading books and is intended for elementary school students. It consists of ten stories of an educational and developmental nature, teaches children to be kind and sympathetic.

The stories are provided with colorful illustrations to help you understand the meaning of new words.

All texts are written in the present tense (The Present Simple Tense) and are accompanied by lexical and grammatical exercises for mastering the material.

The book contains a brief grammar guide, which includes all the grammatical material of the stories, as well as a dictionary of all the words found in the stories.

The book can be used in the classroom in addition to any elementary school English textbook, as well as in extracurricular activities and for additional classes.

Buy with this product

-

Anna Taylor / Anna Taylor Book for reading 2.

Simple stories / Easy Stories. Tutorial. English

Simple stories / Easy Stories. Tutorial. English Anna Taylor / Anna Taylor Book for reading 2. Simple stories / Easy Stories. Tutorial. English

This book continues the Easy Stories series of English reading books and is intended for elementary school students. It consists of ten stories of an educational and developmental nature, teaches children to be kind and sympathetic. The book contains: • short stories written in The Present Simple Tense and The Past Simple Tense; • exercises for practicing lexical and grammatical language...

$368.00

-

Kostyuk E. V. et al. Reading book for grade 2. Read up!/READ UP! Tutorial. English

Kostyuk E. V. et al. Reading book for grade 2. Read up!/READ UP! Tutorial. English

This manual is a book to read in English classes in the second grade of a comprehensive school.

This guide is the start of the Read up! for grades 2-11 and is recommended for use with any English course. In the second grade (the first year of learning English), the foundations of the technique of reading aloud are laid, so the manual includes a large ...

This guide is the start of the Read up! for grades 2-11 and is recommended for use with any English course. In the second grade (the first year of learning English), the foundations of the technique of reading aloud are laid, so the manual includes a large ... $565.00

-

Kostyuk E. V. et al. Reading book for grade 3. Read up!/READ UP! Tutorial. English

Kostyuk E. V. et al. Reading book for grade 3. Read up!/READ UP! Tutorial. English

This Grade 3 Reader continues the 2nd to 11th grade reading series and is recommended for use with any English course. In the third grade, the improvement of the technique of reading aloud and to oneself continues, and work is also being done on reading as a communicative skill. The manual contributes to the formation of information literacy of students and is aimed at acquiring primary ...

$565.

00

00 -

Kostyuk E. V. et al. Reading book for grade 4. Read up!/READ UP! Tutorial. English

Kostyuk E. V. et al. Reading book for grade 4. Read up!/READ UP! Tutorial. English

This 4th Grade Reader continues the 2nd to 11th grade reading series and is recommended for use with any English course. In the fourth grade, the improvement of the technique of reading aloud and to oneself continues, and work is also being done on reading as a communicative skill. The manual contributes to the formation of information literacy of students and is aimed at acquiring the first ...

$565.00

Reviews

-

Alexey

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

December 28, 2022

Excellent help.

-

The user chose to hide his data

Reviewed by: Ozon

December 8, 2022

An excellent book to read in English, I bought a house for a variety of lessons.

assignments. Children read, do exercises for the text and learn to retell in English!

assignments. Children read, do exercises for the text and learn to retell in English!

-

The user chose to hide their data

Reviewed by: Ozon

December 7, 2022

Pros: good trainer

Cons: no

Comment: an excellent simulator, a child of 5 years old, is engaged in this simulator. everything suits

-

Ekaterina

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

November 15, 2022

Very good book, arrived quickly. Thanks

-

Victoria

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

July 27, 2022

Simple, understandable stories. Good strengthening exercises.

-

Alexandra

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

July 27, 2022

A well-written, well-written book.

Suitable for those who want the child not to be bored in the summer, and for those who are actively engaged in reading during the year. All stories in Present Simple (states and actions). Thanks to the author!

Suitable for those who want the child not to be bored in the summer, and for those who are actively engaged in reading during the year. All stories in Present Simple (states and actions). Thanks to the author!

-

Svetlana K.

Reviewed by: Ozon

June 14, 2022

Pros: Great for extra reading or summer activities. Beautiful illustrations, interesting stories, you can study with pleasure.

Weaknesses: No

-

Anastasia

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

May 31, 2022

Great help! A4 format, large font, bright pictures that do not distract from reading, because are on a different page. Exercises are aimed at developing different skills. The dictionary contains all the necessary vocabulary. At the end of the book! There is a grammar guide for all the necessary topics.

-

Natalia

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

April 27, 2022

The book is wonderful! It is easy to read and translate and the child completes the tasks with pleasure. The vocabulary of English words is replenished!!!

-

Natalia

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

April 27, 2022

This manual is just a godsend, the child is engaged with pleasure.

-

Victoria

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

April 27, 2022

The high rating is justified, a very cool book, the child just learned to read (6l), mastered the book, the tasks are interesting. We read the first story with pleasure, we will move on. I definitely recommend buying

-

Gulnaz

Reviewed at: WILDBERRIES

April 27, 2022

We liked the book very much.

Large letters, beautiful pictures, there are tasks for the text. The child of eight years old and the level of English A1 + really liked it. Quite capable.

Large letters, beautiful pictures, there are tasks for the text. The child of eight years old and the level of English A1 + really liked it. Quite capable.

-

Ulan

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

December 7, 2021

A wonderful book - the stories are written in an accessible language, that is, understandable for children! The son reads by himself, then retells to me, then completes tasks according to the text! Recommended for kids in 3rd grade and up!

-

Natella

Reviewed by: WILDBERRIES

December 7, 2021

Excellent book) tasks and text, and pictures develop a guess.

-

Damira

Reviewed at: WILDBERRIES

December 7, 2021

I really liked the book, the content is accessible to the child, the exercises are based on the text.

Learn more

/pic4314753.jpg)