Social emotional learning benefits

Why Social and Emotional Learning Is Essential for Students

Editor's note: This piece is co-authored by Roger Weissberg, Joseph A. Durlak, Celene E. Domitrovich, and Thomas P. Gullotta, and adapted from Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice, now available from Guilford Press.

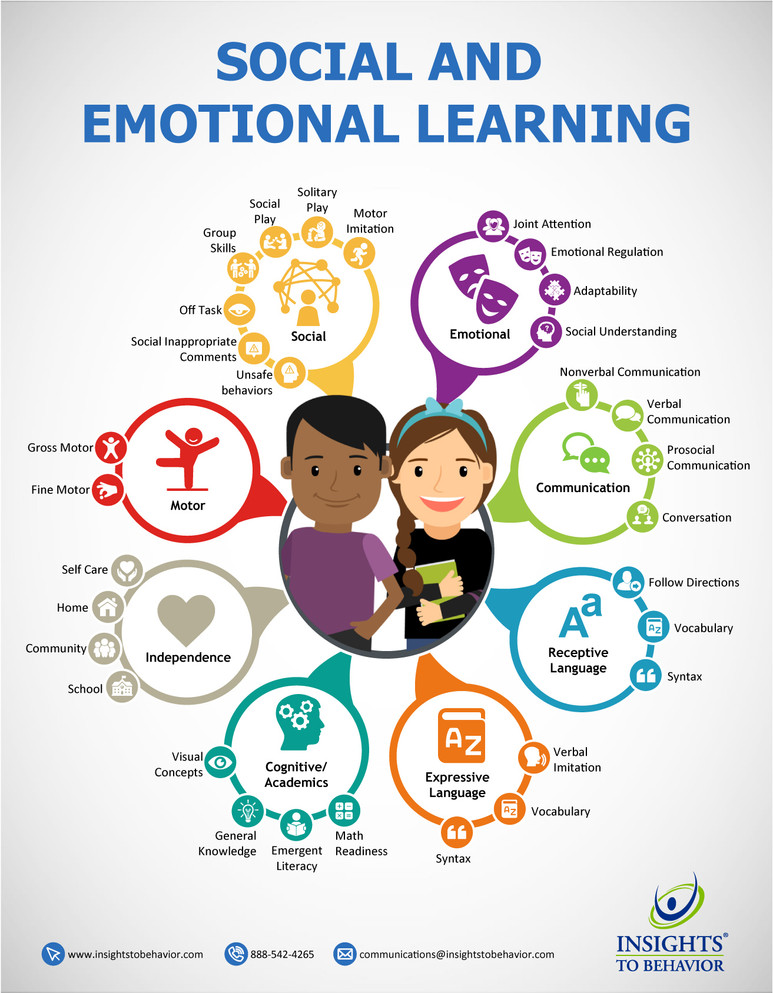

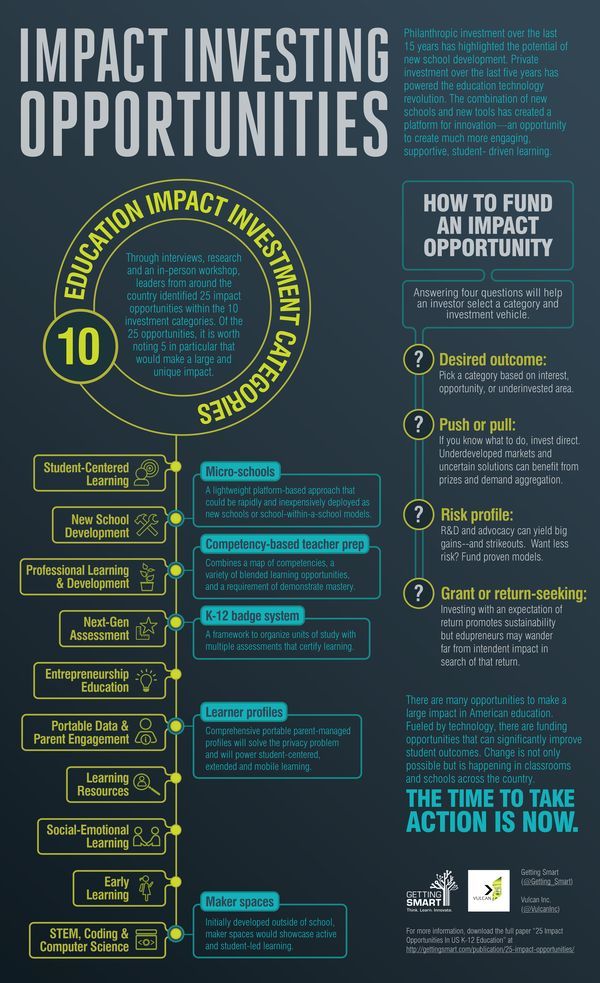

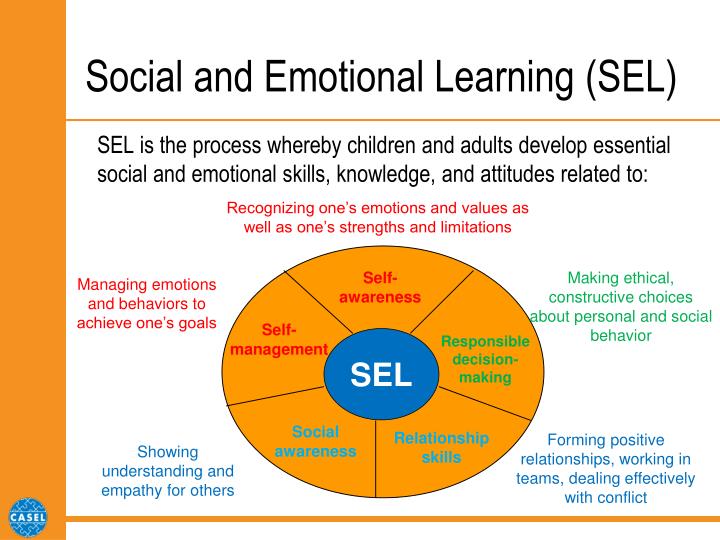

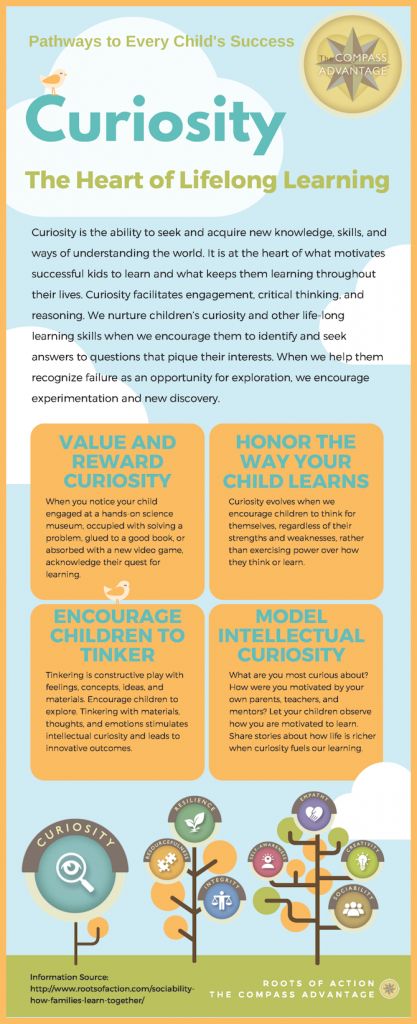

Today's schools are increasingly multicultural and multilingual with students from diverse social and economic backgrounds. Educators and community agencies serve students with different motivation for engaging in learning, behaving positively, and performing academically. Social and emotional learning (SEL) provides a foundation for safe and positive learning, and enhances students' ability to succeed in school, careers, and life.

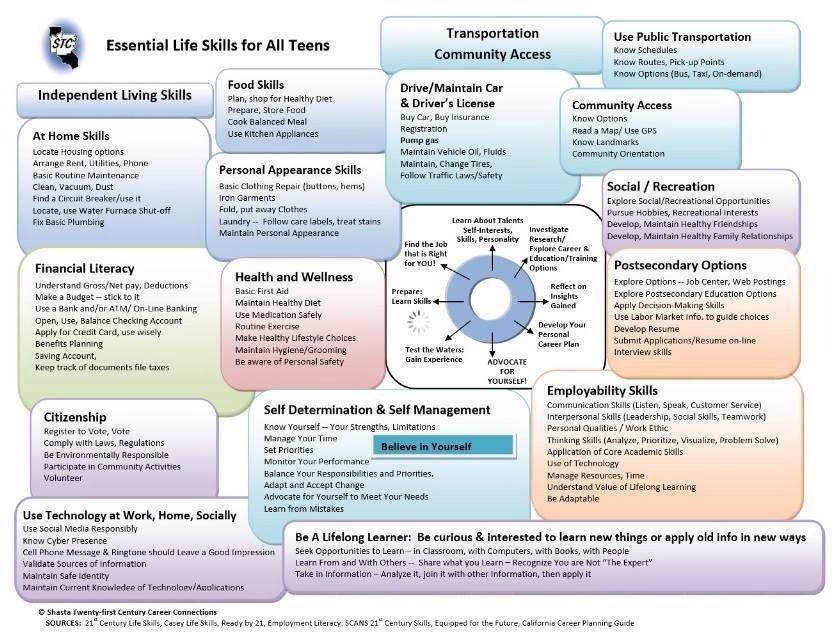

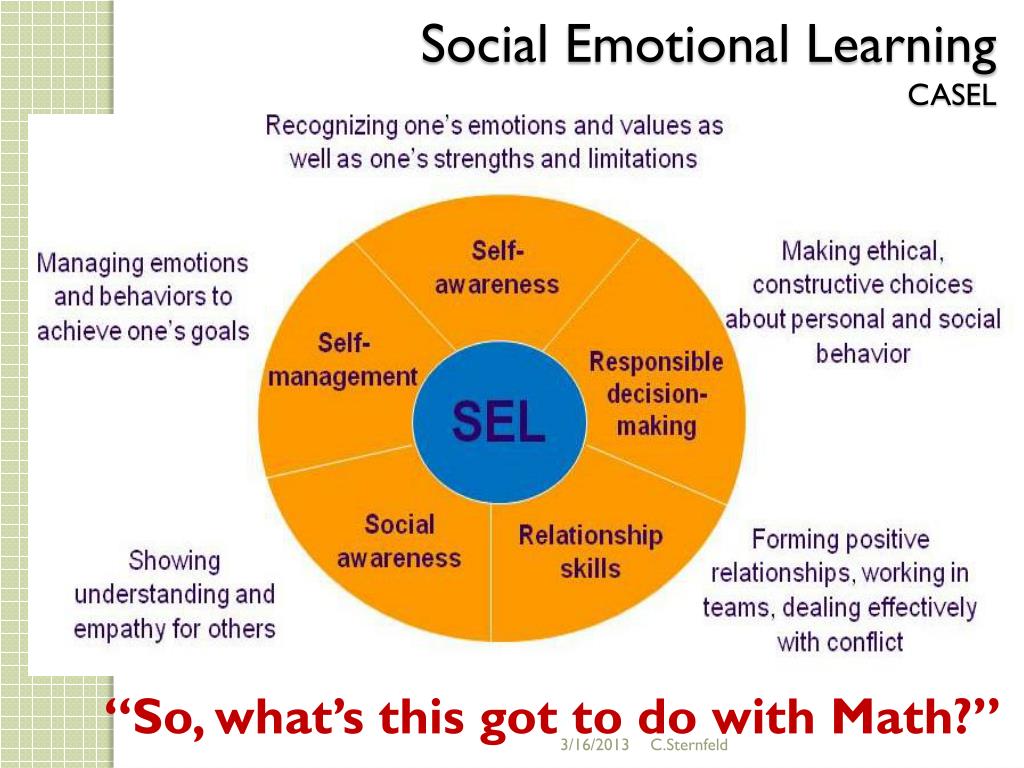

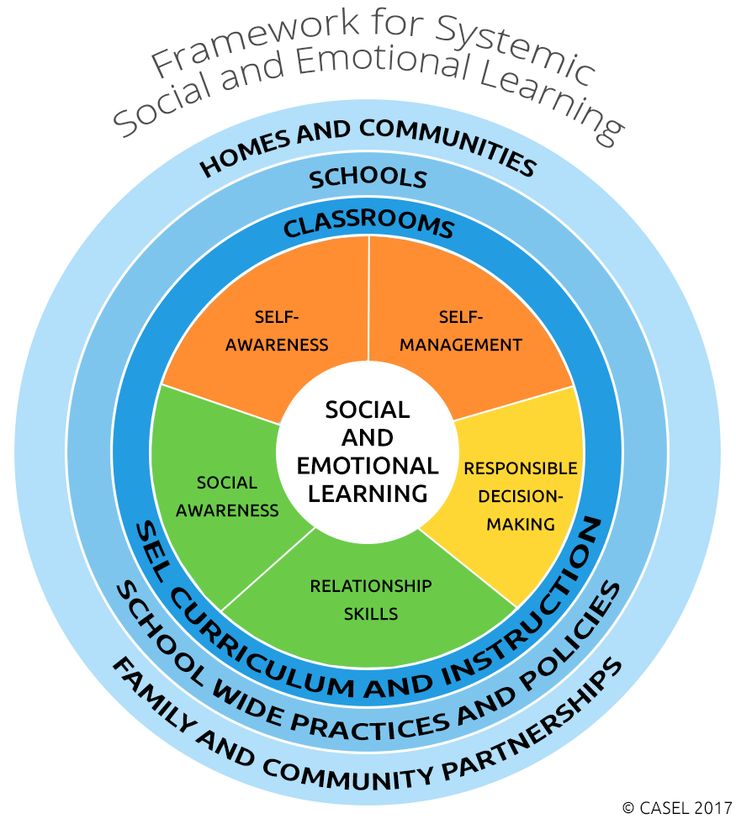

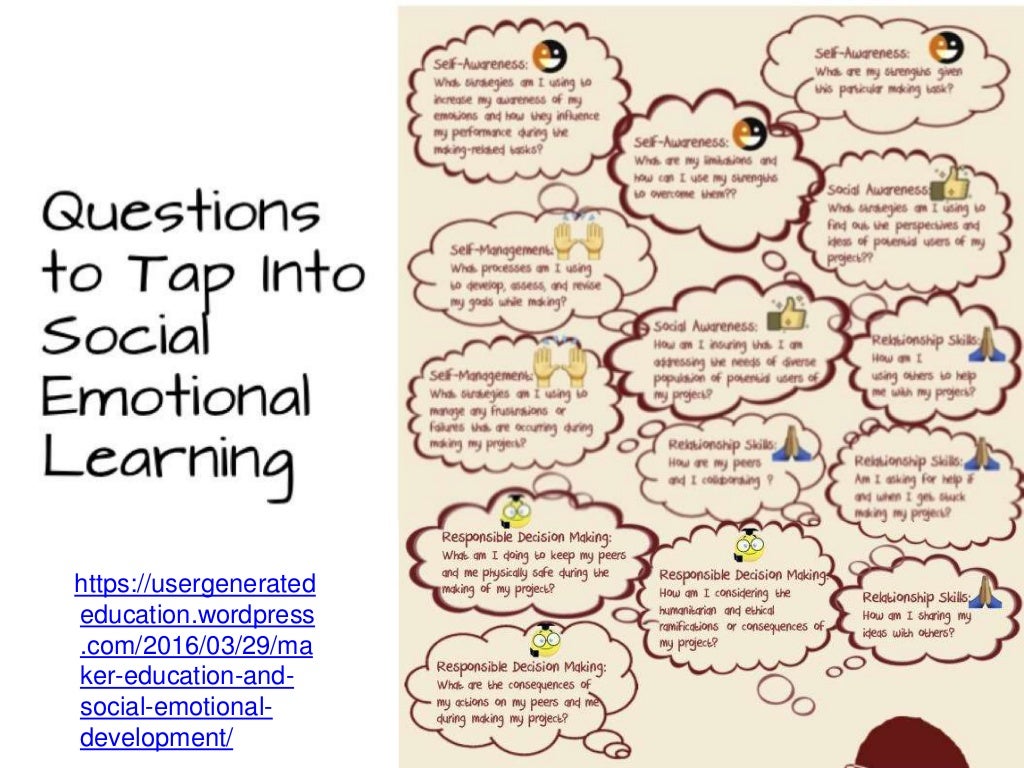

5 Keys to Successful SEL

Image credit: http://secondaryguide.casel.org/casel-secondary-guide.pdf (click image to enlarge)

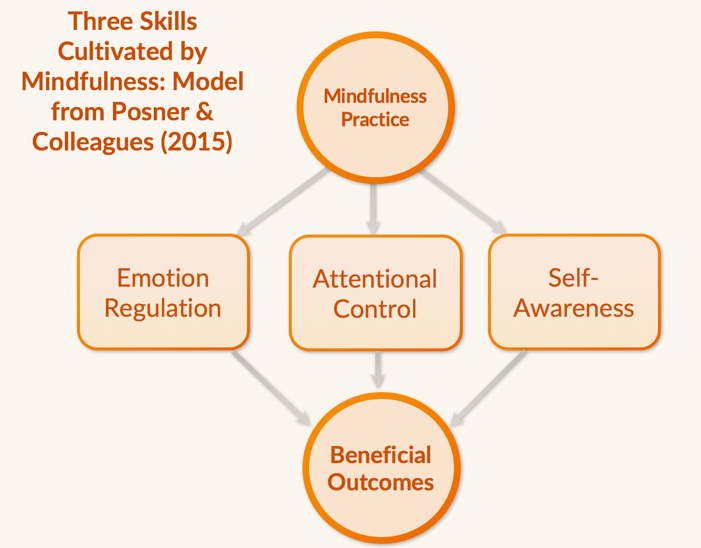

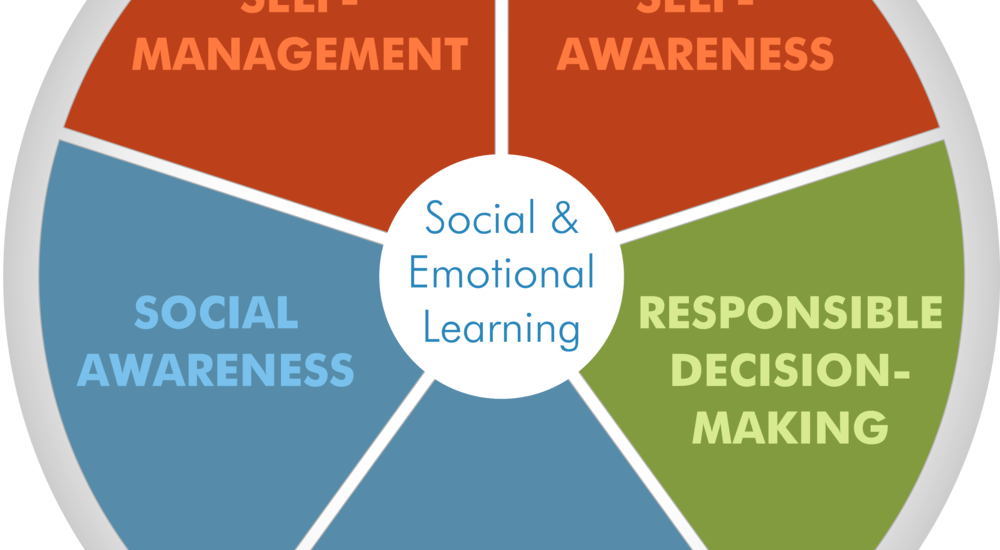

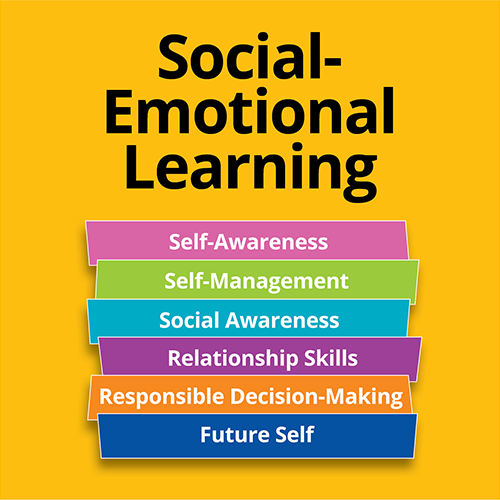

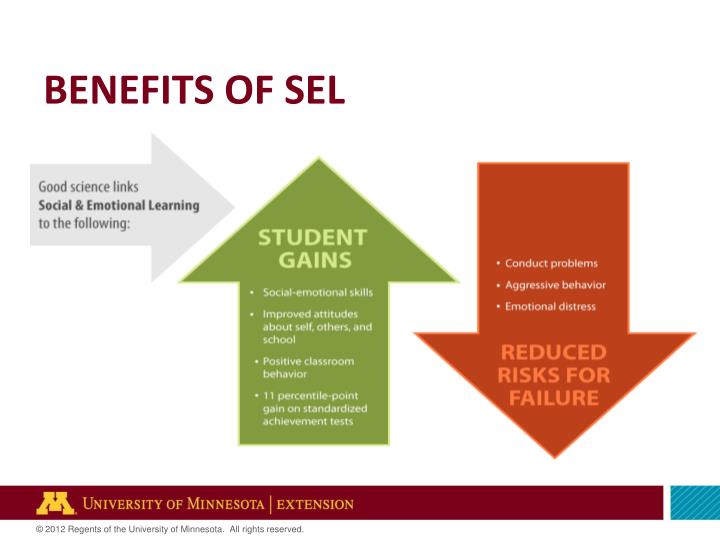

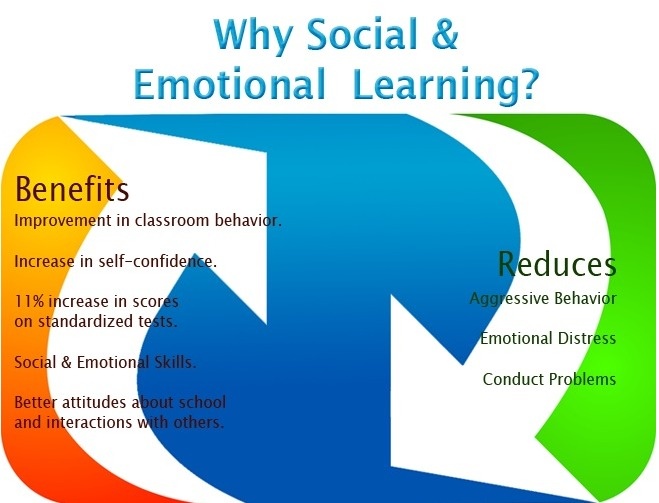

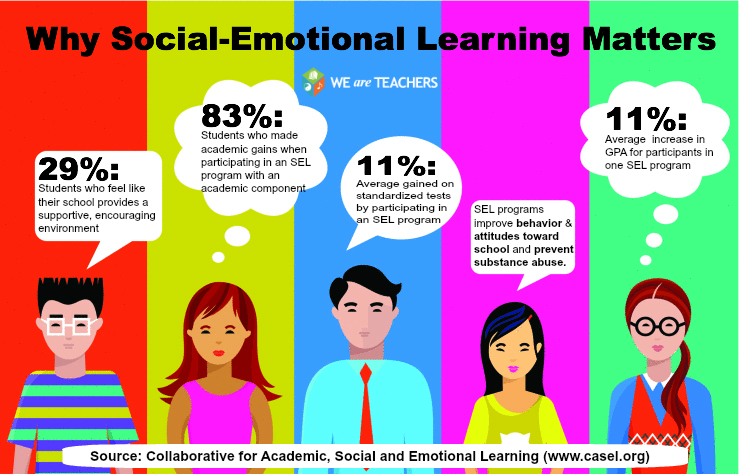

Research shows that SEL not only improves achievement by an average of 11 percentile points, but it also increases prosocial behaviors (such as kindness, sharing, and empathy), improves student attitudes toward school, and reduces depression and stress among students (Durlak et al. , 2011). Effective social and emotional learning programming involves coordinated classroom, schoolwide, family, and community practices that help students develop the following five key skills:

Self-Awareness

Self-awareness involves understanding one's own emotions, personal goals, and values. This includes accurately assessing one's strengths and limitations, having positive mindsets, and possessing a well-grounded sense of self-efficacy and optimism. High levels of self-awareness require the ability to recognize how thoughts, feelings, and actions are interconnected.

Self-Management

Self-management requires skills and attitudes that facilitate the ability to regulate one's own emotions and behaviors. This includes the ability to delay gratification, manage stress, control impulses, and persevere through challenges in order to achieve personal and educational goals.

Social Awareness

Social awareness involves the ability to understand, empathize, and feel compassion for those with different backgrounds or cultures. It also involves understanding social norms for behavior and recognizing family, school, and community resources and supports.

It also involves understanding social norms for behavior and recognizing family, school, and community resources and supports.

Relationship Skills

Relationship skills help students establish and maintain healthy and rewarding relationships, and to act in accordance with social norms. These skills involve communicating clearly, listening actively, cooperating, resisting inappropriate social pressure, negotiating conflict constructively, and seeking help when it is needed.

Responsible Decision Making

Responsible decision making involves learning how to make constructive choices about personal behavior and social interactions across diverse settings. It requires the ability to consider ethical standards, safety concerns, accurate behavioral norms for risky behaviors, the health and well-being of self and others, and to make realistic evaluation of various actions' consequences.

School is one of the primary places where students learn social and emotional skills. An effective SEL program should incorporate four elements represented by the acronym SAFE (Durlak et al., 2010, 2011):

An effective SEL program should incorporate four elements represented by the acronym SAFE (Durlak et al., 2010, 2011):

- Sequenced: connected and coordinated sets of activities to foster skills development

- Active: active forms of learning to help students master new skills

- Focused: emphasis on developing personal and social skills

- Explicit: targeting specific social and emotional skills

The Short- and Long-Term Benefits of SEL

Students are more successful in school and daily life when they:

- Know and can manage themselves

- Understand the perspectives of others and relate effectively with them

- Make sound choices about personal and social decisions

These social and emotional skills are some of several short-term student outcomes that SEL programs promote (Durlak et al., 2011; Farrington et al., 2012; Sklad et al., 2012). Other benefits include:

- More positive attitudes toward oneself, others, and tasks including enhanced self-efficacy, confidence, persistence, empathy, connection and commitment to school, and a sense of purpose

- More positive social behaviors and relationships with peers and adults

- Reduced conduct problems and risk-taking behavior

- Decreased emotional distress

- Improved test scores, grades, and attendance

In the long run, greater social and emotional competence can increase the likelihood of high school graduation, readiness for postsecondary education, career success, positive family and work relationships, better mental health, reduced criminal behavior, and engaged citizenship (e. g., Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill, & Abbott, 2008; Jones, Greenberg, & Crowley, 2015).

g., Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill, & Abbott, 2008; Jones, Greenberg, & Crowley, 2015).

Building SEL Skills in the Classroom

Promoting social and emotional development for all students in classrooms involves teaching and modeling social and emotional skills, providing opportunities for students to practice and hone those skills, and giving students an opportunity to apply these skills in various situations.

One of the most prevalent SEL approaches involves training teachers to deliver explicit lessons that teach social and emotional skills, then finding opportunities for students to reinforce their use throughout the day. Another curricular approach embeds SEL instruction into content areas such as English language arts, social studies, or math (Jones & Bouffard, 2012; Merrell & Gueldner, 2010; Yoder, 2013; Zins et al., 2004). There are a number of research-based SEL programs that enhance students' competence and behavior in developmentally appropriate ways from preschool through high school (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2013, 2015).

Teachers can also naturally foster skills in students through their interpersonal and student-centered instructional interactions throughout the school day. Adult-student interactions support SEL when they result in positive student-teacher relationships, enable teachers to model social-emotional competencies for students, and promote student engagement (Williford & Sanger Wolcott, 2015). Teacher practices that provide students with emotional support and create opportunities for students' voice, autonomy, and mastery experiences promote student engagement in the educational process.

How Schools Can Support SEL

At the school level, SEL strategies typically come in the form of policies, practices, or structures related to climate and student support services (Meyers et al., in press). Safe and positive school climates and cultures positively affect academic, behavioral, and mental health outcomes for students (Thapa, Cohen, Guffey, & Higgins-D'Alessandro, 2013). School leaders play a critical role in fostering schoolwide activities and policies that promote positive school environments, such as establishing a team to address the building climate; adult modeling of social and emotional competence; and developing clear norms, values, and expectations for students and staff members.

School leaders play a critical role in fostering schoolwide activities and policies that promote positive school environments, such as establishing a team to address the building climate; adult modeling of social and emotional competence; and developing clear norms, values, and expectations for students and staff members.

Fair and equitable discipline policies and bullying prevention practices are more effective than purely behavioral methods that rely on reward or punishment (Bear et al., 2015). School leaders can organize activities that build positive relationships and a sense of community among students through structures such as regularly scheduled morning meetings or advisories that provide students with opportunities to connect with each other.

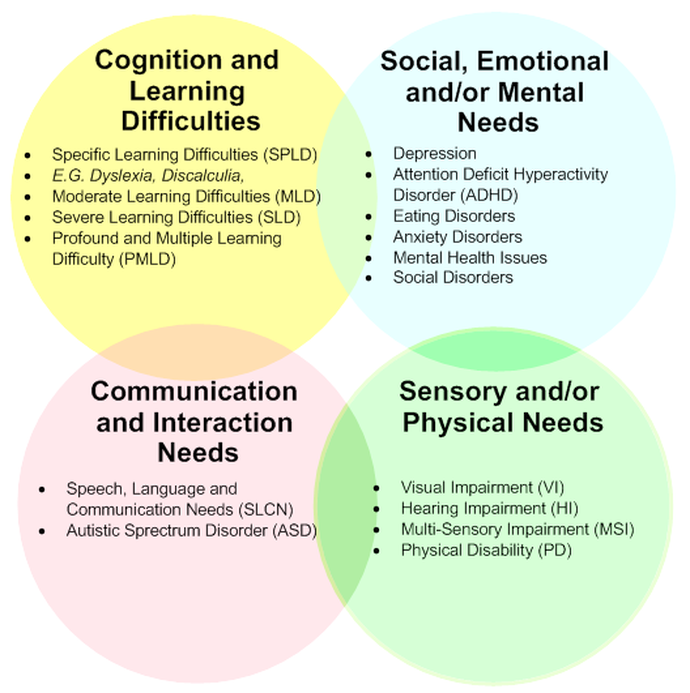

An important component of schoolwide SEL involves integration into multi-tiered systems of support. The services provided to students by professionals such as counselors, social workers, and psychologists should align with universal efforts in the classroom and building. Often through small-group work, student support professionals reinforce and supplement classroom-based instruction for students who need early intervention or more intensive treatment.

Often through small-group work, student support professionals reinforce and supplement classroom-based instruction for students who need early intervention or more intensive treatment.

Building Family and Community Partnerships

Family and community partnerships can strengthen the impact of school approaches to extending learning into the home and neighborhood. Community members and organizations can support classroom and school efforts, especially by providing students with additional opportunities to refine and apply various SEL skills (Catalano et al., 2004).

After-school activities also provide opportunities for students to connect with supportive adults and peers (Gullotta, 2015). They are a great venue to help youth develop and apply new skills and personal talents. Research has shown that after-school programs focused on social and emotional development can significantly enhance student self-perceptions, school connectedness, positive social behaviors, school grades, and achievement test scores, while reducing problem behaviors (Durlak et al. , 2010).

, 2010).

SEL can also be fostered in many settings other than school. SEL begins in early childhood, so family and early childcare settings are important (Bierman & Motamedi, 2015). Higher education settings also have the potential to promote SEL (Conley, 2015).

For more information about the latest advances in SEL research, practice and policy, visit the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning website.

Notes

- Bear, G.G., Whitcomb, S.A., Elias, M.J., & Blank, J.C. (2015). "SEL and Schoolwide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports." In J.A. Durlak, C.E. Domitrovich, R.P. Weissberg, & T.P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning. New York: Guilford Press.

- Bierman, K.L. & Motamedi, M. (2015). "SEL Programs for Preschool Children". In J.A. Durlak, C.E. Domitrovich, R.P. Weissberg, & T.P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning. New York: Guilford Press.

- Catalano, R.F., Berglund, M.L., Ryan, J.A., Lonczak, H.S., & Hawkins, J.D. (2004). "Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), pp.98-124.

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2013). 2013 CASEL Guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs - Preschool and elementary school edition. Chicago, IL: Author.

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2015). 2015 CASEL Guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs - Middle and high school edition. Chicago, IL: Author.

- Conley, C.S. (2015). "SEL in Higher Education." In J.A. Durlak, C.E. Domitrovich, R.P. Weissberg, & T.P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning. New York: Guilford Press.

- Durlak, J.A., Weissberg, R.P., Dymnicki, A.

B., Taylor, R.D., & Schellinger, K.B. (2011). "The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions." Child Development, 82, pp.405-432.

B., Taylor, R.D., & Schellinger, K.B. (2011). "The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions." Child Development, 82, pp.405-432. - Durlak, J.A., Weissberg, R.P., & Pachan, M. (2010). "A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents." American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, pp.294-309.

- Farrington, C.A., Roderick, M., Allensworth, E., Nagaoka, J., Keyes, T.S., Johnson, D.W., & Beechum, N.O. (2012). Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners: The Role of Noncognitive Factors in Shaping School Performance: A Critical Literature Review. Consortium on Chicago School Research.

- Gullotta, T.P. (2015). "After-School Programming and SEL." In J.A. Durlak, C.E. Domitrovich, R.P. Weissberg, & T.P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hawkins, J.

D., Kosterman, R., Catalano, R.F., Hill, K.G., & Abbott, R.D. (2008). "Effects of social development intervention in childhood 15 years later." Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(12), pp.1133-1141.

D., Kosterman, R., Catalano, R.F., Hill, K.G., & Abbott, R.D. (2008). "Effects of social development intervention in childhood 15 years later." Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(12), pp.1133-1141. - Jones, D.E., Greenberg, M., & Crowley, M. (2015). "Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness." American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), pp.2283-2290.

- Jones, S.M. & Bouffard, S.M. (2012). "Social and emotional learning in schools: From programs to strategies." Social Policy Report, 26(4), pp.1-33.

- Merrell, K.W. & Gueldner, B.A. (2010). Social and emotional learning in the classroom: Promoting mental health and academic success. New York: Guilford Press.

- Meyers, D., Gil, L., Cross, R., Keister, S., Domitrovich, C.E., & Weissberg, R.P. (in press). CASEL guide for schoolwide social and emotional learning.

Chicago: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

Chicago: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. - Sklad, M., Diekstra, R., Ritter, M.D., Ben, J., & Gravesteijn, C. (2012). "Effectiveness of school-based universal social, emotional, and behavioral programs: Do they enhance students' development in the area of skill, behavior, and adjustment?" Psychology in the Schools, 49(9), pp.892-909.

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Gulley, S., & Higgins-D'Alessandro, A. (2013). "A review of school climate research." Review of Educational Research, 83(3), pp.357-385.

- Williford, A.P. & Wolcott, C.S. (2015). "SEL and Student-Teacher Relationships." In J.A. Durlak, C.E. Domitrovich, R.P. Weissberg, & T.P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning. New York: Guilford Press.

- Yoder, N. (2013). Teaching the whole child: Instructional practices that support social and emotional learning in three teacher evaluation frameworks. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research Center on Great Teachers and Leaders.

- Zins, J.E., Weissberg, R.P., Wang, M.C., & Walberg, H.J. (Eds.). (2004). Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? New York: Teachers College Press.

What is Social Emotional Learning (SEL): Why It Matters

Skip to ContentHome » What is Social Emotional Learning (SEL): Why It Matters

Social Emotional Learning (SEL), what is it, and why does it matter to educators? As an educator, some of the worst things you can hear a student say is, “This is stupid,” or “Why are we learning this?” Think back to when you were in school and the subjects that caused you the most frustration.

You’d likely find some common ground with your students in wishing you were given clear reasons why something was important and how learning a subject or skill would benefit you now, as well as years later. That frustration and finding constructive ways to deal with emotions and interact with one another in respectful ways are just a few of the guiding principles behind social emotional learning, or SEL.

Today, in an ever-diversifying world, the classroom is the place where students are often first exposed to people who hail from a range of different backgrounds, hold differing beliefs, and have unique capabilities. To account for these differences and help put all students on an equal footing to succeed, social and emotional learning (SEL) aims to help students better understand their thoughts and emotions, to become more self-aware, and to develop more empathy for others within their community and the world around them.

Developing these qualities in the classroom can help students become better, more productive, self-aware, and socially-aware citizens outside of the classroom in the years ahead. Learn more about the importance of social emotional learning, as well as its benefits both in and out of the classroom.

Table of contents

- What is Social Emotional Learning (SEL)?

- The Five Social Emotional Learning Competencies

- How Educators Approach SEL

- The Benefits of SEL

- What is Social Emotional Learning Theory?

- Incorporate Social Emotional Learning in the Classroom

- Measuring Social-Emotional Learning Impact

- Why is SEL Important?

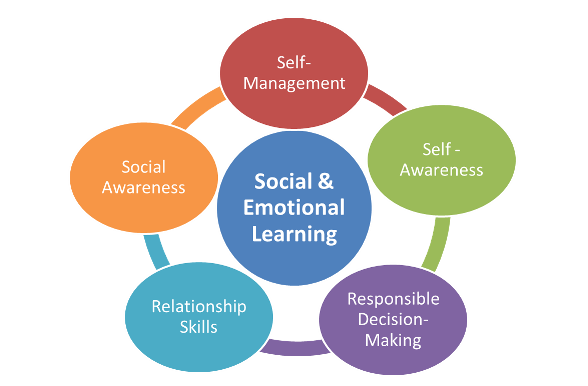

Social emotional learning (SEL) is a methodology that helps students of all ages to better comprehend their emotions, to feel those emotions fully, and demonstrate empathy for others. These learned behaviors are then used to help students make positive, responsible decisions; create frameworks to achieve their goals, and build positive relationships with others

These learned behaviors are then used to help students make positive, responsible decisions; create frameworks to achieve their goals, and build positive relationships with others

According to the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), an organization devoted to students and educators to help achieve positive outcomes for PreK-12 students, SEL involves five core competencies that can be applied in both the classroom, at home, and in students’ communities. These five core competencies are:

Self-awareness

To recognize your emotions and how they impact your behavior; acknowledging your strengths and weaknesses to better gain confidence in your abilities.

Self-management

To take control and ownership of your thoughts, emotions, and actions in various situations, as well as setting and working toward goals.

The ability to put yourself in the shoes of another person who may be from a different background or culture from the one you grew up with. To act with empathy and in an ethical manner within your home, school, and community.

To act with empathy and in an ethical manner within your home, school, and community.

Relationship skills

The ability to build and maintain healthy relationships with people from a diverse range of backgrounds. This competency focuses on listening to and being able to communicate with others, peacefully resolving conflict, and knowing when to ask for or offer help.

Making responsible decisions

Choosing how to act or respond to a situation is based on learned behaviors such as ethics, safety, weighing consequences, and the well-being of others, as well as yourself.

How Educators Approach SEL

While SEL isn’t a designated subject like history or math, it can be woven into the fabric of a school’s curriculum. When educators make academic lessons more personal and relatable to students, students may be more inclined to participate and may be less likely to mentally check out during their subjects. By fostering a sense of empathy, self-awareness, and feelings of safety and inclusiveness in the classroom, SEL can have a positive impact that lasts a lifetime.

There are several different approaches to SEL. Some teachers have a more formally designated portion of the school day devoted to SEL — sometimes taught in homeroom. These lessons become a recurring theme throughout the rest of the school day to help make the core competencies of SEL more real to students.

Teachers may want to have students journal or write about their thoughts and feelings on a particular SEL lesson, or even have younger students partner with an older “buddy classroom” (or vice versa) to help students across different age levels bond or find common ground.

Other teachers work SEL-related lessons into more formal subjects, like math, history, or reading. For instance, examples of SEL-in-action can include assigning a group project where students self-delegate roles to work together for the good of the group, role playing as historical figures to understand the rationale behind a person’s actions, or for students to conduct formal interviews with one another to take a pulse-check on current events.

Teachers can also work with students to set goals in areas where they may need improvement and help chart their progress, giving them a measurable way to show their achievement and feel a sense of accomplishment.

The Benefits of SEL

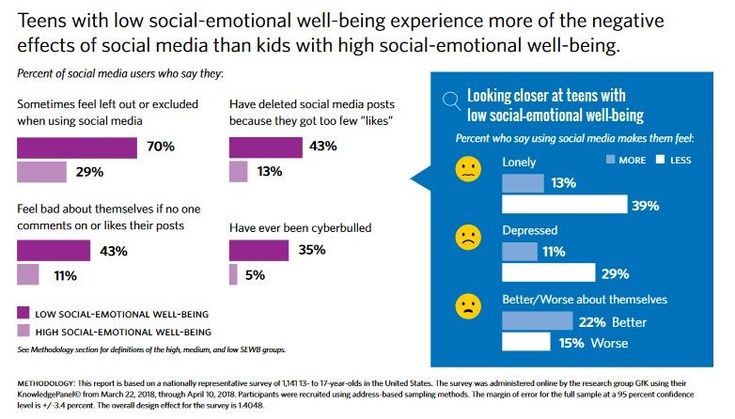

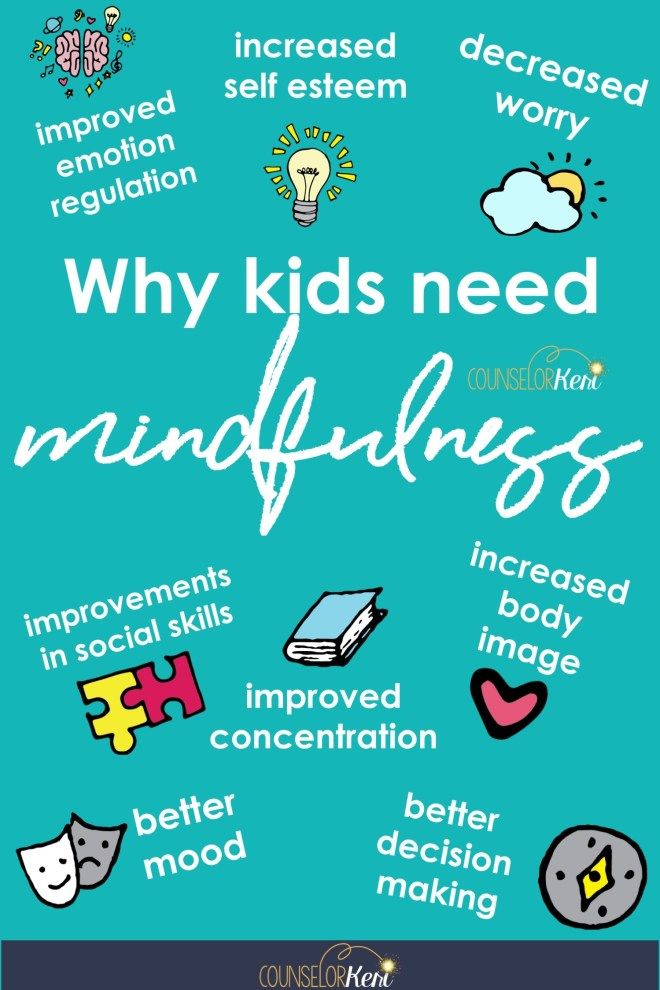

SEL is beneficial to both children and adults, increasing self-awareness, academic achievement, and positive behaviors both in and out of the classroom. From an academic standpoint, students who participated in SEL programs saw an 11 percentile increase in their overall grades and better attendance. On a more individual level, the skills learned within an SEL program have been shown to help students better cope with emotional stress, solve problems, and avoid peer pressure to engage in harmful activities.

Students who are equipped to deal with problems that affect them on a personal level are then better able to navigate the pressures of adult life. A report by the AEI/Brookings Working Group on Poverty and Opportunity noted that, “despite their importance to education, employment, and family life, the major educational and social reforms of the K-12 system over the last few decades have not focused sufficiently on the socio-emotional factors that are crucial to learning. ”

”

A study published by the American Journal of Public Health used data from the longitudinal, nonintervention subsample of the Fast Track Project, an intervention program designed to reduce aggression in children identified as at high risk for long-term behavioral problems and conduct disorders.

When educators are able to see which students do not grasp the core pillars of SEL, they can better work with them at an early age and help these students develop better self-control, empathy, and other positive qualities. Learning positive behaviors that extend beyond a purely academic level of achievement can help these students develop the “soft skills” required of many jobs, such as teamwork, and ability to understand others, and problem-solving. This can help set these students up for success throughout their school years and beyond.

Broadly speaking, social and emotional learning (SEL) refers to the process through which individuals learn and apply a set of social, emotional, and related skills, attitudes, behaviors, and values that help direct students. This includes thoughts, feelings, and actions in ways that enable them to succeed in school. However, SEL has been defined in a variety of ways (Humphrey et al., 2011).

This includes thoughts, feelings, and actions in ways that enable them to succeed in school. However, SEL has been defined in a variety of ways (Humphrey et al., 2011).

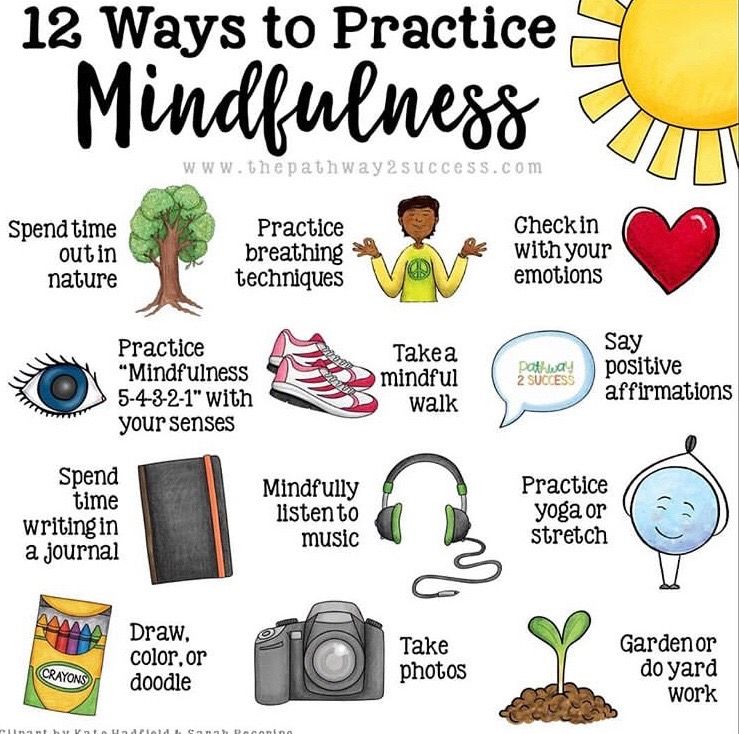

There are many ways to incorporate SEL in the classroom. The main idea is to provide an ongoing SEL influence throughout the day. In the beginning, you could start by checking in with students to see how they feel. Another great way is to provide students the opportunity to see how a tricky or troubling situation is being handled. This will give them some ideas on how to handle a tricky situation they may encounter. Utilizing students to role-play in front of the class would be a viable example. Make sure there is a place for students to calm down. This safe space will allow for the student to reflect.

Measuring the impact of implementing SEL inside the classroom goes way beyond just grades. As Dr. Christina Cipriano explains, “When students are struggling and school performance is poor, they are more likely to find school and learning as a source of anxiety, manifesting in diminished self-efficacy, motivation, engagement, and connectedness with school. ”

”

As a student is provided the tools associated with SEL, they will have more ownership of their actions, a sense of belonging, and will intrinsically care about their education. A student that has had consistent exposure to SEL is able to manage stress better and reduces the chance for that child to become depressed.

Why is SEL Important?

While SEL has been more formally stood up as a program in preschools throughout all 50 states, very few states have made SEL a designated part of school curriculum at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. To date, only three states have a fully-designed set of standards for SEL programs with benchmarks for students at every grade level from K-12, according to the AEI/Brookings report. These states are Illinois, Kansas, and Pennsylvania.

Because so few states have made SEL a part of their curriculum for K-12 students, statistical evidence showing the benefits of SEL has been anecdotal. However, preschool-age children who were able to participate in an SEL program and learned these principles early on in their school career were able to reap the intended benefits. As more states and schools consider weaving SEL into their curriculum, it can provide educators with more statistically significant evidence of the program’s positive impact.

As more states and schools consider weaving SEL into their curriculum, it can provide educators with more statistically significant evidence of the program’s positive impact.

Ready to Take the Next Step?

Becoming a teacher can be a rewarding experience that helps a new generation reach new heights and their full potential. If you’ve considered becoming a teacher, visit our program page to learn how National University’s Sanford College of Education can help you achieve your goal. Learn more about our on-campus and online degrees and programs. You can also hear more from our students and faculty.

Back to All Blog

Learn More About Our University and Scholarships

Join our email list!

Recent Resources

Your passion. Our Programs.

Choose an Area of Study

Teaching & Education Business & Marketing Healthcare & Nursing Social Sciences & Psychology Engineering & Technology Criminal Justice & Law Arts & Humanities Science & Math

Your passion.

Our Programs.

Our Programs.Select a degree level

View ProgramsSearch the site

Modal window with site-search and helpful links

Terms & Conditions

By submitting your information to National University as my electronic signature and submitting this form by clicking the Request Info button above, I provide my express written consent to representatives of National University and National University System affiliates (City University of Seattle and Northcentral University) to contact me about educational opportunities, and to send phone calls, and/or SMS/Text Messages – using automated technology, including automatic dialing system and pre-recorded and artificial voice messages – to the phone numbers (including cellular) and e-mail address(es) I have provided. I confirm that the information provided on this form is accurate and complete. I also understand that certain degree programs may not be available in all states. Message and data rates may apply.

I understand that consent is not a condition to purchase any goods, services or property, and that I may withdraw my consent at any time by sending an email to [email protected] I understand that if I am submitting my personal data from outside of the United States, I am consenting to the transfer of my personal data to, and its storage in, the United States, and I understand that my personal data will be subject to processing in accordance with U.S. laws, unless stated otherwise in our privacy policy. Please review our privacy policy for more details or contact us at [email protected].

By submitting my information, I acknowledge that I have read and reviewed the Accessibility Statement.

By submitting my information, I acknowledge that I have read and reviewed the Student Code of Conduct located in the Catalog.

How social and emotional skills can fit into the educational program About income 0 Comments educational process, social intelligence, emotional intelligence

Emotional and social intelligence are important components of our children's success in the future. In their article "How Social-Emotional Skills Can Fit into School Curricula," the staff at UC Berkeley talk about how you can incorporate these elements into your curriculum. Initially, the recommendations are intended for the general education system, but teachers can easily adapt them to work on additional general developmental programs. nine0014

In their article "How Social-Emotional Skills Can Fit into School Curricula," the staff at UC Berkeley talk about how you can incorporate these elements into your curriculum. Initially, the recommendations are intended for the general education system, but teachers can easily adapt them to work on additional general developmental programs. nine0014

Material represents a translation of article "How Social-Emotional Skills Can Fit into School Curricula". Source.

Prepared by:

Vicki Zakrzewski ,

Ph . D .,

director of educational activities

at Greater Good Science Center ( GGSC )

at UC Berkeley

.

"No time at all!" - Over and over, teachers tell me that this is why they can't teach their students social-emotional skills - and this is not surprising, given the demands placed on them.

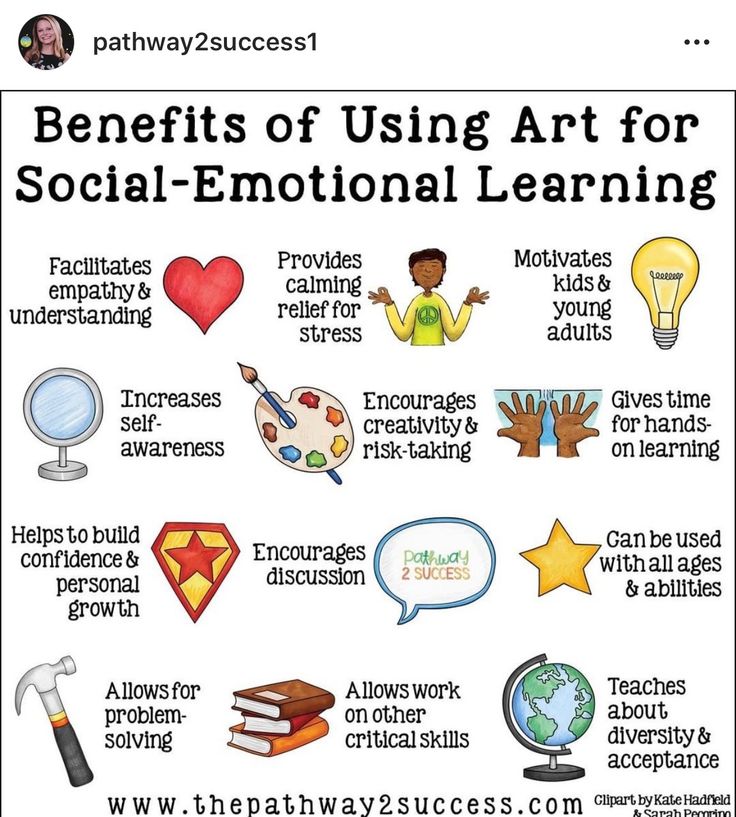

While a 30-minute social-emotional learning (SEL) lesson is difficult to fit into a school week, elements of the social-emotional concept are often already present in the existing curriculum. In one study, teachers paired with aspiring school psychologists to create art-oriented classes with elements of SEL. The researchers found that the result was "creative and powerful" lessons that contributed to the desire of both groups to continue such cooperation. nine0011

We decided to try something similar at the GGSC Summer Institute for Educators and were amazed by the results. Most curricula in schools can offer lessons on social, emotional or moral issues if educators are willing to do so.

How to Integrate SEL into Curriculum Content

Schools that want to teach social-emotional learning but find themselves locked into a rigid curriculum can instead take the social, emotional, and moral aspects of the material that students are currently learning . For example, many topics, books, people, and concepts in curricula are related to:

For example, many topics, books, people, and concepts in curricula are related to:

- emotional life of a person;

- ethical dilemmas;

- situations requiring compassion;

- social problems;

- ethical use of knowledge;

- interaction between groups;

- implicit personality theory.

As one of our math teachers pointed out, it is not difficult to introduce the topic of group resource allocation in this way. For example, when the guys are working on a problem where it is necessary to distribute, say, pieces of the whole, you can introduce an ethical problem and ask: how can you divide the pie, knowing who was the hungriest? is an unusual introduction to the idea of justice. nine0011

In addition, a simple process of preparing for specific lessons may allow one to see how to deal with social, emotional or moral issues. When designing a lesson, educators may want to consider the following:

- Does the lesson include difficult conversations that can lead to a clash of values?

- Should students work in pairs or groups?

- Will there be tasks in which students will have to pay attention to their emotions or demonstrate attention and perseverance? nine0091

- Do they need to show self-confidence, for example, during oral presentations, or set long-term goals, or make ethical choices?

By integrating SEL into curriculum content, educators not only give students the opportunity to practice their social-emotional skills, but also show them how integral these skills are in our daily lives.

Three Lesson Plans

After three days of our Summer Institute, during which participants were introduced to the fundamental base and practical experience in the field of social, emotional and moral development, we asked them to create a lesson in which they would integrate social or emotional skills, mindfulness practice, and/or moral dilemma. Once given a challenge, the participants came up with some great examples in a creative collaboration mode, some of which we are happy to present below. nine0011

Elementary School

To teach young children cognitive rethinking or the ability to view situations in a more positive way, our educators suggested using the classic book Alexander and the Terrible, Terrible, No Good, Very Bad Day ( ed. . - a famous children's book and the film of the same name ).

The lesson begins with a moment designed to calm and focus the students so that they can think carefully and remember if they have ever had a bad day. Then, after the book is read aloud to the class, the children make a list of the problems Alexander faced and describe how they would feel if they faced each of these problems. For example, when Alexander thinks that his teacher likes a picture of his friend with a sailboat more than his drawing of an invisible castle, students think about what emotions Alexander might be experiencing. nine0011

Then, after the book is read aloud to the class, the children make a list of the problems Alexander faced and describe how they would feel if they faced each of these problems. For example, when Alexander thinks that his teacher likes a picture of his friend with a sailboat more than his drawing of an invisible castle, students think about what emotions Alexander might be experiencing. nine0011

The learners then choose two or three problems from the list and discuss how Alexander can change his response to these incidents to make him feel better. In the example above, Alexander could: think of a time when the teacher really liked his painting; be glad that the teacher complimented his friend; draw a castle that the teacher would be able to see.

To end the lesson positively, the children and the teacher create a “book” called “A Pretty Good Day” with pictures and descriptions of some difficult situation that happened to them, but became less painful after they changed their mind about her. nine0011

nine0011

Middle School

High school science teachers hoped that Humpty Dumpty would help establish rules and regulations for laboratory safety at the beginning of the school year. The students were given a handout (straws, styrofoam, cotton balls, aluminum foil and paper) and instructions: students are given one minute to individually design a wall with safety devices to prevent Humpty Dumpty from falling or breaking. After completing this difficult task, they discuss their experience and what they can change to improve safety, cultivating respect for other people's opinions and correct productive group discussion. nine0011

Students then form groups of at least two people and repeat the task, but this time they have three minutes. In the ensuing discussion, the teacher can touch on topics such as problem-solving skills, the impact of current choices on the future, teamwork, and conflict resolution.

The exercise concludes with students trying the task again in specific roles (e. g. project manager, equipment manager, data logger, time keeper. Rev. - performing laboratory work in groups assumes the distribution of roles among students in accordance with the project methodology ), and then reflect on how these roles made the task easier or more difficult.

g. project manager, equipment manager, data logger, time keeper. Rev. - performing laboratory work in groups assumes the distribution of roles among students in accordance with the project methodology ), and then reflect on how these roles made the task easier or more difficult.

Since middle school is the time when students start asking questions about rules, social norms, etc., teachers can extend this lesson by asking their classes thought-provoking questions. For example, why did Humpty Dumpty decide to climb the wall and why was he alone? Where were his friends? Was he allowed to climb the wall or was he breaking the rules? Who made the rules and are they fair? And what about the stability of the wall - whose responsibility is it to make sure the wall is safe? Why wasn't the wall safe for Humpty Dumpty? Finally, did Humpty Dumpty get proper care after he broke down? If not, what can be done to ensure that the future of Humpty Dumpty is taken care of? nine0011

High School

An educational module on health in the United States was developed for high school students using an interdisciplinary approach. In math, students use ratios and graphs to consider the amount of federal money spent on health care per capita. Next, the history looks at the history of health care in the United States in the 18th, 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

In math, students use ratios and graphs to consider the amount of federal money spent on health care per capita. Next, the history looks at the history of health care in the United States in the 18th, 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

Armed with new knowledge and their research findings on the topic, students explore and debate broader ethical issues about health care in the United States. Is healthcare a moral imperative or is it a social convention? In other words, does the government have a moral responsibility to provide health care to each of its citizens, because the lack of health care harms people, or does it provide health care only because it is required by law? Recognizing that these questions can bring out polarizing views, the instructors also included elements of SEL—active listening, open-mindedness, and so on—into classes. nine0011

Looking at the curriculum through a social, emotional and moral lens is a habit of the mind. The more you do it, the easier it becomes. Perhaps the biggest benefit of such lessons is that students will begin to look at their education, their decisions, their interests, and their relationships through this lens, developing a more thoughtful and insightful approach to life.

Perhaps the biggest benefit of such lessons is that students will begin to look at their education, their decisions, their interests, and their relationships through this lens, developing a more thoughtful and insightful approach to life.

Translation prepared by:

I.S. Grigoriev,

Resource Center Methodist

Vorobyovy Gory

Moscow

Benefits and benefits of emotional intelligence, connection between EQ and IQ

Being an excellent student in school, graduating from university, and then reaping the rewards all your life - this scheme is outdated. You have to study all your life. And employers are less and less looking at "crusts" and regalia and are increasingly paying attention to skills that are simple at first glance: the ability to work in a team, get along with others and understand feelings - both one's own and those of others. What to do? How to grab luck by the tail? It's simple: you need to increase emotional intelligence (EI), which, unlike the general one, can be developed at any age. nine0194

nine0194

Listen to the post:

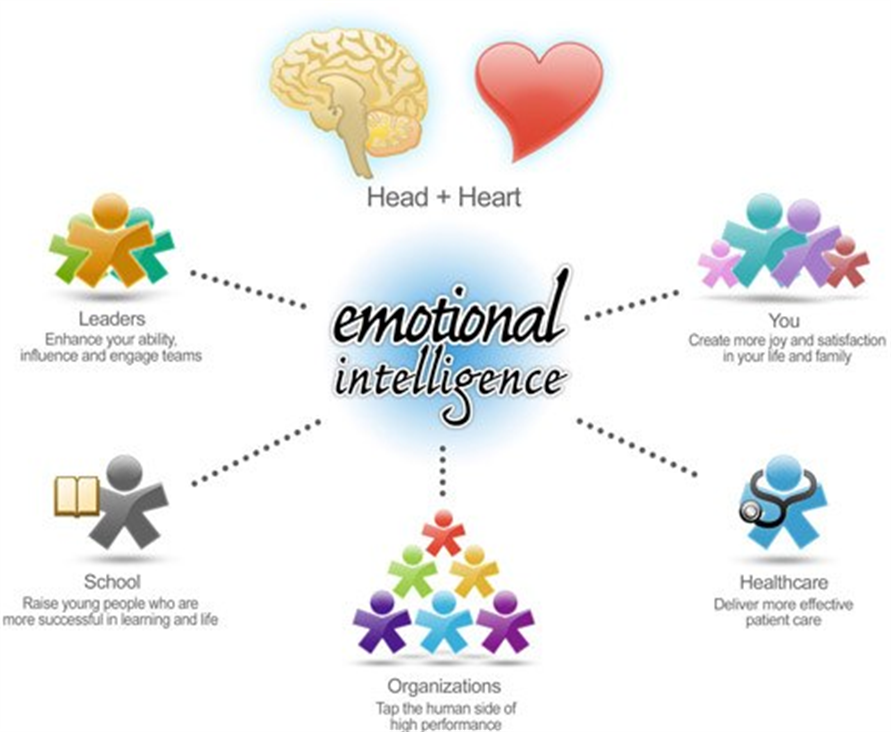

In the first article in the series on emotional intelligence, we talked about what emotional intelligence (EI) is, what it is for and what components it consists of. In this article, we will consider the advantages of people with developed EI, talk about the relationship between emotional intelligence and cognitive abilities and the significance of EI in different areas of life.

Advantages of people with high EI

John Mayer of the University of New Hampshire argues that people with high EI have certain characteristics that they easily turn into competitive advantages:

- Deal effectively with emotional problems.

- More accurately recognize emotions by facial expression and build communication taking into account the emotional state of the interlocutor.

- Realize that certain emotional states are associated with specific kinds of thinking and use this knowledge.

For example, a sad mood encourages analytical thinking, so they can consciously engage in analysis while in that mood. nine0091

For example, a sad mood encourages analytical thinking, so they can consciously engage in analysis while in that mood. nine0091 - Have an idea of the main factors of emotion and imagine what they are associated with: for example, they may understand that angry people are potentially dangerous. Often, the ability to "read" emotions helps to avoid danger or use the situation for the benefit of oneself and others.

- They know how to control their emotions and manage the emotions of others.

- Recognize the social aspect of emotions. For example, people who are happy are more likely to attend social events than those who are sad or fearful. nine0091

- Understand how emotions develop, and can predict the situation.

Danish psychotherapist Ilse Sand believes that the better we understand feelings (especially our own), the easier it is for us to make a decision about how to respond to a particular event. She advises to listen carefully to your feelings. If you cannot determine how you are feeling at the moment, do a brief analysis of the basic feelings (happiness, sadness, fear/anxiety and anger):

She advises to listen carefully to your feelings. If you cannot determine how you are feeling at the moment, do a brief analysis of the basic feelings (happiness, sadness, fear/anxiety and anger):

-

-

- Am I angry about something?

- Something upset me?

- Maybe I'm scared?

- Maybe I am experiencing a subtle happiness?

-

Emotional intelligence and the brain: is there a connection

In the past, it was believed that cognitive and emotional processes exist separately. However, data from a 2014 study by University of Illinois professor of neuroscience Aaron Barbie proves that emotional and psychometric (that is, general) intelligence are regulated by the same nervous system, and therefore involve the integration of cognitive, social, and emotional processes. The aim of Barbie's research was to find the neurobiological basis of EI, they involved 152 subjects with focal brain damage. nine0011

nine0011

Research has found that many areas of the brain are important for both general intelligence and emotional intelligence. In a series of tests, the researchers measured the performance of subjects in the following areas:

- EI was studied using the MSCEIT test of Mayer, Salovey and Caruso - we will talk about it in the next article from the EI series.

- General intelligence was studied using the Wechsler intelligence measurement scale, which includes verbal (it has 6 tests) and non-verbal parts (5 tests). nine0091

- Personality traits were studied using the NEO-PIR — test, which examines five basic personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience.

All study participants underwent computed tomography and "3D maps" of the cerebral cortex.

In his research, Barbie made groundbreaking conclusions: “Intelligence really depends to a greater extent on basic cognitive abilities such as attention span, perception, memory, and language. But it also depends on interaction with other people. Basically, we are social beings, and our understanding as such implies not only basic cognitive abilities, but also the ability to apply these abilities in social situations, navigate the social world and understand others. nine0242

But it also depends on interaction with other people. Basically, we are social beings, and our understanding as such implies not only basic cognitive abilities, but also the ability to apply these abilities in social situations, navigate the social world and understand others. nine0242

Emotional intelligence in various areas of life

In recent decades, numerous studies have been carried out in the field of EI. They proved the importance of EI in various areas of life.

Psychologist Travis Bradberry, one of the contemporary researchers in emotional intelligence and author of Emotional Intelligence 2.0 58% of success in all activities. In addition, there is a direct relationship between the level of EQ (emotional quotient) and the level of income. nine0242

EI in education

In a 2004 study, John Mayer and colleagues looked at the relationship between EI and performance or problem-solving skills and found that it contributes to academic excellence.

At the beginning of the study, the correlation between EI and general intelligence was not significant. However, when the study focused on emotion-related tasks for 90 psychology students, it found positive relationship between "experiencing emotions", on the one hand, and the student's GPA and year of study in this program, on the other.

EI and deviant/problem behavior

A 2004 study by Salovey, Mayer, and Caruso showed that when correlating intelligence with various personality traits, there is an inverse relationship between high EI and bullying, aggressive behavior, smoking, drug use. nine0011

A study of the behavior of 59 participants in a violence prevention program showed that adequate perception of emotions is inversely proportional to psychological aggression (expressed in insults and emotional pressure).

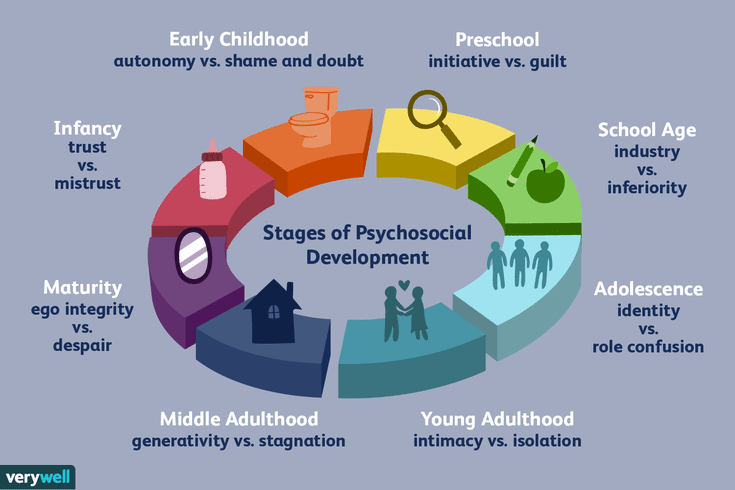

EI and child development

Increasingly, EI research is being conducted among children and adolescents. They demonstrate the relationship of EI with socialization and academic achievement among children. In a 2013 longitudinal study of children aged three to four, Susan Denham and colleagues assessed children's ability to control and recognize emotions. nine0011

They demonstrate the relationship of EI with socialization and academic achievement among children. In a 2013 longitudinal study of children aged three to four, Susan Denham and colleagues assessed children's ability to control and recognize emotions. nine0011

Researchers have found an association between greater control and recognition of emotions and improved social skills between the ages of three and four and beyond.

EI and other people's attitudes

Mayer notes that a high level of EI is associated with a more positive perception of the person who has it by other people.

EI and well-being

Mayer found a correlation between EI and life satisfaction and self-esteem. In addition, high EI is associated with lower levels of depression. nine0011

EI and social behavior

Research by Mayer, Salovey and Caruso in 2014 showed that the ability to control emotions often determines the quality of interaction with others.