Social interactions with children

Social Connection On Child Development

Blog

01/18/2019

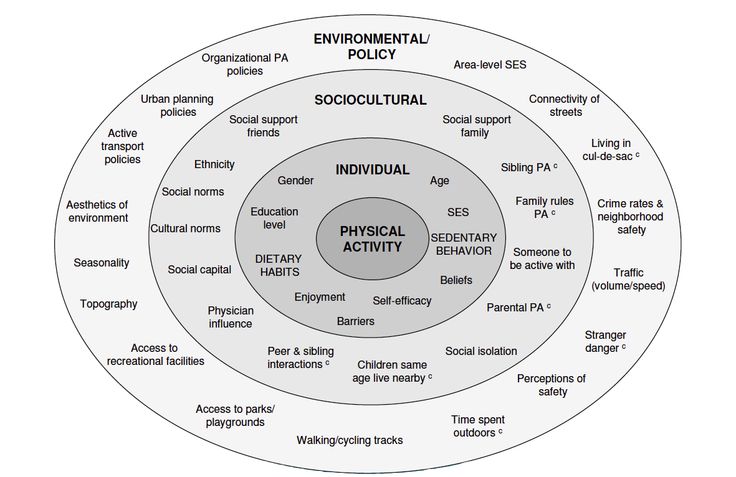

We were not meant to go through life alone. Healthy relationships and social support systems from the community are vital to lifelong wellness, and these interactions begin in childhood. Social connections go far beyond not feeling “lonely,” but rather they are the conduits of healthy childhood development. Positive social connections with people at all stages of life help ensure healthy development, both physically and emotionally. Just remember, children learn by example and when they witness positive relationships or are emotionally supported, that observed behavior will aid in their emotional skills and cognitive functioning later on. As your developing child grows from a baby into a toddler, and then into a teenager and an adult, their social networks will shift and change dramatically. However, through each stage of development, there are specific mental and behavioral needs that are met through socialization.

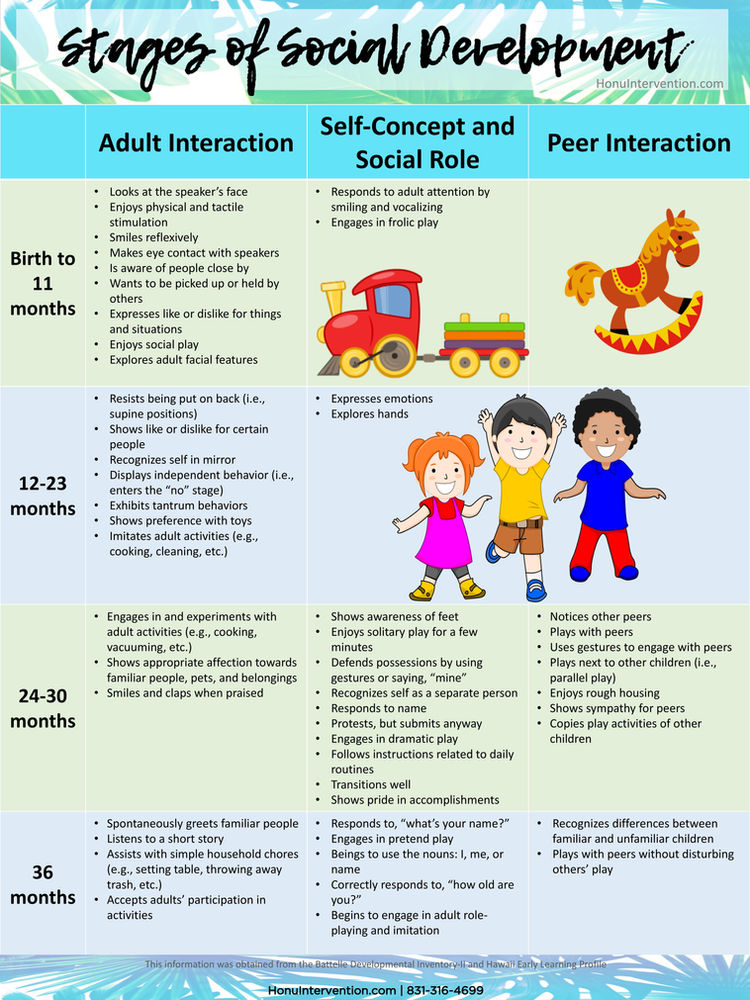

Social interaction is closely related to emotional development in infancy. Your baby’s primary connections to the outside world at this age are through you – his primary caregivers! Specifically, the individuals in an infant’s home who are caring for them, providing their food, water, and shelter, and interacting with them daily are the people who are meeting these socialization needs between birth and twelve months of age. Babies will develop trust and love for their caregivers because they are given adequate love and nurturing from their environment or they will develop mistrust and indifference for people and the world because they aren’t given those resources. During this stage, healthy social growth is all about attachment and bonding with parent and child.

If positive bonding experiences do not happen, the pathways that are needed in a child’s brain for normal and healthy relational experience can actually be lost entirely. There have been tragic case studies of children who spent the earliest years of their lives in minimal human contact, who later demonstrated a severe lack of emotional development in the absence of love, language and attention. What research has shown is that children’s ability to maintain a healthy relationship will greatly depend on the care and treatment they recieve from their caregiver early on.

What research has shown is that children’s ability to maintain a healthy relationship will greatly depend on the care and treatment they recieve from their caregiver early on.

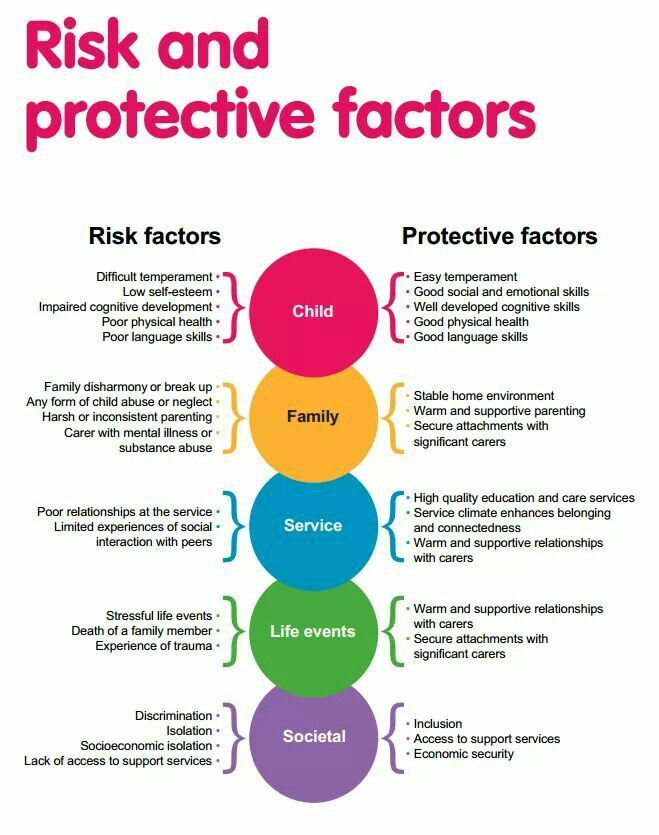

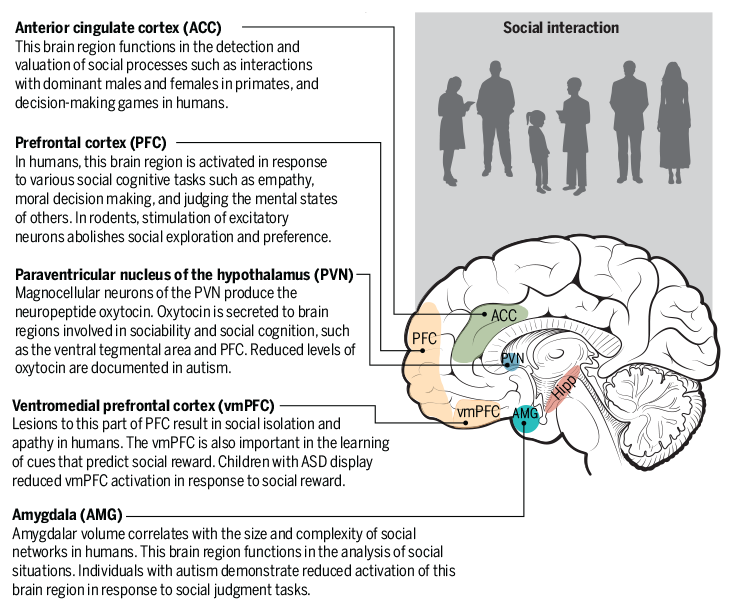

Not only can a child’s emotional development be hindered by a lack of social connection, the physical growth of their brains can as well. In fact, research has shown a reduced growth in the left hemisphere, which may lead to increased risk for depression in children who suffered neglect or another extreme form of insecure attachment in their early years. Additionally, they may exhibit an increased sensitivity in the limbic system which can lead to anxiety disorders, and a reduced growth in the hippocampus that could contribute to learning and memory impairments.

The most common question that parents ask once they learn of the detriments of these insecure attachments is: “How can I be intentional about bonding with my baby?” Fortunately, most of what is involved in creating positive, social interactions with your child during this time frame is simple. Even just responding to their cues for food, diaper changes, and sleep contribute so much to their development! Other tips for attachment and bonding include singing, cuddling, clapping, playing, tummy time, kangaroo care (or skin to skin contact), soothing them when they cry, reading books to your children, eye contact, holding, babywearing, providing your young children with good nutrition and so much more!

Even just responding to their cues for food, diaper changes, and sleep contribute so much to their development! Other tips for attachment and bonding include singing, cuddling, clapping, playing, tummy time, kangaroo care (or skin to skin contact), soothing them when they cry, reading books to your children, eye contact, holding, babywearing, providing your young children with good nutrition and so much more!

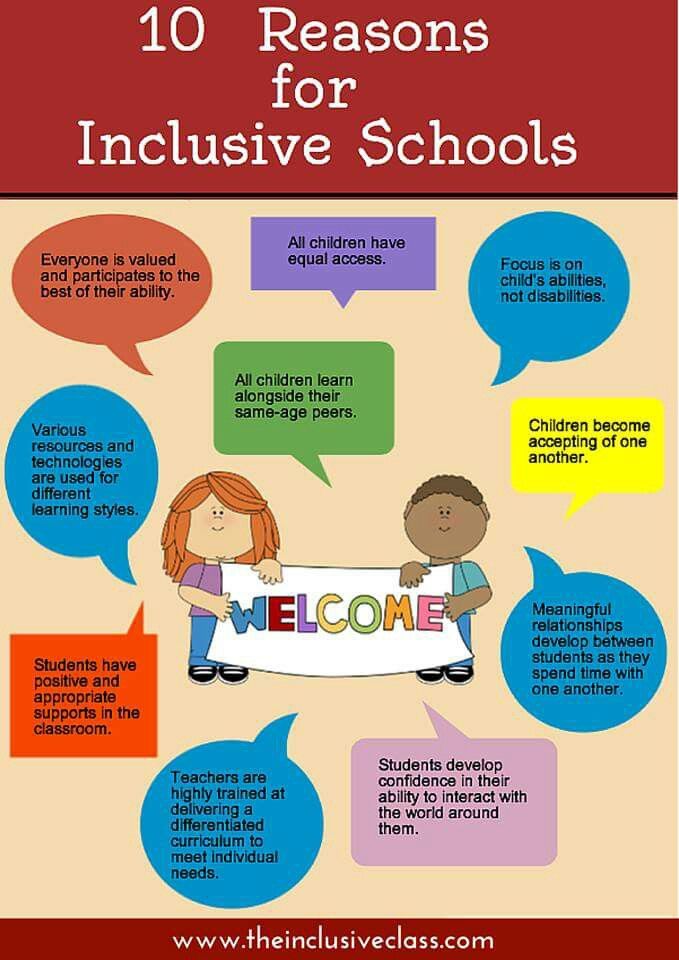

While an infant’s primary need for social connections is met through bonding and connecting with primary caregivers, young children begin to create social relationships outside of their families. Interacting with other children their age (whether this is through daycare, preschool, Sunday school classes, or other events), help children mature in their ability to interact with one another socially.

A common phrase among child therapists is, “Adults Talk, Kids Play.” In a nutshell, children are not always able to articulate their thoughts, feelings, and experiences, but they are able to express them through play! Play is a powerful tool for learning, engagement, and growth.

The first type of play that young children typically engage in is known as parallel play. This is when kids play beside each other without truly interacting with each other. However, as they begin to move past these initial social connections, they begin to play more cooperatively. In cooperative play, young children interact in a small group with the same activity. These early practices of cooperative play include symbolic play (such as cooking in a kitchen, talking on the phone, or playing “house”). Children start practicing this type of play as early as toddlerhood and then peaks for the majority of young children between four and five years old. Additionally, as young children continue to develop socially with peers, they will typically enter a stage of “rough and tumble play.” This can include racing, running, climbing, wrestling, or competitive games. This stage is important as kids are developing social skills (such as learning to take turns and follow simple group rules and social norms).

In early childhood, peers will begin to identify one another as their friends. However, it is important to note that the concept of “friendship” is still a very concrete, basic relationship. At this stage of development, friendship only goes as far as sharing toys and playing together, rather than the associated qualities of empathy and support that adolescents and adults develop. However, this does not mean that these early friendships are any less important. In fact, Paul Schwartz, a professor of psychology and child behavior expert, is only one of many professionals who have emphasized the many benefits of childhood friendship. He stated:

“Friendships contribute significantly to the development of social skills, such as being sensitive to another’s viewpoints, learning the rules of conversation, and age-appropriate behaviors. More than half the children referred for emotional behavioral problems have no friends or find difficulty interacting with peers… Friends also have a powerful influence on a child’s positive and negative school performance and may also help to encourage or discourage deviant behaviors. Compared to children who lack friends, children with ‘good’ friends have higher self-esteem, act more socially, can cope with life stresses and transitions, and are also less victimized by peers.”

Compared to children who lack friends, children with ‘good’ friends have higher self-esteem, act more socially, can cope with life stresses and transitions, and are also less victimized by peers.”

Even preschool friendships are helpful in developing social and emotional skills, increasing a sense of belonging and decreasing stress. The tremendous benefits of social connections in early childhood simply cannot be ignored!

Here are some ways that parents can help their little ones develop positive, healthy, and beneficial relationships:

- Model good friendship skills

- Encourage the friendships that are important to your child

- Set up playdates

- Respect your child’s personality and interests

- Emphasize the importance of staying connected

- Ask about who your child’s friends are at school and daycare

- Help your child develop problem-solving and conflict resolution skills

- Model empathy and compassion, and respect for kids

- Encourage your child to start new friendships, and maintain existing ones

- Talk with your child about when it is appropriate or necessary to end a friendship, and how to do so respectfully

- Have conversations about bullying and kindness

Overall, the more that you talk with your child about how to become a good friend, the more good friends they will have. The skills learned through social connections in early childhood are not only important for their current friendships, but for your child’s future relationships as well.

The skills learned through social connections in early childhood are not only important for their current friendships, but for your child’s future relationships as well.

As children transition to adolescence, they begin to spend less time with their parents and siblings and more time in a social environment. As a result, friendships with peers become an increasingly important source of social connections, and characterizations of youths’ social relationships carry high relevance for developmental psychology. It is during the adolescent period that peer interactions arguably hold the greatest importance for individuals’ social and behavioral functioning.

When a teenager has healthy friendships, they can truly reap the benefits. Positive friendships provide youth with support, companionship, and a sense of belonging. They offer opportunities for the development of social skills. For example, adolescents learn to cooperate with others, communicate effectively, resolve conflicts, and resist negative peer pressure (which can either discourage or reinforce healthy behaviors).

Evidence also suggests that positive friendships in adolescence can lay the groundwork for successful adult relationships (including romantic relationships). Your kids are learning how to make, maintain, and end relationships, and they are able to practice being honest, compassionate, and trustworthy while doing so. As they develop their own identity in relation to the world around them, healthy friendships provide youth with support, companionship, and a sense of belonging. Teens who have supportive friendships are also more likely to do well in school, and be more equipped to navigate and recover from life’s challenges. Peer relationships are especially important during times of difficulty, as they offer a sense of belonging and relief from depression, anxiety, and stress. Feelings of closeness in friendships are intrinsically linked to increased resilience.

Overall, adolescence is a period of rapid change. Not only are your kids’ bodies growing and changing, but they are developing socially and emotionally as well. Friendships become more complex as teenagers view them more abstractly, through an exchange relationship of “give and take,” as well as a true social support system. For girls and boys alike, friendships in adolescence are far more emotionally involved than they were just a few short years prior. Because of this, peer relationships are also a common source of stress and anxiety.

Friendships become more complex as teenagers view them more abstractly, through an exchange relationship of “give and take,” as well as a true social support system. For girls and boys alike, friendships in adolescence are far more emotionally involved than they were just a few short years prior. Because of this, peer relationships are also a common source of stress and anxiety.

Peer pressure can have a negative impact on an individual, such as when it convinces your child to try smoking or drinking. Here are some tips (adapted by those provided by researchers at the Cleveland Clinic) to help reduce the negative influences of peer pressure in the social interactions of teenagers:

- Create a strong relationship and bond with your child, it is always advised to encourage your children to be open with you and to have honest communication.

- Discuss the negative impact of peer pressure with your child, as they will be better prepared to say no and resist negative influences.

- Reinforce the values that are important to you and your family.

- Teach your child the importance of being assertive when necessary.

- Give your teen plenty of space to also breath. Don’t be a hovering parent that is watching every move their child makes. You can’t expect him or her to do exactly as you say. Expecting perfection is setting them up to fail.

- Instead of only telling your teenager what to do, try to listen first and gain their perspective.

- Implement discipline, structure, boundaries, and consequences for negative actions or harmful behaviors.

Additionally, one the best things you can do for your child and their social connections in adolescence is to foster and encourage your teen’s abilities, strengths, identity, and self-esteem. By doing so, they will not be susceptible to the influences of others. In addition, the development of a positive self-image is vital to positive relationships as your child transitions from an adolescent to a young adult. Here are some practical things that you can do to build your teenager’s self-esteem:

Here are some practical things that you can do to build your teenager’s self-esteem:

- Provide words of encouragement for your child every day. It is so important to recognize and acknowledge things your child does right, and not just their mistakes. Affirm them frequently! Identifying their talents and successes will help your teenager learn to focus on their strengths.

- On the other hand, be sure to give constructive criticism. Feedback is essential to growth. Be willing to have the tough conversations, and try to do so with grace.

- Allow your teen to make mistakes. Not only can overprotection or making decisions for teens be perceived as a lack of faith in their abilities, but it does not allow their confidence to grow. Sometimes, our best lessons are learned through failure. The safest time and place to fail should be while they are still in your care as their parents.

- Initiate conversations about self-esteem, identity, worth, and self-image, as well as why these things are important.

Overall, Dr. Bruce Perry, a child psychiatrist, said it best when he stated in a study:

“The more healthy relationships a child has, the more likely he will be to recover from trauma and thrive. Relationships are the agents of change and the most powerful therapy is human love.”

No matter which stage of development your child is in, encouraging social connections is so important to their current and future well-being and mental health. Loving relationships truly are powerful in a child’s life and, as parents, we must remember that this type of love begins at home.

SOURCES:https://www.mentalhelp.net/articles/infancy-emotional-and-social-development-social-connections/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5330336/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5330336/#CIT0006

https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/play-learning/active-play/rough-play-guide

https://hvparent.com/importance-of-friendship

https://my. clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/12942-fostering-a-positive-self-image

clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/12942-fostering-a-positive-self-image

https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/center-for-adolescent-health/_docs/TTYE-Guide.pdf

https://www.brightfutures.org/mentalhealth/pdf/06BFMHAdolescence.pdf

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. By continuing to use our site you agree to our Privacy Policy. ACCEPT

Conversation and social skills

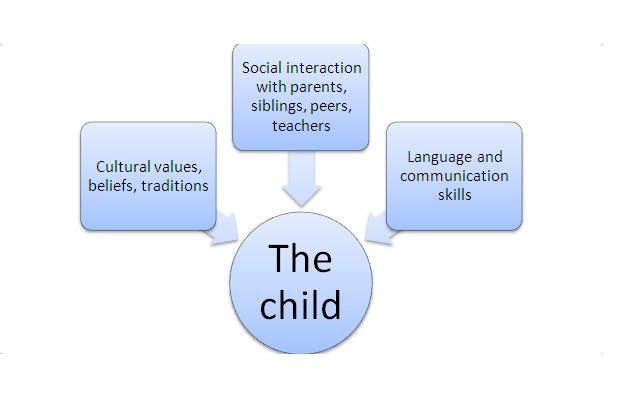

Children communicate from birth, and social interaction is a key purpose of language learning.

Most children are innately social, creative and motivated to exchange ideas, thoughts, questions and feelings … [They use] gestures, movement, visual and non verbal cues, sounds, language and assisted communication to engage and develop relationships…

- VEYLDF (2016)

As children develop, they use verbal and nonverbal communication for a range of purposes including showing, sharing, commenting, questioning, requesting (and more).

Through opportunities to observe and participate in social situations, children learn how conversation (and social interaction) works. These important social rules and skills enable children to communicate with others in more sophisticated ways.

Thus, the development of conversation and social skills is dependent upon opportunities for children to interact with peers and adults, as part of supportive and enriching experiences.

Children use nonverbal (including eye gaze, gestures) and verbal communication (including speech, vocabulary, and grammar) to engage in conversation and social interaction:

Children’s wellbeing, identity, sense of agency and capacity to make friends is connected to the development of communication skills, and strongly linked to their capacity to express feelings and thoughts, and to be understood.

- VEYLDF (2016)

By planning experiences with a focus on conversation and social skills, educators can promote positive interaction and communication. This can help children to successfully communicate their wants and needs, and nurture meaningful relationships with peers.

This can help children to successfully communicate their wants and needs, and nurture meaningful relationships with peers.

The following ages and stages are a guide that reflects broad developmental norms, but does not limit the expectations for every child (see VEYLDF Practice Principle: High expectations for every child). It is always important to understand children’s development as a continuum of growth, irrespective of their age.

Early communicators (birth - 18 months)

- communicate mainly with gestures, vocalisations, and facial expressions

- from 8 months, start to use gestures/vocalisations/eye gaze for:

- requesting

- refusing

- commenting

- communicative games (e.g. peek-a-boo)

- calling to get attention

- requesting

Early language users (12 - 36 months)

From 12 months, start to use words as well as nonverbal communication for:

- expressing feelings, like ‘look! doggie!’

- requesting, like ‘Up!’ or ‘bottle’ (with gestures)

- refusing, like ’no apple!’

- commenting, like ‘ball!’ or ‘big ball!’

From 18 months:

- requesting information, like ‘what this?’

- answering questions, like Educator: ‘Do you like the sand?’ Child: (nods) ‘Yeah!’

From 24 months:

- start to use “please”

- begin to stay on one topic of conversation

- take multiple turns in a conversation

- request repetition if they do not understand

Language and emergent literacy learners (30 - 60 months)

- take longer turns in conversation

- begin to understand and use “politeness”, when expected by adults

- begin to communicate their wants and needs more clearly (may start to ask for permission)

- may use language for jokes or teasing

- will engage in longer conversations (4-5 turns)

From 42 months, begin to use language to:

- report on past events

- reason

- predict

- express empathy

- keep interactions going

Children’s learning of social skills can be powerful additions in their communicative toolkit. When children can communicate their wants and needs, it facilitates their ability to get along with others. Thus, social skills are closely linked to children’s language development. They also have links to children’s wellbeing, identity, and emotional development (see VEYLDF, 2016).

When children can communicate their wants and needs, it facilitates their ability to get along with others. Thus, social skills are closely linked to children’s language development. They also have links to children’s wellbeing, identity, and emotional development (see VEYLDF, 2016).

Some key social skills that children develop include:

Greetings and farewells

- starts with eye contact, smiling, and eventually a waving gesture

- phrases like: ‘Hello’, ‘Hi’, ‘How are you?’ ‘I am well, thank you’ and ‘Bye’, ‘Goodbye’, ‘See you tomorrow!’, ‘Have a nice weekend!’

- important for maintaining relationship and starting/ending interactions productively.

Children’s greetings and farewells begins with

gestures and develops into words and phrases.

Photo: Brian

Commenting

- begins with eye contact, pointing, vocalisation, and then single words

- provides a starting point for joint attention, with phrases like: ‘Look at the …’ ‘I like …’ ‘What a nice …’

- develops into more sophisticated comments like ‘I have a doll like this at my house’, ‘The hat you chose today is very bright!’

- provides opportunities to start and maintain conversations

- can be used to stay on a conversation topic, or change topics

- children share their interests; and show interest in what others are doing/saying.

Requesting

- begins with eye contact, grabbing/pointing/”up” gestures, vocalisations, and then single words

- requests can be for food/drink, ‘more’, ‘again’, wanting a turn

- develops into requesting help, and asking for permission

- eventually involves using ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ when these are reinforced.

Joining in

- knowing when and how to join groups/games/conversations

- initially using eye contact, gestures, vocalisations, and single words to join in play

- eventually using requests like: ‘Can I play?’; or general openers like ‘What are you doing?’

Sharing

- sharing toys, space, turns etc.

- from a developmental perspective, sharing is not expected to be easy for young children

- providing modelling and reminders of how to share is important

- allowing children the freedom to play independently (and not having to share) is also important sometimes

- eventually, sharing is an important social skill linked to the emotional competencies like empathy and taking others’ perspectives.

Negotiating

- managing disagreements and coming to solutions>

- this involves taking the perspective of another child, which is developmentally challenging, and is typically easier later in childhood<

- mostly scaffolded by adults during early childhood

- relates to notions of agency, identity, and how we understand the view of others (empathy)

- in older children, is an important social skill, so that children learn to reach compromises independently.

Complimenting

- develops later in early childhood, involving children providing comments which have a positive impact on others

- is modelled and facilitated by educators

- is linked to empathy and socio-emotional awareness.

Topics

Every conversation has a topic. A go-to conversational topic for adults is the weather! For children, topics usually come from their experiences of the everyday world around them (e.g. people, food, drink, toys, pets, games, sand, transport, animals, paint etc. ).

).

It is important to expose children of all ages to more abstract topics (e.g. emotions, sustainability, culture). However, we only start to expect children to contribute ideas and actively engage in conversations about more abstract topics when children are older (~3 or 4 years old).

Educators can use their observations of children’s interests and communication to help choose particular conversational topics. These conversations can also be linked to learning themes (e.g. relationships, the environment, animals, family etc).

Children’s conversational topics start with theeveryday, and become more sophisticated and

abstract as they grow and develop their

language skills. Photo: Lars Ploughmann

Turns

Conversations are similar to a tennis game — one speaker has a turn, then the other speaker has a turn. So, conversations are simply turns going back-and-forth between speakers, usually staying on a particular topic.

Like in tennis, some turns might be longer than others, like when a speaker talks about something they know for a number of sentences in a row. In a good conversation, all speakers do a similar amount of speaking and listening.

In a good conversation, all speakers do a similar amount of speaking and listening.

The turns children make are initially very short (a gesture, eye gaze, vocalisation, or a single word). These turns develop into phrases, sentences, and longer stretches of language.

Playing in ways that encourages back-and-forth turn-taking with children (using a physical or vocal game) is a great way to get ready for conversational turn-taking.

Listening and empathy

Being a good conversationalist is as much about listening, as it is about speaking. Listening is also closely linked to the development of empathy, as we need to listen to others to understand their perspectives.

We can scaffold children’s interest and concentration on other people’s ideas/conversational turns by:

- by modelling good listening, ourselves

- reminding children of what others’ have said, and what their ideas were

- playing listening/memory games

- praising children when they demonstrate good listening and empathy.

As children learn how to listen to others it

develops their empathy and fosters

meaningful friendships. Photo: Nithi Anand

Nonverbal communication

Communication is not just about the words we use. Our nonverbal language can often say a lot more than our actual choice of words! Below are some important types of nonverbal communication.

Prosody (loudness, pitch, and speed that we speak)

- different volumes and speaking rates are appropriate depending on the context

- for example outside versus inside; naptime versus storytime versus playtime.

Facial expressions and eye contact

- shows emotions and interests

- can be used to interpret people’s frame of mind

- important for demonstrating you are listening and interested.

Body language and gestures

- gestures (including showing and requesting) communicate much of children’s intentions

- the way we face our bodies towards others, or use our arms and hands during conversation can also communicate our thinking.

Maintaining conversations

Topic maintenance is the ability for children to stay on a particular topic for several turns in a conversation. This develops gradually in early childhood, with the number of turns on a given topic typically increasing with age (Paul, Norbury, Gosse, 2017):

- up to 24 months: usually 1-2 turns

- 24-42 months: approximately 2-3 turns

- 42 months onwards: approximately 4-5 turns.

Educators can support children’s topic maintenance by scaffolding conversations on particular topics (e.g. ‘Wow, look at the …’, ‘What was your favourite part, [child’s name]?’, ‘What do you think about this?’

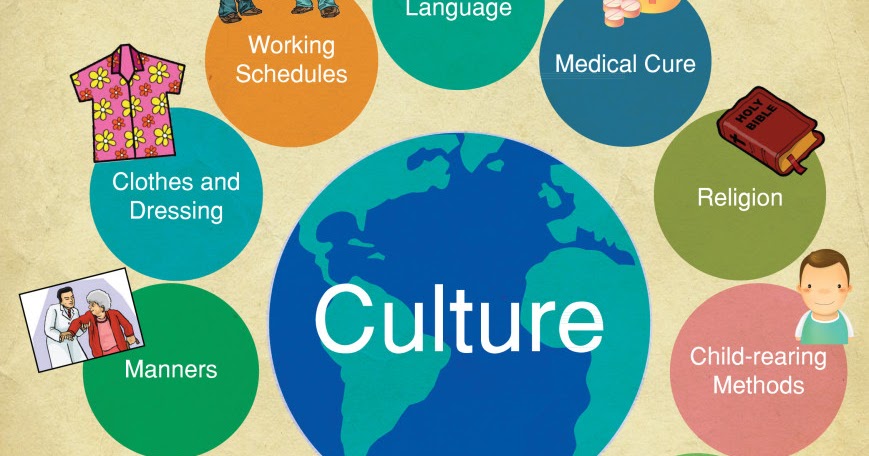

When interacting with others, there are certain social and conversational rules and conventions specific to certain cultures. These rules are known as pragmatics, and are thought of as the “use” component of oral language (Bloom & Lahey, 1978).

According to Halliday (1975), children are motivated to develop language because of the different functions it serves for them (i. e., learning language is learning how to make meaning). He identified seven functions of language that help children to meet their physical, emotional and social needs in the early years. The functions enable children to use language to meet their physical needs, regulate other’s behaviour, express feelings, and interact with others. As children get older the language functions become more abstract and enable interaction within the child’s environment.

e., learning language is learning how to make meaning). He identified seven functions of language that help children to meet their physical, emotional and social needs in the early years. The functions enable children to use language to meet their physical needs, regulate other’s behaviour, express feelings, and interact with others. As children get older the language functions become more abstract and enable interaction within the child’s environment.

Studies show that children are born ready to make meaning out of a wide range of sounds, but their language development requires conversations with more-knowledgeable speakers who listen and model appropriate language.

Children do not learn language by imitation. They learn to talk by talking to people who talk to them; people who make efforts to understand what they are trying to say.- Raban, (2014, p.1)

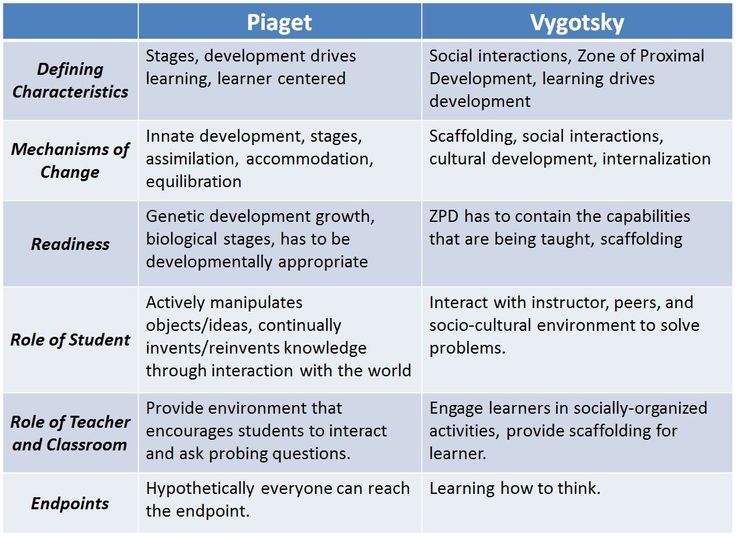

According to the sociocultural theories of language development (Vygotsky, Bruner), children learn through interactions with more knowledgeable peers. Conversation and social skills are best supported through meaningful interactions with peers and adults.

Conversation and social skills are best supported through meaningful interactions with peers and adults.

Children learn with their peers, sharing their feelings and thoughts about learning with others. They begin to understand that listening to the responses of others can help them understand and make new meaning of experiences.

- VEYLDF 2016

When you choose conversation and social skills as a learning focus, you provide children with opportunities to develop meaningful relationships with their peers, educators, and families.

Adults’ positive engagements with children promote emotional security, children’s sense of belonging, cultural and conceptual understandings and language and communication. Positive, respectful engagement also teaches children how to form strong bonds and friendships with others.

- VEYLDF 2016

The ability for children to interact with others successfully—by managing their emotions and behaviours—links to progress in a range of developmental areas in early childhood(Mashburn et al. , 2008). Success with social skills is strongly linked to the emergence of self-identity, sense of wellbeing, as well as social/academic progress in early primary school (e.g. Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2004).

, 2008). Success with social skills is strongly linked to the emergence of self-identity, sense of wellbeing, as well as social/academic progress in early primary school (e.g. Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2004).

Children’s development of conversation and social skills is best supported when engaged in meaningful, sustained, and rich language experiences. Studies show that children’s social skills are best supported when educators are cued into children’s emotional/social needs (Mashburn et al., 2008)

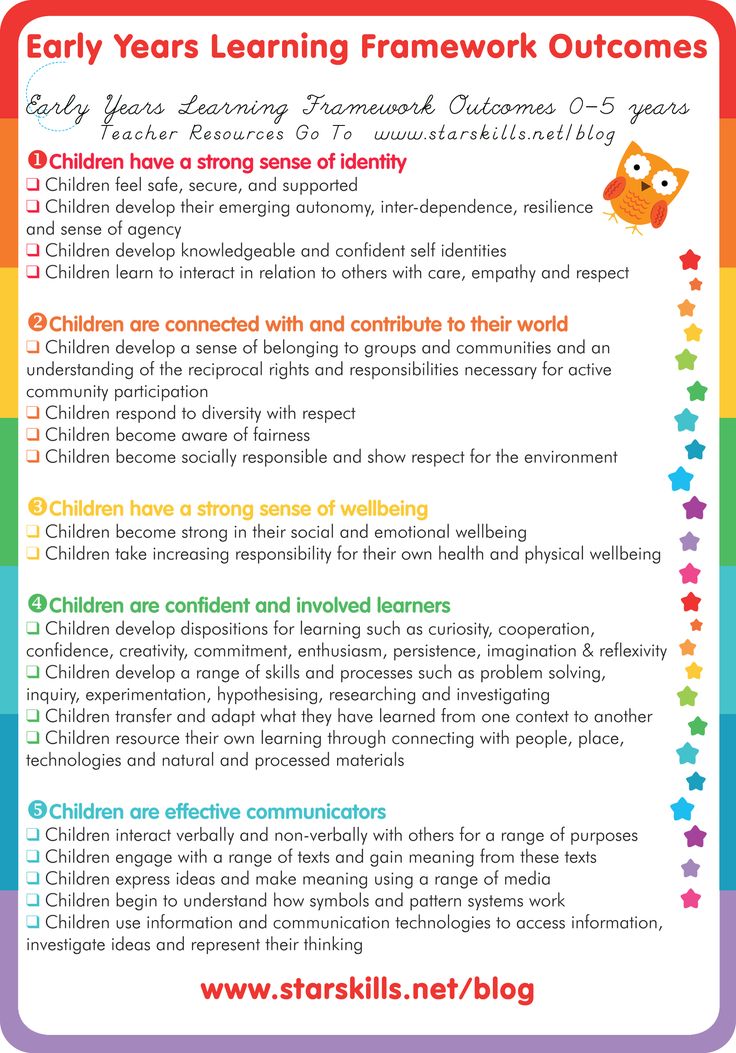

- Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (2016)

- VEYLDF Illustrative maps

Outcome 1: identity

Children feel safe, secure and supported

- build secure attachment with one and then more familiar educators

- establish and maintain respectful, trusting relationships with other children and educators

- openly express their feelings and ideas in their interactions with others

- respond to ideas and suggestions from others

- initiate interactions and conversations with trusted educators

- confidently explore and engage with social and physical environments through relationships and play.

Children develop their emerging autonomy, inter-dependence, resilience and sense of agency

- increasingly cooperate and work collaboratively with others

- begin to initiate negotiating and sharing behaviours.

Children learn to interact in relation to others with care, empathy and respect

- show interest in other children and being part of a group

- express a wide range of emotions, thoughts and views constructively

- empathise with and express concern for others

- reflect on their actions and consider consequences for others.

Outcome 2: community

Children develop a sense of belonging to groups and communities and an understanding of the reciprocal rights and responsibilities necessary for active civic participation

- cooperate with others and negotiate roles and relationships in play episodes and group experiences

- take action to assist other children to participate in social groups

- build on their own social experiences to explore other ways of being

- participate in reciprocal relationships

- gradually learn to ‘read’ the behaviours of others and respond appropriately

- are playful and respond positively to others, reaching out for company and friendship

- contribute to democratic decision-making about matters that affect them.

Outcome 3: wellbeing

Children become strong in their social, emotional and spiritual wellbeing

- remain accessible to others at times of distress, confusion and frustration

- share humour, happiness and satisfaction

- increasingly cooperate and work collaboratively with others

- show an increasing capacity to understand, self-regulate and manage their emotions in ways that reflect the feelings and needs of others.

Outcome 4: learning

Children resource their own learning through connecting with people, place, technologies and natural and processed materials

- engage in learning relationships

- experience the benefits and pleasures of shared learning exploration.

Outcome 5: communication

Children interact verbally and non-verbally with others for a range of purposes

- interact with others, express ideas and feelings and understand and respect the perspectives of others

- explore ideas and concepts, clarify and challenge thinking, negotiate and share new understandings

- express ideas and feelings and understand and respect the perspectives of others.

Modelling conversation and social skills

- use every interaction with children as an opportunity to demonstrate positive conversation and social skills

- encouraging turn taking in everyday activities through nonverbal turn-taking opportunities games (e.g. rolling ball back and forth, each having a turn during a construction or cooking experience)

- turn taking should involve multiple back-and-forth exchanges

- remember that children learn how to communicate by observing adults’ and older peers

- show how conversational topics can be maintained, and what good listening/empathy looks like

Setting up opportunities for social interaction

- set up experiences and spaces that encourage interaction between small groups of children and with adults

- see the following teaching practices for ideas: play, sociodramatic play, fine arts, performing arts, as well as storytelling, reading/writing with children, and language in everyday situations

- use every experience and daily routine as an opportunity to develop conversation and social skills

- use engaging materials that allow for individual and shared play

- play games with children that involve turn-taking, sharing, and team work

Experience plans and videos

For age groups (birth - 12 months)

- Bathing Babies

- Developing Conversation and Social Skills

- Getting Along with Others

- Making Meaning through Play

Early language users (12-36 months)

- Bathing Babies

- Developing Conversation and Social Skills

- Getting Along with Others

- Making Meaning through Play

- Walk and Talk

- Worm Farm: Discussion around Texts

Language and emergent literacy learners (30 - 60 months)

- Getting Along with Others

- Journey to Healesville: Learning through Drama

- Print in Sociodramatic Play

- Worm Farm: Discussion around Texts

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

(1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Halliday, M. A. (1975). Learning How to Mean. London: Edward Arnold.

Mashburn, A. J., Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Barbarin, O. A., Bryant, D., … Howes, C. (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development, 79(3), 732–749.

Paul, R., Norbury, C., Gosse, C. (2017) Language disorders from infancy through adolescence: Listening, speaking, reading, writing, and communicating (5th Ed.). Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby.

Raban, B. (2014). Talk to think, learn and teach (pdf - 1.14mb). Journal of Reading Recovery, Spring 2014, 1-11.

Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training (2016) Victorian early years learning and development framework (VEYLDF).Retrieved 3 March 2018.

Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (2016) Illustrative Maps from the VEYLDF to the Victorian Curriculum F–10. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

Retrieved 3 March 2018.

Webster-Stratton, C., & Reid, M. J. (2004). Strengthening social and emotional competence in young children-The foundation for early school readiness and success: Incredible Years classroom social skills and problem-solving curriculum. Infants & Young Children, 17(2), 96–113.

Social interaction of children: search for hot spots

Top menu

Main menu

preschoolers Education and training of preschool children

We advise you to look

YOU MUST ENABLED JS

- Material Information

- Preschool Psychology

- Views: 4641

Material content

- Children's Social Interaction: Finding Hot Spots

- Social behavior of the child

- Stable behavioral if-then signatures

- Self-control weakens aggressive tendencies

- Graphical display of hotspots of the if-then stress signature nine0028

- All pages

Page 1 of 5

Vediko is a summer recreation camp in the New England countryside. In this camp, children aged 7-17 lived for six weeks in summer wooden houses.

In this camp, children aged 7-17 lived for six weeks in summer wooden houses.

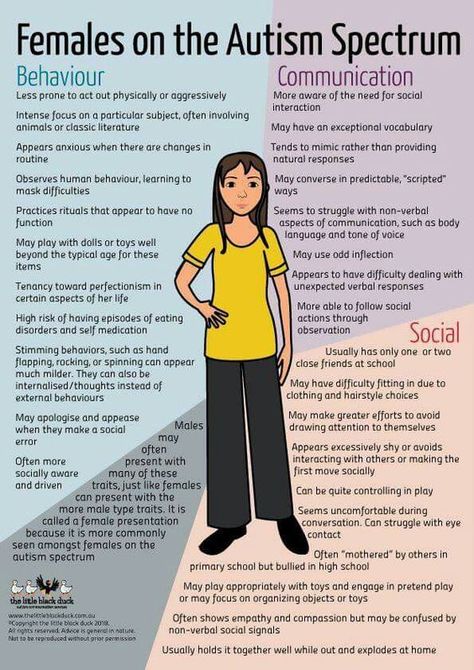

They lived in small same-sex peer groups with five adult counselor caregivers. Children were enrolled in this program because of serious problems with social adaptation who appeared at home or at school, especially aggression, alienation and depression . All children came predominantly from families living in and around Boston.

The purpose of creating a psychotherapeutic environment in the camp was to develop in children more adaptive and constructive social behavior .

In the mid-1980s, my longtime research partner Yuichi Shoda and I were given permission to conduct a major research project at the camp, with the approval of the camp staff and personally Jack Wright, who headed the research department at Vediko. Jack, Yuichi, and the research staff systematically observed the children's behavior for six weeks. nine0009

Researchers diligently, but unobtrusively, recorded all the child's ongoing social interactions in the camp in different conditions and during various activities: while staying at home, at the lakeside and in the dining room, while doing art and crafts, etc. This there was extensive data collection work, and Yuichi and I collaborated extensively with Jack in planning the project and analyzing the results.

This there was extensive data collection work, and Yuichi and I collaborated extensively with Jack in planning the project and analyzing the results.

Observers recorded what each child did while interacting with other children in the same set of situations day after day throughout the summer shift. Jack, Yuichi, and I focused on analyzing the negative manifestations of the "hot" emotional system—primarily verbal and physical aggression—that brought these children to Vediko in the first place. nine0009

Strong emotions usually did not appear when children were stringing colored beads or swimming in a lake. This continued until all was well. But they became furious when one child deliberately destroyed a toy tower that another was diligently building, or responded to a friendly invitation to build a tower together with insults or rude ridicule.

To identify such "hot spots" - psychological situations that caused aggression in children , — the researchers first of all recorded what the children themselves and the educators answered to the request to describe other children in the camp. The youngest quantified the characteristics they gave to others: Joe pushing and screaming sometimes; Pete fights - all the time.

The youngest quantified the characteristics they gave to others: Joe pushing and screaming sometimes; Pete fights - all the time.

However, the descriptions given by counselors and older children became more conventional and contextualized in specific types of interpersonal situations that generated emotional outbursts—in "hot spots" that caused sensory distress. “Joe always loses his temper” might have been the first statement, but after a few other general phrases, the children began to specify the types of “hot” provocative situations: “If other children start laughing at him because of his glasses” or “If he is expelled from the game". nine0009

Based on these descriptions, the research team observed what each child did over and over again during social interaction at the camp.

Five types of such situations were identified: three negative (“the peer teased, provoked or threatened”, “the adult warned” and “the adult punished by “exclusion from the process””) and two positive (“the adult praised” and “the peer behaved friendly” ).

- Forward nine0028

- Back

- Forward

YOU MUST ENABLED JS

Social interactions in childhood: friendship, conflict avoidance and learning to lie | Mitrofanova

S. Yu. Mitrofanova

https://doi.org/10.28995/2073-6401-2022-3-93-103

Full text:

- Abstract

- About the author

- References

Annotation

The article focuses on the analysis of friendship, sabotage in conflict, teaching children the practices of lying as some formats of social interaction practices in childhood, laying the foundations of social order in society. The focus of current research was identified on: 1) the impact of family migration on children's friendship, 2) the conceptualization of friendship between primary school children in ethnically diverse communities, 3) the understanding of friendship in the family and school among refugee girls, 4) the "effects" of neighborhood, negative the consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood, 5) sabotage practices in the conflict between sibling children, 6) how parents teach their children to tell lies, 7) the eventful childhood of modern boys and girls. The considered practices are mastered earlier by boys and children from wealthy families, girls and children from poor families - later. It is concluded that the practices of friendship, sabotage and lies indicate the features of the practices of social interaction in childhood, but it actualizes the issue of the need to continue their research in the context of the conditions of Russian childhood. nine0009

The considered practices are mastered earlier by boys and children from wealthy families, girls and children from poor families - later. It is concluded that the practices of friendship, sabotage and lies indicate the features of the practices of social interaction in childhood, but it actualizes the issue of the need to continue their research in the context of the conditions of Russian childhood. nine0009

Key. words

friendship of children, ethnicity, migration, sabotage in conflict lie practices, eventfulness of childhood,

about the author

S. Yu. Mitrofanova

Samara National Research University S.P. Koroleva

Russia nine0009

Svetlana Yu. Mitrofanova, Candidate of Sociological Sciences, Associate Professor

443086, Russia, Samara, st. Moskovskoe shosse, 34

Moskovskoe shosse, 34

References

The Eventfulness of Childhood: On the Empirical Evidence of the Generation Theory. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya. 2020. No. 3. P. 3–15.

2. Mitrofanova 2015 - Mitrofanova S.Yu. Reference points and constructs of "adulthood" in children's ideas about their future life // Bulletin of the Russian State Humanitarian University. Series: Philosophy. Sociology. Art criticism. 2015. No. 7 (150). pp. 131–138. nine0009

3. Protecting 2022 - Protecting Children: Strategies, Practices, Resources: Sat. materials based on the results of the All-Russia. scientific and practical. conf. on topical issues of prevention of deviant behavior of minors (May 31 - June 1, 2022, Moscow) / Ed. E.N. Skorina, E.B. Batorova, E.G. Artamonova. M.: Center for the Protection of the Rights and Interests of Children, 2022. 550 p.

4. Bergner et al. 2020 – Bergner D., Aronson O., Enell S. Friends through school and family: Refugee girls’ talk about friendship formation // Childhood. 2020 Vol. 27(4). P. 530–544. nine0009

2020 Vol. 27(4). P. 530–544. nine0009

5. Edling, Rydgren 2012 – Edling Ch., Rydgren J. Neighborhood and Friendship Composition in Adolescence // SAGE open A peer-reviewed open access journal published by SAGE. 2012. October-December. Vol. 2. Iss. 4. P. 1–10.

6. Iqbal et al. 2017 – Iqbal H., Neal S., Vincent C. Children’s friendships in super-diverse localities: Encounters with social and ethnic difference // Childhood. 2017 Vol. 24(1). P. 128–142.

7. Lavoie et al. 2016 – Lavoie J., Leduc K., Crossman Angela M., Talwar V. Do As I Say and Not As I Think: Parent Socialization of Lie-Telling Behavior // Children & Society. 2016. Vol. 30. P. 253–264. nine0009

8. Sime, Fox 2015 – Sime D., Fox R. Home abroad: Eastern European children’s family and peer relationships after migration // Childhood. 2015. Vol. 22(3). P. 377–393.

9. Zotevska et al. 2021 – Zotevska E., Cekaite A., Evaldsson Ann C. Enacting sabotage in siblings’ conflicts: Desired objects and deceptive bodies // Childhood.