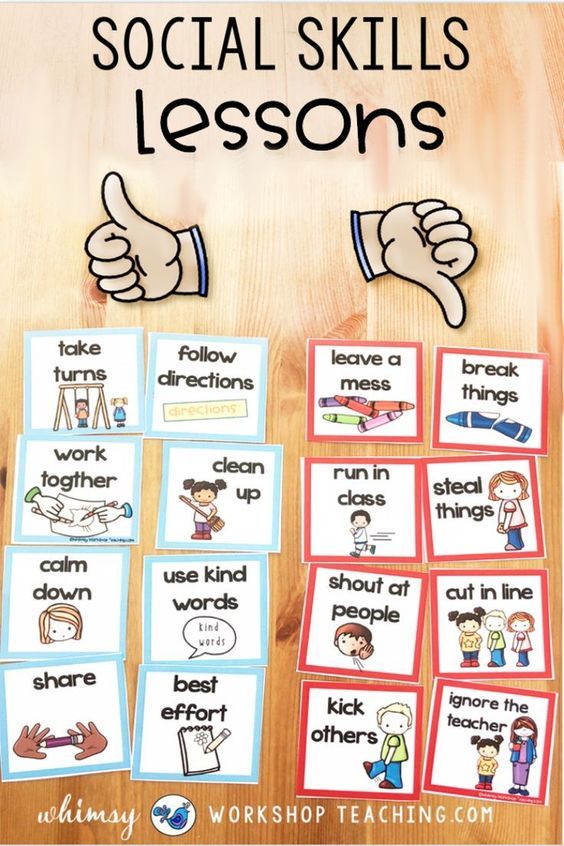

Social skills training for kids

Evidence-based social skills activities for children & teens (w/ teaching tips)

© 2009 – 2021 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

These social skills activities can help kids forge positive relationships — and better understand what other people are feeling and thinking.

How can we help children develop social competence — the ability to read emotions, cooperate, make friends, and negotiate conflicts? Kids learn when we act as good role models, and they benefit we create environments that reward self-control. But there is nothing quite like practice. To develop and grow, kids need first-hand experience with turn-taking, self-regulation, teamwork, and perspective-taking.

Here are 17 research-inspired social skills activities for kids, organized by age-group. I begin with games suitable for the youngest children, and end with social skills activities appropriate for older kids and teens.

1. Turn-taking games

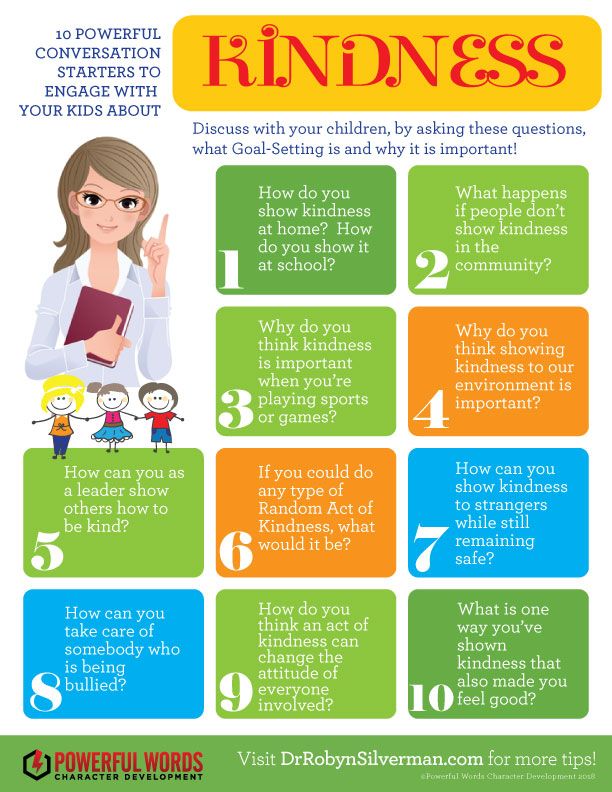

Young children — including some babies — are capable of spontaneous acts of kindness, but they can be shy around new people. So how can we teach them that a new person is a friend?

One powerful method is to have a child engage in playful acts of reciprocity with the stranger. For example, the child take turns pressing the button on a toy, or rolling a ball back and forth. The child and stranger might hand each other interesting objects.

When psychologists Rodolfo Cortes Barragan and Carol Dweck (2014) tested this simple tactic on 1- and 2-year-olds, the children seemed to flip a switch.

The babies began to respond to their new playmates as people to help and share with. By contrast, there was no such effect if children merely played alongside the stranger — without engaging in acts of reciprocity.

2. The toddler “name game”

As early childhood specialist Kathleen Cochran has noted, many children need help with the fundamentals of getting someone else’s attention. They don’t yet understand that it’s important to speak the person’s name.

“It’s such a simple thing,” Cochran says, “yet it’s the beginning of being able to understand another person’s point of view. ” So how do we teach this concept? Cochran and her colleagues recommend this simple social game (Teachers’ College, Columbia University 1999) :

” So how do we teach this concept? Cochran and her colleagues recommend this simple social game (Teachers’ College, Columbia University 1999) :

- Seat children in a circle, and give one of them a ball.

- Ask this child to choose another person in the circle and speak his or her name. Then the child rolls the ball to named individual.

- Once the ball has been received, the next child follows the same procedure — naming an intended recipient and passing the ball along.

3. Music-making and rhythm games for young children

Young children are often inclined to help other people. How can we encourage this impulse? Research suggests that joint singing and music-making are effective social skills activities for fostering cooperative, supportive behavior.

For example, consider this game.

“Waking Up The Frogs”

First, you take a bunch of preschoolers who don’t know each other, and direct their attention to a “pond” — a blue blanket spread on the floor with several “lily pads” on it. Toy frogs sit on the lily pads.

Toy frogs sit on the lily pads.

Then you tell the children the frogs are sleeping. It’s morning, and the frogs need our help to wake up! So you give the children simple music instruments (like maracas), and ask them to sing a little wake-up song while they walk around the pond in time with the music.

When researchers played this game with 4-year-olds, they subsequently tested the children’s spontaneous willingness to help other kids. Compared with children who had “awakened the frogs” with a non-musical version of the activity, the music-makers were more likely to help out a struggling peer (Kirschner and Tomasello 2010).

4. Preschool games that reward attention and self-control

To get along well with others, children need to develop focus, attention skills, and the ability to restrain their impulses. The preschool years are an important time to learn such self-control, and we can help them do it.

Traditional games like “Simon Says” and “Red light, Green light” give youngsters practice in following directions and regulating their own behavior. For more information, see the research-tested games described in my article about teaching self-control. For additional advice about the socialization of young children, see this Parenting Science article about preschool social skills.

For more information, see the research-tested games described in my article about teaching self-control. For additional advice about the socialization of young children, see this Parenting Science article about preschool social skills.

5. Group games of dramatic, pretend play

To get along with others, kids need to be able to calm themselves down when something upsetting happens. They need to learn to keep their cool. And one promising way for kids to hone these skills is to engage in dramatic make-believe with others.

To try this approach, lead young children in games of joint make-believe, like

- pretending to be a family of non-human animals,

- dressing up as chefs and pretending to bake a cake together, or

- taking turns pretending to be statues (and having peers pose the statues in various ways).

In a randomized experiment of preschoolers from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, Thalia Goldstein and Matthew Lerner found evidence that these social skills activities helped children develop better emotional self-regulation (Goldstein and Lerner 2018). After 8 weeks of teacher-led play, kids assigned to play group games of dramatic, pretend play improved more than did children assigned to alternative social skills activities, like playing together with blocks.

After 8 weeks of teacher-led play, kids assigned to play group games of dramatic, pretend play improved more than did children assigned to alternative social skills activities, like playing together with blocks.

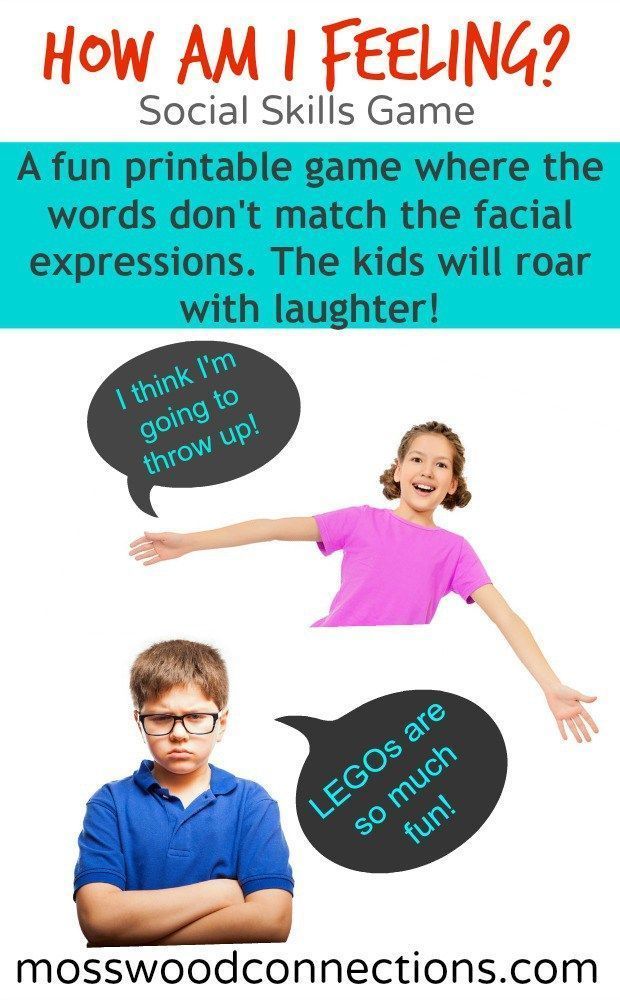

6. “Emotion charades” for young children

In this game, one player acts out a certain emotion, and the other players must guess which feeling is being portrayed. In effect, it’s simple version of charades for the very young.

Is it helpful? At the very least, it’s a way to motivate young children to think about and discuss emotions. And the game has been included (along with several other social skills activities) in a preschool program developed by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In a small experimental study, the program, called the “Kindness Curriculum,” was linked with successful outcomes: Compared with kids in a control group, graduates of the “Kindness Curriculum” experienced greater improvements in teacher-rated social competence (Flook et al 2015).

7. Drills that help kids read facial expressions

People who are good at interpreting facial expressions can better anticipate what others will do. They are also more “prosocial,” or helpful towards others.

Experiments suggest that kids can improve their face-reading skills with practice. For more information, see these Parenting Science social skills activities for teaching kids about faces.

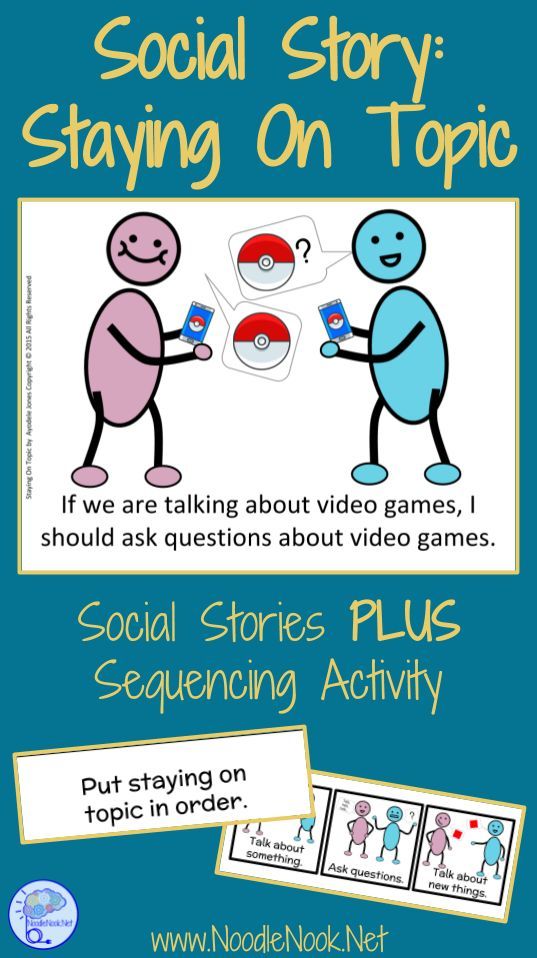

8. Checker stack: A game for keeping up a two-way conversation

Some kids, including those with autism spectrum disorders, have difficulty maintaining a conversation with peers. Dr. Susan Williams White has developed a number of social skills activities to help them, including Checker Stack, a game that requires kids to take turns and stay on topic.

To play this two-player game, you need only a set of stackable tokens — like checkers or poker chips — and an adult or peer group to help judge the relevance of each player’s contributions.

The game begins when Player One sets down a token and says something to initiate a conversation. Next, Player Two responds with an appropriate utterance, and places another checker on top of the first one.

Next, Player Two responds with an appropriate utterance, and places another checker on top of the first one.

The players keep taking turns to advance the conversation. How long can they sustain it? How tall can their stack become? When a player says something irrelevant or off-topic, the conversational flow is broken and the game is over (White 2011).

9. Passing the ball: A game for honing group communication skills

Here is another activity recommended by Dr. Susan Williams White — a game where players form a circle, and take turns contributing to a group conversation.

The game begins with a player who starts the chat, and then tosses a ball to someone else in the circle. Next, the recipient responds with an appropriate, relevant contribution of his or her own, and tosses the ball to another child. And so on.

To play successfully, kids must attend to whoever is speaking, and make eye contact during the exchange of the ball.

White advises that you participate in the game yourself, and, if you notice that one of the kids isn’t getting the opportunity to contribute, you can request that you receive the ball next. Then you can complete your turn by tossing the ball to the child who was left out (White 2011).

Then you can complete your turn by tossing the ball to the child who was left out (White 2011).

You can find this game, Checker Stack, and other social skills activities in White’s book, Social Skills Training for Children with Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism (see the references section below)

10. Cooperative games

There are many kinds of cooperative games. Some are more sedentary, like the many cooperative board games being sold today. Others are active or physical, like the games “Islands” and “Timeball” invented by William Haskell, and tested on older elementary school students (Street et al 2004).

In one study, researchers found that playing these games over a period of 12 weeks led to small but noticeable improvements in “prosocial” behavior — being kind and helpful towards others (Street et al 2004).

“Islands”

To play “Islands” you need a bunch of young children and some hula hoops — about one hoop for every three kids in the class. Then you spread the hoops out on the ground, and let the kids mill around them. When you whistle, every child must step inside a hoop, and each hoop must contain at least three kids. Children will have to cooperate — and hold onto each other — to fit inside a hoop.

Then you spread the hoops out on the ground, and let the kids mill around them. When you whistle, every child must step inside a hoop, and each hoop must contain at least three kids. Children will have to cooperate — and hold onto each other — to fit inside a hoop.

“Timeball”

In this game, kids spread out in an open space, each standing with his or her feet together. One child is given a ball. Then this child passes the ball to someone else, and immediately sits down. The second child repeats the exercise, until all kids are seated.

The catch? The object of the game is to get everyone seated as quickly as possible, and the ball must never touch the ground, so kids need to toss the ball with care. Moreover, when deciding where to pass the ball next, they need to consider how difficult it will be for other kids on subsequent turns: If kids pass the ball in a pattern that leaves some children “stranded” at a distance — making it harder to toss the ball without dropping it — the whole team will lose. So kids will likely want to discuss tactics.

So kids will likely want to discuss tactics.

What are the effects of these and other games?

The most obvious benefit is that they encourage kids to act, well…nicer. In one study, researchers found that playing games like “Islands” and “Timeball,” over a period of 12 weeks led to small but noticeable improvements in children’s prosocial behavior. They tended to show more kindness, helpfulness, and empathy (Street et al 2004).

But other research suggests this could be the tip of the iceberg. For example, studies show that successful experiences with cooperation encourage children to continue the trend: If you cooperate with me today, I’m more likely to cooperate with you tomorrow (Blake et al 2015; Keil et al 2017). So it seems likely that cooperative games could serve as a kind of “ally-making” tool between players.

And it also appears that certain types of cooperative games could help children develop their ability to persuade and convince others with well-reasoned arguments.

“Match animals to the right habitat”

In an experimental study of 5- and 7-year-olds, kids had to work in pairs on a sorting task. They had to match different animal species with an appropriate habit, and explain their decisions.

Half the kids were randomly assigned to a cooperative version of this game, where both players worked together as a team. The remaining children played the game competitively. And what happened? The kids who played the cooperative game offered more justification for their ideas. They were also more likely to produce arguments that considered both sides of the question (Domberg et al 2018).

You can read more about the study — and the benefits of cooperative games — in this Parenting Science article.

11. Cooperative construction

Another form of play that promotes cooperation is team construction. When kids create something together with blocks, they must communicate, negotiate, and coordinate. Do such social skills activities make a difference?

It makes sense intuitively, and there is scientific evidence that a specialized program of cooperative construction therapy — called “LEGO®-based therapy” — can help kids who need extra support to develop their social communication skills (Owens et al 2008).

In a recent review of published studies, researchers concluded that “LEGO®-based therapy” is a “promising treatment” for enhancing social interactions with kids on the ASD spectrum (Narzisi et al 2020). If you had a child with special needs, it’s worth asking your pediatrician about this form of therapy.

I haven’t found any rigorous experiments on the subject, but it makes sense that cooperative gardening could help kids hone social skills, and observational research supports the idea.

Kids tend to improve their social competence when they engage in community-based or school-based gardening (Ozer et al 2007; Block et al 2012; Gibbs et al 2013; Pollin and Retzlaff-Fürst 2021).

What sorts of things can children do in the garden? Take a cue from a recent study of cooperative gardening in 6th graders. The kids were assigned to groups, and each group was given the responsibility for tending a specific garden bed. In addition, kids were asked to identify different plants, document plant growth, conduct soil tests, and make observations of snails (Pollin and Retzlaff-Fürst 2021).

13. Story-based discussions about emotion

Here’s a social skills activity you can try just about anywhere: Read a story with emotional content, and have kids talk about it afterwards.

Why did the main character get angry? What kinds of things make you get angry? What do you do to cool off? When kids participate in group conversations about emotion, they reflect on their own experiences, and learn about individual differences in the way people react to the world. And that understanding may help kids develop their “mind-reading” abilities.

In one study, 7-year-old school children met twice a week to discuss an emotion featured in a brief story. Sometimes their teachers encouraged them to talk about recognizing the signs of a given emotion. In other sessions, the kids discussed what causes emotions, or shared ideas about how to handle negative emotions (“When I feel sad, I play video games,” or “I feel better when my mother hugs me”).

After two months, participants outperformed peers in a control group, showing significant improvements in their understanding of emotion. They also scored higher on tests of empathy and “theory of mind” — the ability to reason about other people’s thoughts and beliefs (Ornaghi et al 2014).

They also scored higher on tests of empathy and “theory of mind” — the ability to reason about other people’s thoughts and beliefs (Ornaghi et al 2014).

14. Classic charades for older kids and teens

We’ve already mentioned “Emotion Charades” for young children. The traditional or classic version of the game is also an excellent activity for honing social skills among older kids.

Consider why. In the traditional game, a player draws a slip of paper from a container and silently reads what is written there — a phrase that describes a situation (like “walking the dog”) or that names a famous book, film, song, or television show. Then, through pantomime, the player tries to convey this phrase to his or her unknowing team-mates.

What gestures are most likely to communicate the crucial information? To perform an effective pantomime, you need to be good at perspective-taking, or imagining what viewers need to see in order to guess the answer. You also have to stay focused on the rules, and refrain from talking.

And if you are one of the players who must guess the answer? Once again, mind-reading is important. In fact, there is evidence that watching charades switches our brains into “mind-reading mode.”

During a study using fMRI scans, players observing gestures experienced enhanced activity in the temporo-parietal junction, a part of the brain associated with reflecting on the mental states of other people (Schippers et al 2009).

It seems, then, that charades encourages kids to think about other perspectives, and fine-tune their nonverbal communication skills.

15. Team athletics that feature training in good sportsmanship

Research suggests that team athletics can function as effective social skills activities — if adults model the right behavior, and actively teach kids to be good sports.

In one study, elementary school students who received explicit instruction in good sportsmanship showed greater leadership and conflict-resolution skills than did their control group peers (Sharpe et al 1995).

In another study, researchers found that adolescents displayed better social skills if their athletic coaches took a democratic approach to leadership, and offered lots of social support and positive feedback. When kids perceived the coach to be autocratic, they were less likely to report growth in social competence (de Albuquerque et al 2021).

And — in a variety of studies — researchers have found that players are more likely to stay motivated and positive if their coaches avoid authoritarian tactics, like intimidation, threats, and the manipulative use of rewards (e.g., Sevil-Serrano et al 2021).

So what’s a good way to ensure that kids learn the right lessons from team sports?

It sounds like adults need to allow kids to participate in decisions about a team’s goals. They also need to maintain a pleasant, emotionally supportive relationship with athletes, and motivate kids with positive comments about their successes. And it makes sense to actively instruct kids on the principles of good sportsmanship, including

- Being a good winner (not bragging; showing respect for the losing team)

- Being a good loser (congratulating the winner; not blaming others for a loss)

- Showing respect to other players and to the referee

- Showing encouragement and offering help to less skillful players

- Resolving conflicts without running to the teacher

During a game, we should give kids the chance to put these principles into action before we swoop in. And when the game is over, we should give kids feedback on their good sportsmanship.

And when the game is over, we should give kids feedback on their good sportsmanship.

These become increasingly important as kids get older, and they require more than empathy and good manners. They also require more than native “smarts.”

Studies indicate that most people — regardless of IQ — fall prey to “myside bias” — the tendency to evaluate neutral evidence in favor of one’s personal interests (Stanovich et al 2013).

But that doesn’t mean we can’t fight this tendency. People become less prone to myside bias as a function of the years they spend in higher education, even after controlling for age and cognitive ability (Toplak and Stanovich 2003). So it seems likely that kids will benefit if we expose them to diverse viewpoints, debate, and the tools of critical thinking.

One classic approach is to assign students to take turns advocating both sides of a given debate. Not only will kids practice perspective-taking, they will hone critical thinking skills. For more information, see my article about training kids to engage in formal, disciplined debate.

Researchers Geoff Kauffman and Anna Flanagan perceive a problem with many “consciousness-raising” social skills activities: They’re too preachy, and that tends to turn people off.

So Kauffman and Flanagan recommend a more subtle approach, one that embeds the social message in a fun, lighthearted game. To date, Flanagan has created two such games.

The first is a card game called the Resonym Awkward Moment Card Game, a party game that requires players to choose solutions to thorny social problems.

It has been tested on kids as young as 11 years old, and found to improve players’ perspective-taking skills. Compared to students in a control group, kids who played this game showed subsequent improvements in their ability to imagine another person’s perspective (Kaufman and Flanagan 2015).

They were also more likely to reject social biases, and imagine females pursuing careers in science. In addition, they showed more interest in confronting detrimental social stereotypes (Kaufman and Flanagan 2015).

The second game, called the Buffalo The Name Dropping Game, is intended for ages 14 and up.

Buffalo asks players to think of real or fictional examples of people who fit a random combination of descriptors (like tattooed grandparent, misunderstood vampire, or Asian descent comedian).

After playing this game, high school students showed increased motivation to recognize and check their social biases, agreeing more strongly with statements like “I attempt to act in non-prejudiced ways toward people from other social groups because it is personally important to me” (Kaufman and Flanagan 2015).

Both the Resonym Awkward Moment Card Game and Buffalo The Name Dropping Game are available from Amazon. If you purchase them through these links, a small portion of the proceeds will benefit this website.

For more information about boosting social competence, see my evidence-based tips for fostering friendships, teaching empathy, and encouraging kindness. In addition, check out my article about promoting preschool social skills, as well as my article about the potential benefits of playing prosocial video games.

In addition, check out my article about promoting preschool social skills, as well as my article about the potential benefits of playing prosocial video games.

Bakeman R, Adamson LB, Konner MJ, and Barr RG. 1990. !Kung infancy: The social context of object exploration. Child Development 61: 794-809.

Blake PR, Rand DG, Tingley D, Warneken F. 2015. The shadow of the future promotes cooperation in a repeated prisoner’s dilemma for children. Sci Rep. 5:14559.

Block K, Gibbs L, Staiger PK, Gold L, Johnson B, Macfarlane S, Long C, Townsend M. 2012. Growing community: the impact of the Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden Program on the social and learning environment in primary schools. Health Educ Behav. 39(4):419-32.

Cortes Barragan R and Dweck CS. 2014. Rethinking natural altruism: simple reciprocal interactions trigger children’s benevolence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.111(48):17071-4.

de Albuquerque LR, Scheeren EM, Vagetti GC, de Oliveira V. 2021. Influence of the Coach’s Method and Leadership Profile on the Positive Development of Young Players in Team Sports. J Sports Sci Med. 20(1):9-16.

J Sports Sci Med. 20(1):9-16.

Domberg A, Köymen B, Tomasello M. 2018. Children’s reasoning with peers in cooperative and competitive contexts. Br J Dev Psychol. 36(1):64-77.

Flook L., Goldberg S.B., Pinger L., and Davidson R.J. 2015. Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based Kindness Curriculum. Dev Psychol. 51(1):44-51.

Gibbs L, Staiger PK, Townsend M, Macfarlane S, Gold L, Block K, Johnson B, Kulas J, Waters E. 2013. Methodology for the evaluation of the Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden program. Health Promot J Austr. 24(1):32-43.

Goldstein TR and Lerner MD. 2018. Dramatic pretend play games uniquely improve emotional control in young children. Dev Sci. 21(4):e12603.

Kaufman G and Flanagan M. 2015. A psychologically “embedded” approach to designing games for prosocial causes. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace,9(3), article 1.

Keil J, Michel A, Sticca F, Leipold K, Klein AM, Sierau S, von Klitzing K, White LO. 2017. The Pizzagame: A virtual public goods game to assess cooperative behavior in children and adolescents. Behav Res Methods. 49(4):1432-1443.

2017. The Pizzagame: A virtual public goods game to assess cooperative behavior in children and adolescents. Behav Res Methods. 49(4):1432-1443.

Kirschner S and Tomasello M. 2010. Joint music making promotes prosocial behavior in 4-year-old children. Evolution and Human Behavior 31(5): 354-364.

Lancy D. 2012. Ethnographic perspectives on cultural transmission/acquisition. Paper prepared for School of Advanced Research, Santa Fe, Multiple Perspectives on the Evolution of Childhood. November 4-8, 2012.

Lancy D. 2008. The anthropology of childhood: Cherubs, chattel and changelings. Cambridge University Press.

Legoff DB and Sherman M. 2006. Long-term outcome of social skills intervention based on interactive LEGO play. Autism. 10(4):317-29.

Ozer EJ. 2007. The effects of school gardens on students and schools: conceptualization and considerations for maximizing healthy development. Health Educ Behav. 34(6):846-63.

Pellegrini AD, Dupuis D, and Smith PK. 2007. Play in evolution and development. Developmental Review 27: 261-276.

2007. Play in evolution and development. Developmental Review 27: 261-276.

Pellegrini AD and Smith PK. 2005. The nature of play: Great apes and humans. New York: Guilford.

Pollin S, Retzlaff-Fürst C. 2021. The School Garden: A Social and Emotional Place. Front Psychol. 12:567720.

Sevil-Serrano J, Abós Á, Diloy-Peña S, Egea PL, García-González L. 2021. The Influence of the Coach’s Autonomy Support and Controlling Behaviours on Motivation and Sport Commitment of Youth Soccer Players. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(16):8699.

de Albuquerque LR, Scheeren EM, Vagetti GC, de Oliveira V. 2021. Influence of the Coach’s Method and Leadership Profile on the Positive Development of Young Players in Team Sports. J Sports Sci Med. 20(1):9-16.

Sharpe T, Brown M and Crider K. 1995. The effects of a sportsmanship curriculum intervention on generalized positive social behavior of urban elementary students. Journal of applied behavior analysis 28(4): 401-416.

Spinka, M. , Newberry, RC, and Bekoff, M. 2001. Mammalian play: Training for the unexpected. Quarterly Review of Biology 76: 141-16.

, Newberry, RC, and Bekoff, M. 2001. Mammalian play: Training for the unexpected. Quarterly Review of Biology 76: 141-16.

Stanovich KE, West RF, Toplak ME. 2013. Myside Bias, Rational Thinking, and Intelligence. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2(4): 259-264.

Street H, Hoppe D, and Ma T. 2004. The Game Factory: Using Cooperative Games to Promote Pro-social Behaviour Among Children. Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology. 4:997-109.

Teacher’s College, Columbia University. 1999. Conflict resolution for preschoolers. TC Media Center website. Accessed on 9/28/2015 at http://www.tc.columbia.edu/news.htm?articleID=4023.

Weiss MJ and Harris SL. 2001. Teaching social skills to people with autism. Behav Modif. 25(5):785-802.

White SW. 2011. Social Skills Training for Children with Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism. New York: The Guilford Press.

Portions of this article are adapted from an earlier work about social skills activities by the same author.

Image credits for “Social skills activities”:

image of children’s faces in a circle by Wavebreakmedia / istock

Image of preschoolers with musical instruments by Liderina / shutterstock

Content of “Social Skills Activities” last modified 9/2021

Social Skills Training for Kids: Top Resources for Teachers

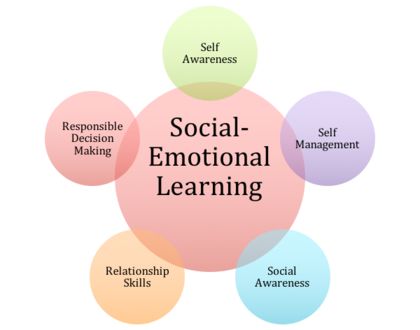

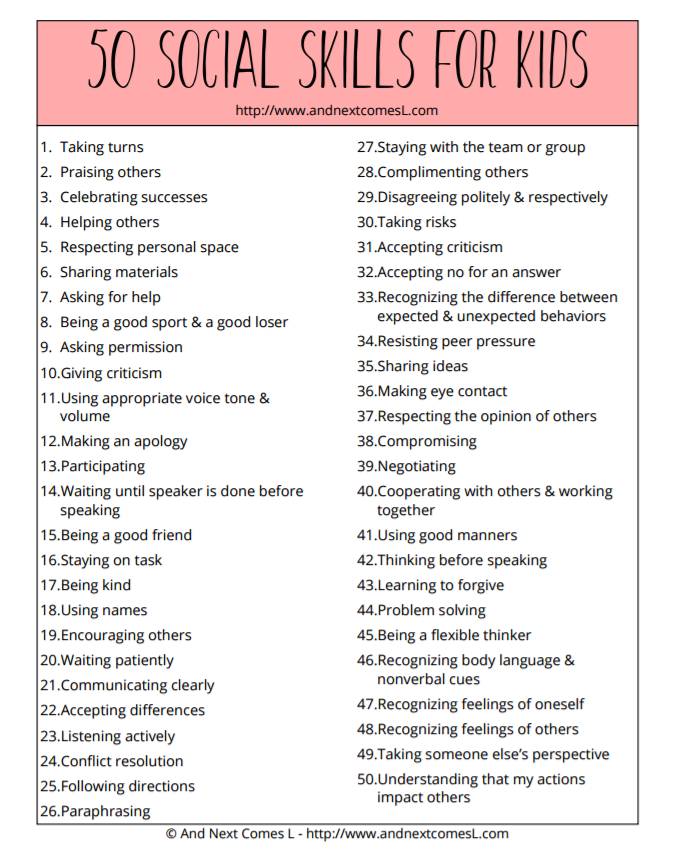

School is a place where children and adolescents go to become educated, academically and socially.

Learning how to interact with other people, make friends, and foster cooperation are all social skills that are taught by facilitating students’ interactions with each other.

Even though children gain social skills through naturally interacting with others, since most of these interactions take place at school, it is essential that teachers master the elements of social skills training to facilitate social development in their students.

This article will provide guidance on social skills training for teachers and resources to help integrate social skills training for all stages (i. e., toddlers, young children, and teenagers). Also included are lesson plans to help break down social skills education.

e., toddlers, young children, and teenagers). Also included are lesson plans to help break down social skills education.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will enhance your ability to understand and work with your emotions and give you the tools to foster the emotional intelligence of your clients or students.

This Article Contains:

- How Do Social Skills Develop?

- Fostering Social Skills in Toddlers

- 3 Important Social Skills for Teenagers

- Teaching Social Skills 101

- Social Skills Training for Kids: 3 Games & Activities

- 4 Online Games & Board Games

- Resources for Teachers: 3 Lesson Plans & Tips

- PositivePsychology.com’s Helpful Tools

- A Take-Home Message

- References

How Do Social Skills Develop?

Similar to riding a bike, social skills cannot be developed without practice. Arguably, the abilities to understand and consider another’s worldview are two of the most fundamental pieces of social interaction.

Arguably, the abilities to understand and consider another’s worldview are two of the most fundamental pieces of social interaction.

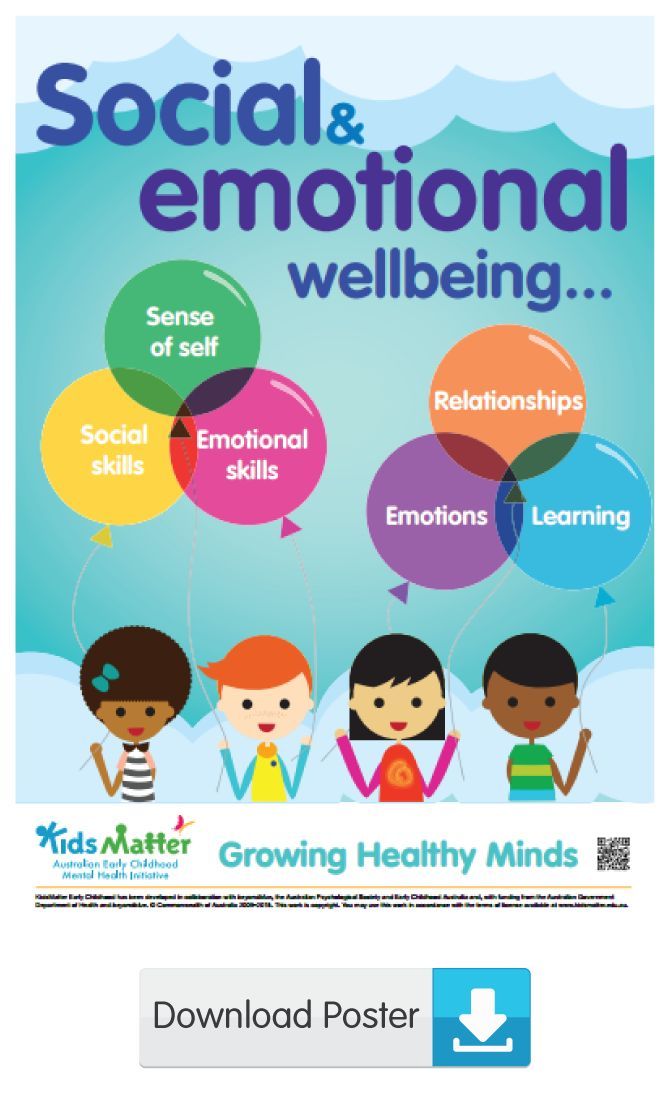

Theory of mind, which develops in a child’s preschool years, refers to the ability to understand that another individual’s perspective differs from yours (Moll & Meltzoff, 2011). The development of theory of mind takes place throughout childhood in a predictable manner, as outlined below (Lowry, 2015; Ruhl, 2020):

- Wanting:

Understanding that people do not always want the same things and act in a variety ways to get the things they want. - Thinking:

Understanding that people may have differing beliefs about the same event or topic. - Knowledge:

Recognizing that everyone’s access to knowledge is different, and if they have not seen it, they may need additional context to understand. - False beliefs:

Recognizing that different people may have varying beliefs that differ from reality.

- Hidden feelings:

Understanding that people can hide their emotions and feel a different emotion than the one they are displaying.

The development of these theory-of-mind concepts eventually leads to children becoming better at another key social skill: perspective taking.

Perspective taking refers to an individual’s ability to understand both visual (viewpoint) and perceptual (understanding) situations (Duffy, 2019). Perspective taking develops over the course of the preschool years and continues throughout childhood and adolescence.

Think of a conversation or experience when another person was incredibly rigid about their beliefs and lacked interest in hearing about your experiences. That individual may not have developed the necessary skills to engage in perspective taking and may lack flexibility in accepting that others’ beliefs may be different from their own.

Fostering Social Skills in Toddlers

If you are a parent or educator, you understand that it’s difficult to get younger children, especially toddlers, to ‘tune in,’ as development can be so varied across different individuals.

When considering strategies to help foster social skills in toddlers, you should not underestimate the significance of pretend play and role-play.

For example, if your child is playing doctor and wants you to play with them, it is important to stay ‘in character’ and take off the parent or teacher hat while you are playing with them. This will allow children to become comfortable playing different roles and developing a variety of skills in everyday life.

A few other strategies for caregivers and early childhood educators to foster social skills in toddlers include:

- Follow the toddler’s lead

Start by observing the toddler while they are playing. Get onto their level (crouch or sit down) and join the play by copying their actions. Slowly, add more as the play develops. - Put your child’s perspective into words

Even if your toddler is not talking yet, putting their actions/feelings or your own into words can be helpful in developing perspective taking. It can also encourage them to use more language when communicating, rather than just actions or words.

It can also encourage them to use more language when communicating, rather than just actions or words. - Use picture books to help discuss feelings

When learning about feelings, having pictures that display the feelings your toddler might be experiencing is helpful in having them visualize what these feelings look like. Providing dialogue such as “Oh, Pig’s mouth is pointed downward, and he has a tear. He seems sad,” can also help toddlers understand what emotions look like.

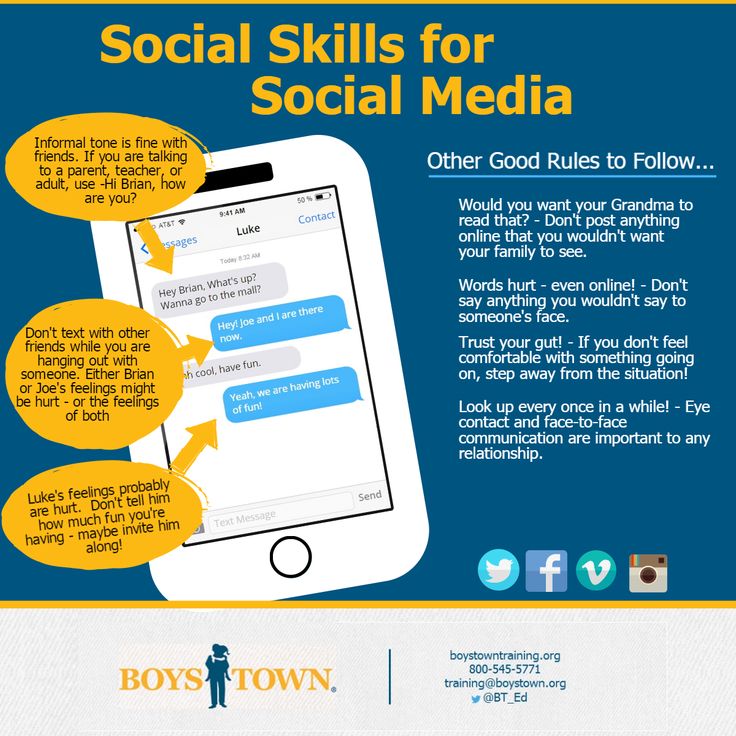

3 Important Social Skills for Teenagers

In today’s technology-driven society, developing social skills can be more difficult for young adults and teenagers. Considering that a lot of their social activity is powered by devices, there are fewer opportunities for them to engage in meaningful in-person interactions.

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Children’s capacity to achieve goals, work effectively with others and manage emotions will be essential to meet the challenges of the 21st century” (OECD, 2015). Social skills that apply to goal attainment, cooperation, and emotional awareness include:

Social skills that apply to goal attainment, cooperation, and emotional awareness include:

1. Active listening

Active listening is a type of listening that focuses on hearing the words another person is saying as well as recognizing the emotions that come out through their nonverbal behavior.

A good activity to practice active listening with adolescents and teenagers is to ask all participants to sit in a circle. The facilitator then chooses one participant to tell a story. After three to five sentences, the teacher says ‘stop’ and chooses another student to continue the story. This person now has to repeat the last sentence the previous person said and continue making up the story.

2. Assertiveness

Assertive communication is characterized by the ability to express one’s opinions, feelings, or attitudes while still respecting the perspectives of others.

The most important piece of teaching assertiveness is to assure teens it’s okay to claim their rights and express their opinions and feelings, especially when saying “no” respectfully.

3. Self-awareness

Being aware of one’s emotions is an important component of self-awareness. Understanding why they feel a certain way and their emotions in specific situations is an essential part of the development of teenagers’ empathy.

Empathy not only helps teenagers understand the emotions others are feeling, but also allows them to understand when they are feeling specific emotions and implement specific coping strategies to help them.

Teaching Social Skills 101

Engaging in social skills training can be overwhelming, especially as a teacher or caregiver, as there are so many other things to attend to.

A specific challenge that teachers face when integrating social-emotional education is integrating activities and social education into the daily curriculum.

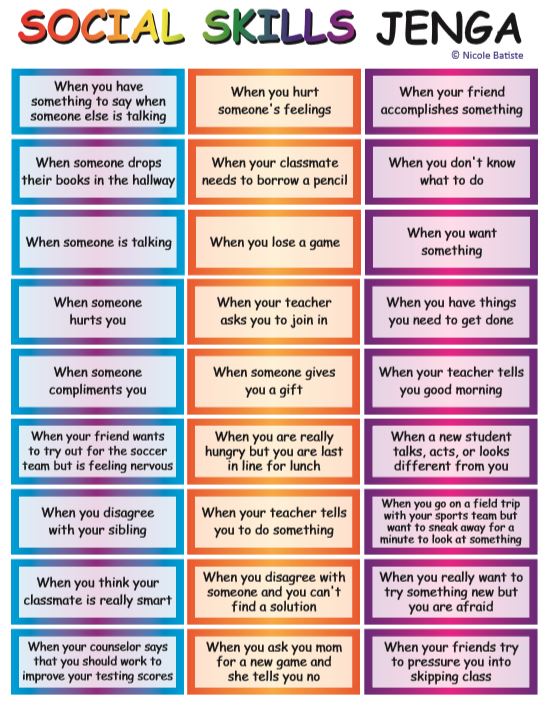

The easiest way to do this is through short, simple activities and games that require little preparation and can be quickly set up during down times and transitions. Below, we have provided several options for integrating social skills education, whether you are a teacher, therapist, parent, or caregiver looking to enhance your child’s social skills.

Below, we have provided several options for integrating social skills education, whether you are a teacher, therapist, parent, or caregiver looking to enhance your child’s social skills.

Social Skills Training for Kids: 3 Games & Activities

Activities that can be played across all age groups to promote social skills education include:

1. Charades

Charades is a simple way for children to understand perspective taking, as participants are asked to write things from different categories (i.e., movies, television shows, or games).

Participants then act out the thing they select using only gestures, and other players have to guess. Since participants are communicating using only gestures, the other players have to consider their perspectives when guessing, as the person who is acting out the thing may have a different understanding or experience than they do.

2. Passing the ball

The game begins with a player starting a conversation. The teacher can give a topic to start with or allow the players to choose. It is recommended that the teacher use a timer to help time each player’s contribution so they do not talk for too long (approximately 20–30 seconds).

It is recommended that the teacher use a timer to help time each player’s contribution so they do not talk for too long (approximately 20–30 seconds).

After the player who is holding the ball starts the conversation, they throw the ball to another person, who chimes in with a related contribution. Players must maintain eye contact with the person they are speaking to during the exchange (White, 2011).

3. Checker stack

This is a three-player game. To play this game, you need a set of stackable tokens (i.e., checkers, poker chips, coins) and a judge. The judge can be an adult or another peer, and they will judge each player’s contribution.

The game begins when the first player sets down a token and says something to start a conversation. The second player responds and stacks another token on top. The players keep taking turns stacking and talking, with the judge providing feedback when necessary. The game ends when one player says something irrelevant or off-topic, or when the tower falls down (White, 2011).

To help participants understand what this looks like, we recommend that the teacher model a round of the game, using two students as an example so participants can understand how the game is played. Participants should also rotate being the judge to practice perspective taking.

4 Online Games & Board Games

Turn taking and role-play are two skills promoted through games that can contribute to the development of social skills across all ages. Games that can help promote these skills include:

1. Apples to Apples Jr.

This game is probably one of the most natural ways to practice perspective taking for children.

At the start of the game, each player is given ‘red apple’ cards that have descriptions written on them. Each player takes turns playing the judge and selects a ‘green apple’ card, which has a one-word characteristic on it such as “amazing” or “scary.”

All the other players are then required to choose a description that they feel matches the ‘green apple’ card. Once all the ‘red apple’ cards are on the table, each player has the opportunity to convince the judge why their selection is best.

Once all the ‘red apple’ cards are on the table, each player has the opportunity to convince the judge why their selection is best.

This activity gives children the opportunity to practice perspective taking, as they have to convince each other in a socially acceptable way why they think their card is a good match.

Available on Amazon.

2. Hall of Heroes

Hall of Heroes is marketed as an online middle school game where students encounter real-world social situations that they will face in middle school (e.g., bullying, peer pressure, and making new friends).

Players can choose their character and build their skills during gameplay. By providing a virtual setting where students can make mistakes and examine the impact of their decisions, young adults will be able to see the consequences of their decisions.

Characters in the game also come back with assertive retorts; for example, when faced with a situation where another student is told they cannot sit at the lunch table, one character says “Hey, didn’t I just see you come in with another kid? Did you just ditch them to come over here?”

This kind of dialogue allows young adults who are struggling to be assertive to adopt the strategies and words the characters are using when dealing with difficult situations in their own lives.

Available on Centervention. A 30-day free trial is available for educators.

3. My Feelings Game

This board game is targeted for children between the ages of 4 and 11. The goal of the game is to encourage children to recognize common feelings in themselves and others.

The game has 280 everyday situations and 7 characters who are aptly named with the most common feelings that children experience (i.e., anger, happiness).

Children are asked to do a variety of tasks that include identifying their emotions on pictures of faces, adding context to a list of typical experiences they have with a particular emotion, and acting out specific scenarios.

This provides an opportunity for children to further examine the perspectives of others. The characters provide scenarios that make them feel certain feelings (i.e., “I am happy when my mom gives me a treat”), and then players expand on things that make them happy, combining emotional awareness and perspective taking. The game also includes movement breaks so the children can move around while they are playing.

The game also includes movement breaks so the children can move around while they are playing.

Available on Sensational Learners.

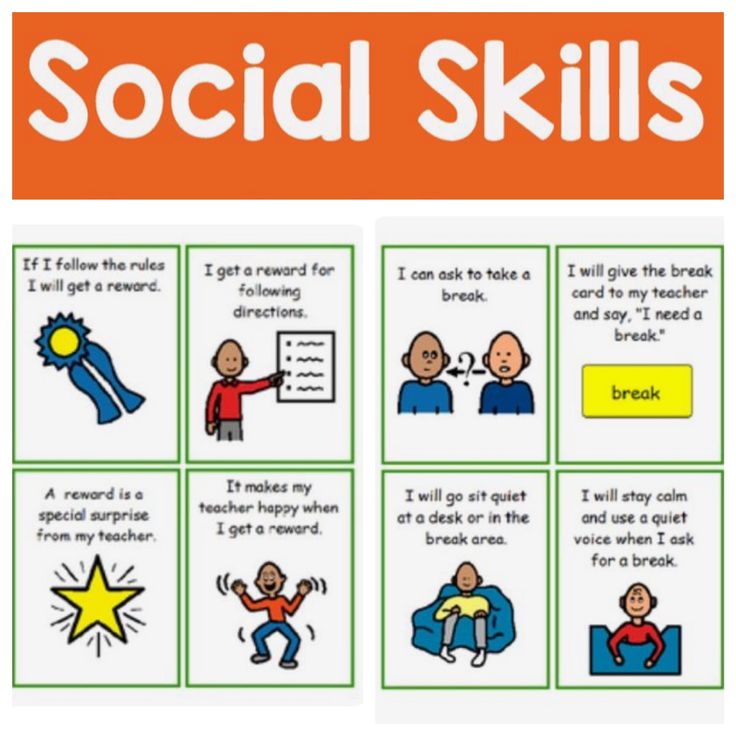

4. TeachTown Social Skills

TeachTown Social Skills guides younger children (ages 4–12) through an interactive curriculum with the goal of teaching socially appropriate behaviors.

TeachTown is designed for children with special needs, as the game targets five behavioral domains:

- Following the rules

- Good communication

- Coping & self-regulation

- Friendship

- Interpersonal skills

Each of the domains contains 10 target social behaviors that are highlighted through videos, social skills worksheets, and lesson plans to help children understand appropriate social behaviors and responses to different situations.

The behavioral domains specifically target areas where these children struggle, and through the use of social storytelling and modeling, they help educate children in real time how to react to specific situations.

Each lesson plan can also be integrated into therapeutic interventions these children might already be receiving, which helps tie in social skills education to both school and therapeutic settings.

Available on TeachTown.

Resources for Teachers: 3 Lesson Plans & Tips

One of the major challenges teachers face when integrating social and emotional content across the curriculum is the ability to have materials they can quickly integrate in the classroom.

Even though lesson and course planning is an integral part of a teacher’s preparation for learning, the classroom is a fluid space where things happen rapidly without warning.

To help accommodate this, we have provided lesson plans and activities that you can implement on the fly, specifically in difficult social situations that may arise as your students go through their daily activities. Similar to the interactive activities above, these lesson plans can be adapted for use across all ages.

1.

Wanted: Friend

Wanted: FriendIn this activity, students create a “wanted” poster for a friend. Students can use the template provided or make their own poster.

This activity helps students identify qualities that are present in a good friend and examine whether those qualities are present in themselves.

2. How to apologize

Part of being a good friend and colleague is learning how to admit when you have done something wrong. This lesson plan provides steps for crafting a good apology and role-playing activities for students to practice saying sorry in different situations.

3. Understanding empathy

Putting yourself in another’s shoes and understanding another’s feelings are important parts of developing social skills. This lesson helps students understand what empathy is and promotes strategies to use empathy in their everyday lives.

PositivePsychology.com’s Helpful Tools

PositivePsychology.com provides several resources that can be adapted for teachers aiming to help their students develop social skills.

This article lists recommended empathy books to help cultivate compassion and empathy in your students. It also provides specific books for adults and teachers that are relevant to their everyday lives.

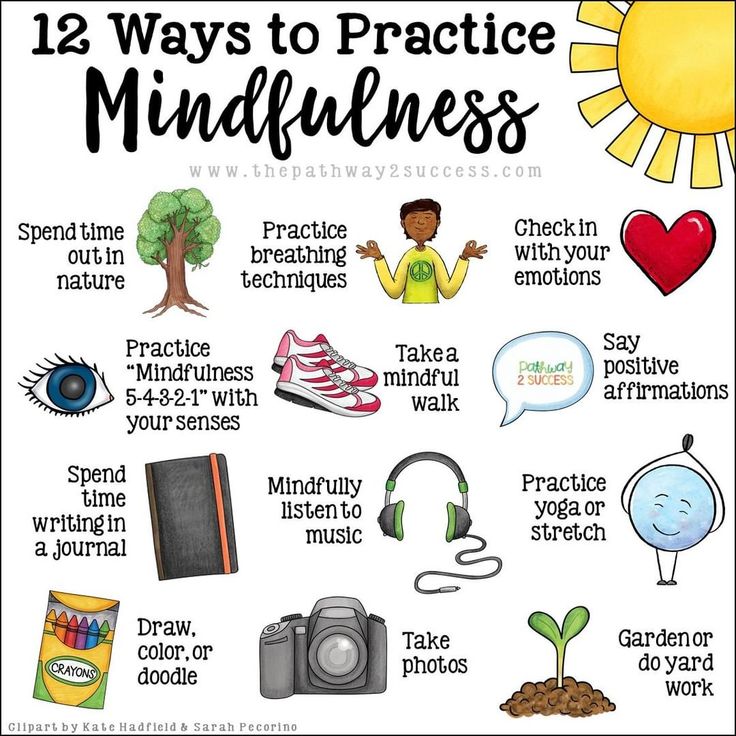

Mindfulness can be an important component for adults, teenagers, and children in practicing self-reflection, which ultimately leads to an increased ability to display empathy and perspective taking. These Mindfulness Worksheets can be used by teachers and other practitioners when practicing mindfulness with their students and for themselves.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others communicate better, this collection contains 17 validated positive communication tools for practitioners. Use them to help others improve their communication skills and form deeper and more positive relationships.

A Take-Home Message

While the development of social skills can be a difficult component to integrate into everyday teaching, it is an essential component of emotional and positive education that should be emphasized at every age.

Even if you do not have time to engage in specific social skill instruction daily, the strongest predictor of success is continued interaction. Ensuring that your students have time to interact in controlled and uncontrolled group settings and with peers of various ages is the best way to ensure that students have opportunities to practice social skills, specifically perspective taking and empathy.

We hope this article provided you with resources and ideas to use in your classroom or home. Please let us know if you have any strategies that are not listed here that could work for your fellow educators. Remember, we are all in this together, and sharing a resource or an idea could help another individual integrate more meaningful content into their classroom.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free.

- Duffy, J. (2019, June 2). The power of perspective taking. Psychology Today. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.

psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/the-power-personal-narrative/201906/the-power-perspective-taking

psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/the-power-personal-narrative/201906/the-power-perspective-taking - Lowry, L. (2015). “Tuning in” to others: How young children develop theory of mind. The Hanen Centre. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.dsrf.org/media/Developing%20theory%20of%20mind%20tuning%20into%20others.pdf

- Moll, H., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2011). Perspective-taking and its foundation in joint attention. In N. Eilan, H. Lerman, & J. Roessler (Eds.), Perception, causation, and objectivity. Issues in philosophy and psychology (pp. 286–304). Oxford University Press.

- OECD. (2015). OECD skills studies: Skills for social progress: The power of social and emotional skills. OECD Publishing.

- Ruhl, C. (2020). Theory of mind. Simply Psychology. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.simplypsychology.org/theory-of-mind.html

- White, S. W. (2011). Social skills training for children with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism.

Guilford Press.

Guilford Press.

How to teach a child with autism social skills?

01/17/15

Description

“I'm not asking my daughter to be a party star or socialite. I just want her to be happy and have her own friends. She is a wonderful child, and I hope one day others will notice it too.”

Lack of social skills development in autism spectrum disorders

In fact, many parents of children with autism will agree with this opinion regarding the social behavior of their children. They know that their child has a lot of great qualities that they could offer to others, but the nature of their disorders, and more specifically, their low level of socialization, often prevents them from making meaningful social contacts. This frustration is heightened when a parent knows that their child is desperate to make friends with others, but fails to make friends.

Often their failure is directly caused by ineffective programs and insufficient resources that are available for social skills training. For most children, social skills (such as "waiting in line", "conversation") are acquired easily and quickly. For children with autism, the process is much more complicated. While many children learn these socialization skills simply by participating in social situations, children with autism spectrum disorders often need to be taught in detail, and as early as possible. This article focuses on the underdevelopment of social skills in children with autism and describes a five-step model for learning to communicate, with particular emphasis on the relatively new and increasingly popular method of assistance - video modeling.

For most children, social skills (such as "waiting in line", "conversation") are acquired easily and quickly. For children with autism, the process is much more complicated. While many children learn these socialization skills simply by participating in social situations, children with autism spectrum disorders often need to be taught in detail, and as early as possible. This article focuses on the underdevelopment of social skills in children with autism and describes a five-step model for learning to communicate, with particular emphasis on the relatively new and increasingly popular method of assistance - video modeling.

Lack of interest in socializing or not knowing what to do

Social functioning disorder is a major feature of autism. A typical lack of development of social skills concerns starting a conversation, responding to an invitation to talk from other people, eye contact, reading other people's non-verbal cues, the ability to look at what is happening from the other's point of view. The reasons for the underdevelopment of these skills can range from congenital neurological disorders to the inability to acquire these skills (social isolation). Most importantly, the underdevelopment of these skills prevents a person from developing and maintaining meaningful and satisfying relationships. And although the lack of social skills becomes central to autism spectrum disorders, many such children do not receive sufficient training in these skills (Hume, Bellini, & Pratt, 2005).

The reasons for the underdevelopment of these skills can range from congenital neurological disorders to the inability to acquire these skills (social isolation). Most importantly, the underdevelopment of these skills prevents a person from developing and maintaining meaningful and satisfying relationships. And although the lack of social skills becomes central to autism spectrum disorders, many such children do not receive sufficient training in these skills (Hume, Bellini, & Pratt, 2005).

This is a worrying situation, especially given the fact that having a social disorder can lead to more debilitating problems such as poor school performance, communication and peer rejection, anxiety, depression, and other negative outcomes ( Bellini, 2006; Tantam, 2000; Welsh, Park, Widaman, & O'Neil, 2001). And having a personalized social skills plan is all the more relevant given that there are effective social skills teaching approaches that can reduce these challenges.

The long held belief that children with autism spectrum disorders lack the motivation to communicate is often wrong. Many children with autism actually want to communicate, however, these children often lack the skills to communicate effectively. One young man I worked with is a good example of this. Prior to my visit, the school administration informed me of his inappropriate behavior and his apparent "lack of interest" in interacting with other children. After Zak spent the morning in a separate classroom, he was allowed to have breakfast with the entire school population (at this time and in this place most of the problem behavior occurs). While he was eating his breakfast, a group of children to his right started talking about frogs. As soon as the conversation began, he immediately noticed it. And I noticed too. As he listened to the other children, he began to take off his shoes and then his socks. I remember thinking, "God, it's starting!" As soon as the second sock hit the floor, Zach threw his feet up on the table, looked at the group of children and exclaimed, “Look, webbed feet!” Other children (including myself) looked on in surprise.

Many children with autism actually want to communicate, however, these children often lack the skills to communicate effectively. One young man I worked with is a good example of this. Prior to my visit, the school administration informed me of his inappropriate behavior and his apparent "lack of interest" in interacting with other children. After Zak spent the morning in a separate classroom, he was allowed to have breakfast with the entire school population (at this time and in this place most of the problem behavior occurs). While he was eating his breakfast, a group of children to his right started talking about frogs. As soon as the conversation began, he immediately noticed it. And I noticed too. As he listened to the other children, he began to take off his shoes and then his socks. I remember thinking, "God, it's starting!" As soon as the second sock hit the floor, Zach threw his feet up on the table, looked at the group of children and exclaimed, “Look, webbed feet!” Other children (including myself) looked on in surprise. In this case, Zach has shown a desire to be part of a social situation, but he clearly lacks the necessary skills to do so in an appropriate and effective way.

In this case, Zach has shown a desire to be part of a social situation, but he clearly lacks the necessary skills to do so in an appropriate and effective way.

This lack of knowledge "how to do it" can also lead to social anxiety in some children. Many parents and teachers report that social situations tend to cause a lot of fear in their children. The way children with autism describe this anxiety is reminiscent of what many of us feel when we are forced to perform in front of an audience (increased heart rate, noticeable trembling, concentration problems, etc.). Not only the performance itself is stressful, the very thought of it is enough to create this painful feeling. Imagine how your life would be if every social interaction you make caused as much anxiety as giving a speech in front of a large group of people.

A typical defense for most of us is to reduce stress and anxiety by avoiding stressful situations. For children with autism spectrum disorders, this often leads to avoidance of all social situations and, as a result, the development of a lack of social skills. When a child constantly avoids communication, he does not give himself the opportunity to acquire social skills. For some children, this lack of skill leads to negative experiences with peers, peer rejection, isolation, anxiety, depression, drug use, and even suicidal thoughts. For others, it forms a pattern of total immersion in different hobbies and interests in solitude, and this pattern is often very difficult to change.

When a child constantly avoids communication, he does not give himself the opportunity to acquire social skills. For some children, this lack of skill leads to negative experiences with peers, peer rejection, isolation, anxiety, depression, drug use, and even suicidal thoughts. For others, it forms a pattern of total immersion in different hobbies and interests in solitude, and this pattern is often very difficult to change.

Five step model

1. Assess social interaction.

2. Distinguish between lack of skill acquisition and lack of application.

3. Select intervention strategies.

4. Intervention.

5. Evaluate and monitor progress.

This paragraph briefly describes my five-step model for teaching social skills (Bellini, 2006). Before starting to provide social skills training, it is important to start with a detailed assessment of their current level. When the assessment is completed, the next step is to recognize the difference between difficulties in acquiring skills and difficulties in applying them. Based on this information, we choose an intervention strategy. Once an intervention is initiated, it is essential to evaluate and modify the intervention strategy as needed. Although I use the word steps, it is important to note that this model is not completely linear. So, in real life, social skills training will not follow a rigid path from step one to step five. For example, quite often I notice an additional lack of social skills (stage one) while I have already begun the intervention process (stage four). In addition, I am constantly evaluating and changing the way I intervene as more information and data become available.

Based on this information, we choose an intervention strategy. Once an intervention is initiated, it is essential to evaluate and modify the intervention strategy as needed. Although I use the word steps, it is important to note that this model is not completely linear. So, in real life, social skills training will not follow a rigid path from step one to step five. For example, quite often I notice an additional lack of social skills (stage one) while I have already begun the intervention process (stage four). In addition, I am constantly evaluating and changing the way I intervene as more information and data become available.

Social Interaction Assessment

The first step in any social skills training program should be to conduct a complete assessment of the child's current level of social interaction. The purpose of this assessment is to answer a simple yet complex question: What prevents a child from starting and maintaining social relationships? For many children, the answer takes the form of a lack of certain social skills. For others, the cause is cruel and ignorant peers. For others, it's both.

For others, the cause is cruel and ignorant peers. For others, it's both.

Testing should show in detail both the strengths and weaknesses of the child in terms of his presence in society. Evaluation should be a combination of observation (both natural and structured), interviews (with parents, teachers on the playground, and the child themselves) and standard measurements (behavior tests and social skills measurements). I have developed the Autistic Social Skills Profile, which helps identify common social skill deficiencies in children with autism and tracks the progress a child is making in learning. Kathleen Quill (2000) also provides an excellent social skills checklist for parents and teachers in her book Do-Look-Listen-Say. It is important for the team that works with the child to determine the current level of interaction and effectively intervene in the area where the child needs help. For example, if testing indicates that the child is unable to have simple one-on-one conversations with others, then intervention should begin with that, and not with more complex levels of group communication. Or, if the research shows that the child does not know how to symbolically or even functionally use toys, then the correction will most likely begin with teaching play skills to learning social skills. Once the detailed social interaction assessment is complete, the team should determine whether the lack of skills is due to a lack of skill acquisition or skill application.

Or, if the research shows that the child does not know how to symbolically or even functionally use toys, then the correction will most likely begin with teaching play skills to learning social skills. Once the detailed social interaction assessment is complete, the team should determine whether the lack of skills is due to a lack of skill acquisition or skill application.

Distinguishing between insufficient mastery of skills and insufficient practice in their application

Following a full examination of the level of social interaction of the child and after determining the skills that we will teach him, it is necessary to understand whether the reason for the underdevelopment of social skills is a lack of acquisition or a lack of their application (Elliott & Gresham, 1991). Simply put, the success of your social skills training program depends on your ability to distinguish between the two.

Lack of skill acquisition refers to the absence of a particular skill or behaviour. For example, a child with autism may not know how to successfully join their peers' activities and therefore he or she is often unable to participate. If we want a child to join his peers, we must teach him to do so.

For example, a child with autism may not know how to successfully join their peers' activities and therefore he or she is often unable to participate. If we want a child to join his peers, we must teach him to do so.

Lack of skill application implies that the skill or behavior is familiar to the child but is not shown or used. In the same example, a child may have the skill of joining, but, for some reason, he does not succeed. In this case, if we want the child to take part, we do not have to teach him to do this (since he already knows how). Instead, we need to work on what hinders the use of the skill, which could be a lack of motivation, anxiety, or sensory sensitivity.

A good sign to distinguish between a lack of acquisition of a skill and a lack of use is the question "Can a child demonstrate a skill with many people and in many situations?" For example, if a child only talks to his mother at home and does not interact with peers at school, then this difficulty should be considered as a lack of mastery of the skill. I often hear from school teachers: “The child communicates well with me, so this must be a lack of use of the skill, right?” Not really. In my experience, children with autism communicate more often and better with adults, because adults usually make it easy for them - adults do all the “work” of communication for the child. In baseball terms, just because Tommy can hit the soft, low throws his dad practices at home doesn't mean he's good enough to hit the ball his peers throw at him on the playground. Sometimes an adult's interaction with a child on the autism spectrum is like those soft, low tosses. And although they do this with good intentions, it does not prepare the child for more difficult moments of communication with peers.

I often hear from school teachers: “The child communicates well with me, so this must be a lack of use of the skill, right?” Not really. In my experience, children with autism communicate more often and better with adults, because adults usually make it easy for them - adults do all the “work” of communication for the child. In baseball terms, just because Tommy can hit the soft, low throws his dad practices at home doesn't mean he's good enough to hit the ball his peers throw at him on the playground. Sometimes an adult's interaction with a child on the autism spectrum is like those soft, low tosses. And although they do this with good intentions, it does not prepare the child for more difficult moments of communication with peers.

Very often underdevelopment of social skills and unacceptable behavior are justified by a lack of use of skills. This is because we tend to think that if a child does not exhibit a behavior, it is due to rejection or lack of motivation. In other words, we think that a child who does not start socializing with peers can do it, but does not want to (lack of skill use). In many cases, this is an erroneous assumption. In my experience, most cases of lack of social skills in children with autism relate to the lack of these skills.

In many cases, this is an erroneous assumption. In my experience, most cases of lack of social skills in children with autism relate to the lack of these skills.

So if children with autism do not demonstrate some social skills, then most likely it is not because they do not want or refuse to be around other people, but because they simply do not have these skills. If we want young children to be successful in communication, then we must teach them exactly how to communicate. Therefore, it is important to focus on skill development.

The benefit of using the learning deficit/skill use gap model is that it helps us choose intervention strategies. Most corrective methods are better suited to either one or the other. The chosen method of intervention should correspond to the existing deficiency. You don't want to use an intervention program designed for lack of skill use if the child's main difficulty is mastering the skill.

In the example above, if Tommy hasn't mastered the batting skill (Lack of Mastery), no rewards in the world (not even pizza) will help Tommy hit the ball during the game. If we want him to hit shots well, we must additionally teach him the mechanics of hitting the ball. The same is true for social skills. If we want a child to communicate freely, then we must effectively teach him social skills. On the contrary, if Tommy has sufficient skills, but lacks the motivation to "go all out", then cheese and pepperoni pizza may be what will help him play successfully on the field.

If we want him to hit shots well, we must additionally teach him the mechanics of hitting the ball. The same is true for social skills. If we want a child to communicate freely, then we must effectively teach him social skills. On the contrary, if Tommy has sufficient skills, but lacks the motivation to "go all out", then cheese and pepperoni pizza may be what will help him play successfully on the field.

Once the detailed assessment of social skills has been completed and the team can attribute social difficulties to either a lack of skill acquisition or a lack of skill use, training can begin. There are many methods that can be applied to children with autism. Most importantly, the strategies that are applied to the child are suited to his personal needs, and that a logical explanation is given for the method used.

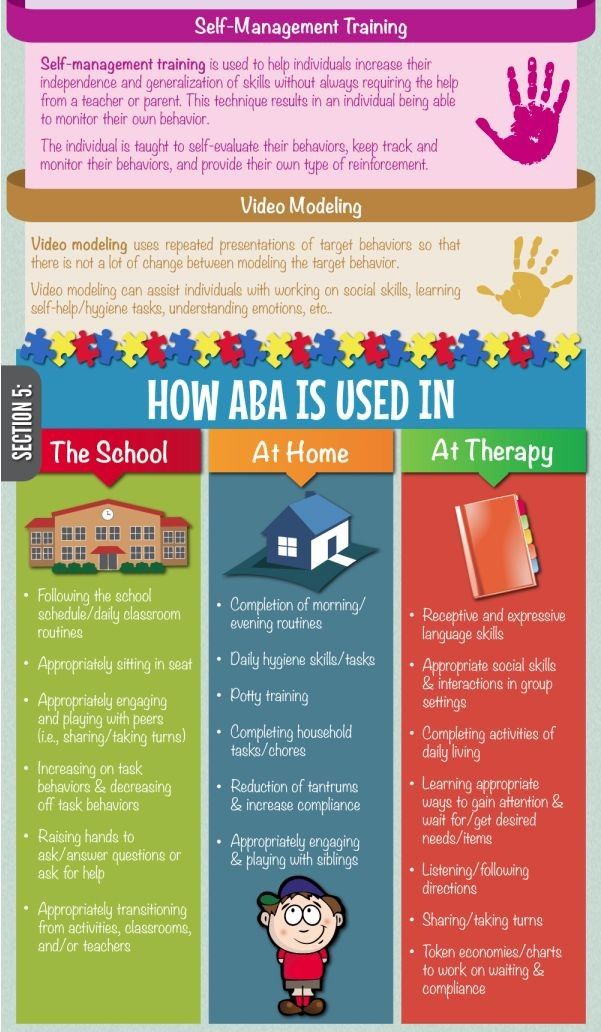

The following are examples of techniques that can be used to successfully teach communication skills to children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. All of the strategies listed below, except for the peer-based approach, are skill learning disadvantages. However, some methods (notably the video self-modeling method and the social story method) also work well when there is a lack of skill use. In addition, it is important to constantly reward the child for his efforts and participation in the educational program.

All of the strategies listed below, except for the peer-based approach, are skill learning disadvantages. However, some methods (notably the video self-modeling method and the social story method) also work well when there is a lack of skill use. In addition, it is important to constantly reward the child for his efforts and participation in the educational program.

Choice of remedial strategies

Change the child's environment or behavior

It is important to consider the principle of "changing the child's environment or behavior" when choosing a correction method. In the context of social skills training, the child's social or physical environment can be changed to provide opportunities for positive social interaction. Examples of this include: teaching peer helpers how to interact with the child during the school day, autism awareness training for classmates, including the child in different leisure groups such as sports teams or scouting squads.

On the other hand, you can change not the environment, but work on the behavior of the child himself. This includes learning that allows the child to be more successful in communication. A successful social skills development program must include both changes in the child's environment and work on his behavior. If you focus on only one thing, then your efforts may fail.

For example, one family I worked with did an excellent job of arranging peer play sessions for their child and ensuring that they attended various leisure activities in groups. At the same time, they were very disappointed that their son was unable to make friends, and he still had negative moments in communication with peers. The problem was that they put the cart before the horse. They provided the child with enough opportunities to communicate with others, but did not teach him the skills necessary to be successful in this communication.

Similarly, teaching a child a skill (behavior change) without changing the environment to be more friendly to the child with autism also leads the child to fail. This happens when a child with autism enthusiastically tries a newly acquired skill in a group of peers who do not accept it. It is important to both teach skills and change the environment. This will ensure that the new skill will be met with understanding by peers.

This happens when a child with autism enthusiastically tries a newly acquired skill in a group of peers who do not accept it. It is important to both teach skills and change the environment. This will ensure that the new skill will be met with understanding by peers.

Methods of teaching social skills

As previously stated, children and adolescents with autism need to be given extensive and detailed instruction in social skills. Traditional methods of teaching social skills (such as board games about friendship and proper classroom behavior) are confusing for many children with autism. For example, a school psychologist was frustrated with the little progress she had made with a student with autism. She claimed that the training program showed positive results in "other children in the group", but the child with autism did not seem to "understand" her. Of course he didn't understand! The reason was obvious. The school psychologist tried to teach the students the concept of "friendship". This is acceptable to other students, but for children with autism, these explanations were too abstract. So, instead of spending endless time telling a child about “friendship,” the training should have focused on specific skills that a child could use to make and keep friends. Experience tells me that the concept of "friendship" is much easier to understand when you already have a friend or a couple of friends!

This is acceptable to other students, but for children with autism, these explanations were too abstract. So, instead of spending endless time telling a child about “friendship,” the training should have focused on specific skills that a child could use to make and keep friends. Experience tells me that the concept of "friendship" is much easier to understand when you already have a friend or a couple of friends!

There are a number of issues to consider when choosing an intervention. For example, does the training program address the lack of skill acquisition identified in the Social Interaction Assessment? Does the program improve its use? Does the program provide an opportunity to master the skill? Are there studies supporting its use? If not, how do you plan to evaluate its effectiveness for your child? Is the program suitable for the child's developmental level? What follows is a list of social skills teaching methods that have proven effective in teaching children with autism.

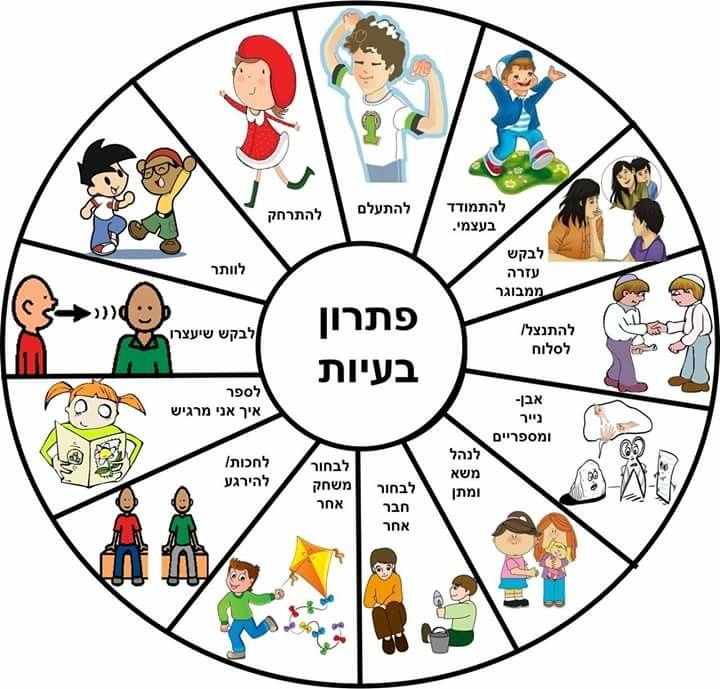

The following part of the article briefly describes the various intervention strategies that have been developed to teach social skills to young children with autism, including peer intervention, thought and feeling exercises, social stories, role playing, and video modeling.

Peer intervention

The use of peers as facilitators is one good example of effective intervention for young children with autism. Peer intervention is often used to establish positive social interaction among preschool peers (Strain & Odom, 1986; Odom, McConnell, & McEvoy 1992). Peer-involved learning allows us to structure the physical and social environment in a way that creates successful moments of social interaction.

With this approach, peers are trained to engage in communication and respond immediately and appropriately to the desire of a child with autism to communicate during the school day. Peer helpers must be classmates of the child with autism, must have age-appropriate social and play skills, must attend school regularly, and must have previously interacted with children with autism in a positive (or at least neutral) way. Peer helpers should also be taught about autism behaviors in a polite and age-appropriate way.

Peer helpers should also be taught about autism behaviors in a polite and age-appropriate way.

Using these helpers allows teachers and other adults to act as facilitators rather than active interlocutors and play partners. So, instead of becoming the third wheel in communication between two children, the teacher helps peers start a conversation or respond appropriately to a child with autism and walks away. Involving peers in communication also helps to generalize new skills and practice them in a natural environment.

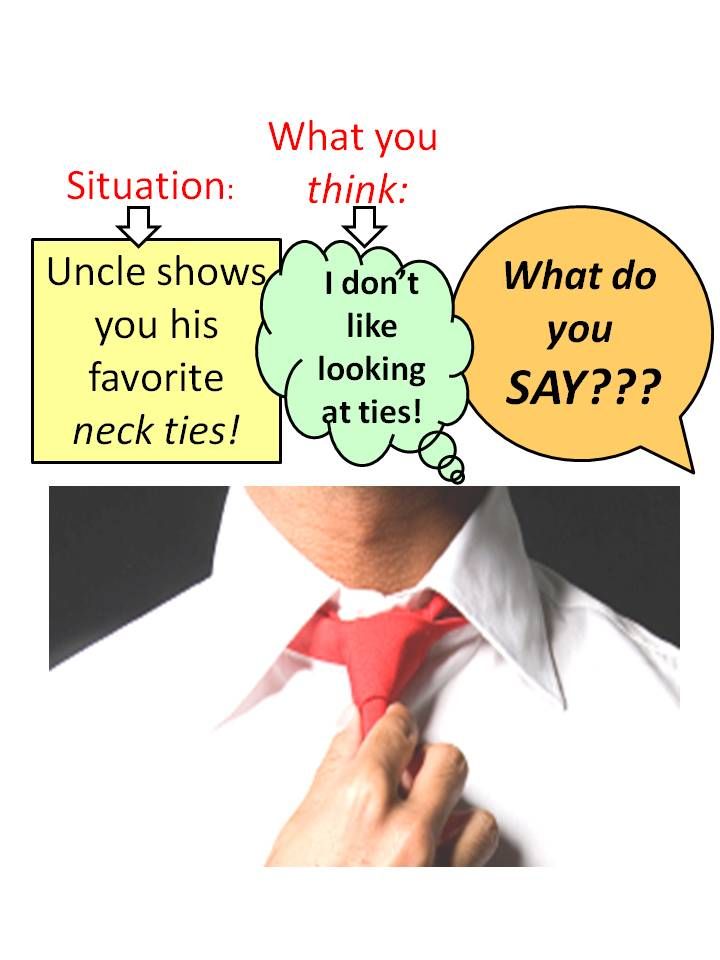

Lessons about thoughts and feelings

Recognizing and understanding thoughts and feelings, both one's own and those of others, is often the Achilles' heel of children with autism and is essential for successful communication. For example, we constantly change our behavior according to the non-verbal feedback we receive from other people. We can continue the story if the other person smiles, looks expectantly, or shows other signs of genuine interest. On the other hand, if a person keeps looking at his watch, sighs, looks the other way, we will probably shorten our story (I said “probably”!). Children with autism often have difficulty recognizing and understanding these non-verbal cues. This makes it harder for them to modify their behavior to meet the emotional and mental needs of others.

On the other hand, if a person keeps looking at his watch, sighs, looks the other way, we will probably shorten our story (I said “probably”!). Children with autism often have difficulty recognizing and understanding these non-verbal cues. This makes it harder for them to modify their behavior to meet the emotional and mental needs of others.

The simplest activity about thoughts and feelings involves showing the child pictures of various expressions of emotion. Pictures can range from the most basic, such as happy, sad, angry, or scared, to more complex emotions, such as embarrassed, bashful, nervous, or incredulous. Start by asking the child to point to an emotion (“show where happy is”), then ask the child to identify how the character feels (“how does he feel?”).

Many of the young children I work with learn to identify emotions quite easily. When they are already good at this, it's time to move on to more complex teaching methods, such as teaching the meaning of an emotion or "why?" this emotion appears. To do this, the child needs to draw conclusions based on the context and signs shown in the picture. So, based on the information in the picture, you can ask "Why is the child sad?". The pictures should depict characters participating in different social situations and showing different facial expressions or other non-verbal ways of expressing emotions. You can cut out pictures from magazines or download and print them from the Internet. You can also use illustrations from children's books, which are usually rich in emotional content and situational images.

To do this, the child needs to draw conclusions based on the context and signs shown in the picture. So, based on the information in the picture, you can ask "Why is the child sad?". The pictures should depict characters participating in different social situations and showing different facial expressions or other non-verbal ways of expressing emotions. You can cut out pictures from magazines or download and print them from the Internet. You can also use illustrations from children's books, which are usually rich in emotional content and situational images.