Sound spelling correspondences

Letter Sounds and Letter-Sound Correspondences

Contents:

- What are Letter-Sound Correspondences?

- Examples of Letter sound Correspondences

- Letter Sounds

- The Importance of Letter-sound Correspondences

- How to Teach Letter-sound Correspondences

- Phonemic Awareness vs Letter-sound Correspondence

- The Letter-Sound Correspondences in English

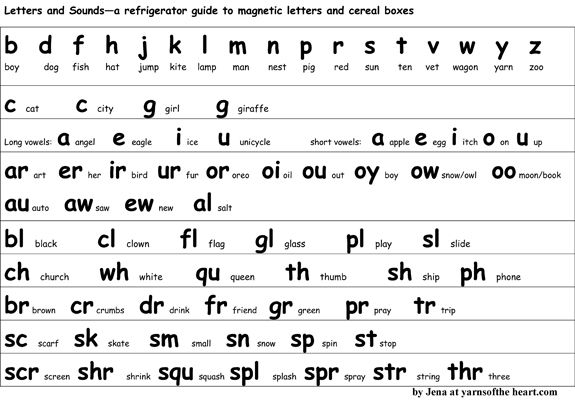

(Alphabetic/Phonemic Code Chart) - Common Questions:

- What Order Should Letters of the Alphabet and Phonemes Be Taught?

- Should you teach lowercase or uppercase letters first?

- What Age Should a Child Know Letter Sounds?

- How many letter sounds should a Kindergartener know?

- How many letters should a 3-year-old and a 4-year-old recognize?

- When should you teach a child letter sounds?

- Should you teach letter names or letter sounds first?

What are Letter-Sound Correspondences?

Letter-sound correspondences can be defined as the relationships between letters in the alphabet and the sounds in a spoken language. Each letter in the alphabet is associated with one or more of the speech sounds (phonemes) that make up vocalised words.

The term GPC, which stands for grapheme-phoneme correspondence is sometimes used as an alternative to letter-sound correspondence.

Letter-sound correspondences are sometimes collectively described as the alphabetic code.

Examples of Letter sound Correspondences

The simplest examples involve the associations between individual letters of the alphabet and spoken sounds.

For instance, the letter b represents a particular sound in words such as big or cab that is distinct from the sounds represented by the other letters in these words.

Letter sounds are indicated by forward slashes in some phonics programmes. For example, the sound represented by the letter b in the above words would be written as /b/.

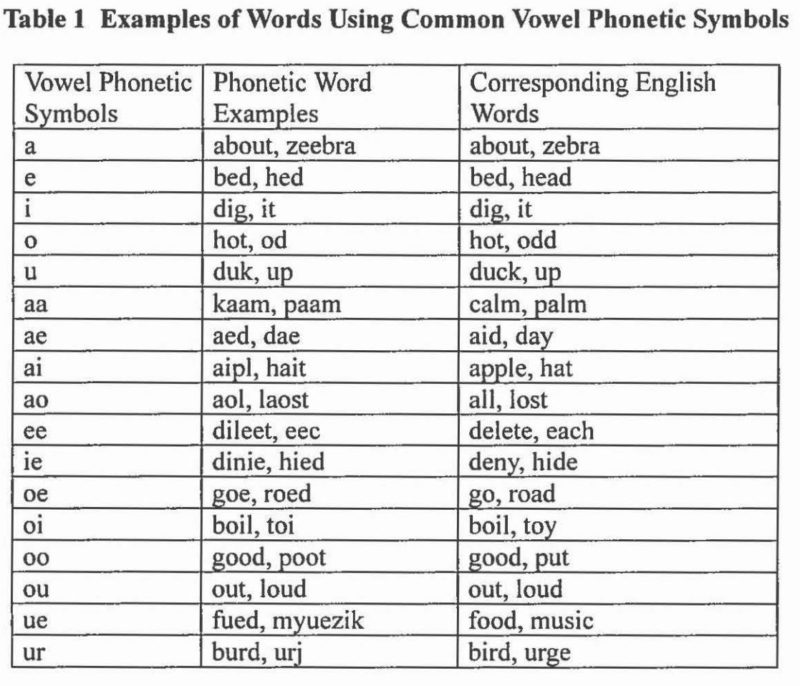

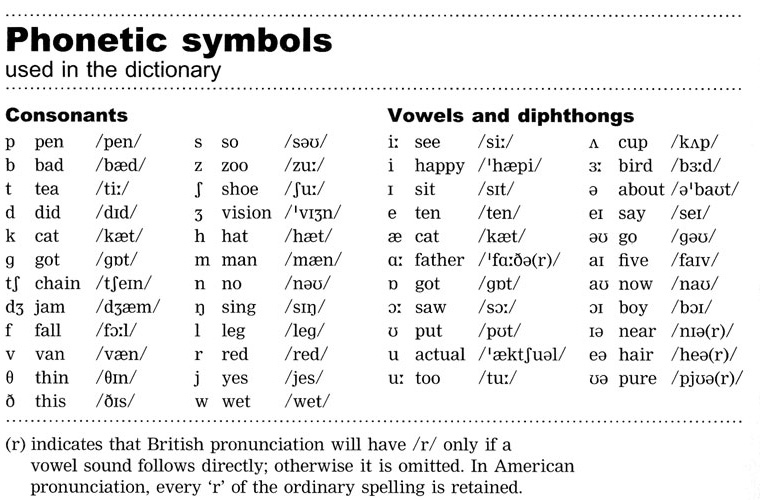

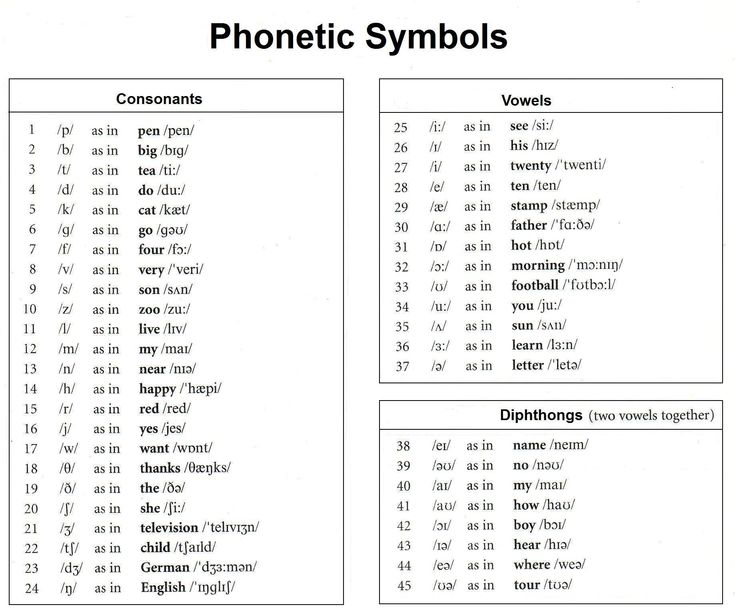

The international phonetic alphabet has specific symbols for spoken sounds which are sometimes the same as the printed letters and sometimes different.

For example, the sound associated with the letter b in the above examples is written as b, but the sound represented by the letter a in the words ant and cap is written as æ.

The ‘long a’ sound represented by the letter a in words such as apron and baby is represented by /ai/ in many phonics programmes and by eɪ in the international phonetic alphabet.

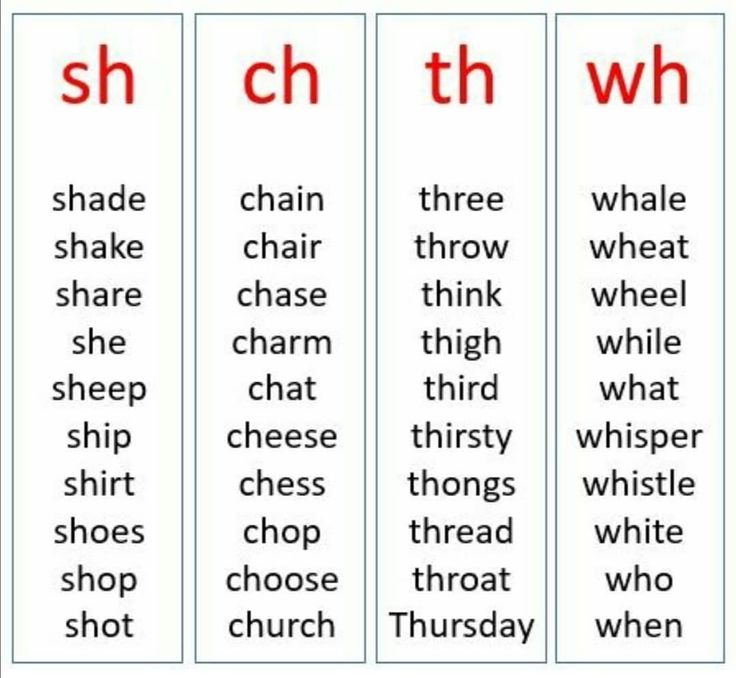

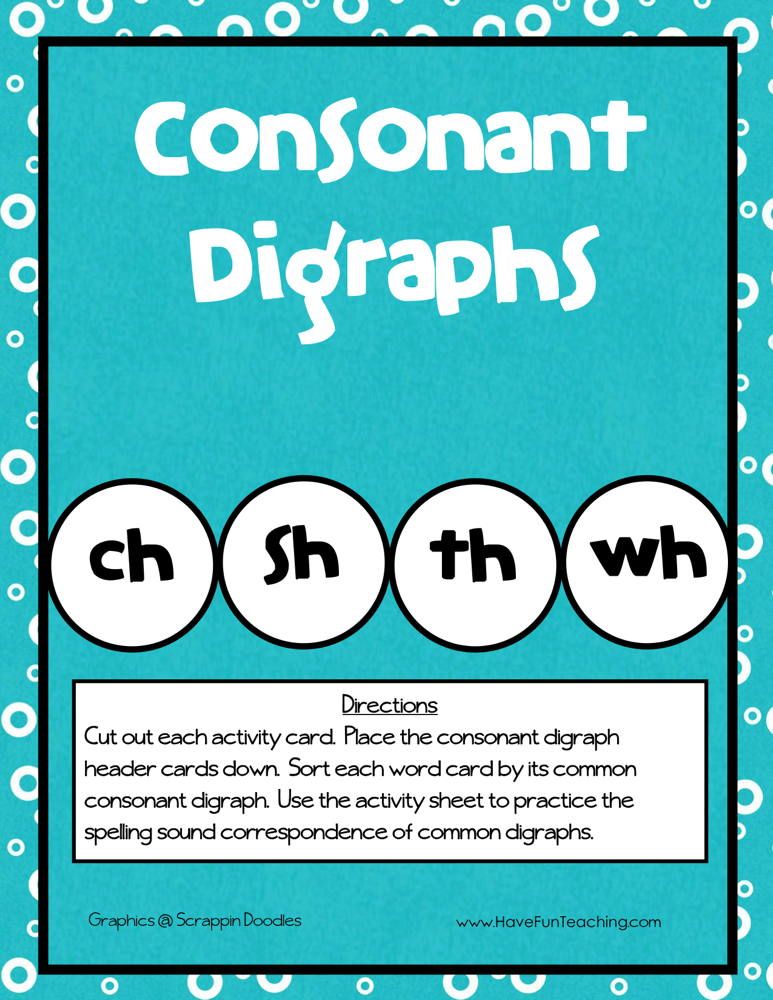

Some letter-sound correspondences are more complicated because groups of letters are used to represent individual sounds. These are called digraphs, trigraphs or quadgraphs depending on the number of letters used to represent the sound.

See our section below on the Letter-Sound Correspondences in English for a comprehensive list of examples.

Back to contents…

Letter Sounds

It’s common for educators to talk about teaching ‘letter sounds’, but letters don’t actually make sounds – they represent sounds.

However, since most 4 and 5-year-olds don’t understand the meaning of the word ‘correspondence’, many teachers find it easier to tell their children that letters

have sounds. Some phonics purists are scornful of anyone who teaches this idea, but we haven’t seen any evidence that it’s harmful.

Some phonics purists are scornful of anyone who teaches this idea, but we haven’t seen any evidence that it’s harmful.

Nevertheless, it is possible to give children a more accurate and child-friendly explanation of the connection between letters and sounds. Just tell them that letters ‘stand for’ sounds.

For example, hold up a card with the letter ‘a’ on it and say, “This letter stands for the /a/ sound we hear at the start of ‘apple’ or ‘ant’”. And “This letter stands for the /b/ sound we hear at the start of ‘bug’ or ‘bat’”.

The Importance of Letter-sound Correspondences

Understanding letter-sound correspondences is essential for reading and spelling words in all writing systems that are based on an alphabetic code.

- The ability to recognise letters and link them to spoken sounds allows children to decode written words. This strategy can help children read words even if they’ve never encountered them in print before.

- The ability to segment spoken words into individual sounds and then recall the letters used to represent those sounds is one of the most important skills needed for accurate spelling.

- The ability to recognise letters and link them to spoken sounds allows children to decode written words. This strategy can help children read words even if they’ve never encountered them in print before.

Back to contents…

How to Teach Letter Letter-sound Correspondences

Research suggests that explicit phonics instruction is the most effective way to teach letter-sound correspondences.

Some children can ‘pick up’ letter-sound relationships without formal instruction if they spend a lot of time reading books with a supportive adult. However, all children are likely to learn more quickly with some direct instruction.

We explain how you can teach your child the letter sounds in our phonics article.

One of the most effective activities for helping children grasp letter-sound correspondences is segmenting spoken words and then writing them or constructing them with letters. See spelling with magnetic letters or alphabet cards in our article on spelling.

Electronic games can also be helpful. Use the following link to access a variety of free online games for letter sounds.

See also ‘What Order Should Letters of the Alphabet and Phonemes Be Taught?’ and ‘Key Principles for Teaching Letter-Sound Correspondences‘ later in this article.

Back to contents…

Phonemic Awareness vs Letter-sound Correspondence

- Phonemic awareness is an auditory skill that involves identifying sounds in spoken words. It can be practised verbally without any reference to printed words.

- Learning letter-sound correspondences involves linking the sounds in spoken words to letters in written words.

Some educators believe that it’s important for children to develop phonemic awareness skills before they are taught about letters and the sounds they are associated with.

However, research suggests that teaching letter-sound correspondences improves phonemic awareness.

In fact, there is no real benefit in developing phonemic awareness in the absence of letters. For children to become proficient at reading and spelling, they need to see the connection between phonemes and letters in our alphabetic writing system.

For children to become proficient at reading and spelling, they need to see the connection between phonemes and letters in our alphabetic writing system.

Back to contents…

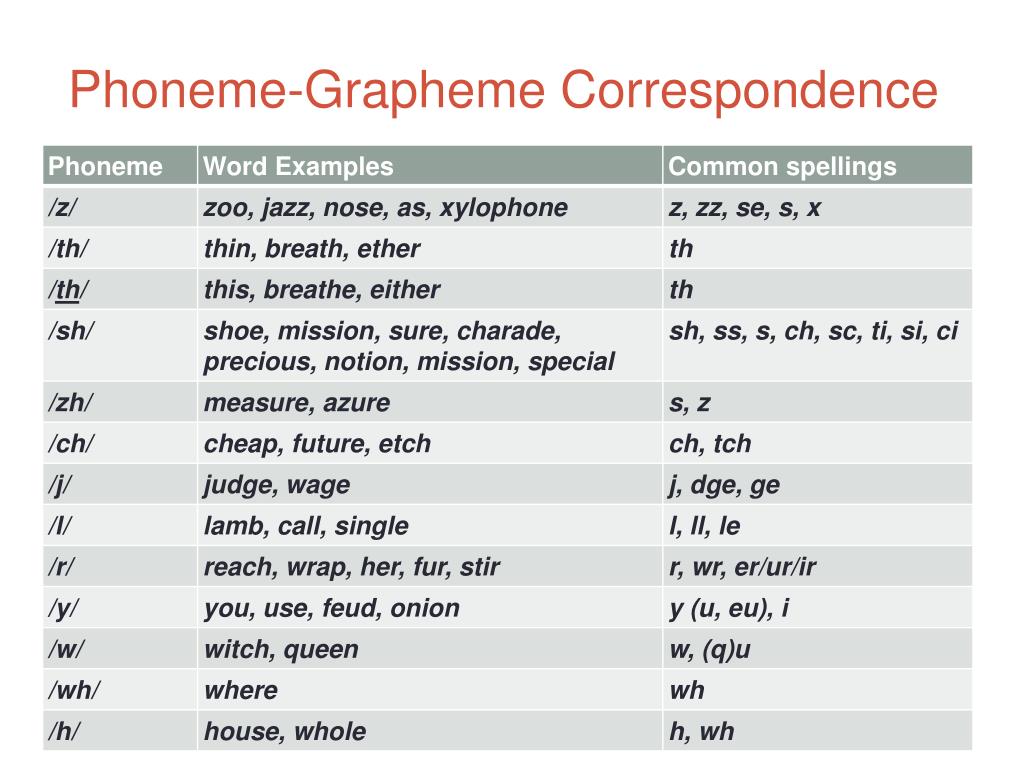

The Letter-Sound Correspondences in English

In some languages, the relationships between letters and sounds are very simple and consistent. For example, in Finnish, there is a one-to-one letter-sound correspondence in most words.

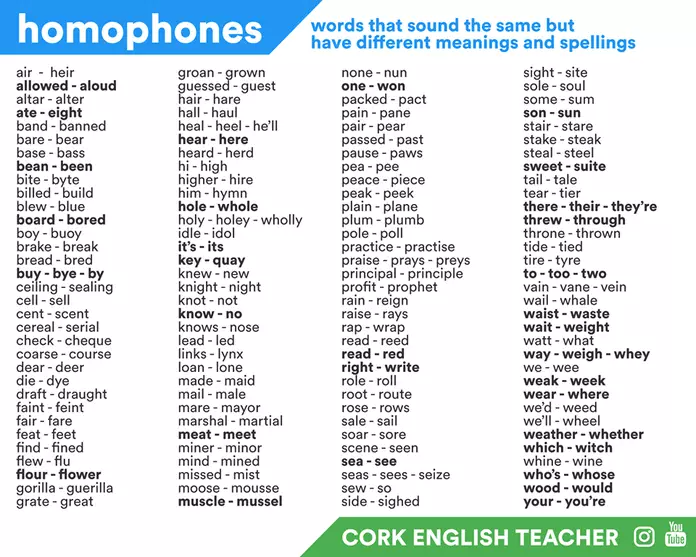

However, the letter-sound correspondences in English aren’t straightforward. Some sounds are represented by combinations of 2 or 3 letters (see digraphs and trigraphs) and individual letters don’t always represent the same sound.

For example, the sounds represented by vowel letters can vary in different words…

Compare the sound represented by the letter a in ‘angel’ to the sound in ‘ant’ or ‘apple’.

Some consonants can also represent different sounds. For example, the letter s in ‘frogs’ represents a different sound from the letter s in ‘snake’. And the letter y in gym represents a vowel sound, which is quite different from the sound it represents in yellow.

And the letter y in gym represents a vowel sound, which is quite different from the sound it represents in yellow.

In fact, it isn’t strictly correct to say that some letters are vowels, and some letters are consonants because combinations of various letters can represent vowels (such as ‘igh’), and some ‘vowel’ letters can also represent consonants in a few words.

We’ve made a reasonably comprehensive list of the letter-sound correspondences in English in the table below which could also be described as an Alphabetic/Phonemic Code Chart. You can download this chart as a free pdf.

The letters between forward slashes / / are used in the UK Government’s ‘Letters and Sounds’ phonics programme. The green symbols in round brackets are used in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Click on the image to download the chart as a pdf.For an even more comprehensive list see the Spelfabet site.

To listen to the phonemes represented with the International Phonetic Alphabet Chart, you can download a free phonemic pronunciation chart app from the British Council.

You can listen to the phonemes represented by ordinary letters on Oxford Owls Phonics Audio Guide.

Back to contents…

Common Questions:

What Order Should Letters of the Alphabet and Phonemes Be Taught?

No specific order for teaching letters and sounds in phonics has been proven to be better than all the alternatives. And it’s unlikely that anyone will ever find the best order because there are so many different sequences that could be used it would be impossible to investigate them all.

For instance, if we chose to teach just the first 4 letters from the alphabet, these could be arranged or introduced in 24 different ways:

{a,b,c,d} {a,b,d,c} {a,c,b,d} {a,c,d,b} {a,d,b,c} {a,d,c,b} {b,a,c,d} {b,a,d,c} {b,c,a,d} {b,c,d,a} {b,d,a,c} {b,d,c,a} {c,a,b,d} {c,a,d,b} {c,b,a,d} {c,b,d,a} {c,d,a,b} {c,d,b,a} {d,a,b,c} {d,a,c,b} {d,b,a,c} {d,b,c,a} {d,c,a,b} {d,c,b,a}

With 8 letters, the number of permutations jumps to 40,320, and with 26 letters there are a staggering 4. 0 x 1026 possible arrangements!

0 x 1026 possible arrangements!

Nevertheless, despite the huge number of alternative sequences, we can still glean some useful guidelines for teaching letters and phonemes from research. And insights can also be obtained by looking at the order phonemes are taught in successful phonics programmes…

The ‘Carnine order’ shown below is probably one of the most well-thought-out approaches to teaching letters and sounds. It’s based on the research and teaching experience of a group of American educators, and it was popularised in their book, ‘Direct Instruction Reading’*. It’s also recommended by the University of Oregon.

*Carnine, Silbert, Kame’enui and Tarver (2009), Direct Instruction Reading, Pearson

Carnine Order:

| a m t s i f d r o g l h u c b n k v e w j p y T L M F D I N A R H G B x q z J E Q |

At first glance, the Carnine order looks quite random, but the researchers had specific reasons for using this sequence of letters:

- Letters that occur frequently in words are taught earlier in the sequence because these can be used to make a greater variety of words for early blending practice.

- They avoided teaching letters with similar appearances together. For example, the letters d, b and p all have the same basic shape (but different orientations). The fear is that children could be confused if they were to meet all these letters in the same session.

- They also avoided teaching letters together that are pronounced in a similar way.

- Some letters that represent continuous sounds are taught early in the sequence because children can find it easier to blend words containing these sounds. Examples of continuous sounds include those represented by the vowel letters and the consonants ‘m’, ‘s’ and ‘f’.

- Lower case letters are mostly taught before capital letters because they occur more frequently in words. However, some capital letters are taught alongside the lowercase versions if they look similar. For example, the letters s, and u look very similar in lower case an upper case (s, S and u, U) so these are taught together. Capital letters that look different from the lowercase versions (such as A and B) are taught later.

- Letters that occur frequently in words are taught earlier in the sequence because these can be used to make a greater variety of words for early blending practice.

The direct instruction reading strategy followed by Carnine and the other researchers has been shown to be very effective with a diverse range of student populations and it was the most successful programme in the extensive Project Follow Through experiment.

Although they don’t use the exact same sequence, several other successful phonics programmes follow similar principles to those used in the Carnine order.

For example, Jolly Phonics also teach lower case letters first and the first letters introduced include: s, a, t, i, p and n. All these letters occur quite frequently in English words, and some represent continuous sounds, so they can be used to make a variety of suitable words for early blending and segmenting practice. Most of the letters introduced early by Jolly Phonics also appear early in the Carnine Order.

The letters in ‘satpin’ are also taught first in Letters and Sounds, the UK Government’s phonics programme. We suspect the Letters and Sounds team borrowed the sequence from Jolly Phonics. The programme suggests using the following words made from the letters in ‘satpin’ for early blending practice:

We suspect the Letters and Sounds team borrowed the sequence from Jolly Phonics. The programme suggests using the following words made from the letters in ‘satpin’ for early blending practice:

at, a, sat, pat, tap, sap, it, sit, sat, pit, tip, pip, sip, an, in, nip, pan, pin, tin, tan, and nap.

Some of the other letters that are introduced early in Letters and Sounds, such m and d, also appear early in the Carnine Order.

The Sounds-Write programme, another successful course that’s popular in the UK, begins with the letters a, i, m, s, t, n, o and p. Again, most of these letters appear early in the Carnine order.

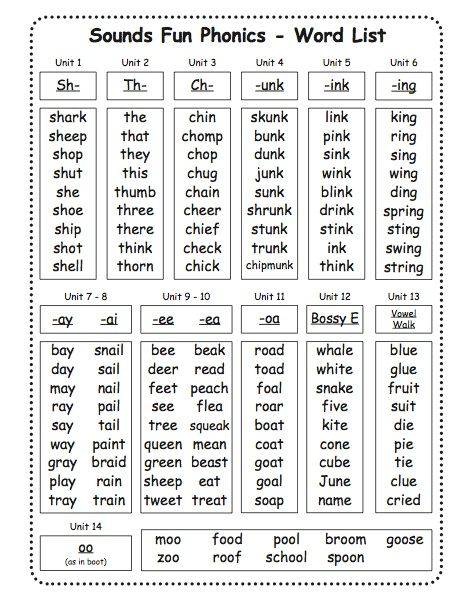

We’ve included the full sequences of letters and sounds for these phonics programmes below. Notice that some ‘digraph sounds’ are taught before the less common individual letter-sound correspondences in some programmes.

Jolly Phonics

s, a, t, i, p, n, ck, e, h, r, m, d, g, o, u, l, f, b, ai, j, oa, ie, ee, or, z, w, ng, v, oo, oo, y, x, ch, sh, th, th, qu, ou, oi, ue, er, ar.

Some alternative spellings for vowel sounds are taught after these letter combinations.

Letters and Sounds

s, a, t, p, i, n, m, d, g, o, c, k, ck, e, u, r, h, b, f, ff, l, ll, ss, j, v, w, x, y, z, zz, qu, ch, sh, th, ng, ai, ee, igh, oa, oo, ar, or, ur, ow, oi, ear, air, ure, er.

Some alternative spellings for vowel sounds are taught after these letter combinations – see our digraphs article for details.

Sounds-Write

a, I, m, s, t, n, o, p, b, c, g, h, d, e, f, v, k, l, r, u, j, w, z, x, y, ff, ll, ss, zz, sh, ch, th, th, ck, wh, ng, qu.

Alternative spellings for vowel sounds are taught after these letter combinations.

As you can see from the examples we’ve shown above, different programmes can use slightly different letter and sound sequences and still get good results. So, the exact order of instruction probably doesn’t make much difference as long as it’s based on sound principles.

Other Considerations

While the principles used in the examples above are certainly well-considered and logical, they aren’t set in stone. Children enter preschool, Kindergarten and reception classes with different abilities and experiences, so it’s also worth considering alternative approaches.

Children enter preschool, Kindergarten and reception classes with different abilities and experiences, so it’s also worth considering alternative approaches.

In the academic paper, Enhancing Alphabetic Knowledge Instruction*, Professor Cindy Jones and her colleagues advocate flexible distributed instructional cycles based on what they describe as ‘Alphabetic Knowledge Learning Advantages’.

*Cindy D. Jones, Sarah K. Clark and D. Ray Reutzel (2012), Enhancing Alphabet Knowledge instruction. Early Childhood Education Journal.

The idea is to spend a cycle of around 5 weeks focussing on one learning advantage before switching to another 5-week cycle that focuses on a different learning advantage, then another, and so on.

The guidelines for the approach encourage flexibility. So, a teacher can assess student progress in a cycle and identify which letters they are finding most difficult to learn. The teacher can then select the most appropriate instructional cycle to use next that will best deal with the students’ needs.

The approach can be used in whole-class settings or in small groups.

The ‘learning advantages’ described in the paper have been identified by research and include:

Own name advantage: Many children find it easier to learn how to name and print the initial letter of their own name compared to other letters in the alphabet. This is probably because kids are more motivated to learn letters that have a strong connection with their own identity.

Also, mentioning someone’s name is one of the best ways to get their attention, and, according to the neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene, attention is one of the four pillars of learning*.

* Dehaene, S. (2020) How We Learn: The New Science of Education and the Brain, Penguin Books.

The name advantage could be extended further by looking at the letters in words for other things that children might have a significant emotional connection to. Anything that’s likely to get their attention and make them more motivated to learn could be suitable. For example, words like Mum/Mom, Dad, names of siblings, pets, favourite sports teams or where they live.

Alphabetic order advantage: Some educators argue that the normal alphabetic order isn’t ideal for learning letter sounds. However, it might have some benefit for children who’ve already learned the names and shapes of the letters from alphabet songs or books.

For example, some letter names (such as ‘bee’, ‘dee’, ‘ef’ and ‘em’) begin or end with sounds represented by the letters and studies have shown that children can learn these letter-sound relationships more easily if they already know the letter names*.

*Treiman, R., Weatherston, S., & Berch, D. (1994). The role of letter names in children’s learning of phoneme-grapheme relations.

Lots of children learn the alphabet song and alphabet books are very popular – we found over 80,000 results in a search for alphabet books on the UK Amazon site alone. Consequently, for kids who can already recognise the letters of the alphabet, some of the principles used in the Carnine Order might not be so important.

One disadvantage of teaching letter-sound relationships in alphabetic order is that kids tend to remember letters at the beginning and end of the alphabet, but struggle to recall the letters in the middle. This is probably due to primacy and recency effects.

Letter frequency advantage: Children find it easier to learn letters that appear more often in print. The researchers suggest teaching the less common letters first in this cycle so there is a greater focus on them before moving on to the more common letters. This approach contrasts with the Carnine order where the most frequently occurring letters are taught first.

- The consonant letters from most to least frequent are r, t, n, s, l, c, d, p, m, b, f, v, g, h, k, w, x, z, j, q and y.

- The vowel letters from most to least frequent are i, a, e, o and u.

Distinctive visual features letter writing advantage: Children find it relatively easy to distinguish between letters that have distinct visual features. For example, they can easily see the difference between the letters a and z or b and x.

However, they can find it difficult to distinguish between letters that have similar visual features. For example, the uppercase letters C and G are very similar, as are E and F, P and R, and O and Q. The lowercase letters b, d, p and q are also similar in shape, and so are m, n, and u.

In this cycle, letters with similar features might be introduced together and the teacher would highlight features that can help students recognise the differences between the similar letters.

For instance, they would draw the students’ attention to the tail in the letter Q and compare it to O which is similar but doesn’t have a tail. Or they might highlight the extra horizontal line at the bottom of E to help students see the difference between this and the letter F.

The idea of teaching visually similar letters together differs from the Carnine approach where they are taught separately.

The creators of the Enhancing Alphabet Knowledge (EAK) approach recommend a simple 3-stage process for teaching letters in each cycle:

- First children are explicitly taught to identify the name and sound of the uppercase and lowercase form of the letter introduced that day.

- Next, the children are provided with books and other written texts and they are asked to find examples of the day’s letter in lowercase and uppercase.

- Finally, they are taught how to write the letter.

Research has shown that EAK instruction produces better results than the traditional approach used in some early childhood classrooms where one letter is taught every week.

Unfortunately, we’re not aware of any studies that make direct comparisons between the effectiveness of the EAK approach and the Carnine order.

Our thoughts and conclusions…

It seems that children can be taught letters and phonemes successfully in a variety of different sequences. Good arguments can be made for using a number of different orders of instruction including some we haven’t explored here, such as following a sequence of letters that’s good for teaching handwriting.

We’re inclined to favour the reasoning behind the Carnine order and the sequences in the popular phonics programmes. We especially like their initial focus on learning letters that can be used to make a variety of suitable words for early blending and segmenting practice.

Also, some of these sequences have been used for decades and they’ve been proven to work well in thousands of classrooms around the world.

However, we also think there is some merit to the flexible use of learning advantages for responding to individual student needs as described in the EAK approach.

We also think it’s important to think carefully about the order digraphs and trigraphs are introduced, but the Carnine and EAK approaches don’t really address this. You might find it helpful to read the section ‘What Order Should I Teach Digraphs?’ in our article about teaching digraphs.

Key Principles for Teaching Letter-Sound Correspondences

Overall, we believe there are some key principles for teaching letters and phonemes that are probably more important than the order the phonemes are introduced:

- Only Introduce a few letters and phonemes in each session.

- Focus on the sounds represented by letters rather than letter names.

- Review previously taught phonemes continuously.

- Practise blending and segmenting words containing the letters that have been taught.

- Practise handwriting individual letters and simple words.

These key principles are based on research into the alternative sequences described above and established learning theories from cognitive science.

Only Introduce a few letters and phonemes in each session…

Most academics and experienced teachers would agree that teaching the whole alphabet along with its associated phonemes in one go would be counterproductive.

This would almost certainly result in cognitive overload and leave the children confused and demoralised.

How many letters should I teach a week?

Established and successful programmes such as Jolly Phonics, Sounds-Write and the UK Government’s Letters and Sounds programme only teach a handful of phonemes each week.

Jolly Phonics suggest teaching no more than one letter-sound correspondence each teaching day or around 4-5 per week and Sounds-Write and Letters and Sounds both introduce letters at about the same rate.

The creators of the Enhancing Alphabet Knowledge (EAK) approach also recommend introducing letters at a rate of one per teaching day.

Focus on the Sounds Represented by Letters Rather than Letter Names.

Learning letter names early doesn’t actually help children learn to read and early exposure to letter names can have a detrimental effect on spelling. We discuss these points in more detail in our article ‘Should I Teach my Child Letter Names’.

Review previously taught phonemes continuously

There’s an old saying that ‘repetition is the mother of learning’ and there is a lot of truth in this. Reviewing material that has been encountered before is essential for the consolidation of long-term memories. So, when you introduce a new letter, spend a few minutes reviewing some previously introduced letters at the end of the session.

It’s been shown that spacing out reviews over a period of several days and weeks (distributed practice) is more effective than cramming a lot of content into a single session.

To become proficient readers, children need automatic and instantaneous recall of letter-sound correspondences. And as cognitive scientists such as Dan Willingham have pointed out, ‘for new knowledge to become long-lasting, sustained practice, beyond the point of mastery, is necessary.

Practise Blending and Segmenting Words containing the letters that have been taught.

Letters and sounds don’t have to be reviewed in isolation; they can be presented within simple words and reviewed as part of blending practice.

This is a more efficient use of time as the students will be improving their blending skills at the same time as consolidating their knowledge of letter-sound correspondences.

Blending practice also teaches kids why learning letters and sounds are useful and important. Understanding the relevance of what they are doing can make them keener to learn according to the Expectancy value theory of motivation.

And as students become more proficient at blending, they can progress to reading sentences and passages and this will allow them to review their letter-sound correspondences in a more natural way.

However, if a child is constantly tripping over a particular correspondence, it would be helpful for them to spend some time reviewing this more frequently.

Segmenting words is like blending in reverse and it can really help to embed a child’s knowledge of letter-sound correspondences. However, it’s only really effective for this purpose if the segmented words are then spelled with magnetic letters, alphabet cards or in writing.

Segmenting done as a purely oral exercise, or by moving tokens counters in Elkonin boxes won’t help children learn letter-sound correspondences.

Practise Handwriting Individual Letters and Simple Words.

As we mentioned in our article about handwriting, writing by hand helps to establish brain connections that are important for reading and spelling.

In order to write accurately, children need to focus on the key characteristics of each letter, and this allows them to build stronger representations of the fine details in their brains.

Back to contents…

Should you teach lowercase or uppercase letters first?

There is no hard and fast rule on this. Children need to learn both lowercase and uppercase letters eventually, so it probably doesn’t make a big difference whether you teach them together or separately.

However, we think there’s some logic behind the Carnine approach where lower case letters are taught before capital letters because they occur more frequently in words.

What Age Should a Child Know Letter Sounds?

Children should recognise some letters and know the sounds they represent by the time they are around 5 years old because this is the age when most children begin reading instruction in school.

How many letter sounds should a kindergartener know?

This might vary with the curriculum policies of different schools and different districts, but it’s not unusual for children to be able to match all 26 letters to sounds by the time they finish kindergarten. In the UK, children are expected to know all the letters and their associated sounds by the time they are halfway through reception.

How many letters should a 3-year-old and 4-year-old recognize?

There are no fixed expectations for knowledge of letters or letter sounds by age before children start formal schooling and there is a great deal of variation in preschool children.

How many letters a young child knows depends on the amount of input they have had at home or in preschool and also on their individual development.

When Should You Teach a Child Letter Sounds?

Children can be informally introduced to letter sounds as soon as they recognise that text represents spoken language.

However, you don’t have to teach your child letter sounds before they start school unless you choose to. Some children don’t know any letter sounds before they start school whereas others know them all.

A relatively small number of children can recognise all the letters and the sounds they represent by the time they are around two years old. However, this is only likely if they have had a lot of exposure to letters from a very young age.

See our article ‘Should I Teach My Baby or Toddler to Read?’ for more information on the pros and cons of teaching very young children literacy skills.

Should You Teach Letter Names or Sounds First?

Opinions vary on this issue, but our own view is that a knowledge of letter sounds is much more important for learning to read and spell accurately. See our article, ‘Should I Teach my Child Letter Names’, for a more detailed discussion of this question.

Back to contents…

Teaching Letter-Sound Correspondences and Syllable Types for Word Identification

Using a word box can help students determine what letters should represent what sounds they can hear in a given word.

Project Manager, University of Tennessee Knoxville

Professor and Director, Tennessee Reading Research Center

Assistant Professor, Augustana College

Findings of research studies consistently have confirmed that alphabetics and phonics instruction contribute to the reading achievement of children (e.g., Murphy & Farquharson, 2016). These foundational skills are not the ultimate goal of reading instruction, nor are they sufficient to enable a student to read with understanding (Brady, 2011). However, in alphabetic language systems such as English, an understanding of how language sounds are represented in letters is a necessary part of making sense of written words (Ehri, 2014). Some children may learn certain letter-sound correspondences or basic words through extensive exposure to books and printed words in their environment (Pelatti, Piasta, Justice, & O’Connell, 2014). Unfortunately, the letter-sound correspondences in English are not as obvious or consistent as in other alphabetic languages like Italian or Finnish (Seymour, Aro, & Erskine, 2003), so it can be very difficult to learn all the different ways that our language might be represented through simple exposure. It often is more efficient to teach letter-sound correspondences directly (Keesey, Konrad, & Joseph, 2015).

This instruction also occurs in a sequence that moves from easier to progressively more complex skills. For example, initial instruction in letter-sound correspondences might be ordered as follows:

- Consonants representing the most common sounds and vowels representing short sounds

- Consonant digraphs

- Two-letter consonant blends

- Three-letter consonant blends and digraph blends

- Welded sounds (e.

g., all, ing, ink)

- Single vowels or vowel-consonant-e patterns representing long sounds

- R-controlled vowels

- Vowel digraphs

- Consonant-le patterns

- -sion/-tion endings

It is important to keep in mind that the sequence above is one possible way of ordering lessons from easier to more difficult correspondences. Different curricula may have slightly different sequences to align with supporting materials such as decodable texts.

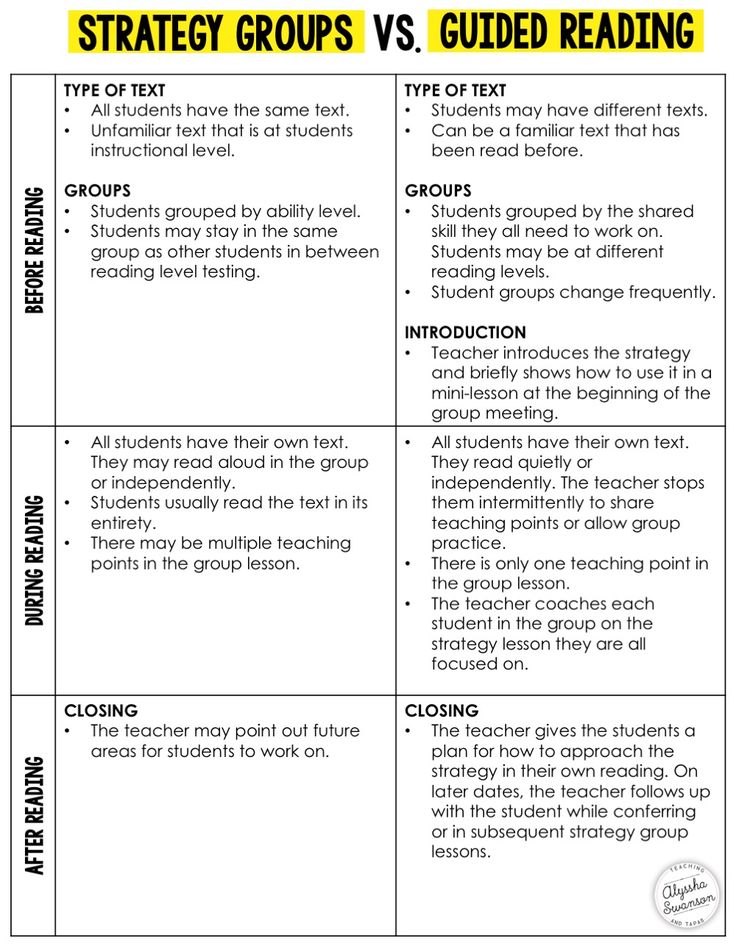

Example Elementary-Level Lesson for Effective Phonics Instruction

The objective of the following example phonics lesson outline is to identify letter-sound correspondences to decode closed-syllable, consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words. Given this focus, it is intended for elementary students. However, the type of instruction described can be adapted for secondary students (see Figure 2). The lesson outline provides a scripted think aloud for the modeling phase and incorporates a tool referred to as a word box. Word boxes are used to help students segment or break apart the individual sounds (phonemes) in a word and represent those sounds with letters (graphemes) that can be blended together again to read the word. A word box is created by dividing a rectangle with vertical lines drawn inside the rectangle. At first, a picture is placed above the divided rectangle, and the number of boxes provided below the picture equals the number of sounds in the word that the picture represents. Later, the number of boxes may remain constant so that students have to determine the number of sounds for themselves. As students begin to read more complex words, the boxes may be used to represent syllables rather than individual sounds. Blank template word boxes can be found in the Supplemental Material for Teachers section.

Introduction

To begin, tell students the objective of the lesson is to identify the sounds in a word and how to represent those sounds with letters so that they can read the word. After stating the objective, activate students’ background knowledge with a warm-up activity or review of the phonics skills learned in previous lessons. Before beginning the new instruction, remind students of the importance of learning letter-sound correspondences and how phonics skills can improve reading ability by giving readers a way to figure out new words they see in their books. Explain that skilled readers can identify the individual sounds in a word and can connect those sounds with letters. To learn how to do that, tell students they will be using cards with letters printed on them, or letter cards.

Modeling

Model the steps of using letter cards with word boxes either on paper, with a document camera, or using an interactive whiteboard. Use decodable words with corresponding pictures. Be sure that the words chosen for the lesson are appropriate for students’ age and the syllable types they have learned in a systematic sequence. The words in this example lesson are appropriate for students who have learned the common consonants and short vowels. Students will be applying those letter-sound correspondences to decode closed syllable, CVC words. The following is an example of introducing the word box and thinking aloud to model the use of it (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Example Word Box

| m | a | p |

Today we are using a word box and letter cards to practice decoding words with the letter-sound correspondences you have been learning. I am going to model how to use the word box and then we will practice together. To begin, watch me as I model how to use the word box.

This is a word box (place word box and letter cards in front of students). At the top of the word box is a picture of a map. At the bottom of the word box are three boxes. These three boxes tell us how many sounds there are in the word “map. ” The first sound I hear in “map” is /m/. I know that the letter “m” represents the sound /m/ (arrange the letter cards in front of the students so that they can see you find the “m” letter card and place it in the first box on the word box).

I found the “m” letter card. I am going to place the “m” letter card in the beginning box on the word box. The letter “m” represents the sound /m/ in “map.” The middle sound I hear in “map” is /ă /. That /ă/ is the short “a” vowel sound. I am going to choose the “a” letter card and place it in the second box to represent the /ă/ sound (arrange the letter cards in front of the students so that they can see you find the “a” letter card and place it in the middle box on the word box).

The ending sound in “map” is /p/. The consonant “p” represents the sound /p/. I am going to find the “p” letter card and place it in the ending box on the word box (arrange the letter cards in front of the students so that they can see you find the “p” letter card and place it in the end box on the word box).

I found all the letters for the word “map.” Now I am going to practice saying all the sounds in “map.” As I say each sound, I am going to touch each letter that represents that sound: 1) /m/, 2) /ă /, and 3) /p/. Blend all the sounds together, “map” (repeat the modeling 3-5 times or until the students understand the procedures).

Guided Practice

Explain to students that they will use the word boxes to spell and read words when their small groups meet with the teacher. Provide each small group with a set of pictures for words containing only the syllable types and letter-sound correspondences that the students have learned. In this lesson, the practice would continue with CVC words. Display a picture in the top box and follow the procedures from the modeling phase. However, during guided practice, include the students in carrying out the steps. Ask students to state the word that the image or picture represents. Then, ask students to say and count each sound in the word. Ask how many boxes are needed to represent the sounds in the word. Guide students in selecting letter cards to represent each sound and placing the cards in the boxes. After all the letter cards are placed, have students repeat in unison each sound. Finally, have students blend all the sounds together to form the target word. Ask students to confirm that the word they read matches the picture. Complete additional guided practice words if all students did not respond accurately. This phase should be repeated 3-5 times, or until students demonstrate understanding.

Independent Practice

While still working with a small group, transition from whole-group responses to individual student responses. If in a one-on-one setting, transition from teacher-and-students responding to individual student responses. Display a new picture in the top box. Ask a student to select the letter cards for the corresponding letter sounds (or by printing the letters, if appropriate) and then blend the sounds together to read the word. If a student is unsuccessful during independent practice, it is important to return to modeling and guided practice until each student can respond accurately. If the group reaches mastery, consider implementing this lesson with more challenging words.

Adaptations of Phonics Instruction with Word Boxes for Secondary Students

Explicit phonics instruction also may be beneficial for older students who struggle with word identification (McDaniel, Houchins, & Terry, 2013; Warnick & Caldarella, 2016). Although explicit phonics instruction may seem rudimentary for secondary students, basic phonics skills can be practiced using multisyllabic words that are age appropriate and learned in content areas (Casillas, Robbins, Allen, & Kuo 2012; Kim et al., 2017). For example, the word “concept” may be aligned with grade-level texts that students frequently use in their classroom. Choosing words that are relevant to students may increase motivation and engagement during phonics instruction (Lovett, Lacerenza, De Palma, & Frijters, 2011).

The preceding explicit lesson outline may be implemented by replacing letter cards with syllable cards for teaching multisyllabic words. The teacher selects a word formed with syllable cards that follows regular phonics patterns and syllable types that have been taught to students. The teacher presents a word formed with two or more syllable cards. Students use the pattern of consonants and vowels to determine the syllable type, which indicates how the vowel in the syllable is to be pronounced. After pronouncing each syllable separately, students then blend the syllables together to say the whole word.

For example, a teacher might present the syllable cards “con” and “cept” (see Figure 2). Students would be asked to identify that the single vowel in the syllable followed by one or more consonants indicates that each card contains a closed syllable. The vowels in closed syllables are pronounced with the short sound: /ŏ/ and /ĕ/. Each syllable starts with the letter “c.” When the “c” precedes the vowels “a,” “o,” or “u,” it typically represents the /k/ sound. When the “c” precedes the vowels “e” or “i,” it typically represents the /s/ sound. Hence, students can use their knowledge of the letter patterns to determine the pronunciation of the vowel in the syllable as well as the first consonant sound. After saying each syllable separately (con-cept), students then should blend the syllables to identify the entire word.

Figure 2. Syllable Cards

Quality explicit and systematic phonics instruction is difficult, but pivotal for students who are learning to read and those who need interventions due to reading difficulties (Ehri & Flugman, 2018). Practicing letter-sound correspondences using the word box and letter cards or multisyllabic words with syllable cards are examples of instructional tools that teachers can implement in explicit and systematic ways to support the reading development of their students.

Supplemental Materials for Teachers

Word Box Template

A graphic organizer designed to help students determine which letters represent the sounds heard in a given word. A graphic representing the word is provided with blank spaces for each sound to be filled in.

References

Brady, S. (2011). Efficacy of phonics teaching for reading outcomes: Indications from post-NRP research. In S. Brady, D. Braze, & C. Fowler (Eds.), Explaining individual differences in reading: Theory and evidence (pp. 69–96). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Casillas, A., Robbins, S., Allen, J., & Kuo, Y. L. (2012). Predicting early academic failure in high school from prior academic achievement, psychosocial characteristics, and behavior. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 407–420. doi:10.1037/a0027180

Ehri, L. C. (2014). Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18, 5–21. doi:10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

Ehri, L. C., & Flugman, B. (2018). Mentoring teachers in systematic phonics instruction: effectiveness of an intensive year-long program for kindergarten through 3rd grade teachers and their students. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 31, 425-456. doi:10.1007/s11145-017-9792-7

Keesey, S., Konrad, M., & Joseph, L. M. (2015). Word boxes improve phonemic awareness, letter–sound correspondences, and spelling skills of at-risk kindergartners. Remedial and Special Education, 36, 167-180. doi:10.1177/0741932514543927

Kim, J. S., Hemphill, L., Troyer, M., Thomson, J. M., Jones, S. M., LaRusso, M. D., & Donovan, S. (2017). Engaging struggling adolescent readers to improve reading skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 52, 357–382. doi:10.1002/rrq.171

Lovett, M. W., Lacerenza, L., De Palma, M., & Frijters, J. C. (2011). Evaluating the efficacy of remediation for struggling readers in high school. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45, 151–169. doi:10.1177/0022219410371678

McDaniel, S. C., Houchins, D. E., & Terry, N. P. (2013). Corrective reading as a supplementary curriculum for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 21, 240–249. doi:10.1177/1063426611433506

Murphy, K. A., & Farquharson, K. (2016). Investigating profiles of lexical quality in preschool and their contribution to first grade reading. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 29, 1745-1770. doi:10.1007/s11145-016-9651-y

Pelatti, C. Y., Piasta, S. B., Justice, L. M., & O’Connell, A. (2014). Language-and literacy-learning opportunities in early childhood classrooms: Children's typical experiences and within-classroom variability. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29, 445-456. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.05.004

Seymour, P. H. K., Aro, M., & Erskine, J. M. (2003). Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 143–174.

Warnick, K., & Caldarella, P. (2016). Using multisensory phonics to foster reading skills of adolescent delinquents. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 32, 317–335. doi:10.1080/10573569.2014.962199

Page not found - RPO "Association of Olympiad Winners"

Your name*

Your email*

Your telephone number*

What subject would you like to teach?*

Tell us briefly about your achievements in the Olympiad*

Please attach your CV*

File size should not exceed 20 MB / Available formats: doc / docx / rtf / pdf / html / txt

Please leave this field empty.

By clicking on the button, you accept the position and consent to the processing of personal data.

Your e-mail*

What region are you from?*

Tell us how we could cooperate*

Please leave this field empty.

By clicking on the button, you accept the position and consent to the processing of personal data.

Full name*

Your e-mail*

Your phone number*

Educational institution*

Tell us briefly about the situation with the Olympiad movement at school and what results you expect from cooperation with APO *

Please leave this field empty.

By clicking on the button, you accept the position and consent to the processing of personal data.

Your email

What subject are you interested in

Choose the most appropriate status Status not selectedStudentParentSchool representativeTeacher

By clicking on the button, you accept the position and consent to the processing of personal data.

Full name of the student

Student's date of birth

Class

Educational institution

City of educational institution

Parent's name

Parent's phone

Parent's email

Choose a group Group not selected

By clicking on the button, you accept the position and consent to the processing of personal data.

Full name of the student

Student's date of birth

Class

Educational institution

City of educational institution

Parent's name

Parent's phone

Parent's email

Choose a group Group not selected

Motivation letter File size must not exceed 2 MB / Available formats: doc / docx / rtf / pdf / html / txt

By clicking on the button, you accept the position and consent to the processing of personal data.

Full name

Telephone

Educational institution

City of educational institution

By clicking on the button, you accept the position and consent to the processing of personal data.

Full name

Telephone

Project / department

Job title

By clicking on the button, you accept the position and consent to the processing of personal data.

Name of the child

Name of educational institution

City of educational institution

Parent's name

Parent's phone

Parent's email

By clicking on the button, you accept the position and consent to the processing of personal data.

Login

Parent

I will buy courses for my child RegisterStudent

I will take courses myself RegisterSchool representative

I will order services for my educational institution and control their execution Register 90,000 development of spelling vigilance in younger studentsGavdan Svetlana Evgenievna, primary school teacher

MCOU Polbovskaya secondary school Chekhovsky municipal district of Moscow region0170 Improving the spelling literacy of students is one of the important tasks facing teachers. When studying the Spelling section, several tasks are performed: Work on spelling should start from the letter period. The period of learning to read and write is a very important stage for the formation of spelling skills. It was at this time that it was necessary to create the prerequisites for the successful development of spelling vigilance among students, to show schoolchildren the ambiguous correspondence between the sounding word and the written one, and observations must be made, moving not so much from letter to sound, but, on the contrary, from sound to letter. At the same time, students get an idea of the strong and weak positions of sounds. Since most spellings are spellings of weak positions, then from the point of view of the phonemic concept of Russian spelling, spelling vigilance can be defined as the ability to phonologically (positionally) evaluate each sound of a word, i. Further, students rise to a new level of knowledge and skills in spelling. This is a new stage in the process of forming conscious spelling skills, continuing and deepening the work begun earlier. It is here that the basic skill is honed - to detect sounds in words that allow ambiguous designation by letters, i.e. to foresee, to predict "mistakenly dangerous" spelling places. You can make a memo, which for a long time becomes a guide for finding the bulk of orthograms. This memo is called "What letters can not be written by ear." With such a memo in front of them, students can perform the most effective and at the same time the most difficult of the exercises that bring up spelling vigilance, namely: writing with gaps in spelling, or, as it is also called, writing with “holes”. Forming a spelling-literate letter is one of the most difficult tasks solved at school. Despite numerous studies conducted in the spelling methodology, it is very difficult to teach spelling to younger students. This is due both to the complexity of the spelling system of the Russian language itself, and to the fact that students, plunging into a sea of spelling rules, cannot grasp the logic of spelling, and perceive spelling as a set of disparate, unrelated “must” and “impossible”. One of the main learning objectives is to teach the student how to solve spelling problems accurately. At the same time, the following conditions for the formation of a spelling skill are distinguished: In the development of spelling vigilance, 6 stages are distinguished that the student must go through in order to solve the spelling problem: 1. 2. Determine whether it is checked or not, and if so, to which grammar and spelling topic it refers; remember the rule. 3. Determine how to solve the problem depending on the type of spelling. 4. Determine the “steps”, steps of the solution and their sequence, i.e. create an algorithm for solving the problem. 5. Solve the problem, i.e. perform a sequence of actions according to the algorithm. 6. Write a word and do a self-test. The result of teaching spelling depends on how developed the student's ability to set spelling tasks. In addition, the ability to do work on mistakes on your own and clearly remember how to do it right and how to be guided in solving the problem. Methods of independent work on mistakes can be different: self-correction by students of mistakes marked by the teacher with a special sign in the margins; self-explanation of errors; selection of test words; selection of words from the "Dictionary"; cross-checking of words in works by students; selection of words with the given spelling; writing out words and phrases with certain spellings from the dictation text and making sentences with them. Such methods of working on mistakes activate the mental activity of students, form their ability to consciously apply the learned rules. One of the most effective methods in the assimilation of spelling by students is the use of handouts. Using cards, you can organize individual, pair work, work in groups, work at different stages of the lesson (checking homework, studying a new topic, consolidating knowledge), working with an oral answer, working with a written answer, self-examination, mutual examination. Attentive and accurate performance of the proposed tasks helps students to consciously master the skill of competent writing. It is very important to know the degree of assimilation of the studied material by each student. When conducting test work, the teacher should keep a record of the gaps in the knowledge of the children, fixing them in a special notebook. Based on the analysis of errors in written work, various exercises can then be compiled. In Russian writing, the main section that determines the leading principle of orthography is the transmission of the phonemic composition of words by letters. It is to this section of spelling that most of the rules studied in the lower grades belong.

e. to distinguish which sound is in a strong position, and which is in a weak position, and, therefore, which one unambiguously indicates a letter, and which one can be indicated by different letters with the same sound. The ability to detect a sound that is in a weak position, first of all, is spelling vigilance.

Mastering this skill means delivering the student from the fear of making a mistake when performing various written works, primarily when expressing his own thoughts freely. The student is given permission to skip a letter if he does not know what to write in order to clarify it.

See the spelling in the word.

Learn more