Tales of b

Tales of Berseria – Destructoid

When I first wrote about Tales of Berseria, I held the belief that while the game wasn’t particularly groundbreaking or innovative, it nonetheless provided a highly polished and consistently excellent experience. At the time, I’d only put 21 hours into the game, which means that while I was approaching its half-way mark, I wasn’t quite at that point yet.

Now that I’ve seen the story of Tales of Berseria draw to a close, checked out some of its post-game content, and had a quick look at its predecessor — Tales of Zestiria — does my opinion of the game remain just as consistent as my initial impressions would have me believe? For the most part, yes.

Tales of Berseria (PS3 [Japan only], PS4 [PS4 Pro reviewed], PC)

Developer: Bandai Namco Studios

Publisher: Bandai Namco Entertainment

Released: August 18, 2016 (JP), January 24, 2017 (U. S. PS4), January 27, 2017 (EU and PC)

MSRP: $49.99 (PC), $59.99 (PS4)

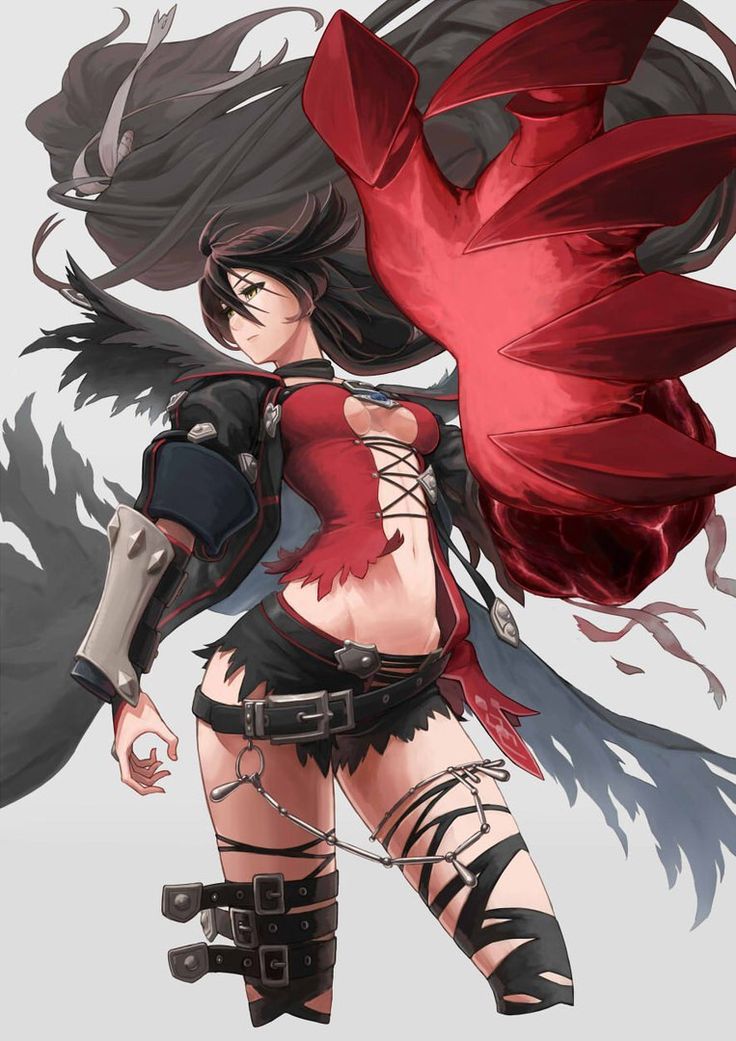

Right from the outset, it becomes immediately apparent that the narrative of Tales of Berseria takes a decidedly dark tone. You play as Velvet Crowe; a woman who, having endured three years of imprisonment after witnessing her sickly younger brother be ritualistically sacrificed by a man who she formerly trusted, sets out on a crusade for revenge against the individual who caused her so much despair.

While Tales of Berseria‘s narrative does contain several twists and turns — as well as some fairly significant revelations that may be immediately recognisable to anyone who has taken a cursory glance at Zestiria — Velvet’s primary goal remains the same throughout the 50-hour adventure. This isn’t to say that her motivations for revenge remain the same as the story progresses, but her primary objective is consistent throughout Berseria‘s runtime.

The game, itself, is also not short of emotionally-affecting or gut-wrenching moments. Tales of Berseria often tries to try and portray the main characters as villainous in nature, even if its actual antagonists can be significantly crueller in-action.

Tales of Berseria often tries to try and portray the main characters as villainous in nature, even if its actual antagonists can be significantly crueller in-action.

Joining Velvet on her revenge-fuelled rampage is a ragtag cast of eclectic and sometimes-morally-ambiguous individuals. These characters each have their own motivations for joining up with Tales of Berseria‘s ludicrously-dressed heroine, as well as their own goals and ideals. For instance, Eleanor often acts as a foil for Velvet’s more destructive tendencies, Laphicet can bring out the more human side of the game’s protagonist, and Magilou’s smug demeanour and penchant for terrible puns can often bring some much-needed levity to the table.

Like in other Tales games, Berseria also features optional skits that allow for the characters to elaborate on the situations that they find themselves in, provide more backstory, or serve as another form of comic relief. Some of these skits even showcase the best lines of dialogue that the game has to offer, and are well worth your time if you have any interest in Tales of Berseria‘s cast.

Alongside its quirky and likeable cast of characters, Tales of Berseria‘s greatest strength lies with its combat system. This real-time battle system is both fast-paced and responsive, and heavily emphasises stamina (which is referred to as a ‘Soul Gauge’) and resource management. At the start of each battle, party members will have a set number of Souls which can increase or decrease based on various criteria.

For instance, inflicting a status condition on an enemy or defeating them will increase a character’s Soul count by one. This, in turn, allows them to perform more actions on the battlefield, such as dodging, blocking or performing Artes. Likewise, should an enemy inflict a status condition upon one of your party members, that character’s Soul count will drop by one.

Party members also have access to ‘Break Souls,’ which allows them to perform some potentially devastating abilities on the battlefield. The trade-off to this, however, is that it will increase their opponent’s Soul count by one while also reducing their own by the same amount. The result of this is that it’s entirely possible for a player to misjudge the effect of their abilities and wind up bolstering their opponent’s abilities.

The result of this is that it’s entirely possible for a player to misjudge the effect of their abilities and wind up bolstering their opponent’s abilities.

Suffice it to say, knowing when to perform these abilities, when to back away from an enemy and knowing the opportune moment to strike is paramount to mastering Tales of Berseria‘s combat system. There is a downside, though, in that it’s entirely possible to button mash your way to victory in most cases on the game’s default difficulty setting. The combat system only shines on higher difficulty settings and when facing off against tougher bosses.

So, let’s talk about Tales of Berseria‘s visuals. From the moment you start this game, it becomes clear that it was built with the limitations of the PlayStation 3 in mind. This is because — in Japan, at least — it also saw a release on Sony’s decade-old home console. The result of this is that many of the environments seem somewhat simplistic in terms of design, and a many of the game’s textures appear blurry and blocky when viewed close-up.

From a technical perspective, Tales of Berseria is in no way an impressive game. Thankfully, the game does at least sport a rather pretty art style which, in-action, can look quite effective. Despite the dated graphics on offer, many environments, such as the Manann Reef and the game’s final dungeon, still managed to impress me from an artistic standpoint.

The other benefit to eschewing a more graphically intensive visual style is that it helps ensure that the game’s performance remains consistent and smooth. Rarely, if ever, did I experience any significant or noticeable dips in Tales of Berseria‘s framerate. No matter how chaotic an action sequence got, performance remained incredibly consistent throughout. I must stress, however, that I was only able to test this game out on a PS4 Pro, and it’s entirely possible that this may not be the case for owners of a base PS4 console.

Nonetheless, I’d love to see what could be accomplished should Bandai Namco Studios decide to drop Sony’s decade-old console when working on a future instalment in this series.

On the topic of environmental design, Tales of Berseria opts to forgo the more open-ended locales that were featured quite prominently in Zestiria in favour of much smaller, more constrained maps. These environments are often littered with collectables, such as herbs that increase a character’s stats, enemies to battle, Katz Spirits — which can be used to acquire various pieces of cosmetic gear — and treasure chests.

While this might be a bit of a letdown to anyone who would have preferred that Bandai Namco Studios refine or expand upon the more open-ended environments of Zestiria, I can’t help but find this change to be for the better. Tales of Berseria is a highly linear and guided affair. While the game does feature the occasional side-quest, these distractions aren’t the focus of Tales of Berseria. In this sense, the smaller and more linear environments complement this more focused and guided style of gameplay and storytelling rather nicely.

Unfortunately, Tales of Berseria‘s dungeons aren’t particularly excellent. Almost all the dungeons in the game consist of a series of corridors with the occasional branching path, and with puzzles that could be accurately described as “mindless.” Most of the puzzles contained within these dungeons involve finding and pressing a switch of some form to open the door required to progress, with little in the way of variation.

As I mentioned in my Review in Progress, the word “consistent” could easily be used to accurately describe the bulk my experience with Tales of Berseria. For the most part, I still agree with this sentiment. As I’ve already mentioned, the game’s framerate remains mostly stable, but I also found that the game’s story moves at a very consistent pace, with new areas and environments being introduced every few hours.

Sadly, this isn’t always the case, and there are a few circumstances where the game will force you to revisit previously-completed dungeons to progress through the story. This becomes especially prevalent in the game’s second half, where you’ll find yourself revisiting the prison island from Tales of Berseria‘s opening chapters with great frequency.

This becomes especially prevalent in the game’s second half, where you’ll find yourself revisiting the prison island from Tales of Berseria‘s opening chapters with great frequency.

The game’s difficulty, too, is relatively consistent. Never once did I feel as if the game required that I linger in an area for too long just so I can grind for experience points or equipment. By simply downing almost all the enemies that I came across, I never once found myself in a situation where I felt outmatched by any of the challenges that the game threw at me. Of course, this does change once you bump the difficulty to a higher setting — where enemies will be of a significantly higher level, and where healing is less effective — but anyone who intends to play the game on its Normal mode will likely never feel as if Tales of Berseria‘s challenges are insurmountable.

In this respect, I can’t help but come to the conclusion that Bandai Namco’s decision to offer level-boosting DLC is a poor one, as it may give off the impression that the game will do everything in its power to goad players into buying into what can only be described as a pay-to-win scheme. This isn’t the case, and while I won’t dictate what people should or shouldn’t do with their finances, I’d advise against buying this sort of content. Not only is it a form of “pay-to-win” DLC that further trivialises an already-easy game, but it’s also entirely unnecessary given that Tales of Berseria barely requires the player to grind for levels in the first place.

This isn’t the case, and while I won’t dictate what people should or shouldn’t do with their finances, I’d advise against buying this sort of content. Not only is it a form of “pay-to-win” DLC that further trivialises an already-easy game, but it’s also entirely unnecessary given that Tales of Berseria barely requires the player to grind for levels in the first place.

I also found it frustrating that Tales of Berseria completely disables the use of the PS4’s Share button throughout the duration of the game. As someone who takes a lot of screenshots of games, the decision to disable this feature was just a little bit irritating, even if it wasn’t a deal-breaker by any means.

Tales of Berseria may not be the most ambitious or innovative game ever, but that’s entirely okay. It may have a handful of issues, not least of which includes its forced backtracking, occasional reuse of dungeons and its uninspired puzzles. At the same time, its characters are often likeable and entertaining, its tale of revenge is intriguing, and its combat system is fast-paced and responsive. If you’re already a fan of — or are curious about getting into — the Tales series, this is one to check out.

If you’re already a fan of — or are curious about getting into — the Tales series, this is one to check out.

[This review is based on a retail build of the game provided by the publisher.]

Tales of Berseria Review - IGN

Tales Of Berseria

LoadingBy Meghan Sullivan

Updated: May 2, 2017 6:39 pm

Posted: Jan 23, 2017 5:00 pm

"Why do you think that birds fly?" This riddle is posed in the first hour of Tales of Berseria, the emotionally ragged semi-prequel to Tales of Zestiria that ripped my heart out again and again with its cautionary tale of a woman so bent on vengeance that every road she follows leads to perdition. By the time the credits rolled on this 45-hour long action RPG I still wasn't sure what the answer was, but I knew this: Berseria is the best Tales game I've played, and my favorite to date.Berseria's greatest strength lies in its ability to tell a different kind of story from those of its predecessors. Instead of the cheery, can-do spirit I've come to expect from the series, Berseria fully explores the darkest parts of the human heart. There's no real sunny side to the anti-heroine Velvet Crowe, who drives the plot with her unquenchable thirst for bloody vengeance on the man who took everything from her. Nor is there much hope of redemption for the memorable company she keeps, which includes the enraged pirate Eizen, the mouthy and detached witch Magilou, and the fratricidal demon Rokurou. These characters reflect just how emotionally broken their world has become in the face of multiple calamities. Only the fragile Malak (spirit) Laphi and the earnest Exorcist Elenor keep this ragtag group anchored in hope and distinct from the actual villains. Even then, the ties that bind them threaten to come undone as their search for the truth behind the theo-political machinations of a tight group of elites collides with their need for personal vengeance.Loading

There's no real sunny side to the anti-heroine Velvet Crowe, who drives the plot with her unquenchable thirst for bloody vengeance on the man who took everything from her. Nor is there much hope of redemption for the memorable company she keeps, which includes the enraged pirate Eizen, the mouthy and detached witch Magilou, and the fratricidal demon Rokurou. These characters reflect just how emotionally broken their world has become in the face of multiple calamities. Only the fragile Malak (spirit) Laphi and the earnest Exorcist Elenor keep this ragtag group anchored in hope and distinct from the actual villains. Even then, the ties that bind them threaten to come undone as their search for the truth behind the theo-political machinations of a tight group of elites collides with their need for personal vengeance.LoadingBerseria fully explores the darkest parts of the human heart.

“At first I had a hard time believing the people Velvet kidnapped, cajoled, or manipulated into following her had reason to stay by her side as long as they did.

Then, as their personal tragedies unfurled and the characters indulged in the usual dialogue skits Tales is known for, I began to understand their growing camaraderie. I smiled whenever Rokurou and Eizen disagreed to agree, laughed at Magilou's tactless jokes, and held my breath nervously whenever Eizen and Velvet clashed over what to do next. ("If you die, you die alone," the pirate growls ominously during one very tense scene.) Each character is given sufficient time in the spotlight and with each other, which allowed me to invest in their well being as individuals and as a group. I can barely remember the names of any Tales heroes that came before Berseria, but I feel like I'll remember this motley crew for a long time to come.LoadingWhile Berseria flips the script on Tales' normally sunshine-filled stories, the brawler-inspired combat stays pretty much the same, with a few welcome tweaks that make it feel smooth and responsive. A variation of the Linear Motion Battle System that lets you run around a 3D battlefield returns, but now instead of using a move-governing mechanic, each action is tied to a character's Soul Gauge, which depletes every time a party member performs a special skill (Arte) in battle.

Then, as their personal tragedies unfurled and the characters indulged in the usual dialogue skits Tales is known for, I began to understand their growing camaraderie. I smiled whenever Rokurou and Eizen disagreed to agree, laughed at Magilou's tactless jokes, and held my breath nervously whenever Eizen and Velvet clashed over what to do next. ("If you die, you die alone," the pirate growls ominously during one very tense scene.) Each character is given sufficient time in the spotlight and with each other, which allowed me to invest in their well being as individuals and as a group. I can barely remember the names of any Tales heroes that came before Berseria, but I feel like I'll remember this motley crew for a long time to come.LoadingWhile Berseria flips the script on Tales' normally sunshine-filled stories, the brawler-inspired combat stays pretty much the same, with a few welcome tweaks that make it feel smooth and responsive. A variation of the Linear Motion Battle System that lets you run around a 3D battlefield returns, but now instead of using a move-governing mechanic, each action is tied to a character's Soul Gauge, which depletes every time a party member performs a special skill (Arte) in battle. Depleting a character's Soul Gauge allows enemies to more easily deflect attacks, while maxing out a character's Soul Gauge allows you to activate Break Souls, a temporary state where a character's combo limits are ignored and they can use a unique set of skills – such as Velvet's hard-hitting Consuming Claw-to take a bite out of the enemy's health and inflict a status effect. Although the Soul Gauge will replenish over time, I found it much more fun to hurry the process along by pounding souls out of an enemy while trying to avoid a similar beatdown. I really like this new system because it adds a bit of sensible strategy to the gameplay without feeling like I'm being forced to conserve or use up energy just for the sake of it.

Depleting a character's Soul Gauge allows enemies to more easily deflect attacks, while maxing out a character's Soul Gauge allows you to activate Break Souls, a temporary state where a character's combo limits are ignored and they can use a unique set of skills – such as Velvet's hard-hitting Consuming Claw-to take a bite out of the enemy's health and inflict a status effect. Although the Soul Gauge will replenish over time, I found it much more fun to hurry the process along by pounding souls out of an enemy while trying to avoid a similar beatdown. I really like this new system because it adds a bit of sensible strategy to the gameplay without feeling like I'm being forced to conserve or use up energy just for the sake of it.Battles have a more cohesive flow.

“A few other nice features include how Artes are conveniently hotkeyed to the Playstation 4's face buttons and can be swapped out at any time, more responsive blocking and dodging, and the ability to spend points tied to the Blast Gauge meter.

These points either trigger a character's fun-to-watch Mystic Arte (My favorite is Magilou's Ascending Angel, where she stretches a paper doll to impossible lengths and then slaps the crap out of multiple enemies on the battlefield) or can be partially allocated to activate Switch Blast, where reserve characters gain a combat advantage-such as an extra soul-whenever they switch places with an active party member. These additions give battle a more cohesive flow, helped by a mostly well-behaved camera and enjoyable music. (For those who enjoy playing with friends, superfluous but serviceable multiplayer during battle is also available.)LoadingThe only issue I had was learning the terms and conditions for when and how to effectively use Break Souls and Switch Blast. It was tricky, but once I deciphered Berseria's playbook I had a hellishly good time dishing out punishment to lizardmen and wolves, and I got immense satisfaction using the scraps of metal and ingredients they left behind to enhance equipment and whip up mouth-smacking, stat-boosting feasts between battles.

These points either trigger a character's fun-to-watch Mystic Arte (My favorite is Magilou's Ascending Angel, where she stretches a paper doll to impossible lengths and then slaps the crap out of multiple enemies on the battlefield) or can be partially allocated to activate Switch Blast, where reserve characters gain a combat advantage-such as an extra soul-whenever they switch places with an active party member. These additions give battle a more cohesive flow, helped by a mostly well-behaved camera and enjoyable music. (For those who enjoy playing with friends, superfluous but serviceable multiplayer during battle is also available.)LoadingThe only issue I had was learning the terms and conditions for when and how to effectively use Break Souls and Switch Blast. It was tricky, but once I deciphered Berseria's playbook I had a hellishly good time dishing out punishment to lizardmen and wolves, and I got immense satisfaction using the scraps of metal and ingredients they left behind to enhance equipment and whip up mouth-smacking, stat-boosting feasts between battles.

I had a hellishly good time dishing out punishment to lizardmen and wolves.

“The one place where Berseria doesn't shine as brightly is the garden-variety locations and lack of deep exploration. Our ragtag adventurers travel across lovely but linear flower fields and dreary marshes connected by nodes, or via a ship that travels around a large archipelago on a 2D map. While I appreciated the occasional ocean cliff to ascend or colorful puzzle dungeon to solve, for the most part I was pretty bored by the generic scenery. Lots of mandatory backtracking and limited fast-travel didn't help, even with the introduction of the "geoboard," a clunky magical surfboard that let me get from point A to point B a little faster than normal.

There were a few things that managed to keep my sense of exploration alive. One was the unlockable treasure chests containing collectible costumes scattered throughout the world. These cat-eared, bubble-gum pink "Katz Boxes" made me squeal with delight whenever I saw them, and I became obsessed with gathering magical orbs called Katz Spirits to try to open as many as I could. Minigames and battle arenas that helped sharpen my combat skills were also a welcome reprieve from the tedium of ping-ponging between the same areas, and I enjoyed sending a pirate ship around the world to collect new recipes and valuable treasure for me.

Minigames and battle arenas that helped sharpen my combat skills were also a welcome reprieve from the tedium of ping-ponging between the same areas, and I enjoyed sending a pirate ship around the world to collect new recipes and valuable treasure for me.

Berseria gives you the choice of hearing Japanese or English, and it’s a good thing I went with English. Not because the Japanese cast failed to perform well, but rather because the subtitles are incredibly strange. Lines like “That’s gruesome by any standards” became a chuckle-worthy “that’s goose by any standards,” and “even death can be a kind of release” became “even depth can be a kind of release,” turning the adage into a riddle. Was this the devious doings of autocorrect? A clumsy translation? Who knows, but it was a needless distraction. Luckily, the English voice cast hits it out of the park, and their strong deliveries were able to evoke a wide spectrum of emotions in me, including tears and belly laughter. It’s proof that a good voice cast can make all the difference in how much I enjoy the story. Loading

Loading

Tales of Berseria is a surprisingly strong showing for this long-running series. Its tragic story of broken people fighting on the wrong side of history makes it utterly compelling, and its well-tuned combat more than makes up for its lack of interesting environments. Simply put, this is a tale too heartbreaking to miss, or to forget.

In This Article

Tales Of Berseria

Bandai Namco

Rating

ESRB: TeenPlatforms

PlayStation 4PCPlayStation 3Tales of Berseria Review

great

It's good to be bad in Tales of Berseria, among the most emotional and darkest of this long-running RPG series.

Meghan Sullivan

LoadingFairy tales with the letter "B" 😺 read and listen for girls and boys 🌟

B

Mowgli's Brothers 🙉 Rudyard Kipling

zlatarix April 25, 2021

The Tale of Mowgli's Brothers high in the mountains It was a very hot evening in the Zionian mountains. Father Wolf woke up after a day's rest, yawned, scratched himself and one after another ...

Father Wolf woke up after a day's rest, yawned, scratched himself and one after another ...

Read more +

Bogatyrev's gauntlet 🦾Bazhov P.P.

Olimpia January 12, 2021 Fairy tale Bogatyryov's gauntlet In these places, before, a simple person would not have been able to resist: the beast would have seized or the vile would have overcome. Here ...

Read more +

Fugitive soldier and devil 😈 Afanasiev A.N.

Olimpia January 12, 2021

Reading the fairy tale "The Runaway Soldier and the Devil" by A. N. Afanasyev Fairy tale "The Runaway Soldier and the Devil" The soldier asked for leave, got ready and went on a campaign. I walked and walked, I couldn't see water anywhere, whatever ...

Read more +

Bukhtan Bukhtanovich 🕴️♂️ Afanasiev A.N.

Olimpia January 11, 2021

A fairy tale for reading to children Bukhtan Bukhtanovich Afanasyeva Alexandra Bukhtan Bukhtanovich In a certain kingdom, in a certain state, a certain Bukhtan Bukhtanovich lived and visited; at Bukhtan . ..

..

Read more +

Laborer 😺 Afanasiev A. N.

Olimpia January 11, 2021

Reading the fairy tale by Afanasiev Alexander N. "The farm laborer" Laborer Once upon a time there was a man; he had three sons. The eldest son went to hire himself as a laborer; came to the city and hired himself to a merchant, and he ...

Read more +

Burenushka 🌚 Afanasiev A. N.

Olimpia January 9, 2021

Read the fairy tale "Burenushka" Alexander Afanasiev Burenushka Not in any kingdom, not in any state was the king and the queen lived, and they had one daughter, Marya the princess. And how she died ...

Read more +

Fearless ⚡ Afanasiev A. N.

Olimpia January 8, 2021

Wonderful fairy tale "Fearless" Alexandra Afanasyeva Fearless In a certain kingdom lived a merchant's son; strong, brave, from a young age was not afraid of anything; he wanted passion1 . ..

..

Read more +

Elder Mother 👩 Andersen Hans Christian

Storyteller January 4, 2021

Read Elder Mother Andersen Hans Christian Fairy tale Elder Mother One little boy caught a cold once. Where he got his feet wet, no one could understand - the weather was ...

Read more +

Barmaley 👨 Chukovsky K.I.

Storyteller November 18, 2019

Reading Korney Chukovsky's fairy tale "Barmaley" Barmaley Part one Small children! No way Don't go to Africa Walk in Africa! Sharks in Africa Gorillas in Africa In ...

Read more +

Barankin, be a man! 👌 Medvedev V.V.

Storyteller October 10, 2019

Barankin, be a man! Tale of Valery Medvedev Fairy tale Barankin, be a man! (Thirty-six events from the life of Yura Barankin) Part one. Barankin, to the board! Event ...

Read more +

Snow White ❄ Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm 🔊 🎥

Storyteller October 7, 2019

The fairy tale of Snow White for children from the Brothers Grimm Fairy tale Snow White It was in the middle of winter, snowflakes were falling like fluff from the sky, and the queen was sitting at the window - its frame was made of . ..

..

Read more +

Bang! 💥 Donald Bisset

Detyam June 7, 2017

Bang! Donald Bisset fairy tale Fairy tale bam! In a hole in the wall in a room in a house in an alley in a city in a country in a world in the universe there lived a mouse. Her name was Alice. Once Alice was lying ...

Read more +

Blackie and Reggie ⭐ Donald Bisset

Detyam June 7, 2017

Blackie and Reggie Donald Bisset fairy tale The Tale of Blackie and Reggie Once upon a time there lived a horse. Her name was Reggie. In the mornings, Reggie delivered milk and every time she met her friend on the way ...

Read more +

Bobik visiting Barbos 🐶 Nosov N.N.

Storyteller May 13, 2017

Children's fairy tale "Bobik visiting Barbos" for children Fairy tale Bobik visiting Barbos Once upon a time there was a dog Barboska. He had a friend - the cat Vaska. Both of them lived with their grandfather. Grandfather went to ...

He had a friend - the cat Vaska. Both of them lived with their grandfather. Grandfather went to ...

Read more +

Bukhtan Bukhtanovich 🦊 Russian folk tale

Kids April 3, 2017

Bukhtan Bukhtanovich Russian folk tale Fairy tale Bukhtan Bukhtanovich Look out the window: what do you see? And under Tsar Pea there was a field here; there was a stove in the field; Bukhtan lay on the stove ...

Read more +

On the issue of processing and retelling Russian folk tales for children

The article discusses ways of adapting the texts of Russian folk tales to the perception of children.

Keywords: processing, retelling, folk tale

Adaptation in one of the meanings of this word is the simplification (facilitation) of the text for an insufficiently prepared reader. Adaptation in children's literature is a much more complex, deep process that requires the writer (poet) to have artistic skills and a high level of professionalism. Like any children's writer, processor or narrator must have "an exalted, educated mind, an enlightened view of objects" 1 . Sometimes he has to act as a textual critic, folklorist. He must know the psychology of children's perception, the language and style of children's literature.

Adaptation in children's literature is a much more complex, deep process that requires the writer (poet) to have artistic skills and a high level of professionalism. Like any children's writer, processor or narrator must have "an exalted, educated mind, an enlightened view of objects" 1 . Sometimes he has to act as a textual critic, folklorist. He must know the psychology of children's perception, the language and style of children's literature.

An important role here is played by the author's individuality of the processor or narrator.

The processing and retelling of Russian folk tales is a topic that deserves serious scientific research. Fairy tales are not only entertaining children's reading. They are a moral idea preserved in the memory of the people and embodied in a figurative, clear and precise word (the triumph of justice and truth, the victory of good over evil, the ideal image of a folk hero). The liveliness and inventiveness of the people's mind are felt in the fairy tale with particular obviousness.

The path that a folk tale has gone from the scientific recording of fairy texts by folklorists to the literary processing of its variants for children is long and thorny.

Despite the fact that fairy tales have existed in Rus' since ancient times, their records appear only in the 17th century. Since then, the word "fairy tale" has been used in its modern sense. Before that, there were “tales”, “bahari”. The well-known folklorist B. M. Sokolov explains this by “the general ecclesiastical trend of ancient Russian literature, which in every possible way resisted the manifestation of secular, especially oral literature in the book” (Sokolov, 1930:41).

It is interesting that in the annals, and in various legends, and in the lives, one can find many echoes and reworkings of oral folk art. Suffice it to refer to at least the well-known "Life of Peter and Fevronia of Murom", almost entirely consisting of fairy tale motifs about the "wise maiden" - the riddle and adviser.

In the XVI-XVII centuries. Eastern and Western fairy tales that came to Russia began to spread widely in manuscripts. For example, we can cite the well-known fairy tales about Yeruslan Lazarevich, about Bova Korolevich, about Shemyakin's court and others. According to B.M. Sokolov, "all these tales were strongly Russified and even in their written form acquired the appearance of a purely Russian fairy tale style" (ibid.).

One of the first records of oral Russian fairy tales belongs to the Englishman Collins. Traveling under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in Russia, Collins recorded two interesting tales about Tsar Ivan the Terrible.

The penetration of oral fairy tales into literature was facilitated by the fact that literate Russian people diligently rewrote works of a fairy tale character. But these were for the most part the stories-tales of a foreign origin mentioned above. They also spread in the form of a lubok. Russian fairy tales are rarely found in manuscripts of the 18th century.

Under the influence of the popularity in Western Europe of the adventurous magical chivalric romance and the "enchanting" fairy tale (for example, the famous French collection of fairy tales by Ch. Perrault, 1697) in our country, similar collections of "chivalrous" gallant tales began to be compiled, where only Russian fairy tales and epics remained names and some details. An example of this is the collections of M.D. Chulkova - “The Mockingbird, or Slavic Tales” (1766-1768), “Russian Tales Containing the Most Ancient Narratives of Glorious Bogatyrs; folk tales and others, adventures remaining through retelling” (1780-1783), “Slavonic Evenings, or the Adventures of the Slavic Princes” by M.I. Popova (1770-1771). There were almost no authentic Russian fairy tales in such collections. So, B.M. Sokolov singles out only the collection Russian Tales, Collected and Published by P. Timofeev (1787) with several original entries (ibid.: 5).

The authors of the textbook "Russian Folk Poetry" note the collections of S. Drukovtsev "Grandmother's Tales" (1778), "Owl, Night Bird" (1779). In them, “some retellings of fairy tales are given not only with the preservation of folk plots and images, but partly also of the language: about how a husband “taught” a negligent wife, and about how a peasant deceived a stupid lady” (Novikova, 1969: 159). The small number of authentic records largely depended on the literary tastes of the then reading society. For example, the following fact is typical. In the collection "Russian Fairy Tales" M.D. Chulkov introduced three really real folk tales. But this is precisely what caused a negative reaction from critics: “Of the new tales added by the publisher, some, somehow about the thief Timokha, Gypsies, etc., with greater benefit for this book, could be left for the simplest taverns and drinking houses, for the most uncomplicated a peasant can invent dozens of such without difficulty, which if he betrays all the seals, it will be a pity for paper, pens, ink and printing letters, without mentioning the work of gentlemen writers ”(Sokolov, 1930:27).

Drukovtsev "Grandmother's Tales" (1778), "Owl, Night Bird" (1779). In them, “some retellings of fairy tales are given not only with the preservation of folk plots and images, but partly also of the language: about how a husband “taught” a negligent wife, and about how a peasant deceived a stupid lady” (Novikova, 1969: 159). The small number of authentic records largely depended on the literary tastes of the then reading society. For example, the following fact is typical. In the collection "Russian Fairy Tales" M.D. Chulkov introduced three really real folk tales. But this is precisely what caused a negative reaction from critics: “Of the new tales added by the publisher, some, somehow about the thief Timokha, Gypsies, etc., with greater benefit for this book, could be left for the simplest taverns and drinking houses, for the most uncomplicated a peasant can invent dozens of such without difficulty, which if he betrays all the seals, it will be a pity for paper, pens, ink and printing letters, without mentioning the work of gentlemen writers ”(Sokolov, 1930:27).

At the end of the XVIII century. collections were often printed, in which alterations and retellings of fairy tales predominated. The compilers did not pursue scientific goals - they sought to give readers only an easy, entertaining reading. Even the titles of these books say a lot: “The Cure for Thought and Insomnia, or Real Russian Fairy Tales” (St. Petersburg, 1786), “The Jolly Old Man Telling Ancient Moscow Times” (St. Petersburg, 1790) and others.

In the first quarter of the XIX century. cheap editions of fairy tale books were popular. In popular publications, folk tales were rarely found in their original form, without alteration. The language of these publications, as a rule, is tasteless, the style is far from folk. Criticism treated popular literature negatively, calling it "base", "bazaar".

Collector of fairy tales A.N. Afanasiev wrote in 1854 about the publications of folk tales in the first half of the 18th century: “... collections of fairy tales published at different times will not give much to a lover of folk literature; they were compiled and printed by people who were little prepared for this matter and with goals that were not at all archaeological or literary. In fairy tales, they saw one fun worthy of the lower stratum of society or childhood, and therefore everyone considered it his full right to remake them in his own way. Our book trade was flooded and still continues to be flooded with a multitude of gray, unpleasant, abundant typographical errors in which, under the name of folk Russian fairy tales, such distorted ones are printed that it is difficult to find in them not only traces of nationality, but also the very meaning. Here, translations, and alterations, and additions are allowed - the fruit of the publishers' own leisurely imagination, and apt and expressive folk speech is replaced by colorless and not always correct prose.0137 2 (Afanasiev, 1957: 384-385).

In fairy tales, they saw one fun worthy of the lower stratum of society or childhood, and therefore everyone considered it his full right to remake them in his own way. Our book trade was flooded and still continues to be flooded with a multitude of gray, unpleasant, abundant typographical errors in which, under the name of folk Russian fairy tales, such distorted ones are printed that it is difficult to find in them not only traces of nationality, but also the very meaning. Here, translations, and alterations, and additions are allowed - the fruit of the publishers' own leisurely imagination, and apt and expressive folk speech is replaced by colorless and not always correct prose.0137 2 (Afanasiev, 1957: 384-385).

V.G. Belinsky, in his article “On Folk Tales” (1844), laments the same thing: “There are many fairy tales in Rus'. Mr. Sakharov lists up to 120 titles, speaking only of those that have made it into print. But this wealth, in essence, differs little from perfect poverty: almost all these tales have come down to us in a distorted form, and most of the people that have survived to this day have not yet been collected. Not only our writers of the last century, but even common people who were engaged in the so-called. popular prints, distorted them" 3 .

Not only our writers of the last century, but even common people who were engaged in the so-called. popular prints, distorted them" 3 .

According to B.M. Sokolov, “the awakening of a lively interest in folk tales manifests itself in the late 10s and especially in the 20s. 19th century in connection with the influence of the romantic trend that came to us from the West in the field of literature and philosophy, with the principle of “nationality” cultivated by it, with the desire to comprehend the “spirit of the people”, with an interest in ancient times” (Sokolov, 1930: 6).

The fairy tale begins to be valued as a treasury of the native language, as a means of education, and - what is especially important - serves as material for the creation of original works of literature.

Many writers of that time turned to recording and artistic processing of fairy tales. We can talk about the reproduction of fairy tales in literary form from the 30s. 19th century Then the fairy tales of V.A. Zhukovsky and A.S. Pushkin, "Humpbacked Horse" P.P. Ershova, “Evenings on a farm near Dikanka” by N.V. Gogol and others.

19th century Then the fairy tales of V.A. Zhukovsky and A.S. Pushkin, "Humpbacked Horse" P.P. Ershova, “Evenings on a farm near Dikanka” by N.V. Gogol and others.

The collection of Russian folk tales begins. The first one can be called V.I. Dal, who recorded up to a thousand fairy tales. And these are records of truly folk tales.

In 1838, a small collection of Bogdan Bronnitsyn (a pseudonym of an unknown author) “Russian Folk Tales” appeared, including five fairy tales (“About Vasilisa, a golden braid, uncovered beauty, and Ivan Pea”, “About the hero Gol Voyansky”, “About the unfortunate arrow", "About Ivan Kruchin, a merchant's son", "About a silver saucer and a bulk apple") 4 . These tales were rather successful adaptations of records “from the words of a hozhal storyteller, a peasant from a village near Moscow, who was told by an old man, his father” (as the author himself reports in an address to readers). “They have a remarkable warehouse of the story, representing for the most part a collection of Russian poems of various sizes. The very content of the tales seemed curious to me, representing the ingenuity of the imagination with all the simplicity of folk speech.0137 5 .

The very content of the tales seemed curious to me, representing the ingenuity of the imagination with all the simplicity of folk speech.0137 5 .

Undoubtedly, the plots of real folk tales formed the basis of these fairy tales.

But this edition also suffers from shortcomings. The book style turned, for example, the tale of Vasilisa into a story similar to imaginary tales of the 18th century.

Nevertheless, the famous storyteller V.P. Anikin, not without reason, noted that “it was precisely from Bogdan Bronnitsyn that writers embarked on the right path of processing fairy tales” (Anikin, 1970: 5).

Folklore collections by I.P. Sakharov, in particular his "Russian folk tales" (St. Petersburg, 1841). But in most cases, he gave only texts “corrected” in a pseudo-folk spirit from various sources known before him (for example, epics from the collection of Kirsha Danilov, popular tales from the collection of M. Chulkov), and sometimes texts that were clearly falsified, for example, composed by himself the tale of Ankudin.

It is the collections of B. Bronnitsyn and I.P. Sakharov (due to the inclusion of the last six original records) AN. Afanasiev singles out from all other printed collections as "deserving attention" 6 .

One can also note a small book by E.A. Avdeeva "Russian folk tales for children" (St. Petersburg, 1844), which included seven truly folk (in accurate recording) fairy tales about animals.

"Folk Russian Tales" A.N. Afanasyev (8 issues from 1854 to 1886) opened the publication of authentic folk texts in Russia. Following this collection, which has become a classic, many fairy-tale collections come out.

The heyday of collecting and studying Russian folk tales falls on the beginning of the 20th century. The greater seriousness of collecting work was facilitated by the work that arose at the beginning of the 900s at the Russian Geographical Society, a special Fairy Tale Commission chaired by S.F. Oldenburg. This is the time for a scientific approach to collecting fairy tales.

The famous writer and lexicographer V. I. Dal collected and processed folk tales, and back in 1832 published them in a separate collection “Russian Fairy Tales. Five first."

Working on his fairy tales, V.I. Dahl did not set himself the goal of making them children's reading. The folk language is the main thing for him in fairy tales: “I didn’t need fairy tales in themselves,” he writes, “but the Russian word, which we have in such a pen that it could not appear to people without a special pretext and reason — a fairy tale served as a reason. I set myself the task of acquainting my fellow countrymen with the folk language and dialect, which opens up such free space and wide revelry in a folk tale ... " 7 .

IN AND. Dal introduced a new stylistic device of fairy tale prose into Russian literature, brilliantly embodied later in the fairy tales of N.S. Leskova, A.M. Remizova, P.P. Bazhov.

It should be noted that the method of work of V. I. Many contemporaries generally considered Dahl over folklore to be “destructive”, since the author often decisively intervened in the text of a fairy tale.

I. Many contemporaries generally considered Dahl over folklore to be “destructive”, since the author often decisively intervened in the text of a fairy tale.

To critics V.I. Dahl also treated V.G. Belinsky, who considered folklore inviolable. He was of the opinion that the Russian folk tale has its own meaning only in the form in which it was created by folk fantasy. But the writers defended their right to a literary version. In the middle of the XX century. one of the masters of retelling Russian folk tales for children A.N. Nechaev wrote: “A literary version is justified when it does not distort the people’s intention, when it becomes one of the best, and not arbitrary options, when the image of the folklore hero chosen by the writer is supplemented and clarified, remaining itself” 8 .

A.S. Pushkin highly appreciated V.I. Dal - "a gifted writer and an outstanding connoisseur of folk life" - and advised the latter to write a novel and fairy tales. It is even known that A. S. Pushkin himself gave him the content of the tale of Georgy the Brave and the warrior. And there is an assumption that the storyteller, in turn, introduced the great poet to the folk tale about the fisherman and the fish, which A.S. Pushkin translated it in his own way.

S. Pushkin himself gave him the content of the tale of Georgy the Brave and the warrior. And there is an assumption that the storyteller, in turn, introduced the great poet to the folk tale about the fisherman and the fish, which A.S. Pushkin translated it in his own way.

In 1871 V.I. Dahl undertook the publication of two books for children in his own processing: “The first first book for a semi-literate grandson. Fairy tales, songs, games” (St. Petersburg) and “Pervinka is different. A literate grandson with an illiterate brethren. Tales, songs, games "(St. Petersburg). In addition, he edited and "revised" the collections of his wife E.L. Dahl (Sokolova) "Crumbs" (St. Petersburg, 1870), "Pictures from the life of Russian children" (St. Petersburg; M., 1875).

In the preface to "The First First Semi-literate Grandson" V.I. Dal writes: “... parents and educators, not knowing what they are doing, direct our entire spiritual and moral life to a foreign land - and a person who is not confined to his soil from the swaddling cloth will hardly take root in it. And how can he be associated with her, if he did not feed on her juice and hardly knows her? 9 .

And how can he be associated with her, if he did not feed on her juice and hardly knows her? 9 .

The first scientific publisher and editor-compiler of Russian fairy tales for children was Alexander Nikolaevich Afanasiev (1826-1871).

According to the well-known storyteller V.P. Anikin: “Without it, the treasures of fairy-tale folklore could be lost, perished. Folklore, passed down from generation to generation for many centuries, entered a time of crisis in the middle of the 19th century, when the creative thought of the people, disturbed by social novelty, rushed to new objects - and the full-fledged art of telling fairy tales became less and less common. Afanasiev, with his publication, saved the most valuable works of art of the people from oblivion for future generations. Fairy tales have retained all the depth of meaning, the richness of fiction, the freshness of the people's moral feeling expressed in them, the brilliance of the poetic style.0137 10 . Afanasiev extracted from the archive of the Russian Geographical Society all the fairy tales stored there. And these stories are not from any one locality. At his disposal was the all-Russian property. I gave him my notes and V.I. Dal.

Afanasiev extracted from the archive of the Russian Geographical Society all the fairy tales stored there. And these stories are not from any one locality. At his disposal was the all-Russian property. I gave him my notes and V.I. Dal.

A.N. Afanasiev considered it necessary to accompany the text of fairy tales with “necessary philological and mythological notes” (letter to A.A. Kraevsky dated August 14, 1851) 11 . “The purpose of this publication,” writes A.N. Afanasiev, - to explain the similarity of fairy tales and legends among different peoples, to point out their scientific and poetic significance and to present examples of Russian folk tales.

This is exactly what the representatives of the so-called "mythological school" called for. “This is a direction in the science of folklore,” wrote V.P. Anikin, - is characterized by a special method. Its adherents saw in the origin of folk-poetic images a dependence on ancient myths and reduced the meaning of folklore works to the expression of a few concepts and ideas generated by the deification of nature - the sun and thunder ” 12 .

Here it is appropriate to recall the article written in our days by V.V. Vinogradov "Water from a hoof" about the fairy tale "Sister Alyonushka and brother Ivanushka". The author analyzes what the water from the hoof, which the hero of the fairy tale drank, represents at the mythological level. We are talking about tracer stones with "animal" semantics, about the magical power of water from the traces left by symbolic people and animals. “Fairy tale semantics proper can only be interpreted on the basis of mythological origins” 13 , - concludes V.V. Vinogradov.

Despite some serious shortcomings, the collection of A.N. Afanasiev is the most important collection of Russian fairy-tale material for folklore science, which has not yet been quantitatively surpassed. It serves as a source of numerous scientific research by Russian and foreign folklorists, as well as the artistic creativity of writers.

Interestingly, the fairy tales published by A. N. Afanasiev, echo the work of many Russian poets and writers (A.S. Pushkin, P.P. Ershov, S.T. Aksakov, N.S. Leskov and others). As V.P. Anikin rightly noted, “there are a lot of meetings of literary creativity and fairy tales of the people on the pages of the Afanasiev collection” 14 .

N. Afanasiev, echo the work of many Russian poets and writers (A.S. Pushkin, P.P. Ershov, S.T. Aksakov, N.S. Leskov and others). As V.P. Anikin rightly noted, “there are a lot of meetings of literary creativity and fairy tales of the people on the pages of the Afanasiev collection” 14 .

So, in the fairy tale "Shabarsha" we recognize Pushkin's Balda. In another fairy tale (from the cycle “Don’t like it - don’t listen”), there is a nickname for the priest, which was used by A.S. Pushkin - "oatmeal forehead". “Having re-read your book myself, I did not hide it from my children either, and even my six-year-old Vyachko crawled into it with his little eyes ... As a result of this, I, in the capacity of a father, turn to you with the most humble request: is it possible, together with this publication, to scholars to print fairy tales for children as well - a bare text, literary spelling, translation of words that are not generally understood (under the line) and with the release of those fairy tales that it is inappropriate for children to read? (quoted from: Georgian, 1987: 114) — wrote the famous Russian ethnographer I. I. Sreznevsky.

I. Sreznevsky.

This is a letter from I.I. Sreznevsky was published by A.E. Gruzinsky is the first biographer of the Academy of Sciences. Afanasiev, who had materials from the archive of the Russian folklorist. He also published the second letter of I.I. Sreznevsky, dated 1858, where the same wish sounds again: “Your merit, I repeat my old song, would be even greater if you had not forgotten our children (I myself have a small fraction of them, of which four are literate therefore I speak boldly)" (ibid.: 115). and A.N. Afanasiev did not forget.

Two volumes of "Russian Children's Tales" were published only in 1870, a year before the folklorist's death.

Researcher of creativity AN. Afanasyeva A. Nalepin explains "the slowness of the author is not at all his academic slowness." “The fact is that the book “Russian Children's Tales” was addressed by the author to young readers, and this circumstance determined the special thoroughness and scrupulousness in its creation. Adult people could forgive the author for minor shortcomings, but a child is a reader of a special kind, who does not tolerate falsehood and slurred tongue twisters. That is why there was such a long publishing history of this amazing book with beautiful clear drawings by N. Karazin, which only from 1883 to 19In 1818 it went through seventeen editions - a fact in itself amazing for those times” 15 .

Adult people could forgive the author for minor shortcomings, but a child is a reader of a special kind, who does not tolerate falsehood and slurred tongue twisters. That is why there was such a long publishing history of this amazing book with beautiful clear drawings by N. Karazin, which only from 1883 to 19In 1818 it went through seventeen editions - a fact in itself amazing for those times” 15 .

It is known that Afanasiev, before publishing his scientific collection, literary processed some records of folklore texts. He did not see anything shameful in the stylistic alteration of the tale, its style. But the folklorist never considered the pre-processed complete collection of fairy tales (1854-1866) suitable for children's reading. The tales included in it retained the peculiarities of local folk dialects, cruel details that could hurt a child's soul.

On the contrary, the children's edition was entirely adapted to the use of fairy tales as children's reading. Afanasiev skillfully selected the most suitable 89 out of 600 fairy tale texts.

Afanasiev skillfully selected the most suitable 89 out of 600 fairy tale texts.

Work on collecting fairy tales that exist among the people is carried out in our time. And it can never be considered complete, despite the fact that the folk narrator has long been replaced by a writer.

Classical examples of processing and retelling of Russian folk tales for children of preschool and primary school age were created in the 19th century. KD. Ushinsky, L.N. Tolstoy; in the 20th century — AN. Tolstoy, AN. Nechaev, M.A. Bulatov, I.V. Karnaukhova, A.P. Platonov. The list of writers-processors can be continued: A.M. Remizov, D.N. Mamin-Sibiryak, B.V. Shergin, P.P. Bazhov, O.I. Kapitsa, B.A. Privalov, M.M. Sergienko and others. Each of these processors has its own style, its own individual approaches to retelling.

The long-term practice of processing and retelling Russian folk tales dictates its own rules to writers, establishes its own laws.

Can a children's fairy tale completely repeat folklore records? Does the text need to be processed? How exactly should a folk tale be processed?

It is quite obvious that "childish", "childish" fairy tales, intended for the smallest children, almost do not need to be processed. They have come down to us in their original form. “Okay”, “Forty-white-sided”, “A horned goat is coming”, lullabies, nursery rhymes, persuasions, counting rhymes pass from generation to generation to children and almost do not change in form and content. The same can be said about folk tales that enter the life of a child from the age of two or three. “With amazing pedagogical tact, they absorb for children the range of ideas available to them. They take on a chain form when the same phrase is repeated repeatedly, but each time with a new addition or variation (“I left my grandmother, I left my grandfather, I left the hare ... I left my grandmother, I left my grandfather left, I left the hare, I left the wolf ... ”, etc.). It gives the child great pleasure that he knows in advance what will be said now. Try to miss something - a small listener will immediately stop you ”(Karnaukhova, 1966:10). Such tales can be published according to folklore records, explaining, perhaps, only incomprehensible words.

They have come down to us in their original form. “Okay”, “Forty-white-sided”, “A horned goat is coming”, lullabies, nursery rhymes, persuasions, counting rhymes pass from generation to generation to children and almost do not change in form and content. The same can be said about folk tales that enter the life of a child from the age of two or three. “With amazing pedagogical tact, they absorb for children the range of ideas available to them. They take on a chain form when the same phrase is repeated repeatedly, but each time with a new addition or variation (“I left my grandmother, I left my grandfather, I left the hare ... I left my grandmother, I left my grandfather left, I left the hare, I left the wolf ... ”, etc.). It gives the child great pleasure that he knows in advance what will be said now. Try to miss something - a small listener will immediately stop you ”(Karnaukhova, 1966:10). Such tales can be published according to folklore records, explaining, perhaps, only incomprehensible words.

The main layer of Russian folk tales (magical, satirical, everyday) is not intended for children. They are difficult (and should not) be read to children. There are experts who say that a folk tale should not be altered, it is only necessary to edit the record, remove rudeness, obscene words and scenes from it. According to the true folklorists, this is a profound delusion. Fairy tales “in their living folk life are not a work intended for children” (ibid.).

They were told (orally), as a rule, by men during short breaks and in the evenings during seasonal work. In authentic records, the text of fairy tales is transmitted in compliance with all dialect and linguistic features. They are not easy to read even for adults. But to remove dialectisms, excessive rudeness from a genuine recording, to “translate” it into a literary language - this is far from all that is required. We must not forget that the folk tale was born as an oral genre. When the text is written down from the mouth of a storyteller, there are many reticences, “empty” places in that text, which in a living story are filled with gestures, facial expressions, and intonation. The handler must “in a word convey to the reader what was shown to the viewer-listener by a gesture” (ibid.).

The handler must “in a word convey to the reader what was shown to the viewer-listener by a gesture” (ibid.).

But the most important thing is to reveal to the reader the truly folk meaning of the tale, its moral essence, its ideological content. For the educational role of a fairy tale in the formation of a child's worldview is incomparable with anything.

The handler starts by finding the plot it needs. Not every fairy tale can be given to children. Tales about clever thieves, evil cunning, which turns out to be undefeated and unexposed, etc., should not be introduced into the circle of children's reading.

Each plot in the collections of fairy tales has dozens of options. The handler can choose, in his opinion, the best one and work on it. It can take the best of several options and create its own, new one. Can, finally, tell a fairy tale in a completely new way. Tolstoy used eighteen of its variants. And while working on the fairy tale "Ivan the Cow's Son", I studied twenty-two options from different sources and only six of them involved in the creation of my own text. Each time, working on his version of the fairy tale, A.N. Tolstoy did a thorough preparatory work. He studied the material published in various collections (A.N. Afanasyev, D.N. Sadovnikov, D.K. Zelenin, N.E. Onchukov, A.N. Smirnov, M.K. Azadovsky and others .), as well as handwritten notes. He specially invited the storyteller M.M. Korguev. The text of the fairy tale "Andrey the Archer" written down after him, with the involvement of other records, is the basis of one of the best fairy tales processed by the writer - "Go there - I don't know where, bring it - I don't know what." Usually, the most expressive details from parallel variants were introduced into the base text. All fairy tales are retold by the writer in modern literary language. A.N. Tolstoy was the first to implement the technique of "pure retelling".

Each time, working on his version of the fairy tale, A.N. Tolstoy did a thorough preparatory work. He studied the material published in various collections (A.N. Afanasyev, D.N. Sadovnikov, D.K. Zelenin, N.E. Onchukov, A.N. Smirnov, M.K. Azadovsky and others .), as well as handwritten notes. He specially invited the storyteller M.M. Korguev. The text of the fairy tale "Andrey the Archer" written down after him, with the involvement of other records, is the basis of one of the best fairy tales processed by the writer - "Go there - I don't know where, bring it - I don't know what." Usually, the most expressive details from parallel variants were introduced into the base text. All fairy tales are retold by the writer in modern literary language. A.N. Tolstoy was the first to implement the technique of "pure retelling".

From a special creative position, A.P. approached work on folk tales. Platonov. In an effort to bring them closer to the perception of modern readers, the writer avoided archaic stylistic turns, boldly introduced the style of everyday story and psychological story, modern words and expressions into the narrative. He surprisingly subtly understood the possibilities of contact between folk tales and other genres. The plot of The Magic Ring is one of the most popular plots of Russian folk tales. More than twenty variants of it are known in the records. A.P. Platonov borrows small details from many sources and only conditionally adheres to the general storyline, telling a fairy tale “in a Platonic way”.

He surprisingly subtly understood the possibilities of contact between folk tales and other genres. The plot of The Magic Ring is one of the most popular plots of Russian folk tales. More than twenty variants of it are known in the records. A.P. Platonov borrows small details from many sources and only conditionally adheres to the general storyline, telling a fairy tale “in a Platonic way”.

In any case, the processor must know all the variants of truly folk tales, “love and feel” the fairy tale language, understand the meaning inherent in the tale, its morality and not sin against the typical, traditional folk image, endowing it with features unusual for folklore. Ivanushka or Ivan Tsarevich, for example, cannot be greedy and greedy. And in A.N. Tolstoy's "The Tale of the Gray Wolf" Ivan Tsarevich "looked at the golden cage." Such errors and inaccuracies are sometimes made even by venerable editorial writers.

Different opinions are expressed about the language of folk tales for children. “You can translate it into the plan of literary speech, as the classics did (Odoevsky “Moroz Ivanovich”, Ushinsky “The Blind Horse”, L. Tolstoy “Two Brothers”, etc.). It is possible to preserve the structure, syntax, musical intonation of the folk language, - wrote I.V. Karnaukhov. “But in order for the language of a fairy tale, cleansed of unnecessary archaisms, regional words and distortions, to sound like a truly folk language, it must be organic for the author, native and loved by him” [ibid.]. In terms of language, a folk tale is always "transparent, stingy, clear." This is how the processed text should be. Processors must remember that a genuine folk tale contains a philosophical generalization (idea, morality), and morality is not expressed openly, it follows from the content of the tale. The children's story is optimistic. It is realistic and at the same time fantastic and hyperbolic, because children “understand and remember not with reason and memory, but with imagination and fantasy” (Belinsky, 1983:378).

“You can translate it into the plan of literary speech, as the classics did (Odoevsky “Moroz Ivanovich”, Ushinsky “The Blind Horse”, L. Tolstoy “Two Brothers”, etc.). It is possible to preserve the structure, syntax, musical intonation of the folk language, - wrote I.V. Karnaukhov. “But in order for the language of a fairy tale, cleansed of unnecessary archaisms, regional words and distortions, to sound like a truly folk language, it must be organic for the author, native and loved by him” [ibid.]. In terms of language, a folk tale is always "transparent, stingy, clear." This is how the processed text should be. Processors must remember that a genuine folk tale contains a philosophical generalization (idea, morality), and morality is not expressed openly, it follows from the content of the tale. The children's story is optimistic. It is realistic and at the same time fantastic and hyperbolic, because children “understand and remember not with reason and memory, but with imagination and fantasy” (Belinsky, 1983:378).

But an allegory in a children's fairy tale is hardly appropriate. Abstraction is inaccessible to the mind of the child. She is alien to him. The indispensable requirements for a processed folk tale are an effective plot, a “tangled” plot (more and more obstacles arise in the way of the hero, and he must overcome them), an active hero.

Each writer has his own - individual, creative - manner of presentation. Therefore, it makes no sense to offer once and for all a given technological scheme for processing Russian folk tales.

The article deals only with the fundamental issues of adapting the text of a Russian folk tale to children's perception. All these requirements need to be known to editors and compilers of collections of fairy tales.

In the current conditions, publishers of children's books, striving for "fee-free" options, prefer to deal with classics, folklore, folk tales. Dozens of collections of fairy tales are published. The quality of compilation and editing of many of them leaves much to be desired. Editors of children's literature, compilers of collections need to know the fundamental issues discussed in the article of adapting the text of a Russian folk tale to children's perception.

Editors of children's literature, compilers of collections need to know the fundamental issues discussed in the article of adapting the text of a Russian folk tale to children's perception.

Notes

1 Belinsky V. G. A walk with children in St. Petersburg and its environs // V. G. Belinsky, N. G. Chernyshevsky, N. A. Dobrolyubov about children's literature. M., 1983. S. 52.

2 Afanasiev A.M. Folk Russian fairy tales: In 3 vols. M., 1957. S. 384-385.

3 Belinsky V. G. Full. coll. cit.: V 13 t. M., 1954. V. 5. S. 660.

4 Russian folk tales collected by B. Bronnitsyn. SPb., 1838. P. 111.

5 Ibid.

6 Afanasiev A. N. Folk Russian fairy tales. M., 1990. T. 3. S. 383.

7 Dal V. I. Full. coll. cit.: In 10 volumes. St. Petersburg: M. , 1898. T. 10. S. 550.

, 1898. T. 10. S. 550.

8 Cit. Quoted from: Starostin V. Ilya Muromets. Bogatyr epics. M., 1967. C. 157-158.

9 Dal V. I. The first child of a semi-literate grandson. Fairy tales, songs, games. M., 1871.S. 21.

10 Afanasiev A. N. Decree. op. P. 10.

11 Ibid. S. 11.

12 Ibid.

13 http://anthropology.ru/ra/texts/vinogr/mis18_17.html.

14 Afanasiev A.N. Decree. op.

15 Ibid. S. 114.

Bibliography

Anikin V.P. Writers and a folk tale // Russian fairy tale in the processing of writers. M., 1970.

Afanasiev A.M. Folk Russian fairy tales: In 3 vols. M., 1957.

Belinsky V.G. Full coll. cit.: In 13 t. M., 1954. T. 5.

V. G. Belinsky, N.G. Chernyshevsky, N.A. Dobrolyubov about children's literature. M., 1983.

G. Belinsky, N.G. Chernyshevsky, N.A. Dobrolyubov about children's literature. M., 1983.

Georgian A. E. A. N. Afanasiev (Biographical sketch): Sat. articles. M.: Children's literature, 1987.

Dal V.I. The first child of a semi-literate grandson. M., 1871.

Dal V.I. Full coll. cit.: In 10 t. St. Petersburg; M., 1898. T. 10.

Karnaukhova I. V. Russian heroes: epics and heroic tales in retelling for children. M., 2008.

Karnaukhova I.V. The main thing is to reveal the meaning // Children's literature. 1966. No. 7.

Folk Russian fairy tales. From Sat. A. N. Afanasiev / entry. Art. and a dictionary of obscure and regional words by V. P. Anikin. M., 1990.

Problems of children's literature and folklore. Collection of scientific papers. Petrozavodsk, 1999.

Russian children's tales collected by A. N. Afanasiev / scientific. ed. text, foreword and note. V. P. Anikina. M., 1987.

Russian folk poetry / ed.