Teaching sight words in first grade

Sight Words Teaching Strategy | Sight Words: Teach Your Child to Read

A child sees the word on the flash card and says the word while underlining it with her finger.

The child says the word and spells out the letters, then reads the word again.

The child says the word and then spells out the letters while tapping them on her arm.

A child says the word, then writes the letters in the air in front of the flash card.

A child writes the letters on a table, first looking at and then not looking at the flash card.

Correct a child’s mistake by clearly stating and reinforcing the right word several times.

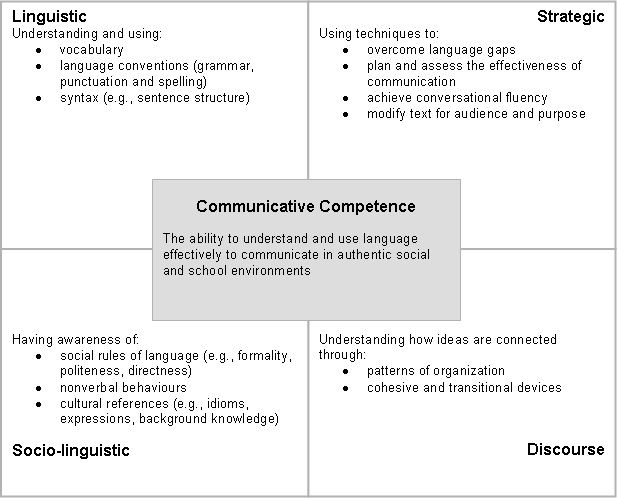

- Overview

- Plan a Lesson

- Teaching Techniques

- Correcting Mistakes

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Questions and Answers

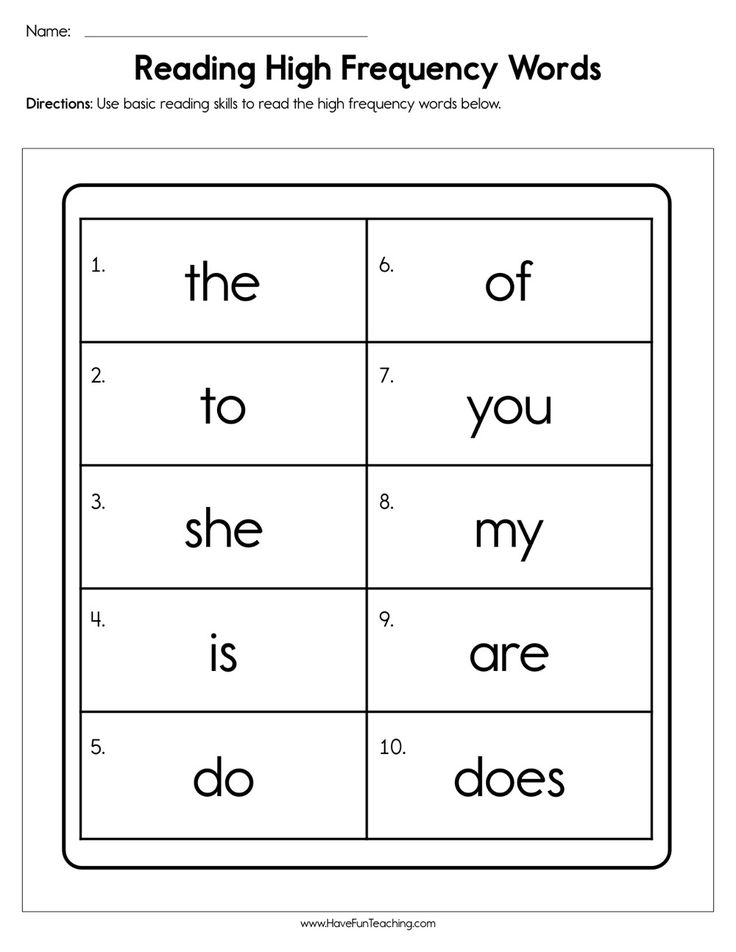

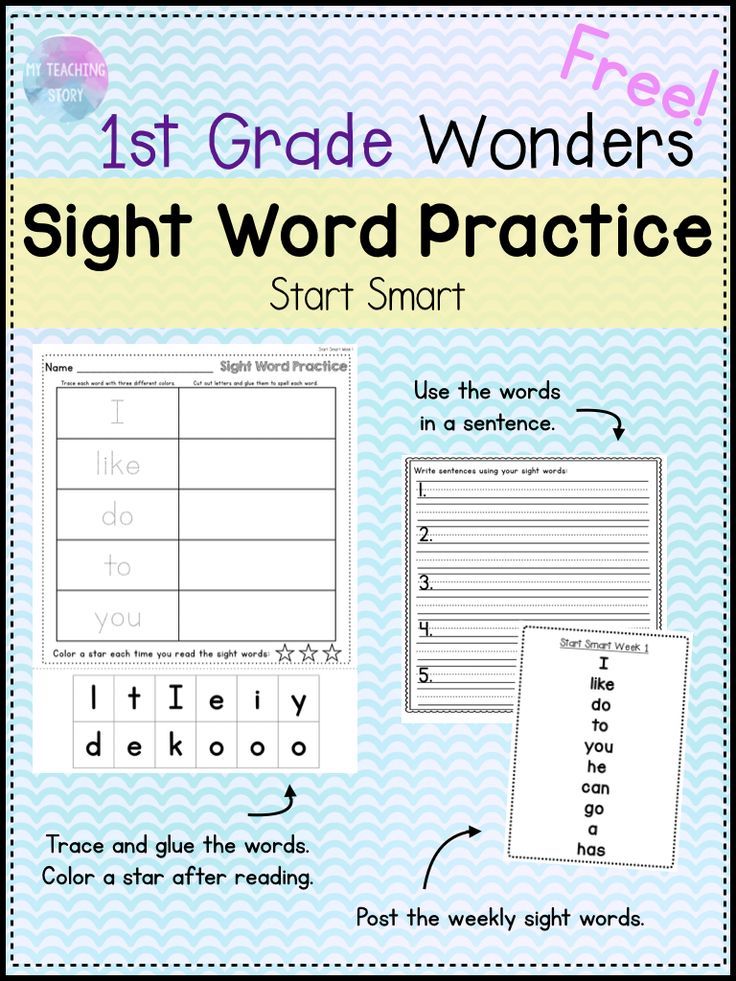

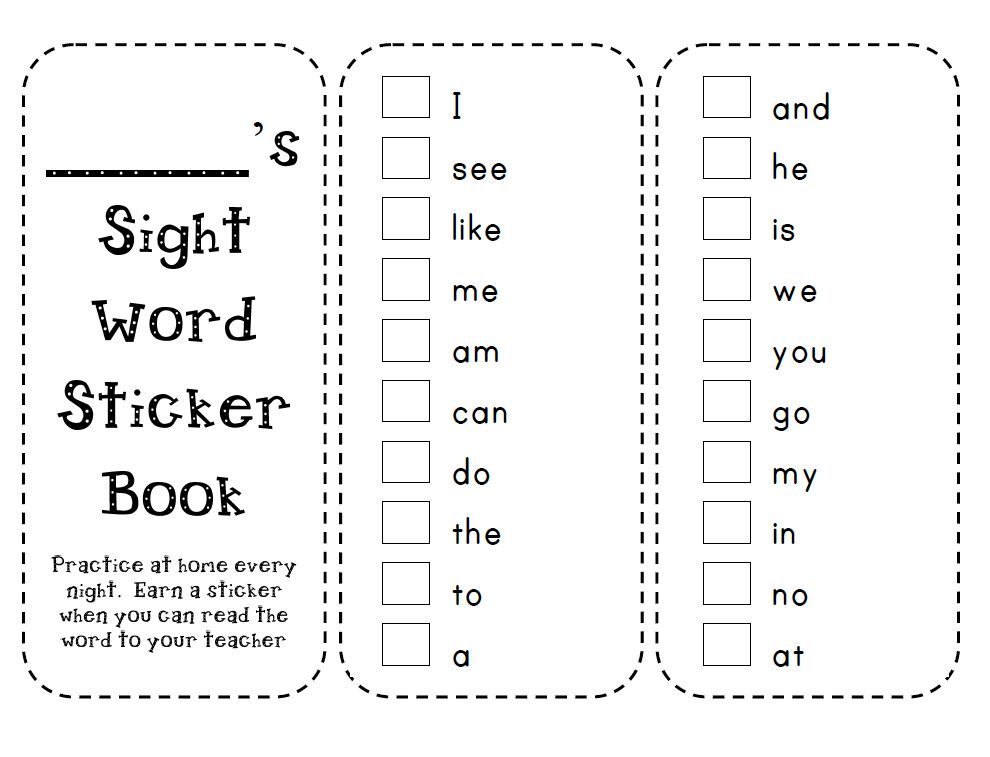

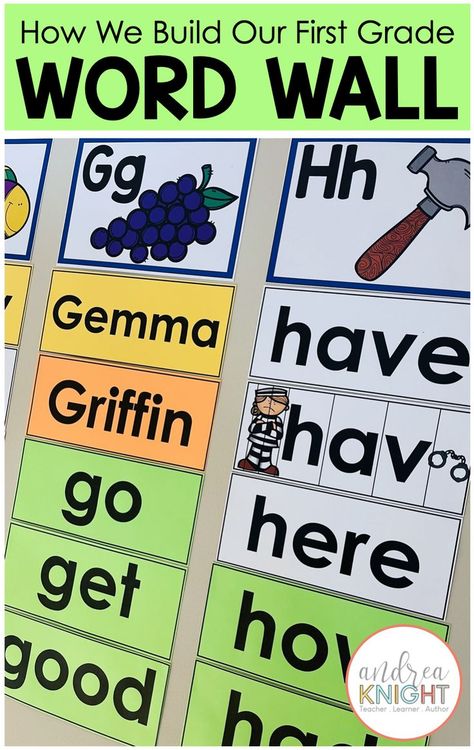

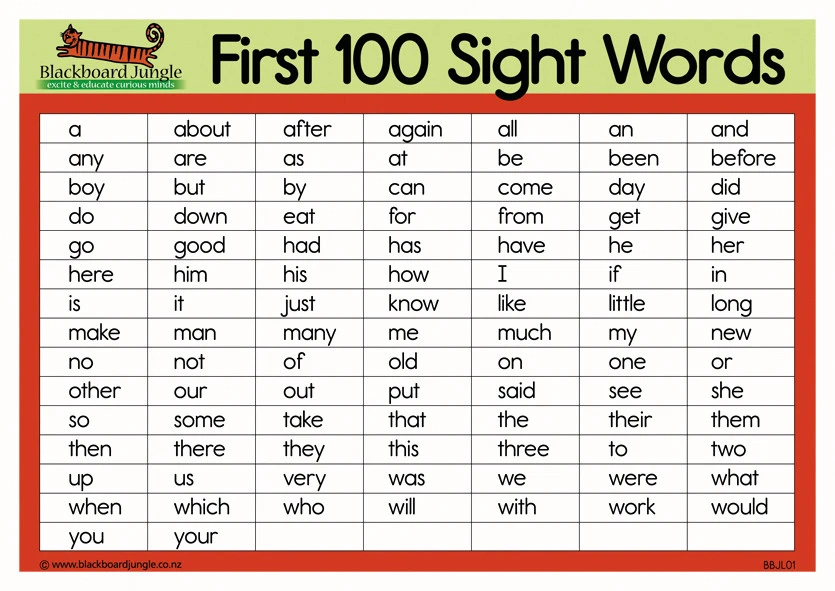

Sight words instruction is an excellent supplement to phonics instruction. Phonics is a method for learning to read in general, while sight words instruction increases a child’s familiarity with the high frequency words he will encounter most often.

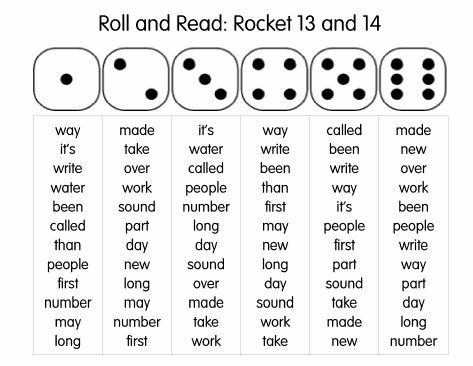

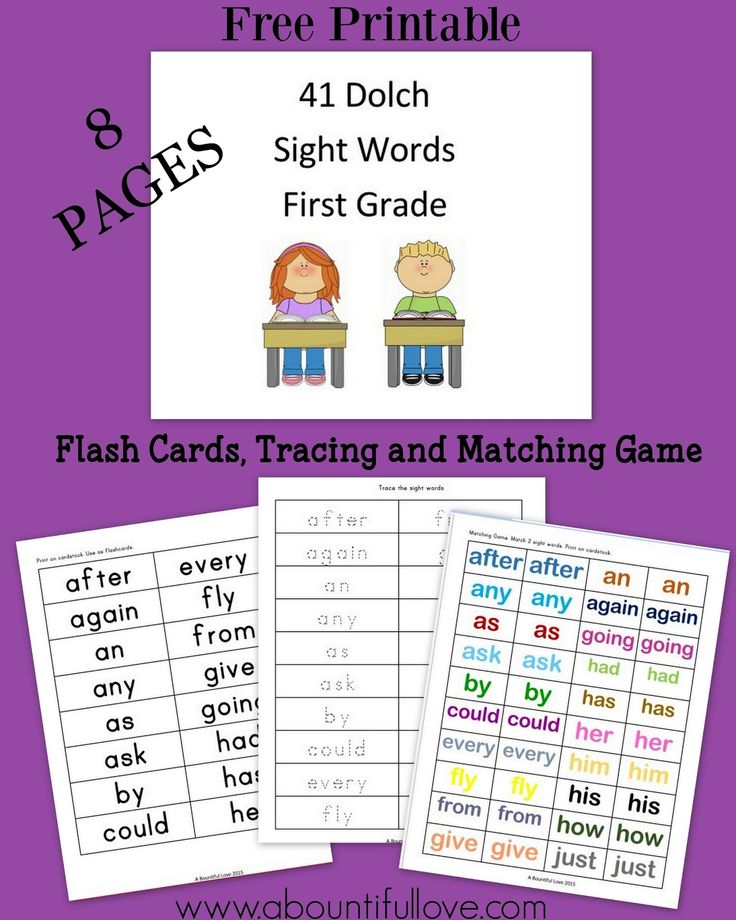

Use lesson time to introduce up to three new words, and use game time to practice the new words.

A sight words instruction session should be about 30 minutes long, divided into two components:

- Sight Words Lesson — Use our Teaching Techniques to introduce new words and to review words from previous lessons — 10 minutes

- Sight Words Games — Use our games to provide reinforcement of the lesson and some review of already mastered sight words to help your child develop speed and fluency — 20 minutes

Video: Introduction to Teaching Sight Words

↑ Top

2.

1 Introduce New Words

1 Introduce New Words

When first beginning sight words, work on no more than three unfamiliar words at a time to make it manageable for your child. Introduce one word at a time, using the five teaching techniques. Hold up the flash card for the first word, and go through all five techniques, in order. Then introduce the second word, and go through all five teaching techniques, and so on.

This lesson should establish basic familiarity with the new words. This part of a sight words session should be brisk and last no more than ten minutes. As your child gets more advanced, you might increase the number of words you work on in each lesson.

2.2 Review Old Words

Begin each subsequent lesson by reviewing words from the previous lesson. Words often need to be covered a few times for the child to fully internalize them. Remember: solid knowledge of a few words is better than weak knowledge of a lot of words!

Go through the See & Say exercise for each of the review words. If your child struggles to recognize a word, cover that word again in the main lesson, going through all five teaching techniques. If he has trouble with more than two of the review words, then set aside the new words you were planning to introduce and devote that day’s lesson to review.

If your child struggles to recognize a word, cover that word again in the main lesson, going through all five teaching techniques. If he has trouble with more than two of the review words, then set aside the new words you were planning to introduce and devote that day’s lesson to review.

Note: The child should have a good grasp of — but does not need to have completely mastered — a word before it gets replaced in your lesson plan. Use your game time to provide lots of repetition for these words until the child has thoroughly mastered them.

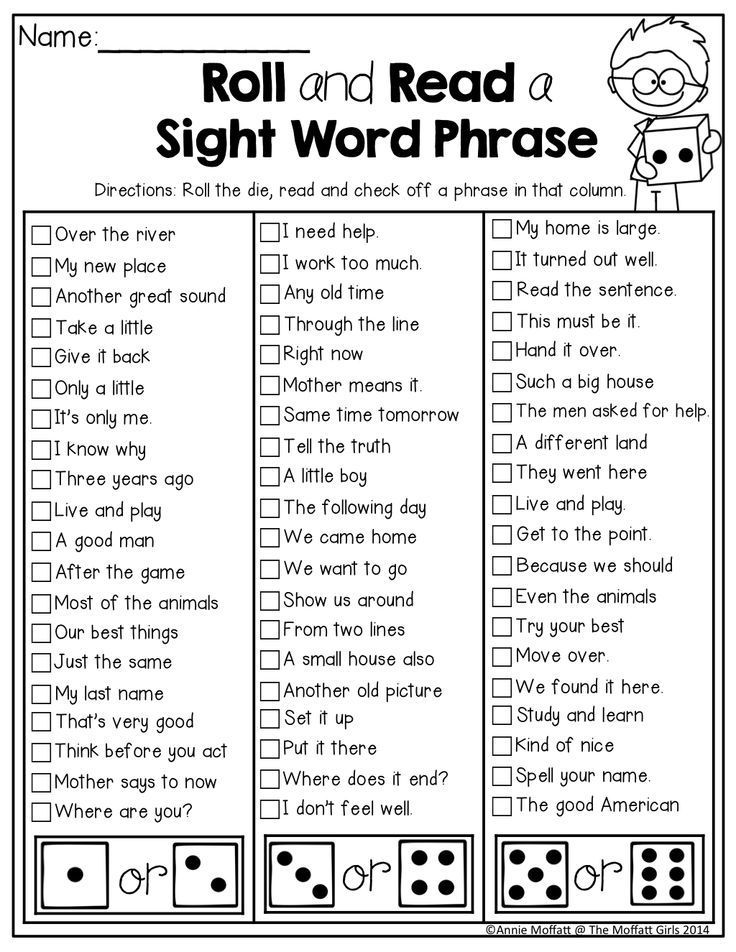

2.3 Reinforce with Games

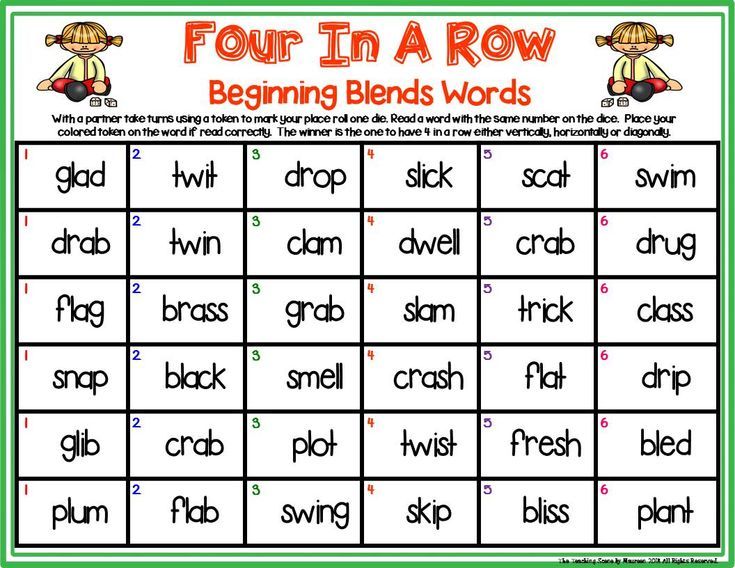

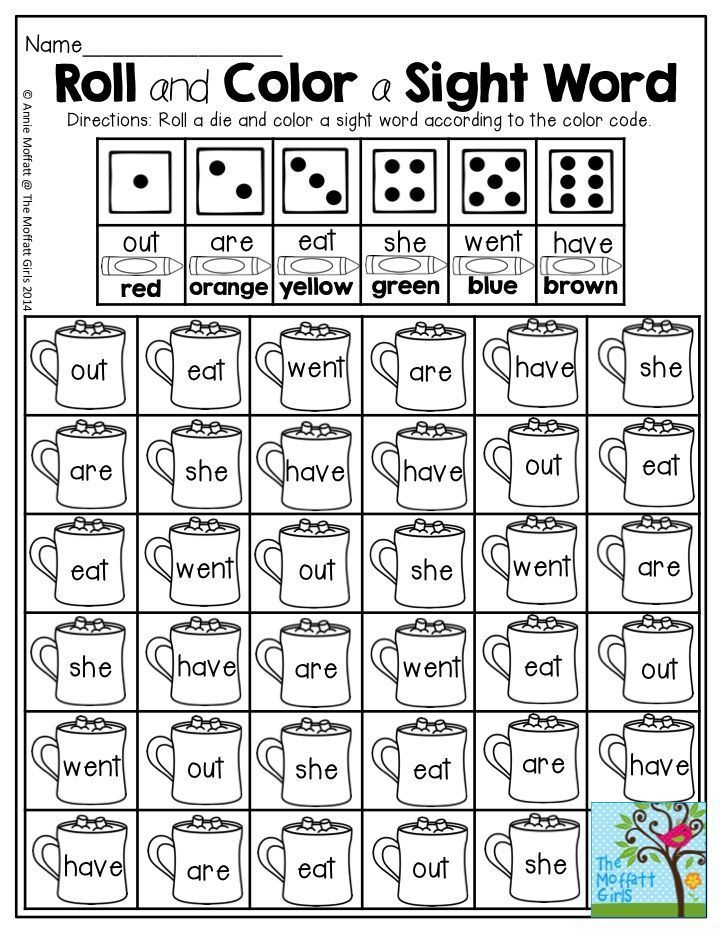

Learning sight words takes lots of repetition. We have numerous sight words games that will make that repetition fun and entertaining for you and your child.

The games are of course the most entertaining part of the sight words program, but they need to wait until after the first part of the sight words lesson.

Games reinforce what the lesson teaches.

Do not use games to introduce new words.

NOTE: Be sure the child has a pretty good grasp of a sight word before using it in a game, especially if you are working with a group of children. You do not want one child to be regularly embarrassed in front of his classmates when he struggles with words the others have already mastered!

↑ Top

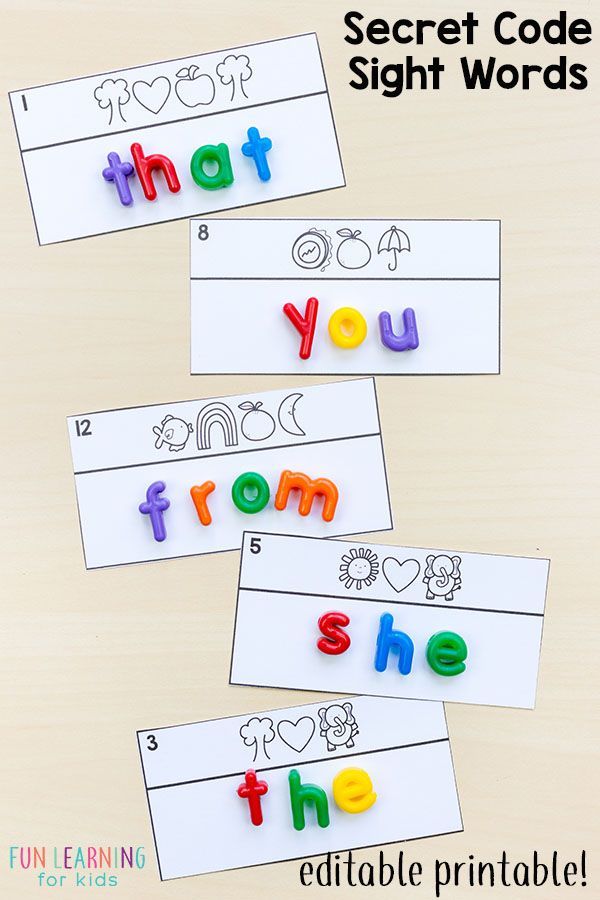

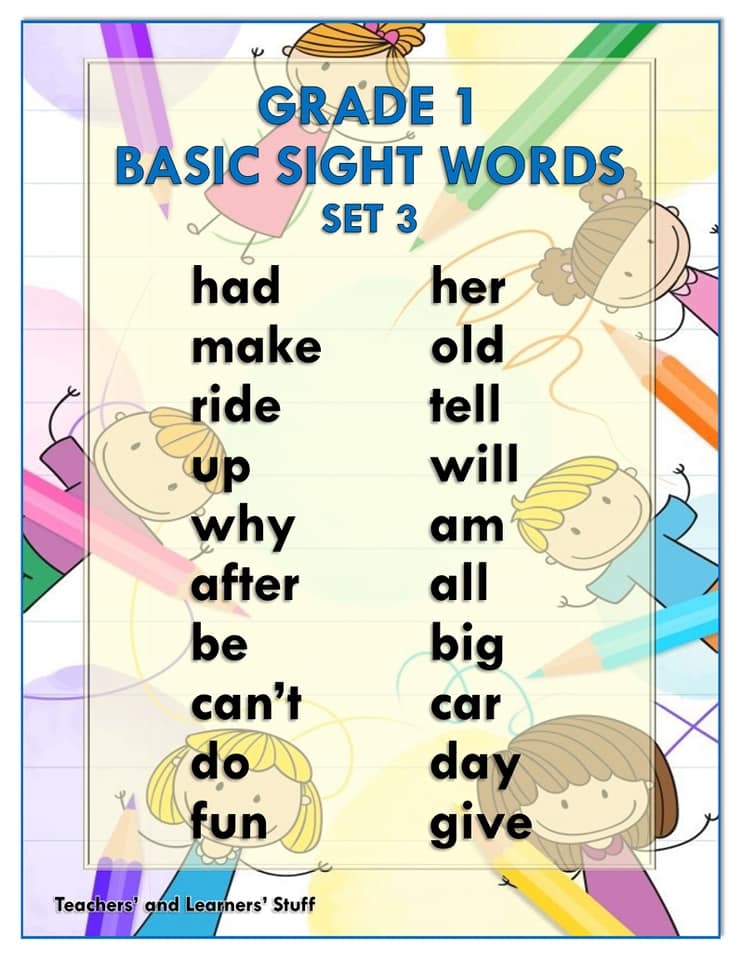

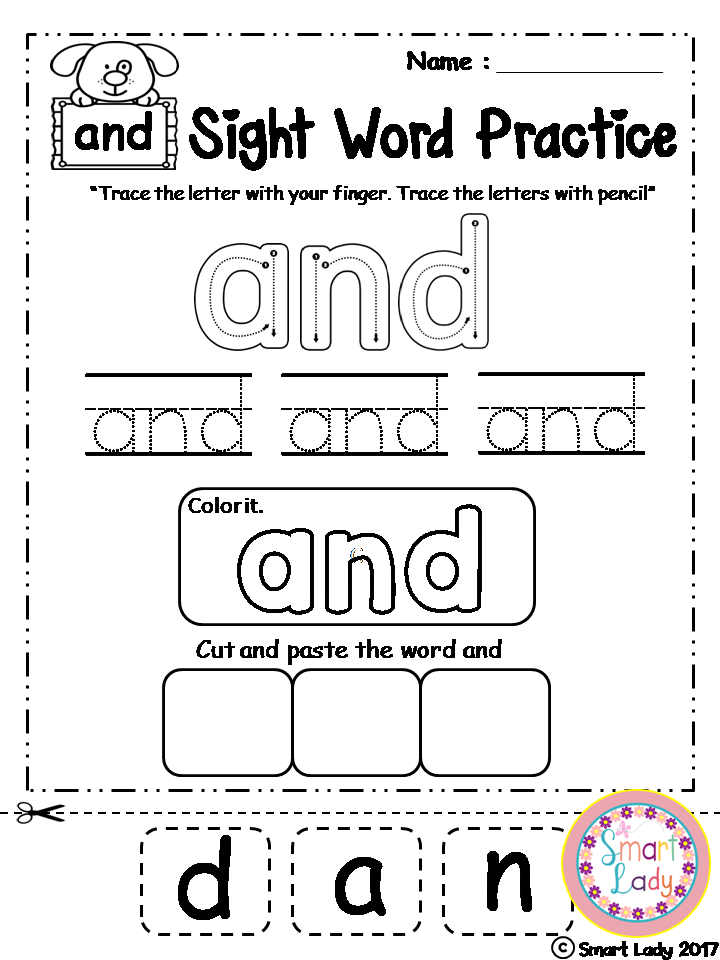

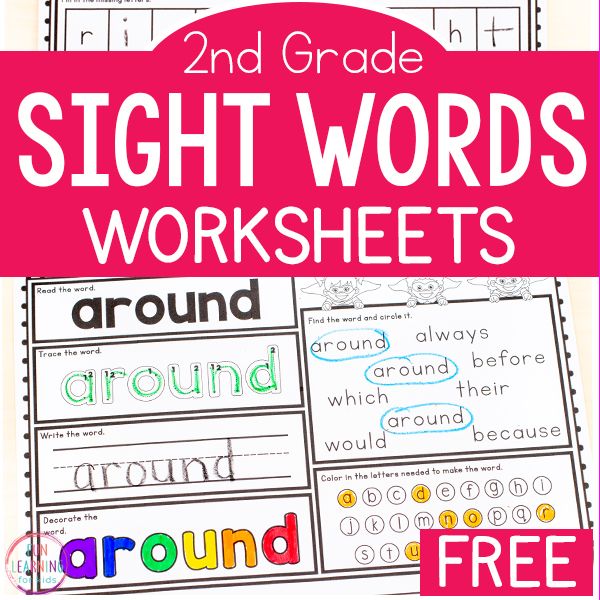

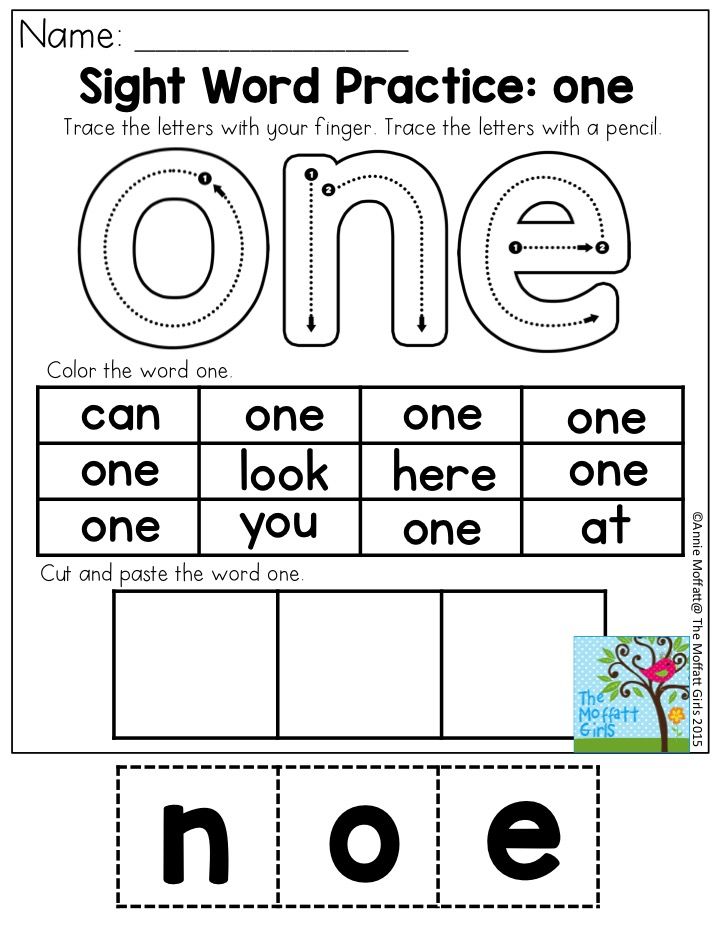

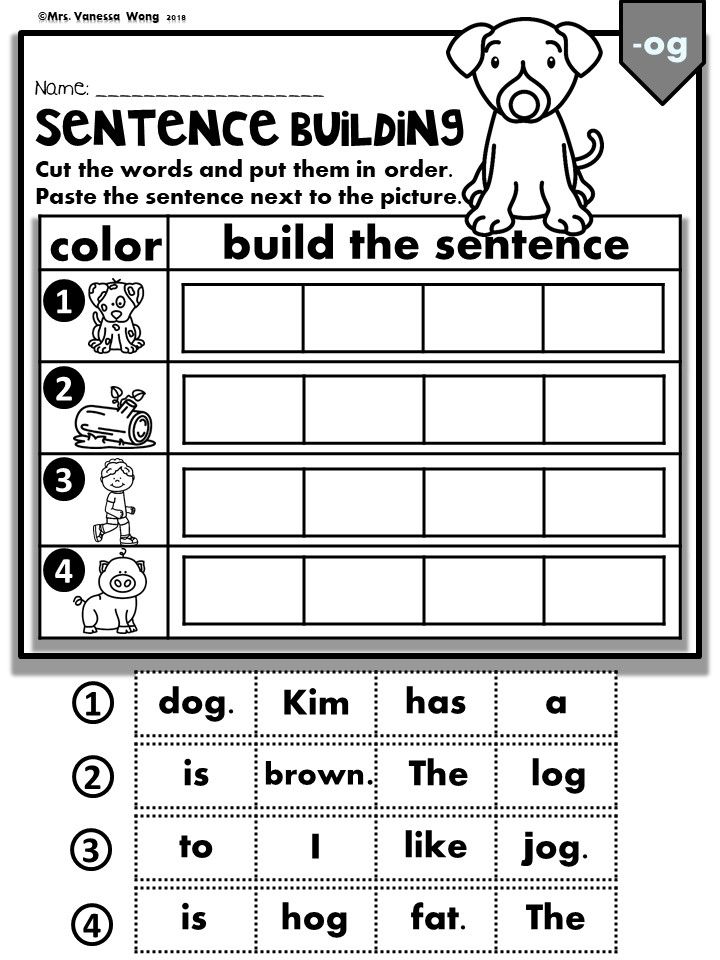

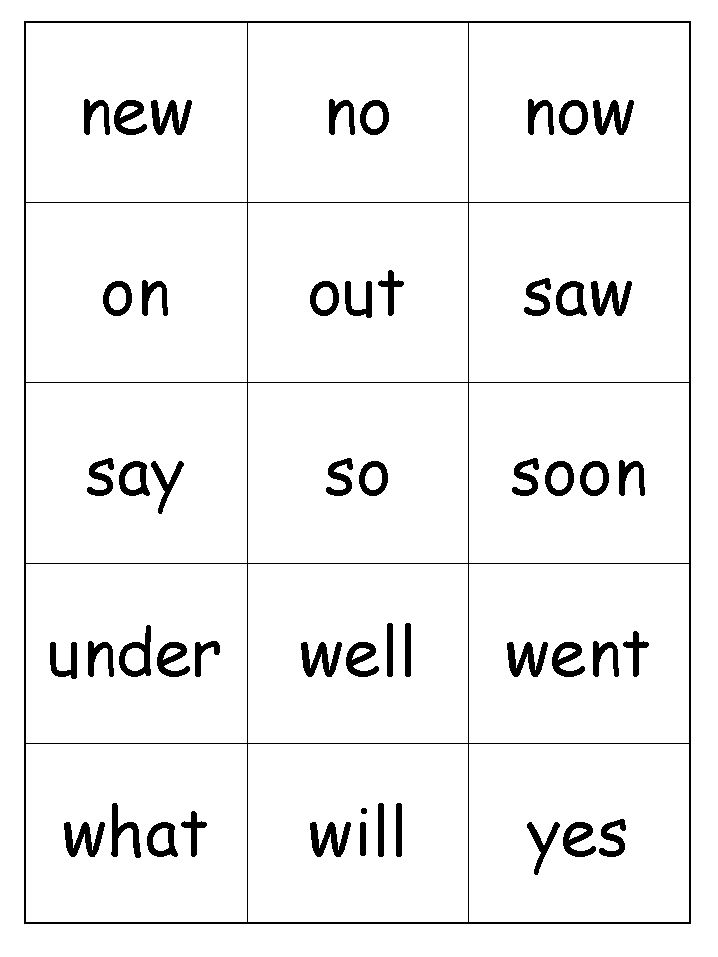

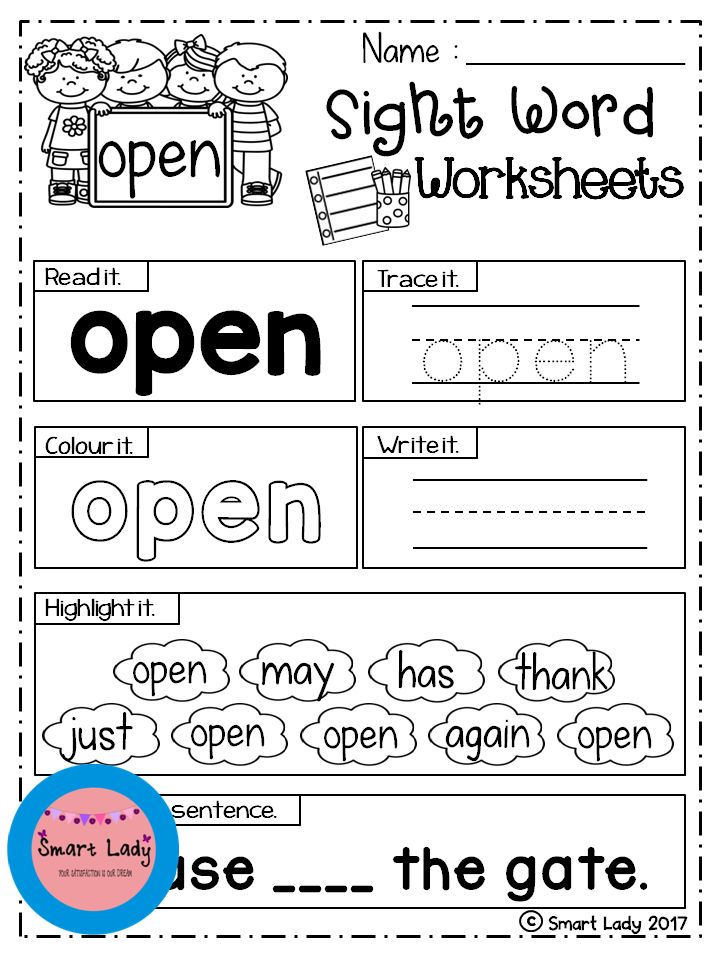

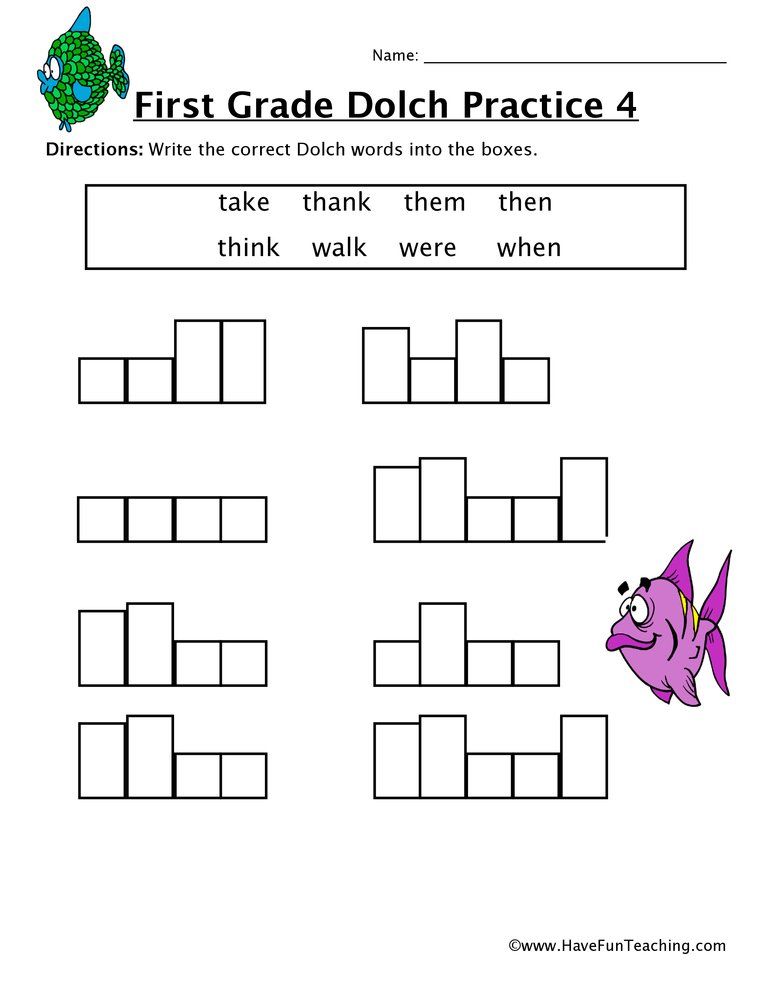

Introduce new sight words using this sequence of five teaching techniques:

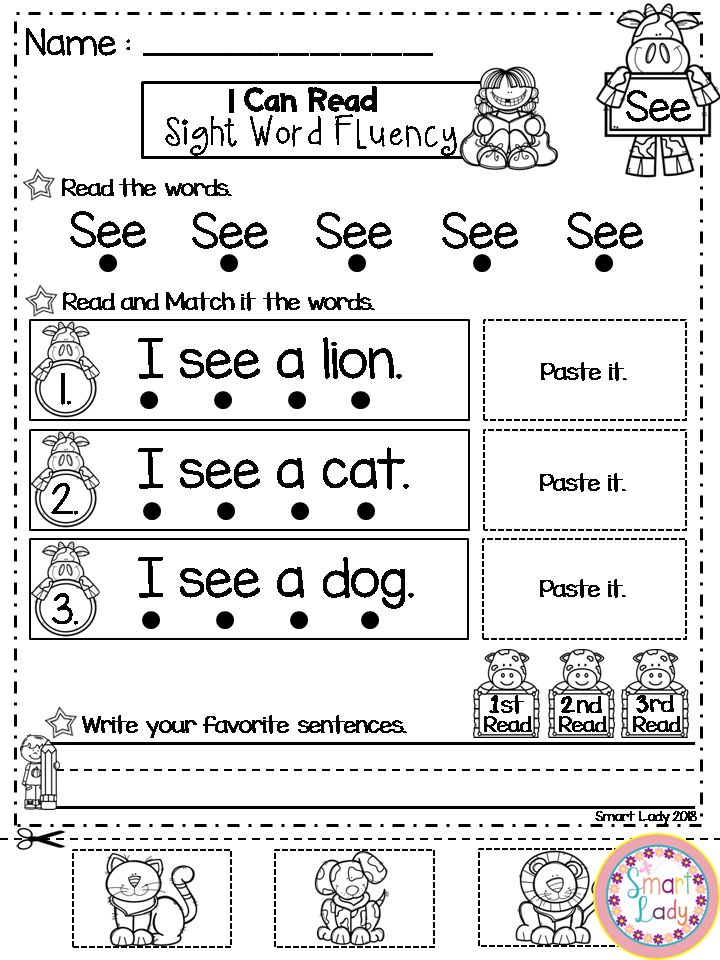

- See & Say — A child sees the word on the flash card and says the word while underlining it with her finger.

- Spell Reading — The child says the word and spells out the letters, then reads the word again.

- Arm Tapping — The child says the word and then spells out the letters while tapping them on his arm, then reads the word again.

- Air Writing — A child says the word, then writes the letters in the air in front of the flash card.

- Table Writing — A child writes the letters on a table, first looking at and then not looking at the flash card.

These techniques work together to activate different parts of the brain. The exercises combine many repetitions of the word (seeing, hearing, speaking, spelling, and writing) with physical movements that focus the child’s attention and cement each word into the child’s long-term memory.

The lessons get the child up to a baseline level of competence that is then reinforced by the games, which take them up to the level of mastery. All you need is a flash card for each of the sight words you are covering in the lesson.

↑ Top

Of course, every child will make mistakes in the process of learning sight words. They might get confused between similar-looking words or struggle to remember phonetically irregular words.

Use our Corrections Procedure every time your child makes a mistake in a sight words lesson or game. Simple and straightforward, it focuses on reinforcing the correct identification and pronunciation of the word. It can be done quickly without disrupting the flow of the activity.

Simple and straightforward, it focuses on reinforcing the correct identification and pronunciation of the word. It can be done quickly without disrupting the flow of the activity.

Do not scold the child for making a mistake or even repeat the incorrect word. Just reinforce the correct word using our script, and then move on.

↑ Top

Q: Progress is slow. We have been on the same five words for a week!

A: It is not unusual to have to repeat the same set of words several times, especially in the first weeks of sight words instruction. The child is learning how to learn the words and is developing pattern recognition approaches that will speed his progress. Give him time to grow confident with his current set of words, and avoid overwhelming the child with new words when he hasn’t yet become familiar with the old words.

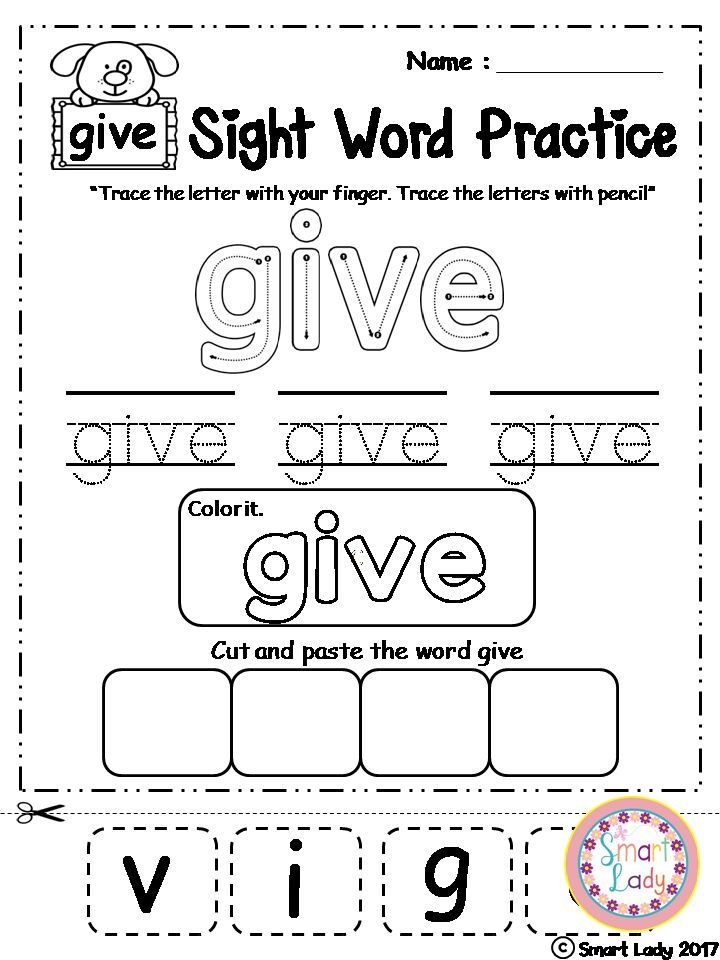

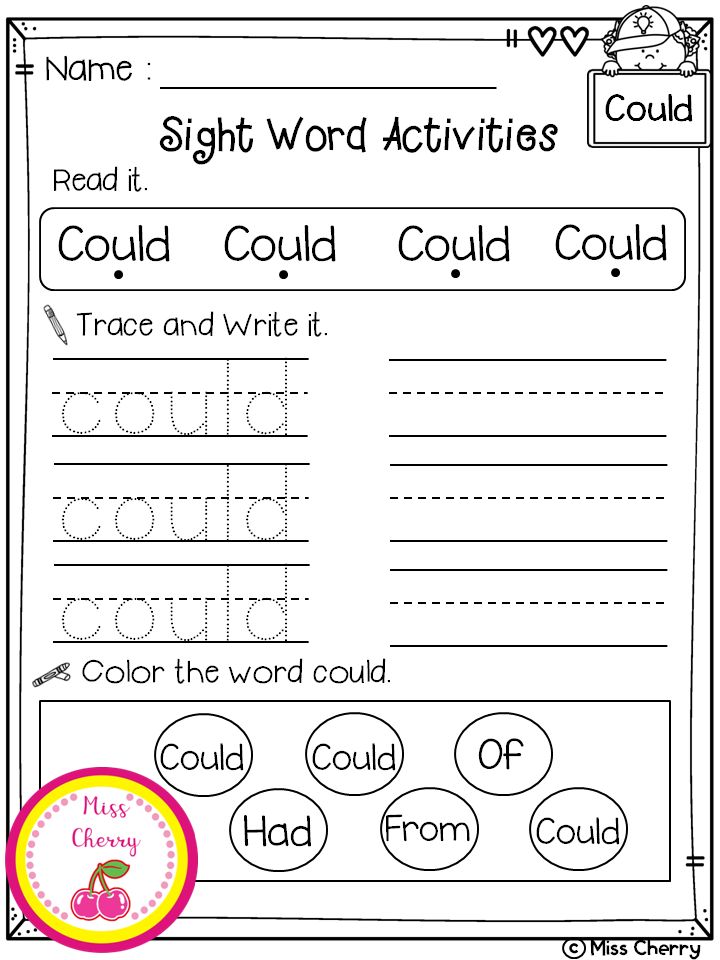

Q: Do I really need to do all five techniques for every word?

A: Start out by using all five techniques with each new word. The techniques use different teaching methods and physical senses to support and reinforce the child’s memorization of the word. After a few weeks of lessons, you will have a sense for how long it takes your child to learn new words and whether all five exercises are necessary. Start by eliminating the last activity, Table Writing, but be sure to review those words at the next lesson to see if the child actually retained them without that last exercise. If the child learns fine without Table Writing, then you can try leaving out the fourth technique, Air Writing. Children who learn quickly may only need to use two or three of the techniques.

The techniques use different teaching methods and physical senses to support and reinforce the child’s memorization of the word. After a few weeks of lessons, you will have a sense for how long it takes your child to learn new words and whether all five exercises are necessary. Start by eliminating the last activity, Table Writing, but be sure to review those words at the next lesson to see if the child actually retained them without that last exercise. If the child learns fine without Table Writing, then you can try leaving out the fourth technique, Air Writing. Children who learn quickly may only need to use two or three of the techniques.

Q: How long will it take to get through a whole word list? I want my child to learn ALL the words!!!

A: That depends on a number of factors, including frequency of your lessons as well as your child’s ability to focus. But do not get obsessed with the idea of racing through the word lists to the finish line. It is much, much better for your child to solidly know just 50 words than to “kind of” know 300 words. We are building a foundation here, and we want that foundation to be made of rock, not sand!

It is much, much better for your child to solidly know just 50 words than to “kind of” know 300 words. We are building a foundation here, and we want that foundation to be made of rock, not sand!

↑ Top

Leave a Reply

Corrections Procedure: Correcting Sight Word Mistakes

- Introduction

- Procedure

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Questions and Answers

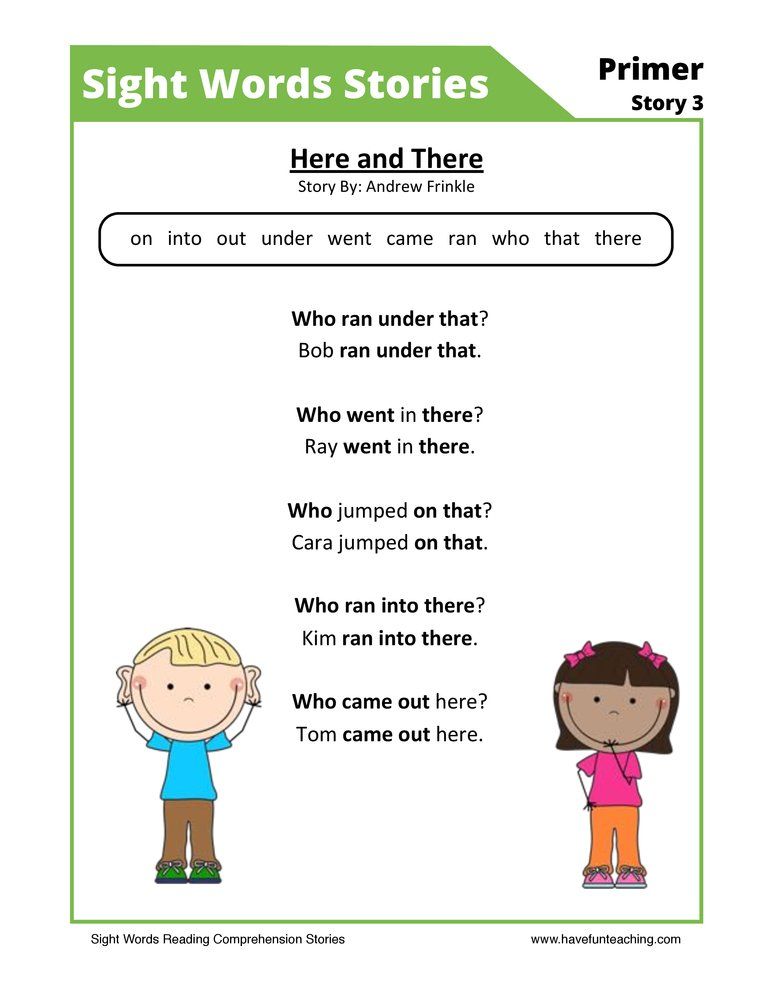

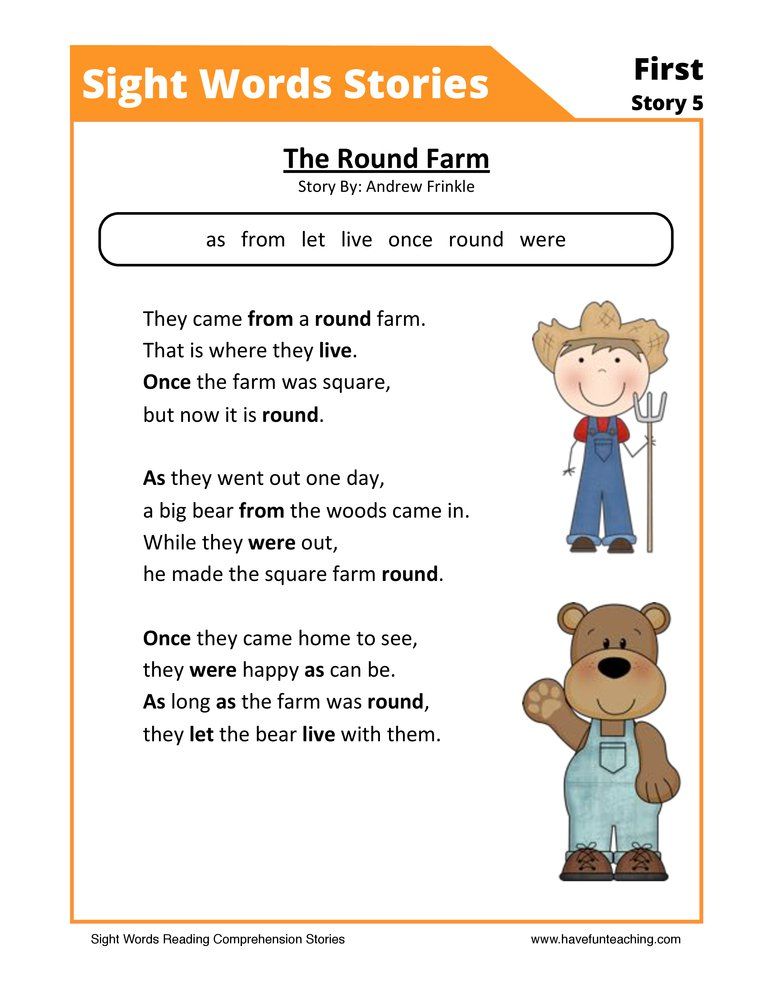

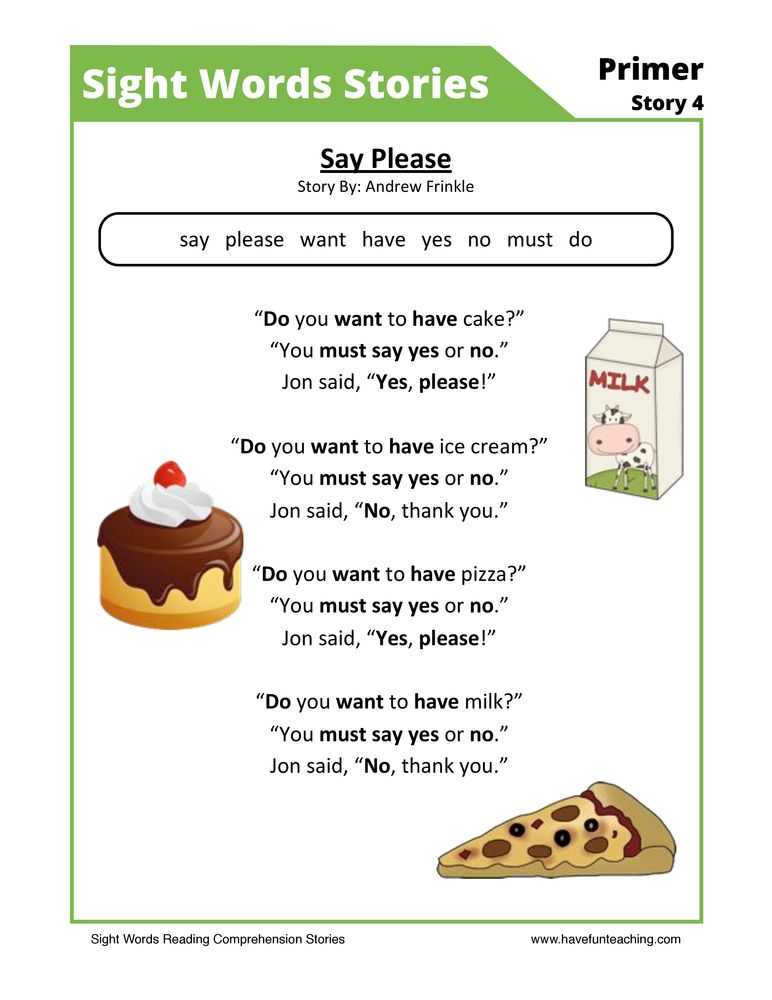

As children learn the sight words vocabulary and play our sight words games, they inevitably make mistakes where they provide a wrong answer or are unable to sight read the word. The corrections procedure provides feedback, to let the child know their answer was incorrect, and practice opportunities for learning the new word.

The corrections procedure takes just 20 seconds, and gives the opportunity for 6 repetitions of the correct word.

The purpose of this corrections procedure is to help the child learn the word. Focusing on the negative, shaming, discouraging, or punishing the child is counterproductive, as it only draws the child’s attention away from the task at hand. Rather, we want to place the emphasis on the child’s correctly learning the target word that is causing difficulty.

↑ Top

We use the sight words corrections procedure when the child incorrectly reads a word or takes more than five seconds to read a word. The corrections procedure takes just 20 seconds and gives the opportunity for 6 repetitions of the correct word:

Video: Sight Words Corrections Procedure

For example, if the mistaken target sight word is should, then we would respond as follows. Each time the child says the word, the adult should rapidly move their finger underneath the word on the card, from left to right. During the correction, we move our finger under the printed word, to draw the child’s attention to the word and to cement the connection between the written and spoken word. We also use the word in a sentence to help the child understand the meaning of the word.

Each time the child says the word, the adult should rapidly move their finger underneath the word on the card, from left to right. During the correction, we move our finger under the printed word, to draw the child’s attention to the word and to cement the connection between the written and spoken word. We also use the word in a sentence to help the child understand the meaning of the word.

Adult: That word is SHOULD. What word?

Child: SHOULD.

Adult: Again. What word?

Child: SHOULD.

Adult: Yes, SHOULD!

We SHOULD brush our teeth before bed.

What word?

Child: SHOULD.

Following the correction, we continue on with the lesson or game. The procedure should be done at a brisk pace and should only take around 20 seconds, allowing you to stay in the flow of the sight words activity. Do not skip over the correction procedure! In fact, print out this PDF of the correction script and keep it with you as a handy reference whenever you are doing a sight words activity.

Notice how the entire focus of the correction was on teaching the child the correct word. We don’t focus attention on the incorrect word, which wastes time and simply reinforces the wrong answer. While it is clear to the child that the original answer provided was not the right answer, the focus is completely on helping them to learn the correct answer. The corrections procedure is positive for the child and the teacher.

Do not detour into a phonics lesson, by sounding out the word. Sight words need to be instantly recognized, not decoded. These words are the ones used most frequently in written English, and many of them do not follow the general spelling and pronunciation rules of phonics. The child should therefore learn to recognize and read the sight words purely by sight.

↑ Top

Q: A child is making silly mistakes. They are getting the answers to questions they know wrong or they are deliberately getting answers wrong. What should I do?

What should I do?

If this behavior persists, escalate your response by saying that if they keep being silly you will stop the lesson. If this warning is ignored, follow through on this consequence. We find it counterproductive to reprimand the child; simply tell them that you stopped the lesson because they are being silly and that they can have another lesson tomorrow.

Particularly when you are working with young children, be prepared for bursts of silliness or days when they simply don’t feel like working. Try to work through this, but it is better to cut short a session than turn it into a battle of wills.

↑ Top

Leave a Reply

Open Education: Schools and Kindergartens for Visually Impaired Children / Un Certain Regard

Listen to Publication Typhlocommentary: Bright sunlight floods an empty classroom: blackboard, desks and chairs.

Choosing an educational institution for a blind or visually impaired child is a responsible task that requires a conscious approach. Along with studying in specialized institutions, visually impaired students have the opportunity to follow the path of inclusive education - to study with children who see differently in ordinary kindergartens and general education schools. Read our article about what education options are available for blind and visually impaired children in Russia. nine0004

Tiflocommentary: a girl of about six is sitting on her knees in front of a round table and dipping a brush into the paint with her left hand. She has long dark hair, a striped black and white dress, a white blouse and white socks. Glasses on the eyes. The girl smiles widely. In the background, with their backs to her, two boys in multi-colored T-shirts are sitting in front of easels and drawing. The room is bright and filled with toys.

Preschool education

There are specialized kindergartens for preschool children with visual impairments, as well as kindergartens of compensatory and combined types. nine0004

nine0004

Compensatory kindergartens train children who, for various reasons, experience difficulties in mastering general education programs. There are groups for children with hearing impairment, diseases of the musculoskeletal system, speech disorders, psychological illnesses: increased excitability, irritability, nervousness, as well as children with visual impairment. In such kindergartens, the most comfortable conditions for teaching children with special needs have been created: speech therapists, psychologists, massage therapists, therapists, physical therapy trainers and other specialists work there. nine0004

Combined Kindergartens are an opportunity for children with visual impairments to study alongside children without disabilities, while receiving sufficient attention from teachers. In such kindergartens, along with general education groups, groups with a special specialization have been created, for example, compensating for children with visual impairments.

In specialized kindergartens, children are taught according to a special correctional program. In addition, typhlopsychologists, speech therapists and typhlopedagogues work with children. There are also classes for visually impaired children on the devices. nine0004

In addition, typhlopsychologists, speech therapists and typhlopedagogues work with children. There are also classes for visually impaired children on the devices. nine0004

Tiflocommentary: in the photograph, flooded with sunlight, a girl walks with her back to us, holding the hand of a woman in a striped T-shirt and jeans. The girl has blond hair, put in a high ponytail and braided in a pigtail. She wears a turquoise T-shirt and a blue backpack. Glasses on the eyes. She smiles mischievously as she turns to the woman.

Schools

As for schools, visually impaired children also have the opportunity to study in special institutions: boarding schools and correctional schools of III-IV type - and inclusive: Waldorf and schools of integrated education. nine0004

“In different cities of Russia there are boarding schools and correctional schools for blind and visually impaired children: in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Ryazan, Nizhny Novgorod, Vladimir and others. As a rule, the visually impaired and the totally blind study in different educational institutions: separate boarding schools for the visually impaired and separate boarding schools for the blind. This is more productive, since the teaching methods are different,” says Victoria Polukarova, a social work specialist at boarding school No. 1 for the education and rehabilitation of the blind. nine0004

This is more productive, since the teaching methods are different,” says Victoria Polukarova, a social work specialist at boarding school No. 1 for the education and rehabilitation of the blind. nine0004

For example, in correctional schools of the III-IV type, special forms and methods of work, original textbooks and manuals, typhlotechnics are used in the organization of the educational process: the educational program is changed here in accordance with the needs of students, and fewer children study in classes than in general education schools. A big plus is that in such educational institutions they are attentive to the creation of appropriate sanitary and hygienic conditions for teaching blind and visually impaired children. In addition, teachers comprehensively prepare students for life in society. In specialized schools, as well as boarding schools, education lasts 12 years, as in elementary school, children spend five classes because of the study of Braille. nine0004

There is also an option for visually impaired and blind children to receive education at home: in this case, the children can study according to an individual program, observing a learning rhythm that is comfortable for them.

“Children with different causes of blindness study at our school. Late blind children came to our school, including those in the senior classes. In this case, they needed additional Braille lessons, as well as help in learning to navigate in space. But in most cases, the children were able to adapt and continue their education, - says Victoria Polukarova. - Also, it is recommended to go to a school where Braille is taught to children who are visually impaired, but with a poor prognosis for vision, since with such training there is no strain on the eyes. If the child is visually impaired, but with a good residual vision, then education in a boarding school for the visually impaired will be more productive.” nine0004

Tiflocommentary: A blond-haired boy of about four wearing glasses, a white T-shirt, burgundy jeans, and with a blue briefcase behind his shoulders, raises his right thumb up and smiles.

According to Candidate of Psychological Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Theory and Methods of Adaptive Physical Education, Novosibirsk State University. P.F. Lesgaft and Ksenia Nikolaeva, an employee of the Charitable Foundation for the Support of the Deaf and Blind “Connection” Ksenia Nikolaeva, are now opening district leisure and social rehabilitation centers for children with special needs, including those with visual impairments, in almost every city. “In them, parents and children can get expert advice and sign up for developmental classes. We should not forget about inclusive educational institutions, which cover an increasing number of regions,” she adds. nine0004

P.F. Lesgaft and Ksenia Nikolaeva, an employee of the Charitable Foundation for the Support of the Deaf and Blind “Connection” Ksenia Nikolaeva, are now opening district leisure and social rehabilitation centers for children with special needs, including those with visual impairments, in almost every city. “In them, parents and children can get expert advice and sign up for developmental classes. We should not forget about inclusive educational institutions, which cover an increasing number of regions,” she adds. nine0004

Inclusive education is the case when children, regardless of the presence or absence of developmental disabilities, learn together. Thus, the child is socialized and receives the skills of an independent life in society.

In addition to general education institutions with inclusive classes, there are also Waldorf schools. They differ in that the emphasis here is not on the development of academic knowledge, but on the creative abilities of the child. Students in such schools are not graded, so, according to teachers, children do not have a competitive spirit, and there is no division into leaders and laggards in the classes - all children feel like a single team. nine0004

nine0004

Audio comment: A young woman in a white blouse and glasses and a girl in a pink T-shirt are sitting at a table. A woman guides her child's hands over a book printed in Braille. The girl has her eyes closed.

According to Victoria Polukarova, despite the development of inclusive education in Russia, it is not quite suitable for students with visual impairments. “Methods of teaching a blind child (verbal method, the use of tactile and tactile sensations, the “hand in hand” method, etc.) require constant interaction between the teacher and the student, as well as spending more time explaining new material. In inclusive classes, compliance with these conditions is difficult, including due to the greater class size. At a minimum, a tutor is needed for every child with vision problems, which is not always possible. The different pace of work, primarily due to the use of Braille, complicates the quality implementation of the full lesson plan. We believe that in the case of blind children, inclusion is good in the second half of the day: extracurricular activities, additional education, competitions, festivals - when children with disabilities can freely interact with healthy children, socialize and adapt in society without compromising their educational activities,” she explains. nine0004

nine0004

Ksenia Nikolaeva also believes that inclusive classes are not suitable for every child. “It is not enough to open an inclusive class or group - it is important that a specialist with the necessary knowledge, skills and abilities in the field of special pedagogy and psychology work in it. Society must be ready to accept this system not only on paper, but also in real life, with its concrete examples. Everything in life must be approached without excesses, holding on to the golden mean and sound reasoning. I am of the opinion that not every family where a child with special needs grows up should strive to study in an inclusive class,” notes Ksenia. nine0004

There is no definite answer to the question of which educational institution is best suited for a child with visual impairment. “Each child is unique. Which institution is more suitable for a particular child can be advised by a special medical-psychological-pedagogical commission, but the final decision rests with the child's parents,” says Ksenia Nikolaeva.

According to her, when choosing a kindergarten or school, first of all, you should pay attention to the presence of a highly qualified, friendly and motivated team of specialists. “The collaborative work of the staff, employees and parents, built on mutual respect and joint problem solving, can bring the highest results,” Ksenia believes. nine0004

How does a deaf-blind child know that "a" is "a"?

Ivan Afanasyevich Sokolyansky, the founder of the national system of education and upbringing of the deaf-blind, said that everyone who came to the small group for deaf-blind children, organized by him in 1955 at the Institute of Defectology of the APS of the RSFSR 1, asked this question.

Years passed. An orphanage for the deaf-blind was created and is successfully developing. An experiment on teaching four deaf-blind students at the Faculty of Psychology of Moscow State University was successfully completed. M.V. Lomonosov. The experience of teaching deaf-blind people is quite widely known in the country and abroad. Philosophers, psychologists, defectologists, publicists turn to him. Books written by deaf-blind people have been published, articles and books about deaf-blind people have been published, films and TV shows have appeared. nine0004

Philosophers, psychologists, defectologists, publicists turn to him. Books written by deaf-blind people have been published, articles and books about deaf-blind people have been published, films and TV shows have appeared. nine0004

However, even now, for the majority of people who first become acquainted with the achievements in teaching the deaf-blind, the very possibility of teaching them to read and write requires special explanation.

First of all, we note that the education of children with congenital or early acquired visual and hearing impairments does not begin with teaching them to read and write. The acquisition of literacy is preceded by the stage of the child’s initial entry into culture (“the stage of initial humanization”), when, in an activity shared with an adult, the child masters the simplest self-care skills, household culture items, elementary forms of sign activity and the first means of communication 2.

The second, no less important remark is that teaching deaf-blind children to read is correlated with the very initial stages of the development of their verbal speech. Possession of elementary literacy here solves the problem of perception of a speech message by the deaf-blind much more effectively than the previously developed methods of teaching the deaf-blind on the basis of tactile perception of the movements of the articulatory apparatus that are barely distinguishable by touch in the speaker orally (the Tadoma method) or fingers in the speaker dactyly. The teaching method, in which the perception of the word was based on the tactile perception of stable and clear relief and relief-dotted written signs used in teaching the blind, turned out to be the most reliable and most effective way to form verbal speech in deaf-blind students. nine0004

Possession of elementary literacy here solves the problem of perception of a speech message by the deaf-blind much more effectively than the previously developed methods of teaching the deaf-blind on the basis of tactile perception of the movements of the articulatory apparatus that are barely distinguishable by touch in the speaker orally (the Tadoma method) or fingers in the speaker dactyly. The teaching method, in which the perception of the word was based on the tactile perception of stable and clear relief and relief-dotted written signs used in teaching the blind, turned out to be the most reliable and most effective way to form verbal speech in deaf-blind students. nine0004

How does a child learn to read and write, just starting to master the vocabulary and grammatical structure of verbal speech?

Consider two historical examples.

Laura Bridgman

Laura Bridgman, a graduate of the Perkins School for the Blind (USA), was the first deaf-blind-mute whose successful training destroyed the notion that the deaf-blind were unteachable. Bridgman, who lost her hearing, sight and smell at the age of two, learned to read, write, express simple thoughts and perform some simple tasks. During L. Bridgeman's teaching, a linear embossed font was used, which was called Boston, which, to a greater or lesser extent, copied the letters of the alphabet for the sighted. The creator of this alphabet, Samuel Grilli Howe, began teaching L. Bridgman in 1837 when she was 8 years old. She knew how to take care of herself, helped her mother with the housework, communicated with her with elementary gestures, specially invented for their communication. In "American Notes" by C. Dickens, diary entries by S.G. Howe on teaching Laura to read. nine0004

Bridgman, who lost her hearing, sight and smell at the age of two, learned to read, write, express simple thoughts and perform some simple tasks. During L. Bridgeman's teaching, a linear embossed font was used, which was called Boston, which, to a greater or lesser extent, copied the letters of the alphabet for the sighted. The creator of this alphabet, Samuel Grilli Howe, began teaching L. Bridgman in 1837 when she was 8 years old. She knew how to take care of herself, helped her mother with the housework, communicated with her with elementary gestures, specially invented for their communication. In "American Notes" by C. Dickens, diary entries by S.G. Howe on teaching Laura to read. nine0004

“To begin with, we took items that a person uses every day, such as knives, forks, spoons, keys, etc., and pasted labels on them with names printed in raised letters. The girl felt them carefully and, naturally, soon noticed that the winding lines denoting the “spoon” resembled the line of the “key” as little as the spoon itself resembled the key. Then they began to give her labels already without objects, and soon she realized that the same signs were imprinted on them as on the labels pasted on objects. Wanting to show that she caught the resemblance, she put a tag with the word "key" on the key and a tag with the word "spoon" on the spoon. This was done with all the objects that she could take in her hands, and the girl very soon learned to find the right object and put a label on it with the appropriate name. nine0004

Then they began to give her labels already without objects, and soon she realized that the same signs were imprinted on them as on the labels pasted on objects. Wanting to show that she caught the resemblance, she put a tag with the word "key" on the key and a tag with the word "spoon" on the spoon. This was done with all the objects that she could take in her hands, and the girl very soon learned to find the right object and put a label on it with the appropriate name. nine0004

After some time, they began to give her not labels with a whole word, but individual letters printed on different pieces of paper. These pieces were laid out in such a way that the word “book”, “key”, etc. was obtained. And she did it. The teacher added words, and she, touching his hands, repeated the movements after him. The next step was metal type: letters were stuffed at the ends of metal sticks, and these sticks were inserted into a thick board with square holes so that only the letters stood out above the surface. Then the girl was given some object - a pencil or, say, a watch - she picked up the appropriate letters, stuck the sticks into the holes on the board and "read" what happened with obvious pleasure. nine0004

Then the girl was given some object - a pencil or, say, a watch - she picked up the appropriate letters, stuck the sticks into the holes on the board and "read" what happened with obvious pleasure. nine0004

She was taught this way for several weeks, until her vocabulary became sufficiently extensive, then they moved on to the next important step: leaving the bulky apparatus - a board with metal sticks, the girl began to be taught to represent letters with one or another position of the fingers. She learned it quite easily and quickly.” 3.

Elena Keller mastered the technique of reading and writing somewhat differently.

Elena Keller

She lost her hearing and sight at the age of 1 year 8 months. Systematic education based on fingerprinting and then Braille began in 1886 when the girl was 6 years old 9months. By this time, she was communicating with her family using gestures that she had invented herself.

If Laura Bridgman first mastered the written designation of familiar objects, and then, on this basis, the dactyl alphabet and dactylology, then Helen Keller already had 625 dactyl words in her dictionary by the beginning of her literacy and mastered elementary phrasal speech.

However, Anna Sullivan, her famous teacher, first tried to teach her to read in the same way that Howe taught Laura Bridgman (from the holistic perception of label words to understanding the letter composition of the word), but since the initial stage of Elena's teaching was different, more effective turned out to be a different method of learning, namely, a simple correlation of the written alphabet (Boston script) with the dactyl one. nine0004

Anna Sullivan talks about Helen Keller's teaching to read:

“I put the piece of paper with the word 'box' written in raised type on a wooden box and repeated the same with many objects. But she did not immediately guess that the printed word referred to the subject. Then I took a piece of paper with the alphabet printed on it in relief and ran my finger over the letter "A", while at the same time making the letter with my fingers. She moved her fingers in order through all the letters, watching my fingers. In one day she learned all the letters, simple and uppercase. Then I again took up the first page of the alphabet and ran it with my fingers over the word "cat" (cat), again simultaneously doing it with my fingers. In one second, everything became clear to her, and she immediately began to ask me to find her the word "dog" (dog) and many others "4.

Then I again took up the first page of the alphabet and ran it with my fingers over the word "cat" (cat), again simultaneously doing it with my fingers. In one second, everything became clear to her, and she immediately began to ask me to find her the word "dog" (dog) and many others "4.

Next, Elena completed the exercises in composing phrases from words specially printed for her in embossed Boston type. Then she was quickly taught to write in a stencil for the blind with a pencil. Anna Sullivan said: “It was not difficult for her to explain how to draw with a pencil on paper the same phrases that she daily composed of chopped words, and she very soon realized that she was not obliged to be content with memorized phrases, but that she could tell us everything in this way, whatever comes to her mind. As soon as she learned to express her thoughts on paper, I taught her to write in dotted Braille (dots pressed from the inside, arranged in conditional groups that come out slightly convex on the right side). She began to study hard as soon as she realized that according to this system she herself could read what was written. And it gives her inexhaustible pleasure. She sits at the table in the evenings and writes everything that comes to her mind, and I almost always can easily read what she wrote.0004

She began to study hard as soon as she realized that according to this system she herself could read what was written. And it gives her inexhaustible pleasure. She sits at the table in the evenings and writes everything that comes to her mind, and I almost always can easily read what she wrote.0004

As can be seen from the above examples, the use of reading and writing in order to form elementary verbal speech in a deaf-blind child makes the process of mastering literacy extremely different from what takes place when teaching hearing and seeing children.

As is known, in the classical version of education, seeing and hearing children acquire literacy based on oral speech, which they have already mastered to a sufficient extent by the time they enter school. Children by this time already speak well and understand the speech addressed to them, they are able to extract the necessary information from it. Therefore, teaching literacy to a hearing and seeing child presupposes, first of all, the assimilation of a system of signs denoting the sounds and words of oral speech, which in turn are signs for real objects and phenomena. In the famous work of L.S. Vygotsky “On the Prehistory of the Development of Written Speech”, it is noted that written speech is “symbolism of the second degree”, while oral speech serves as direct symbolism, “symbolism of the first degree” 6.

In the famous work of L.S. Vygotsky “On the Prehistory of the Development of Written Speech”, it is noted that written speech is “symbolism of the second degree”, while oral speech serves as direct symbolism, “symbolism of the first degree” 6.

Relations between the word depicted on the letter and the object designated by it develop differently when teaching deaf-blind children to read and write.

As can be seen from L. Bridgeman's description of learning, a deaf-blind child can master the written form of speech when he does not yet master any other form of verbal speech. Therefore, the word depicted in letters in writing is assimilated by him not as a designation of a sounding word, but as a sign of an object, a familiar thing, i.e. as "symbolism of the first degree". nine0004

When teaching E. Keller in this capacity, the dactyl form of speech was first assimilated, and the written signs were then memorized as designations of already known dactyls. In order to characterize the peculiarities of teaching deaf-blind children to read and write, it is important to emphasize here that no matter in what sequence and to what extent the written and tactile forms of speech are acquired by the deaf-blind child, initially the deaf-blind child learns precisely the letter structure of the word. And it is precisely the word in its literal representation that appears to him as "symbolism of the first degree." Due to this, the technical side of reading, which includes the recognition of written characters and their replacement with the corresponding dactylemas, is formed relatively easily in a deaf-blind child, since dactyl speech corresponds to written speech in its letter composition. However, the skill of replacing letters with dactylemas when reading a deaf-blind child provides reading comprehension only in cases where words and phrases are offered for reading, which he initially learned on a dactyl basis. nine0004

And it is precisely the word in its literal representation that appears to him as "symbolism of the first degree." Due to this, the technical side of reading, which includes the recognition of written characters and their replacement with the corresponding dactylemas, is formed relatively easily in a deaf-blind child, since dactyl speech corresponds to written speech in its letter composition. However, the skill of replacing letters with dactylemas when reading a deaf-blind child provides reading comprehension only in cases where words and phrases are offered for reading, which he initially learned on a dactyl basis. nine0004

I.A. Sokolyansky, developing a methodology for teaching deaf-blind children to read and write, showed that the easiest and most effective way is to master the reading technique based on dactylology and the dactyl alphabet. However, he emphasized that for this it is enough to memorize one or two dozen words firmly, denoting objects well known from experience. 7.

performs the function of controlling the correct perception of written characters, without providing reading comprehension by itself. nine0004

These circumstances make the process of teaching a deaf-blind child to read extremely different from how it happens in the primary classes of a mass school. As already noted, a hearing and seeing child who begins to read understands well the sounding speech addressed to him, and not only colloquial, situational, but also bookish, literary, which he is already accustomed to perceive in rather difficult communicative conditions - when perceiving audio recordings, television and radio programs. .

In order to understand speech depicted on paper by written signs, such a child must learn, firstly, to distinguish between these signs, and secondly, and this is the most important and difficult thing, to learn to recreate the sound form of a word according to its letter model. The correct performance of this action at this stage of learning is a necessary and sufficient condition for understanding the material offered for reading, in the case, of course, when this material does not differ in structure, lexical and grammatical design and genre features from the speech material that the child is learning to read. already well understood by ear. In this regard, in his book "How to teach children to read" D.B. Elkonin, considering the initial stage of teaching reading in a public school, writes: “At the beginning of learning from the primer, the conscious goal of the student, which the teacher sets and to achieve which he gives the student the appropriate techniques, is to recreate the sound form of the word” 8.

already well understood by ear. In this regard, in his book "How to teach children to read" D.B. Elkonin, considering the initial stage of teaching reading in a public school, writes: “At the beginning of learning from the primer, the conscious goal of the student, which the teacher sets and to achieve which he gives the student the appropriate techniques, is to recreate the sound form of the word” 8.

The discrepancy between the phonemic system and the alphabetic system of writing, which is characteristic of most modern languages, makes the solution of this problem methodologically rather complicated. At the same time, the understanding of the text is achieved relatively easily, because. this goal is served by the "mechanisms" that have developed in the child even before school. Noting this feature of the initial reading, D.B. Elkonin emphasizes that “understanding is necessary and important, but at this stage it acts more as a way to control the correctness of the action being performed than as the main task: understood means you read it correctly” 9.

A deaf-blind child beginning to learn to read and write does not yet have any ready-made "mechanisms" for understanding coherent speech, just as there is no vocabulary and the ability to use grammatical forms.

Such a child must be taught to understand a coherent text. The beginning of this path - the "departure station" - can be considered the reading of texts that describe the simplest situations in the life of the child himself.

When reading such texts, a deaf-blind child learns to correlate the text and the event it describes. When such a skill develops, reading texts describing the events of a child's life becomes an invaluable means of developing his vocabulary and the grammatical structure of verbal speech. The story of A. Sullivan about how E. Keller first read a coherent text can serve as an illustration of what has been said. nine0004

“I remember very well,” Anna Sullivan said, “her first attempt at a short story. She already knew the printed letters and for some time, as if for fun, composed simple phrases, using pieces of paper with raised letters printed for this, but these phrases had no special connection with each other. It happened one morning that a mouse was caught, and it occurred to me that, having a live cat and a live mouse with which to interest it, I might be able to arrange something like a little story out of several separate phrases and thereby give it a new visual the concept of the benefits and meaning of speech. I made up the following phrases from raised letters in the frame available for this and gave them to Elena: “The cat is sitting on a box. There is a mouse in the box. The cat can see the mouse. The cat really wants to eat the mouse. Don't let the cat eat the mouse. A cat can be given milk, but a mouse should be given rolls. nine0004

It happened one morning that a mouse was caught, and it occurred to me that, having a live cat and a live mouse with which to interest it, I might be able to arrange something like a little story out of several separate phrases and thereby give it a new visual the concept of the benefits and meaning of speech. I made up the following phrases from raised letters in the frame available for this and gave them to Elena: “The cat is sitting on a box. There is a mouse in the box. The cat can see the mouse. The cat really wants to eat the mouse. Don't let the cat eat the mouse. A cat can be given milk, but a mouse should be given rolls. nine0004

Familiar words made her smile happily. When I laid her hand on the cat, which was really sitting on a mousetrap, she gave a little cry of surprise, and the meaning of the whole first sentence became completely clear to her. When she read the words of the second sentence, I showed her that there really was a mouse in the box. She had already moved her finger to the next line with an expression of lively curiosity: "The cat can see the mouse. " Then I turned the cat to face the mouse and made Elena feel it.

" Then I turned the cat to face the mouse and made Elena feel it.

The expression on the girl's face showed that she was puzzled. I drew attention to the next line, and although she knew only three words in it: cat, mouse, eat, however, she caught the meaning: she took off the cat and put it on the floor, and covered the mousetrap with a scarf. Then she read the phrase: "Don't let the cat eat the mouse." The last phrase contained all the familiar words, and she enthusiastically took advantage of the permission to do what was said in it.0004

The ease and interest noted by A. Sullivan, with which Elena mastered a new type of activity for her, do not hide, however, those difficulties in the verbal mediation of the perception of an objective situation by a deaf-blind child that took place in this case. Note that in this example we were talking about the description of a static situation. When it becomes necessary to verbally mediate the events unfolding in space and time before a deaf-blind child, these difficulties increase immeasurably. nine0004

nine0004

The formation of connections between the designated and the designation in a deaf-blind child is difficult and limited primarily by difficulties in perceiving the surrounding reality on the basis of "limited sensory input", as well as by the fact that the perception of reality and the perception of speech in such a child is carried out using the same analyzer , which means that it does not occur simultaneously, as in the norm, but alternately, sequentially.

Given this feature, I.A. Sokolyansky suggested that as the main material, on which at this stage of training the vocabulary and grammatical structure of verbal speech will be formed, to use not so much a description of the present, "here and now" events unfolding before the child, as a description of past events and situations from his daily life, but precisely those whose direct and main character in the recent or distant past was the child himself. nine0004

A method of forming the grammatical structure of verbal speech in a deaf-blind child, developed by I. A. Sokolyansky, was called the system of parallel texts.

A. Sokolyansky, was called the system of parallel texts.

System of parallel texts

According to this system, children are asked to describe events from their lives (the so-called spontaneous texts). At the same time, they are given to read texts compiled by the teacher, which also first describe events in the child's life. These are educational texts.

The first educational texts consist of several uncommon, extremely specific sentences, which are arranged one below the other in a column in a strict logical sequence. For example:

Serezha is coming. The series is cleaning. The series washes. The series is wiping. Serezha cleans 11.

“Such a stylistic construction of educational texts,” wrote I.A. Sokolyansky, “concentrates the child’s attention not on verbal design, but on specific images of concrete material reality, studied not in the form of separate disparate objects and actions, but objects and actions logically related to each other” 12. Gradually, educational texts become more complex. First, one new grammatical category is introduced - the direct object. For example: nine0004

Gradually, educational texts become more complex. First, one new grammatical category is introduced - the direct object. For example: nine0004

Julia opened the faucet. Julia took the soap. Julia washed her hands. Julia took a towel. Julia wiped her hands. Julia hung up the towel. Yulia removed the soap 13.

Further, according to a certain system, other categories are introduced into educational texts - various forms of verbs, adjectives, pronouns, adverbs, the syntax becomes more complicated, for example:

Nina took the dishes and went to the kitchen for dinner. The cook poured soup into one pan, put a cutlet with potatoes into another pan, and poured compote into the third pan. Nina brought dinner into the room and told Yulia: "Go wash your hands." Julia put on a dressing gown, slippers, took a towel and soap and went to the washstand. Yulia washed her hands, came into the room, put the soap in the drawer and hung the towel on the bed. Yulia spread the oilcloth on the table and put the breadbasket with bread on the table. Julia took a plate with a spoon and a ladle from the bedside table. Yulia poured the soup into a bowl from the pot and ate the soup with bread. Yulia put the patty and potatoes in a plate from the pan and ate the patty with potatoes. Yulia poured compote into a cup from the pan and ate compote with bread. Julia put the dishes and the bread box with bread into the nightstand. Julia spread out the bed, undressed and went to bed. nine0078

Julia took a plate with a spoon and a ladle from the bedside table. Yulia poured the soup into a bowl from the pot and ate the soup with bread. Yulia put the patty and potatoes in a plate from the pan and ate the patty with potatoes. Yulia poured compote into a cup from the pan and ate compote with bread. Julia put the dishes and the bread box with bread into the nightstand. Julia spread out the bed, undressed and went to bed. nine0078

Describing the experienced event in a spontaneous text, the student uses the new words and grammatical categories given in the educational text and reinforces them already on familiar material. Let us give an example of a spontaneous text written by Yulia Vinogradova in 1956:

Yulia went to the kitchen. Julia took the frying pan. Julia took the bread from the table. Yulia crumbled bread into a frying pan. Julia took the frying pan and went outside. Julia put the frying pan on the ground. Geese and ducks ate bread. Julia took the frying pan. Julia went home. Julia put the frying pan on the floor. Julia washed her hands. Julia dried her hands with a towel. nine0078

Julia went home. Julia put the frying pan on the floor. Julia washed her hands. Julia dried her hands with a towel. nine0078

I.A. Sokolyansky attached great importance to the work on the system of parallel texts. He pointed out that it is at this stage that the fate of mastering the grammatical structure of verbal speech is decided, and the “secret” of mastering the grammatical structure of verbal speech for a deaf-blind child lies in lengthy exercises on texts specially compiled by the teacher 14. A.I. Meshcheryakov emphasized that all words, phrases and grammatical categories used in the educational text are superimposed "on the system of figurative and effective thinking" 15.

Work on this system also has a great organizing influence on the formation of the subject experience of a deaf-blind child, on the restructuring and clarification of his ideas about the world around him, and in general makes it possible to create more and more complex educational texts for him and even offer works of children's literature for reading.

So, due to the peculiarities of teaching a deaf-blind child to read and write, the process of mastering the technical side of reading turned out to be a completely solvable task. The main and extremely complex problems that accompany the reading of a deaf-blind person throughout his life lie in the plane of reading comprehension. nine0004

Difficulties, as we have seen, already arise when reading texts describing events from the life of the child himself, i.e. at the stage of mastering situational speech, which is normally formed in children already at an early age due to the fact that sounding speech accompanies and mediates all his actions and observations from the first days of life.

A deaf-blind child masters this first form of speech at a later age and under special, specially created conditions: on the basis of a dactyl or written form of speech, with the help of a system of parallel texts proposed by I.A. Sokolyansky. We add that a necessary link in the implementation of verbal mediation of actions and observations of a deaf-blind child is the preliminary creation of a “story” about the events of his life with the help of the types of visual activity available to him. The text correlates with reality, which a deaf-blind child gradually masters, not directly and directly, but through the image (modeling, bas-relief, application, drawing) 16.

The text correlates with reality, which a deaf-blind child gradually masters, not directly and directly, but through the image (modeling, bas-relief, application, drawing) 16.

Thus, thanks to special pedagogical tools, difficulties in understanding texts that describe events in the life of the child reader themselves are gradually overcome, and reading such texts becomes the source of the first positively colored, but still non-specific reading experiences of a deaf-blind child associated at this stage of learning with pleasure from recognizing when reading words denoting well-known objects, actions and situations - everything that is connected with his daily life. nine0004

Significantly more complex problems in reading comprehension arise in the deaf-blind at later stages of learning, when texts become the material for reading, the content of which goes beyond their direct experience17. But this is a subject of special discussion.

* The study was carried out within the framework of the State Assignment of the Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution of Institutes of Psychology and Communications of the Russian Academy of Education (No.