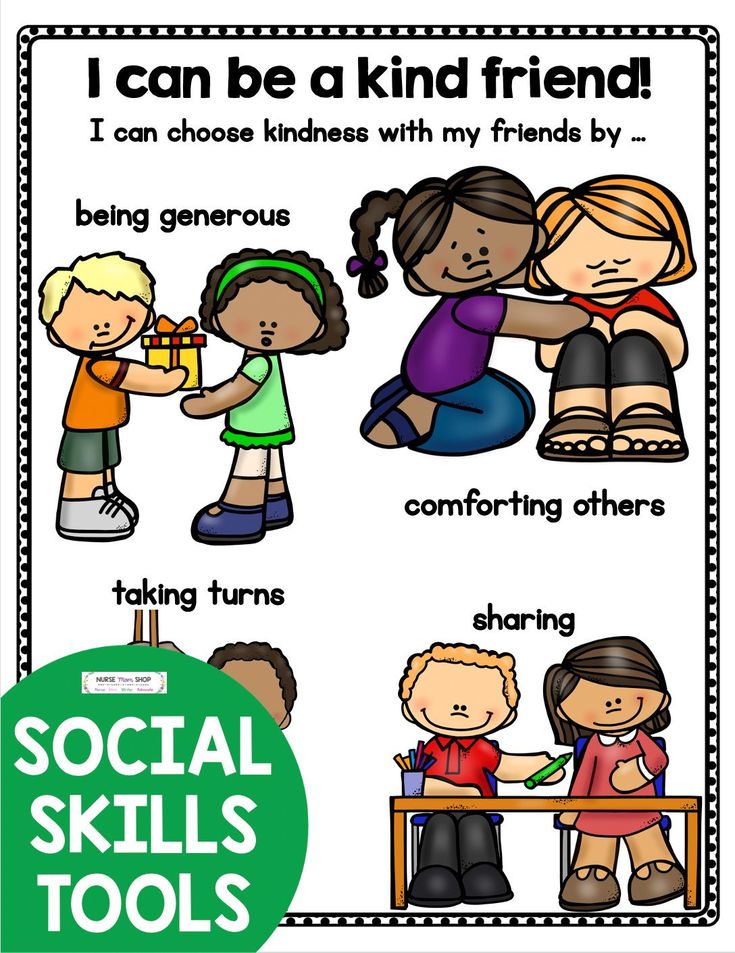

Teaching social skills activities

9 Ways to Teach Social Skills in Your Classroom

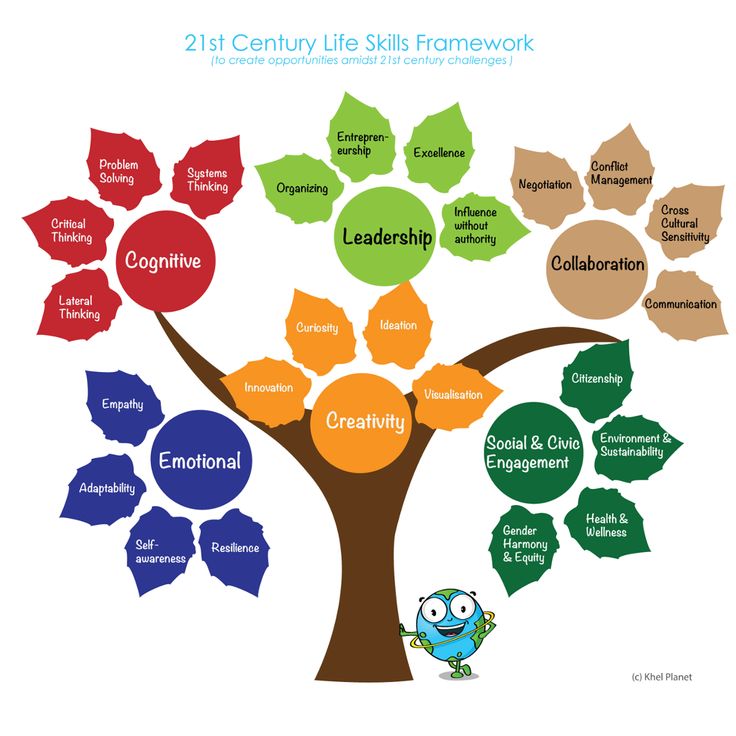

Research and experience has told us that having social skills is essential for success in life. Inclusive teachers have always taught, provided and reinforced the use of good social skills in order to include and accommodate for the wide range of students in the classroom.

Essentially, inclusive classrooms are representations of the real world where people of all backgrounds and abilities co-exsist. In fact, there are school disctricts with curriculum specifically for social and emotional development.

Here are some ways in which you can create a more inclusive classroom and support social skill development in your students:

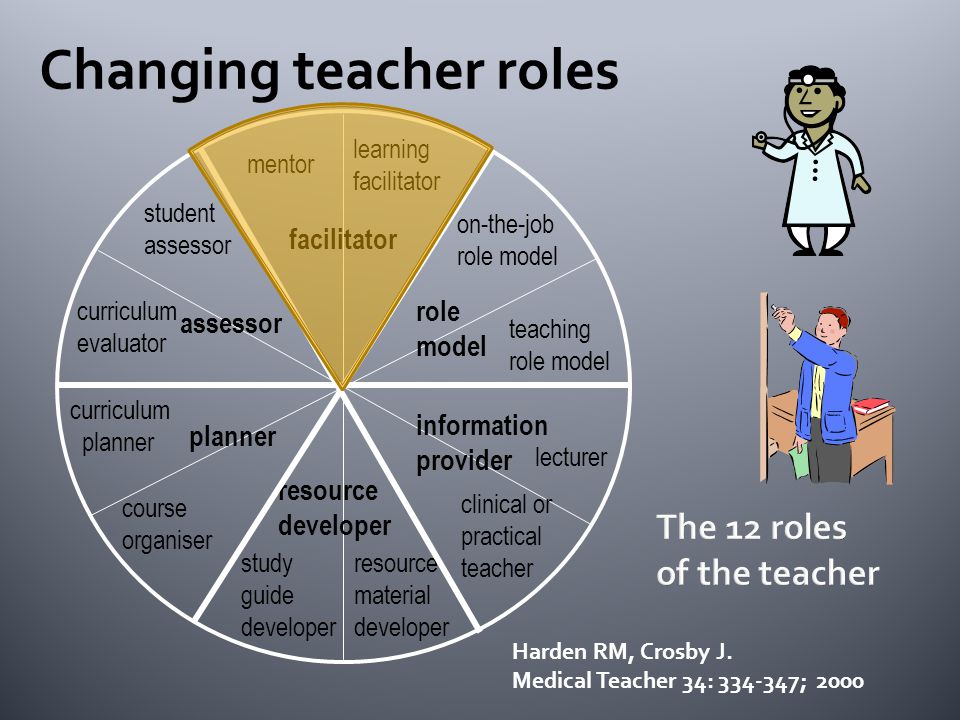

1. Model manners

If you expect your students to learn and display good social skills, then you need to lead by example. A teacher's welcoming and positive attitude sets the tone of behaivor between the students. They learn how to intereact with one another and value individuals. For example, teachers who expect students to use "inside voices" shouldn't be yelling at the class to get their attention.

In other words, practice what you preach.

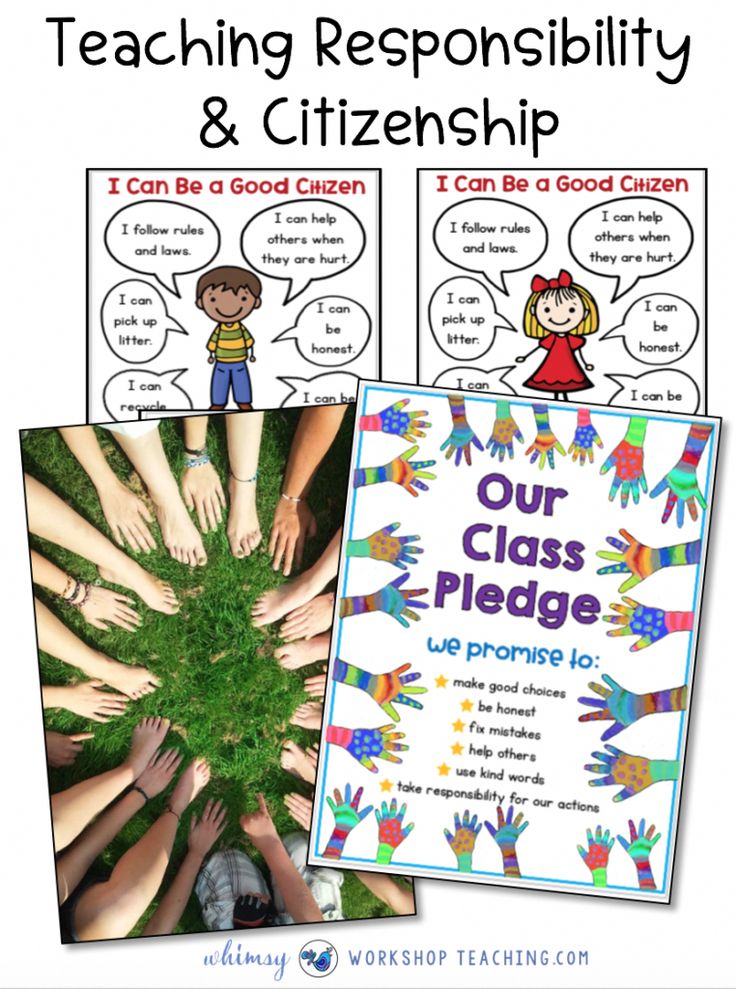

2. Assign classroom jobs

Assigning classroom jobs to students provides opportunties to demonstrate responsibility, teamwork and leadership. Jobs such as handing out papers, taking attendance, and being a line-leader can highlight a student's strengths and in turn, build confidence. It also helps alleviate your workload! Teachers often rotate class jobs on a weekly or monthly basis, ensuring that every student has an opportunity to participate. Check out this list of classroom jobs for some ideas!

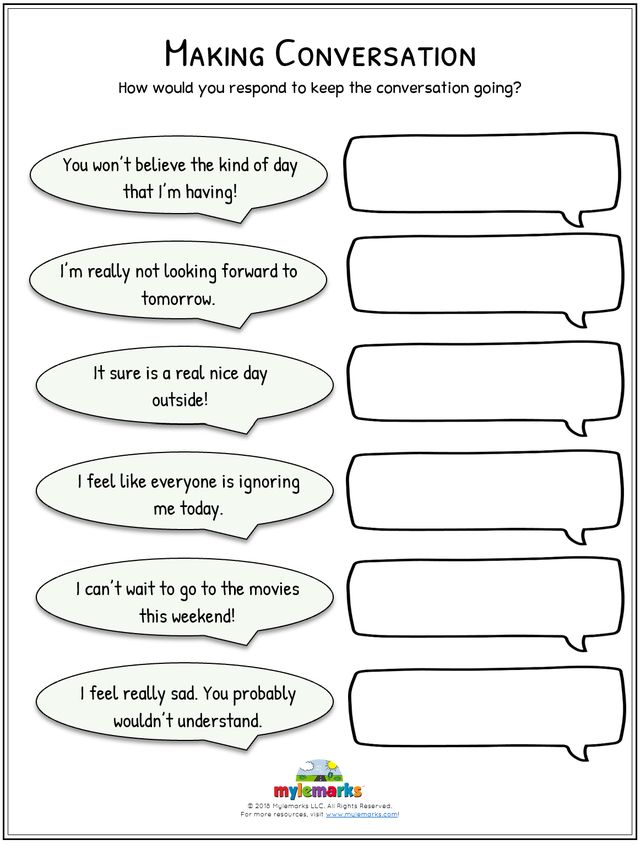

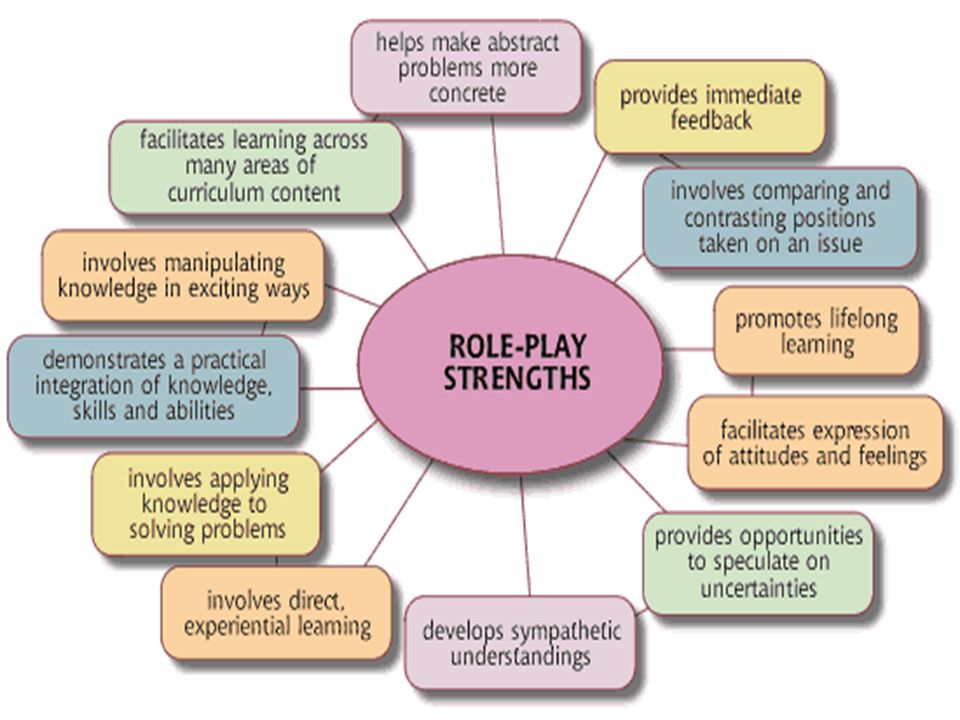

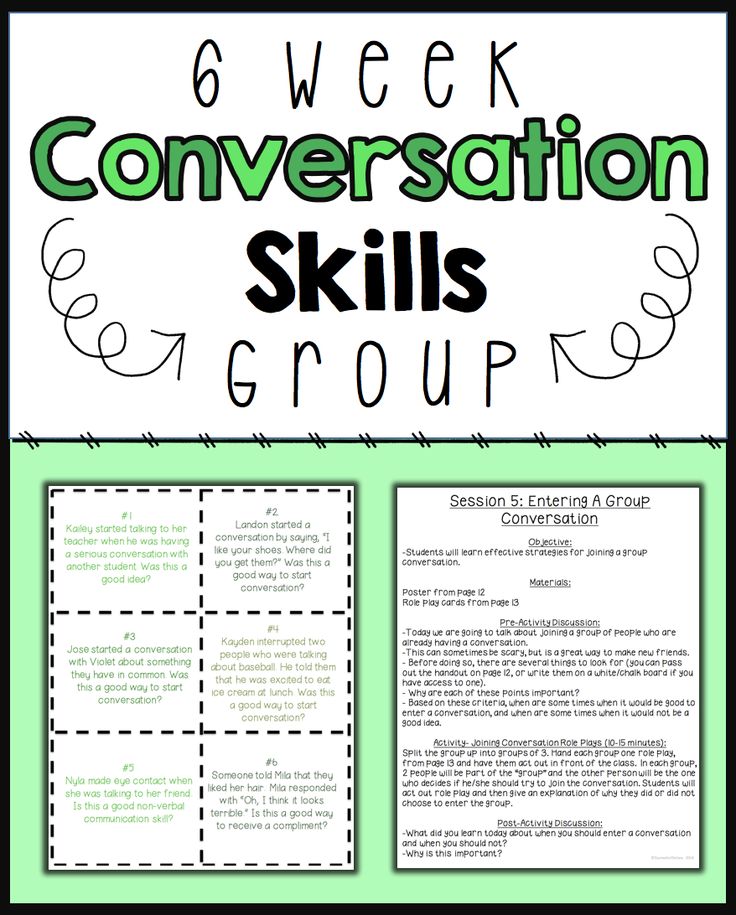

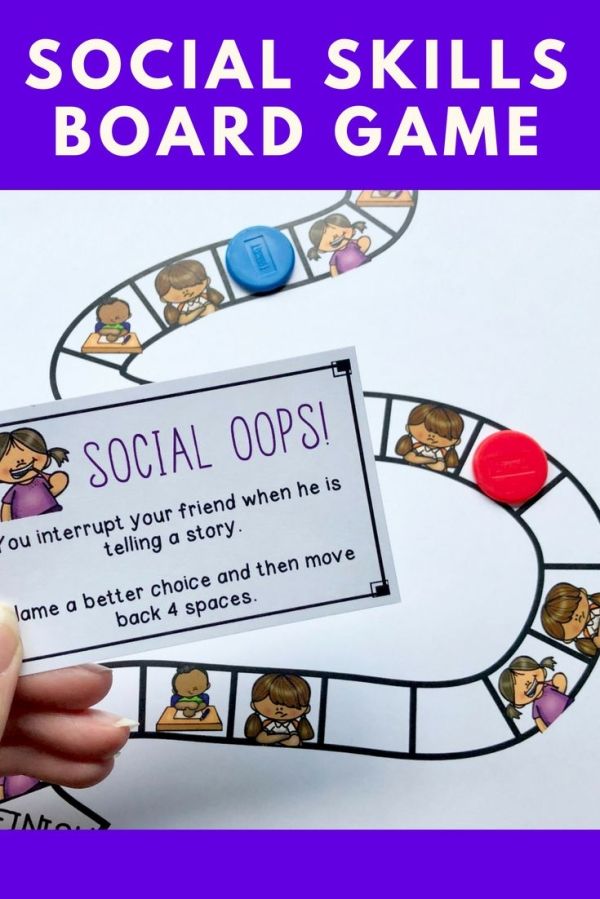

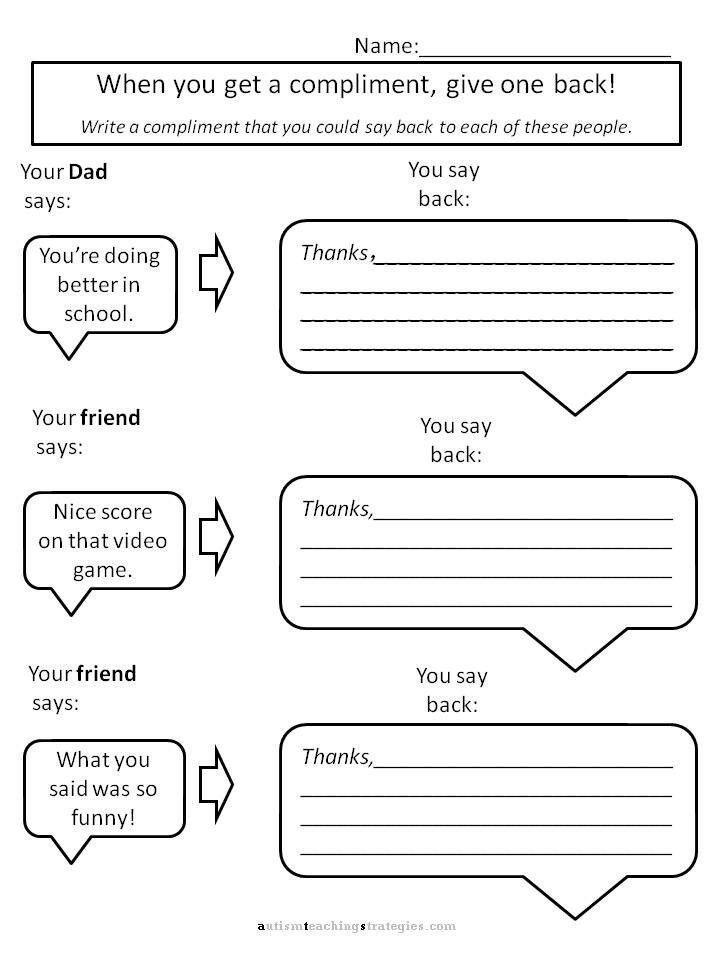

3. Role-play social situations

As any teacher knows, it's important to not only teach the students a concept or lesson but then give them a chance to practice what they have learned. For example, if we teach students how to multiply, then we often provide a worksheet or activity for the students to show us their understanding of mulitiplication. The same holds true for teaching social skills. We need to provide students with opportunities to learn and practice their social skills. An effective method of practice is through role-playing. Teachers can provide structured scenarios in which the students can act out and offer immediate feedback. For more information on how to set-up and support effective role-playing in your classroom have a look at this resource from Learn Alberta.

An effective method of practice is through role-playing. Teachers can provide structured scenarios in which the students can act out and offer immediate feedback. For more information on how to set-up and support effective role-playing in your classroom have a look at this resource from Learn Alberta.

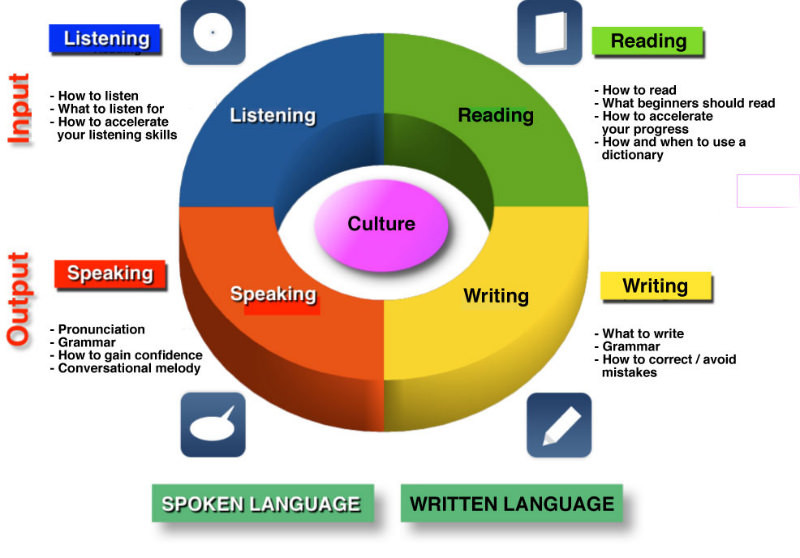

4. Pen-pals

For years, I arranged for my students to become pen-pals with kids from another school. This activity was a favorite of mine on many different academic levels; most importantly it taught students how to demonstrate social skills through written communication. Particularly valuable for introverted personalities, writing letters gave students time to collect their thoughts. It levelled the playing field for students who had special needs or were non-verbal. I was also able to provide structured sentence frames in which the kids held polite conversation with their pen-pal. Setting up a pen-pal program in your classroom takes some preparation before the letter writing begins. You want to ensure that students have guidelines for content and personal safety. This article, Pen Pals in the 21st Century, from Edutopia will give you some ideas!

You want to ensure that students have guidelines for content and personal safety. This article, Pen Pals in the 21st Century, from Edutopia will give you some ideas!

5. Large and small group activities

In addition to the academic benefits, large and small group activities can give students an opportunity to develop social skills such as teamwork, goal-setting and responsibility. Students are often assigned roles to uphold within the group such as Reporter, Scribe, or Time-Keeper. Sometimes these groups are self-determined and sometimes they are pre-arranged. Used selectively, group work can also help quieter students connect with others, appeals to extroverts, and reinforces respectful behavior. Examples of large group activities are group discussions, group projects and games. Smaller group activities can be used for more detailed assignments or activities. For suggestions on how to use grouping within your classroom, check out this article, Instructional Grouping in the Classroom.

6. Big buddies

We know that learning to interact with peers is a very important social skill. It is just as important to learn how to interact with others who may be younger or older. The Big Buddy system is a great way for students to learn how to communicate with and respect different age groups. Often an older class will pair up with a younger class for an art project, reading time or games. Again, this type of activity needs to be pre-planned and carefully designed with student's strengths and interests in mind. Usually, classroom teachers meet ahead of time to create pairings of students and to prepare a structured activity. There is also time set aside for the teacher to set guidelines for interaction and ideas for conversation topics. Entire schools have also implemented buddy programs to enrich their student's lives. Here is an article that offers tips on how to start a reading buddy program.

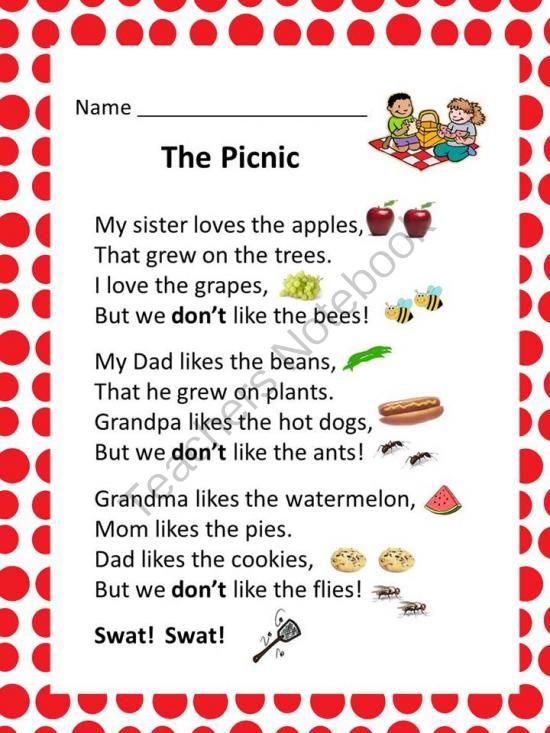

7. Class stories

There are dozens of stories for kids that teach social skills in direct or inadvertant ways. Find strategies to incoporate these stories in your class programs. You can set aside some time each day to read-aloud a story to the entire class or use a story to teach a lesson. Better yet, have your class write their own stories with characters who display certain character traits.

Find strategies to incoporate these stories in your class programs. You can set aside some time each day to read-aloud a story to the entire class or use a story to teach a lesson. Better yet, have your class write their own stories with characters who display certain character traits.

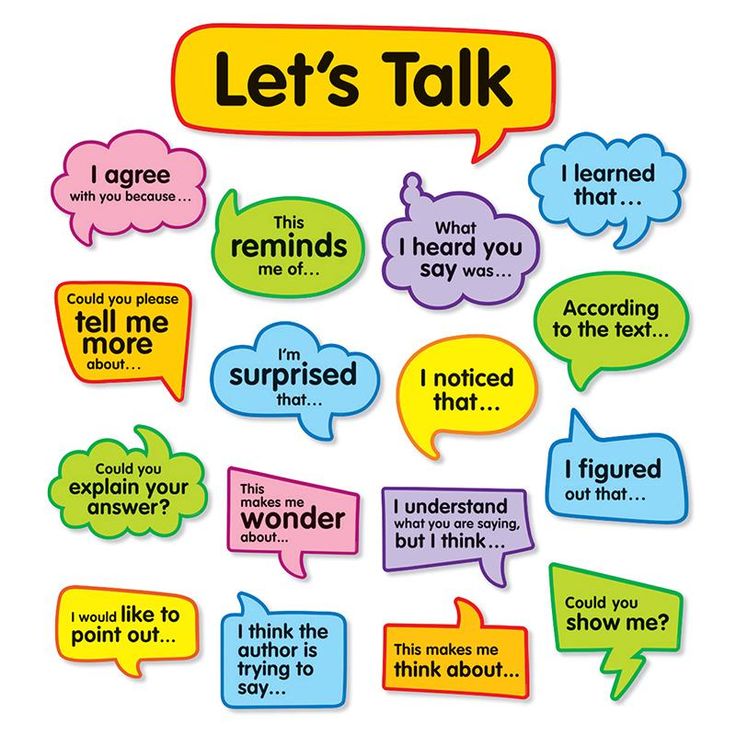

8. Class meeting

Class Meetings are a wonderful way to teach students how to be diplomatic, show leadership, solve problems and take responsibility. They are usually held weekly and are a time for students to discuss current classroom events and issues. Successful and productive meetings involve discussions centered around classroom concerns and not individual problems. In addition, it reinforces the value that each person brings to the class. Before a class meeting, teachers can provide the students with group guidelines for behavior, prompts, and sentence frames to facilitate meaningful conversation. Here is a great article, Class Meetings: A Democratic Approach to Classroom Management, from Education World that describes the purpose and attributes of a class meeting.

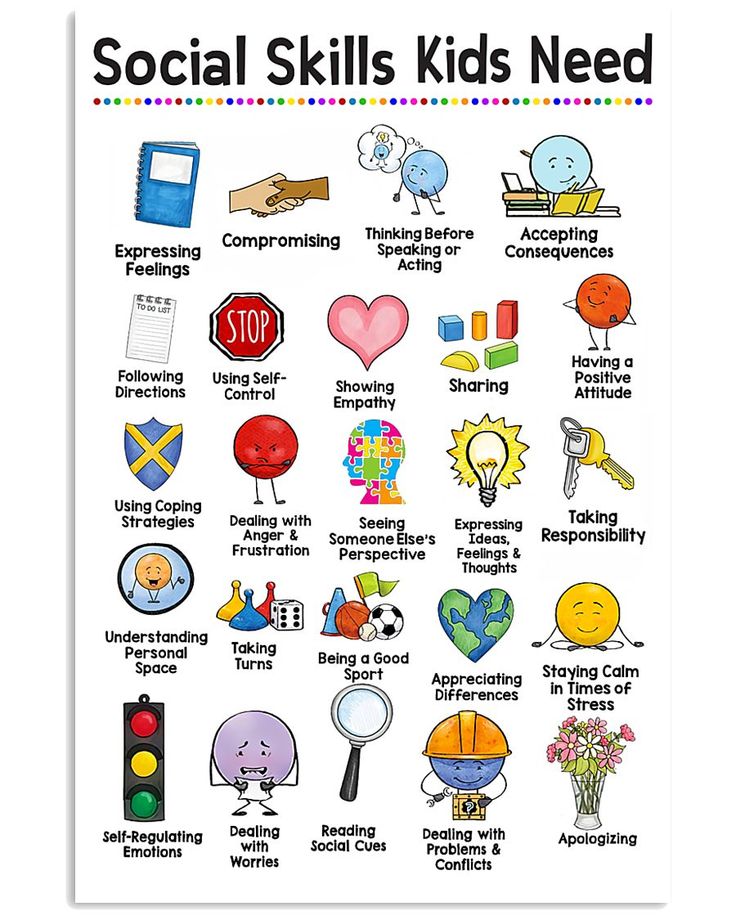

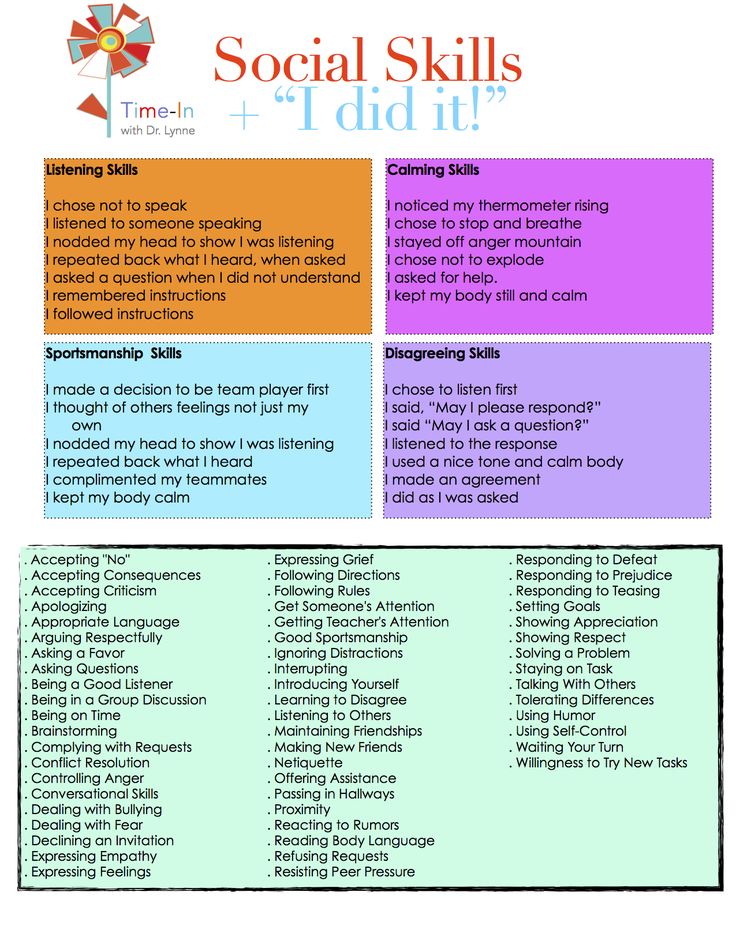

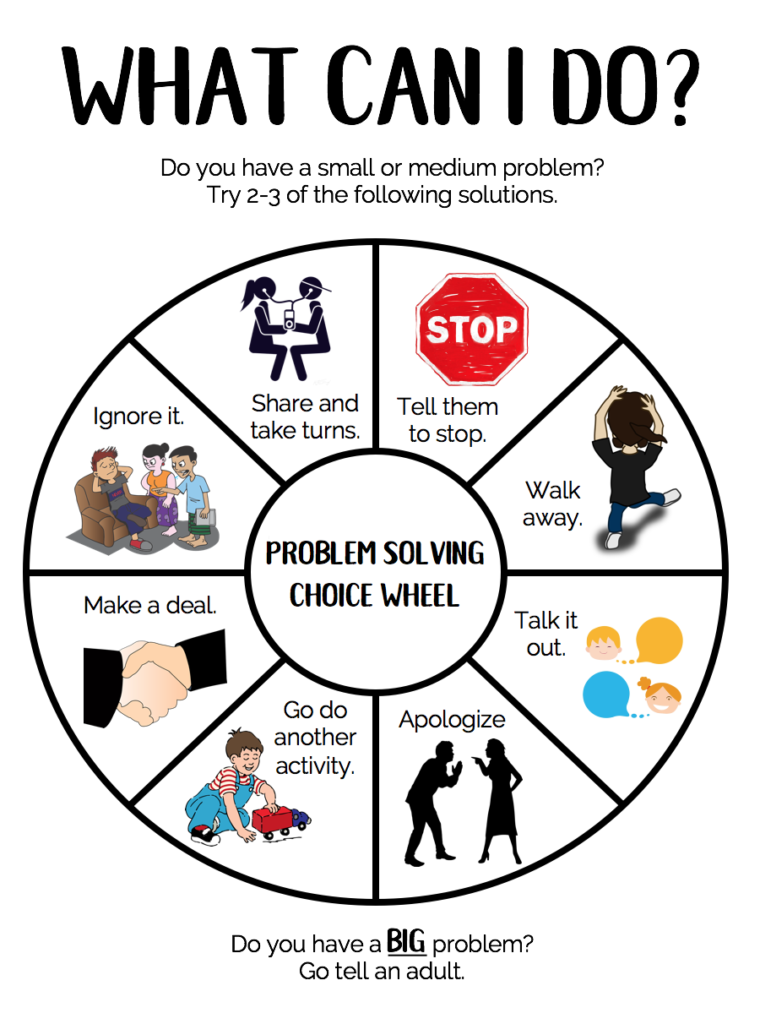

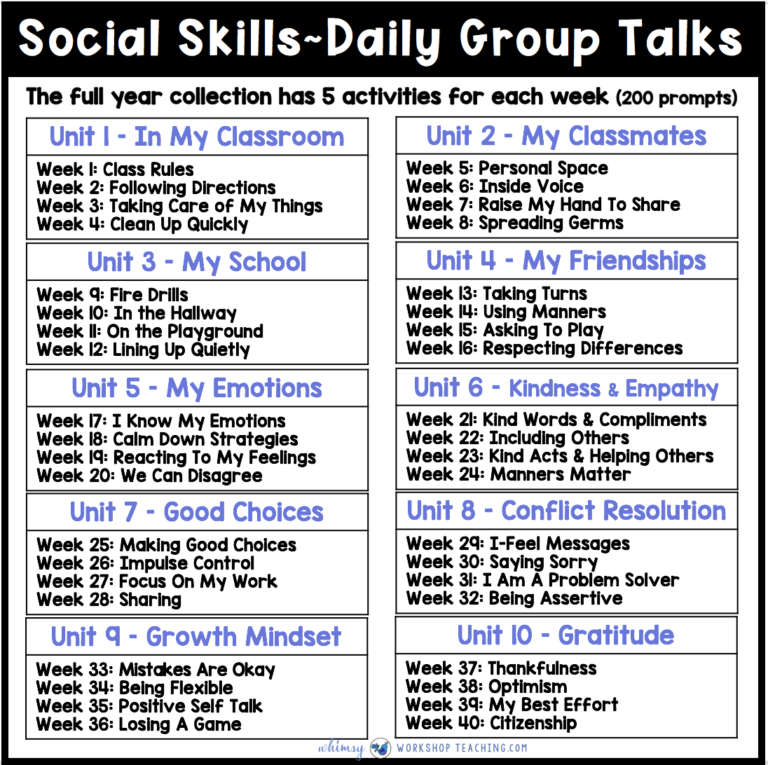

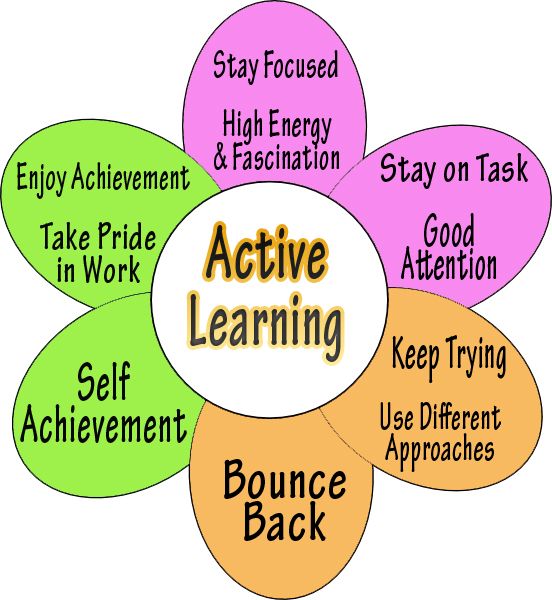

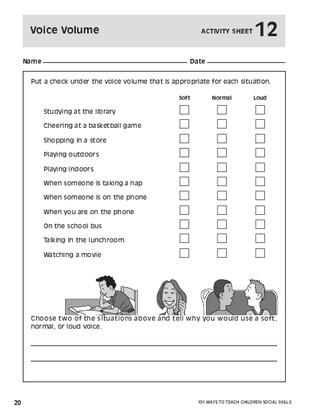

9. Explicit instruction

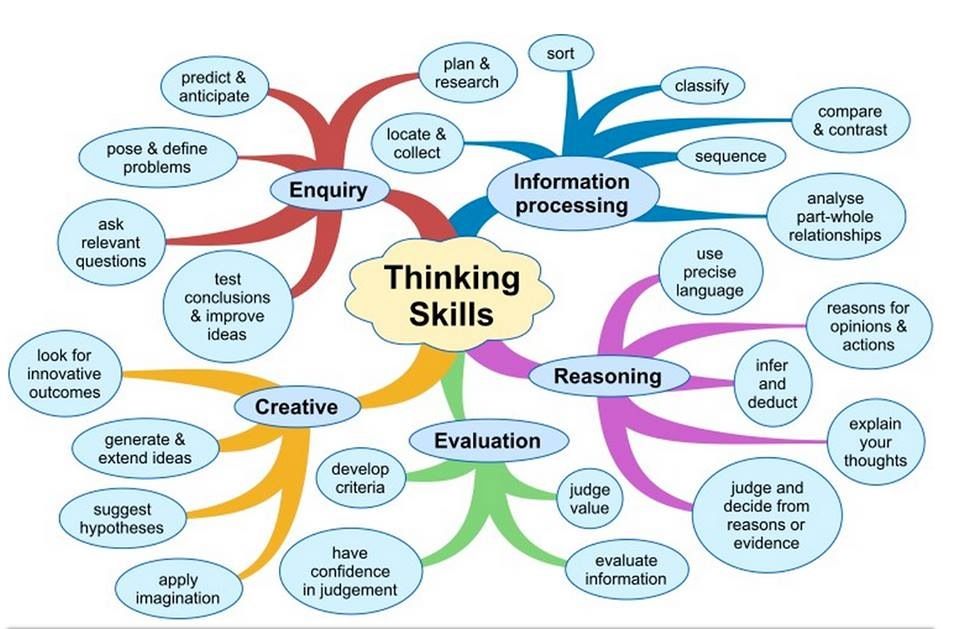

Finally, teachers can carve out a time in their curriculum to directly teach social skills to their students. Research-based programs such as Second Step provide teachers and schools with explicit lessons for social development. These programs can provide schools and classrooms with a common language, set of behavior expectations, and goals for the future. I have used programs such as Second Step in my classrooms with much success!

Nicole Eredics is an educator who specializes in the inclusion of students with disabilities in the general education classroom. She draws upon her years of experience as a full inclusion teacher to write, speak, and consult on the topic of inclusive education to various national and international organizations. She specializes in giving practical and easy-to-use solutions for inclusion. Nicole is creator of The Inclusive Class blog and author of a new guidebook for teachers and parents called, Inclusion in Action: Practical Strategies to Modify Your Curriculum. For more information about Nicole and all her work, visit her website.

For more information about Nicole and all her work, visit her website.

Related Topics

Social-Emotional Learning

20 Evidence-Based Social Skills Activities and Games for Kids

Oct 14 2020

Positive Action Staff

•

SEL Articles

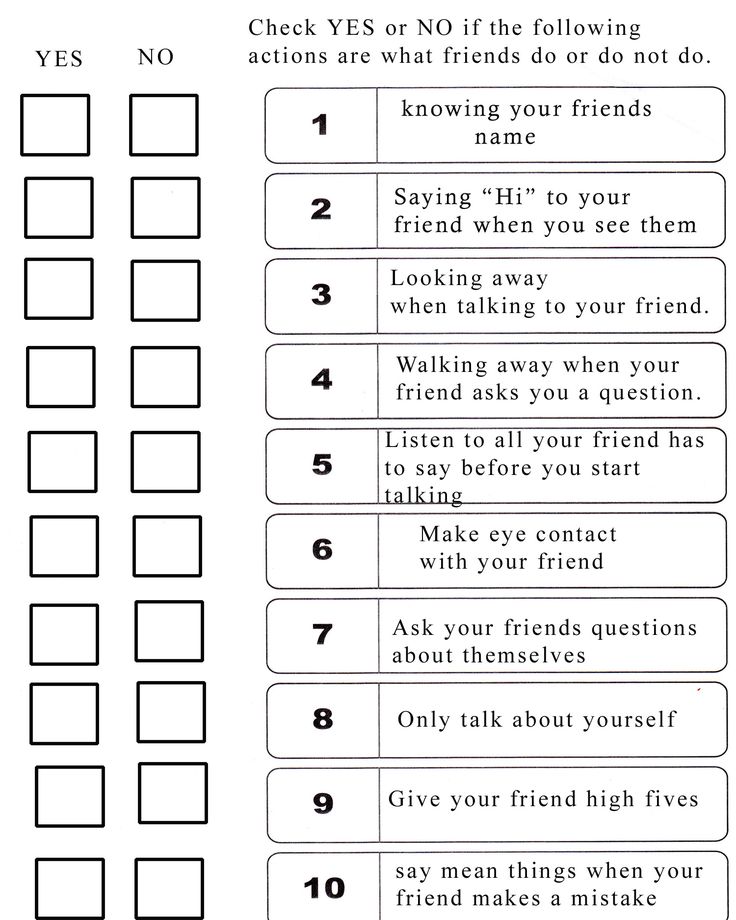

Activities and games for socialization are a great way for your child to learn how to behave around their peers, no matter if he is a toddler, preschooler or if he just started kindergarten. Games can teach skills like taking turns, managing emotions, and reading body language.

Use these evidence-based social skills activities to help your child build their social behaviors and learn how their actions affect others. With these games, they can become more independent and maintain healthy relationships throughout their lives.

1. Staring Contest

Many children have trouble maintaining eye contact in conversation. A staring contest can help kids make and keep eye contact in a way that allows them to focus on that task, rather than trying to communicate simultaneously.

If your child still feels uncomfortable, you can start smaller. Place a sticker on your forehead for them to look at and then build toward having a conversation.

2. Roll the Ball

It’s never too early to start building social skills, and a game of roll the ball suits children as young as toddlers. Kids take turns rolling a ball back and forth between them, laying the foundation for other social skills.

Kids learn to carry this skill into taking turns in conversation or when doing joint activities. They also learn self-control by aiming the ball toward their friend and rolling it hard enough to reach them yet with limited force.

3. Virtual Playtime

Sometimes, your child can’t have play dates in person, but they can still spend time together over video chat and other online spaces. Video chats help kids make eye contact by looking at their friend on the screen.

Learning to adapt to new situations becomes a valuable trait, whether with social distancing or in their future workplace. Coming up with new ways to spend time together increases problem-solving abilities, which adds to a set of vital social skills.

Coming up with new ways to spend time together increases problem-solving abilities, which adds to a set of vital social skills.

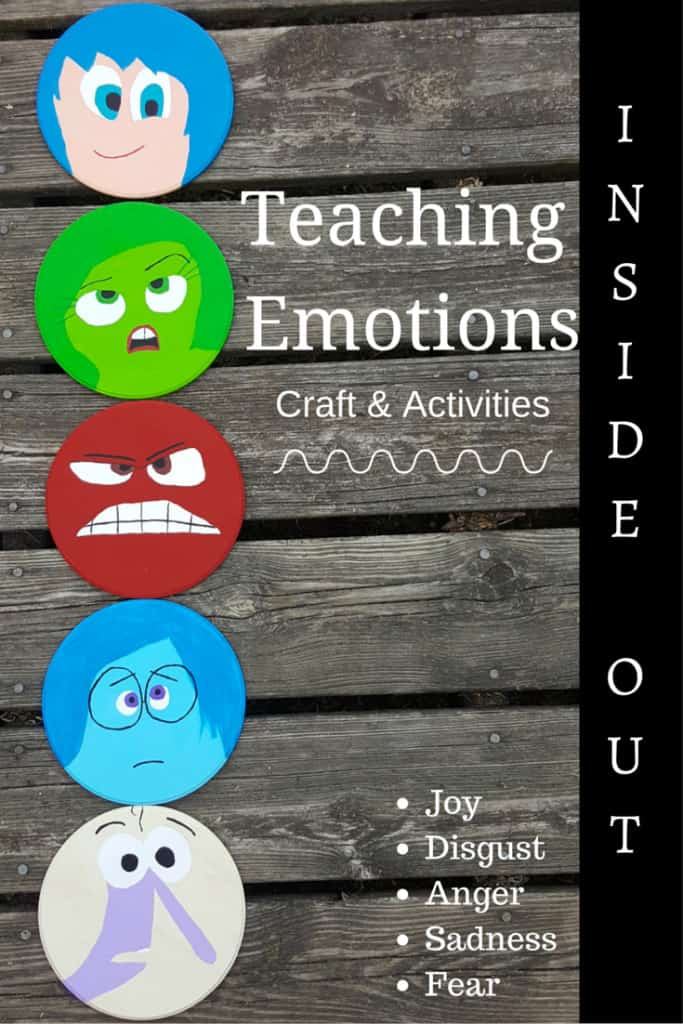

4. Emotion Charades

Emotion charades involves writing different emotions on strips of paper. Your child picks one out of a hat or bucket. Then, they must try to act out that emotion.

Emotion charades can help children learn to recognize emotions using facial and body cues. You can even adapt social skills activities like this to create a game similar to Pictionary, where children draw the emotion.

By depicting and acting out emotional expressions and reactions in social skills activities, children learn emotion management, which plays an important role in creating positive relationships and communicating feelings.

5. Expression Mimicking Games

When you play this game with your child, you're teaching social skills with expressions. Mimicking your expressions allows your child to understand what certain expressions mean and recognize them when others make them in real conversations.

When kids with social challenges learn to read facial expressions, they become more comfortable in situations involving them.

6. Topic Game

You can play several variations of the topic game, but the most common one involves choosing a topic and naming things that fit into that category using each letter of the alphabet. For example, if you choose animals as the topic, you might come up with:

- A: Aardvark

- B: Baboon

- C: Chicken

The topic game teaches kids to stick to one subject and follow directions until they complete the activity. It also helps them make connections and get creative with letters that have fewer options.

7. Step Into Conversation

Step Into Conversation is a card game made for children with autism. The game presents structured social skills activities, like starting a conversation and talking about specific subjects based on cards.

The game helps kids learn how to talk to others appropriately and carry a conversation with perspective and empathy. It teaches good manners and self-control by showing them how to politely enter a conversation, when to talk, and when to listen.

It teaches good manners and self-control by showing them how to politely enter a conversation, when to talk, and when to listen.

By using socialization games like this one, you give structure to conversations to develop the social skills necessary to handle different situations in their daily life.

8. Improvisational Stories

Many children tell stories even outside of intentional social skills activities. With improvisational stories, you add another challenge that requires them to collaborate and create a narrative without thinking about it beforehand.

For this activity, place cards with pictures or words face down. The child picks three of these cards, and they must include these objects or topics in the story they tell. The game ends when all the cards are gone, or the kids reach the end of their story.

You can use this activity as a multiplayer game where children take turns adding to the story and building on each other’s ideas, or one child can tell you their own story.

9. Name Game

With this simple game, kids roll or toss a ball to someone after they call out their name. Social skills activities like this one work well for helping even toddlers learn their peers’ names. It shows that they are attentive to others, and it’s a step toward getting to know other people.

10. Simon Says

Simon Says builds social skills for kids' self-control, listening, and impulse control as they copy their peers' movements and follow instructions. It also helps keep the attention on the game and rewards good behavior for those who follow the rules throughout the game.

11. Rhythm Games

You can incorporate rhythm games as a social skills activity both at home and in the classroom. These music-making games let your child be creative while following directions and recognizing patterns.

A 2010 study by Kirschner and Tomasello shows that joint music-making helps social behavior. In a game where children must “wake the frogs” with music, the researchers found that kids who followed the rules by making music were more likely to help others who tried waking the frogs with non-musical means.

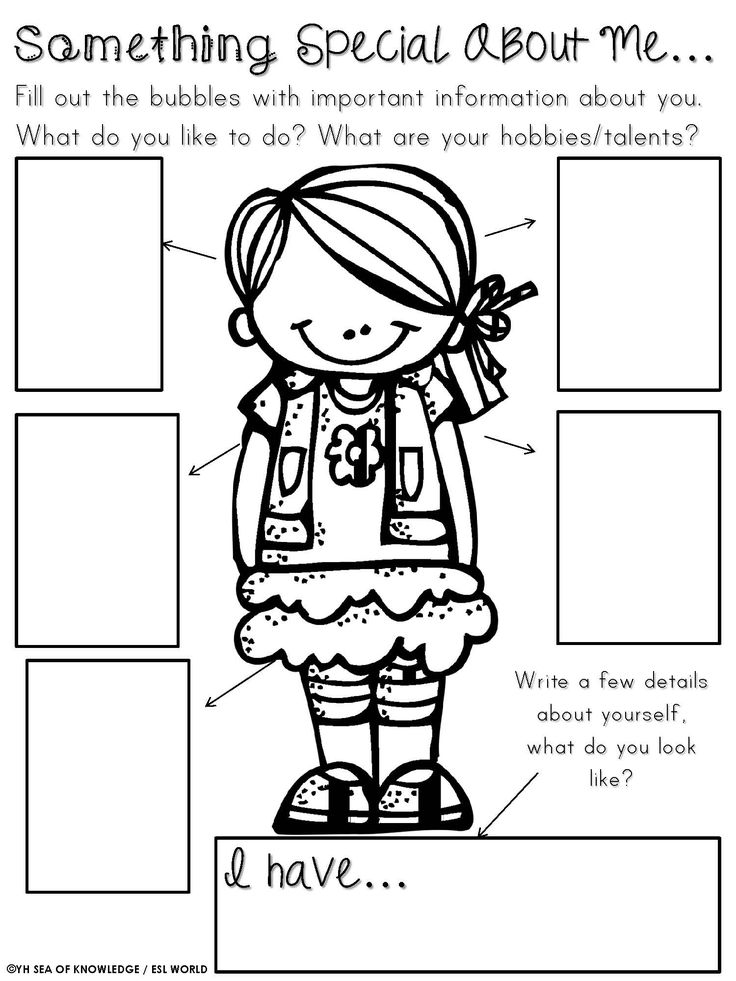

12. Playing with Characters

These social skills activities involve tapping into your child’s natural tendency to play. Using stuffed animals or dolls, you can interact with your child through the toys.

Having conversations through toys teaches kids to recognize behaviors and communicate their feelings. They practice their social skills through the toys in an imaginary, low-risk environment, without worrying about the toys’ hurt feelings.

13. Play Pretend

Kids will typically create a scenario in which they pretend to be someone or something else. For example, they might play house and take on the roles of parents, become a doctor, veterinarian, teacher, or cashier. Each of these situations allows them to explore different social skills activities.

As they pretend to parent another child, for instance, they must learn to recognize and respond to emotions, deescalate situations, and adapt to new situations.

14. Token Stack

You can adapt token stack from board games like checkers to create social skills activities that teach children how to have a considerate conversation. Every time the child speaks and responds appropriately, they add another token to their stack.

Every time the child speaks and responds appropriately, they add another token to their stack.

They face the challenge of trying to stack their tokens as high as possible while taking turns speaking. This activity makes them focus on having a calm conversation and giving thoughtful responses to questions and statements.

15. Decision-Making Games

Social skills activities like decision-making games come in many forms. By using strategy games or activities as simple as sorting and matching, your child learns persistence, thoughtfulness, and cooperation with others.

These games help kids with indecision, as they ask the child to make a choice, even if it’s not right the first time. It demonstrates low-risk consequences and encourages them to try again if they make a mistake.

16. Building Game

When children work together to build something, like a tower using blocks, they must communicate, take turns, and understand each other to bring their creation to life.

Kids will work together to come up with a method to build their item. When they apply it, they learn to try again if the creation falls and celebrate each other’s unique abilities when they finish the project successfully.

17. Community Gardening

Community gardening works differently than other social skills activities in that it teaches children to nurture a living thing.

Gardening with others increases social competence by having your child take care of something and learn responsibility, as they cannot neglect their plants. This activity also gets kids outdoor and can help calm them.

18. Team Sports

Children can participate in team sports through their school, on a recreational team, or even play with friends in their backyard. Team sports show kids how to work together toward a common goal and keep their focus on the game.

They also learn to recognize emotions, like when someone gets hurt or scores a goal, and react appropriately when they win or lose.

19. Productive Debate

A productive debate works well for older kids to learn how to manage emotions and work on positive expression, even in challenging situations. They learn how to have difficult conversations calmly, without turning them into an argument or trying to insult the other person.

People who can debate and listen to their opponent develop more of the skills needed to become leaders in the classroom and workplace.

20. Scavenger Hunts

During scavenger hunts, children work together to find objects or get a prize at the end of the activity. By working toward their goal, they learn teamwork, organization, and positive decision-making. They can choose to split up, move as a group, and collaborate to reach the end of the game.

They also get rewarded for cooperating. These activities help them with creative problem-solving abilities by making up clues for other players to solve.

What’s Next?

Using evidence-based social skills activities and games helps your child build social skills while doing something they enjoy. You can adapt any of these activities to something that engages your child and allows them to get creative with their socialization.

You can adapt any of these activities to something that engages your child and allows them to get creative with their socialization.

However, activities and games can only go so far. The Positive Action social skills curriculum is designed to work in tandem with activities like these and more to help your child identify their self-concept and shift this introspection to their social interactions. We feel social skills start within.

Explore our sample lessons for even more ways to encourage your child’s social-emotional learning, or contact us to find out how our program can improve your child’s social skills and have fun doing it today!

Social Skills

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

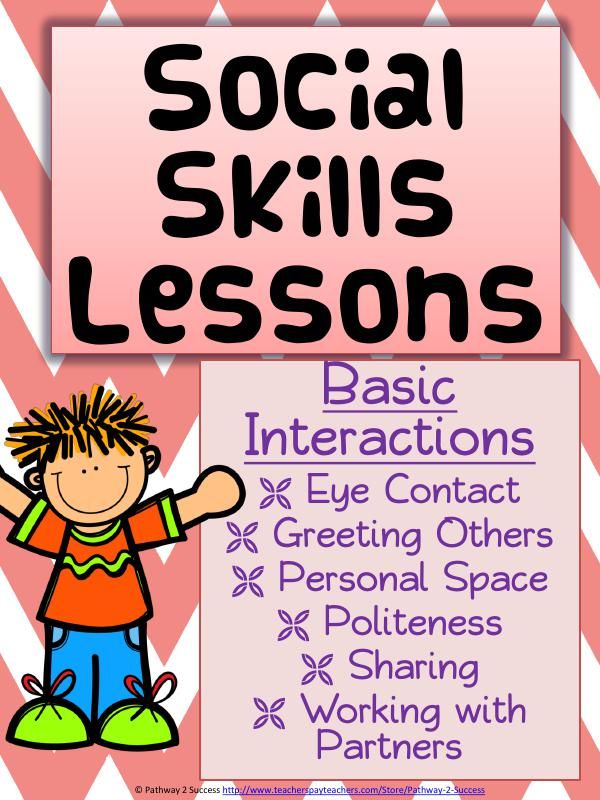

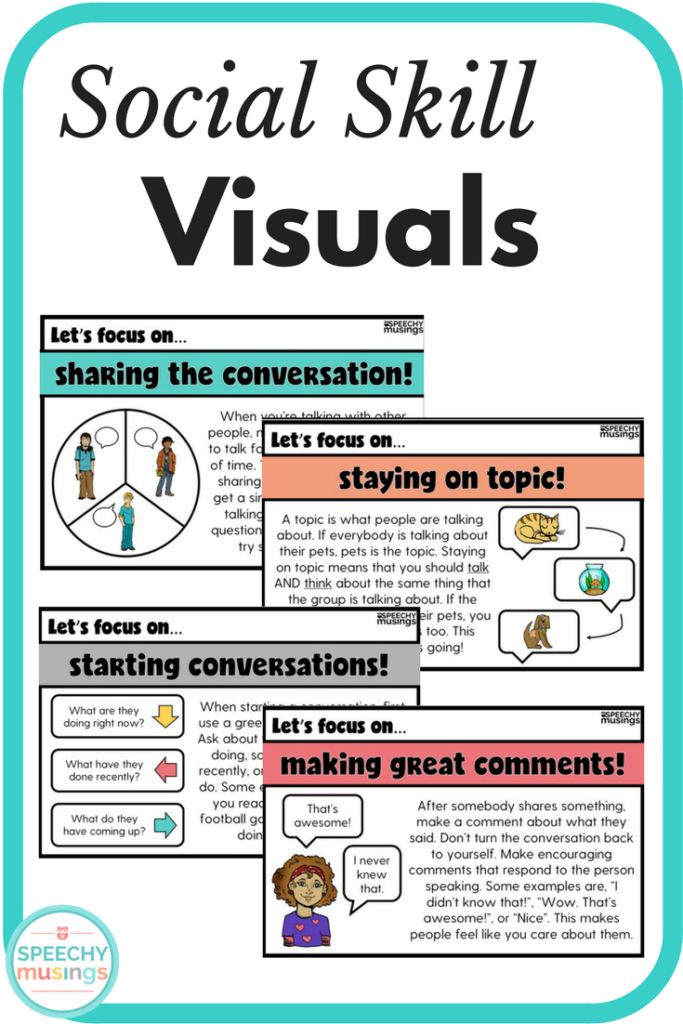

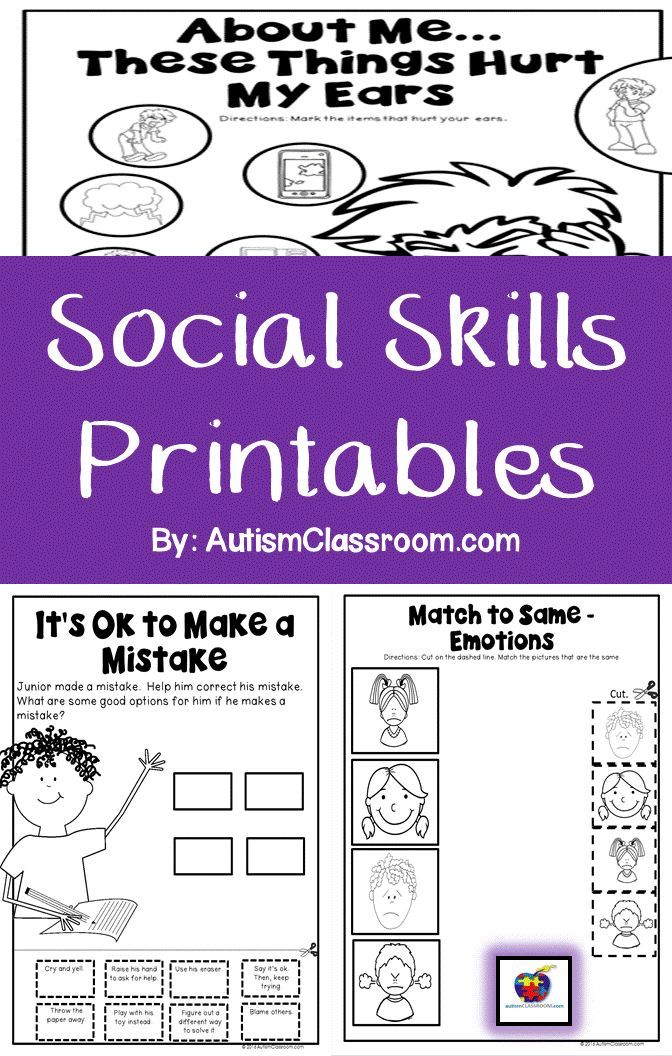

The Psychological Program "Social Skills" is designed to teach social behavior in a safe and friendly environment. At each group meeting, children are offered a role model and activities to practice skills. The approach is based on structured learning, a holistic teaching method that provides a framework for systematic learning of skills, similar to academic ones. The emphasis is on providing alternative behaviors to improve the effectiveness of social interactions. The curriculum is based on Michelle Garcia Winner's "Think Social: A Social Thinking Curriculum for School-Age Students" and includes structured activities to address real socialization issues.

The emphasis is on providing alternative behaviors to improve the effectiveness of social interactions. The curriculum is based on Michelle Garcia Winner's "Think Social: A Social Thinking Curriculum for School-Age Students" and includes structured activities to address real socialization issues.

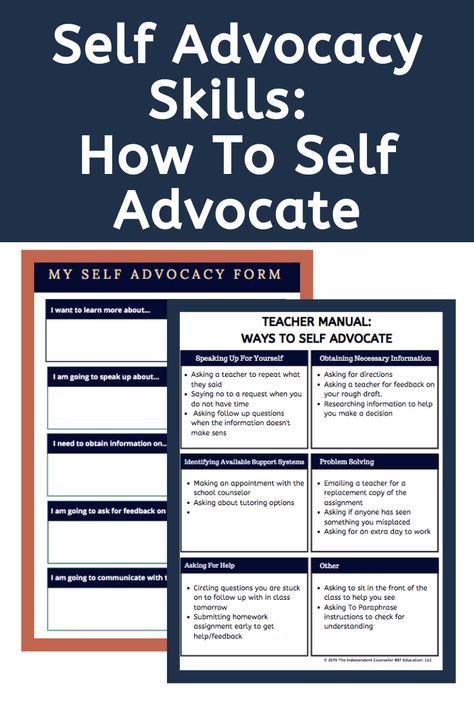

Our social skills training for teenagers has a wide range of benefits. Our social skills groups will help teenagers develop the following qualities:

1) Easier interaction with others

We understand how difficult it can be to interact with peers, especially during adolescence. Our social skills experts use proven techniques to help your child learn how to initiate and maintain conversations. Groups also help your teen read other people's reactions, body language, and attitudes.

2) A sense of belonging

We devote the necessary time and effort to match each client with a group that matches their personality. Our team provides a safe space for your teenager, where his peers understand and unconditionally accept his feelings and emotions. And also thanks to the skills of how to cope with emotions and stress on their own.

And also thanks to the skills of how to cope with emotions and stress on their own.

3) Boosting Self-Confidence

At our center, coaches and group members always encourage each other to use their social skills in real life, whether at home, at school or with friends. We always want your teen to be confident in their ability to socialize and make friends. And also how to deal with your emotions in contact with others and one on one with yourself.

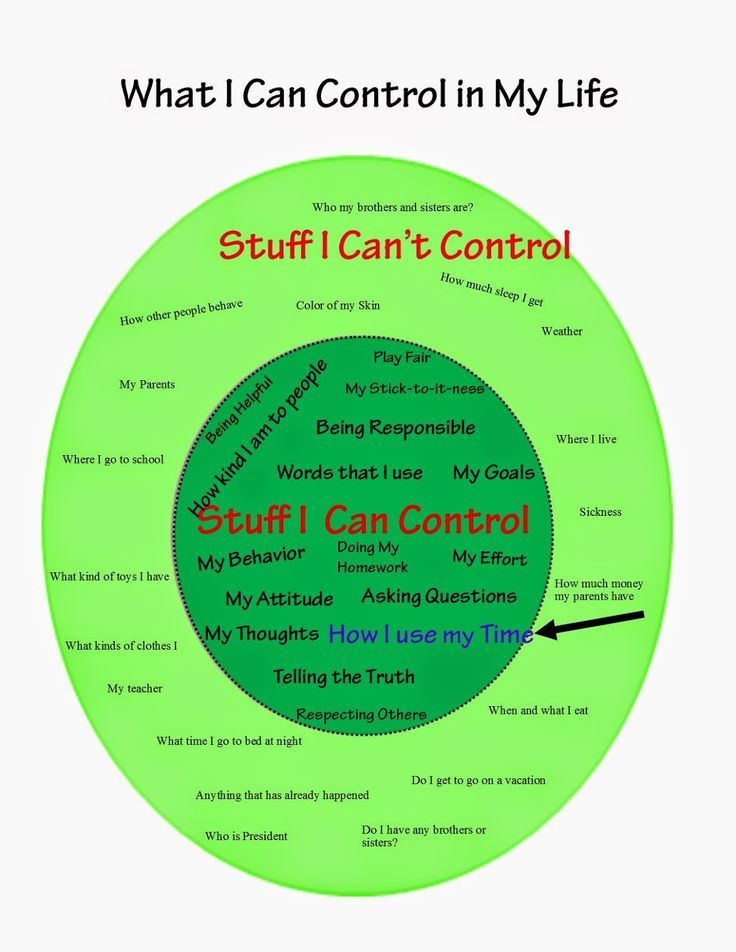

Group goals include :

- Making and supporting friends

- Dealing with environmental pressures (peer, teachers and family)

- Using self-control and following instructions.

- Think before you act

- Be able to listen and understand

- Accept rules and consequences

- Set goals

- Solve problems

- Work with feelings

- Acceptance

- Practice in real life situations

- Appropriate behavior modeling

- Communication and feedback

- Activities and games used to teach teamwork and build skills through collaborative activities

If you are interested, please contact your therapist at the Grigory Misyutin Psychological Center or the center administrator at

8 (906) 026-55-33 or leave a request and the curator of the program will contact you.

Social skills training • Mosaic

What is a good way to teach social skills, especially in the group?

I work with children with autism. I confidently teach them academic and everyday skills, but, unfortunately, not social ones. I need a simple and effective flexible learning method as I need to teach a variety of skills to children of different levels. Many of my students have intermediate or advanced language skills but find it difficult to make friends and maintain relationships. Since it is not possible to organize individual work with each student, something is needed that can be done in a group. Any suggestions?

Answered by Shanti Stockley, Master of Education (MEd), Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA), Licensed Behavior Analyst (LBA) Autism Treatment Association.

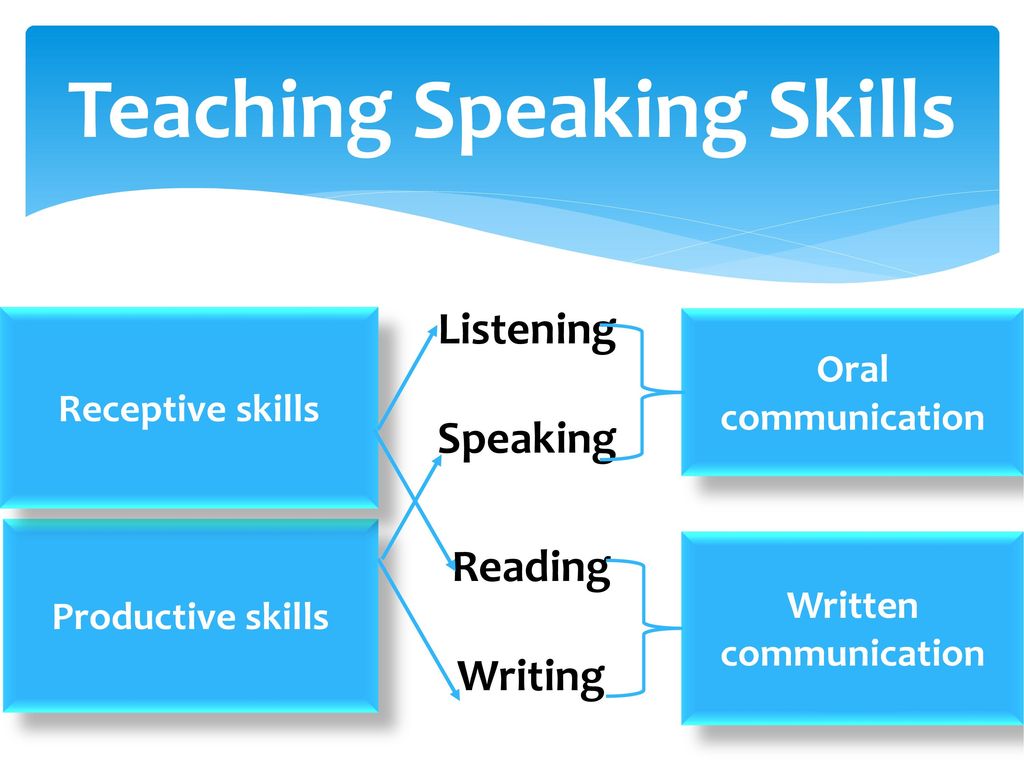

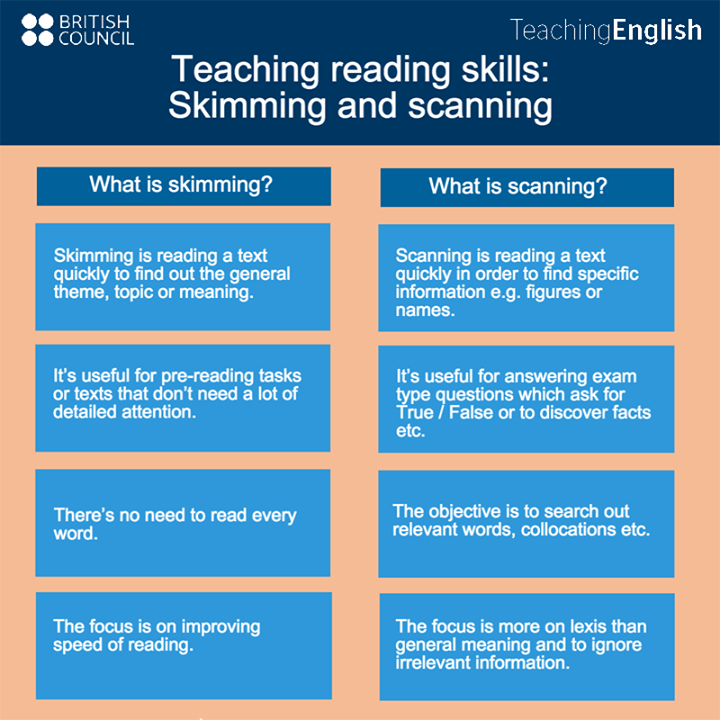

Although the amount of research available on social skills education is increasing, this question remains very common. It can be difficult for educators to find evidence-based curricula and strategies. One strategy that has proven effective in teaching social skills to children of different levels in groups is the Teaching Interaction Procedure (TIP). The learning interaction method is a 6-step process in which the educator names and defines the skill being learned, explains the need for its application, describes the steps necessary to perform it correctly, demonstrates this skill, conducts practical exercises with students in the form of a role-play, and also gives give them feedback and reinforcement. Over the past ten years, this procedure has been repeatedly studied, including its use in individual work with a child (for example, Leaf et al., 2009), in groups (e.g. Leaf, Dotson, Oppeneheim, Sheldon and Sherman, 2010) and in schools (Tullis and Gallagher, 2016). In this issue of Clinical Corner, I will share how this method is commonly used, demonstrate a variation of the procedure that may help you, compare it to other teaching methods, and tell you where to find more information.

One strategy that has proven effective in teaching social skills to children of different levels in groups is the Teaching Interaction Procedure (TIP). The learning interaction method is a 6-step process in which the educator names and defines the skill being learned, explains the need for its application, describes the steps necessary to perform it correctly, demonstrates this skill, conducts practical exercises with students in the form of a role-play, and also gives give them feedback and reinforcement. Over the past ten years, this procedure has been repeatedly studied, including its use in individual work with a child (for example, Leaf et al., 2009), in groups (e.g. Leaf, Dotson, Oppeneheim, Sheldon and Sherman, 2010) and in schools (Tullis and Gallagher, 2016). In this issue of Clinical Corner, I will share how this method is commonly used, demonstrate a variation of the procedure that may help you, compare it to other teaching methods, and tell you where to find more information.

Before you start teaching social skills, first select the skills you will teach and develop an appropriate motivation system. While identifying the skills to learn is out of the scope of this article, it is perhaps more important than how you teach it! Teaching essential skills (that are appropriate to the student's level on the assessment, meaningful to the child and their environment, and open up new opportunities for them) is both extremely important and difficult at the same time. The process of learning in a group increases the complexity. For guidance on setting goals and assessing social skills, see Chapters 1 and 5 of Teaching Social Skills to People with Autism: Best Practices for Individual Intervention (Bondy and Weiss, 2013) by clicking here. Once the skills are chosen, set up a motivation system so that the children put in the best effort in practice. To do this, it is necessary to identify one or more favorite activities or subjects that each child would like to receive. Next, come up with a system of points or tokens that he can exchange for the selected reward. You can see how to do this effectively in the ASAT Intervention Summary. Once you've completed these steps, you're ready to start learning.

Next, come up with a system of points or tokens that he can exchange for the selected reward. You can see how to do this effectively in the ASAT Intervention Summary. Once you've completed these steps, you're ready to start learning.

The following is a more detailed description of how the six stages of the learning interaction procedure are carried out in practice. Examples are given that include teaching in the format of individual and group lessons for children of primary school and adolescence, both with an average and a higher level of social skills.

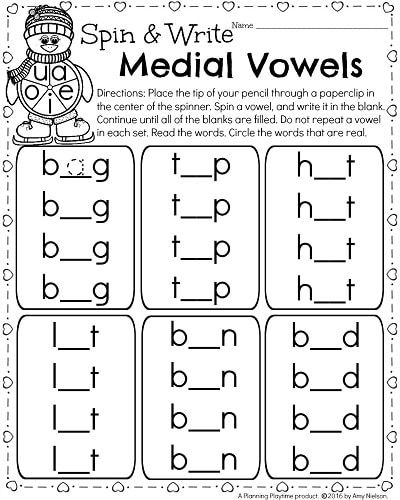

Step 1. Skill name and definition : Tell students what they will be learning. Give the skill a name that is descriptive and appropriate for the child's developmental level. Ask each child to tell what this skill is. It is very important that students actively respond. Therefore, each stage should include opportunities for responses. Don't let the procedure turn into a lecture!

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Primary school students Individually | “Susie, we're going to learn how to say hello to our friends. What are we going to do today?" What are we going to do today?" | "Say hello to friends!" |

| Teens In the classroom | Hello children! Today we will practice changing the topic of conversation. John, what are we going to learn today?” | "We will learn to change the subject of conversation." |

Stage 2 Skill and Prompt Need: Explain to the children why they need the skill they are learning. The explanation should contain natural, significant for students, consequences of applying the skill. You could give an example and ask each child to give their own explanation. Describe the environment or landmarks that indicate the right moment to use this skill. Ask each student to share when they will use this skill.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Primary school students Individually | “If you say hello to your friends, they will want to play with you. Why say hello to friends? Why say hello to friends? | "For them to play with me." |

| Primary school students Individually | “You can say hello to Bobby when he comes to the water play table. Who will you say hello to? | "Bobby". |

| Teens in the classroom | “It is important to be able to change the topic of conversation correctly so that friends do not get tired of talking about the same thing and leave. Sarah, why do you think we need to change the subject?” | "So that my friends can also talk about whatever they want." |

| Teens in the classroom | “For example, I need to use this skill when I talk to my daughter about school so that she can talk about other topics that she is interested in. Jordan, when do you need to change the subject?" | "When I talk about myself for a long time." |

Stage 3 - Divide the skill into steps .

Before learning, divide a skill into a sequence of steps (usually 2 to 5). The number of steps should match the number of important elements of the skill being learned and be easy to remember. Tell the students about each step and ask them to say it in order.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Primary school students Individually | “When you say “hello” to a friend, you need to look at her, smile and say “hello” in a friendly voice. How do you say hello to your girlfriend? | "I'll look at her... I'll say hello in a friendly voice." |

| Teens In the classroom | “This is a good way to change the subject. First, wait for a pause. Second, use a transition phrase to link the old topic to the new one. A passphrase is a phrase like “By the way, oh…” or “That reminds me of…”, etc. Third, suggest a new topic. Fourth, observe your interlocutor to see if he is interested in a new topic. Who can remember all four steps when changing the subject? John, try it” Who can remember all four steps when changing the subject? John, try it” | “Um…wait for a pause, then say a passphrase. Start talking about a new topic and see what others are interested in” |

Step 4 - Skill Demonstration : Demonstrate the skill you are teaching.

Teaching interactions often (but not always) show both right and wrong behavior so that children learn to distinguish between right and wrong responses. First, demonstrate the skill incorrectly by doing only some of the steps. Ask students to answer if everything was done correctly. Then ask the children to tell what went wrong and how to fix it. Show the correct behavior. You can demonstrate the skill with another adult, a specially trained peer, one of the students and, in some cases (depending on the skill itself), on your own.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Primary school students Individually | “Look how I say hello to my friend Mrs. Smith. Tell me if I'm doing it right." Look at Mrs Smith with a serious expression and say hello. Smith. Tell me if I'm doing it right." Look at Mrs Smith with a serious expression and say hello. “Did I do everything right? What did I do wrong? | “No! You didn't smile and your voice wasn't sweet." |

| Primary school students Individually | “That's right! How can I do it right?" | "You should smile and say in a sweet voice like this:" Hello! |

| Primary school students Individually | “Well done! I'll try again. Tell me if I'm doing the right thing…” | |

| Teenagers Classroom | “Look how I change the subject. And tell me if I followed all four steps correctly. Sarah, you will be my partner. Let's talk about our favorite music and I'll change the subject." | Sarah: "Who is your favorite singer?" |

| Teenagers Classroom | Teacher: “I like the Beatles. And you?" And you?" | Sarah: "I like Taylor Swift." |

| Teenagers Classroom | Teacher: “Yesterday, while jogging, I lost my favorite headphones…” “Guys, how did I manage? On the count of three, thumbs up if I've completed all the steps and thumbs down if I haven't. One two Three!" | Pupils show thumbs down. |

| Teenagers Classroom | “Everyone thinks that she didn't do it. Right! What did I do wrong and how can I fix it? | "You didn't use a passphrase." |

| Teenagers Classroom | “That's right! I missed the passphrase. Who can invent it? | “Speaking of listening to music…” |

Stage 5 - Role play: Give each student the opportunity to demonstrate the skill in a role play with you. Look for clues and hints that trigger the application of the skill being learned. Give feedback after the skill has been demonstrated by the students. Clarify what was done right and what mistakes were made. If there were mistakes, ask the children to try again. If mistakes are made the second time, it may be necessary to use a hint during the role-play to increase the chances of the children being successful on the third attempt.

Give feedback after the skill has been demonstrated by the students. Clarify what was done right and what mistakes were made. If there were mistakes, ask the children to try again. If mistakes are made the second time, it may be necessary to use a hint during the role-play to increase the chances of the children being successful on the third attempt.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Primary school students Individually | “When Mrs. Smith comes into the room, show me how you say hello to her. (Mrs Smith comes in) | Susie looks at her, smiles and says hello in a joyful voice. |

| Primary school students Individually | Well done, Susie! You looked at Mrs Smith and said hello to her in a friendly voice. | |

| Teenagers Classroom | Now it's your turn to show the group how to change the subject. John, you start. I will be your partner. We'll start talking about Pokémon and you'll change the subject" "When I was playing Pokémon the other day, I..." John, you start. I will be your partner. We'll start talking about Pokémon and you'll change the subject" "When I was playing Pokémon the other day, I..." | (interrupts) “Speaking of video games, you played a new game World of Warcraft ?” |

| Teenagers Classroom | With a pitiful look “No…” | “She's cool! What I like the most is the new equipment that I can use. There is one spell that can be cast…” |

| Teenagers Classroom | “Let's stop there. John, you said a great transitional phrase "by the way, about video games" and started a new topic that is relevant to the question asked. But you did not wait for a pause in the conversation, and also did not follow my face. You did not notice that I was not interested in a new topic. Try again". Try again". |

Stage 6 - Feedback and Reinforcement: It is desirable that throughout the procedure the student receives reinforcement (usually praise along with some other prize) for correct answers, and in case of errors - corrective feedback. Before starting training, determine the child's preferences and objects that can be used as reinforcement. Token or point systems are effective for this purpose. During the lesson, children receive points or tokens for correct answers (Steps 1-4) and correct use of the skill during the role-play (Step 5). At the end of the lesson, the students exchange them for a reward. The order of issuing tokens can be as follows: for the correct performance of the skill on the first attempt, give two tokens, on the second - one token, in case of a correct answer using the hint on the third attempt - praise. This will happen at every stage of the learning interaction procedure, not just at the end of the

Below is another example of a learning interaction procedure, also used in group sessions with elementary school students. This example includes a feedback/rewards process (tokens are issued throughout the process).

This example includes a feedback/rewards process (tokens are issued throughout the process).

| Step | Teacher | Students |

| Step 1: Naming and defining the skill | “Today we will learn how to invite a friend to play a game. Guys, what are we going to learn to do? | (in unison) "Invite a friend to play a game!" |

| "That's right!" (give each student two tokens) | ||

| Step 2: Explain the need for the skill and environmental guidelines | “Why is it important to invite friends to play? Olive, what do you think?" | Olive : « I not know ". |

| “Try to answer. Why would you want to invite a friend to play together?” | Olive: "That'll be more fun. " " | |

| "Yes, it's more fun!" (give Oliver 1 token for the correct answer on the second try, ask the rest of the children until each of them gives their own explanation). “When will you invite a friend to play? For example, you can invite a friend who is watching the game. Levi, when are you going to invite a friend to play together?” | Levy: "I'm going to invite Kayden to play Square because I know he likes the game." | |

| “Great idea! I'm sure Cayden will be very happy!" (give Levi two tokens for the correct answer on the first try, ask the rest of the children) | ||

| Step 3: Skill division into steps | “You can invite a friend to play in the following way: first, find a person who might be interested. Choose a friend who is not currently playing something else. Second, approach him in a friendly way. It means to come up and smile. Third, tell what you are doing and ask if he would like to join. Fourth, if the friend agreed, tell them exactly how they can join the game, for example, say: "You can be on my team" or "You can draw with this marker." You had to memorize many steps. Let's try to say them all. Calvin, you begin." Third, tell what you are doing and ask if he would like to join. Fourth, if the friend agreed, tell them exactly how they can join the game, for example, say: "You can be on my team" or "You can draw with this marker." You had to memorize many steps. Let's try to say them all. Calvin, you begin." | Calvin: "Find a friend to play with and ask him if he wants to." |

| “You named two steps out of four! The two steps you missed: approach in a friendly way, and then tell how you can join. | Calvin: “Okay. Find a friend to play with, ask him to join, and tell you how to join" . | |

| “Nice try. You named three steps out of four. Try again and I'll help you remember when to approach in a friendly way." | Calvin: "Find a buddy to play with..." | |

| Interrupts the student with the words "and come..." | “And approach in a friendly way. Ask to play together and tell how you can join. Ask to play together and tell how you can join. | |

| “You named all the steps! Great!" (do not give tokens because the child needed a hint to get the correct answer. Continue with the next student).” | ||

| Step 4: Skill Demonstration | “Now I'll show you how to invite someone to play. I can do everything right, or I can make a mistake. Look carefully and tell me if I did the right thing or not. (Demonstrate a skill with a colleague who is "passionate about playing another game." Follow all steps except the first one: "Find a buddy who might want to play together.") | |

| “So, tell me, did I do everything right? What should have been done differently if a mistake was made? Olive?" | Olive: “Wrong. Mrs Smith was busy. You should have asked the other person." | |

Great, Olive! (give Olive 2 tokens, and give each student a chance to answer). | ||

| Pitch 5: Role play | “Now it's your turn to invite a friend to play the game. Levi, you start playing Uno with the mission c Smith." (Silently watching the game with interest - and this is a hint that you can be invited to the game). | Levi sees you watching, comes up to you with a smile and asks if you want to play. When you say yes, he returns to the game. |

| “Well done, Levi! You did four steps correctly, but you forgot the last one. I needed help getting started. You could do it this way: give me some cards or tell me you're almost done and give me the cards in the next round." | Levi repeats the role play again, doing everything right. | |

| “Great! You followed all the steps correctly." (Give Levi one token and train the rest of the students) | ||

| Step 6: Feedback and Reinforcement | “You all did great! You've learned how to invite your friends to play the game! Be sure to practice again today during recess. Count your tokens and raise your hand if you want to exchange them." Count your tokens and raise your hand if you want to exchange them." |

Follow these procedures until each student has mastered the skill being taught. This method can be adapted in future lessons. For example, after one or two lessons, ask students to independently determine the skill and explain its necessity. It usually takes 3 to 6 sessions to master a new skill. This parameter will vary depending on the level of development of students.

How do you know if a child has mastered a skill? One of the signs is the correct use of it the first time during a role-playing game. Even better, try without warning: create a situation outside of the group session in which it would be appropriate to apply this skill, and observe the actions of the child. In the case of the example of learning to change the subject, talk to a student at any time during the day and suddenly pretend to be bored. See if he changes the subject. In the case of the example of learning to say "hello", when the child is playing alone, suddenly come and sit next to him to see if he says hello.

Each student may progress at a different pace. It is important to make sure that each child gets enough practice. However, if the skill is not mastered by the student despite sufficient time to practice it, pay attention to the following points:

- Is the learning interaction procedure applied correctly? Based on the steps listed in the article (or the links at the end of the article), you need to make a checklist and make sure that the teacher consistently completes all the steps of the procedure.

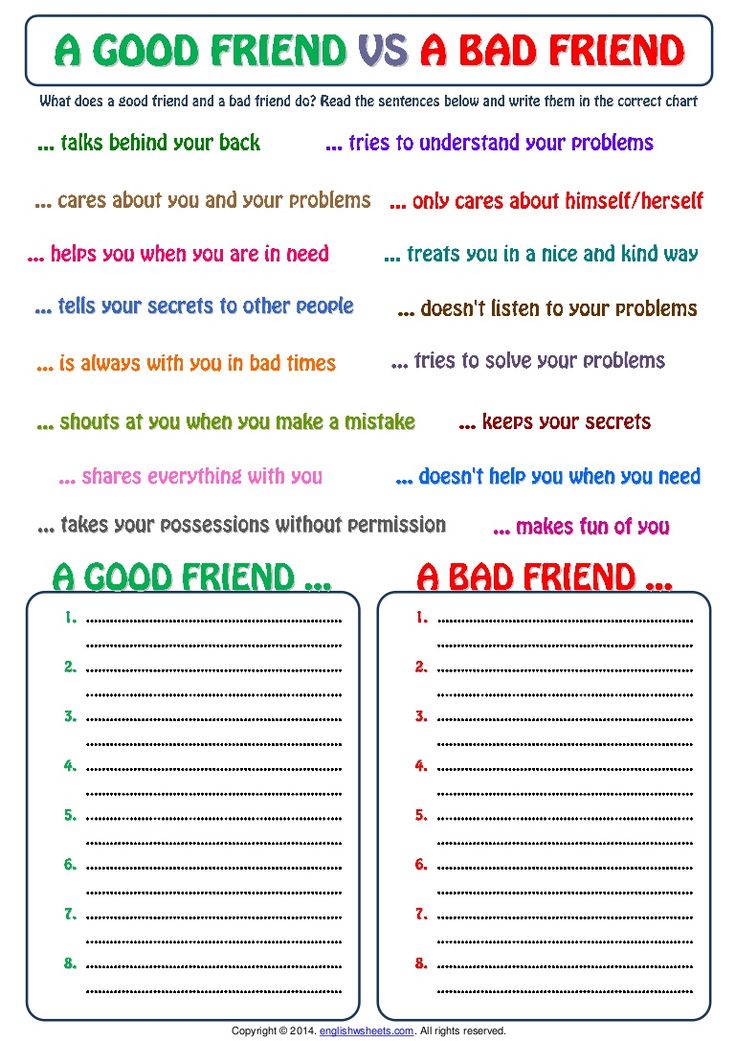

- Are there steps (skill items) that require clearer description or detailed training? For example, the "decide if this person would be a good friend" step as part of the making friends skill would likely require a definition explaining who would make a good friend. It will also take more time to practice distinguishing between examples that correspond to the behavior of good and bad friends.

- Do students have the necessary prerequisite skills? As a rule, to get a good result, the child needs well-mastered basic speech skills (for example, using sentences in communication), and it may also require pre-learning certain steps (as in the previous example).

- Are students motivated enough to try hard? If not, pay attention to the reinforcement system. Make sure to use it consistently. Replace some rewards with more interesting ones. You can choose the most desired encouragement, which will be used only in lessons using the learning interaction method.

- The student does not apply the skill learned in the role play in real life. Read on.

Several steps have been added to one of the potentially successful variations of the procedure to allow generalization of the skill. That is, the child will use the learned skill not only in role play with the teacher, but also in real life situations (Kassardjian & Taubman, 2013). You can see if generalization is happening by observing the student in other settings and seeing if the skill is applied. You can also ask your child's parents if they use the skill outside of school. In order to use this option, minor changes should be made to Stage 5 and practice in real life conditions (generalization phases) should be added:

Step 5 - Role Play: Use a variety of realistic scenarios to role play. Use as many potential situations as possible, especially in which the child does not demonstrate this skill. Organize role-play with other children in such a way that they have the opportunity to interact with each other on a daily basis. For classes, you should choose materials that are usually used in the daily life of children. The role-play should be conducted in places where the skill is really needed. In the case of the example of teaching children to “invite friends to play something”, a role-play can be organized in the playground using real games.

Use as many potential situations as possible, especially in which the child does not demonstrate this skill. Organize role-play with other children in such a way that they have the opportunity to interact with each other on a daily basis. For classes, you should choose materials that are usually used in the daily life of children. The role-play should be conducted in places where the skill is really needed. In the case of the example of teaching children to “invite friends to play something”, a role-play can be organized in the playground using real games.

Generalization. Phase 1 - Reminder, Praise, Reward: After the skill has been mastered by students at the role-play level, situations should be created in which the new skill needs to be applied in a real life setting. For example, if this is one of the play skills, you can use recess or games during class. At the beginning of the exercise, remind the students to use the new skills. If the children are doing their actions correctly, praise and reinforce this.

Generalization. Phase 2 - Praise and Reward: Do not tell students to use the skill in a natural setting (same as in Phase 1). In case of correct performance, praise them and give encouragement.

Generalization. Phase 3 - Praise: Do not tell students to use the skill in a natural setting (same as in Phase 1). If performed correctly, only praise is used.

Generalization. Phase 4 - Autonomy: Create situations to demonstrate a skill without reminders or additional consequences. Now the students have to do everything in the natural environment on their own! Congratulations!

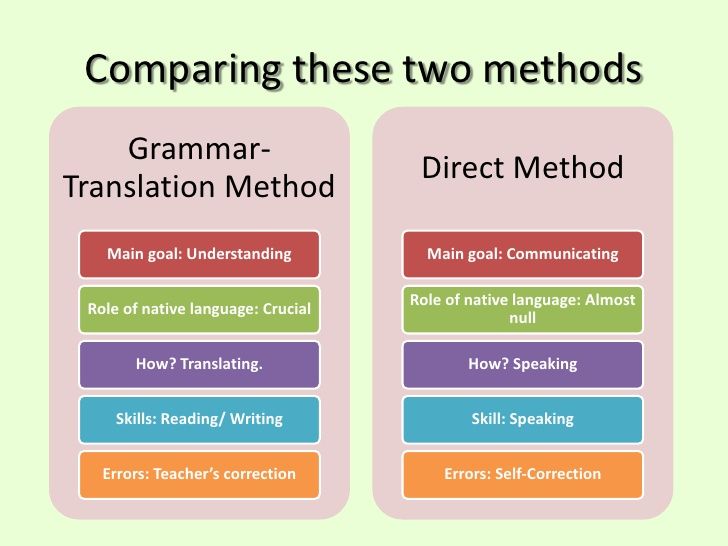

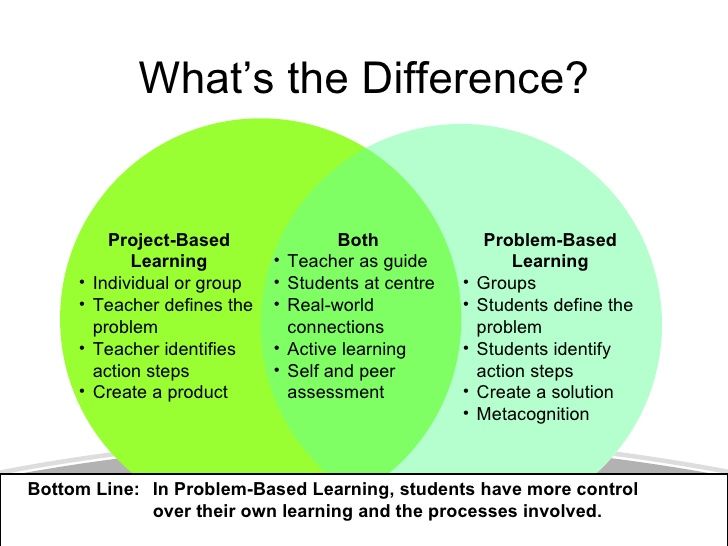

In addition to the learning interaction method, there are other options for teaching social skills. And although there are many more, let's compare this method with "social stories" (Social Stories) and behavior skills training (Behavioral Skills Training).

Social stories ( Social Stories ): " Social stories" are stories, individual for each child, from which he learns information on social topics. At the moment, on the official website about this method, 10 signs are given, according to which "social history" can be considered as such. Social stories are a commonly used intervention method. Therefore, the researchers compared it with the learning interaction method to find out which one is more effective. In the first comparative study (Leaf et al., 2012), six children were taught six different skills, three skills using the learning interaction method and three others using the social stories method. According to the results obtained, using the learning interaction method, children mastered 18 skills out of 18 that they were taught. At the same time, students mastered only 4 of the 18 skills that they were taught with the help of "social stories". Although the comparison was made for applying both methods through individual learning, it was also replicated in a group learning setting (Kassardjian et al., 2014). In this study, the authors concluded that the learning interaction procedure was effective for all children, while the application of the "social stories" method did not lead to any improvements.

At the moment, on the official website about this method, 10 signs are given, according to which "social history" can be considered as such. Social stories are a commonly used intervention method. Therefore, the researchers compared it with the learning interaction method to find out which one is more effective. In the first comparative study (Leaf et al., 2012), six children were taught six different skills, three skills using the learning interaction method and three others using the social stories method. According to the results obtained, using the learning interaction method, children mastered 18 skills out of 18 that they were taught. At the same time, students mastered only 4 of the 18 skills that they were taught with the help of "social stories". Although the comparison was made for applying both methods through individual learning, it was also replicated in a group learning setting (Kassardjian et al., 2014). In this study, the authors concluded that the learning interaction procedure was effective for all children, while the application of the "social stories" method did not lead to any improvements. Therefore, they recommended using the method of learning interaction.

Therefore, they recommended using the method of learning interaction.

Behavioral Skills Training Behavioral Skills Behavioral Skills Behavior skills training has four components: instruction, skill demonstration, skill practice, and feedback. The main difference between the two methods is that the BST does not provide an explanation for the need to apply the skill. Another difference: in the case of learning interaction method, both correct and incorrect skill models are often shown in order to develop discernment skill. This stage implementation has been called Cool/Not Cool and has been shown to be effective on its own (Au et al., 2016). In the case of BST, only the correct response model is shown. After reviewing studies on behavioral skills training and learning interactions involving people with autism (Leaf et al., 2015), the authors of the article concluded that both methods have a sufficient evidence base and are effective.

If you are going to use the learning interaction method for teaching social skills, I recommend that you read the study guide with a detailed curriculum “Connected! Learning programs. Socialization of People with Autism Using Applied Behavioral Analysis” (Taubman M., Leaf R., MakEken J., edition in Russian: IP Tolkachev, 2018). The articles I referenced in this paper also provide examples of how the learning interaction method can be applied.

References:

- Au, A., Mountjoy, T., Leaf, J. B., Leaf, R., Taubman, M., McEachin, J., & Tsuji, K. (2016). Teaching social behavior to individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder using the cool versus not cool procedure in a small group instructional format. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 41(2), 115–124. doi:10.3109/13668250.2016.1149799

- Bondy, A., & Weiss, M. J. (2013). Teaching social skills to people with autism: Best practices in individualizing interventions (1st ed.

). Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House.

). Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House. - Online download link for some chapters: https://pecsusa.com/downloadable-books/

- Kassardjian, A., Leaf, J. B., Ravid, D., Leaf, J. A., Alcalay, A., Dale, S., … Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L. (2014). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories: A replication study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(9), 2329–2340. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2103-0

- Kassardjian, A., & Taubman, M. (2013). Utilizing teaching interactions to facilitate social skills in the natural environment. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48(2), 245–257.

- Leaf, J. B., Dotson, W. H., Oppeneheim, M. L., Sheldon, J. B., & Sherman, J. A. (2010). The effectiveness of a group teaching interaction procedure for teaching social skills to young children with a pervasive developmental disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 186–198. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.003

- Leaf, J. B., Oppenheim-Leaf, M.

L., Call, N. A., Sheldon, J. B., Sherman, J. A., Taubman, M., ... Leaf, R. (2012). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories for people with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(2), 281–298. doi:10.1901/jaba.2012.45-281

L., Call, N. A., Sheldon, J. B., Sherman, J. A., Taubman, M., ... Leaf, R. (2012). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories for people with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(2), 281–298. doi:10.1901/jaba.2012.45-281 - Leaf, J. B., Taubman, M., Bloomfield, S., Palos-Rafuse, L., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., & Oppenheim, M. L. (2009). Increasing social skills and pro-social behavior for three children diagnosed with autism through the use of a teaching package. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 275–289. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2008.07.003

- Leaf, J. B., Townley-Cochran, D., Taubman, M., Cihon, J. H., Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L., Kassardjian, A., … Pentz, T. G. (2015). The Teaching Interaction Procedure and behavioral skills training for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a review and commentary. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(4), 402–413. doi:10.1007/s40489-015-0060-y

- Taubman, M. T., Leaf, R. B.

Learn more