Teaching someone to read

9 Fun and Easy Tips

With the abundance of information out there, it can seem like there is no clear answer about how to teach a child to read. As a busy parent, you may not have time to wade through all of the conflicting opinions.

That’s why we’re here to help! There are some key elements when it comes to teaching kids to read, so we’ve rounded up nine effective tips to help you boost your child’s reading skills and confidence.

These tips are simple, fit into your lifestyle, and help build foundational reading skills while having fun!

Tips For How To Teach A Child To Read

1) Focus On Letter Sounds Over Letter Names

We used to learn that “b” stands for “ball.” But when you say the word ball, it sounds different than saying the letter B on its own. That can be a strange concept for a young child to wrap their head around!

Instead of focusing on letter names, we recommend teaching them the sounds associated with each letter of the alphabet. For example, you could explain that B makes the /b/ sound (pronounced just like it sounds when you say the word ball aloud).

Once they firmly establish a link between a handful of letters and their sounds, children can begin to sound out short words. Knowing the sounds for B, T, and A allows a child to sound out both bat and tab.

As the number of links between letters and sounds grows, so will the number of words your child can sound out!

Now, does this mean that if your child already began learning by matching formal alphabet letter names with words, they won’t learn to match sounds and letters or learn how to read? Of course not!

We simply recommend this process as a learning method that can help some kids with the jump from letter sounds to words.

2) Begin With Uppercase Letters

Practicing how to make letters is way easier when they all look unique! This is why we teach uppercase letters to children who aren’t in formal schooling yet.

Even though lowercase letters are the most common format for letters (if you open a book at any page, the majority of the letters will be lowercase), uppercase letters are easier to distinguish from one another and, therefore, easier to identify.

Think about it –– “b” and “d” look an awful lot alike! But “B” and “D” are much easier to distinguish. Starting with uppercase letters, then, will help your child to grasp the basics of letter identification and, subsequently, reading.

To help your child learn uppercase letters, we find that engaging their sense of physical touch can be especially useful. If you want to try this, you might consider buying textured paper, like sandpaper, and cutting out the shapes of uppercase letters.

Ask your child to put their hands behind their back, and then place the letter in their hands. They can use their sense of touch to guess what letter they’re holding! You can play the same game with magnetic letters.

3) Incorporate Phonics

Research has demonstrated that kids with a strong background in phonics (the relationship between sounds and symbols) tend to become stronger readers in the long-run.

A phonetic approach to reading shows a child how to go letter by letter — sound by sound — blending the sounds as you go in order to read words that the child (or adult) has not yet memorized.

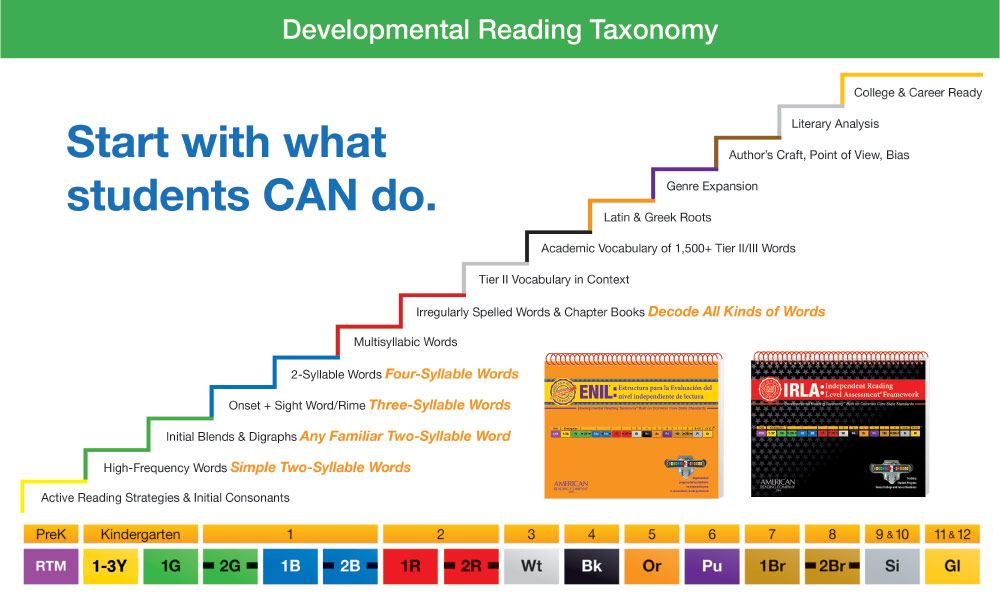

Once kids develop a level of automatization, they can sound out words almost instantly and only need to employ decoding with longer words. Phonics is best taught explicitly, sequentially, and systematically — which is the method HOMER uses.

If you’re looking for support helping your child learn phonics, our HOMER Learn & Grow app might be exactly what you need! With a proven reading pathway for your child, HOMER makes learning fun!

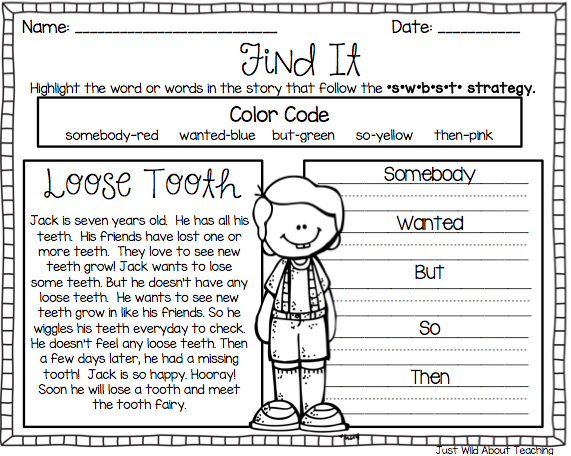

4) Balance Phonics And Sight Words

Sight words are also an important part of teaching your child how to read. These are common words that are usually not spelled the way they sound and can’t be decoded (sounded out).

Because we don’t want to undo the work your child has done to learn phonics, sight words should be memorized. But keep in mind that learning sight words can be challenging for many young children.

So, if you want to give your child a good start on their reading journey, it’s best to spend the majority of your time developing and reinforcing the information and skills needed to sound out words.

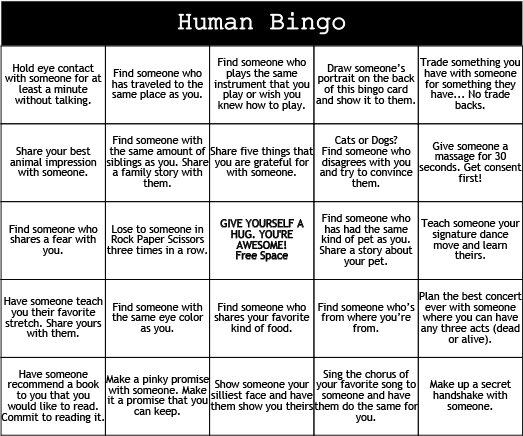

5) Talk A Lot

Even though talking is usually thought of as a speech-only skill, that’s not true. Your child is like a sponge. They’re absorbing everything, all the time, including the words you say (and the ones you wish they hadn’t heard)!

Talking with your child frequently and engaging their listening and storytelling skills can increase their vocabulary.

It can also help them form sentences, become familiar with new words and how they are used, as well as learn how to use context clues when someone is speaking about something they may not know a lot about.

All of these skills are extremely helpful for your child on their reading journey, and talking gives you both an opportunity to share and create moments you’ll treasure forever!

6) Keep It Light

Reading is about having fun and exploring the world (real and imaginary) through text, pictures, and illustrations. When it comes to reading, it’s better for your child to be relaxed and focused on what they’re learning than squeezing in a stressful session after a long day.

We’re about halfway through the list and want to give a gentle reminder that your child shouldn’t feel any pressure when it comes to reading — and neither should you!

Although consistency is always helpful, we recommend focusing on quality over quantity. Fifteen minutes might sound like a short amount of time, but studies have shown that 15 minutes a day of HOMER’s reading pathway can increase early reading scores by 74%!

It may also take some time to find out exactly what will keep your child interested and engaged in learning. That’s OK! If it’s not fun, lighthearted, and enjoyable for you and your child, then shake it off and try something new.

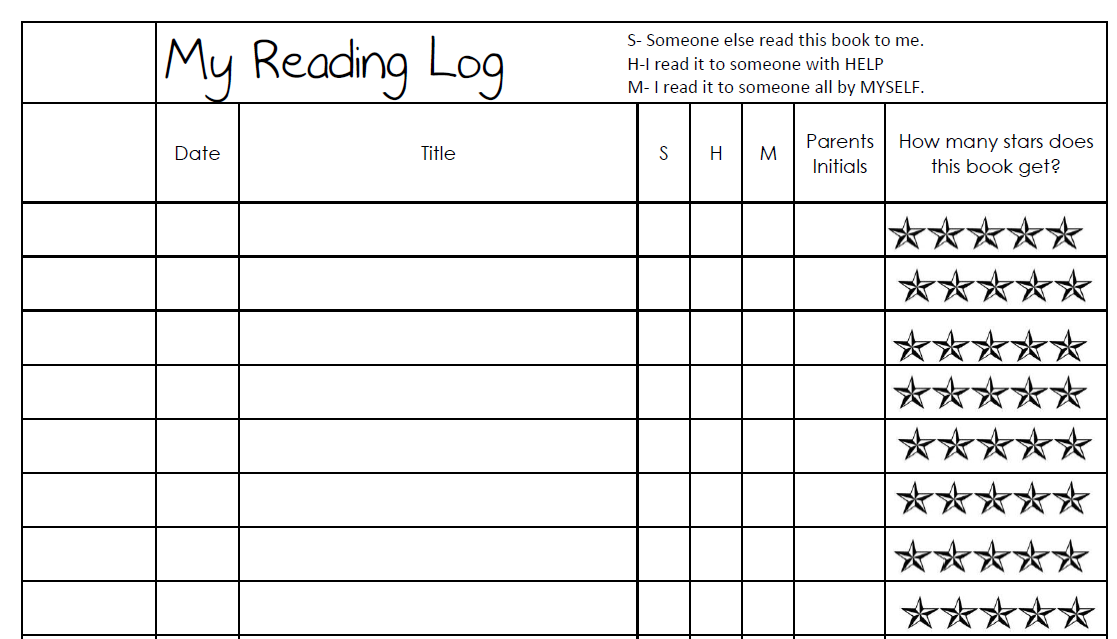

7) Practice Shared Reading

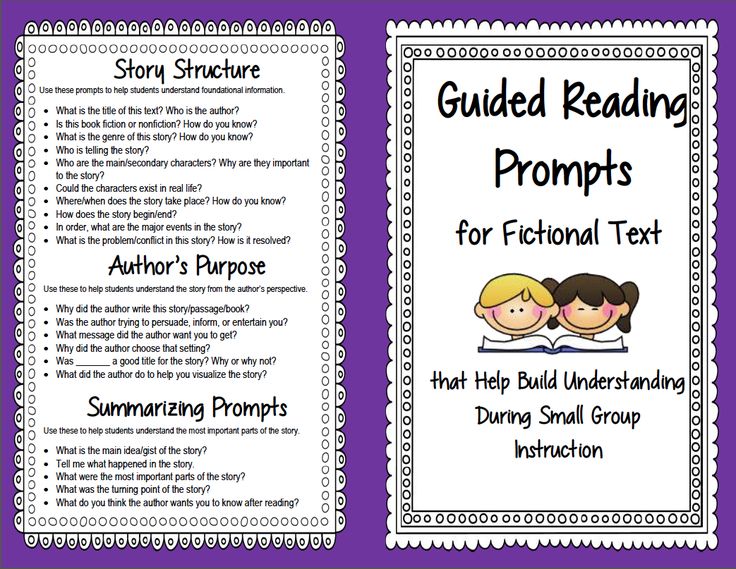

While you read with your child, consider asking them to repeat words or sentences back to you every now and then while you follow along with your finger.

There’s no need to stop your reading time completely if your child struggles with a particular word. An encouraging reminder of what the word means or how it’s pronounced is plenty!

Another option is to split reading aloud time with your child. For emerging readers, you can read one line and then ask them to read the next. For older children, reading one page and letting them read the next page is beneficial.

For emerging readers, you can read one line and then ask them to read the next. For older children, reading one page and letting them read the next page is beneficial.

Doing this helps your child feel capable and confident, which is important for encouraging them to read well and consistently!

This technique also gets your child more acquainted with the natural flow of reading. While they look at the pictures and listen happily to the story, they’ll begin to focus on the words they are reading and engage more with the book in front of them.

Rereading books can also be helpful. It allows children to develop a deeper understanding of the words in a text, make familiar words into “known” words that are then incorporated into their vocabulary, and form a connection with the story.

We wholeheartedly recommend rereading!

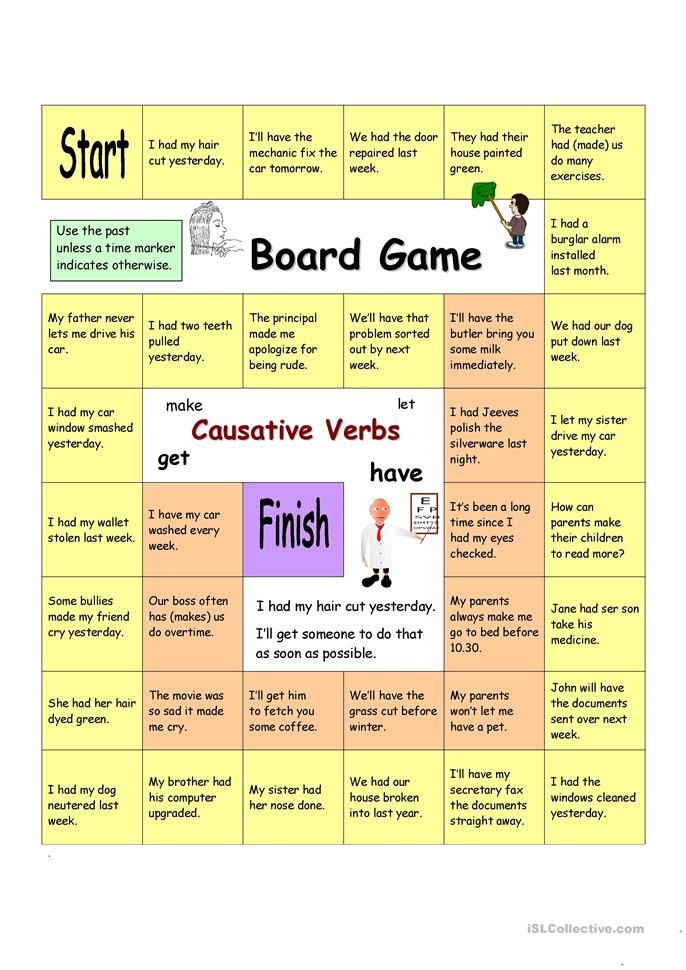

8) Play Word Games

Getting your child involved in reading doesn’t have to be about just books. Word games can be a great way to engage your child’s skills without reading a whole story at once.

One of our favorite reading games only requires a stack of Post-It notes and a bunched-up sock. For this activity, write sight words or words your child can sound out onto separate Post-It notes. Then stick the notes to the wall.

Your child can then stand in front of the Post-Its with the bunched-up sock in their hands. You say one of the words and your child throws the sock-ball at the Post-It note that matches!

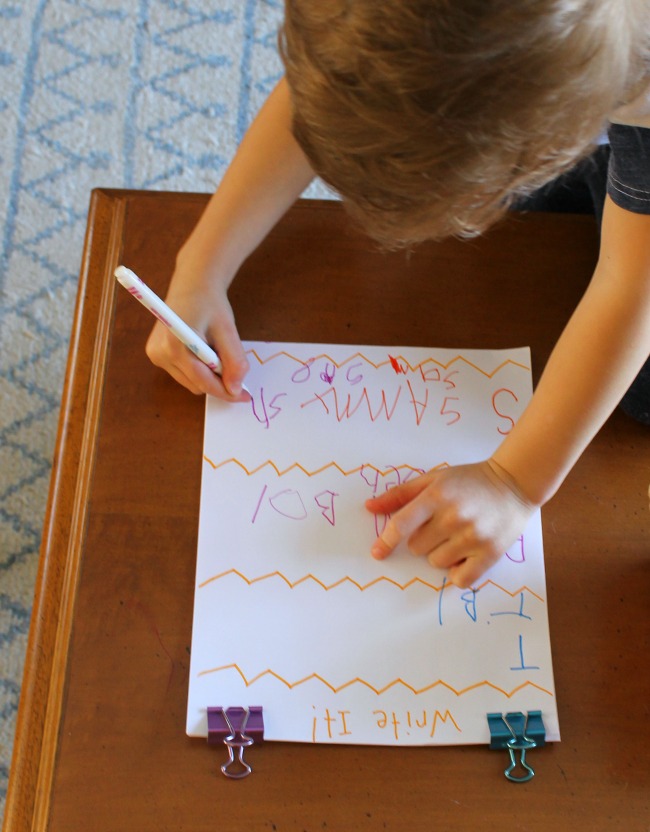

9) Read With Unconventional Materials

In the same way that word games can help your child learn how to read, so can encouraging your child to read without actually using books!

If you’re interested in doing this, consider using PlayDoh, clay, paint, or indoor-safe sand to form and shape letters or words.

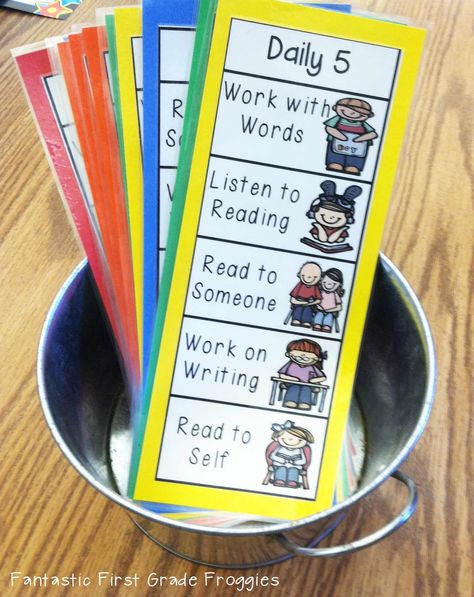

Another option is to fill a large pot with magnetic letters. For emerging learners, suggest that they pull a letter from the pot and try to name the sound it makes. For slightly older learners, see if they can name a word that begins with the same sound, or grab a collection of letters that come together to form a word.

As your child becomes more proficient, you can scale these activities to make them a little more advanced. And remember to have fun with it!

Reading Comes With Time And Practice

Overall, we want to leave you with this: there is no single answer to how to teach a child to read. What works for your neighbor’s child may not work for yours –– and that’s perfectly OK!

Patience, practicing a little every day, and emphasizing activities that let your child enjoy reading are the things we encourage most. Reading is about fun, exploration, and learning!

And if you ever need a bit of support, we’re here for you! At HOMER, we’re your learning partner. Start your child’s reading journey with confidence with our personalized program plus expert tips and learning resources.

Author

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger Report

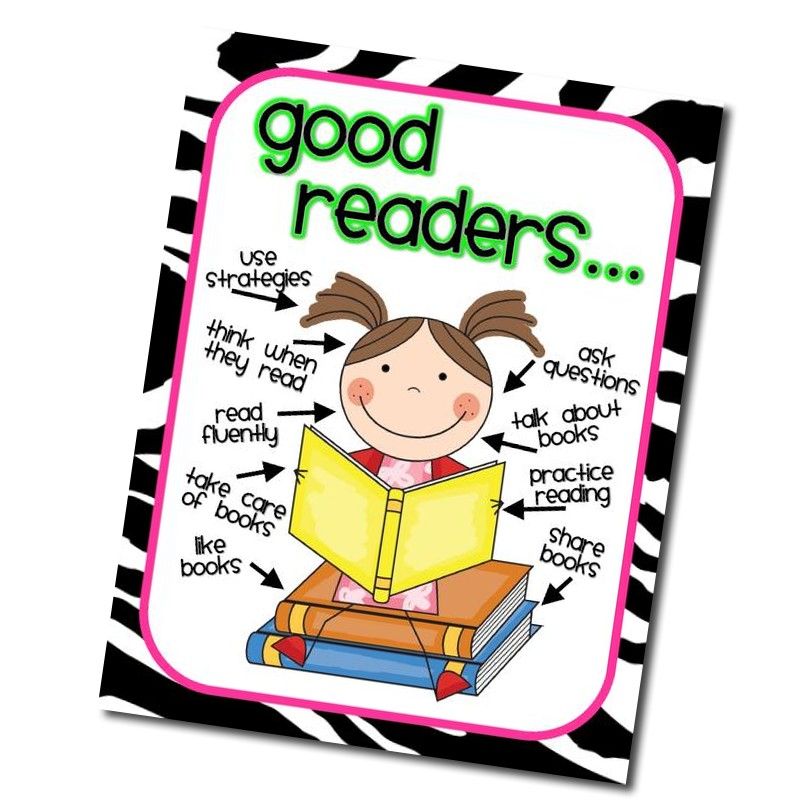

Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

Reading Matters

The Hechinger Report has been covering reading for over a decade, as debates about how to teach it have intensified. Check in with us for the latest in reading research.

Check in with us for the latest in reading research.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

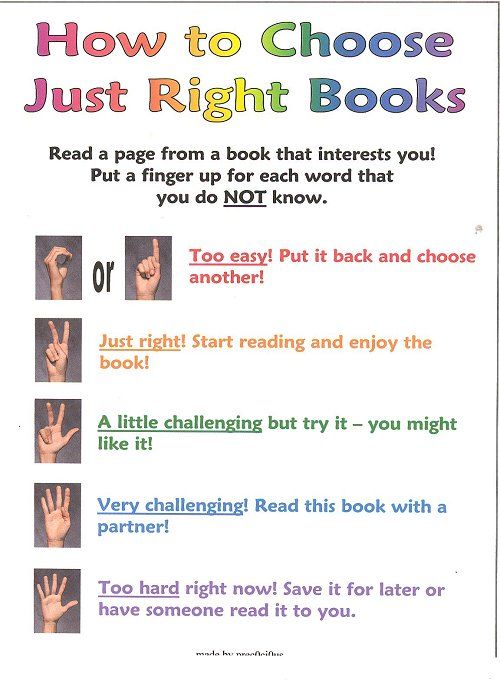

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

15 ways to get your child excited about reading

At what age should a child start reading? How not to turn reading into a tedious task, but, on the contrary, to show that a good book is a source of real pleasure? This is an excerpt from the best-selling journalist Jason Boog "Born to Read: How to make a child friends with a book" ("Alpina. Children").

1. Read together . Together with your child, get acquainted with a book, computer application, electronic or audio book - any carrier of a literary text. Scientists call such activities joint play activities. A child should not spend too much time alone fussing with a digital device. You should definitely play and read together every day.

You should definitely play and read together every day.

How to start communication : « Shall we read together? Show me how to cook something with this app" .

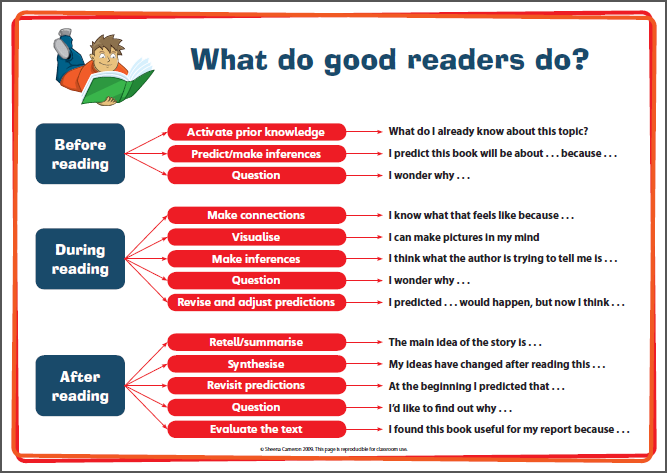

2. Ask as many questions as possible. Questions are the basis of interactive reading, and even a child who has not yet learned to speak can ask them. Don't forget to ask your child questions before, during and after reading.

How to start communication: « Where did the rabbit go? What color is this flower?

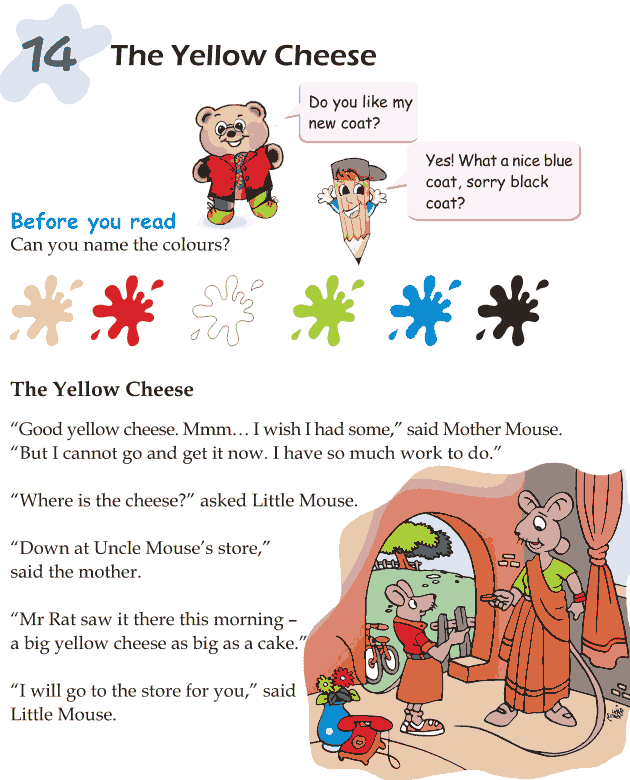

3. Discuss the details of the book. Show the illustrations you like best, name the colors, animals, people and feelings of the characters on each page. At first, the child will not be able to join you, but as they grow older, they will learn from you to turn reading into an interactive process.

How to start communication : « This car is red. Do you see anything else red? Do you want to count the animals?

Do you see anything else red? Do you want to count the animals?

4. Act out the story in faces . Imitate the sounds of sweeping when you see a broom in the picture, or pretend that you want to eat the food drawn. This will help your child make connections between concepts and words, which is the cornerstone of interactive reading.

How to start communication: « Then the caterpillar ate one ... And then she saw someone - who?"

5. Help your child identify with the characters in the book. Start by discussing simple emotions. With age, this ability of the child will improve, and you will be able to ask more complex questions.

How to start communication: « The squirrel wants to sleep - stroke her on the head. Have you ever experienced as much as this baby?"

6. Praise your child while reading. Reward his simplest responses, give him a hug when you finish reading, and praise him for choosing good books or computer applications.

Reward his simplest responses, give him a hug when you finish reading, and praise him for choosing good books or computer applications.

How to start communication: « I am so glad that you chose this book. How well did you navigate the iPad!”

7. Share your opinion about the book. If the child liked the story, ask why. If he fidgets while reading an e-book, ask why. All this will make your reading together more fun.

How to start communication: « Did you enjoy reading this book? Why do you want us to read it again?"

8. Read to your child about things he loves. If your child liked the panda story, ask the library for other books about this animal. Read your child's favorite books, use computer applications, videos, and online resources to help your child learn more about a subject that interests them.

How to start a conversation: « Want to read more about the panda bear? Let's ask the librarian to give us books about pandas" .

9. Stop reading to discuss what you read. Adults are constantly in a hurry to get to the end of a book or appendix in order to finish this business as soon as possible, but stopping for discussion is absolutely necessary so that the child understands what is read well and comprehensively.

How to start communication: « Would you like to pause and take a good look at this mountain? Maybe we should stop and talk about what happened in the book?”

10. Make guesses about the further development of the plot. Such questions give the child the feeling that you yourself are telling him a story and deepen his understanding of what he has read. Children's books are ideal material for this, as they have simple plots with funny twists. Questions of this kind can be the beginning of a detailed discussion, and the habit of asking them lasts a lifetime. I still have fun with this game when I watch movies.

Questions of this kind can be the beginning of a detailed discussion, and the habit of asking them lasts a lifetime. I still have fun with this game when I watch movies.

How to start communication: « Who do you think will win the races? What do you think is hidden in the box?”

11. Maintain a dialogue. When you have finished reading or listening to the book supplement, continue discussing the story. Look for parallels in real life and don't stop asking questions.

How to start communication: « What if we now look at pictures of porcupines? Do you remember what an accordion is? «

12. Expand your child's knowledge. Scientists call this technique "developmental education", and to use it, sometimes it is enough just to read to a child. After all, he still doesn't know how to read! As often as possible, choose books to read on topics that are new to the baby.

How to start a conversation: « Do you know why this car won't start? Do you want me to tell you how she made the soup?”

13. Show your child the world outside of his immediate « environment « . Growing up in rural Michigan, this has become a life necessity. Before I saw France, New York, Guatemala or the Pacific Ocean with my own eyes, all these wonders were revealed to me on the pages of books. Remember to choose books to read about a wide variety of places, cultures, and events, and if your child particularly enjoys something, maintain and deepen their interest.

How to start communication: « Do you want to know what Antarctica is? Show you on a map where France is?

14. Match the plot to the real experience . Help your child to draw an analogy between the events of the book and what interests him greatly in real life. This is how people gain an understanding of the world in which they live. The ability to relate the content of a book or computer application to reality is crucial.

This is how people gain an understanding of the world in which they live. The ability to relate the content of a book or computer application to reality is crucial.

How to start a conversation: « Did you see this animal at the zoo? Were you terribly upset when we left the park too?”

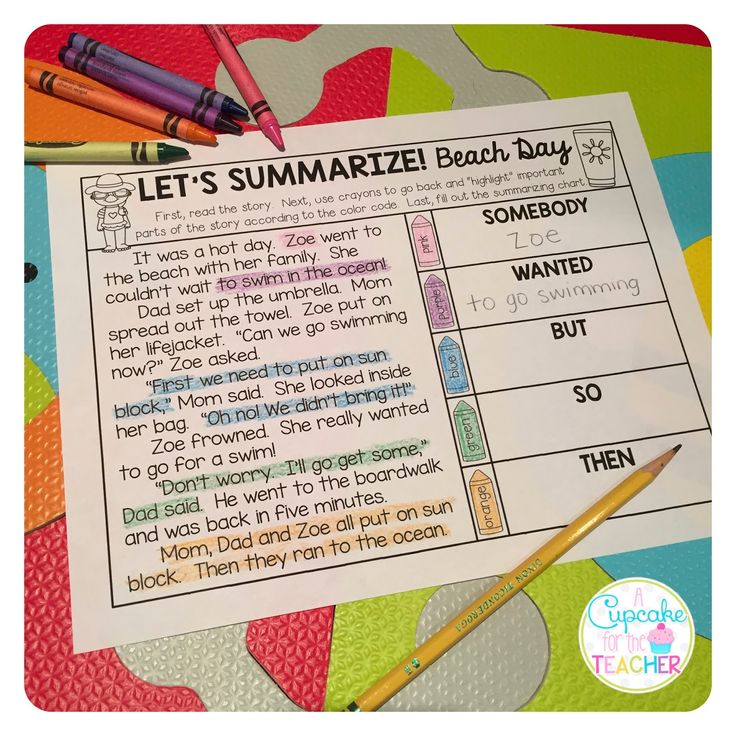

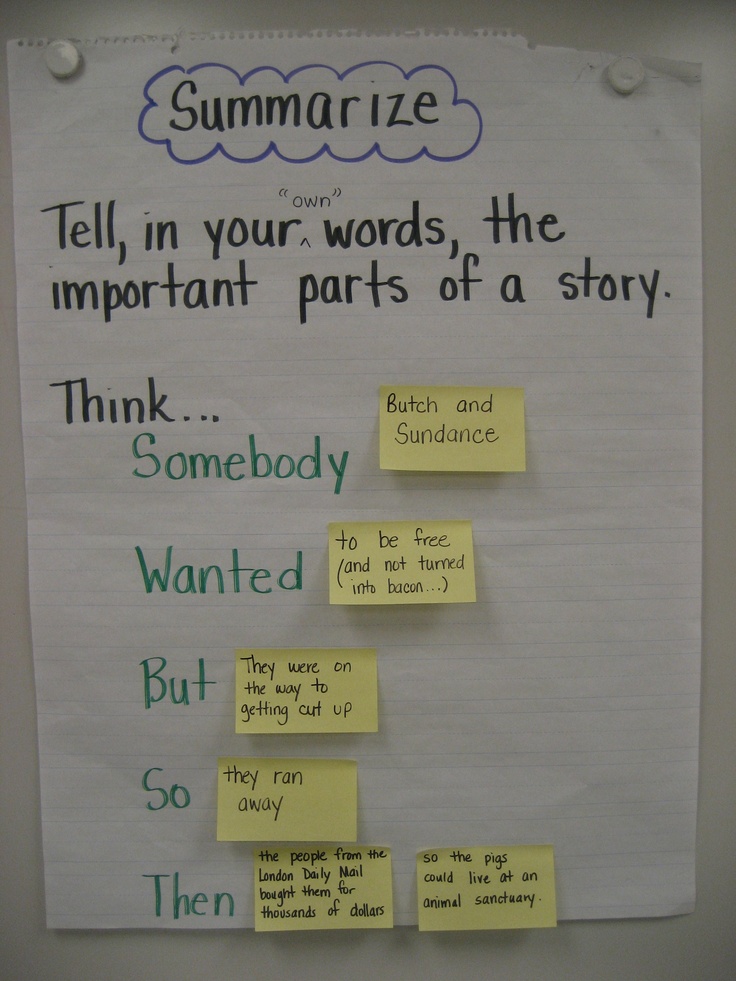

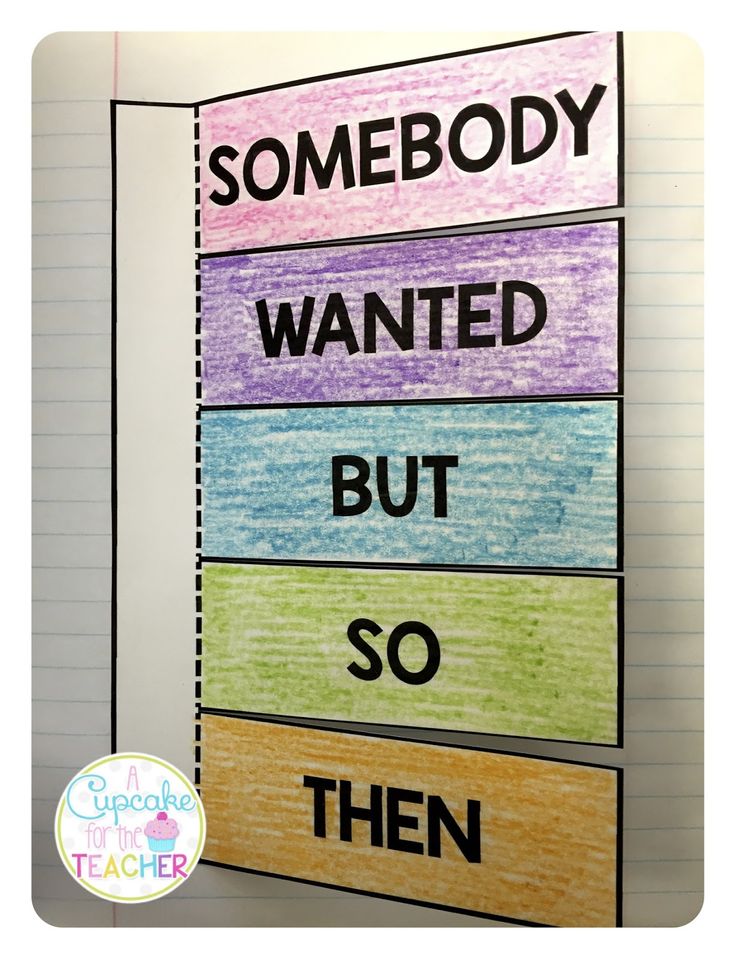

15. Encourage your child to retell favorite stories . I love it when Olive retells her favorite books to me over breakfast. There's no better way to enhance the impact of what you've read and develop your child's storytelling skills!

How to start a conversation : « Can you read this book to your little bear? What happened when Baby Elephant dropped his ice cream?

Interesting read! Jason Boog: Born to Read: How to Befriend a Child with a Book

Did you know that when a child is regularly read aloud - not monotonously and boringly, for show, but by acting out skits and asking interesting questions about the plot - this helps to increase the child's IQ? The author of the book studied a huge amount of research, collected the opinions of child development experts, systematized them and talked about his experience: how he himself read to his daughter Olive and what interactive reading techniques he used to interest and inspire her. His advice will surely come in handy for many parents!

His advice will surely come in handy for many parents!

See also:

Why is reading comics so good for children?

Why is it so important to read aloud to a child

My child has dyslexia. Will he be a doppelgänger?

Photo: FamVeld, didesign021, Africa Studio/Shutterstock.com

developmentpsychology

At what age should a bilingual child be taught to read Russian?

I am very glad to all your questions and continue my Christmas stories about the wonderful world of sounds and letters. Time to move on to one of the most important questions:

— At what age can a child be taught to read?

- I must say right away that this does not depend on age. It's time for a child to start learning to read then, when he is ready for this . And when answering this question, searching the Russian-speaking Internet will not help you. For the simple reason that it correctly and in detail describes the situation of readiness for learning to read for a monolingual child who is preparing for school, that is, 6-7 years old.

Our situation is completely different - children go to school from the age of 4, and they are bilingual. And here we have another main task of teaching reading, no matter how paradoxical it may sound. We teach to read, first of all, in order to develop and retain the Russian language . So that the child has a visual support as early as possible in the form of a syllable, a word and a short sentence, which will allow him to develop phrasal speech, expand his vocabulary and, thus, preserve the Russian language, which after 4 years is on the periphery of his speech activity - a few hours after school with a Russian-speaking parent, and sometimes less. And it is not the main language of knowledge of the world, that is, the language of the educational and play activities of the child. The task of enjoying reading, of regularly reading books in Russian, arises only at the second, later stage, when Russian is preserved. By the way, this stage begins approximately at the age of the beginning of the first grade in Russian-speaking countries - from 6 years old.

It is also important to understand that readiness criteria for learning to read in a bilingual child is formed in two languages and may not be developed in the same way in each language . And if in the Russian language some moment is not fully formed, but it is formed in English, then this does not interfere with starting to teach the child to read in Russian.

What are these criteria for a child's readiness to learn to read ?

Experts consider three main aspects of a child's readiness to learn to read: psychological, speech and phonemic . What exactly do they mean and what are the key points for us to start teaching a bilingual child to read in Russian and what can we turn a blind eye to?

Psychological readiness for reading is associated with the development of the child's cognitive activity and his readiness for learning activities in general. How to define it? Ask yourself the following questions:

Does the book itself arouse curiosity in the child? When you walk into a bookstore or library, do the books spark a keen interest? Does your child like looking at books?

Does he try to "write" his own "book" by sticking pictures on a folded piece of paper or drawing them?

Does he ask adults to read him a book? Would he prefer reading a book or looking at pictures to a TV or a computer? Does he enjoy a bedtime reading ritual, if there is such a thing?

Does he try to “read” the book himself, imitating reading and imitating adults?

For parents of bilingual children, it is clear that it is not very important whether the child is drawn to Russian or English books. It is clear that the books in the store or library are in English, but it is also clear that this does not matter. It doesn't matter if the child tries to write in Latin or Cyrillic, or asks to read an English-speaking or Russian-speaking parent. Our bilingual baby lives in the world of two languages at the same time, simultaneously in two “book worlds”, without separating them in terms of psychological readiness for reading and learning.

It is clear that the books in the store or library are in English, but it is also clear that this does not matter. It doesn't matter if the child tries to write in Latin or Cyrillic, or asks to read an English-speaking or Russian-speaking parent. Our bilingual baby lives in the world of two languages at the same time, simultaneously in two “book worlds”, without separating them in terms of psychological readiness for reading and learning.

Speech readiness , according to monolingual criteria, includes a rich vocabulary, the ability to speak in extended extended sentences, knowledge of poems and songs, the ability to listen and retell fairy tales, solve riddles. Of course, we should take such criteria calmly.

It must be remembered that we are going to teach a bilingual child to read in Russian in order to develop his speech and move towards the named criteria. And do not start, relying on them. Our baby can sing in English and not know a single Russian song, not be able to solve Russian riddles, but I would not particularly worry about this. His total vocabulary in both languages usually exceeds that of his advanced monolingual peer, and active grammatical constructions in speech include two grammatical systems that he already separates well. Not to mention the intonations of both languages, the ability to feel the speech situation and context.

His total vocabulary in both languages usually exceeds that of his advanced monolingual peer, and active grammatical constructions in speech include two grammatical systems that he already separates well. Not to mention the intonations of both languages, the ability to feel the speech situation and context.

But the phonemic readiness of is a key point for us. But there is some amazing news! It consists in the fact that this readiness in a bilingual baby is formed easier than precisely because he had to learn to hear and pronounce twice as many sounds very early and his phonemic perception developed more intensively. In the world of sounds, a bilingual child is a much more serious expert than a monolingual child. It is very important for us to support and preserve this “experience of absorbing sounds” in order to develop literacy in Russian on its basis. Our language is phonetic, we write by ear. Spelling is important, but secondary to auditory writing skill.

What exactly do we need to form for a child's phonemic readiness? Let's make a short list:

The ability to clap words by syllables and the ability to say how many times clapped (name the number of syllables).

The ability to distinguish the first sound in a word.

The ability to name words for a given sound. For example, to the sound O or the sound A. (Not to the letter! The child will only learn letters🙂, while he already hears the sounds.)

The ability to select words to rhyme. And it doesn't really matter what language. Although, of course, it is very desirable that the child could name “words that sound similar” in Russian. For example, poppy varnish.

The ability to hear a certain sound in a word and the same sound in other words. For example, in the word mouse-sh-sh-shka you hear "wind song: sh-sh-sh-sh". Show objects that also have “wind song” in their name. You need to select pictures whose names contain the sound [Ш] from a set of cards on which, for example, are drawn: skis, tires, sleds, a car, a wheel. That is, the child must be able to differentiate consonants by ear. In this case W-W-S.

Is it necessary for a bilingual child to pronounce all the sounds of the Russian language clearly in order to learn to read Russian? I will express a seditious thought - no, not necessarily. Moreover, teaching reading in our country leads to two very important results: a significant improvement in pronunciation in Russian and the prevention of an English accent in it. In children with an English accent that has already appeared, it goes away, softens, and with regular and not at all difficult exercises, you can remove it.

It is highly desirable that the child could hold a pencil - paint, be able to draw straight and oblique lines. But this is usually done by most British children by the age of 4-5. Namely, at this age it is optimal to start teaching a bilingual child to read in Russian. Some a little earlier, some a little later, of course. As far as readiness, psychological and phonemic first of all.