Trouble following directions adults

Why Following Directions Is Hard for Some People

By Amanda Morin

Quick tips to help with following directions

Quick tip 1

Get rid of distractions.

Get rid of distractions.

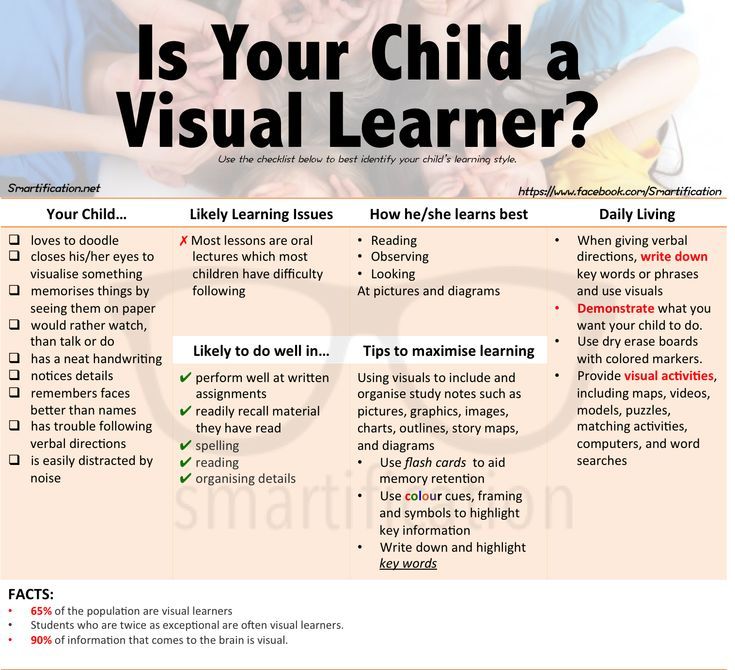

Make it easier to “hear” directions by limiting distractions. If possible, find a space that’s away from a lot of noise, movement, or clutter.

Many people — kids and adults — have trouble following directions. They don’t seem to “listen” when they’re asked to do a task, whether it’s taking out the garbage or taking care of a pet. Even if there’s a negative consequence, they don’t do what they’re supposed to do.

Why does that happen?

It might seem like laziness or a lack of respect. But when people frequently don’t follow directions, there’s often something else going on.

But when people frequently don’t follow directions, there’s often something else going on.

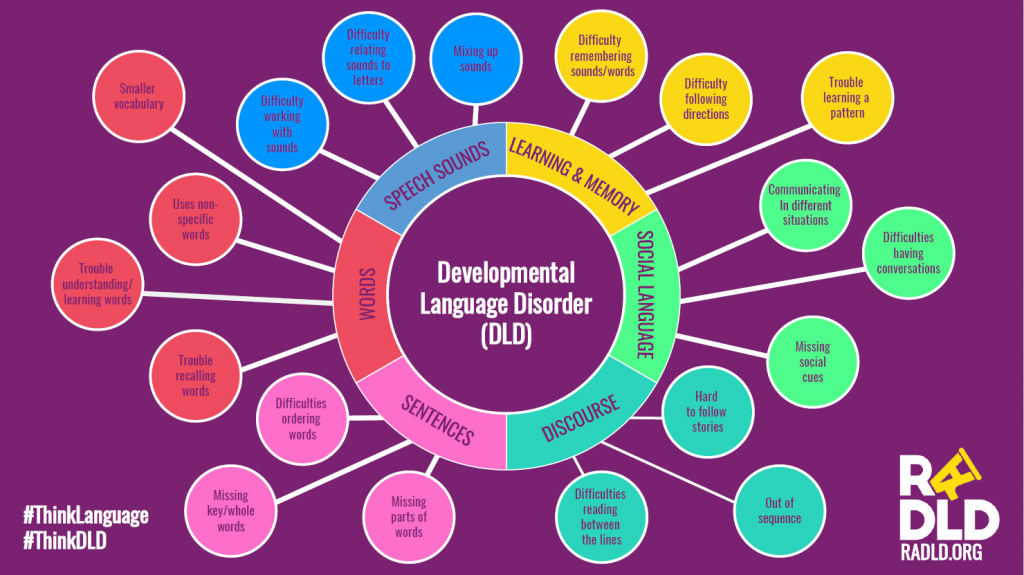

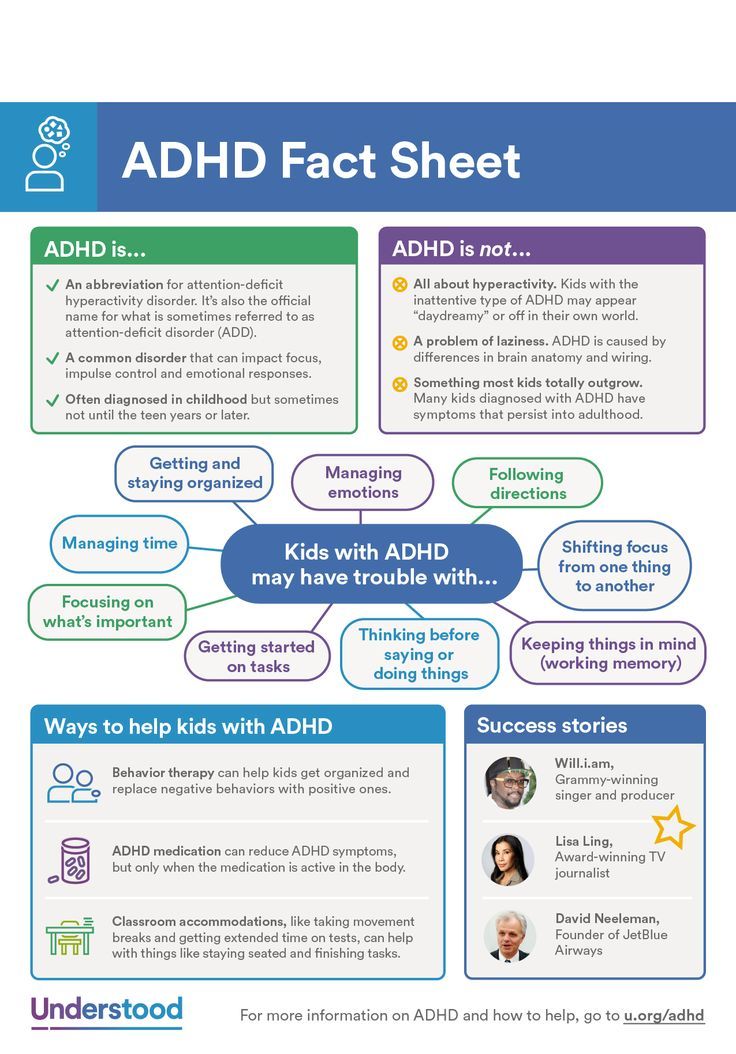

A common reason is trouble with executive function, a group of skills needed to get through tasks. Some people also have a hard time processing information or tuning in to what others are saying.

When people have trouble following directions, the results are clear — things don’t get done, or they get done poorly. But people may also struggle in ways that seem confusing or not directly related.

For example, kids and adults might:

- Get easily frustrated when trying to do something

- Agree to do something and then not do it

- Look away or zone out when being given directions

- Get halfway through a task and then stop

- Say they did something when they didn’t

There are different reasons people struggle with directions. It's not a matter of intelligence, but rather challenges with specific skills.

Dive deeper

Related topics

Following instructions

Tell us what interests you

About the author

About the author

Amanda Morin is the author of “The Everything Parent’s Guide to Special Education” and the former director of thought leadership at Understood. As an expert and writer, she helped build Understood from its earliest days.

As an expert and writer, she helped build Understood from its earliest days.

Reviewed by

Reviewed by

Bob Cunningham, EdM serves as executive director of learning development at Understood.

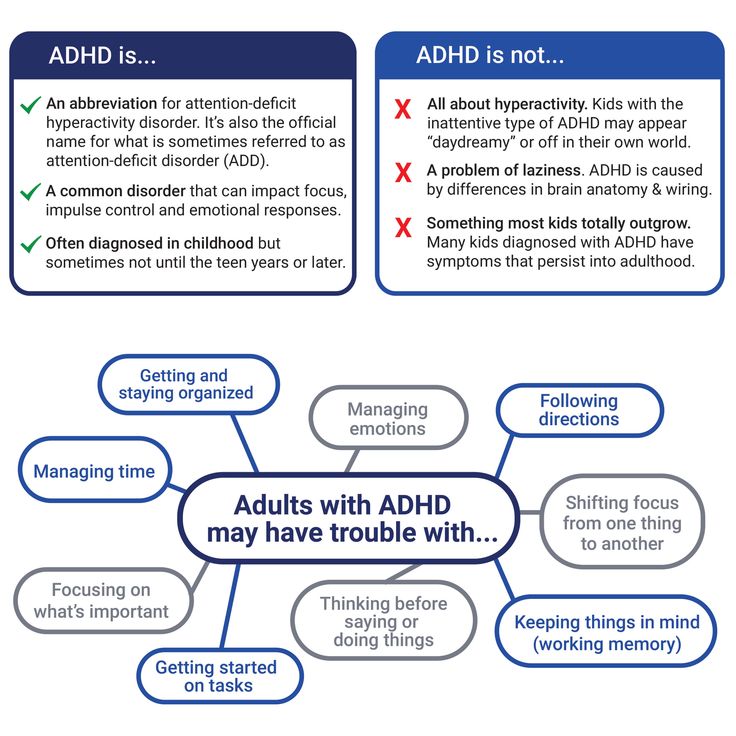

Problems Following Directions? It Might Be ADHD / ADD

When I was 10 years old, I had to sew an apron to earn a Girl Scout merit badge. I did all the cutting and the piecing and the sewing according to a pattern with strict directions. I picked out pretty fabric. I pinned. I snipped. I sewed. But when I held up what I’d made, it didn’t resemble an apron. The sides were uneven, the bottom too long, and the pocket sewn shut. Everyone sighed. “This wouldn’t have happened if you had just followed the directions,” my grandmother scolded. But I couldn’t follow the directions, not without help. I had undiagnosed attention deficit disorder (ADHD or ADD). Moving from step one to step 10, in sequence, is pretty much impossible for me.

This happens with ADHD. Instructions get fuzzy. It’s difficult for me to follow directions without skipping steps or changing or rearranging something. This makes it hard for me to help my kids do certain crafts, for example, crafts that call for gluing down tissue paper, then adding googly eyes, then pasting on ears and nose and, crap, those whiskers won’t stay glued on, so let’s use tape. Not what the maker intended, but when the creation is complete, the result is often better than the original.

Instructions get fuzzy. It’s difficult for me to follow directions without skipping steps or changing or rearranging something. This makes it hard for me to help my kids do certain crafts, for example, crafts that call for gluing down tissue paper, then adding googly eyes, then pasting on ears and nose and, crap, those whiskers won’t stay glued on, so let’s use tape. Not what the maker intended, but when the creation is complete, the result is often better than the original.

Not Following the Rules

Artistic — that’s what we call people who don’t follow the rules, who create their own path, who use surprising materials and take things in interesting directions. That’s what many of us with ADHD do. I love to make things, and I’ve learned that anything I try to make according to strict directions is doomed to fail. My ADHD neurology won’t allow it.

That doesn’t just apply to art. This innovation I learned, this making-do because I can’t move from point A to point B without a detour, has helped me in many areas of my life. Take dressing. It’s hard, in many cases, for ADHD women to read subtle social cues that tell us how to act and behave. We interrupt a lot; we blurt out odd or inappropriate statements. We spend too much time on our phones. We also miss subtle cues, like what’s in style and how we’re supposed to dress. So, long ago, I decided to say forget it, and started dressing not in ways society called fashionable, but in ways I liked. I embraced thrift-store fashion, the leopard-print cardigan. I mix stripes and plaids. I spent an entire year wearing nothing but dresses, because I wanted to. Right now, it’s long tulle tutu skirts. I pull one on with a tank top and a black leather jacket, and everyone says I look awesome. They always do. Because in a sea of leggings and boots and bland tunics, I stand out.

Take dressing. It’s hard, in many cases, for ADHD women to read subtle social cues that tell us how to act and behave. We interrupt a lot; we blurt out odd or inappropriate statements. We spend too much time on our phones. We also miss subtle cues, like what’s in style and how we’re supposed to dress. So, long ago, I decided to say forget it, and started dressing not in ways society called fashionable, but in ways I liked. I embraced thrift-store fashion, the leopard-print cardigan. I mix stripes and plaids. I spent an entire year wearing nothing but dresses, because I wanted to. Right now, it’s long tulle tutu skirts. I pull one on with a tank top and a black leather jacket, and everyone says I look awesome. They always do. Because in a sea of leggings and boots and bland tunics, I stand out.

Because I hate explicit directions and find them confining, I imagine my children must feel the same way. So I had no worries eschewing the traditional stay-in-your-seat-for-seven-hours classrooms, even though my husband is a public school teacher. Instead, we school at home. I made up our curricula, from insects and electricity to reading and the Revolutionary War. We are free to roam over all of human knowledge, however we want, in whatever order we want. I had confidence I could give them the education they needed: I was used to making things up, either in part or whole-cloth. And since my seven-year-old can cite the dates of the Battle of Yorktown, and reads at a fifth-grade level, with no tests and no desks, I think I’ve done something right.

Instead, we school at home. I made up our curricula, from insects and electricity to reading and the Revolutionary War. We are free to roam over all of human knowledge, however we want, in whatever order we want. I had confidence I could give them the education they needed: I was used to making things up, either in part or whole-cloth. And since my seven-year-old can cite the dates of the Battle of Yorktown, and reads at a fifth-grade level, with no tests and no desks, I think I’ve done something right.

This ability to innovate also reaches into the ways that my husband and I cope with my mental health. Both of us have ADHD; both of us are used to making things up on the fly. I also have several mental illnesses, including mild BPD, which means I sometimes run off the rails. Rather than freak out about these emotional trainwrecks, we work with them. We problem-solve. What can we do to make this better? It might mean that he drives me around in the car while I sing along to Hamilton: The Musical as loud as possible. It might mean we pile the whole family in the van and go get some ice cream at Sonic. It may mean my husband shoves my glue gun at me and says that the kids need Wild Kratts costumes. We know we can’t fix whatever’s wrong with me, but we can deal with it in the short term, and that calls for some creative solutions.

It might mean we pile the whole family in the van and go get some ice cream at Sonic. It may mean my husband shoves my glue gun at me and says that the kids need Wild Kratts costumes. We know we can’t fix whatever’s wrong with me, but we can deal with it in the short term, and that calls for some creative solutions.

[Free Download: Unraveling the Mysteries of Your ADHD Brain]

We Make Different Choices

This creativity also works with our relationship itself. Yes, sometimes in the cutesy oh-look-I-scheduled-a-sitter-spontaneously way. But most often in the gentle ways that two people move around each other without argument. He leaves his underwear on the floor; I accept it and pick it up. I leave the bathroom a mess of makeup and hair product; he ignores it. We’re supposed to remonstrate with each other over these transgressions: “You did this and you can’t do it because” — because why? We don’t adhere to traditional beliefs like that. Because we don’t care. Our ADHD lets us look at the situation, question it, and decide to make different choices. We’re so used to making things up that making up real life is no big deal.

We’re so used to making things up that making up real life is no big deal.

We’re also willing to make life choices other people find questionable — the type we rationalize with the phrase “you do you.” I have an Emotional Service Dog, a weird solution to crippling anxiety, and he helps me immensely. I’m willing to try things most people would scoff at. My kids have never heard of Minecraft or Pokemon. Our dream vacation is hunting salamanders in the Shenandoah Valley. Most people would call us weird. We call ourselves different, because we’re not afraid to be our authentic selves and go after what we really want.

No Point A to Z for Us

That’s because we learned an important lesson when we were young. We can’t trek straight from point A to point Z. We take detours. We linger. We backtrack and jump ahead. We’re not running on the same sequential, linear, neurotypical time.

We made another apron, my grandmother and I, with my following every directive she made, feeling stupid each time I jumped ahead or went too fast or missed a step. But when the Halloween popsicle-stick house I was making for my youngest didn’t go according to plan? I just cut up some extra popsicle sticks and slapped them onto places the directions didn’t call for them to go. They masked the glue-gun lines. They filled in the roof gaps. They looked awesome. I always hated that apron, and lost it as soon as I could. I cherish that Halloween house.

But when the Halloween popsicle-stick house I was making for my youngest didn’t go according to plan? I just cut up some extra popsicle sticks and slapped them onto places the directions didn’t call for them to go. They masked the glue-gun lines. They filled in the roof gaps. They looked awesome. I always hated that apron, and lost it as soon as I could. I cherish that Halloween house.

I’ve discovered a secret: It’s best if it doesn’t go according to plan. Then it’s really yours. In that lopsided popsicle stick house, I saw creativity. I saw innovation. I saw love. And most of all, I saw beauty.

[9 Productivity Tips for the Easily Distracted]

Previous Article Next Article

What is Oppositional Defiant Disorder in Adults

An adult with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) can become angry at the whole world and often "lose his temper" for no reason. This can manifest itself as road rage or verbal abuse. This can cause tension in relationships with people in authority and problems at work. This can lead to a breakdown in relationships. Although this psychological state is more often associated with childhood, without proper help it passes into adulthood and disrupts it. nine0003

This can manifest itself as road rage or verbal abuse. This can cause tension in relationships with people in authority and problems at work. This can lead to a breakdown in relationships. Although this psychological state is more often associated with childhood, without proper help it passes into adulthood and disrupts it. nine0003

Dmitry Mayorov

Pixabay

Adults with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) feel angry at the world, misunderstood, squeezed, and marginalized. Their constant confrontation with people can make it difficult to keep a job, relationship, and marriage.

Contents of the article

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is more common in adults than you might think. People with this disorder are always angry. They are prone to arguments, easily lose their temper, experience problems in the family, in society and at work. nine0003

Oppositional defiant disorder in adults: development and course

In fact, it is very common for children with deviant behavior to develop antisocial personality disorder.

However, the lack of control over temperament in adulthood leads to a somewhat more problematic psychological reality.

Indeed, such opposition to people in adulthood borders on much more complex and dangerous types of behavior. nine0003

According to statistics, 5 to 15% of schoolchildren suffer from oppositional deviant disorder. However, in a significant number of cases, the diagnosis is not made. So very often, people in their 20s, 30s, or 40s exhibit behavior that is as unfavorable as it is conflicting.

Symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder in adults

Some children can be difficult, difficult and even problematic in terms of behavior and parenting. However, this does not mean that they suffer from ODD. nine0020

Actually, oppositional defiant disorder is a recurring condition in childhood in which a set of complex behaviors develop in a spiral pattern.

This behavior includes aggressiveness towards authority figures, parents, peers, constant tantrums, vindictive behavior, resentment, constant irritability, etc.

Moreover, if ODD is not treated at an early stage, it can lead to criminal behavior and serious social maladaptation in adulthood. nine0003

An adult with ODD demonstrates a clear inability to integrate into a social environment with basic behavioral norms.

If the school stage was problematic for them, then keeping a job in adulthood can be even more difficult. For this reason, they usually do not stay long in one position.

The most common behaviors of adults with oppositional defiant disorder:

- They often lose patience. They have extremely low resistance to any kind of frustration. nine0056

- They have noticeable mood swings. However, most often they experience irritability.

- They consider themselves rebels. In addition, they consider themselves independent people who live their own way. However, the obvious contradiction is that they are completely unable to adapt to almost any situation. They experience problems at home and at work. In addition, it is difficult for them to keep friends, partners, etc.

- They show no personal responsibility. nine0056

- They don't respect rules and laws. They also don't take advice.

- They are constantly angry at the world, the system, and all authority figures.

- They consider themselves misunderstood. Indeed, in their opinion, no one appreciates their virtues, their potential, or their good work.

- They are prone to verbal violence.

- They exhibit dangerous driving behavior.

- They may develop addictive and aggressive behavior (angry or vindictive). nine0056

Causes of oppositional defiant disorder in adults

There are several theories that explain the occurrence of oppositional defiant disorder in adults:

- On the one hand, there are neurobiological approaches.

They are related to genetic causes.

They are related to genetic causes. - Then there is the social explanation. It concerns dysfunctional models of upbringing and education. For example, there are often aggressive fathers and depressed but controlling mothers. nine0056

While the triggers for this behavioral disorder are not entirely clear, there is one undeniable reality.

It is the fact that any child or adolescent who does not receive psychological help for their defiant disorder develops more problematic behaviors in adulthood. In fact, very often they end up with antisocial personality disorder.

For this reason, early diagnosis is essential to avoid and prevent adult oppositional defiant disorder and antisocial personality disorder. nine0003

However, the study also warns of another fact. It suggests that ODD tends to be accompanied by other psychiatric disorders.

Similar diagnoses with an opposition-calling disorder of

Conductive disorder:

- Conductive disorder and OVR are both associated with problems with the behavior leading to conflicts with representatives of the authorities (for example, parents, chiefs).

nine0056

nine0056 - The manifestations of ODD are less severe than those of conduct disorder and do not include aggression towards people and animals, destruction of property, deceit, and theft.

- ODD is associated with problems in regulating emotions (anger and irritability) that are not symptoms of conduct disorder.

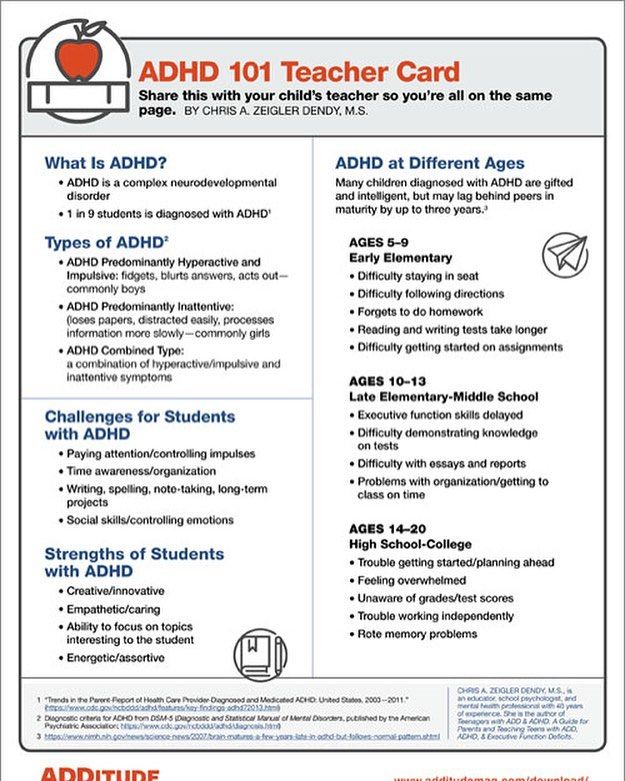

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD):

- ADHD is often paired with ODD.

- An additional diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder requires the establishment that the individual's reluctance to follow requests and demands occurs not only in situations requiring effort or attention, or when it is required to sit quietly (eg, in a classroom, in a meeting, in line). nine0056

Depression and bipolar disorder:

- Depression and bipolar disorder often involve negative emotions and irritability.

- Therefore, the diagnosis of ODD cannot be made if its symptoms occur solely in the context of mood disorders.

Behavioral Disorder:

- Behavioral Disorder and ODD are both associated with chronic low mood and temper tantrums. nine0056

- However, the severity, frequency, and chronicity of temper tantrums are more pronounced in individuals with conduct disorder than in individuals with ODD.

- Thus, only a small proportion of adults with ODD suffer from behavior regulation disorder. People with this disorder are not diagnosed with ODD, even if they meet all of its criteria.

Unstable Personality Disorder (NPD):

- NPD is also characterized by outbursts of anger. However, this disorder is associated with serious manifestations of aggression that are not symptoms of ODD. nine0056

Intellectual disabilities:

- People with intellectual disabilities are diagnosed with ODD only if oppositional behavior is much more pronounced than in individuals at a similar level of mental development with the same disease.

Perceptual impairment:

- ODD is also not to be confused with difficulty following directions associated with perceptual impairment (e.g. hearing loss). nine0056

Anxiety disorder (social phobia):

- ODD should also be distinguished from defiant behavior associated with fear of negative evaluation of others, which is characteristic of anxiety disorder.

Treatment of oppositional defiant disorder in adults

Adults with ODD find it very difficult to take responsibility for their behavior. In fact, in many cases they remain blind to the consequences of their behavior. nine0020

At the same time, they are extremely susceptible to disorders such as depression. This is due to their isolation and the weakness of their support system.

In fact, it seems that here one reality contradicts the other. This is because these people directly suffer the consequences of their actions. However, they often deny the need to make any changes to their behavior.

Treatment approaches for oppositional defiant disorder in adults

Early treatment can often prevent future problems. Treatment will depend on the symptoms, age, and health of the individual. It will also depend on how pronounced the degree of OVR is.

People with ODD may need to try different therapists and therapies before they find what works for them.

Treatment may include:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy. A person learns to solve problems and communicate better. He or she also learns to control impulses and anger. nine0056

- Family therapy. This therapy helps to change the family.

This improves communication skills and family relationships.

This improves communication skills and family relationships. - Group therapy. A person develops better social and interpersonal skills.

- Medical treatment. It is not often used to treat OVR. But a person may need them for other symptoms or disorders, such as ADHD.

Life with oppositional defiant disorder can be managed with the right support. If you think you or someone close to you may have ODD, consult with a healthcare or mental health professional to rule out other causes for your symptoms. nine0020

youtube

Click and watch

How to help your child become independent

When parents think about their child's independence, they dream that he would do everything himself, while doing it quickly and very accurately. But the fact that the child does only what his parents tell him to do is not taken into account. Get up in the morning, brush your teeth and wash your face, then go to breakfast - no problem! However, following such simple instructions does not mean that the child becomes independent, he develops only obedience. nine0003

nine0003

The habit of following the instructions of adults grows further into disobedience, passivity, lack of initiative. All this is a psychological problem.

The manifestation of independence in children before school

Independence itself can develop quite early, this moment should not be missed. Already at the very early age of one to two years, the child begins to form his first conscious desires and the need for independent actions. As soon as the child begins to understand that he can personally fulfill part of his needs, he takes action to this end. At such moments, parents begin to panic and forbid all this to the child, fearing that he will get hurt or break something. nine0003

The first real crisis of growing up occurs in a child at the age of three or four. This happens when it becomes clear to him that his desires and actions may differ from what adults tell him. This can quickly affect the baby, discourage the desire to independently take any action and make decisions. The child realizes that it is not necessary to make efforts in various areas at all, because his parents will decide everything.

The child realizes that it is not necessary to make efforts in various areas at all, because his parents will decide everything.

At the age of five, a child begins one of the important stages of life, conditionally called "I myself!". The kid begins to want to help with cleaning, take care of pets, and even a desire to go grocery shopping himself. That is, the need to perform independent actions is already beginning to form. nine0003

Children can start school as early as the age of six, as by that age they may already be independent enough to study. The kid can know the way to school, be active in the classroom and do homework on time. However, most adults consider this age too young and continue to take care of their child.

Adolescent independence

An urgent need to act independently begins to appear in children as early as ten years old. This stage of life passes much faster and more confidently, if before that the parents instilled confidence in the child's strengths, actions, decisions. Otherwise, conflicts may arise. nine0003

Otherwise, conflicts may arise. nine0003

Parents should be wise and patient when dealing with a teenager. You can’t control the child as much as possible, limit him in actions, overestimate expectations from study, treat him with indifference if you want to raise him self-sufficient and successful. In order to avoid mistakes in education, you can use the advice or contact, if necessary, a child psychologist teacher.

Advice for parents

- Give your child the choice of who to be friends with

Direct control of a child's communication and choice of whom to be friends with is unacceptable and incorrect. Such an attitude will cause resentment in the child, he will argue with you, be angry with you, because this infringes on him as a person. You can speak softly to him and somehow guide him carefully in his choice.

What is required? To begin with, try to keep your child's contact with obviously bad children to a minimum. If unpleasant or conflict situations arise, try to have conversations with the child and solve them together. nine0003

If unpleasant or conflict situations arise, try to have conversations with the child and solve them together. nine0003

- Decide about your studies in advance

Solving such problems should be based on two rules. First: prepare a competent schedule, allocate time for homework, time for rest. Teach your child to follow this schedule. Second, make an agreement. Good relationships develop through the development and adoption of a number of feasible agreements. So, if the child completes one of these, then as a result he will receive some kind of encouragement. Otherwise, he will be punished, not somehow rudely or with words, but through small deprivations of pleasant things. nine0003

- Allow independent elections

When resting, the child must be given a choice of how and what to do. You can put before a choice, for example, walk or watch TV, ask what game to play. These choices make the child feel like he is making his own decisions and not just listening to his parents. With development, the baby will begin to understand the limits of his abilities, which can expand.

With development, the baby will begin to understand the limits of his abilities, which can expand.

It would be correct on the part of adults to indicate to the child that the parent is more important and should be obeyed, but still give the child a choice in some matters. nine0003

This behavior will give the child the feeling that he has a choice in what to do next.

- Acknowledge the child's own opinion

When developing independence, it is very important to have your own opinion and your own views on the world around you, as well as to receive parental approval on various issues. Adults should pay more attention to the opinion of their child, but at the same time not impose their views. Trust in communication, discussion of problems helps in the formation of a healthy personality in children. nine0003

- Feelings must not be forbidden

Often adults tell the child what he needs to feel in a given situation, how to react to some action.