What is emergent writing

Emergent Writing | ECLKC

Emergent Writing

Narrator: Welcome to this presentation of the 15-minute In-Service Suite on Emergent Writing. This presentation describes what emergent writing looks like in young children and shares practical ways that you can begin to support emergent writing at home and in early childhood programs.

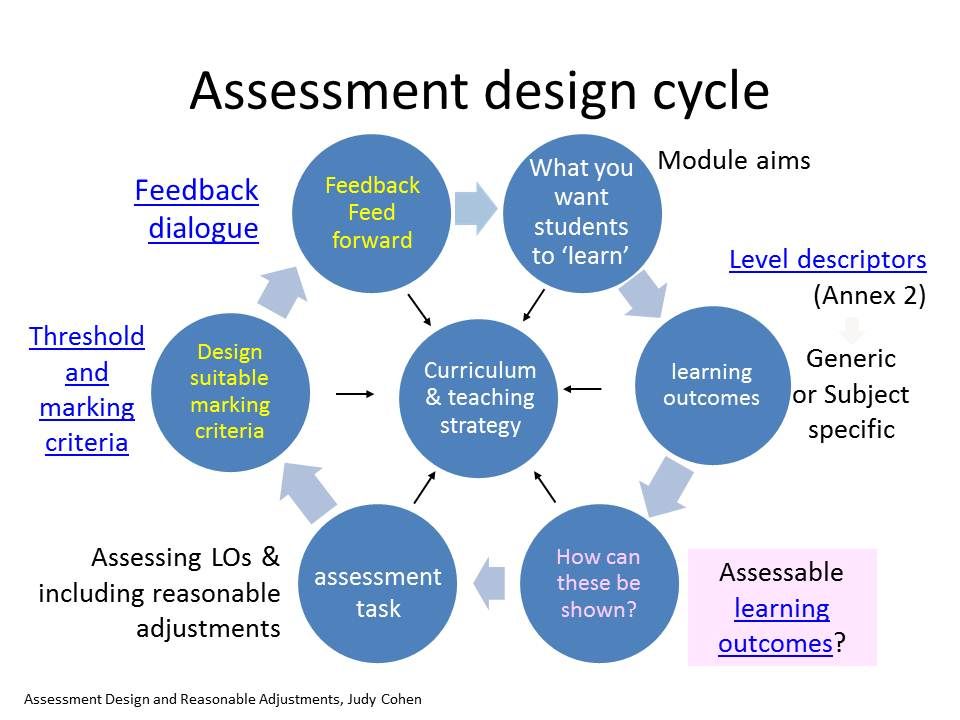

The framework for effective practice, or house framework, helps us think about the elements needed to support children's preparation and readiness for school. The elements are the foundation, the pillars, and the roof. When connected to one another, they form a single structure that surrounds the family in the center, because as we implement each component of the house in partnership with parents and families, we foster children's learning and development.

Implementing research-based curricula and effective teaching practices helps support children as they develop the skills necessary to engage in emergent writing. This presentation on emergent writing is one in a series of modules designed to help adults support young children as they learn positive behaviors, develop skills in STEAM, math, and writing, and engage in dramatic play.

Learning to write goes beyond the process of proper spelling and grammar. Writing is a means of written communication that can be understood by others because it follows a particular set of shared rules. Children as young as 2 years begin to understand that text has meaning and can be used to express ideas, feelings, and stories. Emergent writing is children's earliest attempt at written communication.

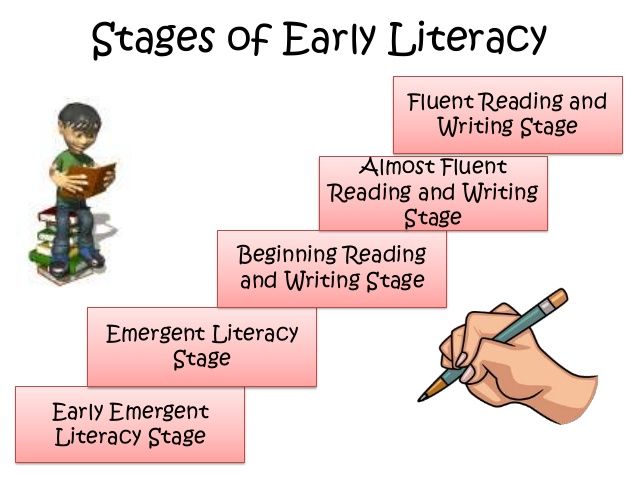

In its earliest stages, writing looks like scribbling and drawing and eventually begins to include letters of the alphabet, invented spelling, conventional spelling, and basic grammar. Most children go through predictable key stages on the path to emergent writing. However, as with nearly all areas of child development, children progress at different paces and may often display skills across multiple stages at the same time. Thus, the stages we present here are guidelines for teachers and home visitors to support individual children's efforts to communicate in writing and develop their skills.

Thus, the stages we present here are guidelines for teachers and home visitors to support individual children's efforts to communicate in writing and develop their skills.

In the earliest stages of writing development, children's writing does not include the intentional use of letters, but instead resembles scribbling or drawings. At first, children make random marks and attach no meaning to them, but later, the child intends the marks to be writing that conveys a message.

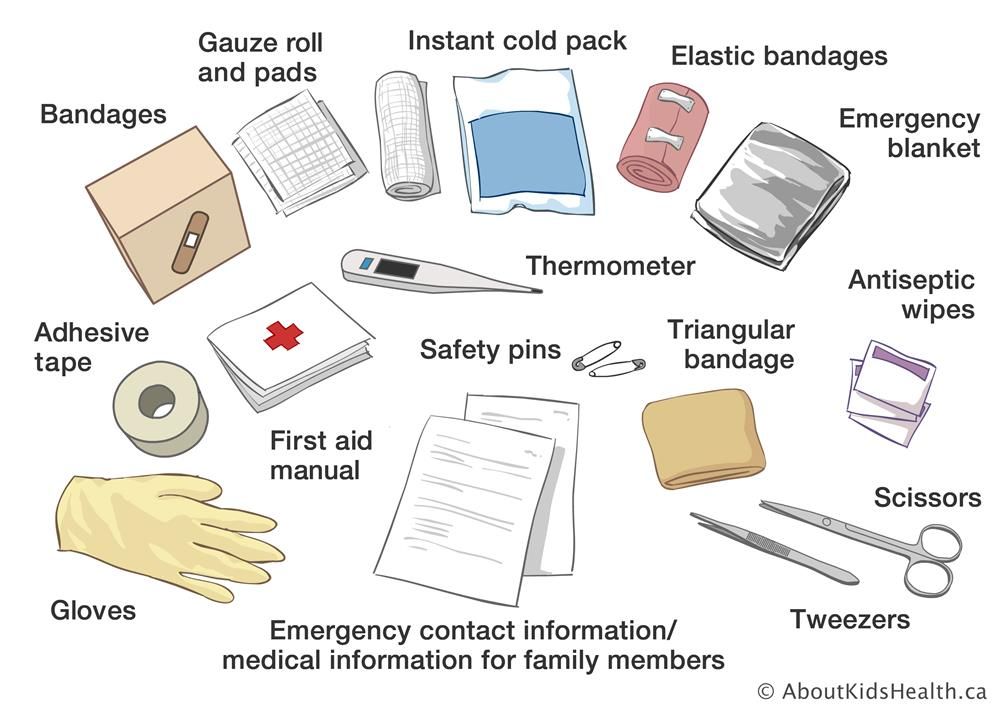

You can support the earliest stages of writing by providing children with a variety of writing materials and implements and encouraging their use. Don't be afraid to let children explore making different kinds of marks on paper, or other writing surfaces.

If your children can talk, be sure to ask them questions about their drawing and model writing skills by writing down what children say under their picture. Equally important is revisiting their drawings and what they said about their drawings the next day. This helps instill the idea that writing is read the same way each time and its meaning doesn't change.

This helps instill the idea that writing is read the same way each time and its meaning doesn't change.

In the middle stages of writing development, children begin to understand that there are rules to writing that are unique to their home language. These rules include using letters, symbols, and characters and following the directional order of writing, such as top to bottom and left to right. During this stage, children write their names but may not yet make the connection between the letters they write and their specific letter sound.

In the late stages of writing development, which may emerge in the late preschool years, children intentionally use letters to represent particular phonetic sounds. We often refer to this as "invented spelling" because it's based on what the child hears. Eventually, the child learns conventional spelling, including the irregularities in words, such as silent "Es" at the end of words like "cake." They also begin to write short phrases and begin to follow grammatical rules, such as using punctuation and starting sentences with uppercase letters.

Supporting the middle and later stages of writing usually begins by helping children write their names. This experience helps children to learn that strings of letters have meaning, a purpose, and are associated with particular sounds.

Teachers and other staff, as well as family members, can also serve as intentional writing models throughout the day, carefully pointing out the process of writing or practicing sounding out or spelling a word. Importantly, teachers and parents can provide authentic opportunities for peer scaffolded and independent writing across the day.

We can support the emergent writing of all children by first remembering that we're supporting a process, not an outcome. This process supports a child's school readiness, since writing skills develop across the primary school years and beyond. It's important to take the time to identify if a child is in the beginning, middle, or later stages of writing, in order to provide the proper support and learning experiences to help them develop in this area. Having a sense of what stage of writing a child is in will help you to anticipate potential problems with writing, as well as what you can do to help children grow and develop.

Having a sense of what stage of writing a child is in will help you to anticipate potential problems with writing, as well as what you can do to help children grow and develop.

We hope you have new ideas to expand on the ways teachers can create environments and activities to support emergent writing skills. For more information and more ideas, see the complete 15-minute Suite on emergent writing and take a look at our tips and tools and helpful resources.

Close

Stages of Emergent Writing | Thoughtful Learning K-12

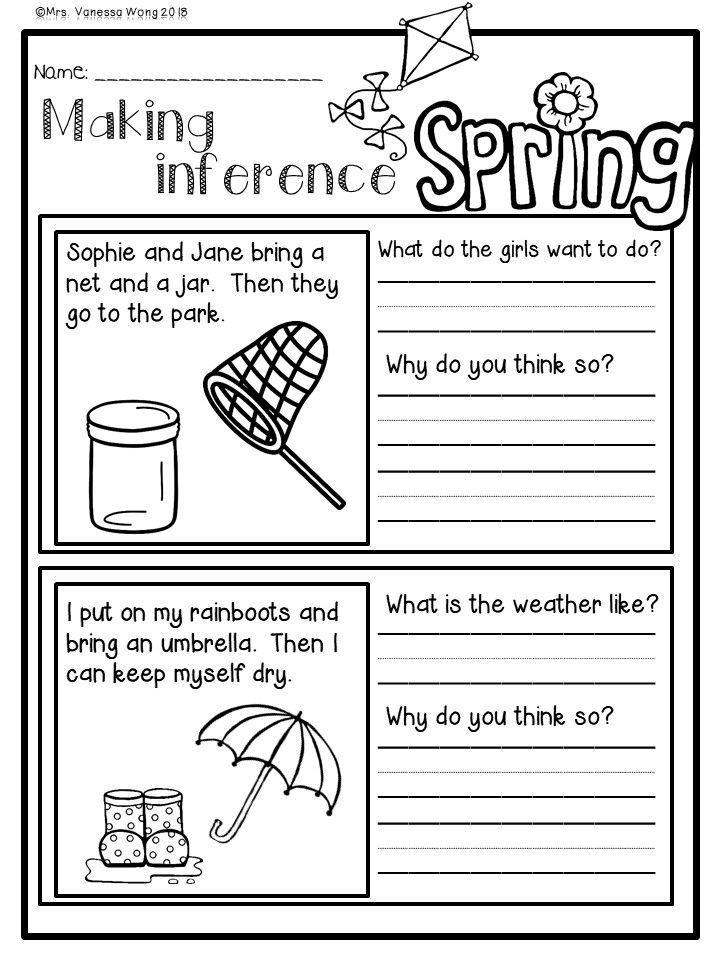

Emergent writers discover many ways to send written messages. The writing samples on this page demonstrate different kinds of writing evident in a kindergarten classroom. Each sample demonstrates one or more of the qualities of effective writing.

Drawing and Imitative Writing

The child writes a message with scribbling that imitates “grown-up” writing. It shows individuality and an attempt to communicate with others.

Copying Words

The child copies words from handy resources like books, posters, and word walls. The writing makes sense and shows knowledge of letter formation and the concept of words.

Drawing and Strings of Letters

The child writes with random letters to convey a message. The letters are formed well, but have no relationship to sounds. The writer is aware that print and art convey meaning.

Early Phonetic Writing

The child writes words using letters (mostly consonants) to represent words and sounds. The writing shows individuality, focuses on a topic, and makes sense.

Phonetic Writing

The child writes words using letters to represent each sound that is heard. The words make sense and may be used for writing longer texts.

Conventional/Some Phonetic Writing

The child focuses on a topic and uses close-to-correct copy. The writing demonstrates an emerging voice.

Drawing and Imitative Writing

In this type of early writing, the child writes a message or shares ideas with others through drawings and imitative writing. Scribbling and random letters are often considered to be an imitation of “grown-up” writing.

Scribbling and random letters are often considered to be an imitation of “grown-up” writing.

The first example here shows individuality. Notice the use of made-up letters to imitate writing.

The second example shows an attempt at appropriate formation of letters and words.

Copying Words

In this type of early writing, the child copies words from handy resources like books, posters, and word walls. The writer may or may not be aware of the meaning of the words.

The first sample here shows the child’s ability to use art, form letters, and copy a title from a book. The writing focuses on the topic “My Favorite Story.”

In the second sample, the writer copies a string of unrelated words for the topic “Fishy Words.” The writing shows a beginning use of words and formation of letters.

Drawing and Strings of Letters

In this type of early writing, the child writes with random letters but has a definite message to convey. The letters often have no relationship to conventional letter sounds or spelling. (Sometimes a teacher or scribe translates the message into conventional form.)

(Sometimes a teacher or scribe translates the message into conventional form.)

The writer of the first sample translates her string of letters as “playing with my baby sister.” Through art, the child focuses on the topic. A beginning ability to form letters is shown.

According to the writer of the second sample, the title is “Riding My Bike.” An early attempt at forming letters is shown. The illustration supplies some of the meaning.

Early Phonetic Writing

In this type of early writing, the child writes connected letters (mostly consonants) to represent words. Sometimes the sound of the letter itself is used for a word; for example, “r” is the word are.

This writing translates as follows: “I ask my dad if he will call a playmate for me.” The writing focuses on a topic and shows an early attempt at writing a sentence.

In this sample, symbols and consonant sounds are used to show that the writer loves her dollhouse. This writing displays individuality, an early example of voice.

Phonetic Writing

In this type of early writing, the child writes words using letters to represent each sound that is heard. Consonants and vowels are used. Some punctuation may also be used.

This writing focuses on a topic and makes sense. The writer shows an awareness of consonant and vowel sounds and uses words and sentences. The art complements the writing.

The writer of this sample uses both consonants and vowels to spell words and write a sentence. The art carries details and demonstrates an emerging voice.

Conventional/Some Phonetic Writing

In this type of writing, the child increasingly writes with conventional spellings and structures. Formation of letters is also more conventional.

This writer focuses on a topic and shows individuality. The writing uses words and sentences appropriately.

The writer’s message makes sense and shows an understanding of the friendly letter. The writing exhibits the appropriate use of words and sentences.

Early childhood literacy

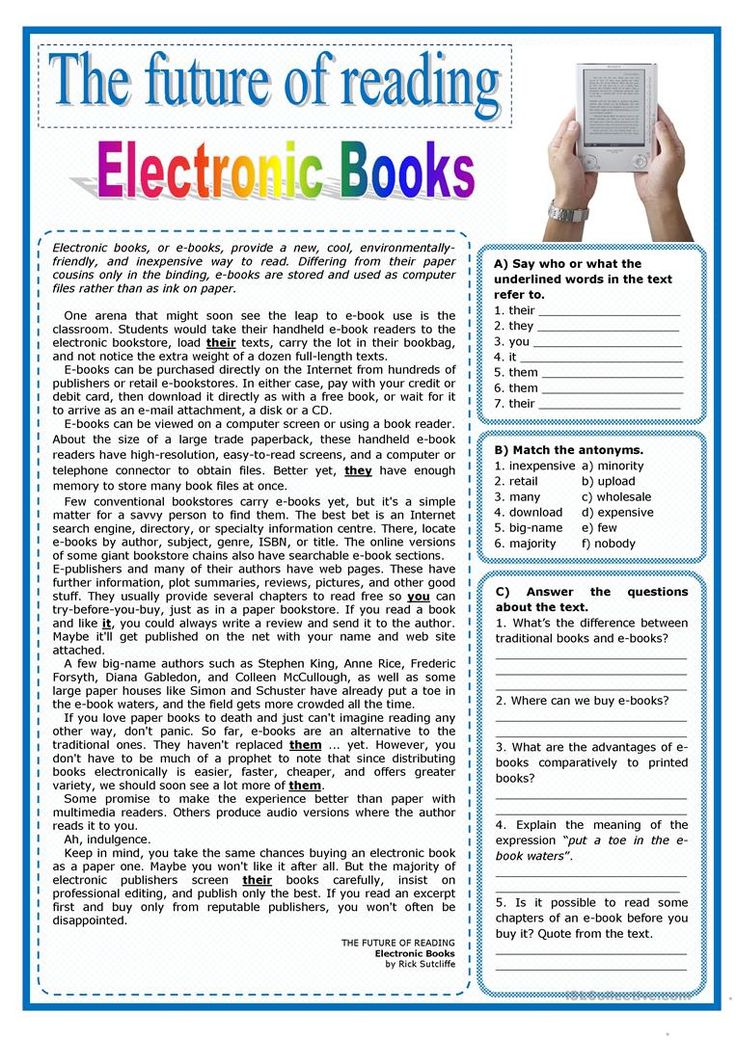

Preschoolers learn a lot about written language long before they learn to read and write in traditional ways. And this is quite natural: children live in a world full of written symbols. Every day they observe and themselves take part in various activities related to books, calendars, lists and inscriptions. Gradually, they learn to understand how written symbols convey meaning. Children's active efforts to develop literacy skills through informal experiences are called emergent literacy. nine0003

Younger preschoolers look for familiar elements of written speech when they “read” fairy tales that they remember and recognize familiar inscriptions. However, they do not yet understand the symbolic function of the printed word. Many preschool children believe that one letter stands for a whole word. At first, they do not even distinguish between drawing and writing. Around the age of four, some of the distinctive features of block text appear in their writing, such as the alignment of figures. However, at the same time, children often use drawing elements - for example, write the word "sun" with a yellow felt-tip pen or draw it in the form of a circle. They express their understanding of the symbolic function of drawings in the “drawing” of letters. nine0003

However, at the same time, children often use drawing elements - for example, write the word "sun" with a yellow felt-tip pen or draw it in the form of a circle. They express their understanding of the symbolic function of drawings in the “drawing” of letters. nine0003

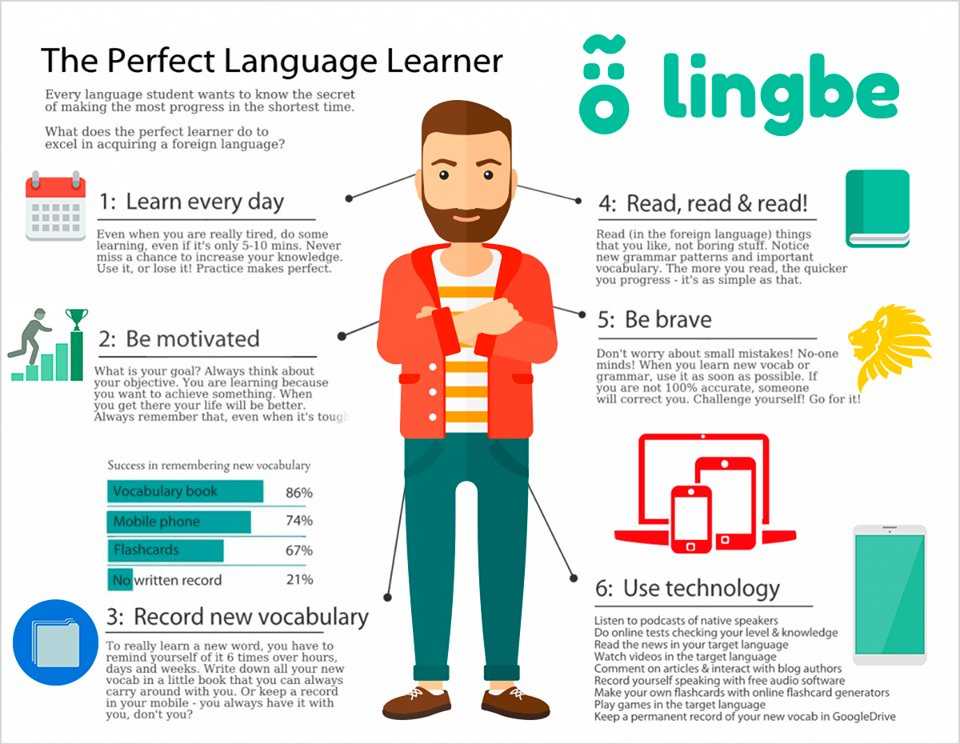

The development of literacy skills is based on speaking and knowledge of the world around. Over time, children's progress in language acquisition and literacy skills begin to support each other. Phonological awareness, that is, the ability to analyze and use the sound structure of colloquial speech, which is evidenced by sensitivity to changes in the sounds that make up words, as well as to rhyme and mispronunciation, is considered an indicator of advanced emergent literacy. Combined with an understanding of the correspondences between sounds and letters, this ability allows children to isolate fragments of speech and associate them with the corresponding written characters. Vocabulary and grammatical knowledge also play an important role in this process. In the course of story conversations between an adult and a child, various speech skills are improved, which are of great importance for the development of literacy. nine0003

In the course of story conversations between an adult and a child, various speech skills are improved, which are of great importance for the development of literacy. nine0003

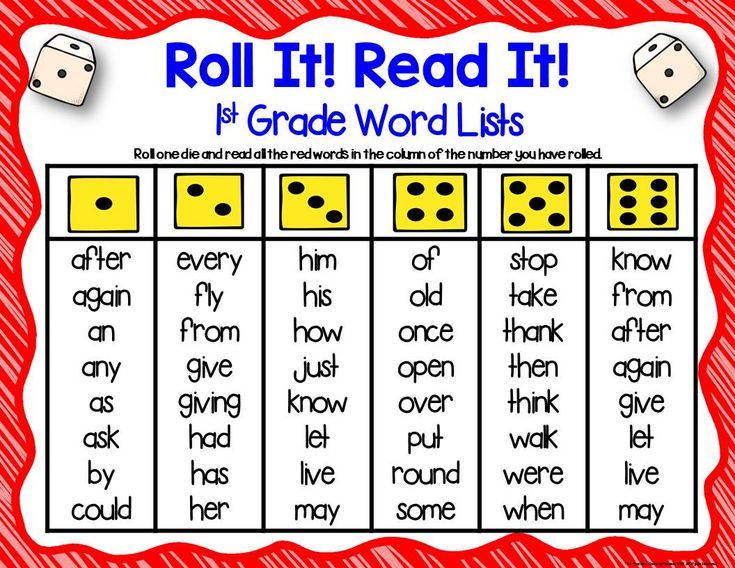

The more informal opportunities for learning literacy skills that preschool children have, the better their speech and emergent literacy, and subsequently their reading skills, are developed. By drawing children's attention to the fact that letters stand for sounds, by playing games with speech and sounds, adults increase children's awareness of the sound structure of speech and how it is displayed in written text. Interactive reading and discussion of the content of the book with preschoolers stimulates different aspects of the development of speech and literacy skills. Children benefit greatly from adult help with writing assignments in the form of a composition, such as writing a letter or a story. nine0003

Read about how to support self-learning in early childhood literacy in the Idea Fair section.

Based on materials from the book "Child Development" by Laura Burke.

EMERGENT EVOLUTION | it's... What is EMERGENENT EVOLUTION?

(emergent evolution) (English emergent - suddenly emerging, from Latin emergo - appear, arise) - a concept that considers development as a leap process, with -rum, the emergence of new, higher qualities (emergents) is due to the intervention of unknowable, ideal forces. The term was first used by J. Lewis (see "Questions about life and spirit" - "Problems of life and mind", v. 2, L., 1875, p. 412). The form of the expanded concept of E. e. acquired in the works of S. Alexander ("Space, time and deity" - "Space, time and deity", L., 1927) and English. biologist and philosopher C. Lloyd-Morgan ("Emergent evolution" - "Emergent evolution", L., 1927). In contrast to the mechanistic the theory of reducing the qualities of E. e. distinguishes between two types of changes: quantitative - "resultants", the nature of which can be determined "a priori", and qualitative - "emergents", not caused by c. -l. material changes and not reducible to the original qualities; the latter are declared scientifically inexplicable "simple qualities". E. e. is a kind of doctrine about the layers of being - "levels of existence" (levels of existence), qualitatively different from each other and irreducible to each other. The number of levels varies from three (matter, life, psyche) in Morgan to several. dozens from J.P. Conger. The lower level provides only the conditions for the emergence of the higher, but does not act as its cause, but rather depends on it. At the same time, materiality (according to Alexander and others) is recognized as the second stage of evolution in relation to space-time. nine0003

-l. material changes and not reducible to the original qualities; the latter are declared scientifically inexplicable "simple qualities". E. e. is a kind of doctrine about the layers of being - "levels of existence" (levels of existence), qualitatively different from each other and irreducible to each other. The number of levels varies from three (matter, life, psyche) in Morgan to several. dozens from J.P. Conger. The lower level provides only the conditions for the emergence of the higher, but does not act as its cause, but rather depends on it. At the same time, materiality (according to Alexander and others) is recognized as the second stage of evolution in relation to space-time. nine0003

The driving force of E. e. some ideal forces turn out to be, which gives E. e. teleological character. For Morgan, "... the recognition of God is the ultimate philosophical explanation that complements the scientific interpretation" ("Emergent evolution", L., 1927, p. 9). Alexander sees the driving force of E. e. in "nisus" (lat. nisus - impulse, aspiration) as aspiration for something higher, not yet achieved and identified with the deity as the driving force and goal of development. In this E. e. akin to "creative evolution" by Bergson, "holism" by Smuts, and other concepts (see Organismic Theories). nine0003

e. in "nisus" (lat. nisus - impulse, aspiration) as aspiration for something higher, not yet achieved and identified with the deity as the driving force and goal of development. In this E. e. akin to "creative evolution" by Bergson, "holism" by Smuts, and other concepts (see Organismic Theories). nine0003

Some Amer. philosophers (Sellers, Montague, Lovejoy) E. e. receives a materialistic interpretation. They see in "emergence" an expression of the "intrinsic dynamism" of nature, "... a change in the state of a substantial system, the birth of a new condition" (Sellers R.W., Philosophy of physical realism, N. Y., 1932, p. 334). However, the rejection of the idealistic interpretations of E. e. does not go beyond the abstract recognition of the self-movement of nature.

Lit.: Cornforth M., Opponents of idealism in modern times. English bourgeois philosophy, "VF", 1955, No 4; his, Answer to letters from readers ..., ibid., 1957, No 1; Bogomolov A.S., The idea of development in the bourgeois. philosophy of the 19th and 20th centuries, M., 1962, ch. 5, 8, concluding; Morgan C. L., Life, mind and spirit, N. Y., 1925; Lovejoy A. Ο., Meanings of "emergence" and its modes, "J. of Phil. Studies", 1927, v. 2, no 6; MacDougall., Modern materialism and emergent evolution, N. Y., 1929; Reiser O. L., Mathematics and emergent evolution, "The Monist", 1930, No 4; Le Boutilier C., Religious values in the philosophy of emergent evolution, N. Y., 1936; Ablowitz R., The theory of emergence, "Phil. of Science", 1939, v. 6, no 1; Henle P., The status of emergence, "J. of Phil.", 1942, v. 39, No 18; Ostoya, P., Les theories de l'évolution, P., 1951; Pap A., The concept of absolute emergence, "Brit. J. for the Phil, of Sciences", 1952, v. 2, No. 8; Nagel, E., The structure of science, N. Y., 1961, p. 366–80. See also lit. at Art. Alexander, Sellars, Montague.

philosophy of the 19th and 20th centuries, M., 1962, ch. 5, 8, concluding; Morgan C. L., Life, mind and spirit, N. Y., 1925; Lovejoy A. Ο., Meanings of "emergence" and its modes, "J. of Phil. Studies", 1927, v. 2, no 6; MacDougall., Modern materialism and emergent evolution, N. Y., 1929; Reiser O. L., Mathematics and emergent evolution, "The Monist", 1930, No 4; Le Boutilier C., Religious values in the philosophy of emergent evolution, N. Y., 1936; Ablowitz R., The theory of emergence, "Phil. of Science", 1939, v. 6, no 1; Henle P., The status of emergence, "J. of Phil.", 1942, v. 39, No 18; Ostoya, P., Les theories de l'évolution, P., 1951; Pap A., The concept of absolute emergence, "Brit. J. for the Phil, of Sciences", 1952, v. 2, No. 8; Nagel, E., The structure of science, N. Y., 1961, p. 366–80. See also lit. at Art. Alexander, Sellars, Montague.

A. Bogomolov. Moscow.

Philosophical Encyclopedia. In 5 volumes - M .: Soviet Encyclopedia.