What is fluency

Fluency | Reading Rockets

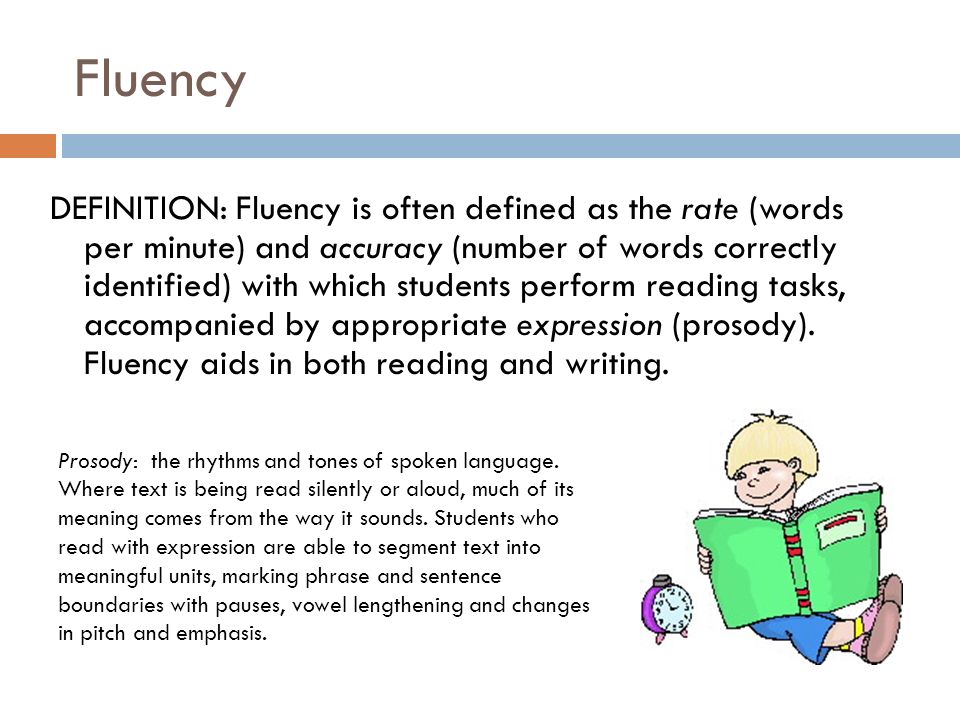

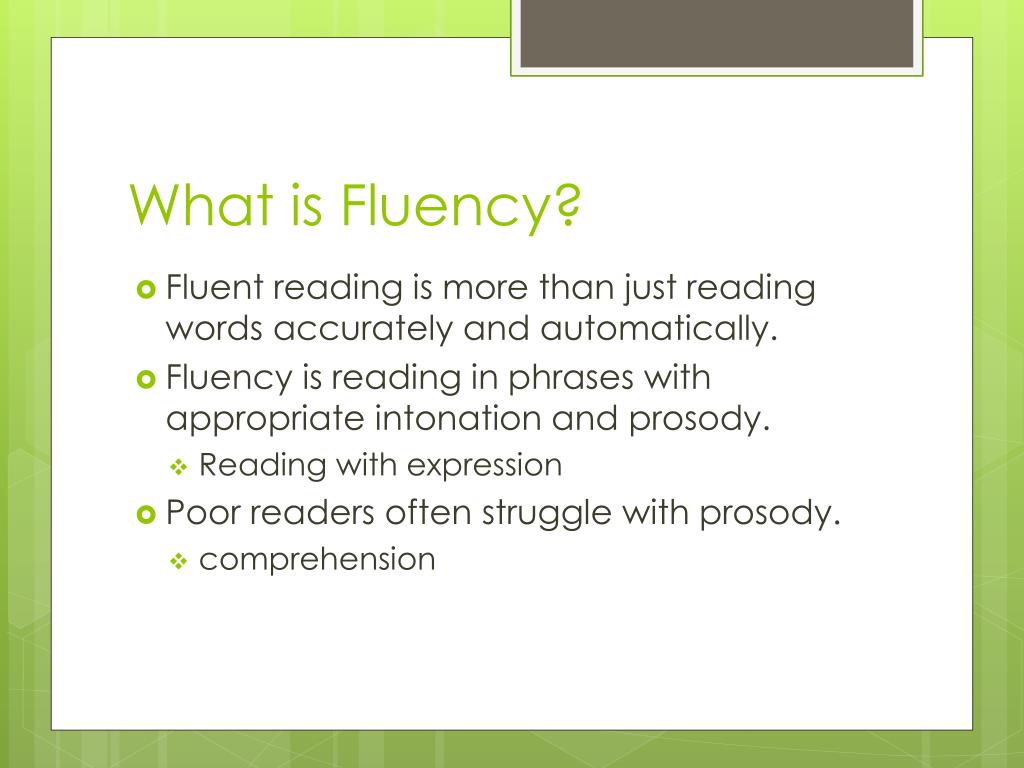

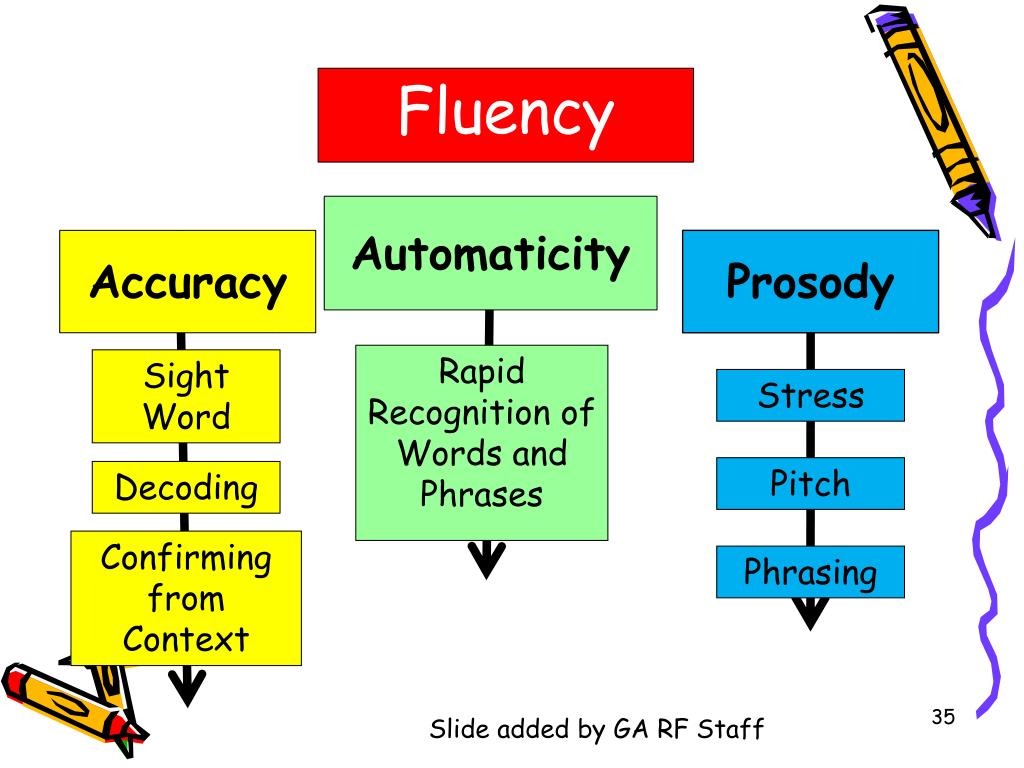

Fluency is defined as the ability to read with speed, accuracy, and proper expression. In order to understand what they read, children must be able to read fluently whether they are reading aloud or silently. When reading aloud, fluent readers read in phrases and add intonation appropriately. Their reading is smooth and has expression.

Children who do not read with fluency sound choppy and awkward. Those students may have difficulty with decoding skills or they may just need more practice with speed and smoothness in reading. Fluency is also important for motivation; children who find reading laborious tend not to want read! As readers head into upper elementary grades, fluency becomes increasingly important. The volume of reading required in the upper elementary years escalates dramatically. Students whose reading is slow or labored will have trouble meeting the reading demands of their grade level.

What the problem looks like

A kid's perspective: What this feels like to me

Children will usually express their frustration and difficulties in a general way, with statements like "I hate reading!" or "This is stupid!". But if they could, this is how kids might describe how fluency difficulties in particular affect their reading:

- I just seem to get stuck when I try to read a lot of the words in this chapter.

- It takes me so long to read something.

- Reading through this book takes so much of my energy, I can't even think about what it means.

A parent's perspective: What I see at home

Here are some clues for parents that a child may have problems with fluency:

- He knows how to read words but seems to take a long time to read a short book or passage silently.

- She reads a book with no expression.

- He stumbles a lot and loses his place when reading something aloud.

- She reads aloud very slowly.

- She moves her mouth when reading silently (subvocalizing).

A teacher's perspective: What I see in the classroom

Here are some clues for teachers that a student may have problems with fluency:

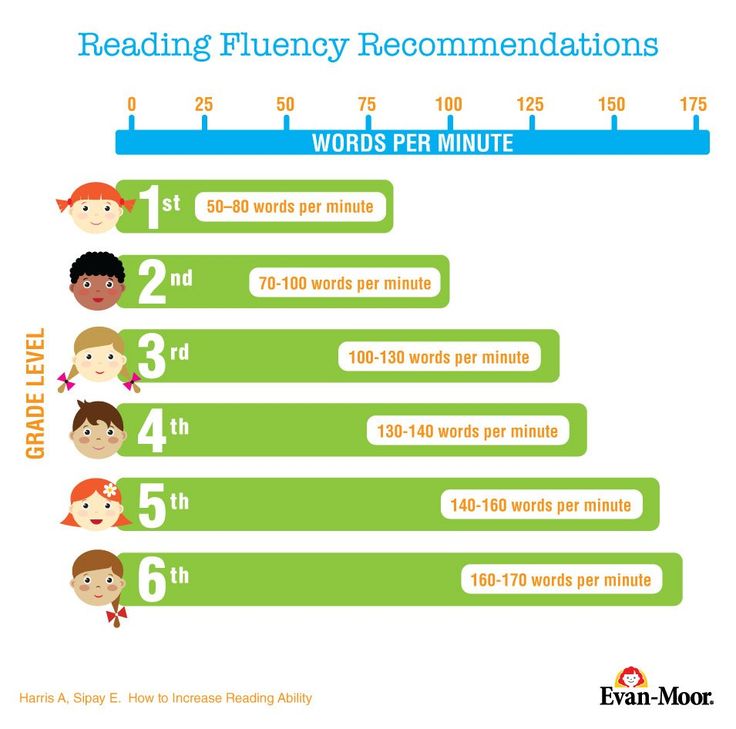

- Her results on words-correct-per-minute assessments are below grade level or targeted benchmark.

- She has difficulty and grows frustrated when reading aloud, either because of speed or accuracy.

- He does not read aloud with expression; that is, he does not change his tone where appropriate.

- She does not "chunk" words into meaningful units.

- When reading, he doesn't pause at meaningful breaks within sentences or paragraphs.

How to help

With the help of parents and teachers, kids can learn strategies to cope with fluency issues that affect his or her reading. Below are some tips and specific things to do.

What kids can do to help themselves

- Track the words with your finger as a parent or teacher reads a passage aloud.

Then you read it.

Then you read it. - Have a parent or teacher read aloud to you. Then, match your voice to theirs.

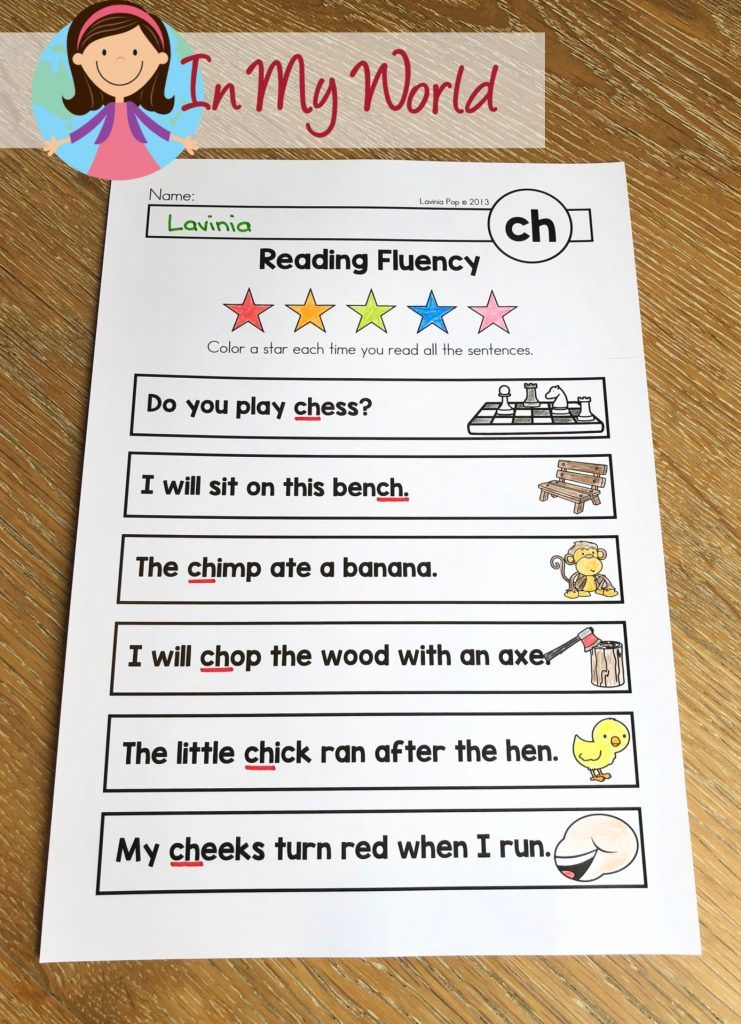

- Read your favorite books and poems over and over again. Practice getting smoother and reading with expression.

What parents can do to help at home

- Support and encourage your child. Realize that he or she is likely frustrated by reading.

- Check with your child's teachers to find out their assessment of your child's word decoding skills.

- If your child can decode words well, help him or her build speed and accuracy by:

- Reading aloud and having your child match his voice to yours

- Having your child practice reading the same list of words, phrase, or short passages several times

- Reminding your child to pause between sentences and phrases

- Read aloud to your child to provide an example of how fluent reading sounds.

- Give your child books with predictable vocabulary and clear rhythmic patterns so the child can "hear" the sound of fluent reading as he or she reads the book aloud.

- Use books on tapes; have the child follow along in the print copy.

What teachers can do to help at school

- Assess the student to make sure that word decoding or word recognition is not the source of the difficulty (if decoding is the source of the problem, decoding will need to be addressed in addition to reading speed and phrasing).

- Give the student independent level texts that he or she can practice again and again. Time the student and calculate words-correct-per-minute regularly. The student can chart his or her own improvement.

- Ask the student to match his or her voice to yours when reading aloud or to a tape recorded reading.

- Read a short passage and then have the student immediately read it back to you.

- Have the student practice reading a passage with a certain emotion, such as sadness or excitement, to emphasize expression and intonation.

- Incorporate timed repeated readings into your instructional repertoire.

- Plan lessons that explicitly teach students how to pay attention to clues in the text (for example, punctuation marks) that provide information about how that text should be read.

More information

Find out more about fluency issues with these resources:

< previous | next >

Top Articles

Especially for Parents

Research Briefs

What Is Fluency? Why Is Fluency Important? :: Read Naturally, Inc.

What Is Fluency?

Fluency is the ability to read "like you speak." Hudson, Lane, and Pullen define fluency this way: "Reading fluency is made up of at least three key elements: accurate reading of connected text at a conversational rate with appropriate prosody or expression." Non-fluent readers suffer in at least one of these aspects of reading: they make many mistakes, they read slowly, or they don't read with appropriate expression and phrasing.

Developing reading fluency with Read Naturally Strategy programs

Key Concepts

Why Is Fluency Important?

For many years, educators have recognized that fluency is an important aspect of reading. Reading researchers agree. Over 30 years of research indicates that fluency is one of the critical building blocks of reading, because fluency development is directly related to comprehension.

Here are the results of one study by Fuchs, Fuchs, Hosp, and Jenkins that shows how oral reading fluency correlates highly with reading comprehension.

| Measure | Validity Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Oral Recall/Retelling | .70 |

| Cloze (fill in the blank) | .72 |

| Question Answering | .82 |

| Oral Reading Fluency | .91 |

To interpret this type of correlation data, consider that a perfect match would be 1. 0. As you can see, oral recall/retelling, fill in the blank, and question answering are all above 0.6, which indicates there is a strong correlation. But oral reading fluency is by far the strongest, with a .91 correlation.

0. As you can see, oral recall/retelling, fill in the blank, and question answering are all above 0.6, which indicates there is a strong correlation. But oral reading fluency is by far the strongest, with a .91 correlation.

Many researchers, including Breznitz, Armstrong, Knupp, Lesgold, and Pinnell, have found that fluency is highly correlated with reading comprehension—that is, when a student reads fluently, that student is likely to comprehend what he or she is reading.

Why are reading fluency and reading comprehension so highly correlated? Dr. S. Jay Samuels, a professor and researcher well known for his work in fluency, put forth a theory called the automaticity theory. According to Dr. Samuels, people have a limited amount of mental energy. If you want to multitask or to become proficient at a complex task such as reading, you first need to master the component tasks so you can do them automatically. For example, a reader who must focus his or her attention on decoding words may not have enough mental energy left over to think about the meaning of the text. However, a fluent reader who can automatically decode the words can instead give full attention to comprehending the text. To become proficient readers, our students need to become automatic with text so they can pay attention to the meaning.

However, a fluent reader who can automatically decode the words can instead give full attention to comprehending the text. To become proficient readers, our students need to become automatic with text so they can pay attention to the meaning.

See also:

- Determining who needs fluency instruction

- Hasbrouck-Tindal oral reading fluency norms

- Video: Why reading fluency is important

Challenges Faced by Non-Fluent Readers

Students become fluent by reading. Some students learn to read fluently without explicit instruction. For others, however, fluency doesn't develop in the course of normal classroom instruction.

Research analyzed by the National Reading Panel suggests that just encouraging students to read independently isn't the most effective way to improve reading achievement. Too often, simply encouraging at-risk students to read doesn't result in increased reading on their part. During sustained silent reading, at-risk readers may get a book with mostly pictures and look at the pictures, or they choose a difficult book so they will look like everyone else and then pretend to read.

Even if at-risk students do read, they read more slowly than the other students. In a 10-minute reading period, a proficient reader who reads 200 words a minute silently could read 2,000 words. In the same 10 minutes, an at-risk student who reads 50 words a minute would only read 500 words. This is equal reading time but certainly not an equal number of words read.

These students need to read more, but just asking them to read on their own often doesn't work. The National Reading Panel has concluded that a more effective course of action is for us to explicitly teach developing readers how to read fluently, step by step.

Research-Proven Fluency Strategies

How do we explicitly teach students to read fluently? The National Reading Panel found data supporting three strategies that improve fluency, comprehension, and reading achievement—teacher modeling, repeated reading, and progress monitoring.

Teacher Modeling

The first strategy is teacher modeling. Research demonstrates that various forms of modeling can improve reading fluency. Examples of teacher modeling include:

Research demonstrates that various forms of modeling can improve reading fluency. Examples of teacher modeling include:

- Teacher-assisted reading

- Peer-assisted reading

- Audio-assisted reading

Teacher modeling involves more than just listening to someone else read. Students must be actively involved 100 percent of the time and in a multisensory way.

Teacher modeling teaches word recognition in a meaningful context, demonstrates correct phrasing, and gives students practice tracking across the page. A child can benefit from teacher modeling once he or she knows at least 50 sight words and has a good sense of beginning sounds.

The reading rate of the model reader is important. Christopher Skinner, a reading researcher, found that students who read lists of words with him slowly were more fluent with the words than students who read with him at a faster rate. The slower rate enables students to learn new words and clarify difficult words. As students learn more words, they naturally become more fluent.

As students learn more words, they naturally become more fluent.

Another form of modeling is the neurological impress method. In the neurological impress method, a proficient and a struggling reader read together from a passage, with the more able reader reading near the rate of the struggling reader. Heckelman (1969) showed that after 29 15-minute sessions, 24 seventh- through ninth-grade boys, who were an average of 3 years behind in reading, gained an average of 1.9 years in reading based on the Oral Gilmore and the California Achievement Test.

Repeated Reading

Another technique that research has shown significantly builds reading fluency is repeated reading. In fact, the National Reading Panel says this is the most powerful way to improve reading fluency. This involves simply reading the same material over and over again until accurate and expressive.

In the 1970s, LaBerge and Samuels studied what happens when students read passages over and over again. They found that when students reread passages, they got faster at reading the passages, understood them better, and were able to read subsequent passages better as a result of the repeated reading.

They found that when students reread passages, they got faster at reading the passages, understood them better, and were able to read subsequent passages better as a result of the repeated reading.

Repeated reading is a form of mastery learning. The students read the same words so many times that they begin to know them and are able to identify them in other text. Besides helping students bring words to mastery, repeated reading changes the way students view themselves in relation to the act of reading.

Progress Monitoring

People who play video games are presented with a specific goal and with immediate, relevant feedback about their progress toward that goal. This combination of having a goal and getting feedback on progress can be very motivating.

Progress monitoring takes advantage of this combination to motivate students to read. You give students a specific, individual reading goal, and you tell them exactly how you're going to know they've met it. Then, you give them the means to measure how they're doing. Finally, you make it simple enough that they'll know they've met their goal even before you do. This progress monitoring is what motivates students to practice reading the same story over and over until achieving mastery.

Then, you give them the means to measure how they're doing. Finally, you make it simple enough that they'll know they've met their goal even before you do. This progress monitoring is what motivates students to practice reading the same story over and over until achieving mastery.

Developing Reading Fluency With Read Naturally Strategy Programs

The research-based Read Naturally Strategy combines these three strategies into highly effective programs that accelerate reading achievement. Students become confident readers by developing fluency, phonics skills, comprehension, and vocabulary while reading leveled text. The time-tested intervention programs engage students with interesting nonfiction stories and yield powerful results.

Learn more about the Read Naturally Strategy

Research basis for the Read Naturally Strategy

The Read Naturally Strategy is available in a variety of formats:

Choosing the right Read Naturally Strategy program

| One Minute Reader® Structured, supplemental reading program for developing literacy skills independently.  Available in these formats: Available in these formats:One Minute Reader Live (component of web-based Read Live for supplemental reading at school) One Minute Reader books/audio CDs (for a school-to-home checkout program) |

Bibliography

Armstrong, S. W. (1983). The effects of material difficulty upon learning disabled children's oral reading and reading comprehension. Learning Disability Quarterly, 6, pp. 339–348.

Breznitz, Z. (1987). Increasing first graders' reading accuracy and comprehension by accelerating their reading rates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(3), pp. 236–242.

Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins, J. R. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(3), pp. 239–256.

Heckelman, R. G. (1969). A neurological-impress method of remedial-reading instruction. Academic Therapy Quarterly, 5(4), pp. 277–282.

277–282.

Hudson, R. F., H. B. Lane, and P. C. Pullen. (2005). Reading fluency assessment and instruction: What, why, and how. Reading Teacher 58(8), pp. 702-714.

Knupp, R. (1988). Improving oral reading skills of educationally handicapped elementary school-aged students through repeated readings. Practicum paper, Nova University (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 297275).

LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6, pp. 292–323.

Lesgold, A., Resnick, L. B., & Hammond, K. (1985). Learning to read: A longitudinal study of word skill development in two curricula. In G. Waller & E. MacKinon (eds.), Reading research: Advances in theory and practice. New York, NY: Academic Press.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Pinnell, G. S., Pikulski, J. J., Wixson, K. K., Campbell, J. R., Gough, P. B., & Beatty, A. S. (1995). Listening to children read aloud: Data from NAEP's integrated reading performance record (IRPR) at grade 4 (NCES Publication 95-726). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics.

Samuels, S. J. (2002). Reading fluency: Its development and assessment. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction, 3rd ed., pp. 166–183. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Samuels, S. J. (1997). The method of repeated readings. The Reading Teacher, 50(5), pp. 376–381.

Samuels, S. J. (2006). Towards a model of reading fluency. In S. J. Samuels and A. E. Farstrup (eds.), What research has to say about fluency instruction. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Samuels, S. J. (1997). The method of repeated readings. The Reading Teacher, 50(5), pp. 376–381.

Skinner, C. H., Logan, P., Robinson, S. L., & Robinson, D. H. (1997). Demonstration as a reading intervention for exceptional learners. School Psychology Review, 26(3), pp. 437–447.

What does fluency mean - Meanings of words

fluency in the crossword dictionary

fluency

- rapidity of fire

- handwriting property

- Reading agility

- Speed, non-stop

- In linguistics: property of the vowel

- Abstract noun according to the meaning of the adjective: fluent

Explanatory dictionary of the Russian language.

D.N. Ushakov

D.N. Ushakov fluency

fluency, pl. no, w. Distraction noun to fluent in 4 digits. To play the piano, you need to develop finger fluency. Fingers gave obedient, dry fluency. Pushkin.

New explanatory and derivational dictionary of the Russian language, T. F. Efremova.

fluency

f. Distraction noun by value adj.: fluent (2*2-4).

Examples of the use of the word fluency in the literature.

The second plot, developed in some detail, while maintaining relative independence, performs an auxiliary function in the work, which is confirmed by some fluency, schematism, bareness of its disclosure and the use of faded tropes - as opposed to the brightly individualized author's comparisons in the first part of the story.

That is why Yarra, it seems, still could not achieve fluency in ancestral science and almost did not take part in compiling a letter to Pankel, nicknamed Blue Ice, who lived in the hillside at the mouth of the Poteshka.

In addition, when referring to a newspaper or book text, it is always possible to check not only the speed and fluency of reading, but also the quality of reading comprehension by retelling its content.

The sixty-year-old Versailles virtuoso has already lost his former hand fluency in the game.

Let us forgive the fluency of the current hours, After all, it is given to them to enlighten us with reading - Only such an hour I am ready to call the best.

For all their comforting fluency, they left him free to think about the short man and other frightened people who visited Zia.

In any case, obviously, it makes sense to measure the fluency and meaningfulness of children's reading before turning to tongue twisters and 2-3 months after optional exercises with them.

Harry, boy, I've always said this and now I say: you have more fluency than Paganini and Gigli put together.

The children were also dressed appropriately for the occasion - full copies of adults, in camisoles and capes - and even the smallest chattered in the language of the League with the usual fluency of elders, only their speech sounded more natural.

Barnard asked for his opinion, and he launched into explanations with the fluency that a university professor might have in interpreting a problem.

His monologue continued with an impromptu fluency that, despite its sincerity, was mainly aimed at creating and adjusting the atmosphere.

For a moment the whispering stopped, and Conway, shifting a little, thought that the Highest of the Lamas was translating with fluency from a distant private dream.

This conversation, of course, was not distinguished by fluency, but it was enough to -- to understand each other.

Potokin, not realizing this, translated automatically, with the fluency of a diligent boy from the language group.

The Weimar guest impressed with the unprecedented depth and fluency of the performance on the harpsichord of the most difficult compositions - his own and German composers revered by Bach.

Source: Maxim Moshkov Library

Fluency

July 10, 2015 Tags: pronunciation, speaking, audio, video

You probably noticed that many companies in their vacancies indicate "fluent English". Where is he running, dear?))

And for sure everyone who studies English, seeks to improve fluency. No one is satisfied with "be" and "me"))

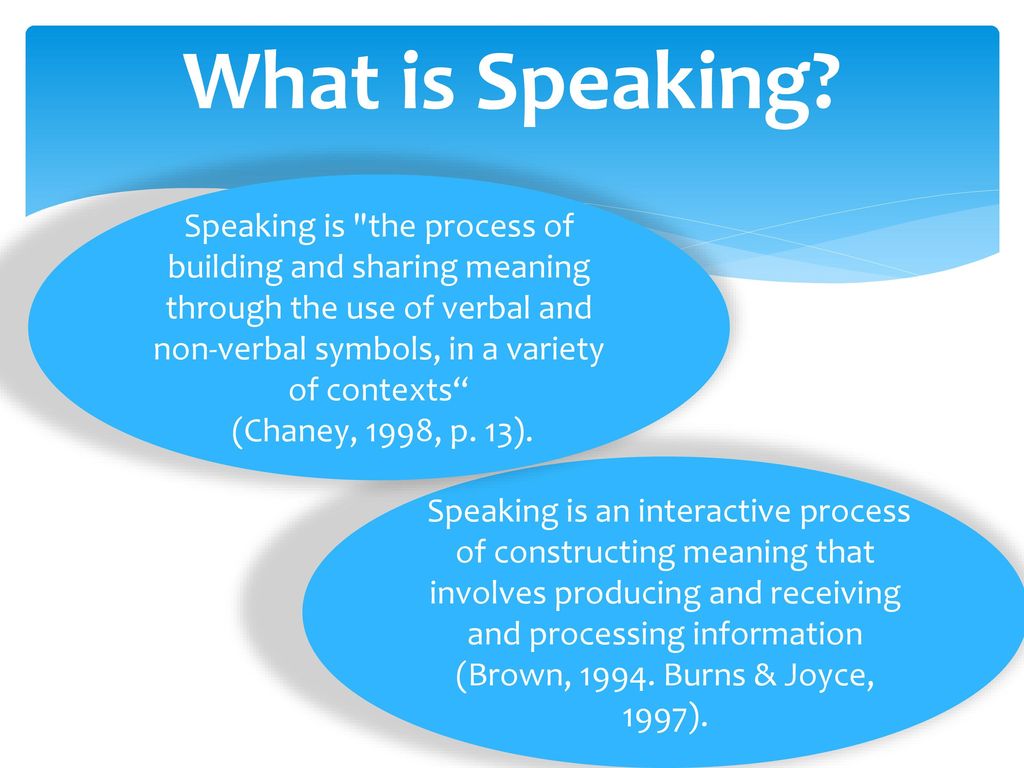

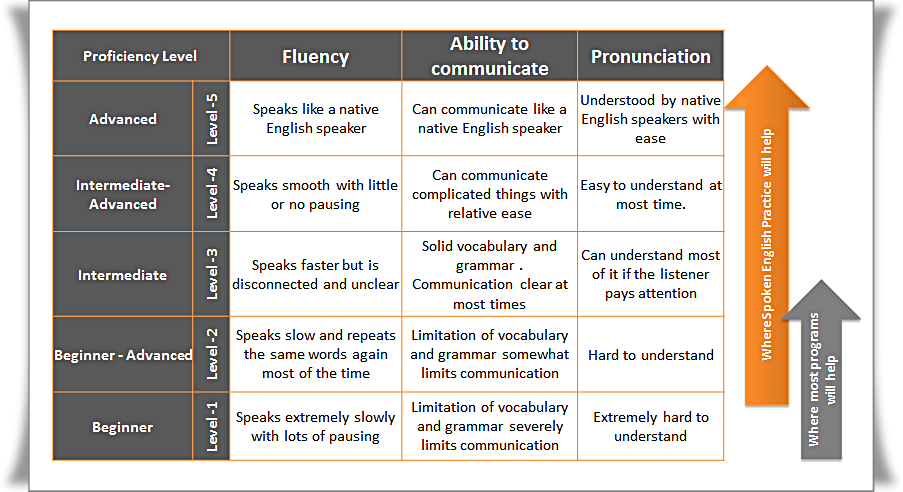

What is fluency? What speech is perceived as fluent? Fluency Are speech and speed the same thing? Does this require correctness, the absence of errors? And how can fluency be developed?

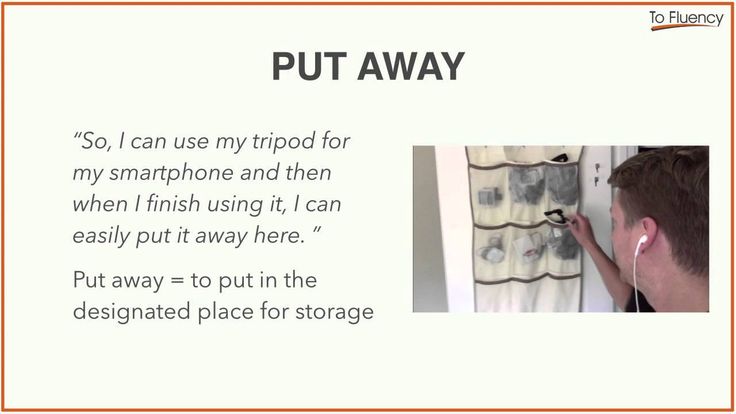

Fluency and speed

Is fluency the same as speed? Yes and no. Speed, of course, plays a role, but not the only and not even the most important.

You can speak quickly, but make a lot of pauses. And if these pauses are also in the wrong places - that's it, write it down. This is no longer fluency of speech.

Fluency and correctness or fluency vs. Accuracy

I must say that this is an important division in teaching methods languages, colleagues will not let you lie. It is believed that there is a time to collect stones fluency exercises, and there are exercises for correctness (accuracy).

So, correctness and absence of errors is, of course, Great. But, again, fluency is not yet guaranteed. Here is an example:

The comrade says everything is correct, but his speech is not perceived fluent. Why?

He pauses too many times, sometimes in strange places like would break the semantic group. It also looks like he speaks in separate words, while trying to figure out how to connect them.

All this creates the impression of a lack of fluency. me personally even somehow painful to listen to this monologue. It makes you want to say, ‘Come on, dude! Spit it out'))

It makes you want to say, ‘Come on, dude! Spit it out'))

What kind of speech perceived as fluent

If speed and absence of errors are not yet a guarantee, why then fluency of speech develops? What kind of speech do we perceive as fluent?

The main factor is the pauses. Their frequency, relevance and completeness.

Frequency of pauses

Pauses in speech - in any language, including native - are inevitable. From time to time you need to stop to get some air. Sometimes you gotta give take a few seconds to formulate your idea more precisely.

And that's perfectly normal. But there shouldn't be too many pauses. a lot of. Otherwise - goodbye, youth fluency.

Arrangement of pauses

In addition to the number of pauses, their placement in the correct places.

Read this sentence with the pauses marked vertical bar - |

Unlike organic | pauses unnatural pauses | smash semantic | group.

Do you hear how difficult it is to accept this offer? All because the pauses are placed unnaturally, right in the middle of a phrase that is one semantic entity.

It would be much more natural to say this:

Unlike organic pauses | unnatural pauses | smash semantic group.

Phrases

To avoid too many pauses, you need to speak in phrases (lexical chunks), not individual words. To speak in phrases, you need a vocabulary (moreover, phrasal!) and grammar brought to automatism.

Speech - of those - who - speaks - in separate - words - as - in - this - example, will not be perceived as a fluent, even despite the absence errors.

There are also extreme examples of fluency))

Have you ever seen how an auction works? Did you hear the host? What about sports commentators? And those and others chattering at a terrifying speed - unless, of course, they are not beginners.

Do you know why So? Because they've said it all a million times previous broadcasts and auctions. They don't have to assemble the statement from scratch each time. They use ready-made pieces (chunks), repeated before countless times.