When does pretend play start

Stages of Play from 24–36 Months: The World of Imagination

Learn how infants and toddlers develop play skills from birth to 3, and what toys and activities are appropriate for their age.

From age 2 to 3, your toddler’s interests and skills are blooming at an amazing, almost dizzying rate! All the new things they can do—from walking and talking to figuring out how things work and beginning to make friends—are fuel for the imagination and creativity. This is a special time in your child’s life. Learn more about how infants and toddlers develop play skills. And don’t forget—YOU are still their most important playmate and toy!

Playing Pretend

Between 2 and 3, your toddler will use their growing thinking skills to play pretend. With props, like a doll and toy bottle, she will act out steps of a familiar routine—feeding, rocking, and putting a doll to sleep. As your toddler learns to use symbols, imaginary play skills will grow more complex. A round pillow, for example, can become a yummy pizza!

TOYS TO EXPLORE:

- Stuffed animals and dolls

- Accessories such as baby blanket, bottle for doll, etc.

- Toy dishes, pots and pans, pretend food

- Toy cars, trucks, bus, or train, with little people that fit inside

- Blocks

HELPING YOUR TODDLER PLAY AND LEARN:

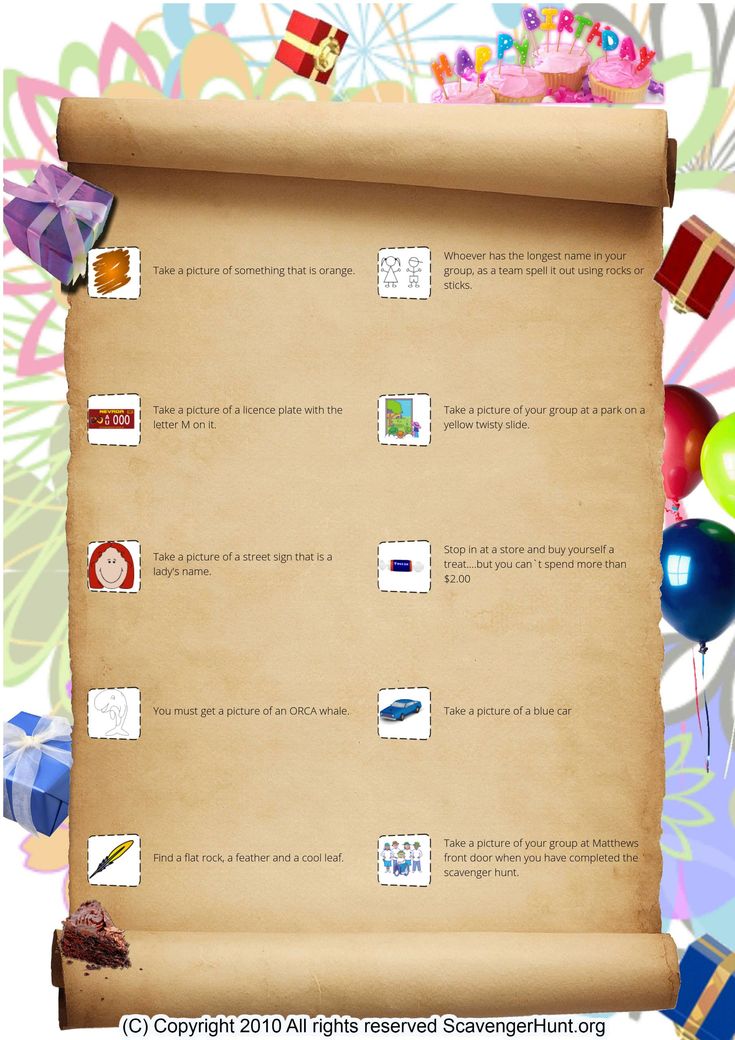

- Let your child choose what to play, and then add on to his activity. If they have a toy bus, you might ask where it’s going or if they would like to pick up some people waiting at the bus stop.

- Give your child a block and say, “Do you want a piece of my birthday cake? It’s so yummy!” (as you pretend to munch on it). Do they understand the block can stand in for something else? If so, have a birthday party using the block as a cake, sing a birthday song, pretend to blow the candles out, and “cut” a slice to eat.

Solving Problems Through Play

Sorting toys—putting cars in one basket and balls in another—is just one way that your toddler is solving problems using thinking skills. You may also see them try one puzzle piece in different spaces, or turn it around to see if it fits. Your child is now also using tools (like a stick) to solve problems (how to reach a toy under the couch).

Your child is now also using tools (like a stick) to solve problems (how to reach a toy under the couch).

TOYS TO EXPLORE:

- Chunky puzzles

- Memory-type games

- Stacking cups or ring stacks

- Shape-sorters and bead mazes

- Toys that can be activated—like cars that roll forward when you pull them back

HELPING YOUR TODDLER PLAY AND LEARN:

- Make your own Memory game using photos of family members. Print out two copies of 10 photos, glue each photo to an index card. Place them face up on the floor and see if your child can find the matches.

- Turn cleaning up into a sorting game. Take photos of your child’s different toys and tape them to the basket or box where they belong. Show your child how to sort her toys. Before you know it, they’ll be an expert at the “clean-up game”!

Now You’re Talking!

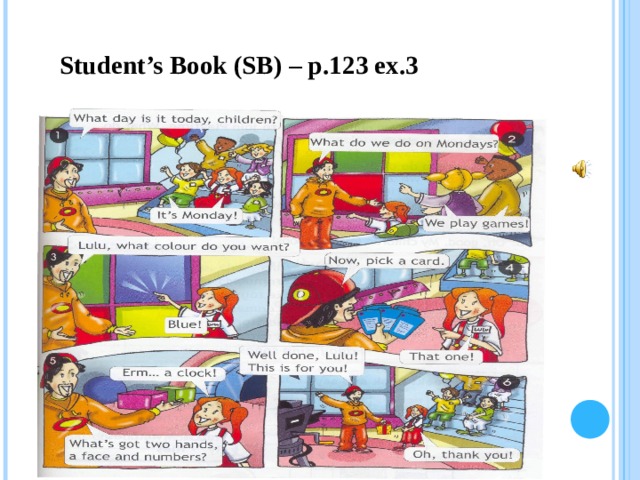

Toddlers are learning new words by the day! Most are using two-word phrases (“what that”) and by age 3, some three-word phrases (“Josie want cookie!”). Toddlers can now follow two-step requests such as “Please get your hat and put it on.” Two-year-olds can also understand stories. They can now connect the words you say with the illustrations.

Toddlers can now follow two-step requests such as “Please get your hat and put it on.” Two-year-olds can also understand stories. They can now connect the words you say with the illustrations.

TOYS TO EXPLORE:

- Board books

- Songs and fingerplays

- Dolls

- Child-safe mirror

HELPING YOUR TODDLER PLAY AND LEARN:

- During bath-time, ask your child to wash his nose and belly. Then ask them to wash his doll’s nose and belly. Look in a mirror together and name the different parts of your faces—eyes, nose, mouth, ears, and more.

- Read together. If your toddler is wiggly, ask them to do the actions on the page—hopping like the frog or dancing like the little mouse. Ask questions, too: “What do you see on this page?” or “Do you see a moon?”

Fantastic Fingers

Your toddler is now able to use his hands and fingers to pick up food, small toys, and more. They may even hold a crayon using his thumb and pointer finger, instead of their fist. Toddlers are learning to control the strokes they make with crayons and markers.

Toddlers are learning to control the strokes they make with crayons and markers.

TOYS TO EXPLORE:

- Foam or wooden blocks, plastic interlocking blocks, or bristle blocks

- Chunky puzzles

- Pull-toys, stringing beads, and pop-beads

- Washable crayons and markers

HELPING YOUR TODDLER PLAY AND LEARN:

- Tape paper to your child’s high chair or to the table and let your child explore with crayons and markers. Watch them scribble away! See if they want to imitate making a line or circles that you draw first. But don’t worry if they have their ideas about what she wants to draw—or how to draw it.

- Play with play-dough. Practice rolling the dough, poking holes in it, or making little balls of dough and dropping them in a small cup to dump out. Older toddlers still like fill-and-dump activities—plus this lets them use their hands and fingers to explore and create.

The 5 Stages of Pretend Play in Early Childhood

- Share

Throughout early childhood, children engage in many types of play that are all equally important for their development. One of these is pretend play

, also known as imaginative, make-believe or fantasy play.

One of these is pretend play

, also known as imaginative, make-believe or fantasy play.

Children typically progress through 5 stages of pretend play.

Pretend play may appear to just be a child imitating what they see around them and how others are behaving, but it stimulates a great deal of creativity and thinking skills.

When children act out their world together, they engage in cooperative behaviour as they work together to create a fantasy scene. This involves high levels of social skills.

They also develop emotionally as they act out life scenarios that are full of emotions and new experiences. Playing gives them a safe space to experience these big emotions.

Here are the 5 stages of imaginative play in early childhood:

1. Enactive Naming

The first phase of pretend play is called enactive naming. In this stage, a child is not yet actively “pretending,” rather she is showing the knowledge she has.

For example, the first time she puts an empty spoon or cup to her mouth, she may be imitating a behaviour she has seen, or acting out her understanding of the objects, but she is not yet playing.

She is beginning to learn the difference between real and not real.

Young children love to imitate the actions and behaviours they see around them and may also want to sweep the floor, whether with a real broom or a toy broom.

2. Autosymbolic Schemes

In the second stage, called autosymbolic schemes, the young child begins to display the first signs of pretending, but only in relation to herself. This starts around the age of 12 months.

A child may pretend to lie down and sleep or take a pretend sip from their cup while making noises to show she is drinking.

At this stage you will see that the child is intending to play by her mannerisms and actions – she may smile or look at you to show you that she is pretending.

Playing with toy replicas of household objects is fun for young toddlers, and by using these items for their correct functions, they show their growing cognitive skills.

At some point, the young child will start to engage in pretend play by using objects to represent other objects. This is called symbolic play.

This means a child who wishes to pretend to talk on the phone, may reach for a block instead of a real phone or a toy that represents the real object.

The child feels that the block shares some characteristics with a phone – perhaps the size and the shape – and it becomes a good replacement for the phone.

This kind of symbolic pretend play shows yet another layer of advanced thinking.

Pretending while playing is rooted in a child’s social development. Their interactions with parents, family, peers and other caregivers forms the basis of their play, and forms the foundation for their cognitive development.

3. Decentred Symbolic Schemes

Between the age of 12 and 24 months, a child will begin to involve others in her pretend play.

She will pass you the cup to take a sip from or try to feed you with an empty spoon. This shows that she is becoming aware of others as being separate from herself.

From around 2 years of age, toddlers often begin to play with dolls. They see their dolls as living beings, with feelings and states, such as hunger and tiredness.

This behaviour shows a huge leap in a child’s thinking skills as she matures.

It is also believed that the advanced thinking shown during pretend play is not yet seen in other aspects of a child’s life at this young age.

During this type of play, a child knows she is pretending and knows that the other child is pretending, and that they are both attaching mental concepts to their scenario.

This type of awareness is unusual as children typically see everything from an egocentric viewpoint.

During pretend play; however, they are able to experience something from someone else’s shoes and even try out different points of view.

Children also show that while engaging in symbolic play they are able to assign two separate identities to an object – such as understanding that a block is a block, and in this case, also a phone.

This is something they are not able to do in other contexts, for example when looking at pictures of objects that represent other objects.

To give an example of this in a language context – a very young child knows that a banana is a banana, but will not also refer to it as a fruit.

Pretend play, therefore, plays a big role in helping a child develop thinking skills.

Even the objects that a child uses to play with show her level of thinking. In the beginning, she uses real objects, then toy replicas, then other objects as representations.

The older a child gets, the more she can use non-realistic toys in her play, with her imagination being the only thing she needs.

4. Sequencing Pretend Acts

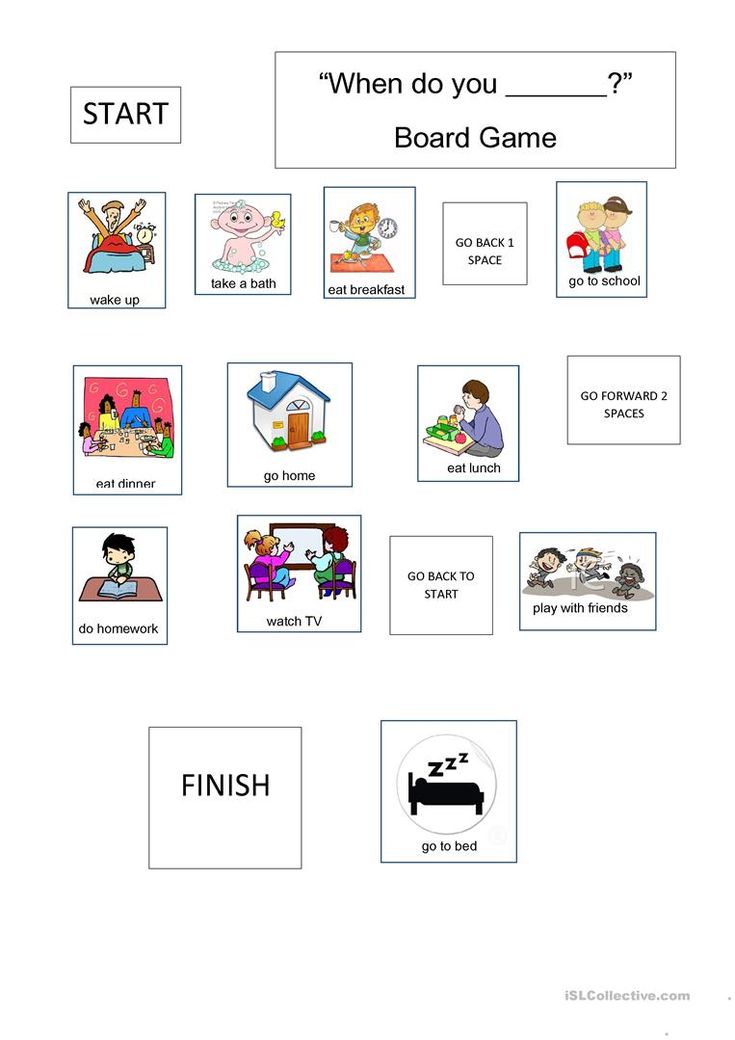

In this stage, a child learns to apply a logical sequence to her pretending. If she wants to give her doll a bath, for example, she will take off her clothes before doing so.

If she wants to give her doll a bath, for example, she will take off her clothes before doing so.

The child has learned through observing others and how people behave in various contexts and is strengthening her memory skills, so that this knowledge can be used later, in a play context.

5. Planned Pretend

In this final stage, known as planned pretend, a child will collect props and items that she needs for her pretend play.

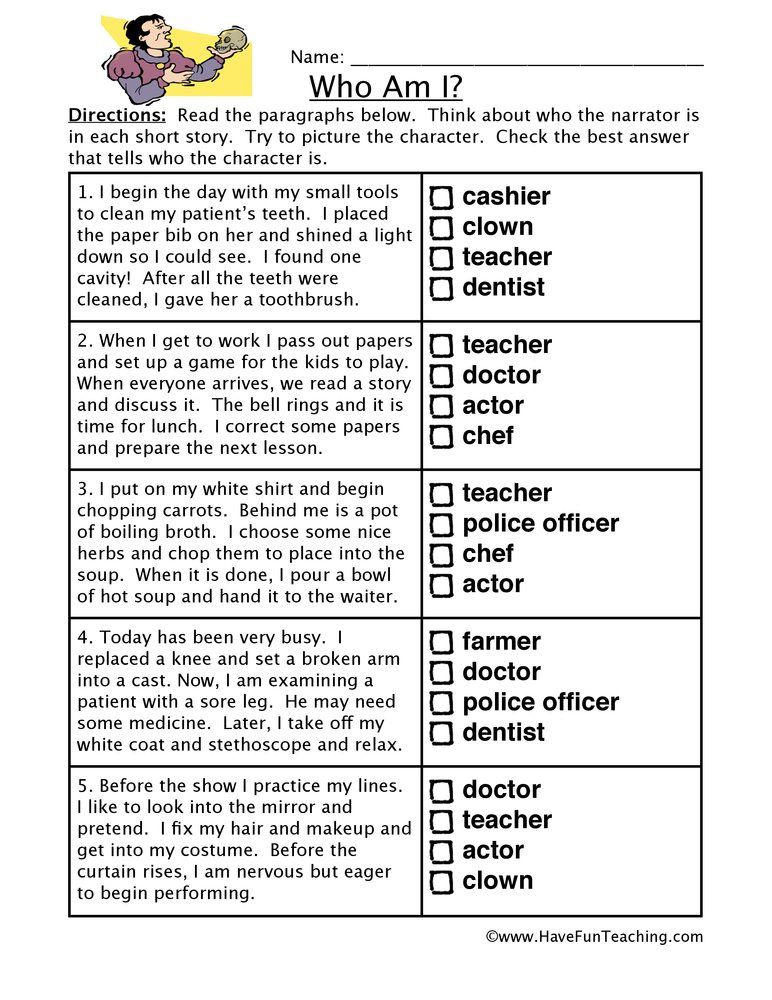

She will have a specific idea in mind for what she wants to act out and will plan accordingly. She may pretend to be a teacher giving a lesson, or a mother taking her child to the shops.

Preschoolers are usually in this stage of pretend play and they use high-level social skills while engaging.

They need to communicate well, play a specific role, allow others to play their roles, share and take turns, and follow the agreed rules, as they play with a common goal.

Sometimes this requires compromising, negotiating and persuading.

Read more about the types of play in early childhood.

Source:

Natanson, J. 1998. Learning Through Play: A parent’s guide to the first five years. Tafelberg Publishers Limited: Cape Town.

Get FREE access to Printable Puzzles, Stories, Activity Packs and more!

Join Empowered Parents + and you’ll receive a downloadable set of printable puzzles, games and short stories, as well as the Learning Through Play Activity Pack which includes an entire year of activities for 3 to 6-year-olds.

Access is free forever.

Signing up for a free Grow account is fast and easy and will allow you to bookmark articles to read later, on this website as well as many websites worldwide that use Grow.

- Share

Pretend

This article is about child's play. For other uses, see Make Believe (disambiguation).

For other uses, see Make Believe (disambiguation).

Pretend , also known as Pretend Game , is a loosely structured form of play that typically involves role playing, object swapping, and non-literal behavior. [1] What distinguishes play from other daily activities is its fun and creative aspect, rather than an act of survival or necessity. [2] Children pretend for a variety of reasons. This gives the child a safe environment for expressing fears and desires. [3] When children engage in role play, they integrate and reinforce previously acquired knowledge. [1] Children who have better pretending and fantasy abilities also show better social competence, cognitive abilities and the ability to accept the point of view of others. [2] In order for an action to be called a role play, one must intentionally deviate from reality. One must be aware of the contrast between the real situation and the imaginary situation. [2] If the child believes that the imaginary situation is real, then he misinterprets the situation, and does not pretend. Pretending may or may not involve action, depending on whether the child chooses to project their imagination onto reality or not. [4]

[2] If the child believes that the imaginary situation is real, then he misinterprets the situation, and does not pretend. Pretending may or may not involve action, depending on whether the child chooses to project their imagination onto reality or not. [4]

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Critical period

- 3 Components

- 3.1 Role play

- Non-literal activities0029 3.3 toys and requisite

- 3.3.1 Replacement

- 3.3.2 Doll play

- 4 influencing factors

- 4.1 Adult intervention

- 4.1.1 Gender Roles

- 4.1.2 Family structure

- 4.2 Scripts

- 4.1 Adult intervention

- 5 Social and cognitive development

- 5.1 Theory of mind

- 5.2 Counterfactual reasoning

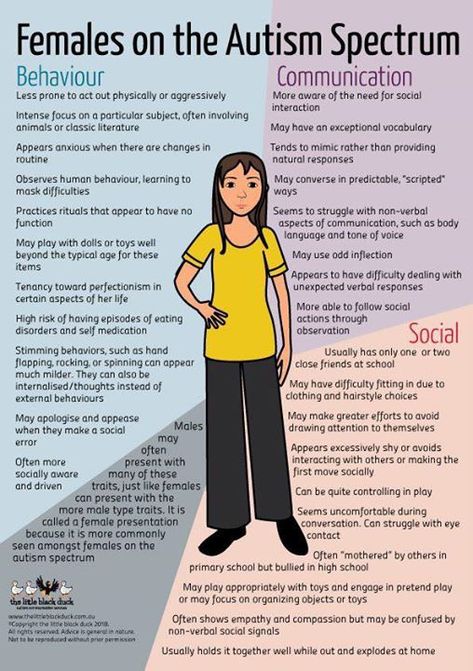

- 5.3 Autism spectrum disorder

- 5.4 Executive function0030

- 6 Education and acquisition of knowledge

- 6.1 Emotions

- 6.

2 Preliminary knowledge

2 Preliminary knowledge - 6.3 Authority and trust

- 7 See also

- 8 Recommendations

History

Personal Party Part , although it has probably been around since the beginning of mankind, as children tend to do it naturally on their own without being forced and without having to use a term to describe what they are doing. The initial stage fell on 1920s and 1930s when game studies gained popularity. At the time, there was virtually no empirical data on role-playing. The resurgence of interest that began in the late 1940s marked the second phase. The new mission was to find out how role play is related to the developing personality of the child. A common hypothesis during this period was that imagined behaviors projected the child's inner feelings and reflected their experiences in everyday life. The most recent stage, which continues to this day, began at 1970s. Research at this stage is greatly influenced by Jean Piaget's research and theories, either in terms of finding evidence to support it, or in terms of falsification.

Despite the cultural jargon associated with this issue, the story of the imagination game may indeed have originated at the dawn of consciousness itself. [1]

Despite the cultural jargon associated with this issue, the story of the imagination game may indeed have originated at the dawn of consciousness itself. [1] Critical Period

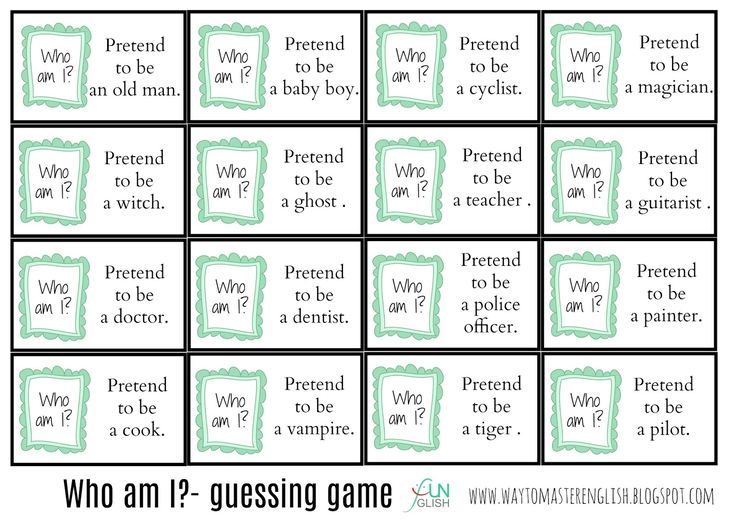

Pretense is thought to be innate because it is ubiquitous and begins immediately between 18 and 24 months of age (Lillard, Pinkham & Smith, 2011). The prevalence and frequency of pretending increases between the ages of one and a half and two and a half years. [1] The first stage of pretending usually begins with the substitution of the object. By the age of 3, a child can easily distinguish real life events from pretense. [4] Children aged 3 to 6 who are accustomed to role play show an increase in interactive role play. [1] This means that they participate in a relationship with each other, giving the doll a more active role (eg driving a car) instead of a passive recipient role (eg feeding). [1] At the age of three children's pretense remains close to their real life experience.

A three-year-old girl can imagine that she and her mother go grocery shopping. In this case, both her role in the relationship and the activity in which she takes part are literal. [1] Role-playing skills then improve between the ages of 4 and 5. [1] In the fifth year of schooling, the child demonstrates the ability to incorporate forms of relationships into play. [1] They are no longer limited to the role of a child, instead they can be parents or spouses or expand further into taking on the role of members of society such as police officers, doctors, etc. [1]

A three-year-old girl can imagine that she and her mother go grocery shopping. In this case, both her role in the relationship and the activity in which she takes part are literal. [1] Role-playing skills then improve between the ages of 4 and 5. [1] In the fifth year of schooling, the child demonstrates the ability to incorporate forms of relationships into play. [1] They are no longer limited to the role of a child, instead they can be parents or spouses or expand further into taking on the role of members of society such as police officers, doctors, etc. [1] Components

Role play

A girl pretends to walk with a doll.

When children engage in social role-playing or role-playing, they are impersonating the personality or certain traits of another person. [1] This includes the presentation of both external and internal qualities. [2] When a child plays with one or more people, he participates in an activity called sociodramatic play.

Sociodramatic play appears at about three years of age, and sometimes even earlier, in children who have older siblings. Early on, it follows a very strict script, is closely tied to existing roles, and features more parallel play than interactive play. By the age of 5, children begin to move away from strict roles and scripts. They begin to put more imagination into their roles and build on the creativity of their partners. [2]

Sociodramatic play appears at about three years of age, and sometimes even earlier, in children who have older siblings. Early on, it follows a very strict script, is closely tied to existing roles, and features more parallel play than interactive play. By the age of 5, children begin to move away from strict roles and scripts. They begin to put more imagination into their roles and build on the creativity of their partners. [2] Role play comes in three forms. Relationship role play, which usually occurs first, is based on relationships that the child observes or experiences. Such relationships include mother and child, father and child, husband and wife, etc. Functional role play emphasizes the work and activities that a character usually performs. Role-playing characters display stereotypical character traits, usually determined by their representation by society. [2]

Pretend play keeps children from low socioeconomic backgrounds from missing important developmental milestones, since all a child needs to pretend is their own imagination.

Skills that would otherwise need to be developed with educational toys can be developed through role play as it is not limited to a child's financial situation.

Skills that would otherwise need to be developed with educational toys can be developed through role play as it is not limited to a child's financial situation. Complex forms of role play involve the child's ability to imagine another person's mental representation. This skill appears when the child is about 5 years old. This strengthens the child's social abilities, allowing him/her to take the other person's point of view and therefore understand and cooperate with others. [2]

Non-literal actions

Five repetitive role-playing behaviors that indicate its non-literal aspect will be explained. The first behavior is the tendency to perform a task without the right tool, such as pretending to make a call without using a real phone. The second behavior is substitution, where the child may use the block rather than the phone to make a phone call. The third behavior, described in the section above, is when the child assumes the role of another person and does their normal activities, such as pretending to be a fireman and putting out a fire.

The fourth behavior is when a certain action produces an unrealistic result, such as a child pretending to clean a room simply by snapping a finger. The fifth behavior will be discussed in detail in the next section, and it involves giving an inanimate object, such as a doll, animate qualities such as talking and drinking tea. [1]

The fourth behavior is when a certain action produces an unrealistic result, such as a child pretending to clean a room simply by snapping a finger. The fifth behavior will be discussed in detail in the next section, and it involves giving an inanimate object, such as a doll, animate qualities such as talking and drinking tea. [1] It is important for the child to always understand that the pretense is isolated from the real world. This means that the child must understand the non-literal aspect of the game simulation and understand that changes made during the game simulation are temporary. Children should be aware that at the end of a play session, non-literal aspects of imaginary play, such as role-taking and substituted objects, also cease to exist. [4] One of the forms of pretend play that aroused interest to whom? creation of imaginary satellites. Imaginary companions may be entirely in the child's imagination, or based on a doll or soft toy depicting animate qualities.

About one to two thirds of children under the age of 7 have an imaginary life partner, which later decreases with age. [4] The meaning of this form of role play has not yet been determined, but there have been some speculations. [ by whom? ] that it supports young children's social skills.

About one to two thirds of children under the age of 7 have an imaginary life partner, which later decreases with age. [4] The meaning of this form of role play has not yet been determined, but there have been some speculations. [ by whom? ] that it supports young children's social skills. Toys and props

In the Welsch study, children received props showed a sophisticated level of play. [5] In the role play, any object in the child's environment can be used as a support.

Replacement for

Any object can be integrated into a role-playing game as a representation of another object. Such a representation is called a substitution. The ability to replace one object with another appears when the child is about 2 years old. [2] In early cases of substitution, children can only replace objects that have a similar structure or a similar function. [2] For example, a child might imagine that a pen is a toothbrush and a TV remote is a telephone.

The handle is roughly the same shape as a toothbrush, and the remote has buttons that work just like a phone. Around the age of 3, the child begins to master the substitute and no longer needs a physical or functional resemblance between the real object and the substitute. [2] The child also becomes capable of substitution without the use of a specific object, so it depends entirely on the imagination. [4] (for example, put your hand to your ear and start a conversation, pointing to a phone call). It also increases the ability to hold more than one replacement at a time, which means the child can pretend to be on the phone, walking the dog, and drinking juice at the same time. [2]

The handle is roughly the same shape as a toothbrush, and the remote has buttons that work just like a phone. Around the age of 3, the child begins to master the substitute and no longer needs a physical or functional resemblance between the real object and the substitute. [2] The child also becomes capable of substitution without the use of a specific object, so it depends entirely on the imagination. [4] (for example, put your hand to your ear and start a conversation, pointing to a phone call). It also increases the ability to hold more than one replacement at a time, which means the child can pretend to be on the phone, walking the dog, and drinking juice at the same time. [2] There are two types of replacements. Symbolic substitution is when one object is used to represent another, such as when a coach uses clubs to represent players in a game plan. A hypothetical substitution is when one object is used "as if" it is actually a different object, as in the previous example where the pen functions as a toothbrush.

[2]

[2] Doll play

A boy pretends to feed his doll.

Pretending with dolls begins when the child expands the pretense on the doll. The child may start by pretending to eat himself and then reach out and pretend to feed the doll. This develops further when the child begins to give the doll an active role rather than a passive one. [1] For example, the doll does not just eat when the child feeds it, instead the child pretends that the doll reaches for the spoon and eats itself. After the doll is given an active role, the child begins to endow it with sensory and emotional attributes, such as sadness, happiness, or pain. [2] The highest form of puppet play occurs when a child is about three and a half years old. At this stage, the child is able to give the doll cognitive abilities. [2]

The distinguishing feature between puppet play and social play involving more than one child is the degree of control the child has.

By participating in a puppet game, the child is in complete control of the situation. [2]

By participating in a puppet game, the child is in complete control of the situation. [2] Influencing factors

Pretend play is universal as it occurs in many or all cultures. [6] However, in some cultures this is frowned upon and is considered a form of communication with spirits or devils. [6] These different perspectives tend to influence the amount of time devoted to role play and the topics children interact with. [6] However, although role play is discouraged by many cultures, its inevitable emergence indicates that it develops from internal cognition rather than external environment or observed learning.

Adult intervention

Gender roles

Sex play is usually established between 4 and 9 years of age. [1] At this age, girls take on domestic and realistic roles, while boys are more inclined towards fantasy and physically active roles. [1] The extent to which these roles are expressed has been related to parental attitudes.

Children of parents who encourage sexual roles and disapprove of cross-gender references show more examples of sex-oriented play. [1] While parental attitudes are most important, other adult role models, such as teachers and family members, can also reinforce gender play.

Children of parents who encourage sexual roles and disapprove of cross-gender references show more examples of sex-oriented play. [1] While parental attitudes are most important, other adult role models, such as teachers and family members, can also reinforce gender play. Family structure

Imagination levels are closely related to the child's family environment. Problems such as family conflict and physical forms of discipline create anxiety and tension in a child's life. This was associated with decreased play behavior and low levels of imagination. [1]

On the other hand, strong and reassuring relationships between children and their parents, more specifically fathers, are associated with higher play rates and imagination. [1] When parents introduce role-playing to their children at an early age, they begin to imitate their actions and create their own role-play scenarios. [4] Children also become more able to recognize social cues such as eye contact and referencing.

[4]

[4] Scripts

Participants in pretend play can draw inspiration from many sources. Welsh describes a book-related role play in which children draw texts to initiate games. [5] Children are most interested in texts, for example, with a significant level of tension. [5] Children who use more fantasy themes of pretending tend to understand the concept of pretending at an earlier stage. [4] While storytelling and acting inspire creativity in role-playing games, long-term TV work is associated with lower levels of imagination. [1]

Social and cognitive development

The association between pretend play and subsequent cognitive and social skills suggests that simulated play may have a causal effect. Current research is attempting to explore how pretend play can be used to develop and improve performance in mental task theory, reasoning skills, and how it can be used as an intervention method, especially for children with autism.

Most research focuses on the preschool period as this age group shows the most emergence and development in role play and following social and cognitive skills. Early childhood research is also looking to use role play as a teaching method.

Most research focuses on the preschool period as this age group shows the most emergence and development in role play and following social and cognitive skills. Early childhood research is also looking to use role play as a teaching method. Theory of Mind

Pretend play includes several abilities that match Theory of Mind. The first two abilities relate to the representation of objects. The child has the ability to mentally represent one object as another. The child also has the ability to understand the paradox in which an object can represent another but is essentially the same object. [2] This means that the child must have two conflicting mental representations of the same object. In 3-year-olds, this cognitive ability appears in role play but not in other activities. [2] For example, a child may pretend that the pen is a toothbrush, but when shown an apple-shaped bar of soap, the child cannot understand the real and apparent characteristics of the object.

This inability is called the mutual exclusivity bias. [2] However, the development of pretend play was found to correlate with the performances in the previous example along with the performance of the false belief task, which also tests the child's understanding of mental representations. [2] Children begin the false belief task at about 4 years of age. [2]

This inability is called the mutual exclusivity bias. [2] However, the development of pretend play was found to correlate with the performances in the previous example along with the performance of the false belief task, which also tests the child's understanding of mental representations. [2] Children begin the false belief task at about 4 years of age. [2] Children pretend to play lightsabers.

The third ability is related to social representation, in which the child can represent the mental representations of another person, such as desires, thoughts and feelings. This ability appears when the child is about 5 years old. [2] This allows the child to look at others and strengthens their understanding of the thoughts and beliefs of others. [2] By this age, children are aware of the subjectivity of pretending. The ability to look to the future also plays a central role in a person's ability to collaborate and work with others.

This is a tricky presentation skill because it requires the child to have a presentation of the presentation. The child must also remember that the picture he is holding is not his own. When a child participates in a role play, they are participating in a simulation in which they place themselves in the character's mental state. [4]

This is a tricky presentation skill because it requires the child to have a presentation of the presentation. The child must also remember that the picture he is holding is not his own. When a child participates in a role play, they are participating in a simulation in which they place themselves in the character's mental state. [4] Another ability, shared attention, is related to social links. Both theory of mind and pretense require a certain degree of interaction and communication with others. Joint attention includes the ability to follow another person's landmark, gaze, or point of view. When children engage in pretend play with other people, they are required to share the same pretend assumptions about the object and situation as the other person. [4] For example, when simulating a ride, both children need to know that the chairs they sit on are car seats. Children show more examples of joint attention in role-play than in other non-symbolic games.

[4]

[4] Counterfactual reasoning

Counterfactual thinking is the ability to conceptualize alternative outcomes of the same situation. Research confirms that children between the ages of 4 and 6 are better able to conceptualize alternative outcomes when the situation is unrealistic or presented in an imaginary context. [2] Children also learn better when the situation presented is open. When a situation has already ended, it is difficult for a child to think of an alternative. [6] A similar factor between counterfactual reasoning and pretend play is that they both deal with situations that deviate from actual events. [6]

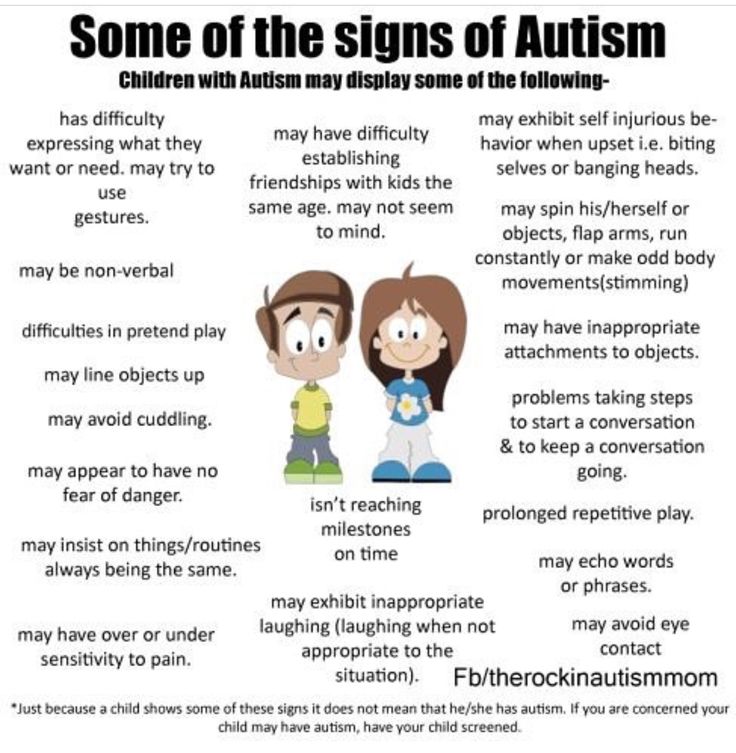

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Individuals with autism show large delays in role play. This delay correlates with their inability to complete false belief tasks at 4 years of age. [4] Another delay found in children with autism is language delay. This delay in speech development is associated with role play, so children with autism who participate in role play have more developed language skills.

[4]

[4] Executive function

Executive function refers to a specific set of cognitive operations that include inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Inhibitory control has been particularly associated with pretend play, especially during play that involves changing objects such as pretending to stick like a sword. Typically, a child's ability to suppress the real identity of an object in order to relate to it with its imagined identity changes with age. [7] and which attributes the child should ignore, form and/or function. [8] In general, previous research has shown that pretend play can improve a child's executive function, but the question of whether it is pretend play or some other part of the activity, such as the practice of making up stories or building a fort, is a responsible one. open. [9]

Learning and acquiring knowledge

Pretend play is not only related to the development of general cognitive abilities.

[9] and reinforcing existing knowledge, [1] but a recent study examines how children acquire new knowledge during role play. [10] Although children do not invent new knowledge on their own by pretending with others, children make judgments about the generalizability of unknown information introduced by others in an imaginary context. These judgments influence the degree to which children believe that the information is applicable and reflects the real world. A number of factors are known to influence these judgments, including the fantasy themes used in the imaginary world, as well as the credibility of other players in the game.

[9] and reinforcing existing knowledge, [1] but a recent study examines how children acquire new knowledge during role play. [10] Although children do not invent new knowledge on their own by pretending with others, children make judgments about the generalizability of unknown information introduced by others in an imaginary context. These judgments influence the degree to which children believe that the information is applicable and reflects the real world. A number of factors are known to influence these judgments, including the fantasy themes used in the imaginary world, as well as the credibility of other players in the game. Emotions

By the age of three, children are usually able to distinguish fantasy and pretense from reality, but there are a number of reasons why children can confuse them. [11] In some cases, children seem to be unable to control their emotions, especially fear, and this leads to what may appear to be a confusion between reality and pretense, such as monsters hiding in their toy basket.

[12] Negative emotions such as fear and anger also seem to negatively influence children's tendency to believe that an event is possibly real or imagined and more or less likely to actually happen. [13]

[12] Negative emotions such as fear and anger also seem to negatively influence children's tendency to believe that an event is possibly real or imagined and more or less likely to actually happen. [13] Preliminary knowledge

As early as 15 months, babies demonstrate both an understanding of pretense and the expectation of reality that is reflected in pretense. [14] Sometimes the role-play may involve animals, objects or places that the child knows little or nothing about, and any information about these objects presented during the role-play is easily associated with this object. [8] However, when a child has some knowledge of the subject of pretense, such as the behavior of lions, and new information is introduced that contradicts his knowledge, such as that lions only eat animal crackers, they are less likely to learn it. information is generally true for lions outside of the context of pretend play and may even resist this premise in pretend play.

[10] In fact, the degree to which the imaginary context is more or less related to reality, such as how realistic the task is or whether the characters are people the child might encounter, affects how likely the child is to learn generalizations from the imaginary context. games. [15]

[10] In fact, the degree to which the imaginary context is more or less related to reality, such as how realistic the task is or whether the characters are people the child might encounter, affects how likely the child is to learn generalizations from the imaginary context. games. [15] Authority and trust

Children do not treat all new information equally, and in fact a number of situational and source-dependent factors affect how children believe information is true or applicable to reality, as in the case of a role-playing game. When playing with an adult, children generally tend to trust the veracity of information. [16] although the degree to which this conflicts with what they already know or believe will still affect how much they generalize to reality. [10] However, over multiple sessions of play with a person, how reliable or accurate the information from that person has been in the past will proportionally affect how likely the child is to believe the new information.

[17] Also, other adult or peer attributes may influence the child's judgment. Children have been shown to be sensitive to socioeconomic cues and differences. [18] Children also look at the informant's position in relation to the perceived group, whether it be the group involved in the game or the larger social group with which the child identifies, and show a bias towards information coming from a less conflicting position with majority. [19] In general, children, although they tend to trust adults, still apply rational judgments to new information presented during role-play, which affects their tendency to believe how much this information generalizes to reality. 9 Harris, Paul L.; Corriveau, Kathleen H. (April 12, 2011). "Selective Trust of Young Children in Whistleblowers". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences . 366 (1567): 1179–1187. Doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0321. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 3049091.

[17] Also, other adult or peer attributes may influence the child's judgment. Children have been shown to be sensitive to socioeconomic cues and differences. [18] Children also look at the informant's position in relation to the perceived group, whether it be the group involved in the game or the larger social group with which the child identifies, and show a bias towards information coming from a less conflicting position with majority. [19] In general, children, although they tend to trust adults, still apply rational judgments to new information presented during role-play, which affects their tendency to believe how much this information generalizes to reality. 9 Harris, Paul L.; Corriveau, Kathleen H. (April 12, 2011). "Selective Trust of Young Children in Whistleblowers". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences . 366 (1567): 1179–1187. Doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0321. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 3049091. PMID 21357240.

PMID 21357240.

Playing man. Part 2: The disappearance of game elements from human culture: invirostov — LiveJournal

45) "Homo ludens" ("Man playing")

In the first part (http://invirostov.livejournal.com/65793.html) I questioned Huizinga's opinion that the game is primary and culture, and culture unfolds in the game and as a game.

My opinion is different: the game is an important element of culture, but just an element. Culture can be viewed through the prism of the game (and it's a very interesting approach!), but you can't limit yourself to just this angle. Culture unfolds not in the game, but in the most diverse aspects of human existence, which are by no means reducible to the game.

So, the thesis that "culture arises in the form of a game" seemed to me not convincing enough, and its justifications were internally contradictory. Sometimes the impression was created that Huizinga plays with the reader according to her own rules, deliberately confusing causal relationships - and it is this game that she ironically uses as her main evidence. And if this is really so, then he won!))

And if this is really so, then he won!))

Now let's move on to another very important point in the book: the question of the disappearance of elements of the game from human culture.

Huizinga argues that in the 19th century (and, to some extent, even in the 18th), as bourgeois ideals take over the spirit of society, economic factors come to the fore both in society and in the spiritual state of a person. These trends are reinforced by the industrial revolution. Labor and production become the ideal. Less and less room is left for the game - society has become too serious about its needs and interests. Huizinga goes on to give examples from specific areas of human culture. These examples did not seem convincing enough to me. So, he says that the currents of philosophical thought of the XIX century. directed against the game factor - neither liberalism nor socialism gave him food. Here I immediately have a question: do these areas of the game element shy away? For example, utopian socialism (Owen's communes, Fourier's social theories, Chernyshevsky's dreams of "new people",) - doesn't it have elements of the game? Further, Huizinga notes that similar processes are observed in art and literature: realism, naturalism, impressionism are alien to the concept of play. And again, I disagree. Realism, naturalism - let's say (although even here with a stretch - imitation of reality is already a game). But why does Impressionism deprive Huizinga of the playing factor? In my opinion, on the contrary, in all decadent styles of play there is a lot, it is just a game with vaguely defined rules: after all, the old rules are no longer suitable, and new ones have not yet been developed.

And again, I disagree. Realism, naturalism - let's say (although even here with a stretch - imitation of reality is already a game). But why does Impressionism deprive Huizinga of the playing factor? In my opinion, on the contrary, in all decadent styles of play there is a lot, it is just a game with vaguely defined rules: after all, the old rules are no longer suitable, and new ones have not yet been developed.

But still, in general, I agree with Huizinga: the Modern world is very pragmatic, and pragmatics kills the game.

And the thoughts expressed in the book about the fate of the game in the 20th century seemed especially interesting to me. Huizinga asks the question: did the lack of play fill up in the 20th century? And it shows that the situation has worsened: the game element in culture is becoming less and less (for example, sports have separated from the gaming sphere, becoming a serious commercial business). Instead, a "pretend" game appears, i.e. game forms are used to hide the intentions of certain social or political groups.

"Make play" ... but, in essence, this is nothing but a postmodern "simulacrum"! Huizinga felt how the world of Modern rots and mold begins to grow on his body, which will later be called "postmodern". And he perfectly described this process through the same prism of the game.

Further, Huizinga says that a person began to behave like a teenager (a constant need for entertainment, a thirst for sensations, a craving for mass spectacles, etc.) and emphasizes that puerilism (naivety and childishness) is not at all what what a game. Huizinga sees the reasons for this in the introduction of semi-literate masses to mass culture, in the fall of moral standards, in the exaggeration of the role of society. But I think the reasons go deeper. Let me express my thoughts on this matter. Man understands that he is mortal and he is afraid of it. Religion helps to overcome the fear of death. But the world of the XIX-XX centuries is secularized. A secular person is helped to overcome the fear of death by some higher ideals (“yes, I am mortal, but I have something to live for!”). But the ideals are being eroded... and even humanism is no longer the spiritual bond of society - after all, we see too much violence, wars, and lies around us. The person stops believing in anything. And so childishness becomes a subconscious way to “hide” from death (“if I remain a child, I will never grow old and die”).

But the ideals are being eroded... and even humanism is no longer the spiritual bond of society - after all, we see too much violence, wars, and lies around us. The person stops believing in anything. And so childishness becomes a subconscious way to “hide” from death (“if I remain a child, I will never grow old and die”).

Huizinga argues that culture should not lose play content, since the game involves self-restraint and self-restraint, the ability not to put one's personal aspirations at the forefront. I think this is partly true, but only if you look at the culture again only from the point of view of the game. But if you look more broadly, I would say this: culture should not lose its humanistic essence (which includes the game as an integral part).

So, the thesis that the game element of culture has lost its significance since the 18th century seemed to me much stronger and more convincing than the thesis that "culture arises in the form of a game" . Of particular interest to me were the thoughts of "pretending" play; that it is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish between play and non-play. It seems to me that if Huizinga lived in our time, he would write that the Game has completely disappeared from our world. After all, postmodern philosophy teaches that everything is a game. But if everything is a game, then the game seems to be no more, there remains a certain pseudo-game (or "pretend game", as Huizinga called it). And if everything is a feigned game, then there is nothing real, authentic. But if there is no authenticity, then how can culture (and, accordingly, the game, as its component) exist? And, although I do not agree that culture arises from the game, nevertheless, I think that the total "fake game" can destroy culture.

It seems to me that if Huizinga lived in our time, he would write that the Game has completely disappeared from our world. After all, postmodern philosophy teaches that everything is a game. But if everything is a game, then the game seems to be no more, there remains a certain pseudo-game (or "pretend game", as Huizinga called it). And if everything is a feigned game, then there is nothing real, authentic. But if there is no authenticity, then how can culture (and, accordingly, the game, as its component) exist? And, although I do not agree that culture arises from the game, nevertheless, I think that the total "fake game" can destroy culture.

At the end of the book, Huizinga says that a person himself, "based on his moral sense, must decide whether the action to which his will leads him is prescribed as something serious or allowed as a game." Well... that's not bad. But what can a person rely on in our modern world, where all sorts of supports are knocked out from under his feet? Huizinga does not answer this question.