A number play

Inside A NUMBER | Writers Theatre

The word CLONE will not be used in A Number.However, the word was everywhere in the late 90s and early 00s as the world was gripped by widespread concern that human cloning was just around the corner.

Cloning is the act of creating a new organism with the exact genetic makeup of an existing life.

Although scientists had succeeded at cloning tadpole embryo cells as early as 1952, for decades after no one had been able to successfully clone any organisms using adult cells. By the 1980s, most labs were abandoning the research altogether.

That all changed on July 5, 1996. A lamb that had been cloned from cells from an adult sheep was born on a farm in Scotland. Her name was Dolly. And the world went crazy.

“The genie is out of the bottle. This technology is not, in principle, policeable.”

Ronald Munson, Ethicist

“It’s unbelievable.

It basically means that there are no limits. It means that all of science fiction is true. They said it could never be done and now here it is, done before the year 2000.”

Lee Silver, Biologist

“[The cloning of Dolly] raises serious ethical questions, particularly with respect to the possible use of this technology to clone human embryos.”

President Bill Clinton

A Number tackles head on the tremendous possibilities that Dolly unleashed on the world and which become closer to a reality with every new scientific breakthrough. Each of these five scenes reveals layers of a complex mystery about individuality and whether it’s really possible to atone for the sins of the past.

As you piece together the thrilling puzzle, you might also ponder:

- How much of a role does your genetic makeup play in defining who you are?

- What is a bigger influence: nature or nurture?

- Is there any circumstance in which human cloning might be acceptable?

Characters and Cast

Salter, a man in his early 60s

Portrayed by William Brown

Bernard (B1), his son, 40

Portrayed by Nate Burger

Bernard (B2), his son, 35

Portrayed by Nate Burger

Michael Black, his son, 35

Portrayed by Nate Burger

Setting

The scene is the same throughout, it’s where Salter lives.

Synopsis

SCENE ONE

Salter and his son Bernard (B2) are in the middle of a conversation at Salter’s home. Bernard has recently been informed that there are several clones (“copies”) of him. He doesn’t know how many exactly, but there are “a number of them, of us.” His father professes to know nothing about this, but reassures his son that Bernard had a normal birth and that Salter is his biological father. These others must be copies of Bernard made illegally using his DNA. Salter insists they should sue the doctors and hospital because “they damaged [Bernard’s] uniqueness, weakened [his] identity.” He calls them “things”, to which Bernard corrects him that “they are all still people.” Bernard again presses his dad for information about his birth, revealing that he was told that he is in fact one of the copies, not the original. Salter confesses that his wife did not die in childbirth as he had always told Bernard; she and his four-year-old son were killed in a car accident. Salter had his dead son cloned, creating B2, so that he could have the same son back again (“you’re what I wanted, you’re the one”), rather than have a new biological child. He admits he even gave Bernard the same name as his first son.

Salter had his dead son cloned, creating B2, so that he could have the same son back again (“you’re what I wanted, you’re the one”), rather than have a new biological child. He admits he even gave Bernard the same name as his first son.

Scene Two

Salter is at home with Bernard (B1), his first son whom he had told the other Bernard (B2) had died in a car accident. Salter is blaming the doctors for making multiple unauthorized copies of B1 and saying that they should sue. Bernard, however, wants Salter to confront the fact that he sent his biological 4-year-old son away and went to all the trouble and expense of replacing him with a genetically identical clone. Salter attempts to explain his actions, calling it “a tribute, I could have had a different one, a new child altogether [...] but I wanted you again because I thought you were the best.” Bernard asks his father about the times when he would call out in the night for him, asking why he never came. Salter insists he never heard Bernard, before adding “sometimes you put [children] to bed and they want another story and you say goodnight now and go away and they call out once or twice and you say no go to sleep now and they might call out again and they go to sleep. ” Bernard implies he might harm B2, before demanding Salter look him in the eye and acknowledge his existence.

” Bernard implies he might harm B2, before demanding Salter look him in the eye and acknowledge his existence.

Scene Three

Salter and B2, the Bernard from the first scene, are discussing B1, the original son, whom B2 has just met. B2 is upset because of two things: how frightening the encounter was with his aggressive “brother”, and the fact that his father has once again lied to him, as clearly B1 did not die in a car accident at four years old with his mother. Bernard is openly contemplating leaving the country to get away from all this, but demands his father tell him the truth about his mother. Salter reveals that she killed herself by throwing herself under a train when B1 was two years old. He then attempted to raise his son alone for two more years while struggling with alcohol addiction. It wasn’t going well and so Salter gave the boy up, got his act together, and then had B2 made. Bernard struggles to reconcile his feelings about the loving father he had with the neglectful father Salter was to B1, saying “I can’t give you credit [for being good] if I don’t give you blame for the other, it’s what you did it’s what happened. ” Ultimately, he concludes that he doesn’t blame his father but tells Salter that both sons hate him for what he did to them. Salter tells B2 he loves him, but his son continues to think about leaving the country now that he’s afraid B1 might kill him.

” Ultimately, he concludes that he doesn’t blame his father but tells Salter that both sons hate him for what he did to them. Salter tells B2 he loves him, but his son continues to think about leaving the country now that he’s afraid B1 might kill him.

Scene Four

B1, the original son, returns again to tell his father that he has murdered B2. Despite Salter’s attempts to draw more information about the murder out of him, B1 won’t give him what he wants. Salter begins to wonder if B1 plans to kill all the clones, or whether he’s there to kill his father. Salter reminds the boy that he didn’t kill him when he was a child, despite considering it, saying “I remembered what you’d been like at the beginning and I spared you, I didn’t want a different one, I wanted that again because you were perfect just like that and I loved you.” B1 still refuses to talk, and so Salter confronts his son about his memories of crying out for his father in the night, revealing that he did sometimes hear the cries but was unwilling or unable to come to him. Salter further elaborates on how badly his son’s condition was deteriorating[CP1] before he finally gave him up, although he admits “the whole thing is very vague to me. It’s two years I remember almost nothing about but you must remember things and when you’re that age two years is much longer, it wasn’t very long to me, it was one long night out.” Finally, Bernard begins to tell his father more about murdering B2.

Salter further elaborates on how badly his son’s condition was deteriorating[CP1] before he finally gave him up, although he admits “the whole thing is very vague to me. It’s two years I remember almost nothing about but you must remember things and when you’re that age two years is much longer, it wasn’t very long to me, it was one long night out.” Finally, Bernard begins to tell his father more about murdering B2.

Scene Five

Salter has decided to meet all the other clones of his son and is hosting Michael Black at his home. Michael is genetically identical to B1 and B2 but has never met his “father” before. Salter asks Michael to tell him things about himself so he can hear how similar or dissimilar Michael is to his sons. The stories and anecdotes and facts Michael offers don’t give Salter what he is looking for, however. When asked how he felt learning he was a clone, Michael admits he was fascinated, “I think it’s funny, I think it’s delightful.” At this point, Salter reveals he is now grieving the loss of both his sons, with B1 having killed himself. With both sons gone, he feels he “can’t put it right anymore.” Michael, meanwhile, is happy with how his life has turned out.

With both sons gone, he feels he “can’t put it right anymore.” Michael, meanwhile, is happy with how his life has turned out.

The questions below will help you explore some of the ideas in

A Number—but they may also spoil some of the surprises if you read them before watching! So proceed with caution.***

***

***

-

Why did Salter lie to his cloned son Bernard (B2) about the nature of his existence? Is there a time in his son’s life when you believe he should have told him the truth?

-

Why do you think Salter chose to clone his original son Bernard (B1)? Does he successfully justify his choice at any point in the play?

-

What was the original Bernard (B1) hoping to get from his father in his engagements with him?

-

Do you consider the second Bernard to be a copy of the first? Or are they more like identical siblings?

-

What was Salter hoping to hear from Michael Black in the final scene?

-

Why do you think Michael reacts so differently than B2 to learning he is a clone?

-

The play demands that one actor play three identical sons.

In what ways were these three unique personalities differentiated from one another by the actor?

In what ways were these three unique personalities differentiated from one another by the actor? -

What do you think compelled Caryl Churchill, a feminist, to write a play with no women? How does the absence of women influence the story?

-

How much of a role does your genetic makeup play in defining who you are?

-

If all of Salter’s sons (Bernard 1, Bernard 2, Michael Black) have identical DNA, why do they behave so differently?

-

Do you side strongly one way or the other in the “nature vs. nurture” debate? What do you think the play suggests?

-

Science Fiction, at its very best, makes us contemplate relatable truths through imaginative concepts. In what ways did this as-of-yet fictional scenario make you examine or even question your beliefs?

-

What are your personal feelings on cloning? Are there any circumstances in which you would consider the cloning of human cells permissible?

Join your fellow audience member for moderated post-show discussions on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday evenings, or debate with your friends using our curated list of questions.

All drinks at the WT Bar are half price during these post-show conversations!

A Number review – Caryl Churchill's clone fable counts cost of progress | Theatre

Caryl Churchill wrote A Number in 2002, when debates around human cloning were at fever pitch. The frontiers of that “scary” science brought with it a barrage of ethical dilemmas around genetic replication.

Almost two decades later, cloning is not the issue it was and this play, featuring a father and three cloned sons, does not have the present-day urgency of Far Away, a climate dystopia that Churchill wrote two years before this one, whose latest revival opened last week. But although A Number appears more dated, its underlying questions remain issues of our day, and when applied to debates around technology and artificial intelligence, it begins to feel as contemporary as Black Mirror.

Bernard 1 and Bernard 2 (both played by Colin Morgan) are sons seeking answers from their father, Salter (Roger Allam). Beneath specific questions about their early lives, their dead mother and their cloning lie big existential interrogations: is the original Bernard 1 more “real” than the cloned Bernard 2? Do they need to be unique to be human? Does science degrade humanness through its exact replication? It is not the angry Bernard 1 nor the fearful Bernard 2 who are the most disturbing characters in this play but Michael, another cloned son (also played by Morgan), because he remains unruffled by the fact that there are numerous versions of him in the world.

Beneath specific questions about their early lives, their dead mother and their cloning lie big existential interrogations: is the original Bernard 1 more “real” than the cloned Bernard 2? Do they need to be unique to be human? Does science degrade humanness through its exact replication? It is not the angry Bernard 1 nor the fearful Bernard 2 who are the most disturbing characters in this play but Michael, another cloned son (also played by Morgan), because he remains unruffled by the fact that there are numerous versions of him in the world.

One of Churchill’s themes is the welfare of children, and this play also, ingeniously, functions as a family drama about sibling rivalries and parental abuse. The biblical Cain and Abel story hangs over the brothers’ rivalrous relationship, and Salter’s desire to have his first son cloned seems to be connected to the parental fantasy of getting it right the second, third or 20th time around.

Churchill’s linguistic tics – of interruptions and half-finished sentences – create a hyperreal effect and enable Salter’s obfuscation, or withholding, of the full facts around family life. Morgan is outstanding in his switches between the three brothers, bringing a different energy to each one, while Allam plays Salter as a stuttering, deflecting, morally evasive man. But together their performances don’t quite fizz into the full-on chemistry needed to crank up the tension between them.

Other elements help to raise the stakes in Polly Findlay’s production, especially Lizzie Clachan’s set and Peter Mumford’s lighting, which have a noirish quality despite the drab domestic realism – scenes take place inside Salter’s home. Clachan also created the set for Far Away and, like that design, this has startling scene changes as the lights drop to black and snap back on to a transformed stage. Some of the effects veer to hammy, especially the garishly melancholic piano interludes. As a whole, the play retains its power to provoke, but builds a suspense that is more cerebral than visceral.

At the Bridge theatre, London, until 14 March.

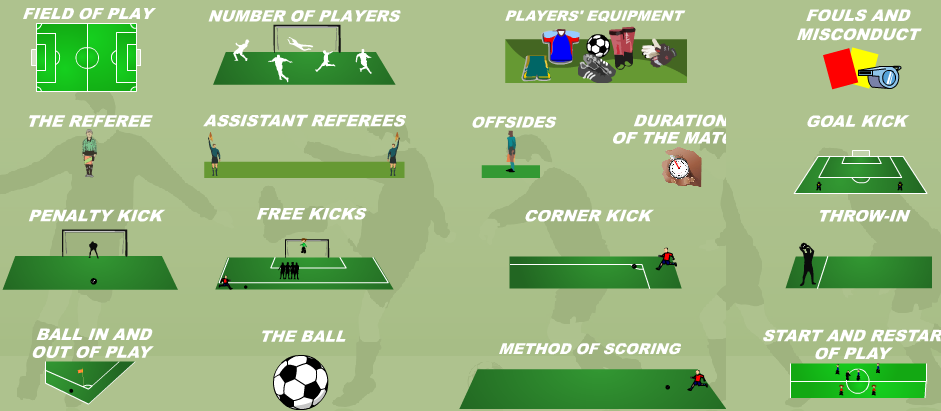

| Chris Anderson, David Sally Playing with numbers. Masterful Strategies and Tactics on the Soccer Field Dedicated to: To Our Home Teams: Kathleen, Nick & Eli Serena, Ben, Mike, Tom & Rachel The Numbers Game: Why Everything You Know About Soccer Is Wrong by Chris Anderson and David Sally © Chris Anderson and David Sally The Numbers Game first published in Great Britain in the English langauge by Penguin Books Ltd, London. Text copyright © 2014. The author has asserted his moral rights. All rights reserved © Translation. Kruse M.A. © Design. LLC Eksmo Publishing House, 2016 A few words about the “game with numbers” A fascinating and stylish study of how the understanding of football is rapidly changing. Jonathan Wilson, author of book Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Wonderful book. Alison Kerwin, sports editor, Mail on Sunday Debunks the myths and stereotypes that have defined football for the last century. Jack Bell, The New York Times Not only does it help fans understand the game better, but it encourages them to look for new ways to analyze and think about it. Zach Slayton, Forbes The best sports book of the summer. Simon Mayo, BBC Radio 2 About the Authors At the age of 17, Chris Anderson played for a fourth division club in West Germany and is today a professor at Ivy League affiliate Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Anderson, an award-winning sociologist and pioneer in football analytics, advises leading clubs on how best to play football. David Sully is a former baseball pitcher and professor at the Johnston School of Business. Taka at Dartmouth College in the USA, where he analyzes the strategies and tactics people use in play, competition, negotiation and decision making. Football for skeptics - number reformation In sports, what is true is more important than what you believe, because what is true will give you an edge. Bill James Football has long been dominated by five words: That's how it's always been done. A beautiful game steeped in tradition. A beautiful game clings to its dogmas and clichés, its convictions and beliefs. This beautiful game is run by people who do not want to see their power challenged by outsiders who know that it is their understanding of the game that is correct. They don't want to hear that they've been missing something for over a hundred years. That there is some knowledge that they do not possess. That things have never been done the way they are must be followed by . Beautiful play is stubborn in its delusions. A beautiful game is a game that needs to change. And the key to these changes are the numbers. It is the numbers that will challenge the accepted order of things and change the norms, revise customs and destroy traditional ideas. It is the numbers that allow us to see the game as never before. Every world class club knows this. All of them hire analysts, data collectors and interpreters who use all the information they can get bit by bit to plan training sessions, develop game systems, organize transfers. Millions of dollars and hundreds of awards are at stake. Each club is ready to do everything possible to get the slightest advantage. But here's what none of these clubs have bothered to do yet: take these numbers and understand their inner essence. And it's not just data collection. You need to know what to do with them. This is the cutting edge of football. It is often said that football cannot (or cannot) be analyzed using banal statistics. According to critics, this will deprive the beautiful game of all its beauty. This is not to say that all football traditions are wrong. The information that we can now collect and analyze confirms that some of the postulates that we have always considered true are in fact true. But beyond that, the numbers give us the opportunity to learn other truthful facts, explain what is impossible to understand intuitively, and make clear the fallacy of the statement that "this is how it has always been done." The biggest problem that comes with following respected traditions and longstanding dogmas is that they are rarely questioned. Knowledge remains static while the game itself and the world around it change. Asking questions This is a simple question that Americans have often asked in such a perplexed tone when discussing football: – Why are they doing this? Dave and I were watching the most interesting matches in the Premier League, and something caught his attention. Every time Stoke City won a throw-in from throw-to-goal, Delap would run to the touchline, wipe the ball off with his shirt (or, if it was on the home pitch, with a towel specially designed for that purpose) and sent him towards the gate again and again. As a former goalkeeper, the advantages of Delap's throw-ins were obvious to me. I explained to Dave: Stoke are a decent team, but they lack a bit of pace and even more lack of skill. But what they do have is their height. So why not try to create a chance out of nothing when the ball goes out of play? Why not cause a little turmoil in the ranks of your rivals? It seems to work. But that didn't satisfy Dave's curiosity. For him, this simply became an occasion to ask the following logical question: - So why isn't everyone doing this? The answer to this was also obvious: not every team has Rory Delap, a player who can throw the ball from out of bounds for such long distances, and at the same time on such a flat trajectory. Dave, himself a former baseball pitcher, went the other way: “But why not try to find such a player? Or not have one of your players raise the bar and throw the javelin and hammer?” Yes, it was not easy. Dave's questions, like those of an inquisitive kid, were starting to get annoying. But what made me even angrier was that I didn't have the right answer. “You can play the way Stoke does,” I retorted, “as long as you have Delap and a lot of tall centre-backs. But it's not that attractive. And you will only do this when you have nowhere to go. |

Number game. Virtuoso strategies and tactics on the football field”, Anderson K. - Trade House “Biblio-Globus”

909 RUB in stock

Store location:

At the 1st level

Hall: 08 Section: 06 Wardrobe: 50 Shelf: 01

Place an order in the online store

Publisher: Eksmo

Year of publication: 2020

ISBN: 978-5-699-84998-7

What is this book about? Do you think you know everything about football? This book will make you think about those canons that you used to consider inviolable. It will thoroughly and clearly debunk many myths and stereotypes about football. Unlike many other works, she does not impose her opinion. It only suggests thinking and looking at the situation from several angles. Will tell you about new and unusual tactics that the teams use, but which are not visible to ordinary viewers. They will show schemes that are not advertised, and techniques hidden from the eyes of the layman. The publication will plunge into a whirlpool of passions, stereotypes and destructive truth. Are you still sure that you know at least something about football? Who is this book for? This book is for those who think that they understand at least a little bit about football, know the basic tactics and strategies of the game. Book feature. At the moment, this publication has no competitors in the Russian book market. Many books about strategies and tactics that were published in Russia have already lost their relevance, and cannot convey relevant information to the reader.

It will thoroughly and clearly debunk many myths and stereotypes about football. Unlike many other works, she does not impose her opinion. It only suggests thinking and looking at the situation from several angles. Will tell you about new and unusual tactics that the teams use, but which are not visible to ordinary viewers. They will show schemes that are not advertised, and techniques hidden from the eyes of the layman. The publication will plunge into a whirlpool of passions, stereotypes and destructive truth. Are you still sure that you know at least something about football? Who is this book for? This book is for those who think that they understand at least a little bit about football, know the basic tactics and strategies of the game. Book feature. At the moment, this publication has no competitors in the Russian book market. Many books about strategies and tactics that were published in Russia have already lost their relevance, and cannot convey relevant information to the reader.

Additional information:

| Code: 2892708 |

| ISBN: 978-5-699-84998-7 |

| Binding type: hardcover |

| Circulation: 500 |

| Name: Game with numbers. Virtuoso strategies and tactics on the football field |

| Author: C. Anderson, D. Sally |

| Additional information: per. from English. M. A. Kruse |

| Place of publication: Moscow |

| Publisher: Eksmo |

| Issue date: 2020 |

| Number of pages: 400 |

| Series: Sport inside |

| Height, see: 21 |

| Width, cm: 16. |

Some of the facts are simply amazing.

Some of the facts are simply amazing.  He is a consultant to clubs and other organizations in the global football industry.

He is a consultant to clubs and other organizations in the global football industry.

But those clubs that are fighting to win the Champions League, or the Premier League, or the national championships, look at it very differently, just like us. We are sure that every bit of knowledge that we can get helps us to love football in all its splendor even more. This is the future. It won't stop.

But those clubs that are fighting to win the Champions League, or the Premier League, or the national championships, look at it very differently, just like us. We are sure that every bit of knowledge that we can get helps us to love football in all its splendor even more. This is the future. It won't stop.  It wasn't a moment of great skill or mesmerizing beauty, it wasn't even incompetent judging. It was something more prosaic. Dave, like countless centre-backs before him, was hit by long throws from Rory Delap's out.

It wasn't a moment of great skill or mesmerizing beauty, it wasn't even incompetent judging. It was something more prosaic. Dave, like countless centre-backs before him, was hit by long throws from Rory Delap's out.  It's like a low-moving rock that intimidates defenders and confuses goalkeepers.

It's like a low-moving rock that intimidates defenders and confuses goalkeepers.