Articles about phonics

All Phonics and Decoding articles

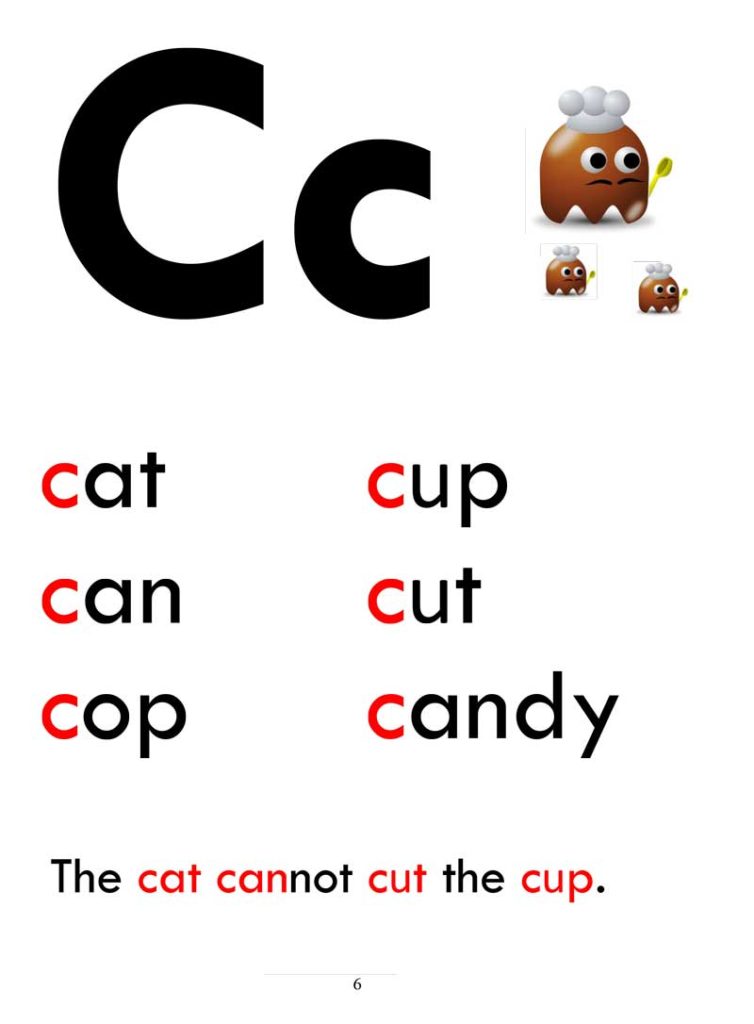

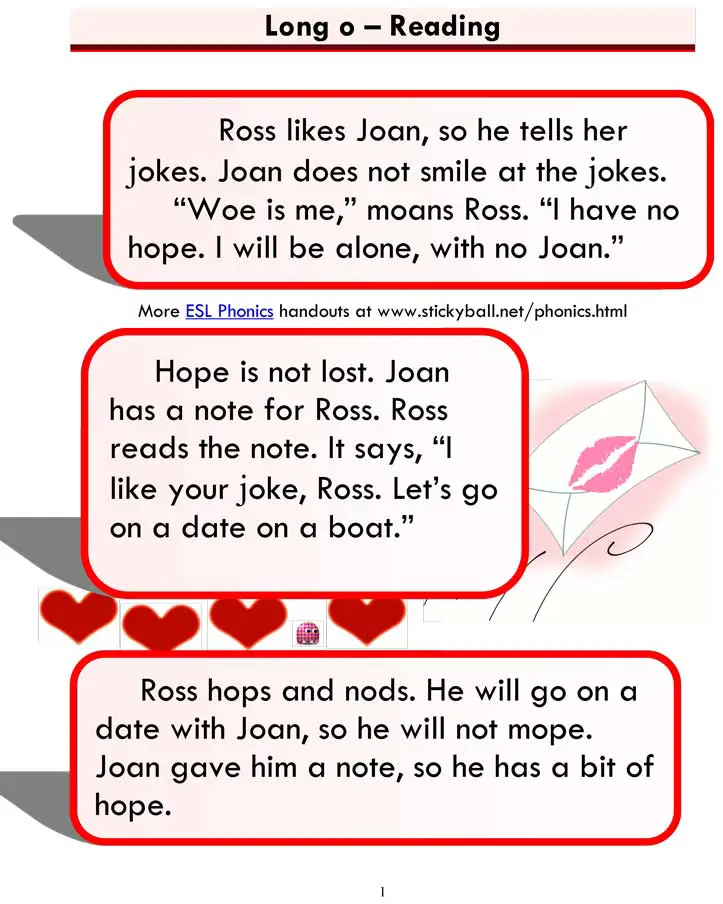

What Are Decodable Books and Why Are They Important?

By: Five From Five

Decodable books play an important role in phonics instruction and building confidence in young readers. Learn more about decodable books, how they differ from predictable texts, and how to select high-quality texts that align with the scope and sequence of your phonics program.

Decodable Text Sources

By: The Reading League

Decodable text is a type of text used in beginning reading instruction. Decodable texts are carefully sequenced to progressively incorporate words that are consistent with the letter–sound relationships that have been taught to the new reader. This list of links, compiled by The Reading League, includes decodable text sources for students in grades K-2, 3-8, teens, and all ages.

Two-to-Four-Syllable Words with Short Vowels and Schwa

By: Linda Farrell, Reading Rockets

This list can be used to help young readers practice multisyllable words with short vowel sounds and schwa sounds.

Guidance for Educators Using a Balanced Literacy Program

By: Student Achievement Partners

Improve instruction and help all students achieve at high levels by making these research-based adjustments to your balanced literacy program. This guidance outlines some of the most common challenges of a balanced literacy model, how they can impede students’ learning, and how you can adapt your reading program to better serve students.

First Rule of Reading: Keep Your Eyes on the Words

By: Linda Farrell

All kindergarten, first-grade, and second-grade teachers — as well as reading interventionists — should teach students to keep their eyes on the words on the page so that they do not have to later struggle with breaking a habit that hampers effective, efficient reading.

Helping Students Keep Their Eyes on the Words

By: Linda Farrell

An almost universal habit that struggling readers exhibit is looking up from the words when reading. Learn the three primary reasons why students look up as they read, and then find out how to respond to each case in the most effective way.

Learn the three primary reasons why students look up as they read, and then find out how to respond to each case in the most effective way.

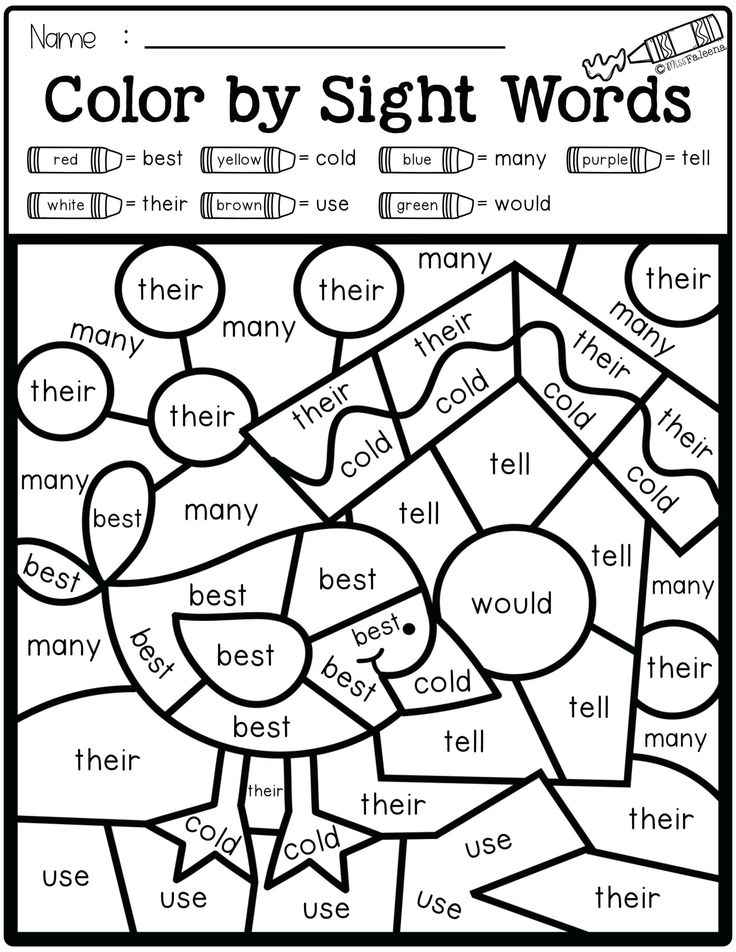

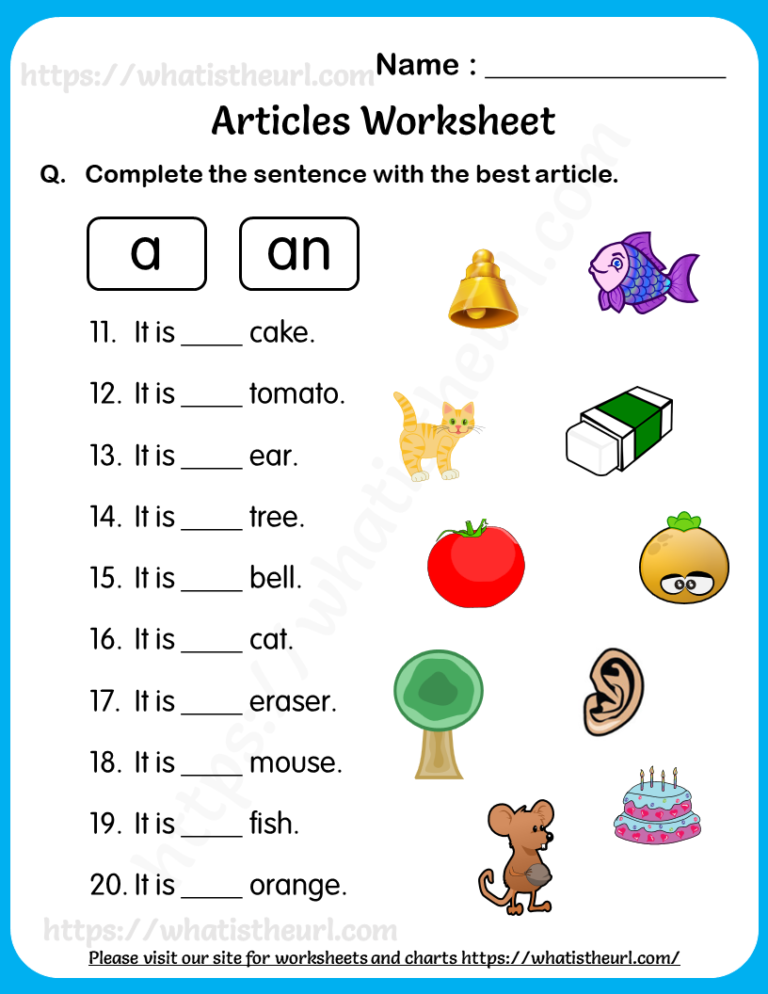

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

By: Linda Farrell, Michael Hunter, Tina Osenga

Integrating high-frequency words into phonics lessons allows students to make sense of spelling patterns for these words. To do this, high-frequency words need to be categorized according to whether they are spelled entirely regularly or not. This article describes how to “rethink” teaching of high-frequency words.

The Simple View of Reading

By: Linda Farrell, Michael Hunter, Marcia Davidson, Tina Osenga

The Simple View of Reading is a formula demonstrating the widely accepted view that reading has two basic components: word recognition (decoding) and language comprehension. Research studies show that a student’s reading comprehension score can be predicted if decoding skills and language comprehension abilities are known.

Recognizing Different Types of Readers with ASD

By: Beverly Vicker, Indiana Resource Center for Autism

Students with ASD can have strengths or challenges in either word recognition and language comprehension that will impact reading comprehension. It is important to assess, monitor, and track the word recognition or decoding skills and language comprehension skills as you evaluate reading comprehension.

Explaining Phonics Instruction

By: International Literacy Association

This ILA brief explains the basics of phonics for parents, offering guidance on phonics for emerging readers, phonological awareness, word study, approaches to teaching phonics, and teaching English learners.

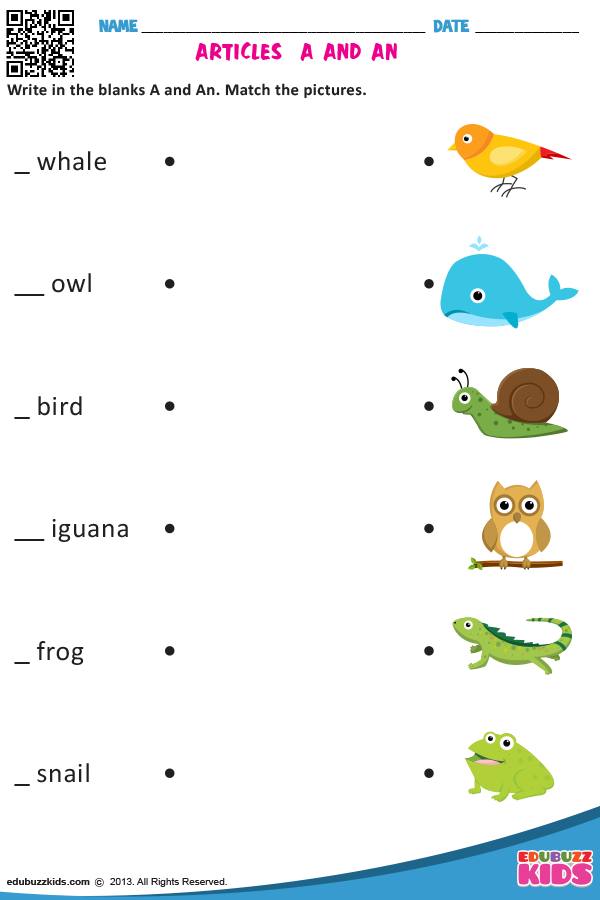

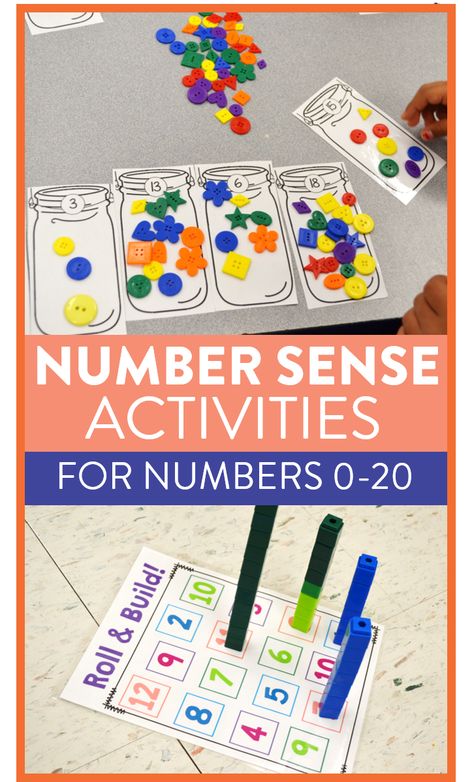

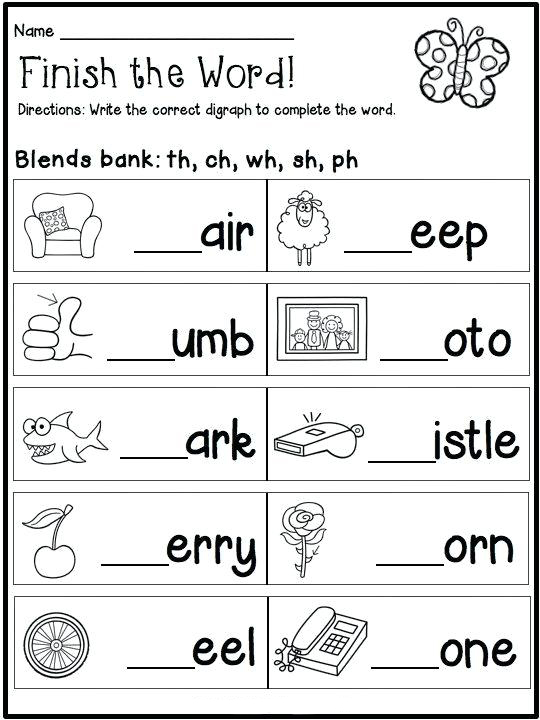

Phonics Instruction: the Value of a Multi-sensory Approach

By: Center for Effective Reading Instruction, International Dyslexia Association

Teaching experience supports a multi-sensory instruction approach in the early grades to improve phonemic awareness, phonics, and reading comprehension skills. Multi-sensory instruction combines listening, speaking, reading, and a tactile or kinesthetic activity.

Multi-sensory instruction combines listening, speaking, reading, and a tactile or kinesthetic activity.

Got a Newspaper? You’ve Got Learning!

By: Reading Rockets

Just a few pages from your newspaper can be turned into lots of early learning activities. Here you'll find "letters and words" activities for the youngest, plus fun writing prompts and tips on how to read and analyze the news for older kids.

Decoding: The Basics

By: Louisa Moats, Reading Rockets

Get the basics on guidelines for decoding instruction, speech sounds in English, and why children confuse certain speech sounds.

Environmental Print

By: Reading Rockets

Letters are all around us! Here are some ideas on how to use print found in your everyday environment to help develop your child's reading skills.

Grocery Store Literacy Activity Sheets

By: PBS KIDS Raising Readers

Everyday activities are a natural and effective way to begin teaching your young child about letters and words. Download and print these colorful "take-along" activities the next time you go to the grocery store or farmer's market. Turn your regular trip into a reading adventure!

Download and print these colorful "take-along" activities the next time you go to the grocery store or farmer's market. Turn your regular trip into a reading adventure!

Grocery Store Literacy for Preschoolers

By: Reading Rockets

A simple trip to the grocery store can turn into a real learning experience for your preschooler. Below are some easy ways to build literacy and math skills while getting your shopping done at the same time!

Eye Movements and Reading

By: Louisa Moats, Carol Tolman

Although we may not be aware of it, we do not skip over words, read print selectively, or recognize words by sampling a few letters of the print, as whole language theorists proposed in the 1970s. Reading is accomplished with letter-by-letter processing of the word.

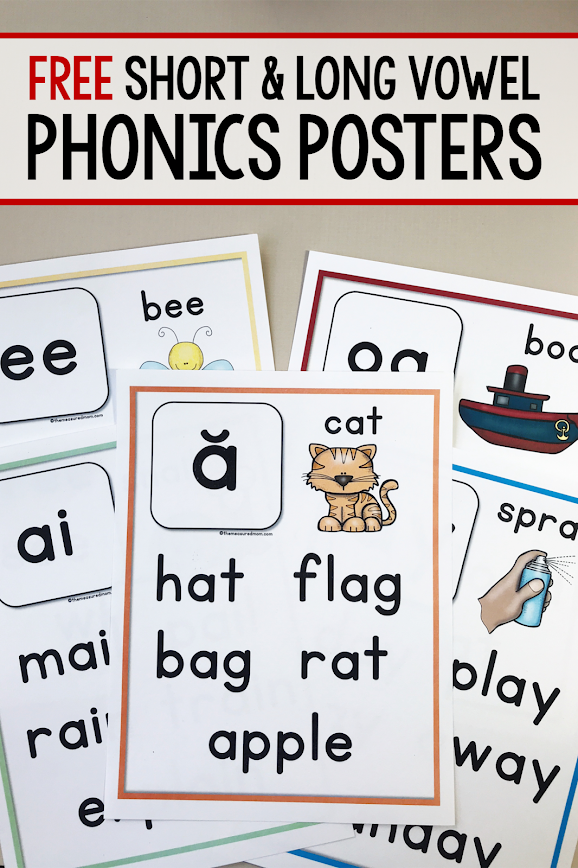

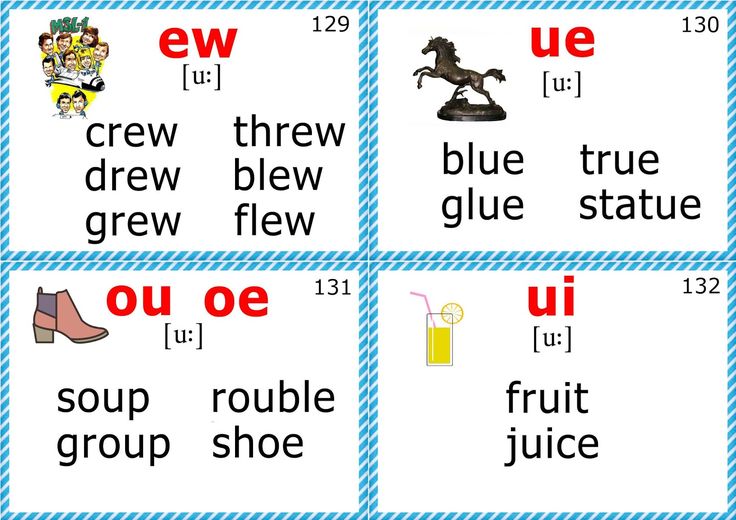

Six Syllable Types

By: Louisa Moats, Carol Tolman

Learn the six types of syllables found in English orthography, why it's important to teach syllables, and the sequence in which students learn about both spoken and written syllables.

Learning That’s Hands-On Holiday Fun (Pre-K)

By: Reading Rockets

Focus on reading readiness and enjoy winter holidays at the same time with these simple activities you can incorporate into your preschooler's daily routine.

Beginning Readers: Look! I Can Read This!

By: Reading Rockets

As a parent of a beginning reader, it's important to support your child's reading efforts in a positive way and help them along the reading path. Here's a little information about beginning readers, and a few pointers to keep in mind.

Emergent Readers: Look! That’s My Letter!

By: Reading Rockets

Even the youngest child is somewhere on the path to becoming a reader. As a parent, it's important to support your child's efforts in a positive way and help him or her along the reading path. Here's a little information about emergent readers, and a few pointers to keep in mind.

Phonics: Introduction

By: National Institute for Literacy

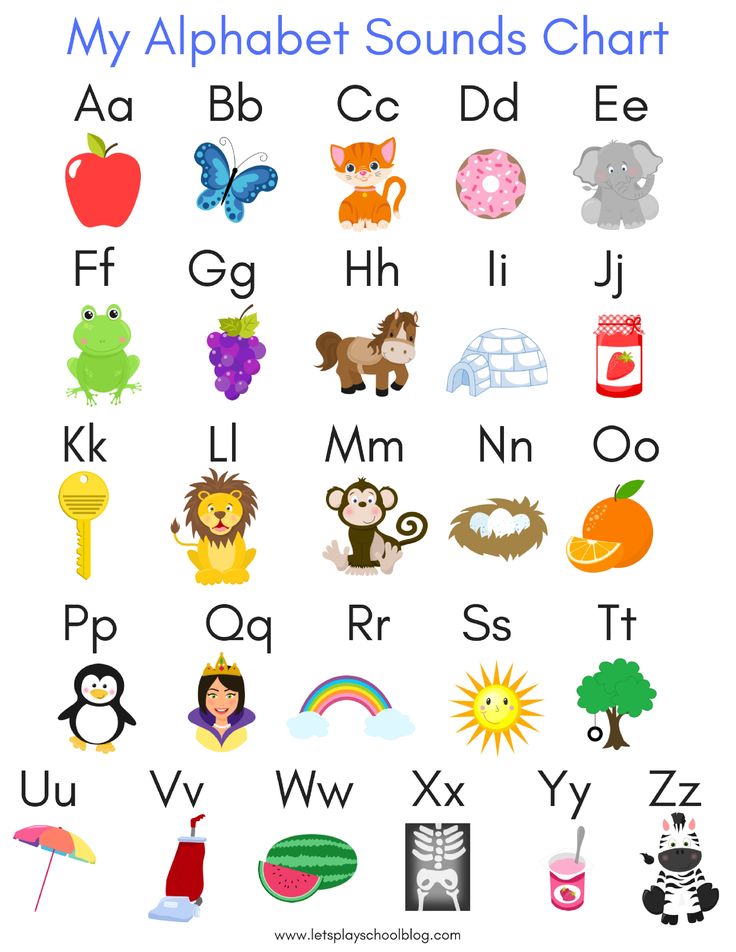

The goal of phonics instruction is to help children learn the alphabetic principle — the idea that letters represent the sounds of spoken language — and that there is an organized, logical, and predictable relationship between written letters and spoken sounds.

Phonics Instruction: The Basics

By: National Institute for Literacy

Find out what the scientific research says about effective phonics instruction. It begins with instruction that is systematic and explicit.

What Is Reading? Decoding and the Jabberwocky's Song

By: Sebastian Wren

This article illustrates the difference between being able to decode words on a page and being able to derive meaning from the words and the concepts they are trying to convey.

Phonic Elements: Assessment

By: Reading Rockets

An informal assessment of phonic elements, including what the assessment measures, when is should be assessed, examples of questions, and the age or grade at which the assessment should be mastered.

Letter/Sound (Alphabet) Recognition: Assessment

By: Reading Rockets

An informal assessment of letter/sound recognition, including what the assessment measures, when is should be assessed, examples of questions, and the age or grade at which the assessment should be mastered.

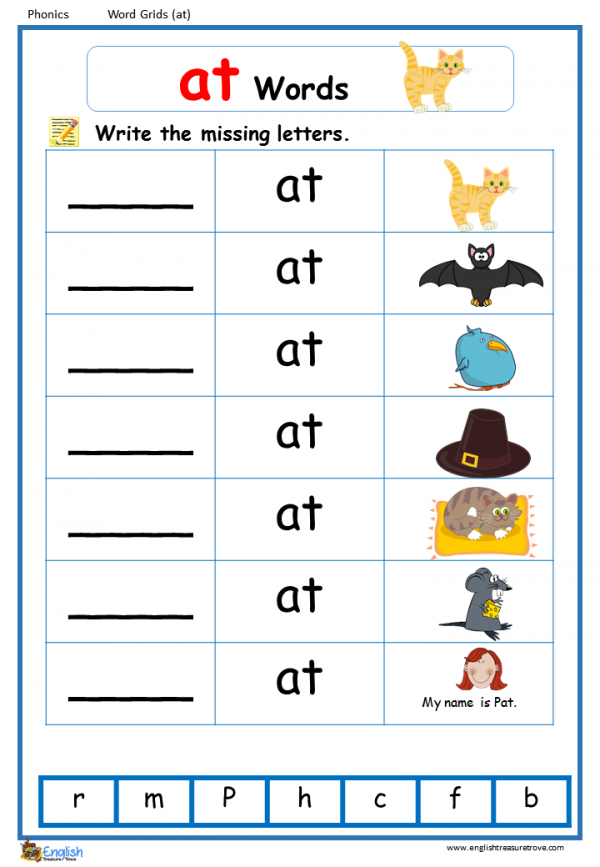

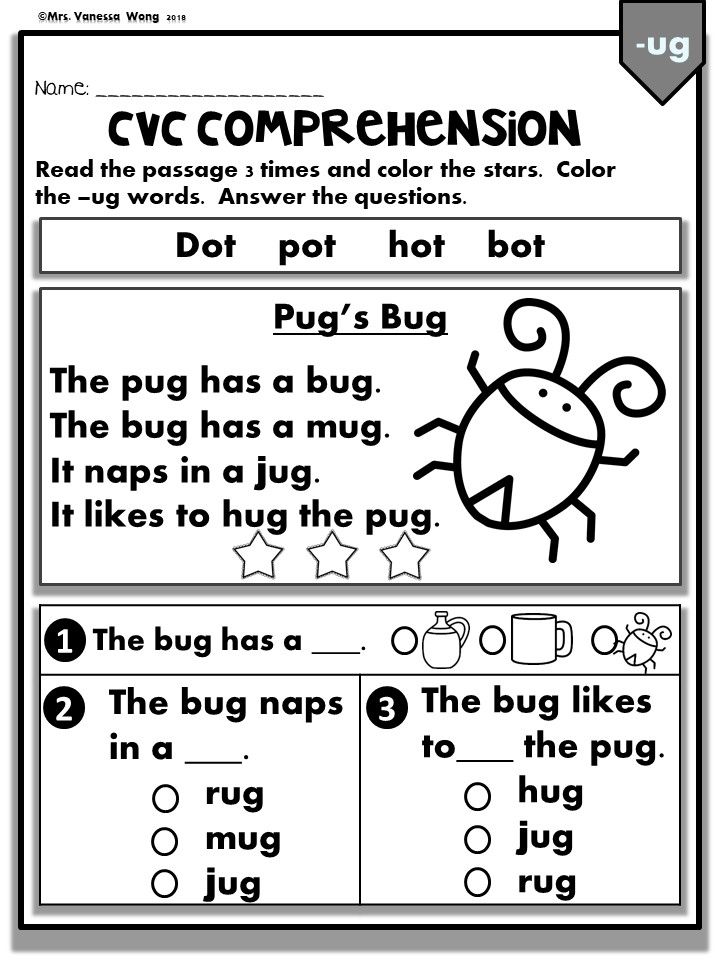

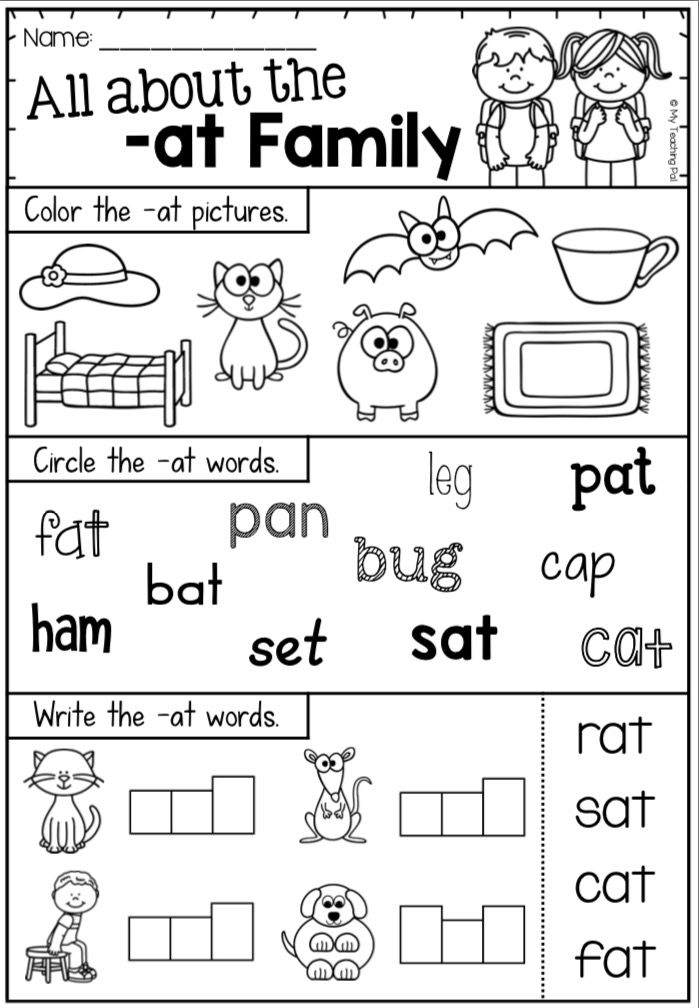

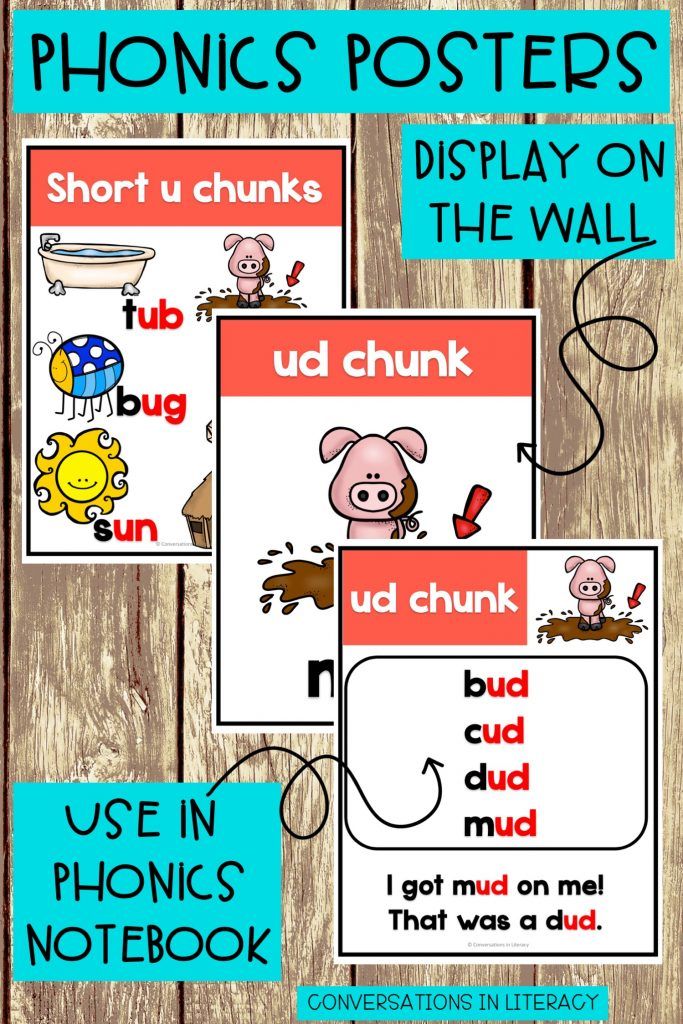

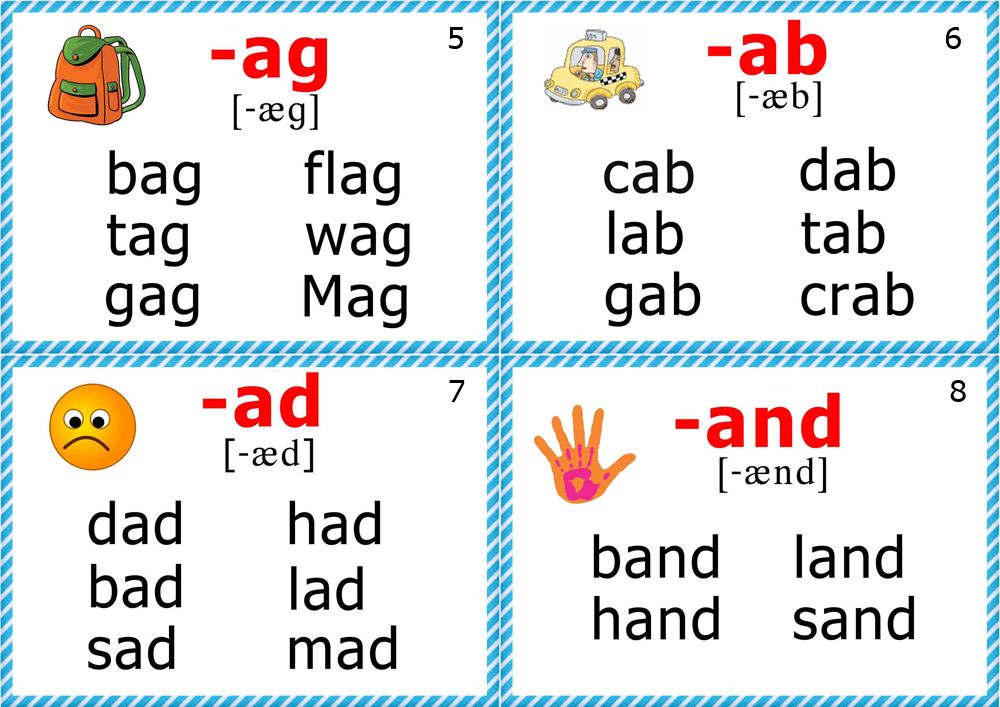

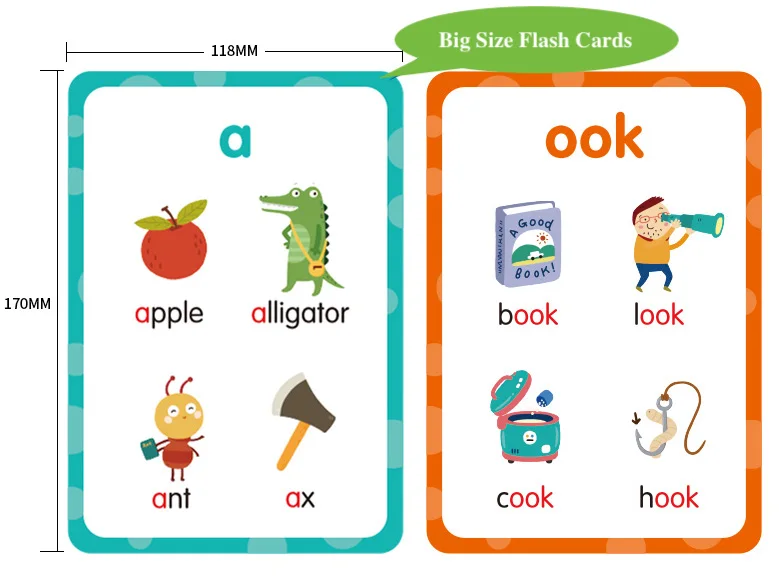

Meet the Word Families

By: Between the Lions

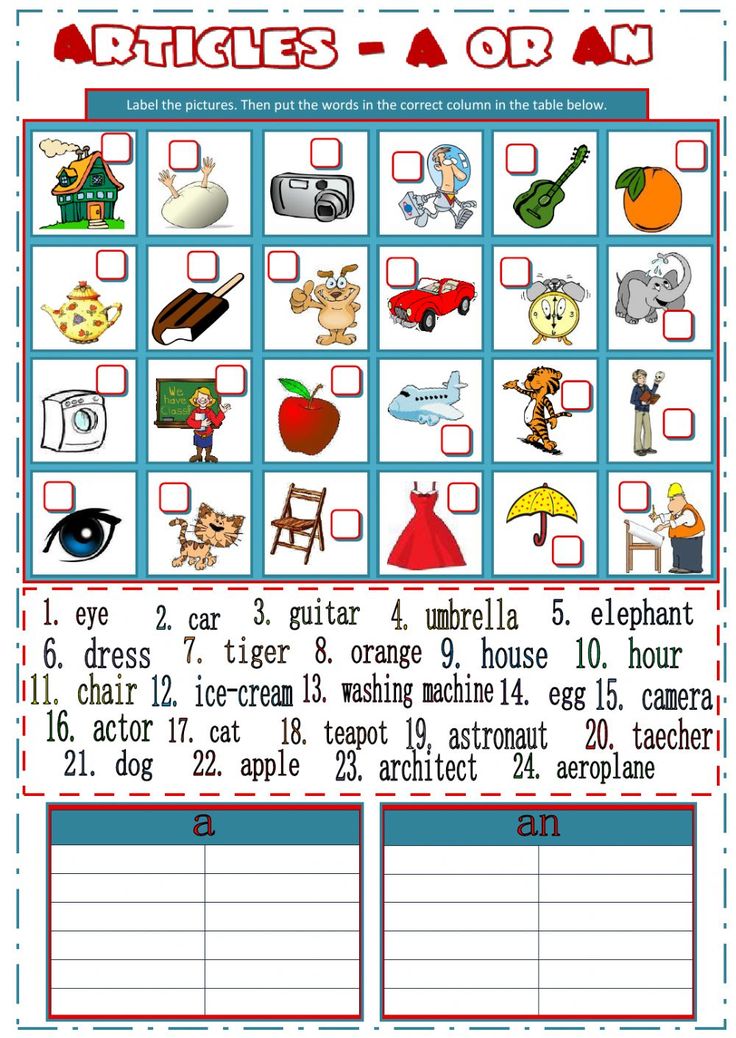

Creating a word family chart with the whole class or a small group builds phonemic awareness, a key to success in reading. Students will see how words look alike at the end if they sound alike at the end — a valuable discovery about our alphabetic writing system. They'll also see that one little chunk (in this case "-an") can unlock lots of words!

English Language Learners and the Five Essential Components of Reading Instruction

By: Beth Antunez

Find out how teachers can play to the strengths and shore up the weaknesses of English Language Learners in each of the Reading First content areas.

The Phive Phones of Reading

By: Sebastian Wren

Who can understand all the jargon that's being tossed around in education these days? Consider all the similar terms that have to do with the sounds of spoken words — phonics, phonetic spelling, phoneme awareness, phonological awareness, and phonology — all of them share the same "phon" root, so they are easy to confuse, but they are definitely different, and each, in its way, is very important in reading education.

The Alphabetic Principle

By: Texas Education Agency

Children's knowledge of letter names and shapes is a strong predictor of their success in learning to read. Knowing letter names is strongly related to children's ability to remember the forms of written words and their ability to treat words as sequences of letters.

Teaching the Alphabetic Code: Phonics and Decoding

By: Learning First Alliance

Early skills in alphabetics serve as strong predictors of reading success, while later deficits in alphabetics is the main source of reading difficulties. This article argues the importance of developing skills in alphabetics, including phonics and decoding.

This article argues the importance of developing skills in alphabetics, including phonics and decoding.

Phonics Instruction

By: National Reading Panel

Phonics instruction is a way of teaching reading that stresses the acquisition of letter-sound correspondences and their use in reading and spelling.

Tuning In to the Sounds in Words

By: Bruce Murray

Thinking about the sounds in words is not natural, but it can be fun. Here are some games children can play to develop phonemic awareness, as well as a method for segmenting words that prevents children from distorting the pronunciation of the phonemes.

Teaching Alphabetics to Kids Who Struggle

By: Mary Fitzsimmons

This article describes two processes that are essential to teaching beginning reading to students with learning disabilities: phonological awareness and word recognition, and provides tips for teaching these processes to students.

Straight Talk About Reading

By: Susan Hall, Louisa Moats

Early experiences with sounds and letters help children learn to read. This article makes recommendations for teaching phonemic awareness, sound-spelling correspondences, and decoding, and includes activities for parents to support children's development of these skills.

Goals for Kindergarten: Experimental Reading and Writing

By: National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC)

Children go through phases of reading development from preschool through third grade — from exploration of books to independent reading. In kindergarten, children develop basic concepts of print and begin to engage in and experiment with reading and writing. Find out what parents and teachers can do to support kindergarten literacy skills.

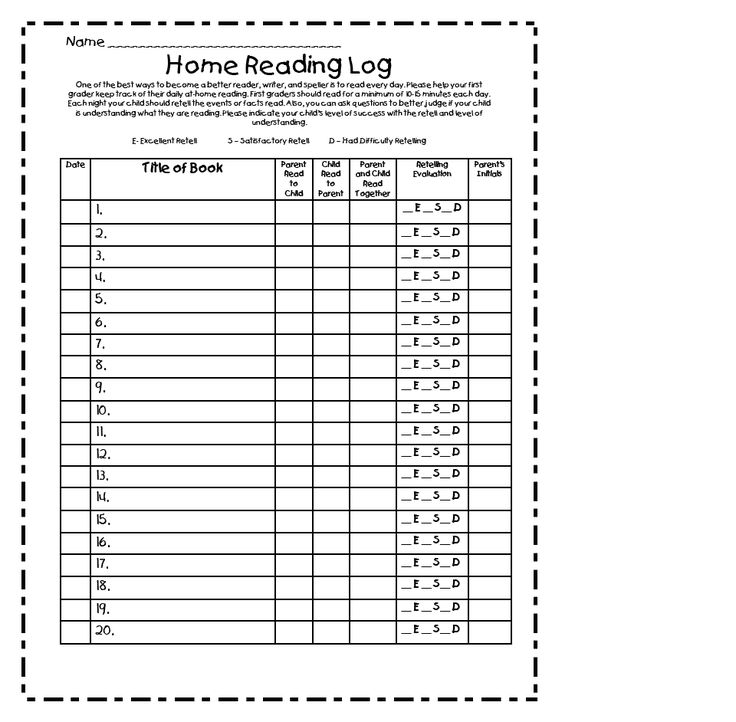

Goals for First Grade: Early Reading and Writing

By: National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC)

Children go through phases of reading development from preschool through third grade — from exploration of books to independent reading. In first grade, children begin to read simple stories and can write about a topic that is meaningful to them. Find out what parents and teachers can do to support first grade literacy skills.

In first grade, children begin to read simple stories and can write about a topic that is meaningful to them. Find out what parents and teachers can do to support first grade literacy skills.

Phonics and Word Recognition Instruction in Early Reading Programs: Guidelines for Children with Reading Disabilities

By: David J. Chard, Jean Osborn

Many teachers will be using supplemental phonics and word-recognition materials to enhance reading instruction for their students. In this article, the authors provide guidelines for determining the accessibility of these phonics and word recognition programs.

Writing and Spelling Ideas to Use with Kids

By: Texas Education Agency

As children learn some letter-sound matches and start to read, they also begin to experiment with writing. These activities can be used with children to develop their writing and spelling abilities.

Types of Informal Classroom-Based Assessment

By: Reading Rockets

There are several informal assessment tools for assessing various components of reading. The following are ten suggested tools for teachers to use.

Learning to Read, Reading to Learn

By: National Center to Improve the Tools of Educators

From decades of research about how young children can best learn to read, we know that there are core skills and cognitive processes that need to be taught. In this basic overview, you’ll find concrete strategies to help children build a solid foundation for reading.

How Do Children Learn to Read?

By: G. Reid Lyon

Learning how to read requires several complex accomplishments. Read about the challenges children face as they learn how sounds are connected to print, as they develop fluency, and as they learn to construct meaning from print.

The Foundations for Reading

By: Susan Burns, Peg Griffin, Catherine Snow

Three main accomplishments characterize good readers. Find out what these accomplishments are, and what experiences in the early years lay the groundwork for attaining them.

Sounds and Letters

By: ERIC Clearinghouse on Disabilities and Gifted Education

Early literacy activities help young children develop many skills. One of these skills is phonological awareness. Learn about phonological awareness and how parents can help children develop it.

When Older Students Can’t Read

By: Louisa Moats

These research-based reading strategies can build a foundation for reading success in students in third grade and beyond.

It’s time to stop debating how to teach kids to read and follow the evidence

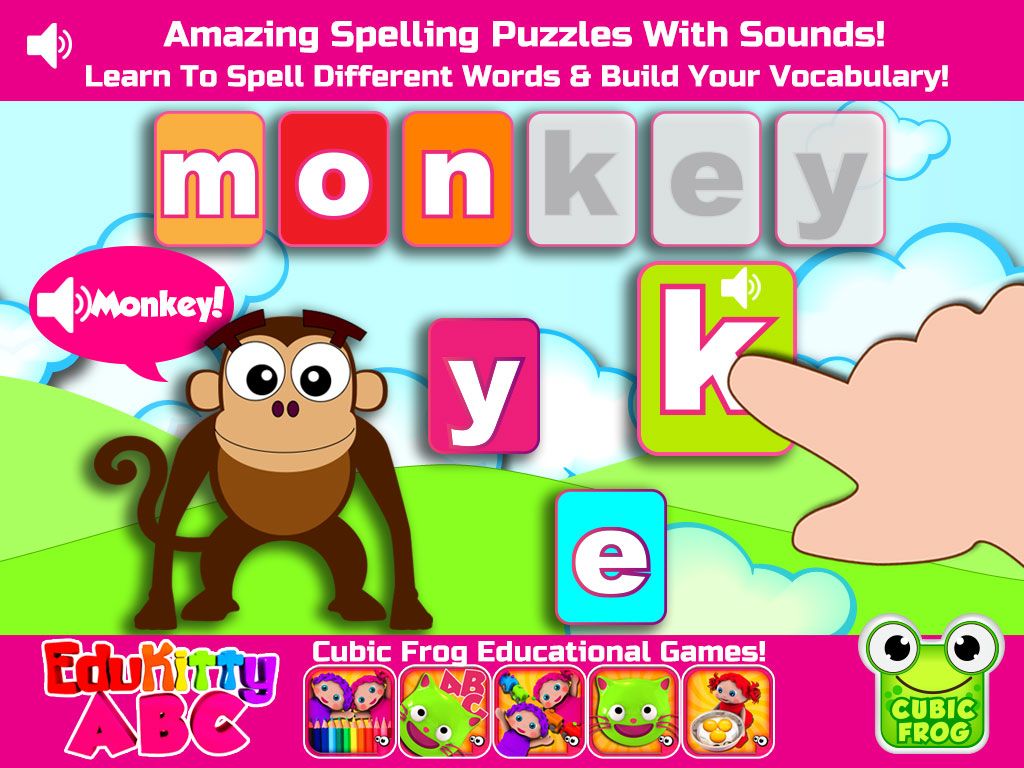

On a chilly Tuesday back in January, my 7-year-old son’s classroom in Minneapolis was humming with reading activities. At their desks, first- and second-graders wrote on worksheets, read independently and did phonics lessons on iPads. In the hallway, students took turns playing a dice game that challenged them to spell out words with a consonant-vowel-consonant structure, like wig or map.

At their desks, first- and second-graders wrote on worksheets, read independently and did phonics lessons on iPads. In the hallway, students took turns playing a dice game that challenged them to spell out words with a consonant-vowel-consonant structure, like wig or map.

In another part of the classroom, small groups of two or three children, many missing their two front teeth, took turns sitting on a color-block carpet with teacher Patrice Pavek. In one group, Pavek asked students to read out loud from a list of words. “Con-fess,” said a dimpled 7-year-old named Hazel, who sat cross-legged in purple boots and a black fleece. Pavek reminded Hazel that a vowel sound in the middle of a word changes when you put an e at the end. Hazel tried again. “Con-fuse,” she said. “Beautiful!” Pavek beamed.

When Hazel returned to her desk, I asked her what goes through her mind when she gets to a word she doesn’t know. “Sound it out,” she said. “Or go to the next word. ” Her classmates offered other tips. Reilly, age 6, said it helps to practice and look at pictures. Seven-year-old Beatrix, who loves books about unicorns and dragons, advocated looking at both pictures and letters. It feels weird when you don’t know a word, she said, because it seems like everyone else knows it. But learning to read is kind of fun, she added. “You can figure out a word you didn’t know before.”

” Her classmates offered other tips. Reilly, age 6, said it helps to practice and look at pictures. Seven-year-old Beatrix, who loves books about unicorns and dragons, advocated looking at both pictures and letters. It feels weird when you don’t know a word, she said, because it seems like everyone else knows it. But learning to read is kind of fun, she added. “You can figure out a word you didn’t know before.”

Like the majority of schools in the United States, my son’s district uses an approach to reading instruction called balanced literacy. And that puts him and his classmates in the middle of a long-standing debate about how best to teach children to read.

The debate — often called the “reading wars” — is generally framed as a battle between two distinct views. On one side are those who advocate for an intensive emphasis on phonics: understanding the relationships between sounds and letters, with daily lessons that build on each other in a systematic order. On the other side are proponents of approaches that put a stronger emphasis on understanding meaning, with some sporadic phonics mixed in. Balanced literacy is one such example.

Balanced literacy is one such example.

The issues are less black and white. Teachers and reading advocates argue about how much phonics to fit in, how it should be taught, and what other skills and instructional techniques matter, too. In various forms, the debate about how best to teach reading has stretched on for nearly two centuries, and along the way, it has picked up political, philosophical and emotional baggage.

In fact, science has a lot to say about reading and how to teach it. Plenty of evidence shows that children who receive systematic phonics instruction learn to read better and more rapidly than kids who don’t. But pitting phonics against other methods is an oversimplification of a complicated reality. Phonics is not the only kind of instruction that matters, and it is not the panacea that will solve the nation’s reading crisis.

Cutting through the confusion over how to teach reading is essential, experts say, because reading is crucial to success, and many people never learn to do it well.

According to U.S. government data, only one-third of fourth-graders have the reading skills to be considered proficient, which is defined by the National Assessment of Educational Progress as demonstrating competency over challenging subject matter. And a third of fourth-graders and more than a quarter of 12th-graders lack the reading skills to adequately complete grade-level schoolwork, says Timothy Shanahan, a reading researcher at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Those struggles tend to persist. As many as 44 million U.S. adults, or 23 percent of the adult population, lack literacy skills, according to U.S. Department of Education data. Those affected may be able to read movie listings, or the time and place of a meeting, but they can’t synthesize information from long passages of text or decipher the warnings on medication inserts. People who can’t read well are less likely than others to vote, or read the news or secure employment. And today’s technology-based job market means students need to achieve more with reading than in the past, Shanahan says. “We are failing to do that.”

“We are failing to do that.”

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

Subscribe or Donate Now

Lessons in decoding

The vast majority of children need to be taught how to read. Even among those with no learning disabilities, only an estimated 5 percent figure out how to read with virtually no help, says Daniel Willingham, a psychologist at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville and author of Raising Kids Who Read. Yet educators have not reached consensus on how best to teach reading, and phonics is the part of the equation that people still argue about most.

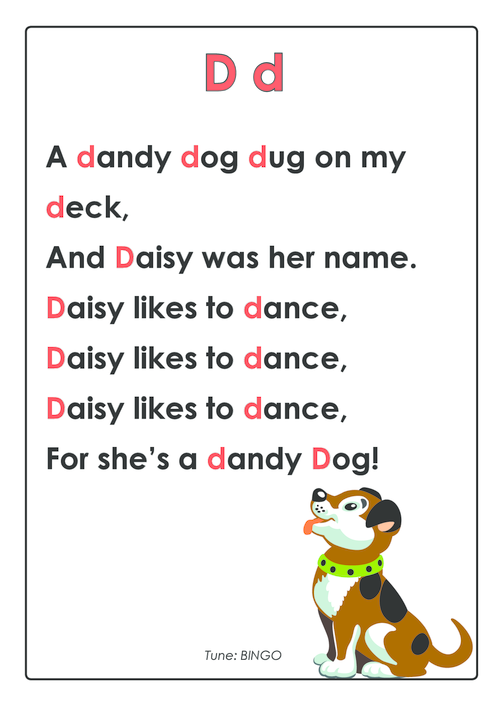

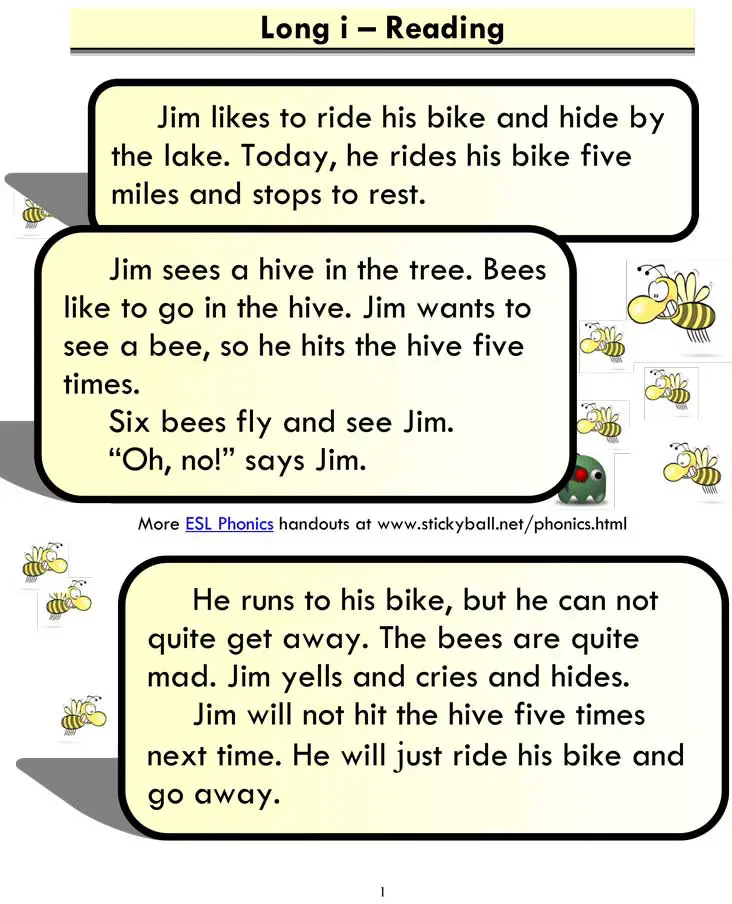

The idea behind a systematic phonics approach is that children must learn how to translate the secret code of written language into the spoken language they know. This “decoding” begins with the development of phonological awareness, or the ability to distinguish between spoken sounds. Phonological awareness allows children, often beginning in preschool, to say that big and pig are different because of the sound at the beginning of the words.

This “decoding” begins with the development of phonological awareness, or the ability to distinguish between spoken sounds. Phonological awareness allows children, often beginning in preschool, to say that big and pig are different because of the sound at the beginning of the words.

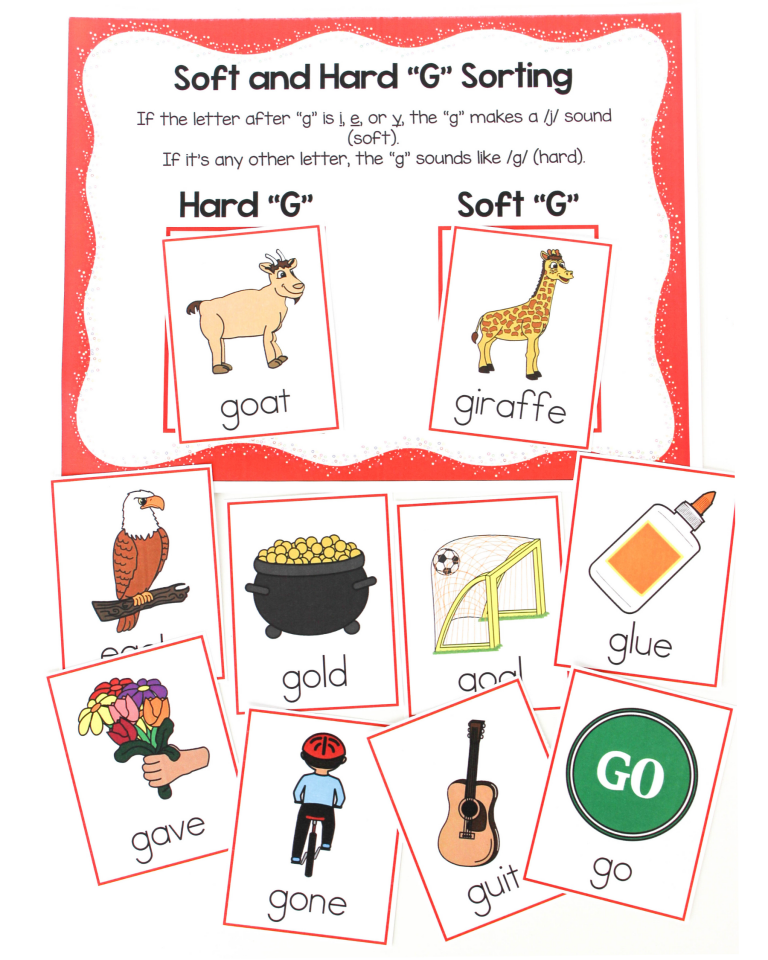

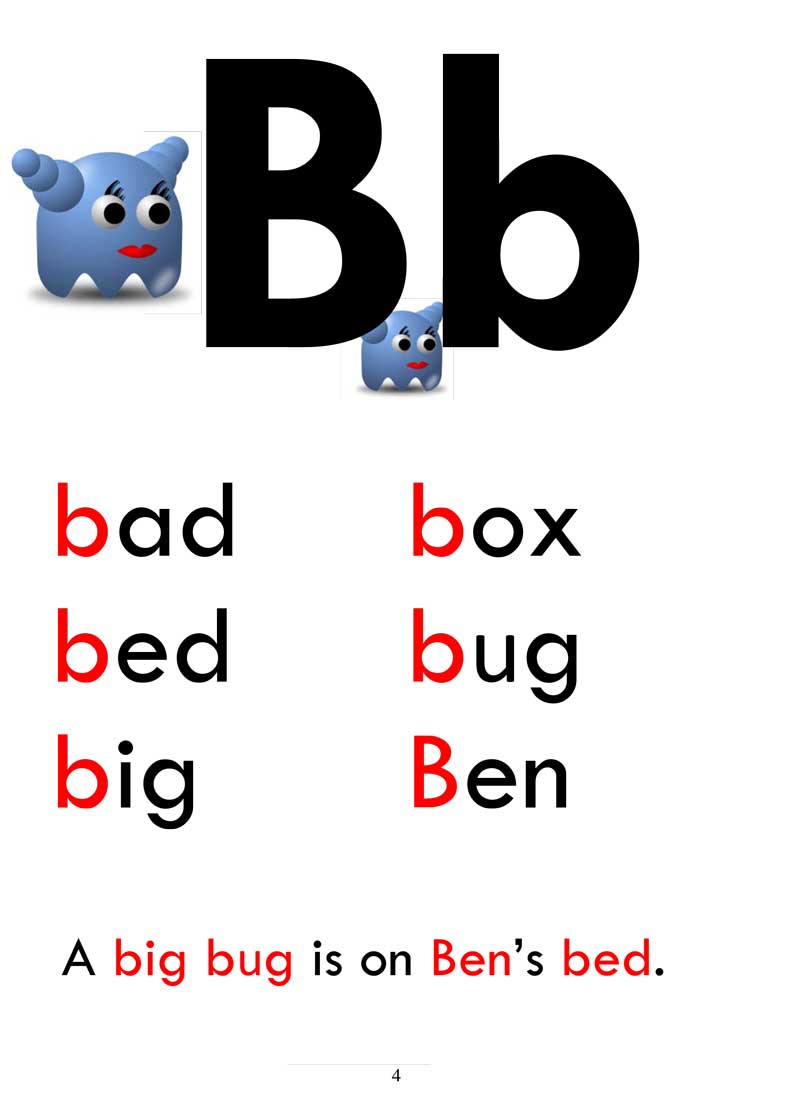

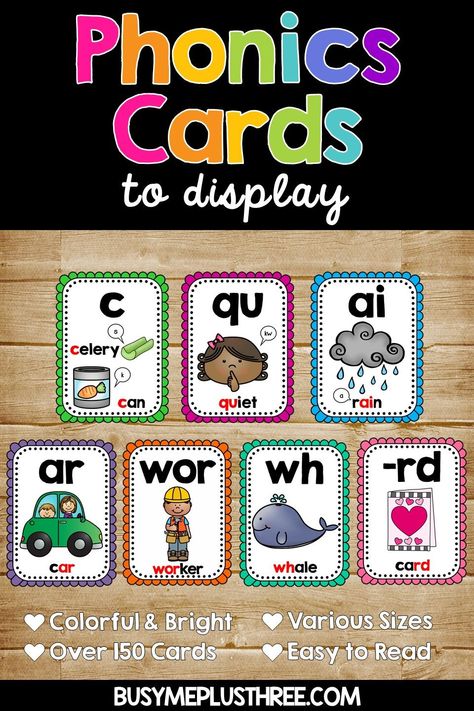

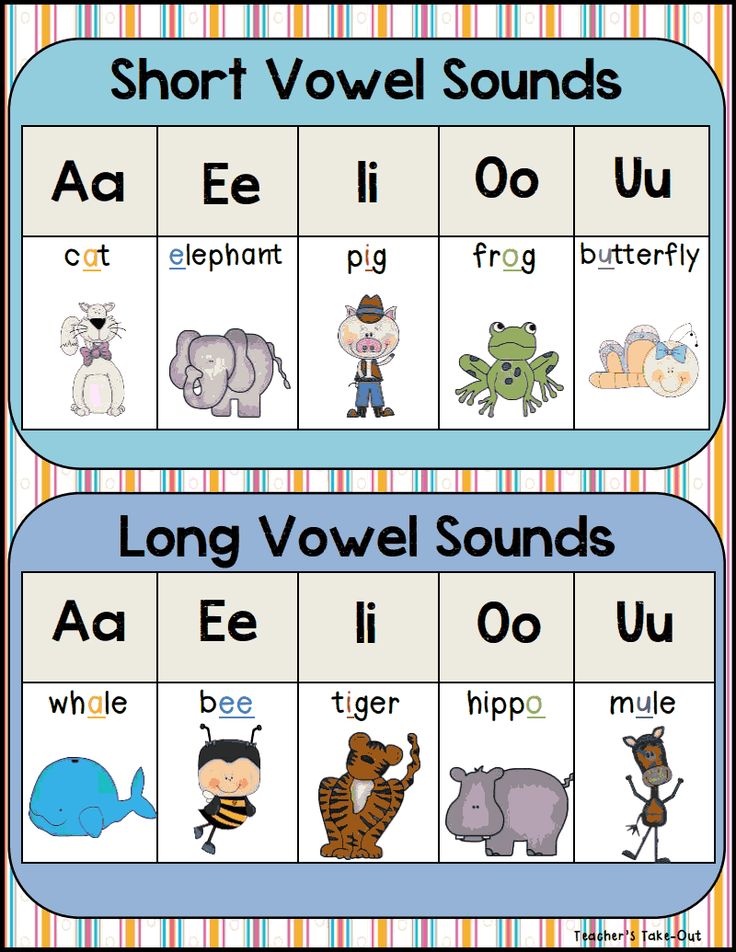

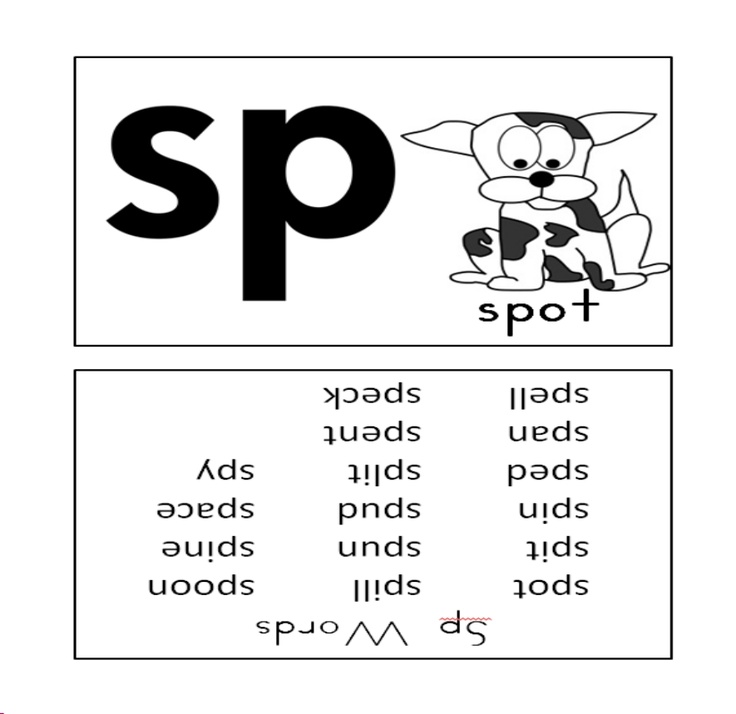

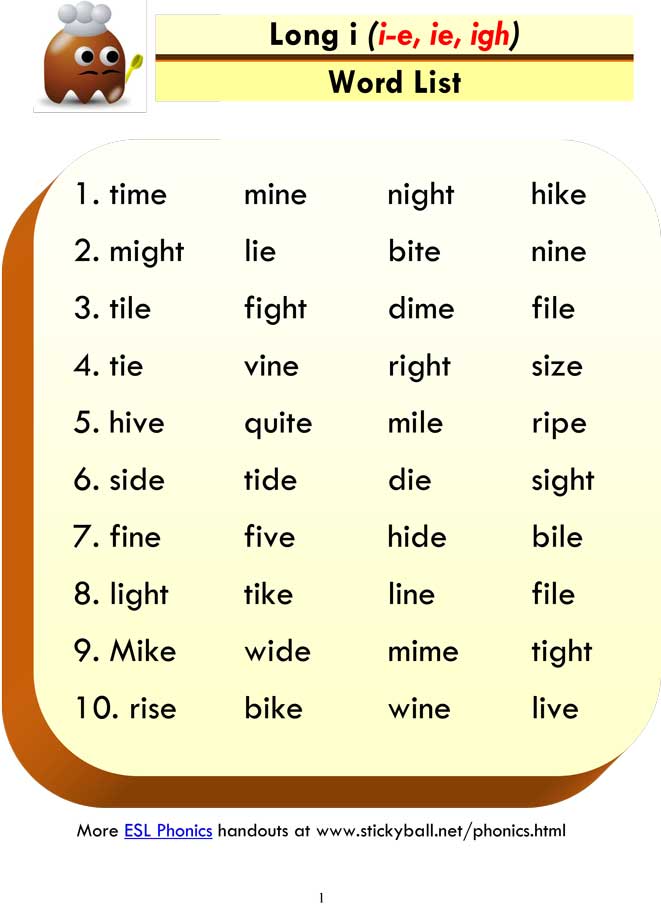

Once children can hear the differences between sounds, phonics comes next, offering explicit instruction in the connections between letters, letter combinations and sounds. To be systematic, these skills need to be taught in an organized order of concepts that build on one another, preferably on a daily basis, says Louisa Moats, a licensed psychologist and literacy expert in Sun Valley, Idaho. Today, phonics proponents often advocate for the simple view of reading, which emphasizes decoding and comprehension, the ability to decipher meaning in sentences and passages.

Support for phonics has been around since at least the 1600s, but critics have also long expressed concerns that rote phonics lessons are boring, prevent kids from learning to love reading and distract from the ability to understand meaning in text. In the 1980s, this kind of thinking led to the rise of whole language, an approach aimed at making reading joyful and immersive instead of mindless and full of effort.

In the 1980s, this kind of thinking led to the rise of whole language, an approach aimed at making reading joyful and immersive instead of mindless and full of effort.

By the 2000s, a more all-around and phonics-inclusive approach called balanced literacy was gaining popularity as the leading theory in competition with phonics-first approaches.

In a 2019 survey of 674 early-elementary and special education teachers from around the United States, 72 percent said their schools use a balanced literacy approach, according to the Education Week Research Center, a nonprofit organization in Bethesda, Md. The implementation of balanced literacy, however, varies widely, especially in how much phonics is included, the survey found. That variation is probably preventing lots of kids from learning to read as well as they could, decades of research suggests.

In the late 1990s, with the reading wars in full swing, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development brought together a panel of about a dozen reading experts to evaluate the evidence for how best to teach reading. The National Reading Panel’s first task was to figure out which types of teaching tasks to include in the analysis, says Shanahan, a panel member. Ultimately, the group chose eight categories and conducted a meta-analysis of 38 studies involving 66 controlled experiments from 1970 through 2000. The results showed support for five components of reading instruction that helped students the most.

The National Reading Panel’s first task was to figure out which types of teaching tasks to include in the analysis, says Shanahan, a panel member. Ultimately, the group chose eight categories and conducted a meta-analysis of 38 studies involving 66 controlled experiments from 1970 through 2000. The results showed support for five components of reading instruction that helped students the most.

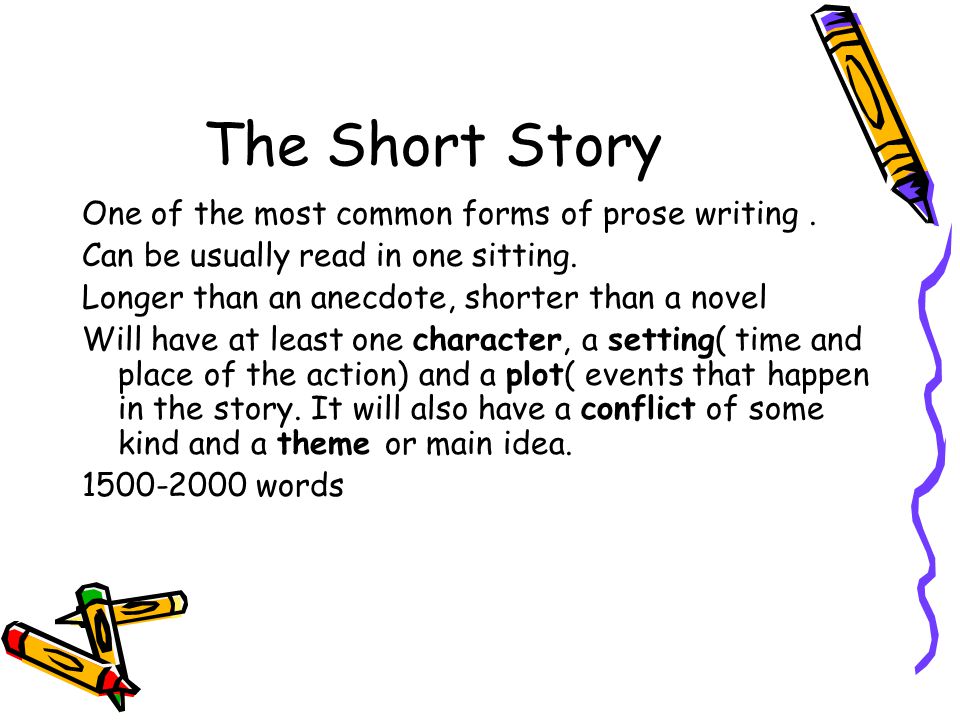

Five essentials

A meta-analysis of 38 studies found five components of reading instruction were most helpful to students.

Phonemic awareness

Knowing that spoken words are made of smaller segments of sound called phonemes

Phonics

The knowledge that letters represent phonemes and that these sounds can combine to form words

Fluency

The ability to read easily, accurately, quickly and with expression and understanding

Vocabulary

Learning new words

Comprehension

The ability to show understanding, often through summarization

Source: National Reading Panel

Two components that rose to the top were an emphasis on phonemic awareness (a part of phonological awareness that involves the ability to identify and manipulate individual sounds in spoken words) and phonics. Studies included in the analysis showed that higher levels of phonemic awareness in kindergarten and first grade were predictors of better reading skills later on. The analysis couldn’t assess the magnitude of benefits, but children who received systematic phonics instruction scored better on word reading, spelling and comprehension, especially when phonics lessons started before first grade. Those children were also better at sounding out words, including nonsense words, Shanahan says.

Studies included in the analysis showed that higher levels of phonemic awareness in kindergarten and first grade were predictors of better reading skills later on. The analysis couldn’t assess the magnitude of benefits, but children who received systematic phonics instruction scored better on word reading, spelling and comprehension, especially when phonics lessons started before first grade. Those children were also better at sounding out words, including nonsense words, Shanahan says.

Vocabulary development was another essential component, as was a focus on comprehension. The final important facet was a focus on achieving fluency — the ability to read a text quickly, accurately and with proper expression — by having children read out loud, among other strategies.

Even before the panel released its results in 2000, numerous studies and books from as early as the 1960s had concluded that there was value in explicit phonics instruction. Studies since then have added yet more support for phonics.

In 2008, the National Early Literacy Panel, a government-convened group that included Shanahan, considered dozens of studies on phonological awareness (including phonemic awareness) plus phonics instruction in preschool and kindergarten. Children who got decoding instruction scored substantially better on tests of phonological awareness compared with those who didn’t. The benefit was equivalent to a jump from the 50th percentile to the 79th percentile on standardized tests, suggesting those students were better prepared to learn how to read.

Likewise, a 2007 meta-analysis of 22 studies conducted in urban elementary schools found that minority children who received phonics instruction scored the equivalent of several months ahead of their minority peers on several academic measures. Studies have not addressed whether phonics might help close demographic achievement gaps, but research suggests that whole language approaches are less effective in disadvantaged populations than in other groups.

“There are several thousand studies at least that converge on this finding,” Moats says. “Phonics instruction has always had the edge in consensus reports.”

It is difficult to quantify how substantial the gains are from explicit phonics instruction, partly because the bulk of published research is full of ambiguities. Randomized trials are rare. Studies tend to be small. And in schools where teachers have autonomy to respond to students at their discretion, control groups are often not well-defined, making it hard to tell what phonics-focused programs are really being compared with, or how much phonics the control groups are getting. The reality of instruction can differ from classroom to classroom, even within the same school. And students who aren’t getting intensive phonics at school may have the blanks filled in at home, where parents might sound out words and talk about letters while reading bedtime stories.

The data that are available suggest that kids who get systematic phonics lessons score the equivalent of about half a grade level ahead of kids in other groups on standardized tests, Shanahan says. That’s not a giant leap, but it helps. “Overwhelmingly in studies, both individually and in a meta-analysis where you’re combining results across studies, if you explicitly teach phonics for some amount of time, kids do better than if you don’t pay much attention to that or if you pay a little bit of attention to [phonics],” he says.

That’s not a giant leap, but it helps. “Overwhelmingly in studies, both individually and in a meta-analysis where you’re combining results across studies, if you explicitly teach phonics for some amount of time, kids do better than if you don’t pay much attention to that or if you pay a little bit of attention to [phonics],” he says.

Real experiences

Some of the most compelling evidence to support a phonics-focused approach comes from historical observations: When schools start teaching systematic phonics, test scores tend to go up. As phonics took hold in U.S. schools in the 1970s, fourth–graders began to do better on standardized reading tests.

In the 1980s, California replaced its phonics curriculum with a whole language approach. In 1994, the state’s fourth-graders tied for last place in the nation: Less than 18 percent had mastered reading. After California re-embraced phonics in the 1990s, test scores rose. By 2019, 32 percent achieved grade-level proficiency.

Those swings continue today. In 2019, Mississippi reported the nation’s largest improvement in reading scores; the state had started training teachers in phonics instruction six years earlier. For the first time, Mississippi’s reading scores matched the nation’s average, with 32 percent of students showing proficiency, up from 22 percent in 2009, making it the only state to post significant gains in reading in 2019.

England, too, started seeing dramatic results after government-funded schools were required in 2006 to teach systematic phonics to 5- to 7-year-olds. When the country implemented a test to assess phonics skills in 2012, 58 percent of 5- and 6-year-olds passed. By 2016, 81 percent of students passed. Reading comprehension at age 7 has risen, and gains seem to persist at age 11. These population trends make a strong case for teaching phonics, says Douglas Fuchs, an educational psychologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

A boost with phonics

After adding explicit phonics instruction statewide in 2013, Mississippi reported the nation’s largest improvement in reading scores among fourth-graders.

Mississippi fourth-grade reading proficiency

E. OtwellSource: National Assessment of Educational Progress 2019

Despite the evidence that children learn to read best when given systematic phonics along with other key components of a literacy program, many schools and teacher-training programs either ignore the science, apply it inconsistently or mix conflicting approaches that could hinder proficiency. In the 2019 Education Week Research Center survey, 86 percent of teachers who train teachers said they teach phonics. But surveyed elementary school teachers often use strategies that contradict a phonics-first approach: Seventy-five percent said they use a technique called three cuing. This method teaches children to guess words they don’t know by using context and picture clues, and has been criticized for getting in the way of learning to decode. More than half of the teachers said they thought students could understand written passages that contained unfamiliar words, even without a good grasp of phonics.

The disconnect starts at the top. In a 2013 review of nearly 700 teacher-training institutions, only 29 percent required teachers to take courses on four or five of the five essential facets of reading instruction identified by the National Reading Panel. Almost 60 percent required teachers to complete coursework on two or fewer of the essentials, according to the National Council on Teacher Quality, a research and policy group based in Washington, D.C.

Teacher’s choice

In a random sample of almost 700 U.S. early-elementary and special education teachers, most reported using a method called balanced literacy to teach reading. The simple view of reading, focused on phonics, was a distant second.

Balanced literacy

Instruction includes a bit of everything, usually with some phonics.

Simple view

The emphasis is on phonics, with a focus on two skills: decoding and language comprehension.

Whole language

Instruction emphasizes whole words and phrases in meaningful contexts, including a strategy called three cuing.

How U.S. educators teach reading

E. OtwellSource: EdWeek Research Center 2020

In 2019, the Education Week Research Center also surveyed 533 postsecondary educators who train teachers on how to teach reading. Only 22 percent of those educators said their philosophy was to teach explicit, systematic phonics. Almost 60 percent said they support balanced literacy. And about 15 percent thought, contrary to evidence, that most students would learn to read if given the right books and enough time.

“The majority of classrooms in this country continue to embrace instructional practices and programs that do not include systematic instruction in foundational skills like phonemic awareness and phonics and spelling,” Moats says. “They just don’t do it.”

At my son’s Minneapolis school, reading specialist Karin Emerson told me about her early days teaching kindergarten, first and second grades in the 1990s. She was trained to use a whole language approach that included the three cuing technique.

Emerson described a typical reading lesson: “I’m going to show you a big book, and I’m going to cover up all of the letters of the word except the b, and I’m going to say, ‘Look at this page. It says this is a …’ What do you think it’s going to say?” Then she would point out the butterfly in the picture and ask the students to think about whether the b sound could refer to anything in the picture. “What does butterfly start with? A ‘b-uh.’ Do you think it’s going to be butterfly? I think it is going to be butterfly. It is.”

Eight years later, Emerson switched from classroom teacher to reading specialist, helping third-graders who weren’t reading yet. Many were the same students she had taught to read in younger grades. After reviewing the reading research, she implemented systematic phonics. By the end of third grade, students in her groups advanced an average of two grade levels. She now encourages early-grade teachers to add at least 20 minutes of phonics a day into literacy lessons.

Looking back to her classroom-teaching days, Emerson says parents often told her they were concerned that their children weren’t reading yet. “I would say, ‘Oh, they’ll be fine because they’re well spoken, they’re bright and you’re reading to them.’ Well they weren’t fine,” Emerson says. “Some people learn how to read super easy, and that’s great. But most people need to be taught, and there’s a pretty big chunk who need to be taught in a systematic way.”

While learning about ongoing battles over reading instruction, I have been marveling at my son’s transformation from nonreader to reader. One recent afternoon, he came home from school and told me that he had learned how to spell the word “A-G-A-I-N.” I asked him how he would spell it if it looked like it sounded. He worked it out, one sound at a time: “U-G-E-N.” We agreed the English language is pretty strange. It’s amazing anyone learns to read it at all.

This is your brain on reading

Reading is a relatively new activity for the human brain, which hasn’t had time to evolve specialized areas devoted to the task. Instead, our brains enlist areas, such as the visual system, that originated for other reasons, says Guinevere Eden, a neuroscientist at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. An object like a tree or a lion needs to be recognizable from any angle, she says. But when we read, we need to override that kind of pattern recognition to distinguish, say, b from d, two letters that look identical to a beginning reader.

Instead, our brains enlist areas, such as the visual system, that originated for other reasons, says Guinevere Eden, a neuroscientist at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. An object like a tree or a lion needs to be recognizable from any angle, she says. But when we read, we need to override that kind of pattern recognition to distinguish, say, b from d, two letters that look identical to a beginning reader.

To translate squiggles and dots into sounds, several key brain areas, in both the visual and language systems, get involved. And how involved those areas are during reading shifts with increasing mastery, according to brain-imaging studies from the last two decades. When early or experienced readers sound out an unfamiliar word, they tap into the posterior and superior temporal lobes and inferior parietal lobe, which are involved in language and sensory processing. When the brain encounters a familiar word, on the other hand, the visual cortex takes over, suggesting that known words become like any other object that the brain recognizes instantly. As a person’s reading skills improve and the mental menu of familiar words grows, activity is more pronounced in the visual cortex during reading, Eden says.

As a person’s reading skills improve and the mental menu of familiar words grows, activity is more pronounced in the visual cortex during reading, Eden says.

Eden uses brain scans to understand what goes wrong in children with reading disabilities, who have trouble sounding out words. One of her goals is to evaluate interventions for children with dyslexia to see if the interventions target the brain processes that are most impaired.

Despite heavy marketing by companies that sell reading products using brain scans as evidence that the companies’ methods help children learn to read, Eden says that imaging studies cannot yet answer questions about which types of reading instruction are best for children, with or without reading disabilities.

Article on the Russian language on the topic: Phonetics read

Home>Articles on the Russian language

The section of linguistics where the sound side or structure of the language is studied is called phonetics. In writing, graphic signs are used, in oral communication - sound. They are material and thanks to this quality, speech has become accessible to human perception. The sound system is a special tier in its structure. And phonetics has its own separate subject in linguistics. If we do not know it, we will not understand modern writing, we will not be able to understand grammar correctly. Unfortunately, little attention is paid to phonetics in the school curriculum, so letters and sounds are often confused, which leads to an incorrect presentation of grammar.

Phonetics, even despite the major achievements of linguists and scientists in this field of linguistics, has recently become one of the sciences of language.

Linguistics, as one of the sciences, studies the classification of sounds, but not much attention was paid to the sound side. Recently, with the urgent need to compile the grammar of other (native) languages in different colonies, in the study of historical descriptions of languages and descriptions of their groups, as well as in the study of dialects (non-written), this science began to develop much more strongly. Now there is already a new experimental phonetics created not so long ago, which is used thanks to sound recording instruments. Now it has become possible not “by ear”, but absolutely objectively and accurately to make observations, including studying the similarities and differences of sounds already from graphic recordings on a special ferromagnetic tape. Thanks to the progress in the development of this natural science, it began to be considered more seriously.

Acoustics. One of the subsections of phonetics is acoustics. The general theory is studied by the branch of physics. From a scientific point of view, sound is the result of an oscillatory movement of a body in some medium, it is carried out under the action of a driving force, and must be accessible to hearing. The body can be of any kind: solid - clap your hands, liquid - splashing water, gaseous - hear the sound of a shot. In this case, the environment acts as a conductor of sound to the organ of perception itself. Everyone knows that airless space cannot produce sound. Acoustics in sound is characterized by the following features:

1. Height (depending on a quantity such as frequency). The higher it is, the higher the sound itself. The human ear distinguishes the pitch of the sound within the following limits (sixteen - twenty Hz). Anything below this limit is called infrasound, and anything above that is called ultrasonic. Neither one nor the other is perceived by humans, but dogs, foxes, bats and dolphins perceive ultrasounds.

2. Force depending on the range (amplitude) of vibrations. The stronger or larger the swing, the stronger the sound will be.

3. Longitude or duration (this applies more to vowels, as they are longer under stress than unstressed ones, but only in Russian).

4. The timbre of sounds (this refers to the individual qualities of acoustic features).

Articulation has the following components: the classification of sounds and the work of the organs of speech, which is aimed at reproducing sounds. It also has three main parts:

- an attack (excursion) of sound, when the organs begin to work;

- medium (exposure), when the organs are already fully established for articulation.

see also:

All articles on the Russian language

PHONETICS • Great Russian Encyclopedia

Authors: L. R. Zinder

PHONETICS . Unlike other linguists. disciplines, F. explores not only the language function, but also the material side of his object: he pronounces the work. apparatus (see Organs of speech), as well as acoustic. characterization of sound phenomena and their perception by native speakers. Modern F. distinguishes 4 aspects in the sound of speech (see Sounds of speech): functional (or linguistic), articulatory, acoustic, and perceptual. F. associated with such non-linguistic. disciplines such as the anatomy and physiology of speech production and speech perception, on the one hand, and speech acoustics, on the other. Like linguistics in general, F. is associated with psychology, since speech activity is part of the mental. human activity.

F. associated with such non-linguistic. disciplines such as the anatomy and physiology of speech production and speech perception, on the one hand, and speech acoustics, on the other. Like linguistics in general, F. is associated with psychology, since speech activity is part of the mental. human activity.

In contrast to the non-linguistic disciplines, F. considers sound phenomena as elements of a language system that serve to translate words and sentences into a material sound form, without which communication is impossible. Outside of this function, the sound side of the language cannot be understood; even otd. the sound of speech is distinguished from the sound chain only as a representative of the phoneme, i.e., due to its connections with the semantic units of the language. The data of modern speech acoustics indicate that the elements of the division of the sound sequence, carried out by the most advanced acoustic. methods do not coincide with the sounds of speech as realizations of phonemes.

In accordance with the fact that the sound side of the language can be considered in the acoustic-articulatory and functional-linguistic aspects, in phonetics, Ph. proper and phonology are distinguished. Dividing them into 2 independent. section of linguistics pl. modern linguists consider it illegal.

There is a general F. and a private F. (or F. of separate languages). General Ph. studies the general conditions of sound formation, based on the possibilities of pronouncing. apparatus of a person (for example, labial, anterior-lingual, posterior-lingual consonants are distinguished, if we mean pronounces. The organ that determines the main features of the consonant, or occlusive, slotted, if we mean the method of forming the barrier necessary for the articulation of the consonant for the air jet leaving the lungs ), and also analyzes the acoustic features of sound units, their spectral characteristics, for example. the presence or absence of voice tone (zero formant) when pronouncing different types of consonants, different position of formants in the formation of vowels. Universal classifications of speech sounds (vowels and consonants) are being built, which are based partly on articulatory, partly on acoustic. signs, as well as classification by differential signs. General phrasing also studies the patterns of combinations of sounds, the influence of the characteristics of one of the adjacent sounds on another (various types of accommodation or assimilation), and coarticulation; the nature of the syllable, the laws of combining sounds into syllables and the factors that determine syllable division; phonetic organization of the word, in particular stress and synharmonism. She studies the means that are used for intonation: the height of the main. tone of voice, strength (intensity), duration of otd. parts of a sentence, the speed of their pronunciation (tempo; see the rate of speech), pauses and timbre.

Universal classifications of speech sounds (vowels and consonants) are being built, which are based partly on articulatory, partly on acoustic. signs, as well as classification by differential signs. General phrasing also studies the patterns of combinations of sounds, the influence of the characteristics of one of the adjacent sounds on another (various types of accommodation or assimilation), and coarticulation; the nature of the syllable, the laws of combining sounds into syllables and the factors that determine syllable division; phonetic organization of the word, in particular stress and synharmonism. She studies the means that are used for intonation: the height of the main. tone of voice, strength (intensity), duration of otd. parts of a sentence, the speed of their pronunciation (tempo; see the rate of speech), pauses and timbre.

In private Ph., all these problems are considered in relation to this particular language and through the prism of functions that this or that phonetic. phenomenon or unit perform. Particular Ph. can be descriptive, or synchronous (see Synchrony), and historical, or diachronic (see Diachrony ), studying the evolution of the sound structure of a given language or group of languages.

phenomenon or unit perform. Particular Ph. can be descriptive, or synchronous (see Synchrony), and historical, or diachronic (see Diachrony ), studying the evolution of the sound structure of a given language or group of languages.

Phonetic and phonological. aspects represent a single whole in private phraseology, since all sound units are distinguished indirectly through the semantic units of the language.

Experiments are widely used in F. methods; since special devices are used, these methods are also called instrumental. Applied, in addition, dec. methods for studying the perception of certain sound phenomena by native speakers, which is especially important for phonological. interpretation of these phenomena. Since the 1980s F. uses computers.

F. is of applied importance in various areas: for the rationalization of writing (graphics and spelling), teaching correct pronunciation, especially in a non-native language, for diagnosing the correction of speech deficiencies (speech therapy and deaf education). F.'s data is used to check the means of communication and to improve their efficiency, as well as for automatic. speech recognition.

F.'s data is used to check the means of communication and to improve their efficiency, as well as for automatic. speech recognition.

The beginning of the study of the mechanism of formation of speech sounds dates back to the 17th century; it was caused by the needs of teaching the deaf and dumb [works by H. P. Bonet (Spain), J. Wallis (Great Britain), I. K. Amman (Netherlands)]. In con. 18th century H. Krazenshtein (Germany, Russia) laid the foundation for acoustic. theory of vowels, which was developed in the middle. 19th century G. L. F. Helmholtz. K ser. 19th century research in the field of anatomy and physiology of sound production was summarized in the works of E. W. Brücke (Germany). From a linguistic point of view, the doctrine of the sound side of the language in all its sections is first presented in the work of him. linguist E. Sievers "Grundzüge der Lautphysiologie" (1876; 2nd edition - under the title "Grundzüge der Phonetik" - 1881). An important role in the development of F.