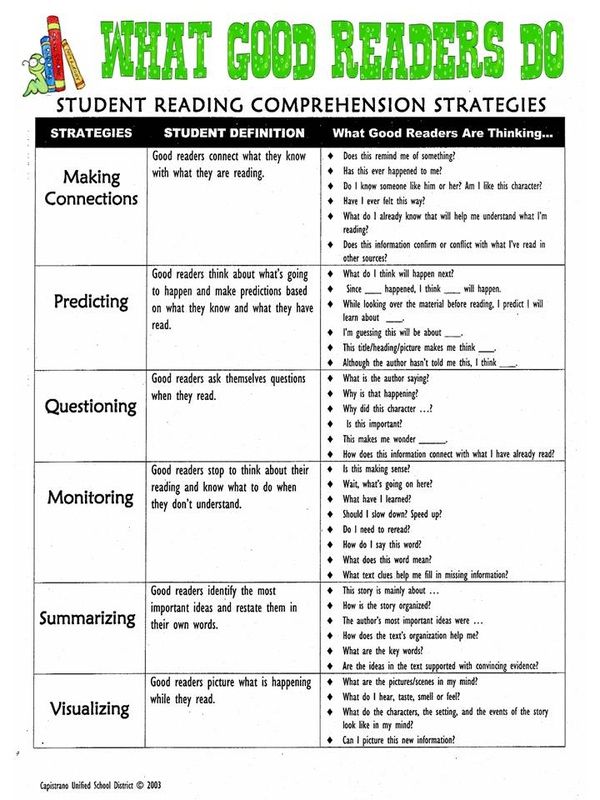

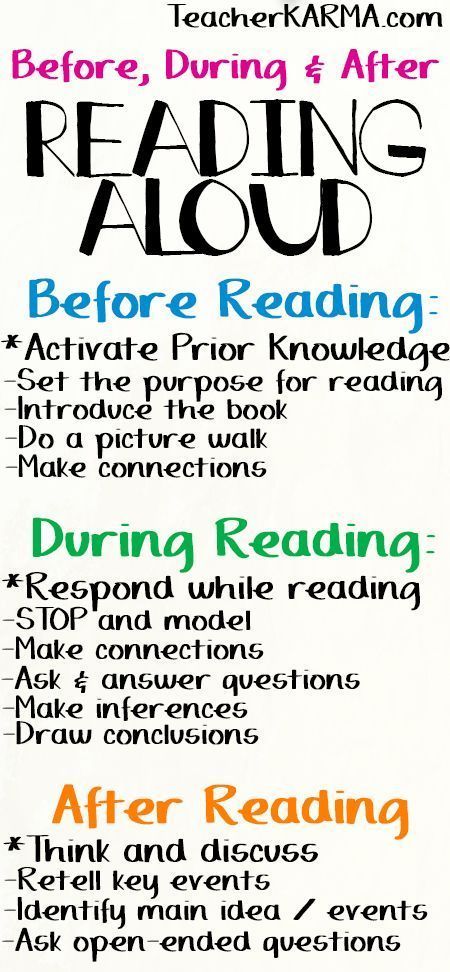

Before reading strategy

Before Reading: Tasks and Strategies | SEA

Stage One

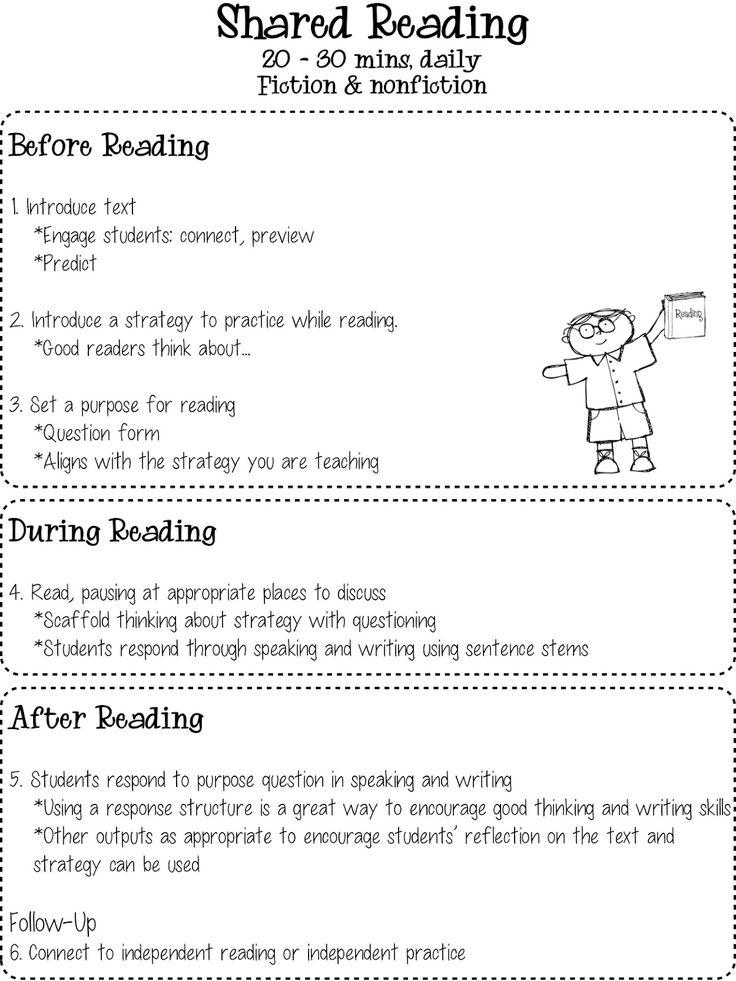

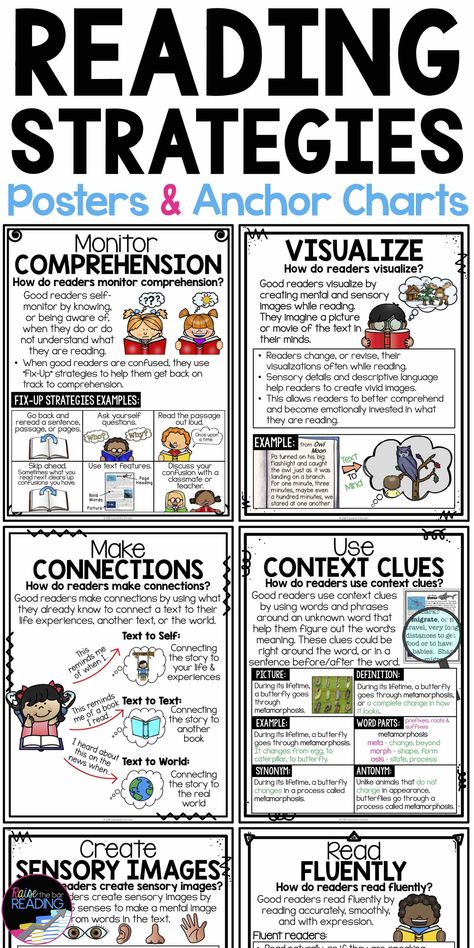

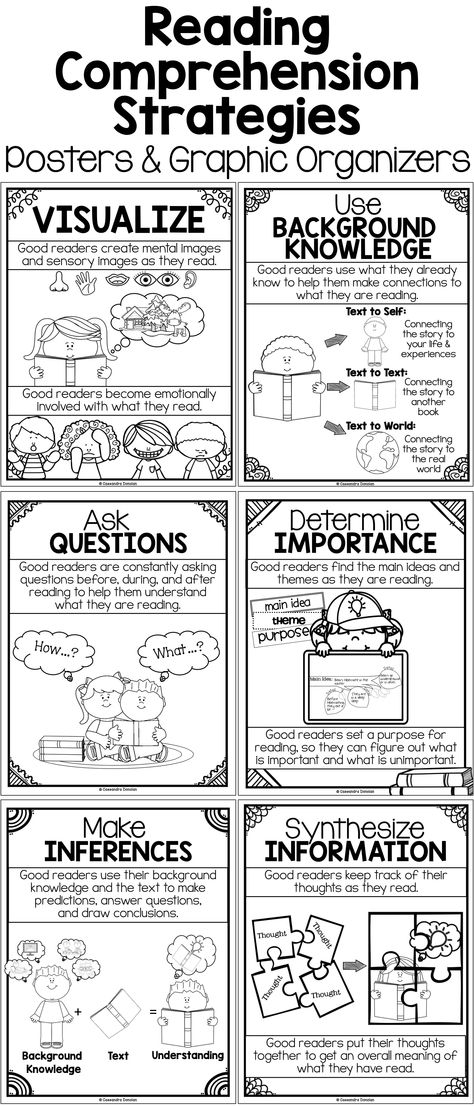

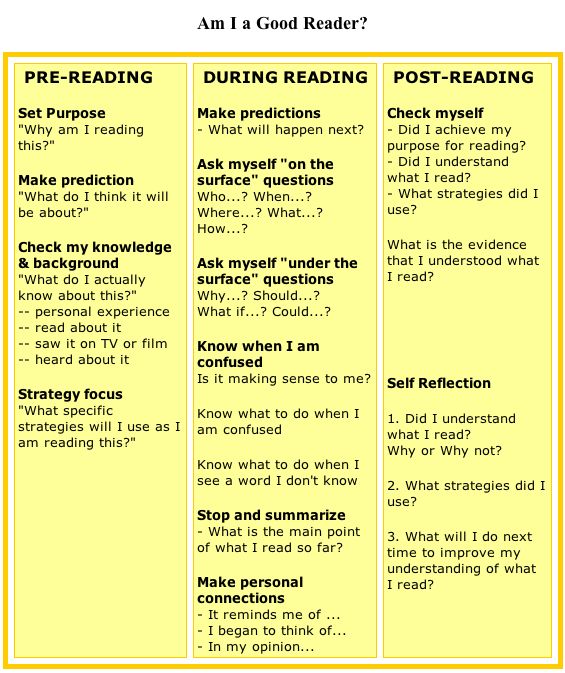

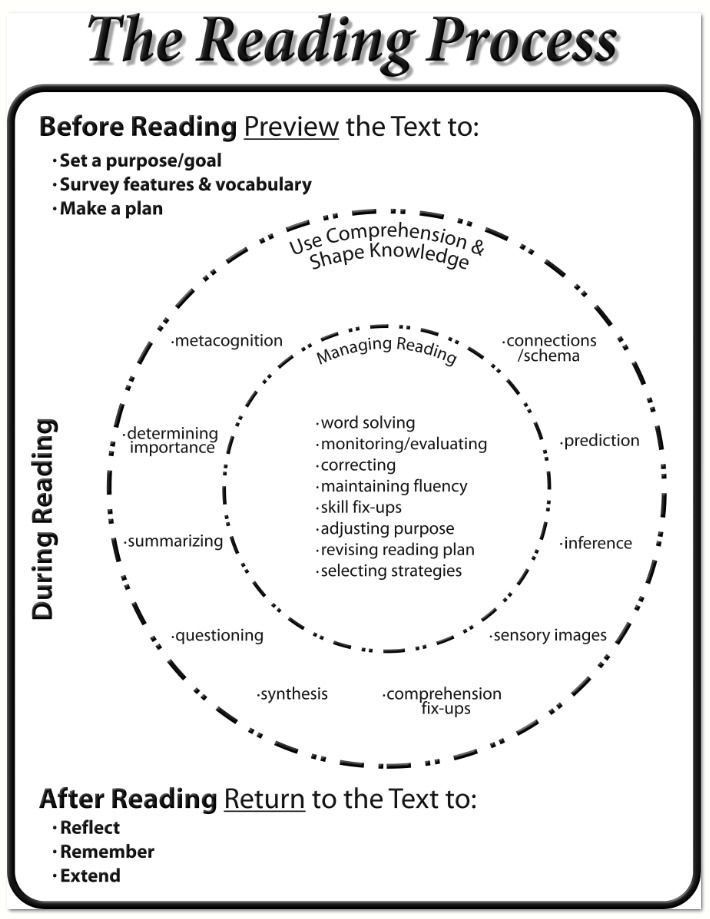

The reader's task prior to reading is to activate his or her prior knowledge of the topic, to prepare the mind to interact with the new information contained in the text. Schema is another term for the prior knowledge base each reader possesses about a topic. Schema is a network of concepts, experiences, and associations that students bring to their interactions with the printed page.

Rather than just "diving in cold" and reading word by word with eyes tending to glaze over, skilled readers, like skilled athletes, ready themselves for the task. As an athlete prepares to exercise by doing warm-up exercises, so does a reader "warm up" the mind. Each textbook reading experience does not have to be an arduous and frustrating exercise if students realize that they possess some knowledge already and that this text material will augment what they already know.

Tasks of the Before-Reading Stage

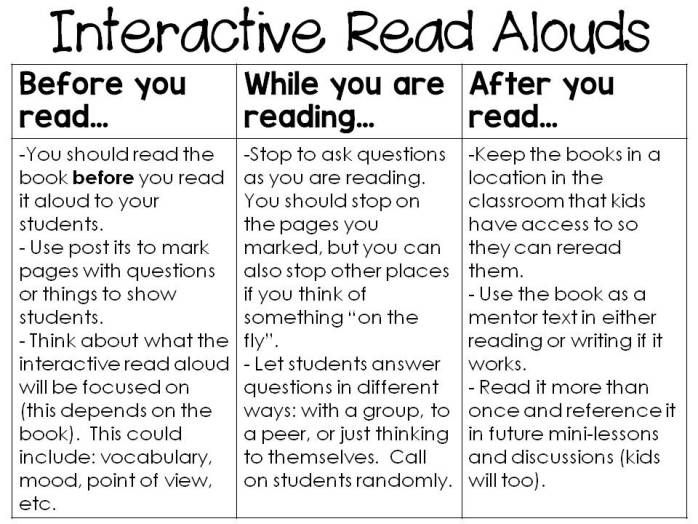

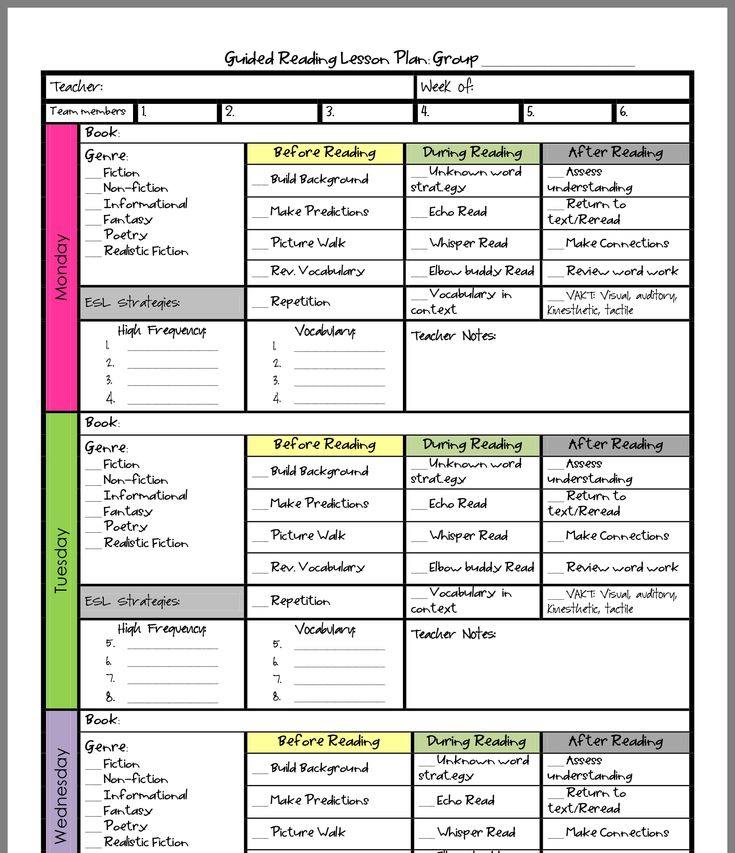

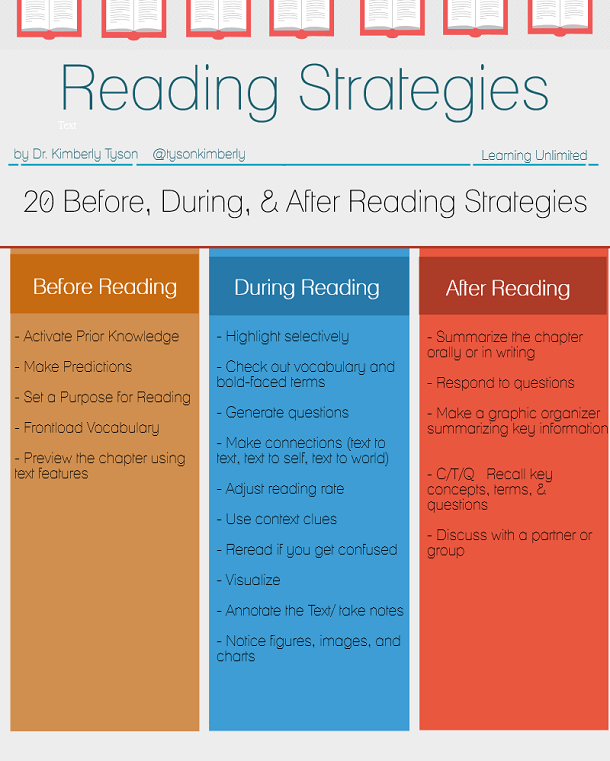

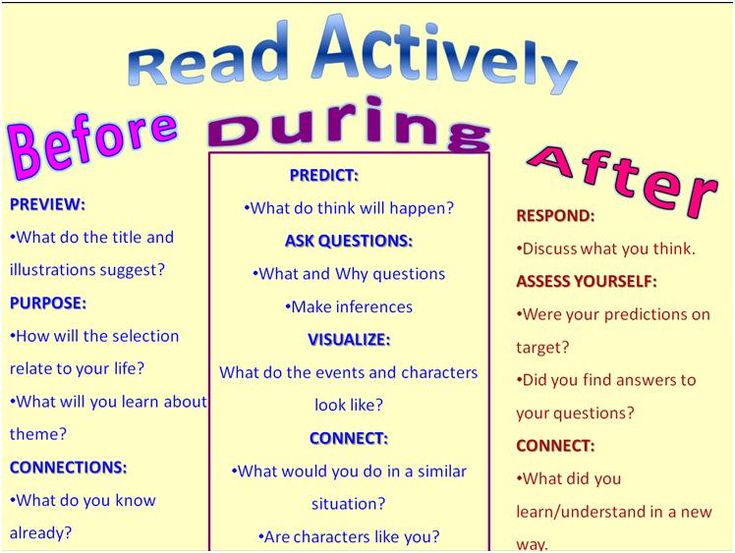

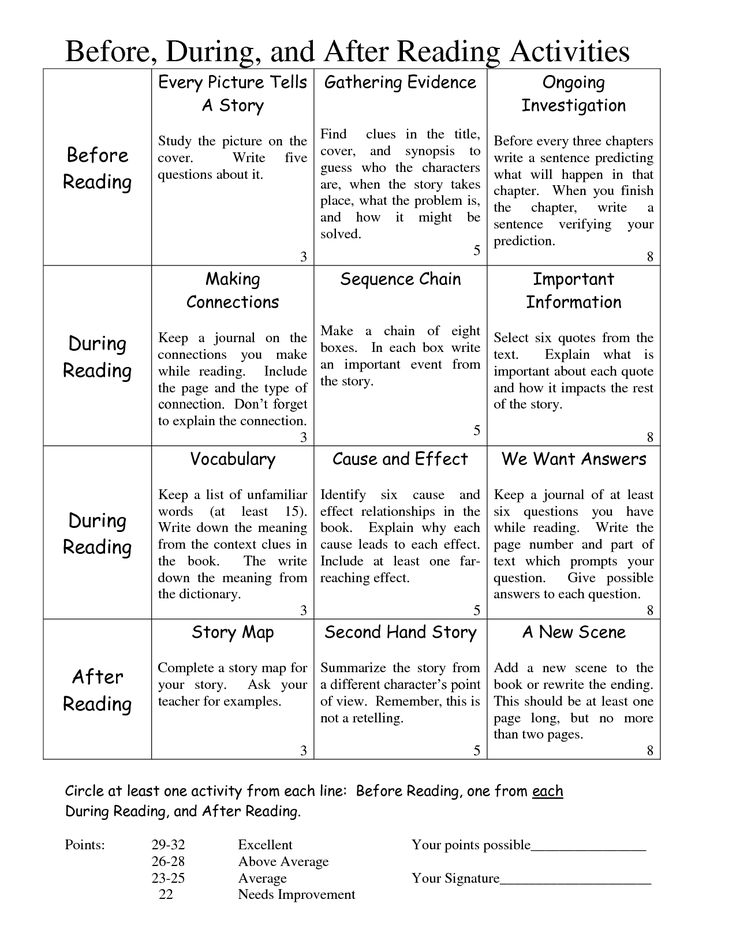

In the before-reading stage, the teacher can use tasks and follow strategies to motivate students to engage in the reading process. One way to motivate students is to help them to activate their prior knowledge of the topic (schema). In general, the teacher can help students create a focus for their reading efforts, to set a purpose for the reading.

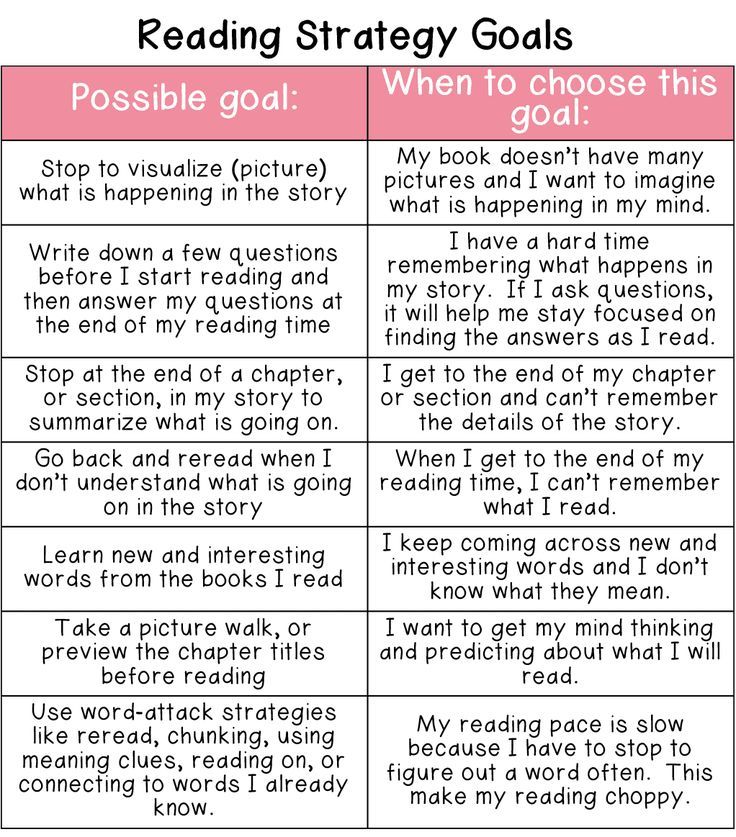

Strategies to Activate Prior Knowledge

The teacher can do much in the classroom to prepare students for their readings. Prior to class, the teacher can anticipate student needs by:

Previewing the chapter and determining which concepts are essential.

Reading over the material with an eye to student needs. How much foundation building will the students need to understand these concepts?

Asking "Where are the trouble spots in this chapter?"

Noting resources offered by the text, such as the glossary, list of objectives, margin notations, and end-of-chapter summaries and questions.

In-Class Strategies

In class the teacher can help to build a bridge between information which is "known" and information which is "new. " To build a bridge between known and new, the teacher can:

" To build a bridge between known and new, the teacher can:

Review what has been learned to date.

Ask "What do we already know?" For example, in a business text's chapter on global business, recall that the previous chapter dealt with "U.S. Business."

Ask questions to draw on students' life experiences: "Do you know any companies that operate worldwide?"

"What problems do you think an American company might have overseas?"

Use the table of contents of the text to put the new topic in context.

Link new material to concept maps or webs of material learned previously.

Reviewing known material brings to the surface the knowledge that the students already possess; it establishes a "platform" for the new information. Students get the sense that they bring something to the task.

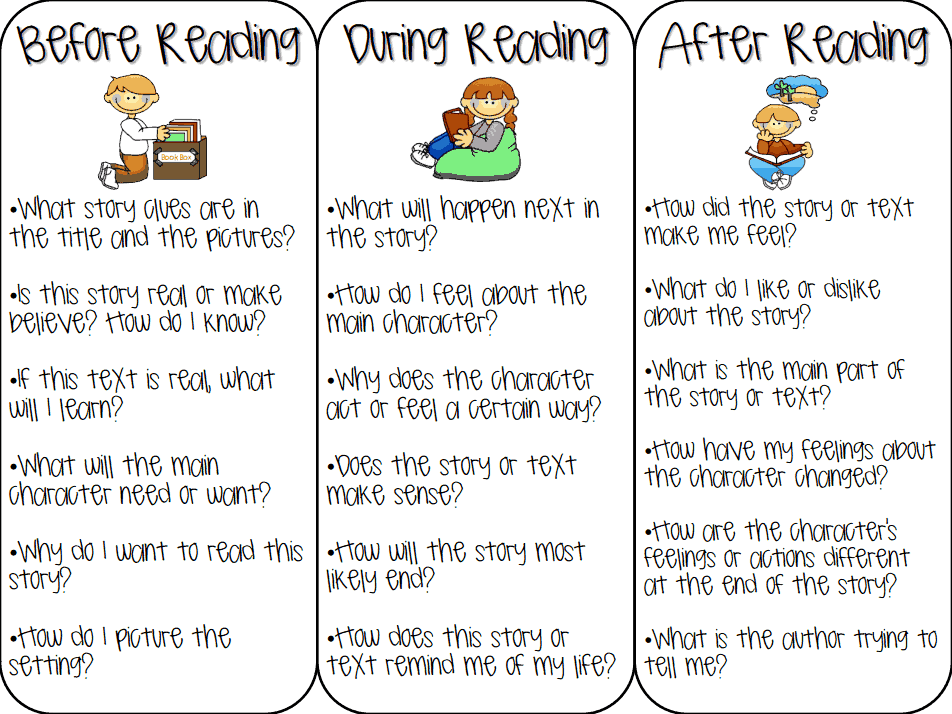

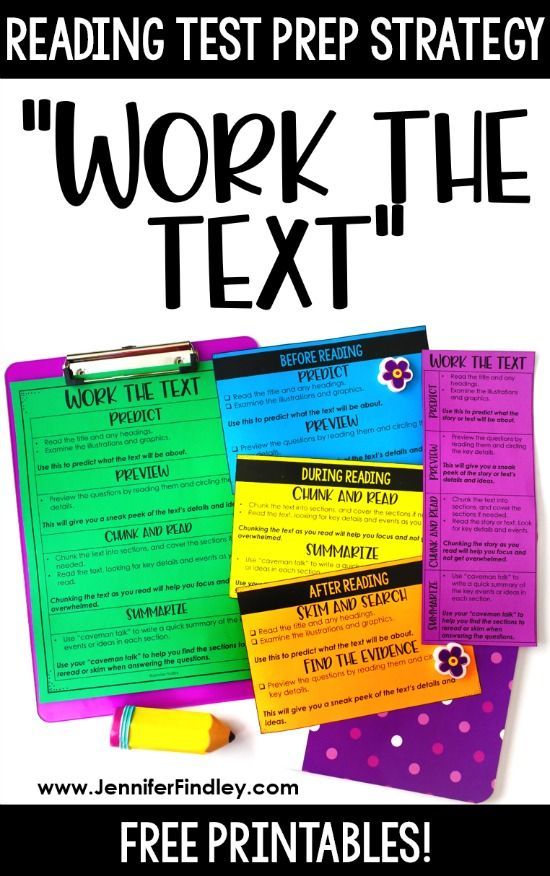

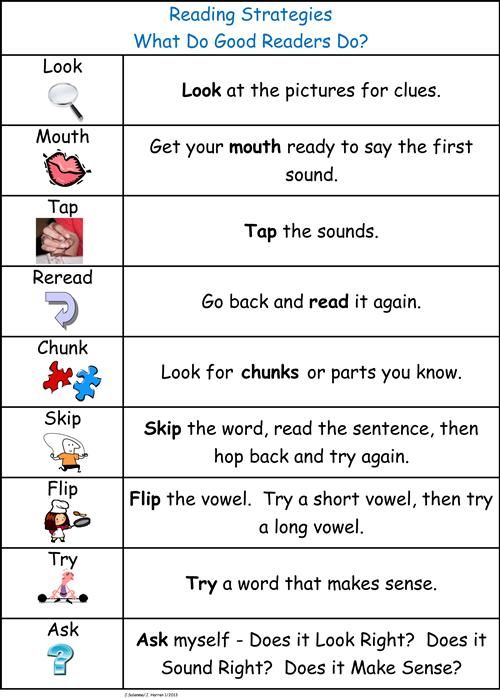

A second in-class strategy that the teacher can encourage students to employ is to look ahead

, to survey a chapter or other reading. Looking ahead is similar to looking at a road map before taking a trip; it prepares the mind. To look ahead…

Looking ahead is similar to looking at a road map before taking a trip; it prepares the mind. To look ahead…

Skim through the chapter or section. Look at subheadings, pictures, and graphic representations to get an idea of what is coming.

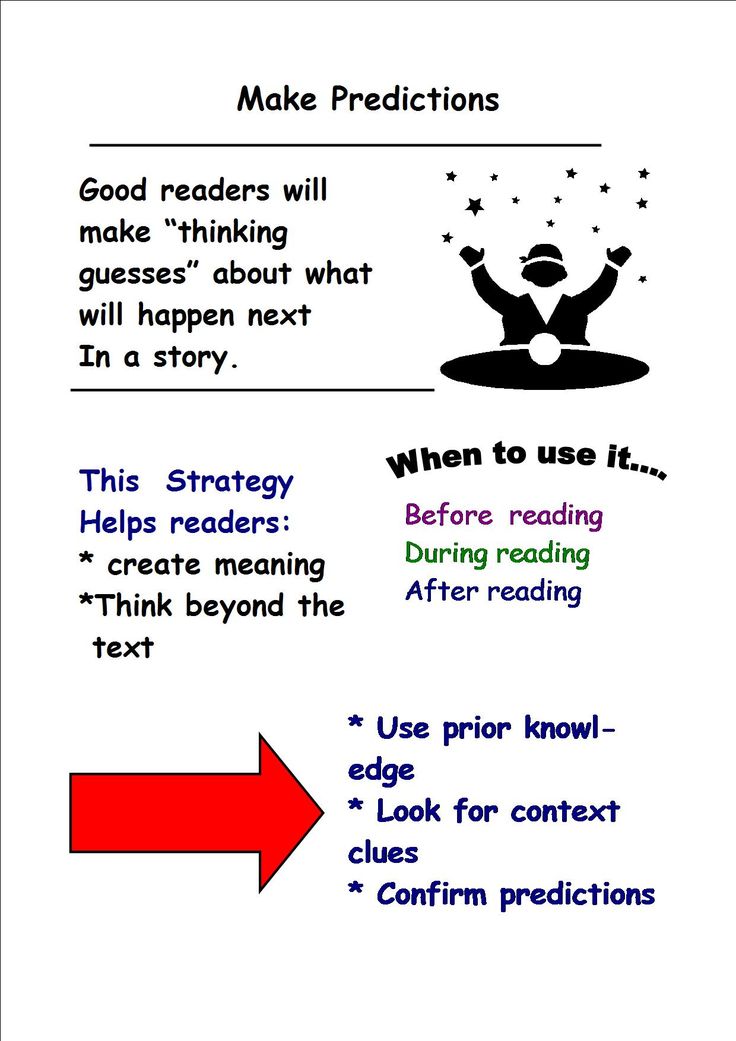

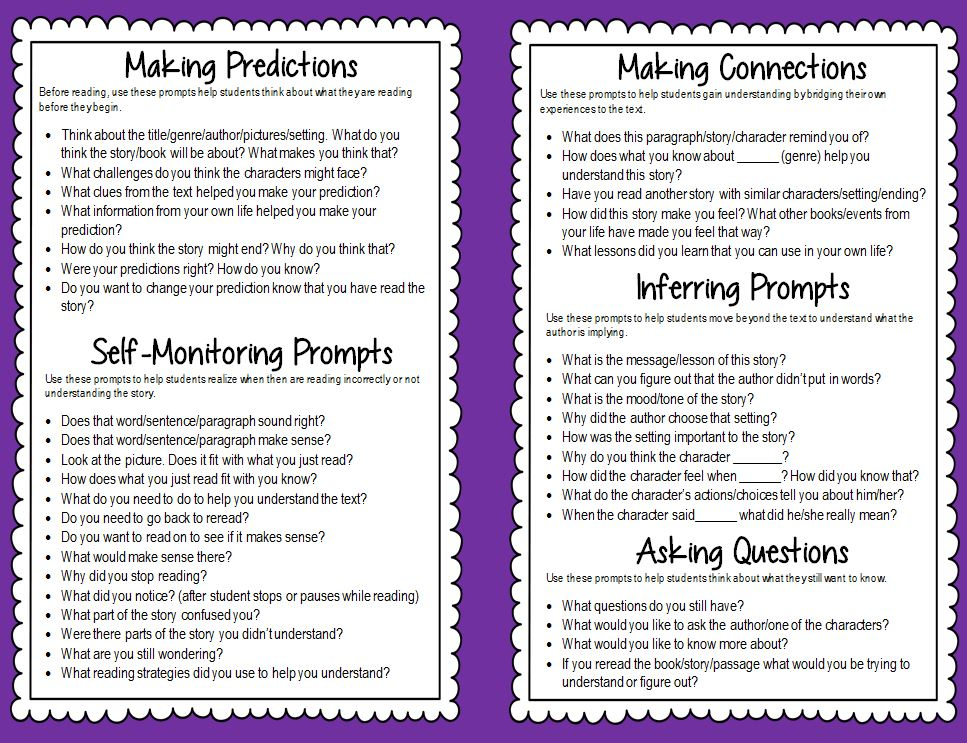

Anticipate. Encourage students to write down their predictions of the concepts they will be learning and, afterwards, to compare their predictions with what they actually encountered.

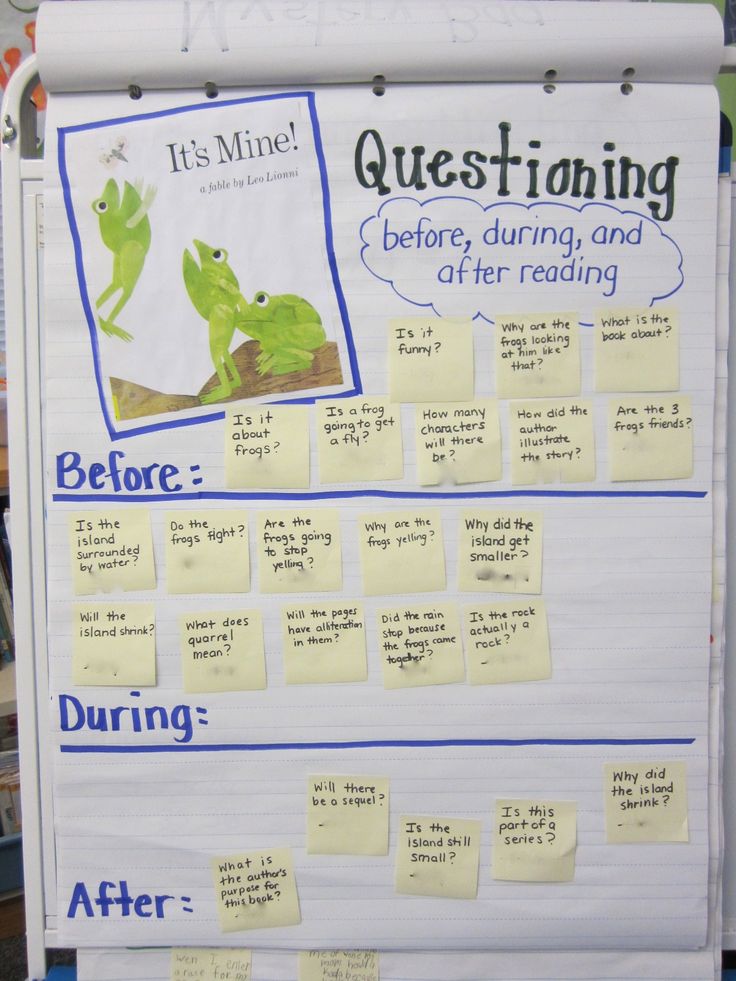

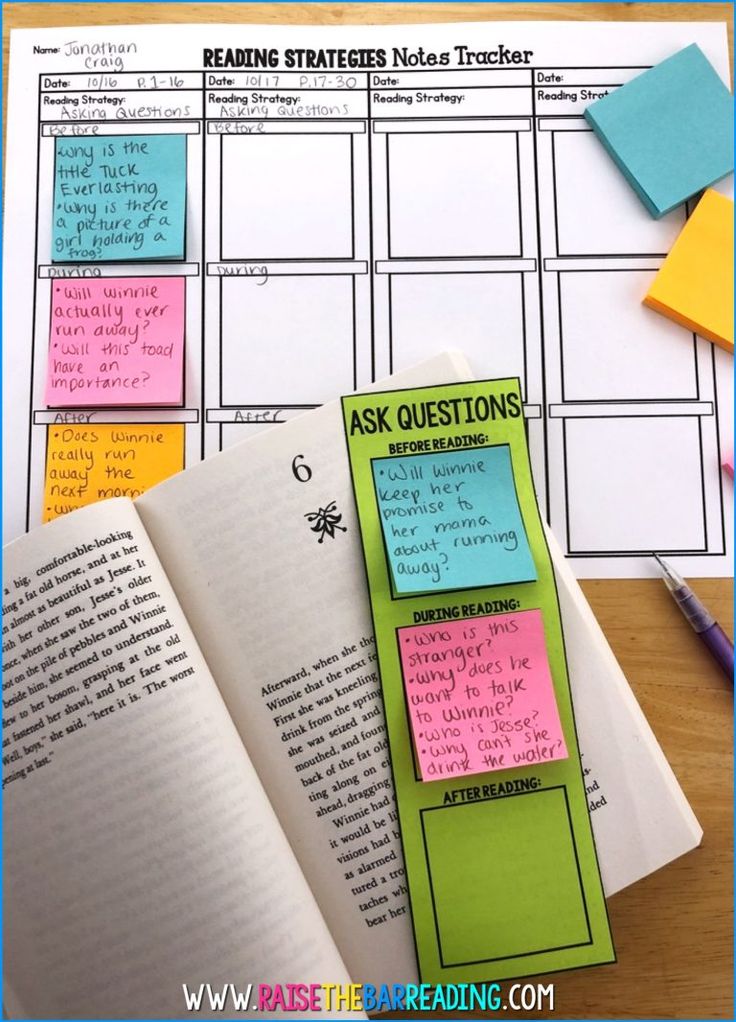

A third in-class strategy involves questioning:

What do we want to know from this reading?

Take the chapter title and subheadings and turn them into questions, to focus the mind and create a reading goal.

Forming questions or predictions about the upcoming reading helps to create a focus for the student during the reading, so the student doesn't just stare aimlessly at the words on a page. Questions make the reading more active and purposeful.

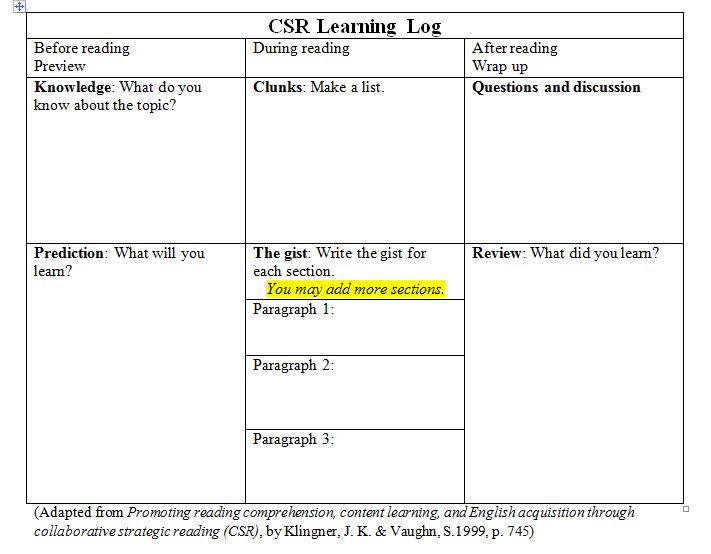

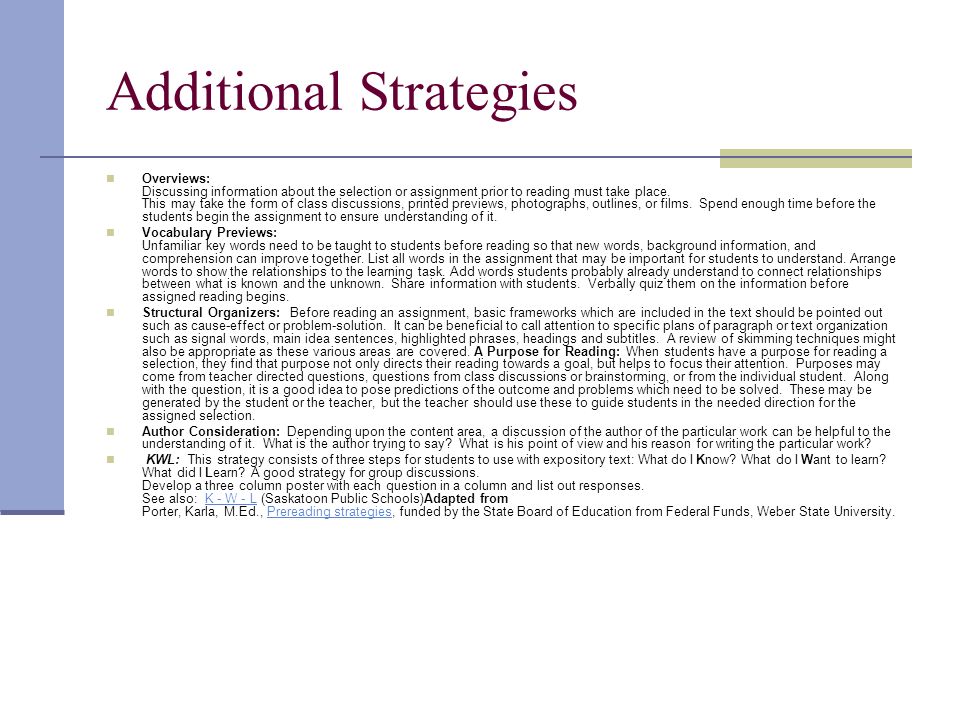

As a fourth strategy, students can benefit from the use of K-W-L Charts to log their interactions with a reading (Vacca & Vacca, 1996, pp. 211-217). A K-W-L Chart is a table on which students can record their prior knowledge and new learning from their reading experience. K-W-L stands for the following three questions:

211-217). A K-W-L Chart is a table on which students can record their prior knowledge and new learning from their reading experience. K-W-L stands for the following three questions:

K = What do I know already about this topic?

W = What do I want to know?

L = What did I learn from this reading?

The first two questions are completed in the before-reading stage. The third question is completed in the after-reading stage.

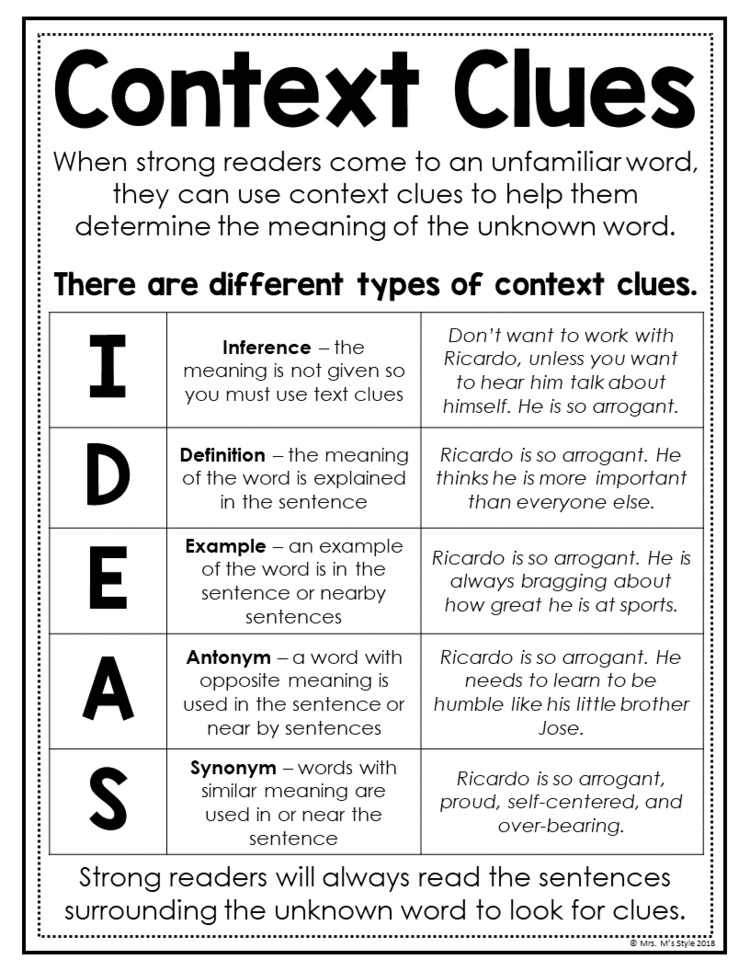

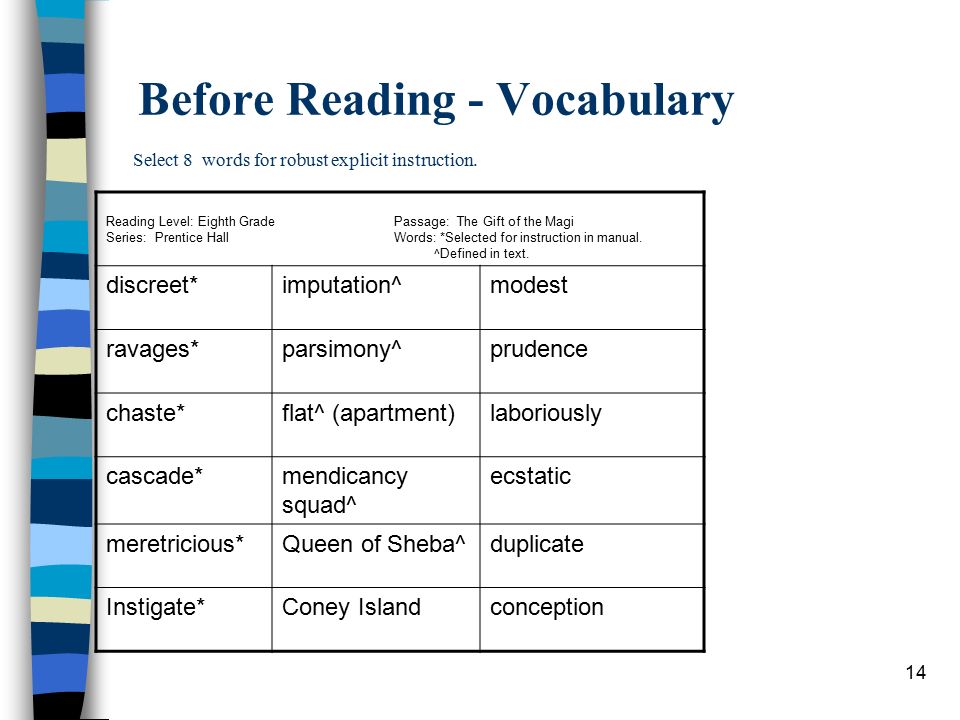

A fifth in-class strategy helps students to build vocabulary and new concepts:

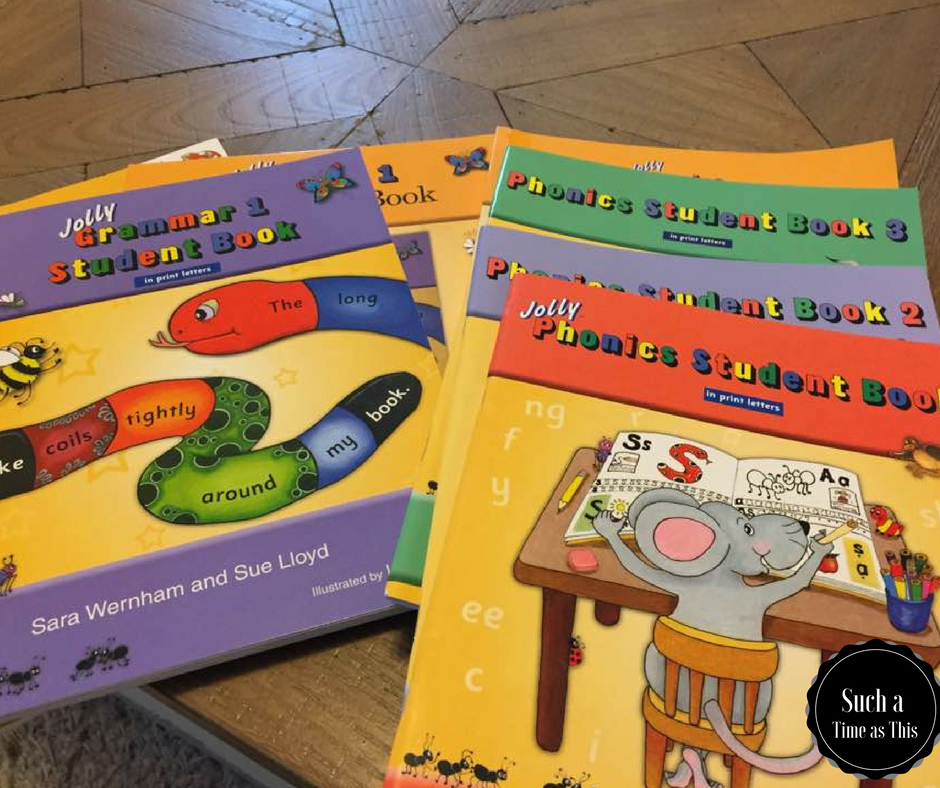

Prior to a reading assignment, introduce new concepts and vocabulary that the students will encounter in the reading.

For more details on vocabulary-building ideas, see the SEA Site module, Reading and Writing in Content Areas.

Conclusion

Students need overt instruction and practice in the before-reading tasks and strategies discussed above in order for those tasks and strategies to become part of their repertoire of study skills. It helps if the teacher can model the process and then encourage students to work in groups to practice. This "scaffolding" of strategy instruction helps students internalize the skills, so they will develop the ability to use them independently. Keep in mind that "to control the process, readers must understand the process" (Smith, 1995).

It helps if the teacher can model the process and then encourage students to work in groups to practice. This "scaffolding" of strategy instruction helps students internalize the skills, so they will develop the ability to use them independently. Keep in mind that "to control the process, readers must understand the process" (Smith, 1995).

Pre-Reading Strategies To Boost Kids’ Reading Comprehension

What Are Pre-Reading Strategies?

Pre-reading strategies are learning approaches designed to help give your child structure, guidance, and background knowledge before they begin exploring a new text.

These strategies target your child’s reading comprehension skills by giving them the tools they need to become active, successful readers.

By activating the knowledge your child already has about certain subjects, learning how to utilize context clues, and talking with you about the book, they’ll be on their way to reading and writing scholarly essays in no time!

Basic Pre-Reading Strategies

As the name suggests, pre-reading strategies are used before you begin reading a book with your child. There are a few main strategies you can use to help your child prepare to dive into any story. Let’s take a look!

There are a few main strategies you can use to help your child prepare to dive into any story. Let’s take a look!

Previewing

By this, we don’t mean Googling the movie-adaptation trailer (although that might be a fun way to compare and contrast the text later on!).

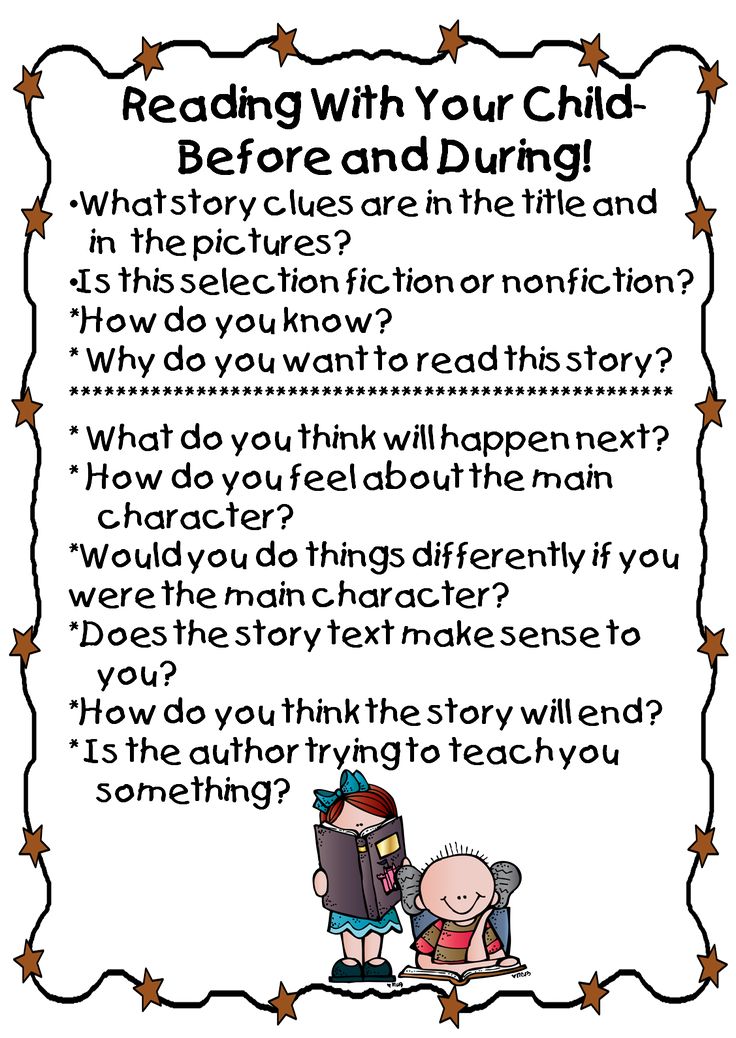

Previewing means letting your child gather clues — from the book’s title and cover illustrations, inside illustrations, and maybe the table of contents for older children — to try to figure out what might happen or what they might learn in a book they are about to hear or read.

Purpose

If you have time, it’s always great to put aside a moment for mindfulness before reading with your child. Talk with them about what reading goals they still want to achieve.

Do they still need help with longer words (pronunciation)? Do they want to work on their character voices (expression)? Getting their input will help you both come together to set a goal — or purpose — for your reading time.

Predictions

Using the resources available to your child, see if they can make predictions about what might happen in the story before they get a chance to read anything.

What information can they gather just using the title, cover, and illustrations? Then you both might continue predicting as the story unfolds.

8 Pre-Reading Activities To Try At Home

1) Speaking In Questions

This is a fun activity that helps your child become more insightful about the text they’re reading while letting them be silly, too! The goal here is for your child to investigate the things they want to know, might know, or aren’t sure about just by looking at the cover of the text.

We know you probably use the question-and-answer format quite a bit in your reading routine, so this offers your child a nice change of pace. Instead of you asking the questions, they get to ask, too!

These questions can be silly or straightforward. For example, if you’re reading Goldilocks and The Three Bears, you could start the question conversation by asking your child, “Why do you think her name is Goldilocks?”

Your child might ask back, “Why do these bears live in a house?” See how many questions you can come up with.

It’s OK if these questions are not answered right away. Most of them will probably be answered once you’ve finished reading the book! Any that go unaddressed can always be answered afterward.

2) K-W-L-H Chart

This pre-reading activity was invented and made famous by Donna Ogle back in the 1980s. The different letters in K-W-H-L charts represent different tasks for your child to complete with you.

The “K” column is reserved for things your child already knows about the subject of a book or its story. The key here is activating and then reflecting on their prior knowledge. For example, if they’re reading Charlotte’s Web, what do they already know about pigs and spiders?

The “W” category is for what your child wants to know about the story. What are they curious about?

The “L” (what they learned from the story) and “H” columns (how they can find out more ) are reserved for discussing after you’ve finished reading.

The last row, how they can find out more, is more important in nonfiction than fiction — although after reading Charlotte’s Web, you could find out more about spiders by seeking out a nonfiction book.

While this exercise is traditionally completed by writing their answers down on a chart, we think it’s more fun to get physical with it!

For example, you could make a book review video to share with family members! First, challenge yourselves to come up with at least six Ks and 6 Ws, three from each of you.

Next, make a video that begins by naming the book you are reading, followed by announcing the things you know and the things you want to know. When you are finished with the book, video what you learned and where you can go to learn more.

You can even create a special book-video library of your KWLH experiences!

3) Pre-Teach Vocabulary

If you know that the book you’ll be reading together will challenge your child’s current reading skills, consider teaching them a handful of the more challenging words ahead of your reading time.

We love a good old-fashioned game of (reverse) Charades for this pre-reading activity. To start, you might write out the word you want your child to learn on a large sheet of paper. Make sure to use bold, thick letters!

Make sure to use bold, thick letters!

Then, try and act out the definition of the word for your child. Based on your impeccable acting skills, they can guess the definition of this new word!

4) Pre-Teach Themes

Many children’s books set out to teach children more than new words. They usually have moral lessons embedded in their pages as well.

For example, themes might include things like the power of friendship in Charlotte’s Web or courage in a book about Martin Luther King, Jr.

To get your child’s mind focused on the theme of the book, you could prompt them by discussing the same moral lesson. See what their initial opinion is about it. Do they have a strong sense of it already, or do they want to learn more?

Reading the book can either confirm or change their opinion. And then you have something to talk about when you’re finished reading!

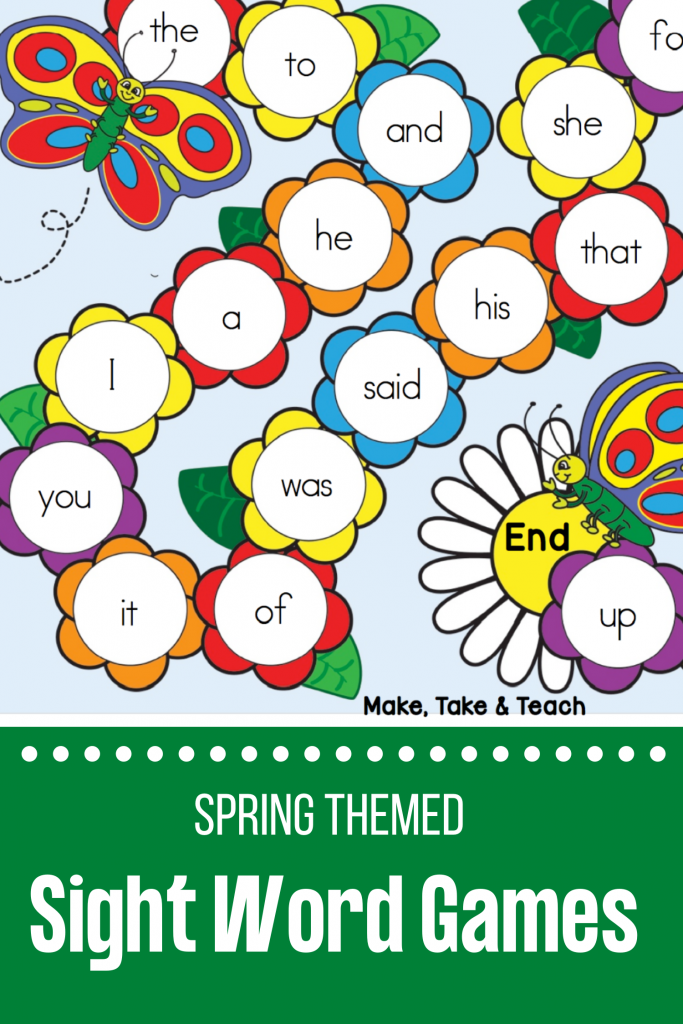

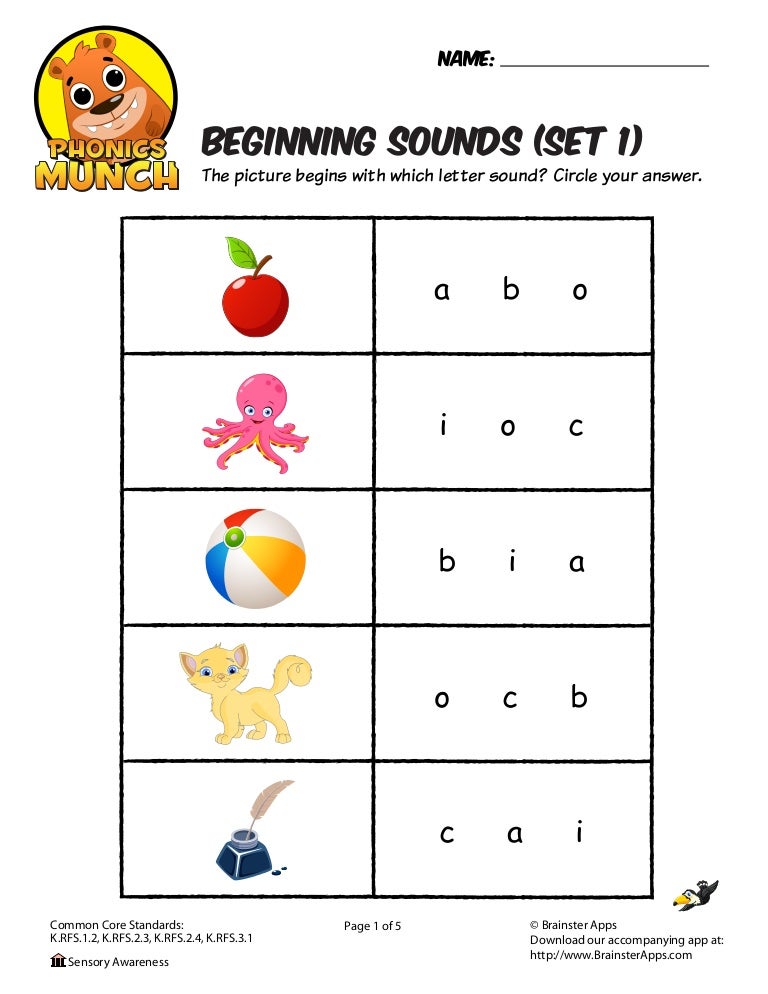

5) Word Bingo

This game is another great option for getting your child’s mind prepped to learn vocabulary or to brush up on sight words they need a little extra help with.

If you’d like to try this pre-reading activity, create a Bingo sheet for each of you using words from the text before your reading time. Every time you or your child hears or sees a word that matches one on your sheet, place a sticker on it.

The first one to yell out, “Bingo!” wins.

6) Sentence Obstacle Course

This pre-reading activity is great for encouraging your child’s comprehension and sentence formulation. The stronger grasp they have on learning how to construct words into sentences, the faster they’ll adjust to the flow and structure of stories.

For this exercise, we suggest writing down several words on individual sheets of paper. Make sure you include all the components of a typical sentence — nouns, adjectives, objects, and verbs. Only include one word per piece of paper.

Next, scatter the words on the ground. We suggest adopting the “the floor is lava” rule! Your child will need to hop to different words to combine them into a sentence.

For example, they could “write”: The (jump) cat (jump) is (jump) red. If you want them to work on their punctuation, you could include that, too!

7) Anticipation Vs. Reality

This method will help take some of those preliminary questions you and your child came up with and figure out what happens in the end!

For this game, you can play while reading or beforehand. If you want to make guesses about what will happen in the story before reading, make sure you jot them down on a piece of paper to keep track of who made the most correct guesses.

If you want to play during the story, you can ask questions to prompt your child before turning to a new page. For every correct guess they make about what happens next in the story, they earn a tally point.

The goal is for your child to get as many points as they can!

8) Origin Story

For children who seem to show an interest in history, this might be the perfect pre-reading activity.

There are so many things you can learn from books just from discovering a little bit about their backgrounds. For example, tons of writers pull from their real lives for inspiration to write their books.

For example, tons of writers pull from their real lives for inspiration to write their books.

Finding out about an author’s life in the author’s blurb and maybe even searching out more information either before or after reading can be a learning adventure all on its own!

To do this activity, work with your child to see what you can find out about the story you’ll be reading (without spoiling the ending!). What you can learn based on the author, where they are from, where the story is based, its historical period, and its subject matter?

This helps your child build additional knowledge and gets them prepared for the story ahead!

Pre-Reading Strategies For The Win

Pre-reading strategies are all about getting your child prepared for the reading journeys to come. We hope these eight ideas will help you both have interesting, exciting conversations about books and where they can take you!

And if you ever need a little helping hand in the meantime, check out our personalized Learn & Grow App for reading exercises and adventures that will keep your child entertained, energized, and learning!

Author

Read the book “Real strategy.

How to plan only what can be realized” online in full📖 — Jacques Pale — MyBook.

How to plan only what can be realized” online in full📖 — Jacques Pale — MyBook. All rights reserved. This e-book is intended solely for private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes. The e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, including text, images and others, may not be copied or used in any other way without the permission of the copyright holder. In particular, such use is prohibited, as a result of which an electronic book, its part, fragment or element becomes available to a limited or indefinite circle of persons, including via the Internet, regardless of whether access is provided for a fee or free of charge.

Copying, reproduction and other use of an e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, beyond private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes, without the consent of the copyright holder is illegal and entails criminal, administrative and civil liability.

Foreword

Most of the strategies companies create never materialize. The famous management theorist Henry Mintzberg often talks about this in his speeches.

A few years ago, during a discussion in the Netherlands, he asked the question: who is usually blamed for the failure of the strategy? And he himself gave a simple answer: the main blow is taken by the performers. Leaders tend to think, “We come up with brilliant strategies here at headquarters, and these idiots — the rest of the organization — just don’t have the brains to implement it.” Well, if you are just one of these "brainless idiots," continues Mintzberg, I can offer a comprehensive answer. Just tell management, “Since we are such idiots and you are smart, why don’t you come up with a strategy that idiots like us can still implement?”

The argument is strong. But is it fair? Not quite, and Mintzberg is the first to admit it. Almost all missteps in implementation, he says, are due to the fact that the strategy is written separately and implemented separately. In turn, this gap arises from the mistaken belief that strategy can be conceived in one place - corporate headquarters, and implemented in another - in the workplace. The subject of this book is precisely this key point: the relationship between strategy and its implementation. Or, to use the more radical expression of Jacques Peil, the equality of strategy and implementation. Here are four points that particularly struck me that make this book a must-read.

The subject of this book is precisely this key point: the relationship between strategy and its implementation. Or, to use the more radical expression of Jacques Peil, the equality of strategy and implementation. Here are four points that particularly struck me that make this book a must-read.

1. Strategy is inseparable from implementation

A non-embodied strategy is the same as the absence of a strategy. That is why it is necessary to think about the implementation of the strategy from the very beginning of its development. Strategy and implementation are inextricably linked, and everything that follows from this is detailed in the book within a system of four accelerators, each of which consists of four blocks. Perhaps this sounds too schematic. But the time of improvisation and drift in the implementation of the strategy is long gone. The embodiment of strategy has become a craft on which our victories and defeats also depend.

2. The whole truth about innovation

Today, repairs have to be done without closing the shop. Every entrepreneur and manager understands this problem. We need to devote time to the business as it is today, otherwise we will not be able to please customers and make money here and now. And at the same time, it is necessary to invest in making our business the way we want it to be tomorrow and in the future. The word "innovation" can be understood in different ways. This book distinguishes between three types of change: improvement (perfection), modernization and innovation. Each of them requires a special approach. It's not easy, but it's a reality that every experienced manager knows.

Every entrepreneur and manager understands this problem. We need to devote time to the business as it is today, otherwise we will not be able to please customers and make money here and now. And at the same time, it is necessary to invest in making our business the way we want it to be tomorrow and in the future. The word "innovation" can be understood in different ways. This book distinguishes between three types of change: improvement (perfection), modernization and innovation. Each of them requires a special approach. It's not easy, but it's a reality that every experienced manager knows.

3. People do the work

Questions “why?”, “what?” And How?" are important, Pale argues, but the most important question is "Who will implement the strategy?" In the end, the work is done by people, and everything is decided by their qualities and degree of involvement. All this is fine, but deep conclusions should be drawn from this. For example, people who have to implement a strategy must psychologically “sign up” to it. In other words, they must be truly committed to the strategy, initiatives, and goals. The book details how to achieve true engagement.

In other words, they must be truly committed to the strategy, initiatives, and goals. The book details how to achieve true engagement.

4. Theory and practice

It's good when a writer is well-read in his field. Some authors of management books try to present their ideas as something new just because they are not familiar with the classics. There is no need to be afraid of this here: Jacques Pale is well versed in his field. At the same time, he is acutely aware of the need to be practical. Jacques and his colleagues are practitioners who feel like fish in water in the realities of business consulting, so they managed to fill the book with useful examples and healthy realism.

I love evidence-based work. I will add just one. This book is a treasure trove of sound guidance and advice. But you will only feel its true value when you try to apply them in your organization. You will see how these great ideas are brought to life, and the words from these pages turn into a job well done and great results. Happy reading and learning!

Happy reading and learning!

Ben Tiggelaar,

Social Psychologist, Writer, Lecturer and Consultant

1

Introduction

Efficiency, agility and speed are the keys to strategy implementation

Rise of Netflix / IBM Watson Graduated / S-Curve Dead / Philips Refusal to Buy Apple

1.1. Accelerating innovation is a burning challenge

We need to accelerate the improvement, modernization and innovation of our business model. This is the key management challenge of our time. Organizations found themselves between a rock and a hard place. Failing strategies have become the talk of the town, but in this hectic age, companies have no choice but to constantly improve, modernize, and completely renew their business models. The most needed for success turned out to be the very skill that organizations are sorely lacking. That is why managers, specialists and entrepreneurs do not sleep at night. And they do it right. As one CEO recently told me, “We all need to learn this. Immediately. It is simply our responsibility to society. Without it, we're finished." That is why I wrote this book. Of course, there are more serious problems in the world. Just watch the news. Be that as it may, I am convinced that learning how to implement the strategy more effectively is an important task. We spend most of our lives at work, and it is best to work on something meaningful. People want work to have meaning and purpose. Today, organizations consciously choose which societal values they want to reflect. We are outgrowing our long-standing obsession with shareholder value. Now social responsibility, cultural diversity, regional and national development are valued. These aspirations are among our main strategic goals. Effective strategy execution creates value and helps to formulate meaningful goals.

That is why managers, specialists and entrepreneurs do not sleep at night. And they do it right. As one CEO recently told me, “We all need to learn this. Immediately. It is simply our responsibility to society. Without it, we're finished." That is why I wrote this book. Of course, there are more serious problems in the world. Just watch the news. Be that as it may, I am convinced that learning how to implement the strategy more effectively is an important task. We spend most of our lives at work, and it is best to work on something meaningful. People want work to have meaning and purpose. Today, organizations consciously choose which societal values they want to reflect. We are outgrowing our long-standing obsession with shareholder value. Now social responsibility, cultural diversity, regional and national development are valued. These aspirations are among our main strategic goals. Effective strategy execution creates value and helps to formulate meaningful goals.

1.2. Implementing strategies is the bane of organizations

Research consistently shows that organizations are bad at implementing strategies. That's not news. We have known about this for decades, and the data collected is staggering. Estimates of the failure rate range from 60% to 90%. Of course, this figure depends on what we agree to consider a failure (more on this in Chapter 9). And even if we are extremely critical of the figures given in most studies, the percentage of failed attempts to implement the strategy will be at least 50%1. The examples are well-known: large-scale government IT projects seem to get stuck in a quagmire, private mergers do not lead to the expected synergies, major restructurings spiral out of control, and cultural change programs seem to disappear into thin air. Organizations are full of good intentions, but they often pave the proverbial road to hell. This is where the potential competitive advantage lies, but it's not just that. Any organization in any case must be able to successfully implement strategies.

Any organization in any case must be able to successfully implement strategies.

1.3. The New Normal

The world will never be the same as it was before the financial crisis of 2008. Too much has changed – economic, social, cultural and technological. Globalization and changing consumer behavior are also important factors. All of this has led to a breathtaking increase in the demands placed on our business models. Life is changing faster and faster. According to Jan Rothmans, Professor of the Theory of Transition to Sustainable Development, we are no longer experiencing an era of change, but a change of eras2. With your permission, I will list a few of the phenomena described in my previous book, The New Normal (Het Nieuwe Normaal)3.

Business models are melting before our eyes. Business models are under enormous pressure in many industries, including tourism, real estate and the financial sector. These industries are sometimes referred to as glacial industries: due to the current changes in the global business climate, they are melting like polar ice. The same fate awaits many other industries, it is only a matter of time. Research shows that disruptive digital innovation is affecting all sectors and more business models can be expected to melt in the coming years4.

The same fate awaits many other industries, it is only a matter of time. Research shows that disruptive digital innovation is affecting all sectors and more business models can be expected to melt in the coming years4.

Another glacial industry is traditional media, with profits shrinking by 10% a year in some segments. At the Cannes Advertising Festival, the director of Netflix touched on this issue in his opening remarks. He asked how long advertising time buyers would attend this festival and decide on behalf of the viewer what to watch and when. Agree, it is strange that nightly talk shows go on the air when most of the viewers are already asleep. We spend a lot of time watching TV, but this is one of the few products that does not give you a choice of when and what to consume. It's no wonder Netflix's rise has been so rapid. For example, in the Netherlands, this service attracted 600,000 subscribers in the first six months. This shows that the struggle waged by traditional television is hopeless. In the United States, 75% of late night shows are not viewed live but on demand. But even Netflix is already facing the need to change further.

In the United States, 75% of late night shows are not viewed live but on demand. But even Netflix is already facing the need to change further.

Industries converge. An innovation model that links government, education, and business in a triple helix holds just as much opportunity as either of these sectors alone. Participants in this spiral understand the value of cooperation and promote economic growth and regional development, increasingly taking on challenges together. An example of such a successful collaboration is Brainport Eindhoven. It is an alliance between the Dutch government, scientific institutions and companies such as ASML (semiconductor manufacturer) and Philips Medical. Another example is Yes! Delft, they offer start-up programs for young high-tech firms operating close to the world-class research centers at Delft University of Technology6. In the US, tech companies work side by side with institutions of higher learning in Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, Silicon Valley, MIT, and the like.

State and semi-state institutions are no exception. Senior managers know that state and semi-state institutions are just as helpless in the face of the new normal as are private enterprises. Under increasing pressure from social media and politics, citizens are demanding more transparency, lower prices, better service, and more efficiency. Many state and semi-state organizations are not ready to provide all this. It is especially difficult to satisfy the requirement of transparency. Let us recall at least the scandals that have shaken the government of the Netherlands in recent years. The Department of Defense was forced to compensate employees who had been exposed to the highly toxic hexavalent chromium for years; housing corporation Vestia almost collapsed due to the fraud of several senior managers, and the Central Works Council of the National Police of the Netherlands was implicated in corruption.

The rapid expansion of e-health services shows that governments, organizations and citizens cannot keep up with the adoption of new technologies. Watson, IBM's supercomputer, has already completed his PhD and will soon be able to replace the medical worker.

Watson, IBM's supercomputer, has already completed his PhD and will soon be able to replace the medical worker.

The new normal is for a long time. According to VINT, a Netherlands-based institute for new technologies run by IT firm Sogeti, in 2033 the average business life expectancy will be just five years7. Life expectancy of Fortune 500 companies at 1950 was 75 years, and in 2001 it was predicted that by 2012 it would collapse to 15 years; this shows the "shift index" from Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan's Creative Destruction8. The same is true for other indicators. The rating agency Standard & Poor's reports that in 1958 the average life expectancy of enterprises was 61 years, in 1980 it was 25 years, and in 2011 it was 18 years9. These figures suggest that 75% of the 2014 S&P 500 businesses will be gone by 2027.10 The frequency of industry market leaders has more than doubled since 2010. Loyalty is a thing of the past, because now customers make a new decision every time who best meets their needs. The competition has increased by 100% and no one's position in the market can be taken for granted anymore. In short, the new normal is with us for the long haul. This is a reality supported by stubborn facts.

The competition has increased by 100% and no one's position in the market can be taken for granted anymore. In short, the new normal is with us for the long haul. This is a reality supported by stubborn facts.

The facts showing how the new normal differs so much from the "old" one are summarized in Fig. 1. The trend is obvious: continuity has ceased to be a given, and the main reason for this is, of course, digitalization.

For the first decade of the XXI century. organizations have changed more than in the entire second half of the 20th century. In recent years, they have seen everything from process optimization to radical innovation, from outsourcing to sourcing optimization, from joint ventures to full-blown mergers and acquisitions—plus a continuous stream of change programs. “The last five years have changed more than the previous fifty years,” admitted one executive I spoke with while preparing the materials for this book. And we can already confidently say that in the future, organizations will have a lot worse. The digitalization of society will inevitably continue, and the pressure to keep up with disruptive innovation will continue.

The digitalization of society will inevitably continue, and the pressure to keep up with disruptive innovation will continue.

1.4. Digitalization is the engine of innovation

In the 20th century. organizations achieved dominance through customer loyalty and economies of scale. At first, large-scale production (General Motors) brought success, later - control over supply chains (Walmart) and information (Amazon). And in the XXI century. everything is decided by the customers. Before each purchase, they read consumer reviews and change their minds every now and then. Winning them and maintaining an edge over competitors is possible only with the help of a strategy built on knowing the client and interacting with him.

James McQuivey of Forrester Research called the companies that know how to play this new competitive game "subversives." The best of disruptive innovations have two characteristics: they satisfy a basic need understood by the end user and penetrate the physical world of manufacturing plants and supply chains, the Internet of Things. The key challenge is to find better ways to meet basic and even latent customer needs11.

The key challenge is to find better ways to meet basic and even latent customer needs11.

20 years ago, disruptive innovations took years and required huge investments. Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen wrote about this in his book The Innovator's Dilemma. But the digital revolution has changed everything. Today, it is possible to radically transform any product or service much faster and cheaper. Today's disruptive innovators have a major impact on every aspect of business operations: data management, pricing, labor and capital management. Soon all industries will feel their impact, even those that have not yet undergone digitalization13. James McQuivey estimates that modern tools and platforms have increased the number of people able to bring innovative ideas to market by a factor of 10. And this is still a conservative estimate. The average cost of developing and testing these ideas is only 10% of yesterday's price tag. In total, our innovative capabilities have grown 100 times. But it also means that any business is now dealing with a hundredfold increase in competition.

But it also means that any business is now dealing with a hundredfold increase in competition.

Disruptive digital innovation increases the pace of competition and enables a previously unimaginable number of ideas to come to fruition. For old-fashioned organizations, their cumulative effect is devastating.

Digital innovation changes everything. Looking at Airbnb's growth figures, it's easy to see that the classic S-curve of the company's life cycle has become a hoary antiquity. It was replaced by graphics that are more reminiscent of the Empire State Building. Let's face it: the S-curve is dead! Everything is accelerating. New business models are emerging at a frenetic pace, and old ones are just as rapidly disappearing. No one can predict the future, but judging by this trend, the acceleration has just begun. The longer you wait before entering the race, the more difficult it will be to do so, as competition is one of the key factors. In 2011, innovator, entrepreneur, and investor Marc Andressen spoke eloquently about this in The Wall Street Journal article “Why Software Is Eating the World”14. If you make a list of organizations that did not exist 12 years ago, and today they either represent large new markets or have conquered a large share of an existing market, then the names will be painfully familiar: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Uber, Airbnb, Snapchat , Instagram, Fitbit, Spotify, Dropbox, WhatsApp and Quora15.

If you make a list of organizations that did not exist 12 years ago, and today they either represent large new markets or have conquered a large share of an existing market, then the names will be painfully familiar: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Uber, Airbnb, Snapchat , Instagram, Fitbit, Spotify, Dropbox, WhatsApp and Quora15.

Executives, managers and professionals grapple with the dilemmas posed by digitalisation.

Read online “How to implement a development strategy. Part 1. Roadmap for the implementation of the strategy”, Alexey Murzinov – LitRes

© Murzinov A.V., text, illustrations, 2019

© ITRK Publishing House, edition, design, 2019

Introduction (preliminary remarks)

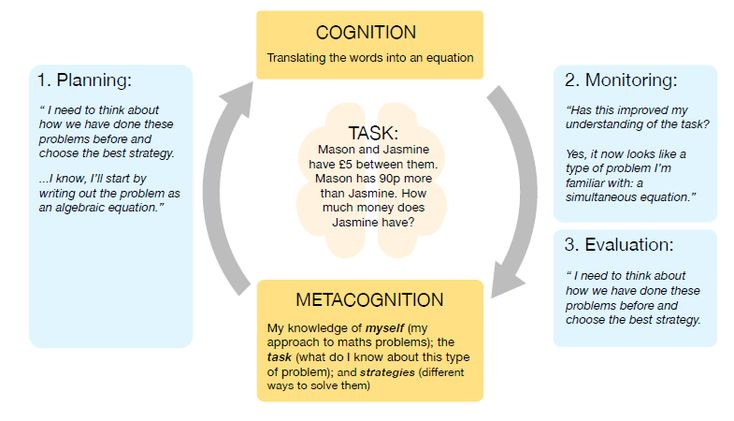

Strategic Management Process usually divided into three stages: strategic analysis, strategy selection and its implementation. Each of these stages is important and necessary and determines the final effectiveness of management. However, practice and academic activity concentrated mainly on the first two stages. It was assumed that the implementation of the strategy requires executive discipline and does not need special attention.

It was assumed that the implementation of the strategy requires executive discipline and does not need special attention.

However, the situation has begun to change in recent decades. There comes an understanding that the poor execution of the strategy nullifies all previous efforts. Indeed, even the most technically advanced strategic plan will not achieve its goals if it is not implemented. Many organizations spend time, money, and considerable effort developing a strategic plan, considering the means and circumstances under which it should be implemented, however, the result is not achieved. Changes in the organization do not occur in the process of planning, but in the process of implementing prepared plans. An ideal plan that never leaves the paper is worth no more than the paper on which it is printed.

According to Paul Niven [1] , the world's strategic management gurus have different opinions on many aspects, but agree on one thing: "executing a strategy is more important and more valuable than formulating a strategy" [1]. Implementation is often defined as the “Achilles heel” of the strategic management process [2]. It is one thing to develop a strategy that seems to be winning, but quite another thing to successfully implement it. “Companies that achieve strategy implementation will succeed” [1]. “Making a strategy work is harder than developing it” [3].

Implementation is often defined as the “Achilles heel” of the strategic management process [2]. It is one thing to develop a strategy that seems to be winning, but quite another thing to successfully implement it. “Companies that achieve strategy implementation will succeed” [1]. “Making a strategy work is harder than developing it” [3].

The definition of this term speaks about the complexity of the strategy implementation process. Strategy implementation is “a dynamic, iterative and complex process to achieve strategic goals and turn strategic plans into reality. The process consists of a series of decisions and actions of managers and employees, which are influenced by a number of interrelated internal and external factors” [4].

As stated in a popular educational publication: “Strategy execution management is more an art than a science” [5]. This statement is not a tribute to fashion, but a statement of the fact that by now there are no clear guidelines that would describe the consistent steps to implement the strategy. This part of the company's strategic management is the least formalized both in terms of the process and the result achieved. The management literature over the years has focused mainly on demonstrating new ideas for planning and formulating strategy, but it has tended to neglect execution [3].

This part of the company's strategic management is the least formalized both in terms of the process and the result achieved. The management literature over the years has focused mainly on demonstrating new ideas for planning and formulating strategy, but it has tended to neglect execution [3].

Understanding the importance of this stage and its poor elaboration served as the basis for the emergence of relevant studies, numerous theories, approaches that demonstrate a special "status" of the implementation stage. Up to the point that the implementation stage is assigned the role of the company's strategy. “Implementation is strategy” is the title of a book by a certain Laura Stack [63]. Unfortunately, not everyone has this understanding. Moreover, in Russia this part of strategic management is still out of the focus of attention, primarily of practitioners.

In this regard, the purpose of this book is to attempt briefly, but in a volume sufficient for practical application, to present the existing world experience in implementing the strategy. In fact, this experience comes down to the need to translate strategic thought into strategic action in the dynamic environment of the company.

Moreover, the author seeks to show that the implementation of a strategy is a logical set of related actions. As a rule, managers, faced with the problem of strategy implementation, plunge into the abyss of decisions on a variety of strategic and operational problems that are not easy to understand. The “when everything matters” approach does not contribute to the successful implementation of the strategy. “When everything matters, then nothing matters.” A consistent, understandable methodology can help guide strategic behavior, motivate the management team, and enhance a firm's ability to navigate.

The implementation of the strategy covers all aspects of the organization from top to bottom. At this stage, both functional areas and individual areas of business can be affected. Let me remind you that organizations are complex systems that consist of various interrelated elements. Implementing a new strategy, or even adjusting an existing one, requires changes to every element of this complex formation called organization. There is an opinion that it is enough to approve the strategy, providing for change only in a limited part of the organization. This is a false, unprofessional position. Even minor changes in individual current business processes entail numerous adjustments in related processes. Without a logically coherent model for the implementation of the strategy, it is quite difficult to achieve coordinated actions.

Implementing a new strategy, or even adjusting an existing one, requires changes to every element of this complex formation called organization. There is an opinion that it is enough to approve the strategy, providing for change only in a limited part of the organization. This is a false, unprofessional position. Even minor changes in individual current business processes entail numerous adjustments in related processes. Without a logically coherent model for the implementation of the strategy, it is quite difficult to achieve coordinated actions.

In addition, we note that the implementation of the strategy is one of the most difficult areas of change management. At the strategy implementation stage, responsibility shifts from a relatively narrow group of strategy developers to a wide range of employees who become executors. This shift in responsibility becomes much easier if the firm's managers and employees understand the business, feel part of the company, participate in strategy development, and are committed to the company's interests. Without employee understanding of the strategy and employee commitment to implement the strategy, organizations face significant challenges.

Without employee understanding of the strategy and employee commitment to implement the strategy, organizations face significant challenges.

The foregoing allows us to formulate a kind of terms of reference for the book on the implementation of the strategy. Managers need to see the “big picture”, an overview of key decisions or actions that together provide a pattern, model, or guideline for effectively executing strategy implementation based on the logic of the business. They must understand the contextual forces that affect the operation of this model. The presence of such a model will allow you to discipline the process of implementing the strategy, adhere to the logic of the process and increase the likelihood of success in strategic management.

In addition, managers should use performance management methodology (CPM [2] ) when implementing strategy. Performance management covers the full range of tasks related to the organization's strategy. The most common of these include the balanced scorecard, OKR, Hoshin Kanri. These methodologies act as an organizational form of a roadmap.

These methodologies act as an organizational form of a roadmap.

The purpose of the book is to help both mature and developing companies organize not only the development and selection of a strategy, but also its implementation. Strictly speaking, the book is intended as a textbook for those who are taking their first steps in strategic management, however, I believe that it can be useful for those who have experience, but do not have a general view of the implementation process.

The author realizes that it is impossible to present all the details in a short book. However, you can make the task as easy as possible by adding to it a number of practical recommendations for the implementation of certain aspects of solving the problem.

Taking into account these preliminary remarks, the structure of the book has been built. First, it is published in two parts. In the first part of the book, which is called "Roadmap for the implementation of the strategy," the barriers and obstacles that stand in the way of companies in implementing the strategy are considered, and a model of decisions and actions is proposed to overcome the barriers. This model plays the role of a kind of road map. Next, we consider the sequence of actions to solve a set of problems in the implementation of the strategy. In addition, additional factors that should be considered when implementing the strategy are considered.

This model plays the role of a kind of road map. Next, we consider the sequence of actions to solve a set of problems in the implementation of the strategy. In addition, additional factors that should be considered when implementing the strategy are considered.

The second part of the book, called "Building Strategy Implementation Management Systems", discusses how to provide management functions for strategy implementation.

The appendix lists some of the tools that are useful in implementing the strategy.

Chapter 1. Strategy implementation algorithm

1.1. Barriers to implementation

The implementation (execution) of the strategy is currently one of the most important topics of strategic management. Globally, managers spend billions of dollars on consulting and training in the hope of creating brilliant strategies. Too often, however, brilliant strategies do not lead to brilliant results. Companies face significant challenges in translating strategies into action. As Lawrence Grebignac noted [3] "formulating a coherent strategy is difficult for any management team, but making that strategy work - implementing it throughout the organization - is even more difficult" [6].

As Lawrence Grebignac noted [3] "formulating a coherent strategy is difficult for any management team, but making that strategy work - implementing it throughout the organization - is even more difficult" [6].

The problem was not born today, for quite a long time it has been high on the agenda of top managers of companies, but, oddly enough, the world community has only recently realized that strategies are not implemented automatically. This was facilitated by a number of studies, the essence of which can be formulated in this way, "strategy formulation and implementation matters - strategy (formulation) and execution are the main "management methods" - you need both a clearly articulated and focused strategy and the ability to implement a strategy to become a winner in your market!” [7].

Therefore, the implementation of the strategy is considered a prerequisite for high performance. However, in fact, the implementation of the strategy is a source of frustration in many companies. In both academic and consulting studies, there is a significant failure rate in the implementation of strategies - from 40 to 90 percent [7]. This has led many researchers and practitioners to conclude that strategy execution is not only the biggest problem facing businesses today, it is something that no one has ever satisfactorily explained. This conclusion was made long ago, but nothing has changed today [7].

In both academic and consulting studies, there is a significant failure rate in the implementation of strategies - from 40 to 90 percent [7]. This has led many researchers and practitioners to conclude that strategy execution is not only the biggest problem facing businesses today, it is something that no one has ever satisfactorily explained. This conclusion was made long ago, but nothing has changed today [7].

Unlike strategy formulation, strategy implementation, especially in a business environment, is often seen as a kind of craft. As a result, current knowledge about the nature of strategy implementation and the reasons for its success or failure in the business environment is still limited. As the Oxford researchers state, “main textbooks on strategic management often have a section on strategy implementation, which is usually 20% or less of the book. The chapters on strategy implementation focus on organizational structure, control and management. Some of these textbooks also include a chapter on strategic leadership. Research on each of these topics is also limited for implementation purposes” [8]. A natural question arises - why?

Research on each of these topics is also limited for implementation purposes” [8]. A natural question arises - why?

The answer is simple, because the implementation of the strategy is a very difficult task, and not many people can feel this complexity and, moreover, overcome it.

Research and experience in the implementation of strategies indicate a number of obstacles (barriers) to the implementation of the strategy. The analysis of these barriers is very indicative and can prompt a thinking manager to solve many problems. However, both the number and nature of these barriers are interpreted by many authors in different ways. Therefore, we are compelled to dwell on only a few of them.

In the Russian Federation, due to the prevalence of books on the balanced scorecard, it is believed that the number of such barriers is four [1, 8].

Communicating the vision and strategy to the direct executors. An obstacle to the implementation of the strategy is a situation in which the management cannot translate its vision and strategy into the plane of understandable and achievable tasks. This leads to the fact that the ongoing efforts are fragmented. In turn, this situation is due to the lack of consensus among management on the overall concept and strategy of the company.

This leads to the fact that the ongoing efforts are fragmented. In turn, this situation is due to the lack of consensus among management on the overall concept and strategy of the company.

Lack of relationship between the strategic goals of the organization and the goals / objectives of individual employees. Usually, the activities of business units and individual performers are focused on the implementation of the budget and the solution of tactical (short-term) tasks. At the same time, the achievement of strategic (long-term) goals is practically blocked. This barrier is due to the inability of departments and individual performers to align individual goals and goals of departments with the company's strategy. In many cases, the source of this barrier is the incentive system, which is aimed at achieving short-term financial performance and current orders.

Allocation of resources that has nothing to do with strategic priorities. In many cases, strategic planning and the preparation of the annual budget are independent processes that seem to exist in "parallel planes". As a result, budget and resource allocation are largely irrelevant to strategic priorities. The discussion of budget execution is reduced to finding out the reasons for the deviations between the current situation and budget indicators, but not to discussing the results of achieving strategic goals.

As a result, budget and resource allocation are largely irrelevant to strategic priorities. The discussion of budget execution is reduced to finding out the reasons for the deviations between the current situation and budget indicators, but not to discussing the results of achieving strategic goals.

Lack of feedback in the process of implementing the strategy. The management systems implemented in most companies are based on information about current operating results. At the same time, management accounting is built on a comparison, as a rule, of real financial or in-kind indicators with monthly and quarterly plans. Not enough attention is paid to the analysis of strategy implementation indicators and success factors. As a result, the company does not have sufficient information about the implementation of the strategy.

According to Kurt Werweyr [4] there are five main reasons for the failure of the strategy [7]:

Strategies are replaced by goals or inspiring slogans. Strategy implementation is only successful if the company has a clearly articulated strategy. In reality, however, few companies have a genuine strategy. Managers often confuse strategy with "emotional" slogans. For example, "our strategy is to be number 1 (or number 2) in this particular industry," or "our strategy is to increase shareholder value by 30 percent over the next three years." These statements are not strategies - they are goals or aspirations. These statements are about what the company wants to be or wants to achieve, not how it will get there. Strategies should provide direction and coherence for the organization; financial goals do not provide this consistency.

Strategy implementation is only successful if the company has a clearly articulated strategy. In reality, however, few companies have a genuine strategy. Managers often confuse strategy with "emotional" slogans. For example, "our strategy is to be number 1 (or number 2) in this particular industry," or "our strategy is to increase shareholder value by 30 percent over the next three years." These statements are not strategies - they are goals or aspirations. These statements are about what the company wants to be or wants to achieve, not how it will get there. Strategies should provide direction and coherence for the organization; financial goals do not provide this consistency.

Functional strategies do not replace business strategies. Many companies have strategies for HR, operations, sales, IT, and most other departments, but no overall business strategy. Strategy implementation is difficult, if not impossible, when a firm lacks a coherent business strategy.

Traditionally, a business unit refers to any organizationally separate unit that has external customers. These divisions are responsible for generating profits, and the functional integration within such divisions indicates that they are responsible for managing the entire value chain, including activities such as R&D, manufacturing, sales and marketing, as well as some ancillary activities, such as IT and HR.

These divisions are responsible for generating profits, and the functional integration within such divisions indicates that they are responsible for managing the entire value chain, including activities such as R&D, manufacturing, sales and marketing, as well as some ancillary activities, such as IT and HR.

Firms are organized differently today. The corporation is split and the value chain deconstructed into separate divisions that have different economic and cultural imperatives [5] . For example, production management focuses on scale and efficiency, while R&D units focus on speed and creativity. The marketing and sales departments require high customer acquisition costs, which will allow the company to generate more revenue. This is why many corporations now have large R&D units, production units, and sales units. Managers call these divisions “business units,” but they are not: they are large functional units, not business units.

The problem with deconstructing the value chain is that managers and employees no longer see the big picture. As different units pursue different goals, the coherence that the strategy provided has disappeared.

As different units pursue different goals, the coherence that the strategy provided has disappeared.

Implementation of the strategy is too fragmented. The implementation of the strategy creates problems by the fact that the phrase implementation of the strategy is interpreted in different ways. Some see strategy execution as a measurement and management exercise in which management translates the strategy into key metrics and cascades it further down the organization. Others see strategy implementation as creating an organizational culture that allows people to act on the strategy. Still others view implementation as strategic portfolio management.

Strategy implementation is everything and more. Too often, leaders address only one issue within the entire task of implementing the strategy and approach its implementation in too fragmented way. Strategy execution is a broad field that cuts across many different areas of management, from direction and goal setting to HR, operations, culture, and so on. The executors of the strategy must be jugglers. Executing a strategy requires visionary capabilities as well as process and people management capabilities. While some managers often excel at one of these, they may not have the skills to perform other tasks equally well.

The executors of the strategy must be jugglers. Executing a strategy requires visionary capabilities as well as process and people management capabilities. While some managers often excel at one of these, they may not have the skills to perform other tasks equally well.

Managers discuss strategy but forget to translate strategy into action.

The implementation of the strategy involves the coordination of various activities, as well as the creation of a commitment to the adopted strategy throughout the organization. However, it takes time to create an organizational context that stimulates large-scale action. Too often leaders don't take the time to create that context. They communicate, discuss, make plans and express good thoughts, but they are not in a hurry to translate the strategy into action. Translation is hard: more work, more attention to detail and more attention to people.

Implementation of the strategy consists in launching a whole range of measures, including those aimed at stimulating the appropriate behavior of employees. This requires special management of the organization. In high-performing organizations, employees don’t just perform tasks regularly—they are allowed to take the initiative, work collaboratively, and control and regulate themselves. In other words, managers must place considerable emphasis on creating an attractive organizational climate, structure, and collaborative culture. Few leaders set themselves such tasks and really know how to do it.

This requires special management of the organization. In high-performing organizations, employees don’t just perform tasks regularly—they are allowed to take the initiative, work collaboratively, and control and regulate themselves. In other words, managers must place considerable emphasis on creating an attractive organizational climate, structure, and collaborative culture. Few leaders set themselves such tasks and really know how to do it.

Implementing a strategy requires leadership. The four aspects described above indicate that implementation work requires leaders, not just managers. The implementation of the strategy is not about delegating parts of the strategy to functional managers, so that the marketing manager handles marketing issues and the operations manager manages operational issues. The head of the organization, or at least someone from the business management team, should be the main implementer of the strategy. The implementation of the strategy is difficult because it forces people to change their behavior.