Books with high frequency words

10 Amazing Books to Teach Sight Words to Beginning Readers

Memorizing sight words is really important for beginning readers so I try to integrate instruction into as many parts of my day as I can. For that very reason, these 10 books to teach sight words are read often by both me and my students.

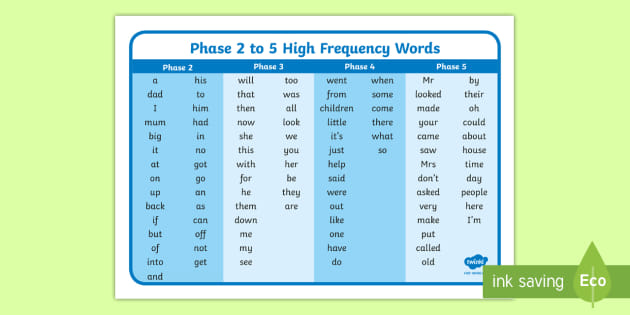

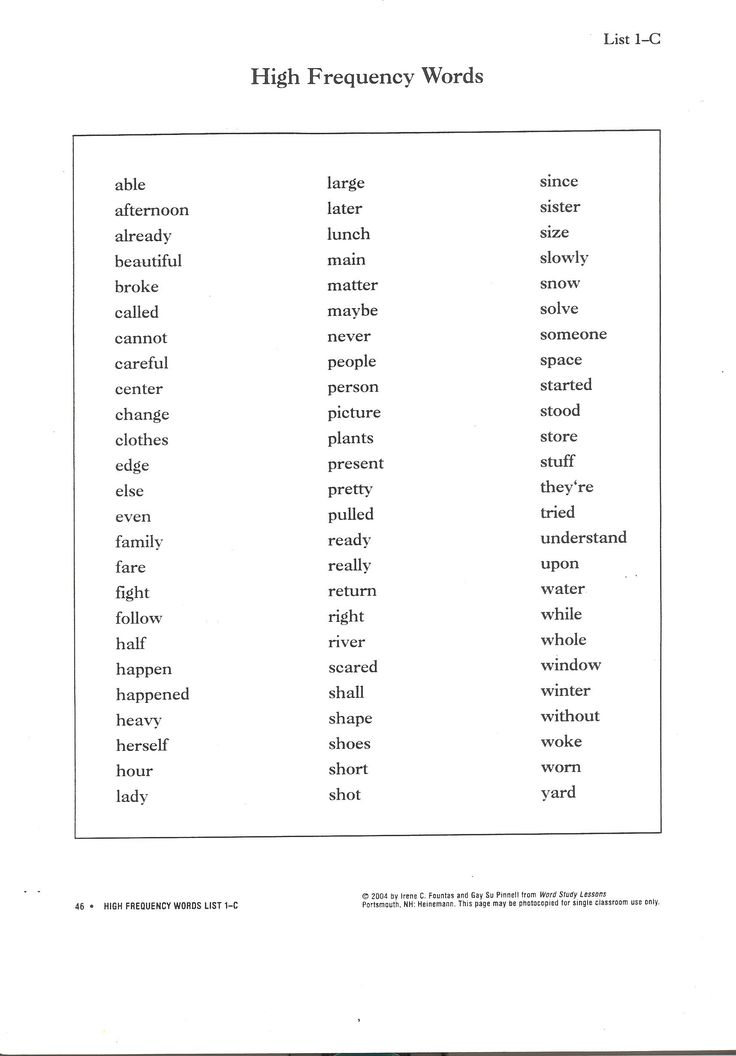

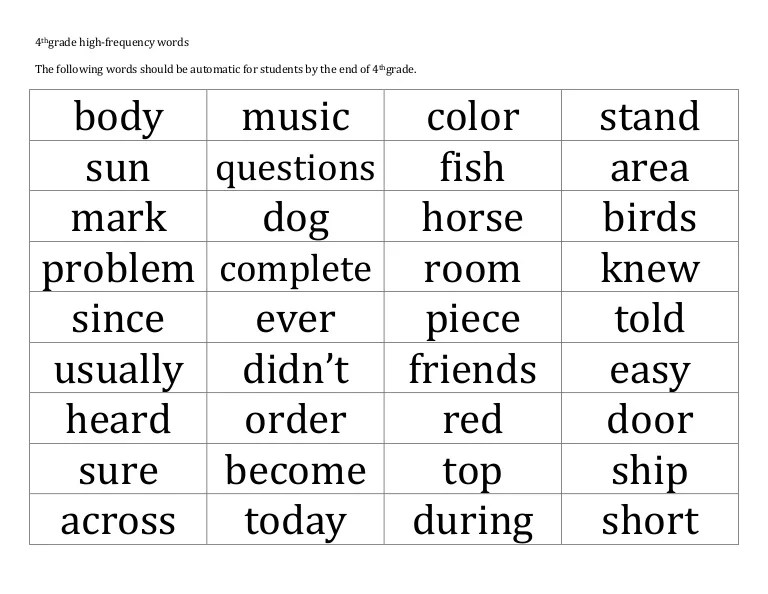

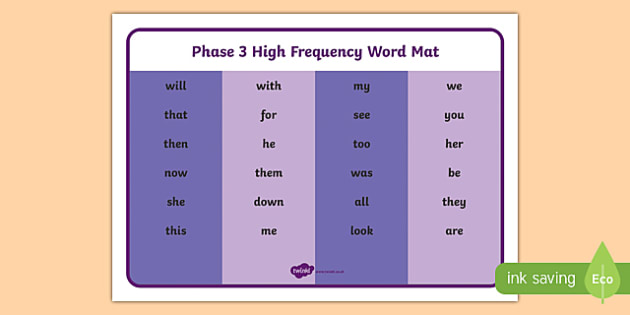

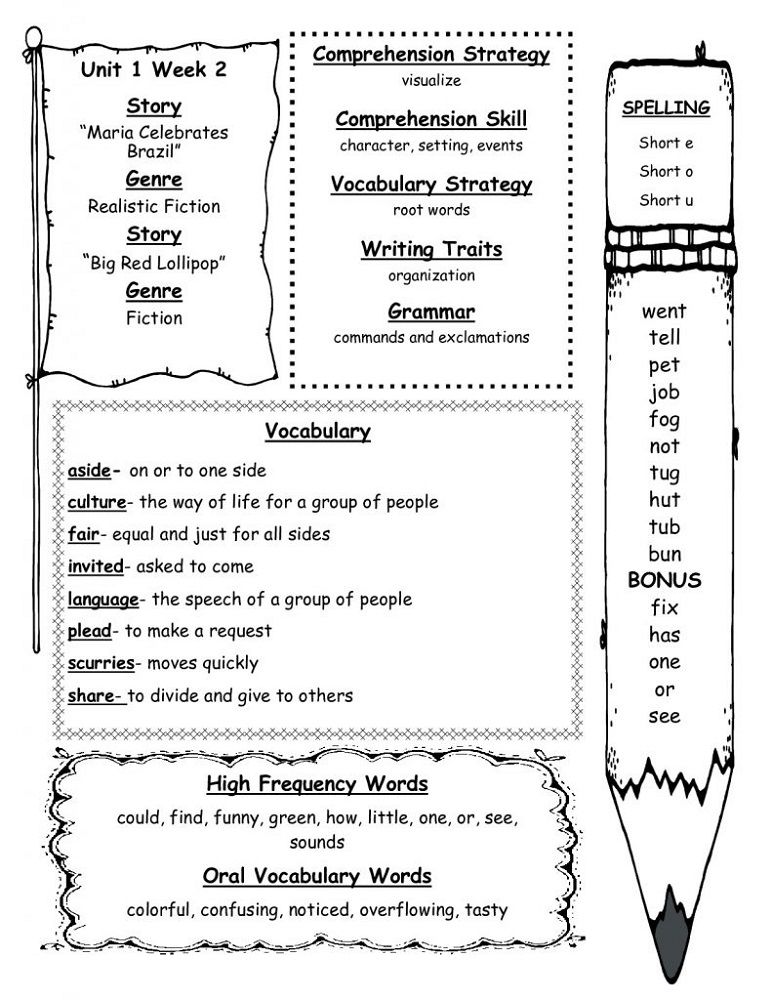

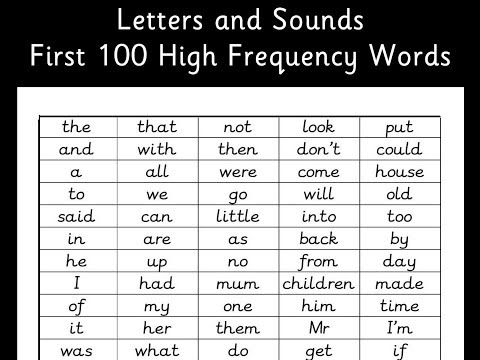

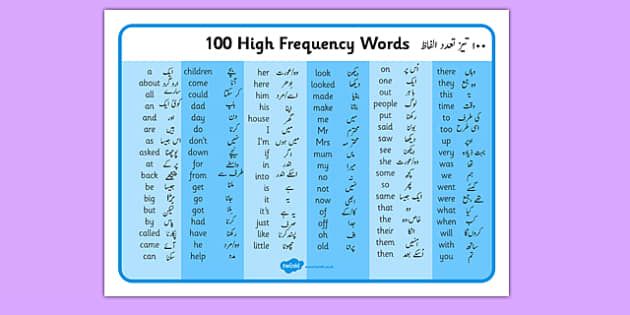

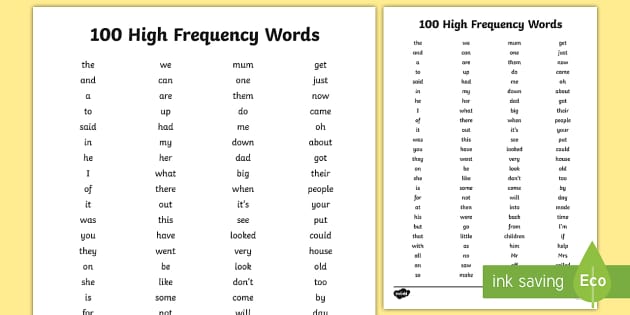

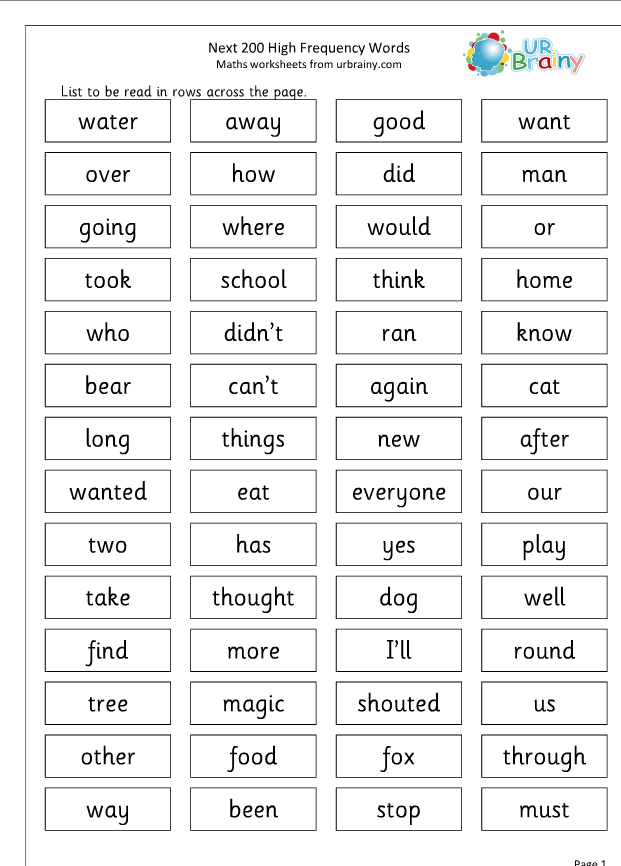

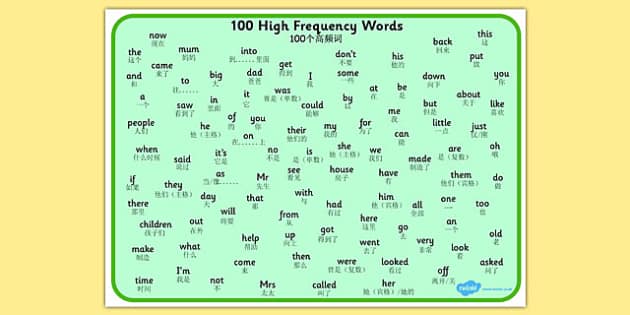

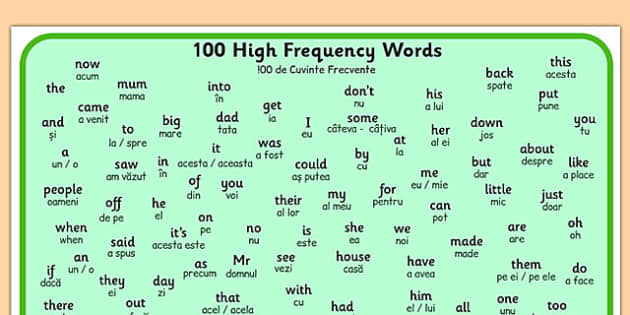

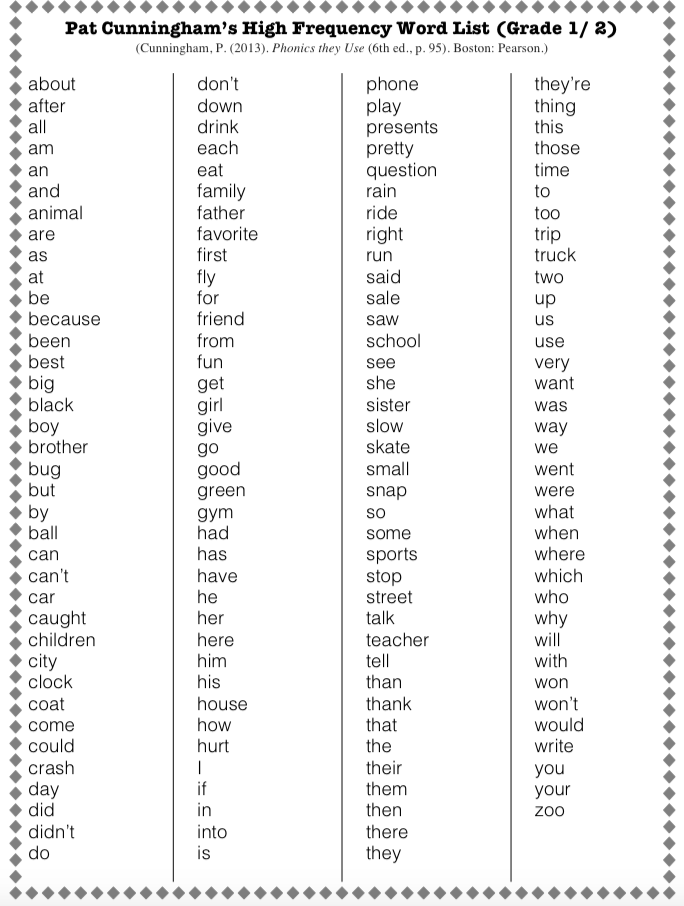

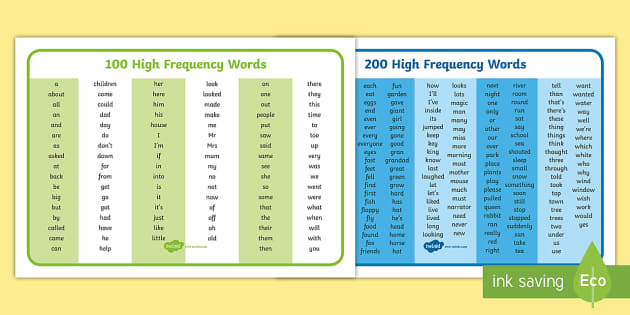

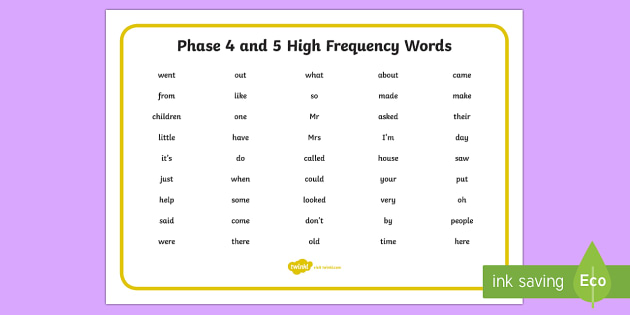

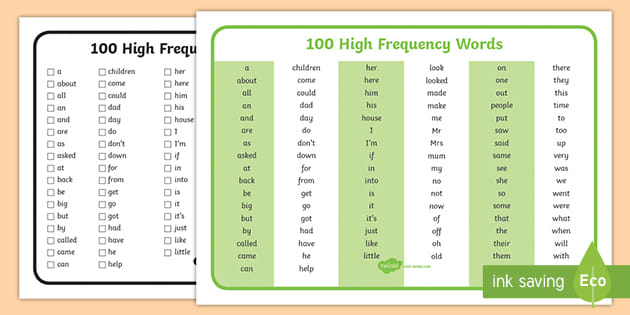

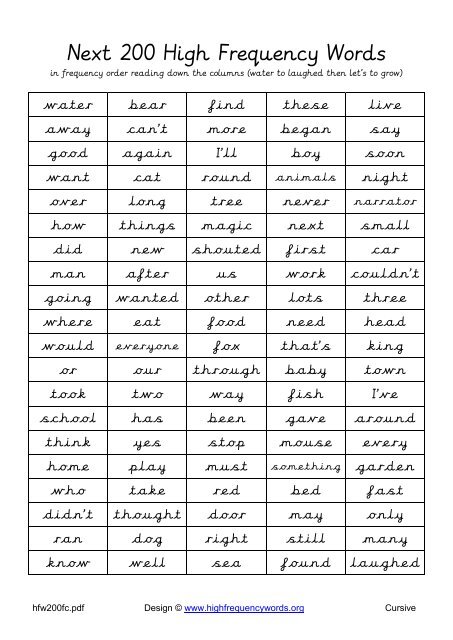

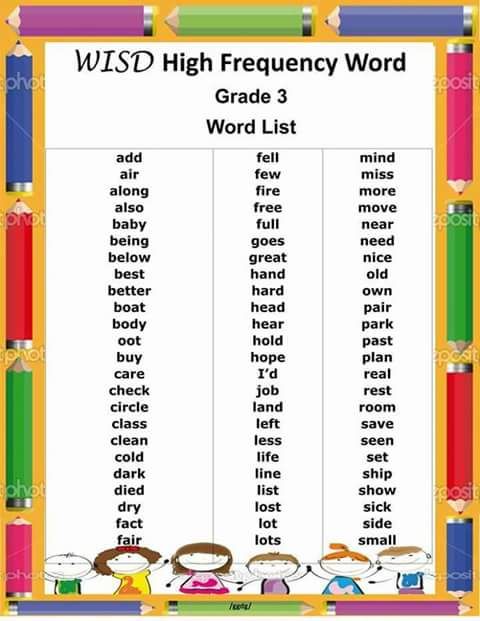

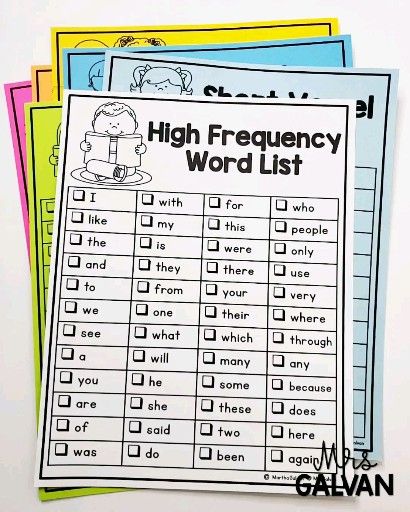

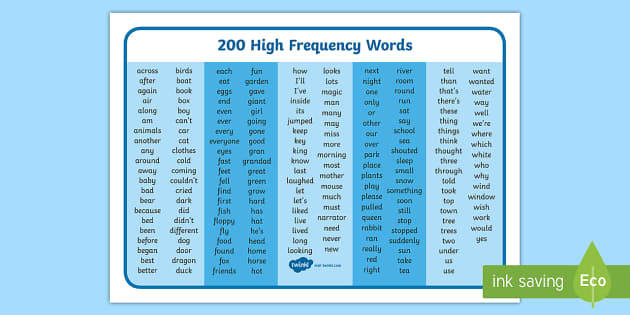

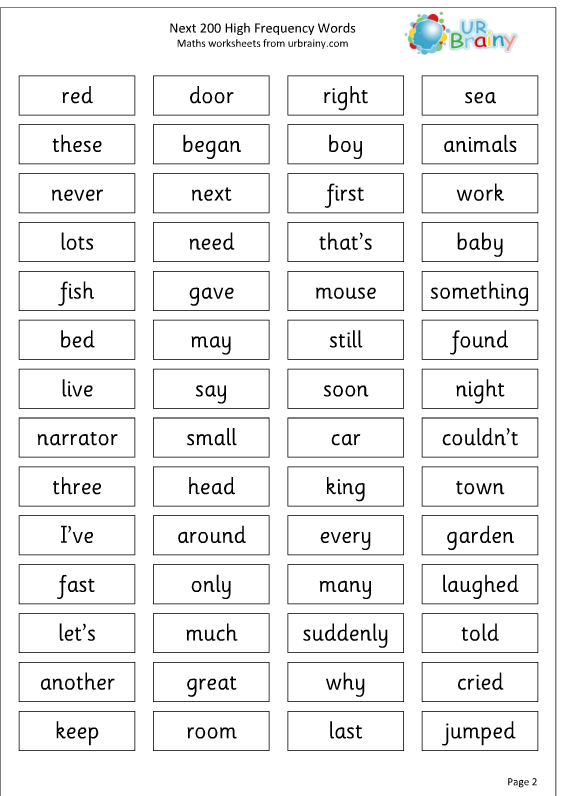

There are over one hundred sight words and high frequency words that are so common they show up in the text we read quite frequently.

Many of the books we read aloud to our students are full of rich vocabulary but they are also peppered with sight words and high frequency words.

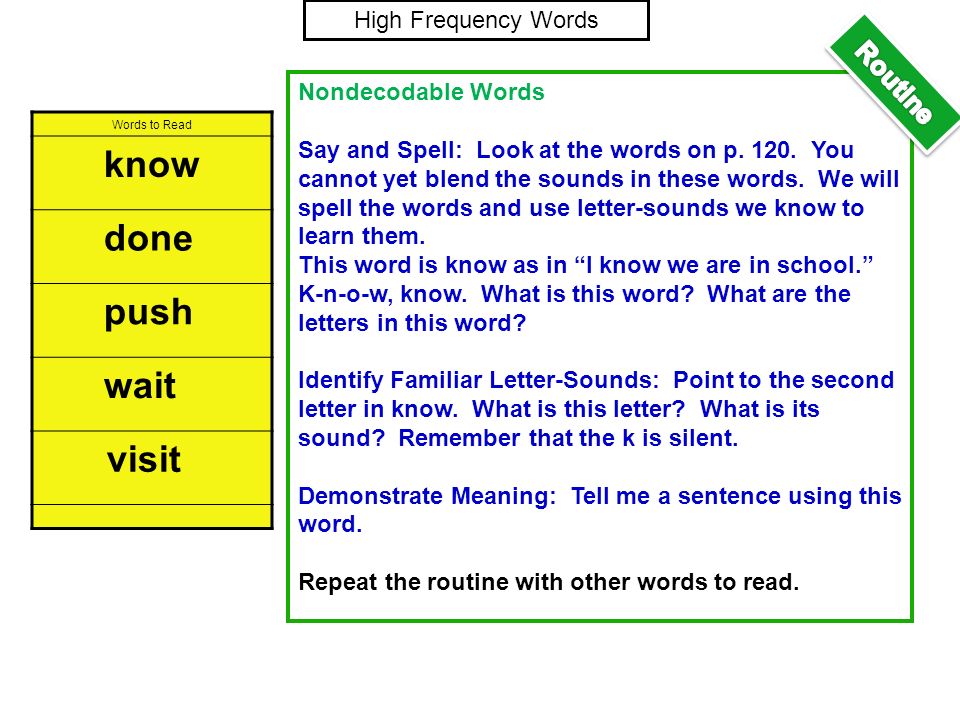

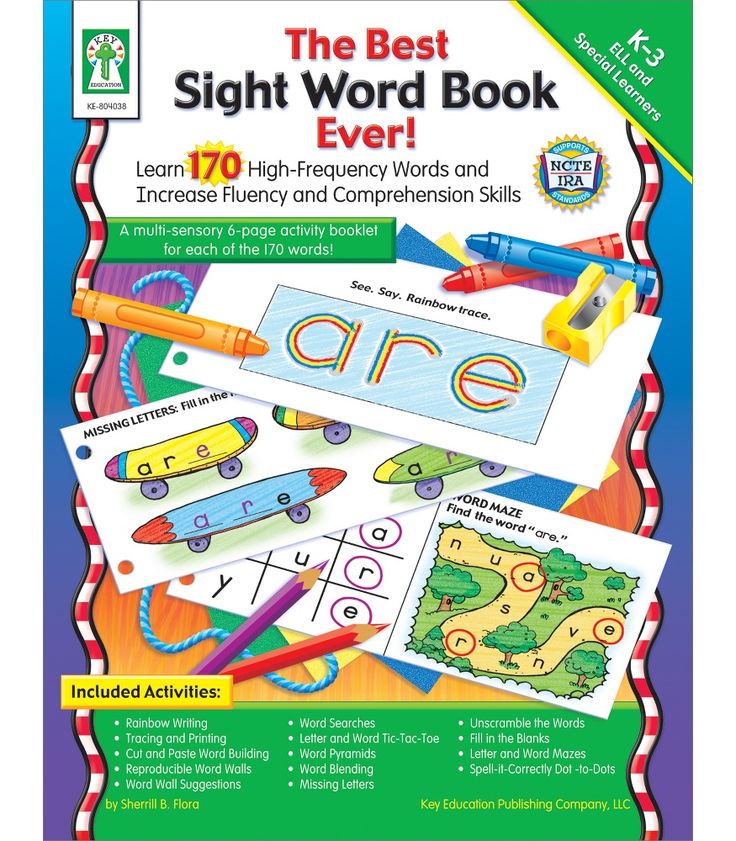

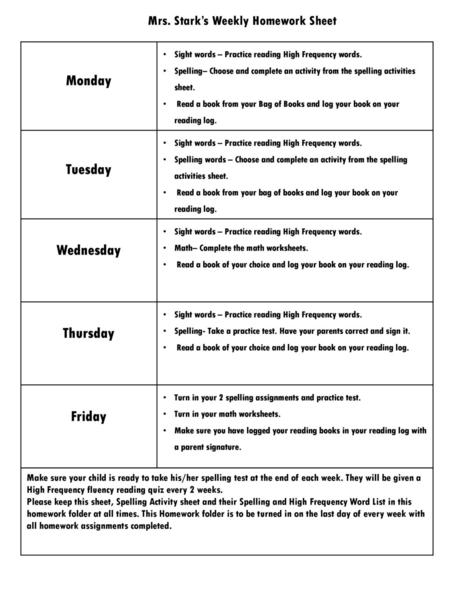

I love to teach sight words and give practice in tons of creative ways. I provide hands-on practice, show my favorite videos and give them the chance to build the sight words in literacy centers.

As teachers, we know our students learn best in context. Hearing, seeing and connecting these words within a text is super powerful for our students!

I find that reading books that prominently feature sight words can help my students memorize them, too. Many of the books on this list feature repetitive text that includes common sight words.

After I read these books aloud, they find a home in my classroom library. My students love to reread them. Even if they aren’t reading words quite yet, they retell the story and often times use the exact same wording. They can remember it because of the repetition! That is one of the ways these books to teach sight words are so beneficial.

Note: Did you know there is a difference between sight words and high frequency words? I thought they were the same thing for the longest time. Now that I know the difference, I approach instruction differently. You can read more about that here!

This post contains affiliate links. By purchasing through this link, we get a small commission. Rest assured – we only share links to products that we know and love!

Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?

It’s not so hard to see why this book would make the list of books to teach sight words! The question “What do you see?” is made of four sight words that we introduce at the beginning of the school year!

This question repeats over and over again in the story along with the reply, “I see a _____ looking at me. ” More sight words!

” More sight words!

My students love to reread this story in library or retell it with puppets. They are getting multiple exposures to really common words every single time they do!

Home

I absolutely love this book by Carson Ellis. The whimsical illustrations capture both me and my students so completely. The topic is one that we discuss a lot in my classroom, too, so it easily fits into our curriculum.

Home explores the many different types of homes as well as the varied places they can be. It includes the sentence frame “A home is a…” as well as “Some homes are…” These phrases repeat through the book.

I love that we can dig deeper into this simple story by exploring the new vocabulary and broadening our world view, too!

Where Is the Green Sheep?

This adorable book uses the phrase “Here is the…” and the question “Where is the…?” as we search for the green sheep.

The book explores opposites like thin and wide as well as colors like red and blue. Most of these are also sight words or high frequency words!

Most of these are also sight words or high frequency words!

My students enjoy the cadence of this read aloud as they listen and often help with the words to describe the different sheep. It is a really popular one to reread in the library.

The Bus for Us

Tess is waiting for the bus for her first day of school. She has never ridden one before. Her brother stands with her as she waits and asks “Is this the bus for us, Gus?”

We see all sorts of vehicles like taxis, fire engines and tow trucks. They peek their nose in on one page so students can guess! They absolutely love this!

The repetitive text is perfect for rereading and recognizing those common sight words.

From Head to Toe

This book introduces different animals and what they do. For example, the penguin says, “I can turn my head. Can you do it?” On the next page a child says “I can do it.”

This book is super engaging because they can do the actions the animals are doing. The text is really repetitive so they actually start to answer with the words written in the book: I can do it.

We read this book many times throughout the year and it is also one of my most popular library books.

Jump, Frog, Jump

Jump, Frog, Jump follows the same kind of pattern as the “There was an old lady who…” style books. Frog is trying to escape being eaten by the different animals in the pond.

The simple, repetitive text is a favorite of my students. Each new animal fills this sentence frame: “This is a ____ that ____ after the frog.” Then the following page says “Jump, Frog, jump!”

My students love to warn Frog to jump! Will he escape? You’ll have to read it to see!

Five Trucks

Five Trucks is about five different trucks (obviously ?). You read about their different characteristics and jobs.

The adjectives used to describe the trucks include tons of great sight words and high frequency words, like large and small. The book also refers to the trucks as first, second, third, fourth and fifth, which are all words I want my students to learn as well. #ordinalnumbers #yay

#ordinalnumbers #yay

We read this book when we talk about communities. It is especially appealing to my students who are fascinated by different forms of transportation.

I Want My Hat Back

I Want My Hat Back is about a bear who has lost his hat. He asks the animals he sees if they have seen his hat. There are a lot of opportunities to inference where the hat has gone.

It will leave your students laughing, I PROMISE.

The text in this book is SUPER simple. In fact, I would venture to say that almost all of the words are sight words!

This book is one of my favorites of all time. Including it in this list is a must for me! I love reading it aloud to my students and they love rereading it in the library.

If you haven’t read this one to your class, you NEED to. (Seriously!)

Frog and Toad

Frog and Toad books are well-loved classics for a reason. Students find the stories really engaging and relatable.

The text is simple and accessible and full of the sight words we start our year learning. Those are just a few reasons students come back to this series over and over again.

Those are just a few reasons students come back to this series over and over again.

I love to introduce Frog and Toad toward the beginning of the year. My students are fascinated by the chapters and Frog and Toad’s friendship.

Elephant and Piggie Books

I have saved my absolute FAVORITES for last. You cannot find better, more engaging sight word books to read aloud to your students than Elephant and Piggie books by Mo Willems.

Elephant and Piggie are friends who work through important issues like friendship, waiting and sharing. They do it in a really funny way that students relate to. Honestly, I enjoy the banter between the characters, too!

I own every single one of these books because they are just THAT GOOD. They are some of the first books my students read on their own in the library because they text is really simple and predictable. In addition to that, they are super engaging.

I chose these 10 books to teach sight words because they are ones both my students and I choose to read over and over again. I truly believe the repetition has helped them memorize more words!

I truly believe the repetition has helped them memorize more words!

How do you use books to encourage students to learn new sight words and practice familiar ones? I would love to know! Let me know below.?

If you’re looking for printable sight word practice, check out these Sight Word Sentences! Each page targets a sight word for tons of explicit practice.

10 books to help pre-schoolers learn sight words

Posted on

Posted in Book Reviews.

One of the best things we can do to prepare our little darlings for independent reading is help them to recognise sight words.

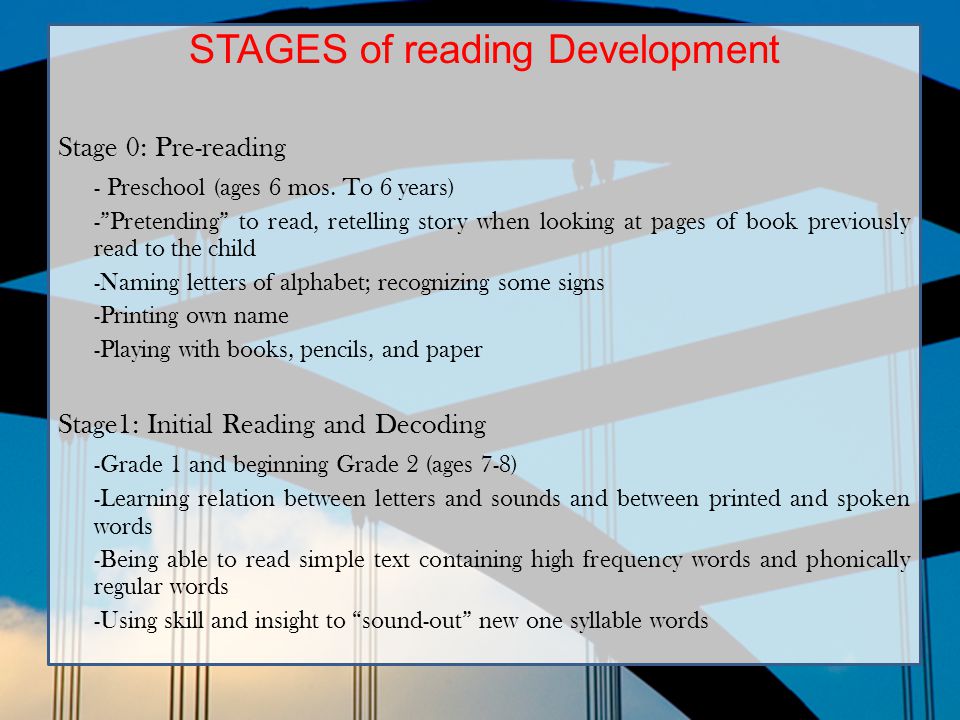

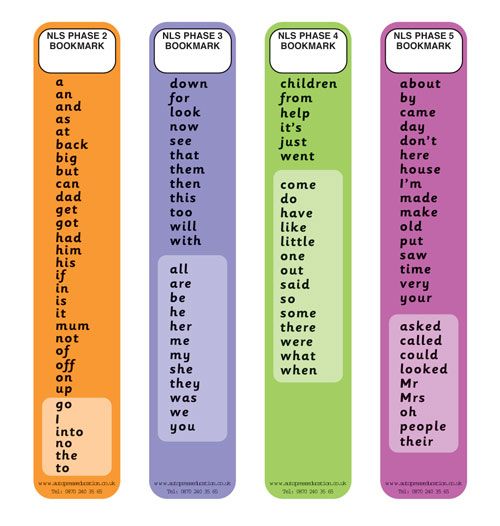

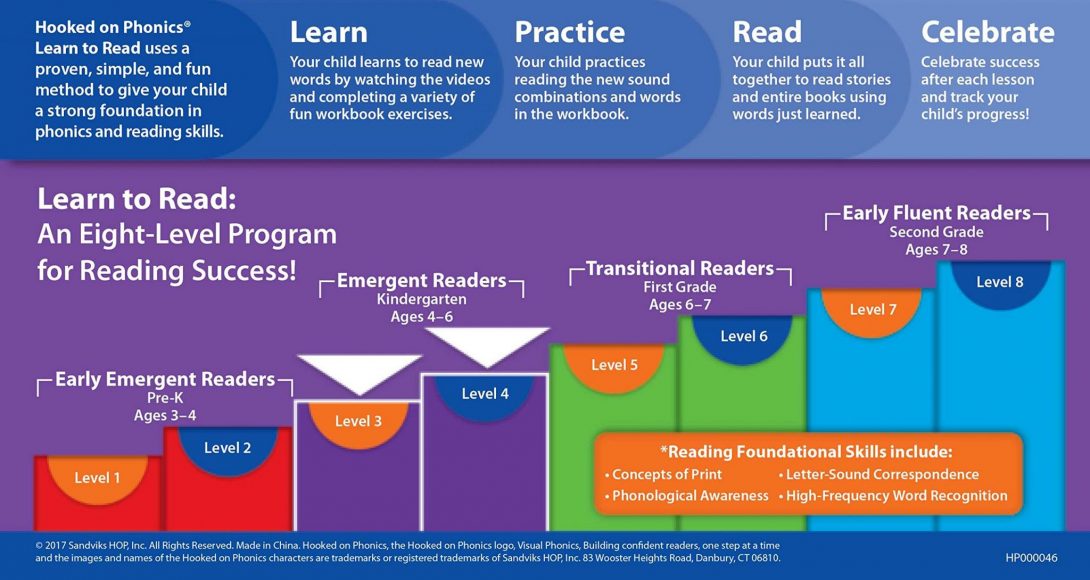

Sometimes called ‘popcorn words’, sight words are those high-frequency words that make up the majority of the words we read daily. By the end of their first year at school most kids will be expected to recall these 100 words without prompting – as a parent you can help by prepping your little bookworms with books that repeatedly use these words.

Here are 10 of the best books to help your kids remember their first 100 sight words.

Ant and Bee Count 123

Ant and Bee Count 123: by Angela Banner: First published in 1950, this delightful book continues to help children learn to read 65 years later! It focuses on word recognition and encourages story sharing. Poor Ant has hurt his head and has to stay in bed until he is better; luckily there are lots of nice things to count whilst he’s not feeling well. Sight words and counting in one book – score!

Me I Am!

Me I Am!: by Jack Prelutsky & Christine Davenier: This beautifully illustrated book tells the story of three individual personalities who follow their own path and stay true to themselves. A great book for teaching kids to be themselves, all while reinforcing key sight words throughout.

We love a book that can use clever verse to keep kids happily entertained while teaching them a valuable lesson!

Once Upon an Alphabet

Once Upon an Alphabet: by Oliver Jeffers: Letters of the alphabet work their lowercase and uppercase patooties off to make the words that tell stories, but in this delightful book by renowned author/illustrator, Oliver Jeffers, each letter of the alphabet has it’s own little story that reinforces each letter with an adventurous tale.

My First Sight Words

ABC Reading Eggs – My First Sight Words: by Sarah Leman: Combine this sight words book with Reading Eggs, the online program for learning to read, and your child will be independently reading in no time. There are 8 books in this series all up, each designed to teach your bookworm a new skill needed to learn how to read.

The Cat in the Hat

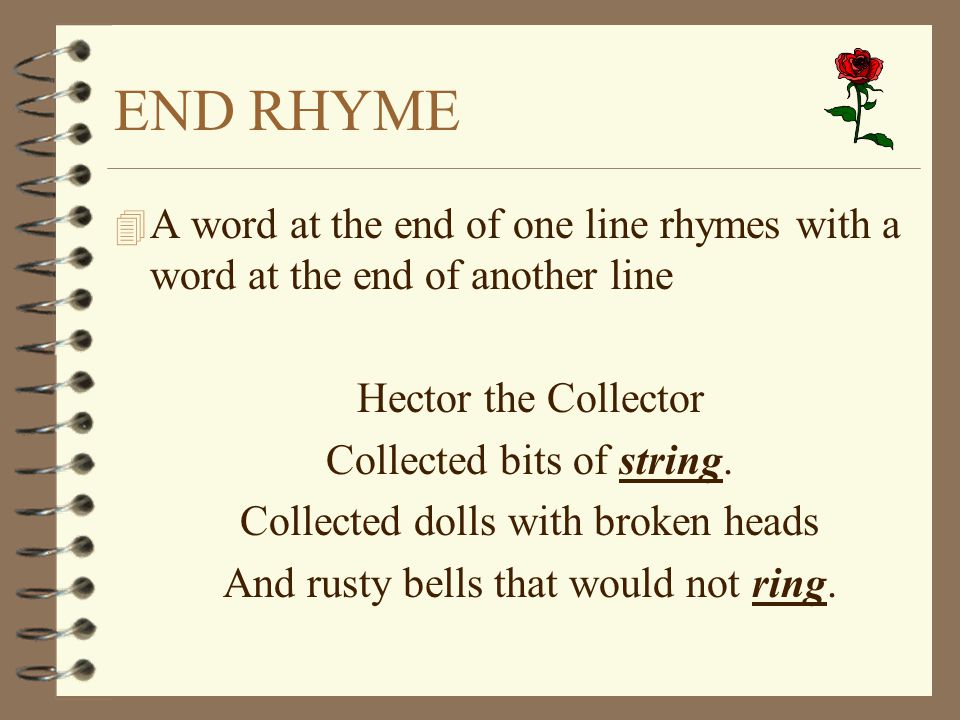

The Cat in the Hat by Dr Seuss: One of the world’s most-loved authors, Dr Seuss understood how to engage kids with creative, funny and sometimes downright silly story-telling. From a learning perspective, rhymes help kids to appreciate how words begin and end, and so are great for understanding how similar sounding words work.

I Need a Hug

I Need a Hug by Aaron Blabey: Best-selling author, Aaron Blabey, uses sight words repeatedly throughout his latest book, I Need a Hug. His witty use of rhyme helps kids to make connections between the way similar words sound, while keeping them entertained throughout.

Sight word readers

Collection of sight word readers by Rozanne Lanczak: Rozanne has a knack for creating readers that carefully introduce the repetition of one new sight word per book.

The beauty of focusing on repeating just one sight word per book is that it builds confidence in early readers, encouraging them to master that word and feel a sense of achievement.

Tug the Pug

Learn to Read with Tug the Pup and Friends! Box Set: Written by reading specialist Dr. Julie M. Wood, this set of books stars Tug the Pup and an endearing group of characters that will engage your little readers with their adventurous tales.

Each book features a strong emphasis on sight word vocabulary and picture/word connections, helping your kids to feel comfortable and engaged.

Nursery Rhymes

Nursery Rhymes by Lucy Cousins: Nursery rhymes help kids make connections with similar ending words. They also allow little readers to memorise verses, providing a sense of ‘can-do’ that is encouraging to kids.

They also allow little readers to memorise verses, providing a sense of ‘can-do’ that is encouraging to kids.

This colourful collection of nursery rhymes is by the creator of Maisy, another great book for early readers!

Read next …

Want some other ways to help get the kids reading? Check out these articles next:

- 13 fun ways to learn sight words

- Tips for parents to help children learn to read

- 21 cosy reading nooks for little bookworms

Posted in Book Reviews.

Share On

Read Flash Boys online. High-frequency revolution on Wall Street ”, Michael Lewis-Liters

Published with the assistance of the IS Nord-Capital

Editor V. Soapilov

Project M. Sultanova

computer layout K. Svishchev

Art director L. Benshusha

© Michael Lewis, 2014

Published with permission from Writers House LLC and Synopsis Literary Agency

© Edition in Russian, translation, design. Intellectual Literature LLC, 2015

Intellectual Literature LLC, 2015

All rights reserved. No part of the electronic copy of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including posting on the Internet and in corporate networks, for private and public use, without the written permission of the copyright holder.

* * *

Dedicated to Jim Pastorica [1] who never missed an opportunity to get involved in history

Preface to the Russian edition

Dear reader!

The Flash Boys hit America. Still would. The book opened up the world of high-frequency trading for people far from trading, mathematics and computer technology.

The author showed in detail how the industry has changed with the advent of high-frequency trading, described in detail the first steps, thoughts and achievements of the pioneers of high-frequency trading, including Russian mathematicians, physicists and programmers, such gurus as Sergey Aleinikov and Mikhail Malyshev.

In science and high technology, it often happens that when someone has already discovered something, and industry standards have already been created, then everyone is sure that this has always been the case, but believe me, it is always difficult for pioneers. Otherwise they would all be. It is very difficult to navigate and find a way out in new areas of human activity, to find your own strategy and follow it non-stop.

The book Flash Boys caused a flurry of indignation, protests and discussions in a second. After all, before the release of this fascinating investigation, no one really knew what they were doing in the dark rooms of hidden pools. “Stop manipulation!”, “Forbid!”, “Down with intermediaries on the stock exchange!” These are far from the most serious allegations that have been made against firms that have spent years of research and mountains of money creating algorithms for high-frequency trading. But over time, both industry experts and regulators discovered the fact that this is rather a new format of the old activity in the financial markets. At the moment, managers and clients of investment companies, along with traditional investment strategies, recognize a separate place on trading floors for high-frequency trading, and the possibility of fair competition among all participants in a new stage of market development.

At the moment, managers and clients of investment companies, along with traditional investment strategies, recognize a separate place on trading floors for high-frequency trading, and the possibility of fair competition among all participants in a new stage of market development.

The book in your hands, as well as the revolutionary speed of the new market, is impressive. With the help of vivid examples and comparisons, the pages of Flash Boys describe the most complex technological processes inside the trading core of the exchange, and the fate and moral choice of some characters in the recent history of the American market are really impressive. Have fun!

Yakov Shlyapochnik,Chairman of the Board of DirectorsIG Nord-Capital

A person must always have a code.

Omar Little [2]

Introduction

Open Windows to the World of Finance

Goldman Sachs, after being fired from the bank in the summer of 2009, he was arrested by the FBI and charged by the United States government with stealing Goldman Sachs computer code. Then it seemed strange to me that after the financial crisis, in which Goldman Sachs was seriously involved, only one of its employees was charged with causing some damage to the bank itself. It seemed even stranger to me that state prosecutors were arguing that this Russian should not be released on bail, since Goldman Sachs computer code could be "used for dishonest manipulation of the markets" if it fell into the wrong hands. (What, at Goldman Sachs, he was in clean hands? And if this bank could manipulate the markets, then couldn't other banks do it?) But perhaps the strangest thing about this business has to do with how much effort it took people, there were few of them to find an explanation for the act of the Russian programmer.

Then it seemed strange to me that after the financial crisis, in which Goldman Sachs was seriously involved, only one of its employees was charged with causing some damage to the bank itself. It seemed even stranger to me that state prosecutors were arguing that this Russian should not be released on bail, since Goldman Sachs computer code could be "used for dishonest manipulation of the markets" if it fell into the wrong hands. (What, at Goldman Sachs, he was in clean hands? And if this bank could manipulate the markets, then couldn't other banks do it?) But perhaps the strangest thing about this business has to do with how much effort it took people, there were few of them to find an explanation for the act of the Russian programmer.

And here I am not referring so much to his crime as to his work. As a rule, Aleinikov was called a "high-frequency trading programmer", but this phrase did not mean anything to me. In the summer of 2009, this technical term was not yet known to most people, even on Wall Street. What is High Frequency Trading (HFT)? And why was the code that allowed Goldman Sachs to deal with HFT so important that the bank's management needed to contact the FBI when it turned out that an employee had copied the code? If this code suddenly turned out to be so incredibly valuable and dangerous to the financial markets, then how did a Russian programmer who worked at Goldman Sachs for only two years get his hands on it?

What is High Frequency Trading (HFT)? And why was the code that allowed Goldman Sachs to deal with HFT so important that the bank's management needed to contact the FBI when it turned out that an employee had copied the code? If this code suddenly turned out to be so incredibly valuable and dangerous to the financial markets, then how did a Russian programmer who worked at Goldman Sachs for only two years get his hands on it?

I started looking for someone who could answer these questions for me. And my search ended in One Liberty Plaza, in a room overlooking the former World Trade Center. There was a small group of incredibly knowledgeable people in the room from all over Wall Street—the major stock exchanges, big banks, and HFT firms. Many of them left their highly paid positions to declare war on Wall Street, including trying to solve the problem created by Goldman Sachs, which hired a Russian programmer to create it. In addition, they were experts in the questions I was looking for answers to, as well as in many other questions that I did not think to ask. The latter turned out to be much more interesting than I expected.

The latter turned out to be much more interesting than I expected.

At first, I didn't have much interest in the stock market, although, like most people, I enjoyed watching it rise and fall. When the market crashed on October 19, 1987, I was hanging out on the 40th floor of One Liberty Plaza—the office of my then employer, Salomon Brothers, in the securities department. This crash was indicative. If you ever need proof that even insiders on Wall Street have no idea what's going to happen here the next moment, you have it. Everything was just going well, and suddenly, for some unknown reason, the US stock market collapsed by 22.61%. During the collapse of quotes, some brokers on Wall Street simply did not answer the phone so as not to fulfill the orders of clients to sell securities. And by doing so, the inhabitants of Wall Street have discredited themselves not for the first time, but now the authorities have intervened in the matter: they have changed the rules and instructed computers to do the work for imperfect people. Crash 1987 started this process, at first weak, but over the years it gained strength, and eventually computers completely replaced people.

Crash 1987 started this process, at first weak, but over the years it gained strength, and eventually computers completely replaced people.

Over the past decade, financial markets have changed at such a rate that our understanding of them no longer corresponds to reality. I'm willing to bet that most people draw a picture for themselves, limited by human imagination: some cable channels run a ticker at the bottom of the screen with tickers (symbols of securities), prices and volumes of transactions, and alpha males in jackets yell something to each other in the operating room with color marking. This picture is outdated - the world represented in it has sunk into oblivion. Since about 2007, fat-necked chumps in color-coded jackets have disappeared from the stock exchange pits, and if they are still there, they no longer decide anything. A few individuals still operate on the New York Stock Exchange and various exchanges in Chicago, but no longer control the financial markets and do not enjoy insider privileges. Trading in the US stock market now takes place inside black boxes located in heavily guarded buildings in Chicago and New Jersey. It's hard to tell what's going on inside these black boxes - the ticker on the cable TV screens barely reflects what's going on in the stock market. Open reports are vague and unreliable, not even a specialist can accurately explain what happens in the black boxes, or when, or for what reason. And a simple investor has no chance at all to learn the little that he needs to know. He logs into his TD Ameritrade or E*Trade or Schwab account, opens the tab with the ticker assigned to the security, and clicks on the Buy icon. And then what? He may be sure of what will happen after pressing a key on his computer, but believe me, this is not so. If he had known, he would have thought twice before pressing it.

Trading in the US stock market now takes place inside black boxes located in heavily guarded buildings in Chicago and New Jersey. It's hard to tell what's going on inside these black boxes - the ticker on the cable TV screens barely reflects what's going on in the stock market. Open reports are vague and unreliable, not even a specialist can accurately explain what happens in the black boxes, or when, or for what reason. And a simple investor has no chance at all to learn the little that he needs to know. He logs into his TD Ameritrade or E*Trade or Schwab account, opens the tab with the ticker assigned to the security, and clicks on the Buy icon. And then what? He may be sure of what will happen after pressing a key on his computer, but believe me, this is not so. If he had known, he would have thought twice before pressing it.

People hold on to old ideas about the stock market because it's more convenient for them; because it is very difficult to accept change; and also because the few who can help people are not interested in it. In this book, I have tried to describe the real situation. The result is a picture made up of many small fragments. They describe: Wall Street after the crisis; new financial inventions; computers programmed to act as soullessly as the programmer working with you could never do; people who come to Wall Street with certain ideas about the stock market only to realize that it works very differently. One of them, a Canadian (imagine!), found himself in the center of this world and compiled his pictures into a single and understandable whole. It still takes my breath away from his determination to open the windows to the world of American finance and show people what it has become.

In this book, I have tried to describe the real situation. The result is a picture made up of many small fragments. They describe: Wall Street after the crisis; new financial inventions; computers programmed to act as soullessly as the programmer working with you could never do; people who come to Wall Street with certain ideas about the stock market only to realize that it works very differently. One of them, a Canadian (imagine!), found himself in the center of this world and compiled his pictures into a single and understandable whole. It still takes my breath away from his determination to open the windows to the world of American finance and show people what it has become.

I was also struck by a Goldman Sachs high-frequency trading programmer arrested for stealing the bank's computer code. As an employee of Goldman Sachs, Sergey Aleinikov worked on the 42nd floor of One Liberty Plaza, where the Salomon Brothers trading floor was once located, and two floors above the place where I happened to witness the stock market crash. He, just like me at one time, did not want to stay in this building anymore and in the summer of 2009 he set off to seek his happiness. On July 3, Sergey flew from Chicago to Newark, New Jersey, and was blissfully unaware of the significance of his own person. He had no idea what would happen to him after landing. He had no idea how high the stakes were in the financial game he helped Goldman Sachs play. Oddly enough, but in order to assess the scale of these rates, it was enough for him to look out the window at the American soil that stretched below him.

He, just like me at one time, did not want to stay in this building anymore and in the summer of 2009 he set off to seek his happiness. On July 3, Sergey flew from Chicago to Newark, New Jersey, and was blissfully unaware of the significance of his own person. He had no idea what would happen to him after landing. He had no idea how high the stakes were in the financial game he helped Goldman Sachs play. Oddly enough, but in order to assess the scale of these rates, it was enough for him to look out the window at the American soil that stretched below him.

Chapter 1

Hidden in plain sight

In the summer of 2009, the fiber optic line began to take on a bed of its own as 2,000 people dug and drilled the ground, providing it with an unusual shelter necessary for its survival. 205 teams of eight people each, along with various consultants and inspectors, were now getting up early to decide how to make a hole in an innocent mountain, or tunnel under a river, or dig a trench along a country road without a shoulder - they all did without asking the obvious question: " For what? The communication line was a hard black plastic tube almost 4 cm in diameter, designed to contain 400 glass threads as thick as a human hair, but already now it gave the impression of a living being, an underground reptile with its own desires and needs. The line needed a direct underground passage, and it was laid, perhaps with the greatest tenacity in history. It took the same move to connect the data center (data center) located on the South side of Chicago [3] , with an exchange located in Northern New Jersey. But first of all, it was necessary to keep the very fact of laying the line secret.

The line needed a direct underground passage, and it was laid, perhaps with the greatest tenacity in history. It took the same move to connect the data center (data center) located on the South side of Chicago [3] , with an exchange located in Northern New Jersey. But first of all, it was necessary to keep the very fact of laying the line secret.

The workers were told only about their direct duties. Divided into small groups, they worked separately on different sections of the line and knew only the direction of laying - from where and where the line was going. They were specifically not told anything about her appointment, so that they would not let it slip.

One of those who took part in laying the line recalls: “All the time people asked us: “Is this a secret line? Government? And I just said, “Yeah.” The workers might not have been aware of the purpose of the line, but they knew that it had opponents - everyone, without exception, knew that they had to be on their guard. For example, if they saw that someone was digging the earth near the line, or noticed that someone was asking a lot of questions about it, they were obliged to immediately report this to the main office. In other cases, they were instructed to talk about it as little as possible. When asked about what they do, answer: “Yes, we are laying the cable.” Usually the conversation ended there, and if it continued, it did not lead to anything. The builders themselves were perplexed: after all, they were used to laying tunnels that connected cities and people, but this line did not connect anyone to anyone. As far as they could tell, its only purpose was to be laid as straight as possible, even if they had to cut through a mountain to do so, and not to detour the line along a more obvious route. What for?

For example, if they saw that someone was digging the earth near the line, or noticed that someone was asking a lot of questions about it, they were obliged to immediately report this to the main office. In other cases, they were instructed to talk about it as little as possible. When asked about what they do, answer: “Yes, we are laying the cable.” Usually the conversation ended there, and if it continued, it did not lead to anything. The builders themselves were perplexed: after all, they were used to laying tunnels that connected cities and people, but this line did not connect anyone to anyone. As far as they could tell, its only purpose was to be laid as straight as possible, even if they had to cut through a mountain to do so, and not to detour the line along a more obvious route. What for?

Most of the workers didn't even ask themselves this question until the very end of the project. Another recession was brewing in the country, and they were just glad to have a job. According to Dan Spivey, no one knew her purpose, and people began to speculate.

According to Dan Spivey, no one knew her purpose, and people began to speculate.

Spivey knew more than anyone about the purpose of this line or the trench being dug for it. Secretive by nature, he was one of those discreet Southerners who took the time to share whatever came into their mind with others. Spivey was born and raised in Jackson, Mississippi, and on those rare occasions when he opened his mouth, it sounded like he never left. He had just turned 40, but he was still as thin as a teenager and had the face of one of those tenant farmers that Walker Evans captured in his photographs. After a few years of dissatisfied work as a stockbroker in Jackson, Spivey left that job to, in his words, "do something more risky." As a result, he rented a place on the Chicago Board Options Exchange and “made the market” (constantly quoted stock prices, independently calculating transactions). Like other traders on the Chicago exchanges, Spivey understood how much money could be made selling futures contracts in Chicago at current prices at which individual shares were trading in New York and New Jersey. Thousands of times a day, prices fluctuated so much that it was possible, for example, to enter into a futures contract for an amount exceeding the total price of the shares indicated in it. To make a profit, it was necessary to act quickly in two markets at once. The very meaning of the word “quickly” has changed rapidly. In the old days, say before 2007, the speed of a trader's actions was limited by the limit of human capabilities. At that time, people worked on the trading floors of the exchanges, and if you wanted to buy or sell something, you had to contact them. In 2007, exchanges were already blocks of computers in data centers. And the speed of conducting transactions on them was no longer restrained by people. The only limit was the speed of the signal between Chicago and New York, or more precisely, between the data center in Chicago, located in the building of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and a similar center located next to the Nasdaq in Carteret, New Jersey.

Thousands of times a day, prices fluctuated so much that it was possible, for example, to enter into a futures contract for an amount exceeding the total price of the shares indicated in it. To make a profit, it was necessary to act quickly in two markets at once. The very meaning of the word “quickly” has changed rapidly. In the old days, say before 2007, the speed of a trader's actions was limited by the limit of human capabilities. At that time, people worked on the trading floors of the exchanges, and if you wanted to buy or sell something, you had to contact them. In 2007, exchanges were already blocks of computers in data centers. And the speed of conducting transactions on them was no longer restrained by people. The only limit was the speed of the signal between Chicago and New York, or more precisely, between the data center in Chicago, located in the building of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and a similar center located next to the Nasdaq in Carteret, New Jersey.

By 2008, Spivey realized how big the difference between the actual speed of transactions between these two exchanges and theoretically possible. Given the speed of light in an optical cable, a trader who wanted to trade on two exchanges at the same time could send his orders from Chicago to New York and back in about 12 ms (a millisecond is equal to 0.001 s). This is about 10 times faster than it takes for a human to blink rapidly. The data rates offered by various carriers (Verizon, AT&T, Level 3, etc.) were lower than this and also inconsistent. Today, it took 17 ms to send orders to both centers, and 16 ms tomorrow. With any luck, some traders stumbled upon the 14.65ms route controlled by Verizon. Traders called it "golden" because, by chance, they were the first to take advantage of the difference in prices between Chicago and New York.

Given the speed of light in an optical cable, a trader who wanted to trade on two exchanges at the same time could send his orders from Chicago to New York and back in about 12 ms (a millisecond is equal to 0.001 s). This is about 10 times faster than it takes for a human to blink rapidly. The data rates offered by various carriers (Verizon, AT&T, Level 3, etc.) were lower than this and also inconsistent. Today, it took 17 ms to send orders to both centers, and 16 ms tomorrow. With any luck, some traders stumbled upon the 14.65ms route controlled by Verizon. Traders called it "golden" because, by chance, they were the first to take advantage of the difference in prices between Chicago and New York.

Spivey couldn't believe that carriers didn't realize how much the data rate requirements had changed. Verizon not only overlooked the possibility of selling a special route to traders for fabulous money, but also did not seem to realize that it had a particularly valuable advantage. “All you had to do was order a few lines and wait for the result,” Spivey recalls. “They didn’t know what they had.” Yes, in 2008 the major telecoms didn't realize just how much the financial markets had changed the value of a millisecond.

“All you had to do was order a few lines and wait for the result,” Spivey recalls. “They didn’t know what they had.” Yes, in 2008 the major telecoms didn't realize just how much the financial markets had changed the value of a millisecond.

Spivey figured out what was going on after a thorough investigation. He went to Washington, D.C., and obtained a map of the fiber optic lines that connected Chicago to New York. Most of them were laid along the railroads and stretched from one major city to another. The lines leaving Chicago and New York initially approached each other in a straight line, but when they reached Pennsylvania, they began to wag and twist. Spivey studied the map of Pennsylvania and discovered the main problem - the Allegheny Mountains. Only the federal freeway crossed the Alleghanies in a straight line, but the law prohibited the installation of fiber-optic lines along the federal highways. Other roads and railways curved depending on the terrain. Then Spivey found a more detailed map of Pennsylvania and drew a line along it. He liked to call it "the most direct path permitted by law." Using dirt roads and paved roads, bridges and railroad tracks, and sometimes private parking lots, or front gardens, or cornfields, he could shorten the path laid to him by telecom operators by more than 160 km. What was to become Spivey's plan, and then his obsession, began with an innocent desire: he wanted to see how much the data transfer rate would increase if the path was shortened.

He liked to call it "the most direct path permitted by law." Using dirt roads and paved roads, bridges and railroad tracks, and sometimes private parking lots, or front gardens, or cornfields, he could shorten the path laid to him by telecom operators by more than 160 km. What was to become Spivey's plan, and then his obsession, began with an innocent desire: he wanted to see how much the data transfer rate would increase if the path was shortened.

In late 2008, with the global financial system in turmoil, Spivey traveled to Pennsylvania and hired a civil engineer there to take him along the ideal route. Two days in a row they got up at five in the morning and drove until seven in the evening. “On our way,” Spivey recalls, “we came across only small towns connected by very narrow roads, sandwiched between rocks on one side and sheer walls of rock on the other.” The railroad tracks, laid from east to west, deviated to the north or south, bypassing the mountains and were of little interest. Spivey says: "I didn't like anything that wasn't straight east to west and curved in some way." Country roads were more suitable for his purposes, but they were so wedged into rough terrain that there was only room for fiber optic cable under them. “To excavate the road, you would have to block it,” he explains.

Spivey says: "I didn't like anything that wasn't straight east to west and curved in some way." Country roads were more suitable for his purposes, but they were so wedged into rough terrain that there was only room for fiber optic cable under them. “To excavate the road, you would have to block it,” he explains.

The builder accompanying him probably thought Spivey was out of his mind. But when Spivey insistently pressed him for arguments against laying the cable, he could not explain why Spivey's plan could not be carried out, at least in theory. That's what Spivey wanted - to find out the reason why he shouldn't have done it. “I was just trying to figure out why no carrier has done this yet,” he says. “I thought that I would definitely meet some insurmountable obstacle along the way.” However, he could not find a single argument against laying the line, except for the civil engineer's argument that no one in their right mind would cut through the solid rocks of Allegan.

It was then, in his words, that he "decided to cross the line. " The line that separated the Wall Street boys who traded options on the Chicago stock exchanges from the local government and US Department of Transportation officials who defined the right-of-way that a private individual could use to build a hidden tunnel. He was looking for answers to the following questions: “What rules govern the installation of fiber optic cable? Who gives permission for this? The line also separated Wall Street people from those who knew how to dig trenches and lay fiber optic cables. “How long will it take? With what speed can a brigade equipped with the necessary equipment dig a tunnel in the rock? What equipment is required for this? How much could it cost?

" The line that separated the Wall Street boys who traded options on the Chicago stock exchanges from the local government and US Department of Transportation officials who defined the right-of-way that a private individual could use to build a hidden tunnel. He was looking for answers to the following questions: “What rules govern the installation of fiber optic cable? Who gives permission for this? The line also separated Wall Street people from those who knew how to dig trenches and lay fiber optic cables. “How long will it take? With what speed can a brigade equipped with the necessary equipment dig a tunnel in the rock? What equipment is required for this? How much could it cost?

Steve Williams, a civil engineer in Austin, Texas, received an unexpected phone call. Williams says: "My friend called and said, 'I have an old friend who has a relative who is in trouble and needs construction advice.'" Then he got a call from Spivey himself. “This guy,” Williams recalls, began to ask me about the size of containers and types of cables, about ways to lay them in solid rock and under river beds. A few months later, Spivey called him again to ask if Williams would be willing to oversee the laying of a 50-mile fiber optic line from Cleveland. “I didn’t know what I was getting into,” Williams admits, as Spivey didn’t tell him anything beyond what he needed to know to lay a single 80km line.

A few months later, Spivey called him again to ask if Williams would be willing to oversee the laying of a 50-mile fiber optic line from Cleveland. “I didn’t know what I was getting into,” Williams admits, as Spivey didn’t tell him anything beyond what he needed to know to lay a single 80km line.

Between two calls to Williams, Spivey persuaded Jim Barksdale, former CEO of Netscape Communications and fellow Jacksonian, to fund Spivey's estimated $300 million worth of construction of the tunnel. The partners named the newly formed company Spread Networks and disguised the nature of its activities by setting up front companies with unremarkable names like Northeastern ITS and Job 8. communities and districts to lay a line through their territory. Williams was so good at laying the line that Spivey and Barksdale called him and asked him to take over the entire project. He recalls, "That's when they told me, 'Well, now we have to get her to New Jersey.'"

Leaving Chicago, the brigades moved rapidly through Indiana and Ohio. On good days, builders could lay 3–5 km of cable into the ground. When they got to the west of Pennsylvania, they ran into rocks and the progress slowed down, sometimes up to hundreds of meters a week. “It’s what’s called bluish stone, or hard limestone,” says Williams. “Breaking through it is not easy.” He had to explain the same thing over and over again to Pennsylvania construction crews. “I convinced them that we need to lay a cable through another mountain, and over and over again they said:“ This is crazy. And I explained again: "I know it's crazy, but that's how we need to do it." Then they asked: “What is it for?”, and I answered: “This specialized line is being laid taking into account the wishes of the customer.” They only had to say something: “Ah ...”

On good days, builders could lay 3–5 km of cable into the ground. When they got to the west of Pennsylvania, they ran into rocks and the progress slowed down, sometimes up to hundreds of meters a week. “It’s what’s called bluish stone, or hard limestone,” says Williams. “Breaking through it is not easy.” He had to explain the same thing over and over again to Pennsylvania construction crews. “I convinced them that we need to lay a cable through another mountain, and over and over again they said:“ This is crazy. And I explained again: "I know it's crazy, but that's how we need to do it." Then they asked: “What is it for?”, and I answered: “This specialized line is being laid taking into account the wishes of the customer.” They only had to say something: “Ah ...”

Another problem for Williams was Spivey, who did not give him a descent for the slightest deviation from the route. For example, it often happened that the right-of-way crossed from one side of the road to the other and, accordingly, the line had to remain within it when crossing the road. These constant crossings annoyed Spivey as Williams would turn the cable right or left at a sharp angle. “Steve, you’re taking a hundred nanoseconds from me,” Spivey protested. (A nanosecond is equal to one billionth of a second.) And he asked: - You can cross the road at least diagonally ?

These constant crossings annoyed Spivey as Williams would turn the cable right or left at a sharp angle. “Steve, you’re taking a hundred nanoseconds from me,” Spivey protested. (A nanosecond is equal to one billionth of a second.) And he asked: - You can cross the road at least diagonally ?

Spivey had doubts. He thought: when you take a risk and things don't work out, it's because you've overlooked something, and he's thinking up things that he usually doesn't think about. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange could have gone out of business and moved to New Jersey. The Calumet River could prove to be an insurmountable obstacle. Some wealthy company—a big investment bank or telecom operator—could find out what he was doing and do the same for themselves. It was the fear that someone had already undertaken to lay his own direct route that literally pursued him. Every builder Spivey spoke to thought he was crazy, and he was sure there were people working on the sly in the Alleghans who were obsessed with the same idea. “When something becomes obvious to you,” he explains, “then you immediately begin to imagine that someone else must have realized it.”

“When something becomes obvious to you,” he explains, “then you immediately begin to imagine that someone else must have realized it.”

Only one thing did not occur to him - what if Wall Street does not want to buy the laid line? On the contrary, he expected that there would be a rush demand for it. Perhaps for this reason, neither he nor his partners thought much about how they would sell it until the time came for this. And it wasn't easy at all. The subject of their trade - the speed of data transfer - was of value only because of its scarcity. But they did not know exactly how much it was missing in order for it to acquire the maximum market value. How much was an individual player in the US stock market willing to pay to gain a speed advantage over other players? How much were 25 different players willing to pay to get the same advantage over the rest of the market? To answer such questions, it would not hurt to find out how much traders can earn in the US stock market due to only the speed of data exchange and how. “No one understood this market,” Spivey recalls, “everything was like a fog.”

“No one understood this market,” Spivey recalls, “everything was like a fog.”

The partners planned to have a Dutch (reverse) auction, i.e. start with a high starting price and lower it until a single Wall Street company buys the line and becomes a monopolist. However, they were not sure that there would be a single bank or hedge fund that could fork out the many billions of dollars that the partners considered a fair price for holding this monopoly, and they did not want the inevitable headlines in such a case to read: "Barksdale made billions from the sale of a conventional American investment company." The partners hired as a consultant Larry Tabb, who had come to the attention of Jim Barksdale with his "Cost of a Millisecond" study. Tabb proposed that the cost of accessing the line be based on the amount that could be earned from the line by engaging in so-called spread trades—playing on the price difference between New York and Chicago using a simple arbitrage that brings cash and futures prices together. Tabb calculated that if a Wall Street bank exploited the myriad, if tiny, price discrepancies between good A in Chicago and good A in New York, it could make $20 billion a year. He also calculated that about 400 companies are ready to compete for these billions. All of them needed the fastest line of communication between two cities, but there would be room on it for only two hundred.

Tabb calculated that if a Wall Street bank exploited the myriad, if tiny, price discrepancies between good A in Chicago and good A in New York, it could make $20 billion a year. He also calculated that about 400 companies are ready to compete for these billions. All of them needed the fastest line of communication between two cities, but there would be room on it for only two hundred.

These calculations happily coincided with Spivey's opinion based on his sense of the market, and he said with obvious pleasure: "We have two hundred shovels for four hundred diggers." But what price should you ask for one shovel? “We were trying to figure out which way the wind was blowing,” says Brennan Carley. Since he worked closely with many high frequency traders, Spivey hired him to sell the line to them. “We were just guessing.” The partners offered a payment of $300,000 per month, about 10 times the price for using the then existing communication lines. The first 200 stock market players willing to pay up front and sign a five-year deal were to close a deal for $10. 6 million. lines. The total upfront payment for line access for each of the 200 traders would have been approximately $14 million, for a total of $2.8 billion.

6 million. lines. The total upfront payment for line access for each of the 200 traders would have been approximately $14 million, for a total of $2.8 billion.

It's 2010 and Spread Networks still hasn't notified potential customers of its existence. A year after the start of the laying of the line, although it is hard to believe, no one knew. The partners decided to wait three months to sell the line until March 2010, to shock everyone with its significance and to minimize the chances that someone would want to repeat their project or even claim it. But how to start negotiations with the rich and powerful people whose business they were going to undermine? “In general, we acted as follows: we looked for a person we knew in one of these companies,” says Brennan Carley, “and told him:“ You know me. And heard about Jim Barksdale. So, we would like to meet with you and talk about something. But we can not say anything before the meeting. And by the way, we want you to sign a non-disclosure agreement before we come to your firm. ”

”

That's how they got into Wall Street - by stealth. “Every meeting was attended by the CEOs of the companies,” Spivey recalls. The people they met were among the highest paid professionals in the financial market. The first reaction of most of them was complete disbelief. “Subsequently, they told me about what they initially decided to themselves: “Of course, we will refuse, but we still need to listen to him.” Anticipating their skepticism, Spivey brought with him a map about a meter by two in size and ran his finger along it, showing his tunnel going straight. But people demanded proof. And although it was impossible to see the fiber optic cable laid at a depth of almost one meter underground, but the amplifiers were placed in very visible concrete bunkers with an area of about 100 m2 each. Light weakens as it moves away from its source, and the weaker it is, the worse its ability to transmit data. The light signal sent from Chicago to New Jersey needed to be amplified every 80-120 km, so Spread built ultra-secure bunkers along the line to house the amplifiers.

Book "English-Russian Explanatory Dictionary" Kaul M R

- Books

- Fiction

- non-fiction

- Children's literature

- Literature in foreign languages

- Travels. Hobby. Leisure

- art books

- Biographies. Memoirs. Publicism

- Comics.

Manga. Graphic novels

Manga. Graphic novels - Magazines

- Print on demand

- Autographed books

- Books as a gift

- Moscow recommends

-

The authors • Series • Publishers • Genre

- Electronic books

- Russian classics

- detectives

- Economy

- Magazines

- Benefits

- Story

- Politics

- Biographies and memoirs

- Publicism

- Audiobooks

- Electronic audiobooks

- CDs

- Collector's editions

- Foreign prose and poetry

- Russian prose and poetry

- Children's literature

- Story

- Art

- encyclopedias

- Cooking.

Winemaking

Winemaking - Religion, theology

- All topics

- antique books

- Children's literature

- Collected works

- Art

- History of Russia until 1917

- Fiction. foreign

- Fiction.