Can first graders read

How To Help 1st Grader Read Fluently

When our children are first learning to read, we want them to be successful. As a parent, you are likely to try to find out how to help 1st grader read better. By first grade, kids are learning to read full-length books and are able to read longer, more complex sentences.

This means that your child is reading at a more challenging level and might be struggling. Their reading fluency is likely a factor in how well they are understanding a text.

What should a 1st grader be able to read?

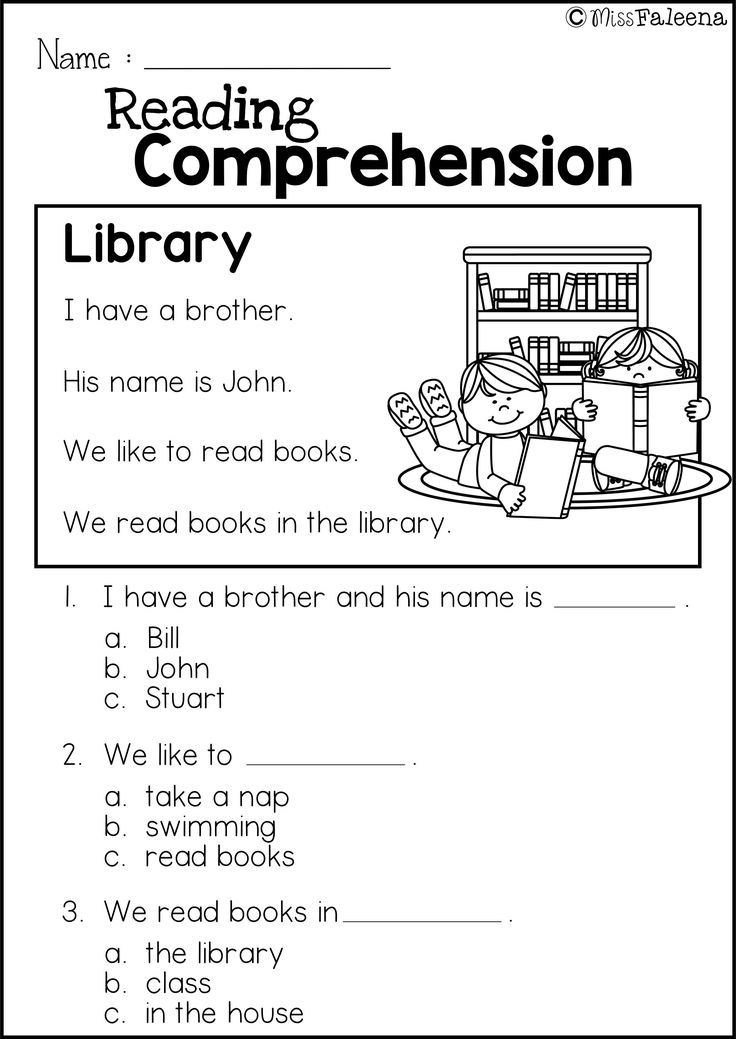

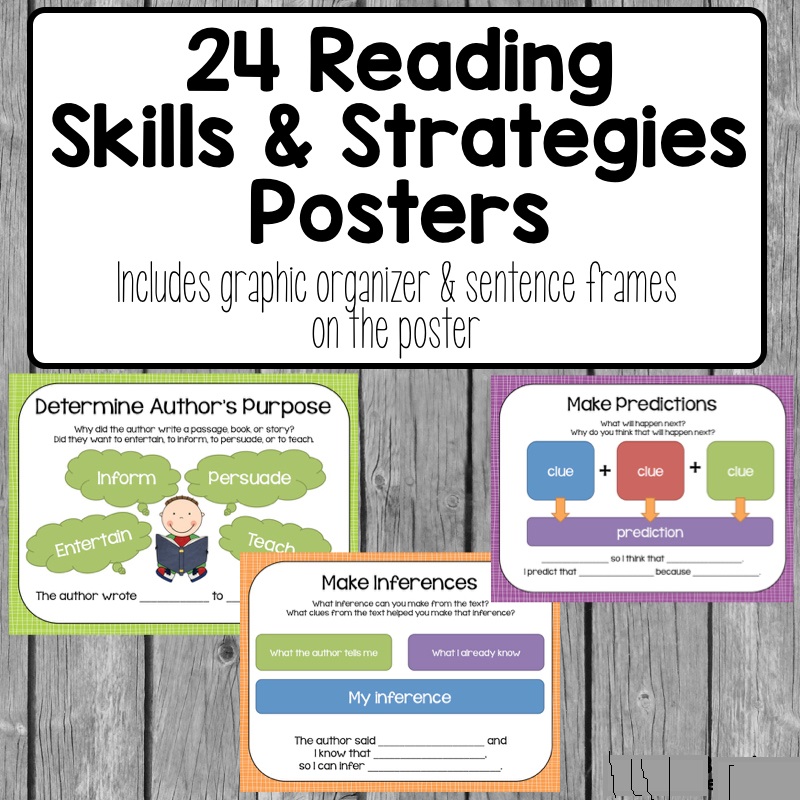

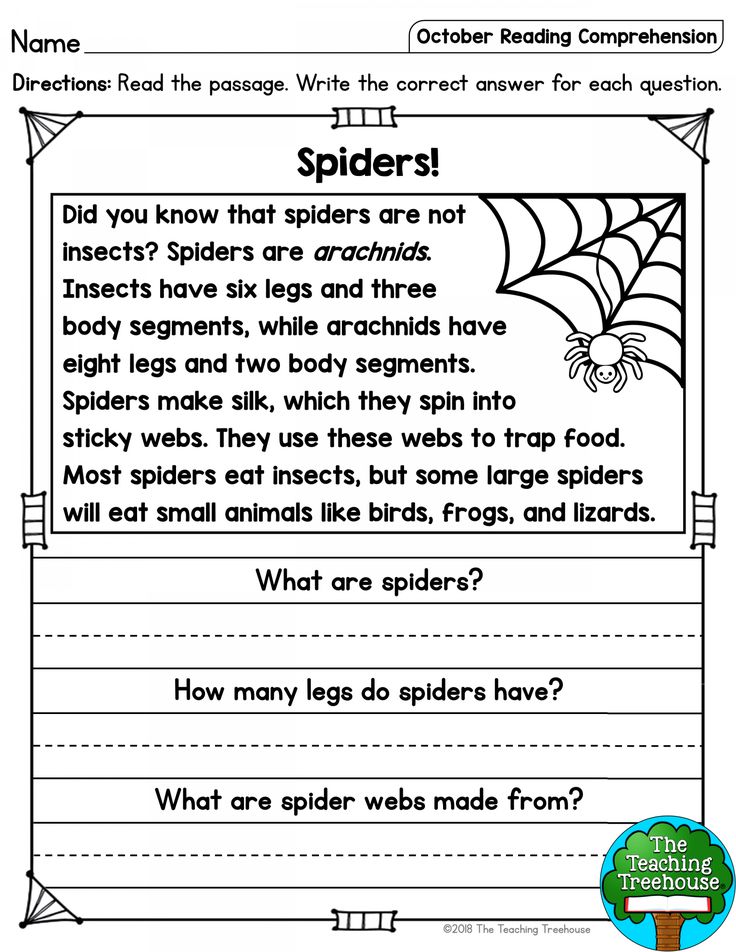

By 1st grade your child should have at least the following variety of reading skills:

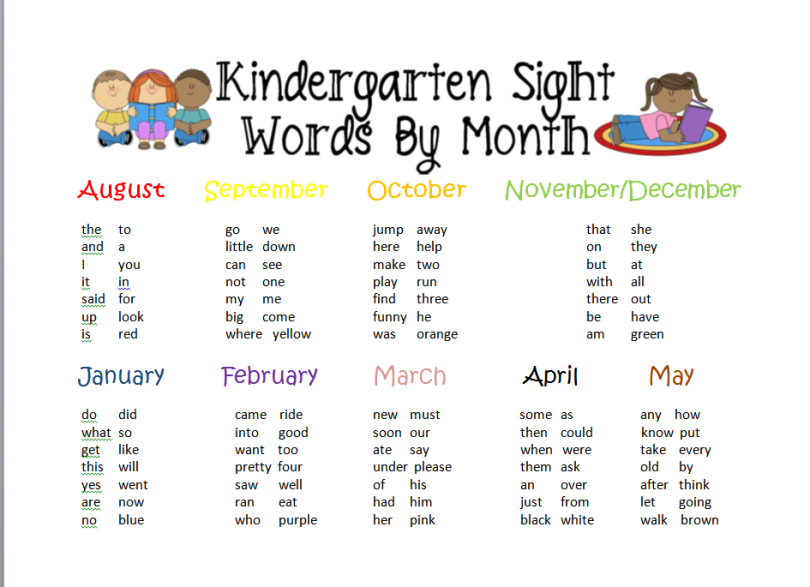

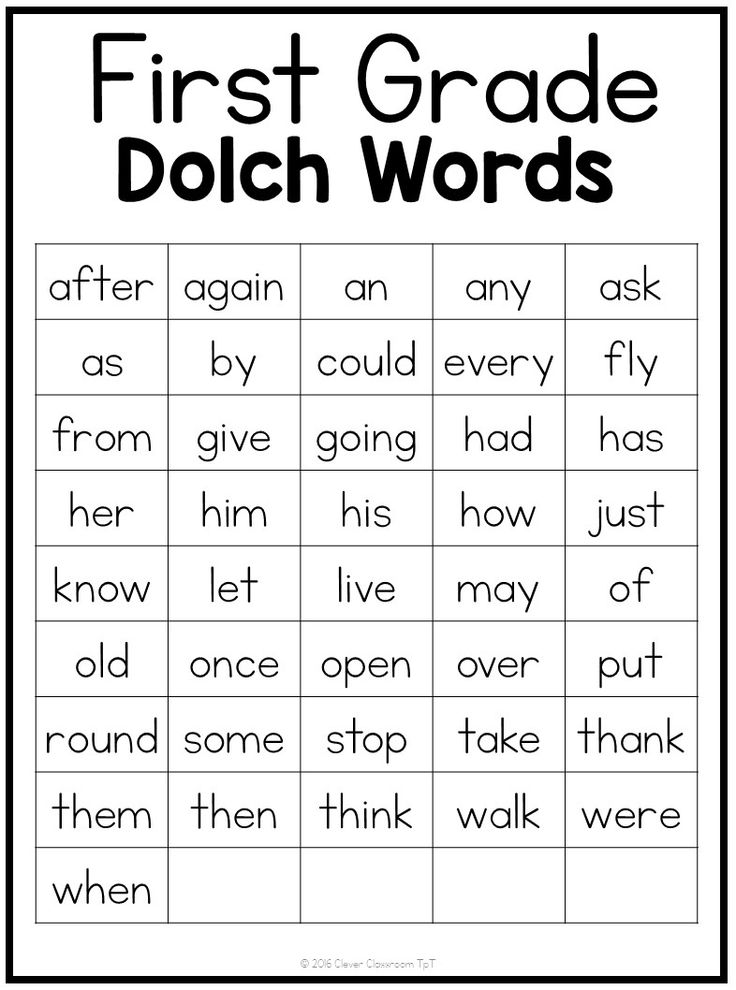

- They should be able to recognize about 150 sight words or high-frequency words.

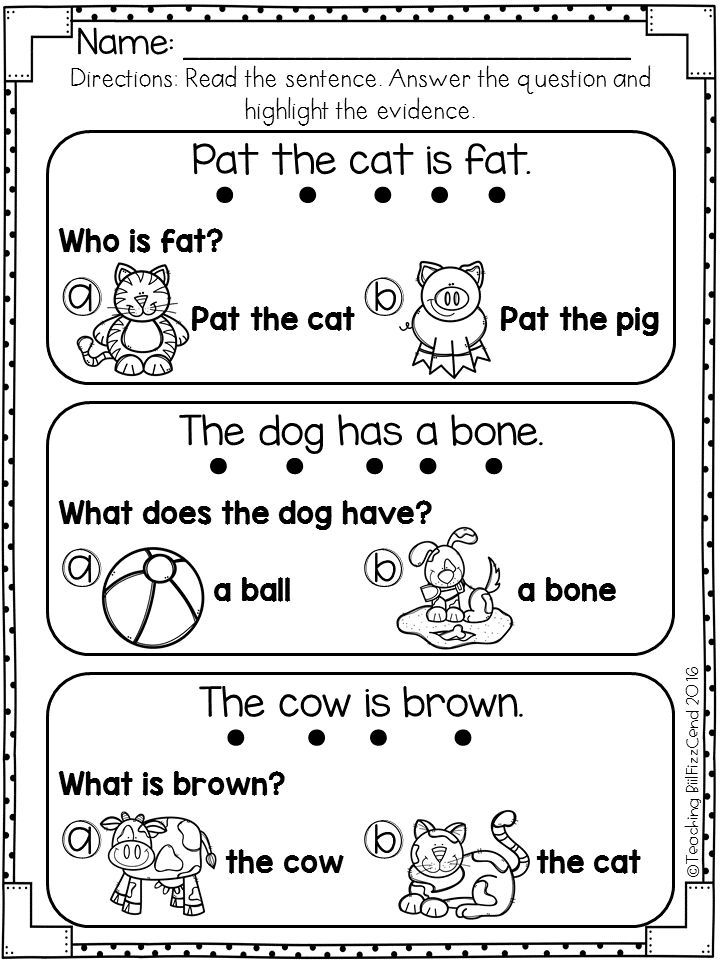

- They are able to distinguish between fiction and nonfiction texts.

- They should be able to recognize the parts of a sentence such as the first word, capitalization, and punctuation.

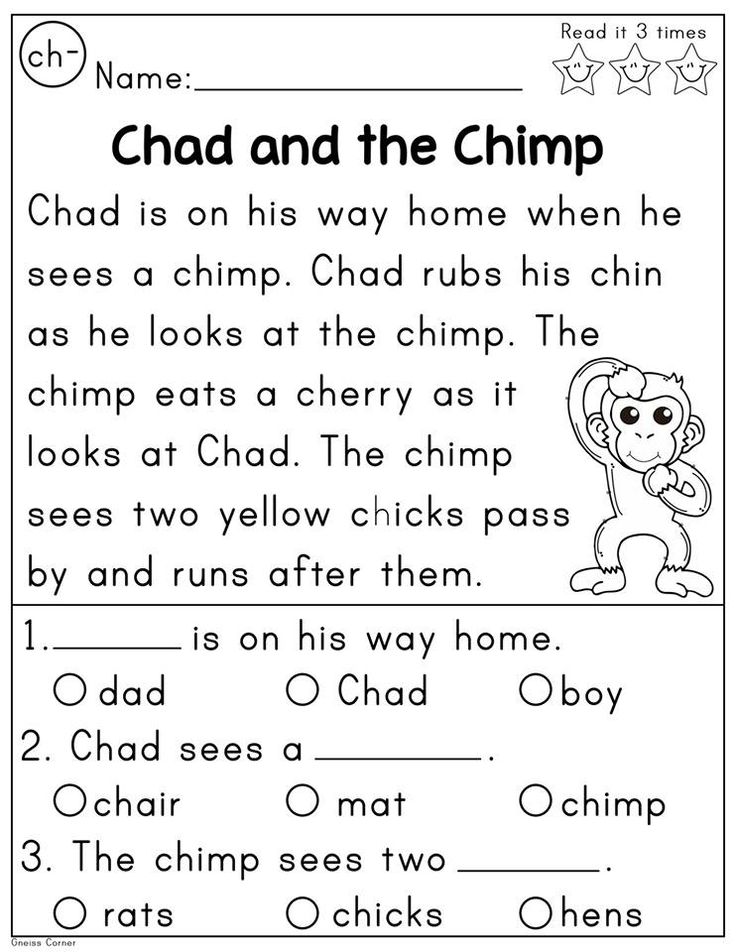

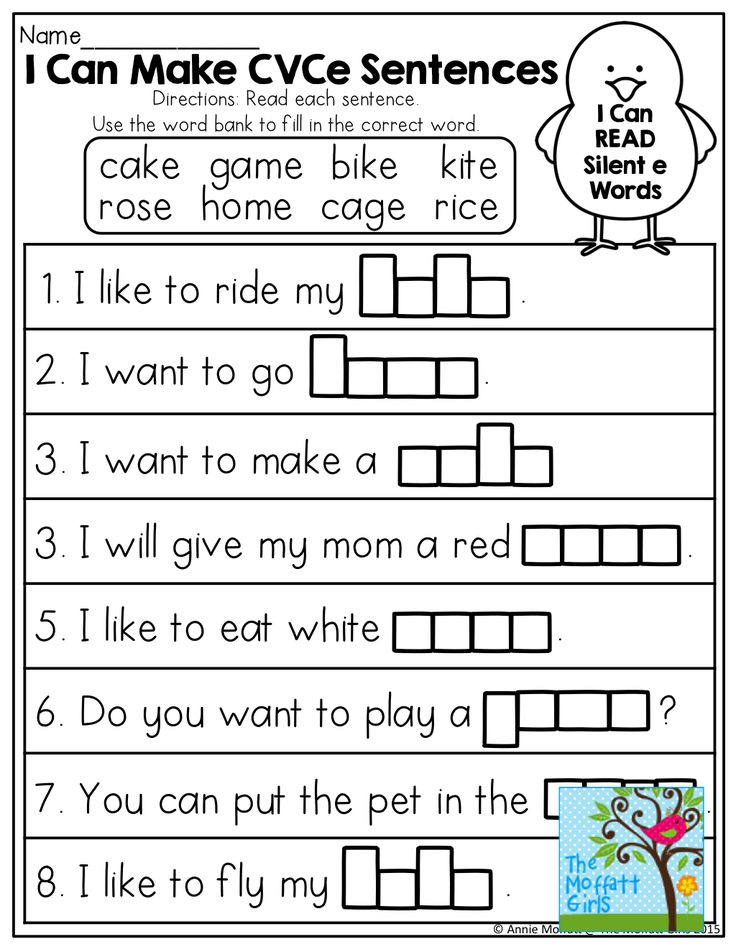

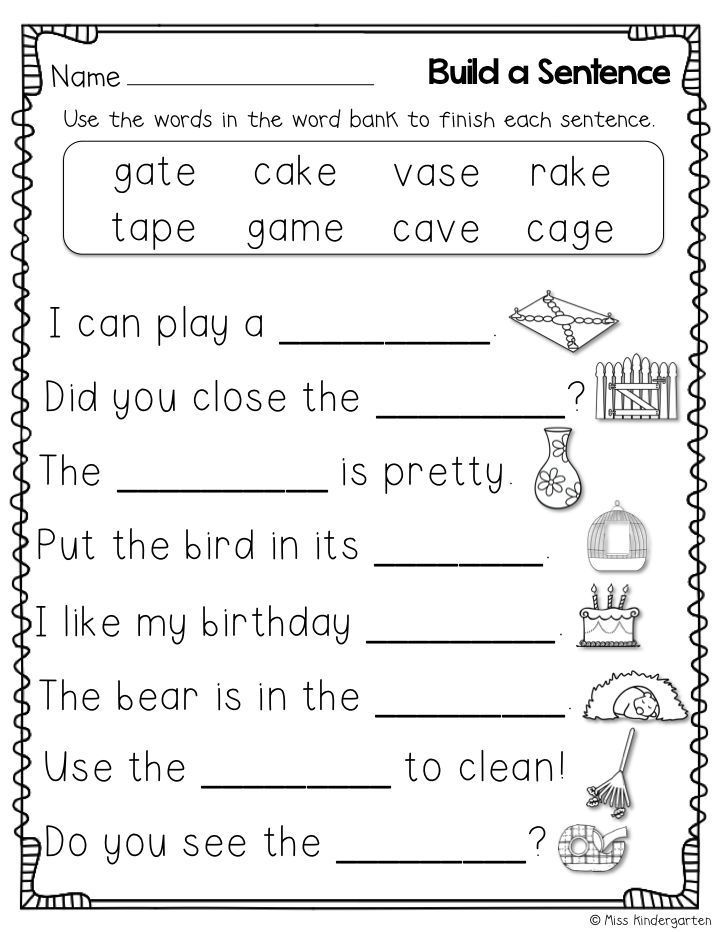

- They are able to understand how a final “e” will change the sound of the vowels within a word.

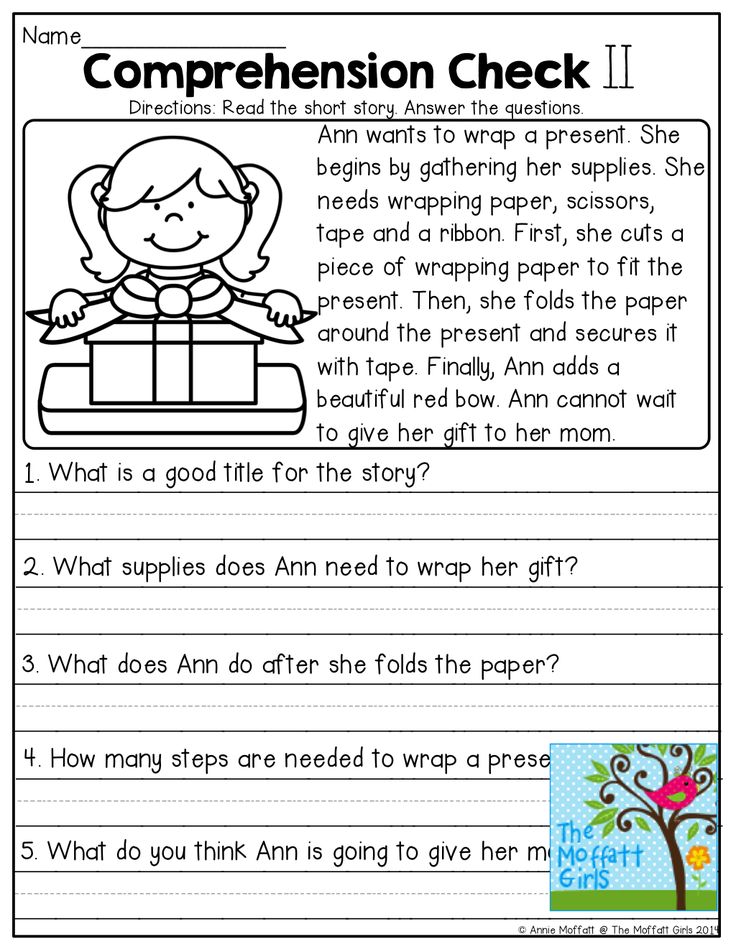

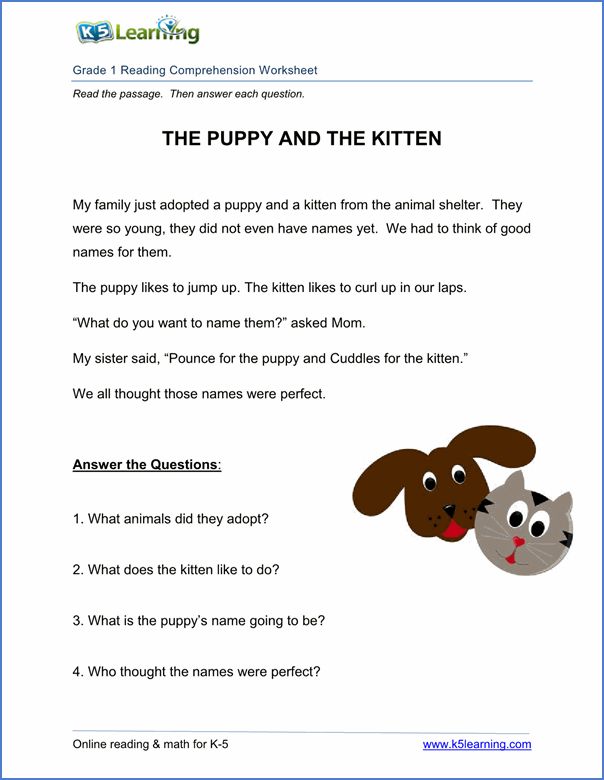

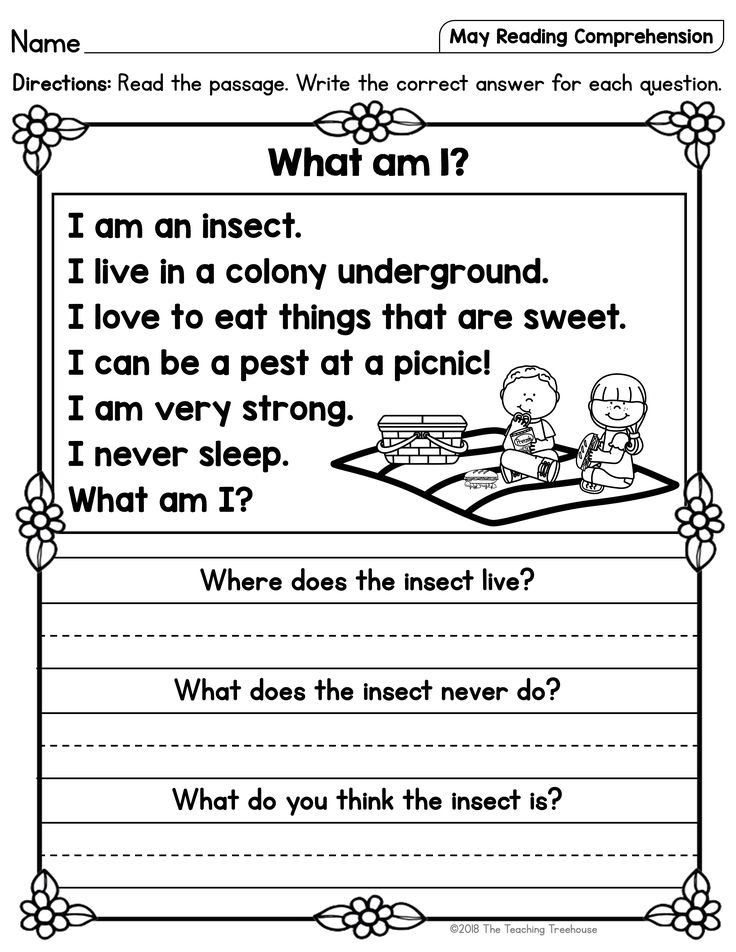

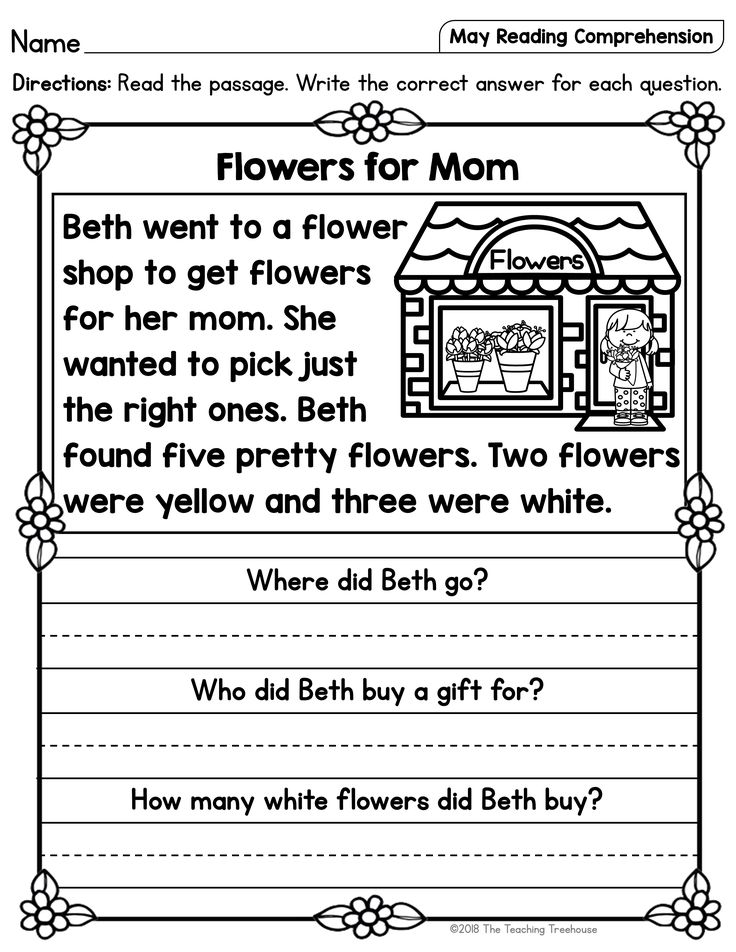

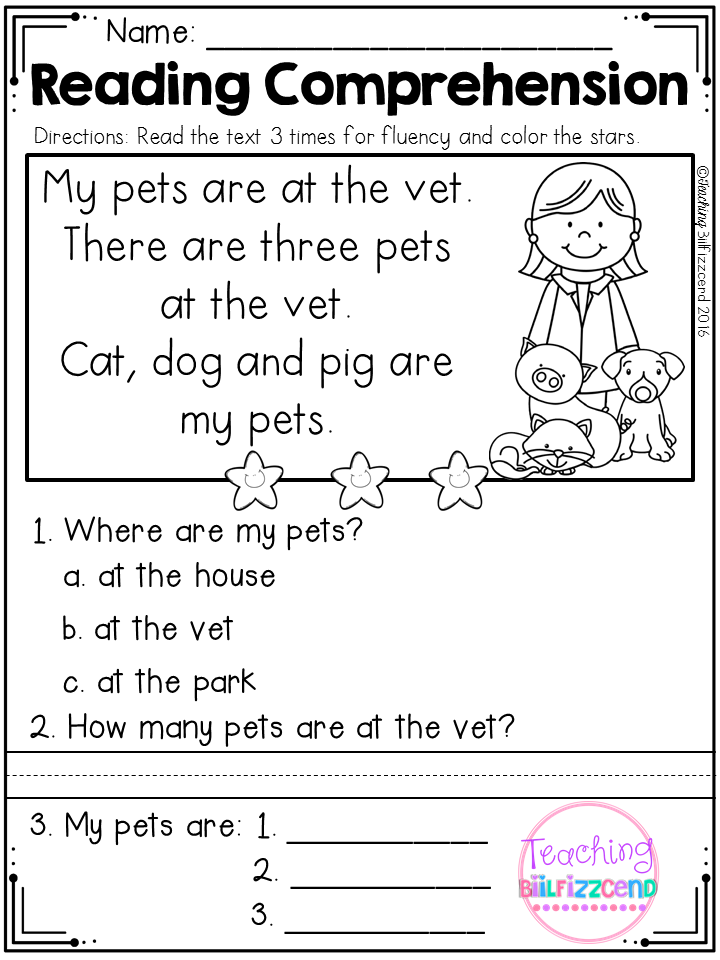

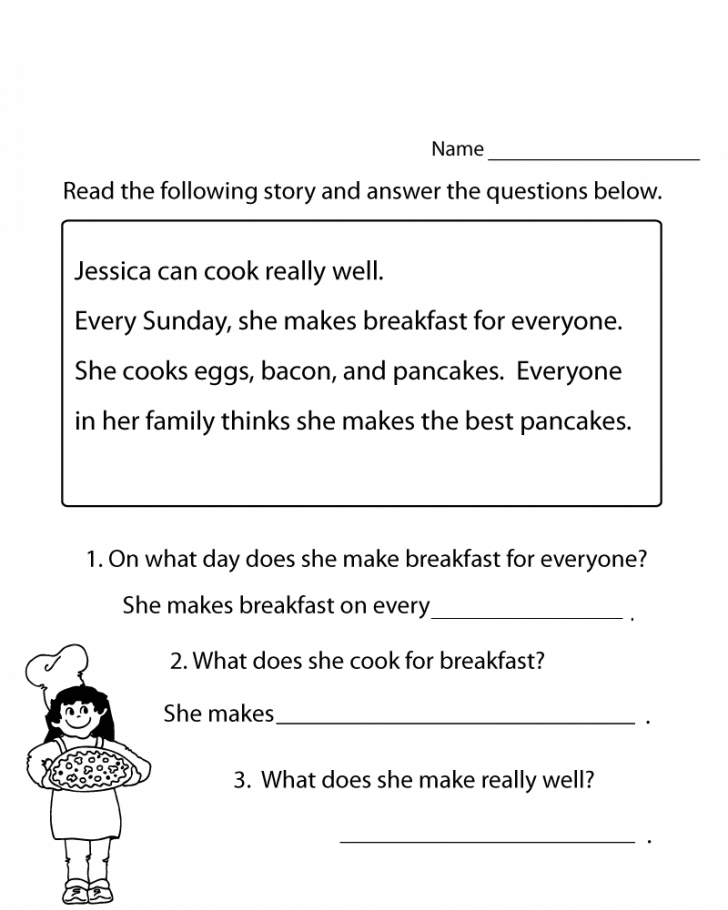

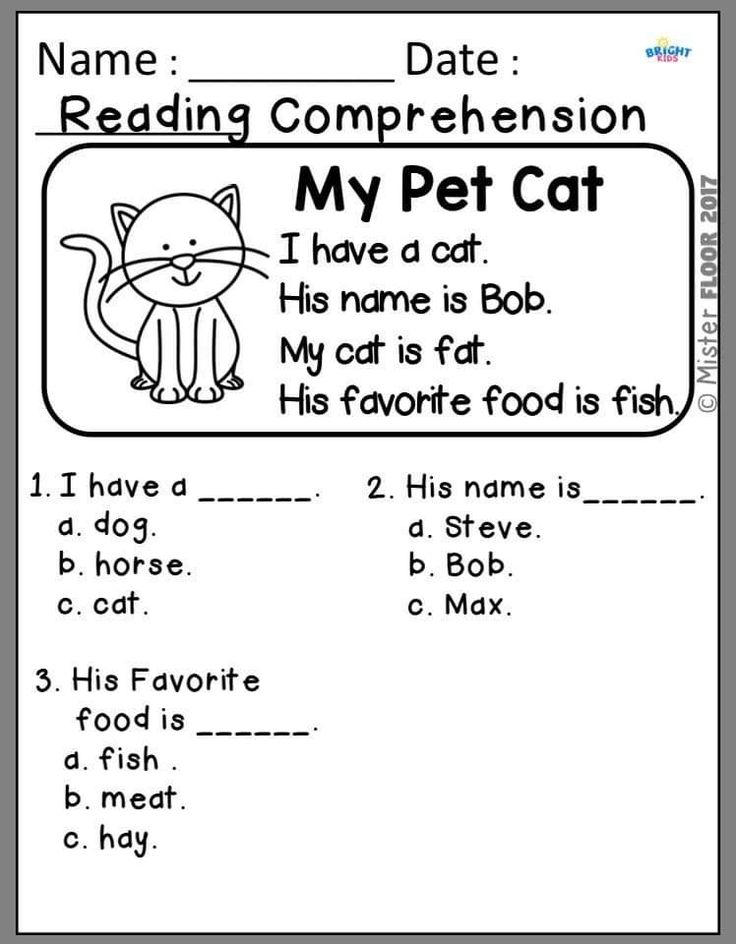

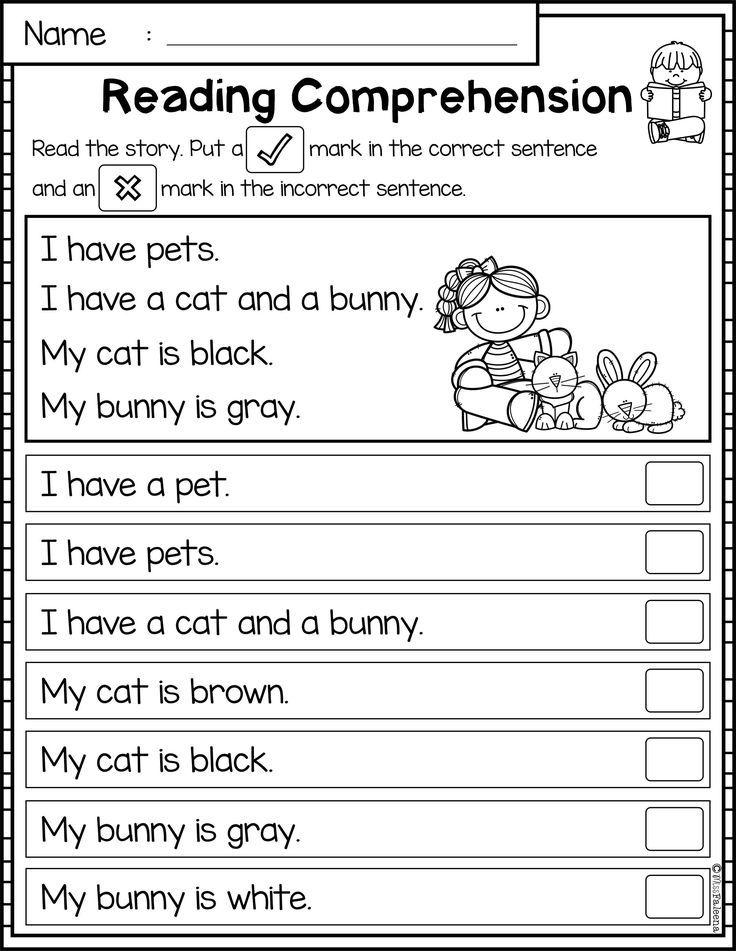

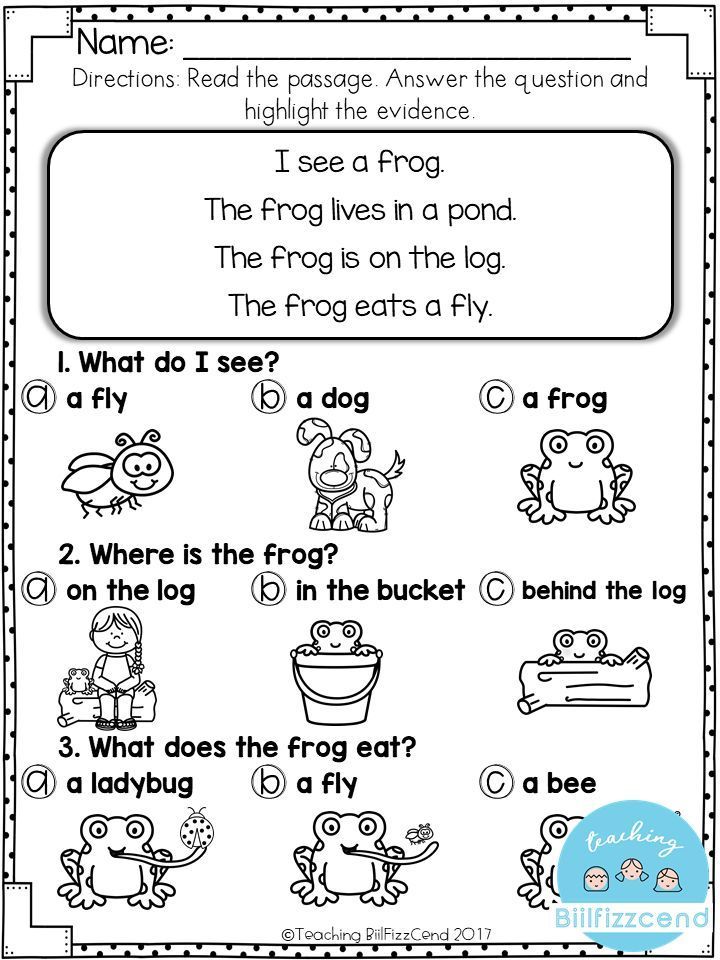

- They are able to answer questions and recall details from a reading.

- They are able to read fluently meaning with speed, accuracy, and prosody.

Your first grader should be able to begin reading the first few levels of graded reader books. A graded reader book is a book that is set at a certain reading level. These books are often used in schools to help measure student progress.

What is fluency in reading?

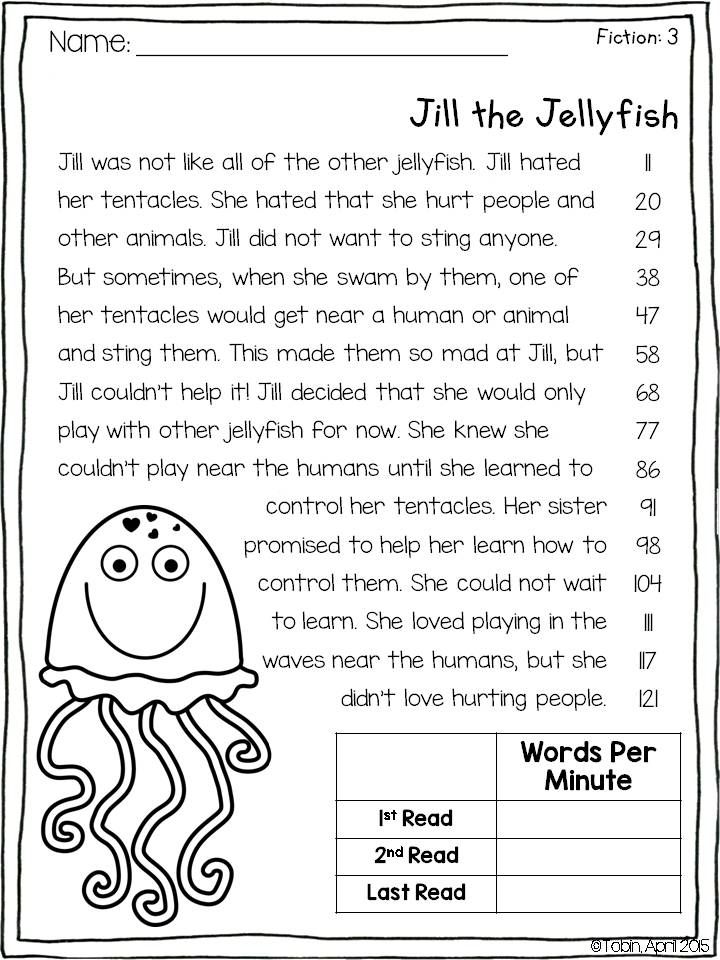

Reading fluency is the ability to “read how you speak”. This means that your child is reading at a conversational pace with appropriate expression. Reading fluency is important because it is directly related to reading comprehension. The more fluent a reader is the better they understand the text.

Fluency in reading relies on speed, accuracy, and prosody. These factors make for a fluent reader and help your 1st grader not only to recognize words but to actually understand and comprehend text.

- Speed – Fluent readers read at a speed that is accurate for their grade level which is 60 words per minute for 1st graders.

- Accuracy – Fluent readers are able to recognize words quickly and have the skills to sound out and decode words they are unfamiliar with.

- Prosody – Fluent readers use expression and intonation to bring meaning into their readings. This is not just recognizing words, but also recognizing that expression also plays a part in understanding.

How can I help my 1st grader with reading fluency?

There are a variety of things you can do at home to help your 1st grader read more fluently:

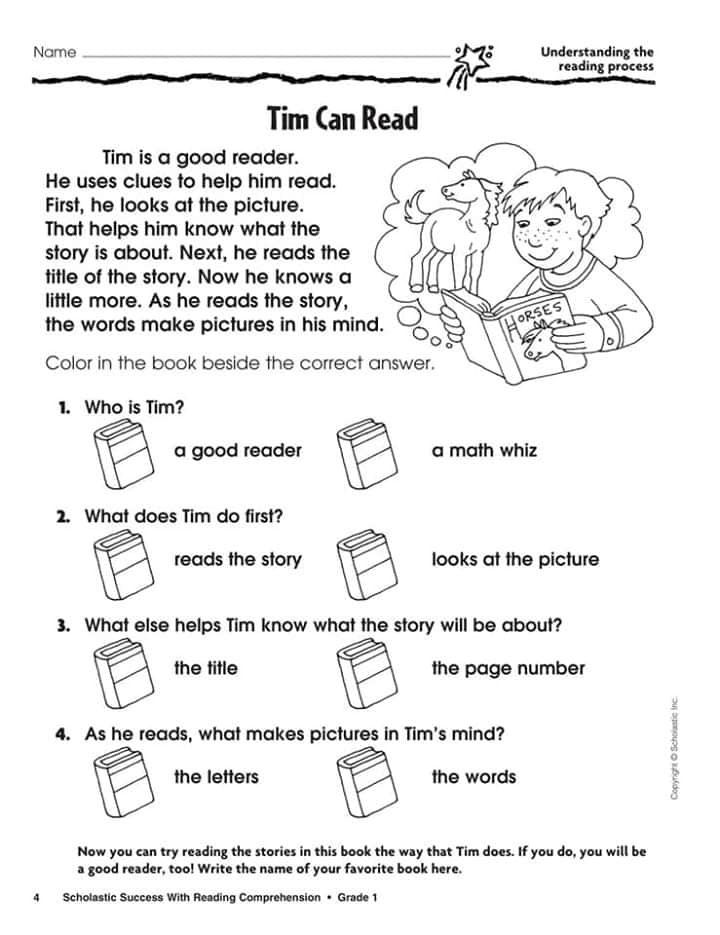

- Model reading – Children learn best when they have a model showing them the skills they are meant to be learning. Reading to your child regularly provides a model of fluent reading for them.

- Echo Reading – As you and your child read a text, read one sentence then have them read the same sentence out loud. This form of repeated reading helps them see you model fluency then lets them practice it.

- Reader’s theatre – Turn a book into a script and have

your kids bring the story to life.

This will help them practice their expression and intonation when they read.

This will help them practice their expression and intonation when they read. - Practice sight words – The more words your child recognizes, the more fluent they will become. Use word games and flashcards to help them learn sight words to help them read less choppy.

- Extensive reading – The best way to help your 1st grader to read fluently is to get them to read a lot! Provide lots of books of their choice at home and get them to enjoy reading so that they practice often.

- Utilize reading apps – Most kids play with technology already such as tablets and smartphones. Why not incorporate reading into this game time by downloading some reading apps?

Which reading app is helpful for improving fluency?

Readability is an app that helps improve fluency for emerging readers. The app is a great way to increase fluency for your 1st grader because it uses A.I. technology and speech-recognition to recognize errors your child might be making when reading out loud.

Readability provides a large library of original content that your child can read and is constantly being updated with new stories. The app works like a private tutor by actually listening to your child read out loud and recognizing their errors. It then provides feedback to help them improve. It can also read the material to your child as they follow along.

These forms of repeated reading can help your 1st grader practice their fluency wherever and whenever they want. Try Readability for free!

First grade is critical for reading skills, but some kids are way behind

AUSTIN, Texas — Most years, by the third week of first grade, Heather Miller is working with her class on writing the beginning, middle and end of simple words. This year, she had to backtrack — all the way to the letter “H.”

This story also appeared in USA Today“Do we start at the bottom or do we start at the top?” Miller asked as she stood in front of her class at Doss Elementary.

“Top!” chorused a few voices.

“When I do an H, I do a straight line down, another straight line down and then I cross in the middle,” Miller said, demonstrating on a projector in a front corner of the classroom.

Her 25 students set to work on their own. Some got it right away. One student watched his tablemate before slowly copying down his own H’s. Another tested her own way of writing the letter: one line down, cross in the middle, then another line down. “Your paper is upside down, let’s turn it,” Miller said to a student who was trying to write letters while leaning sideways, almost out of her seat.

A student works on a writing assignment in Heather Miller’s classroom.In classrooms across the country, the first months of school this fall have laid bare what many in education feared: Students are way behind in skills they should have mastered already.

Children in early elementary school have had their most formative first few years of education disrupted by the pandemic, years when they learn basic math and reading skills and important social-emotional skills, like how to get along with peers and follow routines in a classroom.

While experts say it’s likely these students will catch up in many skills, the stakes are especially high around literacy. Research shows if children are struggling to read at the end of first grade, they are likely to still be struggling as fourth graders. And in many states with third grade reading “gates” in place, students could be at risk of getting held back if they haven’t caught up within a few years.

40 percent — The number of first grade students “well below grade level” in reading in 2020, compared with 27 percent in 2019, according to Amplify Education Inc.

First grade in particular — “the reading year,” as Miller calls it — is pivotal for elementary students, when their literacy skills “really take off.” Kindergarten focuses on easing children from a variety of educational backgrounds — or none at all — into formal schooling. In contrast, first grade concentrates on moving students from pre-reading skills and simple math, like counting, to more complex skills, like reading and writing sentences and adding and subtracting numbers.

By the end of first grade in Texas, students are expected to be able to mentally add or subtract 10 from any given two-digit number, retell stories using key details and write narratives that sequence events. The benchmarks are similar to those used in the more than 40 states that, along with the District of Columbia, adopted the national Common Core standards a decade ago.

Teachers often see a range of literacy skills, and that could be more pronounced this year due to the pandemic

Teacher Heather Miller has seen a wide range of writing skills among her first grade students, with some students already writing complex sentences while others are still working on letter formation. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller has already seen improvement in writing, including among students who started the year without a strong grasp of forming letters. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger Report

Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger Report“They really grow as readers in first grade, and writers,” Miller said. “It’s where they build their confidence in their fluency.”

But about half of Miller’s class of first graders at Doss Elementary, a spacious, bright, newly built school in northwest Austin, spent kindergarten online. Some were among the tens of thousands of children who sat out kindergarten entirely last year.

More than a month into this school year, Miller found she was spending extensive time on social lessons she used to teach in kindergarten, like sharing and problem-solving. She stopped class repeatedly to mediate disagreements. Finally, she resorted to an activity she used to use in kindergarten: role-playing social scenarios, like what to do if someone accidentally trips you.

“My kids are so spread out in their needs … there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.

Heather Miller, first grade teacher”

“So many kids are missing that piece from last year because they were, you know, virtual or on an iPad for most of the time, and they don’t know how to problem-solve with each other,” Miller said. “That’s just caused a lot of disruption during the school day.”

Her students were also not as independent as they had been in previous years. Used to working on tablets or laptops for much of their day, many of these students were also behind in fine motor skills, struggling to use scissors and still working on correctly writing numbers.

Related: What parents need to know about the research on how kids learn to read

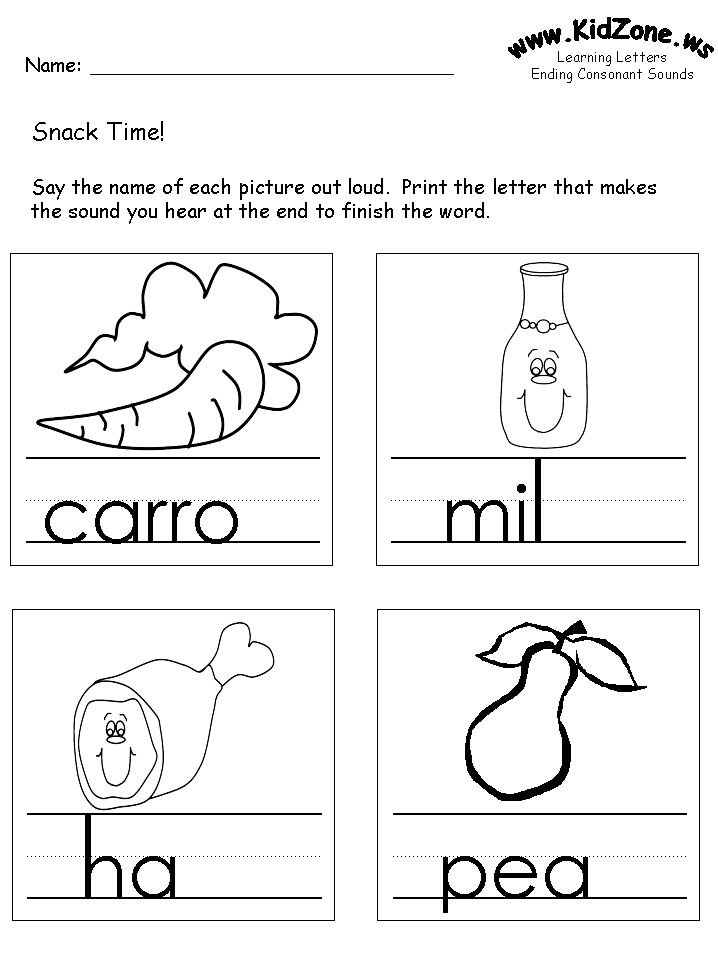

Instead of working on first grade standards, Miller was devoting time on this Friday morning in early September to forming upper- and lowercase letters, a kindergarten standard in Texas and the majority of other states. As students finished practicing the letter H, they moved on to the assignment at the bottom of the page: Draw a picture and write a word describing something that starts with an H.

“H-r-o-s” one student wrote next to a picture of a horse standing on green grass in front of a light blue sky. “H-e-a-r-s” another student wrote next to a picture of a strip of brown hair, floating in the white picture box. “You should draw a face there,” suggested his tablemate, pointing at the blank space under the hair.

Students work on a phonics activity during center time in Heather Miller’s classroom. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportMiller’s first graders are a case study in the scale, depth and unevenness of learning loss during the pandemic. One report by Amplify Education Inc., which creates curriculum, assessment and intervention products, found children in first and second grade experienced dramatic drops in grade level reading scores compared with those in previous years.

In 2020, 40 percent of first grade students and 35 percent of second grade students were scoring “well below grade level” on a reading assessment, compared with 27 percent and 29 percent the previous year. That means a school would need to offer “intensive intervention” to nearly 50 percent more students than before the pandemic.

That means a school would need to offer “intensive intervention” to nearly 50 percent more students than before the pandemic.

Data analyzed by McKinsey & Company late last year concluded that children have lost at least one and a half months of reading. Other data show low-income, Black and Latinx students are falling further behind than their white peers, leading to worsening achievement gaps.

Experts say it’s now clear families who had time and resources to help their children with academics when schooling was disrupted had a tremendous advantage.

“Higher-income parents, higher-educated parents, are likely to have worked with their children to teach them to read and basic numbers, and some of those really basic early foundational skills that kids generally get in pre-K, kindergarten and first grade,” said Melissa Clearfield, a professor of psychology who focuses on young children and poverty at Whitman College.

“Families who were not able to, either because their parents were essential workers or children whose parents are significantly low-income or not educated, they’re going to be really far behind. ”

”

What Miller has observed in the first few weeks of the school year is likely taking place in classrooms nationwide, experts say. In April, researchers with the nonprofit NWEA, which develops pre-K-12 assessments, predicted how the pandemic’s disruptions would manifest among the kindergarten class of 2021: a wider range of ability levels; large class sizes with more diverse ages because some parents held children back a grade; and students unfamiliar with in-person classroom routines.

“We predicted that there would be a lot of diversity in skills,” said Brooke Mabry, strategic content design coordinator for NWEA Professional Learning. That includes skills related to academics, social-emotional learning and executive functioning, she added.

The varying experiences children had with school last year also impacted fine motor skill development, independence, ability to navigate conflicts and the “unfinished learning” teachers are now observing, she added.

Related: Remote learning a bust? Some families consider having their child repeat kindergarten

While switching to remote learning was hard on many students, younger students were generally unable to log themselves on to a computer independently and focus on virtual lessons for extended periods of time. Teachers, who usually rely on small, in-person groups for early literacy skills, instead had to teach letters, sounds and sight words via online platforms.

Miller had the unwieldy task of teaching kids both in person and online, spending her year pivoting between students in front of her and students on her computer screen, using her projector to display books to students at home and teaching reading skills via virtual groups.

Now, with students in front of her again, Miller was finding that those online lessons weren’t as useful as many had hoped.

Miller, 30, is a calm, confident teacher who is in her eighth year of teaching and her second at Doss. She usually has students with a wide range of ability levels at the beginning of the year, although Doss is relatively affluent. Nearly 62 percent of students at the school are white, and fewer than 20 percent are economically disadvantaged, compared with the district average of nearly 53 percent. In 2019, 95 percent of Doss’ students passed the state reading assessment.

Students play outside Doss Elementary in Austin, Texas. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportBut this year, Miller saw larger gaps in reading skills than ever before. Usually, her first graders would start with reading levels ranging from mid-kindergarten to second grade. This year, the levels spanned early kindergarten up to fourth grade.

“My kids are so spread out in their needs,” Miller said. “I just feel like — and I’m sure every teacher feels like this — there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.”

“I just feel like — and I’m sure every teacher feels like this — there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.”

She’s also seen higher literacy levels for kids who went to school in person last year. To her, it speaks to the immense benefits kids get from all aspects of in-person learning. “It just shows how important it is for these kids to be around their peers and just have normalcy,” she said.

Related: Summer school programs race to help students most in danger of falling behind

To catch kids up, Miller is relying on, among other things, one of the staples of the early elementary classroom: center time. For two hours a day, she works with small groups of students on the specific math and reading skills they are lacking.

On a recent October morning, Miller divided her class into five groups to rotate through various activities around her room. She gave her students a few minutes to finish a writing assignment as she pulled out several sets of small books at various reading levels; colorful plastic, hollow phones so her students could hear themselves read; and for a group of struggling readers, a matching game featuring cards showing various letters and pictures.

“I feel like I’m teaching four grades,” Miller said as she arranged the materials on her desk.

Several minutes later, seated at a table in the back of the room with five of her grade-level readers, Miller handed them each a phone, a small book and a green witch’s finger to help them point at the words in the book. “Today we’re going to talk about our reading tools,” Miller said, holding up a blue plastic phone. “These are called whisper phones. You whisper so you can hear yourself sound out the words,” she said. “Do these go on our heads?”

“No!” the students said, giggling.

“You know what these are for?” she said, holding up a rubber finger.

“Um, they’re for reading,” one student said. “’Cause I had them in kindergarten.”

“Very good. Are these for picking your nose?” Miller asked.

“No!” the students said, laughing.

She placed a book in front of each child and walked them through a series of exercises, including looking at the cover and predicting what the book would be about.

Then, they opened their books and began to read in a whisper. Miller turned from one side of the table to the other, listening as students read to themselves, pointing at each word with their green rubber fingers. She helped them sound out challenging words, like “away.” One by one, the students finished the book. A few read it several times in the minutes allotted.

Students practice reading using whisper phones during center time in their first grade classroom. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportMiller’s next group, all of whom were reading far below grade level, required a different activity. Rather than handing out a book, Miller pulled out a letter-matching game at the table, using materials she had from her days as a kindergarten teacher. She placed two small laminated cards on the table, one showing the letter D and a picture of a dog, and one with the letter B and a picture of a ball.

“We’re going to do your letters today,” Miller said to the group. “What letter is this?” she asked, pointing to the B.

“Ball!” one student responded.

“What letter?” Miller asked again. There was a pause.

“B!” another student responded.

“What sound does it make?”

“Buh,” a third student said.

The students ran through the activity, looking at pictures of items starting with B and D like a doll, ball, dog and dolphin, and sorting them into piles based on the starting letter.

A student reads a book during center time in Heather Miller’s classroom. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportExperts like Clearfield say finding new or different strategies to help students learn grade-level content after the last 18 months will be critical, even if that means pulling out activities typically used by lower grade levels, as Miller did with her lowest reading group.

It also may mean recruiting help from outside the classroom. Miller said Doss already had a strong team of interventionists to rely on, and several of her students receive extra reading help during the day.

Miller has also found it helpful to work with her fellow first grade teachers to solve a shared academic challenge. This fall, the first grade teachers all discovered that many of their students were behind in reading sight words. They began meeting regularly to share tips and strategies to combat this.

Despite the obvious need to catch kids up, Miller has been mindful of not coming on too strong with remediation efforts. “I don’t want to push them so hard where they get burned out,” she said on an October evening. “They’ve been through so much.”

Related: We know how to help young children cope with the trauma of the last year— but will we do it?

Mabry, of NWEA, said while catching students up is important, society needs to view the recovery process as a multiyear effort. “In previous years, when looking at unfinished learning and finding ways to get students to accelerated growth, we never expected that we would get students who need support to meet those accelerated goals in one year. We would never approach it that way,” Mabry said. “Now, we’re so frantic. I think we’re frantic because we feel it’s this larger population.”

We would never approach it that way,” Mabry said. “Now, we’re so frantic. I think we’re frantic because we feel it’s this larger population.”

It’s a daunting task, but experts say there is hope.

“Kids will catch up eventually,” said Clearfield from Whitman College. But to get there, society may need to re-evaluate expectations, she added. “If most children in our community are behind by, like, a year or two, then our expectations for what is typical, it’s going to have to match where they are,” Clearfield said. “Otherwise, we are going to be constantly frustrated … we’re going to have expectations that don’t match their skills or abilities.”

By mid-autumn, Miller was heartened by what she was seeing in her classroom. Students were becoming more confident and independent. Their writing was stronger. There were fewer conflicts.

There were fewer conflicts.

One morning, Miller stood by her desk as students effortlessly transitioned from one activity to the next during center time. They quietly buzzed around, cleaning up activities and putting their notebooks away in cubbies as she prepared to work with a new group of students at her desk.

“It kind of gives me hope that we’ll be OK,” she said. “Even after last year, we’ll be OK.”

This story about reading skills was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

How many words per minute a first-grader should read

Children come to the first grade with very different skill levels. Someone already fluently reads whole stories, the other can barely read a line by syllables. Many parents diligently teach their children to read before school. And it is no accident: despite the fact that there are no official requirements for reading standards for a child entering school, testing a child for reading speed in the first grade will begin at the end of the first half of the year. According to the indicative norms of the Federal State Educational Standard, a first-grader should read 25-30 words per minute in the first half of the year and 30-40 in the second. Note that the norms are indicative, so gymnasiums, for example, can raise the bar higher, and correctional schools, on the contrary, lower it a little. Here are some tips on how to make learning to read effective and comfortable for you and your child.

Don't chase reading speed

That's right. After all, if you train a child precisely on the speed of pronunciation of words, then he will be able to learn how to quickly read the text, but he will not understand what he read. Don't do your child a disservice. School performance is, of course, important, but not only the praise of the teacher is at stake, but also the development of the child. Therefore, when teaching a child to read, pay attention to the semantic content of the text, discuss with him the characters, their words and deeds, together recall the events of previously read books. Speed will be gained gradually, thanks to constant practice and several useful exercises.

Choose the right literature

It is better to start learning to read with books "by age", well illustrated, with large letters and not too long words - consisting of two or three syllables. In addition, it is important that all the words in the book are familiar to the child.

Do not overdo it

Do not start learning to read too early, experts advise not to do this before the age of 5, because the child's body during this period absorbs all the impressions of the surrounding world, but is not yet ready to perceive the text. But he will be happy to listen to your reading and from an early age he will perceive a book in his hands as something obviously fascinating. Do not force a child to read, do not turn the joy of reading into a duty. Try not to intimidate him with upcoming checks, otherwise interest will instantly turn into a routine. Learning to read for a child is a lot of work. If the child is tired, there is nothing wrong with you reading aloud to him.

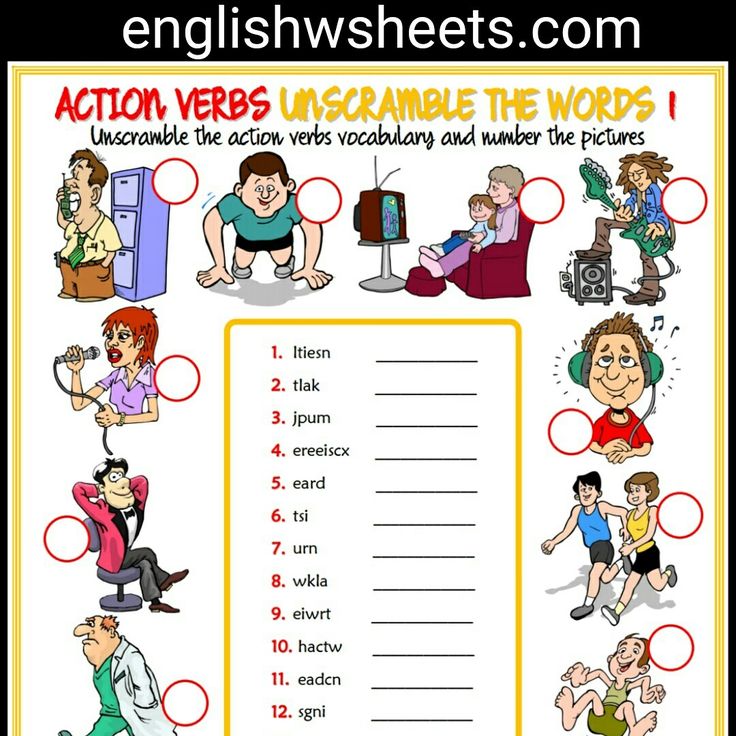

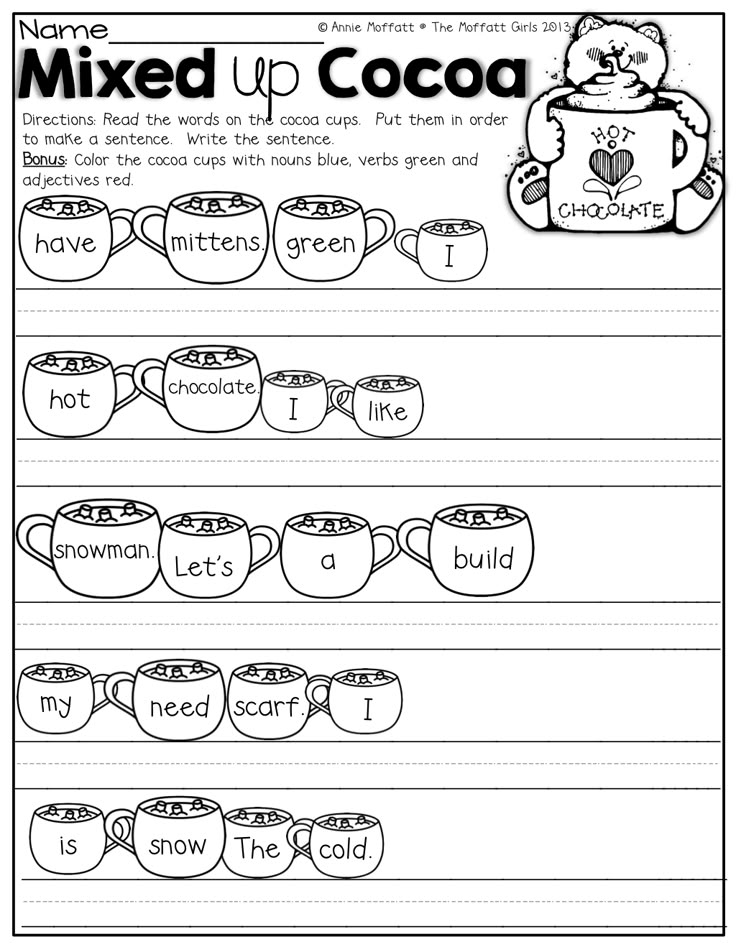

Learn by playing

You can collect words from cubes with spellings written on them. You can guess cards with inscriptions and drawings. Or read stories in which some words are replaced by pictures. In any case, the process of reading at first should include something else besides reading itself. A game element that will support the interest of the child and will not let him run out of steam at the very beginning of learning.

A game element that will support the interest of the child and will not let him run out of steam at the very beginning of learning.

Game exercises for developing reading speed

If your child has already learned to read whole words and combine them into sentences, it's time to think about developing reading speed.

Play animals with him: try to imagine and show how a horse gallops, how a horse speaks and how a horse reads? How does a turtle work? And the tiger?

Try to read by roles on behalf of different characters in the story. Surely they will have not only different timbres, but also different pronunciation speeds.

Read with the child in turn and gradually increase the pace of reading your piece, the child, in turn, will repeat after you and will learn to read faster.

Following the tips above will help your child read as many words per minute as a grade 1 student should on the first test, without losing the meaning of what they read and without losing interest in the book.

Should a child be able to read in first grade

Should a child be able to read in first grade? This question is of great interest to parents whose child goes to school. Note that even a little skillful child provides much less trouble for the teacher during the lesson. In this article, you can find the answer to your question and understand what principles you need to adhere to while preparing for the first grade. The child must be prepared for school long before entering it.

Table of contents:

- First grade reading level

- Reasons for slow reading

- Helpful Tips for Parents of First Graders

- How to captivate a child while reading?

First grade reading level

A child's seven years of age is the best age for entering first grade. In elementary grades, reading lessons are provided to improve reading skills. The student must be able to read with expression and without errors, the ideal barrier is 30 words per minute. Be sure to pay attention to how the child sets the stress in the words being read. You should also force the child to think about what is being read, so that after reading he can easily retell the text.

Be sure to pay attention to how the child sets the stress in the words being read. You should also force the child to think about what is being read, so that after reading he can easily retell the text.

Reasons for slow reading

A child should be able to read in the first grade more or less normally so that the teacher can pay attention to all children equally. After all, if your child does not have any reading skills, he may demand more attention from the teacher, thereby taking time from the teacher and other students. You should also be prepared for the fact that the teacher will give your child more home exercises to improve reading technique:

- a weak level of RAM, that is, the child may forget the text he has read every three or four words. Consequently, the child does not grasp the whole essence of the story;

- lack of concentration, as well as weak perseverance;

- no additional reading. The more time a child devotes to reading, the better he will read;

- weak volume of the operational field of view;

- no interest in reading.

Many parents are interested in ways to teach their children to read and to develop a love of books, but unfortunately they cannot find a clear answer. To find a more suitable approach to your child, you need to take a closer look at him, as well as take into account all his hobbies. After all, you can teach a child something through a game or his favorite hobby. You will definitely find an approach to your chacha and will be interested in reading.

It should be noted that a child can be able to read in the first grade due to the constant replenishment of vocabulary. So that the child does not have problems with reading at school, you need to pay attention to the activities with the child two or three years before entering school. From a very early age, you need to talk as much as possible so that the child's vocabulary increases. Communication should take place on a variety of topics. The child should answer all the questions posed by him, and this should be done with restraint and more informatively. It is through communication that the child receives a lot of interesting and useful information for him, which can be useful to him in the ability to read in the first grade.

It is through communication that the child receives a lot of interesting and useful information for him, which can be useful to him in the ability to read in the first grade.

There is such a thing as regression. This is the case when the child's eyes constantly return to the word already read, namely to the one that he liked the most. In this aspect, it is necessary to emphasize the development of mindfulness.

It is also imperative to pay due attention to the development of diction, because if there are problems with it, they must be urgently exterminated, otherwise the child will constantly have problems not only with reading, but also in conversation. To reduce the level of poor diction, it is necessary to work hard on expression and reading speed.

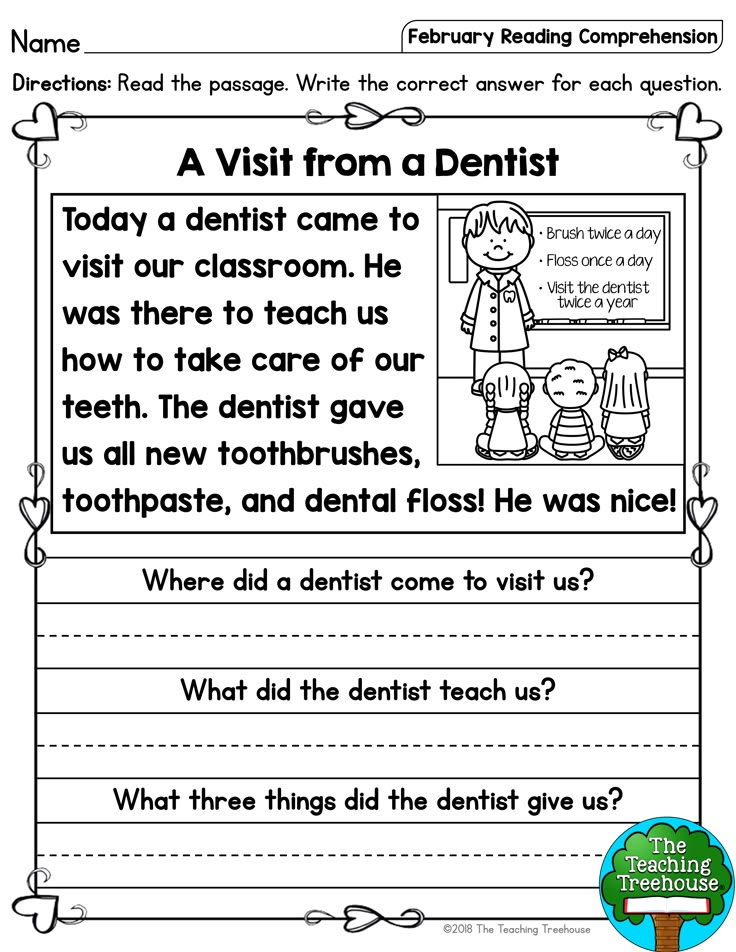

Helpful tips for parents of first-graders

How to teach your child in the first grade to read at a sufficient speed? To solve this issue, you need to find a problem that interferes with fast reading and excellent diction.

If reading tests at school show that your child reads rather slowly, then you should be patient. First of all, here are a few tips to help you and your child solve their reading problem:

- Regular reading in my spare time. You may not notice any shifts and improvements in your reading technique if you spend little time in class. You should not interrupt your studies even during holidays and at the end of the school year.

- You need to have the right mood and set a goal. You need to perceive this activity as something exciting, in which case the child will understand that it is very interesting and will be much more willing to do it.

- Literary works should be selected for the child, which are presented with colorful pictures.

- Reading is possible not only within the walls of the house, but also while walking in the park or in the clinic.

- Be sure to take into account the nature of the child. If your child is a fidget in ordinary life, then it is quite difficult to persuade him and lure him into a calm activity - reading.

He will be very often distracted, but it’s absolutely not worth scolding for this, since in the future he can do you out of spite and refuse to study.

He will be very often distracted, but it’s absolutely not worth scolding for this, since in the future he can do you out of spite and refuse to study. - Try to make the lesson in a playful way. And also first independently study the material that you plan to offer the baby.

- Pay attention not only to the speed of reading, but also to whether the child understands the very meaning of the material.

Your child will be able to read in the first grade if all of the above rules are followed.

How to captivate a child while reading?

In order for a child to be able to read in the first grade, it is necessary to start preparing in advance. To entice the baby with interesting reading, you need to come up with interesting options for him. For example, you can offer a future first grader to read a book to his favorite toy. While reading, you can put his favorite toy or doll near the baby, so that he, in turn, “entertains” her with an interesting book. Let the child introduce himself as a teacher, so it will be much more interesting and exciting for him.

Let the child introduce himself as a teacher, so it will be much more interesting and exciting for him.

It should be noted that a small child needs to be able to read in the first grade, and for this it is necessary to give small and colorful texts, where the sentences are short and as clear as possible. So the child can quickly absorb all the information.

You can invite your child to read an excerpt from a book before going to bed, choosing an intriguing moment in the book in advance. Thus, he will be interested in finishing the story the next day.

In order for a child to be able to read clearly in the first grade, tongue twisters must be taught. Usually, this activity brings laughter and joy to the baby, because it's so funny when neither the parents nor the baby himself can read correctly. But require a clear pronunciation from the future student.

The child should be able to read at least a little in the first grade. This fact will significantly improve his performance, that is, it will be much easier for the baby to perceive all the information.