Challenge rhyming words

Words that rhyme with challenges

Rank 1 rhymes

| soldiers | charges | ages | messages | images |

| pages | hostages | judges | wages | languages |

| villages | bridges | savages | georges | damages |

| marriages | sausages | stages | packages | privileges |

| bandages | advantages | cages | edges | manages |

| badges | passages | cartridges | hodges | colleges |

| urges | pledges | emerges |

Rank 2 rhymes

| was | does | mm | cause | mrs |

| horses | ideas | pieces | glasses | faces |

| forces | cases | chances | wishes | circumstances |

| voices | witnesses | services | cameras | bitches |

| passes | classes | buzz | boxes | shoulders |

| promises | dishes | matches | kisses | consequences |

| ashes | taxes | asses | inches | senses |

| causes | areas | dresses | loses | surprises |

| prices | excuses | resources | expenses | watches |

| touches | races | sources | nurses | misses |

| neighbours | corpses | reaches | dances | refuses |

| experiences | whimpers | fuckers | catches | offices |

| rises | differences | missus | bosses | branches |

| bananas | bushes | losses | metres | speeches |

| traces | masses | purposes | teaches | diseases |

| crosses | sacrifices | pajamas | witches | km |

| buzzes | buses | premises | devices | pleases |

| peaches | churches | posters | tyres | sentences |

| stitches | bruises | exercises | courses | addresses |

| riches | appearances | businesses | princes | followers |

| motors | beaches | crashes | punches | increases |

| chooses | references | aces | bases | finishes |

| raises | sunglasses | suitcases | spaces | realizes |

| advances | trenches | actresses | braces | sizes |

| produces | cuz |

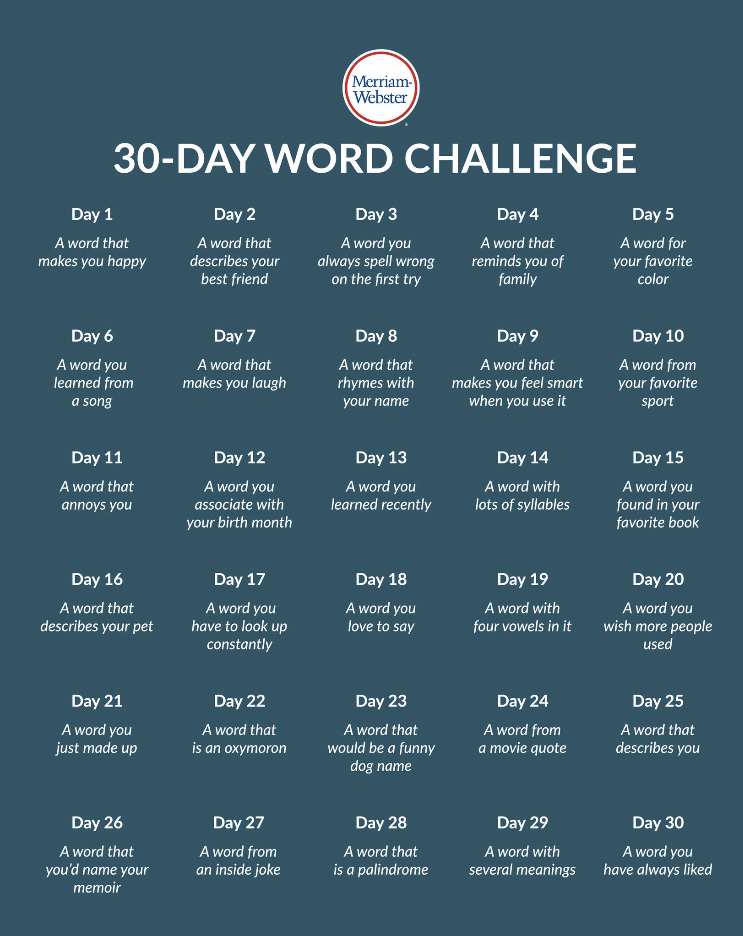

Rhyming Word Games: 7 Ways to Make Language Fun for Everyone

DESCRIPTION

students playing rhyme game

SOURCE

DaniloAndjus / E+ / Getty

PERMISSION

Used under Getty Images license

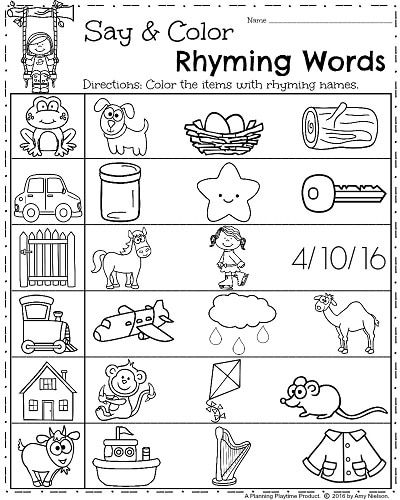

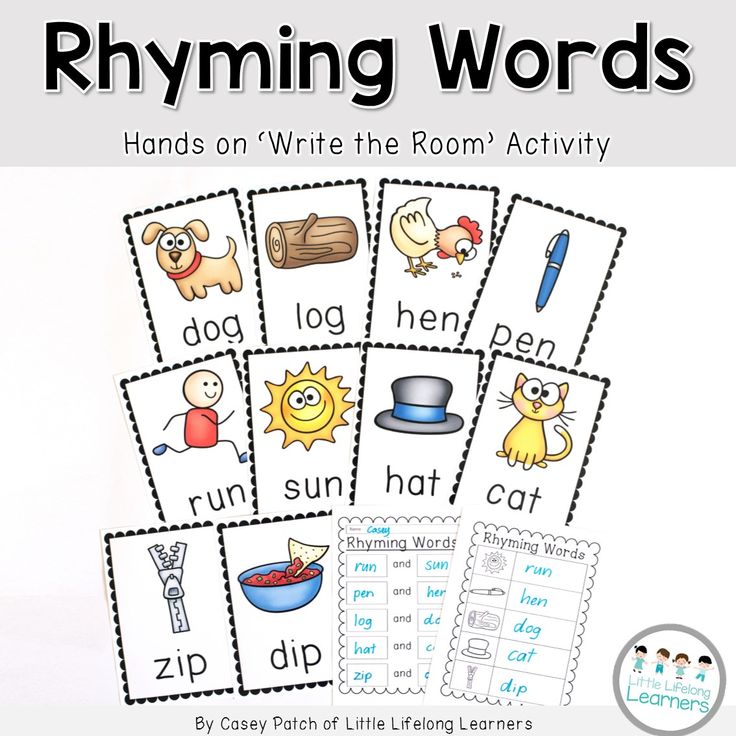

People love to rhyme, and they love to play games — so why not combine them? Rhyming word games are an excellent way to help kids better identify words and learn how to read or spell, but they also provide entertainment for all ages.

Keep reading for several examples of fun rhyming activities for kids, as well as a few rhyming games for adults.

Disappearing Rhyme Man

A good rhyming game for the classroom or a family function is Disappearing Rhyme Man, sometimes called the Invisible Rhyme Man. It's like Hangman in reverse.

- Draw two stick figures on a chalkboard, white board or large sheet of paper with between 12 and 16 body parts. This may include a head, body, legs, arms, hair, eyes, nose, mouth, and so on.

- Divide the group into two teams.

- Randomly choose a word or phrase to start the game. It should be something that can be rhymed with easily.

- The first player on the starting team tries to name a rhyming word. You can choose a time limit for this part of the game.

- If the player comes up with a correct rhyming word, they erase one part of the opposing team’s man.

- If a team cannot think of a rhyming word, either give the other team a chance or pick a new word to rhyme.

- Continue playing until one rhyme man has completely disappeared.

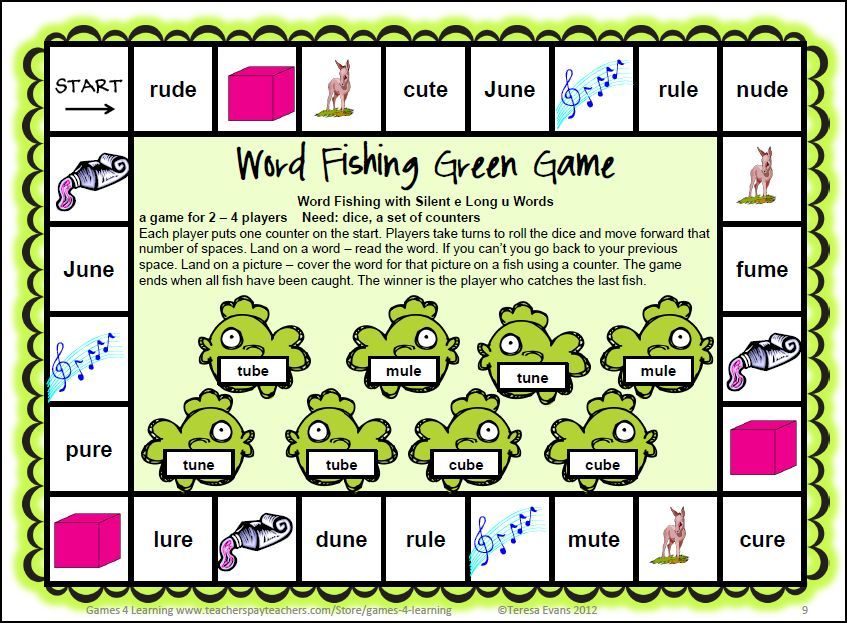

Rhyming Word Bingo

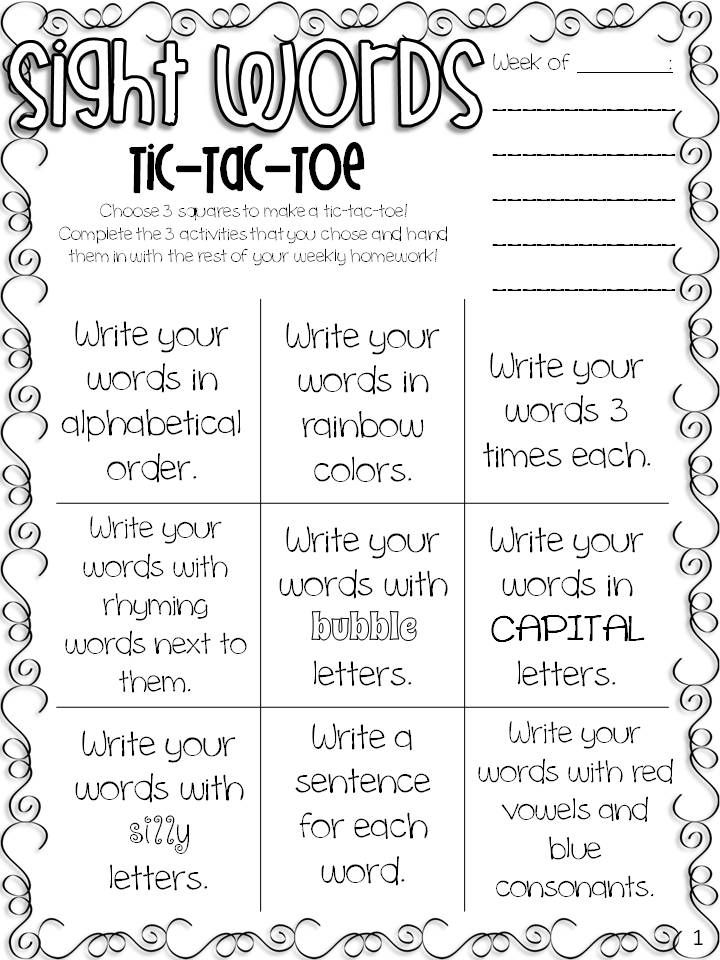

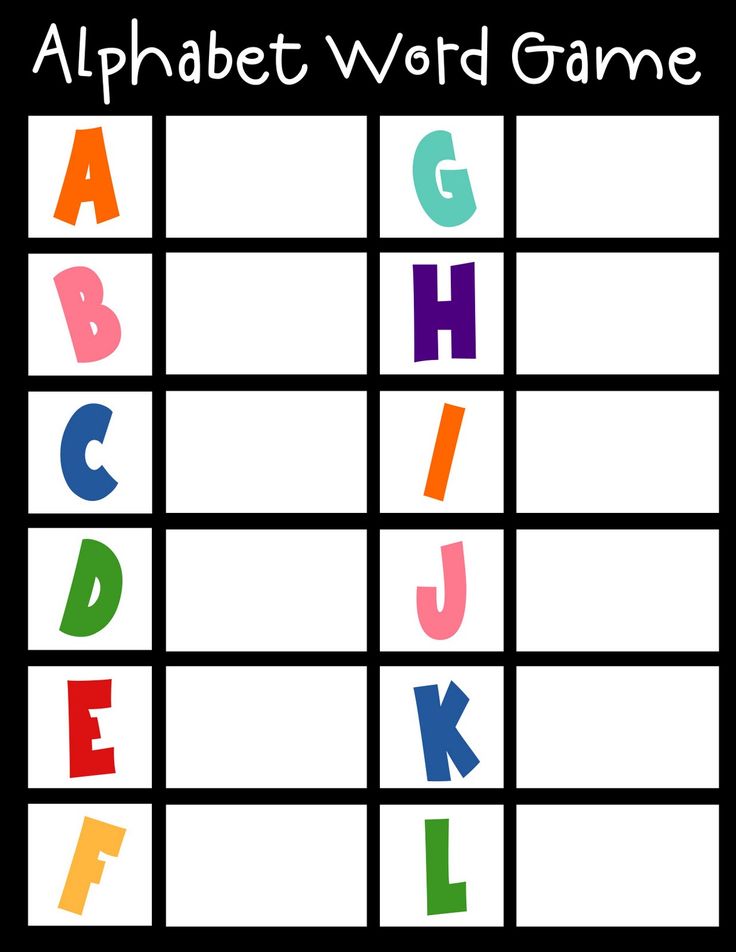

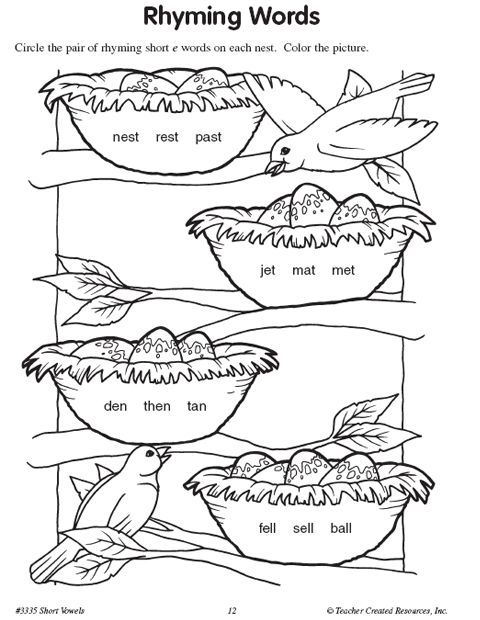

Take the classic game of Bingo and apply it to the world of rhyming word games! It's great for any level of elementary, middle or high school and any age.

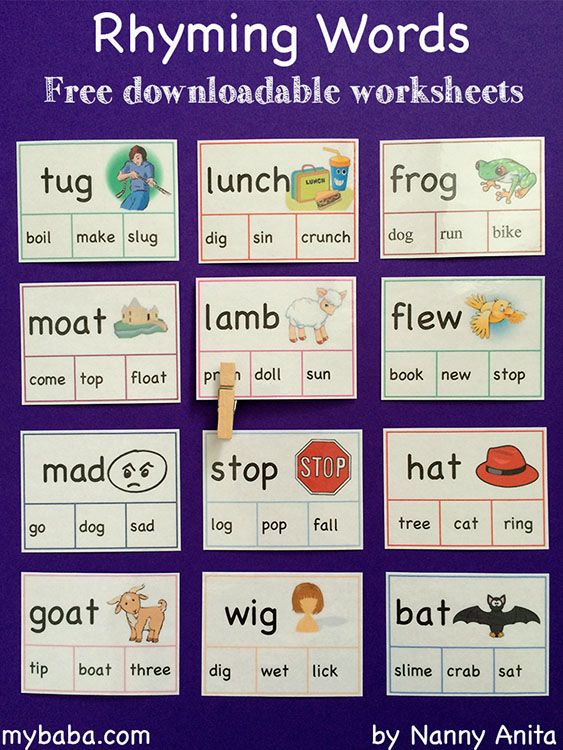

- Create the Bingo game boards and call sheet beforehand, complete with one half of a rhyming set (for example, you could add "boat" to the card, and then call out "coat"). You can add either images of items or actual words to the boards.

- Give each player or team a game board.

- Call out a word from the call sheet.

- Players look for a word on their respective game boards that rhyme with the called word. If the call word is "boat," they can match with a word on their board like "coat" or "goat."

- The first player to complete a horizontal, vertical or diagonal line wins.

- Just as with regular Bingo, the game can continue with additional patterns for winning.

The grid does not need to correspond to the standard B. I.N.G.O. structure. Each space on the board can be independent and not directly related to all the words in the same column.

I.N.G.O. structure. Each space on the board can be independent and not directly related to all the words in the same column.

Word, Word, Rhyme

This rhyming variation on the "Duck, Duck, Goose" dynamic gets people up and on their feet. It's great fun for preschoolers and kindergartners, but adults can play with more sophisticated rhymes as well.

- Players sit in a circle on the floor, at a table or at their desks.

- One player is chosen as "The Poet" and walks around the circle as they think of a word. They can say nothing, or they can say "word, word, word" (like "duck, duck, duck") as they pass each other player.

- When they choose another person to play, The Poet says, "rhyme" instead of "word," and then they say a word the chosen player must rhyme with (for example, "pan").

- The chosen player must immediately think of a rhyming word.

- If the chosen player can't think of a rhyme word within 30 seconds, The Poet immediately sits down in their place and the chosen student is the new Poet.

- If the chosen player thinks of a rhyme word within the 30 seconds, The Poet must repeat the original process to choose a new opponent.

- If the chosen player can't think of a rhyme word within 30 seconds, The Poet immediately sits down in their place and the chosen student is the new Poet.

For younger students, you may want to have a list of one-syllable words they can choose from (such as words that rhyme with free). Older students may enjoy using difficult words to rhyme, such as words that rhyme with world or words that rhyme with orange.

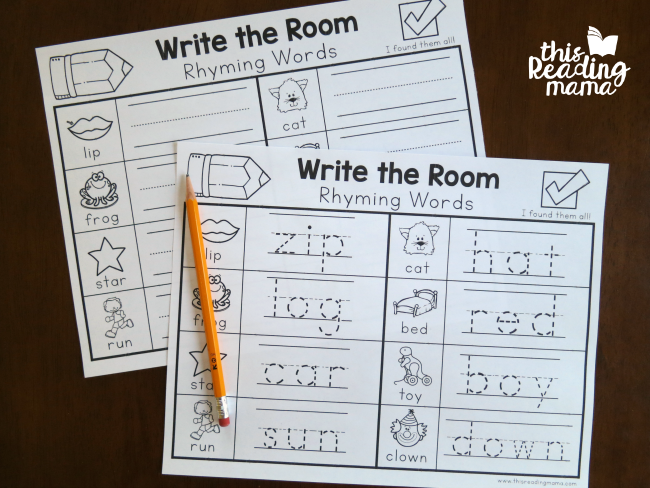

Rhyme Hunt

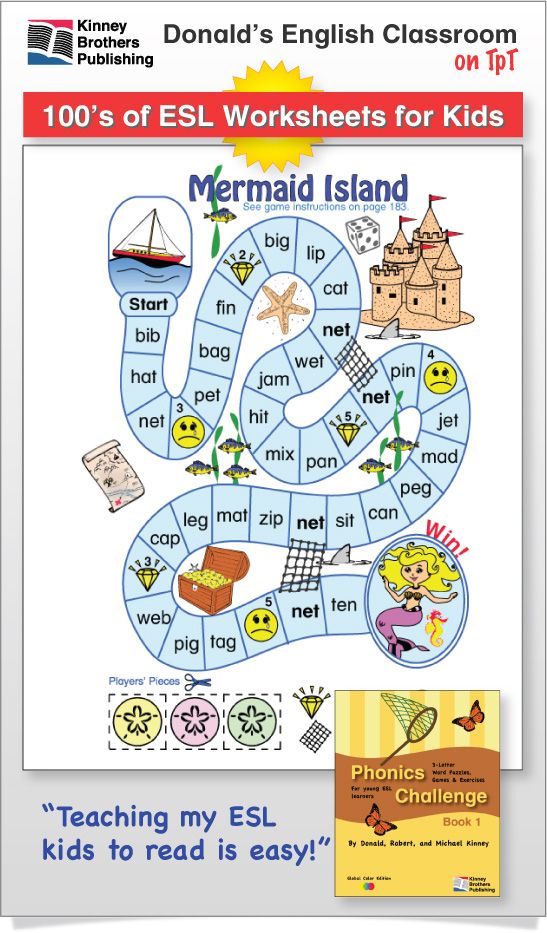

Rhyme Hunt is like a scavenger hunt. It's great for any age level, depending on the words you choose.

- Come up with a list of several groups of rhyming words, ensuring that each group has the same number of words. For instance, you might have one set of 10 words that all rhyme with "set," like "met" and "debt." And then you might have another set of 10 words that all rhyme with "mane," like "reign" and "windowpane."

- Write each of the individual words on index cards and place them all around the room.

- Divide the group into the same number of teams as you have sets of rhyming words.

If you have three sets, then you should divide the players into three teams as well.

If you have three sets, then you should divide the players into three teams as well. - Give each team their "starter" word, so they'll know which rhyming words they should try to find.

- The first team to find all their rhyming words wins.

In an alternative version of Rhyme Hunt, teams can be provided with a list of several non-rhyming words. They must then find these words in the classroom. When they find one, a team member must come up with a word that rhymes with it, striking it off their list. The team that strikes all the words off their list first wins.

Hot (Rhyming) Potato

This game is great for kids and adults alike. All you need is a beach ball or something else to be your hot potato!

- Have everyone sit in a circle.

- Hold up the beach ball and call out a word (for example, "port").

- Hand the ball to the first person on your right.

- As soon as someone else receives the ball, they say a rhyming word ("sort").

- They pass or toss the ball to the next person, who says a rhyme.

- When the ball arrives at a person who can't think of a rhyme, they're out.

- Keep going until there are only two people left. The last person is the winner!

For younger students or English learners, consider adding music to the game (like traditional hot potato) so they have more time to think of a rhyming word. You can make the starting word tricky for older kids or adults.

Nursery Rhyme Mix-Up

Everyone knows the popular nursery rhymes. But what happens if some of the words are missing? Both preschoolers and rhyme-loving adults will have fun with this game.

- Split players into groups of four and choose one judge.

- Choose a nursery rhyme (for example, "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star").

- Recite the nursery rhyme in full once, then repeat only the first line ("Twinkle twinkle, little star.")

- Have three of the players from each group write a new rhyming line on a piece of paper to replace the original second line (for example, "You look like a beautiful sparkly car.

")

") - The player who didn't write the line (the judge) reads the new lines. They choose the best one.

- Have teams share out the lines that were chosen as the best.

- Start again with another nursery rhyme and a new judge.

Challenge older students and adults to match the poetic meter in the nursery rhyme as well as the rhyme itself. For younger players or English learners, go over the nursery rhyme several times and model coming up with example replacement lines as a class.

Where's the Rhyme?

Learn a little bit about poetry as you play this active game! This game is a great way to reinforce different types of rhyme, such as internal rhyme or slant rhyme.

- Split the group into two teams and choose one host.

- Hand each team a different colored dry erase marker.

- Choose a famous poem to project onto the whiteboard or write on a large dry erase board.

- When the host says, "go," one player from each team runs up to the board and circles all the examples of rhymes that they see.

(They may choose the same rhymes; that's why the markers are different colors.)

(They may choose the same rhymes; that's why the markers are different colors.) - Once they're done, go over the correct answers. Offer extra points to volunteers that name the type of rhyme, or who can name unmarked rhymes.

- Project another poem onto the board and do it again.

Ideally, you could project two versions of the poem at once onto a large whiteboard to give each team their own. You could also do this by handing out a printed copy of the poem to each player and then projecting their answers on a document viewer.

Rhyming Games Are Fun!

Learning all about rhyming words can be a lot of fun for people of all ages and knowledge levels. This is especially true in the case of rhyming games, as the element of play is universal. For more in this area, check out games to play with children to build vocabulary too. You can also challenge students and adults with rhyming skills with an engaging activity on writing limericks.

It's Good for Rhyming - 7 Online Tools for Rhyming Words and Writing Terrible Poems

The idea for this article was seeded by my nephew who wanted a quick poem for his class. I was really surprised how terrible writer's block is. stopped me in my tracks and stopped me from coming up with good rhyming words and a frenetic poem. It took me a while, but I managed to put together a good one. Milton and his buddies will laugh, but I don't think they will throw eggs at me from there.

I was really surprised how terrible writer's block is. stopped me in my tracks and stopped me from coming up with good rhyming words and a frenetic poem. It took me a while, but I managed to put together a good one. Milton and his buddies will laugh, but I don't think they will throw eggs at me from there.

I'm sure you know that creating rhyming verses - albeit a high level one - has its uses. From greeting cards to class assignments, from lovers to Facebook status updates, rhyming words to create a poem are an in-demand art form. I believe that if aspiring poets can have their own poetry applications and collections of poems on the Internet, we amateurs can do a little rhyming help. These rhyming instruments can spout horrible verses, but you might enjoy wordplay.

Rhyme Brain opens with a simple yet attractive interface. This is a multilingual rhyming generator that speaks Dutch, Spanish, Russian, German, French and English. Enter your word in the large field and press Enter. Rhyme Brain generates and displays rhyming words in the language of your choice. Rhyme Brain uses machine learning to match keywords with their phonetic equivalents. Results also include almost rhymes and oblique rhymes (imperfect rhymes). Rhyme Brain can also provide portmanteau and alliteration for you.

Rhyme Brain generates and displays rhyming words in the language of your choice. Rhyme Brain uses machine learning to match keywords with their phonetic equivalents. Results also include almost rhymes and oblique rhymes (imperfect rhymes). Rhyme Brain can also provide portmanteau and alliteration for you.

The rhyme generator database contains 2.6 million words to match your word.

B-Rhymes says it's a rhyming dictionary that doesn't have words for what it does and doesn't. He tries to match rhyming words that sound good together. B-rhymes generate hemispheres that follow phonetic principles, although they can rhyme according to syllables. B-Rhymes really gives you the opportunity to get away without sounding too corny with your verses. B-Rhymes provides each rhymed word with a pronunciation and meaning that indicates its power.

You can also try the B-Rhymes app for iPhone and Android.

The Scholastic site seems just right for kindergarten students, although it is a good teaching tool. Reggie Loves to Rhyme is interactive fun colorful pictures and sounds. It's designed like a game. As you can see in the screenshot, the kids will have to select a room and enter it, they will have to select objects to make them rhyme with another object in that room.

Reggie Loves to Rhyme is interactive fun colorful pictures and sounds. It's designed like a game. As you can see in the screenshot, the kids will have to select a room and enter it, they will have to select objects to make them rhyme with another object in that room.

Scholastic is one of the oldest and largest educational companies in the world with a global presence in 150 countries.

WikiRhymer is a neat, community-created website in the best wiki tradition. Rhymes can be found in the categories of pure rhymes, final, near, close, and mosaic. WikiRhymer has a forum where you can discuss poetry, songs, and anything else related to vowels. The site is small because it is new, but we hope it will grow with some exposure.

The site was founded by a songwriter (Bud Tower).

You just have to take the word... because it comes from Merriam-Webster. One of the oldest and most respected names in the English lexicological space has a well-developed vocabulary designed for children. Word Central has a dictionary, a thesaurus, a rhyming dictionary, and interactive games. The rhyming dictionary has a long list of words that might rhyme with your keyword. I've tried a few words that aren't all that common; the results were impressive. You should expect a resource like Merriam-Webster to have a large index of words to retrieve.

Word Central has a dictionary, a thesaurus, a rhyming dictionary, and interactive games. The rhyming dictionary has a long list of words that might rhyme with your keyword. I've tried a few words that aren't all that common; the results were impressive. You should expect a resource like Merriam-Webster to have a large index of words to retrieve.

According to the FAQ, the online version contains over 70,000 entries, 730 color illustrations, 300 paragraphs of word history, 170 paragraphs of synonyms, and many examples showing how words are used in context.

Rhymes & Chimes has an attractive facade to live up to its name. The mission of the rhyming dictionary is to become the world's largest collection of rhymes created by man. The results are broken down by syllables (from 1 to 3) and you can also search for translations of the word, its usage in phrases and quotes, and other transformations, as you can see in the screenshot. One of the unique features is that it also provides you with citation styles for different types of documents.

What Rhymes With is a simple, no-nonsense dictionary. You can use search to quickly find words that rhyme with each other. The dictionary searches by pronunciation. The results are returned in an easy-to-read flat format. The words are also hyperlinks that you can click on to jump to more rhyming words.

Think of these seven tools as the archetype of this type of word usage. These seven are definitely some of the most beautiful I've come across in my research. I didn't have to dig deep because rhyming dictionaries are as common as pennies. Although good, as they are rare. Don't forget to check out what my friend Ryan wrote a few years ago - a powerful free rhyme generator called VersePerfect that you can download and use.

The seriousness with which these tools are developed and used belies the title of my article. Why scary lyrics? You can use it to write lyrics and good poetry. You? Please comment if you increase your creativity with any rhyme generators.

Image Credit: Poetry via Shutterstock

Lecture by A. Madrid "Wallace Stevens' Place in the History of English Rhyme

" delivered at the 43rd Annual Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture, held since 1900 year.I'm willing to dive straight into presenting the history of rhyme in modern English poetry without anecdotes, banter, novelty or spells. This history has not been sufficiently studied and, for the most part, even those who know it do not know it. Yes, and a non-trivial case of artistic practice by Wallace Stevens can help, not really counting on the title of the lecture. And so, I'll tell you what I know.

In the middle of the 16th century, rhyme was still comfortable on the throne. A man did not try to write a poem without rhymes, just as no one today tries to write a song without rhythm. The desire to write a song is partly the desire to convey the rhythm, one is closely related to the other. And only some egg-headed pervert, consciously defining himself as an alien from Mars, dreams of doing the opposite. And this is the level at which rhyme was in 1550. If you wanted poetry in general, you needed rhyme. People lusted after her.

And this is the level at which rhyme was in 1550. If you wanted poetry in general, you needed rhyme. People lusted after her.

The first great challenge to the dominion of rhyme - a challenge from which (in a sense) it never recovered - was the work of Marlowe, Shakespeare and other Elizabethan playwrights who wrote blank verse for the stage. The achievements of these poets are more or less undeniable, but still - the play is still not a poem.

A lyric poet who sits or stands in a hall and watches a performance of Henry IV, act 1 can easily imagine that the artistic criteria applicable to his or her work are clearly different from those of a play.

The neglect of rhyme may make sense in the context of writing unbridled streams of passionate and seemingly spontaneous conversations, but a poem is a different matter.

In any case, poets (with VERY few exceptions) did not turn away from rhyme. Indeed, Shakespeare or Marlow, when they believed that the text they wrote was poetry, returned to rhyme.

As for the actual rhymes - what is considered a "successful" rhyme - it was a trifling matter. Once - a rhyme is considered accurate if the endings of two words sound more or less the same, and two - there was a strong preference for what we now call "masculine" rhyme - when the words on the rhyme end in a stressed syllable (e.g. tin" and "violin, as opposed to trying” and “frying) . Apart from this difference, for the Elizabethans all rhymes were good.

But then there were interesting changes. Around the time of the Stuart Restoration, 1966) we see something strange. Certain rhymes - indeed, categories of rhymes - were scrapped. Assemblages of rhymes that would have satisfactorily satisfied poets fifty or sixty years earlier have either disappeared or become extremely, extremely rare. In order not to take up much time, I will tell you right now - in the abstract - what kind of rhymes have more or less suddenly disappeared. These were pairs where two words carried an obvious semantic connection to each other. Or in other words, when the true meanings of two rhyming words became problematic. For the Elizabethan poets, involved in an intuitive judgment about the appropriateness or inappropriateness of rhymes in a given pair, the meanings of these two words were of no interest. For the poets of the Restoration, on the contrary.

Or in other words, when the true meanings of two rhyming words became problematic. For the Elizabethan poets, involved in an intuitive judgment about the appropriateness or inappropriateness of rhymes in a given pair, the meanings of these two words were of no interest. For the poets of the Restoration, on the contrary.

I must give some examples. There are no more common rhymes in Elizabethan poetry than {me/thee} {mine/thine} {he/ she}. However, the words in these pairs are always symbolic opposites. {He/she}, {mine/thine} - (he / she, mine / yours) - terms defining a neatly divided dyad (male and female, own and belonging to others) and also these terms are also extremely simple words (personal pronouns - of which each already presupposes its opposite) And so I tell you. - the rhyme {me/thee} becomes very, very rare in the middle of the 17th century, although it was remarkably common in the 16th century. Other oppositions are: ({ever/never} {hither/thither} {many/any} {used/ abused} {kind/unkind} {sad/glad} {one/none} {conceal/reveal} …

Can you see where I'm leading? This type of pairing rhyme is more common than you might think. And I checked - I literally checked - and I'm here to tell you - They either disappeared or became EXTREMELY rare.

And I checked - I literally checked - and I'm here to tell you - They either disappeared or became EXTREMELY rare.

Antonyms are only one category. It would be tedious to give a list to illustrate them all. Synonyms or close synonyms such as {shake/quake} or {moan/groan}; genus-and-species refer to {berry/cherry}; and then pairs of rhymes where the words are extremely simple and occupy a place in decidedly elementary categories. For example {hall/wall} {door/floor} {shirt/skirt} {mother/brother}.

The question is why? Why do poets rhyme them. Why do they do this to themselves?

Isn't rhyming in itself a difficult task? Isn't the paucity of English rhymes - and complaints have been heard since the time of Chaucer - a serious problem for poets? And here we come to very important questions.

First, they were not aware of the change. It was not a conscious strategy. The poets never discussed it. I searched everywhere and everywhere, in table talks, prefaces, diaries, discussions - everywhere. They never discussed it. You can see all this for yourself just by running your finger over the right side of their poems, and use the statistics by looking at the rhymes. But they didn't talk about it.

They never discussed it. You can see all this for yourself just by running your finger over the right side of their poems, and use the statistics by looking at the rhymes. But they didn't talk about it.

Great - so why did they do it unconsciously? There are many intriguing hypotheses, but I won't waste your time with the wrong ones. I will simply state the theory that best fits with the observations. Here it is:

They avoided the mentioned rhymes because they felt – intuitively – that such rhymes might weaken the effect they were trying to achieve. They believed that part of the magic of rhymes definitely depended on the two words put on the rhyme, and which were in no way related to each other in the reasoning of meanings. If the first word of the two inherently and inevitably supports the second (for example, moan/groan or he/she), then the poem loses what might be called the "metaphysical" effect of combining dissimilar words when their intimate similarity is revealed. Lost the power of mystery.

Lost the power of mystery.

All rhymers in all ages believed - wordlessly, mutely, even incoherently, but they believed that rhyme, accentuating and thus multiplying the effect of rhythm in a poem, helped to enchant the reader, including the incomprehensible nature of pleasure when reading a poem - and silent and reluctant consent with what was said there. They thought rhyme was a drug. And the unconscious suppression of rhyme may have been seen as a release from this addiction, which is simply what happened in general in the 17th and 18th centuries in an effort to improve English versification.

It should be pointed out that the reader was under no circumstances required to pause on these rhymes in order to partake of them for their own sake. Such behavior would break the very spirit of the rhyme - break the trance - break the spell. So the poets, to a certain extent, felt comfortable resorting to the same reefs, over and over and over again.

{Life/strife} {death/breath} {fire/desire} {love/move/prove}

{grace/face} {youth/truth}

- These rhymes are EXTREMELY common in all ages of English versification, and no one complained until the rhyme was buried in the grave. One way or another, but we can conclude - The reader was not asked to think about the verses, - he was asked to feel them, as a musical rhythm is honored,

One way or another, but we can conclude - The reader was not asked to think about the verses, - he was asked to feel them, as a musical rhythm is honored,

Poems were not a cipher, they were not supposed to have an intellectual content - and, above all, they were not a field of knowledge. They were a drug, They gave strength. They seduced. Poets rejected rejected {sad/glad} and {shake/quake} for the same reasons as rhyming sad and sad - such rhymes seemed to exclude the meaning of rhyming altogether.

Further, the perception of rhymes that I describe characterizes the entire Augustian Epoch. * The tide has ebbed and these secret attitudes have weakened, just as Romanticism appeared. The turning point was the publication of a three-volume work that was extremely important and had a huge impact, which, drooling, rarely happens these days - Percy's book "The Relics of Ancient English Poetry", a semi-scholarly anthology containing (among other things) many, many folk ballads of the 15th and 16th centuries. And these poems entered the blood of such poets as Blake, Coleridge and Wordsworth. The material presented there, with emotional immaturity and brave narrative, lacking in argument and emotion, seemed to these poets (and countless hosts of others) to be a shot in the vein of English poetry, just waiting for it.

And these poems entered the blood of such poets as Blake, Coleridge and Wordsworth. The material presented there, with emotional immaturity and brave narrative, lacking in argument and emotion, seemed to these poets (and countless hosts of others) to be a shot in the vein of English poetry, just waiting for it.

Poets rushed to imitate the old ballads, and to import into the art of English poetry the practice of rhyming, which had been put aside until now. Poems of an Old Mariner is a great example of this. "Songs of Innocence and Experience" is another example.

And here we come to Curious George, Lord Byron. The ideal dissertation - Byron is a favorite of writers. Because it represents, and in the singular, the dividing mark.

A wall separating archaic rhymers from wanting rhymes as an intoxicating element, rhythmic fiction operating entirely outside the reader's mental radar - and the sensibility of contemporary poets who attempt to connect every rhyming pair with a judgment associated with originality and punning wit. The dividing wall, I will say, runs through the median line of the crack of latitude, between the two halves of Byron's brain - soaked in alcohol and sex.

The dividing wall, I will say, runs through the median line of the crack of latitude, between the two halves of Byron's brain - soaked in alcohol and sex.

His poetic commitments were strictly Augustian. He bowed to Dryden and Pop, scorned Keats, and followed the arcane rules of rhyme more zealously than his exponents - when he wrote seriously (Childe Harold, for example). But when he wrote the poetry, on which his reputation is largely based today, he was doing something new. He composed - comic rhymes.

Let's say - "new". Of course, this had happened before - and pretty much, in Samuel Butler's Hudibras (which was read and studied by everyone in those days), but Butler's work was a fanged satire on Puritans - Byron's Beppo and Don Juan are destructive, although not quite satires.

Butler performing burlesque. The extreme unevenness of the meter and the rhymes wherever you find them - metaphorically - literally assert that the Puritans are a herd of degenerate perverts, absurd and annoying. Byron is fundamentally softer.

Byron is fundamentally softer.

His "parodic elements" are unambiguous, and on the one hand they are addressed to contemporary sexual mores, on the other hand, to an honest and impregnable reader's assurance of the honesty and grandeur of the poem. When Byron introduces the never-before-seen {intellectual/hen-peck'd you all} rhyme, and which he does, of course, over and over again, he (in appropriate places) makes fun of poetry in general. This is a way of releasing anti-poetry.

Let me read a stanza from Don Juan with the rhyme {intellectual/hen-peck'd you all},

'Tis pity learned virgins ever wed

With persons of no sort of education,

Or gentleman, who, though well born and bred ,

Grow tired of scientific conversation;

I don't choose to say much upon this head,

I'm a plain man, and in a single station;

But—oh! ye lords of ladies intellectual,

Inform us truly have they not hen-peck'd you all?

It is a pity that virgin scholars never came out

For uneducated husbands,

Or gentlemen, although well-born and bred,

But tired of scientific conversations.

I don't have much to say about this.

I am a simple man, and of low rank,

But - oh! You are smart lords, masters of ladies,

Tell me honestly that you are all under their thumb.

(translated by T. Gnedich, it looks like this -

I am very, very sorry that rake

Smart girls are getting married.

But what to do if the poor demon

Is tired of learned conversation?

(I keep the interest of my neighbors,

Such a mistake will not happen to me;

But, alas, you are spouses of such ladies,

Admit it: everything is under their shoe!)

Approx. translator)

This move at the end here - this move - is magnificent and funny and (this is the key) remember - the rhyme pair itself {intellectual/hen-peck'd you all}, may have been trimmed from the poem and cited as an example of an inspired punning mind in itself. This is actually the point. An analogy can be drawn to the exciting effect when a movie actor suddenly turns to the camera and directly addresses the audience in a movie theater. The excuse for "postponing distrust" is dropped, and the medium openly admits his ruse. But winking

The excuse for "postponing distrust" is dropped, and the medium openly admits his ruse. But winking

Consider for a moment how THIS goes against the spirit of conventional rhyming. The poets wanted the rhyme to act beyond the reader's mental radar, an absolute denial, a denial for the "actor" to suddenly look into the camera. But this did not happen. Let us remember that no matter what the intentions of the poets were, or what they said, their unmistakable intuitive adherence to apropos to their prosody led to the defense of magic at all costs. The problem of punning wisdom, and originality, and interchangeability of this pair of rhymes did not exist. With Byron, she unexpectedly appeared.

As a result of prolonged work, this development killed the rhyme. Suddenly, a terrible suspicion was thrust into people's heads that perhaps many, many rhymes should now be considered cliches ... Gradually it became the norm to believe that a "good" rhyme is one that did not exist before. That a good rhyme is worth quoting on its own.

That a good rhyme is worth quoting on its own.

The global effect - when no doubt it began to be believed that it was not the individual rhyme that mattered, but rather that the whole poem rhymed - began to take effect in the early 19th century, corroding the feeling that a particular rhyme should delight the reader regardless of the poem to which it was stuck . The new concept grew and gained strength for a hundred years - and then the rhyme more or less collapsed.

In the real art of poetry. In songs we are still living in 1550. But in the books of the real art of poetry, we live in rhyming rubbish. And then we come to Wallace Stevens.

On the one hand, Wallace Stevens is what he calls a "classical" poet. If one examines his rhymes (or rhyme groups), there are not many exotic examples to be found - examples that might draw attention on their own for whatever reason. I have a Favorite of his where I marked each rhyme with a color - and I made a handy list his rhymes, they are all written out in microscopic letters on two or three sheets, so that everyone can study the whole problem quite easily. And I am ready to announce that 99% of Wallace Stevens' rhymes are patterned after {hail/tail}, {near/clear} {ended/mended}…{hat/sat}. OF COURSE, there are notable exceptions - and perhaps there are people here who could add measurements from memory - my example would be -

And I am ready to announce that 99% of Wallace Stevens' rhymes are patterned after {hail/tail}, {near/clear} {ended/mended}…{hat/sat}. OF COURSE, there are notable exceptions - and perhaps there are people here who could add measurements from memory - my example would be -

{Übermenschlichkeit | would soon come right}.

And yet. Let's look in Favorites and see miles like this—{parks/marks} {flies/skies} {play/day} {around/sound}.

Even during the most rosy period of Stevens' work, virtually all of his rhyming pairs not only could appear in Alexander Pop's poem - they defiantly appear in Alexander Pop's poem.

MORE THAN, it has been observed that Stevens rarely violates the principles of 17/18th century rhyme described above. And again. We cannot expect constant consistency when dealing with the experience of prosody, which occurs more or less unconsciously. And yet Stevens is constantly following Dryden or Pop, Swift or Samuel Johnson, avoiding rhymes where the words involved are connected to each other by something other than sound. And in this regard, as I said, Stevens is a classic rhymer. And this will hardly surprise anyone, given his commitment to "irrational" poetry, to its deep narcotic effect, and which I am talking about here. (And perhaps we'll hear more about that from other speakers today.)

And in this regard, as I said, Stevens is a classic rhymer. And this will hardly surprise anyone, given his commitment to "irrational" poetry, to its deep narcotic effect, and which I am talking about here. (And perhaps we'll hear more about that from other speakers today.)

HOWEVER, Stevens' rhymes are sharply opposed to regular classical rhyme unless he uses a rhyme through. The total number of poems by Stevens, where rhymes demonstrate "on schedule" how this happens in the poetry of the 20th century, is eleven. (I counted - eleven. There are eleven of them. And of course, they are almost all in the Harmonium and in the Ideas of Order).

Stevens quite clearly prefers to deploy the effect of the rhyme in a "smarmy style". The word at the end of the stanza turns around when reading the line of the next stanza as a pair to the word at the end of the previous one.

It does not actually come from an ancient intuition in assuming the meaning of the rhyme. Rhymes still work, bringing "inexplicable pleasure. " But Stevens' approach does reduce rhyme to the status of "partial grace" like alliteration. And thus, while the old-school poet accepted the perception of his or her poem as a whole with a fair amount of (and indeed super-human) artificiality, Stevens allows rhyme to come and go as it pleases, thus causing unexpected changes in the angle of artificiality. Rhyme playing hide and seek…

" But Stevens' approach does reduce rhyme to the status of "partial grace" like alliteration. And thus, while the old-school poet accepted the perception of his or her poem as a whole with a fair amount of (and indeed super-human) artificiality, Stevens allows rhyme to come and go as it pleases, thus causing unexpected changes in the angle of artificiality. Rhyme playing hide and seek…

In conclusion, I would like to say that the rhymes in Stevens' poems become less and less as the reader goes through his Favorites. He always held to the idea that rhyme was a drug, but increasing seriousness (and even liturgical) sensitivity makes him less and less likely to resort to unexpected attacks on this kind of artificiality - to the point that, for example, such poems as "Aurora of Autumn" contain exactly five unsightly, unsuccessful rhymes - and there are two hundred and forty lines.

There was so much more to say about this, but while rehearsing this performance, I found out that it took seventeen minutes. And therefore, I beg your pardon, and I make way for the next speaker. Those who are curious to take a look at Stevens' list of favorite rhymes can check it out later.

And therefore, I beg your pardon, and I make way for the next speaker. Those who are curious to take a look at Stevens' list of favorite rhymes can check it out later.

Afterword

in four months.

I wonder if anyone remembers the children's sci-fi novel Wrinkles in Time...? There, at the beginning, where one witch (or someone else) explains how they are going to travel through vast expanses in time without traveling at all. There was an illustration (if I remember correctly) of an ant walking along a string. The science fiction concept (which its author L'Angle calls the tesseract (and of course this word is in no way connected with the scientific term of the same name tessera - tessera, formation on the bodies of the solar system) consists in rum, if someone simply marks and then connects two dots on a string, the ant will take one step and voila... When the string straightens out, the ant will easily find itself in another place.0003

Why did I mention this. Because it's a new metaphor for what rhyme is supposed to do. "Unimaginable distance" is overcome instantly, miraculously, and spectacularly. Glide and pride lie far apart, so that the momentary jump from one to the other is like the step of an ant on a string that has not yet been stretched. Do you understand? An ant can get to any place, almost without moving.

"Unimaginable distance" is overcome instantly, miraculously, and spectacularly. Glide and pride lie far apart, so that the momentary jump from one to the other is like the step of an ant on a string that has not yet been stretched. Do you understand? An ant can get to any place, almost without moving.

And now I foresee a danger - one to which I did not take into account in the lecture above. The problem is complicated by the fact that it is difficult to get used to the idea that all this was done consciously. The poets were not afraid that their readers would notice that the word A in the rhyme and the word B there were synonyms. Poets did not choose their words based on coherent theories, and did not care at all that their readers would consider, follow, adhere to, or apply such theories. None of these poets knew what they were doing. They moved intuitively.

And that's why the rhyme was so sensitive to attacks like Milton's (largely on the Paradise Lost front). Milton did what every obscure specialist in English literature does. He explained that the rhyme in the poem is a metaphor. And this metaphor is for captivity, slavery. You don't want to be a slave, do you? I think no. So back to the "ancient freedoms". To Homer, etc. And no one objected! And what could they say? That rhyme is not a metaphor for something, that it has no meaning of its own? That it is actually arbitrary in relation to the theme of the poem?

He explained that the rhyme in the poem is a metaphor. And this metaphor is for captivity, slavery. You don't want to be a slave, do you? I think no. So back to the "ancient freedoms". To Homer, etc. And no one objected! And what could they say? That rhyme is not a metaphor for something, that it has no meaning of its own? That it is actually arbitrary in relation to the theme of the poem?

Even if they deliberately thought about all this, they were ashamed to tell about it. And yet it's true. The rhyme itself contains no more thematic context than a comma.

(I wonder in this connection how to explain the rejection of the comma in modern poetry? Note by the translator). Or in other words, rhyme has a function, but says nothing. If you need these effects, then rhyme. If you don't care about effects (or can hide them anyway) then you can rhyme.

Quite a simple idea! But the poets of the past practically, in the medical sense, could not think of it, because they could not bear the idea that rhyme and meter add nothing to the content.

Intuition told them that if some element of the poem is arbitrary in relation to the content, then it is defective and should be expelled. And even in our day, nerds write works "justifying" the presence of rhyme in such-and-such statements, where, as they say, rhymes are introduced as metaphors for harmony. If Romeo said something, and Juliet answers in rhyme, then such a conversation symbolizes their love. And if two people hate each other to the liver and speak in rhyme, then this is irony.

Such an idea could only come to the mind of someone who does not like rhyme, but tries to sing it anyway. "He left the picnic and began to eat ants". Or in another way. Suppose that in the future the world is run by robots who have no idea why people enjoy music. Let's imagine that they "explain" musical rhythm as a metaphor for order and regularity, and from this they conclude that the presence of rhythm in the song of, say, Rolling Stone is an ironic element, because ....

But enough. I'm getting frustrated again. I'll end with the main thing guys, which is that any idea based on the assumption that the reader will look askance at rhyming words is wrong. Nobody thinks people will do that, and they don't. The only one who can do this is the one who takes apart a watch to understand how it works. And the problem now is that there are only people who take apart watches, and there are no those left who love rhyme in itself, who lust after it.

I'm getting frustrated again. I'll end with the main thing guys, which is that any idea based on the assumption that the reader will look askance at rhyming words is wrong. Nobody thinks people will do that, and they don't. The only one who can do this is the one who takes apart a watch to understand how it works. And the problem now is that there are only people who take apart watches, and there are no those left who love rhyme in itself, who lust after it.

I beg you, you can already see the sprouts, people return the rhyme to poetry here and there. But they do not yet allow themselves to rhyme the whole poem, they are not yet ready to go that far. Instead, they use rhymes as alliteration. Like "inserted finesse". People still think it's somewhat embarrassing. As for me, I am not ashamed of the Gospels, for in them is God's power for the salvation of those who believe in Christ.

Rhyme is a drug. Rhyme is black magic.

Note:

*

Milton was the last of the writers who preached the values of the Renaissance.

Learn more