Counting the homer

The Homer Calendar lets you count the Omer with ‘The Simpsons’

With Passover now in full force, we have begun counting the 49 days to Shavuot. The ritual of counting the Omer may seem like a tedious goal, but Brian Rosman found a way to make it relevant: theme it around America’s favorite TV family, The Simpsons.

Rosman’s website, The Homer Calendar, is a simple concept. For each night of the Omer, there is a web page with the blessing and the counting… along with a picture of Homer Simpson. There is even a printable version in case you want to plaster the many faces of Homer on your wall.

In addition to the Omer calendar, the website continually catalogs every Jewish-related joke in The Simpsons history. Considering the show has been on for 30 years, this is no easy task.

In honor of the Homer Calendar’s 20th anniversary, we asked Rosman a few questions about his “one joke taken way too far,” as well as his thoughts on Jewish Simpsons fandom.

***

PopCholent: What inspired you to create the Homer Calendar?

Brian Rosman: I was inspired by the opportunity to marry together almost all of my major interests: popular culture, humor, Jewish observance from a non-traditional approach and the internet. The joke (Homer=Omer) was not my original idea. But when I first heard it in 1999, it immediately came to me as a website calendar where one could click on a date and the Omer count for the day would pop up, along with a Homer Simpson picture. This was back when everyone was making their own primitive websites. I had first started watching The Simpsons in Israel, when our family lived there in the mid-90s, and our daughter was 5 and 6. It was one of the many subversive things we did together. So in 2000, a friend, Yosef Abramowitz, had just started a web site for Jewish families, and he offered to host the original site.

How can the Homer Calendar get kids interested in something as mundane as counting the days to Shavuot?

I’m not sure it does, or at least not that much. Kids know when they’re being sold something. But Jewish educators have again and again tried to use

The Simpsons as a way to entice young people to engage with Judaism. When The Simpsons Movie came out in 2007, the Jewish Outreach Institute suggested using the film to somehow “encourage participation in Jewish community.” They even recommended using the Hebrew-dubbed version released in Israel for an introductory Hebrew course.

Kids know when they’re being sold something. But Jewish educators have again and again tried to use

The Simpsons as a way to entice young people to engage with Judaism. When The Simpsons Movie came out in 2007, the Jewish Outreach Institute suggested using the film to somehow “encourage participation in Jewish community.” They even recommended using the Hebrew-dubbed version released in Israel for an introductory Hebrew course.

A temple in Los Angeles had a Torah study class that watched 10 Simpsons episodes “as a springboard for deeper discussions on Jewish beliefs and values,” and Limmud London included a session, The Wisdom of the Simpsons: Learning Jewish Values from our Favourite Animated Family (“You’ve heard of Pirkei Avot; now it’s time to study Pirkei Simpsons”). I heard from the educator at a London synagogue who has a Simpsons mock seder, acts out the weekly Torah portion Simpsons style, and has the students discuss how Bart and Lisa would have reacted to Egyptian slavery.

Is this effective? Putting a Simpsons’ gloss only works if the underlying material has value.

On top of the comprehensive Omer—which you have updated the dates for every year—the Homer Calendar doubles as an encyclopedia of everything Simpsons and Jewish. This includes Jewish moments within the show’s episodes, newspaper articles, and Jewish Simpsons fandom in the real world. Exactly how big a Simpsons fan are you to collect all this?

I’m not one of those Comic Book Guy “fans,” thank you, but I still watch every week… religiously. As everyone knows, the show has lost most its sparkle, but I find occasional funny moments, grins if not laughs. But since I’ve taken on this responsibility as a Simpsons/Jews completist, I watch every episode to see if there’s anything Jewy. And there are, several times a year now. These get added to the site.

The internet has changed a lot in 20 years, when you first launched the Homer Calendar. How has your site adapted to the ever-changing world wide web, and what has inspired you to keep it going?

How has your site adapted to the ever-changing world wide web, and what has inspired you to keep it going?

The site is stuck in early 2000s web design. I do it all by hand, figuring out the code myself, so it’s very, very simple. So it looks very outdated, but it works. When I started, the site had its own message board, but that’s given way to a link to Facebook. I also now send out two Facebook posts and tweets each day of the Omer, one with that night’s count and the other with a Jewish something from the Simpsons.

I’ve been inspired by all the folks who say they depend on it each year. One of the biggest fans was an Orthodox woman, an American immigrant in Israel who went by the name Safta Rivky. She would write to me every year for over a decade to thank me. She died, sadly, in 2017.

Can you share some details on what happened when 20th Century Fox sent you a cease and desist letter?

During my third year, I got an email from Fox’s Beverly Hills lawyers accusing the site of violating their copyright in the Simpsons and demanding that I “cease and desist,” and remove all Simpsons graphics from the site. Interestingly, the letter was dated exactly on Shavuot, the last day of the Omer count. It reminded me of that old joke where the judge gives someone 8 days to take down an illegal sukkah. I wrote back, saying that I thought the site qualified under the “fair use” exception to copyright law, and I also shared some of the praise the site received from Jewish educators. I never heard back. Fox has since let fan websites (there are hundreds of them) know that they won’t get in trouble if they put a disclaimer and copyright notice on all their pages, which I have done.

Interestingly, the letter was dated exactly on Shavuot, the last day of the Omer count. It reminded me of that old joke where the judge gives someone 8 days to take down an illegal sukkah. I wrote back, saying that I thought the site qualified under the “fair use” exception to copyright law, and I also shared some of the praise the site received from Jewish educators. I never heard back. Fox has since let fan websites (there are hundreds of them) know that they won’t get in trouble if they put a disclaimer and copyright notice on all their pages, which I have done.

What is your singular favorite Jewish moment on The Simpsons?

My favorite might be a 2014 episode that covered Jewish nostalgia, theology and our social justice imperative. Krusty dreams of Jewish Heaven, where even Portnoy has no complaints. There’s free egg creams at Ebbets Field where the Brooklyn Dodgers play the NY Giants, and at the Oys ‘R’ Us store, a sign says, “The whole store is a complaint department. ” Meanwhile, people line up at the Joe Lieberman Presidential Library.

” Meanwhile, people line up at the Joe Lieberman Presidential Library.

Krusty’s heavenly reverie is interrupted by a vision of his late rabbi father, voiced by Jackie Mason. “Schmuck,” he calls out, “There’s no Jewish heaven. Our faith teaches us that once you’re dead, that’s it. Kaput. It’s dark, it’s cold, it’s like that apartment we lived in before I started doing weddings. Go back to earth! Do something with your life! Help people!”

Earlier this month we wrote an article in which we stated Futurama‘s Zoidberg probably isn’t the best character to represent the Jewish people. Do you think The Simpsons‘ Krusty the Clown would make a better contender?

Not for me. Krusty lies, cheats, is vain, and cares only about himself. Here are some better suggestions, from the show: First, there’s the innocence of Lisa’s imaginary Jewish friend (“Her name is Rachel Cohen. And she just got into Brandeis.“).

Or, there’s the perceptiveness of Dolph, one of the bullies, who practiced for his Bar Mitzvah in front of his bully friends. Last year he was shown tripping another kid, who then started singing about his pain. Dolph said, “He turned his suffering into entertainment, just like the Jewish people.”

Last year he was shown tripping another kid, who then started singing about his pain. Dolph said, “He turned his suffering into entertainment, just like the Jewish people.”

Or perhaps the Jewish pride of Duffman, the mascot/spokesman for the Duff Beer company. In a 2018 episode, he shows up at Moe’s wedding, but announces he needs to leave soon, because, “Duffman has a beer mitzvah at 4:00. Putting the brew, in Hebrew. Oh, yeah!”

But perhaps my choice is Rabbi Krustofski, Krusty’s father. Although he disagreed with his son’s choice of career and lifestyle (“Seltzer is for drinking, not for spraying. Pie is for noshing, not for throwing.”), in a 1991 episode, Bart successfully used real Talmudic passages to convince the Rabbi to reconcile with Krusty.

As if The Simpsons could find a plot they haven’t done yet, what is the next Jewish topic you would like them to cover?

For this week, it would have to be a parody of Shtisel. Or perhaps work in Sukkot somehow, my favorite holiday.

Or perhaps work in Sukkot somehow, my favorite holiday.

The Counting of the Omer

סְפִירַת הָעוֹמֶר

Level: Basic

- Significance: Connects Pesach (Exodus) to Shavu'ot (giving of the Torah)

- Observances: Count the number of days every night

You shall count for yourselves -- from the day after the Shabbat, from the day when you bring the Omer of the waving -- seven Shabbats, they shall be complete. Until the day after the seventh sabbath you shall count, fifty days... (Leviticus 23:15-16)

You shall count for yourselves seven weeks, from when the sickle is first put to the standing crop shall you begin counting seven weeks. Then you will observe the Festival of Shavu'ot for the L-RD, your G-d (Deuteronomy 16:9-10)

According to the Torah (Lev. 23:15), we are obligated to count the days from Passover to Shavu'ot. This period is known as the Counting of the Omer. An omer is a unit of measure. On the second day of Passover, in the days of the Temple, an omer of barley was cut down and brought to the Temple as an offering. This grain offering was referred to as the Omer.

On the second day of Passover, in the days of the Temple, an omer of barley was cut down and brought to the Temple as an offering. This grain offering was referred to as the Omer.

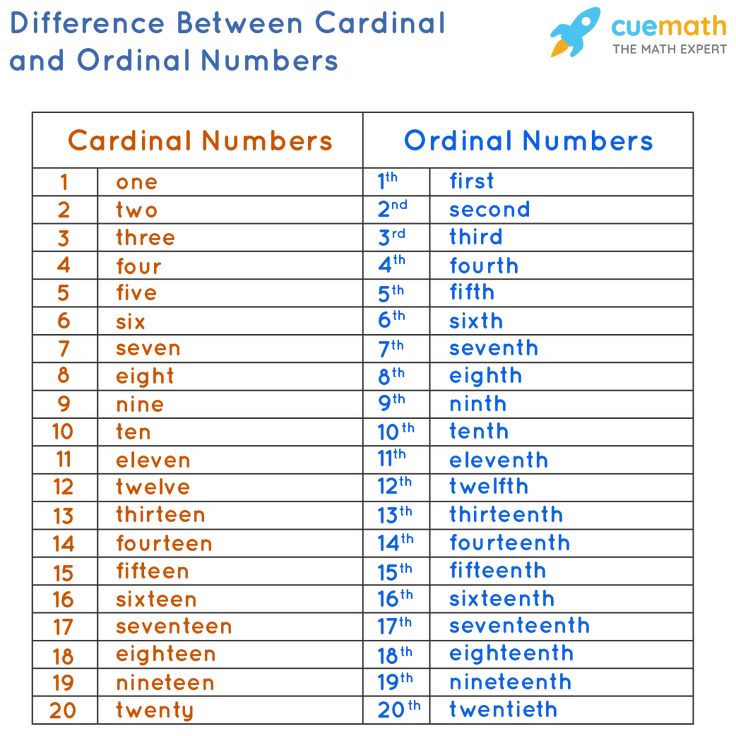

Every night, from the second night of Passover to the night before Shavu'ot, we recite a blessing and state the count of the omer in both weeks and days. So on the 16th day, you would say "Today is sixteen days, which is two weeks and two days of the Omer." The Orthodox Union has a chart that provides the transliterated Hebrew and English text of the counting day-by-day. Or if you'd prefer an amusing (yet still accurate!) Simpsons-themed discussion of the Omer along with an Omer calendar, check out The Homer Calendar.

The counting is intended to remind us of the link between Passover, which commemorates the Exodus, and Shavu'ot, which commemorates the giving of the Torah. It reminds us that the redemption from slavery was not complete until we received the Torah.

This period is a time of partial mourning, during which weddings, parties, and dinners with dancing are not conducted, in memory of a plague during the lifetime of Rabbi Akiba. Haircuts during this time are also forbidden. The 33rd day of the Omer (the eighteenth of Iyar) is a minor holiday commemorating a break in the plague. The holiday is known as Lag b'Omer. The mourning practices of the omer period are lifted on that date. The word "Lag" is not really a word; it is the number 33 in Hebrew, as if you were to call the Fourth of July "Iv July" (IV being 4 in Roman numerals). See Hebrew Alphabet: Numerical Values for more information about using letters as numbers.

Haircuts during this time are also forbidden. The 33rd day of the Omer (the eighteenth of Iyar) is a minor holiday commemorating a break in the plague. The holiday is known as Lag b'Omer. The mourning practices of the omer period are lifted on that date. The word "Lag" is not really a word; it is the number 33 in Hebrew, as if you were to call the Fourth of July "Iv July" (IV being 4 in Roman numerals). See Hebrew Alphabet: Numerical Values for more information about using letters as numbers.

There was at one time a dispute as to when the counting should begin. The Pharisees believed that G-d gave Moses an oral Torah along with the written Torah, and according to that oral Torah the word "Shabbat" in Lev. 23:15 referred to the first day of Passover, which is a "Shabbat" in the sense that no work is permitted on the day (Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are both referred to as "Shabbat" in this sense, though they cannot both occur on a Saturday in the same year; see Lev. 23:24 and 23:32; see also Lev. 23:39 the first and eighth days of Sukkot are called "Shabbat"). In this view, held by most Jews today, the counting begins on the second night of Passover, that is, the day after the non-working day of Passover. The Tzedukim (Sadducees) rejected the idea of an oral Torah and believed that the word "Shabbat" in Lev. 23:15 referred to the Shabbat of the week when Pesach began, so counting would always begin on a Saturday night during Passover. The Sadducees no longer exist; today, only a small sect call the Karaites follow this view.

23:24 and 23:32; see also Lev. 23:39 the first and eighth days of Sukkot are called "Shabbat"). In this view, held by most Jews today, the counting begins on the second night of Passover, that is, the day after the non-working day of Passover. The Tzedukim (Sadducees) rejected the idea of an oral Torah and believed that the word "Shabbat" in Lev. 23:15 referred to the Shabbat of the week when Pesach began, so counting would always begin on a Saturday night during Passover. The Sadducees no longer exist; today, only a small sect call the Karaites follow this view.

Lag B'Omer will occur on the following days of the secular calendar:

- Jewish Year 5782: sunset May 18, 2022 - nightfall May 19, 2022

- Jewish Year 5783: sunset May 8, 2023 - nightfall May 9, 2023

- Jewish Year 5784: sunset May 25, 2024 - nightfall May 26, 2024

- Jewish Year 5785: sunset May 15, 2025 - nightfall May 16, 2025

- Jewish Year 5786: sunset May 4, 2026 - nightfall May 5, 2026

For additional holiday dates, see Links to Jewish Calendars.

☒

Reminiscences of Homer and Virgil. Poetry in Western European Manuscripts of the Russian National Library

1. Baebius Italicus (c. 45 - c. 95).

Ilias latina (Bellica Troia).

1455, Italy (Venice).

Post. in 1966

Lat. Q.v.XIV No. 6

2. Statius, Publius Papinius (c. 45 - 96).

Liber Achilleydos (Achilleid).

1454, Italy (Venice).

Post. in 1983 from the collection of V. F. Gruzdev.

Lat. Q.v.XIV No. 7

The most popular Greek poems in antiquity, the Iliad and the Odyssey, whose author is considered Homer, were not read in medieval Europe. However, the Trojan story was well known and widely studied in medieval schools from Latin compilations and adaptations of Roman authors. Such reminiscences include the Latin Iliad attributed to Publius Bebius Italicus (c. 45 - c. 95) - the consul-prefect of the Roman Empire and the popular tribune under the emperor Vespasian, and the "Achilleid" by the Latin poet Publius Papinius Statius (c. 45 -96).

45 -96).

The Iliad by Bebius is a loose retelling of the Homeric epic in 1070 hexameters, with a notable influence from the poetic styles of Virgil and Ovid. Despite its wide popularity in the Middle Ages, only a few fragments of it have survived to this day.

It is believed that Statius began working on Achilles shortly before his death, between 94 and 95, and managed to write only the beginning of a poem of 1127 hexameters (the first book and the beginning of the second). It tells about the early years of Achilles and his life on the island of Skyros. Peru Statius also owns a poem about the Theban war "Thebaids", a collection of poems "Silva" and a number of other poetic works, including a laudatory ode in honor of the emperor Domitian. Statius' work was popular in late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Statius highly appreciated Dante, considering him the second poet after Virgil and including him among the characters of the Divine Comedy.

The codices of the poems Bebia Italica (Lat. Q.v.XIV No. 6)

Q.v.XIV No. 6)

and Station (Lat. Q.v.XIV No. 7)

stored in the Department of Manuscripts of the National Library of Russia are identical in material (parchment), writing and decor. As indicated in their colophons, they were copied in 1454 and 1455. member of the Council of Forty in Venice Pietro de Rossi (Petrus de Rubeis)

. Council of Soroca (Kvaratia) - the state body of the Venetian Republic performed the functions of the supreme court. Given these circumstances, let us assume that Pietro Rossi, who held a high office, was well educated and belonged to the Venetian humanist circles. According to the composition, appearance and size, it is obvious that earlier both manuscripts formed a single whole. When the manuscript was divided is unknown: Bebiy's Iliad entered the Department of Manuscripts of the State Public Library at 1966 from another branch of the library, and "Achilleid" Statiya - in 1983 from the collection of a military doctor, a major Leningrad bibliophile Vitaly Feofanovich Gruzdev (1893 - 1982).

3. Miscellanea:

Vergilius Maro, Publius (70 - 19 BC).

Bucolica; Georgica;

Persius Flaccus, Aulus (34 - 62).

Saturae cum scholiis;

Proba, Faltonia Betitia

(c. 306/315 - c. 353/366).

Cento Vergilianus cum glossis;

XV century (II half), France.

From the collection of P. K. Sukhtelen.

Cl. lat. F. No. 8

The composition of the handwritten collection written in the second half of the 15th century is extremely interesting. in France (Cl. lat. F. No. 8). The codex contains Bucolics and Georgics by Virgil, Satyrs by Persius Flaccus, and the poem Cento by Faltonia Betizia Proba.

The book of the Roman poet Aulus Persius Flaccus (34-62), which includes six satires written in hexameter, remained unfinished due to the early death of the author. In fact, only the first work can be attributed to the satirical genre, where, in the form of a dialogue with a friend, the shortcomings of poetry are ridiculed. The rest of the verses are moral sermons on Stoic themes, exposing the vices of Roman society.

The rest of the verses are moral sermons on Stoic themes, exposing the vices of Roman society.

The poem "Centon" by the first Christian poet Faltonia Betizia Proba (c. 306/315 - c. 353/366) contains a verse retelling of the biblical story from the creation of the world to the descent of St. Spirit. Not much is known about Probe: she had a good education and knowledge of the Greek language, read and recited Virgil's poems by heart, wrote in imitation of Virgil and Homer, was a pagan, and then was baptized. In essence, "Cento" is a literary compilation, where Proba's own poems are interspersed with lines borrowed from Virgil.

The selection of the repertoire of the collection and extensive scientific comments on the texts of the poems testify to its correspondence and existence in the scientific literary environment, perhaps in the circle of humanist-philologists studying the features of the Virgilian style and its reminiscence in the poetry of the Middle Ages.

The Code entered the Imperial Public Library in 1836 as part of the collection of P. K. Sukhtelen.

K. Sukhtelen.

Baebius Italicus (c. 45 - c. 95).

Ilias latina (Bellica Troia).

1455, Italy (Venice).

Post. in 1966

Lat. Q.v.XIV No. 6, fol. 1

Statius, Publius Papinius (ca. 45-96).

Liber Achilleydos (Achilleid).

1454, Italy (Venice).

Post. in 1983 from the collection of V. F. Gruzdev.

Lat. Q.v.XIV No. 7, fol. 1

Baebius Italicus (c. 45 - c. 95).

Ilias latina (Bellica Troia).

1455, Italy (Venice).

Post. in 1966

Lat. Q.v.XIV No. 6, fol. 23v.-24

Record of the copyist of the manuscript

Statius, Publius Papinius (c. 45 - 96).

Liber Achilleydos (Achilleid).

1454, Italy (Venice).

Post. in 1983 from the collection of V. F. Gruzdev.

Lat. Q.v.XIV No. 7, fol. 24 vol.

Record of the copyist of the manuscript

Miscellanea:

Vergilius Maro, Publius (70 - 19 BC). Bucolica; Georgica;

Persius Flaccus, Aulus (34 - 62). Saturae cum scholiis;

Proba, Faltonia Betitia (c. 306/315 - c. 353/366).

Cento Vergilianus cum glossis;

XV century (II half), France.

From the collection of P. K. Sukhtelen.

Cl. lat. F. No. 8, sheet. 88v-89

"Satires" Persia Flakka with commentaries

Faltonia Betitsia Sample at work.

Thumbnail from the manuscript of the French translation

of Bocaccio's treatise On Famous Women.

1403 Fr. 598, l. 143 vol.

National Library of France (Paris)

Miscellanea:

Vergilius Maro, Publius (70 - 19 BC). Bucolica; Georgica;

Persius Flaccus, Aulus (34 - 62). Saturae cum scholiis;

Proba, Faltonia Betitia (c. 306/315 - c. 353/366).

Cento Vergilianus cum glossis;

XV century (II half), France.

From the collection of P. K. Sukhtelen.

Cl. lat. F. No. 8, sheet. 72v.-73

Centon by Faltonia Betizia Samples with comments and extensive owner's notes

Bookplate by Pyotr Kornilyevich Sukhtelen

II. Homer in the history of ancient culture.

1. Distribution, performance and first recording of Homer's poems.

a) Distribution and, perhaps, the very creation of poems took place with the help of aeds - singers mentioned by Homer (Demodocus at Alcinous, Phemius at Ithaca). Later, the poems were distributed by professional singer-reciters, the so-called. rhapsodes (“song stitchers”). Then they began to be called Homerids , about which one scholia to Pindar claims that at first they were singers from the Homer family, and later other singers began to be called that. The name of one Homerid was preserved Cyneph of Chios , who, according to legend, inserted many of his own [29] verses into Homer. In the VIII-VII centuries. Homerids are already spreading throughout Greece ( Chios , Delos , Crete, Boeotia, Athens). Whole competitions rhapsodes are established in different places (Salamis, Sparta, Sikioi, Epidaurus), especially in Athens at the Panathenaic holidays.

b) Law of Solon . Sources speak of a decree by Solon (legislator in Athens in the first half of the 6th century BC) regarding the performance of the Iliad and the Odyssey exclusively in Panathenaia, and, moreover, in a certain, strictly sequential order.

c) First recording of poems . Regarding the first recording of Homer's poems, later sources (Cicero, Pausanias, Elian, etc.) say, attributing it to a special commission under Pisistratus in Athens (second half of the 6th century). The late nature of these sources has led some scholars to doubt the existence of a commission under Peisistratus, which, however, is, as we shall see below, an unnecessary criticism. Homer's poems were recorded no later than the 6th century. BC. and was of national importance.

2. The question of Homer's attitude to the recently deciphered Cretan-Mycenaean writing. Cretan-Mycenaean writings of the 14th-12th centuries remained undeciphered for a long time. BC, which promised the opportunity to find a remote written tradition for Homer. Indeed, it was a strange state of affairs that between Mycenae and Homer lay a huge period of time of several centuries, and that, nevertheless, Homer had Mycenaean memories in the foreground. The deciphering of “linear writing B” led to complete disappointment in this matter, because instead of the expected poetic monuments, materials of an economic and everyday nature were found here, although with mention of both many Olympic deities and many Homeric heroes. This question is dealt with by the English researcher Bovra in his work "Homer and His Predecessors" ( M. Bowra , Homer and his forerunners. Edinburgh, 1955). Let us briefly describe this work.

After the decipherment of Linear B, Homer's poems must be considered in connection with the early Greek world. However, the Mycenaean inscriptions do not support the view that Homer used written texts that were more or less historically reliable, as suggested, for example, by T. W. Allen ( T. W. Allen , Homer. The origins and the transmission, p. p. 146 -169), believing that Homer and Dictis knew such a written chronicle, as well as A. V. Gomm ( A.W. Gomme , The Greek Attitude to Poetry and History). There is no evidence of Mycenaean writing in Greece after 1200 BC. There are no traces of him in the so-called. [30] Protogomerian period or about the middle of the 8th century. BC, when a new Greek alphabet began to take shape. The whole society, as it were, suddenly lost its written language and for many centuries, i.e. the whole class that owned this letter should have perished.

Thus, researchers have to start again with Homer, believing that he lived in the second half of the 8th century. BC. and used very ancient material that existed in such places as, for example, Attica, which remained outside the Dorian invasion and was associated with Ionia, as well as Pylos, which had long sent immigrants to Colophon and Smyrna. In Ionia, however, Homer added new material to these legends and preserved the poetic verbal tradition. This oral tradition, according to Bovre, did not need records and always existed without them, between 1200 and 750. Greek heroic poetry, judging by its technique, was originally oral. The new letter was not used in such a narrow official framework as the Mycenaean one, but had a broad, nationwide character and changed continuously, unlike the Mycenaean one. The new Greek alphabet developed independently of the "linear B" and, expressing sounds, not syllables, perfectly conveyed the epic meter, contributing to the flourishing of poetry. If these poems had been created in the 8th century, then, according to Bovre, they would certainly have been written down.

But the monuments of writing forever part with the methods of oral transmission, and this we do not see in Homer. Sometimes, however, Homer uses non-traditional expressions, but extremely rarely ("Iliad", XXII.92, IV.66 ff., "Odyssey", II.246), but the usual tradition he uses leads him even to a contradiction with the meaning (Polyphemus "god-like" "Odyssey", I.70, starry sky in the afternoon, "Iliad", VIII.46).

Homer, no doubt, did not know the letter, but he uses poetic technique so brilliantly that it seems as if he carefully thought out and dictated his poem. Homer stands at the crossroads of an ancient oral tradition and a new art of writing, and to this latter he owes his subtlety and grace. Oral tradition does not prevent the poet from creating his own plots, his own names and characters, refracting history in a peculiar way. Homer is an Ionian, but he still lives in the Mycenaean past and describes everything from the point of view of his former homeland, i.e. from the point of view of a colonist who cannot leave his native land. And although many of the heroes of Homer reflect the real people of his time, but most of them have a Mycenaean past. Therefore, Homer does not know the ancient genealogies that go back centuries, or the offspring of his heroes. His Odysseus or Nestor know their fathers and grandfathers, their sons are known, i.e. all those who are connected with the Mycenaean world, but the pre-Cenean past and the time after it is vague and unclear to Homer. That is why Homer recounts the stories of Hercules, Theseus, the Calydonian hunt, the invasion of Thebes, the battle with the Amazons, i.e., with great [31] thoroughness. again, those legends that are connected with the past of his homeland, with its history, which he knows well.

Homer's poems reflect the Mycenaean era, the time from 1200 to the Ionian migration, and, finally, this Ionian migration itself.

From the Mycenaean time comes the weapons of iron or bronze mentioned by Homer, palaces, things, military customs. The Mycenaean tablets give us the names of many Homeric Greek heroes (pp. 24-26), including those considered Trojans by Homer (Antenor, Hector, Tros).

The second period gave Homer information about the burning of corpses, the use of iron for axes and knives, mentions of Egypt, information about many different peoples in Crete.

The Ionian colonists added something new to their native motifs. There can be no early mention of the treasury of Apollo in Delphi (Iliad IX.404), of the Gorgon on the shield of Agamemnon (XI.36), of tripods on wheels at Hephaestus (XVIII.373), information about the Phoenicians. Shield of Achilles, Mycenaean in form, but Ionian in content. He proves that the poet's heroic tradition coexists with the new society surrounding him.

We can say that heroic poetry existed on the European mainland around 1400 and in the Mycenaean language. After the catastrophe of the XII century. much of this tradition has been lost. The Iliad and the Odyssey remained examples of this long development of the epic, based mostly on oral tradition and absorbing, like the Iliad, actual life facts (pp. 37-39). When Homer wrote the Iliad, many of the events of 1200 were already forgotten, because oral tradition does not speak of them. Events before the Trojan War and after it faded into the background, because this war itself, which united all the Greek tribes against a common enemy, shocked the imagination of entire generations and glorified the heroes of this war. But this was the last great deed of the Achaeans, after which Mycenae fell and which forced people to turn to the great past and pass over in silence the centuries of destruction and destruction of former greatness.

Thus, if we proceed from the arguments of Bovre, then it must be admitted that the decipherment of “linear B” says absolutely nothing about Homer’s literary predecessors, but only confirms the traditional idea of Homer as the designer of centuries-old oral folk art.

3. Popular tradition about Homer.

a) Ancient biographies of Homer. Already in ancient times, questions about the author, place and time of the appearance of Homeric poems [32] were devoid of any certainty. Perhaps only before Herodotus, the Greeks considered Homer the real author of both poems and even of the entire cycle.

1) Fantastic biography . The available 9 ancient biographies of Homer are full of fiction and are the latest forgery. So, for example, the biographies of Homer, signed by the names of famous writers, the historian Herodotus and the philosopher Plutarch, contradict what Herodotus and Plutarch themselves say about Homer. It would be superfluous here to present and analyze all these biographies of Homer, built on all sorts of fantastic combinations and conjectures.[1] For us, perhaps, it would be of some importance to indicate the most ancient and most naive of these fantastic ideas about the life of Homer, which no reflection has yet had time to touch.

2) Let us indicate the most ancient features from the biographies. Among such representations should be attributed the message of Pindar and Stesimbrot about the parents of Homer: this is the river Melet and the nymph Krefeida in Smyrna. Strabo's testimony (XIV.1.37) about the existence of a whole cult of Homer in Smyrna is in harmony with this message. In the same way, one of the ancient opinions is the opinion about his life in Chios, where, as was said, there was a special kind of Homerids, who were the distributors of the works of Homer. In the Homeric Hymns (I.172 f.) we read:

"The man is blind, he lives on Chios, he is stony,

His best songs will remain far away in posterity.

However, the conclusion from this that Homer not only lived, but was also born in Chios, is already a later conjecture.

Among the ancient legends about Homer, one should also include reports about the death and burial of Homer on the small island of Ios near Thera. Everything else is later fiction and conjecture, characteristic not so much of the image of Homer himself in antiquity, but of the creators of this image.

3) We formulate the traditional image of Homer among the Greeks. This traditional image of Homer, which has existed for about 3000 years, if we discard all pseudo-scientific fictions of the later Greeks, is reduced to the image of a blind and wise , who creates wonderful tales under the constant guidance of his inspiring muse and leads the life of some wandering rhapsod . We meet similar features of folk singers in many other nations, and therefore there is nothing specific and original in them. This is the most common and most common type of folk singer, [33] the most beloved and most popular among different peoples. In this regard, it may be necessary to interpret the very name "Homer", which is probably nothing more than a personification of one or more features from the image of a folk singer that we have just formulated. Efor interpreted this name as Ho m? hor?n, i.e. "unseeing", i.e. as "blind"; G. Curtius - as a "builder"; K. Mullenhof - as "communicating", "comrade".

b) The time of Homer's life Hellanic and pseudo-Plutarch's biographer attributed Homer to the Trojan War (1196-1183), i. e. by the beginning of the 12th century; Crates, head of the Pergamon Library - by the time 80 years after this war, i.e. by the end of the 12th century; Eratosthenes - by the time 100 years after the Trojan War, i.e. to the 11th century; Aristotle and Aristarchus (II century BC) - by the time the Ionian colonies were founded (1044), i.e. 140 years after the Trojan War, by the 11th century; Apollodorus - 100 years later, i.e. to the X century; Herodotus II.145, cf. II.53 - 400 years after the Trojan War, i.e. to the eighth century. (also Thucydides I.3.3) - like some - by the beginning of the Olympiad (776). Many orientated Homer around the time of Hesiod, which is also not exactly known; to the time before Hesiod attributed Homer Xenophanes, Heraclid Pontus, Philochor and others; by the time of Hesiod himself - Ferekid, Hellanic, Herodotus (II.53). Varro and others; by the time after Hesiod, Actions, Philostratus, and perhaps already Simonides and Ephorus. Homer was also attributed to the age of Lycurgus, i.

e. also by the 8th century, Ephor and others. Theopompus, the historian, identifying the Cimmerians, in the Odyssey, XI.12-19with historically known Cimmerians, refers Homer to the age of Archilochus and Gyges, i.e. to the 7th century Finally, others considered Homer even a student of the historian and geographer Aristaeus Proconesus, i.e. attributed to the first floor. 6th century Thus, the Greeks themselves attributed the life of Homer to the time from the 12th to the 6th centuries.

c) Homer's place of birth also caused the most hopeless controversy. Subsequently, there was even an epigram listing seven cities that claimed to be the birthplace of Homer (Smyrna, Chios, Colophon, Ithaca, Pylos, Argos, Athens). But there were even more. Political and patriotic tendencies are very transparent in these opinions (some Ionian clans, for example, directly elevated themselves to Homer; the Cypriots put forward the mentioned Aristaeus). The diversity of opinions about the birthplace of Homer in Hellenistic times reached the point that he was considered a Babylonian, a Syrian, an Egyptian, and a Roman. All these are later combinations, which themselves testify to their failure.

d) Works of Homer . The Greeks also knew little about the works of Homer. Callinus, to whom the first mention of Homer belongs in general, calls him the author of The Thebaid, which could rightly serve as confirmation for those [34] who denied Homer's authorship of the Iliad and the Odyssey. Initially, in general, all cyclic poems were attributed to Homer. Herodotus (II.117) is already showing some criticism, believing that the "Cyprias" did not belong to Homer, since Paris travels to Troy in them for three days, but according to Homer (Iliad VI.291) is very long. Elsewhere (IV.32) Herodotus doubts the epigones. In the IV century. already quite well learned to understand the difference between Homer and the cycle, and the best example of this is Aristotle (Poet. 23). In Alexandrian times, Xenon and Hellanicus attributed both poems to different authors (for which these scholars were nicknamed "dividers"). Aristarchus attributed both poems to Homer, while others attributed them to different ages of his life. However, already Plato (Hipp. min. 363 b) and Aristotle (Poet. 24) perfectly understood the stylistic difference between the two Homeric poems.

All this, however, already goes far beyond the limits of the popular tradition about Homer in antiquity and already borders on a critical approach.

4. Antique criticism of Homer.

a) The detractors of Homer . The first interesting phenomenon that we meet in the field of Homeric criticism and meet very early is the severe condemnation of Homer from the point of view of religion and morality, which arose as a result of the high development of cultural self-consciousness in the period of the classics. Already in the 6th and 5th centuries, many were jarred by the frivolity of Homer and the appearance of his gods and heroes with numerous human weaknesses and even vices, which was incompatible with the deep religious and philosophical consciousness of this era.

The Pythagoreans and Orphics are known as the main critics of Homer, and through them this desire to blame was transferred to other representatives of philosophical thought. Xenophanes (B 11 Diels 4 ) wrote: “Everything that is dishonorable and shameful among people was attributed to the gods Homer and Hesiod: theft, adultery and mutual deceit” (cf. B 12 and AN). Heraclitus (B42) "said that Homer deserved to be expelled from public meetings and punished with rods." Plato (R. R. II 377 D-378 D) considers the myths of Homer and Hesiod about the gods, such as the struggle of Uranus and Kronos, the chaining of Hera by Hephaestus, or the overthrow of Hephaestus from heaven by Zeus himself, to be a very thin lie. Homer, according to Plato (ibid. X 598 E - 600 E), knows how to portray life well, but understands nothing in it and cannot teach anything in it, because no one will make him his legislator, commander or educator. Even Epicurus did not lag behind Plato in censuring Homer (frg. 228 Usen.).

But Homer was criticized not only by philosophers. The rhetorician Zoilus of Amphipolis became famous for his ardent condemnation of Homer at the beginning of the 4th century. BC, who wrote an essay against Homer in 9 books called "Scourge against Homer". [35]

b) Homer . Of course, there was no shortage of admirers of Homer, despite the well-known discrepancy between this latter and the level of further development of civilization. It is known about a certain Theagenes of Rhegius that even in the time of Cambyses he spoke in defense of Homer and was the first writer to subject Homer to discussion. Various awkwardnesses in Homer were circumvented by their allegorical interpretation. This is found in Anaxagoras, Metrodorus of Lampsacus, Stesimbrotus of Thasos. Demetrius of Falerei defended Homer against the philosophers. The Stoics, Philodemus, Zenon, Cleanthes, Chrysippus, Crates of Molos, Heraclids of Pontus, became especially famous in the allegorical interpretation of Homer, as well as of all ancient mythology, following the Cynic Antisthenes. Other Socratics did not at all share this allegorical method, as can be seen from various places in Xenophon and Plato. The allegorical method did not disappear throughout Hellenism, survived to the Neoplatonists and turned into a whole system of philosophy and mythology, where, strictly speaking, it had already ceased to be an external allegorization and turned into the main tool of the dialectic of that time. And in general, the last centuries of antiquity are distinguished by the desire to save Homer both as a poet and as the father of philosophers - a tendency that clearly revealed itself already in the age of the Greek Renaissance (Maxim of Tire, Dio Chrysostom) and which makes itself felt in all later Orphic literature and numerous quotations from Homer among the Neoplatonists and in the Chaldean oracles. Porfiry owns a whole treatise “On the Cave of the Nymphs”, in which this philosopher subjects the image of a cave in Ithaca known to us from the XIII song of the Odyssey (though very mysterious) to a philosophical and symbolic interpretation.

Orator of the 4th c. AD Themistius (Orat. 20) directly calls Homer "the forefather and founder of the reasoning of Plato and Aristotle."

c) Scientific criticism. One of the earliest poets and grammarians who worked on the text of Homer was a writer of the 5th century. BC. Antimachus of Colophon. But if we would like to imagine exactly how the later ancient philologists, namely the Alexandrians, studied Homer, then the best material for this could be the XXVth chapter of Aristotle's Poetics, where all possible approaches to the writer's text are considered with pedantic detail in order to interpretations or corrections.

Here it is necessary to mention the famous names of the Alexandrian scholars who labored over the interpretation, correction and edition of the Homeric text, these are Zenodotus of Ephesus, Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace. The first of them divided the Iliad and the Odyssey into 24 cantos each and was distinguished by great courage in correcting the text of Homer, going as far as deleting entire verses. The second is known for his [36] prudence, caution and great philological insight. The third republished Homer, identified false places in it and, approaching critically, established the text. In the Venetian manuscript of Homer, one can also find scholia from Aristonicus, Didymus, Herodian, Nicanor. There were quite a few editions of Homer in antiquity. It was published by both cities and private individuals (for example, it is known that Aristotle published Homer for his famous student Alexander the Great).

Despite the thoroughness of the work of the Alexandrian scholars, at the present time it is regarded in many respects not very highly because these scholars wanted at all costs to make Homer a clear, understandable, generally accessible and completely perfect poet, removing from him everything archaic, incomprehensible and contradictory. This greatly reduces the dignity of their work on Homer, leaving in our hands a cleaned and corrected writer, although in other respects the work they have done remains valuable and necessary to this day.

d) Aristotle on Homer. In conclusion, we would like to quote some thoughts from Aristotle, in which the famous philosopher, it seems to us, formulates the general attitude of antiquity towards Homer, although deeply critical, but positive and even enthusiastic.

In chapter XXIV of his "Poetics" he writes (translated by Novosadsky): "Homer deserves praise in many other respects, but especially because he is the only one of the poets who knows perfectly well what he should do." And further: "... and he has nothing uncharacteristic, but everything has its own character." In Nicomachean Ethics III.5, Aristotle claims that Homer in his poems reproduced ancient social and political life (cf. also frg. 154) and, therefore, his characteristic concerned human life in general. With Homer in mind, Aristotle also writes in Poetics (same ch.): “In epic, the illogical is imperceptible, but the surprising is pleasant.” Since Homer was often accused of a false depiction of life, Aristotle dismisses this accusation as follows: “Homer perfectly taught others how to tell a lie: this is a wrong conclusion . .. Impossible, but probable should be preferred to what is possible, but incredible .. Thus, the inconsistencies in the Odyssey, in the story of the landing (on Ithaca), would obviously be unacceptable if it were composed by a bad poet; but here our poet smooths out the absurd with other virtues, making it pleasant.

Thus, Aristotle stands above any individual contradictions or inconsistencies in Homer, but treats him primarily from an aesthetic point of view, appreciating artistic realism in him, and, moreover, conscious realism, i.e. an image of what is "characteristic" of life, and [37] also of what lies in it in the form of "possibility" and what the poet unfolds into artistic reality. It seems to us that in antiquity there was no deeper and more sober attitude towards Homer than that which we find in Aristotle, and that this is basically the last word about the Homer of antiquity itself. Note, however, that Aristotle does not have the slightest inclination to allegorize; and this can be seen not only from the corresponding chapters of the Poetics, where he touches on Homer, but also from those numerous interpretations of Homer, which we can judge from numerous fragments from his essay "Difficult passages from Homer" (frg.