Early childhood social emotional learning

| ||||||||||||||||||

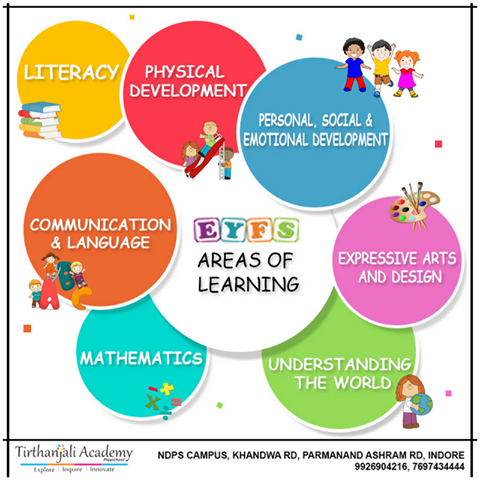

Social and Emotional Development in Early Learning Settings

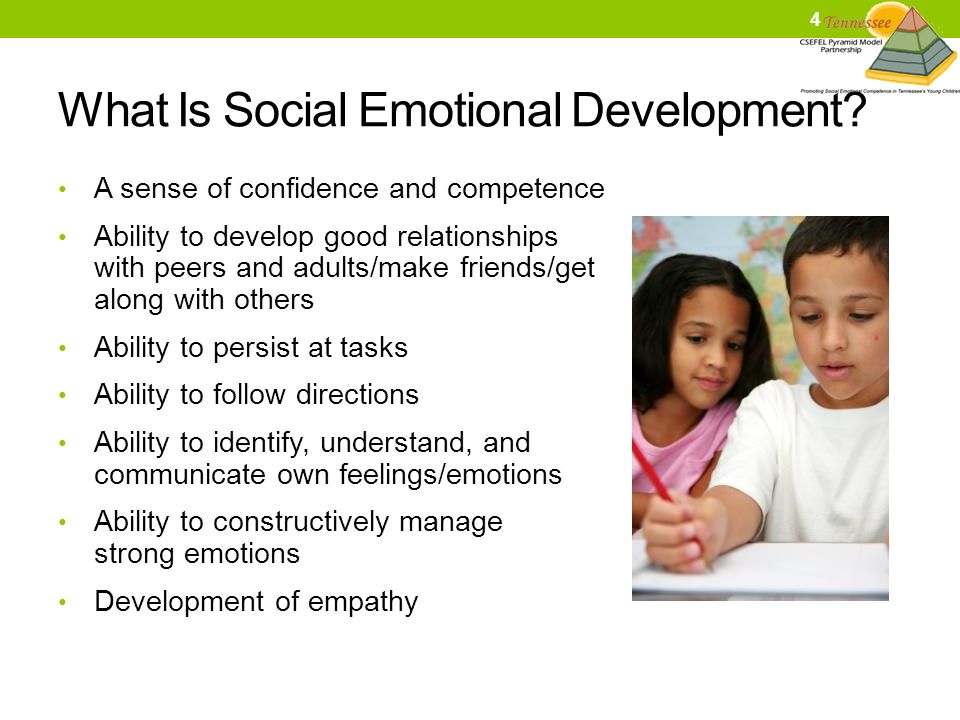

What Is Social and Emotional Development, and Why Does It Matter?

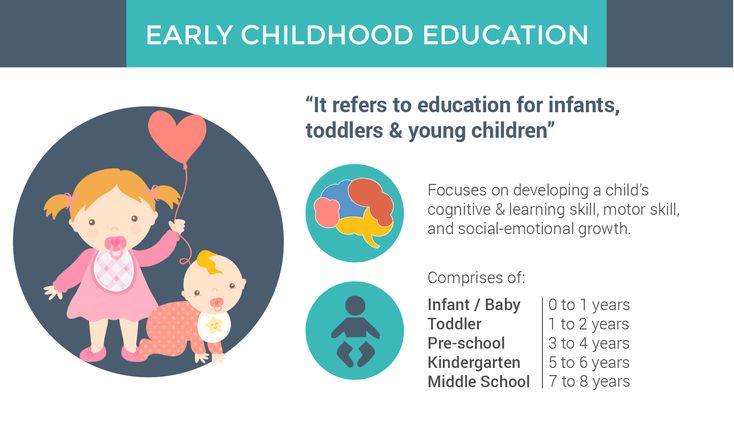

During their first few years of life, children’s brains are rapidly developing, as is their capacity to learn essential social and emotional skills. Social and emotional development in the early years, also referred to as early childhood mental health, refers to children’s emerging capacity to:

- Experience, regulate and express a range of emotions.

- Develop close, satisfying relationships with other children and adults.

- Actively explore their environment and learn.

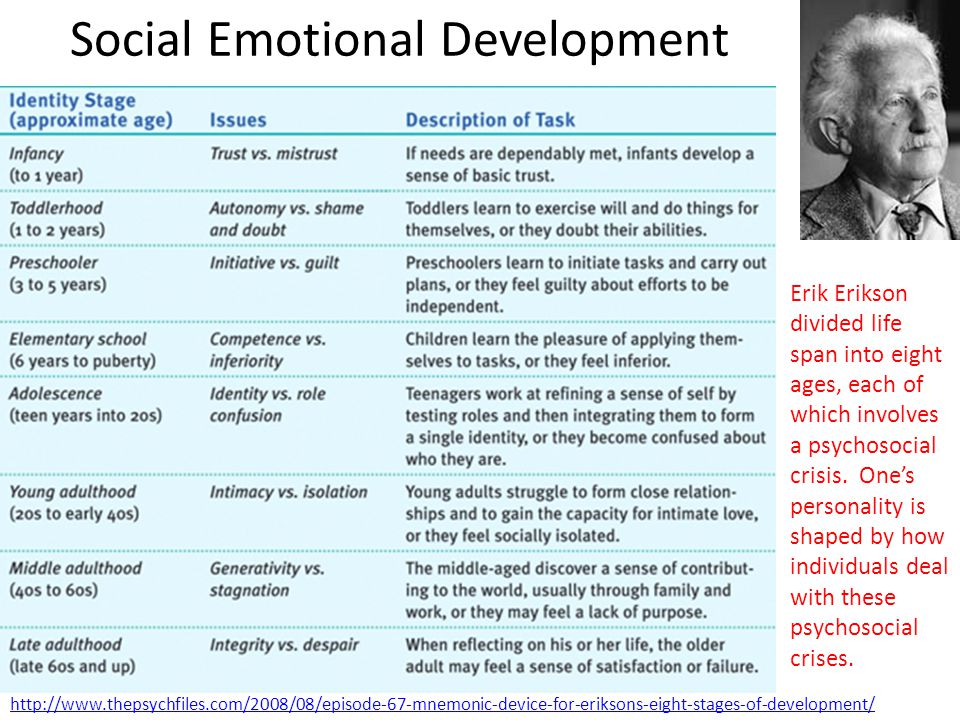

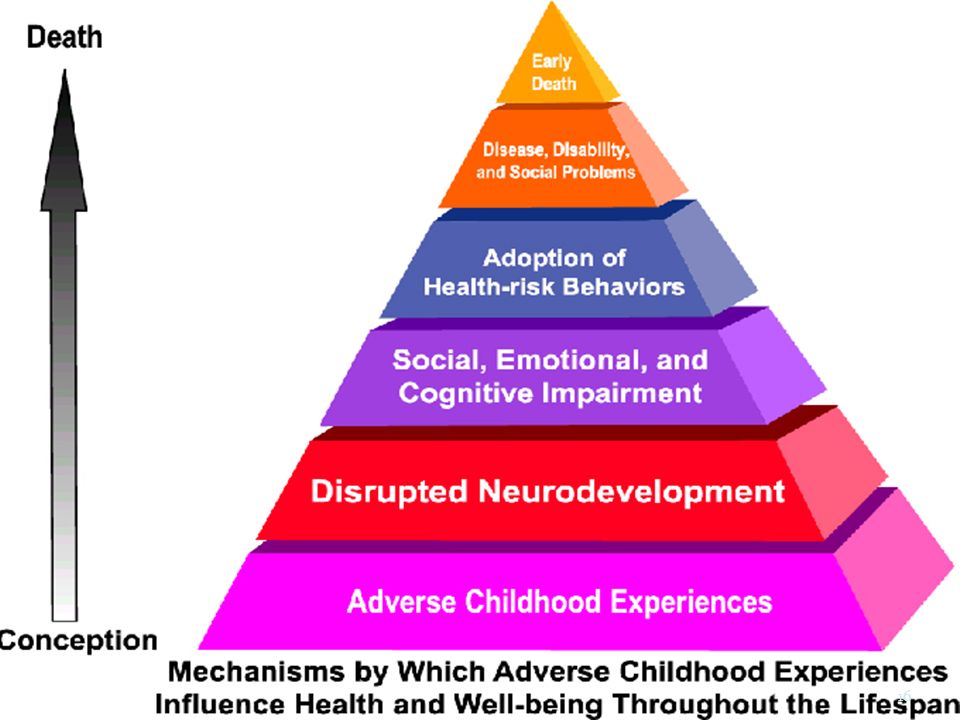

Social and emotional development is influenced by both biology and experiences. Together, genes and experiences shape the architecture of the brain: Genes provide “instructions” for our bodies while experiences affect how and whether the instructions are carried out. Children’s early experiences consist of interactions with caregivers—parents, other family members, child care providers and teachers—and their environment. Due to the rapid nature of brain development in early childhood, the quality of early experiences can lay either a strong or weak foundation, which will affect how children react and respond to the world around them for the rest of their life.

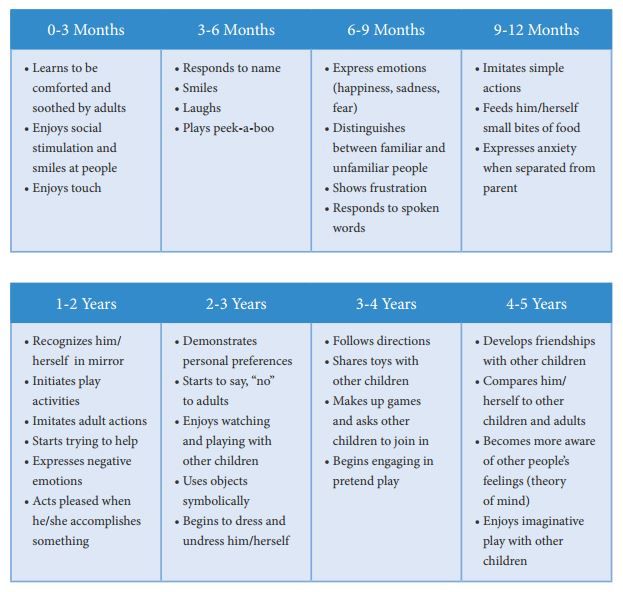

For most infants and young children, social and emotional development unfolds in predictable ways. They learn to develop close relationships with caregivers, soothe themselves when they are upset, share and play with others, and listen and follow directions. All these signs indicate positive early social and emotional development.

All these signs indicate positive early social and emotional development.

This is not the story for all children. Among those birth to age 5 who are exposed to biological, relationship-based, or environmental risk factors, at least 10% experience disruptions in their social and emotional development and consequently, mental health problems. For example, children exposed to abuse, neglect or other forms of trauma often respond biologically by producing high levels of cortisol—a stress hormone the body releases to cope with threatening situations. Prolonged periods of high stress in early childhood can cause permanent negative damage to the brain and other developing systems in the body. Children who experience toxic stress, defined as persistent activation of the stress response systems in the absence of a buffering and responsive caregiver, are at risk of poorer social, emotional and physical development. They risk serious mental health problems in childhood and later life.

Who Plays a Role in Supporting Healthy Social and Emotional Development?

Responsive and nurturing caregivers are essential for healthy social and emotional well-being. When parents or other primary caregivers respond to an infant’s babbles, cries and gestures with eye contact, touch and words (a process known as “serve and return”), new neural pathways are connected and strengthened. These connections support healthy physical and cognitive development. Positive relationships with a caregiver can also buffer against and reduce the disruptive effects of adversity for young children.

When parents or other primary caregivers respond to an infant’s babbles, cries and gestures with eye contact, touch and words (a process known as “serve and return”), new neural pathways are connected and strengthened. These connections support healthy physical and cognitive development. Positive relationships with a caregiver can also buffer against and reduce the disruptive effects of adversity for young children.

Social and emotional learning extends beyond parent-child relationships. Family, community and culture influence social and relationship norms, values, expectations and language, as well as beliefs and attitudes related to child-rearing. Other nonparental caregivers, family members and professionals also play a role in promoting healthy social and emotional development and treating mental health problems in young children. In addition, pediatricians and other health care providers help parents understand developmental stages, promote appropriate caregiver-child interactions, screen for developmental and behavioral issues, and refer families to additional services and supports.

Over 10 million children under the age of 5 are enrolled in early learning settings such as home- and center-based child care and prekindergarten classrooms. On average, young children spend more than 30 hours with nonparental caregivers in early learning settings each week. This makes the professionals who care for and teach young children important partners in supporting social and emotional development and school readiness.

What do mental health issues look like in young children?

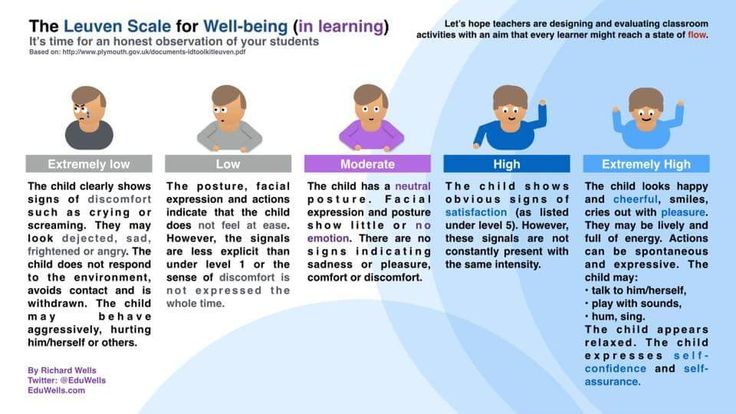

Young children can experience a range of mental health problems that can have a lifelong impact and be as severe as those experienced by adults. Diagnosing mental health problems in young children, however, can be challenging because they process and exhibit emotions differently than older children and adults, and changes in behavior can be temporary. Still, certain behaviors may warrant an evaluation from a mental health professional.

Birth to age 3:

- Chronic feeding or sleeping difficulties.

- Inconsolable irritability.

- Incessant crying with little ability to be consoled.

- Becoming extremely upset when left with another adult.

- Inability to adapt to new situations.

- Easily startled or alarmed by routine events.

- Inability to establish relationships with other children or adults.

- Excessive hitting, biting or pushing of other children.

- Flat effect or very withdrawn behavior.

Ages 3 to 5:

- Engages in compulsive activities.

- Throws wild, despairing tantrums.

- Withdrawn; shows little interest in social interaction.

- Displays repeated aggressive or impulsive behavior.

- Difficulty playing with others.

- Little or no communication; lack of language.

- Loss of earlier developmental achievements.

How Is Social and Emotional Development Supported in Early Learning Settings?

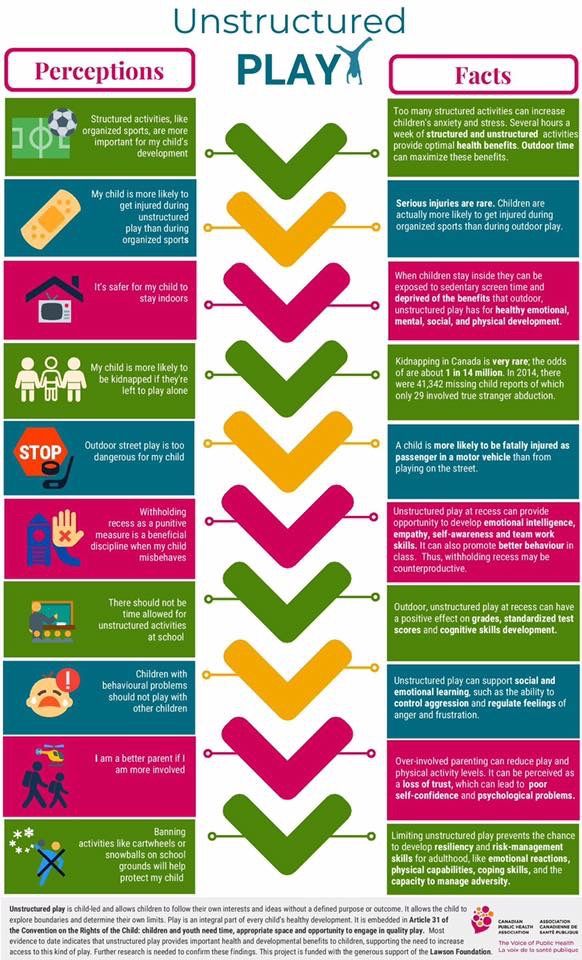

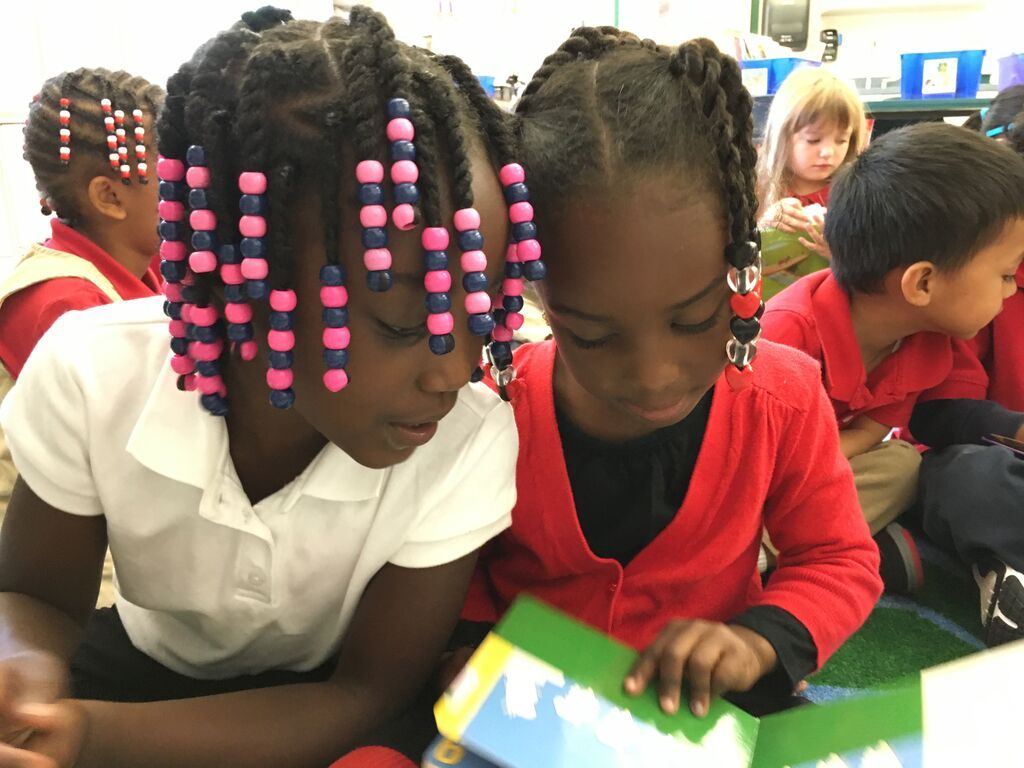

Early learning settings are rich with opportunities to build and practice social and emotional skills; however, the quality of these settings affects the degree to which a child’s social and emotional development is supported. In high-quality settings, children benefit from “frequent, warm and stimulating” interactions with caregivers who are attentive and able to individualize instruction based on children’s needs and strengths. Early educators in high-quality settings are trained in early childhood education and tend to be less controlling and restrictive in their approach to classroom management.

In high-quality settings, children benefit from “frequent, warm and stimulating” interactions with caregivers who are attentive and able to individualize instruction based on children’s needs and strengths. Early educators in high-quality settings are trained in early childhood education and tend to be less controlling and restrictive in their approach to classroom management.

Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation

Infant and early childhood mental health consultation (IECMHC) is an evidence-based strategy to support healthy social and emotional development and “prevent, identify, and reduce the impact of mental health problems among young children and their families,” according to the Center for Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation. IECMH consultants help build the capacity of the adults in young children’s lives to support healthy social and emotional development at home and in early learning settings. IECMH consultants have master’s degrees and are licensed mental health professionals who provide indirect, prevention-based services. They partner with families to assess concerns, assist with implementing positive behavioral supports, and connect families to other services and supports. Within early learning settings, IECMH consultants provide classroom-focused interventions that target all children, home-based interventions for more high-risk children, and referrals for those children who need more specialized services. Additionally, IECMH consultants support early care and education professionals by providing reflective supervision, coaching, training and case consultation.

They partner with families to assess concerns, assist with implementing positive behavioral supports, and connect families to other services and supports. Within early learning settings, IECMH consultants provide classroom-focused interventions that target all children, home-based interventions for more high-risk children, and referrals for those children who need more specialized services. Additionally, IECMH consultants support early care and education professionals by providing reflective supervision, coaching, training and case consultation.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) Center of Excellence for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation emphasizes the field’s role in promoting equity and reducing disparities in access to resources and outcomes for young children. Equity, according to SAMHSA’s IECMHC Toolbox, is “the quality of being fair, unbiased, and just.” Equity is essential to reducing disproportionalities among young children of color in suspensions and expulsions in early learning settings. IECMH consultants partner with early care and education professionals to “reflect on their own experiences, biases, and fears—and then move beyond them to see each young child as an individual within a unique family and community context.” There is growing evidence that access to IECMHC reduces the occurrence of suspensions and expulsions for young children.

IECMH consultants partner with early care and education professionals to “reflect on their own experiences, biases, and fears—and then move beyond them to see each young child as an individual within a unique family and community context.” There is growing evidence that access to IECMHC reduces the occurrence of suspensions and expulsions for young children.

Licensure and accreditation, well-trained caregivers, low staff-child ratios and parent involvement are generally considered to be fundamental to high-quality care and education. Such elements not only promote strong, secure relationships and positive interactions between caregiver and child, but also improve attention to children’s interest, problem-solving, language development, social skills and physical development.

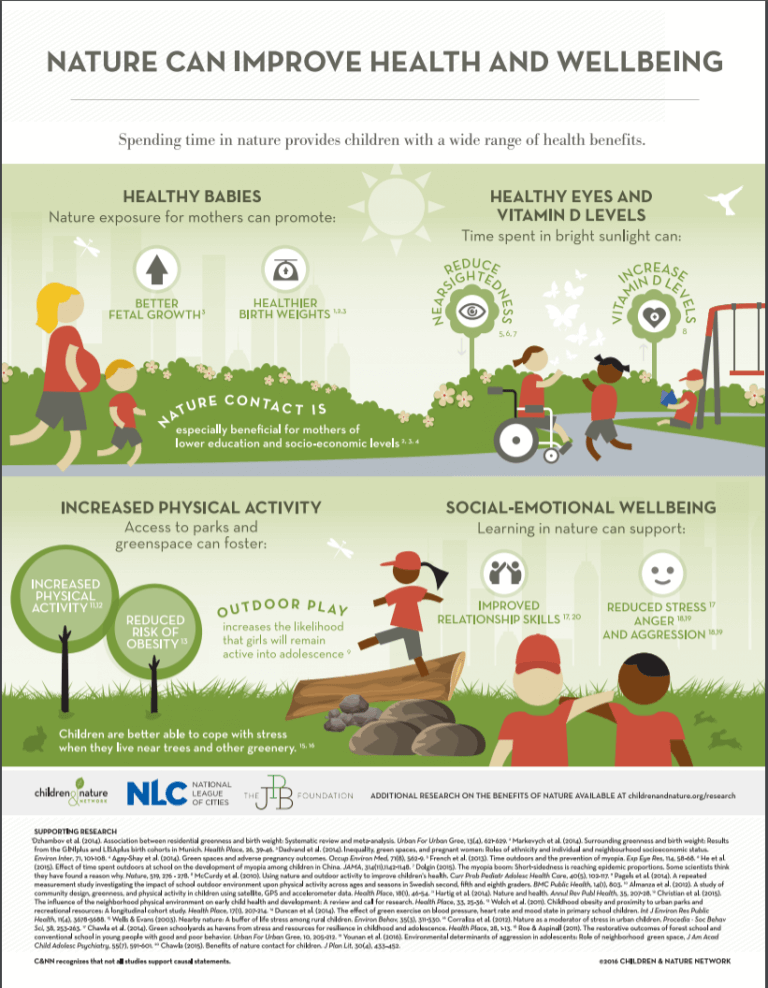

High-quality early learning opportunities can also reduce the risk of children experiencing poor mental health. Research shows it can mitigate the effects of poverty, maternal depression and other risk factors. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, high-quality child care helps build resilience among at-risk children, partly due to the relationships they form with caregivers. When children perceive at least one supportive adult in their life, they are less likely to experience toxic stress and suffer the detrimental effects of adverse experiences.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, high-quality child care helps build resilience among at-risk children, partly due to the relationships they form with caregivers. When children perceive at least one supportive adult in their life, they are less likely to experience toxic stress and suffer the detrimental effects of adverse experiences.

Well-trained early care and education professionals are critical to supporting social and emotional competence in young children. First and foremost, they build nurturing and responsive relationships with the children in their care and model respectful and appropriate behavior. They weave social and emotional skill-building into day-to-day activities and implement targeted curriculum and lessons with books, music, games and group discussions.

Effective early care and education professionals consider and support the individual needs of each child within the context of their family and culture. Head Start, the federally funded, locally implemented birth-to-5 program for low-income children, emphasizes that “children’s learning is enhanced when their culture is respected and reflected in all aspects” of an early learning program. Early childhood programs implementing culturally reflective policies and practices may look different depending on the setting, but at their core, they are learner-focused, promote a positive cultural and individual identity, and engage all children from unique cultural and/or linguistic backgrounds. Cultural awareness is key for early care and education professionals in forming strong relationships with children and families.

Early childhood programs implementing culturally reflective policies and practices may look different depending on the setting, but at their core, they are learner-focused, promote a positive cultural and individual identity, and engage all children from unique cultural and/or linguistic backgrounds. Cultural awareness is key for early care and education professionals in forming strong relationships with children and families.

Early care and education professionals are also critical to identifying children who face barriers to healthy social and emotional development and helping families obtain the support they need. They sometimes partner with an early childhood mental health consultant to address challenging behaviors and develop behavior support plans.

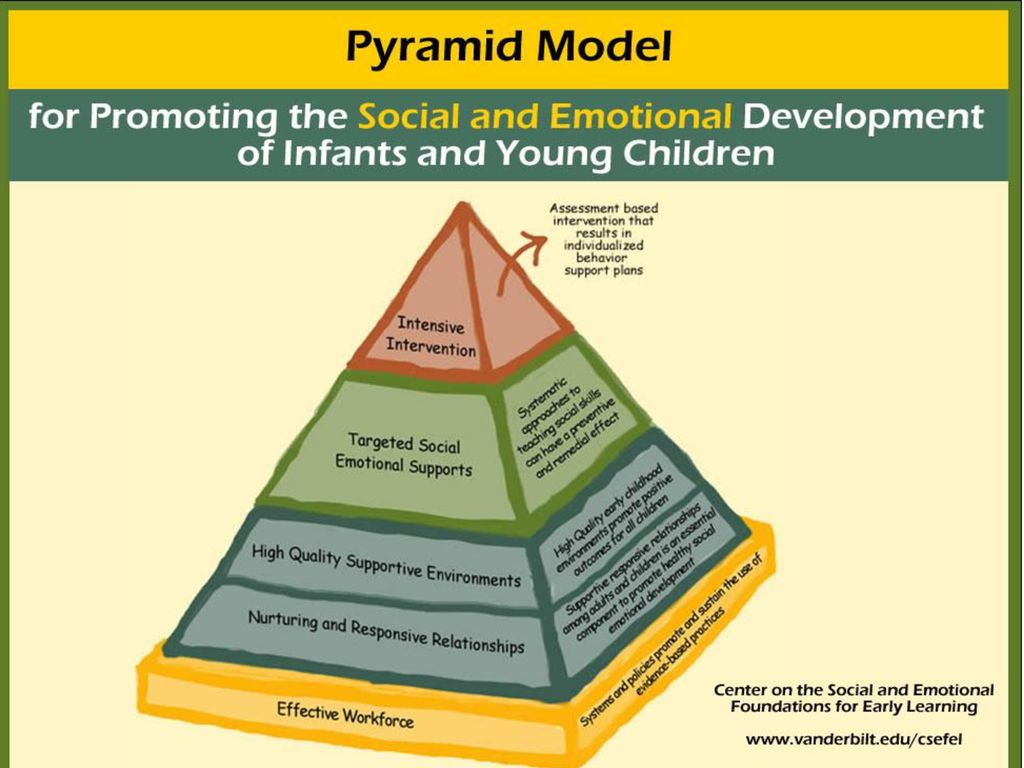

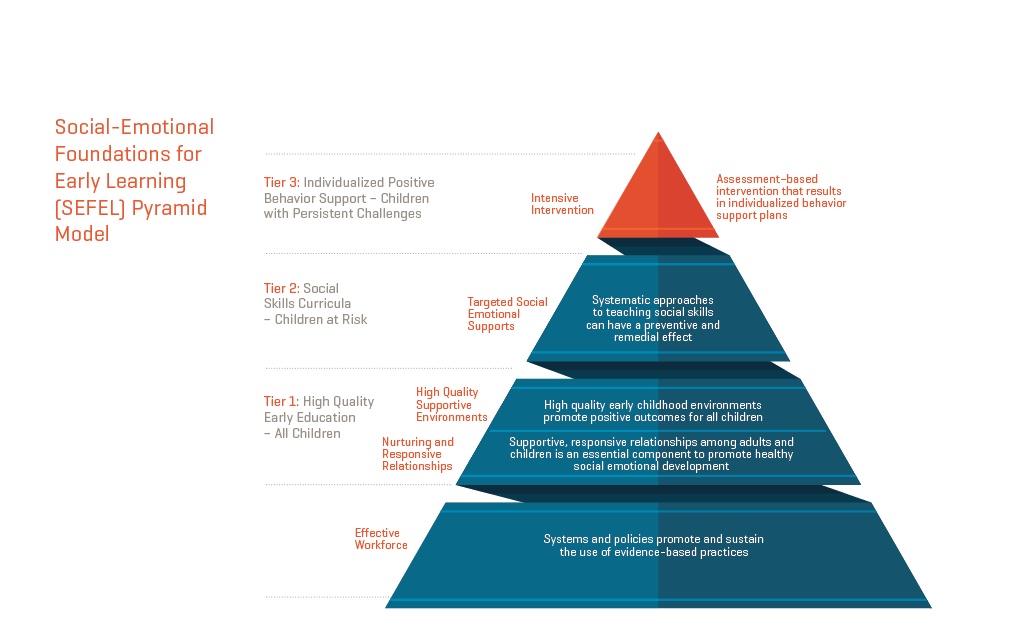

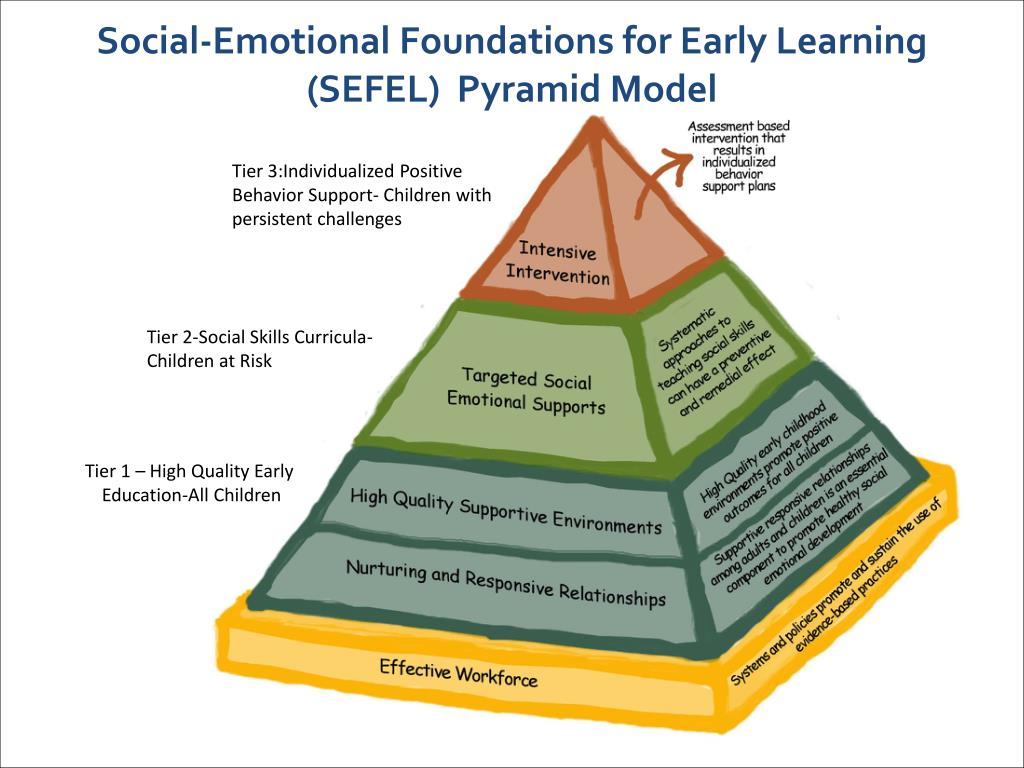

An increasing number of early learning settings are implementing Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support (PBIS) frameworks. The frameworks are designed to equip early care and education professionals with the skills and tools they need to support positive social and emotional development and address challenging behavior. A program-wide PBIS does not prescribe a specific curriculum. Instead, it includes a series of practices, interventions and implementation supports that are available across the system. One such framework, the Pyramid Model for Supporting Social Emotional Competence in Infants and Young Children (Pyramid Model), is specifically designed for programs serving infants and toddlers. Twenty-five states have established statewide coalitions and leadership teams to implement the Pyramid Model (often housed within a state’s human services or education department). The Pyramid Model organizes evidence-based practices into three progressively intensive tiers: universal supports for the wellness of all children, targeted services for those who need more support, and intensive services for those most in need. The model emphasizes how essential early care and education professionals are to the social and emotional well-being of young children by positioning “effective workforce” as the foundation.

A program-wide PBIS does not prescribe a specific curriculum. Instead, it includes a series of practices, interventions and implementation supports that are available across the system. One such framework, the Pyramid Model for Supporting Social Emotional Competence in Infants and Young Children (Pyramid Model), is specifically designed for programs serving infants and toddlers. Twenty-five states have established statewide coalitions and leadership teams to implement the Pyramid Model (often housed within a state’s human services or education department). The Pyramid Model organizes evidence-based practices into three progressively intensive tiers: universal supports for the wellness of all children, targeted services for those who need more support, and intensive services for those most in need. The model emphasizes how essential early care and education professionals are to the social and emotional well-being of young children by positioning “effective workforce” as the foundation.

How Prepared Are Early Care and Education Professionals to Care for Children With Challenging Behaviors?

Despite the importance of their role, many early care and education professionals report not feeling adequately trained to respond to challenging behaviors or to support children at risk of mental health issues. A national survey of the early care and education workforce revealed just 20% of respondents received training on supporting social and emotional growth in the past year. When asked what types of support would help them better address the needs of children with challenging behavior, professionals in Maine most frequently selected additional training (61%) and greater access to early childhood behavioral specialists (57%). In a similar survey in Virginia, respondents identified access to specialists (63%), additional supports for families (54%) and increased training for staff (52%) as necessary to improving outcomes for children.

A national survey of the early care and education workforce revealed just 20% of respondents received training on supporting social and emotional growth in the past year. When asked what types of support would help them better address the needs of children with challenging behavior, professionals in Maine most frequently selected additional training (61%) and greater access to early childhood behavioral specialists (57%). In a similar survey in Virginia, respondents identified access to specialists (63%), additional supports for families (54%) and increased training for staff (52%) as necessary to improving outcomes for children.

Implicit Bias in Early Learning Settings

In a study by researchers at Yale University, early care and education professionals were instructed to look for challenging behaviors in a video of an early learning classroom where none was present. Researchers used technology to track eye movements and found that when challenging behaviors were expected, teachers tended to observe the black children more closely, especially the black boys.

Another component of the study found that when teachers were provided additional information on a child’s family and background, and when the teacher’s race matched that of the child, teachers tended to lower the severity rating of the child’s behavior. Researchers concluded by calling for greater connections between early care and education professionals and parents, as well as increased training to address biases and increase empathy.

Survey participants in both Maine and Virginia were also asked about the effects of challenging behaviors in the classroom. Concerns included the ability to attend to other children and ensuring the safety and ability of other children to learn. Respondents also noted the negative effect challenging behaviors have on their own well-being.

Without adequate training and supports to handle these stressful situations, early care and education professionals—among whom depression is not uncommon—burn out and leave the profession. Extremely low wages further contribute to their stress. At an average annual salary of just over $22,000, nearly half of the early care and education workforce is enrolled in at least one public support program. These include the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Researchers have found that stress negatively affects early care and education professionals’ ability to provide positive, high-quality environments and is the primary reason they leave the field. Bringing the problem full circle, high turnover among early care and education professionals disrupts the relationships and attachments formed with the children they care for and is linked to poorer developmental outcomes for early learners.

At an average annual salary of just over $22,000, nearly half of the early care and education workforce is enrolled in at least one public support program. These include the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Researchers have found that stress negatively affects early care and education professionals’ ability to provide positive, high-quality environments and is the primary reason they leave the field. Bringing the problem full circle, high turnover among early care and education professionals disrupts the relationships and attachments formed with the children they care for and is linked to poorer developmental outcomes for early learners.

Furthermore, early care and education professionals who lack training may be unprepared to distinguish concerning behaviors from those that are developmentally appropriate. Misinterpreting or mischaracterizing behaviors may lead to more punitive discipline and failure to provide appropriate supports. Underprepared professionals are more likely to over-identify children, especially children of color, for special education, disciplinary action and expulsions. Suspensions and expulsions are more likely to occur in early learning settings that have high student-adult ratios, private ownership, extended hours, limited access to early childhood behavioral specialists, and teachers who report high levels of stress.

Underprepared professionals are more likely to over-identify children, especially children of color, for special education, disciplinary action and expulsions. Suspensions and expulsions are more likely to occur in early learning settings that have high student-adult ratios, private ownership, extended hours, limited access to early childhood behavioral specialists, and teachers who report high levels of stress.

Suspension and expulsion in early learning settings

Data collected in recent years by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights has shined a spotlight on how common suspensions and expulsions are in early learning settings. In fact, expulsion rates among preschoolers are three times higher than those of K-12 students. Stark disparities in suspension and expulsion rates among young children based on race and gender led researchers to question the effect of implicit bias, or the “automatic and unconscious stereotypes that drive people to behave and make decisions in certain ways. Black children, who comprise just 19% of preschool enrollment, make up 47% of preschoolers who are suspended. Research shows students of color are more harshly disciplined for the same behaviors exhibited by their white peers. Furthermore, 75% of expelled preschoolers are boys, with black boys being suspended or expelled the most often. The consequences for young children who are suspended or expelled can be significant and long-lasting. The same children are more likely to be suspended or expelled again in later years and to drop out of high school, fail a grade or be incarcerated.

Black children, who comprise just 19% of preschool enrollment, make up 47% of preschoolers who are suspended. Research shows students of color are more harshly disciplined for the same behaviors exhibited by their white peers. Furthermore, 75% of expelled preschoolers are boys, with black boys being suspended or expelled the most often. The consequences for young children who are suspended or expelled can be significant and long-lasting. The same children are more likely to be suspended or expelled again in later years and to drop out of high school, fail a grade or be incarcerated.

In 2016, U.S. departments of Health and Human Services and Education issued a policy statement and recommendations aimed at preventing and severely limiting suspensions and expulsions of young children. The departments recommended that early learning programs take the following steps:

- Improve the workforce’s skill set and capacity to support social and emotional development, address challenging behaviors appropriately, and form supportive and nurturing relationships with children and their families.

- Provide training to deepen the workforce’s understanding of cultures and diversity, practice self-reflective strategies and correct biases.

- Increase access to behavioral specialists (including IEMCH consultants).

- Promote the health and well-being of the workforce with reasonable work hours, breaks and access to supports, such as social or mental health services.

The policy statement also made recommendations directly to states, including enacting state policies severely limiting the use of suspensions and expulsions across all early learning settings, collecting data on the use of exclusionary discipline and setting goals for its reduction. It also recommended investing in workforce training and implementing policies to increase quality in early learning settings.

How Are State Policymakers Promoting Healthy Social and Emotional Development in Early Learners?

Well-trained and supported early care and education professionals are critical to reducing the occurrence of suspensions and expulsions in the early years, providing high-quality early learning experiences and supporting social and emotional well-being in young children. Below are actions policymakers across the country are taking to help children, families and early care and education professionals acquire the skills and resources they need to thrive.

Below are actions policymakers across the country are taking to help children, families and early care and education professionals acquire the skills and resources they need to thrive.

Investing in targeted training and professional development for early care and education professionals

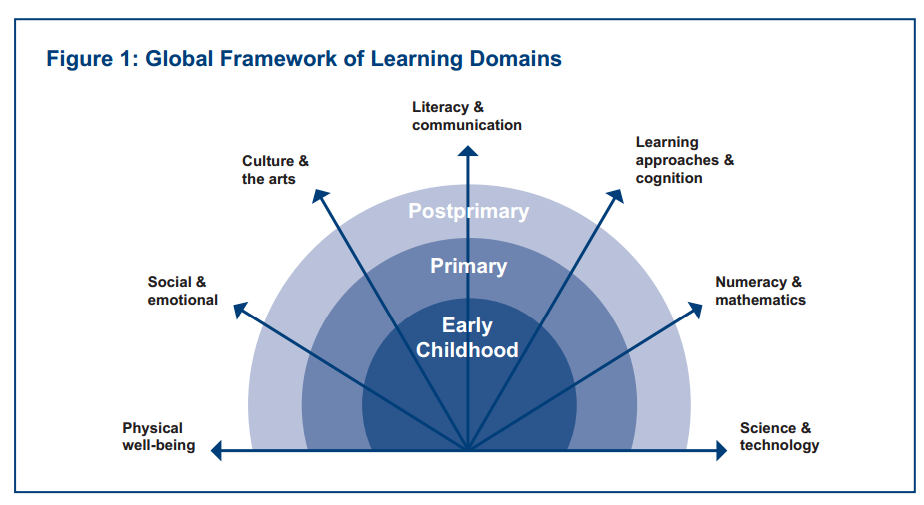

- Most states include social and emotional development in their Early Learning Guidelines for early care and education professionals.

- California provides training and coaching on trauma-informed care for in-home child care providers serving children in the foster care system.

- Alaska requires programs at levels 4 and 5 in the state’s Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS) to participate in trainings specific to trauma and adversity.

- Vermont’s Early Multi-Tiered System of Supports framework includes evidence-based practices and trainings and is embedded in the state’s QRIS.

Addressing compensation and workplace conditions in early learning settings

- Five states fund wage supplements through the Child Care WAGE$ Program, a stipend available through the Child Care Services Association, in which early care and education professionals are placed on a “salary supplement scale.

” The scale rewards workers for obtaining higher levels of education and for remaining in the same child care setting. Wisconsin and Georgia have their own wage supplement programs.

” The scale rewards workers for obtaining higher levels of education and for remaining in the same child care setting. Wisconsin and Georgia have their own wage supplement programs. - Colorado, Louisiana and Nebraska passed legislation to provide tax credits for early care and education professionals who meet certain education or training requirements.

- Twenty-two states include salary scales and/or benefits (e.g., paid leave and health insurance) as a quality indicator for center-based child care providers in their QRIS.

- Thirteen states include paid time for professional development as a marker of quality in their state’s QRIS for center-based child care providers.

BehaviorHelp in Arkansas

In 2016, Arkansas extended its prohibition of suspension and expulsion in state-funded prekindergarten classrooms to include nearly 1,000 child care providers serving families with child care subsidies.

To support early care and education professionals with implementing the new policy, the state established BehaviorHelp, a program that provides individual support for addressing challenging behaviors in young children. Early care and education professionals, parents and child welfare case workers complete an online form detailing their issue. Behavioral health specialists then follow up with a phone consultation, classroom observation, training related to individual support plans for educators and parents, and referrals to additional services.

Early care and education professionals, parents and child welfare case workers complete an online form detailing their issue. Behavioral health specialists then follow up with a phone consultation, classroom observation, training related to individual support plans for educators and parents, and referrals to additional services.

Data collected during the program’s first two years revealed that over half of the children exhibiting challenging behaviors had experienced difficult or traumatic events, such as abuse or neglect, divorce or parent incarceration. A survey of users found that 81% felt better able to address their concerns because of the support they received from BehaviorHelp. Users also reported a significant decline in the frequency of challenging behaviors.

Improving access to infant and early childhood mental health consultation

- Louisiana and North Carolina provide access to early childhood mental health consultants for child care providers through their state’s QRIS.

- Virginia funds a full-time coordinator to support a comprehensive IECMH system, including a series of trainings and an IECMH endorsement for practitioners.

- Connecticut’s statewide IECMH program provides universal access to consultants for all early childhood programs in the state.

- Early care and education professionals in Arkansas (see text box on page 7) and Ohio can receive individualized consultations from an early childhood behavioral specialist through a hotline. Arizona’s Birth to Five hotline is available to parents as well as early care and education professionals.

Reducing suspensions and expulsions in early learning settings

- Sixteen states and the District of Columbia limit or prohibit the use of suspensions and expulsions in lower grades, including prekindergarten classrooms.

- Legislators in Washington directed its Department of Children, Youth, and Families to develop a five-year strategy to expand training and awareness in trauma identification, provide positive behavior supports in early settings, and reduce the use of exclusionary discipline by 50%.

- Colorado’s state child care rules require providers to “outline how decisions are made and what steps are taken prior to a suspension, expulsion, or request to withdraw a child from care.” The rules further require that child care providers adopt policies to 1) provide individualized social and emotional intervention supports for children who need them, 2) implement a team-based positive behavior support plan aimed at reducing challenging behavior, suspensions and expulsions, and 3) improve access to early childhood mental health consultants.

Learning about the mental health needs of young children

- Georgia lawmakers established the Infant and Toddler Social-Emotional Health Study Committee to study the availability of services and make recommendations.

- The Oklahoma Legislature established a task force on trauma-informed care to recommend options and strategies for implementing a coordinated approach to preventing trauma in children, as well as interventions for children and families who are at risk of experiencing trauma.

Conclusion | Additional Resources

Early childhood is a critical window of development for learning social and emotional skills. The quality of experiences and relationships during this time can have life-long implications. For children who face barriers to healthy development, the stakes are even higher. Nurturing the social and emotional development of all young children, so they are ready to succeed in school and beyond, depends on strong partnerships between parents and their out-of-home caregivers. State policymakers are taking steps to ensure young children are supported in early learning settings by investing in the training and well-being of the early care and education workforce, restricting the use of suspensions and expulsions, improving access to early childhood mental health specialists, and exploring additional policies to support the mental health needs of young children and their families.

Additional Resources

- "School Discipline in Preschool Through Grade 3," NCSL LegisBrief

- "Building a Comprehensive State Policy Strategy to Prevent Expulsion from Early Learning Settings,” Administration of Children and Families, Office of Child Care

- Center for Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation

- "Social and Emotional Learning," NCSL

Social and emotional development of preschoolers | Modern educational processes in the preschool educational institution

Conference: Modern educational processes in the preschool educational institution

Author: Sokolova Anna Alexandrovna

Organization: MKDOU No. 46

46

Location: Novosibirsk region, Novosibirsk

We can be sad and laugh, get angry and express their feelings to some degree of acceptable aggression. However, we are often frightened by this expression of emotions in our children. But they, like no one else, have the right to be happy and sad, offended and angry.

The emotional development of young children and older children is a very important aspect in education. It has been scientifically proven that children who do not know how to correctly express their emotions and determine the emotional background of another person are more depressed and closed from the outside world, this leads to serious problems - from lagging behind in the learning process to real social isolation in which they fall. That is why the emotional development of the child is no less important than the intellectual.

Why is it necessary to develop socially and emotionally? The sooner the child learns to understand the state of others, the easier it will be for him to get used to any team, to find a common language with peers and adults.

Feelings and emotions play a very important role in the life of every person, especially at an early age. The early preschool period is the time when the multi-color palette of feelings is explored, and the child learns to recognize and correctly show his experiences. At this stage, the child develops new feelings for him: empathy, anticipation, empathy. The development of the child's emotional sphere occurs gradually and is no less important than physical or mental development. They only thank positive emotions, the ability to remember information and speak improves.

At first, the child communicates with others only through the manifestation of emotions. Therefore, for the normal emotional development of the baby, a variety of emotions are needed. Children perceive the world very emotionally. The explosion of experiences is short and can be very stormy, and the child is not yet able to control his emotions. The emotional reactions of the child are unconscious and unstable - the baby may cry, and after a few seconds suddenly start laughing. If a child grows up in a friendly atmosphere, then he is almost always cheerful. This state is extremely important for the formation of the personality of the baby, the basis of his attitude towards others. If the emotional sphere of the child develops naturally and steadily, he has many chances to grow up healthy and successful.

If a child grows up in a friendly atmosphere, then he is almost always cheerful. This state is extremely important for the formation of the personality of the baby, the basis of his attitude towards others. If the emotional sphere of the child develops naturally and steadily, he has many chances to grow up healthy and successful.

Children are very impressionable, emotional arousal has a strong influence on the whole behavior of the baby. In young children, “emotional contagion” can be observed: if one of them starts to cry, then the others immediately support him.

Emotions of children of the second year of life are closely connected with objective activity, its success or failure. They are aimed at the objects to be acted upon, at the situation as a whole, at the actions of the child and the adult himself, at the result obtained independently, at play moments. Interest in the object, combined with the inability to act, causes displeasure, anger, anger, grief. Negative reactions indicate that the baby's mode of action has not yet been formed. So, the child needs help, suggest how to act. Bright, positive emotions, expressed in smiles, exclamations, frequent appeals to an adult, indicate that the child has mastered the action and wants to get the approval of an adult with every independent act. Activity taking place against a calmly concentrated background indicates the mastery of this type of activity. Positive emotions in many cases reflect the level of satisfaction of needs - cognitive, motor. Experiences are now associated precisely with the skills and results characteristic of a person's independence. Therefore, we can say that there is a consistent social development of emotions. In the second year of life, when a peer approaches, the child feels anxiety, can interrupt his studies and rush to the protection of his mother. Communication with other children in early childhood usually only appears and does not yet become complete. By the end of the second year of life, the baby gets satisfaction from the game. There are experiences associated not only with actions, but also with the plot.

So, the child needs help, suggest how to act. Bright, positive emotions, expressed in smiles, exclamations, frequent appeals to an adult, indicate that the child has mastered the action and wants to get the approval of an adult with every independent act. Activity taking place against a calmly concentrated background indicates the mastery of this type of activity. Positive emotions in many cases reflect the level of satisfaction of needs - cognitive, motor. Experiences are now associated precisely with the skills and results characteristic of a person's independence. Therefore, we can say that there is a consistent social development of emotions. In the second year of life, when a peer approaches, the child feels anxiety, can interrupt his studies and rush to the protection of his mother. Communication with other children in early childhood usually only appears and does not yet become complete. By the end of the second year of life, the baby gets satisfaction from the game. There are experiences associated not only with actions, but also with the plot. The child rejoices both in the action itself and in the fact that it takes place in the game organized by him.

The child rejoices both in the action itself and in the fact that it takes place in the game organized by him.

The development of the child's emotional need sphere is closely connected with self-awareness emerging at this time. By the age of three, the pronoun "I" appears. At the same time, the child also has a primary self-esteem - the realization not only of his “I”, but that “I am good”, “I am very good”, “I am good and no more”. It can hardly be called self-esteem in the proper sense of the word, as it is based on the child's need for emotional security and acceptance. The development of the emotional-need sphere depends on the nature of the child's communication with adults. In communication with close adults who help the child to explore the world of "adult" objects, motives for cooperation prevail, although purely emotional communication is also preserved, which is necessary at all age stages. In addition to unconditional love, emotional warmth, the child expects adults to be directly involved in all their affairs, to jointly solve any problem, whether it is the development of cutlery or the construction of a tower of cubes. It is around such joint actions that new forms of communication with adults are developed for the child.

It is around such joint actions that new forms of communication with adults are developed for the child.

The desires of a young child are unstable and quickly transient, he cannot control and restrain them; they are limited only by punishments and rewards from adults. All desires have the same strength, since in early childhood there is no subordination of motives. This is easy to observe in a situation of choice. If a child of 2-3 years old is asked to choose one of several new toys, he will consider and sort through them for a long time. Then, after all, he will choose one, but after the next request - to go with her to another room - he will again begin to hesitate. Putting the toy in its place, he will go through the rest until he is taken away from these equally attractive things.

By the age of 3, the child's experiences are inextricably linked with the plot side of the game. He develops the story. The saucepan fell: “Oh! Spilled!” - the kid exclaims and wipes an imaginary puddle with a rag. The emotional response to game events shows not only the high development of the game, but also its emotional significance for the child. At the age of three, the child is already playing calmly next to another child, but the moments of the general game are short-lived, and so far there can be no talk of the rules of the game. Best of all, children of this age succeed in joint jumping on the bed. If a small child attends a nursery, he is forced to communicate more closely with peers, and gains more experience in this regard than those who are brought up at home. But "nursery" children are not spared age-related difficulties in communication. They can be aggressive - push, hit another child, especially if he somehow infringed on their interests. A young child, communicating with children, always proceeds from his own desires, completely ignoring the desires of another. He is self-centered and not only does not understand another child, but also does not know how to empathize with him. The emotional mechanism of empathy (sympathy in a difficult situation and joint joy in luck or in a game) will appear later, in preschool childhood.

The emotional response to game events shows not only the high development of the game, but also its emotional significance for the child. At the age of three, the child is already playing calmly next to another child, but the moments of the general game are short-lived, and so far there can be no talk of the rules of the game. Best of all, children of this age succeed in joint jumping on the bed. If a small child attends a nursery, he is forced to communicate more closely with peers, and gains more experience in this regard than those who are brought up at home. But "nursery" children are not spared age-related difficulties in communication. They can be aggressive - push, hit another child, especially if he somehow infringed on their interests. A young child, communicating with children, always proceeds from his own desires, completely ignoring the desires of another. He is self-centered and not only does not understand another child, but also does not know how to empathize with him. The emotional mechanism of empathy (sympathy in a difficult situation and joint joy in luck or in a game) will appear later, in preschool childhood. Nevertheless, communication with peers is useful and also contributes to the emotional development of the child, although not to the same extent as communication with adults.

Nevertheless, communication with peers is useful and also contributes to the emotional development of the child, although not to the same extent as communication with adults.

Higher feelings develop at an early age, the prerequisites for which were formed in infancy. Also, by the age of 3, aesthetic feelings are clearly manifested. The kid experiences the nature of music: cheerful and sad, smooth and cheerful. He rejoices in ornaments, beautiful clothes, flowering plants. Delight, like in a baby, is everything bright and brilliant, but the child learns to distinguish beautiful from ugly, harmonious from disharmonious. Based on the feeling of surprise, which was observed even in an infant, elementary curiosity arises in early childhood. Questions start to emerge. New feelings arise in relation to peers: rivalry, elements of envy, jealousy. The toddler seeks to usurp the attention of an adult and protests when it is shared between children or is given to another child.

At the end of this period, when approaching the crisis of 3 years, the child may experience affective reactions to the difficulties he is facing. If a child, when trying to do something on his own, did not succeed and there was no adult nearby, an emotional outburst is possible. These affective outbursts are best extinguished when adults react calmly enough to them. The excessive attention of adults to such manifestations acts as a positive reinforcement for the child, and he learns that pleasant moments in communication with adults come after his tears. If the child is really upset, it is enough to show him his favorite or new toy, offer to do something interesting with him. In a child, one desire is easily replaced by another, he easily switches and is happy to do a new thing.

If a child, when trying to do something on his own, did not succeed and there was no adult nearby, an emotional outburst is possible. These affective outbursts are best extinguished when adults react calmly enough to them. The excessive attention of adults to such manifestations acts as a positive reinforcement for the child, and he learns that pleasant moments in communication with adults come after his tears. If the child is really upset, it is enough to show him his favorite or new toy, offer to do something interesting with him. In a child, one desire is easily replaced by another, he easily switches and is happy to do a new thing.

The emotional development of young children is especially necessary during the crisis of 3 years of age. During this period, the child has elements of rebellious behavior, a desire to manipulate parents, jealousy towards the younger (older) child, aggression towards others. All this suggests that the baby is changing his attitude, both to himself and to others. You need to calmly and respectfully treat the child, his requests, without showing aggression, explain and show by example how to behave in a difficult situation. The emotional sphere is an important component in the development of preschoolers and younger schoolchildren, since no communication, interaction will be effective if its participants are not able, firstly, to "read" the emotional state of another, and secondly, to manage their emotions. Understanding your emotions and feelings is also an important point in the formation of the personality of a growing person. Emotional well-being provides high self-esteem, formed self-control, orientation towards success in achieving goals, emotional comfort in the family and outside the family. It is emotional well-being that is the most capacious concept for determining the success of a child's development. By the age of 3, personal actions and the consciousness of “I myself” appear - the central neoplasm of this period. There is a purely emotional inflated self-esteem.

You need to calmly and respectfully treat the child, his requests, without showing aggression, explain and show by example how to behave in a difficult situation. The emotional sphere is an important component in the development of preschoolers and younger schoolchildren, since no communication, interaction will be effective if its participants are not able, firstly, to "read" the emotional state of another, and secondly, to manage their emotions. Understanding your emotions and feelings is also an important point in the formation of the personality of a growing person. Emotional well-being provides high self-esteem, formed self-control, orientation towards success in achieving goals, emotional comfort in the family and outside the family. It is emotional well-being that is the most capacious concept for determining the success of a child's development. By the age of 3, personal actions and the consciousness of “I myself” appear - the central neoplasm of this period. There is a purely emotional inflated self-esteem. At the age of 3, the child's behavior begins to be motivated not only by the content of the situation in which he is immersed, but also by relationships with other people. Although his behavior remains impulsive, there are actions associated not with immediate momentary desires, but with the manifestation of the "I" of the child. The main reasons for the occurrence of deviations in the emotional development of a child of this age can be frequent changes in the habitual stereotype of behavior, daily routine, lack of necessary conditions for playing and independent activity, incorrect educational methods (creating a one-sided emotional attachment, lack of a unified approach to the child, etc.) .

At the age of 3, the child's behavior begins to be motivated not only by the content of the situation in which he is immersed, but also by relationships with other people. Although his behavior remains impulsive, there are actions associated not with immediate momentary desires, but with the manifestation of the "I" of the child. The main reasons for the occurrence of deviations in the emotional development of a child of this age can be frequent changes in the habitual stereotype of behavior, daily routine, lack of necessary conditions for playing and independent activity, incorrect educational methods (creating a one-sided emotional attachment, lack of a unified approach to the child, etc.) .

The emergence of an emotional reaction to praise creates conditions for the development of self-esteem and a sense of pride. At first, feelings of pride are unstable and arise only with a direct assessment of the child by an adult. As positive assessments are repeated, aimed at the same qualities, pride becomes stable and constant. There is a need to always receive and maintain a positive assessment of an adult that satisfies the baby's pride, which indicates the emergence of the first rudiments of self-esteem. With its appearance, the child's reactions to external evaluation become more complicated. When a new assessment contradicts the old one, the child's resistance arises. Therefore, for a long time he continues to be proud of the quality that was positively assessed in the past, despite the negative assessment of it in the present. Under the influence of the new evaluation, if it persists long enough, the child's pride is rebuilt accordingly. And the feeling caused by an episodic, short-term assessment is unstable. Under the influence of positive and negative assessments on the baby, a feeling of shame arises, associated with all the past experience of the child's interaction with others. It is a manifestation of children's pride, the emerging sense of pride and dignity. The basis of the feeling of shame is the formation of ideas about positively and negatively evaluated patterns of behavior.

There is a need to always receive and maintain a positive assessment of an adult that satisfies the baby's pride, which indicates the emergence of the first rudiments of self-esteem. With its appearance, the child's reactions to external evaluation become more complicated. When a new assessment contradicts the old one, the child's resistance arises. Therefore, for a long time he continues to be proud of the quality that was positively assessed in the past, despite the negative assessment of it in the present. Under the influence of the new evaluation, if it persists long enough, the child's pride is rebuilt accordingly. And the feeling caused by an episodic, short-term assessment is unstable. Under the influence of positive and negative assessments on the baby, a feeling of shame arises, associated with all the past experience of the child's interaction with others. It is a manifestation of children's pride, the emerging sense of pride and dignity. The basis of the feeling of shame is the formation of ideas about positively and negatively evaluated patterns of behavior. It occurs in a pre-preschooler when his behavior deviates from a positively evaluated sample in a negative direction. At the same time, the child himself feels this deviation and perceives such a situation as a loss of the positive opinion of adults, a decrease in his dignity.

It occurs in a pre-preschooler when his behavior deviates from a positively evaluated sample in a negative direction. At the same time, the child himself feels this deviation and perceives such a situation as a loss of the positive opinion of adults, a decrease in his dignity.

When a child enters kindergarten, a new stage of his emotional development begins. A powerful stimulus for the manifestation of emotions is the children's team, as well as various types of joint activities organized by the educator with peers (games, educational activities, walks), where the child acquires emotional experience in communicating with other people and develops a certain attitude towards himself.

Knowledge and ideas about the norms of behavior, supplemented by an emotional attitude towards these norms, turn into convictions and become internal motivators

children's activities and behaviour.

Adults contribute to the development of a child's positive attitude towards other people, cultivate respect and tolerance regardless of social origin, race and nationality, language, religion, gender, age, personal and behavioral identity (appearance, physical disabilities). Adults help to understand that all people are different, it is necessary to respect the self-esteem of other people, take into account their opinion, desires, views in communication, play, joint activities. Encourage manifestations of benevolent attention, sympathy, empathy. It is important that the child has the desire and ability to help, support another person.

Adults help to understand that all people are different, it is necessary to respect the self-esteem of other people, take into account their opinion, desires, views in communication, play, joint activities. Encourage manifestations of benevolent attention, sympathy, empathy. It is important that the child has the desire and ability to help, support another person.

Adults create opportunities for introducing children to the values of cooperation with other people, helping to realize the need for people in each other. To do this, children should be encouraged to play together, organize their joint activities aimed at creating a common product. In the process of staging a performance, constructing a common building, making an artistic panel together with peers and adults, etc., the child acquires the ability to set common goals, plan joint work, coordinate and control his desires, coordinate opinions and actions. Adults contribute to the development in children of a sense of responsibility for another person, a common cause, a given word.

Adults pay special attention to the development of the child's communicative competence. Help children to recognize the emotional experiences and states of others - joy, grief, fear, bad and good mood, etc .; express their feelings and experiences. To do this, adults, together with children, discuss various situations from life, stories, fairy tales, poems, look at pictures, drawing the attention of children to the feelings, states, actions of other people; they organize theatrical performances and dramatization games, during which the child learns to distinguish and convey the moods of the characters portrayed, empathizes with them, and receives patterns of moral behavior.

Adults contribute to the development of social skills in children: they help to master various ways of resolving conflict situations, to negotiate, to follow the order, to establish new contacts. An important aspect of the social development of a child in preschool age is the development of elementary rules of etiquette (greet, thank, behave at the table, etc. ). Children should be introduced to the elementary rules of safe behavior at home, on the street (know who to contact if you are lost on the street, give your name, home address, etc.).

). Children should be introduced to the elementary rules of safe behavior at home, on the street (know who to contact if you are lost on the street, give your name, home address, etc.).

It is important to create conditions for the development of a careful, responsible attitude of the child to the environment, the man-made world, take care of animals and plants, feed the birds, keep clean, take care of toys, books, etc.

Educators, parents - the first and most important teachers of the child. His first school - your home - will have a huge impact on what he considers important in life.

“Years of miracles” is what scientists call the first five years of a child's life. The emotional attitude towards people's life laid down at this time and the presence or absence of incentives for intellectual development leave an indelible imprint on all further behavior and way of thinking of a person.

Each person should be able to listen to another, perceive and strive to understand him. How a person feels another, can influence him without offending or causing aggression, depends on his future success in interpersonal communication. Very few of us know how to really listen to other people well, to be receptive to the nuances in their behavior. It takes a certain skill and a certain amount of effort to combine communication with attentive observation and listening. Equally important are the ability to listen and understand oneself, that is, to be aware of one's feelings and actions at various moments of communication with others.

How a person feels another, can influence him without offending or causing aggression, depends on his future success in interpersonal communication. Very few of us know how to really listen to other people well, to be receptive to the nuances in their behavior. It takes a certain skill and a certain amount of effort to combine communication with attentive observation and listening. Equally important are the ability to listen and understand oneself, that is, to be aware of one's feelings and actions at various moments of communication with others.

And all this has to be learned. Skill does not come to a person by itself; it is acquired at the cost of effort spent on learning. However, you, as the first teachers of the child, can greatly help him in this difficult work if you begin to instill communication skills at a very early age.

References:

1. Izard K.E. Psychology of emotions / Perev. from English. St. Petersburg: Peter, 2003. - 464 p. ill. "Masters of Psychology".

"Masters of Psychology".

2. Danilina T.A., Zedgenidze V.Ya., Stepina N.M. In the world of children's emotions. - M.: Academy, 2001. -117 p.

3. Kryukova S.V., Slobodyanik N.P. I am surprised, angry, afraid, boasting and rejoicing. The program of emotional development of children of preschool and primary school age: A practical guide. M.: Genesis, 2001.- 98 p.

4. Kryazheva N.L. The world of children's emotions. Children 5-7 years old / Artists G. V. Sokolov, V. N. Kurov. Yaroslavl: Academy of Development, 2004. - 160 p. ill. "Your child: observe, study, develop."

5. Minaeva V.M. The development of emotions in preschoolers. Lessons. Games. Handbook for practitioners of preschool institutions. M.: ARKTI, 2001. - 48 p. (Development and education of a preschooler).

Published: 11/10/2020

5 Social Emotional Learning Skills Required for Lagging Students

The Highly Emotional Adolescent Brain

Teenagers are notorious for being emotional and impulsive. It turns out that the teenage brain is to blame.

It turns out that the teenage brain is to blame.

Thanks to neuro-technologies that allow us to literally look into the brain, we now have a neurological explanation for the disproportionate impulsivity of adolescents, their desire for risk and hypersensitivity to peer pressure.

Simply put, the development of the adolescent "rational brain" or prefrontal cortex lags behind the development of the "emotional brain" or limbic system of the brain. This means that executive function skills such as impulse control and emotion regulation often lose out to strong desires for instant gratification and peer approval. And emotions like stress, frustration, or embarrassment cause a short circuit in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, making learning difficult.

It is therefore no wonder that students who are lagging behind in reading and learning are in such dire need of support for social-emotional learning (SEA). For such students, a specific reading teaching methodology that includes SEA skills is likely to be more effective than a traditional reading development program. An example of such a technique is Fast ForWord with its latest programs Foundations and Elements (for high school students). This technique was developed by eminent US neuroscientists and is aimed at developing the areas of the brain responsible for speech, reading and cognitive functions - key elements for successful learning.

An example of such a technique is Fast ForWord with its latest programs Foundations and Elements (for high school students). This technique was developed by eminent US neuroscientists and is aimed at developing the areas of the brain responsible for speech, reading and cognitive functions - key elements for successful learning.

The social-emotional impact of reading lag

When students lag behind in reading, their self-confidence drops as they become aware that they are lagging behind their peers. By the time they become teenagers, they may feel socially and emotionally isolated. Thus, a domino effect begins due to a lack of motivation to try to catch up, frustration in learning and, ultimately, low expectations from one's own prospects. Often students' negative emotions lead to their destructive behavior, which affects their relationship with peers and teachers, leading, among other things, to lesson disruptions, neglect or lack of participation in class work.

The best approach to overcome these socio-emotional barriers to student achievement is to develop social-emotional skills. As best-selling author and education expert Eric Jensen states in his book Teaching with the Brain in Mind, “Emotions and the mind do not exist separately; emotions, thinking and learning are interconnected.”

But social-emotional learning is a big topic. What priorities should secondary school teachers set in teaching? Here are five social-emotional learning skills that are especially important for students in adolescence, and how the Foundations and Elements programs develop SEA skills and reading/learning skills at the same time.

Five social-emotional learning skills for high school students

1. Self-confidence

at school. A series of repeated failures often leads to self-doubt and even conviction of one's own stupidity.

The real problem is often not learning disabilities, but finding the right way to unlock the true, limitless potential of students. And when students begin to achieve academic success, their confidence skyrockets, which in turn helps them to study even better, and this cycle continues endlessly.

And when students begin to achieve academic success, their confidence skyrockets, which in turn helps them to study even better, and this cycle continues endlessly.

The secret to success lies in the 80:20 ratio between success and difficulty. This proportion is provided by classes that are not too difficult, so as not to suppress the motivation to study, and at the same time, classes are not too easy, forcing the student to work hard.

Students who regularly fall behind their peers in class are not used to a consistent 80% success rate. But if you arrange classes in such a way that these students are successful 80% of the time, they experience a surge of confidence that they can achieve their goals, instead of feeling overwhelmed by the fact that they are wrong all the time. The dopamine rush that accompanies this success also fires up students' intrinsic motivation to keep learning and succeeding.

Foundations and Elements are the latest Fast ForWord programs for slow learners. The exercises in these programs are constantly adapted to the student's abilities, the curriculum is designed to ensure that the student can consistently give at least 80% correct answers, with optimally timed rewards that keep students engaged and willing to learn. This system helps build self-confidence and ensures success in reading and learning.

The exercises in these programs are constantly adapted to the student's abilities, the curriculum is designed to ensure that the student can consistently give at least 80% correct answers, with optimally timed rewards that keep students engaged and willing to learn. This system helps build self-confidence and ensures success in reading and learning.

2. Healthy self-esteem

Students' increased confidence in their ability to learn and succeed creates a new sense of self - healthy self-esteem. Instead of thinking "I can't do this" or "I'm stupid", they set themselves up for success by believing in themselves: "I'm smart!".

One of the components of healthy self-esteem is flexible thinking, the belief that education makes a person successful, and not some intangible, innate ability to learn. The validity of this belief is rooted in the ability of the human brain to change, called neuroplasticity (brain plasticity). Neuroplasticity is the state of the brain as a flexible, experiential organ that can be constantly reprogrammed throughout life. Thanks to this, a person is never too late to learn new skills.

Thanks to this, a person is never too late to learn new skills.

After early childhood, adolescence is the time when the brain is at its most plastic, with incredible potential for continued learning. Thus, teenagers who need to strengthen their learning ability and confidence will greatly benefit from the development of flexible thinking.

Educators and parents can instill flexible thinking in middle school students by thinking through their speech. When a student says, "I can't do it," the teacher can gently correct him, "You can't do it yet. But you can! When a child says, "I'm giving up," the parent can support, "I'll help you find another way to deal with this." Teachers and parents should avoid making statements like "it's easy" and instead make sure their students know that "it's okay to have trouble."

One of the leading neuroscientists who elucidated the role of human brain plasticity in learning was Michael Merzenich, often referred to as the "father of neuroplasticity. " He is one of the founders of the Fast ForWord methodology, which uses neuroplasticity to effectively train the brain in speaking and writing, cognitive skills, and social-emotional skills at the same time. This is what flexible thinking means in action!

" He is one of the founders of the Fast ForWord methodology, which uses neuroplasticity to effectively train the brain in speaking and writing, cognitive skills, and social-emotional skills at the same time. This is what flexible thinking means in action!

3. Self-government

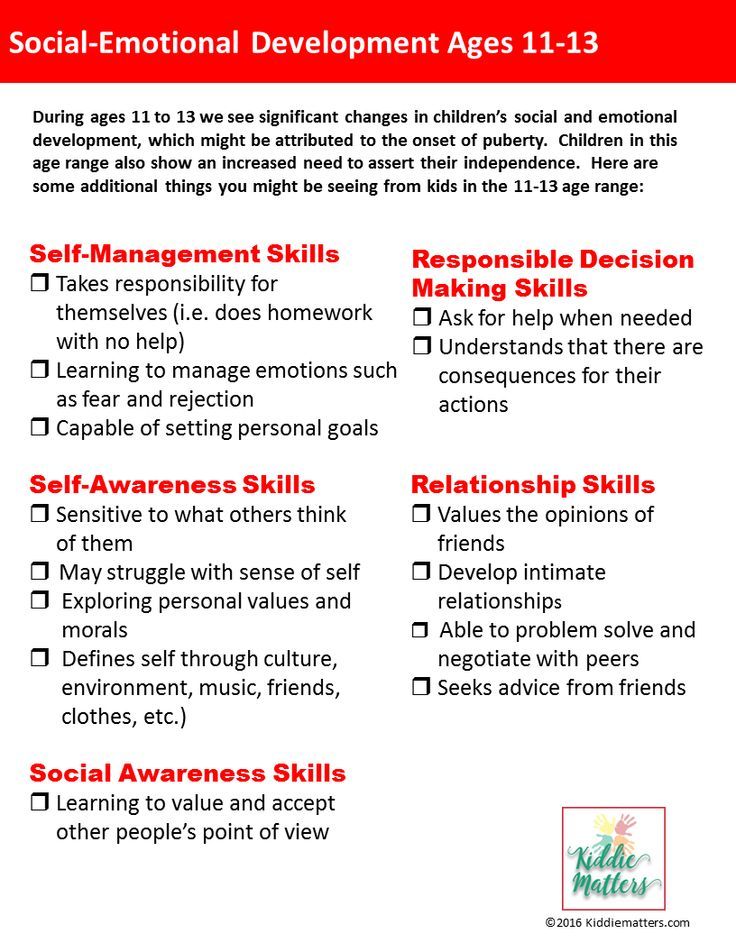

Self-management is the ability to regulate one's actions, thoughts, and emotions for goal-directed behavior that leads to the achievement of goals. As evidenced by a recent EdSurge article, high school students are successful when their self-management skills are developed.

Teenagers strive for independence and self-reliance, and educators can help them develop the self-management skills they need to succeed. Self-management skills include the ability to focus on the current task, goal setting, planning, and time management.

Some of the Foundations and Elements exercises are specifically designed to develop attention skills, developing the cognitive ability to stay focused on a task. For example, SonoLab is an exercise that requires students to listen carefully to a series of sounds and press a button as the sound changes. In essence, it trains the brain to concentrate and not act impulsively.

For example, SonoLab is an exercise that requires students to listen carefully to a series of sounds and press a button as the sound changes. In essence, it trains the brain to concentrate and not act impulsively.

Students also develop self-management by reviewing the "Today's Report" at the end of each session, tracking their own progress. As students evaluate how well they achieved their goals during each session, being single-minded becomes a habit and they improve their self-management skills.

4. Self-defence

Closely related to self-management is self-defence, that is, the ability to constructively support one's own interests and security both independently and when seeking help or support when needed.

Some students find self-defense easy. These are the students who raise their hands during the lesson, ask questions, and even ask for an extension of the deadline for assignments when extenuating circumstances arise.

Other students—usually those who are not confident in their academic or speaking skills, who are afraid of embarrassing themselves in front of their peers, or who fall behind so often in school that they lose interest in it—have not developed self-defence skills. Unfortunately, when these students encounter barriers to their academic progress, they don't seek the help they need. They don't ask for clarification when they don't understand the assignment. They miss deadlines.

Fortunately, today's technology offers a socially safe environment where students can access more information or practice more when difficult or confusing tasks come up, all without potentially embarrassing scenarios. And when students get used to seeking and receiving help on their own, with the help of a computer program, they can learn to seek help from a teacher or peers when they need it.

In Fast ForWord programs, such self-protection tools are implemented in the form of operational interventions. For example, if a student is having difficulty in any of the exercises, they can click on the question mark button in the top navigation bar to practice in "help" mode without affecting their progress or accumulated points. This socially safe self-help mechanism allows the student to learn at their own pace and seek the help they need without risking peer judgement.

For example, if a student is having difficulty in any of the exercises, they can click on the question mark button in the top navigation bar to practice in "help" mode without affecting their progress or accumulated points. This socially safe self-help mechanism allows the student to learn at their own pace and seek the help they need without risking peer judgement.

5. Self-control

Finally, self-management and self-protection combine to create self-control, to control the execution of all points to achieve the goal. Essentially, self-control is the student's ability to take responsibility for their own learning. As students develop the skills needed to become responsible adults, self-control becomes an important social-emotional learning ability.

From the very beginning of each lesson in Fast ForWord, students practice self-control. In the "Today's Assignment" menu, the student chooses which exercise to start with. Within each exercise, the student is responsible for the quality and completeness of their work; whether the lesson was completed; whether it is necessary to use the built-in help for additional practice, and for which exercise to move on to. At the end of each session, the student tracks their daily progress in the "Today's Report", enters the data into motivational tables and assesses whether the goals have been achieved.

At the end of each session, the student tracks their daily progress in the "Today's Report", enters the data into motivational tables and assesses whether the goals have been achieved.

What's more, because Fast ForWord Foundations and Elements are online programs, students can easily work with them at home, providing even more opportunities to practice self-organization and self-control.

Conclusions

Teenagers have special social-emotional learning needs due to their rapidly developing brains. Five social-emotional learning skills that can be especially useful for middle and high school students are self-confidence, healthy self-esteem, self-management, self-protection, and self-control.

Along with developing the language, writing, and cognitive skills needed for academic success, Fast ForWord Foundations and Elements classes develop the skills needed for self-management and self-protection. The combination of these two factors gives the student a sense of confidence in their ability to learn and exercise free will, providing a sense of control over tasks and their successful completion.

Petersburg, Florida. Register Today!

Petersburg, Florida. Register Today!