Early writing activities

Early Writing Skills (10 Activities!) • JournalBuddies.com

Journal Buddies Jill | | Early Writing Skills

Activities to Develop Early Writing Skills in Young Children— Many parents and caretakers mistakenly assume that children don’t need to begin developing their writing skills until they go to school and start learning to read and write in earnest.

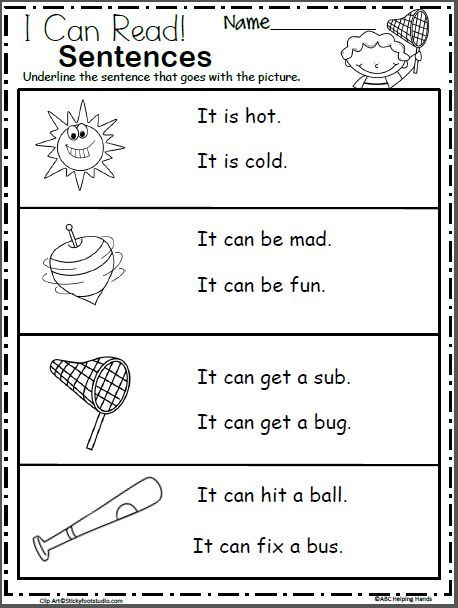

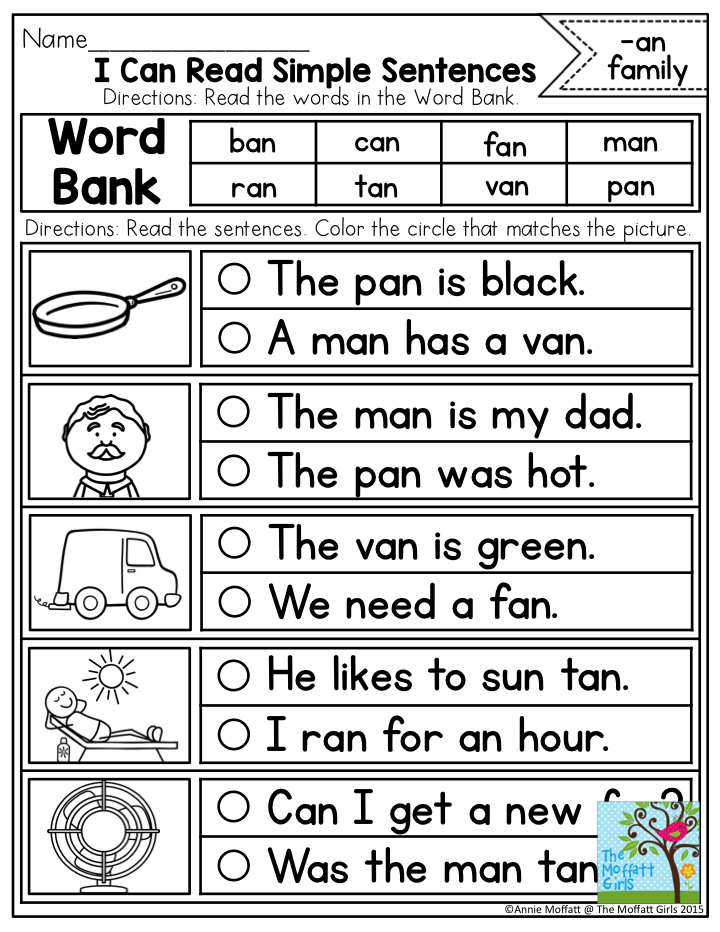

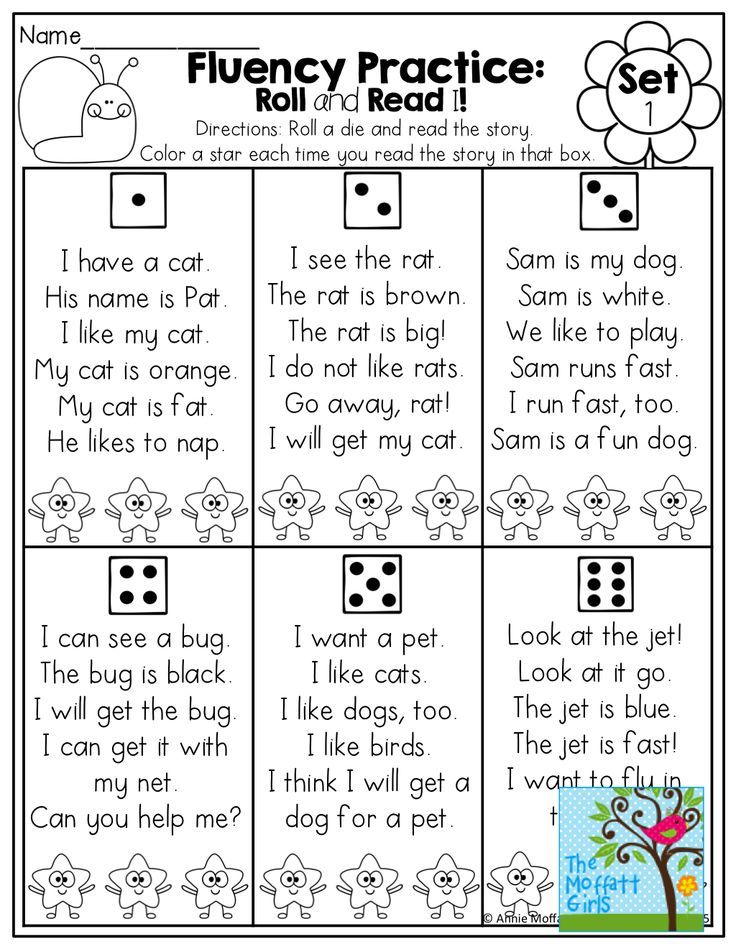

While it’s true that most young children won’t begin fully reading and writing until they are in kindergarten or first grade, it’s still important to begin practicing early writing skills long before they head off to school.

Children can begin developing their early writing skills as early as 2 or 3 years old. These activities can help parents, educators, and caretakers get started.

Most likely, your child won’t even realize that you are working on their pre-writing skills with these innovative activities. They will simply be having fun while their mind and body work together to form the solid foundation that will be necessary to write clearly and effectively once they begin school.

- Make an alphabet book together. Write a big bubble letter on each page of the book and let your child color the letter in. After you have colored all of the letters, work together to find pictures that begin with each letter in a magazine or newspaper. The pictures can be glued onto the pages and then your child will have a complete alphabet book that they can flip through at any time.

- Use toy cars to make marks in shaving cream. Making marks such as lines, circles, and zig-zags is the first step in learning how to write letters. Your child will have fun making a mess, but you will know they are developing pivotal muscle memory that will be needed for writing in the future.

- Paint the house with water. This is a great summer activity that will keep your toddler or preschooler busy, while also helping them improve their grip and dexterity.

Grab an old paintbrush and a big bucket of water and let your child paint letters, lines, or other shapes on the outside of your home.

Grab an old paintbrush and a big bucket of water and let your child paint letters, lines, or other shapes on the outside of your home. - Play a version of the game “Red Light, Green Light” with punctuation marks. Get three sheets of construction paper — one red piece, one yellow piece, and one green piece. On the red piece, use a period for “Stop.” On the yellow piece, use a comma for “Slow down.” On the green piece of paper, use an exclamation point for “Go!”

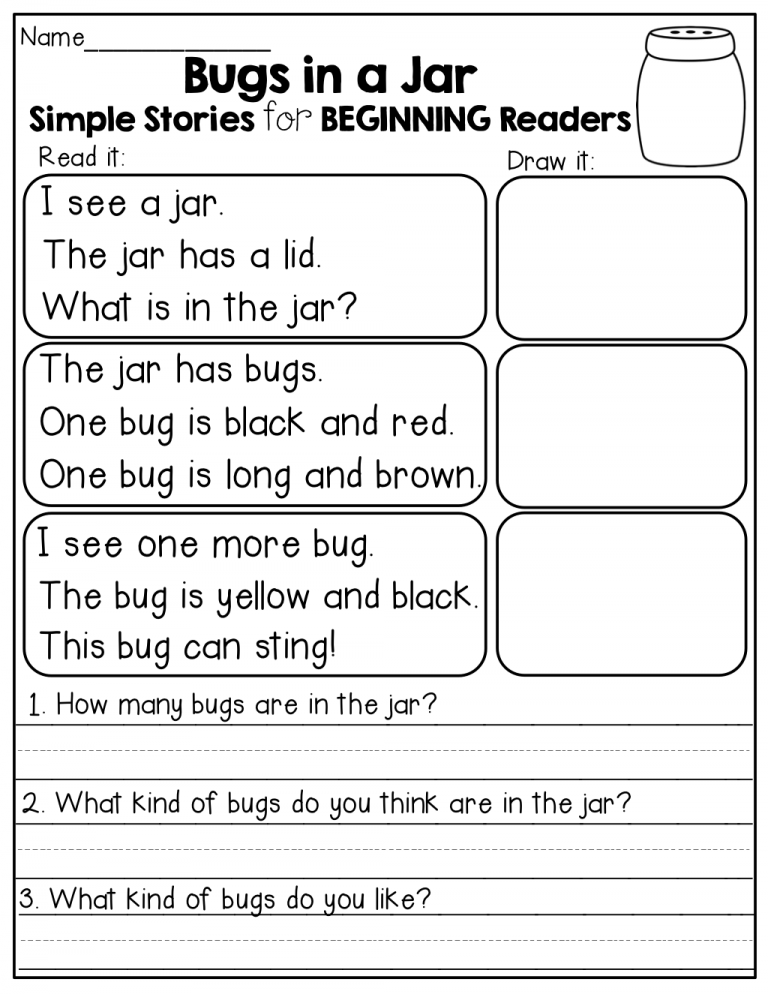

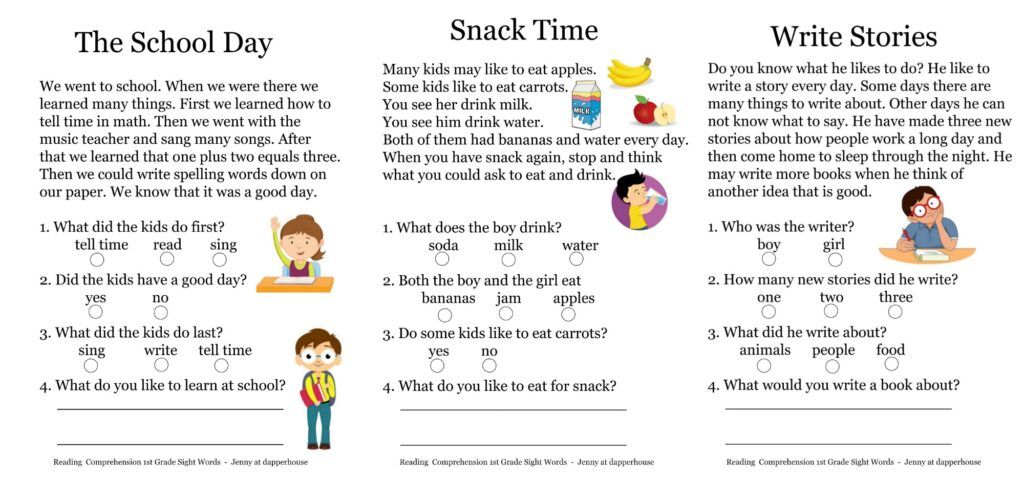

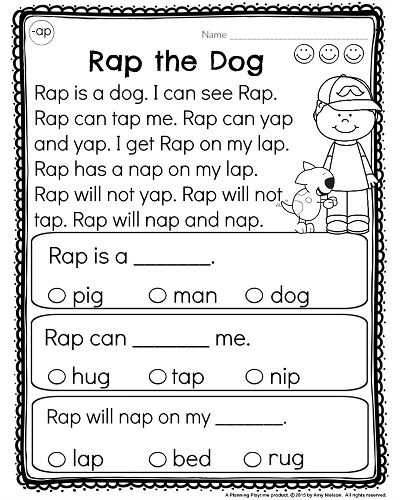

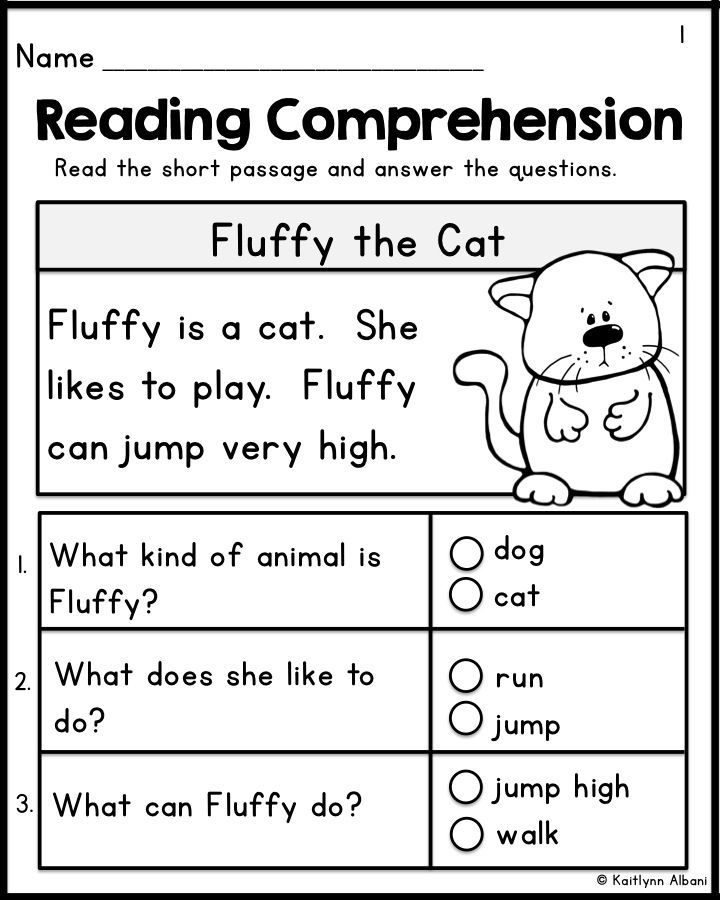

- Read a story out loud to your child and ask them to draw a picture based on the story. This activity helps them start to identify the elements of a story and encourages them to make a connection between reading and writing.

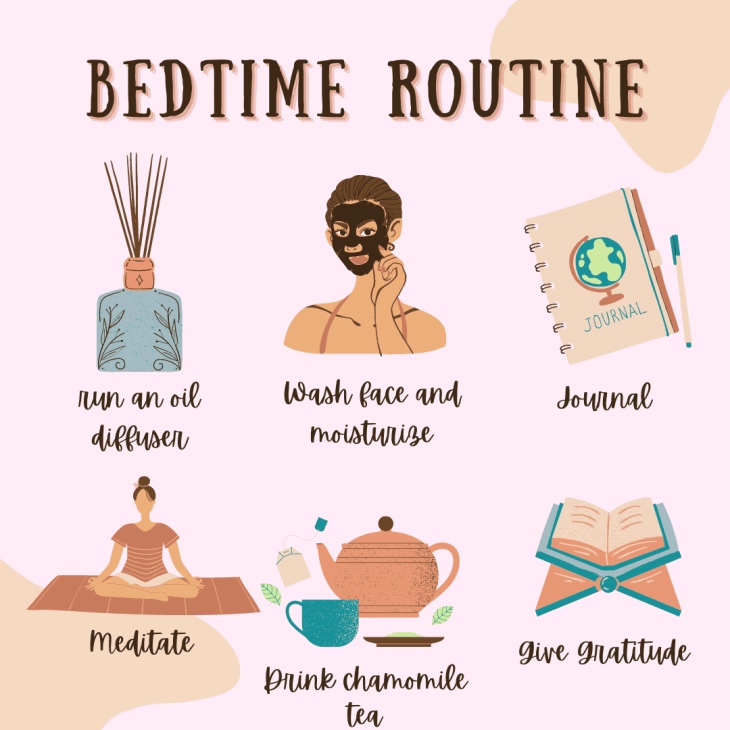

- Create a daily menu at home. Write out what is for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Ask your child to draw pictures to match the menu. Then read them the menu at every meal as a reminder.

- Encourage your child to draw a self-portrait using markers, crayons, or colored pencils. Simply using these tools will help them develop the fine motor skills necessary to write in the future.

Keep an eye on how your child is holding their marker or crayon and help them adjust if necessary so that they can practice using a proper grip.

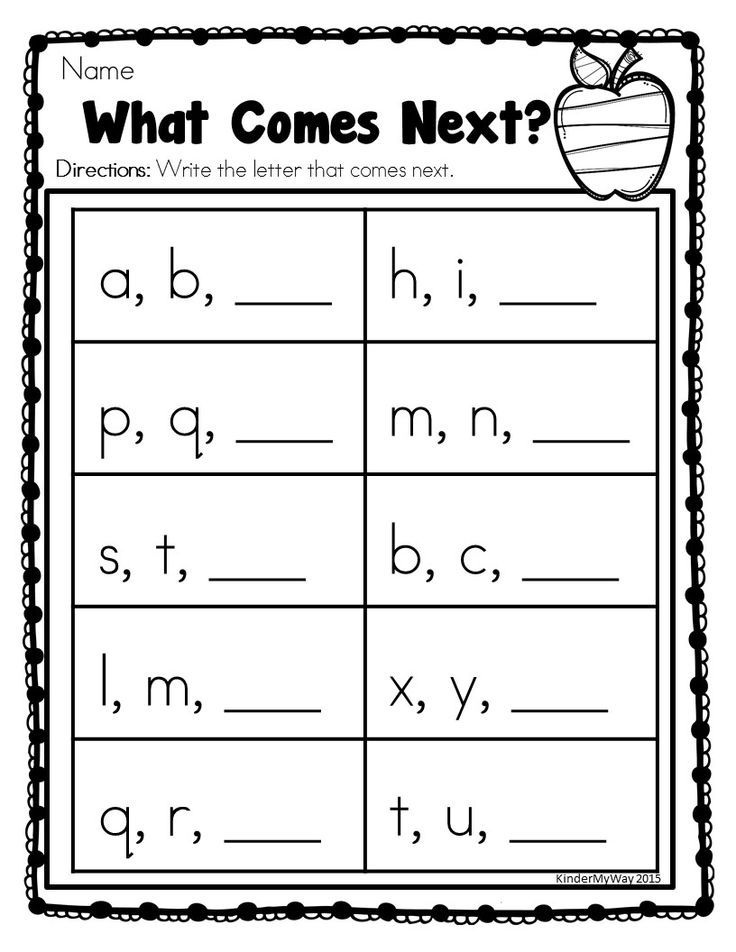

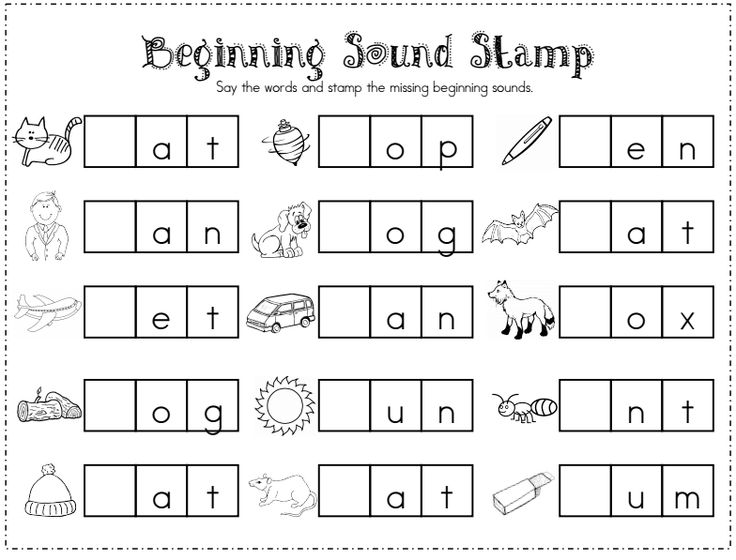

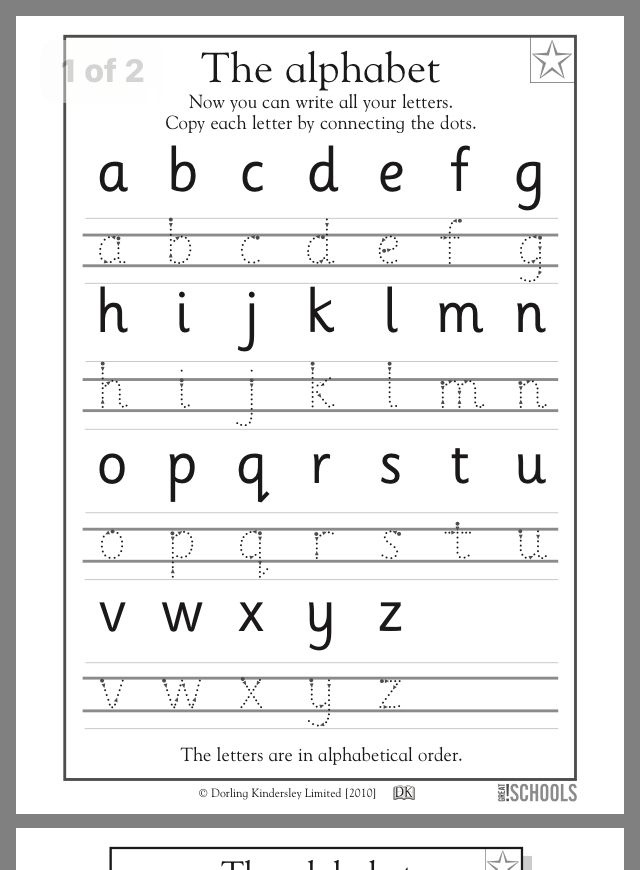

Keep an eye on how your child is holding their marker or crayon and help them adjust if necessary so that they can practice using a proper grip. - Have your child trace the letters of the alphabet. Write each letter out using dotted lines and show your child how to trace them. By helping them complete this activity, you will be teaching letter recognition as well as formation.

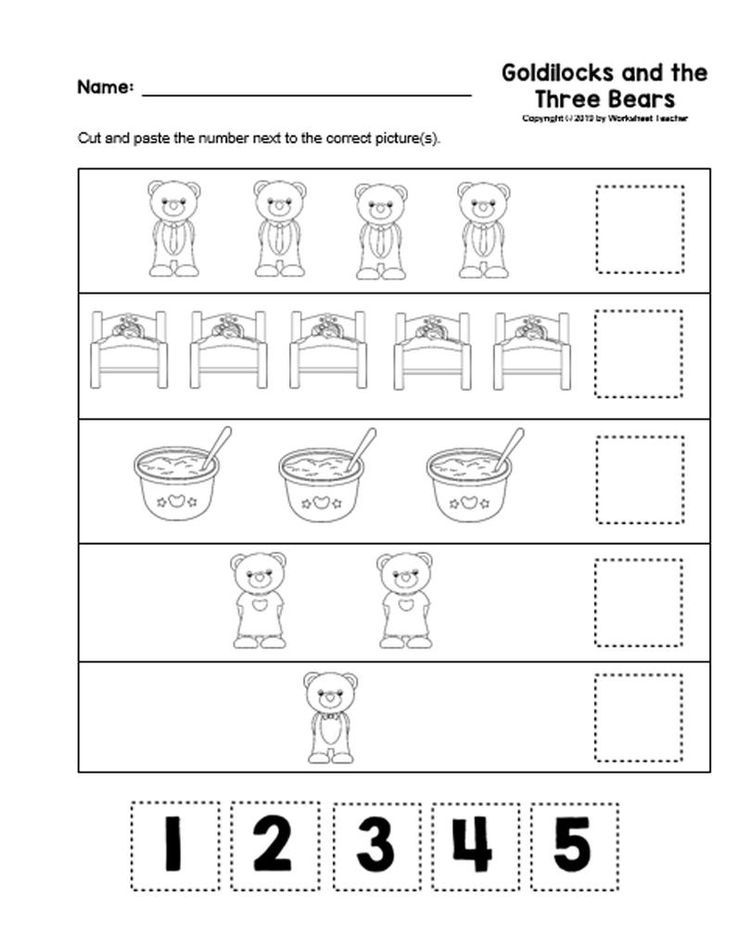

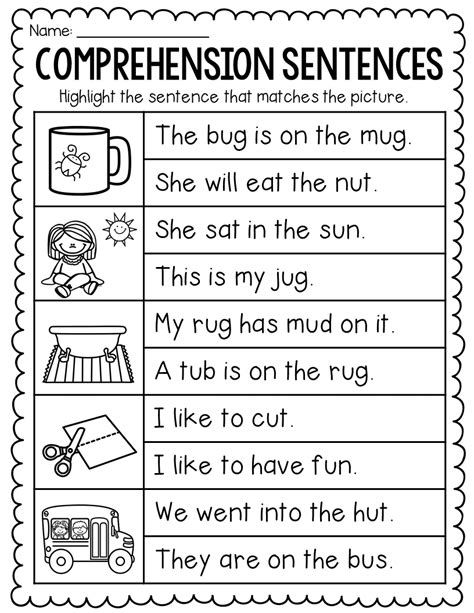

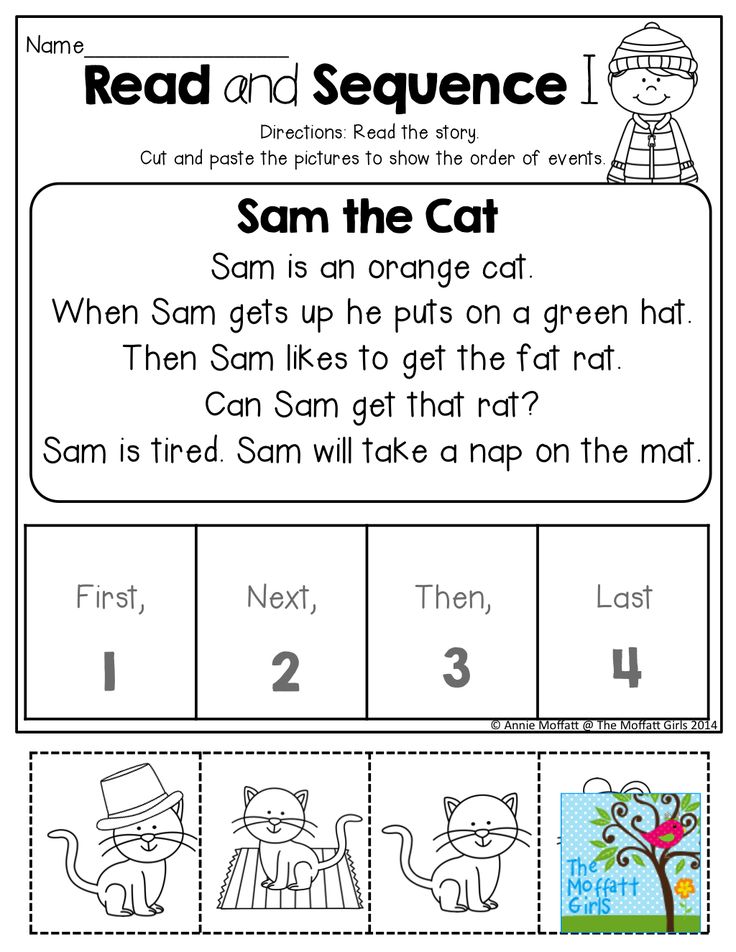

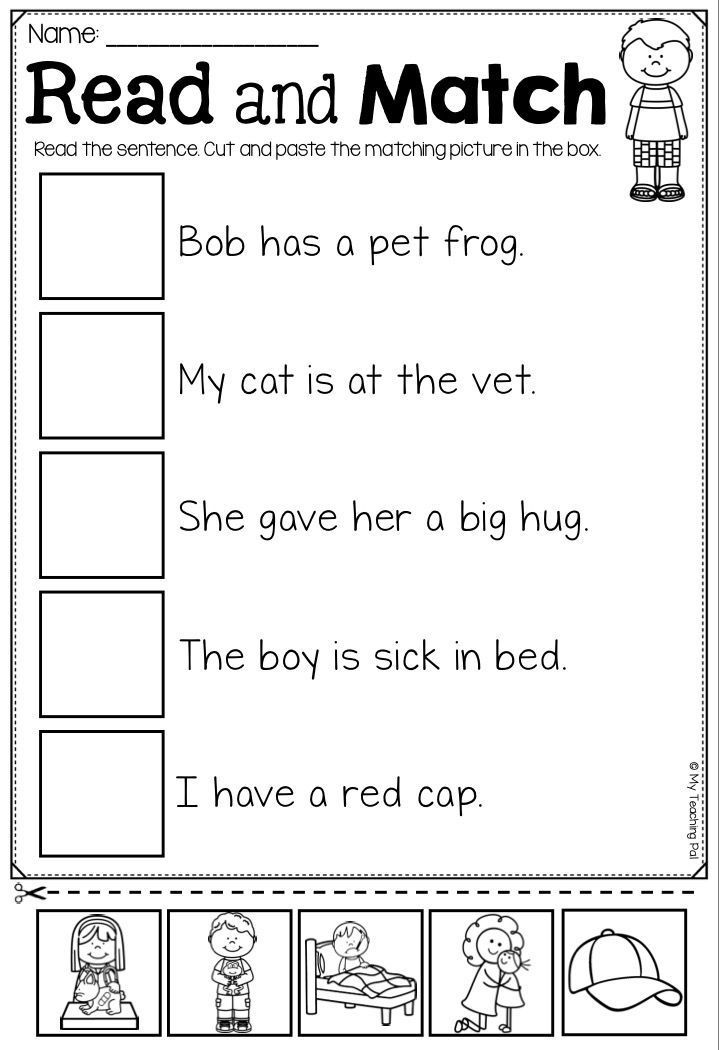

- Work with your child to tell a story using sentence flash cards. Write out different sentences on 10-15 flashcards. Read the sentences to your child and have them sequence the flashcards into a story. Once they are done, read their silly story back to them.

- Draw shapes on a piece of paper and ask your child to draw the same shape next to it. This improves hand-eye coordination and allows children to develop their fine motor skills.

These pre-writing activities help preschool children develop the foundational skills needed in the preschool classroom – all while having fun! Other fine motor activities like threading beads with their dominant hand, working on puzzles, or tracing letters in a tray full of salt will help young children develop literacy skills. Children’s writing is an important piece of early childhood education.

Children’s writing is an important piece of early childhood education.

- Early Writing and Reading Activities

- How to Teach Preschoolers to Write

- Writing Skills at Different Ages

Early writing skills are pivotal, so it’s important to start focusing on muscle development and writing concepts as soon as possible. When you start writing early, your child will be much more likely to keep on writing!

If you enjoyed these Early Writing Skills Activities,

please share them on Facebook, Twitter, and/or Pinterest.

I appreciate it!

Sincerely,

Jill

journalbuddies.com

creator and curator

262 shares

------------Start of Om Added ---------

Featured Posts

SearchNewly Published Posts

Now Offering You 15,000+ Prompts!

Hello! I’m Journal Buddies Jill. I am so happy you found my blog.

I am so happy you found my blog.

------------End of Om Added ---------

Tags Activities to Develop Early Writing Skills, children, developing writing skills school, Early Writing, Early Writing Skills, Early Writing Skills Activities, Early Writing Skills Young Children, innovative brew-writing activities, learning, Pre-Writing Skills, writing, writing kills, young childrenPre-Writing Activities for Preschoolers - WeAreTeachers

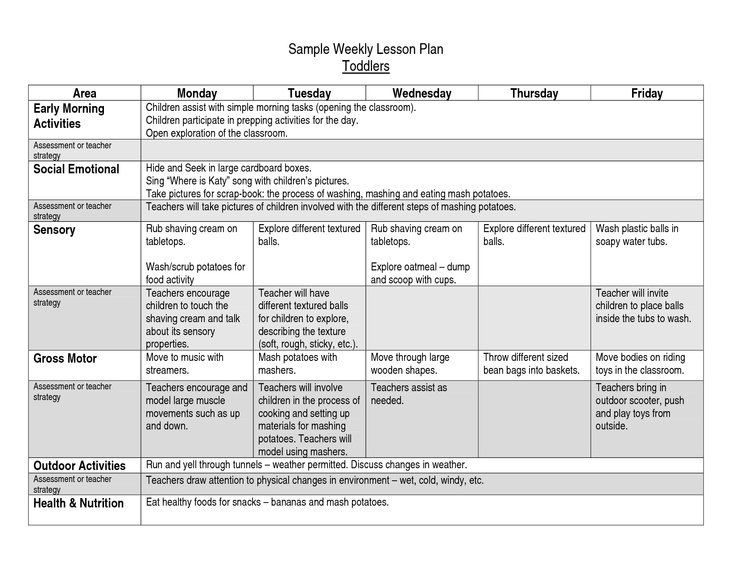

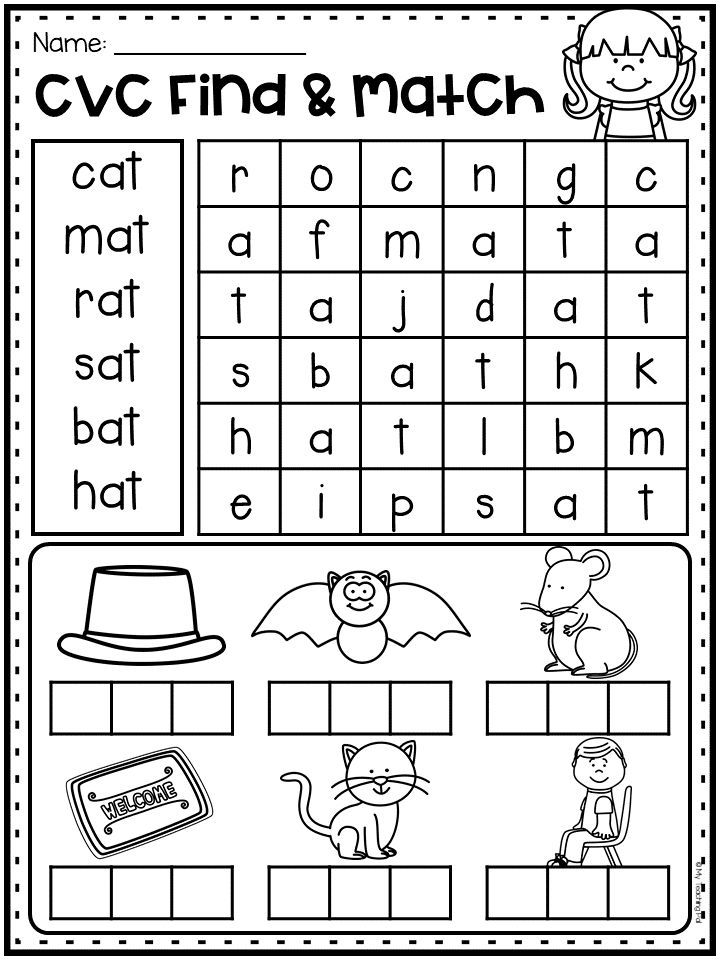

Pre-writing activities for preschoolers not only help our youngest learners learn the shape and structure of the letters in the alphabet, but they also serve a number of other functions as well. According to education blogger Lisette, from Where Imagination Grows, pre-writing practice teaches directionality in writing, encourages fine muscle development and coordination, and also helps students process sensory information critical to the writing process.

Here are 22 super fun, easy-to-make activities that your preschoolers will love!

1. Squishy Bags

Source: Learning4kids

All you need to make these awesome sensory bags is resealable zipper storage bags, flour, water, and food coloring. Kids can use cotton swabs or their fingers to draw shapes, lines, and letters on the bag.

2. Bubble Wrap

Source: Coffee Cups and Crayons

What a great way to recycle all that leftover bubble wrap! Simply write letters on sheets of bubble wrap with a Sharpie and let kids pop their way to letter recognition.

ADVERTISEMENT

3. Play-Doh Snakes

Source: In My World

Kids can’t resist the sensory lure of Play-Doh! For this activity, kids can roll small balls of dough into long snakes and form letters by bending and joining the snakes together.

4. Play-Doh and Drinking Straws

Source: KidActivitiesBlog

Flatten out a medium-size piece of Play-Doh on a flat surface. Then use a sharp object to draw a letter on the flattened area. (Make sure that the letter is large enough to be easily recognizable when filled with straws.) Cut plastic straws into one-inch segments. Let kids “trace” the letters with the colorful straw segments.

Then use a sharp object to draw a letter on the flattened area. (Make sure that the letter is large enough to be easily recognizable when filled with straws.) Cut plastic straws into one-inch segments. Let kids “trace” the letters with the colorful straw segments.

5. Dot Markers

Source: 3 Dinosaurs

Students use dot markers to practice the mechanics of writing and get used to the angles and curves of letters. Click on the link above to download 12 free pages of pre-writing dot marker worksheets.

6. Cotton Swabs and Paint

Source: Lessons Learnt Journal

This is a fun activity to help kids work on their fine motor skills and get the hang of the all-important pencil grip.

7. LEGO Blocks

Source: Wildflower Ramblings

Blocks! Young kids can’t get enough of building and creating with them. Put their creative energy to good work with these free printable letter cards.

8. Shaving Cream

Source: Mess for Less

This classic activity is a great starting place for pre-writers. All you need is a tray and a can of shaving cream.

All you need is a tray and a can of shaving cream.

9. Glitter Glue

Source: Growing Hands-On Kids

Pre-writing lines are important building blocks for any preschooler to master before learning letter formations. Download this glitter glue pre-writing line practice for preschoolers activity.

10. Beads

Source: Artsy Momma

Just like the one above, this activity builds fine motor skills that your young students need to begin writing. Instead of using glitter glue, though, students use inexpensive pony beads (found at any craft store) to follow the lines.

11. Sand Tray

Source: Our Little House in the Country

One of the simplest activities to put together for your students to practice pre-writing is a sand tray. Kids can use their fingers or an unsharpened pencil to practice writing. As an alternative to sand, you can fill your tray with salt, flour, cornmeal, or rice.

12. Squeeze Bottle

Source:: Playdough to Plato

Fill a plastic squeeze bottle with salt or sugar and let students trace letters on cards.

13. Rainbow Tray

Source: Where Imagination Grows

This resource is so simple to make, and kids love it! Simply tape colored tissue paper in a rainbow pattern to the bottom of a clear plastic tray. Fill it with sand, and as the kids trace lines and letters, the colors below are revealed. The image above shows the tray on top of a light table, which adds another dimension of fun to the activity!

14. Masking Tape

Source: And Next Comes L

A roll of colored masking tape and a clear surface make this a fun center activity at writing time.

15. Magnet Board

Source: Days with Gray

Tape letters onto a magnet board and let your little ones trace them with magnets. In the example above, the teacher made the letters into roads, and the students drove their car magnets along them.

16. Lacing Cards

Source: Teaching Mama

Grasping a string between tiny fingers and threading the end through the holes in a lacing card is great fine motor practice for preschoolers. It also begins to build muscle memory for holding a pencil properly.

It also begins to build muscle memory for holding a pencil properly.

17. Buttons

Source: Learning4Kids

Preschoolers will have so much fun creating patterns, swirls, squiggles, and zig-zags with colorful buttons. And they’ll be building skills while they’re at it!

18. Sticker Line Up

Source: Busy Toddler

Preschoolers need to use a pinching motion, which builds fine motor skills, to peel sticker dots off the page. Then, they use hand-eye coordination to place each sticker on the drawn line. This activity would be perfect for a writing or free time station.

19. Fingerprint Writing

Source: Happy Toddler Playtime

Some kids may not like to get their fingers this messy, but others will adore it! For this activity, you will need poster paper and a palette of washable ink. Draw letters, shapes, and lines on a clean piece of paper. Then, show kids how to dip their pointer finger onto the ink pad, then follow the lines dot by dot.

20. Clothespin Clipping

Source: Teaching Mama

Using a clothespin takes a lot of grip strength. This image shows a student using a clothespin to choose the correct answer to a number problem, but any activity that involves clipping will help them build the fine motor skills required for writing.

21. Cutting

Source: Play of the Wild

Cutting and snipping activities with scissors are excellent ways for children to practice fine motor skills and control. Give your students lots of opportunities to practice their cutting skills with paper, string, card stock, even Play-Doh!

22. Scrunching Paper

Source: Gympanzees

Scrunching paper into a ball is great for building hand strength. Let your students use computer paper, newspaper, tissue paper, or wrapping paper. Then play a game of paper ball tag!

What are your favorite pre-writing activities for preschoolers? Share in the comments below.

Plus, check out these amazing Sensory Table Activities.

Early literary activity - Studiopedia

Share with friends:

In 1730, immediately upon his return from abroad, Trediakovsky published a translation of the gallant-allegorical novel by the French writer Paul Talman entitled "Ride to the Island of Love." It was one of the examples of a love story. The text of the work is prosaic, with numerous poetic inserts of a love and even erotic nature. The experiences of the characters - Tirsis and Amyntas - are clothed in allegorical form. Each of their feelings corresponds to the conditional toponymy of the "Island of Love": "cave of cruelty", "castle of Direct Luxury", etc. Along with the real ones, conditional characters such as "Pity", "Sincerity", "Eye-loving", i.e. coquetry . In European literature of the 30s of the XVIII century. P. Talman's novel was an anachronism, but in Russia it was a great success. The secret of its popularity was that it turned out to be consonant with the handwritten stories of the time of Peter the Great, such as "History of the nobleman Alexander", in which there were also poetic inserts - "arias" of love content. The novel aroused sharp dissatisfaction with the clergy, who were disgusted by its secular, erotic character. The preface to the book was also disturbing. The translator refused to use Church Slavonicisms, which he declared to belong to church, and not to secular literature. The "Slavonic" language seems to him "hard", i.e. dissonant and incomprehensible to the reader.

The novel aroused sharp dissatisfaction with the clergy, who were disgusted by its secular, erotic character. The preface to the book was also disturbing. The translator refused to use Church Slavonicisms, which he declared to belong to church, and not to secular literature. The "Slavonic" language seems to him "hard", i.e. dissonant and incomprehensible to the reader.

Trediakovsky's book is also interesting because on its last pages he placed his own poems, written by him both before his departure and during his stay abroad, under the title "Poems for Various Occasions". This is Trediakovsky's pre-classical lyrics. It presents not a state, but a purely personal, autobiographical theme, which is reflected even in the titles of some works. So, one of the poems is called "A song that I composed, while still in Moscow schools, on my departure to a foreign land." For all the helplessness of this early poem, it contains successful lines in which one can feel both the splashing of the waves, and the rocking of the ship, and the joyful and anxious mood of the traveler ready to sail:

The rope is breaking,

The anchor is beating,

To know, the boat will rush. [27]

[27]

Another poem is connected with the poet's stay in Holland. It is called "Description of a thunderstorm that was in The Hague." "Poems in praise of Paris" convey the poet's admiration for the French capital. He likes its mild climate, its picturesque nature. Various arts, including poetry, found shelter here. But, admiring Paris, Trediakovsky yearns for his homeland, which he has not seen for several years. This is how "Poems of Praise for Russia" are born:

I'll start on the flute sad verses,

In vain to Russia through distant countries...

All your people are Orthodox

And glorious everywhere with courage;

Children are worthy of such a mother,

Everywhere they are ready for you (p. 60).

Many poems are dedicated to the theme of love: "A petition for love", "A song of love", "Poems about the power of love". Next to the Russians, poems written in French are published. The rawness of the Russian poetic language makes itself felt: the poet succeeds in French verses better than Russian ones.

All the lyrics presented in the book are written in syllabic verse, but in four years Trediakovsky will resolutely reject syllabics and propose a new system of versification instead.

Like this article? Bookmark it (CTRL+D) and don't forget to share it with your friends:

A. Platonov - writer and publicist: early years

The author traces the evolution of the views of the young A. Platonov. The natural-scientific and philosophical context of the writer's work at the turn of the 19th century is considered.10-1920s. The fundamental features of the Platonic worldview are revealed.

Keywords: Platonov-publicist, evolution of views, context

The youth of Andrei Platonov coincided with the revolution of 1917 and the Civil War. It was at this time that the writer's convictions were formed, many of which he retained for the rest of his life. The first decade after the communist takeover in Russia was marked by the construction of a new type of state. It seemed that very soon inequality and exploitation would be eliminated, the poor would gain freedom and all human benefits. “The socialist Western ideals in the Russian radical-revolutionary milieu, which retained in itself, albeit with the opposite sign, the religious energy of the people, who always looked forward to the Kingdom, the City of Kitezh, received a special transformed chiliastic inclination: their implementation - moreover, by means of exclusively external social reorganization - must it was, according to the new, ardent faith of numerous adherents, to lead to the final harmonization of human nature, to the reign of a heavenly earthly order ”(Philosophical Context of Russian Literature 1920-1930s, 2003: 15). Among these adherents was Platonov, who in the early 1920s worked as a land reclamation engineer and a specialist in the electrification of agriculture. He associated the effectiveness of social transformations primarily with the accumulation of scientific potential and the development of technology.

The first decade after the communist takeover in Russia was marked by the construction of a new type of state. It seemed that very soon inequality and exploitation would be eliminated, the poor would gain freedom and all human benefits. “The socialist Western ideals in the Russian radical-revolutionary milieu, which retained in itself, albeit with the opposite sign, the religious energy of the people, who always looked forward to the Kingdom, the City of Kitezh, received a special transformed chiliastic inclination: their implementation - moreover, by means of exclusively external social reorganization - must it was, according to the new, ardent faith of numerous adherents, to lead to the final harmonization of human nature, to the reign of a heavenly earthly order ”(Philosophical Context of Russian Literature 1920-1930s, 2003: 15). Among these adherents was Platonov, who in the early 1920s worked as a land reclamation engineer and a specialist in the electrification of agriculture. He associated the effectiveness of social transformations primarily with the accumulation of scientific potential and the development of technology.

The novice writer studied the works of philosophers and scientists - his contemporaries. According to N. Kornienko, his library contained brochures by K. Tsiolkovsky, fiction by J. Verne and G. Wells, part of N. Fedorov's book "Philosophy of the Common Cause", A. Rifling's book "The New World War", a study by S. Nordman " Einstein and the Universe”, as well as V. Bogoraz-Tan’s essay “Einstein and Religion” (Kornienko, 1993:20-21). Undoubtedly, these and other works played an important role in the formation of a unique Platonic worldview. However, E. Balburov rightly noted that it is impossible both to belittle and exaggerate the importance of historical and biographical facts. The work of any artist should be considered in the context of his era, not limited to the discovery of direct influences. E. Balburov states: “Whether V. Solovyov has read Platonov or not, the idea that the real whole is a living organism and that “everyone is a necessary organ of everything” occupies Platonov no less than the author of Readings on God-Mankind. Whether S. Frank's Plato's books were on the bookshelf or not, it is already clear that the idea of a reality that "does not come to us from the outside, but is given to us from the inside, like the soil in which we are rooted and from which we grow," artistic discourse Platonov embodies with no less energy than the philosophical discourse of S. Frank” (Balburov, 1999:35). In order to reveal the peculiarities of the writer's perception of reality, it is necessary, without a doubt, to turn - among other things - to the works of art created by him.

Whether S. Frank's Plato's books were on the bookshelf or not, it is already clear that the idea of a reality that "does not come to us from the outside, but is given to us from the inside, like the soil in which we are rooted and from which we grow," artistic discourse Platonov embodies with no less energy than the philosophical discourse of S. Frank” (Balburov, 1999:35). In order to reveal the peculiarities of the writer's perception of reality, it is necessary, without a doubt, to turn - among other things - to the works of art created by him.

At the very beginning of the 1930s, Platonov made the following entry in his working notebook: “My young, serious (funny in form) will remain the main content forever, for a long time” 1 . So, in essence, it happened. However, this does not prevent us from talking about the transformation of writers' views. Still, the twenty-two-year-old land reclamator and the author of The Foundation Pit and Happy Moscow, who went through the war, are different people. Life inevitably made adjustments to Platonov's unchanging ideals. Quite often, he had to “argue with himself, overcome his own views at the cost of severe crisis spiritual states, abandon previously worked out decisions and conclusions in the name of new, more accurate and profound” (Vasiliev, 1982:46). It is important to identify the main milestones of this ideological evolution and determine the place of the writer in the history of philosophical and religious thought. The researcher of his work A. Varlamov says: “Platonov is a figure of the boundary, he is on the very line of the gap between life and death, between God and man, man and machine, man and nature. He passed this gap through his heart, trying to connect the incompatible, and, perhaps, in this borderland lies the key to his work and destiny” (Varlamov, 2011: 6). Today, many more "doors" in the art world and the writer's biographies remain closed. In this article, we will focus on the early period of Andrey Platonov's work.

Life inevitably made adjustments to Platonov's unchanging ideals. Quite often, he had to “argue with himself, overcome his own views at the cost of severe crisis spiritual states, abandon previously worked out decisions and conclusions in the name of new, more accurate and profound” (Vasiliev, 1982:46). It is important to identify the main milestones of this ideological evolution and determine the place of the writer in the history of philosophical and religious thought. The researcher of his work A. Varlamov says: “Platonov is a figure of the boundary, he is on the very line of the gap between life and death, between God and man, man and machine, man and nature. He passed this gap through his heart, trying to connect the incompatible, and, perhaps, in this borderland lies the key to his work and destiny” (Varlamov, 2011: 6). Today, many more "doors" in the art world and the writer's biographies remain closed. In this article, we will focus on the early period of Andrey Platonov's work.

In his small homeland, Platonov was known primarily as a poet, journalist, and engineer. He published his numerous poems and articles on the pages of local newspapers (Red Village, Voronezh Commune). The main features of his work of this period are inconsistency, inconsistency, and also a utopian character.

Platonov pays much attention to the issues of scientific knowledge. Calling science the "head" of the revolution, he perceives it as a means of combating nature. This position becomes clear if we remember that the young meliorator participated in the fight against the drought that caused the famine 1921 years old. In one of his articles, Platonov writes: "Man takes up arms against nature through nature itself, he beats her with the instruments of her laws" 2 . Obviously, Plato's newspaper materials were supposed to fulfill an educational function. The writer explains many processes and phenomena using simple examples that are understandable even to semi-educated people. At the same time, one gets the impression that he is thinking together with the reader in order to understand this or that topic himself.

At the same time, one gets the impression that he is thinking together with the reader in order to understand this or that topic himself.

Platonov adheres to the class approach: he divides science into proletarian and bourgeois, accusing the latter of idealism. In his opinion, the bourgeoisie “always saw a whole global idea in a separate fact, phenomenon, unconsciously threw this idea onto human society, and, with an amazing result, this insignificant idea, thrown here from the field of exact science by an original method of class thinking, always this idea justified the status quo.” 3 . The writer contrasts bourgeois idealism with materialistic science, which "studies the smallest facts separately, then notices their dependence, connects and obtains an accurate picture of reality" 4 .

In 1921, Platonov's article entitled "Audible Steps" was published, which, in fact, was a kind of review of the book "Space and Time" by the mathematician Minkowski, a follower of Einstein. It is precisely in the first post-revolutionary decade that the fascination with the theory of relativity in Russian art falls. According to N. Kornienko, Platonov’s perception of it was of a religious and philosophical nature: “He went through the trials of this theory and stopped before that picture of the world, the cosmos, which was widely introduced by the Einsteinians in various areas of public consciousness” (Kornienko, 1993:21). At this time, the writer reads the work of S. Nordman "Einstein and the Universe." Here are his main provisions: “First: the hypothesis of absolute time and absolute space, coming in science from Aristotle and Newton, is false from a scientific point of view. The only time is psychological. Second, there are no absolute points of support in the world, in space. <...> Third: the theory of relativity overturns ideas about matter... <...> Fourth: the theory of general relativity destroys the principle of inertia of Newtonian mechanics, that law of universal gravitation to which the cosmos is subject, where everything is interconnected” (ibid.

It is precisely in the first post-revolutionary decade that the fascination with the theory of relativity in Russian art falls. According to N. Kornienko, Platonov’s perception of it was of a religious and philosophical nature: “He went through the trials of this theory and stopped before that picture of the world, the cosmos, which was widely introduced by the Einsteinians in various areas of public consciousness” (Kornienko, 1993:21). At this time, the writer reads the work of S. Nordman "Einstein and the Universe." Here are his main provisions: “First: the hypothesis of absolute time and absolute space, coming in science from Aristotle and Newton, is false from a scientific point of view. The only time is psychological. Second, there are no absolute points of support in the world, in space. <...> Third: the theory of relativity overturns ideas about matter... <...> Fourth: the theory of general relativity destroys the principle of inertia of Newtonian mechanics, that law of universal gravitation to which the cosmos is subject, where everything is interconnected” (ibid. ). A similar view of the world was reflected in the fantastic stories and stories of Platonov in the middle of the 19th century.20s.

). A similar view of the world was reflected in the fantastic stories and stories of Platonov in the middle of the 19th century.20s.

N. Malygina believes that the connection between Plato's understanding of reality and the categories of the scientific consciousness of the era can be found already in the writer's poetic works. Her interpretation of the lines from Platonov's poem "To Star Comrades" is curious:

On the ground, on an electric bird

We planned to catch up with the sun and extinguish it.

The unknown cosmic ocean beckons us,

We will pour thoughts from the mysterious stars0053 5 .

Based on this quatrain, the researcher makes a bold assumption that its author was aware of the ideas of the Russian scientist of the early 19th century N.V. Karazin about the transformation of the earth into an electromagnet, the movement of which in outer space is subject to the will of man. This hypothesis of N. Malygina may seem controversial, but her interpretation of Plato's call to extinguish the sun is beyond doubt. Obviously, it is connected with the ideas of Carnot-Clausius-Thomson about the thermal death of the world. According to N. Malygina, the writer “emphasized the fact that both humanity and the sun can act both as destroyers and as creators. Therefore, the task of the human mind is to resist the destructive action of solar energy and direct it for the "creativity of life", i.e. affirmation of life" (Malygina, 1981:52).

Obviously, it is connected with the ideas of Carnot-Clausius-Thomson about the thermal death of the world. According to N. Malygina, the writer “emphasized the fact that both humanity and the sun can act both as destroyers and as creators. Therefore, the task of the human mind is to resist the destructive action of solar energy and direct it for the "creativity of life", i.e. affirmation of life" (Malygina, 1981:52).

Plato attaches great importance to the philosophical categories of "truth" and "good". Here he again draws the line between the past and the present: “The bourgeoisie in science also sought not so much the truth as the good. We will seek the truth, and in truth there is good” 6 . The writer illustrates his idea with the words of V. Rozanov: "I do not want the truth, I want peace." It must be said that Platonov repeatedly went over to the individual. So, in the article “The Soul of the World,” he openly condemned the Austrian philosopher O. Weininger, who emerged “from the depths of the bourgeoisie,” for “cursing a woman. ” At the same time, the writer emphasized that the revolution “has given into the hands of a woman all the forces of life, supremacy over her growth and flourishing. There is nothing in the world higher than a woman, except for her child.0053 7 .

” At the same time, the writer emphasized that the revolution “has given into the hands of a woman all the forces of life, supremacy over her growth and flourishing. There is nothing in the world higher than a woman, except for her child.0053 7 .

The influence of Eurasian ideas on Russian literature at the beginning of the 20th century has been repeatedly noted by scientists. O. Kaznina writes that literary “Eurasianism” as a worldview was characterized by “an apocalyptic vision of history, the idea of a special mission for Russia, a focus on the problem of Russia’s choice of a historical path between West and East, an appeal to the origins of Russian culture in the field of language, folk verbal creativity, folk mythology” (Philosophical Context of Russian Literature 1920-1930s, 2003: 265). As an example, the researcher cites, among other things, Plato's article “The Rise of the East”, in which there is such a declaration: “The East is cheerful, young and strong. The East is a Bolshevik. The paw of capitalist Europe only leaned on him, but he immediately smelled his death under its claws and rushed, not knowing and not wanting to know European “culture”. The nerves of the world are now intertwined in his heart; his thoughts will beat there, and not in Europe. However, the authors of the commentary to the first volume of the collected works of Platonov connect the words quoted above with the national liberation struggle of the Eastern peoples. In their opinion, the article should be considered the writer's response to such publications in the central press. It would be appropriate to mention here the Platonic negative review of the work of the Eurasian philosopher L. Karsavin "Noctes Petropolitanae". It says, in part: “The whole book is a concoction of the concepts of a rotten, weary brain. The author has no idea about real human love. For him, love is religion, philosophy, literature, anything, but not the cry of the future, not the movement of the seed, not physiology, not warmth, not courage, and not physical strength that exterminates bad generations, not the work of the sun.

The paw of capitalist Europe only leaned on him, but he immediately smelled his death under its claws and rushed, not knowing and not wanting to know European “culture”. The nerves of the world are now intertwined in his heart; his thoughts will beat there, and not in Europe. However, the authors of the commentary to the first volume of the collected works of Platonov connect the words quoted above with the national liberation struggle of the Eastern peoples. In their opinion, the article should be considered the writer's response to such publications in the central press. It would be appropriate to mention here the Platonic negative review of the work of the Eurasian philosopher L. Karsavin "Noctes Petropolitanae". It says, in part: “The whole book is a concoction of the concepts of a rotten, weary brain. The author has no idea about real human love. For him, love is religion, philosophy, literature, anything, but not the cry of the future, not the movement of the seed, not physiology, not warmth, not courage, and not physical strength that exterminates bad generations, not the work of the sun. 0053 9 . If Platonov was influenced by Eurasianism, then to an insignificant degree.

0053 9 . If Platonov was influenced by Eurasianism, then to an insignificant degree.

In the 1922 article "Symphony of Consciousness", the writer outlined his impressions of reading "The Decline of Europe" by O. Spengler. Undoubtedly, the book shocked Platonov. According to N. Kornienko, the philosopher's words that "lyrics" should give priority to "technique" could have been put by the writer as an epigraph to many of his works of this period. In addition, the researcher emphasizes: “In The Decline of Europe, Platonov’s attention is attracted by Spengler’s “morphology of history”, the logic of his arguments about the inevitable crisis and death of any culture, including European. "Death", "catastrophe" of Europe - in the loss of the "soul" of culture, which leads to a dead end, a "wall" and a change in the paradigm of European life - through the "Sunset of Europe" Platonov pronounces the painful questions of the present, past and future of Russia "(Kornienko, 1995:18). However, Platonov's attitude to the German philosopher was not so unequivocal. In the mentioned article, along with praise for the latter, there is also such a reproach: “Spengler has an organic, not a mechanics of words; his philosophy is a song, not a calculated technique of logic. And Spengler is a dangerous man. He is such an artist of words that he can write any kind of nonsense, but write so, so triumphantly confidently, blindingly write that everyone will believe him, and he will laugh at everyone afterwards. But let him not hope, not everyone is equally fascinated by beauty - there are things more important and more beautiful than beauty.0053 10 . Interesting observations by E. Tikhomirova, who believes that Platonov recognized the susceptibility of any culture to age-related changes, however, in general, was focused on polemics with Spengler. The researcher comes to the conclusion that the idea of "the irreversibility of the course of cultural time is opposed by Platonov's belief in the effectiveness of human efforts" (Tikhomirova, 1992: 14).

However, Platonov's attitude to the German philosopher was not so unequivocal. In the mentioned article, along with praise for the latter, there is also such a reproach: “Spengler has an organic, not a mechanics of words; his philosophy is a song, not a calculated technique of logic. And Spengler is a dangerous man. He is such an artist of words that he can write any kind of nonsense, but write so, so triumphantly confidently, blindingly write that everyone will believe him, and he will laugh at everyone afterwards. But let him not hope, not everyone is equally fascinated by beauty - there are things more important and more beautiful than beauty.0053 10 . Interesting observations by E. Tikhomirova, who believes that Platonov recognized the susceptibility of any culture to age-related changes, however, in general, was focused on polemics with Spengler. The researcher comes to the conclusion that the idea of "the irreversibility of the course of cultural time is opposed by Platonov's belief in the effectiveness of human efforts" (Tikhomirova, 1992: 14). In turn, A. Dyrdin emphasizes the paradoxical nature of the philosopher's influence on the writer. In his opinion, Platonov, criticizing the morphology of Spengler's history in journalism, followed the course of his reflections in artistic creativity, picking up ready-made formulas. A. Dyrdin is convinced that the writer “criticizes not the idea of “The Decline of Europe”, but the absence of an organizing core in it” (Dyrdin, 1999:51).

In turn, A. Dyrdin emphasizes the paradoxical nature of the philosopher's influence on the writer. In his opinion, Platonov, criticizing the morphology of Spengler's history in journalism, followed the course of his reflections in artistic creativity, picking up ready-made formulas. A. Dyrdin is convinced that the writer “criticizes not the idea of “The Decline of Europe”, but the absence of an organizing core in it” (Dyrdin, 1999:51).

Platonov's interest is the relationship between science and religion. He considers it in connection with the search for means to achieve immortality. According to the writer, earlier mankind “searched for the forces of life in religion, in the power of God, but now they saw that they were mistaken and went on to another, more true path - the path of science, knowledge, understanding and subjugation for their own purposes of all interbreeding, mutually destroying, meaningless forces” 11 . Platonov believed that the Bolshevik coup not only destroyed the foundations of the Christian worldview, but also prevented the possibility of the emergence of a new religion. He explains this by saying that the revolution “is the daughter of science, and science is hostile to any faith, to any dark, unexplained movement of the soul, to any passion that flows not from consciousness, not from thought, but from the dark depths of man” 12 . This claim seems unconvincing. In the work “The Extraordinary Adventures of Science in Utopia and Dystopia (H. Wells, O. Huxley, A. Platonov)”, T. Novikova proves that in the process of “merging with totalitarian power, science appropriates the unusual functions of planting a new religion. At the same time, knowledge loses its educational character and, in alliance with utopian ideology, replaces spiritual and moral values with soulless materialism, demagogy and fruitless fantasies” (Novikova, 1998:199).

He explains this by saying that the revolution “is the daughter of science, and science is hostile to any faith, to any dark, unexplained movement of the soul, to any passion that flows not from consciousness, not from thought, but from the dark depths of man” 12 . This claim seems unconvincing. In the work “The Extraordinary Adventures of Science in Utopia and Dystopia (H. Wells, O. Huxley, A. Platonov)”, T. Novikova proves that in the process of “merging with totalitarian power, science appropriates the unusual functions of planting a new religion. At the same time, knowledge loses its educational character and, in alliance with utopian ideology, replaces spiritual and moral values with soulless materialism, demagogy and fruitless fantasies” (Novikova, 1998:199).

The writer actively uses biblical phraseology and symbolism. This can be judged even by the headlines of the materials: "Transfiguration", "Christ and Us", "Hallowed be Thy Name", "The New Gospel", "Bread Pilgrims". Interestingly, his image of Christ is fundamentally different from the gospel. Platonov writes: "Christ, the great prophet of anger and hope, was turned by his servants into a preacher of obedience to the blind world and brutal rapists" 13 . And further: “People saw God in Christ, we know him as our friend. He is not yours, temples and priests, but ours. He has been dead for a long time, but we are doing his work - and he is alive in us.0053 14 . According to I. Spiridonova, in the writer's publicistic speeches, "Christ gradually loses his divine essence altogether" (Spiridonova, 1994: 353). Such a filling of the image of the messiah, the researcher believes, is necessary for Platonov “to justify revolutionary violence, to sanctify it with the name of God” (ibid.: 354). I. Spiridonova comes to the conclusion that the writer professed anthropotheism, or man-godism. In this regard, we can recall the following Platonic lines: “Man is the father of God. Man, the life that beats in him, is the unified power of the universe from the beginning to the end of time.

Interestingly, his image of Christ is fundamentally different from the gospel. Platonov writes: "Christ, the great prophet of anger and hope, was turned by his servants into a preacher of obedience to the blind world and brutal rapists" 13 . And further: “People saw God in Christ, we know him as our friend. He is not yours, temples and priests, but ours. He has been dead for a long time, but we are doing his work - and he is alive in us.0053 14 . According to I. Spiridonova, in the writer's publicistic speeches, "Christ gradually loses his divine essence altogether" (Spiridonova, 1994: 353). Such a filling of the image of the messiah, the researcher believes, is necessary for Platonov “to justify revolutionary violence, to sanctify it with the name of God” (ibid.: 354). I. Spiridonova comes to the conclusion that the writer professed anthropotheism, or man-godism. In this regard, we can recall the following Platonic lines: “Man is the father of God. Man, the life that beats in him, is the unified power of the universe from the beginning to the end of time. God is an image drawn by the hand of man in a free desire to fill life with the joy of creativity.0053 15 . It is obvious that a substitution, a revolution is taking place here: it is no longer a man who is the image and likeness of God, but God (with a lowercase letter) is created by the hand of an almighty Man.

God is an image drawn by the hand of man in a free desire to fill life with the joy of creativity.0053 15 . It is obvious that a substitution, a revolution is taking place here: it is no longer a man who is the image and likeness of God, but God (with a lowercase letter) is created by the hand of an almighty Man.

One can not agree with all the theses of the article by I. Spiridonova “Christian and anti-Christian tendencies in the work of Andrei Platonov in the 1910-1920s”. In addition, some of them are in conflict with each other. So, at first the researcher writes that “when declaring war on the old world order, the young proletarian artist Andrey Platonov does not declare war on its Creator. And if Platonov of the first post-revolutionary years can be called an atheist, in the sense that he does not see God as the main organizer of the Kingdom of God on earth, then he cannot be an anti-theist (a God-fighter) ”(ibid.: 352). And two pages later: “Line 19The period from 10 to 1920 was not just a period of departure, but a break between Platonov and the faith of the fathers. And although it was during this period that Platonic journalism was extremely saturated with biblical vocabulary and symbols, in content it was not only anti-church, but also anti-Christian” (ibid.: 354). A. Varlamov takes a more understandable position on this issue. He is convinced that Platonov was very upset by the loss of his childhood faith in God. However, the Platonic feeling of God-forsakenness, according to A. Varlamov, was caused “not only by fatigue, disappointment and blows of fate, but first and foremost by the peculiar Russian religiosity of the rebellion, the impatience of a young heart, unwillingness to put up with evil, death, suffering and thirst for an immediate reorganization, transformation of the world. (Varlamov, 2011: 24).

And although it was during this period that Platonic journalism was extremely saturated with biblical vocabulary and symbols, in content it was not only anti-church, but also anti-Christian” (ibid.: 354). A. Varlamov takes a more understandable position on this issue. He is convinced that Platonov was very upset by the loss of his childhood faith in God. However, the Platonic feeling of God-forsakenness, according to A. Varlamov, was caused “not only by fatigue, disappointment and blows of fate, but first and foremost by the peculiar Russian religiosity of the rebellion, the impatience of a young heart, unwillingness to put up with evil, death, suffering and thirst for an immediate reorganization, transformation of the world. (Varlamov, 2011: 24).

A number of Platonov's diary entries dedicated to the theme of religion belong to the same period. For example, in 1921, in his notebook, he quotes the author of the famous treatise “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”: ““God is dead, now we want the superman to live. ” Nietzsche. That is: God, come close to me, become me, but the best, the highest me - super me, superman. It is simply a "realization of God", like the whole doctrine of the superman" 16 . I. Spiridonova believes that the writer "from the depths of people's life comes to the conclusion that Nietzsche proclaimed earlier from the elite peaks of European culture." (Spiridonova, 1994:352). The theme of the "dead god" is already heard in Platonov's verses of the 1910s:

” Nietzsche. That is: God, come close to me, become me, but the best, the highest me - super me, superman. It is simply a "realization of God", like the whole doctrine of the superman" 16 . I. Spiridonova believes that the writer "from the depths of people's life comes to the conclusion that Nietzsche proclaimed earlier from the elite peaks of European culture." (Spiridonova, 1994:352). The theme of the "dead god" is already heard in Platonov's verses of the 1910s:

Through the villages of the bell

Weep for the dead god.

Once upon a time there was love

And the wanderer fell on the road 17 .

Attention is drawn to the parable written by Platonov about two people who, after death, came to the judgment of God. One of them led an ascetic life, mortifying his body, the other lived for his own pleasure, taking care of the earthly. After listening to them, God (with a capital letter) says: “Both of you wanted one thing - life and left it, one - into an inanimate spirit, [the other] because he mortified the body, the other - into a dead body, [for] for he forgot everything except body. And both of you are dead. But behold, if you would comprehend that the spirit and the flesh are one, both would be eternally alive and rejoicing in My joy.” 18 . K. Barsht correlates this parable with the main motive of "Matter and Memory" by A. Bergson. The intuitive philosopher believed that there were only three epistemological possibilities: the application of the spirit to things, the adaptation of things to the spirit, the coherence of things and the spirit. According to K. Barsht, Bergson, like Platonov, is not satisfied with any of the options: “Both thinkers feel that things and spirit do not just agree or combine with each other, but form an indissoluble unity, the innermost meaning of which is the main direction of human search. » (Barsht, 2007: 146). The researcher notes that the writer talked about the connection between the two sides of the living "substance" of the Universe from the first steps of his creative path.

And both of you are dead. But behold, if you would comprehend that the spirit and the flesh are one, both would be eternally alive and rejoicing in My joy.” 18 . K. Barsht correlates this parable with the main motive of "Matter and Memory" by A. Bergson. The intuitive philosopher believed that there were only three epistemological possibilities: the application of the spirit to things, the adaptation of things to the spirit, the coherence of things and the spirit. According to K. Barsht, Bergson, like Platonov, is not satisfied with any of the options: “Both thinkers feel that things and spirit do not just agree or combine with each other, but form an indissoluble unity, the innermost meaning of which is the main direction of human search. » (Barsht, 2007: 146). The researcher notes that the writer talked about the connection between the two sides of the living "substance" of the Universe from the first steps of his creative path.

No less interesting is the tale "Faith, Knowledge and Doubt". Its main idea is that the “eternal bride of God” Vera gave her light to every soul and therefore she herself dissipated: “Vera was everywhere - and nowhere was she. This is because she exchanged her mighty single Light for millions of sparks” 19 . Further, Platonov explains: “[So] Faith [gold] disappeared from the Light, because She exchanged her gold of confidence and hope for coppers of Knowledge with [the money changer] Doubt, and left the gold with the money changer of Doubt” 20 . This tale is accompanied by an entry in which the writer expresses the same thought without allegories: “There is a God and there is no God. Both are correct. God became spontaneous, etc., that he was divided among everything — and thus, as it were, was destroyed. And his “heirs”, having in themselves the “coal” of God, say he does not exist - and it is true. Or there is - others say - and it is true too. This is all atheism and all religion” 21 . The authors of the commentary to Platonov's Notebooks believe that these words reflect the writer's interpretation of the doctrine of unity, which occupied one of the central places in Russian philosophy of that time.

Its main idea is that the “eternal bride of God” Vera gave her light to every soul and therefore she herself dissipated: “Vera was everywhere - and nowhere was she. This is because she exchanged her mighty single Light for millions of sparks” 19 . Further, Platonov explains: “[So] Faith [gold] disappeared from the Light, because She exchanged her gold of confidence and hope for coppers of Knowledge with [the money changer] Doubt, and left the gold with the money changer of Doubt” 20 . This tale is accompanied by an entry in which the writer expresses the same thought without allegories: “There is a God and there is no God. Both are correct. God became spontaneous, etc., that he was divided among everything — and thus, as it were, was destroyed. And his “heirs”, having in themselves the “coal” of God, say he does not exist - and it is true. Or there is - others say - and it is true too. This is all atheism and all religion” 21 . The authors of the commentary to Platonov's Notebooks believe that these words reflect the writer's interpretation of the doctrine of unity, which occupied one of the central places in Russian philosophy of that time. It was expressed most fundamentally in the works of Vl. Solovyov. But it seems important to I. Spiridonova that Platonov “does not see an impenetrable wall between the warring “for” and “against” God: Christians and atheists, and does not exclude the latter from the heirs of God, who carry his “coal” in themselves” (Spiridonova, 1994:350). The researcher cites this passage as evidence of the writer's slow return to God.

It was expressed most fundamentally in the works of Vl. Solovyov. But it seems important to I. Spiridonova that Platonov “does not see an impenetrable wall between the warring “for” and “against” God: Christians and atheists, and does not exclude the latter from the heirs of God, who carry his “coal” in themselves” (Spiridonova, 1994:350). The researcher cites this passage as evidence of the writer's slow return to God.

One of the leading literary and public associations of the post-revolutionary years was Proletkult, headed by A. Bogdanov. His most significant work, called Tectology, had a noticeable influence on Platonov's philosophical and aesthetic views. Following Bogdanov, the writer believed that art in the Soviet state should solve organizational and construction problems. However, the fascination with the theory of proletarian culture did not prevent Platonov from questioning some of its postulates. In his early writings, he quite often expressed the most general judgments concerning the nature of art and its purpose. If science, in his opinion, is an objective observation of everything that exists, then art should be engaged in the search for the most harmonious state of the world, the organization of chaos. At the same time, the writer believed that the point of “objective, out-of-relative observation coincides with the center of a perfect organization. Only by moving away from the world and from oneself can one see what all this is and what all this wants to be. Science and art in their highest states coincide, and there they are one.0053 22 .

If science, in his opinion, is an objective observation of everything that exists, then art should be engaged in the search for the most harmonious state of the world, the organization of chaos. At the same time, the writer believed that the point of “objective, out-of-relative observation coincides with the center of a perfect organization. Only by moving away from the world and from oneself can one see what all this is and what all this wants to be. Science and art in their highest states coincide, and there they are one.0053 22 .

Platonov contrasts collective creativity with individual creativity. Songs, legends, epics, legends, myths, the author of which is the people, he calls "the peaks of expression of the deepest feelings, the cradle and source of true universal art" 23 . The anonymity of such literary works was important to him. According to Platonov, the individual creative activity of modern times is "artificial art". The writer was convinced of the need to return to ancient patterns. This “way back”, from his point of view, could only be done by proletarian art, which “reflects in itself all of humanity in its best aspirations, and it is also created by all of humanity, by the entire harmonious organized collective” 24 .

This “way back”, from his point of view, could only be done by proletarian art, which “reflects in itself all of humanity in its best aspirations, and it is also created by all of humanity, by the entire harmonious organized collective” 24 .

Sometimes Platonov tries to reason like a literary theorist, but more often he uses figurative poetic constructions. Here is the definition given by the writer in his notebook: “Art consists in expressing the most complex through the simplest. It is the highest form of economy” 25 . Or another - from the article "To Beginning Proletarian Poets and Writers": "Art, generally speaking, is the process of passing the forces of nature through the human being" 26 . At the beginning of 1924, Platonov's review of one of the issues of the LEF magazine was published, in which he clearly expresses his position. According to the writer, disputes about the art of that time were reduced to choosing one of two theses: “1) Art is the knowledge of life (comrade Voronsky, comrade Trotsky), 2) Art is a method of building life (comrade Chuzhak, Lef)” 27 . Lunacharsky's formula ("Art is the adornment of life") he did not even take into account, calling it "aesthetic". Andrei Platonov is often attributed to the authors who sympathize with the Pereval group, however, it must be emphasized that in the review mentioned, he takes the side of Chuzhak, and not Voronsky, declaring that “Comrade. Voronsky took Hegel's thesis without the slightest alteration and established himself on it.0053 28 . Further, the reviewer writes: “No one will object to the fact that art affects emotion, i.e. organizes it in a certain direction. This is undeniable. But to organize emotion means to organize human activity through emotion, in other words, to build life. This, of course, is crude and scholastic, but it is not my task to prove the correctness of Comrade's thesis. Stranger. He himself does it quite convincingly” 29 . By the way, at the end of the 1920s, Platonov, in an unpublished preface to the story “For the future”, will again argue with the “passengers”.

Lunacharsky's formula ("Art is the adornment of life") he did not even take into account, calling it "aesthetic". Andrei Platonov is often attributed to the authors who sympathize with the Pereval group, however, it must be emphasized that in the review mentioned, he takes the side of Chuzhak, and not Voronsky, declaring that “Comrade. Voronsky took Hegel's thesis without the slightest alteration and established himself on it.0053 28 . Further, the reviewer writes: “No one will object to the fact that art affects emotion, i.e. organizes it in a certain direction. This is undeniable. But to organize emotion means to organize human activity through emotion, in other words, to build life. This, of course, is crude and scholastic, but it is not my task to prove the correctness of Comrade's thesis. Stranger. He himself does it quite convincingly” 29 . By the way, at the end of the 1920s, Platonov, in an unpublished preface to the story “For the future”, will again argue with the “passengers”. The subject of controversy will be the idea of "mozartism", put forward by Voronsky's wards.

The subject of controversy will be the idea of "mozartism", put forward by Voronsky's wards.

In general, Platonov was inclined to assign a secondary, service role to artistic creativity. In the article “Culture of the Proletariat,” he stated: “But art is still a false work. And it is still difficult to say whether art will survive in its present form under the dominance of consciousness. Most likely, it will merge into science, which will rise from this and be transformed in many ways” 30 . However, the writer himself continued to create numerous poems and stories. This once again showed the immanent inconsistency of the Platonic worldview.

The ideas of Platonov the publicist were transformed in his science fiction stories of the first half of the 1920s: "Markun", "Descendants of the Sun", "Satan of Thought", "Moon Bomb".

T. Novikova notes that, despite “the clearly utopian mood of Platonov’s early prose, we will not find in it a single case of the unconditional victory of science over nature: its achievements are rather presented as episodic or random phenomena. It is also curious that the heroes of these stories - the scientists - the rebuilders of the world, do not look like winners: lonely losers, they, as a rule, become victims of bold and grandiose utopian projects, which are the plot core of Plato's texts" (Novikova, 1998:188). So, Markun, a character in the story of the same name, is trying to build an engine that runs on water. Its power, according to the inventor, should be limited only by the strength of the metal from which the motors are made. During the test, an unusual machine explodes. According to T. Novikova, the unfavorable ending symbolizes “the enormous but dangerous potential of science in the service of utopian thought” (ibid.: 189). A more interesting interpretation is offered by S. Brel. Mentioning the theory of Clausius, which, having entered the sphere of culture at the beginning of the 20th century, was demonized, the researcher introduces the concept of “anti-entropic poetics”. In his opinion, Platonov “realized on an intuitive level that no doctrine, including the theory of entropy, can give an exhaustive explanation of the global processes taking place in the universe.

It is also curious that the heroes of these stories - the scientists - the rebuilders of the world, do not look like winners: lonely losers, they, as a rule, become victims of bold and grandiose utopian projects, which are the plot core of Plato's texts" (Novikova, 1998:188). So, Markun, a character in the story of the same name, is trying to build an engine that runs on water. Its power, according to the inventor, should be limited only by the strength of the metal from which the motors are made. During the test, an unusual machine explodes. According to T. Novikova, the unfavorable ending symbolizes “the enormous but dangerous potential of science in the service of utopian thought” (ibid.: 189). A more interesting interpretation is offered by S. Brel. Mentioning the theory of Clausius, which, having entered the sphere of culture at the beginning of the 20th century, was demonized, the researcher introduces the concept of “anti-entropic poetics”. In his opinion, Platonov “realized on an intuitive level that no doctrine, including the theory of entropy, can give an exhaustive explanation of the global processes taking place in the universe. Here he only outstripped the physical ideas of his era, saw the danger not only in the dispersion of energy, but also in its excessive ordering. (Brel, 2003: 333). One more remark by S. Brel is important. Markun understands that he made not a technical, but a moral miscalculation, and overcomes his own egoism.

Here he only outstripped the physical ideas of his era, saw the danger not only in the dispersion of energy, but also in its excessive ordering. (Brel, 2003: 333). One more remark by S. Brel is important. Markun understands that he made not a technical, but a moral miscalculation, and overcomes his own egoism.

One cannot pass by Platonov's "The Story of Many Interesting Things" written in 1923. The character of this work, Durable Man, created a science called "individual anthropotechnics" and organized two workshops - durable and immortal flesh. He himself tells about his experiment in the following way: “Strong flesh in a person becomes chastity, while the liberated terrible sexual force turns in such a person into a talent for inventions. Only and everything. This is a small workshop, only preparatory. And immortal flesh is already being made from strong, chaste flesh by means of electricity.” 31 . The attention of S. Semenova was attracted by the first part of the Strong Man project. The researcher is convinced that Platonov “connects here to the ancient tradition, which was looking for ways of such a transmutation of sexual energy, in the same hope that it would lead to the transformation of a person, the achievement of his immortality, an unprecedented strengthening of consciousness: this is, to a certain extent, Plato with his teachings about Eros as a “striving for immortality”, and Christian Gnostics, and Chinese Taoists, and Eastern Tantrics, and, finally, are already close to us and to the thought of Platonov himself, the idea of “positive chastity” Fedorov and the “meaning of love” Vl. Solovyov" (Semenova, 2001: 485). N. Malygina, in turn, speaks of the connection between Plato's "anthropotechnics" and the one developed in 1920s A. Chizhevsky theory of organic electrical exchange. Probably, the young reclamation engineer was interested in the impact of electricity on the living world and followed the discoveries in this area. Platonov gravitated toward a scientific and technical solution to the problem of personality, but did not lose sight of the moral aspect.

The researcher is convinced that Platonov “connects here to the ancient tradition, which was looking for ways of such a transmutation of sexual energy, in the same hope that it would lead to the transformation of a person, the achievement of his immortality, an unprecedented strengthening of consciousness: this is, to a certain extent, Plato with his teachings about Eros as a “striving for immortality”, and Christian Gnostics, and Chinese Taoists, and Eastern Tantrics, and, finally, are already close to us and to the thought of Platonov himself, the idea of “positive chastity” Fedorov and the “meaning of love” Vl. Solovyov" (Semenova, 2001: 485). N. Malygina, in turn, speaks of the connection between Plato's "anthropotechnics" and the one developed in 1920s A. Chizhevsky theory of organic electrical exchange. Probably, the young reclamation engineer was interested in the impact of electricity on the living world and followed the discoveries in this area. Platonov gravitated toward a scientific and technical solution to the problem of personality, but did not lose sight of the moral aspect. N. Malygina also dwells on the fifth chapter of the "Story." In which Platonov reflects on the nature of the word. The writer claims: “The strength of a person lies in the preservation and repetition of countless times of the soul in a word” 32 . This is followed by a replica of the protagonist Ivan Kopchikov: “The men make bread. Dads are guys. Carpenters are at home. And I will make good souls out of scattered, lost words” 33 . According to the researcher, this episode gives grounds to speak of "the aesthetic beginning in the Platonic program, which was strengthened by the identification of labor and science with art" (Malygina, 1977: 164).

N. Malygina also dwells on the fifth chapter of the "Story." In which Platonov reflects on the nature of the word. The writer claims: “The strength of a person lies in the preservation and repetition of countless times of the soul in a word” 32 . This is followed by a replica of the protagonist Ivan Kopchikov: “The men make bread. Dads are guys. Carpenters are at home. And I will make good souls out of scattered, lost words” 33 . According to the researcher, this episode gives grounds to speak of "the aesthetic beginning in the Platonic program, which was strengthened by the identification of labor and science with art" (Malygina, 1977: 164).

Platonov's position gradually became less dogmatic. Already in his early stories, he abandons the most radical projects for the reorganization of the Earth and the Universe, coming to the idea that it is necessary to first explore and then transform. At the same time, “research should go in both directions: both outward, into the infinity of the world, and into the same depth of the inner universe of man” (Semenova, 2001: 484). The final overcoming of youthful maximalism by the writer will happen a little later.

The final overcoming of youthful maximalism by the writer will happen a little later.

Notes

1 Platonov A.P. Notebooks. M., 2006. S. 100.

2 Platonov A.P. Op. T. 1. 1918-1927. Book. 2: Articles / Chap. ed. N.V. Kornienko. M., 2004. S. 34.

3 Ibid. S. 93.

4 Ibid. S. 95.

5 Platonov A.P. Doubting Makar: Stories of the 1920s; Poems / Entry. Art. A. Bitova; Ed. N.M. Malygina. M., 2011. S. 469.

6 Platonov A.P. Op. S. 95.

7 Ibid. S. 49.

8 Ibid. S. 58.

9 Ibid. pp. 227-228.

10 Platonov A.P. Op. S. 222.

11 Platonov A.P. Op. S. 66.

12 Ibid. S. 77.

13 Ibid. S. 27.

14 Ibid. S. 28.

15 Ibid. S. 76.

16 Platonov A.P. Notebooks. S. 17.

17 Platonov A.P. Doubting Makar... S. 421.

18 Platonov A.P. Notebooks. S. 19.

19 Ibid. S. 22.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid. S. 257.

22 Platonov A.P. Op. pp. 163-164.

23 Ibid. P. 10.

24 Ibid. S. 9.

25 Platonov A.P. Notebooks. S. 22.

26 Platonov A.P. Op. P. 10.

27 Ibid. S. 259.

28 Ibid. S. 260.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid. S. 100.

31 Platonov A.P. Doubting Makar... S. 379.

32 Platonov A.P. Doubting Makar... S. 353.

33 Ibid.

Bibliography

Balburov E.A. "Artistic epistemology" by Andrei Platonov in the light of the philosophical searches of Russian cosmists // Humanit. science in Siberia. 1999. No. 4.

Barsht K.A. Truth in a round and liquid form. Henri Bergson in Andrey Platonov's "Pit" // Questions of Philosophy. 2007. No. 4.

Brel S.V. Aesthetics of Platonov in the context of ideas about entropy // "Country of Philosophers" by Andrey Platonov: problems of creativity. Issue. 5. M., 2003.

Varlamov A.N. Andrey Platonov. M., 2011.

Vasiliev V.V. Andrey Platonov. Essay on life and creativity. M., 1982.

Essay on life and creativity. M., 1982.

Dyrdin A.A. Andrey Platonov and Oswald Spengler: philosophical image of nature and history // Vestn. Ulyan. tech. university 1999. No. 4.

Kornienko N.V. Text history and biography of A.P. Platonova (1926-1946) // Here and now. 1993. No. 1.

Kornienko N.V. About some lessons of textology // Creativity of Andrey Platonov: Research and materials. Bibliography. SPb., 1995.

Malygina N.M. Ideological and aesthetic searches of A. Platonov in the early 20s (“A story about many interesting things”) // Russian Literature. 1977. No. 4.

Malygina N.M. Natural-scientific sources and ideas about the nature of Andrei Platonov // Man and nature in artistic prose. Interuniversity. Sat. scientific tr. / Syktyvkar. state University named after the 50th anniversary of the USSR. Syktyvkar, 1981.

Novikova T. Extraordinary adventures of science in utopia and dystopia (H. Wells, O. Huxley, A. Platonov) // Questions of Literature.