Emergent literacy in early childhood

Emergent Literacy | ECLKC

Although language and literacy are two different skills, they are closely related. Language is the ability to both use and understand spoken words or signs. It is all about ideas passing from one person to another. Literacy is the ability to use and understand written words or symbols to communicate. Language and literacy learning begins prenatally! The child begins to learn the sounds and rhythms of his or her home language in the womb and can begin a love of reading by being read to as a newborn.

Emergent literacy has been defined as "those behaviors shown by very young children as they begin to respond to and approximate reading and writing acts." However, literacy goes beyond reading and writing. It encompasses "the interrelatedness of language: speaking, listening, reading, writing, and viewing."

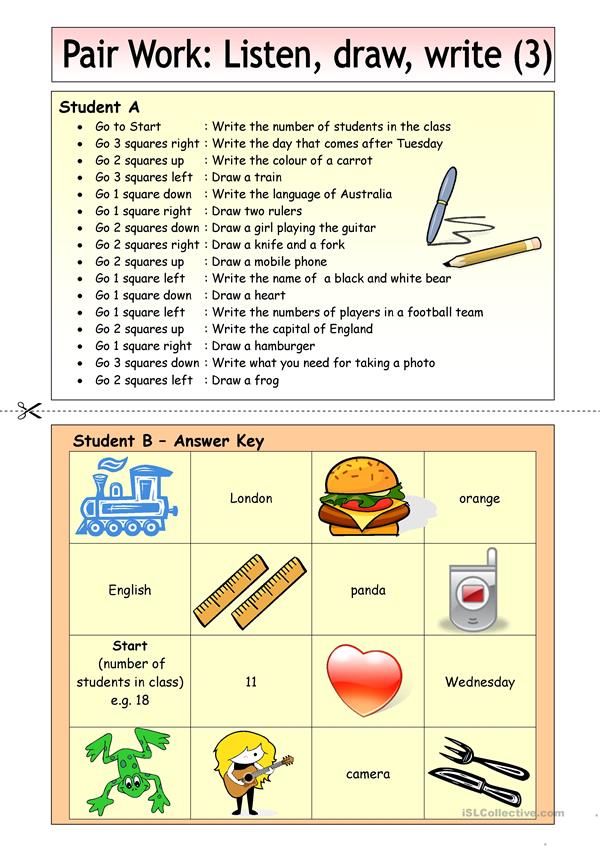

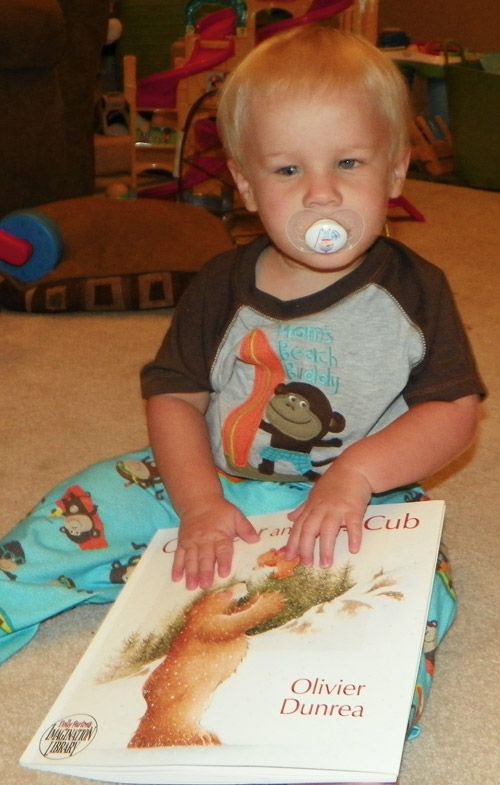

There are many ways for young children, including infants and toddlers, to engage with books:

- Holding, tasting, and turning the pages

- Having an adult hold the child while reading a book

- Pointing to and talking about the pictures

- Inviting the child to finish or join in saying repetitive phrases

- Asking questions

Near the end of the first year of life, children begin to understand that pictures represent real objects and understand the meaning of about 50 words. By 18 months, the child knows 1,800 words and, given exposure to rich language and literacy experiences, is rapidly learning new words every day.

Daily reading to a child, or even telling little nursery rhymes from birth, significantly improves a child's ability to read and write.

How To

You support emergent language and literacy by supporting families in:

- Maintaining and passing on their home language to their children, which helps children connect to their families and have a strong, positive cultural identity of their own

- It is easier for children to become fluent English speakers if they have a solid foundation in their home language

- The young brain is fertile ground for learning two or more languages at once

- Using "parent-ese," talking to an infant with slower speech and exaggerated vowel sounds, to help the baby figure out the sounds of his or her home language (e.g., "mmaaaammaaaa")

- Directing a toddler's interest to a sound in the environment (e.

g., "Listen, that's mama's phone ringing.") or pointing a toddler's attention to a word that has the same beginning sound as her name (e.g., "Do you hear the sound of banana? Ba, banana. Ba. It sounds like your name, Bai.")

g., "Listen, that's mama's phone ringing.") or pointing a toddler's attention to a word that has the same beginning sound as her name (e.g., "Do you hear the sound of banana? Ba, banana. Ba. It sounds like your name, Bai.") - Responding appropriately to infants' coos, gestures, and body movements and all the ways infants and toddlers communicate before they use language

- For example, when an 8-month-old points to something, look at what the baby points to. These are the beginnings of conversation!

- Describing what the child is doing (e.g., "Sarah can't take her eyes off of you while she's breastfeeding.")

- Adding elaborations to the words children say; for example:

- If a toddler points and says "truck," the parents might extend this by saying, "Yes, that is a garbage truck emptying our dumpster," or, "I think you hear the sirens of the fire truck."

- Talking directly to children from early infancy about what they see or experience (e.

g., "You're looking at me. Yes! A smile. I love your smile. A smile for Daddy.")

g., "You're looking at me. Yes! A smile. I love your smile. A smile for Daddy.") - Talking about things you are doing (e.g., "I'm making a sandwich. First, I'll wash my hands. Then, I'll get out the bread.")

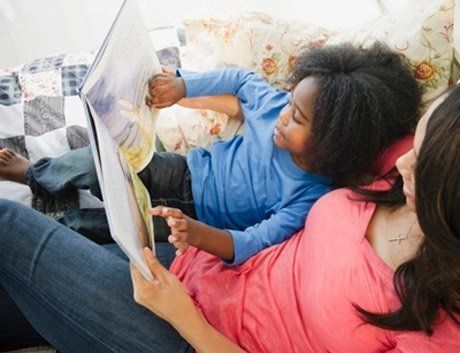

- Reading and sharing stories with young children

- Engaging young children in learning vocabulary by using rich language to talk about the pictures and stories in a book, asking questions while reading, and pointing to pictures as parents describe them; for example:

- "That baby is smiling. Can you touch his mouth? He's happy."

- "What's going to happen to the next monkey jumping on the bed?"

- Pointing out familiar icons, such as a stop sign or the name on the grocery store, as well as shapes, colors, and letters in the environment

- Pointing out written words that have meanings to toddlers, such as their names and the names of family members

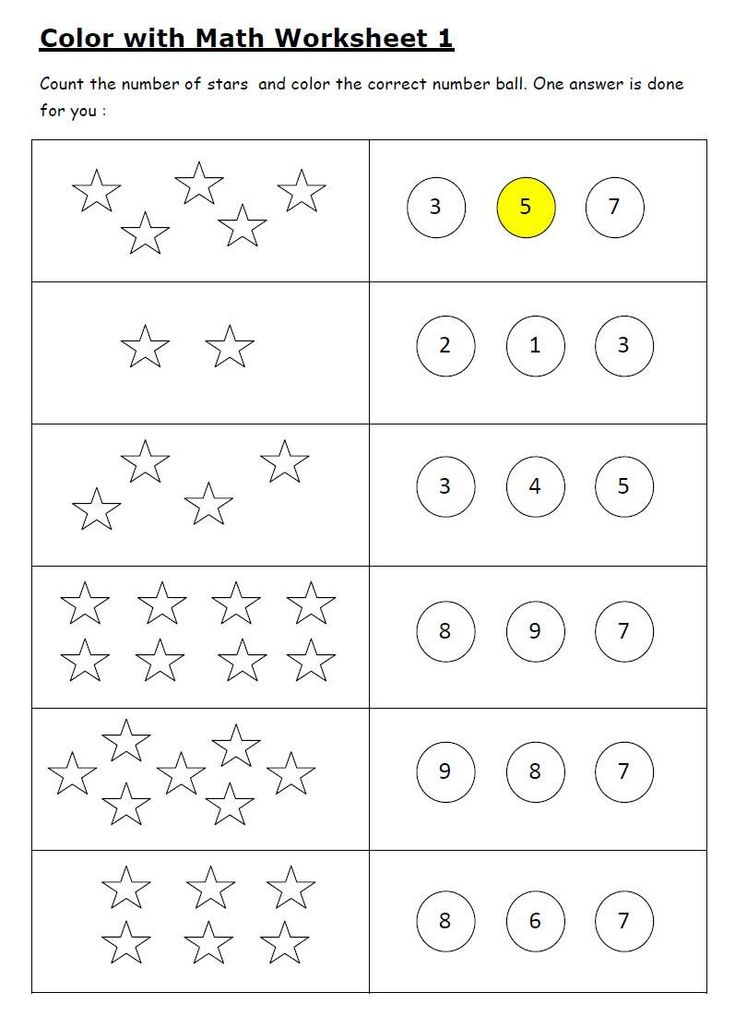

- Counting fingers and saying rhymes during handwashing; thus, you have touched on a healthy behavior and layered it with literacy and math

- Following a recipe and reading it out loud

- Providing markers and crayons for making the most of everyday writing, such helping to "write" grocery lists, thank you notes, etc.

- Visiting the library, getting library cards, and attending a toddler's reading experience

Adapted from News You Can Use: Foundations of School Readiness: Language and Literacy.

Emergent Literacy: Experience It

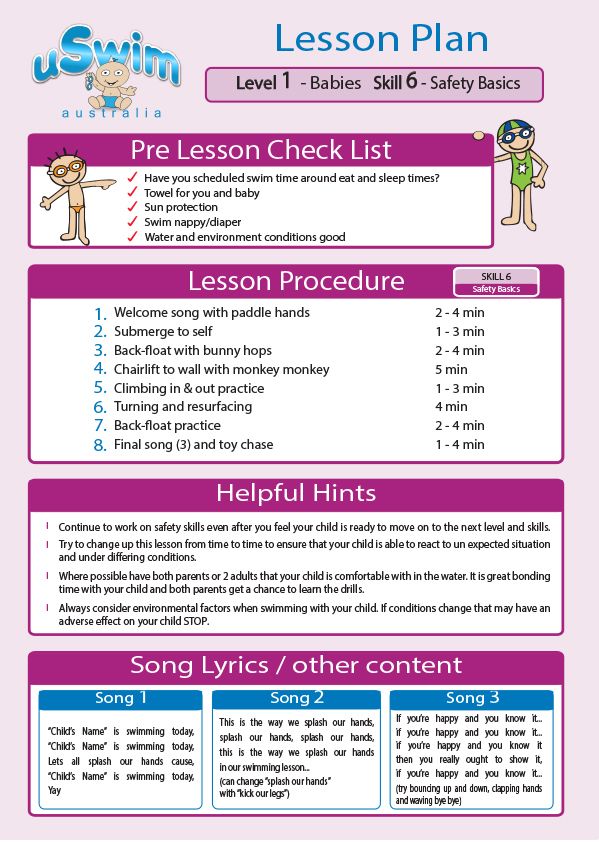

In this clip, a mother and baby look through a book together, naming objects and turning pages. The home visitor sits nearby, coaching and supporting the mother as she and the child enjoy the book together.

Emergent Literacy: Infants

Download the video[MP4, 36MB] Download the transcript

View the transcript

Open Doors

Chapter 8c: Emergent Literacy Experience It

Mom: What is that?

Michael: Bird.

Mom: Bird.

Michael: Owl.

Mom: Owl. Soft.

Michael: Dad!

Mom: Look.

Michael: Bird. Mom! Eh.

Mom! Eh.

Mom: That's a bird.

Home Visitor: That's a bird.

Home Visitor: Mom will read it. You want Mom to read it?

Mom: Bird.

Home Visitor: Oh, look at the bird.

Mom: [gasp] Green.

Michael: Oh.

Michael: Eh.

Mom: Frog.

Michael: Eh. Eh.

Mom: Bird.

Home Visitor: It's a touch-and-feel, so he can feel the texture.

Michael: Bug!

Mom: Bug, ladybug. Soft. Red. Creature. [gasp] Ew, look at this. Hard.

Michael: Bird.

Mom: Butterfly.

Michael: Eh. Eh.

Mom: Look, it's hard. Hard crab.

Home Visitor: And just having him repeat that. "Do you know that one?"

Michael: Fly!

Mom: Michael.

Michael: Fly!

Home Visitor: No! Crab.

Michael: Fly!

Mom: Say, "crab." Michael too, crab. Look! Kangaroo. Soft. Michael, too. Say "soft kangaroo."

Home Visitor: Wow! It's a kangaroo. Yeah, soft.

Mom: Say "soft".

Michael: Eh.

Mom: Bear. Brown bear. There's the bird. Fish. Yellow. A yellow fish. Look right there. I'll show you another one. Look, rough. Wrinkly. Wrinkly. Flamingo! Piglets. Where's the piglets? That's a dolphin. You remember watching the dolphin last night? Dolphin. Say "rhinoceros". Wrinkly rhinoceros.

Fish. Yellow. A yellow fish. Look right there. I'll show you another one. Look, rough. Wrinkly. Wrinkly. Flamingo! Piglets. Where's the piglets? That's a dolphin. You remember watching the dolphin last night? Dolphin. Say "rhinoceros". Wrinkly rhinoceros.

Michael: Eh.

Mom: Where's the mouse? Say "mouse."

Michael: Where?

Mom: "Mouse."

Michael: Eh.

Mom: "Mouse." Say "pig."

Michael: Pig.

Mom: Pigs. Piglets. One more. One more.

Michael: One!

Mom: Say "black and white". Soft. Zebra. Silky zebra.

Home Visitor: Zebra! Wow! Let me try feeling that. Ooh, soft.

Michael: Eh.

Mom: Tail. Smooth.

Michael: Wow!

Mom: Kangaroo.

Michael: Ooh.

Mom: Kangaroo.

Home Visitor: Kangaroo. Does he like to do rhymes and --?

Michael: Bye.

Home Visitor: Or you've tried that?

Mom: Not really. I never tried that.

Home Visitor: Would you want to try like every -- [Sneeze] Ooh! Bless you.

Mom: Bless you.

Michael: Eh.

Home Visitor: And that would help out with his speech, too. And repeating over, like in a week, and see how he's doing, that would be a good --

Mom: Yeah.

Home Visitor: Like even short little rhymes or songs or --

Mom: Kangaroo.

Home Visitor: And even have them like posted on the wall and just that would be a good --

Mom: Say "zebra."

Home Visitor: Even like while you're cooking, you just sing to him more.

Mom: I usually try to let him sing the ABCs with me, but --

Michael: [gasp] Wow!

Mom: He only says a couple and run away.

Home Visitor: Oh. I mean, even if you just sing it and maybe he can catch on.

Mom: Where's the kangaroo?

Michael: Hmm?

Mom: Kangaroo.

Michael: Hmm?

Mom: Zebra.

Michael: Eh.

Mom: Zebra. Kangaroo! The same page. Kangaroo.

Michael: Hi.

Home Visitor: Kangaroo.

Michael: [Laughs]

Close

Reflections

What do you observe?

Answers may include:

- Mother and baby are holding the book.

- Baby is pointing at objects in the book and turning the pages.

- Mother is saying what is on the page and baby is making sounds.

- Baby is on the mother's lap. He briefly climbs off her lap, then back on.

- The home visitor is sitting at the side.

- At one point, the baby looks at the home visitor and says something, and the home visitor says, "Kangaroo."

- The home visitor is coaching the mother about the child's language development, talking about repeating words and how children learn.

- Mother asks the baby where the kangaroo is. He turns a page, and the mother says, "Zebra."

- Baby puts the book on his head and laughs.

What does the mother do to support the child's emergent literacy?

Answers may include:

- She follows his lead, letting him do what he wants with the book, such as turning pages and putting it on his head.

- She says the words he points to rather than reading the book straight through.

- She holds him on her lap so they are experiencing physical closeness.

- Mother repeats the words more than once: "Kangaroo, kangaroo; zebra, zebra."

What does the home visitor do to support the continuation of the activity? What does she do to enhance the parent-child relationship?

Answers may include:

- She uses a positive tone.

- She describes and comments on what the parent is doing specifically rather than just saying, "Good job."

- She talks to the mother and credits her for the accomplishments of her son.

- She sits nearby but lets the mother guide the reading activity.

- The home visitor coaches the mother on some things she could try to enhance her child's speech.

What is the child learning from this experience?

Answers may include:

- Perceptual, Motor, and Physical Development

- Eye-hand coordination

- Fine motor skills (e.g., turning pages, pointing)

- Gross motor skills (e.

g., climbing up and down from Mom's lap).

g., climbing up and down from Mom's lap).

- Social and Emotional Development

- Self-esteem from his successes and acknowledgement from others

- Taking pleasure in his own activity and sharing it with both his mother and the home visitor

- Approaches to Learning

- Self-regulation and persistence (e.g., continuing to try to turn pages or name animals)

- Problem-solving (e.g., figuring out what animals are on the page)

- Attention (e.g., maintaining focus on and interest in the book)

- Language and Literacy

- Receptive language (e.g., listening to his mother say the words in the book and the home visitor repeating the word for the picture he is pointing to)

- Expressive language (e.g., when his mother says the words, the child tries to repeat them, making sounds throughout the clip)

- Literacy (e.g., enjoying books, turning pages, identifying objects in the book that represent other objects (animals))

- Cognition

- Learning how objects in the book represent animals he may have seen previously

- Pointing to objects (animals) and naming them

How can you enhance your home visits based on what you have observed?

Answers may include:

- Various reflections

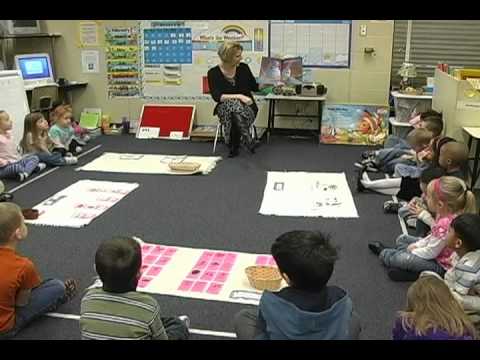

See a home visitor demonstrating how to identify an object in the book and find the matching object on the floor. Best practice suggests the parent should read the book. Notice how the home visitor turns the book over to the mother so she can promote her child's emergent literacy.

Best practice suggests the parent should read the book. Notice how the home visitor turns the book over to the mother so she can promote her child's emergent literacy.

Emergent Literacy: Toddlers/Preschoolers

Download the video[MP4, 4.3MB] Download the transcript

View the transcript

Open Doors

Chapter 8d: Emergent Literacy Experience It

Home Visitor: Let me see what else we can find in our alphabet book. Wow! Let's see. Does Mommy see anything? Maybe, Mommy can like point out something for us to find in our alphabet book that we see down here.

Mom: Well, I see one on the last page, an eggplant.

Home Visitor: Okay. You want to turn until you find something? You can pick out what we find.

Brenna: [singing] Eggs. Eggs. Eggs. Eggs. Eggs.

Mom: Brenna, can you find the eggplant?

Close

Reflections

What do you observe?

Answers may include:

- The home visitor asks what can be found in the alphabet book and then asks if the mother can find something in the alphabet book.

- Isaiah, the boy, stirs in the bowl and then picks up a plastic carrot and pretends to eat.

- Linea, the girl, points to an object in the book.

- The mother says she sees one, and the home visitor turns the book over to the mother and asks her to turn until she finds something.

- Isaiah climbs into Mom's lap and picks up a piece of plastic melon.

- Mom asks if the children can find an eggplant.

What strategies does the home visitor use to promote emergent language and literacy development?

Answers may include:

- Home visitor engages the mother directly by asking her to interact with her child and the book.

- Home visitor provides concrete objects and visual and auditory cues for the parent and child to help develop language and literacy skills.

- Home visitor models the specific language learning skill she wants the parent to communicate with her child (e.g., "Can you find something in the book [that matches a fruit or vegetable on the floor]?")

- Home visitor establishes appropriate boundaries by encouraging the mother and child to engage in the activity together.

- Home visitor encourages the mother to recreate the experience she models with her children.

- She introduces the book and book reading.

How might the home visitor achieve similar goals with materials found in the home?

Answers may include:

- Take pictures of food and other objects found in the home and make books

- Use food or other objects found in the family's home as concrete objects to match with objects found in a book

- Cut out pictures in magazines to match objects

- Identify objects in the environment

- Read the print on cereal boxes, newspapers, and magazines

- Pretend to write during pretend play (e.

g., checks in a restaurant, invoices for purchases, to-do or shopping lists)

g., checks in a restaurant, invoices for purchases, to-do or shopping lists)

What other developmental domains do you observe?

Answers may include:

- Social and Emotional Development

- The child climbs in the mother's lap

- The mother speaks to her child gently

- One of the children smiles during the video clip

- Perceptual, Motor, and Physical Development

- They discuss vegetables and fruits

- Isaiah grasps and stirs

- Isaiah balances and climbs on Mom's lap

- Linea points, using eye-hand coordination

- Approaches to Learning

- Attention: Both children attend to the home visitor and their mother

- Curiosity: Isaiah explores the characteristics of the plastic fruit and vegetables

- Information gathering: Isaiah is learning about plastic fruit with his hands and mouth

- Cognition

- Pretend play: Isaiah uses the fruit to stir in the bowl and pretends to taste the carrot

- Connecting experiences and information: Isaiah and Linea are learning and comparing the characteristics of plastic fruit and vegetables, pictures of fruit and vegetables, and real fruits and vegetables in their experience

What other reflections do you have?

Answers may include:

- What more might you like to know about the children and family to support their development?

- What other strategies would you consider to promote language and literacy with this family?

Emergent Literacy: Learn More

News You Can Use: Foundations of School Readiness: Language and Literacy

Infants and toddlers learn about language and literacy through meaningful interactions with nurturing adults. Discover strategies teachers, home visitors, and family child care providers can use to support children's emerging language and literacy skills. A study guide accompanies the resource.

Discover strategies teachers, home visitors, and family child care providers can use to support children's emerging language and literacy skills. A study guide accompanies the resource.

Emergent literacy has been defined as "those behaviors shown by very young children as they begin to respond to and approximate reading and writing acts."

Braunger, J. & Lewis, J.P. (1998) Building a Knowledge base in reading. Newark, DE: International Reading Association (p. 16).

Read more:

Home visiting, Literacy, Language

School Readiness

Resource Type: Article

National Centers: Early Childhood Development, Teaching and Learning

Last Updated: March 18, 2022

Emergent Literacy

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), 2006

Emergent Literacy: Early Reading and Writing Development

Froma P. Roth, PhD, CCC-SLP

Diane R. Paul, PhD, CCC-SLP

Ann-Mari Pierotti, MA, CCC-SLP

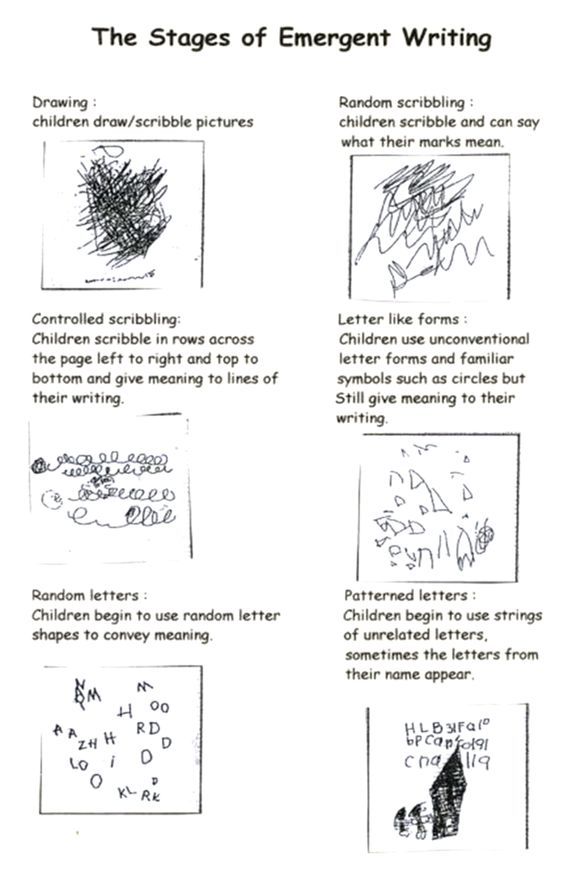

Children start to learn language from the day they are born. As they grow and develop, their speech and language skills become increasingly more complex. They learn to understand and use language to express their ideas, thoughts, and feelings, and to communicate with others. During early speech and language development, children learn skills that are important to the development of literacy (reading and writing). This stage, known as emergent literacy, begins at birth and continues through the preschool years. Children see and interact with print (e.g., books, magazines, grocery lists) in everyday situations (e.g., home, in preschool, and at daycare) well before they start elementary school. Parents can see their child's growing appreciation and enjoyment of print as he or she begins to recognize words that rhyme, scribble with crayons, point out logos and street signs, and name some letters of the alphabet. Gradually, children combine what they know about speaking and listening with what they know about print and become ready to learn to read and write.

As they grow and develop, their speech and language skills become increasingly more complex. They learn to understand and use language to express their ideas, thoughts, and feelings, and to communicate with others. During early speech and language development, children learn skills that are important to the development of literacy (reading and writing). This stage, known as emergent literacy, begins at birth and continues through the preschool years. Children see and interact with print (e.g., books, magazines, grocery lists) in everyday situations (e.g., home, in preschool, and at daycare) well before they start elementary school. Parents can see their child's growing appreciation and enjoyment of print as he or she begins to recognize words that rhyme, scribble with crayons, point out logos and street signs, and name some letters of the alphabet. Gradually, children combine what they know about speaking and listening with what they know about print and become ready to learn to read and write.

Are Spoken Language and Literacy Connected?

Yes. The experiences with talking and listening gained during the preschool period prepare children to learn to read and write during the early elementary school years. This means that children who enter school with weaker verbal abilities are much more likely to experience difficulties learning literacy skills than those who do not. One spoken language skill that is strongly connected to early reading and writing is phonological awareness-the recognition that words are made up of separate speech sounds, for example, that the word dog is composed of three sounds: d, aw, g. There are a variety of oral language activities that show children's natural development of phonological awareness, including rhyming (e.g., "cat-hat") and alliteration (e.g., "big bears bounce on beds"), and isolating sounds ("Mom, f is the first sound in the word fish"). As children playfully engage in sound play, they eventually learn to segment words into their separate sounds, and "map" sounds onto printed letters, which allows them to begin to learn to read and write. Children who perform well on sound awareness tasks become successful readers and writers, while children who struggle with such tasks often do not.

Children who perform well on sound awareness tasks become successful readers and writers, while children who struggle with such tasks often do not.

Who Is at Risk?

There are some early signs that may place a child at risk for the acquisition of literacy skills. Preschool children with speech and language disorders often experience problems learning to read and write when they enter school. Other factors include physical or medical conditions (e.g., preterm birth requiring placement in a neonatal intensive care unit, chronic ear infections, fetal alcohol syndrome, cerebral palsy), developmental disorders (e.g., intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum), poverty, home literacy environment, and family history of language or literacy disabilities.

Early Warning Signs

Signs that may indicate later reading and writing and learning problems include persistent baby talk, absence of interest in or appreciation for nursery rhymes or shared book reading, difficulty understanding simple directions, difficulty learning (or remembering) names of letters, failure to recognize or identify letters in the child's own name.

Role of the Speech-Language Pathologist

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) have a key role in promoting the emergent literacy skills of all children, and especially those with known or suspected literacy-related learning difficulties. The SLP may help to prevent such problems, identify children at risk for reading and writing difficulties, and provide intervention to remediate literacy-related difficulties. Prevention efforts involve working in collaboration with families, caregivers, and teachers to ensure that young children have high quality and ample opportunities to participate in emergent literacy activities both at home and in daycare and preschool environments. SLPs also help older children or those with developmental delays who have missed such opportunities. Children who have difficulty grasping emergent literacy games and activities may be referred for further assessment so that intervention can begin as early as possible to foster growth in needed areas and increase the likelihood of successful learning and academic achievement.

Early Intervention Is Critical

Emergent literacy instruction is most beneficial when it begins early in the preschool period because these difficulties are persistent and often affect children's further language and literacy learning throughout the school years. Promoting literacy development, however, is not confined to young children. Older children, particularly those with speech and language impairments, may be functioning in the emergent literacy stage and require intervention aimed at establishing and strengthening these skills that are essential to learning to read and write.

What Parents Can Do

You can help your child develop literacy skills during regular activities without adding extra time to your day. There also are things you can do during planned play and reading times. Show your children that reading and writing are a part of everyday life and can be fun and enjoyable. Activities for preschool children include the following:

- Talk to your child and name objects, people, and events in the everyday environment.

- Repeat your child's strings of sounds (e.g., "dadadada, bababa") and add to them.

- Talk to your child during daily routine activities such as bath or mealtime and respond to his or her questions.

- Draw your child's attention to print in everyday settings such as traffic signs, store logos, and food containers.

- Introduce new vocabulary words during holidays and special activities such as outings to the zoo, the park, and so on.

- Engage your child in singing, rhyming games, and nursery rhymes.

- Read picture and story books that focus on sounds, rhymes, and alliteration (words that start with the same sound, as found in Dr. Seuss books).

- Reread your child's favorite book(s).

- Focus your child's attention on books by pointing to words and pictures as you read.

- Provide a variety of materials to encourage drawing and scribbling (e.g., crayons, paper, markers, finger paints).

- Encourage your child to describe or tell a story about his/her drawing and write down the words.

If you have concerns about your child's speech and language development or emergent literacy skills, please contact a certified speech-language pathologist. Go to ASHA's Web site at www.asha.org for more information and referrals, or call 800-638-8255.

Literacy and its Impact on Child Development: Comments on Articles Tomblin and Sénéchal

Introduction

The concept of “literacy” has taken center stage in early education only in the last decade. Prior to this, experts rarely considered literacy as a critical aspect of the healthy growth and development of young children. The current level of reading problems among schoolchildren remains unacceptably high. The data show that about 40% of fourth grade students have difficulty reading even at the elementary level, and that there are a disproportionate number of poor children and children from ethnic or racial minorities among children with reading problems. 1 A paradigm shift over the past decade, spurred by the 1998 publication Prevention of Reading Difficulties in Young Children by the United States National Research Council, has emphasized the importance of early education as a context within which addressing the identified urgent issues is likely to be effective. Early childhood education is the period during which young children develop skills, knowledge and interest in the symbolic and semantic foundations of written and spoken language. In this paper, I interpret these abilities and interests as "pre-literacy" abilities in order to emphasize their role as precursors of traditionally understood literacy. To date, attention to pre-literacy as an integral element of early childhood education stems from two emerging areas of research that show that:

Early childhood education is the period during which young children develop skills, knowledge and interest in the symbolic and semantic foundations of written and spoken language. In this paper, I interpret these abilities and interests as "pre-literacy" abilities in order to emphasize their role as precursors of traditionally understood literacy. To date, attention to pre-literacy as an integral element of early childhood education stems from two emerging areas of research that show that:

- Individual differences in pre-literacy skills among children are meaningfully important – early-onset differences contribute significantly to longitudinal measures of reading performance; 2

- The prevalence of reading problems is more likely to be affected by prevention than by remedial education, because if a particular child falls behind in reading in primary school, it is more likely that a return to healthy progress will not occur. 3

Research and findings

Experts Tomblin and Seneschal discuss current and important aspects of the current literature on the development of pre-literacy and its short- and long-term relationships with other age-related competencies. According to my reading of the text of their papers, there are three critical areas that require further development: decoding predictors, the language-literacy relationship, and the role of temperament and motivation.

According to my reading of the text of their papers, there are three critical areas that require further development: decoding predictors, the language-literacy relationship, and the role of temperament and motivation.

First, the current cumulative research literature on the development of early literacy skills and the relationship of this development to later reading outcomes identifies three unique predictors of reading competence: phonological processing, knowledge of printed letters and what they are used for, and spoken language. 2 While the first two aspects directly prepare children for acquiring word skills (eg decoding), the third aspect prepares them for text comprehension with little or no effect on decoding. Tomblin aptly points out that reading competence requires both decoding skills and comprehension skills, and the Seneschal emphasizes that children need to first "learn to read" before "reading to learn." It should be understood that the relationship between the two aspects of reading is multiplicative—meaning that both sides of the equation (Decoding x Comprehension = Reading) require any value other than 0 for the reading to be functional. 4 Both Tomblin and the Seneschal do not emphasize enough the importance of developing early decoding precursors in children. Children will never be able to read to learn (i.e. understand) unless they are able to successfully decode. Children who start learning basic reading with inadequate pre-literacy skills will not be able to keep up with decoding educational information, which will slow down the final transition to reading for the sake of understanding the meaning of what they read. Early education is a period during which educators can almost easily improve children's chances of learning to become a reader by gaining initial alphabetic skills (printing and phonological awareness) that will enable children to benefit from the process of decoding directions while learning.

4 Both Tomblin and the Seneschal do not emphasize enough the importance of developing early decoding precursors in children. Children will never be able to read to learn (i.e. understand) unless they are able to successfully decode. Children who start learning basic reading with inadequate pre-literacy skills will not be able to keep up with decoding educational information, which will slow down the final transition to reading for the sake of understanding the meaning of what they read. Early education is a period during which educators can almost easily improve children's chances of learning to become a reader by gaining initial alphabetic skills (printing and phonological awareness) that will enable children to benefit from the process of decoding directions while learning.

Second, both Tomblin and Seneschal emphasize the importance of the role of spoken language in literacy development, although they do not emphasize the relationship between literacy and language development. Scholars are increasingly inclined to view the integrative relationship between language and literacy as interdependent. Engaging children in literacy-related activities, such as reading a storybook or listening to rhymes, requires a metalinguistic focus that focuses on spoken or written language. The continuous involvement of children in literacy classes and their growing tendency to consider language as an object of attention are becoming the first routes of language development. Once children begin to read, even at the most elementary level, reading texts becomes the richest source of new words and concepts, complex syntax, and narrative structures that stimulate further language development. In short, literacy is the most important vehicle for the development of language competencies in children, both in the preschool period and during the periods of initial and subsequent schooling. The relationship between language and literacy is more than a one-way street – language provides a platform for the exploration and experiential learning of written language, which in turn shapes children's later language competencies.

Scholars are increasingly inclined to view the integrative relationship between language and literacy as interdependent. Engaging children in literacy-related activities, such as reading a storybook or listening to rhymes, requires a metalinguistic focus that focuses on spoken or written language. The continuous involvement of children in literacy classes and their growing tendency to consider language as an object of attention are becoming the first routes of language development. Once children begin to read, even at the most elementary level, reading texts becomes the richest source of new words and concepts, complex syntax, and narrative structures that stimulate further language development. In short, literacy is the most important vehicle for the development of language competencies in children, both in the preschool period and during the periods of initial and subsequent schooling. The relationship between language and literacy is more than a one-way street – language provides a platform for the exploration and experiential learning of written language, which in turn shapes children's later language competencies.

Third, further consideration needs to be given to the role of temperament and motivation in influencing children's achievement and experience in teaching pre-literacy skills, as Tomblin and Seneschal's findings are insufficient. Tomblin notes overlap between internalizing behaviors (such as anxiety and depression) and literacy difficulties, and Seneschal notes that some children may avoid reading, especially those who feel they do not read well enough. The role of early motivation, self-esteem, and temperament in the development of pre-literacy requires more attention overall, especially when we consider opportunities to stimulate other intrinsic competencies (eg, phonological processing and vocabulary) in prevention programs. Most early education educators know that motivating children to become literate is one of the most important contributions to successful pre-literacy. By trying to experience literacy on their own or in the context of interacting with others, children themselves correct the process of developing pre-literacy! A small, though largely consistent, body of research shows that children's motivation and engagement in literacy activities varies greatly for each child and is relatively related to the individual child's benefit from the activity. 5 Some children actively resist pre-literacy experiences, such as reading a storybook, and children with poor language skills or children who do not receive any literacy experiences at home are more likely to resist involvement in development activities. The scientific literature is still unable to explain why some children resist participation in literacy classes and how this resistance generally correlates with the child's temperament. However, approaches to encouraging young children to become involved in literacy activities and motivate them to become literate need to be considered as one of the most important characteristics of developing effective interventions.

5 Some children actively resist pre-literacy experiences, such as reading a storybook, and children with poor language skills or children who do not receive any literacy experiences at home are more likely to resist involvement in development activities. The scientific literature is still unable to explain why some children resist participation in literacy classes and how this resistance generally correlates with the child's temperament. However, approaches to encouraging young children to become involved in literacy activities and motivate them to become literate need to be considered as one of the most important characteristics of developing effective interventions.

Recommendations for policy makers and services

Modern perspectives for policy makers and services emerge from three scientific findings reported in the literature. First, children with an underdeveloped oral language base will be very vulnerable in the context of acquiring reading competence, which in turn hinders continuous language development. Secondly, it is much more difficult to correct existing reading problems than to prevent them. Third, it appears possible to increase children's chances of acquiring literacy skills through high-quality, intensive, systemic pre-literacy programs implemented in pre-schools and kindergartens before children develop reading problems.

Secondly, it is much more difficult to correct existing reading problems than to prevent them. Third, it appears possible to increase children's chances of acquiring literacy skills through high-quality, intensive, systemic pre-literacy programs implemented in pre-schools and kindergartens before children develop reading problems.

Integrating policy, practice and research

Significant gaps remain in integrating policy, practice and research, and in producing research that can be safely applied to existing programs. Tomblin emphasizes the need for further research into the mechanisms that cause literacy problems in children with language difficulties. Research into these mechanisms is one of the most developed and well-funded areas of research in the United States, and has unequivocally shown the importance of spoken language, phonological processing, and capitalization commonly associated with a child's ability to read. What is needed now is a closer look at ways to stimulate the linkage between policymaking, practice and research to ensure that current efforts to improve literacy rates in young children, especially those who start these programs with low levels of language and literacy, are effective. The Seneschal puts forward several evidence-based proposals to encourage the development of literacy skills in young children, such as word games and book reading. Further scrutiny should be given to the extent to which these activities are effective for children with poor language proficiency, have a longitudinal positive effect, and can be incorporated into existing interventions.

The Seneschal puts forward several evidence-based proposals to encourage the development of literacy skills in young children, such as word games and book reading. Further scrutiny should be given to the extent to which these activities are effective for children with poor language proficiency, have a longitudinal positive effect, and can be incorporated into existing interventions.

Does quality matter?

Policy makers, practitioners and researchers have rarely considered the importance of the quality of interaction between adults and children in relation to literacy, whether it be word games or book reading. Theories of the development of pre-literacy skills in children suggest that the quality of the interaction is of great importance because children's skills progress faster and more easily in the course of such learning interaction, which is characterized by empathetic, responsive and under-involved adults. When implementing systematic, evidence-based remedial interventions aimed at early literacy development, the quality of these interventions by the teacher can vary significantly, and these differences, apparently, are the cause of a significant difference in the level of literacy of children. When we develop policies and services to serve young children to reduce the risk of reading difficulties through remedial programs, we must ensure that children's relationships and interactions with adults are of high quality, providing a context within which knowledge, skills and interests are developed. .

When we develop policies and services to serve young children to reduce the risk of reading difficulties through remedial programs, we must ensure that children's relationships and interactions with adults are of high quality, providing a context within which knowledge, skills and interests are developed. .

Literature

- National Assessment of Education Progress. The Nation's Report Card. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/. Accessed February 4, 2005.

- Storch SA, Whitehurst GJ. Oral language and code-related precursors to reading: Evidence from a longitudinal structural model. Developmental Psychology 2002;38(6):934-947.

- Juel C, Griffith PL, Gough PB. Acquisition of literacy: A longitudinal study of children in first and second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology 1986;78(4):243-255.

- Gough PB, Tunmer WE. Decoding, reading, and reading disability. RASE: Remedial and Special Education 1986;7(1):6-10.

- Justice LM, Chow SM, Capellini C, Flanigan K, Colton S. Emergent literacy intervention for vulnerable preschoolers: Relative effects of two approaches. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2003;12(3):320-332.

Note:

Comments on original research published by Monique Seneschal in 2005. To access this article, please contact us at [email protected].

Is it necessary to teach a child to read before school and how is this related to the further reading literacy of children?

A study by our colleagues in the Laboratory showed that educational inequality manifests itself even before school. This is due to how differently they deal with children in families with different levels of cultural capital.

firestock

Many schools now have an unwritten rule that children must be able to read by the first grade. But visiting kindergartens in our country is not mandatory. In addition, the problem of their availability is also far from being solved everywhere. Therefore, this difficult task - the formation of early reading literacy - falls on the shoulders of parents.

Therefore, this difficult task - the formation of early reading literacy - falls on the shoulders of parents.

Andrey Zakharov and Anastasia Kapuza, members of the International Laboratory for Education Policy Analysis, decided to take a closer look at this issue and find out exactly how parents teach children to read in different families and what results these efforts bring.

Kapuza Anastasia Vasilievna

International Laboratory for Education Policy Analysis: Intern Researcher

We conducted a study based on the data of international monitoring PIRLS, which took place in 2011. It was attended by 4461 fourth-graders from 202 Russian schools. We were interested in how the level of literacy of children at school entry and in the 4th grade is associated with the cultural capital of the family, attendance at kindergarten, and various reading teaching practices used by parents with different levels of education.

How parents teach their children to read before school

Ways of teaching reading can be divided into formal and informal. Formal ones are more focused on the mechanics of the reading process. That is, on the perception and pronunciation of letters, syllables and words. For example, this is learning the alphabet or playing with words. In informal practices, more attention is paid to the comprehension of texts - this is the joint reading and discussion of books.

Formal ones are more focused on the mechanics of the reading process. That is, on the perception and pronunciation of letters, syllables and words. For example, this is learning the alphabet or playing with words. In informal practices, more attention is paid to the comprehension of texts - this is the joint reading and discussion of books.

Zakharov Andrey Borisovich

Deputy Head of the International Laboratory for Education Policy Analysis

In general, parents with higher education are more likely to start teaching their children to read before school. Moreover, strategies for engaging with children are also related to the level of education of parents. The longer a child goes to kindergarten, the more often parents without higher education work with him. That is, such children are taught to read both in the garden and at home. At the same time, parents more often use the whole diverse set of practices: both formal and informal. We called this approach “reinforcement strategy” . We assume that this strategy is a response to requests from kindergarten teachers who encourage parents to engage with their children.

We assume that this strategy is a response to requests from kindergarten teachers who encourage parents to engage with their children.

Parents with higher education use “compensation strategy” . In such families, they are more involved with children if they do not go to kindergarten. Moreover, such parents use predominantly informal practices - they try to instill in the child an interest in reading, are engaged in language development and general education.

The more often parents work with their children before school, the higher the level of children's reading literacy - both when they enter the first grade, and later, in the 4th grade. For children from families with a large amount of cultural capital, an increase in the level of reading literacy is associated with the use of informal practices by parents. But parents without higher education can apply any practice - the results of children will only get better.

Reading Literacy and Kindergarten

A child's progress in reading also depends on whether he attended kindergarten. This is very important for families with little cultural capital. The longer a child goes to kindergarten, the better he reads when entering school. This is due to the combined effect of the joint efforts of teachers and parents.

This is very important for families with little cultural capital. The longer a child goes to kindergarten, the better he reads when entering school. This is due to the combined effect of the joint efforts of teachers and parents.

But for children from families with a large amount of cultural capital, the duration of kindergarten attendance is not critical for their level of reading literacy.

- The compensation strategy probably works, the researchers conclude. - Parents with higher education compensated for the absence of a kindergarten by studying at home.

As a result, children from families with low cultural capital, who did not go to kindergarten, find themselves in the most difficult situation. They are less likely to learn to read by grade 1, because neither teachers nor parents teach them. Such children are more likely to lag behind their peers in the classroom at school.

Parental support for children's reading in the 4th grade

Of course, schools do not leave children who do not read well without attention. They are trying to somehow influence families. Parents without higher education are more likely to join classes with children in the 4th grade. Apparently, under the pressure of the school (on average, students from such families read worse), such parents begin to pay more attention to reading to children and discussing what they have read with them. But in 4th grade it may be too late for that.

They are trying to somehow influence families. Parents without higher education are more likely to join classes with children in the 4th grade. Apparently, under the pressure of the school (on average, students from such families read worse), such parents begin to pay more attention to reading to children and discussing what they have read with them. But in 4th grade it may be too late for that.

- We were surprised to see that frequent activities with children in the 4th grade were negatively associated with their reading literacy, the researchers say. - At first they didn't even believe it, so they made the same analysis for other PIRLS member countries. In many countries, the trend has repeated. This is explained by the fact that by the fourth grade children should already be able to read, and if they have to constantly do extra work with them at this age, it means that they have problems with reading.

Outgoing train

On the example of reading, we see that the strategies for teaching children, which are chosen by parents with different amounts of cultural capital, give different results:

Parents with higher education are involved in the education of children before school.