Every story is the same

From 'Avatar' to 'Jurassic Park,' 'Beowulf' to 'Jaws,' All Stories Are the Same

Culture

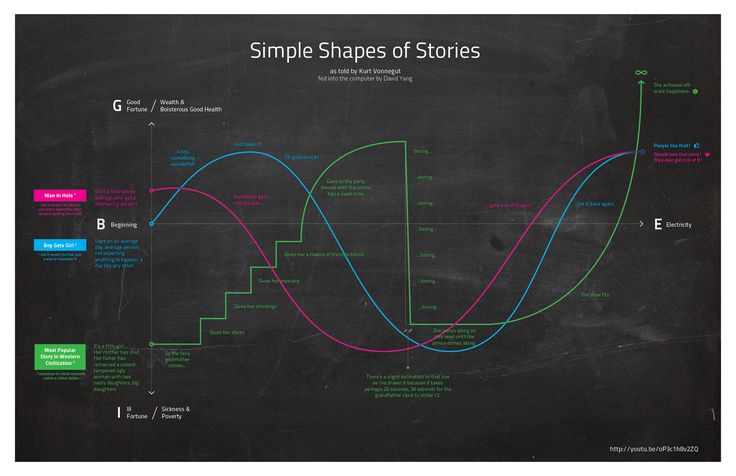

From Avatar to The Wizard of Oz, Aristotle to Shakespeare, there’s one clear form that dramatic storytelling has followed since its inception.

By John YorkeWikimediaA ship lands on an alien shore and a young man, desperate to prove himself, is tasked with befriending the inhabitants and extracting their secrets. Enchanted by their way of life, he falls in love with a local girl and starts to distrust his masters. Discovering their man has gone native, they in turn resolve to destroy both him and the native population once and for all.

Avatar or Pocahontas? As stories they’re almost identical. Some have even accused James Cameron of stealing the Native American myth. But it’s both simpler and more complex than that, for the underlying structure is common not only to these two tales, but to all of them.

Take three different stories:

A dangerous monster threatens a community. One man takes it on himself to kill the beast and restore happiness to the kingdom ...

It’s the story of Jaws, released in 1976. But it’s also the story of Beowulf, the Anglo-Saxon epic poem published some time between the eighth and 11th centuries.

And it’s more familiar than that: It’s The Thing, it’s Jurassic Park, it’s Godzilla, it’s The Blob—all films with real tangible monsters. If you recast the monsters in human form, it’s also every James Bond film, every episode of MI5, House, or CSI. You can see the same shape in The Exorcist, The Shining, Fatal Attraction, Scream, Psycho, and Saw. The monster may change from a literal one in Nightmare on Elm Street to a corporation in Erin Brockovich, but the underlying architecture—in which a foe is vanquished and order restored to a community—stays the same. The monster can be fire in

The Towering Inferno, an upturned boat in The Poseidon Adventure, or a boy’s mother in Ordinary People. Though superficially dissimilar, the skeletons of each are identical.

The monster can be fire in

The Towering Inferno, an upturned boat in The Poseidon Adventure, or a boy’s mother in Ordinary People. Though superficially dissimilar, the skeletons of each are identical.

Our hero stumbles into a brave new world. At first he is transfixed by its splendor and glamour, but slowly things become more sinister . . .

It’s Alice in Wonderland, but it’s also The Wizard of Oz, Life on Mars, and Gulliver’s Travels. And if you replace fantastical worlds with worlds that appear fantastical merely to the protagonists, then quickly you see how Brideshead Revisited, Rebecca, The Line of Beauty, and The Third Man all fit the pattern too.

When a community finds itself in peril and learns the solution lies in finding and retrieving an elixir far, far away, a member of the tribe takes it on themselves to undergo the perilous journey into the unknown .

..

It’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, Morte D’Arthur, Lord of the Rings, and Watership Down. And if you transplant it from fantasy into something a little more earthbound, it’s Master and Commander, Saving Private Ryan, Guns of Navarone, and Apocalypse Now. If you then change the object of the characters’ quest, you find Rififi, The Usual Suspects, Ocean’s Eleven, Easy Rider, and Thelma & Louise.

So three different tales turn out to have multiple derivatives. Does that mean that when you boil it down there are only three different types of story? No. Beowulf, Alien, and Jaws are ‘monster’ stories—but they’re also about individuals plunged into a new and terrifying world. In classic “quest” stories like Apocalypse Now or Finding Nemo the protagonists encounter both monsters and strange new worlds. Even “Brave New World” stories such as

Gulliver’s Travels, Witness, and Legally Blonde fit all three definitions: The characters all have some kind of quest, and all have their own monsters to vanquish too. Though they are superficially different, they all share the same framework and the same story engine: All plunge their characters into a strange new world; all involve a quest to find a way out of it; and in whatever form they choose to take, in every story “monsters” are vanquished. All, at some level, too, have as their goal safety, security, completion, and the importance of home.

Though they are superficially different, they all share the same framework and the same story engine: All plunge their characters into a strange new world; all involve a quest to find a way out of it; and in whatever form they choose to take, in every story “monsters” are vanquished. All, at some level, too, have as their goal safety, security, completion, and the importance of home.

But these tenets don’t just appear in films, novels, or indeed TV series like Homeland or The Killing. A 9-year-old child of my friend decided he wanted to tell a story. He didn’t consult anyone about it, he just wrote it down:

A family are looking forward to going on holiday. Mom has to sacrifice the holiday in order to pay the rent. Kids find map buried in garden to treasure hidden in the woods, and decide to go after it. They get in loads of trouble and are chased before they finally find it and go on even better holiday.

Why would a child unconsciously echo a story form that harks back centuries? Why, when writing so spontaneously, would he display knowledge of story structure that echoes so clearly generations of tales that have gone before? Why do we all continue to draw our stories from the very same well? It could be because each successive generation copies from the last, thus allowing a series of conventions to become established. But while that may help explain the ubiquity of the pattern, its sturdy resistance to iconoclasm and the freshness and joy with which it continues to reinvent itself suggest something else is going on.

But while that may help explain the ubiquity of the pattern, its sturdy resistance to iconoclasm and the freshness and joy with which it continues to reinvent itself suggest something else is going on.

Storytelling has a shape. It dominates the way all stories are told and can be traced back not just to the Renaissance, but to the very beginnings of the recorded word. It’s a structure that we absorb avidly whether in art-house or airport form and it’s a shape that may be—though we must be careful—a universal archetype.

Most writing on art is by people who are not artists: thus all the misconceptions.

—Eugène Delacroix

The quest to detect a universal story structure is not a new one. From the Prague School and the Russian Formalists of the early 20th century, via Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism to Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots, many have set themselves the task of trying to understand how stories work. In my own field it’s a veritable industry—there are hundreds of books about screenwriting (though almost nothing sensible about television). I’ve read most of them, but the more I read the more two issues nag away:

In my own field it’s a veritable industry—there are hundreds of books about screenwriting (though almost nothing sensible about television). I’ve read most of them, but the more I read the more two issues nag away:

1. Most of them posit completely different systems, all of which claim to be the sole and only way to write stories. How can they all possibly claim to be right?

2. None of them asks “Why?”

Some of these tomes contain invaluable information; more than a few have worthwhile insights; all of them are keen to tell us how and with great fervor insist that “there must be an inciting incident on page 12,” but none of them explains why this should be. Which, when you think about it, is crazy: If you can’t answer “why,” the “how” is an edifice built on sand. And then, once you attempt to answer it yourself, you start to realize that much of the theory—incisive though some of it is—doesn’t quite add up. Did God decree an inciting incident should occur on page 12, or that there were 12 stages to a hero’s journey? Of course not: They’re constructs. Unless we can find a coherent reason why these shapes exist, then there’s little reason to take these people seriously. They’re snake-oil salesmen, peddling their wares on the frontier.

Unless we can find a coherent reason why these shapes exist, then there’s little reason to take these people seriously. They’re snake-oil salesmen, peddling their wares on the frontier.

I’ve been telling stories for almost all my adult life, and I’ve had the extraordinary privilege of working on some of the most popular shows on British television. I’ve created storylines that have reached over 20 million viewers and I’ve been intimately involved with programs that helped redefine the dramatic landscape. I’ve worked, almost uniquely in the industry, on both art-house and populist mainstream programs, loved both equally, and the more I’ve told stories, the more I’ve realized that the underlying pattern of these plots—the ways in which an audience demands certain things—has an extraordinary uniformity.

Eight years ago I started to read everything on storytelling. More importantly I started to interrogate all the writers I’d worked with about how they write. Some embraced the conventions of three-act structure, some refuted it—and some refuted it while not realizing they used it anyway. A few writers swore by four acts, some by five; others claimed that there were no such things as acts at all. Some had conscientiously learned from screenwriting manuals while others decried structural theory as the devil’s spawn. But there was one unifying factor in every good script I read, whether authored by brand new talent or multiple award-winners, and that was that they all shared the same underlying structural traits.

A few writers swore by four acts, some by five; others claimed that there were no such things as acts at all. Some had conscientiously learned from screenwriting manuals while others decried structural theory as the devil’s spawn. But there was one unifying factor in every good script I read, whether authored by brand new talent or multiple award-winners, and that was that they all shared the same underlying structural traits.

By asking two simple questions—what were these traits; and why did they recur—I unlocked a cupboard crammed full of history. I soon discovered that the three-act paradigm was not an invention of the modern age but an articulation of something much more primal; that modern act structure was a reaction to dwindling audience attention spans and the invention of the curtain. Perhaps more intriguingly, the history of five-act drama took me back to the Romans, via the 19-century French dramatist Eugène Scribe and the German novelist Gustav Freytag to Molière, Shakespeare, and Jonson. I began to understand that, if there really was an archetype, it had to apply not just to screenwriting, but to all narrative structures. One either tells all stories according to a pattern or none at all. If storytelling does have a universal shape, this has to be self-evident.

I began to understand that, if there really was an archetype, it had to apply not just to screenwriting, but to all narrative structures. One either tells all stories according to a pattern or none at all. If storytelling does have a universal shape, this has to be self-evident.

* * *

When it comes to structure, how much do writers actually need to know? Here’s Guillermo Del Toro on film theory:

You have to liberate people from [it], not give them a corset in which they have to fit their story, their life, their emotions, the way they feel about the world. Our curse is that the film industry is 80 percent run by the half-informed. You have people who have read Joseph Campbell and Robert McKee, and now they’re talking to you about the hero’s journey, and you want to fucking cut off their dick and stuff it in their mouth.

Del Toro echoes the thoughts of many writers and filmmakers; there’s an ingrained belief for many that the study of structure is, implicitly, a betrayal of their genius; it’s where mediocrities seek a substitute muse. Such study can only end in one way. David Hare puts it well: “The audience is bored. It can predict the exhausted UCLA film-school formulae—acts, arcs, and personal journeys—from the moment that they start cranking. It’s angry and insulted by being offered so much Jung-for-Beginners, courtesy of Joseph Campbell. All great work is now outside genre.”

Such study can only end in one way. David Hare puts it well: “The audience is bored. It can predict the exhausted UCLA film-school formulae—acts, arcs, and personal journeys—from the moment that they start cranking. It’s angry and insulted by being offered so much Jung-for-Beginners, courtesy of Joseph Campbell. All great work is now outside genre.”

Charlie Kaufman, who has done more than most in Hollywood to push the boundaries of form, goes further: “There’s this inherent screenplay structure that everyone seems to be stuck on, this three-act thing. It doesn’t really interest me. I actually think I’m probably more interested in structure than most people who write screenplays, because I think about it.” But they protest too much. Hare’s study of addiction My Zinc Bed and Kaufman’s screenplay for Being John Malkovich are perfect examples of classic story form. However much they hate it (and their anger I think betrays them), they can’t help but follow a blueprint they profess to detest. Why?

Why?

All stories are forged from the same template, writers simply don’t have any choice as to the structure they use; the laws of physics, of logic, and of form dictate they must all follow the very same path.

Is this therefore the magic key to storytelling? Such hubris requires caution—the compulsion to order, to explain, to catalogue, is also the tendency of the train-spotter. In denying the rich variety and extraordinary multi-faceted nature of narrative, one risks becoming no better than Casaubon, the desiccated husk from Middlemarch, who turned his back on life while seeking to explain it. It’s all too tempting to reduce wonder to a scientific formula and unweave the rainbow.

But there are rules. As the creator of The West Wing and The Newsroom, Aaron Sorkin, puts it: “The real rules are the rules of drama, the rules that Aristotle talks about. The fake TV rules are the rules that dumb TV execs will tell you; ‘You can’t do this, you’ve got to do—you need three of these and five of those. ’ Those things are silly.” Sorkin expresses what all great artists know—that they need to have an understanding of craft. Every form of artistic composition, like any language, has a grammar, and that grammar, that structure, is not just a construct—it’s the most beautiful and intricate expression of the workings of the human mind.

’ Those things are silly.” Sorkin expresses what all great artists know—that they need to have an understanding of craft. Every form of artistic composition, like any language, has a grammar, and that grammar, that structure, is not just a construct—it’s the most beautiful and intricate expression of the workings of the human mind.

It’s important to assert that writers don’t need to understand structure. Many of the best have an uncanny ability to access story shape unconsciously, for it lies as much within their minds as it does in a 9-year-old’s.

There’s no doubt that for many those rules help. Friedrich Engels put it pithily: “Freedom is the recognition of necessity.” A piano played without knowledge of time and key soon becomes wearisome to listen to; following the conventions of form didn’t inhibit Beethoven, Mozart, and Shostakovich. Even if you’re going to break rules (and why shouldn’t you?) you have to have a solid grounding in them first. The modernist pioneers—Abstract Impressionists, Cubists, Surrealists, and Futurists—all were masters of figurative painting before they shattered the form. They had to know their restrictions before they could transcend them. As the art critic Robert Hughes observed:

The modernist pioneers—Abstract Impressionists, Cubists, Surrealists, and Futurists—all were masters of figurative painting before they shattered the form. They had to know their restrictions before they could transcend them. As the art critic Robert Hughes observed:

With scarcely an exception, every significant artist of the last hundred years, from Seurat to Matisse, from Picasso to Mondrian, from Beckmann to de Kooning, was drilled (or drilled himself ) in “academic” drawing—the long tussle with the unforgiving and the real motif which, in the end, proved to be the only basis on which the real formal achievements of modernism could be raised. Only in that way was the right radical distortion within a continuous tradition earned, and its results raised above the level of improvisory play ... The philosophical beauty of Mondrian’s squares and grids begins with the empirical beauty of his apple trees.

Cinema and television contain much great work that isn’t structurally orthodox (particularly in Europe), but even then its roots still lie firmly in, and are a reaction to, a universal archetype. As Hughes says, they are a conscious distortion of a continuing tradition. The masters did not abandon the basic tenets of composition; they merely subsumed them into art no longer bound by verisimilitude. All great artists—in music, drama, literature, in art itself—have an understanding of the rules whether that knowledge is conscious or not. “You need the eye, the hand, and the heart,” proclaims the ancient Chinese proverb. “Two won’t do.”

As Hughes says, they are a conscious distortion of a continuing tradition. The masters did not abandon the basic tenets of composition; they merely subsumed them into art no longer bound by verisimilitude. All great artists—in music, drama, literature, in art itself—have an understanding of the rules whether that knowledge is conscious or not. “You need the eye, the hand, and the heart,” proclaims the ancient Chinese proverb. “Two won’t do.”

Storytelling is an indispensable human preoccupation, as important to us all—almost—as breathing. From the mythical campfire tale to its explosion in the post-television age, it dominates our lives. It behooves us then to try and understand it. Delacroix countered the fear of knowledge succinctly: “First learn to be a craftsman; it won’t keep you from being a genius.” In stories throughout the ages there is one motif that continually recurs—the journey into the woods to find the dark but life-giving secret within.

This article has been adapted from John Yorke’s book, Into the Woods: A Five-Act Journey Into Story.

Related Video

A panel of storytellers share their favorite tales, from the Bible to Charlotte's Web.Every story is the same: The Hero's journey

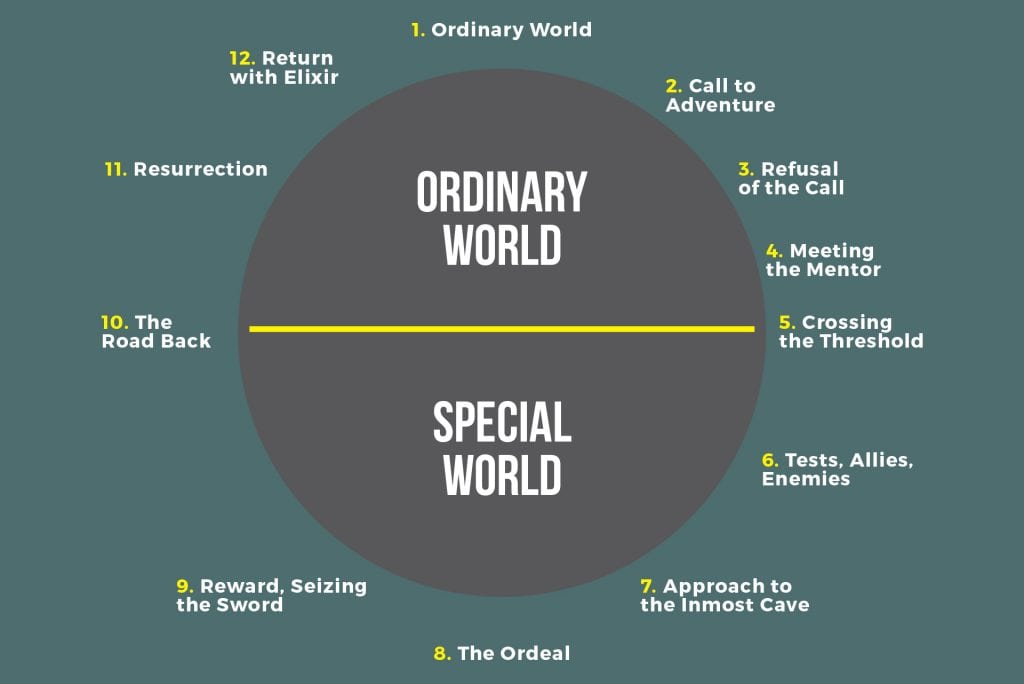

Skip to content Every story is the same: The Hero’s journeyWhat do Frodo Baggins, Luke Skywalker, Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz, Hansel & Gretel, and Hercules all have in common?

Their stories all follow a well-worn path, and in some cases are nearly identical.

In fact, once you know it, you will see this template for stories nearly everywhere.

And you might even be inspired to use it in your own creative work.

It is known as the Hero’s Journey.

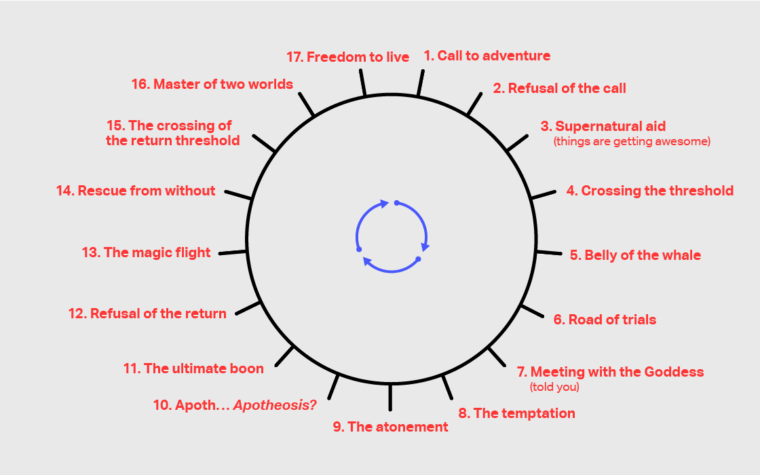

In 1949, author Joseph Campbell released a book called The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In it, he analysed hundreds of stories from cultures around the world.

In it, he analysed hundreds of stories from cultures around the world.

And he found that almost all of them shared a similar template, which dictated what the main character would go through during the story:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

It was so common in fact that he called it the monomyth, the single story.

While Campbell’s original summary had 1 stages the hero went through, the structure can be summarised as follows in 12 stages:

Status Quo: The hero is living their ordinary life in their ordinary world

- Call to adventure: Something invites the hero to leave the comfort of their life, but they might not be ready yet

- Assistance: The hero gets the help they need to take the step and leave their status quo, often from a more experienced or older figure

- Departure: The hero leaves their comfortable home and enters an unknown world

- Trials: The hero has to overcome challenges

- Approach: The hero is close to what they desire

- Crisis: There is a form of defeat preventing the hero getting what they want.

Sometimes, this can even be death (followed by rebirth), figuratively or literally

Sometimes, this can even be death (followed by rebirth), figuratively or literally - Treasure: The hero overcomes the previous obstacle and gets something valuable, either an object or knowledge

- Result: The hero has achieved what they set out to do.

- Return: The hero leaves the special world, and returns to the ordinary world a changed person

- New life: The hero notices something is different about their home or environment now that they are back. They adjust. Often, they share what they achieved and found.

- Resolution: The adventure is over. The hero settles back into their status quo, but is a different person they were previously.

Now, the idea of the monomyth should be taken with a grain of salt. It is a textbook example of biases, including selection bias and confirmation bias, where only the stories which fit the structure are used as examples.

There are many stories which do not fit the Hero’s Journey, such as the tragic heroes of Shakespeare who die at the end, thrillers, or jokes and comedic stories.

But it can be an excellent source of inspiration if you are having a hard time getting past the blank page.

And it is an interesting example of how creative ideas can be remixed over time and inspired by what came before.

So whether you decide to use your imagination to come up with a bedtime story for your child, or are writing the next blockbuster movie script or bestselling novel, take inspiration from the Hero’s Journey.

Idea to Value Podcast: Listen and Subscribe now

Listen and Subscribe to the Idea to Value Podcast. The best expert insights on Creativity and Innovation. If you like them, please leave us a review as well.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Stitcher

The following two tabs change content below.

- Bio

- Latest Posts

Creativity & Innovation expert: I help individuals and companies build their creativity and innovation capabilities, so you can develop the next breakthrough idea which customers love. Chief Editor of Ideatovalue.com and Founder / CEO of Improvides Innovation Consulting. Coach / Speaker / Author / TEDx Speaker / Voted as one of the most influential innovation bloggers.

Chief Editor of Ideatovalue.com and Founder / CEO of Improvides Innovation Consulting. Coach / Speaker / Author / TEDx Speaker / Voted as one of the most influential innovation bloggers.

- L.I.V.E. (Lean Innovation, Validation & Execution): A new, more effective way to manage multiple innovation projects - November 7, 2022

- “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” - October 30, 2022

- Opportunity cost - October 28, 2022

- The ladder of “No” - October 25, 2022

"People have become very fragile": how Lisa Taddeo wrote a book about real stories of violence

"Three women" is not a work of fiction, but a documentary study of three cases of violence. We spoke with the author of the book about how she collected material, why men perceive stories of violence differently, and what the #MeToo movement might come to women” by journalist and writer Lisa Taddeo. Critics called it "a gift to the women of the world who feel their desires are being ignored and their voices are not being heard. " For almost ten years, Taddeo spent with her heroines, talking, studying correspondence, court documents and articles from local newspapers. This book is an exploration of the thin line between dominance and violence, liberation and promiscuity, need and addiction, based on three real stories.

" For almost ten years, Taddeo spent with her heroines, talking, studying correspondence, court documents and articles from local newspapers. This book is an exploration of the thin line between dominance and violence, liberation and promiscuity, need and addiction, based on three real stories.

Maggie is from a dysfunctional family, 20 years old and a waitress at a roadside cafe. When a girl claims that in high school she was molested by a teacher, a school favorite and a father of many children, and sues, no one believes her. Thirty-year-old Lina is a housewife on maternity leave. She has two children, a beautiful home, a husband who fully provides for them and at the same time does not touch her for months. Desperate for intimacy, Lina starts a painful affair with a guy she dated at school. The third heroine, Sloane, is already forty, she and her husband have a profitable restaurant and an open relationship. There is a lot of sex in Sloan's life with different men and women on one condition: the husband must know about everything, and sometimes watch and participate.

- You could tell about the fate of your heroines in the form of a fiction novel. Why did you end up choosing the non-fiction genre?

— Precisely because the stories themselves — all three parts — are absolutely true. I didn't need to add elements of fiction, because these real stories of violence are so compelling in themselves that if I added fiction, it would make the whole book meaningless. All this was real. Yes, Lena and Sloan are unreal names of the heroines, but Maggie is the real name. And one of the reasons Maggie and I both wanted to use her real name is because that's how she was able to take back control of her story. I think it is impossible to add fiction to such serious real stories. You'll get a message like "Not everything in this book is true." My message is different - to write the whole truth. This will make it easier for people to sympathize with the heroines.

— It turns out that you worked on this book more like a journalist?

— I actually prefer to write fiction. My debut novel will be out in a couple of months. But "Three Women" demanded a completely different genre. It's like comparing painting and photography. You can love both, but they must be kept separate from each other.

My debut novel will be out in a couple of months. But "Three Women" demanded a completely different genre. It's like comparing painting and photography. You can love both, but they must be kept separate from each other.

— Do you remember the moment when you decided to write a book about your heroines, not an article?

- I came with this topic to one editor, and, to be honest, he asked if I would like to write a book about this. So I found myself in an interesting position, because at that time I thought that my first book would be a fiction novel. But since I was offered non-fiction, I had to write like this.

In general, the turning point was the meeting with Lina, a woman from Indiana. I saw that she was ready to tell me her story and be completely open and honest in every way. Before her, no one was ready to speak so frankly about the violence experienced. I never expected to find such a story.

- "Three Women" is true on the level of sensations. I think I will not be mistaken if I say that every woman in one form or another has faced harassment and violence. There are those whose experiences are very close to those of your heroines, but very few are willing to talk about it openly.

Yes. I looked for them all over America. I think this is because we are still surrounded by a rather toxic environment that appears around you when you suddenly start talking about violence. Of course, life has become better in some respects. For example, now we can directly tell men in what tone it is impossible to talk to us or that they have no right to judge. But the other side of this phenomenon has also appeared: women are afraid of how other women will react if they suddenly tell their story of violence.

— Do you mean the notorious “blame yourself”? Do you think the reaction of men is not as strong as the reaction of women?

— You know, I think the reactions to the book and the situation are just different. We, men and women, are very different, and this is part of the problem, because today we need everyone to be treated equally. A rather complicated and paradoxical situation is created.

We, men and women, are very different, and this is part of the problem, because today we need everyone to be treated equally. A rather complicated and paradoxical situation is created.

I think if we listened to each other more and did not behave in a judgmental and condescending manner when someone does decide to tell their story, then we as a society would have moved much further. It is worth not just recognizing that we are different, but listening more to what the other side feels and thinks.

— How did men and women react to your book? For example, recently published in Russia "My Dark Vanessa" , oddly enough, more excited men. At presentations, they are constantly trying to prove that the 42-year-old teacher is not too guilty, and Vanessa is not a victim. They could have said the same thing to Maggie from your book: "You wanted it too", "you yourself wrote letters to the teacher. "

"

- There's one thing I always say when it comes to Maggie's story. It's not just that the man was older. It's not about the age difference or even that he's married. He was her teacher, you know? A teacher is a person to whom we bring our children. And children spend about eight hours at school. And we as a society trust teachers. We expect them to help our children. In order for parents to psychologically send their children somewhere for such a long time, you need to be sure that the people you bring your child to are really good. That's the crux of Maggie's story. She was a child who liked the attention from the teacher. And the job of a teacher, as a person we trust, is to fulfill their pedagogical duties and not overstep the bounds. Therefore, I believe that Maggie is not to blame for the situation in any case. She was literally a child who needed a teacher, it was important for her, a high school student, to be his favorite.

It is very interesting for me to observe the difference between women's and men's understanding of the book. Although men accepted it, they have a different interpretation. One of the first men to read Three Women told me that he never knew how deeply indifference can hurt. And I was pleased that he understood the story of Lina, experienced such a reaction, extracted for himself precisely this thought.

Although men accepted it, they have a different interpretation. One of the first men to read Three Women told me that he never knew how deeply indifference can hurt. And I was pleased that he understood the story of Lina, experienced such a reaction, extracted for himself precisely this thought.

The Lolita of the #MeToo Era: How Kate Russell Wrote the Bestselling Teacher-Student Bond

— There is another argument that is often heard from women: “I don't want to stir up the past. I had true love and I don't want anyone like the #MeToo movement to explain to me that it was actually rape or coercion and I was the victim. Don't destroy my world!" What can you say to such a position?

- It is worth letting such girls continue to think like that. We must leave them alone and take their word for it, if they really think so.

Women should be allowed to tell their stories the way they want to.

I am convinced that it is the condemning attitude of society towards confessions of rape, harassment, condoning violence that makes people lie, hide, live with their burden for years. Maggie didn't enjoy sex with the teacher. The following happened to her: for a while she was fine that her teacher paid special attention to her, but in the end she realized that she was a victim in a relationship of notorious inequality. And she felt like a victim. There may indeed be people in the world who are in exactly the same position as Maggie and don't feel like victims. But does that soften the fact that the teacher committed the crime? No, it doesn't soften.

Bad "Teacher": what is "grooming" and why you can go to jail for it

these stories. After all, it was they who lived them, not you and me.

- "Three Women" is a complex story about the nature of sexual desire, which has many different shades. However, people want it to be simple: he is the rapist, she is the victim, black and white. You wanted to show a lot, especially in the Sloan story. Are you satisfied with the work done?

However, people want it to be simple: he is the rapist, she is the victim, black and white. You wanted to show a lot, especially in the Sloan story. Are you satisfied with the work done?

Yes. I think we are now living in an age of extremes. You are either on one side or the other. You either support the #MeToo movement or you are completely against it. You always have to choose a side. And if you don't shout hard enough in one direction about your agenda, people will start to think that you don't give a damn about the "right side". It seems to me that this creates a lot of problems. That's what I wanted to show with my book.

For example: “Yes, the teacher did just such an act. But now I will show you a few moments from his life. And what do we think of him now? I never label. As a human being, I have no right to pass judgment, I just wanted to tell you the stories of three women. My goal is to be as open-minded as possible, even in fiction. Our prejudices are how we perceive the world around us, it is something from ourselves. You don't need to involve other people in this.

Our prejudices are how we perceive the world around us, it is something from ourselves. You don't need to involve other people in this.

— The book doesn't really contain your judgments, you gave the three women their own voices — it's their book. How long have you been writing it?

— About eight years old. It was necessary to find women, live with them, write about them. And it was very hard. I didn’t have any money then, I had to somehow balance, take on various tasks for freelance, often travel back and forth across America. It was very hard and it took a long time.

— Are your heroines happy with what happened?

- I'll mostly talk about Maggie because she used her real name in the book, and because of that, I was primarily worried about her. One of her idols is Abby Wambach, a football player (forward of the US women's team. - Forbes Woman ). So, when Three Women just came out, Abby posted a photo on her Instagram where she was reading my book. I wrote to her: “You know, Maggie considers you her hero,” to which she publicly replied: “Maggie is my hero.”

- Forbes Woman ). So, when Three Women just came out, Abby posted a photo on her Instagram where she was reading my book. I wrote to her: “You know, Maggie considers you her hero,” to which she publicly replied: “Maggie is my hero.”

I am very glad that many people supported Maggie and believed in her story. I think we are still lucky with the #MeToo movement. At the very beginning of our joint work, I told her: “I believe that people will believe in your story. I want everyone, not just those living in your city, to believe you. And I can be wrong. And if I'm wrong, I don't even know what to do then. However, I am absolutely sure that you will be believed.” When it became clear that the book was accepted, it was for both of us the greatest joy. Maggie feels like she's been able to tell her story.

By the way, now we even have a series. Showtime is going to make a movie called Three Women based on the book, and Maggie has been brought in as a script consultant. So she's just fine. We communicate with Lina as friends, but we do not discuss the book. Sloan is also happy with everything. Of all the trio, she was the most worried about what would happen when the book came out. But nothing bad seems to have happened.

So she's just fine. We communicate with Lina as friends, but we do not discuss the book. Sloan is also happy with everything. Of all the trio, she was the most worried about what would happen when the book came out. But nothing bad seems to have happened.

— Were there moments when your heroines wanted to stop everything? This question is probably primarily about Sloan, because her story is the most controversial. The story of a successful business woman who has sex with different people to please her husband is too unusual - it's hard to imagine yourself in her place.

— It was difficult not only with her. After all, people talk only when they are in the mood, touch only on those topics that they want. It was really hard with Sloane. I always need to remember to keep her identity a secret. But in the end, we're not talking about me. This is her story. My job is to listen carefully to what she has to say. It was with Sloan that I acted most delicately, did not put pressure on her. In my opinion, Sloan's story was the least profound in the book because it gave me the least amount of information. Of all the women, she was the most reserved and cautious.

In my opinion, Sloan's story was the least profound in the book because it gave me the least amount of information. Of all the women, she was the most reserved and cautious.

I told all the characters, including Sloan, “This is your story. She is not mine. So if at some point you want to stop or not include some part of the story in the book, that's fine." And in working with Sloan, this happened quite often: we stopped if she didn’t want to discuss something. So I had to leave these "voids" of hers. If I approached this task as a journalist, I would call them exactly that - emptiness in a whole story. But I was not engaged in journalistic work, I wanted to tell her story the way she wanted it herself. When I am told that readers need to know everything down to the smallest detail, I say: “Oh, no. No need".

— What is Three Women about, from your point of view: about desire, about the life of a woman, about violence, about sex, or about something else?

— For me, this is a story about how much our childhood shapes us. And an important part of the book for me personally is the one that shows how much our mothers influence us. This is extremely interesting. I think that the book is largely devoted to the topic of motherhood.

And an important part of the book for me personally is the one that shows how much our mothers influence us. This is extremely interesting. I think that the book is largely devoted to the topic of motherhood.

One hundred years ago such a book could not have appeared, and neither could the #MeToo movement. And not only because of the lack of social networks or freedom of speech, but because of the lack of desire to talk publicly about passion, violence, their perception. Today, society allows different formats of discussion on this topic. But we are not talking, for example, about violence among men, this is an even more taboo topic.

- Do you think #MeToo will move in this direction?

— I think we should listen more to others and be honest about our stories. You should not act according to the “punish everyone around” model. It seems to me that the culture of prohibition, rejection and the desire to immediately punish people do not allow us to develop and learn more about each other. It feels like everyone has taken out their own scales of justice and is following the “guilty until proven otherwise” rule. I think that in communication one should also follow the presumption of innocence.

It feels like everyone has taken out their own scales of justice and is following the “guilty until proven otherwise” rule. I think that in communication one should also follow the presumption of innocence.

- On social media, many difficult issues are discussed more openly than before, but at the same time, tough verdicts are issued too quickly. We see how it works. One scandalous post - and now the already famous actor loses everything, everyone turns away from him. How can we make this process more measured?

- I don't know. Maybe put a 20 minute wait before posting a comment on twitter? But I also think about it. It happens that right now there is an impulse to do something drastic. At such moments, it is very useful that someone can stop you, distract you from this undertaking. I often think about whatever things I did in my life back then. It seems to me that there is nothing better in the world than time. Time heals best, even from a biological point of view.

Time heals best, even from a biological point of view.

Every story is equally important. Each of us has a right to a word.

I think we should try to take one day to think before "hitting someone" in earnest. And in a verbal conflict it is always useful to take a break, even if only for a minute. To reflect and really consider the point of view that you have heard from the other side. I find this an interesting and useful exercise.

- The media tends to cover only stories associated with big names: rock stars, movie actors, billionaires, and so on. But after all, there are thousands of stories of ordinary women in the world that are not interesting to the police and the law and are not discussed in society.

— Yes, I am outraged, because every story is equally important. Each of us has the right to speak. I believe that now we all live in a society where there is a kind of caste system. Although in general, despite the fact that there are such things as money or power, a person should be equal to the rest. It's elementary biology! I think if we tell more stories of ordinary people and think about them, then we will come to the right place.

Although in general, despite the fact that there are such things as money or power, a person should be equal to the rest. It's elementary biology! I think if we tell more stories of ordinary people and think about them, then we will come to the right place.

- Do you think it was right for Maggie to come out and say, “Yes, I'm Maggie. Here's my story." Maybe she should have turned not to you, but, for example, to go to therapy. Is honest public discussion helpful?

— Yes, I think an honest public discussion is helpful. Thousands of women have written to Maggie and me since the book's release, saying that her story helped them deal with their situation. Maggie received letters from all over the world, such as Nigeria. I think it's very cool. In addition, you don’t suffer so much when you realize that someone else has already been in such a situation and was able to survive it.

- While you were looking for your heroines, you probably heard a lot of stories on the topic and met many women. Should we wait for a new novel - or is the topic closed for you?

Should we wait for a new novel - or is the topic closed for you?

— My next book will be out in June, called Animal. It is dedicated to the theme of female rage. When I was looking for material for Three Women, I heard a lot of stories about it. Many things were not included in the first book and then turned into fiction. I don’t know yet what I will write about in the future, but I have always been interested in everything related to women and their feelings.

— What current topics do you think should be raised in the literature now?

- Grief, mental illness and increased anxiety. I believe there is a stigmatization in the world against mental illness, anxiety, depression - all its forms. This is another area where people need to listen to other people's stories and feelings.

When it comes to extremely sensitive people, it is very difficult to achieve balance. People have become very fragile. Let's say my new book is about very hard things, like rape or miscarriage. And now, when my book is mentioned somewhere online, young readers are specifically warned about the triggers. It is very interesting.

People have become very fragile. Let's say my new book is about very hard things, like rape or miscarriage. And now, when my book is mentioned somewhere online, young readers are specifically warned about the triggers. It is very interesting.

I understand perfectly well what triggers are, and I myself have experienced this state many times, when literally one detail makes you flare up, I am aware of it all. But at the same time, I believe that one should not suppress freedom of speech and hush up problems just because the mention of them hurts.

I think the best way to deal with this situation is to educate in our children the sensitivity and understanding that their needs and desires are important, but at the same time, we should not expect the whole world to know about these needs and desires. They need to be able to defend their position and understand that in certain situations they know more than someone else - this other person will come to understand in some other way, it's just not his time yet. We should listen more and talk less - this is very helpful.

We should listen more and talk less - this is very helpful.

— Your daughter is six years old, so you became a mother when you were already writing Three Women. Did it affect the book in any way?

Yes, absolutely. The very meaning of the book has not changed, because by the time the child was born, I had already found and worked through most of the characters in the book. So the people themselves have not changed and what I was going to write about them has not changed. However, because of my daughter, I began to ask people different questions, and thanks to her, I focused the prologue and epilogue of the book on my mother. This happened because after the birth of the child, I had all these questions, the answers to which I could not get. For example, I thought, “How much do I need to tell my daughter about my life?” - and so on. So yes, she changed my job. I don't know what it would have looked like if it wasn't for my daughter, but the book would have been different for sure.

Read on long May days: the continuation of Glukhovsky's "Lent", the history of Elizabeth II's dress and 8 more literary novelties of spring

10 photos

every story unscathed - Translation into Russian - examples English

English

Arabic German English Spanish French Hebrew Italian Japanese Dutch Polish Portuguese Romanian Russian Swedish Turkish Ukrainian Chinese

Russian

Synonyms Arabic German English Spanish French Hebrew Italian Japanese Dutch Polish Portuguese Romanian Russian Swedish Turkish Ukrainian Chinese Ukrainian

These examples may contain rude words based on your search.

These examples may contain colloquial words based on your search.

In fact, the only one who escapes every story unscathed is the Jack.

In fact, the only one that leaves unscathed in of all stories is Jack.

Other results

Every story was different, and every story was equally sad.

All have different stories, but all are equally sad.

Every story is different and yet the same.

Each collection is different and yet the same.

Every story he told us hid a message.

Every story that he told us had a hidden meaning.

Every story in this book actually happened.

Everything that is written here actually happened.

Almost every story recalled a memory from my own life.

Small this story brought back memories of an incident from my own life.

Every story is a treasure, she said.

" Every book was a treasure," she said.

Every story can be produced beautiful.

I think that any story can be done beautifully.

Every story needs someone to tell it.

Every story wants someone to know about.

Every story I read is Google vs someone else.

Every story I read about Google is about our struggle with other companies.

Every story can teach you SOMETHING.

Besides, each story of can teach you something.

Every story I told was about me.

Everything that you described was about me.

Every story is a world I know.

Every novel is a world that I create.

He destroys every story he enters.

He passes through himself all the stories is filming.

Every story has something out of my own experience.

“In , every story should have something related to my own experience.

He elevates every story he draws.

He passes through himself all the stories is filming.

But almost every story is good.

But at the same time, each story is good.

Not every story was completed or published.

True, not all the works of were completed or published by him ...

You know every story moment and every line.

A movie where you know every moment and every phrase.

Every story of success has a beginning.

We know that every success story has its beginning.

Possibly inappropriate content

Examples are used only to help you translate the word or expression searched in various contexts.