Free insect stories

Insects - Free Kids Books

Search:

Sort by: Popular Date

A little bee has lost his home and asks an elephant to help him find it. Sample Text from The Bee and the Elephant “I am lost,” said Little Bee. “I cannot find my home!” “Can you please help me, Mr. Elephant?” “Is this nest your home, Little Bee?” the elephant asked. “Oh no!” cried …

Reviews (2)

Druvi needs an umbrella to protect her wings from the rain. Join the dragonfly as she searches for the perfect leaf-umbrella. Sample Text from An Umbrella for Druvi Druvi the dragonfly has just learnt to fly. She flies near the pond with her friends. They tease the frogs and eat mosquitoes for lunch. In the …

Reviews (1)

In The Best Foot Forward the centipede gets confused over a simple task, yet is able to carry it out with ease when under stress. Have you ever got confused over a simple task? There is a reason why Centipede gets confused.

Author: Rustom Dadachanji, Illustrator: Tanvi Bhat Sample Text from The Best Foor Forward …

Reviews

A Butterfly Smile – A Colourful Butterfly Biology Picturebook for young zoologist. This story is about the life cycle of butterflies. starting butterflies laying their eggs turning into cocoons and emerging into colourful butterflies. Author: Mathangi Subramanian Illustrator: Lavanya Naidu Follow along the story where Kavya a shy girl who just moved to Bengaluru to …

Reviews (5)

Busy Ants – In this story we follow the ants as they show us what magnificent little creature they are. This book will keep your young readers entertained as they learn all about how busy the ants are and what they do, and more and us have in common. This book is one of the …

Reviews

In Shongololo’s Shoes, Shongololo’s lost his shoes and everyone tells him they haven’t seen them, but can you find Shongololo’s shoes on the pages of this cute book? And what does the lion want with all the shoes, find out more by reading this free picture book. This is a short picture book from BookDash …

This is a short picture book from BookDash …

Reviews (4)

One, Three, Five, HELP is a maths story that includes adding exercises and a lesson about odd and even numbers. See more books like this in our Maths category. See more books from the creators in our Pratham-Storyweaver category. Author: Kuzhali Manickavel Illustrator: Sonal Gupta Vaswani Text and Images from One, Three, Five, HELP …

Reviews (2)

In The Kung-Fu Grasshoppers, the grasshopper’s children are taken prisoner by a hungry monster. Two strangers arrive in the grasshopper village, an old man and his granddaughter. Who are they, and can they help to save the grasshopper children from the evil monster who holds them prisoner in the nearby woods? This suspense-filled tale of …

Reviews (1)

Wiggle-Jiggle is a cute and cuddly caterpillar story with very cute rhythm, rhyme, and repetition. Young children will love this short, beautifully illustrated picturebook. Young children will love all the fun sound words along with the bright pictures, and the inevitable ending. Illustrated by: Megan Vermaak Written by: Mathapelo Mabaso Designed by: Chenél Ferreira Edited …

Young children will love all the fun sound words along with the bright pictures, and the inevitable ending. Illustrated by: Megan Vermaak Written by: Mathapelo Mabaso Designed by: Chenél Ferreira Edited …

Reviews (5)

In Off to See Spiders, we have a fun biology lesson about all the different types of spiders. Shama takes her two younger friends Kaveri and Shivi on a spider hunt. They find lots of different types of spiders, and Shama helps them learn about all the different names. The book combines some fun rhythm and …

Reviews (2)

🕷🐞 🦋 FREE Insects for Preschoolers Printable Book

Alphabet | Alphabet Activities | Bug | Printables | Science | Science Printables

ByBeth Gorden

Young children will have fun learning about a variety of creepy crawly insects with this super cute, insect activities that usese an alphabet printable

to make a bug reader. Use bingo daubers then color and read your own My Books of Insects Dot Reader to learn about 24 different common insects for preschoolers, toddlers, and kindergartners. Simply print free insects printables and you are ready to learn about lots of different bugs while making lowercase letters with do a dot printables.

Use bingo daubers then color and read your own My Books of Insects Dot Reader to learn about 24 different common insects for preschoolers, toddlers, and kindergartners. Simply print free insects printables and you are ready to learn about lots of different bugs while making lowercase letters with do a dot printables.

Insects for Preschoolers

Are your children fascinated by bugs? Most children love to look for bugs and watch them slither or fly. They are fascinated by how detailed and unique they are despite their small size. Toddler, preschool, pre-k, and kindergarten age students will learn about 24 different insects for preschoolers in this free insects printable. Simply grab your bingo markers to complete the pages in your do a dot printables pack, colour the pages, assemble, and you are ready to read and learn about insects with your child.

Whether you are a parent, teacher, or homeschooler – you will love these low prep insect reader for helping students work on fine motor skills. This free insect reader is perfect for use in literacy and science centers, for extra practice, at school or at home, summer learning or as part of an insect study. With this pack, children will learn about twenty-four different insects.

This free insect reader is perfect for use in literacy and science centers, for extra practice, at school or at home, summer learning or as part of an insect study. With this pack, children will learn about twenty-four different insects.

Free Insects Printables

Start by scrolling to the bottom of the post, under the terms of use, and click on the text link that says >> _____ <<. The pdf file will open in a new window for you to save the freebie and print the template.

Insects printable

Print off all the pages. As there are two pages of the reader on each letter size sheet, you will need to cut out the reader book and staple together. This reader could also be held together by placing a binder ring in the top left hand corner. This method may prove easier for children to complete each page.

Insect printables for preschoolers

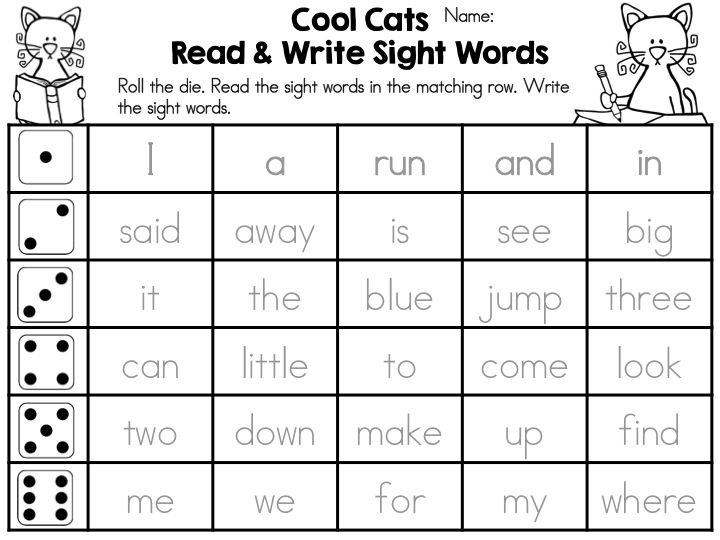

Each page of this insects for kids book contains three activities.

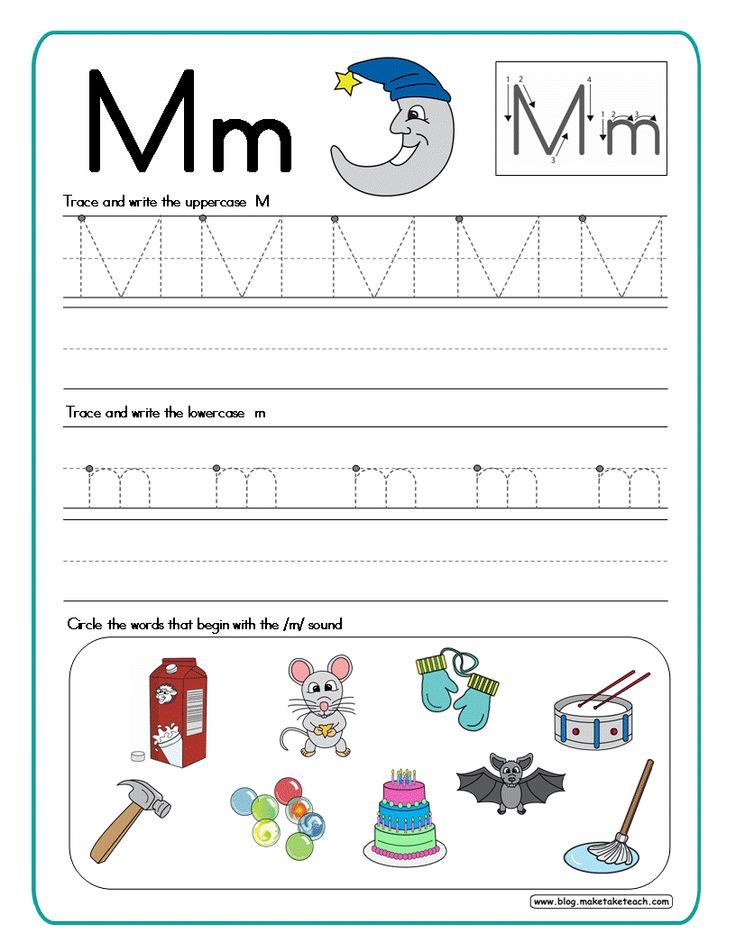

- The first activity includes learning to read and write the name of the insect.

- The second activity is to dot the letter that the name the insect starts with. This can be done with a bingo maker, do a dot marker, with a q-tip and paint or with their finger and finger-paints. They could also color in the dots or place circle stickers on them if they wish. This is a great way to sneak in some alphabet recognition into your day.

- The third activity involves coloring and decorating the insect with crayons, markers, or colored pencils.

Free printable bug books

This printable pack comes completely in black and white to save on printing ink costs.

free printable bug books

- Alphabet Find a Letter Do a Dot Printables

- Endangered Animals Find the Letter Worksheets

- Snow Globe Find the Letter Do a Dot Printables

- Find the Letter Dinosaur Alphabet Fun

- Letter Recognition Do a Dot Printables

- Shape Do a Dot Printables

- Birds for Preschoolers Printable Book

- Addition Tic-Tac-Toe Do a Dot Printables

- Alphabet Dot Book

- Making 10 Practice with Ten Frames Do a Dot Printables

- Phonics Beginning Sound Do a Dot Printables

- Turkey Color Matching Do a Dot Printables

**See more FREE Do a Dot Printables for kids!

Insect Worksheets for Preschool

If are looking for more bug activities for preschoolers, toddlers, and kindergartners – including lots of free insect printables, you will love these FREE resources:

- Peek-a-Bug Insect Alphabet Printable – four abc games to help kids learn their ABCs, match upper and lowercase letters, and more!

- Ladybug Ladybug Activities for Preschoolers activity for pre-k and kindergarten

- Bug Free printable sight word games is a simple-to-play way to practice sight words with preschool, kindergarten, and first grade students

- I is for Inchworm insect activities including a worm observation book

- Stamped Potato Bee Craft for spring

- Cute Spider Name Craft

- Firefly Preschool Counting Worksheets

- Gummy Worm Edible Slime

- Fun, hands-on Spiders Activities for Preschoolers Activities

- Quick-and-Easy Spider Slime

- All About Earthworm Life Cycle Worksheets

- Insect Printables for Preschoolers 1-10 Coloring Book for preschoolers

- Ladybug Life Cycle Worksheet Pages

- Bug color by blend worksheet – Coloring by Blends

- Free printable Life Cycle of a Spider for Kids worksheets

- Ladybug Life cycle for Kids worksheets

- Life Cycle of a Mosquito Printables

- Free Bee Counting Game

- Lots of fun, hands-on learning ideas in this Free Insect Activities for Preschoolers

- Bee and Insect Theme Preschool

- SUPER cute Spider math activities for preschoolers with Playdough Mats

- Fun, Insect Telling Time Puzzles

- Catch 20 Bug Counting Activity for Pre-k and Kindergarten

- Ladybug Addition Math Game for Kindergartners and Grade 1 students

- Bug free printable sight word books pdf – children will cut and paste sentences, color the insect coloring pages, and practice reading sight words

Insect Printables

- Free Printable, Simple Bug Coloring Pages for kids

- Shape Spider Worksheets Preschool and Kindergarten

- Insect Worksheets to learn about lots of different bugs in our world

- Practice Letters A-Z with these Free Insect Printables

- Learn all about ants with these creative ant activities for preschoolers

- Bug Math Worksheets for pre-k and kindergarten students

- Cute Bug Counting Bugs Worksheet

- Measuring Lines of Bugs Preschool Measurement Worksheets

- Count and Clip Bugs Counting to 30 Worksheets

- Buzzing Bees Numbers 1-12 Worksheets

- I Spy Printables pdf – bug activity sheets

- Bee CVC Words Activity for Kids

- Bug Themed Find the letter worksheets pdf

- FUN Backyard Critter Bug Worksheets for Kindergarten

- Ladybug Counting Mats

- Silly Worm Count to 10 Sticker Worksheets

- Free Printable Insect Mini Book to learn about bug life cycles

- Hands-on Spider Shape Activities for Preschoolers

- Free, Educational Insect Coloring Pages pdf for kids

- Help children work on spelling their name with these insect free printable name recognition activities

- Plus don’t miss these fun-to-read bug books for preschool

Alphabet Printables for Preschoolers

- Handy, Free Alphabet Chart

- Cute Alphabet Coloring Pages helps build vocabulary and work on beginning sounds and phonemic awareness

- Alphabet Dot Marker Printables

- Find the Letter Dinosaur Alphabet Printables

- Fruit Loop or Skittle Alphabet Mat

- Alphabet Construction Activities for Preschoolers

- Bug Find the Letter Worksheets pdf

- Tracing Alphabet Popsicles Summer Activity for Preschoolers

- Watermelon Seed Alphabet Mats Summer Activity for Preschoolers

ABC Preschool

- Apple is for Apple Printable teaching beginning sounds from A to Z

- Flower Begining Sound Activity

- Traceable Alphabet Preschool Apple Activity

- Letter Crafts – we have a free printable letter craft for every letter of the alphabet A to Z

- Letter Recognition Worksheets – find and dab the upper and lowercase letters in these super cute ABC printables!

- Endangered Animals Find the Letter Worksheets

- Simple preschool alphabet worksheets to color and trace letters

- How cute are these letter find pumpkin worksheets for preschool

- Practice uppercase letter tracing with these super cute animal alphabet cards A-Z

- Animal Alphabet Worksheets – dab the letter and trace the uppercase and lower case letters

- Printable Letter Mazes

- See all of our FREE ABC Printables here!

Plus don’t miss our MANY preschool worksheets, fun alphabet printables, hands-on preschool math, clever ideas to learn colors, complete preschool themes, lots of playdoh mats, cute preschool crafts, and fantastic preschool books on our Preschool Play and Learn website.

Insects for preschoolers

By using resources from my site you agree to the following:

- This is for personal and personal classroom use only (to share please direct others to this post to grab their own set!)

- This may NOT be sold, hosted, reproduced, or stored on any other site (including blog, Facebook, Dropbox, etc.)

- All materials provided are copyright protected. Please see Terms of Use.

- Graphics Purchased and used with permission

- I offer free printables to bless my readers AND to provide for my family. Your frequent visits to my blog & support purchasing through affiliates links and ads keep the lights on so to speak. Thanks you!

>> My Insect Book <<

Beth Gorden

Beth Gorden is the creative multi-tasking creator of Preschool Play and Learn. As a busy homeschooling mother of six, she strives to create hands-on learning activities and worksheets that kids will love to make learning FUN! Beth is also the creator of 123Homeschool4Me. com and kindergartenworksheetsandgames.com where she shares more than 100,000 pages of FREE worksheets,& educational ideas for PreK-8th grade.

com and kindergartenworksheetsandgames.com where she shares more than 100,000 pages of FREE worksheets,& educational ideas for PreK-8th grade.

Similar Posts

Read online A Brief History of Insects. Six-legged masters of the planet”, Alexander Khramov – LitRes

Scientific editor Vladimir Kartsev, Ph.D. biol. Sciences

Editor Anna Shchelkunova

Publisher P. Podkosov

Project manager A. Shuvalova

Assistant of the editorial office M. Korochenskaya

Reserves layout A. Larionov

Art design and layout Yu. Buga

© Khramov A., 2022

© Alpina non-fiction LLC, 2022

900 This e-book is intended solely for private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes. The e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, including text, images and others, may not be copied or used in any other way without the permission of the copyright holder. In particular, such use is prohibited, as a result of which an electronic book, its part, fragment or element becomes available to a limited or indefinite circle of persons, including via the Internet, regardless of whether access is provided for a fee or free of charge.

Copying, reproduction and other use of an e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, beyond private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes, without the consent of the copyright holder is illegal and entails criminal, administrative and civil liability.

* * *

Alexander Georgievich Ponomarenko and Alexander Pavlovich Rasnitsyn, Patriarchs of Russian paleoentomology, this book is dedicated

The publication was prepared in partnership with the Trajectory Foundation for Non-Commercial Initiatives (with the financial support of N.V. Katorzhnov).

The Trajectory Foundation for Support of Scientific, Educational and Cultural Initiatives (www.traektoriafdn.ru) was established in 2015. The Foundation's programs are aimed at stimulating interest in science and scientific research, implementing educational programs, increasing the intellectual level and creative potential of young people, increasing the competitiveness of domestic science and education, popularizing science and culture, and promoting ideas of preserving cultural heritage. The Foundation organizes educational and popular science events throughout Russia, promotes the creation of successful practices of interaction within the educational and scientific community.

The Foundation organizes educational and popular science events throughout Russia, promotes the creation of successful practices of interaction within the educational and scientific community.

As part of the publishing project, the Trajectory Foundation supports the publication of the best examples of Russian and foreign popular science literature.

Foreword

Any history, including the history of the development of life on Earth, is an intricate interweaving of causes and effects. Remove one thing, and everything else will change beyond recognition. In Ray Bradbury's famous sci-fi short story "Thunder Came," a time traveler accidentally crushed a butterfly in the distant past, and upon returning to the present, was horrified to find that in his country, an authoritarian candidate won the election instead of a liberal. And what if not a single butterfly, but all insects, disappeared from the evolutionary panorama of past epochs? Vertebrates would never come to land, because in the absence of insects they would have nothing to eat there. Gymnosperms would be left without cones, because they would not have to cover the seeds with scales to protect against insects. And for whom would flowers bloom then?.. But even if, as a thought experiment, we remove only the most unpretentious or annoying insects from the past, the consequences will still surprise us. If there were no lice, a person would remain hairy, like a chimpanzee. If there were no tsetse flies, the stripes on the zebra would disappear ...

Gymnosperms would be left without cones, because they would not have to cover the seeds with scales to protect against insects. And for whom would flowers bloom then?.. But even if, as a thought experiment, we remove only the most unpretentious or annoying insects from the past, the consequences will still surprise us. If there were no lice, a person would remain hairy, like a chimpanzee. If there were no tsetse flies, the stripes on the zebra would disappear ...

Insects have existed on our planet for more than 400 million years. They were among the first animals to explore the land. Insects had a chance to become eyewitnesses of global cataclysms, to observe the rise and fall of entire groups of plants and vertebrates. Seed ferns, Permian animal lizards, dinosaurs appeared and disappeared before their compound eyes. Insects are the guiding thread that I will try to grasp in this book through the intricate labyrinth of past eras, ending with the appearance of our own species. After all, the general, as you know, is best known through the particular. The fate of one family can sometimes say more about a historical epoch than several volumes of statistical calculations and military chronicles. In the same way, following the evolutionary fate of insects, we will inevitably plunge into those epochal events in which they were involved not only as extras, but often as the main characters. Plus, it's always good to look at things from a different angle. Discussing evolution not from a bird's eye view, but from the position of six-legged goats swarming under our feet, we will discover more and more new sides in it.

The fate of one family can sometimes say more about a historical epoch than several volumes of statistical calculations and military chronicles. In the same way, following the evolutionary fate of insects, we will inevitably plunge into those epochal events in which they were involved not only as extras, but often as the main characters. Plus, it's always good to look at things from a different angle. Discussing evolution not from a bird's eye view, but from the position of six-legged goats swarming under our feet, we will discover more and more new sides in it.

Don't think I'm making excuses for devoting an entire book to such a trifle as insects. They do not need laudatory odes. Insects are the most diverse group of living creatures on Earth, and for this fact alone, they deserve no less attention than birds, cats, and all other four-legged animals put together. However, it cannot be said that they do not write about insects and do not remember. On the contrary, every year there is a mass of beautifully illustrated popular books about butterflies, beetles and their relatives. But for the most part, these books are just a collection of entertaining facts: the largest species, the most beautiful, the most harmful are listed ... As a rule, not a word is said about the formation and historical development of various groups of insects. To fill this gap, I decided to write the book you are holding in your hands. In it, I tried to build my story so that the forest was visible behind the trees. I have tried to present insects as a whole in their relationship with the rest of nature, to outline the general patterns and specific circumstances of the past, thanks to which these six-legged creatures have become what we see them today.

But for the most part, these books are just a collection of entertaining facts: the largest species, the most beautiful, the most harmful are listed ... As a rule, not a word is said about the formation and historical development of various groups of insects. To fill this gap, I decided to write the book you are holding in your hands. In it, I tried to build my story so that the forest was visible behind the trees. I have tried to present insects as a whole in their relationship with the rest of nature, to outline the general patterns and specific circumstances of the past, thanks to which these six-legged creatures have become what we see them today.

There are many ways to study the past. For example, you can compare the genes of living species and then drive the found similarities and differences into a special computer program. This program will calculate the most likely scenario for the origin of the groups of interest to us and the time when they budded from each other. The resulting result will be presented in the form of a genealogical chart, similar to a large branched tree. It looks very scientific: solid mathematics and cold objectivity. Yes, that's the trouble - you just need to take other genes for comparison and apply a slightly different mathematical algorithm for data processing, as the "tree" will turn out to be completely different. And what is there to believe? The same discrepancies arise if, instead of DNA sequences, scientists use various morphological features of modern insects to build genealogical schemes: the shape of the paw, the arrangement of bristles, the structure of the genitals. As a result, each researcher has his own opinion about the order in which some insects descended from others and what their last common ancestor looked like. However, things are even worse: sometimes in the works of the same authors, published in different years, one can find mutually exclusive genealogical schemes.

It looks very scientific: solid mathematics and cold objectivity. Yes, that's the trouble - you just need to take other genes for comparison and apply a slightly different mathematical algorithm for data processing, as the "tree" will turn out to be completely different. And what is there to believe? The same discrepancies arise if, instead of DNA sequences, scientists use various morphological features of modern insects to build genealogical schemes: the shape of the paw, the arrangement of bristles, the structure of the genitals. As a result, each researcher has his own opinion about the order in which some insects descended from others and what their last common ancestor looked like. However, things are even worse: sometimes in the works of the same authors, published in different years, one can find mutually exclusive genealogical schemes.

Fortunately, we have a science at our disposal that allows us to touch the past directly - paleontology. Everyone knows about dinosaurs and mammoths, the remains of which paleontologists dig out of the ground. However, few people realize that there is a whole branch of paleontology devoted to the study of fossil insects. It's called paleoentomology, and the people who work in this field are called paleoentomologists. Paleoentomology has a long history. The first scientific descriptions of fossil insects were published as early as the 19th century, but then only a few enthusiasts were engaged in this. They had to process large collections alone and navigate different groups of insects. But given how diverse insects are, this was an almost impossible task. An entomologist who devotes himself to modern beetles will be an amateur in flies, and what can we say about fossil specimens in which signs are much less visible. And so it turned out that the first paleoentomologists mistook the wings of extinct cicadas for butterfly wings, and the ancient lacewings were passed off as termites ...

However, few people realize that there is a whole branch of paleontology devoted to the study of fossil insects. It's called paleoentomology, and the people who work in this field are called paleoentomologists. Paleoentomology has a long history. The first scientific descriptions of fossil insects were published as early as the 19th century, but then only a few enthusiasts were engaged in this. They had to process large collections alone and navigate different groups of insects. But given how diverse insects are, this was an almost impossible task. An entomologist who devotes himself to modern beetles will be an amateur in flies, and what can we say about fossil specimens in which signs are much less visible. And so it turned out that the first paleoentomologists mistook the wings of extinct cicadas for butterfly wings, and the ancient lacewings were passed off as termites ...

Everything changed thanks to the Russian entomologist Andrei Martynov (1879–1938), who shortly before his death founded the world's first laboratory dedicated to the study of fossil insects at the Paleontological Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences. Martynov decided to assemble in one team specialists in different orders of insects who would work together, but each within their own competence. When a dragonfly expert sits in the office opposite, and a dipteran specialist through the door, you can no longer waste your time sorting out these groups yourself. Martynov as the head of the laboratory - it became known as the Laboratory of Arthropods - was replaced by his student, entomologist Boris Rodendorf. Under his leadership, the Soviet school of paleoentomology has taken a leading position in the world. At that time, many foreign scientists who worked with fossil insects were learning Russian, because it was believed that it was impossible to practice paleoentomology without knowledge of it. Each collection of laboratory works published in Russian was immediately overgrown with official and self-made translations. Along with space and ballet, the championship in the study of fossil insects could rightfully be the pride of the USSR.

Martynov decided to assemble in one team specialists in different orders of insects who would work together, but each within their own competence. When a dragonfly expert sits in the office opposite, and a dipteran specialist through the door, you can no longer waste your time sorting out these groups yourself. Martynov as the head of the laboratory - it became known as the Laboratory of Arthropods - was replaced by his student, entomologist Boris Rodendorf. Under his leadership, the Soviet school of paleoentomology has taken a leading position in the world. At that time, many foreign scientists who worked with fossil insects were learning Russian, because it was believed that it was impossible to practice paleoentomology without knowledge of it. Each collection of laboratory works published in Russian was immediately overgrown with official and self-made translations. Along with space and ballet, the championship in the study of fossil insects could rightfully be the pride of the USSR.

A lot has changed since then. China, the USA, France, Poland and other countries have their own scientific centers where they study ancient insects. Paleoentomology has become international and English-speaking. The International Paleoentomological Society emerged with its own journals and conferences. I remember how the then Lebanese President Michel Suleiman even met with us, the participants of one of these conferences, held in Lebanon in 2013. Like all official receptions, this event was rather boring: our buses dragged for a long time to the presidential palace through a string of checkpoints, and then in the palace itself we were lined up just as long for a joint photo. And yet, the very fact that the few paleoentomologists who ventured into a not-so-safe Middle Eastern country took two tour buses with them is already saying something. Paleoentomology is now a booming field of knowledge [1] . More than 400 articles are published annually on this topic, leading scientific journals sometimes provide entire spreads to highlight sensational findings that shed light on the evolution of insects. Progress in the field of paleoentomology is so rapid that it can be difficult to keep up with it. I have been writing this book for almost five years, and during this time I have repeatedly had to make corrections and additions to it after the release of new works.

Progress in the field of paleoentomology is so rapid that it can be difficult to keep up with it. I have been writing this book for almost five years, and during this time I have repeatedly had to make corrections and additions to it after the release of new works.

Before I begin my story, I must warn the reader. The sequence of fossils found in terrestrial rocks is called the fossil record for a reason. The chronicle is a text, and the humanities such as hermeneutics and exegesis deal with the interpretation of texts. How can the meaning of his teaching be restored from the few surviving sayings of Heraclitus? What did the Old Testament writer mean? Paleontologists face similar challenges. Paleontology is a kind of hermeneutics that skillfully disguises itself as a natural science discipline. It is very much built on interpretations. We cannot go back in time and check how things really were. In our hands are only scattered pieces of the puzzle, and we are forced to think out the rest. As my supervisor Alexander Georgievich Ponomarenko, an outstanding specialist in fossil beetles, used to say, a paleontologist must have a good imagination. Therefore, much of what is discussed in this book is just plausible scenarios and rough reconstructions based on a number of assumptions and extrapolations. But it cannot be otherwise. Uncertainty awaits us not only in the future, but also in the past. This is what is called life. Let's plunge into its whirlpool together with insects!

As my supervisor Alexander Georgievich Ponomarenko, an outstanding specialist in fossil beetles, used to say, a paleontologist must have a good imagination. Therefore, much of what is discussed in this book is just plausible scenarios and rough reconstructions based on a number of assumptions and extrapolations. But it cannot be otherwise. Uncertainty awaits us not only in the future, but also in the past. This is what is called life. Let's plunge into its whirlpool together with insects!

This book, in a revised form, includes several articles and notes by the author, published in the journal Science and Life, on the Elements portal and in the Troitsky Variant newspaper. I am sincerely grateful to these publications for the opportunity to immediately share extracts of the manuscript with readers - it is much easier than writing to the table. I also want to thank all my colleagues, both domestic and foreign, for the provided illustrations and valuable advice, which were very useful when working on the text.

Part I

How it all began

Chapter 1

Stones and amber

In the early morning of July 4, 1810, the people of Amsterdam woke up to the sound of soldiers' boots and the neighing of horses - the advance units of the Napoleonic army were entering the city. The reason for the annexation of the puppet Kingdom of Holland was the incessant flow of English smuggling through its territory, which threatened the policy of the Continental blockade. For three whole years, Holland became part of the French Empire - after the troops, numerous French officials poured into it, who had to bring local orders into line with the general imperial ones. Among these obscure customs officers, censors and prosecutors was a man whose name has entered the annals of science forever - the French paleontologist Georges Cuvier. Napoleon included him in the commission, which was entrusted with the inspection of university education in the annexed territories. And so Cuvier ended up in Harlem on the doorstep of the Taylor Museum, where a very remarkable fossil was kept - the alleged skeleton of an antediluvian man, discovered by the Swiss naturalist Johann Scheuchzer.

A half-meter skeleton with a partially preserved spine and a skull of a strange round shape was found by Scheuchzer in the 1720s. near the town of Ehningen in southern Germany. Now we know that layers rich in Miocene fossils come to the surface in this place. But at the time of Scheuchzer, ideas about the geological age of the Earth were still the most vague. Therefore, he mistook the mysterious skeleton for the remains of a child who died during the Flood, and even gave it the specific name Homo diluvii testis , which in Latin means "a man is a witness to the flood." The Taylor Museum in Holland purchased the find from Scheuchzer's grandson. The fossil became the pearl of the museum collection, it was cherished like the apple of an eye. But the museum, of course, did not dare to refuse Napoleon's confidant: Cuvier temporarily got the skeleton into his own hands and cleaned it of the rock, which hid some details. Limb bones came to the surface, arranged like those of amphibians and had nothing to do with humans. Cuvier's verdict was unequivocal: Scheuchzer found not a flood victim, but the skeleton of a giant salamander.

Cuvier's verdict was unequivocal: Scheuchzer found not a flood victim, but the skeleton of a giant salamander.

Probably many have heard about this historical curiosity, but few people know that Scheuchzer was also one of the first to introduce Europeans to fossil insects. In 1709, he placed their images in his treatise The Flood Herbarium (Herbarium Diluvianum), dedicated to ancient plants. One of these insects, whose imprint was found in the Italian town of Monte Bolca, dates back to the middle Eocene. Scheuchzer mistook him for a dragonfly (French demoiselle ), but even then he got into a mess. Modern paleoentomologists suggest that Scheuchzer's "dragonfly", judging by the fact that it had only two wings, moreover, narrow and rather short, was actually a centipede mosquito. On the other hand, another insect that appeared on the pages of the Flood Herbarium could indeed be a dragonfly - only not an adult, but a larva, as evidenced by its massive body and rudimentary wings. This print was found in Ehningen, in the same place as the giant salamander. And in 1732, Scheuchzer, in his work “Sacred Physics, or the Natural History of the Bible” (Physique sacrée, ou Histoire naturelle de la Bible), published a drawing of another insect from Ehningen, which he called the scarab (French escarbot ). This is probably the first depiction of a fossil beetle in the history of science (Fig. 1.1).

This print was found in Ehningen, in the same place as the giant salamander. And in 1732, Scheuchzer, in his work “Sacred Physics, or the Natural History of the Bible” (Physique sacrée, ou Histoire naturelle de la Bible), published a drawing of another insect from Ehningen, which he called the scarab (French escarbot ). This is probably the first depiction of a fossil beetle in the history of science (Fig. 1.1).

Scheuchzer was one of the most famous supporters of diluvianism (from lat. diluvium - "flood"). This was the name of the doctrine that connected the emergence of fossil remains with the Flood, which allegedly destroyed the antediluvian flora and fauna and covered it with multi-meter layers of sand and clay. As a result of this cataclysm, Scheuchzer believed, stones with imprints of insects were formed, as well as all other fossils. It is no coincidence that in Sacred Physics, images of the centipede mosquito from Monte Bolca and the dragonfly larva from Ehningen decorated the vignette framing the dramatic scene with Noah's Ark. On it you can see how, not far from the ark, crowds of sinners doomed to certain death rush about in despair in pouring rain. For insects, as well as for sinners, God did not reserve a place in the ark. In any case, the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher, an older contemporary of Scheuchzer and no less prominent figure in early European science, thought so. Diluvianist views led Kircher to argue with the Italian Francesco Redi, whose experiments with rotten meat and fly larvae first questioned the idea of spontaneous generation of life. After all, if insects cannot spontaneously generate from silt and mud, then how did they recover after the flood? Kircher asked...

On it you can see how, not far from the ark, crowds of sinners doomed to certain death rush about in despair in pouring rain. For insects, as well as for sinners, God did not reserve a place in the ark. In any case, the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher, an older contemporary of Scheuchzer and no less prominent figure in early European science, thought so. Diluvianist views led Kircher to argue with the Italian Francesco Redi, whose experiments with rotten meat and fly larvae first questioned the idea of spontaneous generation of life. After all, if insects cannot spontaneously generate from silt and mud, then how did they recover after the flood? Kircher asked...

Previously, these and other mistakes of the Diluvians were considered as one of the numerous examples of the harmful influence of religion on science. However, modern historians of paleontology, such as Martin Rudwick of the University of California at San Diego, are convinced that diluvianism, on the contrary, was a big step forward: without the Old Testament flood story, the idea of \u200b\u200bthe organic origin of fossils would have been established much more difficult. Since childhood, we have been accustomed to the fact that the bones of dinosaurs and other similar finds are the remains of living beings that inhabited the Earth in the early eras. But at the dawn of the New Age, when paleontology took its first steps, this was completely unobvious. Many naturalists then believed that fossils grow directly in the earth's rocks, like crystals. They were not embarrassed that some of the "curly stones", as the fossils were then called, resembled plants or mollusk shells. Neoplatonic philosophy, popular during the Renaissance, proclaimed that the whole world was permeated with a network of secret correspondences. Everything affects everything according to the mysterious laws of sympathetic magic. It turned out quite a logical picture: some fossils, born under the influence of the plant world, look like leaves; others, such as belemnites, resemble arrowheads and other human artifacts; still others, what we now call the segments of crinoids, are stellate in shape, and therefore arose under the influence of the stars.

Since childhood, we have been accustomed to the fact that the bones of dinosaurs and other similar finds are the remains of living beings that inhabited the Earth in the early eras. But at the dawn of the New Age, when paleontology took its first steps, this was completely unobvious. Many naturalists then believed that fossils grow directly in the earth's rocks, like crystals. They were not embarrassed that some of the "curly stones", as the fossils were then called, resembled plants or mollusk shells. Neoplatonic philosophy, popular during the Renaissance, proclaimed that the whole world was permeated with a network of secret correspondences. Everything affects everything according to the mysterious laws of sympathetic magic. It turned out quite a logical picture: some fossils, born under the influence of the plant world, look like leaves; others, such as belemnites, resemble arrowheads and other human artifacts; still others, what we now call the segments of crinoids, are stellate in shape, and therefore arose under the influence of the stars.

The notion of fossils as a game of nature that had no real relation to the organisms of the past lasted until the end of the 17th century. We can verify this by leafing through Lithophylacii Britannici Ichnographia, a catalog of the fossil collection of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, published in 1699 by its curator Edward Lluyd with the support of Isaac Newton and other prominent scientists of that time. In the theoretical part of the catalog, Lluyd wrote that fossils originate in rock fissures from microscopic particles of animal and vegetable origin, the so-called animalcula , which, together with water vapor, rise from the ocean and then seep into the ground with raindrops. Lluid's work is also interesting in that it contains the first images of fossil insects and arachnids in the history of science (Fig. 1.2). Executed in a rather clumsy manner, they are placed on the same woodcut as samples of the Carboniferous flora collected in the vicinity of the English city of Gloucester. Nevertheless, Lluyd did not indicate the exact place where the insect prints were found, probably considering that such a trifle did not deserve a serious attitude.

Nevertheless, Lluyd did not indicate the exact place where the insect prints were found, probably considering that such a trifle did not deserve a serious attitude.

Scheuchzer, who published his "Flood Herbarium" only 10 years after Lluyd's catalogue, already professed a completely different approach to paleontological finds. After all, if fossils are not an accidental creation of natural forces like beautiful pebbles on the beach, but the remains of real animals that became victims of heavenly punishment, then their study is akin to reading a historical chronicle, accuracy and thoroughness are required here. Therefore, as with other fossils depicted in his books, Scheuchzer gave clear geographic references for fossil insects.

But insects are not so bad. Fossil shells of sea mollusks on hilltops in the center of Europe raised much more questions. Think about it: if it weren’t for the legend of the flood, how else would Scheuchzer’s contemporaries, who knew nothing about marine regressions and transgressions, be able to explain why the fossilized remains of marine organisms lie far from the seashore? she no longer needed the crutch of biblical authority. However, the basic ideas formulated by diluvianists that fossils are formed in the aquatic environment from dead organisms brought in by mineral sediment have remained with us. Like it or not, modern paleontology - and paleoentomology as one of its branches - emerged from the waters of the Flood, like Aphrodite was born from sea foam.

However, the basic ideas formulated by diluvianists that fossils are formed in the aquatic environment from dead organisms brought in by mineral sediment have remained with us. Like it or not, modern paleontology - and paleoentomology as one of its branches - emerged from the waters of the Flood, like Aphrodite was born from sea foam.

* * *

Anyone who has a dacha could watch flies, wasps and other six-legged animals floundering in a barrel for collecting rainwater. My wife told me that as a child she loved to save these poor fellows with her brother. But in ancient times there was no one to rescue them, and an insect that fell into a lake or sea lagoon went to the bottom. If the corpse was immediately covered with a layer of mineral sediment - clay suspension or lime turbidity, the process of its fossilization began, i.e., turning into a fossil. The sediment, like a blanket, isolates the insect from the external environment, preventing it from decomposing. The faster the sediment accumulated, the better the insect survived. Oxygen deficiency in the bottom layer also inhibited the processes of decay. Gradually, the sediment buried the insect deeper and deeper, it flattened, and the organic matter in its body was replaced by mineral matter. A flattened insect creates a discontinuity in a piece of hardened sediment, and if you hit such a piece with a hammer, it will crack exactly on the plane where the insect lies. As a result, you will have in your hands two mirror-symmetrical stone prints with the silhouette of an insect - they are also called "imprint" and "counter-imprint" [2] .

Oxygen deficiency in the bottom layer also inhibited the processes of decay. Gradually, the sediment buried the insect deeper and deeper, it flattened, and the organic matter in its body was replaced by mineral matter. A flattened insect creates a discontinuity in a piece of hardened sediment, and if you hit such a piece with a hammer, it will crack exactly on the plane where the insect lies. As a result, you will have in your hands two mirror-symmetrical stone prints with the silhouette of an insect - they are also called "imprint" and "counter-imprint" [2] .

With the rarest exceptions, only hard parts of ancient animals remain in sedimentary rocks - bones, teeth, shells, scales. When we find the shell of a prehistoric snail or the skeleton of a fossil reptile, we are left wondering what their body looked like. Take, for example, ammonites - the spirally twisted shells of these Mesozoic cephalopods are literally lying around underfoot in some places. This is the most banal and junk fossil. However, paleontologists still cannot say exactly how many tentacles the ammonites had, because their soft tissues are never preserved with the shell. With insects, we were much more fortunate - the outer skeleton, consisting of a strong cuticle, covers their entire body, from the tips of the antennae to the top of the abdomen. Therefore, unless after death the insect is torn into separate parts, it is preserved in its entirety. Even in the most ancient winged insects that lived in the Carboniferous period, over 300 million years ago, you can see the outline of the body and the coloration of dark and light stripes on the wings, as if you were in front of a black and white faded photograph. If you think about it, it's just fantastic! Imagine that archaeologists would take out from the burial mounds not the skeletons of ancient people, but their full-length ceremonial portraits, made in full accordance with the original.

However, paleontologists still cannot say exactly how many tentacles the ammonites had, because their soft tissues are never preserved with the shell. With insects, we were much more fortunate - the outer skeleton, consisting of a strong cuticle, covers their entire body, from the tips of the antennae to the top of the abdomen. Therefore, unless after death the insect is torn into separate parts, it is preserved in its entirety. Even in the most ancient winged insects that lived in the Carboniferous period, over 300 million years ago, you can see the outline of the body and the coloration of dark and light stripes on the wings, as if you were in front of a black and white faded photograph. If you think about it, it's just fantastic! Imagine that archaeologists would take out from the burial mounds not the skeletons of ancient people, but their full-length ceremonial portraits, made in full accordance with the original.

It takes a lot of patience, money, and hard physical labor to dig up a dinosaur skeleton. Each bone protruding to the surface must be glued and, together with the adjacent rock, plastered in a shipping container. To take out these multi-ton blocks from a remote area with bad roads, you need to hire special equipment. It is not surprising that the extraction of one large skeleton can take several years - and the same amount of time is needed to prepare this skeleton in the laboratory, having cleaned all its elements from the original stone shell. Finding fossil insects is another matter entirely. To make a valuable find, one successful blow with a hammer is enough. I put a pebble with an imprint in a matchbox and drove on. If part of the wing or leg of the insect goes into the rock, then in a couple of hours they can be released using a dissecting needle.

Each bone protruding to the surface must be glued and, together with the adjacent rock, plastered in a shipping container. To take out these multi-ton blocks from a remote area with bad roads, you need to hire special equipment. It is not surprising that the extraction of one large skeleton can take several years - and the same amount of time is needed to prepare this skeleton in the laboratory, having cleaned all its elements from the original stone shell. Finding fossil insects is another matter entirely. To make a valuable find, one successful blow with a hammer is enough. I put a pebble with an imprint in a matchbox and drove on. If part of the wing or leg of the insect goes into the rock, then in a couple of hours they can be released using a dissecting needle.

However, even paleoentomologists cannot do without patience – in order to find at least one worthwhile print, hundreds of stones have to be knocked out in vain. Not wanting to waste time on this, some scientists prefer to buy paleontological finds from the local population. This is how Chinese paleoentomologists came into possession of a huge collection of fossil insects from the Jurassic locality of Daohugou, located near the village of the same name in northeast China. Here, entire families make a living selling fossils. One Chinese professor even assured me that the local peasants were so adept at collecting fossil insects that they understood them better than his own students. However, non-professional collectors, driven by commercial motives, often miss small insects, hunting for large and showy specimens. The excessive abundance of such "grains" immediately catches the eye when working with both Chinese and, for example, Brazilian collections. In Brazil, where thousands of insects of the Early Cretaceous age come to the black market, stone-cutters from quarries where facing stone is mined earn extra money with their fees.

This is how Chinese paleoentomologists came into possession of a huge collection of fossil insects from the Jurassic locality of Daohugou, located near the village of the same name in northeast China. Here, entire families make a living selling fossils. One Chinese professor even assured me that the local peasants were so adept at collecting fossil insects that they understood them better than his own students. However, non-professional collectors, driven by commercial motives, often miss small insects, hunting for large and showy specimens. The excessive abundance of such "grains" immediately catches the eye when working with both Chinese and, for example, Brazilian collections. In Brazil, where thousands of insects of the Early Cretaceous age come to the black market, stone-cutters from quarries where facing stone is mined earn extra money with their fees.

A systematic search for fossil insects is possible only with the participation of professional entomologists. Thus, the largest collection in the world appeared in Moscow, numbering over 220,000 items from more than 1,000 locations located on the territory of the former USSR and Mongolia. It is stored in the Arthropod Laboratory [3] of the Paleontological Institute. A. A. Borisyak RAS and like a magnet attracts foreign specialists. During the 80 years of the laboratory's existence, almost every year its employees go on expeditions for new material.

It is stored in the Arthropod Laboratory [3] of the Paleontological Institute. A. A. Borisyak RAS and like a magnet attracts foreign specialists. During the 80 years of the laboratory's existence, almost every year its employees go on expeditions for new material.

Ordinary people, in order to be alone with nature, go hiking or fishing, spending their holidays and money on this. Maybe they get a lot of pleasure, but there is no practical benefit. But in a paleontological expedition there is every chance to combine business with pleasure. No internet, no phone. For weeks you live an almost primitive life, sitting by the fire, washing in the river, listening to the rumble of an approaching thunderstorm in the middle of an open field. Above the tent is a sky dotted with many stars, which the townspeople are deprived of. And stones, stones, fraught with a scientific sensation, one has only to hit with a hammer in the right place. And all this is at public expense. You return to Moscow, as if from another world . ..

..

I mentioned the river not in vain, because many localities of fossil insects, especially in European Russia and Siberia, are located on river banks. Like a pastry knife cutting a cake, the river cuts its course through ancient sedimentary rocks, so that their layers come to the surface along the walls of the coastal cliffs. You sit with a hammer on a steep bank, and under you the bends of the river go into the distance ... But often you have to look for ancient insects both in arid steppes and in deserts, where you need to bring drinking water with you, and there is no question of washing yourself maybe. Due to the fine dust that is carried in the air, the zippers of the tents break. Goats gallop over thorn-covered hills, birds of prey circle in the sky. However, paleoentomologists often work in the most common places - in quarries, road cuts, construction pits. In South Africa, chalk insects were collected in a diamond mine that looked like a giant funnel. All these scars with which man has scarred the face of the planet, like deserts and rivers with scree banks, are good for the absence of vegetation that hides ancient rocks under them. In order for the past of the Earth to appear outward, it is necessary to remove its “skin” in the form of grass and forest. Paleoentomologists searching for fossil insects are themselves like flies that flock to open wounds on the body of the planet.

In order for the past of the Earth to appear outward, it is necessary to remove its “skin” in the form of grass and forest. Paleoentomologists searching for fossil insects are themselves like flies that flock to open wounds on the body of the planet.

Cliffs, deserts and quarries attract any paleontologist, whether he works with ancient insects, fish, corals or mollusks. However, fossil insects, unlike many other fossils, are found mainly in the sediments of continental water bodies, such as oxbow lakes and lakes [4] . In sedimentary rocks of marine origin, they also come across, but in significantly smaller quantities. Indeed, the chances of insects being in the middle of the endless sea are small, while they fall into the lakes all the time - the closer to the shore, the more often. But, alas, continental deposits are dated much worse than marine ones. The sea has existed for many millions of years over a vast area, being quite uniform in temperature and other characteristics, so that the change of species of marine organisms occurs synchronously in different parts of its water area. Based on the succession of these broad-ranging changing species, geologists compare the sediments of ancient seas and then determine which periods of geologic time they correspond to. But this technique does not work with lake layers.

Based on the succession of these broad-ranging changing species, geologists compare the sediments of ancient seas and then determine which periods of geologic time they correspond to. But this technique does not work with lake layers.

The duration of the existence of a small lake can be calculated in thousands of years, and it takes a lot of trickery to compare its sediments with those of other lakes, each of which had its own conditions and its own set of species. It is sometimes possible to tie insect-bearing layers to the global geochronological scale using radioisotope dating, which requires zircons - special crystals of volcanic origin. However, there are no zircons in the sediments of those lakes located far from active volcanoes. So it turns out that the age of a number of localities of fossil insects is known quite approximately, sometimes with an error of 10-15 million years. With the dating of amber, there is even greater uncertainty, since it is not always clear whether it fell into the host rock immediately or was reburied a second time. Therefore, instead of giving the absolute age of certain ancient insects, in this book I will often talk about geological periods of great duration, which cover the approximate interval of their existence. So, the phrase "Late Jurassic beetles" should be understood as beetles that lived closer to the end of the Jurassic, somewhere 163-145 million years ago.

Therefore, instead of giving the absolute age of certain ancient insects, in this book I will often talk about geological periods of great duration, which cover the approximate interval of their existence. So, the phrase "Late Jurassic beetles" should be understood as beetles that lived closer to the end of the Jurassic, somewhere 163-145 million years ago.

Insect stories for preschoolers

Contact

Insect stories for preschoolers

- Details

- Author: Galina Obnorskaya

- Category: Reading

Rating: 5 / 5

Please rate Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 These short stories about insects, like others, were written for children with attention and memory problems.

It is difficult for them to listen to long stories, to remember and retell them as well.

Nature stories are most suitable for the gradual development of self-control and learning to work with a book. It is useful to combine working with text with crafts from different materials, drawing.

Insect stories

The author of informative stories about insects is Galina Obnorskaya, a child psychologist.

Why do bees dance

?The honey bee has a family. It's called Roy. Sisters - bees live together. The bee will find a lot of honey, tell the rest.

She can't speak! It just buzzes. It's true, he can't speak, but he can dance.

Bee's dance is simple. She flies in a circle or in a figure eight, buzzes loudly and wags her belly. As if saying:

- I found a lot of honey! Follow me quickly.

Questions.

- Why is a bee called a honey bee?

- What is the name of the bee family?

- How does a bee transmit information to other bees?

- Name the bee affectionately.

- How to call a very large bee, very small? ..

- Whose wings does the bee have?

Dragonfly

Dragonflies live near water: rivers, streams, lakes. The dragonfly flies very fast, deftly dodges. The speed is such that a person rushing on a bicycle can catch up.

Dragonflies are hunters. They have excellent eyesight. Dragonflies fly like helicopters over water in search of prey. Their prey are small mosquitoes, midges. A large dragonfly attacks smaller dragonflies. Does not disdain a caterpillar.

When a dragonfly flies, it folds its legs into a house. It turns out to be a trap. A mosquito gaped and got into the house from her tenacious paws. The dragonfly immediately sends it into the mouth.

Dragonflies are beautiful insects. Take care of them. They decorate nature.

Questions.

- Where do dragonflies live?

- What do they eat?

- How does a dragonfly hunt?

- Name a dragonfly affectionately.

- How to call a very large dragonfly, very small? ..

- Whose wings does a dragonfly have?

Ladybug

The small ladybug beetle is known to everyone. She has two rigid and strong wings of yellow, orange or red color with black dots. And under them soft wings are hidden.

Top wings for protection. Lower wings for flight. It is necessary for the ladybug to fly, the upper wings rise, the lower ones straighten out, and the beetle flies.

Don't hurt the ladybug. She is a true friend and helper. Pests - aphids - settle on plants in the garden and in greenhouses. Aphids suck juices from leaves. The leaves dry up, curl up and fall off.

A ladybug eats aphids to save plants. Ladybugs are specially bred and released into gardens. There she fights aphids, helping people.

Questions.

- Why does a ladybug need different wings?

- What does the beetle eat?

- How do aphids harm plants?

Ants

During the warm season, ants can be found everywhere. They run about their ant affairs back and forth. They seem so small and stupid. In fact, ants are smart insects. Their brain works like a powerful computer. That's what the scientists say.

They run about their ant affairs back and forth. They seem so small and stupid. In fact, ants are smart insects. Their brain works like a powerful computer. That's what the scientists say.

Ants are strong insects. An ant lifts a load 50 times heavier than itself.

The little ant won't be offended. He sprays the offenders with formic acid. Formic acid is caustic. It even causes burns.

People are not afraid of formic acid. But you can’t touch the ants, ruin the anthills. Ants are beneficial insects in the forest.

Questions.

- What is the name of the ant house?

- How does the ant's brain work?

- What does an ant spray on offenders?

- Name an ant affectionately.

- How to call a very large ant, very small? ..

- Whose head does the ant have?

Fly

Everyone knows the Fly. She is mean and annoying. Buzzing, buzzing.

The fly has six legs and four wings.

Transparent wings. Two front wings for flight. Hind wings for balance in flight. They are called bugs.

Two front wings for flight. Hind wings for balance in flight. They are called bugs.

The fly has Velcro on its feet. They help the fly crawl even upside down.

The fly carries various diseases. She crawls everywhere, and dirt with microbes sticks to her paws. A fly will crawl over a clean place and leave microbes on it.

Questions.

- Where does the fly live?

- What are the wings of a fly?

- Why can a fly crawl upside down?

- Why does a fly carry various diseases?

- Name a fly affectionately.

- How to call a very large fly, very small? ..

Butterflies

Butterflies are the beauty of nature. There are many around. Butterfly colors are different. It pleases our eyes.

Butterflies are small and large. Their body is covered with small scales.

Butterflies feed on the nectar of flowers. They drink it with their proboscis. In spring, when there are still few flowers, butterflies drink birch or maple sap.

Questions

- What color are the butterflies?

- What size are they?

- What is the body of butterflies covered with?

- What do butterflies eat?

Mosquito

Guess the riddle: "Grey. With two wings. It flies - it rings. It bites painfully." The mosquito has a mustache and a proboscis on its head. The mosquito makes no sound. The ringing comes from mosquito wings. A mosquito flies, and its wings rattle thinly. It makes a call.

We don't like mosquitoes. A mosquito will sit on a person or animal, pierce the skin with its proboscis and drink the blood. Poisonous mosquito saliva will get under the skin. Because of this poison, the bite site itches for a long time. Mosquitoes fly to heat. In the evenings and at night, warm animals are easier to find. Only mosquitoes bite us. And mosquitoes drink flower nectar. Their proboscis is very thin. They will not bite through thick human skin and animal skin.

Questions

- How many wings does a mosquito have?

- What sound does a mosquito make when it flies?

- Where does this sound come from?

- What do mosquitoes eat?

- How do mosquitoes find who to bite?

- Why does the bite site itch and itch for a long time?

- Name a mosquito affectionately.

Learn more