Harold and the purple crayon story

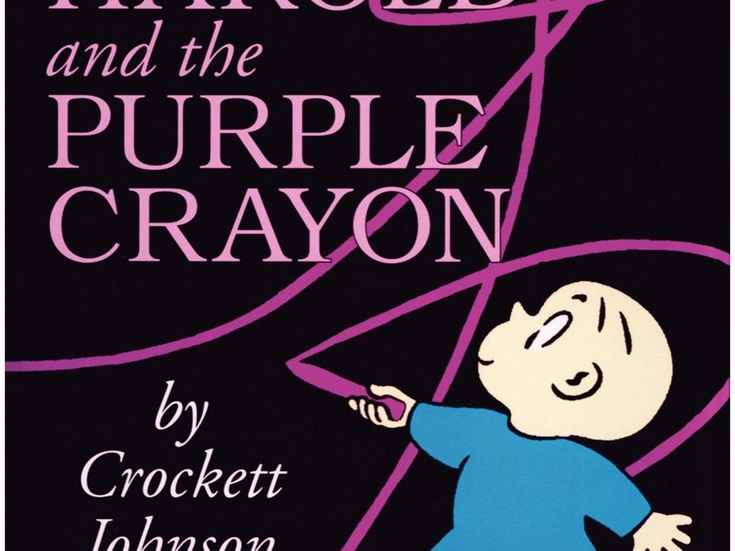

Harold and the Purple Crayon

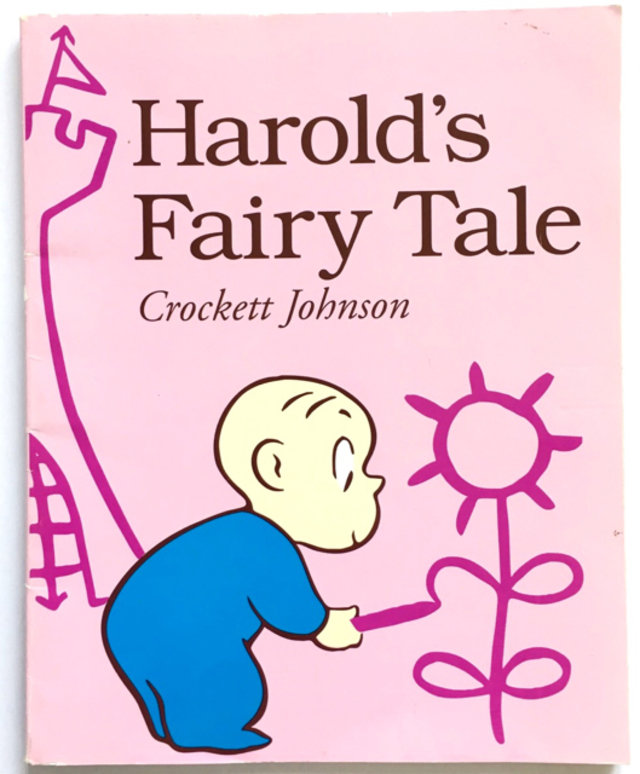

None Harold’s creativity and imagination know no bounds in this timeless classic. Harold wanted to go on a walk but didn’t have a path to walk on or a moon to light his way. With his purple crayon in hand, he drew himself a path and a moon that followed him. And so began his journey through his own imagination. Walking along the path, he decided that he needed a forest, so he drew a tree—he didn’t want to get lost! One idea growing from another, Harold’s story kept on until he made it into his bed and, exhausted from his adventure, fell fast asleep with his purple crayon next to him. What imaginative adventure will you draw with your crayon? show full description Show Short DescriptionClassics

Share your favorite stories with your child. Enjoy classic bedtime stories from your childhood like Chicka Chicka Boom Boom, Chicken Little, Where the Wild Things Are, and Harold and the Purple Crayon.

view all

Chicka Chicka Boom Boom

Harry the Dirty Dog

Wheels on the Bus

Chicken Little

The Snowy Day

The Dot

Where the Wild Things Are

Duck on a Bike

Swimmy

Harold and the Purple Crayon

One membership, two learning apps for ages 2-8.

TRY IT FOR FREE

Full Text

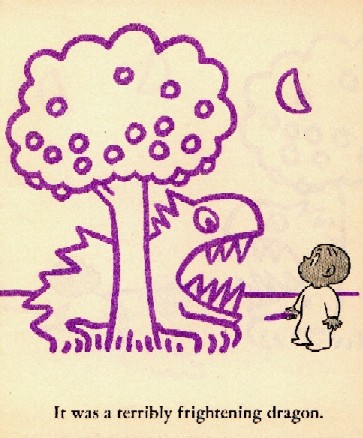

One evening, after thinking it over for some time, Harold decided to go for a walk in the moonlight. There wasn’t any moon, and Harold needed a moon for a walk in the moonlight. And he needed something to walk on. He made a long straight path so he wouldn’t get lost. And he set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him. But he didn’t seem to be getting anywhere on the long straight path. So he left the path for a shortcut across a field. And the moon went with him. The shortcut led right to where Harold thought a forest ought to be. He didn’t want to get lost in the woods, so he made a very small forest with just one tree in it. It turned out to be an apple tree. The apples would be very tasty, Harold thought, when they got red. So he put a frightening dragon under the tree to guard the apples. It was a terribly frightening dragon. It even frightened Harold. He backed away. His hand, holding the purple crayon, shook. Suddenly, he realized what was happening. But by then, Harold was over his head in an ocean. He came up thinking fast. And in no time, he was climbing aboard a trim little boat. He quickly set sail. And the moon sailed along with him. After he had sailed long enough, Harold made land without much trouble. He stepped ashore on the beach, wondering where he was. The sandy beach reminded Harold of picnics. And the thought of picnics make him hungry. So he laid out a nice simple picnic lunch.

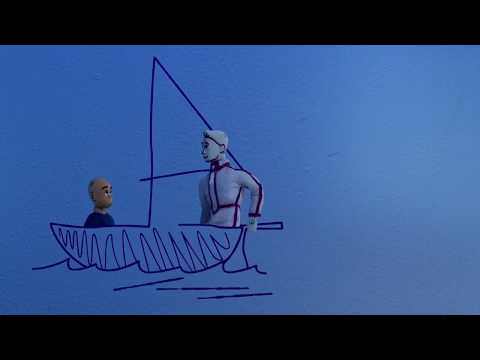

So he left the path for a shortcut across a field. And the moon went with him. The shortcut led right to where Harold thought a forest ought to be. He didn’t want to get lost in the woods, so he made a very small forest with just one tree in it. It turned out to be an apple tree. The apples would be very tasty, Harold thought, when they got red. So he put a frightening dragon under the tree to guard the apples. It was a terribly frightening dragon. It even frightened Harold. He backed away. His hand, holding the purple crayon, shook. Suddenly, he realized what was happening. But by then, Harold was over his head in an ocean. He came up thinking fast. And in no time, he was climbing aboard a trim little boat. He quickly set sail. And the moon sailed along with him. After he had sailed long enough, Harold made land without much trouble. He stepped ashore on the beach, wondering where he was. The sandy beach reminded Harold of picnics. And the thought of picnics make him hungry. So he laid out a nice simple picnic lunch. There was nothing but pie. But there were all nine kinds of pie that Harold liked best. When Harold finished his picnic, there was quite a lot left over. He hated to see so much delicious pie go to waste, so Harold left a hungry moose and a deserving porcupine to finish it up. And, off he went, looking for a hill to climb to see where he was. Harold knew that the higher up he went, the farther he could see. So he decided to make the hill into a mountain. If he went high enough, he thought, he could see the window of his bedroom. He was tired, and he felt he ought to be getting to bed. He hoped he could see his bedroom window from the top of the mountain. But as he looked down over the other side he slipped— and there wasn’t any other side of the mountain. He was falling in thin air. But luckily he kept his wits and his purple crayon. He made a balloon, and he grabbed onto it. And he made a basket under the balloon big enough to stand in. He had a fine view from the balloon, but he couldn’t see his window.

There was nothing but pie. But there were all nine kinds of pie that Harold liked best. When Harold finished his picnic, there was quite a lot left over. He hated to see so much delicious pie go to waste, so Harold left a hungry moose and a deserving porcupine to finish it up. And, off he went, looking for a hill to climb to see where he was. Harold knew that the higher up he went, the farther he could see. So he decided to make the hill into a mountain. If he went high enough, he thought, he could see the window of his bedroom. He was tired, and he felt he ought to be getting to bed. He hoped he could see his bedroom window from the top of the mountain. But as he looked down over the other side he slipped— and there wasn’t any other side of the mountain. He was falling in thin air. But luckily he kept his wits and his purple crayon. He made a balloon, and he grabbed onto it. And he made a basket under the balloon big enough to stand in. He had a fine view from the balloon, but he couldn’t see his window. He couldn’t even see a house. So he made a house with windows. And he landed the balloon on the grass in the front yard. None of the windows was his window. He tried to think where his window ought to be. He made some more windows. He made a big building full of windows. He made lots of buildings full of windows. He made a whole city full of windows. But none of the windows was his window. He couldn’t think where it might be. He decided to ask a policeman. The policeman pointed the way Harold was going anyway, but Harold thanked him. And he walked along with the moon, wishing he was in his room and in bed. Then, suddenly, Harold remembered. He remembered where his bedroom window was when there was a moon. It was always right around the moon. And then Harold made his bed, got in it, and he drew up the covers. The purple crayon dropped on the floor. And Harold dropped off to sleep.

He couldn’t even see a house. So he made a house with windows. And he landed the balloon on the grass in the front yard. None of the windows was his window. He tried to think where his window ought to be. He made some more windows. He made a big building full of windows. He made lots of buildings full of windows. He made a whole city full of windows. But none of the windows was his window. He couldn’t think where it might be. He decided to ask a policeman. The policeman pointed the way Harold was going anyway, but Harold thanked him. And he walked along with the moon, wishing he was in his room and in bed. Then, suddenly, Harold remembered. He remembered where his bedroom window was when there was a moon. It was always right around the moon. And then Harold made his bed, got in it, and he drew up the covers. The purple crayon dropped on the floor. And Harold dropped off to sleep.

1

We take your child's unique passions

2

Add their current reading level

3

And create a personalized learn-to-read plan

4

That teaches them to read and love reading

TRY IT FOR FREE

Harold and the Purple Crayon - Teaching Children Philosophy

by Crockett Johnson

FILTERS: mind, reality, grade-1-2, prek-k

Book Module Navigation

Summary »

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion »

Questions for Philosophical Discussion »

Summary

Harold and the Purple Crayon examines a number of difficult questions about the nature of reality.

Harold thinks it over for some time and decides to go for a walk in the moonlight. This may seem unremarkable, but it is not. There is no moon. There is nothing to walk on. There is nowhere to go. The only things that are real are Harold and the purple crayon.

Read aloud video by Harper Kids

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

The overarching theme of Harold and the Purple Crayon is deciphering reality. As a rather ambiguous idea, the discussion of “reality” will throw the children into a fun and active topsy-turvy discussion of what it means to be real, and how one gives objects the power of reality. In a world represented by a blank page, Harold is free to draw his surroundings with his big purple crayon. Is Harold playing make-believe? Is that different from what is real? The questions in this set revolve around the children’s perception of reality. Harold interacts with his drawings in a very “real” way.

The first question in this set addresses a secondary character that follows Harold throughout the story: the moon. The idea of the moon as a constant in the night sky is one children tend to agree with. What complicates this situation, however, is the fact that when the moon is absent in Harold’s world, he draws it with his purple crayon above him in the “sky”. This is left the children to question the validity or reality of Harold’s world. If Harold can draw a moon in the sky, it seems that he could not possibly be existing in the “real” world. And furthermore, he must simply be pretending because, as the children may point out, no one could draw a “real” moon in the sky. Or could they? What makes the moon we observe any more “real” than Harold’s moon? This line of questioning leads the children to discuss the relationship between perception and reality. Must things be experiential in order to be real? Or can they exist simply in our minds? In philosophical study, this may seem similar to the debate of the empiricists versus the rationalists. Rationalists like Descartes tended to believe that the reality of objects was in our ability to rationally understand them.

The idea of the moon as a constant in the night sky is one children tend to agree with. What complicates this situation, however, is the fact that when the moon is absent in Harold’s world, he draws it with his purple crayon above him in the “sky”. This is left the children to question the validity or reality of Harold’s world. If Harold can draw a moon in the sky, it seems that he could not possibly be existing in the “real” world. And furthermore, he must simply be pretending because, as the children may point out, no one could draw a “real” moon in the sky. Or could they? What makes the moon we observe any more “real” than Harold’s moon? This line of questioning leads the children to discuss the relationship between perception and reality. Must things be experiential in order to be real? Or can they exist simply in our minds? In philosophical study, this may seem similar to the debate of the empiricists versus the rationalists. Rationalists like Descartes tended to believe that the reality of objects was in our ability to rationally understand them. At the same time, empiricists like Locke felt that the interaction with objects in a physical way gave them a sense of universal reality. Obviously, the children will not be familiar with this philosophical distinction, but through the debate and discussion over the reality of Harold’s objects, they can come to know the issues involved.

At the same time, empiricists like Locke felt that the interaction with objects in a physical way gave them a sense of universal reality. Obviously, the children will not be familiar with this philosophical distinction, but through the debate and discussion over the reality of Harold’s objects, they can come to know the issues involved.

The second and third question sets revolve around Harold’s experience. As the questions in the second set indicate, Harold seems to be in danger during part of the story; he may even be afraid of the objects he draws. For some of the students, this may indicate a level of reality that is not at first apparent. To have feelings, either sensory or emotional, about an object indicates that the object holds some form of power over its observer. This power is translated to designate a level of “reality” as compared to the surrounding world. Then the task is outlining the differences or definitions that make something real. These qualities in Harold’s drawings further blur the line between what is presumably the “real” world outside of the story. When Harold falls from the hill that he climbs, and when he stumbles into the ocean, he has drawn, it seems as though his life is seriously in danger. This fear is a form of power Harold has passively given to his drawings.

When Harold falls from the hill that he climbs, and when he stumbles into the ocean, he has drawn, it seems as though his life is seriously in danger. This fear is a form of power Harold has passively given to his drawings.

On the other hand, one may question if that gives the ocean or the rock the physical reality to harm Harold. Physical reality and the scientific properties therein sometimes indicate a kind of absolute reality that is independent of Harold. The children can then begin to explore the idea how we know whether objects continue to exist when no one is there to observe them. The physical properties, such as atoms and molecules seem to give objects a sense of absolute reality. However, the majority of people will never see a tree at a purely molecular level; they will see a tree as brown bark and green leaves, using subjective measurements that exist within each individual. The students will then be able to draw their own connections about whether believing in something or fearing it gives it reality for the observer and consequently an absolute reality independent of the observer.

In the third question set, the conclusions from the second set can be reevaluated. Although the emotions or physical danger that Harold may experience as “real”, where do they exist? In this stage, the children can begin to question the idea that Harold could be dreaming this entire purple-crayon-created world. If Harold is dreaming all of this, it seems easier to swallow: we as an audience can attribute these “fantasies” to something we know and also experience. However, the next step in the debate is a discussion of the reality of dreams. Are dreams “real” in the way we have previously defined the term (see question set 1)? The students may then choose to reevaluate their definition of “real”.

In the fourth question set, we begin to discuss the idea of Harold as a character in these drawings. If these are Harold’s drawings and they belong to him, could accidents happen within them? In this way the students will continue to discuss and stretch the reality of Harold’s world. The role of ownership is undefined in the story and in the lives of the children themselves. Do people have control over the events that occur in their lives, are they purely accidental, or can they be attributed to another force? The students can describe Harold’s accidents and relate them to their own in a connection that will help them to understand the concept universally.

The role of ownership is undefined in the story and in the lives of the children themselves. Do people have control over the events that occur in their lives, are they purely accidental, or can they be attributed to another force? The students can describe Harold’s accidents and relate them to their own in a connection that will help them to understand the concept universally.

The fifth question set explores how Harold also is subject to being lost in his own drawing, lost in the world he created. He travels on a long and perilous journey to find his bedroom window, and when he finally does, the audience is left to wonder whether he even needed to walk through the cities of windows to find his own at all. If this crayon gives Harold the power to create his bedroom anywhere, then it is strange that he is so intent on searching for his “real” window. Being so submerged in his own creations might give Harold an ultimate sense of power and reality, but at this point of the story, as Harold frantically searches for his window, he fears that he cannot escape the world he has created. This leads the students to question the world “outside” of Harold’s world. They can compare themselves with Harold and thus apply his story to their own existence.

This leads the students to question the world “outside” of Harold’s world. They can compare themselves with Harold and thus apply his story to their own existence.

The final question set asks the children to address an event common to their own lives and understand the role of reality in it. All the children are likely to relate to Harold’s nine-pie picnic, in that they have enjoyed pretending to have a picnic with pretend food. However, in the illustration and description of the book, it is obvious that Harold is drawing the pies in one moment and then has supposedly eaten them in another. This picnic is reminiscent of a make-believe tea party that you throw for you and your stuffed animals to enjoy. In this case, it is a hungry moose and a deserving porcupine that interacts with Harold. For the children who may have previously defined Harold as un-realistic, this is an example intended to make them define their positions. What is going on in this story? Is it make-believe, a dream, reality, or something else? Encouraging the students to back up their beliefs with reasons and evidence will help them to formulate and understand this debate-style dialogue.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

And he set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him. We know that Harold wants to go on a journey under the moonlight, but when he does not see the moon shining, he uses his purple crayon to draw a moon in the sky.

- Is the moon that Harold draws the same as the moon we can see in the sky at night?

- Which moon is the “real” moon?

- What makes it “real”?

When Harold falls into the “ocean” that he draws, do you think his life is in danger? Do you think he could drown?

- Do you think Harold is afraid of the ocean?

- Does his fear make the drawing more “real”?

- Do emotions and beliefs make things real?

The boat seems to save Harold from drowning. Do you think that what is happening to Harold is real?

- Are the things happening to Harold in his mind or somewhere else?

- Could it be that everything happening to Harold is a dream?

- Are dreams real?

When Harold steps over the edge of the mountain, he begins to fall through the air. Do you think that it was an accident?

Do you think that it was an accident?

- Did Harold know that was going to happen to him?

- Can there be accidents in Harold’s world even if he’s drawing them?

- Can you make an accident happen?

If Harold is drawing his own world, why does it take him so long to find his window?

- Do you think Harold could get lost in the world he is drawing?

- Could he be imagining that he is lost?

- What does it mean to be lost?

Harold draws himself a picnic with nine different pies.

- Have you ever had an imaginary tea party or an imaginary picnic?

- Is that what Harold is doing in the story? Is he playing make-believe?

- Or could the events “really” be happening to him?

- What’s the difference between “make-believe” and “real”?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Claire Bartholome. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.

Download & PrintEmail Book Module View en Español Back to All Books

Purple crayon | Papmambuk

What is this book about

Harold is a little boy who went on a journey through the white paper. He creates his own world with a purple chalk and starts by drawing the moon. Then he creates a world: roads, trees, sea, mountains, magical purple creatures and toothy monsters, a balloon, a boat with a sail, houses with windows, and even a policeman. And everywhere next to him the moon invariably travels.

At first the boy enjoys the adventure, and then he is looking for his home and cannot find it. Only at the end of the book does he remember that at home he always sees this moon from the window. He draws a window around the moon - and finds himself in his room. Now he can go to sleep on the painted bed, because his walk under the moon has come to an end.

Crockett Johnson wrote a book about baby with purple crayon back in 1955, and readers liked it so much that Crockett Johnson published a couple of dozen more books about baby Harold and his crayon. Based on these books, cartoons and serials are shot, performances are staged, and computer games are invented.

Many writers have taken up the idea of using crayons to add to the world around the character. For example, in Anthony Brown's Bear Hunt (1979), a bear draws something with a magic pencil to escape two hunters. In Aaron Becker's Journey, Adventure, and Return trilogy of silent books, a boy and a girl draw doors to a magical world where miracles happen with colorful crayons.

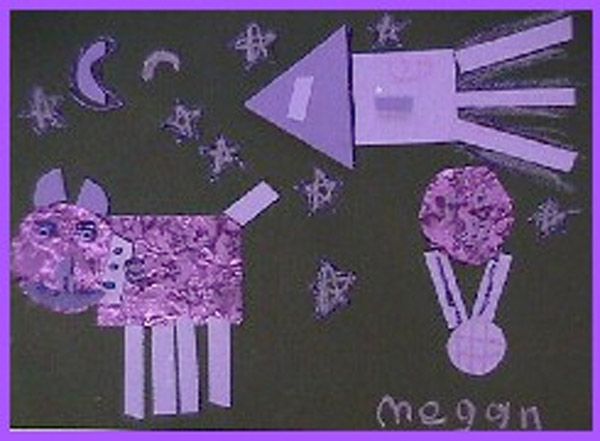

Characters and props

• A long roll of paper, or several white sheets stacked one after the other.

• Violet crayon.

• A small paper figurine of Harold with a chalk in his hand, copied from the book and cut along the outline. If you draw a figure from two sides, Harold can be rotated left and right.

If you draw a figure from two sides, Harold can be rotated left and right.

Harold and the Purple Chalk book from which the character will appear Some of the elements can be drawn and cut in advance: balloon cabin, picnic animals, blanket, boat. You can draw and cut out the moon and high-rise buildings with many windows in advance.

How to Tell a Story on Paper

Hide the paper boy between the pages of Harold and the Purple Chalk and lay out the roll of paper. Have your child call Harold or say the magic words. Let Harold appear right out of the book - shake him out on paper and he'll go on a journey.

This story moves in a linear fashion, like a long roll of paper or several white sheets stacked one after the other. While I was training, I was drawing in a regular album, but then I realized that I needed the continuity of the story, and I remembered what can be drawn on a roll - this is how a feeling of landscape, space, linearity of history and time appears.

Some of the elements I drew in advance and cut out: balloon cabin, picnic animals, blanket. The balloon cabin and blanket cover the baby.

So, Harold gets on the white sheet. He draws the moon, and then the road. Thus begins his journey.

Then he goes on and draws a tree. A monster with sharp teeth appears behind the tree, which frightens the boy.

Harold steps back. His hands are trembling - and so the straight line of the road becomes the surface of the sea. The boy cannot swim and is drowning. I completed the story by drawing bubbles in the water and a shark.

Harold is a resourceful boy: he draws a sailboat and then sails on it.

Soon he decides to go ashore and draws an anchor and a line of land.

Harold is hungry, he draws a blanket and plates of pies.

At first he eats everything himself, but then he decides to invite the animals to the picnic. In the book, it is an elk and a porcupine. We invited the previously drawn animals from the fairy tale "Teremok" to a picnic: a fox, a wolf, a mouse and a hare. But you can also draw animals with purple chalk, as required by history.

We invited the previously drawn animals from the fairy tale "Teremok" to a picnic: a fox, a wolf, a mouse and a hare. But you can also draw animals with purple chalk, as required by history.

After eating, Harold continues the line of the landscape and draws a high mountain, which he climbs.

He does not have time to draw the descent from the mountain and falls.

Harold is not discouraged. He holds the world in his hands. In any situation, he remembers that he can draw anything. He draws a balloon.

Cabin painted on the balloon so that the boy could be inside it.

Then Harold sees the house and remembers his house. He looks into all the windows and wonders where his window is.

Then a huge painted city appears. Houses can be drawn in advance and placed on paper. There must be many houses and many windows in the city in order to have the feeling of being lost as a little boy. When we were drawing with Anya, she added light in the windows with a yellow pencil.

Harold remembers that if he is lost, he needs to find a policeman, and draws him. The policeman tells the boy where to look for his house.

He walks forward and suddenly notices the moon. She always travels with him, wherever he is. I drew a new moon in each of the situations, but you can draw a moon in advance that will move with the boy.

Harold realizes that if he wants to be at home, he must see the moon through his window. He does so and ends up in his room.

He draws a bed and goes to bed, covered with a blanket drawn in advance. He puts the purple crayon next to the crib.

Harold had such a trip under the moon.

At Anya's request, parents came to the room to kiss Harold and tell him a bedtime story.

Anya initiated the second color - yellow. They light up the windows in the houses, the moon and the light of the lamp in Harold's room. Later, I proposed to complete the world, and there were stars, a new balloon in which all the animals fit, a green plane, a beautiful ship with wind-blown sails, a tree and an endless space for travel.