How to teach letter sound correspondence

Literacy Instruction for Individuals with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Down Syndrome, and Other Disabilities

What are letter-sound correspondences?

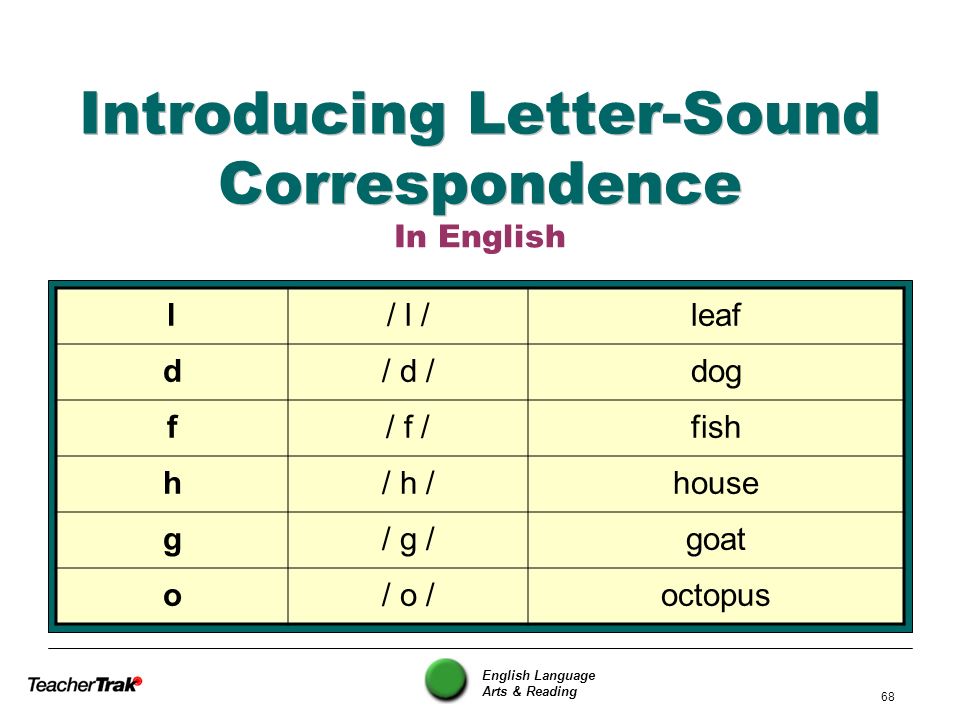

Letter-sound correspondences involve knowledge of

- the sounds represented by the letters of the alphabet

- the letters used to represent the sounds

Top

Why is knowledge of letter-sound correspondences important?

Knowledge of letter-sound correspondences is essential in reading and writing

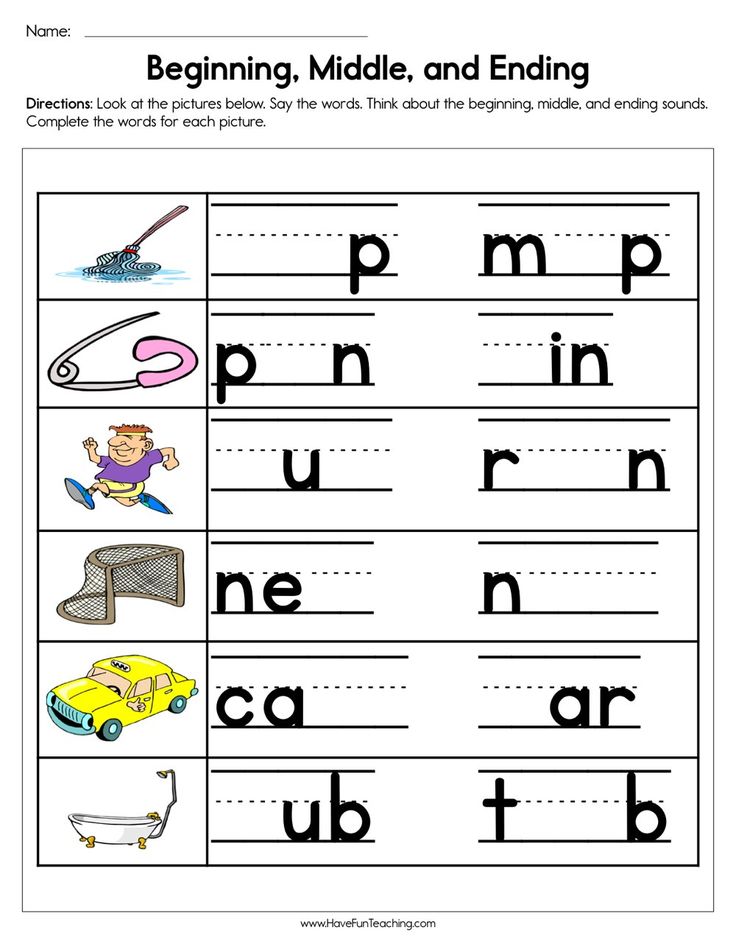

- In order to read a word:

- the learner must recognize the letters in the word and associate each letter with its sound

- In order to write or type a word:

- the learner must break the word into its component sounds and know the letters that represent these sounds.

Knowledge of letter-sound correspondences and phonological awareness skills are the basic building blocks of literacy learning.

These skills are strong predictors of how well students learn to read.

Top

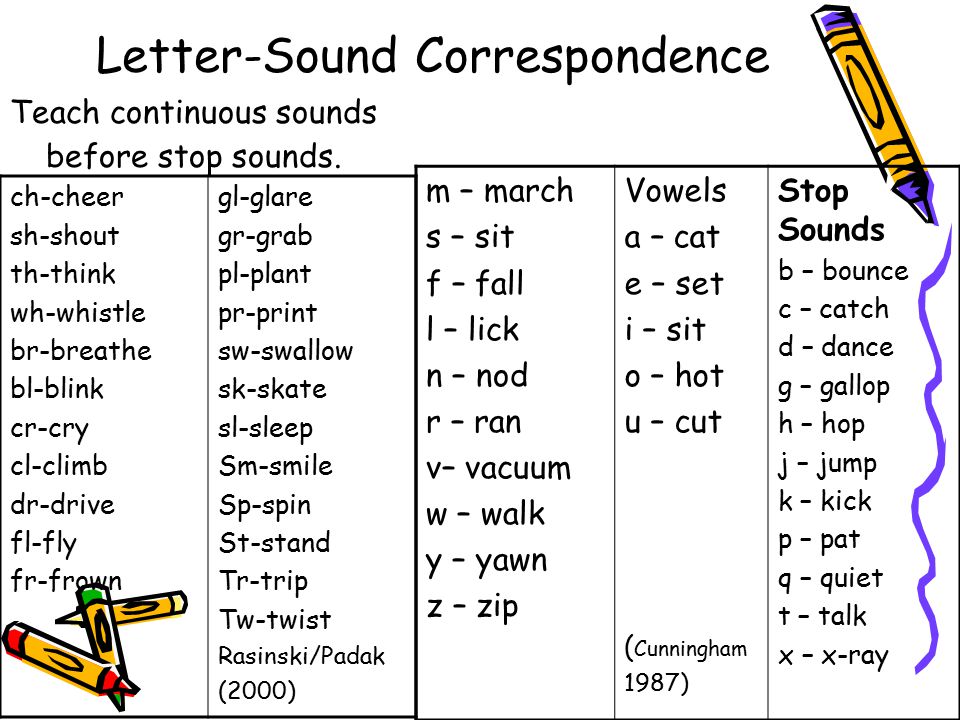

What sequence should be used to teach letter-sound correspondence?

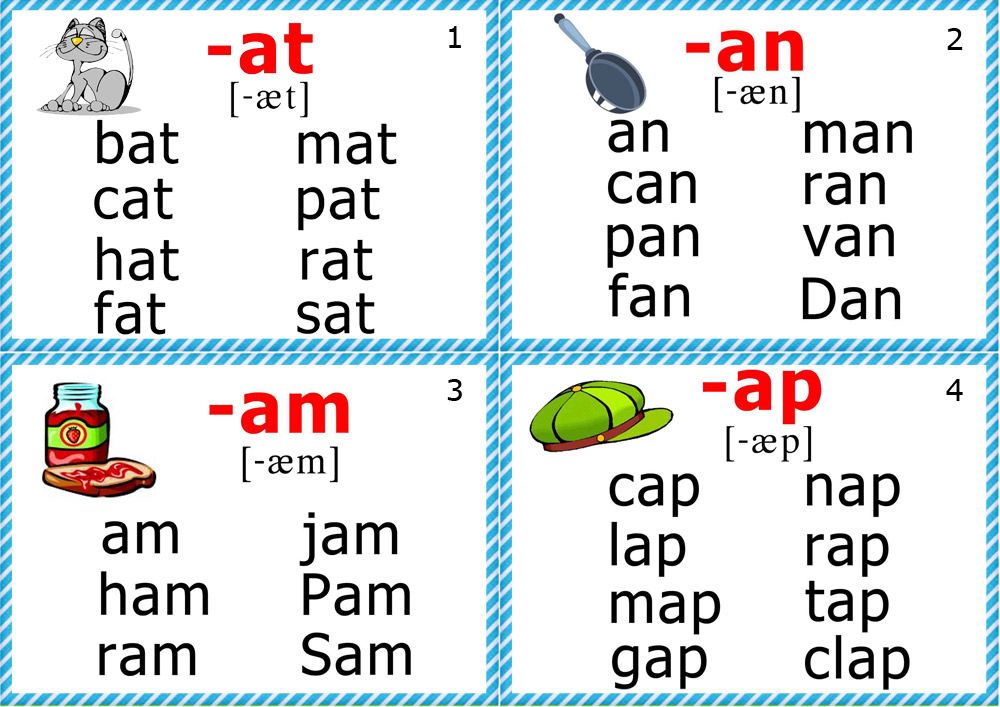

Letter-sound correspondences should be taught one at a time. As soon as the learner acquires one letter sound correspondence, introduce a new one.

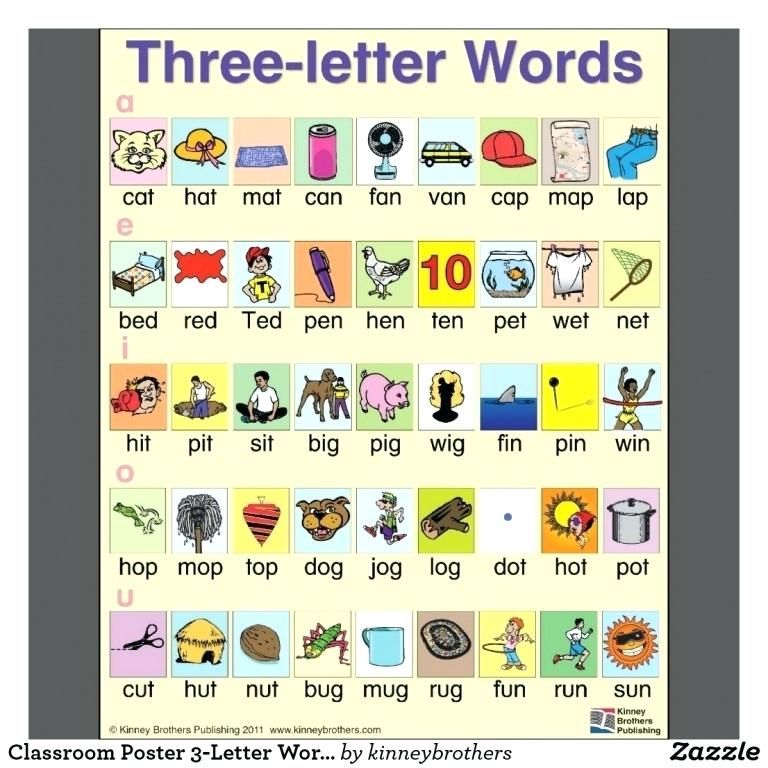

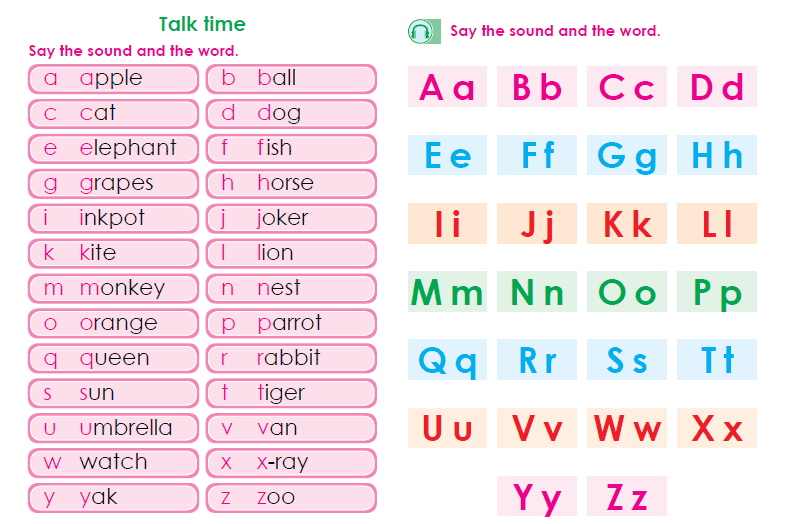

We suggest teaching the letters and sounds in this sequence

- a, m, t, p, o, n, c, d, u, s, g, h, i, f, b, l, e, r, w, k, x, v, y, z, j, q

This sequence was designed to help learners start reading as soon as possible

- Letters that occur frequently in simple words (e.g., a, m, t) are taught first.

- Letters that look similar and have similar sounds (b and d) are separated in the instructional sequence to avoid confusion.

- Short vowels are taught before long vowels.

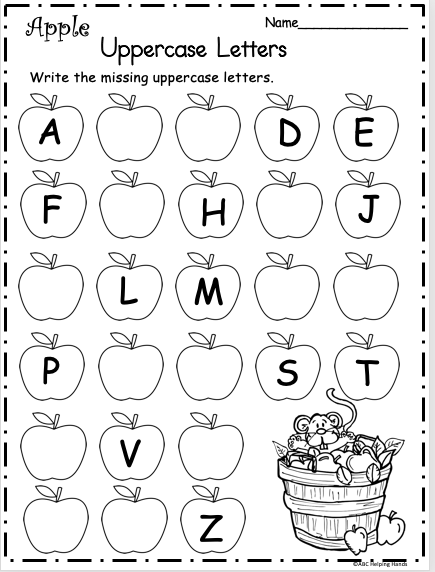

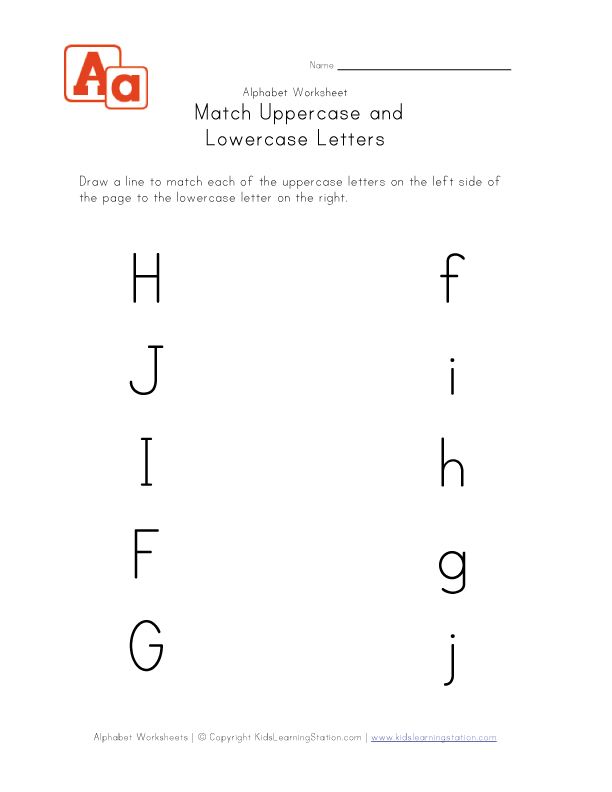

- Lower case letters are taught first since these occur more frequently than upper case letters.

The sequence is intended as a guideline. Modify the sequence as required to accommodate the learner’s

- prior knowledge

- interests

- hearing

Top

Is it appropriate to teach letter names as well as letter sounds?

Start by teaching the sounds of the letters, not their names. Knowing the names of letters is not necessary to read or write. Knowledge of letter names can interfere with successful decoding.

Knowing the names of letters is not necessary to read or write. Knowledge of letter names can interfere with successful decoding.

- For example, the learner looks at a word and thinks of the names of the letters instead of the sounds.

Top

Sample goal for instruction in letter-sound correspondences

The learner will

- listen to a target sound presented orally

- identify the letter that represents the sound

- select the appropriate letter from a group of letter cards, an alphabet board, or a keyboard with at least 80% accuracy

Top

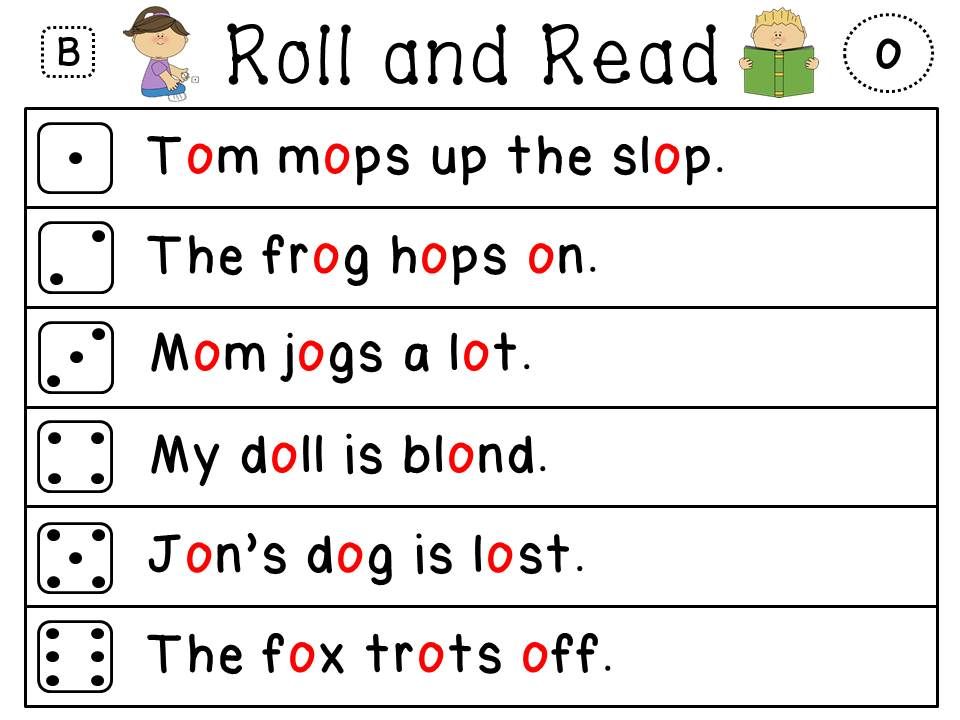

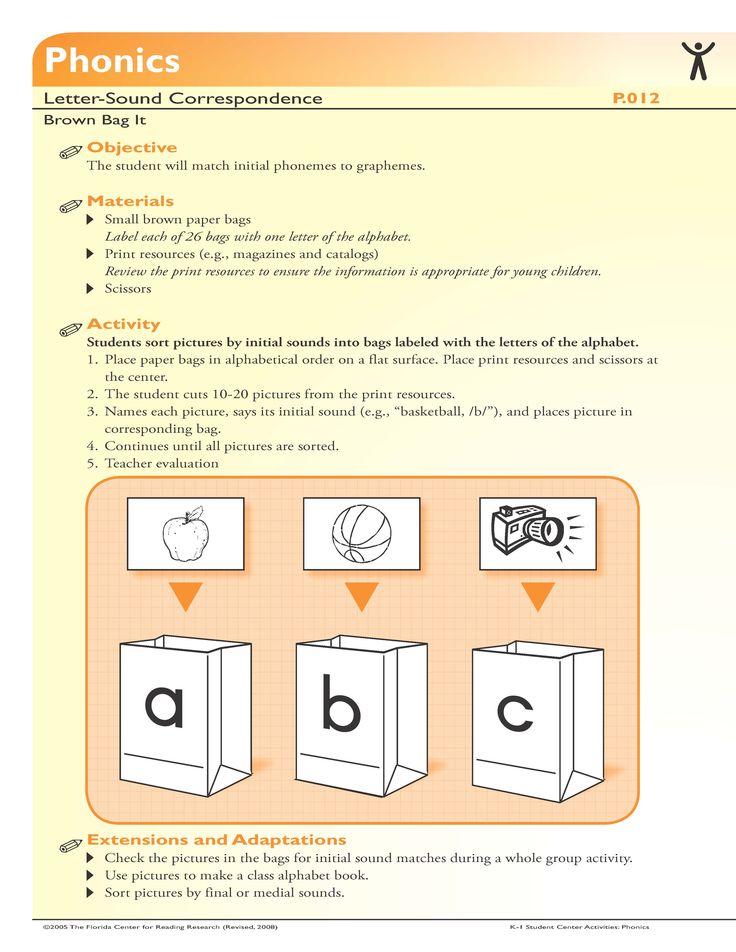

Instructional Task

Here is an example of instruction to teach letter-sound correspondences

- The instructor

- introduces the new letter and its sound

- shows a card with the letter m and says the sound “mmmm”

After practice with this letter sound, the instructor provides review

- The instructor

- says a letter sound

- The learner

- listens to the sound

- looks at each of the letters provided as response options

- selects the correct letter

- from a group of letter cards,

- from an alphabet board, or

- from a keyboard.

Top

Instructional Materials

Various materials can be used to teach letter-sound correspondences

- cards with lower case letters

- an alphabet board that includes lower case letters

- a keyboard adapted to include lower case letters

Here is an example of an adapted keyboard that might be used for instruction once a student knows many of the letter-sound correspondences.

The learner must

- listen to the target sound – “mmmm”

- select the letter – m – from the keyboard

Top

Instructional Procedure

The instructor teaches letter-sound correspondences using these procedures:

- Model

- The instructor demonstrates the letter-sound correspondence for the learner.

- Guided practice

- The instructor provides scaffolding support or prompting to help the learner match the letter and sound correctly.

- The instructor gradually fades this support as the learner develops competence.

- The instructor provides scaffolding support or prompting to help the learner match the letter and sound correctly.

- Independent practice

- The learner listens to the target sound and selects the letter independently.

- The instructor monitors the learner’s responses and provides appropriate feedback.

Top

Student Example

Krista is 8 years old in this video

- Krista has multiple challenges, including a hearing impairment, a visual impairment, and a motor impairment. She also has a tracheostomy.

- We started to work with Krista when she was 8 years old. At that time, she was in a special education class at school and was not receiving literacy instruction.

- She uses sign approximations to communicate with others. She also uses a computer with speech output (a Mercury with Speaking Dynamically Pro software). Because of her hearing impairment, she does best when she receives augmented input (sign and speech).

- This video was taken after 3 weeks of instruction.

- Krista is learning letter-sound correspondences. So far she has been introduced to the letter sounds for m and b

- Janice is providing instruction; Marissa, a graduate student at Penn State, is learning about literacy instruction and helping to collect data; and Krista’s parents and nurse are watching the session, excited about her progress.

- Janice

- provides an array of letter cards as response options

- says one of the target letter sounds

- Krista

- listens to the sound

- points to the letter that makes the target sound

- After 3 weeks (approximately 3 hours) of instruction, Krista has successfully learned the letter sounds – m and b.

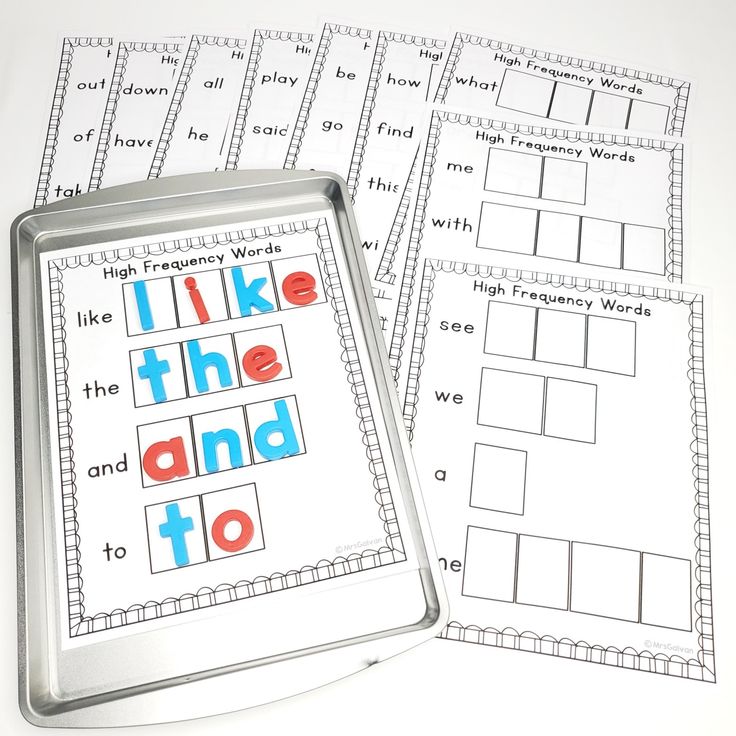

- Over the next months, we introduced the other letter sounds gradually. We also worked on recognition of high interest sight words, decoding skills, and shared reading activities.

- Krista made excellent progress in all activities. Click to learn more about Krista’s success learning literacy skills despite the many challenges she faced.

Top

Pointers

There are a wide range of fonts. These fonts use different forms of letters, especially the letter a.

- Initially use a consistent font in all instructional materials

- Later, as the learner develops competence, introduce variations in font.

Top

Last Updated: February 19, 2019

teaching letter-sound correspondence -

Teaching Letter-Sound Corrospondence

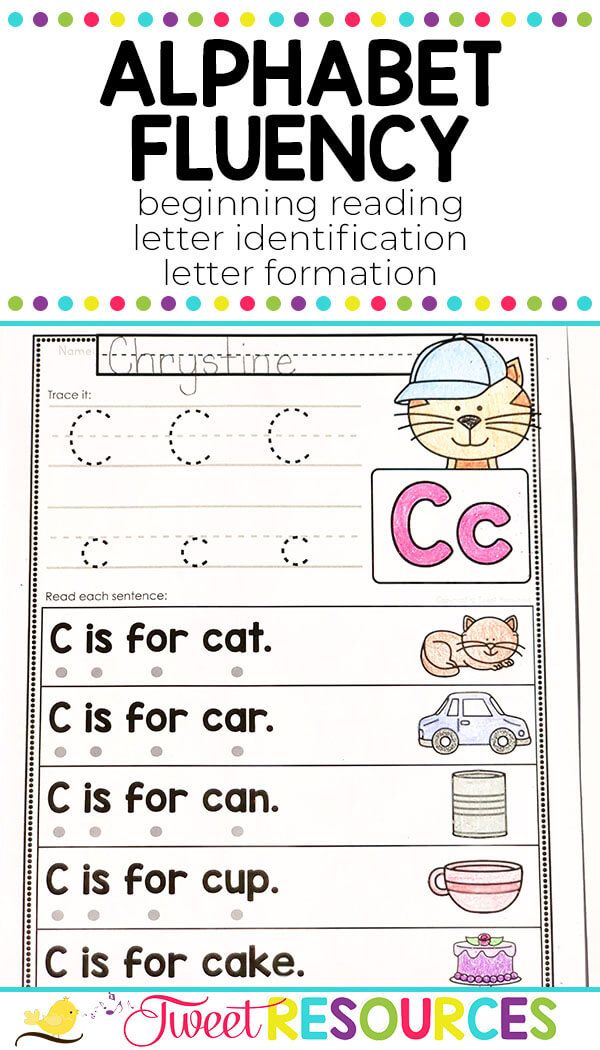

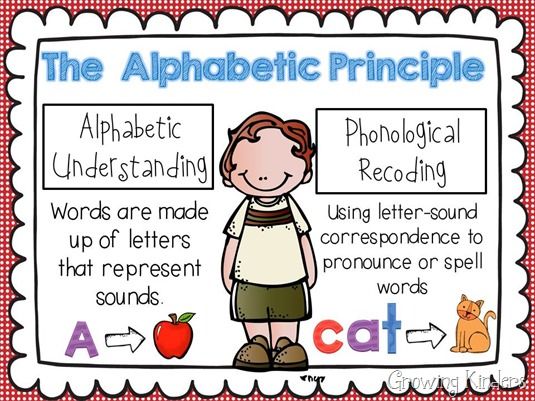

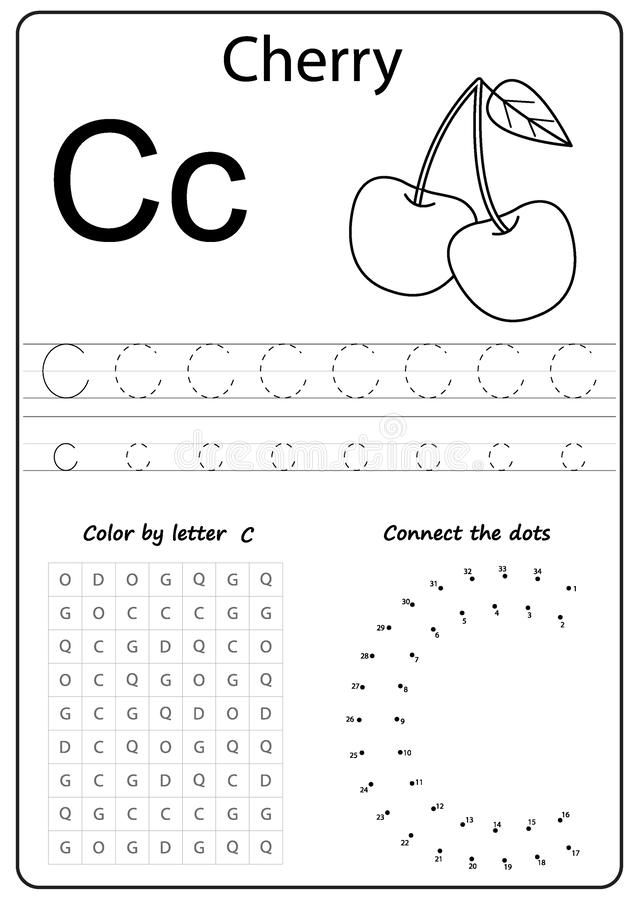

Teaching letter-sound correspondence is a critical component in learning the alphabet, teaching phonics, and essential to reading success. So let’s talk about letter-sound correspondence and how you can teach it effectively!

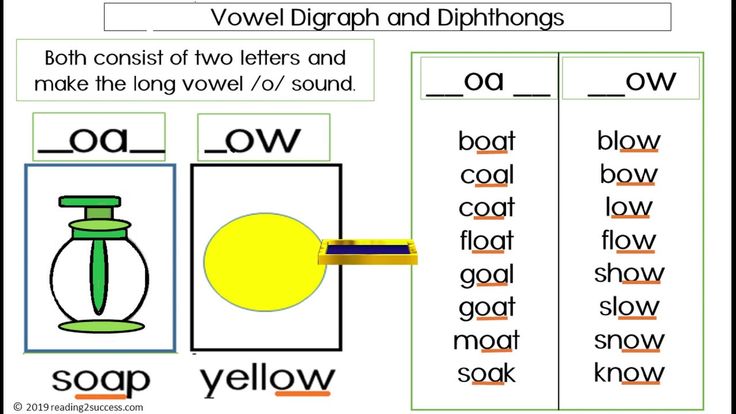

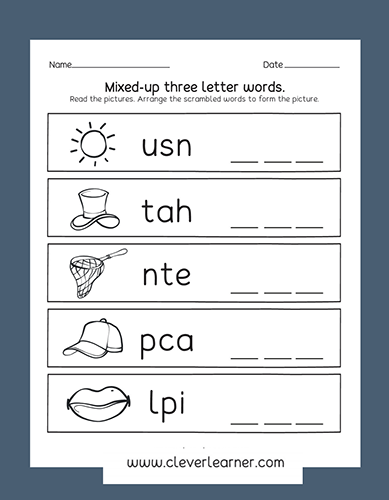

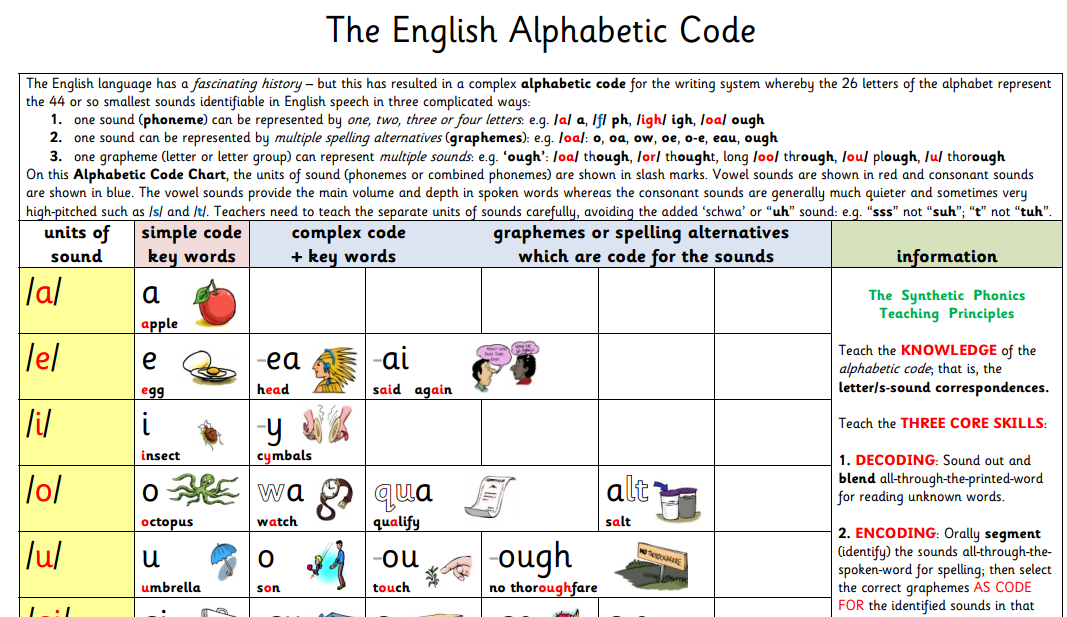

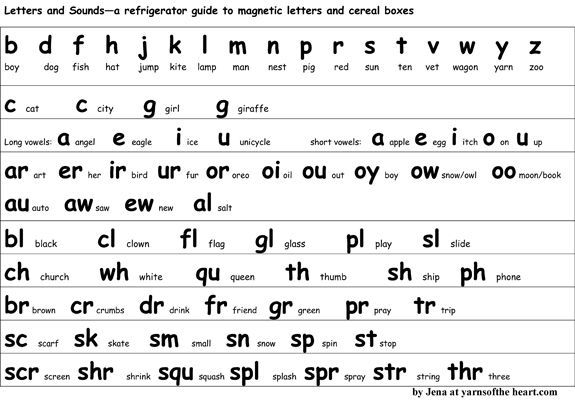

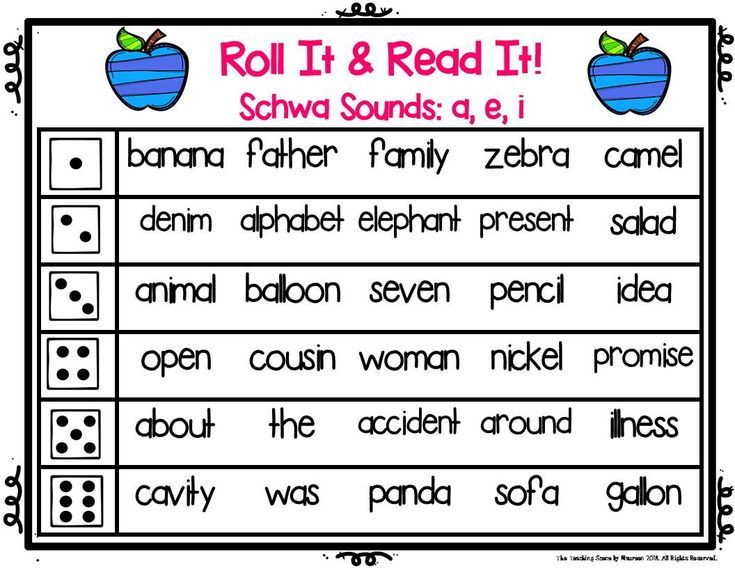

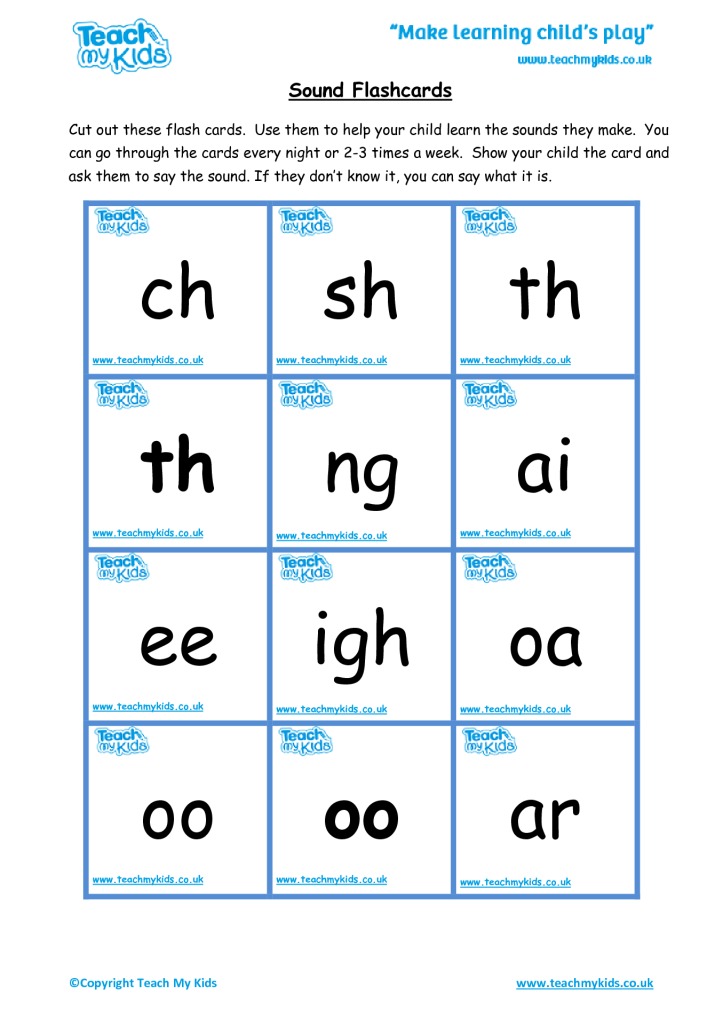

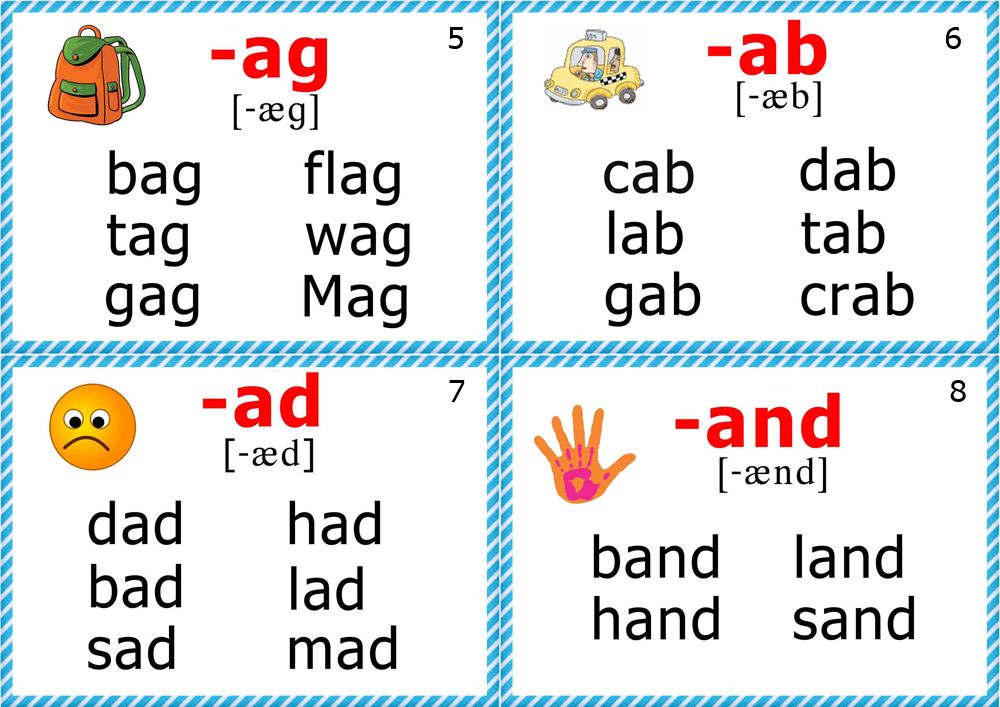

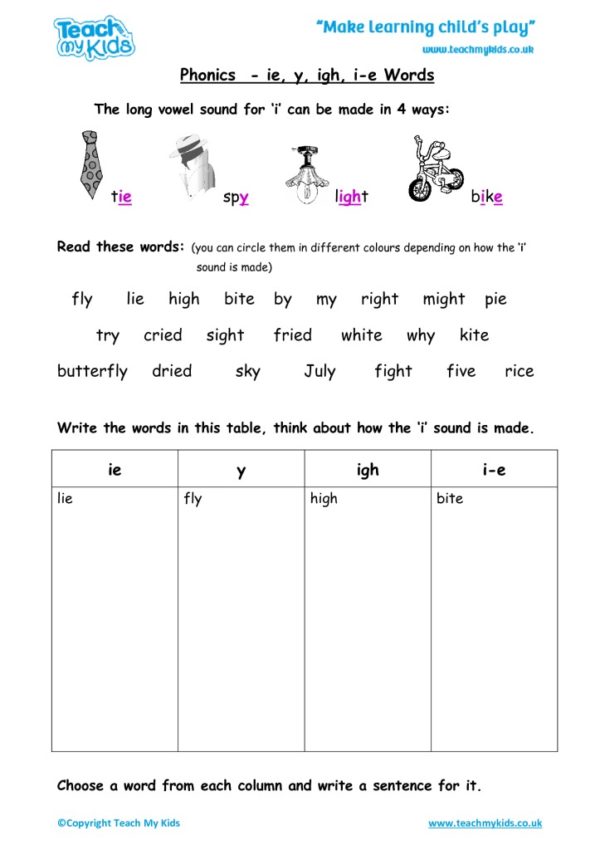

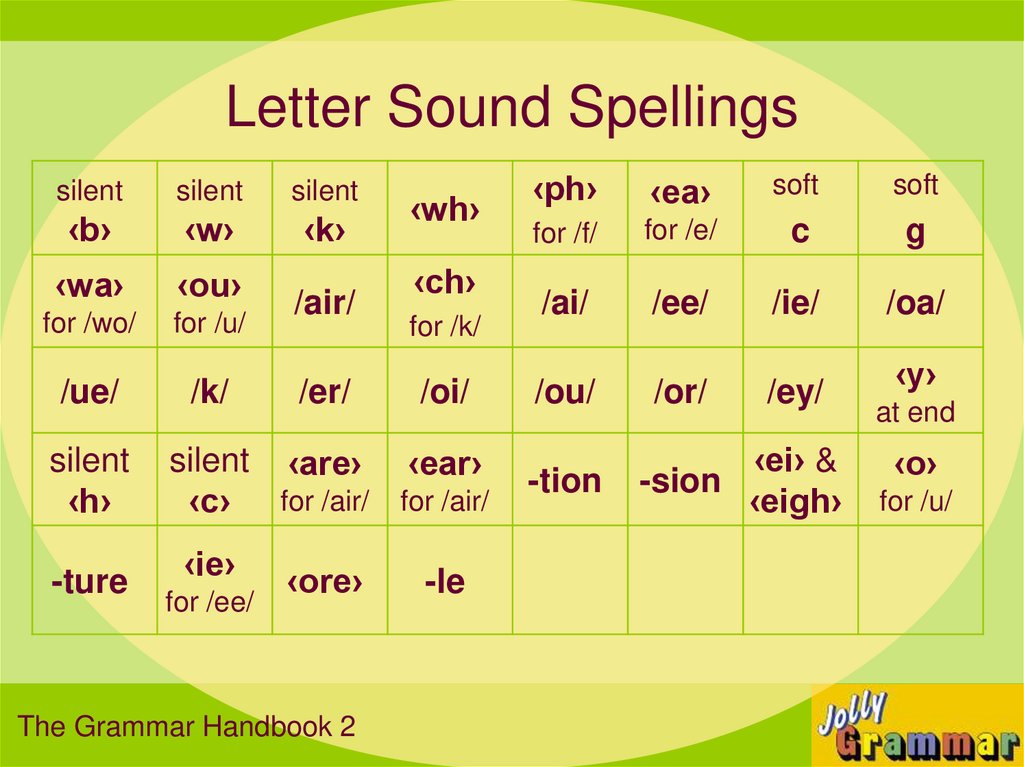

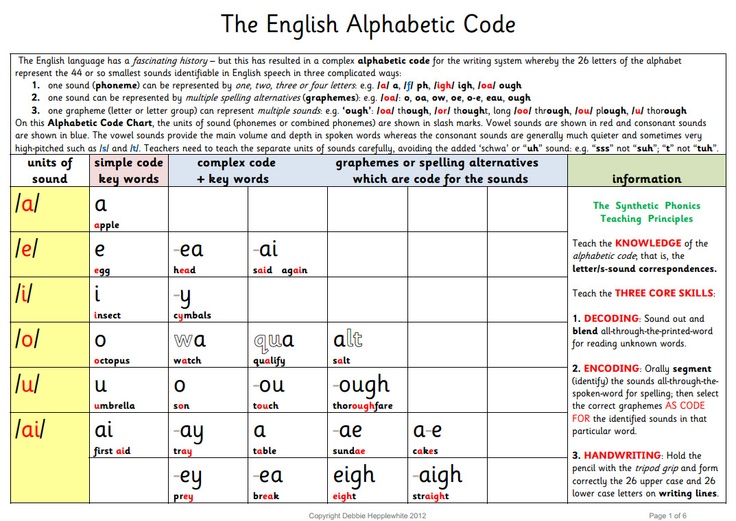

What is letter-sound correspondence? Letter-sound correspondence is the knowledge of the sounds/phonemes connected to individual letters. Although there are only 26 letters of the English alphabet, there are 44 Phonemes or individual distinct units of sound. Phonemes also include letter combinations like blends and digraphs, but I will only be focussing on the letters of the alphabet for this post.

Although there are only 26 letters of the English alphabet, there are 44 Phonemes or individual distinct units of sound. Phonemes also include letter combinations like blends and digraphs, but I will only be focussing on the letters of the alphabet for this post.

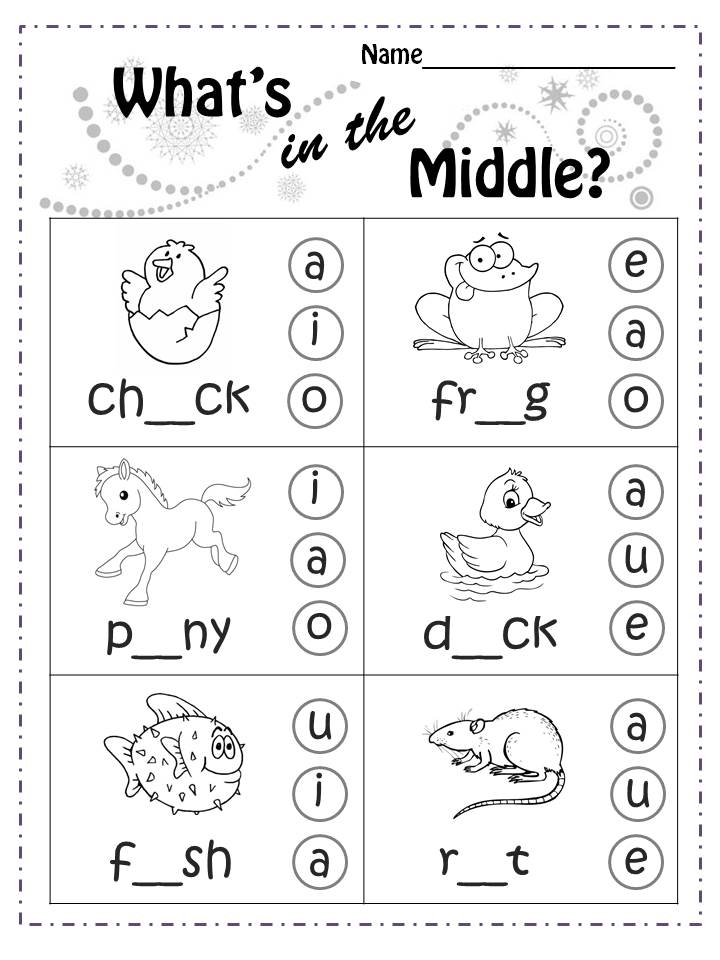

When to teach letter-sound correspondence? As you teach letter recognition, it is just as important to teach letter-sound correspondence understanding. I have found that teaching letter-sound correspondence with letter identification increases phonemic awareness, phonics understanding, decoding words, and reading skills overall.

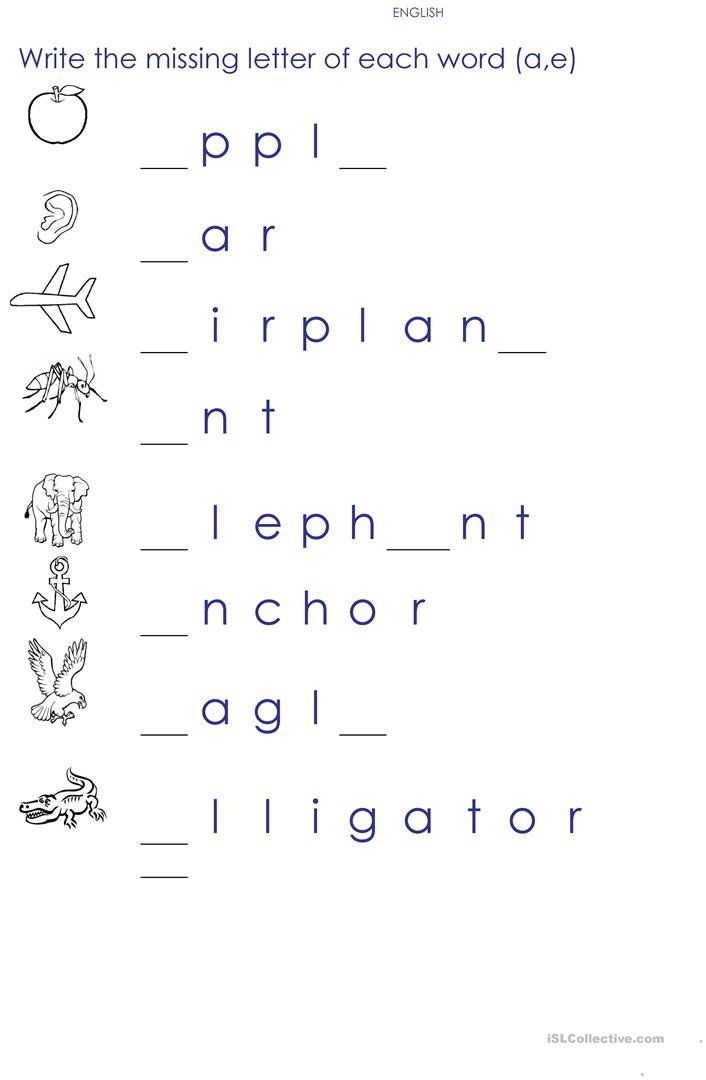

How do you teach letter-sound correspondence? Teaching letter-sound correspondences should be done one at a time. Once a letter-sound has been mastered introduce the next one. To facilitate early reading the best, try teaching letters and letter-sounds by those found most often in text. I use the order below.

- a, m, t, p, o, n, c, d, u, s, g, h, i, f, b, l, e, r, w, k, x, v, y, z, j, q

HERE ARE SOME THINGS TO CONSIDER WHEN IMPLEMENTING THIS SEQUENCE.

- Teach frequently used letters first aids early reading. (e.g., a, m, t)

- Teach letters that look similar and have similar sounds (e.g. b and d) in separate lessons to help avoid confusion.

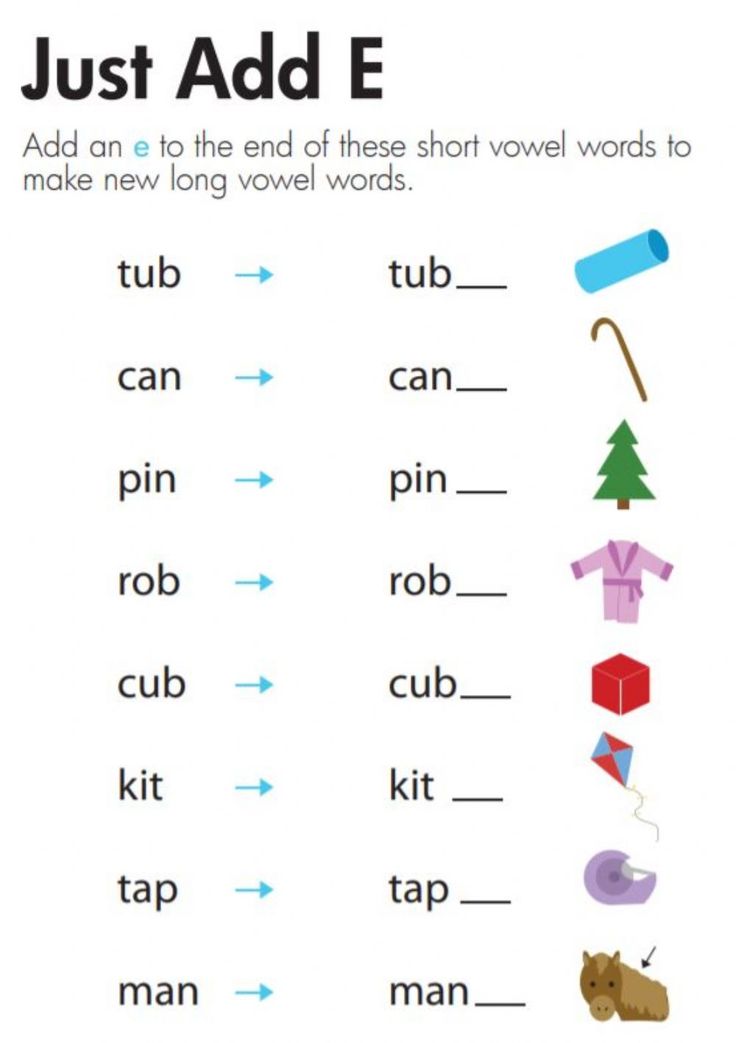

- Short vowels should be taught before long vowels.

- Lower case letters are taught before upper case letters.

Teach unique sounds once the others are mastered.

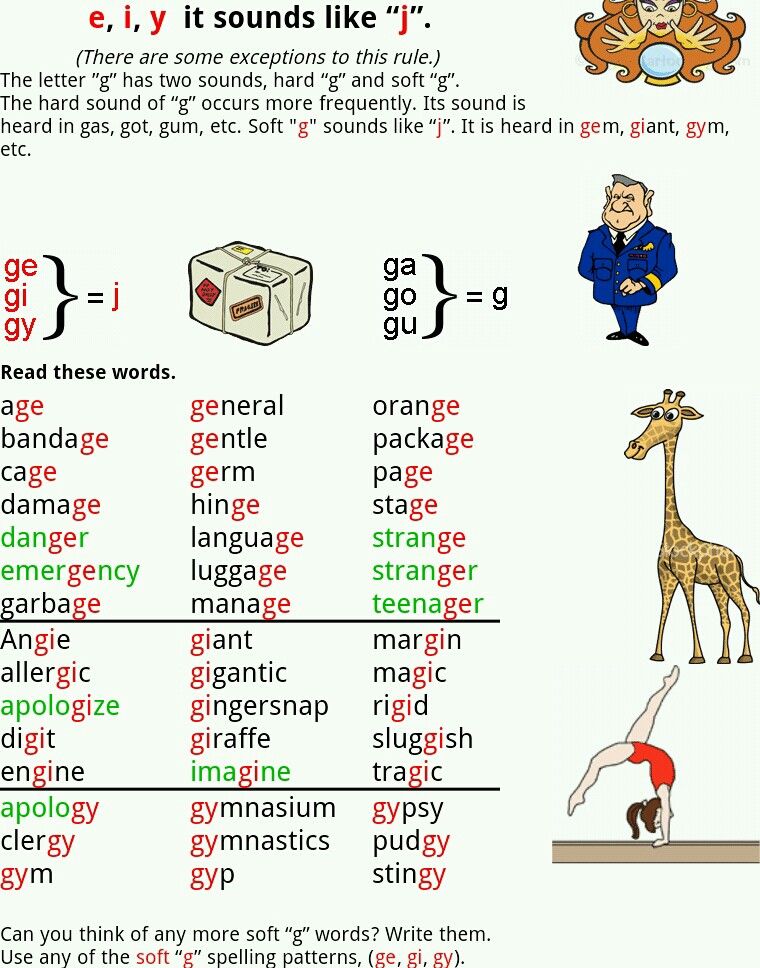

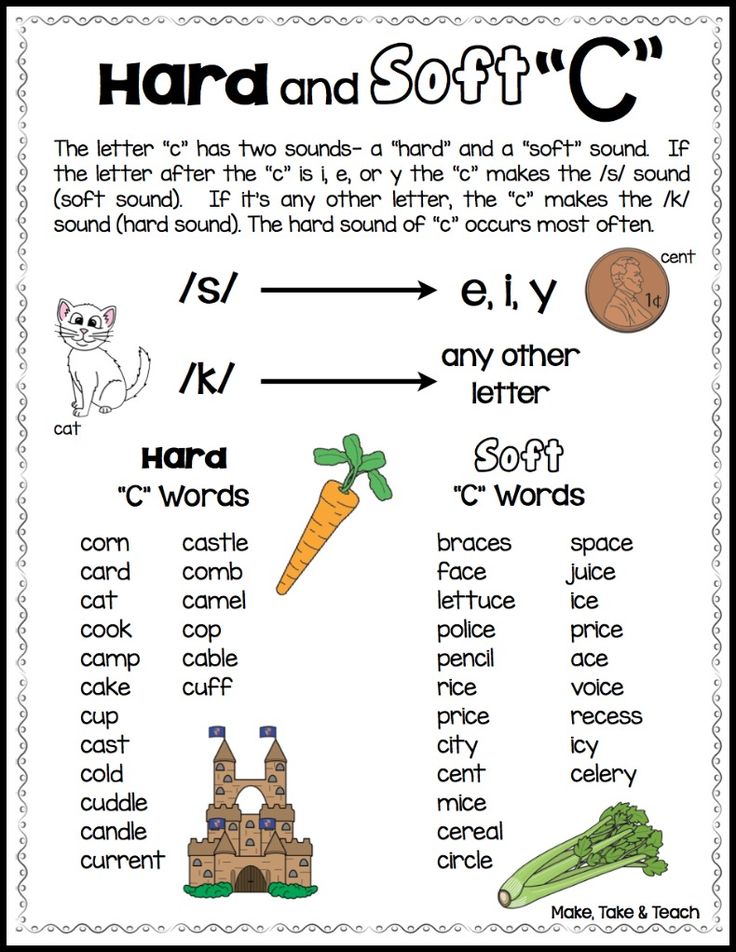

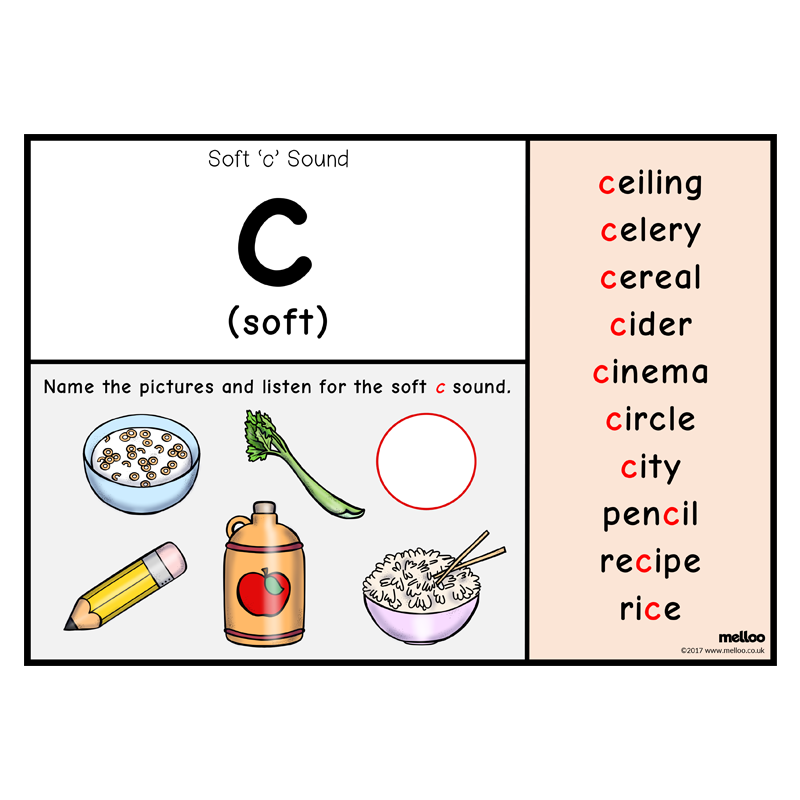

Unique sounds, like hard and soft C and G, should be taught seperate from each other. These sounds are also referred to as copycat C as /s/ and copycat C as /k/ and copycat G as /j/.

Letter X is usually found at the end of a word and may be easier to teach as an ending sound rather than beginning sound.

Letter-object association vs letter identification with letter-sound correspondence

Providing a variety of objects and visuals that begin with the focus letter increases vocabulary and understanding of the phonemes. For more advanced students, use objects with the focus letter sound at the end or in the middle and have them identify if the sound is in the middle or end of the word.

Be careful not to teach letter-object association like B is for ball. Here is an example of a more effective method of teaching letters and letter sounds while using visuals.

Point to the focus letter. “This is the letter B,” “The B says, “b” (children may say buh, but we do not emphasize the uh at the end).

“Can you say “b” too?”

Hold up the visual, the ball for this example, and ask your child to tell you what it is.

Did you say the B sound “b?”

Let’s listen carefully and say it again. “B-b-b-ball. Ball!”

“What letter sound did we hear?” “The letter B sound!”

I created letter-sound correspondence mats to help students gain confidence in identifying the letter sounds for each letter of the alphabet.

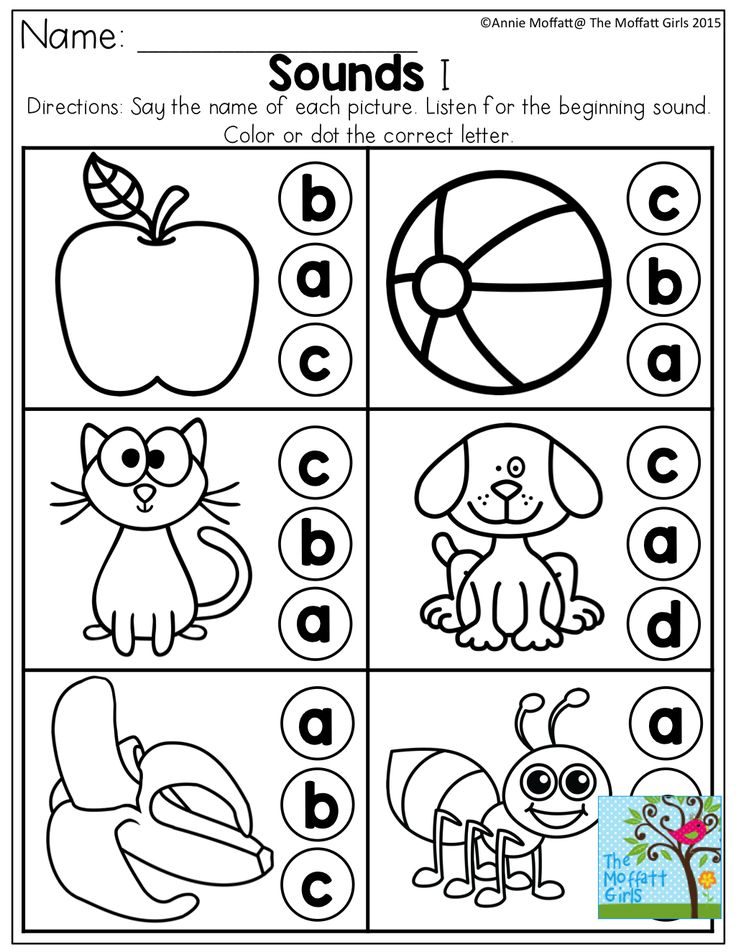

Click the picture to grab this resource! In level 1 of the letter-sound correspondence mats, students will demonstrate basic knowledge of letter-sound correspondences by producing the primary sound for each picture. All eight images on the mat begin with the focus letter-sound. In level 2, students will discriminate between pictures that begin with the focus letter-sound and those that do not.

All eight images on the mat begin with the focus letter-sound. In level 2, students will discriminate between pictures that begin with the focus letter-sound and those that do not.

Included in this resource –

There is a page for every consonant letter sound.

Vowel sounds have two sounds covered: long and short vowels A, E, I, O, and U.

The unique or tricky sounds hard and soft C and G are included seperately.

These unique letters are also listed as copycat C as /s/ and copycat C as /k/ and copycat G as /j/.

(These letters are placed at the end of the alphabet so you can choose which version of wording you want to teach before printing.)

Unique letter X is the only letter mat that focuses on the ending sound instead of the beginning sound.

Additional resources you may like

The following resources go nicely with my letter-sound correspondence mats. They focus on letter formation and letter-sounds.

| Reading teaching methods: which is better? | ||

| Anna Shevyakova Methods of teaching reading. Phonetic method. Linguistic method Whole-language method Zaitsev method Alphabet for elementary reading in English (ITA) Moore method Montessori Look-say or phonics? Is the alphabet really necessary? Is there a way to teach reading that is appropriate for all languages? Methods of teaching reading: what is better? Knowing all this, many methodologists are trying to understand the mechanisms of reading, to come up with a method by which it would be easy to learn to read. Although many parents think that how quickly and well their child learns to read does not depend on how he is taught to read, but depends on intelligence, this is actually not the case. Two independent studies in the 1960s and 1970s showed that, in general, reading ability had little to do with IQ. More recent research has shown that children who have difficulty learning to read often have above-average IQs. There is a belief that no matter how well a child learns to read by the first grade, he will learn later, over the years, difficulties in reading will come to naught. Methods of teaching reading Each of the methods invented in the 20th century, either in whole or in part, repeats well-forgotten old methods. But, as in the past, each of them is called "new", "natural", "correct" and "logical". Let's take a look at what reading programs currently exist and what results they lead to. Phonetic method. The phonetic method is subdivided into two areas: 1. Systematic-phonics are programs that systematically teach phonetics from the beginning, usually (but not always) before whole words are read . The approach is most often based on synthesis: children are taught the sounds of letters and train them to combine these sounds. Sometimes these programs also include phonetic analysis - the ability to manipulate phonemes. Not all programs that are classified as "systematic-phonics" meet these criteria. However, they all emphasize the early and serious learning of letter sounds. 2. Intrinsic-phonics are programs that emphasize visual and semantic reading and introduce phonetics later and in smaller quantities. Children enrolled in these programs learn the sounds of letters as they analyze familiar words. Another way of identifying words (by context or pattern) in these programs is given more attention than the analysis of the word. Usually there is no set time period for practicing phonetics. The effectiveness of this method in terms of the main parameters is lower than that of the method of systematic phonetics. Various researchers have found a correlation between knowledge of letters and sounds and the ability to read. For both beginners and advanced readers, knowledge of letters and sensitivity to phonetic structure (the ability to distinguish phonemes) from spoken language is a good predictor of future reading success, even better than, for example, IQ level. Even for people who have long learned to read and read, but have difficulty reading, these difficulties are often associated with insufficient knowledge of letter-sound correspondences. Linguistic method Look-say The method of "whole words" is that children are taught to recognize words as whole units, and do not explain the letter-sound relationships. In Russia, this method is known as the Doman method - Glenn Doman builds all reading instruction only on it. This method was very popular in the 1920s. After the 1930s, researchers identified serious shortcomings of this method. The whole-language method One of the goals of the whole-language approach is to make reading enjoyable. One of the characteristic features of this method is that phonetic rules do not have to be explained to learners to read. The relationship between letters and sounds is learned through the process of reading, in an implicit way. If a child reads a word incorrectly, they do not correct it. The philosophical view of this doctrine is that learning to read, as well as mastering a spoken language, is a natural process and children are able to comprehend it themselves. Zaitsev's method This technique can be attributed to phonetic methods: a warehouse is nothing more than a phoneme (with the exception of two warehouses: “b” and “b”). Thus, Zaitsev's technique teaches to read immediately by phonemes, and at the same time explains the letter-sound correspondence - not only combinations of consonants and vowels are written on the faces of the cubes, but also the letters themselves. English Primary Reading Alphabet (ITA) Moore's Method The Montessori Method Look-say or phonics? Before 1930, there were eight studies aimed at understanding whether phonetics should be taught at all. As a result of research, the need to teach phonetics became obvious. After 1930, researchers were already conducting experiments to understand how and in what quantity phonetics should be taught. An experiment was set up to compare the look-say method with the phonological method. For the experiment, we took a group of children enrolled in the first grade (5-6 years old) and still not able to read. The group was divided in half and one subgroup was taught to read using the "look-say" method, the other - using the phonological method. When the children began to read, they were tested. It turned out that in the beginning, children who were taught using the look-say method read faster and better understood what was read to themselves and read aloud fluently and with expression. In the 1980s, Seymour and Elder observed first graders learning with the whole word method. The researchers paid particular attention to what mistakes students made. In one of the tasks, children were shown cards with signed pictures and asked to read the captions to the pictures. Often children read a word that was close in meaning, but completely distant in structure. For example, "lion" instead of "tiger", "girl" instead of "children" and "wheels" instead of "car". The researchers concluded that these children paid little attention to the letter-sound relationship: the children associated the word with a certain meaning, but not always accurately. Also, children learning using the “whole words” method had great difficulty reading words in which letters are written in different scripts (RoBiN), and “phonological” children experienced great difficulty reading words in which the sequence of letters was changed (flower) or some letters are replaced with similar, but different ones (tslsvisor). It is possible that some children can learn the rules of phonics on their own, but most need explicit phonics instruction or their reading skills will suffer. This conclusion is based in part on knowing how good readers perceive a word on a page. One of the first researchers of this issue, James Cattell, showed that if people are shown words or a series of letters for a short time, then the words are perceived better. Therefore, it seems that people do not spell words. New studies have provided more precise knowledge about this phenomenon. It took longer to answer the question: “Do people who read well read the text to themselves?”. Whole-language proponents have argued for over 20 years that people often perceive the meaning of words from a text directly, without being spoken. Some psychologists still hold this view, but most of them think that reading is the process of saying a text to oneself, even for people who read well. The most convincing evidence for this last statement comes from the ingenious experiments of Guy Van Orden: when the subject is first asked, for example, "Is this a flower?", and then shown a word, for example, "lily", and asked if this word belongs to this category . Sometimes the subject was presented with a word that sounded like a suitable answer, such as "lily", and in fact the subjects often identified these words as the appropriate category, and these incorrect answers show that the reader actually transforms sequences of characters into sequences of sounds, which he then uses to understand the meaning. Recent brain research has shown that even in people who read well, the same areas of the motor cortex are activated during silent reading as when reading aloud. There are other experimental confirmations that reading is a quick pronunciation to oneself. For example, when teaching English-speaking students to read Arabic, the group that was explicitly taught letter-to-sound correspondences was much more successful at reading new words than the group that was taught using the "whole-word" method. Laboratory studies have found that the most important factor in becoming fluent in reading is the ability to recognize letters, pronunciation patterns, and whole words easily, automatically, and visually. Therefore, knowledge of letters and phonological skills is one of the most important for the development of the ability to read. From all of the above it follows that all learning must be based on a solid understanding of letters and sounds. Even a student-specific approach, one that makes reading really interesting, is less effective than phonetics cramming. Is the alphabet really necessary? A lot of research has been done and it turns out that knowledge of letters is a very good predictor of a child's rapid progress in reading. And knowing the letters is a stronger predictor than IQ. Children's ability to make letter sounds before learning to read also predicts early reading success. When children first begin to read, the correlation between knowledge of letters and/or knowledge of phonetics and their ability to read is very high. Whatever level is tested - from kindergarten to college - proficiency in letters and/or proficiency in phonetics is positively associated with reading ability (as measured by oral word recognition associated with reading aloud, reading comprehension silently, or reading speed) and, of course, with the ability to spell words. What happens if you teach children to read without teaching them the alphabet? Willows, Borwick, Haveren conducted such an experiment. They taught children to read by presenting cards with words. The children were divided into two groups: the first group was shown cards containing a picture and a word, the second group was presented with cards containing only a word. Each group was taught the same four words. When the groups learned these four words, that is, they correctly called the words from the cards, both groups were connected together. The researchers mixed word cards and showed the connected group both word cards with pictures and cards containing only words. It turned out that those children who were taught to read from cards with pictures read words better on cards with pictures and worse - the same words, but on cards without pictures, compared to those children who were taught from cards without pictures. Children who were taught to read with word cards but no pictures were better at reading words on cards without pictures than children who were taught with picture cards but were worse at reading words on picture cards. It turns out that the reverse side of the usefulness of pictures is a decrease in attention to the printed text (letters). Thus, if we see the goal in helping the child to react to an unfamiliar word (to see its image), then the pictures help, but if the goal is to draw the child’s attention directly to the spelling of the word, then the pictures interfere. So now we are ready to answer the question: Is an alphabet necessary? Answer: Yes, it is necessary. The main idea of learning the alphabet is not that children should know all the letters, but that children should pay attention to the letters. Knowing the letters and knowing their sounds helps pay attention to printed text. It is known that interest in letters in young children is positively associated with reading success. However, with age, the importance of letters and sounds for reading changes: in primary school, knowledge of letters and sounds is more important than education and good oral speech, and in high school, the level of readable texts already requires higher intellectual and linguistic abilities of the student (with good knowledge of the alphabet). Knowing the alphabet, an interest in letters, is the next step in a child's development, because the alphabet is an abstract code, unlike real objects that the child has dealt with before. The child begins to use the symbolic representation of information, which is a higher form of mental activity. It is possible that the early introduction of the alphabet will stimulate the development of abstract thinking, so necessary in our scientific automated world. Is there a way to teach reading that is appropriate for all languages? The “look-say” method is based on the fact that children are taught words as whole units, and when children have learned about 50-100 words, they are given texts in which these words often occur. It seems that this method would be best suited for teaching Chinese to read, but for the past 50 years in China, children have been taught to read words first using the Roman alphabet, and only then using Chinese characters. Similarly, children from most many other language groups are first taught the relationship between letters and the sounds associated with them (phonemes). The relationship between letters and phonemes is not very simple in languages with many exceptions, such as English. Such exception words are not read the way they are written. Reading rules depend on whether the syllable is closed or open, on the order of the letters and on their combinations with each other. The rules for reading in Russian are much simpler - words are read as they are written, the only exceptions are those words that are not read the way they are written, only because of the "laziness" of the language: unstressed letters are pronounced as it is more convenient for pronunciation, and in unstressed syllables, voiced consonants are stunned (milk -> malako, shelter -> krof) and some letters are not pronounced at all (sun -> sun). A few decades ago, a technique was popular in Russia: first to teach letters and their names, their sounds, then to merge letters into syllables and read by syllables. Often, for a long time, children could not learn the difference between the names of letters by the sounds themselves, the sound of the letters - they were knocked down by the names of the letters. In addition, the syllables are too long for initial reading, and it is difficult for the child to add letter to letter and keep it in his head to read the whole syllable. Perhaps it would be more effective to teach to read by phonemic warehouses, and not tell the child the names of letters, at least until he learns to read. There are not very many warehouses in Russian, and it is convenient to manipulate them when they are written on cubes. So, we found out that the main thing that needs to be taught to a child if we want to teach him to read well is phonetics. But the comprehension of letter-sound correspondences is most often a rather boring task, and it is not at all easy to achieve quick success in it. If you teach reading only with the help of phonetics alone, then this will most likely lead to a decrease in interest in the reading process in a child. And it is necessary to maintain interest in order not to instill in the child a rejection of reading, moreover, an interested person comprehends the subject of study several times faster than an uninterested one. However, even the youngest children can be prepared to learn to read in later years: researchers have found that the most important activity for building the knowledge and skills that reading will eventually require is reading aloud to children. There is no general methodology for learning to read in any language, but there are important elements that make up reading, and they must be mastered by anyone who wants to learn to read well. These elements turn out to be the same for all alphabetic languages - this is a sound-speech code, an alpha-sound correspondence. How to master them depends on the structure of the language in which we teach reading, but it is still necessary to teach these elements in order to make the reading process easy, enjoyable and so that the assimilation of the material read is as high as possible.

Tags: learning to read | ||

An overview of the main methods of teaching reading

Reading is a natural process for adults. But for most children, learning to read requires perseverance and effort. Adults rarely remember how difficult it was to learn to read. Pronounce the letter one after the other, keeping their sequence in mind and trying to figure out what the word is, then read the next word in the same way...

But for most children, learning to read requires perseverance and effort. Adults rarely remember how difficult it was to learn to read. Pronounce the letter one after the other, keeping their sequence in mind and trying to figure out what the word is, then read the next word in the same way...

Yes, very often a child takes a lot of effort to read even a single word, and when he reads the next, he often forgets the previous one. Try turning the text upside down and read it. How much of what you read do you remember? Is it easy and interesting to read in this way? .. But at first a child reads like upside down, he is not yet used to grasping several words at once and understanding the meaning of what he reads, so he remembers little of what he read, and therefore reading for him at first - rather some kind of fun than getting new information.

Many methodologists are busy trying to come up with a method by which it would be easy to teach a child to read fluently and grasp the meaning. Many parents want their child to learn to read quickly and well, and they think that this depends on intelligence - but in fact it is not. Ability to learn to read is little dependent on IQ. Moreover, research has shown that children who have difficulty learning to read often have an IQ above average... will come to naught. This is not true. Success in reading in the first grade is largely determined by the level of reading in the 11th grade. Good reading is all about practice, so those who are better at reading first read more overall. Thus, over the years, the difference only increases. Learning to read well in the early years helps develop an important lifelong habit of reading.

Many parents want their child to learn to read quickly and well, and they think that this depends on intelligence - but in fact it is not. Ability to learn to read is little dependent on IQ. Moreover, research has shown that children who have difficulty learning to read often have an IQ above average... will come to naught. This is not true. Success in reading in the first grade is largely determined by the level of reading in the 11th grade. Good reading is all about practice, so those who are better at reading first read more overall. Thus, over the years, the difference only increases. Learning to read well in the early years helps develop an important lifelong habit of reading.

Let's take a look at what reading programs currently exist and what results they lead to.

Phonetic method

Phonetic method is a system of learning to read, which is based on the alphabetic principle and whose central component is the teaching of relationships between letters or groups of letters and their pronunciation. It is based on teaching the pronunciation of letters and sounds (phonetics), and when the child accumulates sufficient knowledge, he proceeds first to syllables, then to whole words.

It is based on teaching the pronunciation of letters and sounds (phonetics), and when the child accumulates sufficient knowledge, he proceeds first to syllables, then to whole words.

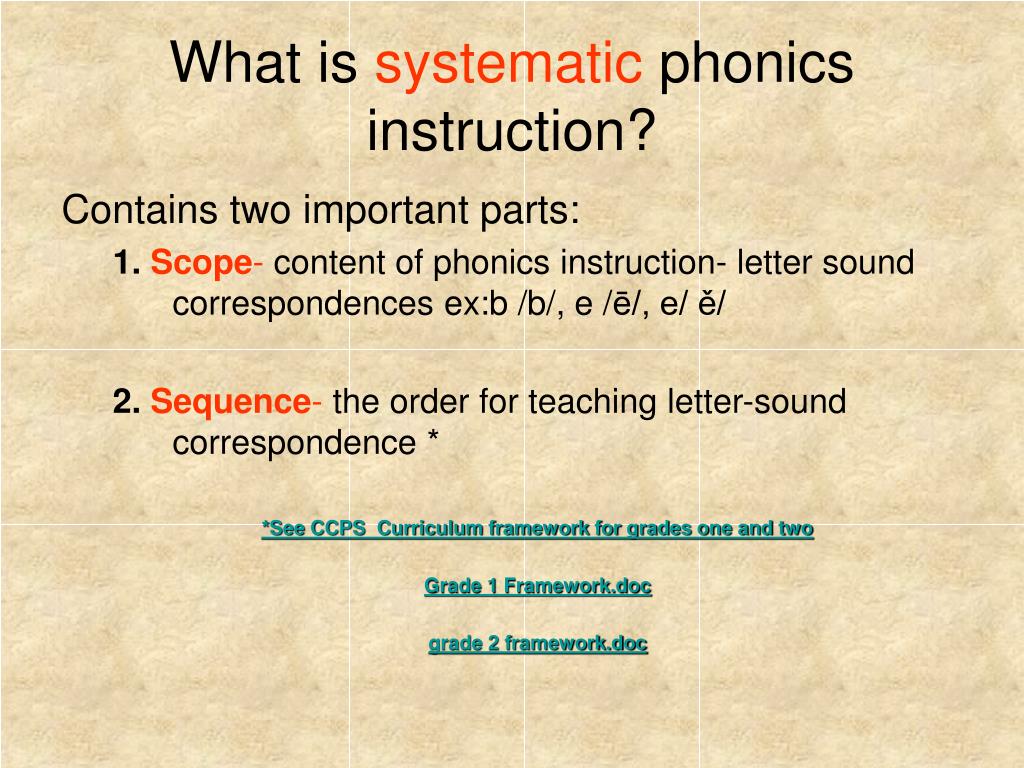

The phonetic method is divided into two branches:

- The systematic phonetics method is a program that systematically teaches phonetics from the very beginning, usually (but not always) before being allowed to read whole words. The approach is most often based on synthesis: children are taught the sounds of letters and train them to combine these sounds. Sometimes these programs also include phonetic analysis - the ability to manipulate phonemes.

- Internal phonetics method are programs that emphasize visual and semantic reading, and in which phonetics is introduced later and in less quantity. Children enrolled in these programs learn the sounds of letters as they analyze familiar words. Another way of identifying words (by context or pattern) in these programs is given more attention than the analysis of the word.

Usually there is no set time period for practicing phonetics. The effectiveness of this method in terms of the main parameters is lower than that of the method of systematic phonetics.

Usually there is no set time period for practicing phonetics. The effectiveness of this method in terms of the main parameters is lower than that of the method of systematic phonetics.

Linguistic method

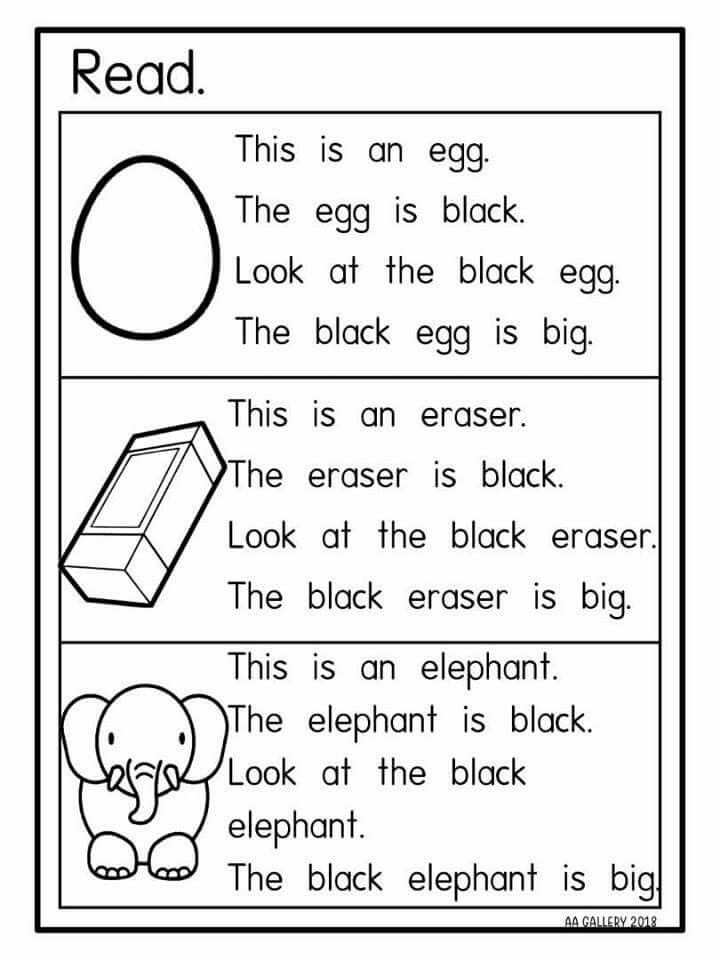

Linguistics - the science of the nature and structure of language; her observations and conclusions are used in methods of teaching reading. Children come to school already with a large vocabulary, and this method suggests teaching them to read familiar words, especially those that are used most often. First, children are encouraged to learn to read in words that are read as they are written. Reading such words, the child learns to determine the correspondence of honey with letters and sounds.

Whole word method

This method consists in teaching children to recognize words as whole units and not explaining the letter-sound relationships. Training is based on the principle of visual recognition of whole words. The child is not taught either the names of the letters or the letter-sound ratio; they show him whole words and pronounce them, that is, they teach the child to recognize words as a whole, without dividing them into letters and syllables. After the child learns 50-100 words in this way, he is given texts in which these words are often found.

After the child learns 50-100 words in this way, he is given texts in which these words are often found.

This method was very popular in the 1920s.

"whole-language" method

Somewhat similar to the whole-word method, but it relies more on the child's language experience. For example, children are given a book with a fascinating story and are asked to read it. Children read, encounter unfamiliar words, and children are encouraged to guess the meaning of these words with the help of context or illustrations, but not through the pronunciation of these words aloud. In order to stimulate a love of reading, children are encouraged to write stories.

One of the goals of the "whole-language" approach is to make the reading experience enjoyable. One of the characteristic features of this method is that phonetic rules are not explained. The relationship between letters and sounds is learned through the process of reading, in an implicit way. If a child reads words incorrectly, they do not correct him. The philosophical aspect of this teaching is that learning to read, like learning a spoken language, is a natural process and children are able to comprehend it themselves.

The philosophical aspect of this teaching is that learning to read, like learning a spoken language, is a natural process and children are able to comprehend it themselves.

Zaitsev's method

Zaitsev determined the warehouse as the unit of the language structure. A warehouse is a pair of a consonant with a vowel, or a consonant with a hard or soft sign, or one letter. Zaitsev wrote these warehouses on the faces of the cubes. He made the cubes different in color, size and sound they make. This helps children feel the difference between vowels and consonants, voiced and soft. Using these warehouses (each warehouse is on a separate face of the cube), the child begins to compose words.

This technique can be attributed to phonetic methods: a warehouse is nothing more than a phoneme (with the exception of two warehouses: "b" and "b"). Thus, Zaitsev's technique teaches to read immediately by phonemes, and at the same time explains the letter-sound correspondence - not only combinations of consonants and vowels are written on the faces of the cubes, but also the letters themselves.

mast.queensu.ca/~alexch/f_s/Txt/rev_read_meth.htm

mast.queensu.ca/~alexch/f_s/Txt/rev_read_meth.htm  Try turning this article upside down and reading it. Difficult? How much of what you read do you remember? Was it interesting to read this way? I doubt it's interesting. It is the same with a child: it is difficult to read, he remembers little of what he has read, and therefore it is not interesting to read.

Try turning this article upside down and reading it. Difficult? How much of what you read do you remember? Was it interesting to read this way? I doubt it's interesting. It is the same with a child: it is difficult to read, he remembers little of what he has read, and therefore it is not interesting to read.  This is not true. K. Stanovich showed that success in reading in the first grade largely determines the level of reading in the 11th grade. Good reading is all about practice, so those who are better at reading first tend to read more. Thus, over the years, the difference only increases. Learning to read well in the early years helps develop the important "habit" of reading for life.

This is not true. K. Stanovich showed that success in reading in the first grade largely determines the level of reading in the 11th grade. Good reading is all about practice, so those who are better at reading first tend to read more. Thus, over the years, the difference only increases. Learning to read well in the early years helps develop the important "habit" of reading for life.

However, the best phonological knowledge does not necessarily translate into a high level of reading. On the contrary, and not surprisingly, the level of reading in older people is increasingly correlated with the level of IQ.

However, the best phonological knowledge does not necessarily translate into a high level of reading. On the contrary, and not surprisingly, the level of reading in older people is increasingly correlated with the level of IQ.  Learning by this method is based on the principle of visual recognition of whole words. In this method, neither the names of the letters nor the letter-sound ratio are taught. In order to teach reading, the child was shown whole words and pronounced them, that is, they taught the child to recognize words as a whole, without dividing them into letters and syllables. After the child has learned about 50-100 words in this way, he is given texts in which these words are often found.

Learning by this method is based on the principle of visual recognition of whole words. In this method, neither the names of the letters nor the letter-sound ratio are taught. In order to teach reading, the child was shown whole words and pronounced them, that is, they taught the child to recognize words as a whole, without dividing them into letters and syllables. After the child has learned about 50-100 words in this way, he is given texts in which these words are often found.  In order to stimulate the love of reading, children are encouraged to write stories.

In order to stimulate the love of reading, children are encouraged to write stories.  Using these warehouses (each warehouse is on a separate face of the cube), the child begins to compose words.

Using these warehouses (each warehouse is on a separate face of the cube), the child begins to compose words.  Moore begins by teaching the child letters and sounds. He takes the child into a laboratory where there is a special typewriter that makes sounds or names of characters when you press them. So the child learns the names of letters and symbols (punctuation marks and numbers). The next step is for the child to be shown a series of letters or symbols on a screen, and he types them on the same typewriter, and the typewriter pronounces these series, for example, short simple words. Further, Moore asks to write, read and print words and sentences. His program also includes speaking, listening and writing from dictation.

Moore begins by teaching the child letters and sounds. He takes the child into a laboratory where there is a special typewriter that makes sounds or names of characters when you press them. So the child learns the names of letters and symbols (punctuation marks and numbers). The next step is for the child to be shown a series of letters or symbols on a screen, and he types them on the same typewriter, and the typewriter pronounces these series, for example, short simple words. Further, Moore asks to write, read and print words and sentences. His program also includes speaking, listening and writing from dictation.  These are two global and fundamentally opposite methods of teaching reading. Let's see which method is more effective for teaching reading.

These are two global and fundamentally opposite methods of teaching reading. Let's see which method is more effective for teaching reading.  Children who were taught to read using the phonological method were better at reading unfamiliar words, both at the beginning of learning and at any time thereafter. By the second grade, towards the end of learning to read, it turned out that the "phonological" children caught up and overtook their classmates and read better to themselves, better read comprehension and had a larger vocabulary than children taught to read using the "look-say" method.

Children who were taught to read using the phonological method were better at reading unfamiliar words, both at the beginning of learning and at any time thereafter. By the second grade, towards the end of learning to read, it turned out that the "phonological" children caught up and overtook their classmates and read better to themselves, better read comprehension and had a larger vocabulary than children taught to read using the "look-say" method.  For the whole year of training, the children never learned to read new words without someone's help.

For the whole year of training, the children never learned to read new words without someone's help.  For example, studies of eye movement while reading show that although people notice each letter as a separate character, they usually perceive all the letters in a word at the same time.

For example, studies of eye movement while reading show that although people notice each letter as a separate character, they usually perceive all the letters in a word at the same time.

and correspondence of letters to sounds).

and correspondence of letters to sounds).  Only the approach to learning can be common: it is now clear that any learning should be based on a solid understanding of letters and sounds, but the methods by which phonetics is given should be different for each language.

Only the approach to learning can be common: it is now clear that any learning should be based on a solid understanding of letters and sounds, but the methods by which phonetics is given should be different for each language.  For example, the letter "b" is pronounced the same as in the word "bat". And the letter “e” at the end of the word is not pronounced, but lengthens the pronunciation of the previous vowel: “pave” “save” “gave”. Thus, in English, letters can be pronounced either as they are written, or they can not be pronounced themselves, but affect the pronunciation of other letters. This is why James Pitman's ITA alphabet used to be very popular in English, and the "whole-language" method is now very popular. At the same time, the Bush administration is considering a mandatory introduction of phonetics in the curriculum in all states of America.

For example, the letter "b" is pronounced the same as in the word "bat". And the letter “e” at the end of the word is not pronounced, but lengthens the pronunciation of the previous vowel: “pave” “save” “gave”. Thus, in English, letters can be pronounced either as they are written, or they can not be pronounced themselves, but affect the pronunciation of other letters. This is why James Pitman's ITA alphabet used to be very popular in English, and the "whole-language" method is now very popular. At the same time, the Bush administration is considering a mandatory introduction of phonetics in the curriculum in all states of America.  But even if we read the words according to the rules, the way they are written, this will not be considered a mistake and the meaning of the word will not change from this, as would happen in English.

But even if we read the words according to the rules, the way they are written, this will not be considered a mistake and the meaning of the word will not change from this, as would happen in English.  In addition, the alphabet, the letter-sound correspondence is also easily acquired if taught with the help of Zaitsev's cubes - the letters themselves are written on the faces of the cubes. Due to the very structure of the Russian language, due to the fact that almost all words are read the way they are written, the warehouse principle is very well suited for teaching reading.

In addition, the alphabet, the letter-sound correspondence is also easily acquired if taught with the help of Zaitsev's cubes - the letters themselves are written on the faces of the cubes. Due to the very structure of the Russian language, due to the fact that almost all words are read the way they are written, the warehouse principle is very well suited for teaching reading.  In order for a child to believe in himself, and it would be interesting for him to learn to read, you need to give him an impulse, to show that learning to read is an exciting activity. Interest in reading will be formed only if the child achieves success fairly quickly. For example, if you teach a child to recognize several dozen words, and this can easily be achieved with a good approach, this will bring joy and self-confidence to the child, and at the same time, he can slowly but surely teach phonetics. In order to teach a child to recognize several dozen words, you can sign various objects at home, hang signs under them or on them (table, wardrobe, sofa, stove, etc.). You can also play a “guessing game”: choose a dozen words and write words from this dozen with your child, ask the child to guess what is written. Such games are usually very popular with children.

In order for a child to believe in himself, and it would be interesting for him to learn to read, you need to give him an impulse, to show that learning to read is an exciting activity. Interest in reading will be formed only if the child achieves success fairly quickly. For example, if you teach a child to recognize several dozen words, and this can easily be achieved with a good approach, this will bring joy and self-confidence to the child, and at the same time, he can slowly but surely teach phonetics. In order to teach a child to recognize several dozen words, you can sign various objects at home, hang signs under them or on them (table, wardrobe, sofa, stove, etc.). You can also play a “guessing game”: choose a dozen words and write words from this dozen with your child, ask the child to guess what is written. Such games are usually very popular with children.  The greatest progress is made when the vocabulary and syntax of what is being read is always slightly higher than the child's own language level. To test this hypothesis, fifteen parents were selected, who were taught how to read correctly to children: actively involve the child in reading. During the reading, parents were asked to ask questions not for “yes or no”, but for more detailed answers. They were asked to pause more often, to leave unfinished thoughts, after listening to the child's answer, to offer alternative answers, to ask more and more difficult questions. After teaching the parents, they were asked to read to the child in this way for a month and record these readings on a tape recorder. At the same time, fifteen untrained parents were selected whose children were the same age as the children in the first group. They were also asked to tape their readings. A month later, both children were tested, and it turned out that children whose parents were trained surpassed their peers by 8.

The greatest progress is made when the vocabulary and syntax of what is being read is always slightly higher than the child's own language level. To test this hypothesis, fifteen parents were selected, who were taught how to read correctly to children: actively involve the child in reading. During the reading, parents were asked to ask questions not for “yes or no”, but for more detailed answers. They were asked to pause more often, to leave unfinished thoughts, after listening to the child's answer, to offer alternative answers, to ask more and more difficult questions. After teaching the parents, they were asked to read to the child in this way for a month and record these readings on a tape recorder. At the same time, fifteen untrained parents were selected whose children were the same age as the children in the first group. They were also asked to tape their readings. A month later, both children were tested, and it turned out that children whose parents were trained surpassed their peers by 8. 5 months on both the verbal expression of thoughts and the vocabulary test - and this is a huge difference for children of 30 months of age .

5 months on both the verbal expression of thoughts and the vocabulary test - and this is a huge difference for children of 30 months of age .