How to write kids

8 Necessary Tips for How to Write Child Characters

With their alluring mix of innocence, alertness, selfishness, and idealism, child characters can create all kinds of interesting opportunities for irony, symbolism, character identification, and humor. But figuring out how to write child characters is territory fraught with potential pitfalls.

This topic has been on my mind a lot these last few years, since both my recently published dieselpunk Storming and my upcoming historical superhero tale Wayfarer feature prominent roles filled by eight-year-old kids. In writing these characters, my goal as been simple: avoid the following bad example, which is permanently and regrettably imprinted in my brain.

I can’t remember the name of the book (which is probably just as well), but I still cringe every time I think of its opening paragraph: a cutesie little girl cozying up to a stranger, with an, “Ah gee, mister.”

All too often, this is how we’re tempted to write our child characters. But, please, resist the temptation. Not only are these sorts of children 2D caricatures, they’re also a wasted opportunity. Wielded with power and understanding, your child characters can transform your fiction.

Consider the following eight dos and don’ts of how to write child characters.

4 Don’ts of How to Write Child Characters

1. Don’t Make Your Child Characters CutesyThere’s only one Shirley Temple–and I sincerely doubt her “ohmiword” would have been as cute when conveyed on the stark black and white of a novel’s page. If your child characters are going to be cute, they must be cute naturally through the force of their personality, not because the entire purpose of their existence is to be adorable. Forced cutsiness rarely works any better than forced humor.

2. Don’t Make Your Child Characters Sagely Wise“Out of the mouths of babes” may have its moments of truth. But–with the rare and organic exception–don’t turn your child characters into little fonts of wisdom. It’s true kids have the benefit of seeing some situations a little more objectively than adults. But when they start calmly and unwittingly spouting all the answers, the results often seem more clichéd and convenient than impressive or ironic.

It’s true kids have the benefit of seeing some situations a little more objectively than adults. But when they start calmly and unwittingly spouting all the answers, the results often seem more clichéd and convenient than impressive or ironic.

Don’t confuse a child’s lack of experience with lack of intelligence. Don’t have your child characters offer wide-eyed “I dunnos” or stand around with a finger in their mouths and a blank expression on their faces. It’s fine if they don’t know what’s going on, but don’t forget for a minute that their brains are whirring behind the scenes, trying to figure it all out.

4. Don’t Have Your Child Characters Use Baby TalkIn writing child characters, the same rules apply to their dialogue as to the use of any kind of dialect: don’t abuse it. Don’t spell out their lisp. Don’t make a habit of letting them misuse words. And, at all expenses, avoid “ah, gee, misters. ”

”

4 Do’s of How to Write Child Characters

1. Write Your Child Characters as Unique IndividualsDon’t ever put a “child character” into your story–anymore than you would “an American character” or “a female character.” Create a fully realized individual who has a reason for existing beyond mere accessorizing.

Adults often tend to lump all children into a single category: cute, small, loud, and occasionally annoying. Look beyond the stereotype. Remember yourself at the age of your child character? Remember how smart, determined, curious, and individualistic you were? A trick I like to employ to get myself back into the child mindset is to look at photos and videos of myself at the correct age.

2. Give Your Child Characters Personal GoalsThe single ingredient that transforms someone from a static character to a dynamic character is a

goal. It can be easy to forget kids have goals, because when we think of goals, our adult brains tend to think of lofty things like earning a million dollars, finding true love, or saving the planet. In fact, however, kids are arguably even more defined by their goals than are adults. Kids want something every waking minute. Their entire existence is wrapped up in wanting something and figuring out how to get it.

In fact, however, kids are arguably even more defined by their goals than are adults. Kids want something every waking minute. Their entire existence is wrapped up in wanting something and figuring out how to get it.

Consider Harper Lee’s enduring Jem and Scout Finch and their determination to lure their reclusive neighbor Boo Radley out of his house so they can see him. If I had to pick one single reason why How to Kill a Mockingbird is so enduringly beloved, I wouldn’t choose its powerful themes. I would instead point to Scout Finch’s passionate desire for something or other on every single page. This, all by itself, is what makes her such a fascinating and dynamic character.

3. Make Your Child Characters SmartI look at my two-year-old niece and I see a brain every bit as intelligent as my own looking back at me out of those big brown eyes. She may not know as much as I do, but that doesn’t mean she isn’t as smart.

Now, of course, you don’t have to go out and write a bunch of little Einsteins. But don’t make your child characters “dumb on purpose.” In Wayfarer, I had a blast writing the relationship between my twenty-year-old country boy protagonist and his eight-year-old street-savvy sidekick Rose. Their different lifestyles and educations placed them on basically level ground, despite their age differences–which created all kinds of interesting story scenarios.

Kinda like Dickens’ ever-epic Artful Dodger:

4. Don’t Forget Your Characters Are ChildrenMost of the pitfalls in how to write child characters have to do with making them too simplistic and childish. But don’t fall into the opposite trap either: don’t create child characters who are essentially adults in little bodies.

One of my favorite passages of all time is from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Men, in which the little boys ruin the little girls’ tea party. One of the boys, banished from the room, lies down on the floor to listen under the door as the girls are comforted by being told the boys are surely sorry, to which this particular miscreant bawls, “I ain’t!”

One of the boys, banished from the room, lies down on the floor to listen under the door as the girls are comforted by being told the boys are surely sorry, to which this particular miscreant bawls, “I ain’t!”

Perfection.

The beautiful dichotomies of childhood offer so many wonderful opportunities for creating subtext and irony within fiction. Use them wisely and with as much insight and understanding as you’d apply to any of your adult characters. The result may be one of the most powerful characters you’ll ever write.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever written a child character? What was your chief concern in how to write child characters? Tell me in the comments?A Guide to Writing Child Characters Authentically – All Write Alright

Annoying children are unfortunately overly prevalent in literature and media. It’s not that writers deliberately create these characters to be annoying, but they end up that way when they aren’t given the same amount of backstory and personality as the adults in the story. Child characters deserve to have just as much care and development as any other character, and if you don’t give that to them, then they will feel less authentic. And when your characters are bad, your entire story suffers.

Child characters deserve to have just as much care and development as any other character, and if you don’t give that to them, then they will feel less authentic. And when your characters are bad, your entire story suffers.

Alternatively, children in stories can come across as unrealistically mature for their age. Writers often use the excuses “he had to grow up fast” or “she’s gifted” to justify their young characters acting like adults, but realistically, that wouldn’t happen. Unless there’s magic involved somehow (even that’s a cheap excuse), your child characters should act like, well, children.

Although it can be frustrating to try to get right, you can learn how to create complex young characters with enough research and practice. You just need to have the patience to understand a different mindset.

Children are Individuals

This should be obvious, but children are unique individuals with different passions, goals, and personalities. Despite this, writers often pick one of a few worn-in personality tropes to assign to their child character, then simply call it a day. I’m sorry to be the one to tell you this, but that’s just not going to cut it. If you want your young characters to feel like real people, you’ll need to put more work in than that.

I’m sorry to be the one to tell you this, but that’s just not going to cut it. If you want your young characters to feel like real people, you’ll need to put more work in than that.

When designing a child character, you should go through the same process that you would for any other kind of character. You need to give them quirks, flaws, motivations, and backstory just like anyone else. That doesn’t mean that they should already know exactly what they want to be, but they need to show some level of personality. With that being said, motivations and desires are often much more short-lived for children. For example, they could be wholly obsessed with getting to play with a certain toy, or getting to explore a cool and fun new place. To a child, those desires could be a very big deal.

Obviously, a particularly young child might not have a lot of backstory just yet, but you should have a pretty clear understanding of how they were raised, and any particularly notable events that happened earlier in their life. Did they have any health problems? Did they develop any irrational fears of their closet, or under their bed? Were they raised by their parents, or someone else? Having even a basic understanding of their past can give you more inspiration for developing their character. A child who was neglected might be more trusting of strangers or clingier to those that pay attention to them, while a child who was spoiled might act more entitled and bratty.

Did they have any health problems? Did they develop any irrational fears of their closet, or under their bed? Were they raised by their parents, or someone else? Having even a basic understanding of their past can give you more inspiration for developing their character. A child who was neglected might be more trusting of strangers or clingier to those that pay attention to them, while a child who was spoiled might act more entitled and bratty.

Unless the plot revolves around these children, chances are they aren’t going to be one of your main characters. If you want some tips for adding supplementary characters into your story, check out my post “How to Write Minor Characters.”

How Children Learn

Children learn how to behave as a result of what they are exposed to. They learn how to act based on how the people around them act, and they learn to speak by repeating the words they hear other people saying. Children are like little sponges that absorb whatever information they come across, so you can assume a lot about a child based on who their role models are. The people that are around often, or that your child character looks up to, are going to have a much stronger influence on them than anything else.

The people that are around often, or that your child character looks up to, are going to have a much stronger influence on them than anything else.

In addition to witnessing things in their environment, children often learn by experimenting themselves. They learn what is right and wrong by doing something and observing others for their reactions. They learn that making a mess is bad because it upsets other people, while gently petting the family cat makes other people happy. Children are born with natural instincts that allow them to interpret expressions and emotions, which helps them to make sense of the world from an early age. However, they are just as likely to learn from making a mistake when no one else is around to give them positive or negative signals.

No two children learn exactly the same way, or with the same amount of family involvement or structure. Try to consider how a child would develop differently if they learned the same life lesson, such as “don’t touch the hot tea kettle,” but in different ways. One child learns because they are scolded, but the other child touches the kettle and learns by experiencing the heat for themself. How would those two situations influence those children in different ways? How could their overall approach to learning (and their parents’ approach to teaching) shape them as they grow up?

One child learns because they are scolded, but the other child touches the kettle and learns by experiencing the heat for themself. How would those two situations influence those children in different ways? How could their overall approach to learning (and their parents’ approach to teaching) shape them as they grow up?

Writing Toddler Characters (1-4)

This is a particularly difficult age group for people to write about, and toddlers in stories often resemble more of an object than a person. Writers tend to shy away from giving toddlers any real personality, out of fear of conveying them unrealistically. This strategy, however, only produces boring children that end up being more like plot devices than actual characters. To be able to portray these characters accurately, you need to understand how people think, speak, and behave at this age.

How Toddlers Think

Toddlers are just beginning their experiences in the crazy, overwhelming world we live in. There’s so much to see and do that toddlers experience something new every single day. Imagine the wonder, confusion, and fear that could evoke—I would need a nap every few hours too if I had to face the unknown like that.

Imagine the wonder, confusion, and fear that could evoke—I would need a nap every few hours too if I had to face the unknown like that.

Toddlers have a particular way of interpreting their surroundings that is based purely on objective, observable truth. They will believe that something exists because they can see, feel, or hear it. They believe that something behaves a certain way because they have witnessed its behavior. A dog is soft because they can touch it and feel its soft fur.

Along that line, toddlers do not yet understand that other people have thoughts and feelings too, so they often approach interactions with a relatively self-centered perspective. As they grow, they will begin to understand empathy, but until then, they will believe that the world revolves around them.

How Toddlers Speak

Writing dialogue for toddlers is the part where most writers fumble. A reader doesn’t need to know the inner workings of your child character’s thoughts, but the moment that kid opens their mouth, they had better have some convincing dialogue.

There is a common misconception that toddlers will use only simple words and phrases to communicate. That’s a pretty narrow perspective, and it only works if you assume that all children are little clones that are all raised in the same, perfect environment. In reality, children will repeat the words that they hear other people using. If they go to a public preschool, then they might develop a pretty standard vocabulary of simple words. But if their parents curse, then the child is likely to curse as well.

With that said, that doesn’t mean that the child will always pronounce more complicated words correctly, and they might not use the right words in the proper contexts. Children also often have favorite words that use as frequently as possible in conversation. That could be a fun thing to experiment with in your story, but don’t change up the spelling of words to emphasize their mispronunciation. That can quickly get out of hand, and can be either confusing or frustrating for your readers.

Young children are also likely to ask many questions. As they learn how to speak, it is not uncommon for children to constantly spout the word “why?” When in doubt, have a child ask questions to illuminate the way they are thinking about the world, and you could reveal a lot about their personality. For example, a child that is constantly asking questions about how the world works, such as “how do birds fly?” or “why is the sky blue?” could be perceived as more precocious. However, a child that asks questions like “do bugs have families?” or “are dragons real?” reveals a more creative mindset.

How Toddlers Behave

For the first few years of a child’s life, they lack the context to understand exactly what behavior is appropriate in different situations. To get around this, young children often imitate the behavior of those around them. If they aren’t familiar with a particular situation, place, or person, they often look to trusted adults to try to figure out how they should behave. If their mother, for example, seems relaxed and happy, the child is more likely to approach a situation with curiosity and glee. If their mother is tense or angry, the child is likely to get scared and behave defensively.

If their mother, for example, seems relaxed and happy, the child is more likely to approach a situation with curiosity and glee. If their mother is tense or angry, the child is likely to get scared and behave defensively.

When there is no one to imitate, children rely on their natural instincts to navigate unfamiliar situations. A child will instinctively avoid another person that looks frightening, angry, or unfamiliar. One of the ways a child makes these determinations is by association. If a stranger has the same skin color, hair color, and stature as one of their parents, then they will be more likely to assume they are trustworthy. Likewise, if a location or event reminds them of an unpleasant experience, then they will assume that it will also be unpleasant. If you aren’t sure how to make your child character react to something, try to find connections to things they have already experienced, and what that experience was like for them.

In familiar settings, toddlers will remember how they behaved previously, and behave as a result of the consequences they experienced. If they got in trouble for pushing another child down, they probably wouldn’t try something like that again—at least if an adult is nearby. Remember that a child’s behavior is all about making connections to things and learning about the consequences of their actions.

If they got in trouble for pushing another child down, they probably wouldn’t try something like that again—at least if an adult is nearby. Remember that a child’s behavior is all about making connections to things and learning about the consequences of their actions.

Writing Child Characters (5-8)

Once a child outgrows the toddler phase, they will start displaying more critical thought and preferences. They might have a favorite show, a favorite genre of music, and a favorite pastime, and all of those reveals a little bit more about the person they are shaping up to be. They are really starting to get the hang of being alive, so you can experiment more with how they interact with people and engage with their surroundings.

How Children Think

At this age, children have learned enough about the world to where they can start making their own judgments. They can tell now when a person is acting suspiciously, or when an animal poses a threat to their safety. They can form their own opinions, and they can approach new situations with more confidence.

However, children at this age are still impressionable. Although they exhibit more free thought and preference, they still tend to trust in the beliefs that their parents or peers instill in them. If their classmates insist it is cool to curse or act tough, then that belief will probably stick with them. Alternatively, if they have been raised in a certain religion, they likely won’t question it. After all, why would their parents lie to them?

At this age, children still often have trouble separating reality from superstition. They might believe in mythical figures like Santa Claus, or the Easter Bunny, and they might be afraid of monsters under their bed. It is not unlikely for a child to have an imaginary friend, too.

How Children Speak

At this stage, children have learned the basic mechanics of speech, and communicate in complete sentences. They will also often crack jokes, ask questions, and tell stories. However, topics that are more conceptual or theoretical will still go over their heads, and it is important to remember that there will still be words and phrases that they do not understand. Additionally, children do not generally speak in overly complex sentences.

Additionally, children do not generally speak in overly complex sentences.

Children at this age will begin vocalizing more of their opinions, and they might try to challenge their parents’ suggestions and rules. If their parents ask them to do something, they are more likely to argue or negotiate, rather than throwing a tantrum—but of course, they likely haven’t completely outgrown this reaction yet. Children can still throw tantrums, but your characters may come across as too immature if that happens too often at this age.

Children can often be funnier or wittier than adults, and they might know newer slang. They could use terms from a television show or video game, and they might repeat idioms and figures of speech without actually understanding what they mean. You can tell a lot about a child’s personality based on what they say, so craft their dialogue carefully.

How Children Behave

This age is a particularly difficult one to convey, since there are many ways that children are still similar, and many ways they deviate from each other. Children develop at different rates, so one child might have learned incredible patience and restraint at this age, while other children may throw tantrums and fight. In some ways, it gives you the freedom to really craft them into little individuals. In other ways, however, it can feel like too much freedom to mess up.

Children develop at different rates, so one child might have learned incredible patience and restraint at this age, while other children may throw tantrums and fight. In some ways, it gives you the freedom to really craft them into little individuals. In other ways, however, it can feel like too much freedom to mess up.

Children really start to come out of their shells around this age. They will have favorite subjects in school, hobbies, and they might even start displaying real skills in sports or music. They will start to find new ways to spend their free time, like reading, climbing trees, playing video games, or socializing, and those activities will influence the ways they continue to learn. Just try to remember that they are still young, and they have a lot they still need to learn about the world.

Writing Preteen Characters (9-12)

This is often a difficult time in people’s lives. Middle School is tough, and it can pose many complex challenges to people who are still figuring themselves out. It is an awkward transition, where they are not quite teenagers, but they feel too old to be considered children. They are expected to find things they are good at and figure out what they want to do with their lives, and some preteens let that pressure bring them down. When so much of their identity is based around what they almost are, that can lead many kids to either resent or eagerly await what the future has in store for them.

It is an awkward transition, where they are not quite teenagers, but they feel too old to be considered children. They are expected to find things they are good at and figure out what they want to do with their lives, and some preteens let that pressure bring them down. When so much of their identity is based around what they almost are, that can lead many kids to either resent or eagerly await what the future has in store for them.

How Preteens Think

There are a few things that define the mind of a preteen child. For one thing, many children that are approaching their teen years strive to distance themselves from their younger peers. They aren’t like them, they’re older. This can lead them to act overly confident (“I can do that!”) and independent (“I don’t need your help, mom!”). They may try to engage in more adult activities in order to convince those around them that they are more mature. However, if they get hurt or scared, they will probably still seek comfort from a trusted adult.

The middle school years are also a notoriously hormonal time, and that is likely going to result in stronger emotional reactions to situations. Minor problems would get blown way out of proportion, and everything is going to seem like a bigger deal than it is. This is further exacerbated by the fact that adults “just don’t get it.”

It is not uncommon for children around this age to start having angry outbursts. For more information, check out my article “Writing a Character with Anger Issues.”

However, at this point, your character really would be beginning to mature. They would have a much more confident stance on a variety of topics, and they begin to formulate beliefs that contradict what their parents taught them. By this time, they would have the ability to think for themself and determine what is right and wrong on their own—and those determinations could end up being completely perpendicular to their parents’ beliefs.

How Preteens Speak

Dialogue for preteens is going to start resembling the way adults speak since they will have a much stronger grasp of language and conversation. However, although they understand the conventions of language, they aren’t going to walk around speaking like little scholars. More than likely, they will try to communicate the same way as their peers, and what they determine to be cool. That could mean constantly spewing inside jokes, online references, or profanity, but most preteens have the sense to speak in different ways depending on their company.

However, although they understand the conventions of language, they aren’t going to walk around speaking like little scholars. More than likely, they will try to communicate the same way as their peers, and what they determine to be cool. That could mean constantly spewing inside jokes, online references, or profanity, but most preteens have the sense to speak in different ways depending on their company.

It’s also pretty common for preteens to have obsessions with something, such as a specific television show, aesthetic, game, or sport, and they are likely to gush about it often. These obsessions are often short-lived, but they can occupy a large space in your character’s mind, so they would naturally want to talk about what is important to them at any given moment.

How Preteens Behave

Around this age, children are going to begin to think romantically. They might develop crushes on their classmates, and they can become rather absorbed in the business of dating. They could also become interested in experimenting with their sexuality, something that can all too often result in familial disapproval. However, that is a necessary—though often difficult—part of learning about themself.

However, that is a necessary—though often difficult—part of learning about themself.

In an attempt to figure out who they are and who they want to be, it is not uncommon for children to go through relatively short phases. As silly as it might sound, children around this age frequently experiment with phases such as gothic or rebellious, and they may engage in trends like dying their hair and dressing in the latest fashions. They may also choose to stop (or start) going to church, sneak out of the house at night, or skip school.

Writing Teenage Characters (13-18)

Writers often mistakenly write teenagers like they are fully developed and experienced adults. However, like when adult actors play teenagers in a movie, this comes across as inauthentic and strange. Teenagers are intelligent and grown, but they are not yet like adults. There are many things that they still don’t fully understand, and they are not as emotionally developed as adults. They still have a lot to learn about the world.

However, teenagers are stuck in a strange position. They are quickly approaching adulthood, but they are almost always still treated like clueless children. Teenagers rarely get the respect they should, and that often plays a large part in how they view adults.

How Teenagers Think

Teenagers have a lot to deal with, and many of them still require a certain degree of emotional support—that they often don’t receive. They do not yet know how to cope with things in a healthy way, and they might make poor choices that could lead them down a bad road. Teenagers still require a lot of support and guidance from the adults in their lives, even if that is difficult for them to admit.

Teenagers face a lot of pressure. They are expected to make huge decisions about their future, and making mistakes now could determine the outcome of their life. That can be terrifying, and they might respond by buckling under the pressure or adopting a nihilistic attitude. Of course, that depends on the person; some could flourish under the pressure and find success. But the point is, no matter what your character is like, they’re likely going to be going through a lot at this age, and you shouldn’t make the mistake of taking that lightly.

But the point is, no matter what your character is like, they’re likely going to be going through a lot at this age, and you shouldn’t make the mistake of taking that lightly.

How Teenagers Speak

Writing dialogue for teenagers is probably the easiest part since most of them will speak in a manner that’s almost exactly like an adult. They might occasionally say something immature or behave in a socially unacceptable manner, but for the most part, you wouldn’t have to think too hard about the way you write their speech.

Some writers lean on old tropes to emphasize the age of their character, but that’s (like) a bad idea (y’know?). For the most part, these stereotypes are old and inaccurate, and they’re only going to make you unpopular among your younger readers. Take your teenage characters seriously, and never reduce any of your characters to a predictable trope.

How Teenagers Behave

People often look back on their teenage years as when they were “young and dumb,” so don’t assume that your teenage characters should always make the best decisions. They still have a lot to learn, and many teens won’t consider all the consequences of a bad idea—like skipping class, sneaking out, or getting drunk.

They still have a lot to learn, and many teens won’t consider all the consequences of a bad idea—like skipping class, sneaking out, or getting drunk.

With that said, teenagers are often faced with situations where they need to act more mature, such as a job interview. At the same time, they may still get in trouble with their friends and go to parties. They will often balance these two sides of their life for some time, keeping a certain amount of playfulness in the way they live day-to-day.

If you want some inspiration for giving your teenage characters some “young and dumb” flaws, take a look at my other article “How to Create Complex Flaws for Characters.”

Draw Inspiration from your Own Experiences

If you still need inspiration, try looking at your own past. You were a child once, like everyone else. Try to remember all the stupid things you did, and why you did them. Think about what you liked, and the phases you went through. Additionally, remember the children you played with, your siblings, and any other child you interacted with growing up. What were they like? What games did you play together? For the most authentic characters, don’t be afraid to base them off of children you remember growing up.

What were they like? What games did you play together? For the most authentic characters, don’t be afraid to base them off of children you remember growing up.

Thankfully, there are still children everywhere, so you can simply go outside if you can’t find any useful memories from your childhood. Take note of how children behave in grocery stores and parks, and don’t be afraid of sparking up a conversation with the parents. Chances are, they’ll start talking about the silly things their children do without much prompting, but you could always take an honest approach and tell them you’re working on writing a story.

If you know other people with kids, or if you have children, nieces, or nephews, simply spend more time with them and consider which aspects of their behavior you would want to incorporate into your own characters. Another option is to speak with your own parents about how you, and your siblings if you have any, behaved when you were younger. They will likely appreciate the opportunity to reminisce, and you could get some more information on stages of your life that you wouldn’t remember as well.

However you decide to gather information, you should try to learn from your surroundings, otherwise, your understanding of a child’s behavior will be purely conceptual.

Good luck with creating compelling young characters for your story!

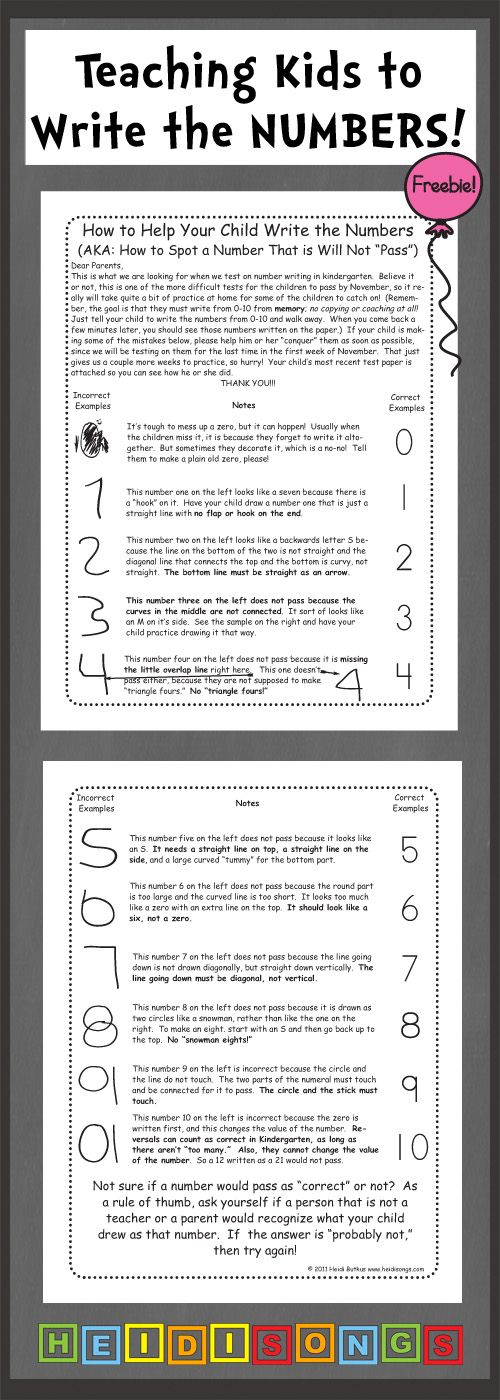

How to teach a child to write beautifully and quickly

Most parents take the initiative in early learning. They strive to teach the child how to hold a pen correctly, write letters in calligraphic handwriting and understand numbers as early as possible. On the eve of entering school, parents also think about how to teach their child to write, and also where to start.

Prostock-studio/Shutterstock.com

Content:

- Who should teach writing: parents or teachers?

- Recommendations in the preparation of the educational process

- How to teach a child to write - stages and teaching methods

- Preparation

- Writing practice

- How to choose prescription?

- How to teach a child to write if he is left-handed?

Who should teach writing: parents or teachers?

Prostock-studio/Shutterstock. com

com

Educational institutions must admit all children aged 6.5-8 years old to 1st grade, regardless of the presence or absence of useful skills. According to paragraph 3 of Art. 5 of the Federal Law No. 273, school education is publicly available to everyone and does not require admission on a competitive basis. Children are not required to be able to read or write, but if parents teach them this at an early age, it will be much easier for them to adapt to the educational process after entering school.

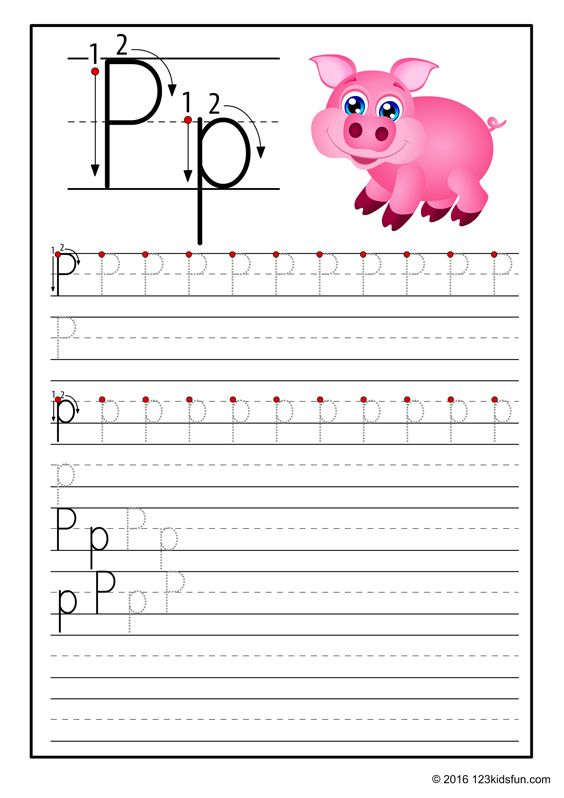

Home teaching of writing is carried out in several stages. Preparing for admission to school begins at the senior preschool age - 5-7 years. Before that, writing letters and numbers does not make sense. Three-year-olds can tell text from drawings, even if they haven't heard about reading and writing. Despite this, you need to start the first lessons no earlier than 4-5 years . Three-year-olds can draw, sculpt from plasticine, cut out various shapes from colored paper or cardboard. During this period, teach your child exercises for fine motor skills of the hands. Thanks to regular exercises, his hand will get stronger and coordination of movements will improve.

During this period, teach your child exercises for fine motor skills of the hands. Thanks to regular exercises, his hand will get stronger and coordination of movements will improve.

After the age of 4, teach your child to draw simple geometric shapes. By writing circles, ovals, even and rounded lines, hooks on a notebook sheet, the child will begin to get used to the pen, the ability to hold his back and behavior at the table.

During the lesson, do not press on the baby - do writing playfully. The game form will cause genuine interest in a new business, in contrast to the edification of a strict teacher. After a year of regular classes, it will be possible to move on to learning to write in print, and then in capital letters.

The given age for training is indicative. What time to start teaching your child to write is up to you. To check whether he is ready for classes or not, invite your child to draw some shapes or ask him to paint over the drawing. If he does not cope well with the line and does not orient himself on paper, then it is too early.

Wait until the baby becomes more assiduous and psychologically ready to perceive new information. During this time, read for yourself about the game approach to learning and writing techniques, so that by the time of teaching you will be fully equipped. If it is incorrect to explain the spelling of numbers or letters, the child will have to relearn at school.

Recommendations for the preparation of the educational process

Prostock-studio/Shutterstock.com

Seating a fidget at the table is not a task for the faint of heart. In order to instill perseverance in a child and not discourage the desire to study, take into account his psychotype and make it a rule to engage in writing in a playful way. Instead of an hour-long tedium, spend short, but daily classes. 15 minutes is more than enough to get started. The kid will be able to draw lines on paper if he has well-developed arm muscles and their work is coordinated.

5 "never" that will make life easier for your children:

- Never neglect the development of fine motor skills, which improves coordination, speech, thinking, imagination, memory, attention.

- Never force a child to continue an exercise if he fails. Take a break and go back to easier tasks for a while.

- Never buy a beautiful pen instead of a comfortable one. Choose handles with a rounded stem. They should write softly, and their ink should smoothly come out of the rod, leaving no blots or gaps on the paper.

- Never rush your baby. First-graders continuously write for 5-10 minutes in 1 approach, so there is no need to require a preschooler to write faster. Instead of writing numbers and letters, children can hatch, draw, draw lines through the printed labyrinths - do everything that is indirectly related to writing or directly prepares for it.

- Never deviate from the intended goal. Drive away the thought that you got the most difficult child in the universe. Parents who did not have the patience to quit what they started halfway, deciding that teachers will teach how to write letters quickly and beautifully. Over time, students will master the letter, but at first they may lag behind their peers, learn new information poorly and not show interest in learning at all.

Spend time developing skills that are inherent in ages 3, 4 and 5. According to the director of the Institute of Developmental Physiology of the Russian Academy of Education Maryana Bezrukikh, 40-60% of today's first-graders are not ready for learning. At an early age, they went through all the "charms" of parental tests in pedagogy. The desire to teach a child early to write, read, count and speak a foreign language is commendable, but fraught with consequences. When they come to school, children do not show interest in learning and do not speak well. According to her, they may not be able to read or write before school, but they must have well-formed speech, developed attention, thinking and memory.

When sending your child to school, take care not only of his readiness, but also of his safety. Purchase a children's GPS watch or install the Find My Kids app on your phone. With this kit, you can check how your child is adapting, whether they are being bullied at school. And if a young student goes to school on his own, you can see which route he takes (and evaluate his safety) and where he is at the moment.

And if a young student goes to school on his own, you can see which route he takes (and evaluate his safety) and where he is at the moment.

How to teach a child to write - stages and methods of teaching

Prostock-studio/Shutterstock.com

Writing is taught in two stages: preparation and practice. The preparatory stage lasts from 3 to 5 years, and the practice begins after 5 and continues at school.

Preparation

Before picking up a pen, children must learn to:

- manipulate small objects by using scissors, felt-tip pens, plasticine, mosaics;

- keep your posture and sit properly at the table. Show with your own example what the correct position of the back at the table looks like. The back should be kept straight and the shoulders at the same level. Tilt your head slightly forward and keep it above the table no lower than 30-35 cm. Pay attention that the chest does not touch the tabletop, the legs are on the floor and bent at a right angle.

Hands should lie on the table, and the elbows slightly protrude beyond its edge. Make comments if the child slouches at the table;

Hands should lie on the table, and the elbows slightly protrude beyond its edge. Make comments if the child slouches at the table; - to use a pencil. Buy trihedral pencils - it is easier to explain on them how to properly place your fingers and hold them with your hand. After them, you can switch to ordinary round pencils for drawing, and then to pens;

- to navigate on paper. Develop spatial thinking by talking about the position from the edge, center and different sides of the sheet. Speak each movement, specifying that you put the pen on the left or right, move closer to the center or to the bottom of the sheet;

- distinguish letters and know the alphabet. They move on to writing after they learn the alphabet and learn to read. To transfer letters to paper, the child must imagine their image.

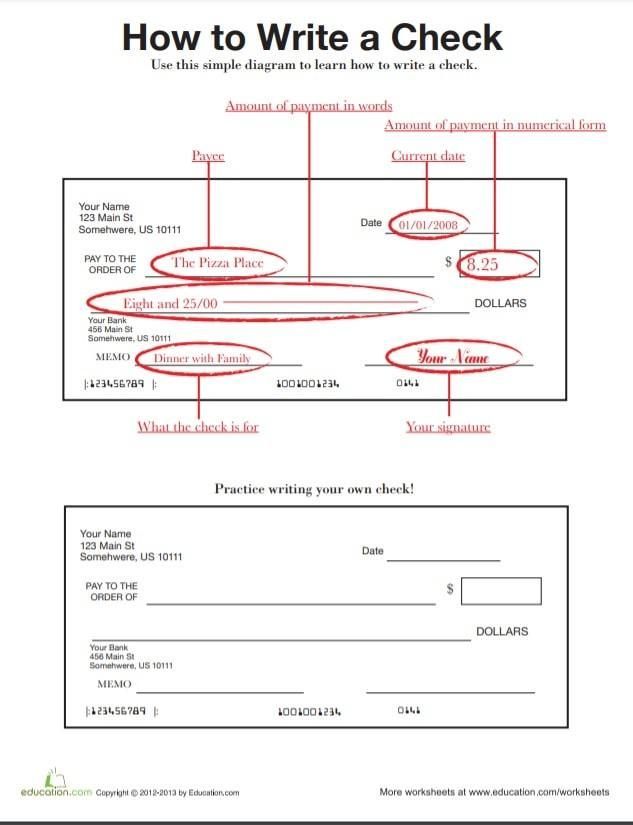

Handwriting practice

Prostock-studio/Shutterstock.com

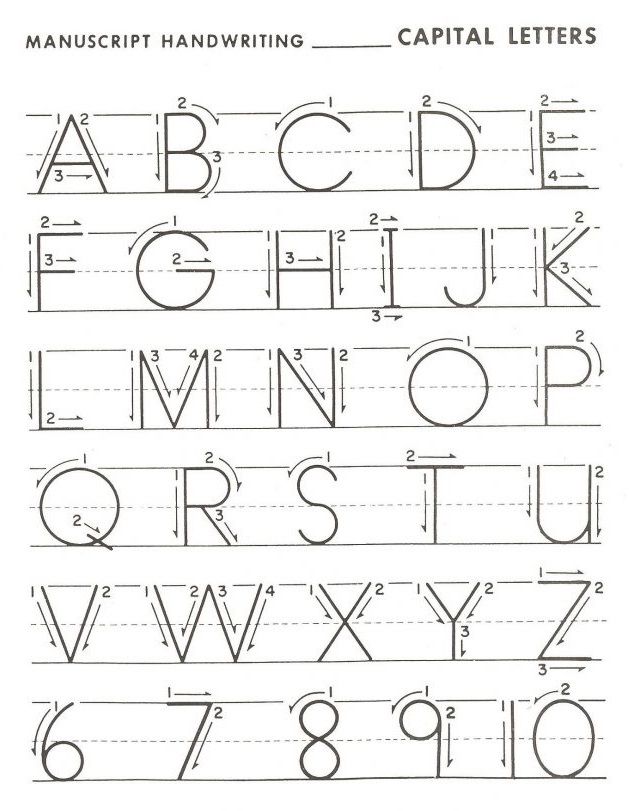

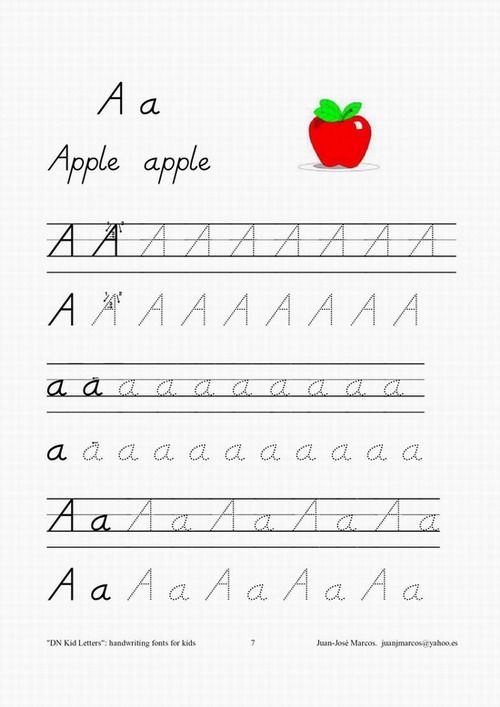

After completing the preparation, learn how to write capital letters in several stages.

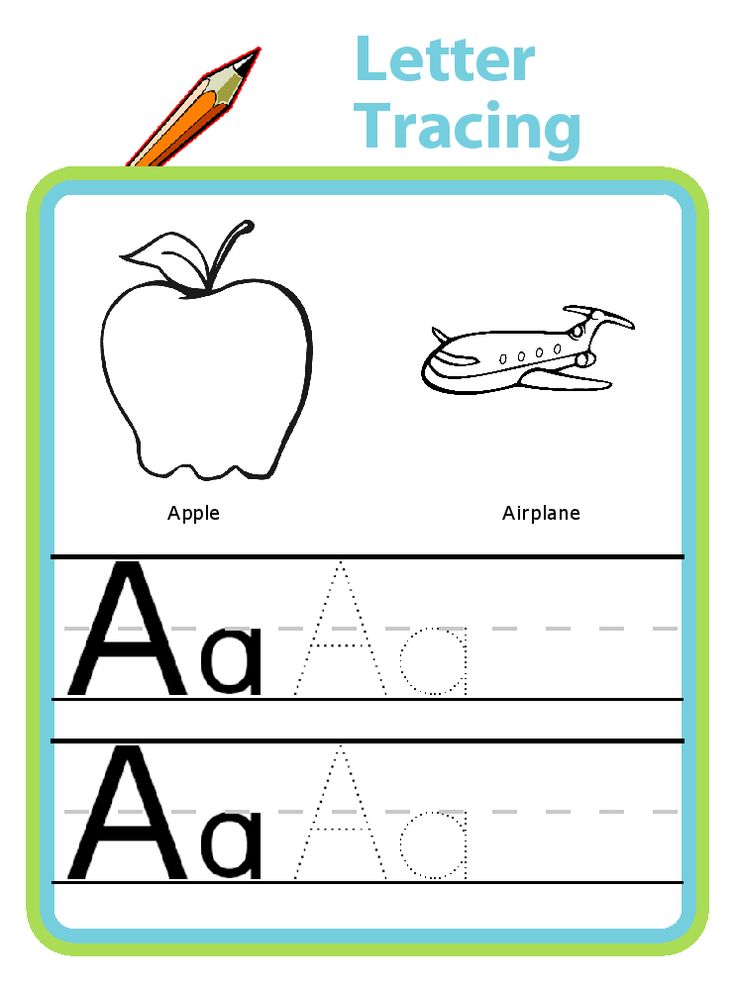

Writing with fingers

Letters are pronounced and made up of large seeds or buttons. They can be molded from plasticine or drawn on a misted window.

Learning the elements of letters

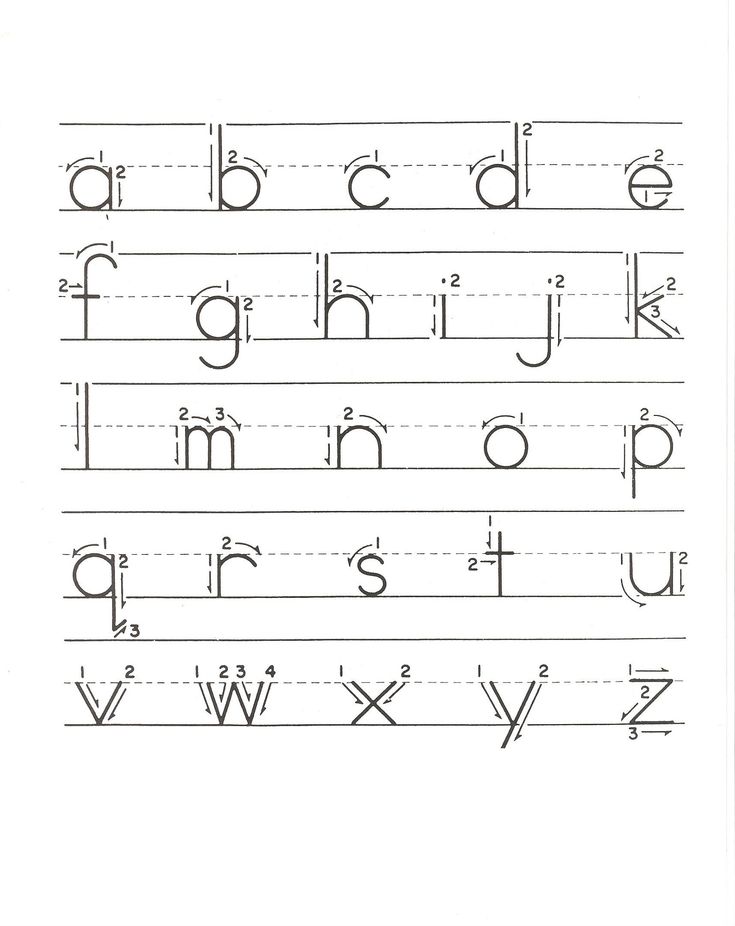

Write the elements of letters and numbers on landscape sheets. Many times in a row, vertical and horizontal lines, circles, ovals and other simple shapes are prescribed. The most difficult thing for children is to write "tails" - the upper and lower elements of such letters as B, C, D, Z, U, C, S.

Explain and play

Tell the child what a line is. All letters, numbers and other symbols must be clearly within its boundaries - no higher, no higher.

Start memorizing writing letters with a game. For example, let the child compare what is written with the outside world: the letter “O” looks like a sun or a ball, “C” looks like a crescent, “U” looks like a slingshot, “F” looks like a bug or a butterfly. This will help the baby to memorize letters faster.

This will help the baby to memorize letters faster.

After choosing the letter you want to learn with your child, first show them how to write it themselves. Repeat several times until the child remembers the algorithm of actions. Try to comment on your movements: “Now we are learning to write the letter C. We draw a line from top to bottom, smoothly, with a bend, without taking our hands off.”

Alternatively, you can try to draw the symbol in the air - show the child and then ask him to repeat several times. After that, move on to practice on paper.

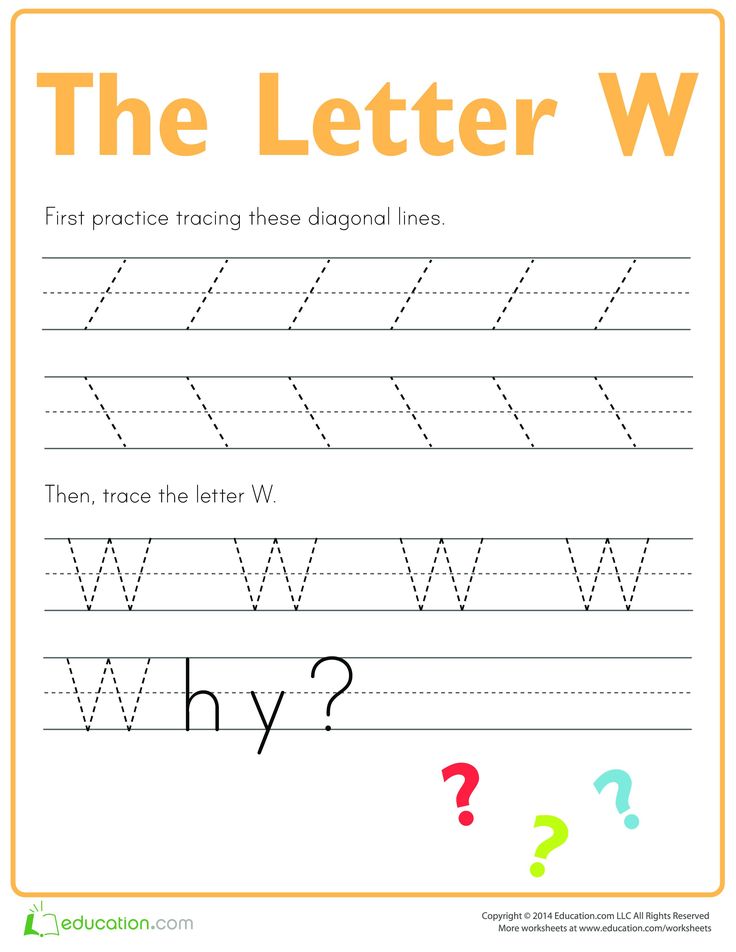

Working with copybooks

Prostock-studio/Shutterstock.com

Move on to writing block letters in copybooks - special notebooks for practicing writing. Buy prescriptions for preschoolers that offer diverse exercises.

In copybooks, the child will trace letters point by point, draw them according to the model, or fill in empty contours. Which recipes to choose - the parent decides. There is no consensus on which method is more effective. One child is given easy assignments, while the other experiences difficulties. The key to success is regular practice.

There is no consensus on which method is more effective. One child is given easy assignments, while the other experiences difficulties. The key to success is regular practice.

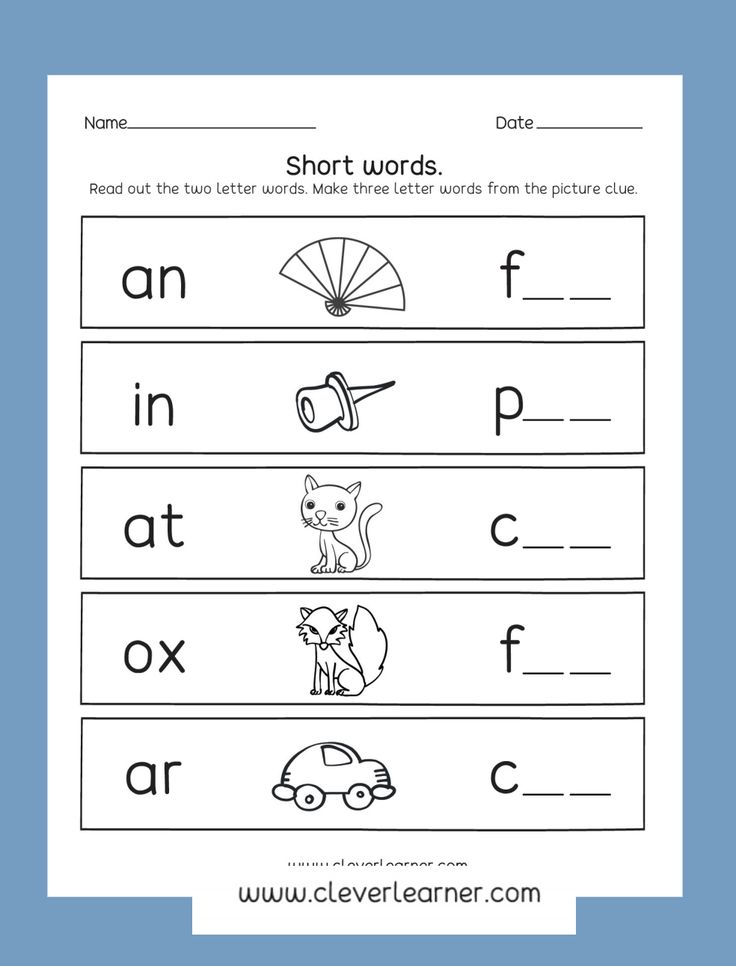

Writing by syllables

A difficult stage, which is started if the child already writes well in block letters. Start writing two-syllable words: ma-ma, pa-pa, water-yes, ka-sha and others. During the lesson, together with the child, say aloud what he writes.

Learning Numbers and Numbers

Take a squared notebook and first tell about the center, corners and middle of the sides of the cage. Explaining the designation of the number, pronounce each action. For example, the number "1" is written like this: put the pen just above the center of the cage, draw a straight line from the center to the upper right corner, and then draw a long straight line from it to the center of the bottom cage.

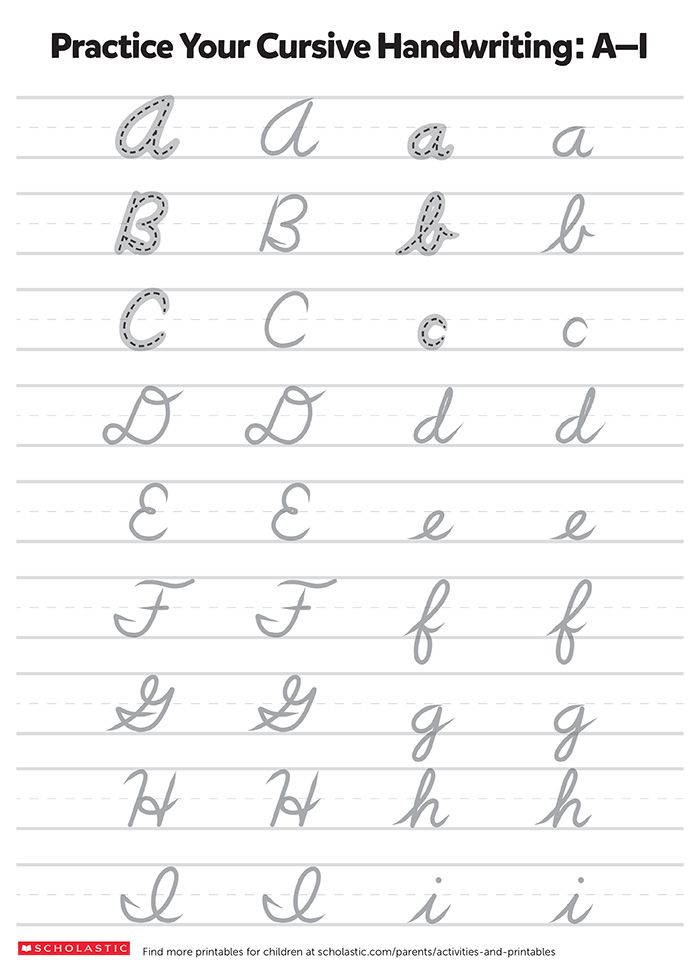

Learning calligraphy

It can take several years to develop beautiful handwriting. You need to connect and write letters correctly, and if you do not own this technique, then the child will have to relearn to meet the requirements of the school curriculum.

You need to connect and write letters correctly, and if you do not own this technique, then the child will have to relearn to meet the requirements of the school curriculum.

Use copybooks to practice letter combinations and develop writing technique. By grade 3, move on to rewriting passages of books in beautiful handwriting. Practice is a fundamental principle in calligraphy.

How to choose prescription?

Prostock-studio/Shutterstock.com

The range of printed products offers a variety of recipes to develop writing skills for children of all ages. Choose notebooks that have:

- Samples of the sign are repeated in each line or as often as possible on one page. It is easier for a kid to write, focusing on the sample located on the side of the pen than on the one that is indicated once at the top of the page.

- The first exercises are devoted to writing simple geometric shapes or letter elements. The presented material is compiled according to the scheme "from simple to complex".

- Learning begins with capital letters, not capital letters.

Bestselling copybooks for writing practice:

| Author | Benefit title | Child's age, years |

| Elena Kolesnikova | Recipe for preschoolers | from 5-6 |

| Elena Astafieva | We play, read, write. Workbook No. 1 | from 6 |

| Veronica Mazina | Learning to write beautifully! | from 6 |

| Olesya Zhukova | Recipe for future first-graders. We draw in cells. | from 6 |

| Olga Makeeva | Preparing a hand for writing (copybook with transparent sheets). | from 6-7 |

| Olga Lysenko | Beautiful handwriting in 20 lessons. | from 6-7 |

How to teach a child to write if he is left-handed?

Prostock-studio/Shutterstock. com

com

Children who find it easier to do things with their left hand don't need to be retrained. The success of training consists of 4 components:

- Seating at the table.

- Handle grip.

- Notebook position.

- Writing technique for left-handers.

For left-handers, the position at the table and the ability to hold a pen is no different from right-handers, with one caveat - the light should be on the right, not on the left. The notebook is placed at an angle of 45o or at an angle of 80-90o, so as not to twist the hand. The notebook should lie in the same way as for right-handed people, but in a mirror image.

Buy a left-handed manual that uses a narrow ruler at a different angle. Children should write either straight or with a slight tilt to the left. Don't force it to lean to the right. Buy thin pens with non-greasy ink so that your little one doesn't get their hands dirty.

The ability to write is the result of complex work, during which the baby learns to control hand movements, keep in mind the image of letters and numbers, remember the elements of symbols and how to connect them. Teach your child consistently: from the ability to hold a pen to writing syllables. Praise for effort, not achievement.

Teach your child consistently: from the ability to hold a pen to writing syllables. Praise for effort, not achievement.

Getting ready for school:

- How to get your child ready for school and not become bankrupt?

- The best smartphones for students for every wallet

- Student's workplace: choosing a chair and table

- Backpack, knapsack or briefcase for a student: what to choose and how?

- Preparation for September 1: checklist for parents. What should be done?

- What to give a child on September 1?

For parents of first graders and preschoolers:

- How to get into school: a complete guide for parents of first graders

- What you need to know about the psychological readiness of the child for learning

- First Grader Complete Set: What's on the shopping list

- How to help your child adjust to school

September 1, 2020:

- Will there be school assemblies this year on September 1?

- Russia may leave distance education after the pandemic

- School year won't start on September 1st? Opinion of Rospotrebnadzor

- General breaks will be canceled in schools, and classes will start at different times

Please rate the article

This is very important to us

Article rating: 0 / 5. Votes count: 0

Votes count: 0

There are no ratings yet. Rate first!

Receive a school preparation checklist to your mail

Letter sent!

Check e-mail

Write or read? | Papmambuk

Grandmothers who torture children with prescriptions usually motivate their behavior in the following way: if he goes to school, it will be easier for him. In the meantime, he writes letters, you look, and learn to read.

The first argument seems dubious: why should it be hard now in order to make it easier later?

But the second argument is justified.

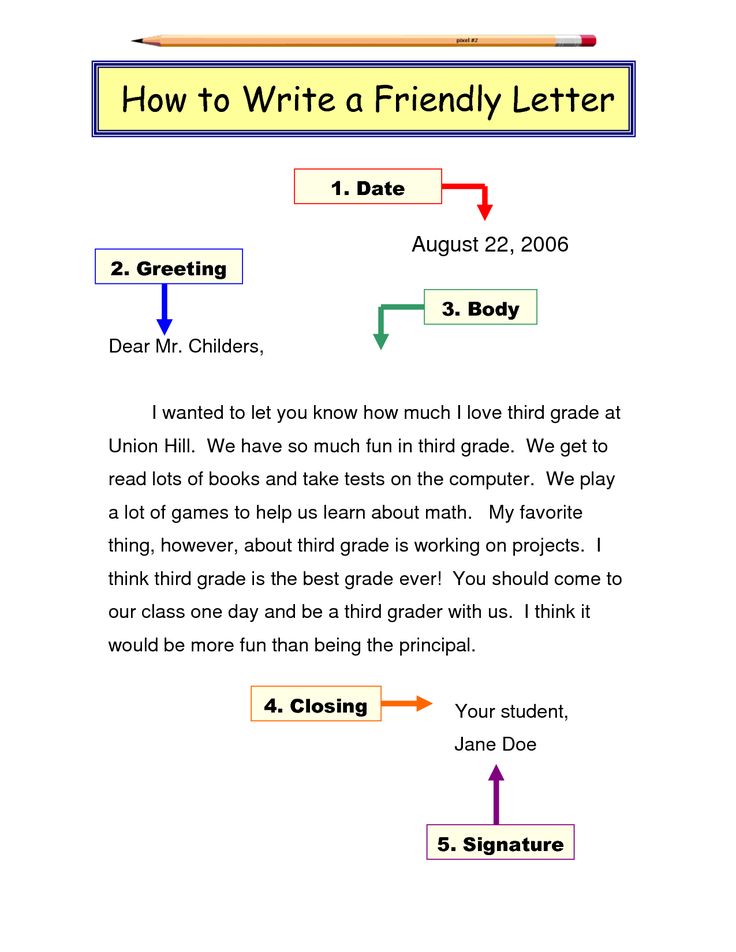

In the traditional school methodology, the so-called "literacy period" includes teaching both reading and writing at the same time.

Such an authoritative teacher as Maria Montessori also believed that writing should precede reading. In her system, teaching a child to write begins at the age of four. Moreover, this letter is “real”, calligraphic. And Maria Montessori, judging by her notes, achieved success along this path. In particular, according to her system, children with mental retardation were taught to write before entering school, which helped them integrate into the general education system of that time.

And Maria Montessori, judging by her notes, achieved success along this path. In particular, according to her system, children with mental retardation were taught to write before entering school, which helped them integrate into the general education system of that time.

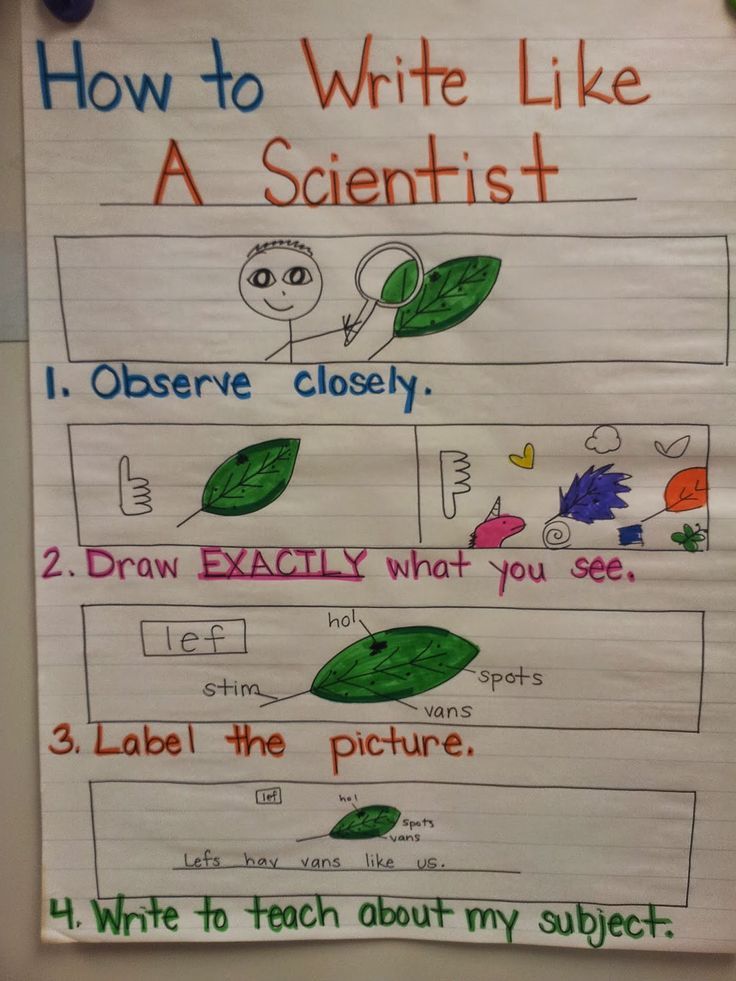

How was this explained? Writing, unlike reading, is a substantive activity: you put in the effort and the result is visible. This is important for the child. In addition, writing gives the "muscular experience" of the letter. Motor memory is included in the process of sign recognition. And when you write a syllable or a word, you merge the letters and involuntarily pronounce them. Therefore, writing really advances on the path to reading.

But there is one very important thing that Maria Montessori did not take into account. Writing is an activity related to drawing. And drawing during the development of the child performs many different functions. A child draws in a completely different way than an adult does. For a child, a drawing is a detailed message about the world around him and about his well-being. This is such a prototype. The classic of Russian psychology, Lev Vygotsky, said so: drawing in childhood precedes writing. But not writing in the sense of the sequential reproduction of letter icons, but in the sense of a written message, an essay.

For a child, a drawing is a detailed message about the world around him and about his well-being. This is such a prototype. The classic of Russian psychology, Lev Vygotsky, said so: drawing in childhood precedes writing. But not writing in the sense of the sequential reproduction of letter icons, but in the sense of a written message, an essay.

A child's drawing is a prototype of written speech, a detailed written statement. In the drawing, the child masters the properties of the sign: it turns out that everything around can be depicted using special icons. And this message - in the form of icons - will be clear to others. That is why it is so important to ask children about what they have drawn. Of course, the child does not always tell what he has drawn. Often, in the course of the story, he begins to invent something or “sees” in his drawing something that was not there initially. This is fine. Even good. And this is another component of the development of children's imagination. For us now, the main thing is that an independent children's drawing is a prototype of written speech, in which the imagination is very strongly involved and which is emotionally loaded.

For us now, the main thing is that an independent children's drawing is a prototype of written speech, in which the imagination is very strongly involved and which is emotionally loaded.

Writing at preschool age does not have one or the other.

Yes, you can teach your child to write early. Write beautifully and correctly. And if you are Maria Montessori, then your young students will not even irrigate the recipes with tears. They will even love it. But with all due respect to Montessori, it is impossible to hide the fact that her pupils did not draw. Generally. This was not included in her program. And they didn't listen to fairy tales. Maria Montessori, an advanced woman of her time, was a consistent sensualist who believed that the basis of knowledge is the physiology of sensations. And the main thing in education is to develop these feelings. There is a lot of truth in this.

But everything that had to do with fantasy and imagination, she considered harmful. Fantasizing, in her opinion, leads the child away from reality, from a real understanding of himself and the environment.

Fantasizing, in her opinion, leads the child away from reality, from a real understanding of himself and the environment.

In the 1920s, such thoughts without any connection with Montessori arose among Soviet teachers who professed materialistic philosophy. The so-called "fairy tale debate" that arose at that time called into question the value of many literary works. These ideas proved to be quite tenacious.

But at the beginning of the 21st century, we can say with full confidence that the most important discoveries are made by people with a developed imagination. And that in general imagination is a necessary component of thinking. Not only humanitarian, but also mathematical. They say that modern physicists beat all records in terms of the level of development of the imagination.

So the child's imagination, from the point of view of a child's life prospects, should concern us no less than children's skills related to a possible problem-free existence in the first grade.

And so we must be aware of what drawing is for a child.

Drawing, I repeat, in the course of child development precedes written speech. Developed independent children's drawing is an indicator that the child will be able to express his thoughts in writing.

But, paradoxically, as soon as we begin to teach a child to write, this affects his drawing in the most sad way - simply because these are related activities and drawing is almost inevitably replaced by writing along the way. Many of the children who draw interestingly and abundantly at a young age later lose this ability - if it is not supported by special efforts. That is, if drawing is not translated into another plane - into the plane of fine art.

It is for this reason that I would not advise parents to teach their young children from the recipes.

But!

In addition to capital letters, there is the so-called "picture writing" - when a child depicts letters as he "can". when he draws them.

Picture writing differs from copywriting primarily in that it arises spontaneously: the child suddenly begins to draw letters on his own initiative. And most often these letters appear in children's drawings. They are elements of children's drawings - evidence that writing is born from drawing.

Such attempts by a child to draw letters should be appreciated and supported. They signal that the child has already grown up to perceive the letter as a sign. This is the first sign that it will soon be possible to teach him to read. Moreover, he has already begun self-education. Only, learning does not take place at the speed with which we want (and we want it at a speed close to the cosmic one), and not at all according to the system that we set ourselves up for. As such, as a written message, he has yet to open the letter. And first he discovers the letter as a drawing.

Many parents have probably come across such a phenomenon as imitation of writing: wavy lines, hooks - this is how the child pretends to have written something. And he really wants you to read it. So read on, what do you need? Four year old - read. And be patient to wait until he himself understands that writing is something else.

And he really wants you to read it. So read on, what do you need? Four year old - read. And be patient to wait until he himself understands that writing is something else.

It is impossible to say how the child will move from drawing letters to reading. More precisely, we can assume some scenarios with more or less active participation of parents. But the main thing is not to rush. The first letter in the picture is just the first sign of spring in learning to read.

When I say "take your time" I only mean the parents. If the request to learn something comes from the child, it must be immediately satisfied - in order to maintain cognitive interest in good shape.

But you remember what happened to five-year-old Frieder from Gudrun Mebs' story “Grandmother! Frieder shouts? Frieder wanted to learn how to write. And the grandmother showed him a sample. And Frieder could not repeat the written word. And terribly upset. Then the wise grandmother suggested that her grandson blind this word.

That is, here you also have to be inventive. And it will be right at this stage - an understandable children's request - to use the experience of mankind. In particular, the experience of the same Maria Montessori. And Montessori, who knew a lot about muscle memory, introduced tracing paper as one of the methods of teaching writing.

I have not seen a single child who would deny himself the pleasure of copying pictures, letters and words. Only, unlike Montessori, we will not insist that the letters be written. This is what the child wants.

In general, I cannot but say that writing letters and the ability to write with a pen already looks somewhat archaic and is perceived as an exclusively school skill, which will no longer be seriously needed after graduation. Therefore, I would generally separate learning to read from learning to write. First, I would draw letters with the children and teach them to read. Then, print on the computer. And then, in the third grade, I would introduce the subject “calligraphy” into the program, where it would be possible to deal with already formed, adapted schoolchildren, with their physically sufficiently developed hand and the ability to look at writing as a special art.