How to teach a children

New skills for kids & behaviour management

Helping children learn new skills as part of behaviour management

When children can do the things they want or need to do, they’re more likely to cooperate. They’re also less likely to get frustrated and behave in challenging ways. This means that helping children learn new skills can be an important part of managing behaviour.

When children learn new skills, they also build independence, confidence and self-esteem. So helping children learn new skills can be an important part of supporting overall development too.

Here’s an example: if your child doesn’t know how to set the table, they might refuse to do it – because they can’t do it. But if you show your child how to set the table, they’re more likely to do it. They’ll also get a sense of achievement and feel good about helping to get your family meal ready.

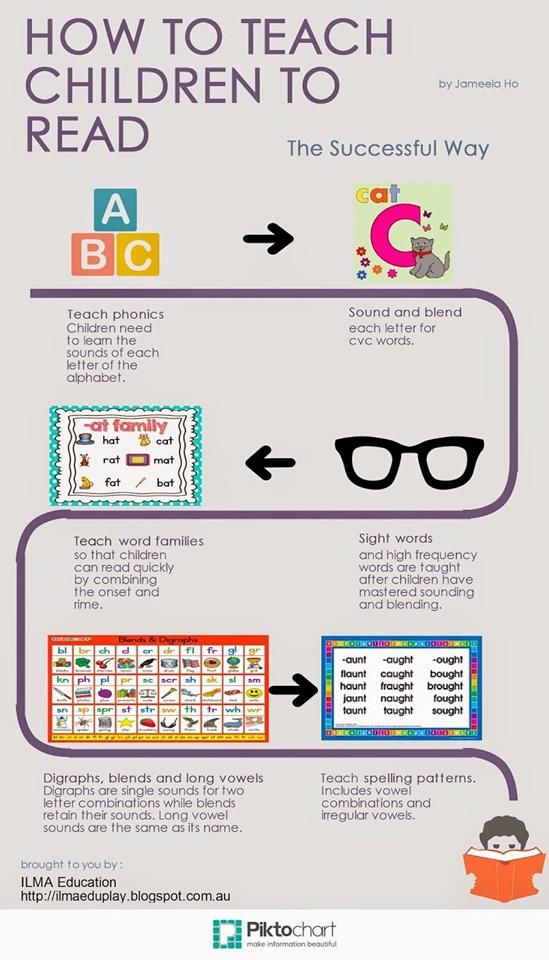

There are 3 key ways you can help children learn everything from basic self-care to more complicated social skills:

- modelling

- instructions

- step by step.

Remember that skills take time to develop, and practice is important. But if you have any concerns about your child’s behaviour, development or ability to learn new skills, see your GP or your child and family health nurse.

When you’re helping your child learn a skill, you can use more than one teaching method at a time. For example, your child might find it easier to understand instructions if you also break down the skill or task into steps. Likewise, modelling might work better if you give instructions at the same time.

Modelling

Through watching you, your child learns what to do and how to do it. When this happens, you’re ‘modelling’.

Modelling is usually the most efficient way to help children learn a new skill. For example, you’re more likely to show rather than tell your child how to make a bed, sweep a floor or throw a ball.

Modelling can work for social skills. Prompting your child with phrases like ‘Thank you, Mum’, or ‘More please, Dad’ is an example of this.

You can also use modelling to show your child skills and behaviour that involve non-verbal communication, like body language and tone of voice. For example, you can show how you turn to face people when you talk to them, or look them in the eyes and smile when you thank them.

Children also learn by watching other children. For example, your child might try new foods with other children at preschool even though they might not do this at home with you.

How to make modelling work well

- Get your child’s attention, and make sure your child is looking at you.

- Move slowly through the steps of the skill so that your child can clearly see what you’re doing.

- Point out the important parts of what you’re doing – for example, ‘See how I am …’. You might want to do this later if you’re modelling social skills like greeting a guest.

- Give your child plenty of opportunities to practise the skill once they’ve seen you do it – for example, ‘OK, now you have a go’.

Instructions

You can help your child learn how to do something by explaining what to do or how to do it.

How to give good instructions

- Give instructions only when you have your child’s attention.

- Use your child’s name and encourage your child to look at you while you speak.

- Get down to your child’s physical level to speak.

- Remove any background distractions like the TV.

- Use language that your child understands. Keep your sentences short and simple.

- Use a clear, calm voice.

- Use gestures to emphasise things that you want your child to notice.

- Gradually phase out your instructions and reminders as your child gets better at remembering how to do the skill or task.

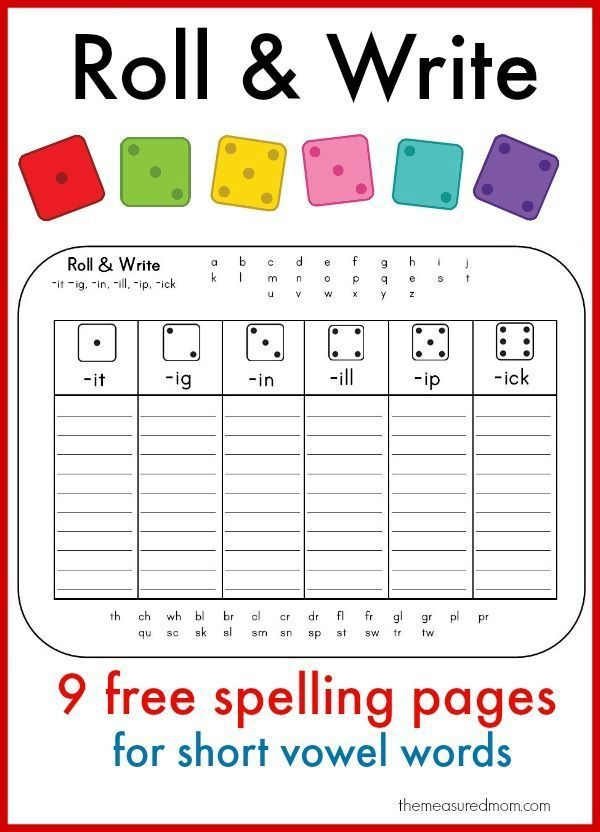

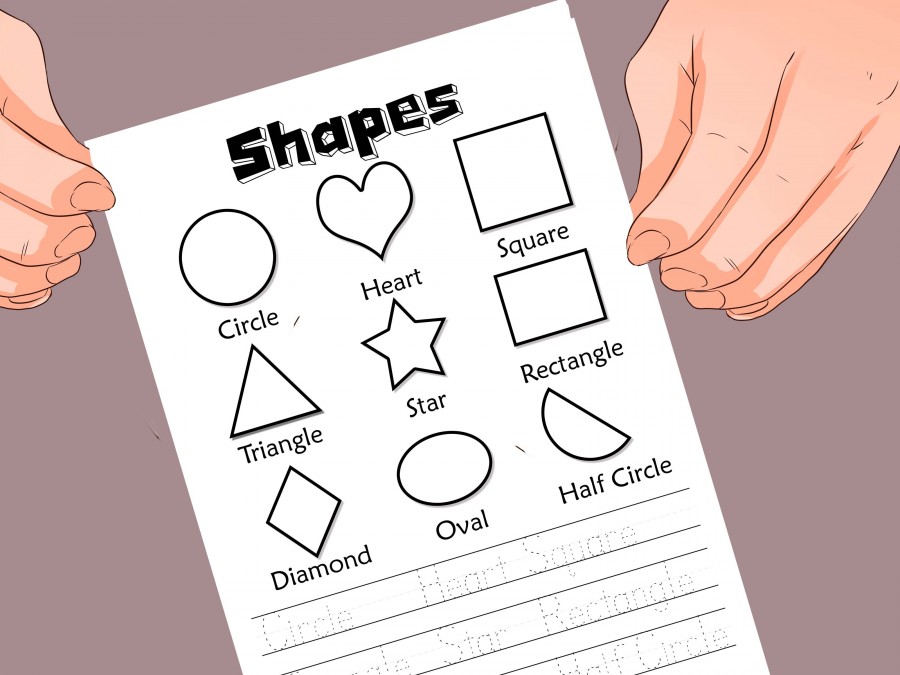

A picture that shows your child what to do can help them understand the instructions. Your child can check the picture when they’re ready to work through the instructions independently. This can also help children who have trouble understanding words.

Sometimes your child won’t follow instructions. This can happen for many reasons. Your child might not understand. Your child might not have the skills to do what you ask every time. Or your child just might not want to do what you’re asking. You can help your child learn to cooperate by balancing instructions and requests.

Step-by-step guidance: breaking down tasks

Some skills or tasks are complicated or involve a sequence of actions. You can break these skills or tasks into smaller steps. The idea is to help children learn the steps that make up a skill or task, one at a time.

How to do step-by-step guidance

- Start with the easiest step if you can.

- Show your child the step, then let them try it.

- Give your child more help with the rest of the task or do it for them.

- Give your child opportunities to practise the step.

- When your child can do the step reliably and without your help, teach them the next step, and so on.

- Keep going until your child can do the whole skill or task for themselves.

An example of step-by-step guidance

Here’s how you could break down the task of getting dressed:

- Get clothes out.

- Put on underpants.

- Put on socks.

- Put on shirt.

- Put on pants.

- Put on a jumper.

You could break down each of these steps into parts as well. This can help if a task is complex or if your child has learning difficulties. For example, ‘Put on a jumper’ could be broken down like this:

- Face the jumper the right way.

- Pull the jumper over your head.

- Put one arm through.

- Put your other arm through.

- Pull the jumper down.

Forwards or backwards steps?

You can help your child learn steps by moving:

- forwards – teaching your child the first step, then the next step and so on

- backwards – helping your child with all the steps until the last step, then teaching the last step, then the second last step and so on.

Learning backwards has some advantages. Your child is less likely to get frustrated because it’s easier and quicker to learn the last step. Also the task is finished as soon as your child completes the step. Often the most rewarding thing about a job or task is getting it finished!

In the earlier example, you might teach your child to get dressed by starting with a jumper. You’d help your child get dressed until it came to the final step – the jumper.

You might help your child put the jumper over their head and put their arms in – then you might let your child pull the jumper down by themselves. Once your child can do this, you might encourage your child to put their arms through by themselves and then pull the jumper down. This would go on until your child can do each step, so they can do the whole task for themselves.

When your child is learning a new physical skill like getting dressed, it can help to put your hands over your child’s hands and guide your child through the movements. Phase out your help as your child begins to get the idea, but keep saying what to do. Then simply point or gesture. When your child is confident with the skill, you can phase out gestures too.

Phase out your help as your child begins to get the idea, but keep saying what to do. Then simply point or gesture. When your child is confident with the skill, you can phase out gestures too.

Tips to help children learn new skills

No matter which of the methods you use, these tips will help your child learn new skills:

- Make sure that your child has the physical ability and developmental maturity to handle the new skill. You might need to teach your child some basic skills before working on more complicated skills.

- Consider timing and environment. Children learn better when they’re alert and focused, so it can be good to work on new skills in the morning or after rest time. It’s also good to avoid distractions, like the TV or younger siblings.

- Give your child the chance to practise the skill. Skills take time to learn, and the more your child practises, the better.

- Give lots of praise and encouragement, especially in the early stages of learning.

Praise your child when they follow your instruction, practise the skill or try hard, and say exactly what your child did well.

Praise your child when they follow your instruction, practise the skill or try hard, and say exactly what your child did well. - Avoid giving negative feedback. Rather than saying your child has done it ‘wrong’, use words and gestures to explain 1-2 things your child could do differently next time.

Remember that behaviour might get worse before it improves, especially if you’re asking more from your child. A positive and constructive approach can help – for example, ‘Well done for getting the knots on your laces right! Would you like to do the loops together today?’

Strategies Teachers Use to Help Kids Who Learn and Think Differently

Your child’s teachers may use a variety of teaching strategies in their classrooms. But do these strategies help kids who learn and think differently?

There’s no one way for teachers to deliver instruction to their students. However, some strategies are backed by research and are more effective than others.

These approaches and techniques can benefit all students. But they’re especially helpful to kids who learn and think differently. They can make a big difference in how well struggling students take in and work with information. (Some may even be used as formal accommodations in and .)

But they’re especially helpful to kids who learn and think differently. They can make a big difference in how well struggling students take in and work with information. (Some may even be used as formal accommodations in and .)

You may have heard of one or more of these strategies from your child’s classroom or special education teachers. If not, you can ask the teachers whether they use the strategies and how you might adapt them to use at home.

Here are six common teaching strategies. Learn more about what they are and how they can help kids who learn and think differently.

1. Wait time

“Wait time” (or “think time”) is a three- to seven-second pause after a teacher says something or asks a question. Instead of calling on the first students who raise their hand, the teacher will stop and wait.

This strategy can help with the following issues:

- Slow processing speed: For kids who process slowly, it may feel as though a teacher’s questions come at rapid-fire speed.

“Wait time” allows kids to understand what the teacher asked and to think of a response.

“Wait time” allows kids to understand what the teacher asked and to think of a response. - ADHD: Kids with ADHD can benefit from wait time for the same reason. They have more time to think instead of calling out the first answer that comes to mind.

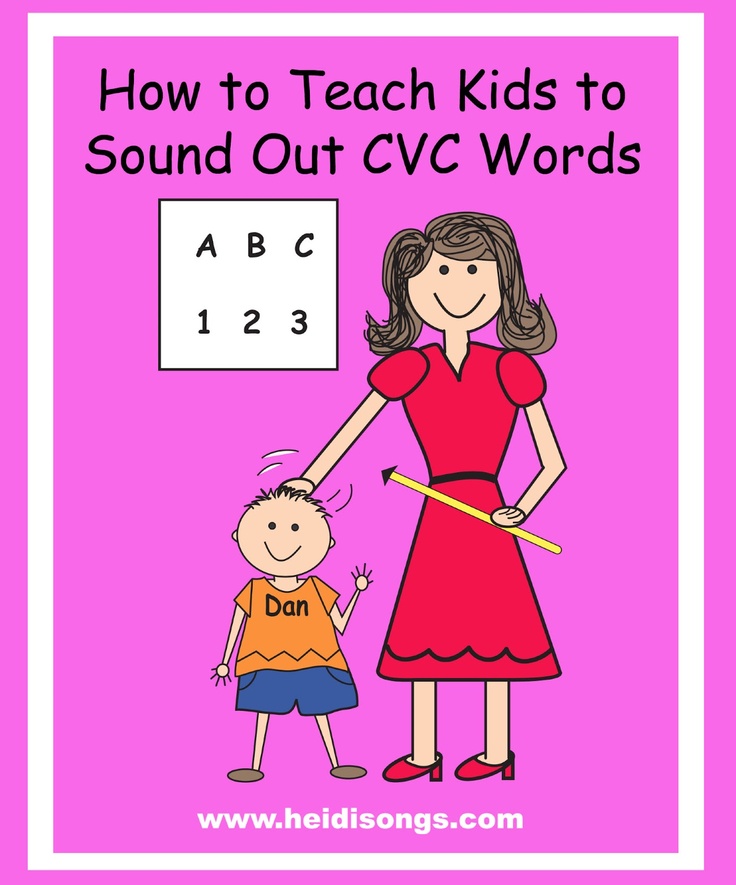

2. Multisensory instruction

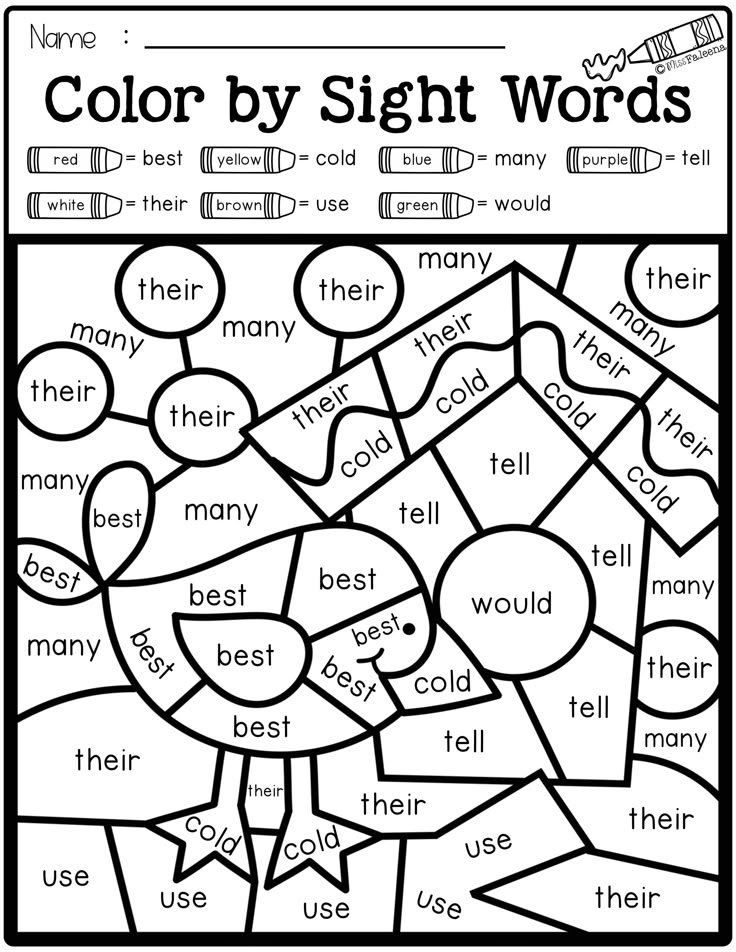

Multisensory instruction is a way of teaching that engages more than one sense at a time. A teacher might help kids learn information using touch, movement, sight and hearing.

This way of teaching can help with these issues:

- Dyslexia: Many programs for struggling readers use multisensory strategies. Teachers might have students use their fingers to tap out each sound in a word, for example. Or students might draw a word in the air using their arm.

- Dyscalculia: Multisensory instruction is helpful in math, too. Teachers often use hands-on tools like blocks and drawings. These tools help kids to “see” math concepts. Adding 2 + 2 is more concrete when you combine four blocks in front of you.

You may hear teachers refer to these tools as manipulatives.

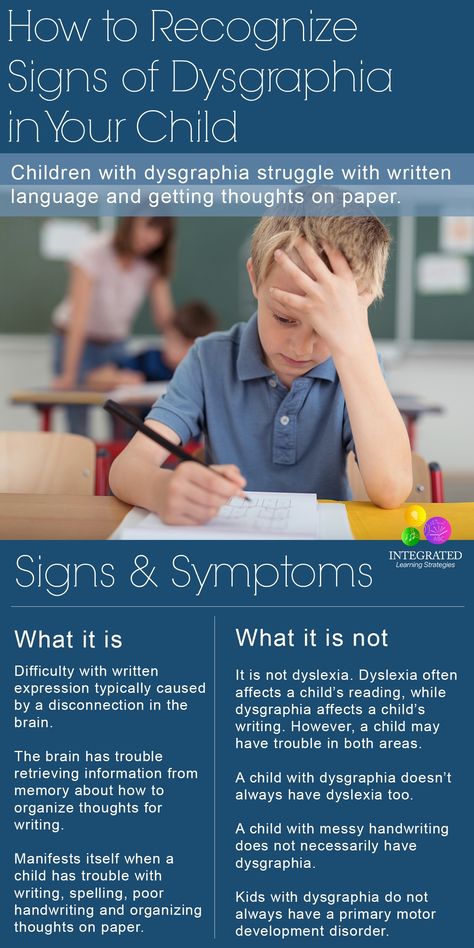

You may hear teachers refer to these tools as manipulatives. - Dysgraphia: Teachers also use multisensory instruction for handwriting struggles. For instance, students use the sense of touch when they write on “bumpy” paper.

- ADHD: Multisensory instruction can help with different ADHD symptoms. That’s especially true if the technique involves movement. Being able to move can help kids burn excess energy. Movement can also help kids focus and retain new information.

3. Modeling

Most kids don’t learn simply by being told what to do. Teachers use a strategy called “I Do, We Do, You Do” to model a skill. The teacher will show how to do something (“I do”), such as how to do a math problem. Next, the teacher will invite kids to do a problem with the teacher (“we do”). Then, kids will try a math problem on their own (“you do”).

This strategy can help with these issues:

- All learning and thinking differences: When used correctly, I Do, We Do, You Do can benefit all learners.

That’s because a teacher can provide support during each phase. However, teachers must know what support to provide. They also need to know when students understand a concept well enough to work on their own. Think of it like riding a bike: The teacher needs to know when to take off the training wheels.

That’s because a teacher can provide support during each phase. However, teachers must know what support to provide. They also need to know when students understand a concept well enough to work on their own. Think of it like riding a bike: The teacher needs to know when to take off the training wheels.

4. Graphic organizers

Graphic organizers are visual tools. They show information or the connection between ideas. They also help kids organize what they’ve learned or what they have to do. Teachers use these tools to “scaffold,” or provide support around, the learning process for struggling learners. (It’s the same idea as when workers put up scaffolding to help construct a building.)

There are many different kinds of graphic organizers, such as Venn diagrams and flow charts. They can be especially helpful with these issues:

- Dyscalculia: In math, graphic organizers can help kids break down math problems into steps. Kids can also use them to learn or review math concepts.

- Dysgraphia: Teachers often use graphic organizers when they teach writing. Graphic organizers help kids plan their ideas and writing. Some also provide write-on lines to help kids space their words.

- Executive functioning issues: Kids with weak executive skills can use these tools to organize information and plan their work. Graphic organizers can help kids condense their thoughts into short statements. This is useful for kids who often struggle to find the most important idea when taking notes.

5. One-on-one and small group instruction

One strategy that teachers use is to vary the size of the group they teach to. Some lessons are taught to the whole class. Others are better for a small group of students or one student. Learning in a small group or one-on-one can be very helpful to kids with learning and thinking differences.

Some kids are placed in small groups because of their IEPs or an intervention. But that’s not always the case. Teachers often meet with small groups or one student as a way to differentiate instruction. This means that they tailor the lesson to the needs of the student.

Teachers often meet with small groups or one student as a way to differentiate instruction. This means that they tailor the lesson to the needs of the student.

This strategy helps with:

- Dyslexia: Students with dyslexia frequently meet in small group settings for reading. In the general classroom, teachers often work with a small group of kids at the same reading level or to focus on a specific skill. They might also meet because kids have a common interest in a book.

- Dyscalculia: For kids with dyscalculia, teachers gather one or more students to practice skills that some students (but not the whole class) need extra help with.

- Dysgraphia: In many classrooms, teachers hold “writing conferences.” They meet with students one-on-one to talk about their progress with what they’re writing. For students with dysgraphia, a teacher can use this opportunity to check in and focus on specific skills for that student.

- ADHD and executive functioning issues: This type of instruction often takes place in settings with fewer distractions.

The teacher can also help students stay on task and learn skills like self-monitoring.

The teacher can also help students stay on task and learn skills like self-monitoring. - Slow processing speed: Teachers can adjust the pace of instruction to give students the time they need to take in and respond to information. In these groups, teachers can focus on the priorities of the lesson so students have the time to grasp the most important concepts. Being in a focused setting may also help decrease the anxiety students feel in whole-class lessons.

6. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) strategies

UDL is a type of teaching that gives all students flexible ways to learn and succeed. UDL strategies allow kids to access materials, engage with them and show what they know in different ways. There are many examples of how these strategies help kids who learn and think differently.

- ADHD: UDL allows students to work in flexible learning environments. For students who struggle with inattention and distractibility, a teacher might allow a student to work in a quiet space away from the class.

Or the student may want to wear earbuds or headphones.

Or the student may want to wear earbuds or headphones. - Executive functioning issues: Following directions can be tough for kids with executive functioning issues. One UDL strategy is to give directions in more than one format. For instance, a teacher might give directions out loud and write them on the board.

- Dyslexia: When teachers follow UDL principles, they present information in many different ways. For instance, instead of telling students they must read a book, they would be invited to listen to an audiobook. This removes a barrier for students who struggle with reading.

- Dysgraphia: One UDL strategy is to give assignment choices. Kids with dysgraphia may struggle to show how much they know about history by writing an essay. But they may shine when delivering a presentation or acting out a historical skit.

To learn more about any of these teaching strategies, talk with your child’s teacher. Ask which strategies they use, whether they are evidence-based and how you might use them at home.

Key takeaways

Some teaching strategies may be part of a child’s IEP or 504 plan.

The strategies aim to give kids needed support as they learn.

Talk with your child’s teachers about the strategies they use.

Related topics

School supports

6 ways to teach your child to learn

One of the most common parental requests is "The child does not want to learn, what should I do?". But in order to want to learn, you must at least be able to learn. And this is a skill! Our blogger, child psychologist Olga Kondrashova talks about how to acquire and develop this skill.

You should not expect that a child will be able to do it on his own: while a small person is in grades 1-2 (in grade 3, responsibility for himself more or less begins to turn on), he is not yet very collected, organized, simply “sane”. Therefore, he needs outside control, that is, he must simply be taught to learn, to show how it is done.

Of course, there are children who, due to increased anxiety, for example, fear of the teacher or parents, or, conversely, excessive fascination with the teacher (more common among girls), are themselves worried about doing homework. But this is rather an exception to the general rule. So, the responsibility for a child's ability to learn lies largely with adults!

Now there are many expert assessments that come down to the thesis - the child's interest is above all. I agree that it is criminal to crush the initiative of a child. But, unfortunately, excitement from novelty falls even in an adult, and the ability to return oneself to concentration, whether it be solving a problem or simply assimilating new information, I think, will remain relevant. At least until we are "chip" with already built-in programs, by analogy with gadgets. But for now, you and I have children, not robots. And after a certain time, your child will move from elementary school to high school, where it will be more difficult to study.

In addition, the motivational priority shifts in high school — the child “flies” from the importance of learning to the importance of establishing social connections (friends are above all!)

he will no longer fall into hopelessness or despair - "everything is useless, everything is already so neglected, such a wild volume, I can no longer cope with it, there is no point in even starting!". There will be no such problems if the child already has a conscious experience of "inclusion" in the lessons. How to keep the attention of the child during the lessons?

1. Give new meaning to boring tasks

For example, a child needs to learn how to write letters beautifully. Options: “OK, how are we going to write a message to Santa Claus? He won’t understand anything in your scribbles, it will be a shame if you don’t get what you ask for for the New Year ”... Or: “Let's write a letter to grandmother? You just need to write so that she can read, she doesn’t see very well!” Or: “What if you find yourself on a desert island? Then you will need to write a message to people and send it in a bottle. Let's learn to write legibly!

Let's learn to write legibly!

2. Stimulate intrinsic motivation

You can ask a child and encourage him to think about what this or that skill will give him - the ability to read, write, count, memorize. This can become the basis of his own intrinsic motivation - the strongest and brightest stimulus. Alas, it burns brightly, but not for very long. It will be necessary to periodically remind the child about the benefits of what he himself once thought of and what he himself came to.

3. Change roles - instead of a student "teacher"

All lecturers know that if you want to know a subject better, give a lecture on it. We turn the child into a teacher, put all his bunnies, cars, bears, dolls in front of him and play school. By the way, you can also play along in the role of the most naughty and most "talentless" student - "Oh, how difficult it is to write these numbers! I can't do it at all!" Or deliberately make a lot of mistakes. Usually children are very happy when they see themselves from the outside.

This technique relieves tension, allows you to speak in a safe mode and realize the difficulty of learning. And this, as you remember, improves self-control and increases "sanity", that is, the child sees an obstacle (laziness, inattention, inability to force himself to finish) with which he needs to cope.

Plus, this reduces the fear of making mistakes. This is a very important point, because children at school are constantly in the zone of anxiety and incompetence - every day they are faced with new material, new tasks and new requirements for their intellectual abilities. The ability to calmly endure failures and mistakes is an important quality that allows you to move forward, and not fall into the pit "I am a worthless clumsy."

4. Teach him to do his homework

After some time, when you see that the child has mastered the skill of "doing homework", we gradually begin to leave him alone. But it is necessary to make sure that the child understands that failure to do homework and poor study in general have negative emotional consequences for him. That is, you need to create a field of expectations around it, in which there are necessarily two topics.

That is, you need to create a field of expectations around it, in which there are necessarily two topics.

First, let him know that you appreciate his efforts. You can say: “We are happy when you are doing well” or “We are upset when you are not doing well.” So the child will learn that you respect his work, his efforts on himself, his ability to show his will, his growing and strengthening independence. This also allows one to form such an important quality of character as the ability to achieve goals and respect oneself for the result achieved.

The child will learn to motivate himself with this experience and the feeling of joy and elation that will follow each self-conquest. An important nuance - try to make your comments for the child clear and specific. Not just "You're great!" or “Excellent!”, but “How glad I am that you managed to finish everything!”.

Second - say that if something does not work out, then this is not a disaster! This will allow the child to avoid excessive anxiety about punishments and disappointment in him and remove a negative emotional connotation from the learning process. For example, you can tell him: “If something doesn’t work out so well for you, know that we will always help you”, “We will not scold you for a bad grade. Let's just agree, if something doesn't work out for you or you don't understand something at school, speak right away and together we will sort out difficult places or explain to you what you didn't understand. We will always help, the main thing is not to launch the item, ok?".

For example, you can tell him: “If something doesn’t work out so well for you, know that we will always help you”, “We will not scold you for a bad grade. Let's just agree, if something doesn't work out for you or you don't understand something at school, speak right away and together we will sort out difficult places or explain to you what you didn't understand. We will always help, the main thing is not to launch the item, ok?".

This is how the child receives a vector of development - that is, he is not indifferent, his efforts are important and appreciated by someone. At the same time, parents do not viciously control him, but worry about him and are always ready to help and support him.

5. Share successes

At a family dinner or on a walk, you can discuss with your child that he has now become more adult, especially since he himself strives for this, expecting to go to first grade. And adults always have things that they don’t want to do, but they have to! Because it leads to such and such "cool" results. It is imperative to emphasize the very important and positive consequences of these cases with the “must” mark. It’s good that all family members tell the child what these “needs” they personally have and why it is important to fulfill them, what good can come from them.

It is imperative to emphasize the very important and positive consequences of these cases with the “must” mark. It’s good that all family members tell the child what these “needs” they personally have and why it is important to fulfill them, what good can come from them.

At the end of the day, you can share with each other how hard it was for everyone to have their "must", but we - cheers! - dealt with them!

6. Work with material

Last general rule. When checking your child's homework, remember that the best way to master, remember or know the material being studied well is not to read it 100 times, but to tell it once or do some tasks based on this material.

Photo: Unsplash (Aaron Burden)

How to teach a child to learn? Is it possible to learn to learn and what does it mean?

<

How to teach children to study well

Children are inquisitive by nature. As a rule, everything is new to them in elementary school, and therefore it is interesting. There is a new item - great! We set a new type of tasks - great, I want to try it as soon as possible! They do not need to be taught to learn, they do it with pleasure.

There is a new item - great! We set a new type of tasks - great, I want to try it as soon as possible! They do not need to be taught to learn, they do it with pleasure.

With the transition to high school, the program becomes more complicated, and communication becomes the leading activity for the child. It is at this point that adults should explain how to learn how to study properly. Here are some recommendations from Foxford Home School tutors on this matter.

Tip 1. Focus on interests

Learning to learn means finding the interest in which the child wants to develop. According to tutor Yulia Rozhkova, without this, all other methods are meaningless.

Ask your child to think about what a particular skill will do in relation to their favorite activity. Suppose he likes to ride a scooter. Push him to understand that knowing the laws of physics will help him do cool tricks, and the English language will help him communicate with riders from all over the world.

What to do if the child does not have pronounced hobbies? Take a closer look at him, offer to pass the Skillfolio diagnostics, which is just aimed at identifying the strengths and interests of schoolchildren. And most importantly, help your child acquire a hobby. Do something together, set an example.

Tip 2. Show how to acquire and apply knowledge

Just as swallowing food without chewing can lead to stomach problems, absorbing knowledge without reflection and application can lead to “loss of appetite” for learning.

The process of acquiring knowledge and skills based on it should ideally consist of several stages. First, acquaintance with some object or phenomenon, then the desire to understand how it works, putting it into practice, and, finally, understanding the experience. This circle is called the wheel of learning.

Learning wheel

Tutor Natalia Smelova uses the concept of the learning wheel in her work. At the same time, she believes that you should not give the child a "fish" - you need to teach him how to use a fishing rod. Suppose a student does not understand percentages in mathematics. Ask him to find a cartoon or a good article on the Internet on this topic. It is important that he does it himself, because only by gaining knowledge on his own, you can learn how to learn. However, then be sure to take the material found together and show how it can be useful to him in real life. For example, you can calculate how much you can save in a year if you set aside 10% of pocket money every month.

At the same time, she believes that you should not give the child a "fish" - you need to teach him how to use a fishing rod. Suppose a student does not understand percentages in mathematics. Ask him to find a cartoon or a good article on the Internet on this topic. It is important that he does it himself, because only by gaining knowledge on his own, you can learn how to learn. However, then be sure to take the material found together and show how it can be useful to him in real life. For example, you can calculate how much you can save in a year if you set aside 10% of pocket money every month.

Tip 3. Teach your child to tell the time

Most kids know how to tell the time with a clock before school. But even some high school students do not have an understanding of the value of a temporary resource. Calling to and from the lesson should gradually teach the student that in 45 minutes you can do about the same amount of work, and, for example, if the teacher reminds you that there are a few minutes left until the end of the lesson, you need to speed up. However, not everyone develops this trigger. And if the child is in family schooling, then the sense of time needs to be trained separately in order to eventually teach the child to learn independently.

However, not everyone develops this trigger. And if the child is in family schooling, then the sense of time needs to be trained separately in order to eventually teach the child to learn independently.

Here are the questions tutor Maria Suvorova recommends asking in order to teach a child to keep track of time:

- How much time do you have now?

- How will you best manage it?

- By what criteria will you choose the things you will do?

- What exactly do you want to do with your studies in the allotted time?

- What result do you want to get?

- Compare what you wanted to do and what you did?

- Are you satisfied with the result?

- How to make sure that there is enough time for all tasks?

Tip 4. Try different formats

In the article on how to study things you hate, we said that people are divided into visuals, auditory, kinesthetics and digitals. Find out which channel of perception works best for the child, and offer him appropriate learning formats. For example, a student complains that it is difficult for him to memorize vocabulary words. You can invite him to conduct an experiment to find the ideal way to memorize them: visualization using mnemonics, speaking into a voice recorder and listening, repeatedly writing in a notebook, analyzing the etymology of each word. Let the child try everything and rank which method worked best for him. Independent search will help the child learn to learn with pleasure.

For example, a student complains that it is difficult for him to memorize vocabulary words. You can invite him to conduct an experiment to find the ideal way to memorize them: visualization using mnemonics, speaking into a voice recorder and listening, repeatedly writing in a notebook, analyzing the etymology of each word. Let the child try everything and rank which method worked best for him. Independent search will help the child learn to learn with pleasure.

Advice 5. Let the child control the learning process

“Get out the diary, show what you have been asked”, “Write on a draft - I will come and check it” - many parents recognize themselves in these phrases. Unfortunately, adults from the first grade often show overprotectiveness in relation to the child's studies, which destroys motivation and independence.

“A junior high school student does not see the whole, so for the time being he cannot choose what to teach him, but he can decide when and in what sequence to do the lessons. So let him do it!” - calls the tutor of the "Foxford Home School" Svetlana Goltser. Let him draw up a schedule for doing homework, prepare for certification and get well-deserved marks on it. This will let the child know that you trust him, and will relieve the feeling of anxiety in anticipation of punishment for every wrong step.

So let him do it!” - calls the tutor of the "Foxford Home School" Svetlana Goltser. Let him draw up a schedule for doing homework, prepare for certification and get well-deserved marks on it. This will let the child know that you trust him, and will relieve the feeling of anxiety in anticipation of punishment for every wrong step.

Parental control must be weakened as one grows older. A teenager should be aware that studying is his area of responsibility. Cultivate self-discipline in a teenager, and he will never have a request “I want to learn how to study.” Getting new knowledge for him will be as natural as brushing his teeth in the morning.

Conclusions

The answer to the question, is it possible to teach a child to learn, unequivocal - yes, you can! Determine the student's area of interest, show the practical benefits of the knowledge gained and the value of time, try different learning formats. And most importantly - trust your child!

Foxford Home Online School tutors are ready to help you and your child develop self-education skills, show how to teach children to study well and with pleasure.