Importance of following direction

The Psychology of Following Instructions and Its Implications

Am J Pharm Educ. 2020 Aug; 84(8): ajpe7779.

doi: 10.5688/ajpe7779

, PharmD,a, BS,a and , PhDa,b

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

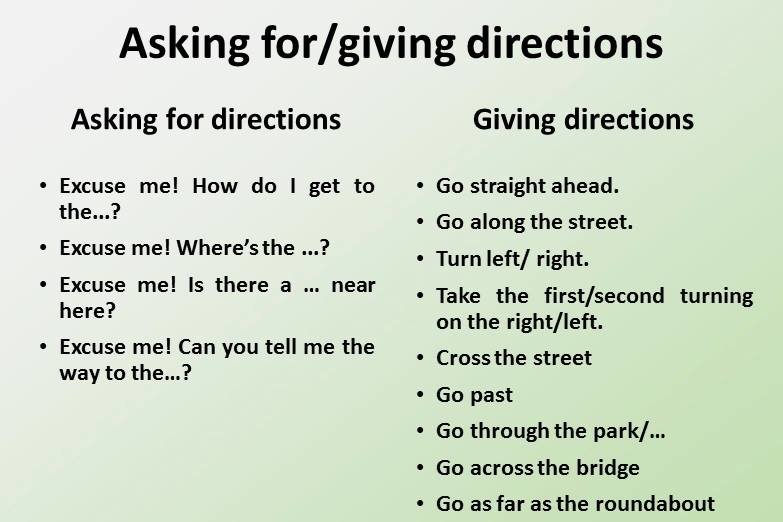

The ability to follow instructions is an important aspect of everyday life. Depending on the setting and context, following instructions results in outcomes that have various degrees of impact. In a clinical setting, following instructions may affect life or death. Within the context of the academic setting, following instructions or failure to do so can impede general learning and development of desired proficiencies. Intuitively, one might think that following instructions requires simply reading instructional text or paying close attention to verbal directions and performing the intended action afterward. This commentary provides a brief overview of the cognitive architecture required for following instructions and will explore social behaviors and mode of instruction as factors further impacting this ability.

Keywords: following instructions, working memory, metacognition, social psychology, teach-back method

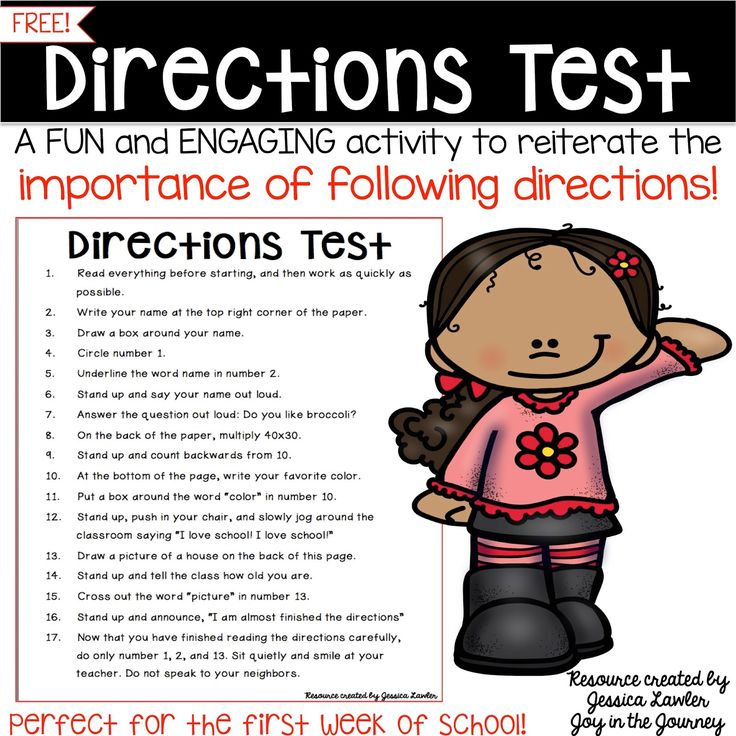

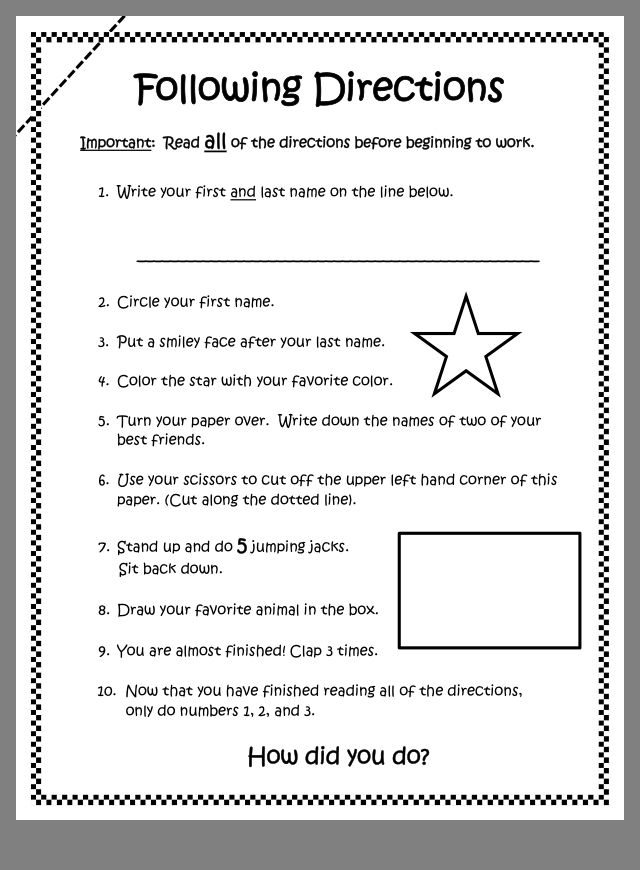

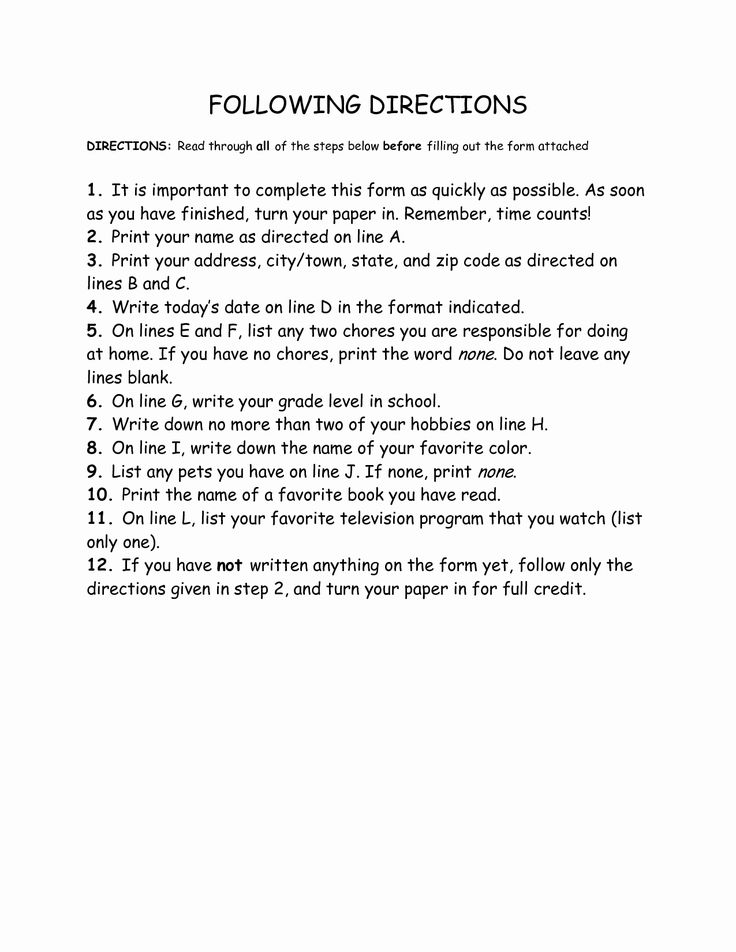

Following instructions is an important ability to practice in everyday life. Within an academic setting, following instructions can influence grades, learning subject matter, and correctly executing skills. In this commentary, we provide an overview of the primary factors that influence the ability of an individual to follow instructions. We translate these findings from the psychological literature into practical guidelines to follow in the educational setting.

Literature on following instructions first surfaced in the late 1970s.1 Researchers observed a subset of housewives who demonstrated a preference to tinker with a new home appliance to get it started or watch a demonstration video on how to set it up rather than read the accompanying instruction manual. Since then, numerous factors that influence following instructions have been investigated including a person’s working memory capacity,2-6 societal rules,7-9 history effects,

7 self-regulatory behavior,10,11 and instruction format. 3,6 Although not completely independent of each other, these factors warrant some individual attention to better understand their implications on following instructions.

3,6 Although not completely independent of each other, these factors warrant some individual attention to better understand their implications on following instructions.

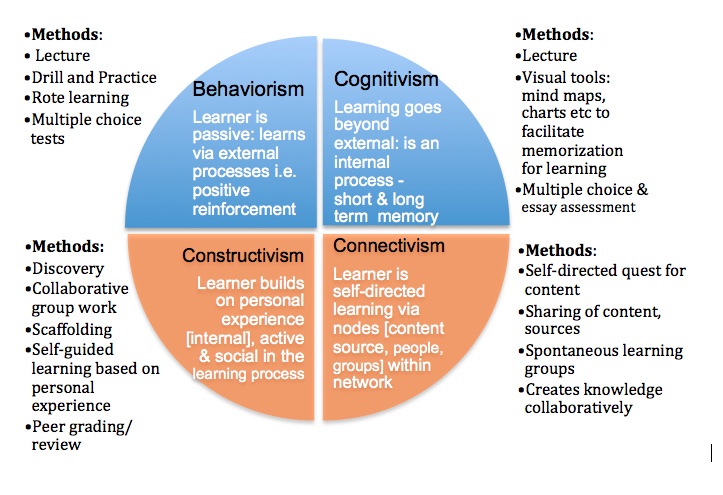

Working Memory and Following Instructions

Working memory is the brain’s workbench, linking perception, attention, and long-term memory.12,13 As an example, in the classroom setting, learners may receive information visually from slides and/or auditorily from instructor narration. However, only items that learners pay attention to within the environment enter their working memory. These items are then processed, resulting in the formation of a mental representation (ie, encoding) that effectively moves from working memory to long-term storage. Thus, working memory performance is an important intermediary between perception and learning. Because working memory capacity is limited,

14 a person’s ability to follow instructions may be impacted if the instructional load is greater than that capacity, ultimately leading to information loss (for more information, explore cognitive load theory15,16). This loss of information may be more pronounced when a task must be performed immediately and the presentation rate of instructions cannot be controlled by the user. Imagine a student named Dennis. During class, Dennis is nervous about an upcoming examination and this emotional state preoccupies his working memory, leading to, in that moment, a lower working memory performance. As a result, when the professor gives verbal instructions for an upcoming assignment, the amount of instructional load supersedes Dennis’ capacity to hold on to those instructions in his working memory. Because he cannot hold on to those instructions, he is less likely to store them in his long-term memory and will not be able to refer to them later when completing the task. To summarize, the ability to hold instructions within working memory is necessary to execute the desired function; thus low working memory performance can compromise a student’s ability to follow instructions.

2 If a student cannot process or hold instructions in working memory, they will probably fail to complete a given task correctly.

This loss of information may be more pronounced when a task must be performed immediately and the presentation rate of instructions cannot be controlled by the user. Imagine a student named Dennis. During class, Dennis is nervous about an upcoming examination and this emotional state preoccupies his working memory, leading to, in that moment, a lower working memory performance. As a result, when the professor gives verbal instructions for an upcoming assignment, the amount of instructional load supersedes Dennis’ capacity to hold on to those instructions in his working memory. Because he cannot hold on to those instructions, he is less likely to store them in his long-term memory and will not be able to refer to them later when completing the task. To summarize, the ability to hold instructions within working memory is necessary to execute the desired function; thus low working memory performance can compromise a student’s ability to follow instructions.

2 If a student cannot process or hold instructions in working memory, they will probably fail to complete a given task correctly.

There are two potential strategies to assist the learner in this situation. One strategy is to have the learner immediately act on the received information.17 A common example of this is the teach-back method, which is a practice of enactment. The practice of enactment has demonstrated greater retention of new information.4,5 This line of research has shown that the accuracy of recalling instructions was increased when immediately after instruction, actions were performed at both the initial learning phase (ie, encoding) and later during recall. The second strategy is to use different forms of instructions (eg, written and verbal), which allows the learner to control the rate of presentation. If the learner can control the rate, they can review the instructions as needed or go at a slower pace to fully encode the instructions.18,19

Societal Rules and History Effects

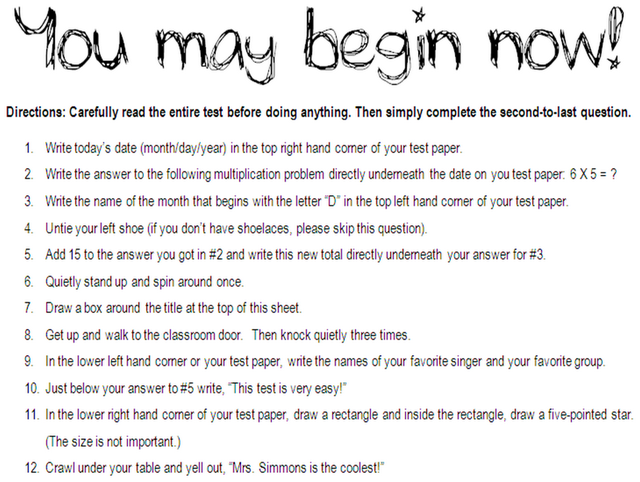

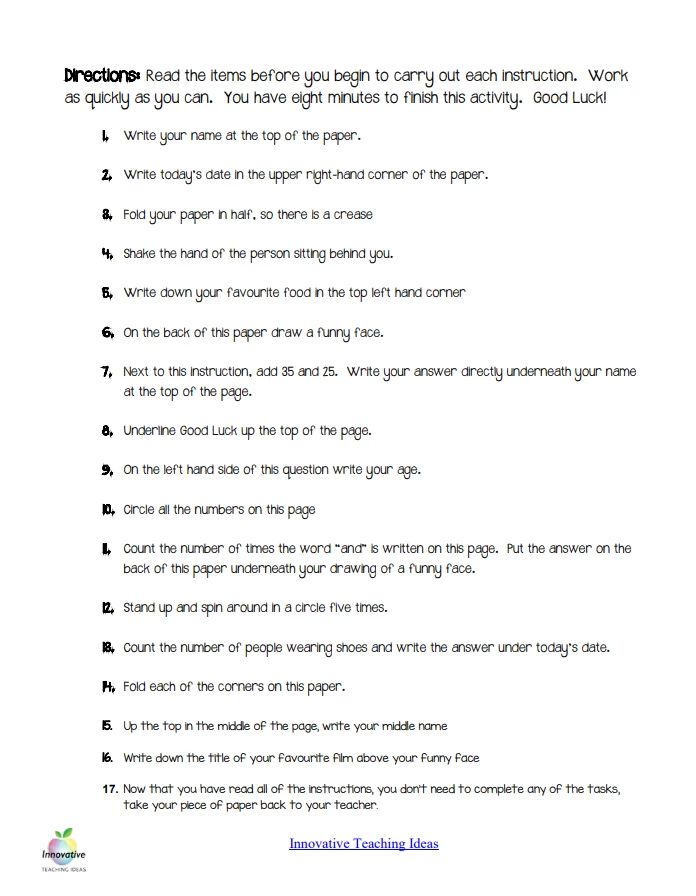

Following instructions is a behavior, and most human behavior depends on social context. Part of the social context is the presence of another individual. The mere presence effect is the phenomenon that human behavior changes when another human is around.9 The presence of another person can make an individual more pliant. Being more or less pliant, or pliance, describes behavior that is controlled by a socially mediated consequence. As an example, if an instructor tells a student to write their name at the top of a test sheet and the student does so to gain the instructor’s approval, this is a ply and the student is being pliant. Imagine a student, Angela. She follows instructions because she feels it is a professional expectation that her mentors and peers have. Angela will be pliant because following instructions has a social consequence. For this to occur, however, the instructor must monitor the completion of the task, possess the ability to impose a consequence, and observe the effect of the consequence on the student. Donadeli and colleagues8 explored the effect of the magnitude of nonverbal consequences, monitoring, and social consequences on instruction following.

Part of the social context is the presence of another individual. The mere presence effect is the phenomenon that human behavior changes when another human is around.9 The presence of another person can make an individual more pliant. Being more or less pliant, or pliance, describes behavior that is controlled by a socially mediated consequence. As an example, if an instructor tells a student to write their name at the top of a test sheet and the student does so to gain the instructor’s approval, this is a ply and the student is being pliant. Imagine a student, Angela. She follows instructions because she feels it is a professional expectation that her mentors and peers have. Angela will be pliant because following instructions has a social consequence. For this to occur, however, the instructor must monitor the completion of the task, possess the ability to impose a consequence, and observe the effect of the consequence on the student. Donadeli and colleagues8 explored the effect of the magnitude of nonverbal consequences, monitoring, and social consequences on instruction following. They observed that the presence of an observer and social reprimand for not following instructions improved the rates at which people followed instructions. This suggests that societal constructs, such as following authority figures and the fear of reprimand, may be drivers in motivating people to follow directions.

They observed that the presence of an observer and social reprimand for not following instructions improved the rates at which people followed instructions. This suggests that societal constructs, such as following authority figures and the fear of reprimand, may be drivers in motivating people to follow directions.

There are two possible ways to address societal effects on following instructions. The first way is to establish an expectation of professionalism by explaining why instruction following is important. This would be consistent with aspects of social identity theory.20,21 The second way is to create the fear of reprimand. In this case, faculty members hold students responsible for following the rules. This could be with respect to assignment formatting, assignment deadlines, or other aspects that might be tied to a penalty.

Following instructions is affected by the presence of another person even if there is no history of reinforcement for such behavior, suggesting that instructional control may be strengthened by social contingencies. 7,8 However, societal rules can lead to history effects. If students never receive feedback on or consequences for their inability to follow instructions, history effects dictate they will continue that behavior. Now imagine a student named Amber. Amber wrote down the instructions during class but did not follow them because she generally does well on her assignments despite not completely following the instructions. As such, she abstained from following the rules because a consequence was not associated with not following them.

7,8 However, societal rules can lead to history effects. If students never receive feedback on or consequences for their inability to follow instructions, history effects dictate they will continue that behavior. Now imagine a student named Amber. Amber wrote down the instructions during class but did not follow them because she generally does well on her assignments despite not completely following the instructions. As such, she abstained from following the rules because a consequence was not associated with not following them.

Metacognition and Self-regulation

Following instructions also depends on self-regulation, ie, a person’s awareness of their own behavior to act in a manner that optimizes their best long-term interests.22 To do so, an individual must be aware of their own thoughts and actions. This awareness plays a role in metacognitive monitoring, or a person’s monitoring of their own thoughts and behaviors.

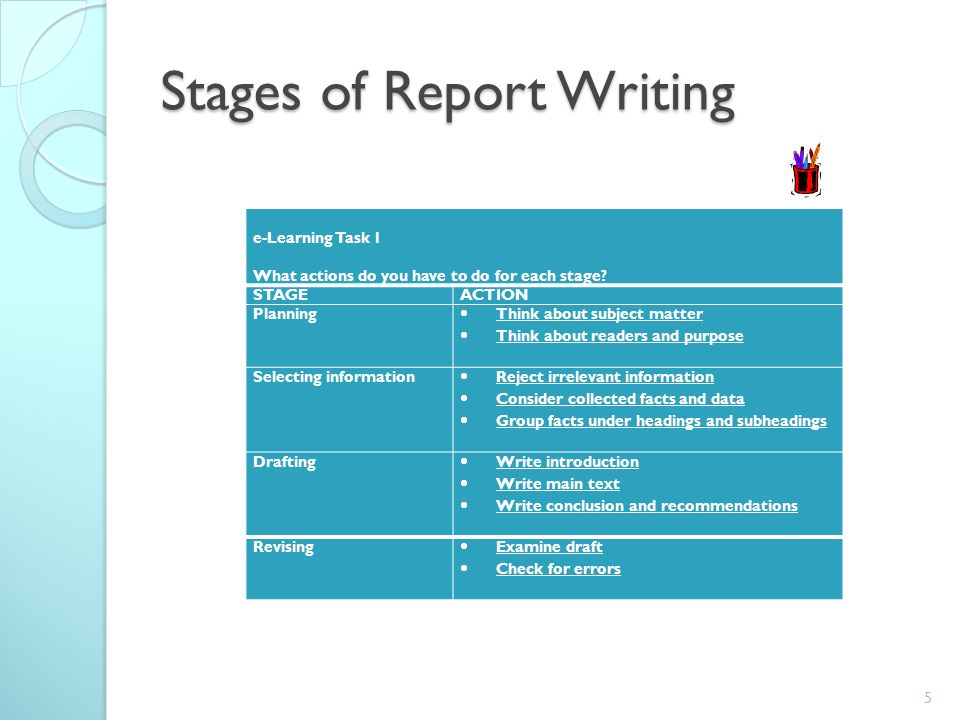

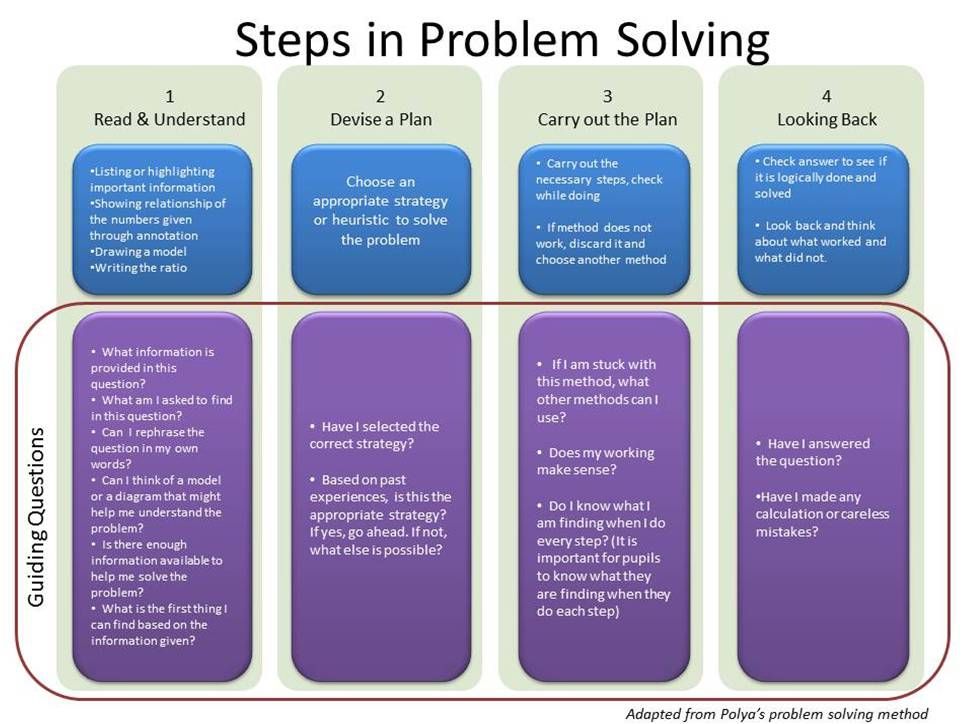

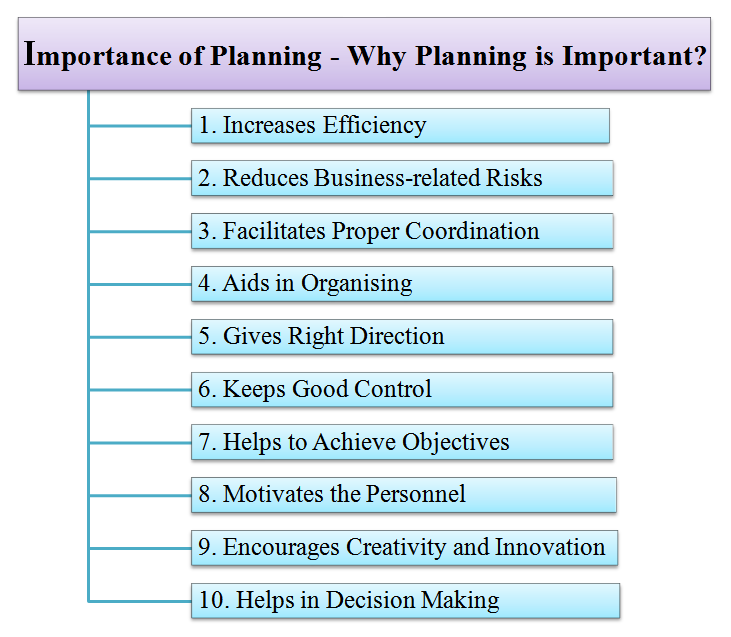

Metacognition has been described as thinking about thinking. 23 At its core, it is about planning, monitoring making progress, and evaluating the completion of a process. For instance, if a student is asked to conduct a journal club meeting, the planning stage would involve gaining an understanding of what is required to successfully complete a journal club meeting. This could include time needed for completion or where to look for an article. The monitoring phase is the awareness to review the article and pull out key information. The final part, evaluation, involves checking the work to determine whether goals were met.

23 At its core, it is about planning, monitoring making progress, and evaluating the completion of a process. For instance, if a student is asked to conduct a journal club meeting, the planning stage would involve gaining an understanding of what is required to successfully complete a journal club meeting. This could include time needed for completion or where to look for an article. The monitoring phase is the awareness to review the article and pull out key information. The final part, evaluation, involves checking the work to determine whether goals were met.

Imagine a student named Craig. Craig wrote down instructions for an assignment, but after completing the assignment, he did not review the instructions to ensure he followed them correctly. He failed to monitor his progress. As such, the ability to be metacognitively aware can be a key piece in following instructions. In this case, individuals may not follow instructions because they are poor monitors of their learning. 22,24-28 Students may not adequately plan before tackling their assignment, such as by reading instructions beforehand. Next, they may not monitor their progress during completion of the assignment. And finally, once students think they have completed the task, they may not go back and read the instructions to ensure they have fulfilled all expectations. To help them with this and other aspects of instruction, students may need to use accountability (societal rules) as a primary source of motivation. Without accountability, students may not follow instructions, thus perpetuating poor metacognitive skills, leading to unawareness of what they know, what they do not know, and the process to correct errors. A strategy may be the use of checklists to help students monitor their thoughts during a process (see Tanner29 and Medina and colleagues30 for a review of methods to develop metacognition).

22,24-28 Students may not adequately plan before tackling their assignment, such as by reading instructions beforehand. Next, they may not monitor their progress during completion of the assignment. And finally, once students think they have completed the task, they may not go back and read the instructions to ensure they have fulfilled all expectations. To help them with this and other aspects of instruction, students may need to use accountability (societal rules) as a primary source of motivation. Without accountability, students may not follow instructions, thus perpetuating poor metacognitive skills, leading to unawareness of what they know, what they do not know, and the process to correct errors. A strategy may be the use of checklists to help students monitor their thoughts during a process (see Tanner29 and Medina and colleagues30 for a review of methods to develop metacognition).

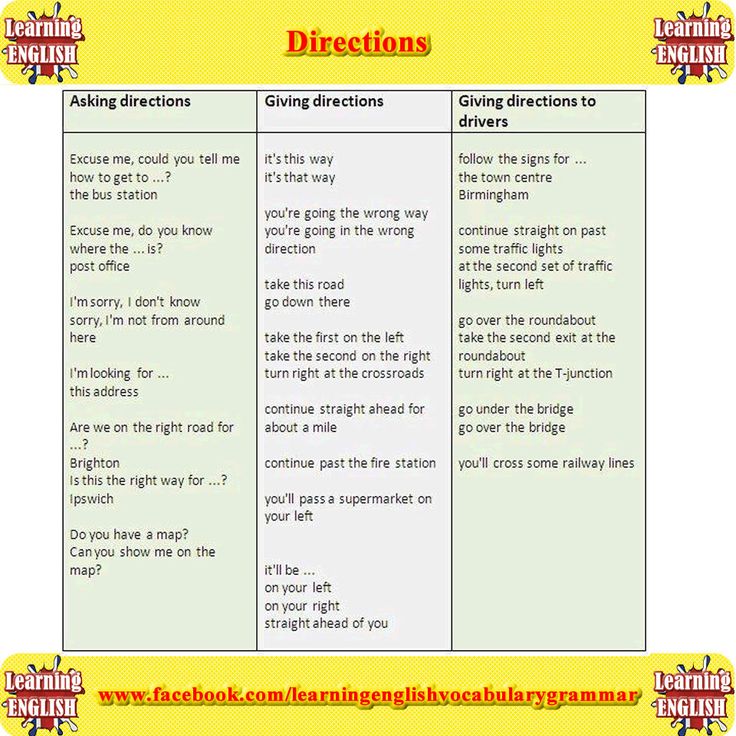

Verbal vs Written Instructions

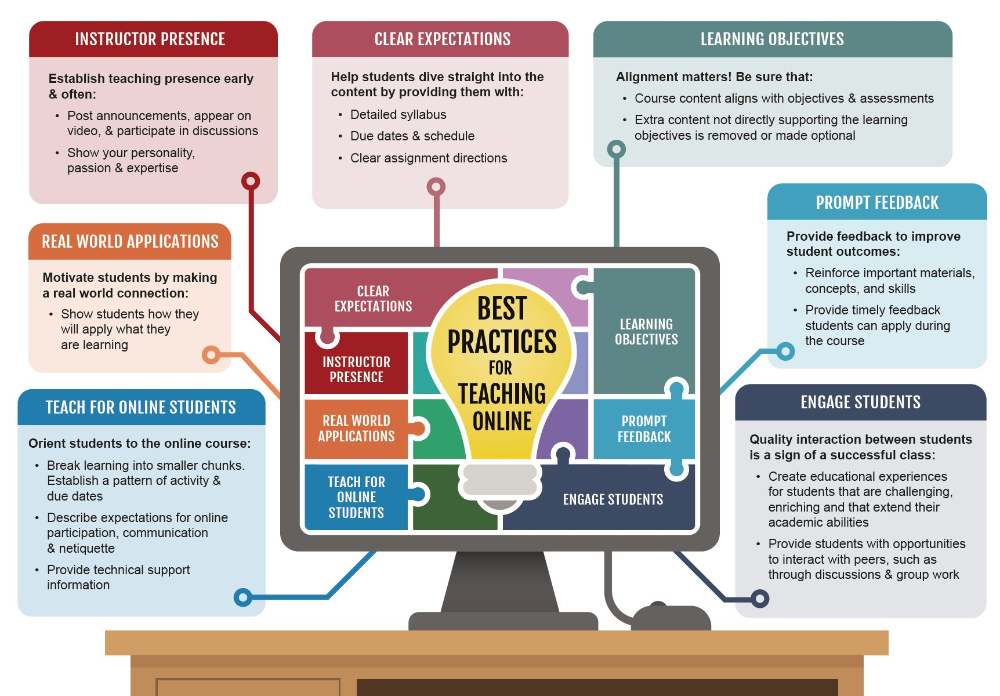

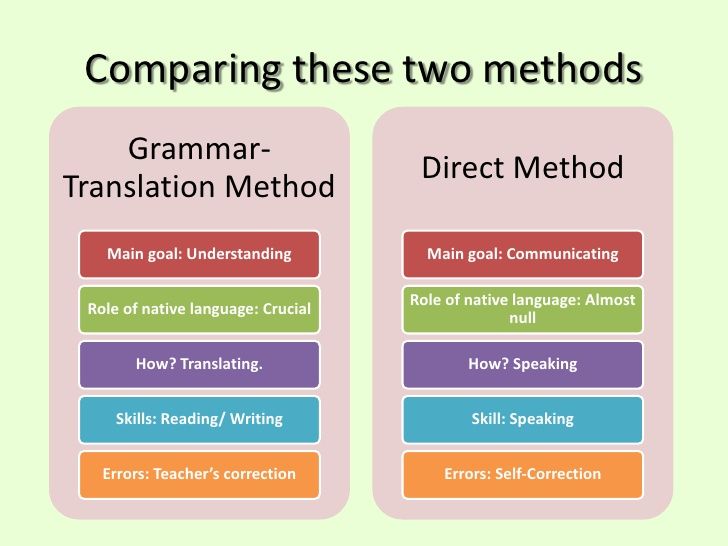

When examining best practices for conveying instructions to learners, the instructor should consider whether instructions are best retained and applied if received in a verbal versus a written format. To date, no published studies have examined whether one format offers greater benefit over another; however, one study explored both formats in relation to working memory.6

To date, no published studies have examined whether one format offers greater benefit over another; however, one study explored both formats in relation to working memory.6

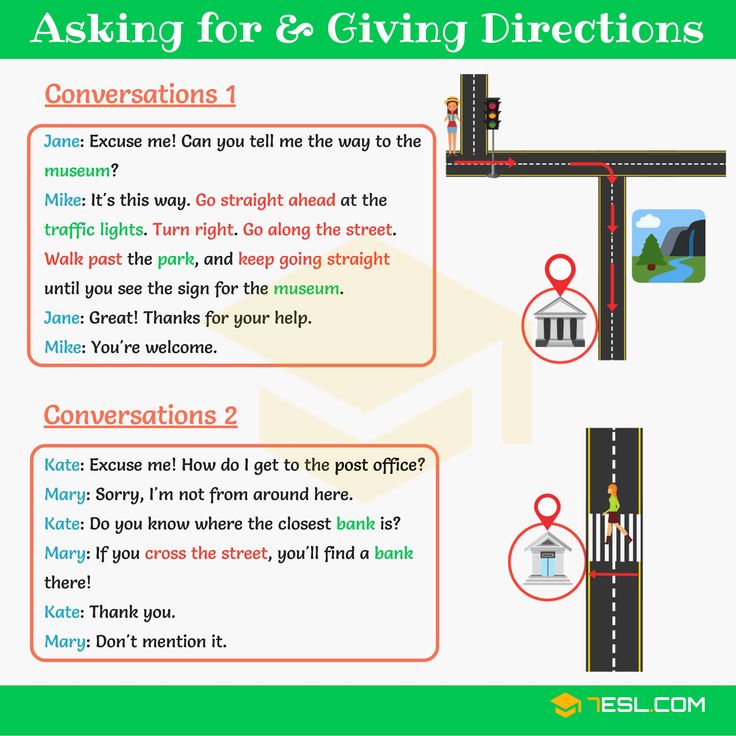

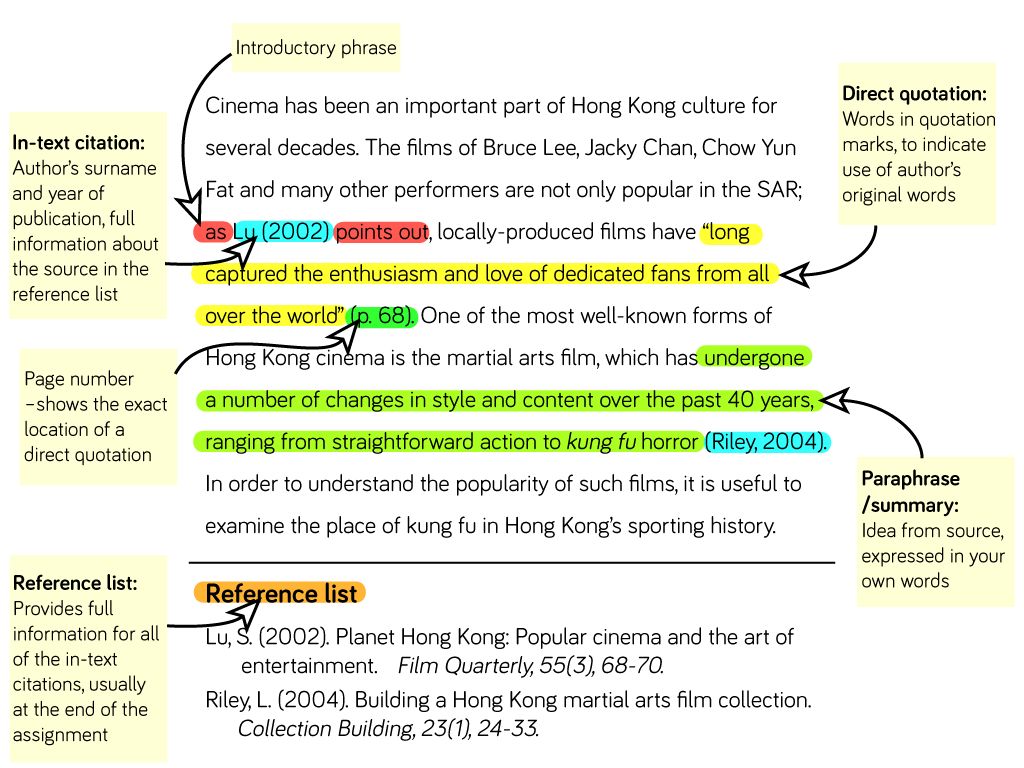

Written instructions are efficient because large amounts of detail can be provided that students can read rapidly. Thus, step-by-step manuals can be found for almost all electronic devices. While there is a large body of literature describing the mechanics of how we read, there are some important points to underscore.6 When reading and following instructions, a person will act in the same sequence in which action items are presented in the text. In the television show MASH (season 1, episode 20), one of the characters was instructed to “…cut wires leading to the clockwork fuse at the head, but first remove the fuse.” He proceeded to cut the wires before removing the fuses. He acted in the same sequence in which the instructions were presented but failed to follow the actual instructions. This raises an important point: individuals are more likely to remember instructions when the order is consistent with how events occur. 6 Writing instructions according to the sequence of actions the reader needs to take may lead to better results. For example, “do A before doing B’ is a superior form of wording instructions than stating, “before doing A, do B,” as illustrated in the above scenario.

6 Writing instructions according to the sequence of actions the reader needs to take may lead to better results. For example, “do A before doing B’ is a superior form of wording instructions than stating, “before doing A, do B,” as illustrated in the above scenario.

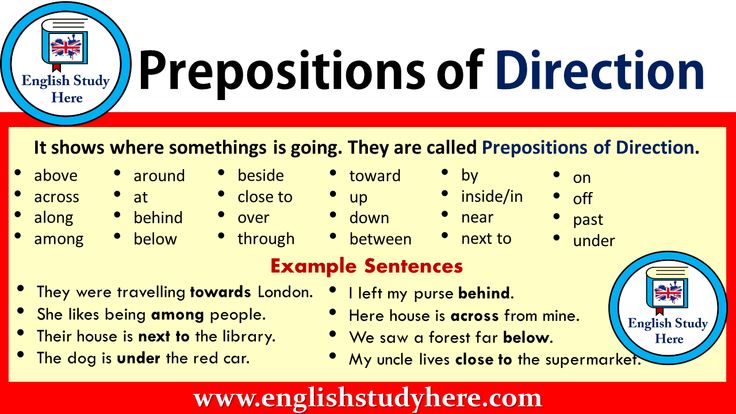

Spoken instructions are advantageous in face-to-face interactions (eg, within the classroom). Spoken instructions are processed through the phonological loop, a component of working memory focused on verbal information, which is more flexible and convenient. Intrinsically, listening requires less effort than reading. Spoken words can also be paired with visual aids to guide action, such as in measuring blood pressure or administering an immunization.6 Remarkably, individuals cannot read and follow visual objects at the same time. Combining text with pictures can be more taxing to working memory than combining spoken words and visuals. A drawback associated with spoken words is the rate of presentation. While the speed at which text is read can be controlled by the end user, the instructor’s speed of speech cannot. The phonological loop mediates the ability to hold and process auditory information.13,31 Items (bits of information) in the phonological store can rapidly decay, and because items are usually chained in such a way that an item primes the next item,31 one lost step can lead to the loss of all subsequent steps (eg, if a student cannot remember step 3, she is unlikely to recall any step after that). To prevent this loss, people tend to “rehearse” following instructions by repeating the instructions to themselves.3 Access to both written instructions and verbal instructions may prove beneficial, as written instructions can be referred to if any verbal instruction is missed.

While the speed at which text is read can be controlled by the end user, the instructor’s speed of speech cannot. The phonological loop mediates the ability to hold and process auditory information.13,31 Items (bits of information) in the phonological store can rapidly decay, and because items are usually chained in such a way that an item primes the next item,31 one lost step can lead to the loss of all subsequent steps (eg, if a student cannot remember step 3, she is unlikely to recall any step after that). To prevent this loss, people tend to “rehearse” following instructions by repeating the instructions to themselves.3 Access to both written instructions and verbal instructions may prove beneficial, as written instructions can be referred to if any verbal instruction is missed.

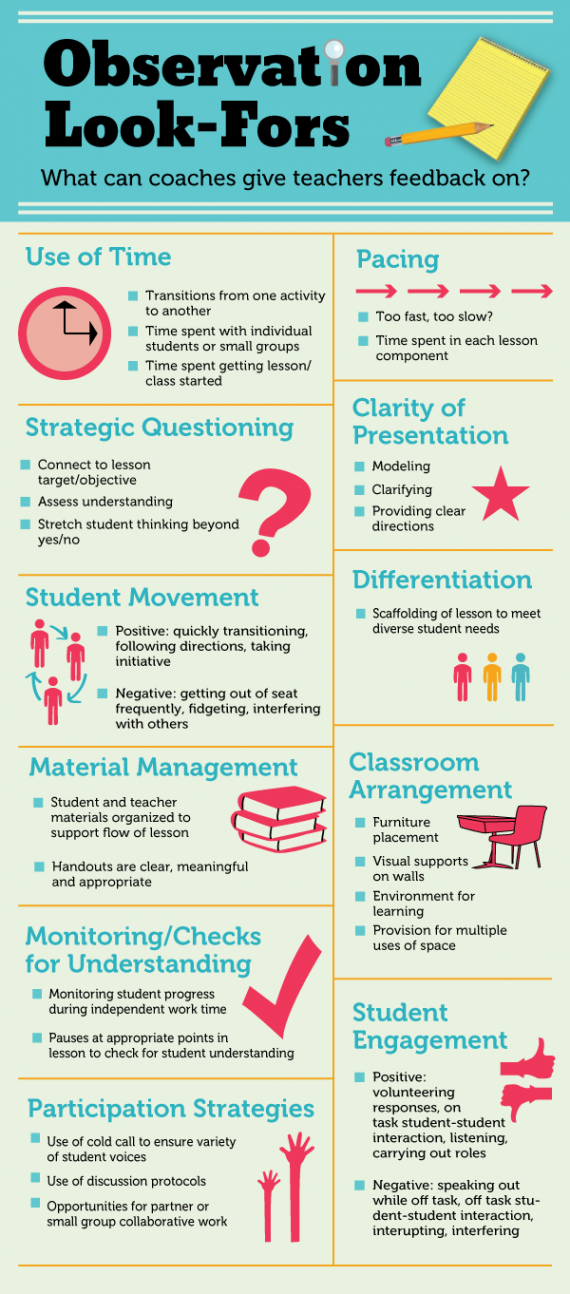

Several factors can impact a student’s ability to follow instructions. Recommendations to increase the probability of learners following instructions are available within the literature (). While these modalities may not guarantee success, these recommendations should increase the probability that most students will follow instructions. Although we cannot extrapolate from current literature whether one mode of instruction delivery is preferred over another, we can apply some of these findings to pharmacy students in a learning environment where instructions are used to guide the completion of deliverables. The first thing the instructor can do is provide both written and verbal instructions. These instructions should be concise, written in student-friendly language, and given in order of operation (ie, step A then step B). Students can read (and reread the written instructions), which should minimize errors resulting from not paying attention or insufficient working memory. Although distracted when verbal instructions were given, a student can review written instructions in a self-paced manner, thus reducing cognitive load and increasing the probability of remembering them.

While these modalities may not guarantee success, these recommendations should increase the probability that most students will follow instructions. Although we cannot extrapolate from current literature whether one mode of instruction delivery is preferred over another, we can apply some of these findings to pharmacy students in a learning environment where instructions are used to guide the completion of deliverables. The first thing the instructor can do is provide both written and verbal instructions. These instructions should be concise, written in student-friendly language, and given in order of operation (ie, step A then step B). Students can read (and reread the written instructions), which should minimize errors resulting from not paying attention or insufficient working memory. Although distracted when verbal instructions were given, a student can review written instructions in a self-paced manner, thus reducing cognitive load and increasing the probability of remembering them. The instructor could then employ metacognitive monitoring and assess the student’s understanding of the instructions by including a checklist within the assignment, ie, a strategy to help Craig monitor his learning and check his work (much like journals have checklists for authors). Finally, the instructor should penalize students for not following the instructions thereby using the social context to reinforce their need to follow instructions. Amber benefits by learning there are consequences for not following instructions. For Dennis and Craig, the threat of punishment in the form of lost points may motivate them to review the instructions to ensure they have done their work correctly, a process which can improve their attention (Dennis) and metacognitive monitoring (Craig).

The instructor could then employ metacognitive monitoring and assess the student’s understanding of the instructions by including a checklist within the assignment, ie, a strategy to help Craig monitor his learning and check his work (much like journals have checklists for authors). Finally, the instructor should penalize students for not following the instructions thereby using the social context to reinforce their need to follow instructions. Amber benefits by learning there are consequences for not following instructions. For Dennis and Craig, the threat of punishment in the form of lost points may motivate them to review the instructions to ensure they have done their work correctly, a process which can improve their attention (Dennis) and metacognitive monitoring (Craig).

Table 1.

Common Errors in Following Instructions and Recommendations to Enhance the Probability of Instruction Following

Open in a separate window

1. Wright P, Wilcox P. Following instructions: an exploratory trisection of imperatives. In: Levelt WJM, FLores d' Arcais GB, eds. Studies in the Perception of Language. New York: Wiley;1978. [Google Scholar]

In: Levelt WJM, FLores d' Arcais GB, eds. Studies in the Perception of Language. New York: Wiley;1978. [Google Scholar]

2. Bergman-Nutley S, Klingberg T. Effect of working memory training on working memory, arithmetic and following instructions. Psychol Res. 2014;78(6):869-877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Yang T-x, Allen RJ, Gathercole SE. Examining the role of working memory resources in following spoken instructions. J Cogn Psychol. 2016;28(2):186-198. [Google Scholar]

4. Jaroslawska AJ, Gathercole SE, Allen RJ, Holmes J. Following instructions from working memory: why does action at encoding and recall help? Memory Cogn. 2016;44(8):1183-1191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Jaroslawska AJ, Gathercole SE, Logie MR, Holmes J. Following instructions in a virtual school: does working memory play a role? Memory Cogn. 2016;44(4):580-589. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Yang T. The role of working memory in following instructions. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing - Dissertation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

ProQuest Dissertations Publishing - Dissertation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

7. Kroger-Costa A, Abreu-Rodrigues J. Effects of historical and social variables on instruction following. Psychol Record. 2012;62(4):691-706. [Google Scholar]

8. Donadeli JM, Strapasson BA. Effects of monitoring and social peprimands on instruction-following in undergraduate students. Psychol Record. 2015;65(1):177-188. [Google Scholar]

9. Guerin B. Mere presence effects in humans: a review. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22(1):38-77. [Google Scholar]

10. de Bruin ABH, van Gog T. Improving self-monitoring and self-regulation: from cognitive psychology to the classroom. Learn Instruct. 2012;22(4):245-252. [Google Scholar]

11. Bruin ABH, Dunlosky J, Cavalcanti RB. Monitoring and regulation of learning in medical education: the need for predictive cues. Med Educ. 2017;51(6):575-584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Baddeley A. Working memory. Current Biol. 2010;20(4):R136-R140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Cowan N. Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educ Psychol Rev. 2014;26(2):197-223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Cowan N. The magical number 4 in short-term memory: a reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behav Brain Sci. 2001;24(1):87-114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Van Merriënboer JJG, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory in health professional education: design principles and strategies: cognitive load theory. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):85-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Young JQ, Van Merrienboer J, Durning S, Ten Cate O. Cognitive load theory: implications for medical education: AMEE Guide No. 86. Med Teach. 2014;36(5):371-384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Allen RJ, Waterman AH. How does enactment affect the ability to follow instructions in working memory? Memory Cogn. 2015;43(3):555-561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Grech V. The application of the Mayer multimedia learning theory to medical PowerPoint slide show presentations. J Visual Comm Med. 2018;41(1):36-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Visual Comm Med. 2018;41(1):36-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Mayer RE. Applying the science of learning: evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. Am Psychol. 2008;63(8):760-769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Jha V, Brockbank S, Roberts T. A framework for understanding lapses in professionalism among medical students: applying the theory of planned behavior to fitness to practice cases. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1622-1627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Burford B. Group processes in medical education: learning from social identity theory. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):143-152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Sitzmann T, Ely K. A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educational attainment: what we know and where we need to go. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(3):421-442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Flavell JH. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: a new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. Am Psychol. 1979;34(10):906-911. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

24. Dunning D, Heath C, Suls JM. Flawed self-assessment: implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2004;5(3):69-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Kornell N, Bjork RA. The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychonom Bull Rev. 2007;14(2):219-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Dunlosky J, Lipko AR. Metacomprehension: a brief history and how to improve its accuracy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16(4):228-232. [Google Scholar]

27. Dunlosky J, Rawson KA. Overconfidence produces underachievement: inaccurate self evaluations undermine students’ learning and retention. Learn Instruct. 2012;22(4):271-280. [Google Scholar]

28. Bjork RA, Dunlosky J, Kornell N. Self-regulated learning: beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Ann Rev Psychol. 2013;64(1):417-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Tanner KD. Promoting student metacognition. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2012;11(2):113-120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Medina MS, Castleberry AN, Persky AM. Strategies for improving learner metacognition in health professional education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(4):78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Medina MS, Castleberry AN, Persky AM. Strategies for improving learner metacognition in health professional education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(4):78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Baddeley AD, Larsen JD. The phonological loop unmasked? a comment on the evidence for a "perceptual-gestural" alternative. Quart J Exp Psychol. 2007;60(4):497-504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

How To Help Kids Develop This Important Skill

Does it sometimes feel like your child isn’t the greatest at following directions? Or the older they get, the more they want to do everything their way, regardless of the instructions given to them?

Before you start thinking you’re doing something wrong, it’s important to know that you’re not alone. The truth is sometimes our kids are not the most cooperative, and following our instructions isn’t always high on their priority list.

In this article, we’ve compiled a list of effective strategies you can try at home to help them follow directions. Let’s get started!

Let’s get started!

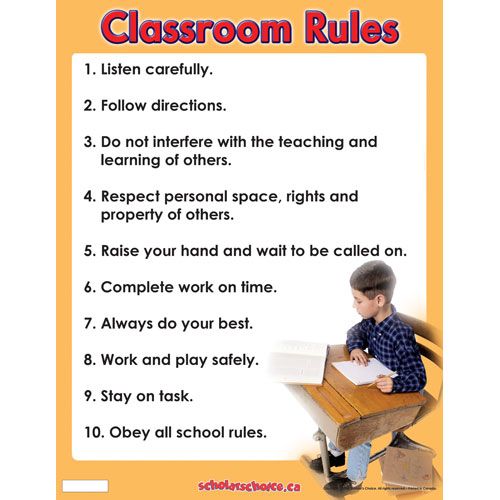

Why Is Following Directions Important?

The ability to follow directions is a basic life skill that will serve your child well both now and in the future.

When you look at the various aspects of our everyday lives and daily interactions with others (like following the user manual’s instructions for a new gadget), you realize how this skill actually allows us to accomplish so much.

For kids, in particular, there are a couple of key benefits to following directions.

Children Can Function In Different Environments

As much as we’d like to keep them all to ourselves, our children aren’t going to stay at home for the rest of their lives.

They are going to go to school, take tests, participate in sports, go to camps, visit a friend’s house, etc. Learning to follow directions will help them function effectively across these different environments.

It Keeps Kids Safe

You never know when an emergency can occur. Whether at home, school, or the local park, the skill of following directions may save your child’s life one day.

In addition to the above, helping your child learn how to follow directions can:

- Maintain order at home

- Impact their ability to complete tasks and reach the desired purpose

- Learn new skills

- Keep them calm and feeling secure as they know what comes next

With these examples, we hope you understand that following directions is a beneficial skill your child can use in various aspects of life.

The Age Factor

Before discussing the different strategies you can try at home, it’s important to mention the role age plays in our children’s ability to follow directions.

0 – 24 Months

Trying to get a newborn to follow directions is unrealistic. However, as you respond to their cues (like hungry and tired cries) and they respond to yours, it helps lay a solid foundation for cooperative interactions.

As children enter the toddler stage, they are usually able to begin following simple, one-step instructions, such as, “Wave bye-bye to Laura!” or, “Give mommy the book. ” Keep in mind that attention spans at this age are super short, so be clear and make eye contact with your child.

” Keep in mind that attention spans at this age are super short, so be clear and make eye contact with your child.

Children seek lots of adult approval at this stage, and making your tone of voice enthusiastic and appreciative can help influence how your toddler responds.

Giving positive feedback is also a great way to encourage them. So, if they don’t do as you say, instead of responding negatively, focus on what they should be doing.

2 – 4 Years

At the preschool level, most children can understand and follow two-step instructions. For example, “Put your toys in the box, then place the box in the corner.”

If your child hasn’t yet developed this ability, don’t worry. At this stage, kids are still learning the valuable skill of listening and paying attention to the details in the information given.

To help your child process information and instructions, you can continue to give them lots of positive reinforcement.

In addition, remember to also give them simple choices. For example, “Get your green shirt out of the bottom drawer” is more challenging than pointing to a visible shirt and asking them to get it.

For example, “Get your green shirt out of the bottom drawer” is more challenging than pointing to a visible shirt and asking them to get it.

4 – 6 Years

At this stage, your child’s vocabulary and listening skills have improved. This can make following directions a bit easier.

Most kindergarteners can follow three- or four-step instructions. They may also ask questions to seek clarification.

To help your child continue to improve this skill, you can:

- Break complicated directions into smaller steps

- Give instructions in context (for example, if your child is learning to draw, give instructions while they are busy with the activity)

- Keep a fun and playful tone while giving directions to help motivate them

Following directions is a skill that your child will use for the rest of their life. So, here are seven strategies to help them improve.

Tips To Encourage Following Directions

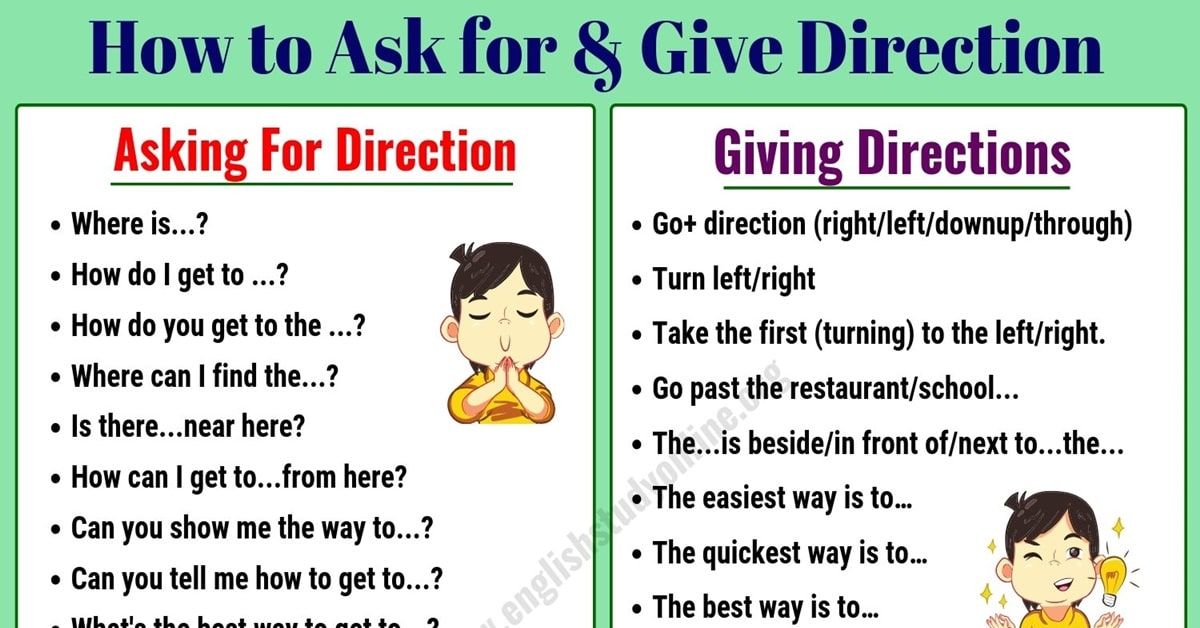

1) Get Your Child’s Attention

Before giving your child directions, it’s essential that you have their full attention. Otherwise, the activity will feel impossible for both you and them.

Otherwise, the activity will feel impossible for both you and them.

You can gain their attention by simply asking for it — e.g., “Look toward me now. I need to tell you something.” Getting down to your child’s level can also help.

2) Be Clear

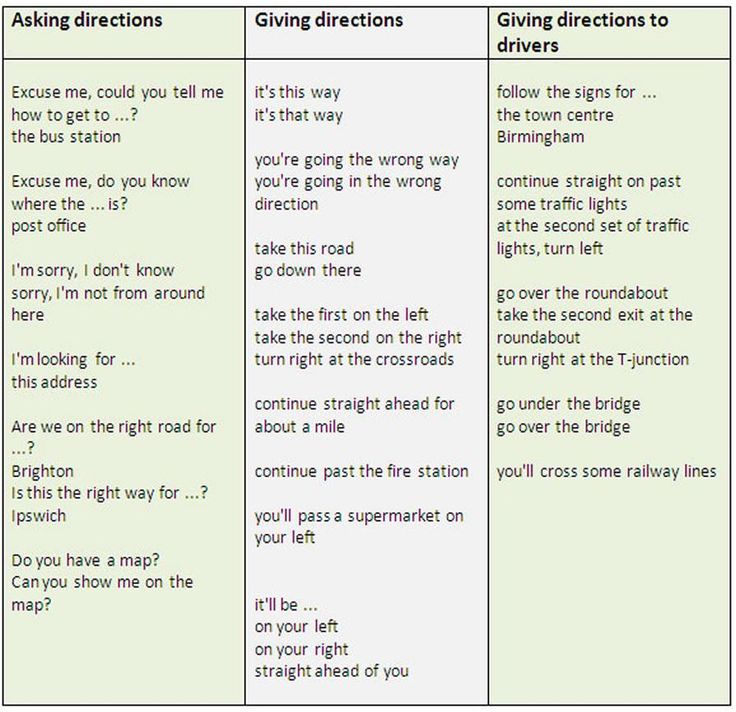

One of the key components for helping your child learn to follow directions is being clear on what you need them to do. To achieve this, be direct and use simple language.

For instance, “It’s time to jump into bed,” is much better than, “You need to sleep early. We have a long day ahead tomorrow, and it would be great for you to get enough rest.”

You might assume that the latter will help a child become more understanding. However, giving too many details may lead to a child getting “lost” in the information you’re giving them. It’s best to say what’s necessary and leave the rest out.

3) Focus On One Instruction At A Time

Going along with the previous point, we sometimes make the mistake of giving children too many instructions at one time.

For example, we might say, “Pick up your toys, place them in the toy box, wash your hands, and then tell your brother it’s time to eat.”

With this many instructions, it can be hard for your child to decipher what they’re actually supposed to do. That’s why, whenever possible, it’s best to give one instruction at a time or group them together in a way that makes sense.

Using the example above, you could hand your child a toy and ask them to put it in the toy box. Then hand them another one and do the same. When this is easy for your child, you can then group instructions together by saying, “Pick up your stuffed lion and put it in the toy box.”

Then you may want to move on to even more complicated directions. For example, you may have them pick up all the toys on the floor and put them in the toy box. Finally, once they’ve completed that, ask them to wash their hands and tell their brother that it’s time to eat.

4) Number Your Instructions

This tip is very effective if you’re going to be grouping your instructions into manageable tasks.

Simply number the directions you’re giving your child.

For example, start with, “I need you to do three things right now,” or “Pay attention. There are four things I need you to do.” You can also use ordinal numbers such as “first,” “second,” “third,” and so forth to label each task.

By using this technique and verbiage, you can help your child become aware that there is more than one thing being asked, and they can distinguish between and keep track of to-dos on their list.

While numbering your instructions helps make things clear, it’s still important to keep the list relatively short. Because people can typically only hold up to four different things in their working memory, we recommend giving no more than four instructions at a time.

5) Help Your Child Visualize The Instructions

Giving visual cues can be very effective in helping your child understand what you need them to do. To use this tactic, demonstrate a task and then ask them to follow your example.

For example, “Watch me carefully. See how I’m arranging this plate, fork, and spoon? I need you to set the rest of the table just like this.”

This “me first, now you” approach allows your child to visualize exactly what you want them to do before giving it a go. It can also be a very effective strategy to use with children who have language processing challenges.

6) Allow Your Child To Process The Information

Do you know how you sometimes have to pause and think through information you’ve just read or heard? Kids need that, too, especially when they’re learning to follow directions.

After giving them instructions, allow a few seconds to pass, which may help the information sink in.

Doing this may also help your child learn to listen the first time, rather than requiring you to repeat yourself. However, if they don’t do as you say or seem confused, it’s OK to repeat the instructions.

7) Minimize Distractions

Children have short attention spans. That’s why it’s essential to keep their attention when you have it.

That’s why it’s essential to keep their attention when you have it.

If the TV is on in the background or they’re busy playing games, it’s going to be challenging for them to follow through on any of your instructions. Turn the TV off. Have them put their game or anything else they’re busy with down and give you their full attention.

Another essential component is to give your child your full attention as well. This may help them realize that the information is important.

8) Focus On Tone Of Voice

You know the phrase, “It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it”? Different people can recite the same words, but the differences in tone, volume, pace, and pitch can completely change the message.

When it comes to helping children follow directions, it’s much more effective to speak in a calm, clear, and even tone. Remember that you want your child to focus only on the instructions and not the volume or tone.

9) Don’t Ask, Tell

Sometimes children are in the mood for a power struggle and phrasing the directions in a way that it seems like there’s room for negotiation will not help you.

If you give directions such as, “Would you pick up your toys, please?” It may give your child the impression that they don’t have to do it.

Instead, change the wording to, “It’s time to pick up your toys,” as this makes it clear that they don’t have a choice.

10) Offer Praise

Positive reinforcement is a great way to help your child feel good about following your instructions. So, clap your hands, cheer them on, give them a high five, or pat them on the back to show that you’re happy about what they’ve just done.

The more they realize how happy you are, the better they’ll feel about listening to your instructions, and the easier it will be for them to continue following your directions in the future.

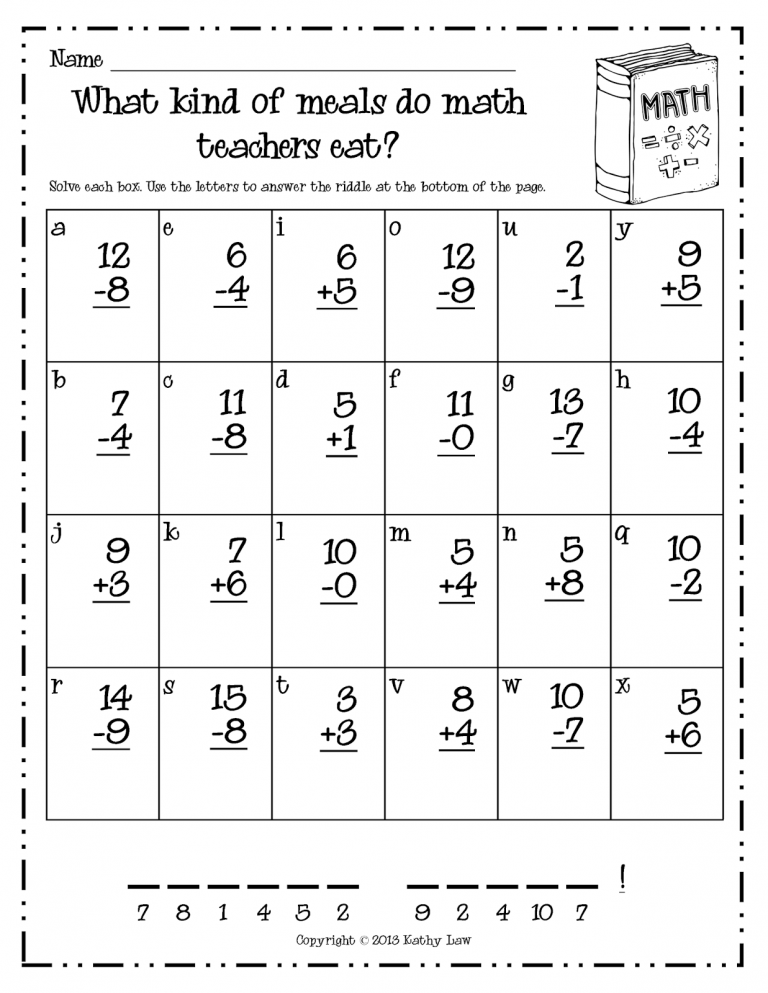

Activities To Help With Following Directions

Plenty of games and activities can help you encourage your child to get into the habit of following directions. These include:

- Follow The Leader

- Simon Says

- I Spy

One of our favorite activities to help develop this skill is what we call the “playful instructions game. ” This is where you give children instructions by adding playful elements.

” This is where you give children instructions by adding playful elements.

For example, ask your child to jump as high as possible and then make a silly face. For older kids, you can even add more playful instructions (stick your tongue out, wiggle your nose, etc.).

This game can be incorporated into your regular routines — jump out of bed, tiptoe to the bathroom, and grab a toothbrush. Adding a playful element can make mundane routines much more fun.

In addition to the well-known games above, we’ve included a few more activities to help your child learn to follow instructions.

1) Red Light, Green Light

To prepare for this game, clearly define the playing area and mark the start and finish lines with a strip of tape on the floor (or ground if you’re outside). Safety comes first, so feel free to push things out of the way if you need a little more room to move around.

To begin, have all players stand on the starting line. Then, when you say “Green Light,” everyone moves toward the finish line. But, as soon as you say “Red Light,” everyone needs to immediately stop.

But, as soon as you say “Red Light,” everyone needs to immediately stop.

Anyone who is caught moving when “Red Light” is called out has to go back to the starting line. The first person to make it across the finish line wins the game!

This listening and moving game uses simple instructions to encourage children to follow directions — and have some fun while doing so!

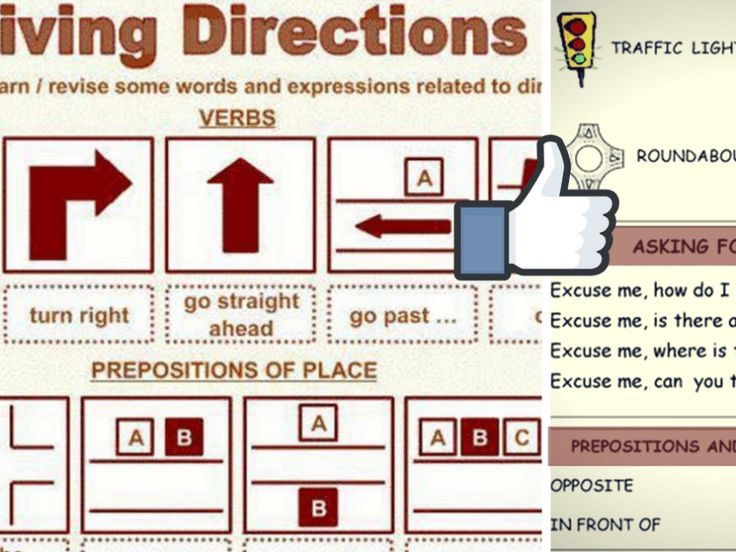

2) Grid Game

The goal of this activity is simple: Make your way through a grid by following instructions.

Start by creating a numbered grid on your floor. The size of grid you create will depend on the space you have available. But whether you create a 4×4, 5×5, or 6×6 grid, make sure all the squares are the same size.

(You can either use your feet — one foot in front of the other — to measure each square, or you can use an actual ruler. It’s totally up to you!)

The type of floor you have will also dictate the type of tape you can use to create your grid, but masking tape usually works well for most floors because it easily comes off without causing damage.

To play this game, have your child stand in the first square and then follow your instructions to move throughout the grid.

Your instructions could look something like this:

- Take two steps forward.

- Take one step backward.

- Take two steps to your right.

- Take three steps to the left.

As they move this way and that within the defined space, it’s great practice because they have to switch gears quickly and listen carefully to the directions you’re giving.

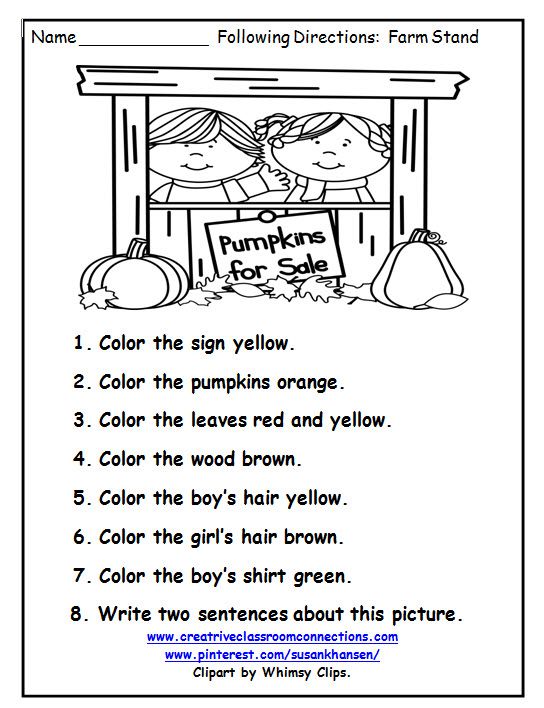

3) Visual Directions

For this activity, simply make cards using your child’s routine. For example, let’s say your child’s bedtime routine is the following:

- Take a bath

- Put on pajamas

- Brush teeth

- Get into bed

- Read a book

- Sleep

Print out images of a bathtub, a toothbrush, pajamas, a bed, a book, and a child sleeping to represent each part of the routine.

Next, stick each of these pictures on a numbered index card. Then, whenever it’s time for bed, your child can just grab their card stack and follow the instructions.

Then, whenever it’s time for bed, your child can just grab their card stack and follow the instructions.

This can work for any routine, so feel free to adapt it as necessary. It’s also a helpful tactic if you have a nonverbal child.

Using cards as a method of explaining instructions can eliminate unnecessary confusion, promote confidence in daily activities, and increase cooperation between a parent and a child.

Things To Consider When Giving Directions

1) Avoid Empty Threats

Sometimes parenting little humans can get overwhelming, especially when they are in the mood to be defiant.

This may lead to making impulsive threats, like, “If you don’t set the table right now, you’re going to be sorry!” Or, “I’m giving you two minutes to clean up. If this isn’t done by the time I get back, you’re going to be in big trouble!”

The problem with making such statements is that they tend to shut down communication and lead to power struggles. While threats may give you short-term gains (i. e., your child performing the tasks you want them to), they’re not ideal for the long haul.

e., your child performing the tasks you want them to), they’re not ideal for the long haul.

It’s important to teach children to communicate their needs and wants clearly and, if there is a disagreement, how to get their point across calmly and respectfully.

So, remember to stay calm when addressing your child. If you notice that they are being extra defiant and their behavior is making you lose your patience, consider taking a moment to calm down before conversing with them.

2) Sometimes Reasoning Doesn’t Help

As adults, we often want to understand why things need to be done because this can help motivate us to perform a specific action. But explanations don’t always work for children, especially those under six years of age.

For example, “If you don’t pick up your toys after using them, you might end up stepping on them and hurting yourself. I want you to tidy up because it’s best to have a clean space so you can move around freely.”

While such a statement might work for older kids, younger children aren’t able to relate to future consequences, so they may not get motivated to perform a task. This is another reason it’s best to keep directions short and to the point.

This is another reason it’s best to keep directions short and to the point.

3) Empower, Don’t Overpower

We’ve discussed how important it is to give clear instructions, and in some instances, this means not asking your child but telling them what to do. This approach works perfectly for young children who cannot grasp explanations and extra information from your directions.

But as children get older, they may start to respond to different situations independently.

For example, if you’ve always told them to pick up their toys because they may hurt themselves, they may decide that leaving toys lying around on one side of the room, where they are out of the way, works better than actually having to tidy up.

Sometimes parents view this as disrespectful behavior and resort to overpowering their children. Unfortunately, this can make children feel powerless and encourage defiance as they fight to “take back their power.”

A great solution may be to allow children, as they get older, some freedom to make their own decisions. For example, if they complain about their bedtime routine, encourage them to find what may be a better solution.

For example, if they complain about their bedtime routine, encourage them to find what may be a better solution.

This is not to say that children should do as they please. You’re still the parent! However, as children get older and start thinking independently, it’s perfectly fine to allow them room to make some decisions (at your discretion, of course).

Practice Makes Progress

With the strategies above, we hope you realize that, while it can be challenging to get children to follow our instructions, it’s not impossible. Sometimes simplicity, clarity, and a little fun are all you need.

Check out HOMER Learn & Play app for more playful and interactive ways to give your growing child the skills they need to thrive in life!

Author

Cascade and Inheritance - Learn Web Development

- Overview: Building blocks

- Next

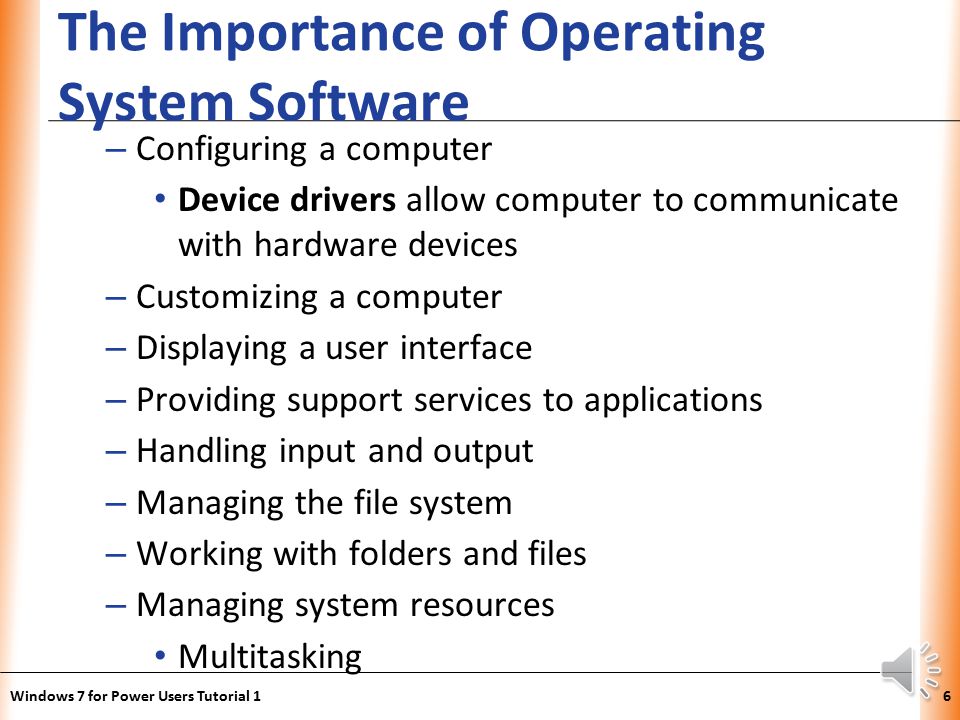

The purpose of this lesson is to deepen your understanding of some of the fundamental concepts of CSS—cascades, specifications, and inheritance—that control how CSS is applied to HTML and how conflicts are resolved.

While studying this lesson may seem less relevant and a little more academic than some of the other parts of the course, understanding these things will save you a headache later on! We recommend that you read this section carefully and make sure you understand the concepts before moving on. nine0009

| Prerequisites: | Basic computer literacy, basic software installation, basic knowledge of file handling, basic HTML (Introduction to HTML), and a basic understanding of how CSS works (Introduction to CSS.) |

|---|---|

| Purpose: | Learn the concept of cascade and specificity, and how CSS inheritance works. |

CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) stands for Cascading Style Sheets and the first word is "cascading" is incredibly important to understand: how cascading behaves is key to understanding CSS.

At some point while working on a project, you find that the CSS you think should be applied to an element doesn't work. Usually the problem is that you have created two rules that could potentially apply to the same element. Cascade and the closely related concept specificity are mechanisms that control which rule is applied when there is such a conflict. Your element's style may not define the rule you intended, so you need to understand how these mechanisms work. nine0009

Usually the problem is that you have created two rules that could potentially apply to the same element. Cascade and the closely related concept specificity are mechanisms that control which rule is applied when there is such a conflict. Your element's style may not define the rule you intended, so you need to understand how these mechanisms work. nine0009

Also significant is the concept of inheritance, which is that some CSS properties inherit by default the values set on the parent element of the current element, and some do not. It can also cause behavior that you might not expect.

Let's start with a quick overview of the key points we're covering, then go through each one in turn and see how they interact with each other and with your CSS. This may seem like a collection of difficult concepts to understand. However, as you gain more experience writing CSS, it will become more obvious to you how it works. nine0009

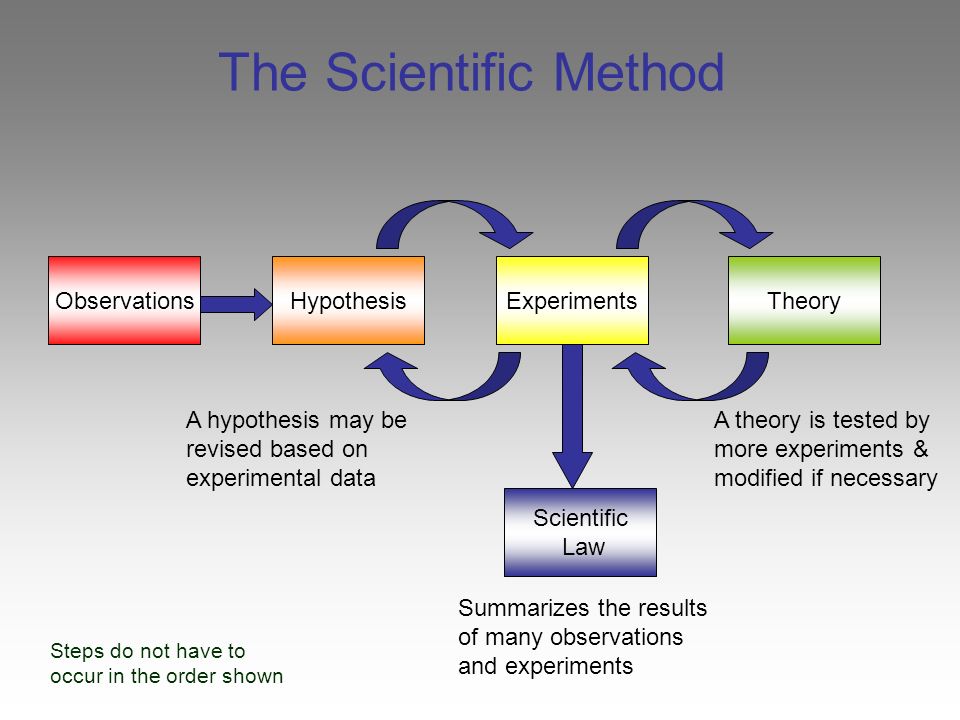

Cascade

Style sheet cascade, in simple terms, means that the order of the rules in CSS matters; when two rules that have the same specificity apply, the one that comes last in the CSS is used.

In the example below, we have two rules that can be applied to h2. As a result, h2 will be colored blue - these rules have an identical selector and, therefore, the same specificity, so the last one in the order wins. nine0009

Specificity

Specificity determines how the browser decides which rule to apply when multiple rules have different selectors but can still be applied to the same element. Different types of selectors (element selectors h2{...} , class selectors, identifier selectors, etc.) have varying degrees of effect on page elements. The more general effect a selector has on page elements, the less specific it is. nine0032 This is essentially a measure of how specific the selector will be:

- An element selector ( e.g.

h2) is less specific - it will select all elements of that type on the page - so it will score less. - The class selector is more specific - it will select only those elements on the page that have a specific attribute value

class- so it will get more points, the class selector will be applied after the element selector and therefore override its styles .

For example. As noted below, we again have two rules that can apply to h2 . h2 will be colored red as a result - the class selector gives its rule higher specificity, so it will be applied even though the rule for the element selector is lower in the style sheet.

Later we will explain how to make a specificity assessment and other details.

Inheritance

Inheritance must also be understood in this context - some CSS property values set on parent elements are inherited by their child elements, and some are not. nine0009

For example, if you set color and font-family for an element, then every element within it will also have that color and font, unless you directly styled them with a different color and font.

Some properties are not inherited - for example, if you set the element's width to as 50%, all of its child elements will not get a width of 50% of their parent element's width. If that were the case, CSS would be extremely difficult to use! nine0009

If that were the case, CSS would be extremely difficult to use! nine0009

Note: In the CSS property reference pages, you can find a technical information box, usually at the end of the specification section, that lists some technical information about the property, including whether or not it is inherited. For example, here: color property Specifications section (en-US) .

These three concepts together define which CSS is applied to which element; in the following sections, we will see how they interact. This may sound complicated, but you'll get a better understanding of them as you gain experience with CSS, and you can always refer to help if you've forgotten something. Even experienced developers don't remember all the details! nine0009

The video below shows how you can use the Firefox DevTools to check the stylesheet, specs, and more. on page:

So, inheritance. In the example below, we have with two levels of unordered lists nested within it.

We have set the outer

We have set the outer border style, padding and font color.

Font color applied to direct child, but also to indirect child - direct child and to the elements inside the first nested list. Next, we added the class special to the second nested list and applied a different font color to it. This property is now inherited by all its descendants.

Properties such as width (as in the example above), padding, padding, and border style are not inherited. If the children of our list were to inherit a border, then every single list and every position in the list would get the same border—we wouldn't want that kind of effect! nine0009

Which properties are inherited by default and which are not is most often determined by common sense.

Inheritance control

CSS provides four special generic property values for inheritance control. Every CSS property accepts these values.

-

inherit -

Sets the value of a property applied to an element to the same value as its parent element.

In fact, it "turns on inheritance". nine0009

In fact, it "turns on inheritance". nine0009 -

initial -

Sets the value of the property applied to the selected element to the initial value of that property ( according to the browser's default settings. If there is no value for this property in the browser's style sheet, it is inherited naturally.)

-

unset(en-US) -

Returns the property to its natural value, which means that if the property is inherited naturally, it acts like

inherit, otherwise it acts likeinitial.

Note: There is also a newer value revert which has limited browser support.

Note: See Origin of CSS declarations in [Page not yet written] for more information about each of them and how they work.

You can view the list of links and learn how generic values work. The example below lets you play around with CSS and see what happens when you make changes. Experimenting with code like this is the best way to learn HTML and CSS. nine0009

The example below lets you play around with CSS and see what happens when you make changes. Experimenting with code like this is the best way to learn HTML and CSS. nine0009

For example:

- The second element of the list has the class

my-class-1. Thus, the color for the next nested elementais set by inheritance. How will the color change if this rule is removed? - Is it clear why the third and fourth elements

andhave this color? If not, reread the description of values above. - Which link will change color if you set a new color for element

a { color: red; }?

Return all original property values

The CSS shorthand property all can be used to assign one of the inheritance values to (almost) all properties at once. This is one of four values ( inherit , initial , unset , or revert ). This is a convenient way to undo changes made to styles so that you can return to the starting point before making new changes. nine0009

This is a convenient way to undo changes made to styles so that you can return to the starting point before making new changes. nine0009

In the example below, there are two blocks . The first has a style applied to the element itself

blockquote , the second has a class fix-this which sets the value all to unset .

Try setting all to one of the available values and see what the difference is.

Now we understand why the next deepest paragraph in the structure of an HTML document has the same color as the CSS applies to the body, and the introductory lessons gave an understanding of how to change the CSS applied to something anywhere in the document - or assign CSS element, or create a class. Now let's take a closer look at how the cascade determines the choice of CSS rules that are applied when multiple objects affect the style of an element. nine0009

Here are three factors, listed in order of increasing importance. The next one overrides the previous one.

The next one overrides the previous one.

- Sequence

- Specificity

- Importance

We'll take a closer look at them to see exactly how browsers determine which CSS to apply.

Sequence order

We have already seen how important sequence order is for a cascade. If you have multiple rules that have the same importance, then the rule that comes last in the CSS wins. In other words, the rules closest to the element itself overwrite the earlier ones until the latter wins out and styles the element. nine0009

Specificity

Understanding that the order of the rules matters, at some point you will find yourself in a situation where you know that a rule appears later in the style sheet, but an earlier, conflicting rule is applied. This is because the earlier rule has more specificity than - it is more specific and therefore chosen by the browser as the rule that should style the element.

As we saw earlier in this tutorial, a class selector carries more weight than an element selector, so properties defined on the class will override properties applied directly to the element. nine0009

It should be noted here that although we think about selectors and the rules applied to the object they select, not the entire rule is rewritten, only the properties that are the same.

This behavior helps you avoid repetition in your CSS. It's common practice to define common styles for base elements and then create classes for those that are different. For example, in the stylesheet below, we define general styles for second-level headings, and then create a few classes that only change some of the properties and values. The values defined first are applied to all headers, then more specific values are applied to headers with classes. nine0009

Let's now see how the browser will calculate the specificity. We already know that an element selector has low specificity and can be overwritten by a class. Essentially, a point value is given to different types of selectors, and adding them up gives you the weight of that particular selector, which can then be ranked against other potential contenders.

Essentially, a point value is given to different types of selectors, and adding them up gives you the weight of that particular selector, which can then be ranked against other potential contenders.

The degree of specificity a selector has is measured using four distinct values (or components) that can be represented as thousands, hundreds, tens, and ones—four single digits in four columns:

- Thousands : Put one in this column if the style declaration is inside the

style attribute(inline styles). Such declarations have no selectors, so their specificity is always just 1000. - Hundreds : Put a one in this column for each ID selector contained in the general selector.

- Tens : Put one in this column for each class selector, attribute selector, or pseudo-class contained in the general selector. nine0004

- Units : Put the total number of units in this column for each element selector or pseudo-element contained in the general selector.

Note: The universal selector (*), combinators (+, >, ~, ''), and the negation pseudo-class (:not) do not affect specificity.

The following table shows some unrelated examples to help you understand. Check them all out and make sure you understand why they have the specificity we gave them. We haven't covered selectors in detail yet, but you can find detailed information about each selector in the MDN Selectors Reference. nine0009

| Selector | Thousands | Hundreds | Tens | Units | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

h2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0001 |

h2 + p::first-letter | 0 | 0 | 0 | nine0023 30003 | |

li > a[href*="en-US"] > . | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0022 |

#identifier | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0100 |

No selector, with the rule inside the style attribute of the element. nine0024 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1000 |

Before we continue, let's see an example in action.

So what's going on here? First of all, we're only interested in the first seven rules of this example, and as you'll notice, we've included their specificity values in a comment before each rule.

- The first two rules compete to style the background color of the link - the second one wins and makes the background color blue because it has an extra ID selector in the chain: its specificity is 201 vs.

101.

101. - The third and fourth rules compete for styling the color of the link text - the second wins and makes the text white because, although it has one less element selector, the missing selector is replaced with a class selector that evaluates to ten instead of one. Thus, the priority specificity is 113 vs. 104.

- Rules 5-7 compete to determine the style of the hover link's border. The sixth selector with specificity 23 clearly loses to the fifth one with specificity 24 — it has one less element selector in the chain. The seventh selector, however, outperforms both the fifth and sixth - it has the same number of subselectors in the chain as the fifth, but one element is replaced by a class selector. So priority specificity is 33 vs 23 and 24.

Note: This was a conditional example for easier assimilation. In fact, each selector type has its own level of specificity, which cannot be overridden by selectors with a lower level of specificity. For example, million connected selectors of class are not able to rewrite the rules of a single selector id .

For example, million connected selectors of class are not able to rewrite the rules of a single selector id .

A more correct way to calculate specificity is to individually evaluate specificity levels, starting at the highest and working down to the lowest when necessary. Only when the specificity level scores match should the next lower level be calculated; otherwise, you can neglect lower specificity selectors, as they will never overcome higher specificity levels. nine0009

!important

There is a special CSS element that you can use to undo all of the above calculations, but you have to be very careful with its use - !important . It is used to make a particular property and value the most specific, thus overriding the normal cascade rules.

Take a look at this example where we have two paragraphs, one of which has an ID.

Let's walk through this example to see what's going on - try removing some properties to see what happens if you're having a hard time understanding:

- You will see that the

color(en-US) andpaddingvalues of the third rule are applied, butbackground-coloris not. Why? Indeed, all three should certainly apply, because the rules later in the order usually override the earlier rules.

Why? Indeed, all three should certainly apply, because the rules later in the order usually override the earlier rules. - However, the above rules win because class selectors have higher specificity than element selectors.

- Both elements have

classnamedbetter, but the second one also hasidnamedwinning. Because IDs have even higher specificity than classes (you can only have one element with each unique ID on a page, but many elements with the same class - ID selectors are very specific, which is what they aim for) , a red background color and a one-pixel black border should be applied to the 2nd element, with the first element getting a gray background color and no border, as defined by the class. nine0004 - The 2nd element got a red background color and no border. Why? Because of the declaration

!importantin the second rule - placing it afterborder: nonemeans that this declaration will override the value of the border in the previous rule, even if the ID has a higher specificity.

Note: The only way to override declaration !important is to include another declaration !important in rule with the same specificity later or into a rule with higher specificity.

It's useful to know that !important exists so that you understand what it is when you see it in someone else's code. However, we strongly recommend that you never use it unless absolutely necessary. !important changes the normal way the cascade works, so it can make debugging CSS issues really difficult, especially in a large stylesheet. nine0009

One situation where you might need to use this is when you're working with a CMS where you can't edit core CSS modules and you really want to override a style that can't be overridden in any other way. But generally speaking, you shouldn't use this element if you can avoid it.

Finally, it's also useful to note that the importance of a CSS declaration depends on which style sheet it's in - it's possible for the user to set individual style sheets to override the developer's styles, for example, the user may be visually impaired and want to set the font size to all the web pages he visits are twice the normal size to make it easier to read. nine0009

nine0009

Conflicting declarations will be applied in the following order, with earlier replaced by later:

- Declarations in the client application's style sheets (for example, default browser styles used when no other styles are set).

- Regular declarations in user style sheets (individual styles are set by the user).

- Regular declarations in author's style sheets (these are styles set by us web developers). nine0004

- Important declarations in author's style sheets.

- Important declarations in user style sheets.

It makes sense for web developer style sheets to override custom style sheets so that the intended design can be maintained, but sometimes users have good reasons to override web developer styles as mentioned above - this can be achieved by using ! important in their rules. nine0009

We have covered many topics in this article. Can you remember the most important information? You may want to take a few additional tests to make sure you understand this information before moving on - see Test your skills: the Cascade.

If you've understood most of this article, great - you've started to get familiar with the fundamental mechanics of CSS. Next, we'll look at selectors in detail.

If you don't fully understand cascade, specificity, and inheritance, don't worry! This is by far the most difficult thing we've covered in the course so far, and even professional web developers sometimes find it tricky. We encourage you to come back to this article several times during the course and continue to think about this topic. nine0009

See here if you run into weird issues where styles don't apply the way you expect. This may be a specificity issue.

- Overview: Building blocks

- Next

- Cascade and inheritance

- CSS selectors

- Type, class and ID selectors

- Attribute selectors

- Pseudo-classes and pseudo-elements

- Combinators

- The box model

- Background and borders

- Processing different text directions

- Content overflow

- Values and units

- Resizing in CSS

- Image, form and media elements

- Styling tables

- Debugging CSS

- Organizing your CSS

Last modified: , by MDN contributors

“Sustainability is our business”

Acting President of the largest brewing company AB InBev Efes Oraz Durdyev told Vedomosti. Ecology” about how concern for the well-being of employees and consumers is being transformed in a new reality.

The environmental agenda directly depends on the economic situation and is associated with many factors, such as the supply of technological solutions, equipment, packaging materials. Despite the difficulties faced by Russian companies, this agenda remains no less relevant. After all, in addition to the obvious positive impact on the environment, the transition to more environmentally friendly and efficient solutions, as well as high standards of social responsibility, improved reporting quality, process transparency and business ethics help ensure long-term competitiveness of business both domestically and in foreign markets. nine0032

— Sustainable development in the new reality. Ecology or economy? How important is it in the current environment to continue to develop sustainable products, despite the fact that they often require additional financial investments?

Ecology or economy? How important is it in the current environment to continue to develop sustainable products, despite the fact that they often require additional financial investments?

— Sustainable development is an already formed long-term trend that will remain one of the key factors in the development of the economy in any of its conditions.

Russian business also confirms the importance of continuing work in this direction. Thus, at the end of April, the results of the survey "Sustainable Development in Modern Conditions" were presented, in which representatives of large, small and medium-sized businesses took part. According to the survey, almost half of the respondents will not only continue to report on their sustainability performance and evaluate suppliers and business partners according to ESG parameters, but also intend to broadcast this agenda to foreign markets. The key priorities are the efficient use of resources, the development of regions of presence, the formation of new supply chains and effective mechanisms for state support of business. nine0009

nine0009

At the same time, for AB InBev Efes, in addition to the issues outlined above, decarbonization, the circular economy, and waste reduction remain important topics. Late last year, the company announced its ambition to achieve carbon neutrality across its entire supply chain by 2040. The basis of our strategy is still the same - the transition to environmentally friendly energy sources and increasing the efficiency of production processes, and we are actively working in this direction.

We are also working to improve the sustainability of other value chain categories such as packaging. So, on June 16, 2022, at the site of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, the company presented an “ultra-light” beer bottle. For the first time in the industry, AB InBev Efes, together with one of the leading glass container manufacturers Sibsteklo, has reduced the weight of a beer bottle from the current 265 grams to 235 grams, which reduces CO2 emissions by 10% per bottle. The serial production of the "ultra-light" bottle is planned to begin before the end of 2022. nine0009

The serial production of the "ultra-light" bottle is planned to begin before the end of 2022. nine0009

The first brand to use innovative packaging will be Stary Melnik iz keg, whose bottle has been the best-selling bottle in Russia since 2016.

- ESG is not only E, but also S. How is the company's policy in this direction being implemented now?

— In the current economic situation, social projects aimed at supporting employees are becoming one of the key areas for business, since now the main thing for us is to preserve human capital and not lose valuable qualified personnel. nine0009

During the pandemic, we realized how important employer support is for employees, and launched a number of initiatives that have become especially relevant now.

For example, AB InBev Efes has a "Get Support" program under which the company's employees and their families can receive confidential and qualified assistance from a lawyer, financial specialist and psychologist free of charge.

The program is valid from 2020. During this time, more than 2000 consultations were provided. Psychological consultations turned out to be the most popular - more than 1600 consultations were held. nine0009

Another relevant support measure is corporate medical programs. In conditions of an unstable financial and economic situation, rising prices and falling incomes of the population, they acquire additional significance. For example, AB InBev Efes has a free medical check-up program available to employees across the country and the LEON wellbeing platform. The main mission of the platform is to support health, implemented through the provision of daily tips and recommendations in the form of mini-articles, as well as assistance in the formation of healthy habits. nine0009

We also believe that caring for the family should take an important place in the company's social policy - this helps to create more comfortable conditions for employees and improve the balance between work and personal life. The most effective form is corporate maternity and parental leave programs. The Expanded Child Care Policy, which was implemented at AB InBev Efes at the end of 2021, provides for an increase in paid leave for the primary caregiver from 20 to 26 weeks and maintains 100% regular remuneration during this period. The second parent also has a fully paid maternity leave, which is increased from 2 to 4 weeks. nine0009

The most effective form is corporate maternity and parental leave programs. The Expanded Child Care Policy, which was implemented at AB InBev Efes at the end of 2021, provides for an increase in paid leave for the primary caregiver from 20 to 26 weeks and maintains 100% regular remuneration during this period. The second parent also has a fully paid maternity leave, which is increased from 2 to 4 weeks. nine0009

To help parents make the transition to work as comfortable as possible, our policy also allows an employee to work 75% of the time after returning from maternity leave while receiving full pay for the 8 weeks following their return from maternity leave.

- The company has 11 factories throughout the country. How are things going with the socio-economic support of the regions?

— We continue to work and develop social and economic partnerships in the regions where the company operates. A recent example is the conclusion of cooperation agreements with the Republic of Mordovia and the Ulyanovsk region, where agreements were reached to continue the implementation of major investment and social projects by the company: the development of its own agricultural program for growing high-quality malting barley, supporting local farms, ensuring employment, developing industrial tourism and culture of responsible drinking. nine0009

nine0009

We also continue to introduce innovations in the field of management and production, including those that contribute to the rational consumption of natural resources. Thus, last year alone, the volume of water saved at all production sites of AB InBev Efes in Russia exceeded 250 million liters.

Another example of a social and environmental initiative is the traditional support for World Environment Day, within which we organize and take part in the improvement of not only our own factory territories, but also public urban spaces: parks, squares, etc. nine0009

— The concept and principles of sustainable development have become widespread over the past few years. Do you agree that a new generation of people around the world is increasingly pursuing a principled and responsible approach to nature and changing their consumer preferences accordingly? As a rule, we are talking about the fact that today's youth will not buy and even use goods, the production of which is associated with harm to the environment. Will it remain relevant in today's rapidly changing reality? nine0036

Will it remain relevant in today's rapidly changing reality? nine0036

— Indeed, for the younger generation, naturalness, environmental friendliness, and social obligations of the brand are more important. According to the UPCEA, this generation is risk-averse and pragmatic, which means they are more careful about their finances.

However, it cannot be said that this does not matter to other generations. Conscious, or, as it can also be called, sustainable consumption is a global trend. Increasingly, consumers are choosing stores and brands based on the principles of sustainable development, and are even ready to boycott businesses that do not comply with these requirements. nine0009

According to Euromonitor, the most important thing consumers want from business is to protect the interests of society and the planet, and we believe that this demand will remain relevant in the face of new challenges.

- Is there a commercially justified need to, for example, indicate on the packaging of their products information about their naturalness, environmental friendliness, degree of processing, or something similar? Is it important for the consumer, and how not to fall for greenwashing?