Importance of name recognition in preschool

5 Reasons Why Name Recognition Activities Benefit Kindergarten Students

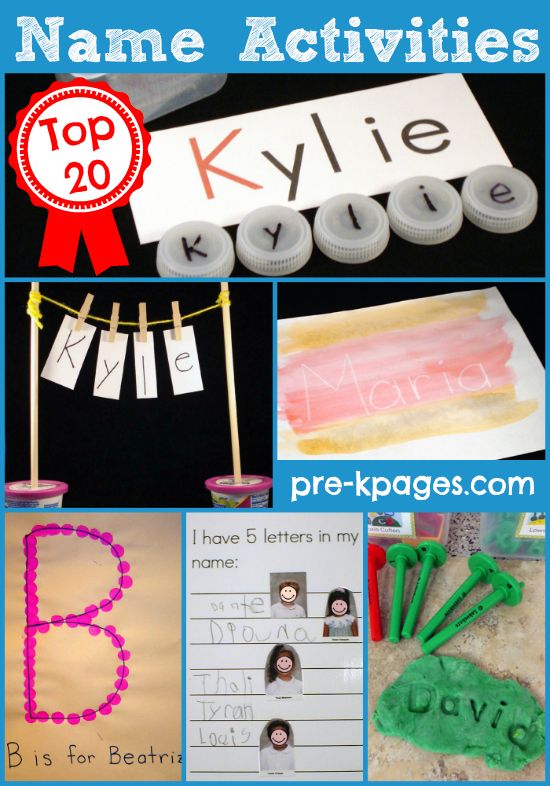

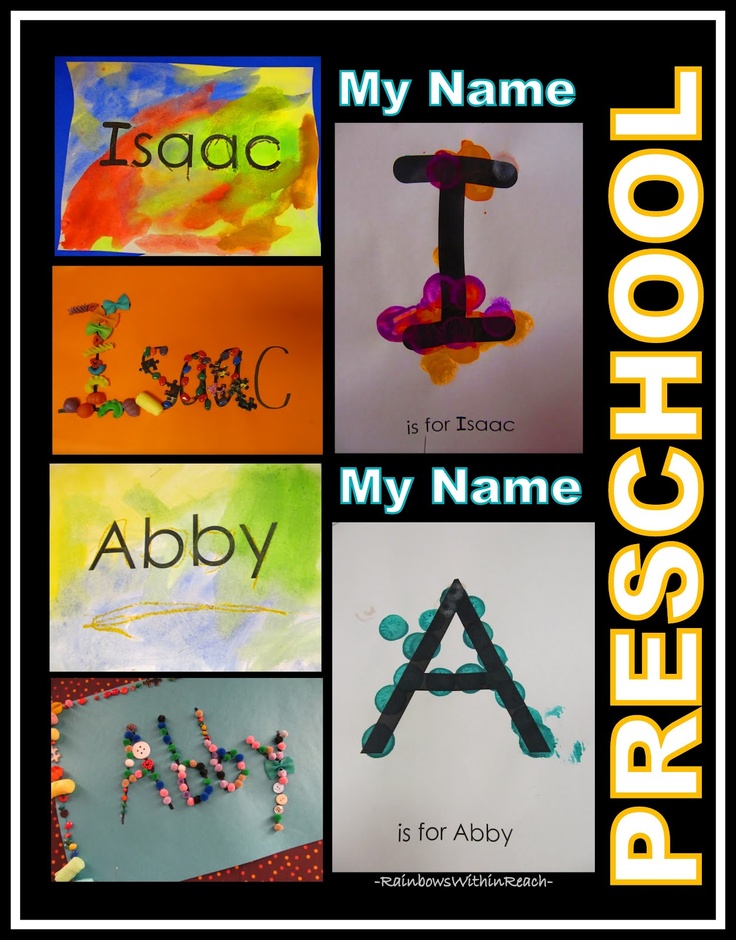

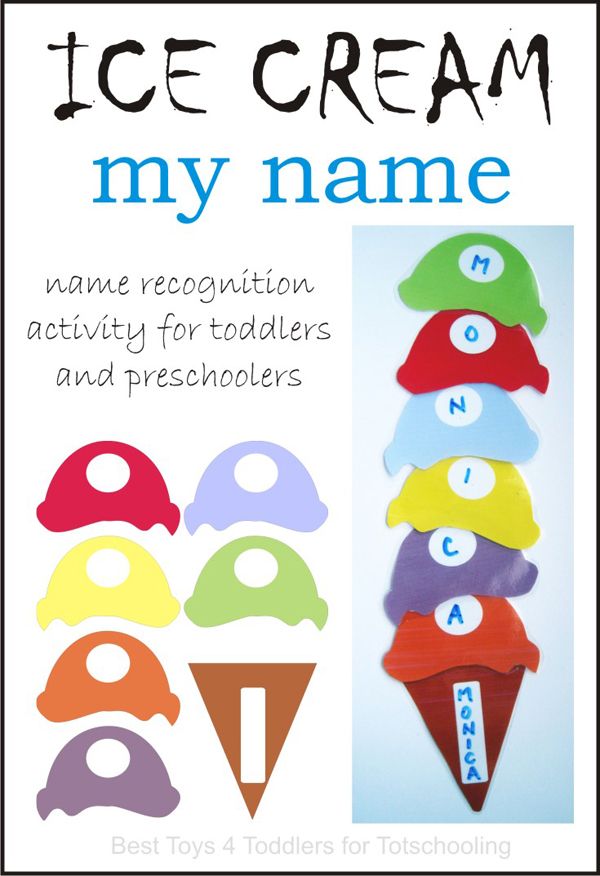

When you think of the typical kindergarten classroom decor, what comes to mind? You may think of bright colors, fun books, and expectation charts. You probably also think of cute name charts, often with students’ pictures next to their names. That’s because young children’s literacy foundations include name recognition activities.

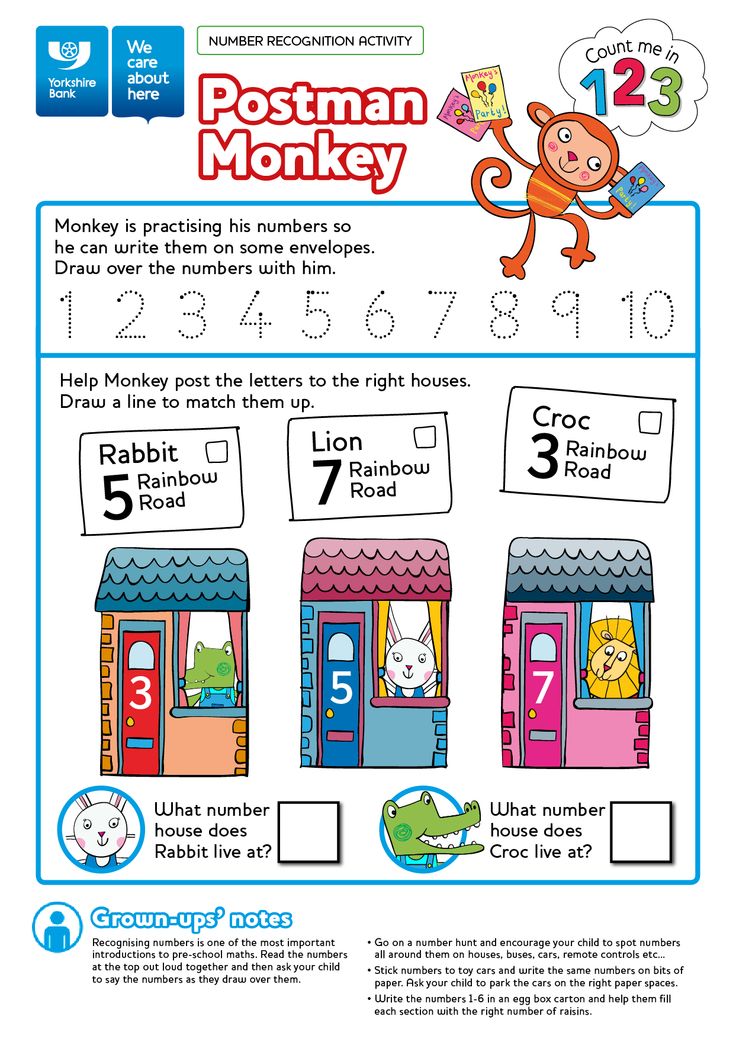

Recognizing our names is one of the early literacy skills kindergarten students learn. Besides simply making finding the cubby easier, name recognition leads to a deeper understanding of letters and sounds and how they work together. Let’s dive into five reasons why name recognition activities need a place in the kindergarten classroom.

Name recognition serves as a catapult to literacy learning for kindergarten students.

First children master auditory name recognition, and then they learn their names visually. This is one of the most meaningful words we can teach our students. When they recognize their name, they’ll have a foundation to catapult their learning. Students will begin to connect letters to sounds and spelling patterns and eventually to reading words.

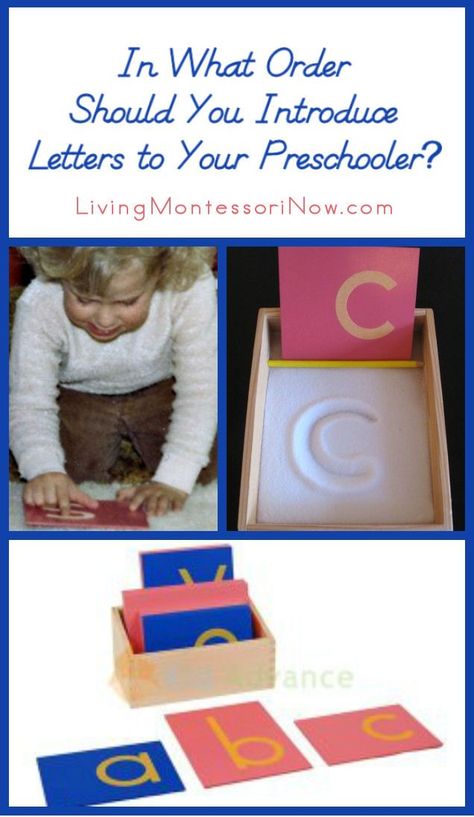

We can use students’ names to help them learn letter names and sounds.

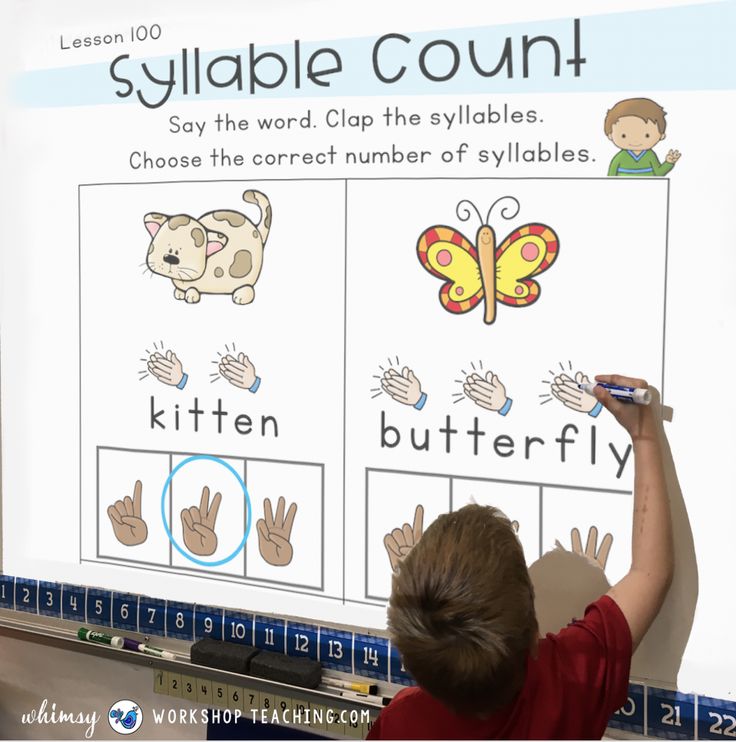

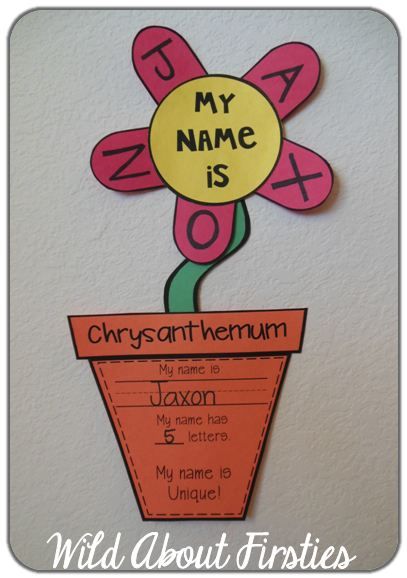

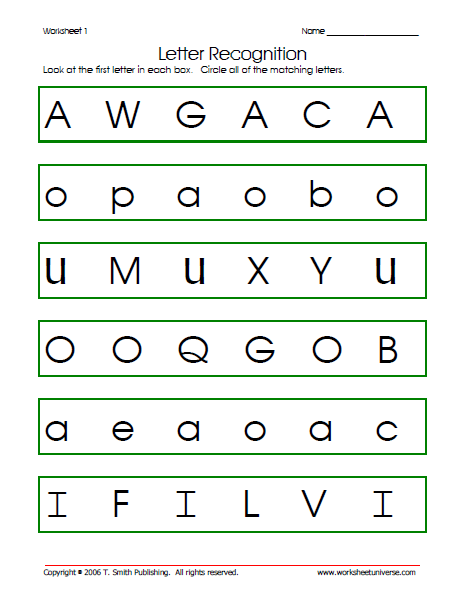

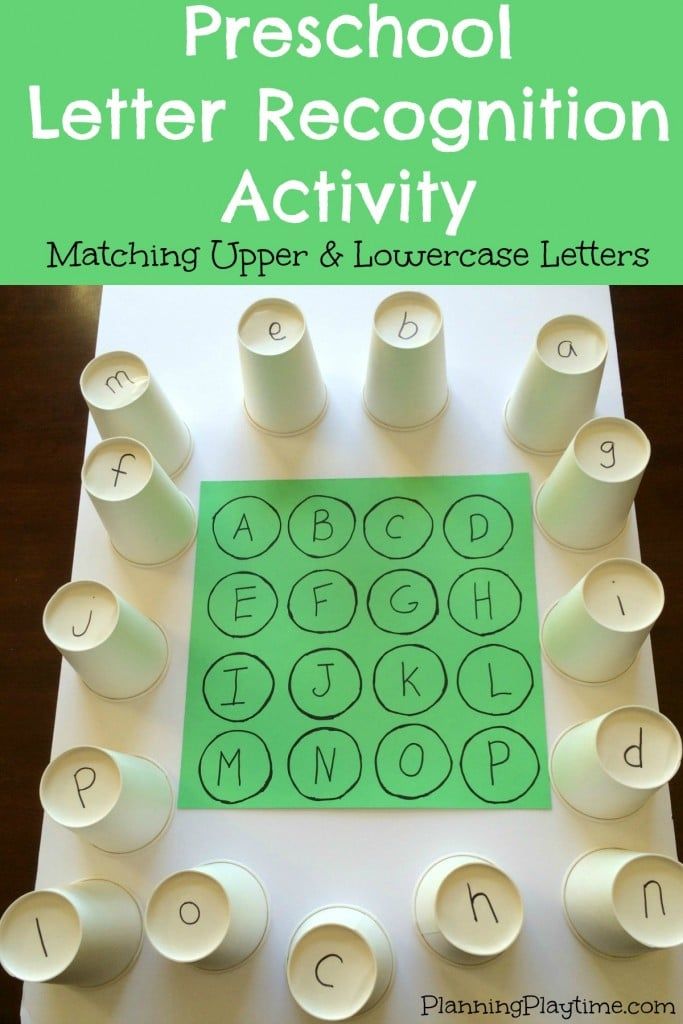

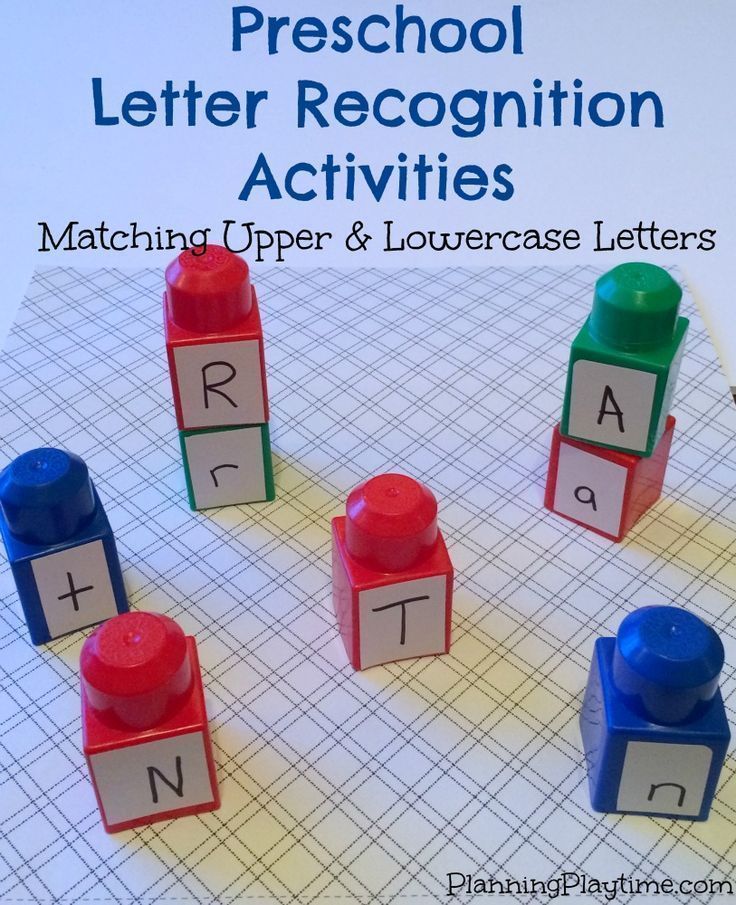

Once students can recognize their names, they can start learning these letters by name and the sounds they represent. Then, you can build on that and help them learn more letters and the sounds they represent. Students can practice sorting letters words that have the same letters in their names for example.

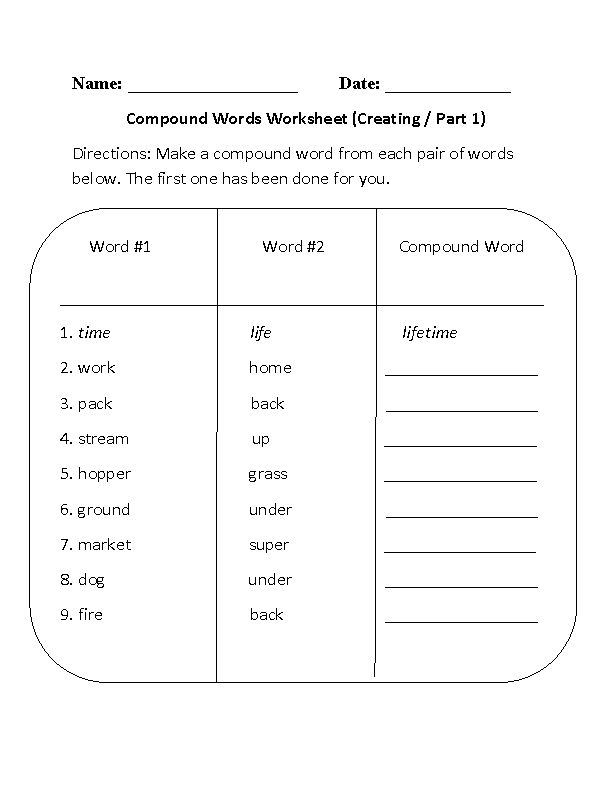

Students’ names can also be used to teach more complex spelling patterns and phonics concepts.

Another reason why name recognition activities are crucial to the classroom is that they give students a meaningful way to learn and recognize more complex spelling patterns. They also get exposure to phonics concepts that are meaningful to students (who doesn’t love relating a topic to a classroom friend’s name!).

For example, you can introduce vowels and consonants by sorting students’ names by how many vowels each student has in their name. Then, you can progress to teaching more advanced phonics lessons like digraphs and vowel teams in the same way.

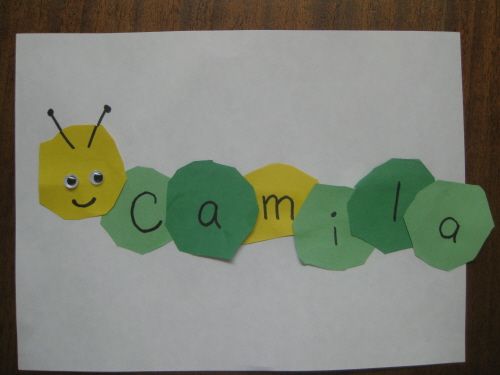

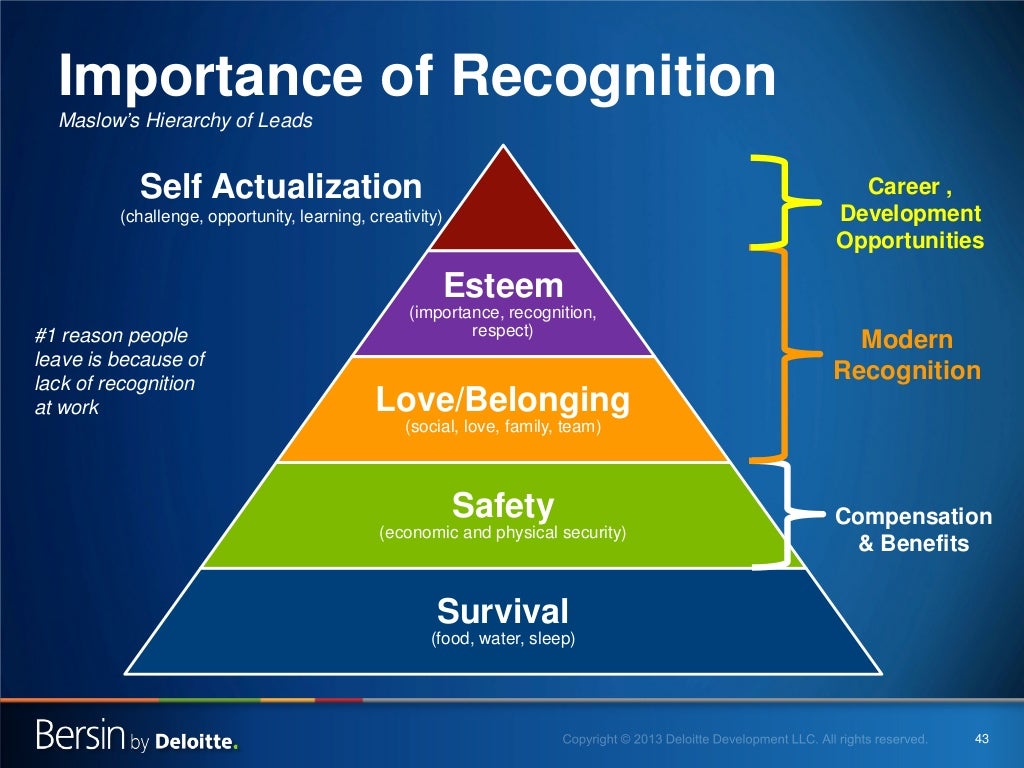

Name recognition helps build a strong classroom community and foster relationships.

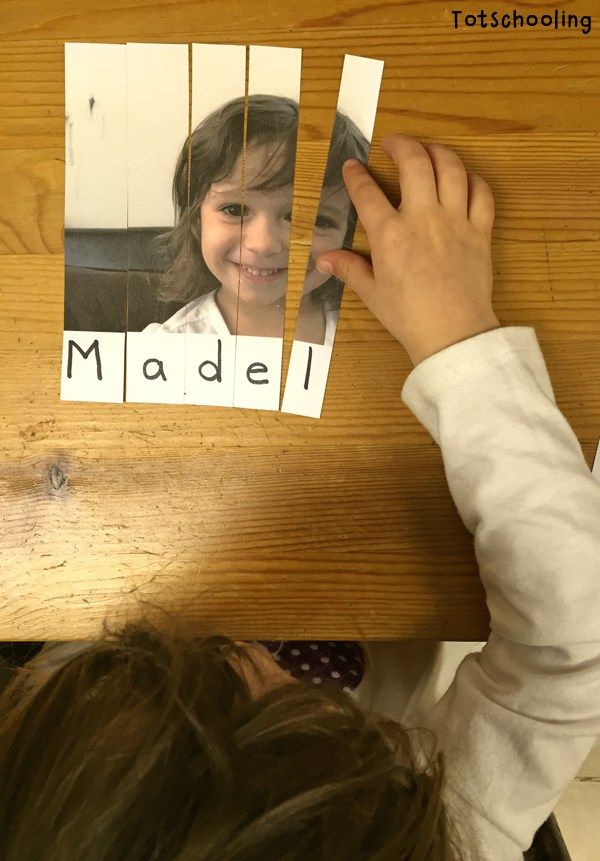

As soon as students start learning each other’s names, they will start forming bonds and relationships. Positive interactions between each other (and you!) will lead to a strong, healthy classroom community. Building a classroom community helps students feel like they belong and have a purpose in the group. This ultimately leads to students experiencing more academic success in the classroom! You can include students’ pictures with name recognition activities to really help them learn each other’s names quickly. I often found my students using the name chart to write stories about each other during writer’s workshop, too!

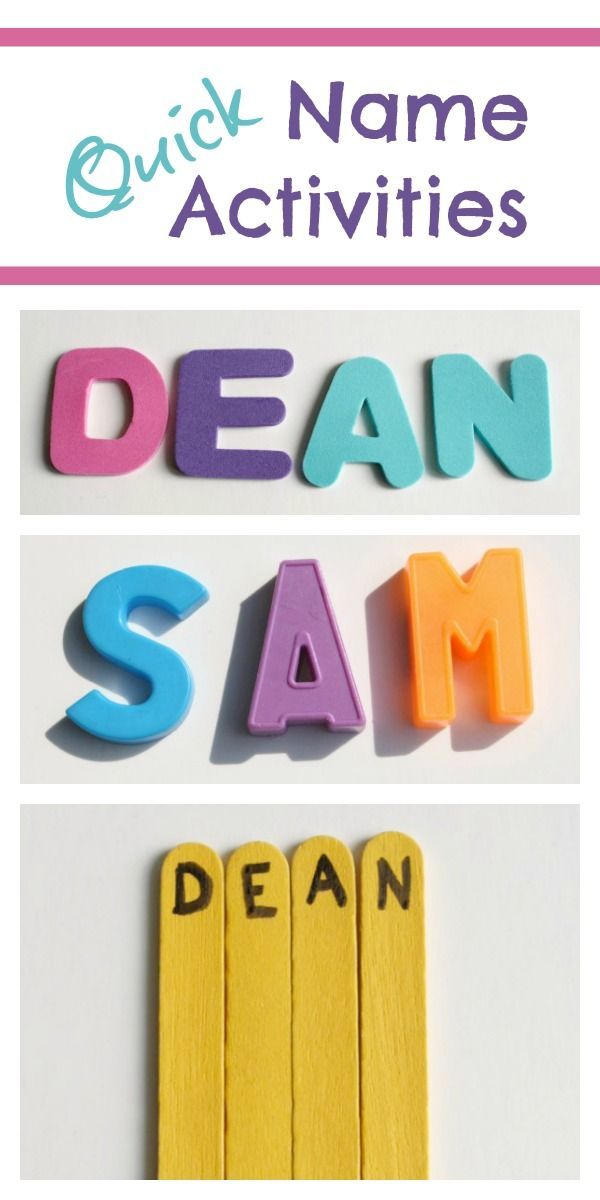

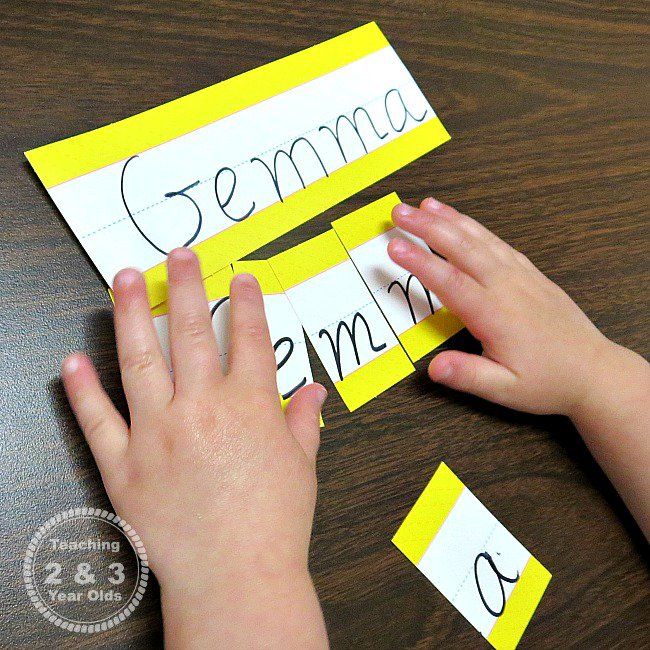

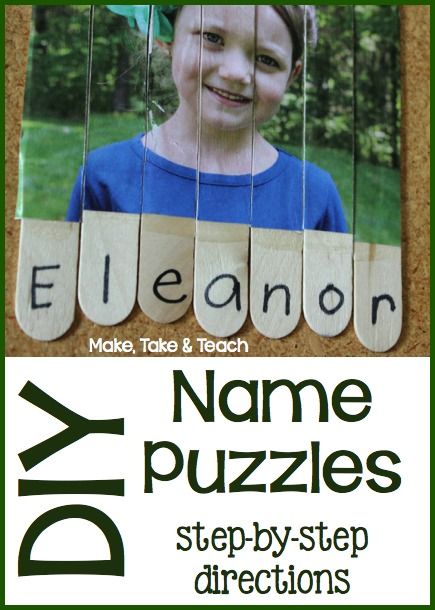

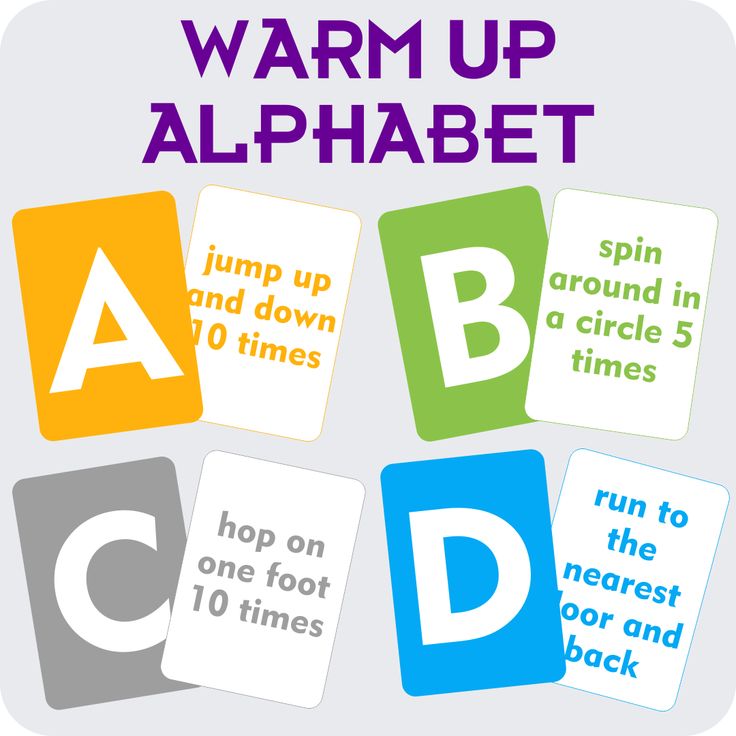

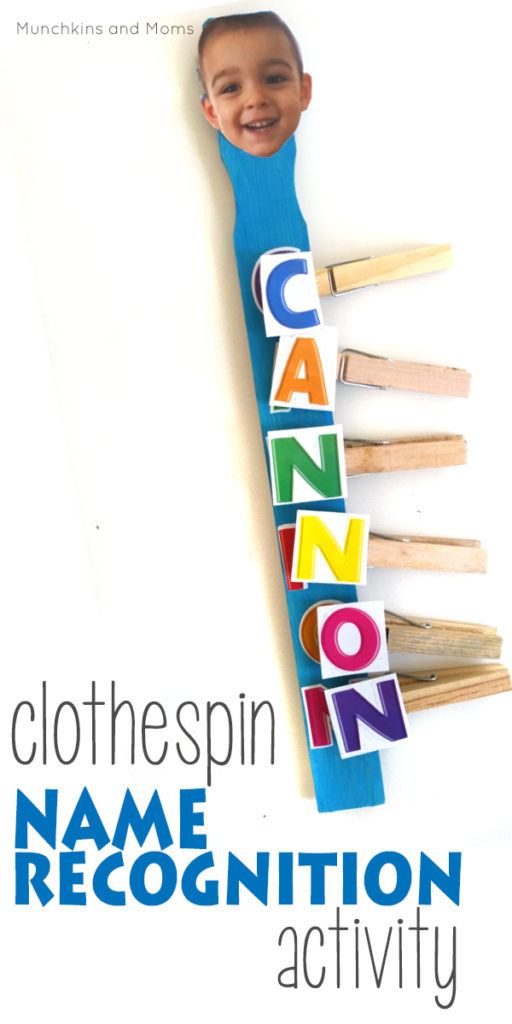

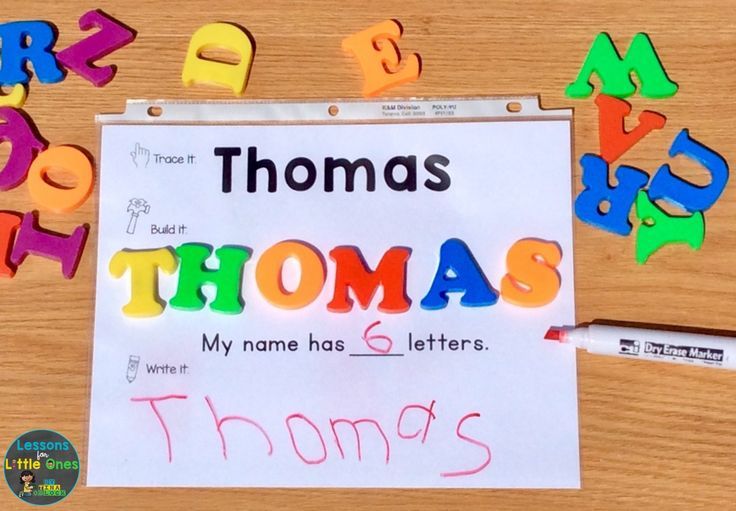

Students can have hands-on practice with letters and words in an engaging and meaninful way.

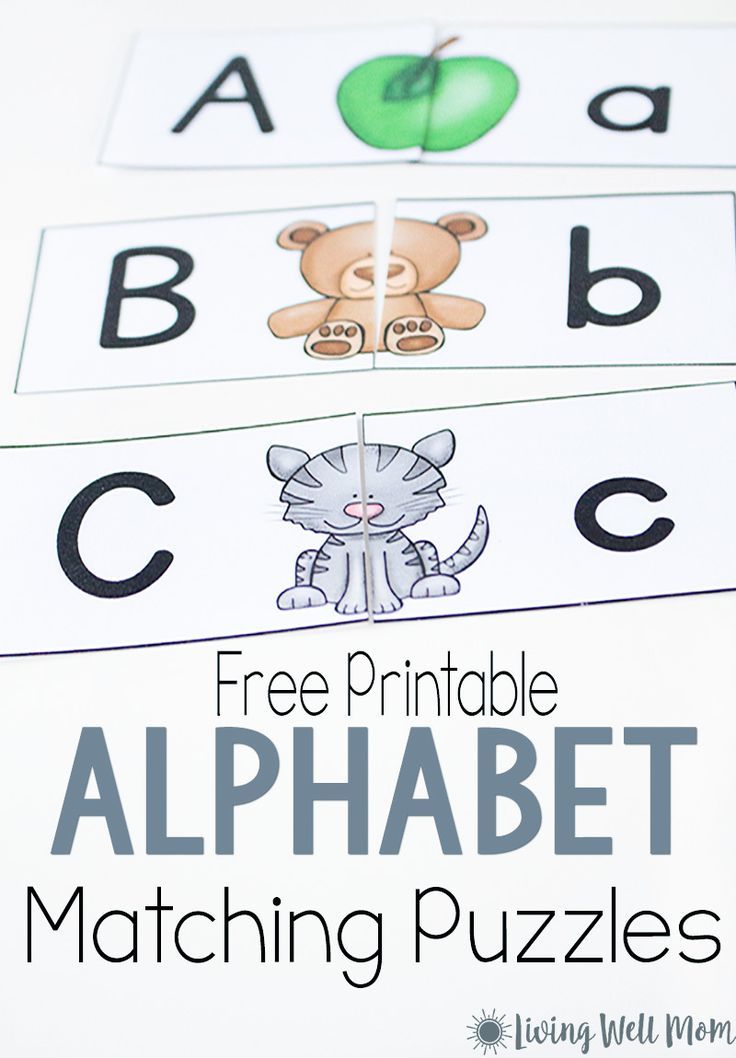

Finally, name recognition activities give students hands-on experiences working with letters and sounds. For example, you can have students create and complete activities like name puzzles, letter sorting, and building smaller words out of names. All of these only require students’ names written on index cards or sentence strips. Students can also practice building each other’s names, which is always a hit! These simple, yet effective activities, keep students engaged while providing opportunities to deepen letter and sound knowledge.

5 FREE Name Recognition Activities for Kindergarteners

This FREE PRINTABLE resource has five name recognition activities that are perfect for the kindergarten classroom. It’s perfect for the beginning of the year! After introducing each one, you can use it during:

- literacy stations

- morning work

- intervention time

- word work

First, download the free printable. Next, write students’ names on index cards or sentence strips. If you can, add a photo of each student. Finally, place the task cards and name cards in a pocket chart. If you don’t have a spare pocket chart, they can do these activities on the floor or on a table. Easy and done!

Next, write students’ names on index cards or sentence strips. If you can, add a photo of each student. Finally, place the task cards and name cards in a pocket chart. If you don’t have a spare pocket chart, they can do these activities on the floor or on a table. Easy and done!

If you’re looking for more word work activities that will help kindergarten students move forward in phonics and reading skills, check out these resources that teachers love:

- Interactive Alphabet Books

- Word Work Bundle Levels A-D

- Word Work Bundle Levels E-J

- Sight Word Practice Pages

- Hands-On Sight Word Activities

- Phonics Clip Cards Bundle

Want to use the latest research to boost your readers during small groups? This FREE guide is packed with engaging ideas to help them grow!

How Children Learn their Names in 3 Important Stages

This post may contain affiliate links. See Disclosure for more information.

See Disclosure for more information.

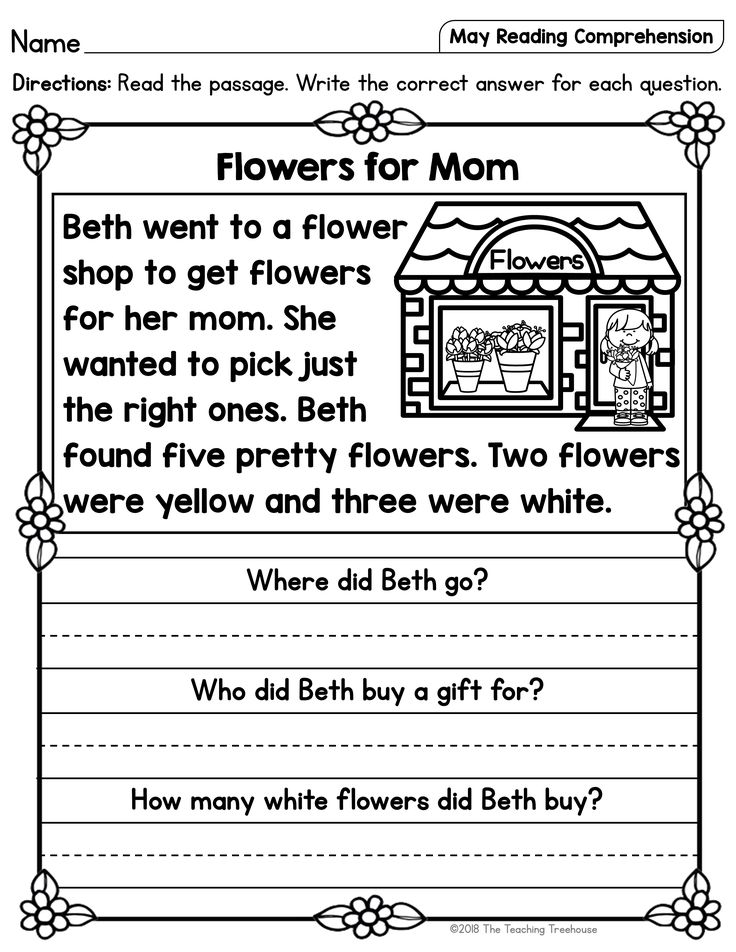

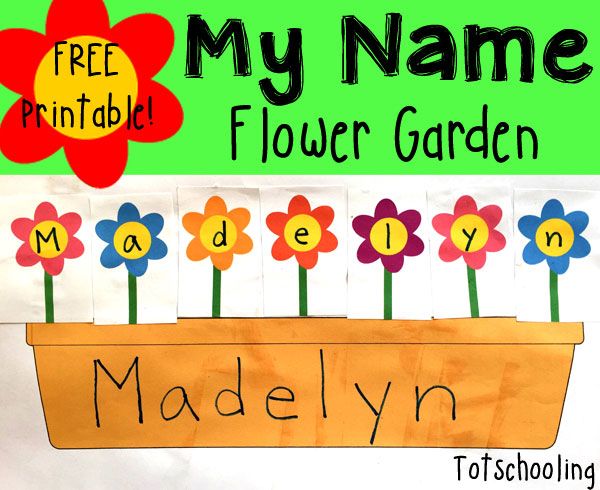

Learning our names is the springboard for literacy learning in preschool! Children’s names are the most important words to them, and learning them leads to all other types of learning. When we talk about teaching children their names, it is important to consider these three stages.

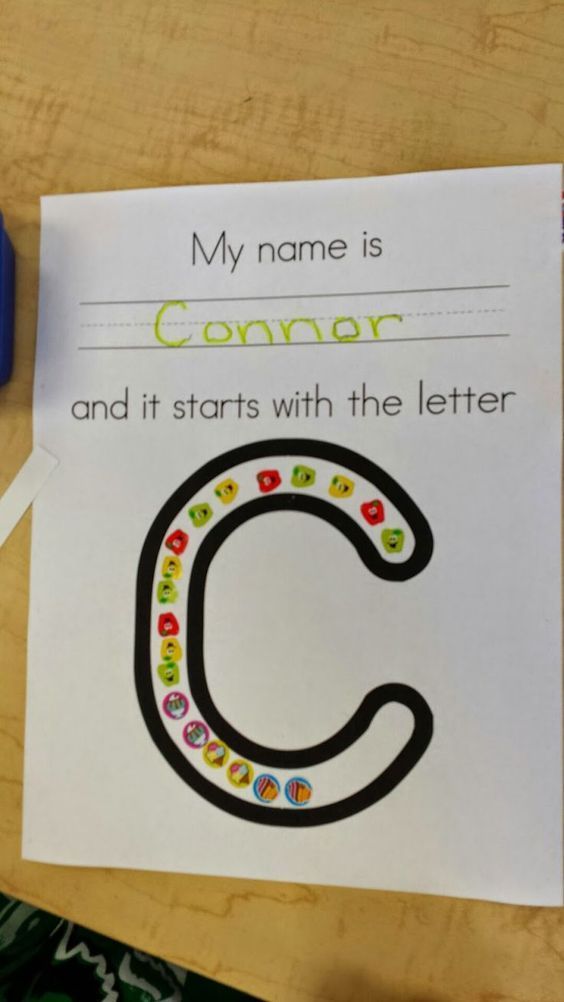

The first stage of learning names occurs when children start to recognize them! Young children begin to recognize the shape of their initial letter and often identify that first letter as “MY NAME!” They might find that initial letter in other places (separate from their names), point to it and say, “Look! There’s my name!” even if it is just the one letter.

In preschool, we can do lots of things to foster children’s recognition of their names. We label everything (lockers, change of clothes cubbies, snack chairs, carpet squares, folders, attendance chart, helper chart, and the alphabet wall) with their names and pictures, so that they begin to claim ownership of that very important word!

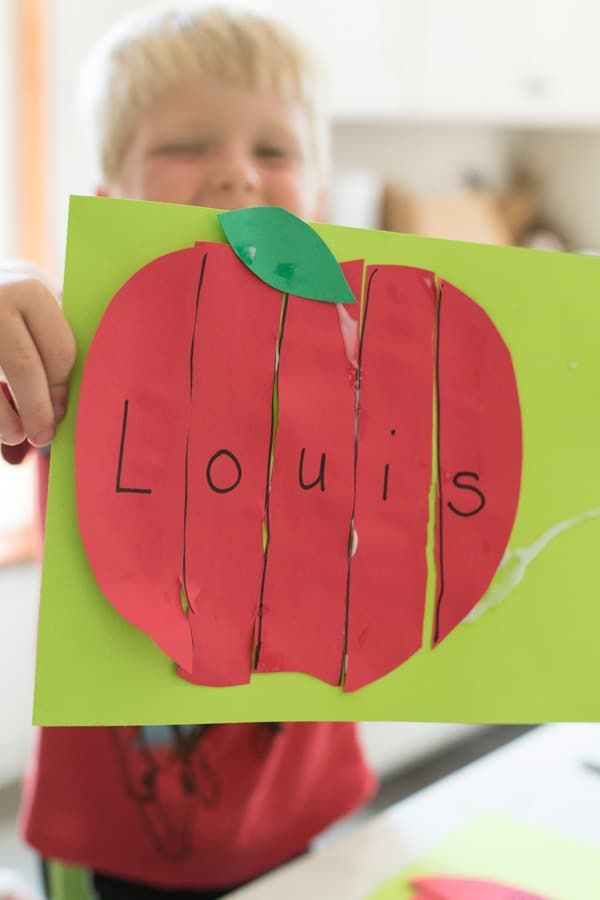

We use circle time as an opportunity to practice recognizing not only the child’s own name, but the names of all the classmates as well. This is one of our favorite circle time songs for September. We write the students’ names on apple cutouts and spread them all over the carpet. Then we repeat the verse for each child. They love to find each other’s apples!

This is one of our favorite circle time songs for September. We write the students’ names on apple cutouts and spread them all over the carpet. Then we repeat the verse for each child. They love to find each other’s apples!

With repeated exposure and practice recognizing each other’s names, the children begin to identify letters. Sarah and Shawn might have a difficult time figuring out which name is theirs because of the shared initial letter and close appearance of the other letters, so we just keep working on it noticing similarities and differences. Joshua might notice that, “Look! I have Olivia’s O in my name.”

Find this activity and more right HERE:

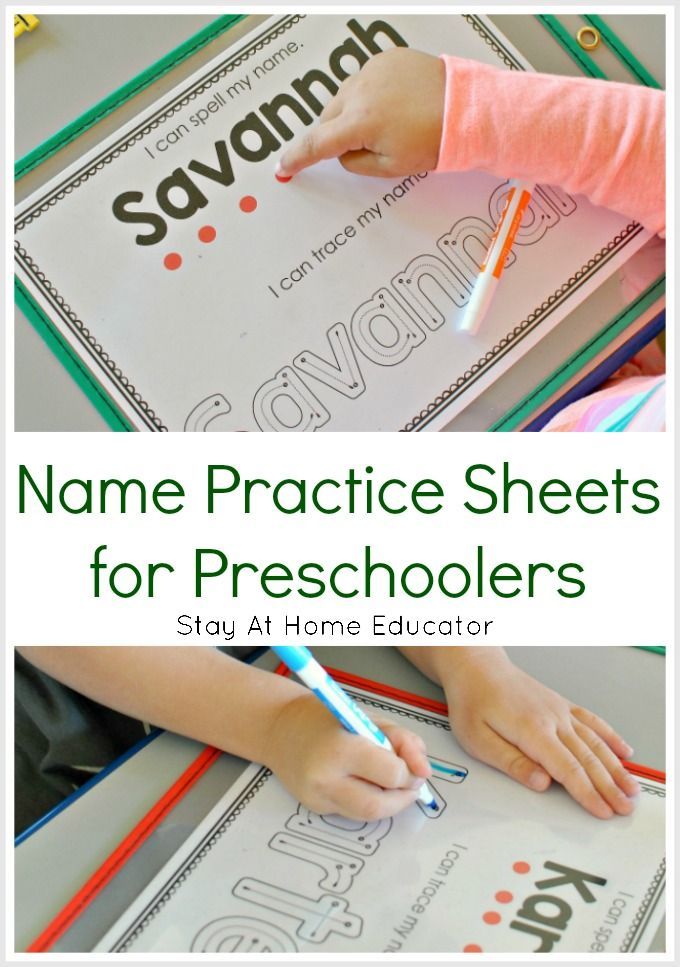

The next step, after children are able to recognize their names is to begin to spell them orally. We practice this in many ways. A child might be able to recite, “E-T-H-A-N” without seeing it written down. Then they will begin to notice each letter. We provide a name activity like this one each morning for our students to practice.

We practice with both capital letters (for all the reasons I wrote about in this post), and we also practice matching capitals to lower case like this:

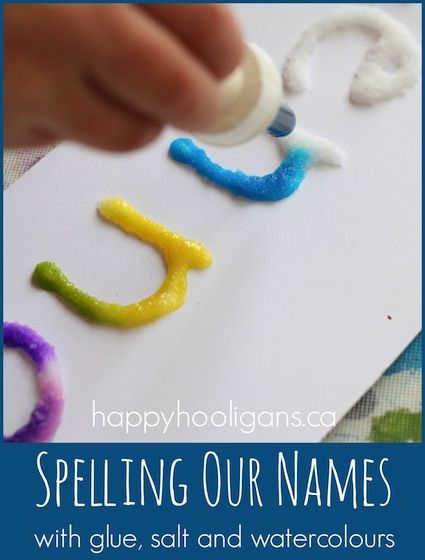

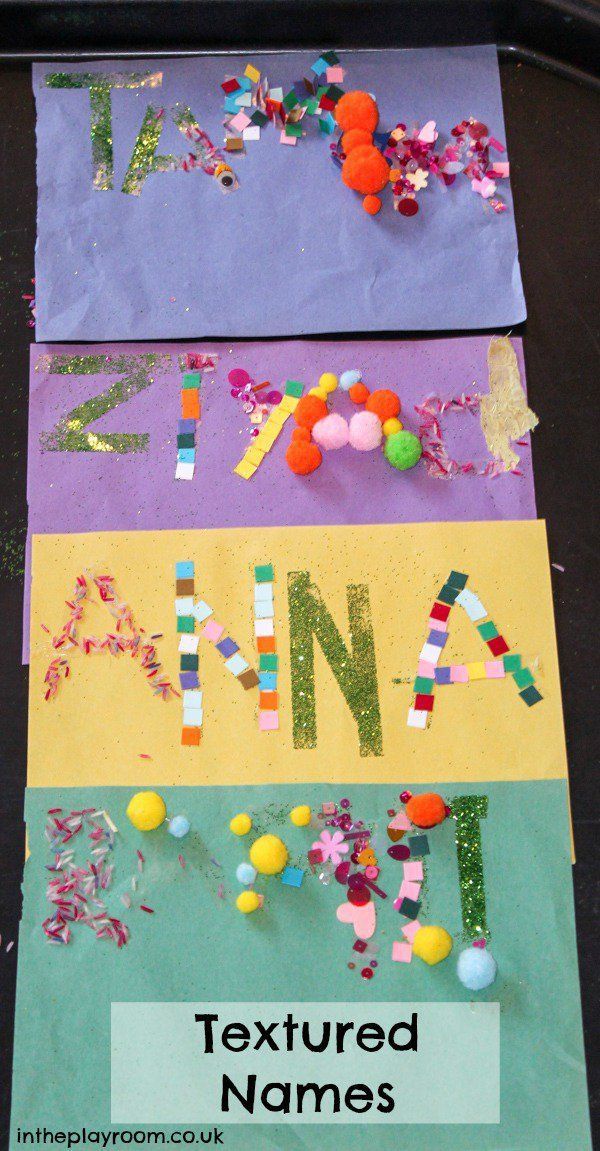

When the children are comfortable with recognizing and spelling their names, the next step is to work on writing them. Often these steps overlap and work in conjunction with each other! We give our children lots of opportunities to write their names with sidewalk chalk, paint, markers, in salt trays, etc. They are also work on strengthening their hand muscles and refining their fine motor skills. Our older Pre-K students (less than 1 year to kindergarten) also sign in their names each morning. It’s such a rewarding way to keep track of their progress.

When children begin to write, they often use what they already know about names (from learning to recognize their own name and their friends’ names and from learning to spell them). For an example, the first time Leah write her name (with sidewalk chalk in the driveway), she verbalized her thinking.

“

L is for Leah.L-E…

E is for (my brother) Evan.L-E-A…

A is for (my best friend) Anna.L-E-A-H…

H is for (my baby-sitter) Holly.Look!! I wrote my whole name.”

Learning about names is an essential part of learning about letters and literacy in preschool. Practice recognizing, spelling and writing those names in a variety of fun and playful ways!

Try these EDITABLE NAME PRACTICE PAGES for your students who are learning how to write their names. You just type in your class list and print customized, differentiated name worksheets for each child. So quick and simple!

Are you a teacher?

FREE Name Bundle!

Enjoy Free Name resources perfect for your preschoolers!

After you subscribe, you will be redirected to the FREE Name Resources. We respect your privacy. Unsubscribe at any time.

Follow Play to Learn Preschool’s board Literacy: Name Games on Pinterest.

Filed Under: Literacy, Name Activities

You May Also Enjoy These Posts

Birthday Party Dramatic Play – Something to Celebrate!

Alphabet Sensory Play

1.2 Development of figurative memory in preschool children. The development of figurative memory in preschool children with hearing impairment

The development of figurative memory in preschool children with hearing impairment

thesis

The issue of memory development has generated great controversy in psychology. For all the seeming obviousness and undoubted relevance of the issue, the theoretical provisions of the doctrine of the development of the memory of preschool children do not have classical monotony. L.S. Vygotsky showed that there are not as many controversies on any topic of modern psychology as there are in the theories explaining the problem of memory development [5].

Under these conditions, the theoretical provisions of the concept of memory development proposed by P. P. Blonsky. They were allocated: motor, emotional, figurative, verbal memory. He considered these types of memory as steps of a single genetic series. In particular, in his opinion, emotional memory itself has its basis in sensory memory, which already exists in a six-month-old child and which manifests itself in caution, sympathy, and primary recognition. Although all four types of memory allocated by him do not exist independently of each other, and moreover, they are in close interaction, P.P. Blonsky was able to determine the differences between individual types of memory [2].

P. Blonsky. They were allocated: motor, emotional, figurative, verbal memory. He considered these types of memory as steps of a single genetic series. In particular, in his opinion, emotional memory itself has its basis in sensory memory, which already exists in a six-month-old child and which manifests itself in caution, sympathy, and primary recognition. Although all four types of memory allocated by him do not exist independently of each other, and moreover, they are in close interaction, P.P. Blonsky was able to determine the differences between individual types of memory [2].

In ontogenesis, all types of memory are formed in a child quite early and also in a certain sequence. Later than others, logical memory develops and begins to work, or, as P.P. sometimes called it. Blonsky, "memory-story". It is already present in a child of 3-4 years of age in relatively elementary forms, but it reaches a normal level of development only in adolescence and youth. Its improvement and further improvement are connected with teaching a person the basics of science.

P.P. Blonsky believed that the beginning of figurative memory is associated with the second year of life, which reaches its highest point only by adolescence. Earlier than others, about 6 months old, affective memory begins to manifest itself, and the very first in time is motor, or motor, memory. In genetic terms, it precedes all others [2].

Figurative is the main type of memory in preschool age. Its development and restructuring are associated with changes taking place in various areas of the child's mental life. The improvement of analytic-synthetic activity entails the transformation of representation.

The preschool period is the era of the dominance of natural, direct, involuntary memory. The preschooler retains the dependence of memorizing material on such features as emotional attractiveness, brightness, sonority, discontinuity of action, movement, contrast, etc. The elements of voluntary behavior are the main achievement of preschool age.

An important moment in the development of a preschooler's memory is the emergence of personal memories. By the end of preschool childhood, the child has elements of arbitrary memory. Arbitrary memory manifests itself in situations where the child independently sets a goal: to remember and remember.

By the end of preschool childhood, the child has elements of arbitrary memory. Arbitrary memory manifests itself in situations where the child independently sets a goal: to remember and remember.

However, the fact that memory develops most intensively in a preschooler compared to other abilities does not mean that one should be satisfied with this fact. On the contrary, it is necessary to develop the child's memory as much as possible at a time when all factors are conducive to this. Therefore, we can talk about the development of a child's memory from early childhood.

It is known for certain: these years should not be missed, otherwise an irreversible process takes place. Lost time - lost opportunities to easily and painlessly learn the main thing for this age. Preschoolers are unusually sensitive to various kinds of influences, and if we do not notice the results of some influences, then this does not mean that they do not mean anything. Children, like a sponge, absorb impressions and knowledge, but do not immediately give out results [21].

In young children, the image is created on the basis of practical action, and then shaped in speech. In older preschoolers, the image arises on the basis of mental analysis and synthesis.

Improvement of actions with objects, their automation and implementation based on an ideal model - a memory image - allow the baby to join such complex types of labor activity as labor in nature and manual. The child qualitatively performs instrumental actions, which are based on fine differentiation of movements, specialized fine motor skills - embroider, sew, etc. [40].

It is possible to single out stages in the development of figurative memory in children aged 3-7 years (Afonkina Yu. A.) [1]:

- At the first stage, the child accepts a mnemonic goal from an adult and treats it as his usual requirement.

- On the second - under the influence of the task to memorize, he begins to use specific means and techniques.

- On the third stage, he independently sets a mnemonic goal and achieves it, self-regulation arises.

Thus, in children up to the age of 3-4 years, memory is predominantly unintentional: the child does not know how to set a goal to remember-remember, does not know the methods and techniques of memorization and reproduction.

From the age of 4-5, arbitrary memorization begins to form and acquire great importance. The transition from involuntary to arbitrary memory involves two stages. At the first stage, the necessary motivation is formed, i.e. the desire to remember or remember something. At the second stage, the mnemonic actions and operations necessary for this arise and are improved.

Consider the features of the development of figurative memory in preschool age.

Visual figurative memory is formed by the beginning of the younger preschool age. The earlier appearance of figurative memory does not mean its subsequent disappearance and replacement by verbal memory. Initially, the images of preschoolers are vague and schematic, but by the older preschool age, they become more meaningful and differentiated, which contributes to the generalization and systematization of images [1].

At 3-4 years of age, memory processes remain involuntary. Recognition still prevails. The amount of figurative memory essentially depends on whether the material is linked into a semantic whole or is scattered. Children of this age at the beginning of the year can memorize two objects with the help of visual-figurative, as well as auditory verbal memory, by the end of the year - up to four objects.

The child remembers well everything that is of vital interest to him, causes a strong emotional response. The information that he sees and hears many times is firmly assimilated. Motor figurative memory is well developed: it is better to remember what was associated with one's own movement.

At the age of 4-5, random reproduction processes begin to develop. Having decided to remember something, the child can now use some actions for this, such as repetition. By the end of the fifth year of life, independent attempts to elementary systematize figurative material appear in order to memorize it.

Arbitrary memorization and recall of images are facilitated if the motivation for these actions is clear and emotionally close to the child (for example, remember what toys are needed for the game, learn a poem as a gift for mom, etc.). At the same time, it is important that the child, with the help of an adult, comprehend what he is learning. Meaningful material is remembered even when the goal is not to remember it. Meaningless elements are easily remembered only if the material attracts children with its rhythm, or, like counting rhymes, woven into the game, becomes necessary for its implementation.

The structure of arbitrary mnemonic action in a preschooler, according to Afonkina Yu.A., has the following components: motivational-targeted, operational, anticipatory, evaluative. Moreover, the leading one is the first of them [1].

Yu. A. Afonkina identified the stages of development of arbitrary figurative memory in children aged 5-6 years. At the first stage, the child accepts a mnemonic goal from an adult and treats it as his usual requirement. On the second - under the influence of the task to remember, he begins to use specific means and techniques. On the third stage, he independently sets a mnemonic goal and achieves it, self-regulation arises [1].

On the second - under the influence of the task to remember, he begins to use specific means and techniques. On the third stage, he independently sets a mnemonic goal and achieves it, self-regulation arises [1].

The volume of figurative memory gradually increases, and the child of the fifth year of life reproduces more clearly what he has remembered.

At this age, children memorize up to 7-8 names of objects. Arbitrary memorization begins to take shape; children are able to accept a memorization task, remember instructions from adults, can learn a short poem, etc. [27].

At the age of 5-6, a child is able to memorize 5-6 objects with the help of figurative-visual memory. The volume of auditory verbal memory is 5–6 words [10].

By the end of the preschool period (6--7 years old) he already knows how to examine objects, can conduct purposeful observation, voluntary attention arises, and as a result, elements of arbitrary figurative memory appear. Arbitrary memory manifests itself in situations where the child independently sets a goal: to remember and remember. It can be said with certainty that the development of arbitrary memory begins from the moment when the child independently singled out the task for memorization [10].

It can be said with certainty that the development of arbitrary memory begins from the moment when the child independently singled out the task for memorization [10].

From early childhood, the process of developing a child's memory goes in several directions. First, mechanical memory is gradually supplemented and replaced by logical memory. Secondly, over time, direct memorization turns into indirect memorization, associated with the active and conscious use of various mnemonic techniques and means for memorization and reproduction. Thirdly, involuntary memorization, which dominates in childhood, becomes voluntary in an adult.

Thus, in the development of memory in general, two genetic lines can be distinguished: its improvement in all civilized people, without exception, as social progress progresses, and its gradual improvement in a single individual in the process of his socialization, familiarization with the material and cultural achievements of mankind.

During preschool age, as shown by A. A. Lyublinskaya, there is a transition [21]:

A. Lyublinskaya, there is a transition [21]:

- from single representations obtained in the process of perceiving one specific object, to operating with generalized images;

- from an "illogical", emotionally neutral, often vague, vague image, to which there are no main parts, but only random, insignificant details in their incorrect relationship, to an image that is clearly differentiated, logically meaningful, causing a certain attitude of the child to it ;

- from an undivided, fused static image to a dynamic display used by older preschoolers in various activities;

- from operating with separate representations torn from each other to reproducing holistic situations, including expressive, dynamic images, that is, reflecting objects in a variety of connections.

The main indicators of the formation of figurative memory in preschool age can be considered: volume, recognition, reproduction, memorization, learning dynamics.

The amount of figurative memory of a preschooler ranges from 2 units (at the younger preschool age) to 5-7 units at the senior preschool age [27, 30].

According to R.S. Nemov at preschool age, the optimal period for a child to recognize an image is approximately 50–70 seconds [26].

N. A. Kornienko's research is devoted to comparing the memorization of subject (figurative) and verbal material in children of preschool age. The subjects - preschool children - were asked to memorize and then reproduce: in some cases, a number of objects (toys) that are easily divided into semantic groups (first series), in other cases, the same number of words that have a specific meaning (second series). series), in the third - the names of trees and shrubs not familiar to children (third series). In similar experiments, where memorization was tested not by reproduction, but by recognition, in addition to the three series indicated, a fourth series was introduced, in which the children memorized (and then recognized) a set of leaves of various trees and shrubs unfamiliar to them.

The results of the experiment showed: 1) in all age groups (in junior, middle and senior preschool age) the highest indicators (in reproduction and recognition) were obtained in experiments with memorizing objects; 2) the second place was taken by the memorization of words of a specific meaning; 3) memorization of unfamiliar names, as well as leaves of unfamiliar trees and shrubs, was the least productive; 4) the difference between all cases of memorization decreased with age. 5) the differences between the productivity of memorizing various types of material in experiments with reproduction turned out to be much more pronounced than in experiments with recognition (where all indicators were, of course, noticeably higher than those obtained in experiments with reproduction), and at the same time they were significantly close to each other [fifteen].

5) the differences between the productivity of memorizing various types of material in experiments with reproduction turned out to be much more pronounced than in experiments with recognition (where all indicators were, of course, noticeably higher than those obtained in experiments with reproduction), and at the same time they were significantly close to each other [fifteen].

Istomina Z.M. believes that in the early and middle preschool age, memorization and reproduction are not independent processes, but only part of a particular activity, that is, involuntary.

In addition, at the senior preschool age, there is a transition from involuntary memory to the initial stages of voluntary memorization and recall. In this case, there is a differentiation of a special kind of actions that correspond to the goals of remembering, recalling, which are set before the children. Active selection and awareness of mnemonic goals by a child occurs in the presence of appropriate motives [14].

The study of children's ideas, according to A.A. Lyublinskaya, shows that several of their levels should be distinguished, according to how they characterize the degree of mastery of the stored images by the child:

1. The level of recognition. The child has retained the idea of the object only to such an extent that he can recognize it when re-perceiving a nature or image.

2. Recalled (passive) playback level. In response to familiar questions (description, riddles), the child has the desired image: “Who is red, fluffy, carries chickens, covers his tracks with his tail?”

The same ideas arise under the influence of some kind of push from outside: the teacher brought in sailor's hats - the children had ideas about sailors and the ship. Such representations are based on associations by similarity or adjacency. Such a reliance on the perception of specific objects is absolutely necessary for the activity of the recreating imagination in preschoolers.

3. The level of free, arbitrary use of existing representations. The preservation of meaningful images, their clarification and differentiation allow older children to use their ideas in games, drawings, and stories.

The level of free, arbitrary use of existing representations. The preservation of meaningful images, their clarification and differentiation allow older children to use their ideas in games, drawings, and stories.

4. At the highest level of creative reproduction, a person can dismember the preserved image and, highlighting only some of its parts, elements, features, include them in new combinations, new combinations, thus creating new pictures, figures, ornaments, stories . Such new images are used by older children and adults in various types of their creative activities [21].

Thus, figurative memory is a memory for representations; memorization, preservation and reproduction of images of previously perceived objects and phenomena of reality.

In general, the following features of the development of memory in preschool age can be distinguished:

- involuntary figurative memory predominates;

- memory, more and more united with speech and thinking, acquires an intellectual character;

- verbal-semantic memory provides indirect cognition and expands the scope of the child's cognitive activity;

- the elements of arbitrary memory are added up as the ability to regulate this process, first on the part of an adult, and then on the part of the child himself;

- prerequisites are formed for turning the process of memorization into a special mental activity, for mastering logical methods of memorization;

- with the accumulation and generalization of the experience of behavior, the experience of the child's communication with adults and peers, the development of memory is included in the development of personality.

During preschool age figurative memory improves: the amount of memory increases, figurative memory is more arbitrary, and the duration of the preservation of images in the child's memory increases.

In the development of figurative memory and imagination of the child during the preschool period there are noticeable shifts, which are expressed in the following:

- The volume of retained representations is increasing.

- Thanks to the culture of perception and ideas about objects and phenomena, schematic, fused and diffuse in babies, they become more and more meaningful, clear and differentiated. At the same time, they are becoming more and more generalized.

- Views become coherent and systemic. They can be combined into groups, categories or pictures.

- The mobility of stored images is growing. The child can freely use them in different activities and in different situations.

- Becoming meaningful, representations are more and more subject to control. Older preschoolers can arbitrarily call them and combine them in accordance with a specific task. The reproducing imagination acquires a creative character.

Older preschoolers can arbitrarily call them and combine them in accordance with a specific task. The reproducing imagination acquires a creative character.

Formation of sound analysis of words in preschool children

Zhurova L.E.

Formation of sound analysis of words in preschool children.

During the first years In the life of a child, a complex process of development of perception takes place. This process has very important, as it creates the necessary basis for everything subsequent development.

One one of the early developing sensory processes is phonemic hearing. Analysis works devoted to the sound side of the development of a child's speech (I.Kh. Shvachkin, A.I. Gvozdev, etc.), shows that, as as a rule, the formation of phonemic hearing ends very early - by two years - as evidenced by the child's complete phonemic distinction of all sounds of the native language. The fact that the speech of a two-year-old child in its own way sound composition differs sharply from the speech of an adult, replete with various kinds irregularities and inaccuracies, researchers of children's speech explain "motor causes" (A. I. Gvozdev), i.e. imperfection of the child's articulation.

I. Gvozdev), i.e. imperfection of the child's articulation.

Again the question of the development of phonemic hearing in a child arises when teaching children literacy. All researchers involved in the problems of psychological readiness children to acquire literacy note the inability of children 6-7 years of age perform a sound analysis of the word. This is the inability of older preschoolers to decompose many researchers are inclined to explain the word into its constituent sounds by the fact that the child does not hear in a word.

We we face a peculiar paradox: with on the one hand, proven by numerous studies, the possibility of a very subtle distinction of sound complexes by the child, which is already formed by two years, and, on the other hand, the inability of a child of senior preschool age "hear" a single sound within a word. The question arises whether these two abilities of the child characteristic of the same process? Is it possible the child's inability to single out a single sound in a word is explained by the fact that he does not hears this sound, that he has insufficiently developed phonemic hearing? The first chapter of the dissertation is devoted to clarifying these issues. Fine phonemic perception of the child, the ability to distinguish by ear all the features of the speech of the adults around him is a necessary basis for highlighting a sound in a word, but does not create skills make such a selection. The task of sound analysis of words in front of the child itself he never gets up on his own, because to communicate with others he does not you need to be able to break the word into its constituent sounds. The Need for Skill analyze the sound composition of a word occurs only when learning to read and write, and it was caused by the specifics of sound-letter writing, which consists in the possibility accurately record speech, using any larger units of speech for this, than sound. When teaching literacy, therefore, one should teach the child the ability to break our speech to sounds. But in the practice of his verbal communication, the child never deals with isolated sounds, which, as N.I. Zhinkin, are not pronounceable at all.

Fine phonemic perception of the child, the ability to distinguish by ear all the features of the speech of the adults around him is a necessary basis for highlighting a sound in a word, but does not create skills make such a selection. The task of sound analysis of words in front of the child itself he never gets up on his own, because to communicate with others he does not you need to be able to break the word into its constituent sounds. The Need for Skill analyze the sound composition of a word occurs only when learning to read and write, and it was caused by the specifics of sound-letter writing, which consists in the possibility accurately record speech, using any larger units of speech for this, than sound. When teaching literacy, therefore, one should teach the child the ability to break our speech to sounds. But in the practice of his verbal communication, the child never deals with isolated sounds, which, as N.I. Zhinkin, are not pronounceable at all.

Research, conducted under the direction of D. B. Elkonin (works by N.A. Khokhlova, A.E. Olshannikova and others), show that under certain conditions, children of the older preschoolers accept the task of sound analysis of words and with the help of data them means of materializing the sound composition words (diagram of the sound composition of words and chips) successfully with this task cope. However, our preliminary experiments showed that the children of the younger and middle preschool age cannot produce a sound analysis of the word, using as a means the scheme of the sound composition of the word and chips. Than can this be explained? Apparently, that form of sound modeling composition of the word, which is offered by D. B. Elkonin, is the modeling of the spatio-temporal structure of the sound form of the word - is difficult for children of younger and secondary preschool age. What is this complexity? The fact is that decomposing the word into sounds, depriving it of its usual syllabic pronunciation, pronouncing each syllable by sounds, we completely distort the word, its meaning at the same time is lost.

B. Elkonin (works by N.A. Khokhlova, A.E. Olshannikova and others), show that under certain conditions, children of the older preschoolers accept the task of sound analysis of words and with the help of data them means of materializing the sound composition words (diagram of the sound composition of words and chips) successfully with this task cope. However, our preliminary experiments showed that the children of the younger and middle preschool age cannot produce a sound analysis of the word, using as a means the scheme of the sound composition of the word and chips. Than can this be explained? Apparently, that form of sound modeling composition of the word, which is offered by D. B. Elkonin, is the modeling of the spatio-temporal structure of the sound form of the word - is difficult for children of younger and secondary preschool age. What is this complexity? The fact is that decomposing the word into sounds, depriving it of its usual syllabic pronunciation, pronouncing each syllable by sounds, we completely distort the word, its meaning at the same time is lost. Naturally, a preschool child refuses work with such a "decayed" word. The scheme and the chips do not help him "collect" the sound pattern of the word, hear it the way the child is used to hear this word in the practice of their verbal communication.

Naturally, a preschool child refuses work with such a "decayed" word. The scheme and the chips do not help him "collect" the sound pattern of the word, hear it the way the child is used to hear this word in the practice of their verbal communication.

Proceeding from the theory of the formation of mental actions, D.B. Elkonin, forming preschoolers the action of the sound analysis of words, introduced at the stage of mastering the action with chips and a scheme with objects, as if he materialized the word and the sounds that make it up. But, working with chips and a diagram, the child pronounces the word he is parsing in the same way as he does in his speech practice. And since the sound form of the word is some structural formation, then the pronunciation of each sound in the word due to the environment in which it is located, what sounds are ahead and behind. When we perform a sound analysis of a word, we destroy this structure and the sound "m" that the child hears, for example, in the word "mother" has a very little in common with the separately named sound "me".

We suggested that in order to teach a preschool child the action of sound analysis words, it is necessary to find such a way of dismembering the structure of the word, in which the specificity of sound pronunciation would be preserved, due to its position in word.

So before the introduction of modeling the spatio-temporal composition of the word, it is necessary teach the child to model a special type - by changing the process pronunciation of the word - modeling the word in natural ways, already available to the child. With normal pronunciation, our speech, as shown in his research N.I. Zhinkin is quantized into syllables. We need to teach child to a special pronunciation of the word, so that already at the very pronunciation of the child singled out the sound he needed, that is, the word should be pronounced by the child, quantized Not for syllables, but for sounds. For example, if we want the child to produce sound analysis of the word "poppy", then we must teach him to pronounce this word so: “m-m-poppy” - to highlight the first sound, “m-a-a-a-k” - to highlight the second sound and “poppy-to-to” - to highlight the third sound. In this case, the articulation the child begins to play a completely new, special role, it acquires an independent meaning, begins to perform the function of orientation in the word. Of such kind articulation is not natural for a child and it must be specially taught. We called this way of pronouncing the word intonation. Voice function At the same time, the child’s activity changes, turning from a function of communication, transferring thoughts to the function of examining the sound composition of the word.

In this case, the articulation the child begins to play a completely new, special role, it acquires an independent meaning, begins to perform the function of orientation in the word. Of such kind articulation is not natural for a child and it must be specially taught. We called this way of pronouncing the word intonation. Voice function At the same time, the child’s activity changes, turning from a function of communication, transferring thoughts to the function of examining the sound composition of the word.

We considered, however, that the introduction of this simpler type of modeling the sound composition of a word - natural modeling - cannot unambiguously determine success conducting a sound analysis of words by all preschool children, which there are special age and individual characteristics that make it possible to accept task and means of sound analysis of words and act in a certain way or not allowing it. This assumption can be tested apparently on two lines:

1. The degree of deployment with which children of this age will be administered means of sound analysis of words. This is indicative of how the child, carrying out sound analysis of words, needs the help of an experimenter, and what that help is. 2. The value of the heterogeneity of speech material, which will be given to children for sound analysis: the position of the emitted sound in word (first-last), articulatory characteristic of the emitted sound. Since in the method of intonation, which we have chosen as a means of sound analysis of words, the main role belongs to a particular pronunciation, word articulation, correct or incorrect articulation of individual sounds can be a decisive factor in the ability to child to make a sound analysis of words.

The degree of deployment with which children of this age will be administered means of sound analysis of words. This is indicative of how the child, carrying out sound analysis of words, needs the help of an experimenter, and what that help is. 2. The value of the heterogeneity of speech material, which will be given to children for sound analysis: the position of the emitted sound in word (first-last), articulatory characteristic of the emitted sound. Since in the method of intonation, which we have chosen as a means of sound analysis of words, the main role belongs to a particular pronunciation, word articulation, correct or incorrect articulation of individual sounds can be a decisive factor in the ability to child to make a sound analysis of words.

So, the following questions were posed in the study:

1. Is the intonational selection of sounds in a word

a means, with with the help of which preschool children can master the action of sound word analysis.

2. What are the age and individual differences are revealed in the mastery of this tool and what stages its formation goes through.

What are the age and individual differences are revealed in the mastery of this tool and what stages its formation goes through.

Experimental the situation in which preschool children will learn to act sound analysis of words, must meet two requirements:

1. The task of extracting a sound in a word should be placed in an interesting and accessible situation for a child of any preschool age. It is known that children of senior and middle preschool age easily accept the task even when it is presented to them as a training task, without game design. But in order for children from 3 to 5 years old to accept complex, practically unnecessary task of sound analysis, it is necessary to introduce this task into a game situation and, moreover, to make sound analysis a means to solve the main game problem.

2. Children should be given clear instructions on how to select sound in a word as such a method, we took the intonation selection of sound in the word. That is, the children had to be taught special pronunciation of the word, in which the division of the structure of the word is not would change the specifics of the pronunciation of a single sound.

Sound analysis task cannot be set to junior and middle preschoolers in the form of a description of their future activities. She can only be entered using a specific pattern. At the same time, it is important that the sample is given to the child not as a finished product, but in the process of its construction, giving particular importance to the method of carrying out activities - intonation.

Experiments were carried out with children of kindergarten No. 253 Moscow for 10 people 3-4, 4-5 and 5-6 years old.

Second chapter of the dissertation is devoted to the presentation of the methodology and results of the study of the formation of the sound analysis of words in preschool children.

In the first series of experiments, the experimenter first of all explained using the example of the name of the subject, what is the first sound in the word. to the subject showed how to pronounce a word in order to highlight the first sound in it intonation: “I-and-igor”.

Then began an experiment in which the child had to name the first sound in the name ten animals (dog, cat, squirrel, bear, horse, etc.). experimental the situation was as follows: in front of the subject was placed a house surrounded by a "river" with bridge thrown over it. It was only possible to cross the bridge to the house correctly naming the first sound in the name of the walker, otherwise the bridge broke. The subject had to lead all the animals into the house, calling the first sound of their name

In the second series of experiments in the same experimental situation the child had to name the last sound in the name of each animal.

Analysis of the results of the experiments performed gives reason to conclude that the method of intonational sound isolation in a word, which we gave to our subjects as a means of conducting a sound analysis was successful.

All subjects, including three-year-old children age, coped with the task of highlighting the first sound in the word. True, three year olds instead of naming the isolated first sound, they gave its intonational selection, but it is important for us that the task of highlighting a sound in a word was accepted by the kids, and the children used the means of sound analysis given to them.

True, three year olds instead of naming the isolated first sound, they gave its intonational selection, but it is important for us that the task of highlighting a sound in a word was accepted by the kids, and the children used the means of sound analysis given to them.

Intonation, seems to be a convenient way to find and listen to the desired sound (more on this evidenced by the fact that all three-year-old children, after listening as an experimenter emphasizes intonationally the first sound, they were able to name it in isolation), but articulatory, it is difficult for younger preschoolers. That is why in those cases when the experimenter ceased to provide assistance in intonation highlighting the sound, the children switched all their attention to correctly articulate the desired sound (intonate it), and could no longer move on to isolated sound naming. All this was especially clearly manifested precisely in series I, since the task of isolating the last sound in a word, staged in the II series, turned out to be for the younger preschoolers are so complex that we can trace some patterns there failed: all subjects simply refused to answer on their own, limited to repeating what the experimenter said.

Children 4-5 years, having easily mastered the method of intonational emphasis as a means sound analysis, were able to identify both the first and last sound in all the words he proposed. Truth, the task of isolating the first sound turned out to be easier for them, the proof what is the independent intonational emphasis of the first sound with the subsequent its isolated naming in 33 cases out of a total of 100 (10 subjects, 10 words each), while the independent intonational emphasis of the last sound was made only 7 times. But all children in this age group were able to independently name the last sound in a word, based on intonational emphasis this sound given by the experimenter.

B the group of children aged 5-6 years for the first time there are cases (40 percent) of the allocation of the first sound in a word without its preliminary intonational emphasis. Does it mean that, that for children of middle preschool age, intonation as a means of sound analysis is already becoming obsolete and children can move on to other forms of modeling the sound composition of a word? The data of the second series of experiments show us that such a conclusion is incorrect: all those subjects who did not use the intonational emphasis of the first sound in order to distinguish it from the word, not only intonate the last sound, but sometimes they even turn to the experimenter for help, not knowing how cope with the task on their own.

Process isolating a sound in a word is a complex activity, during the formation of which the child goes through a series of successive stages, located in a certain genetic sequence. We have called these stages the stages of mastery. the action of sound analysis of words. At stage I, a child needs the help of the experimenter as much as possible: he cannot independently still cope neither with the intonational release of sound, nor with its isolated naming, repeating both only after the experimenter. Child, who is at this initial stage, is only learning something new for him articulation - intonation.

On the next, II stage, children are still not have a way of intonation. They need the help of an experimenter in intonation selection of the desired sound and cannot name the sound in isolation, based on their own intonation. However, after listening intonation selection of sound by the experimenter, children can independently call this sound in isolation. Assistance at Stage III the experimenter is still needed by the child for the intonational isolation of sound in word, but, having learned to intonate the desired sound, children call it in isolation, focusing already on their own pronunciation of a word. At stage IV, children absolutely do not resort to the help of the experimenter: they themselves easily change their articulation, pronouncing the word so as to listen to the desired sound, and then call it isolated. At the 5th stage it is impossible observe the process of making sound analysis of the word: the activity has been formed, the process has been curtailed - the child pronounces the word without resorting to the intonational selection of the desired sound, and after beyond that names the sound in isolation. But, apparently, even at this highest level average preschoolers "to themselves" resort to intonation. About it is evidenced by the fact that none of our subjects named the allocated sounds with a generalized name of a sound like "me", "be", but always kept at of the emitted sound, the specificity, which is determined by the position of this sound in word. For example, in the words “bear” and “walrus”, the sound “m” sounds differently: a soft phoneme in the first case and solid in the second.

At stage IV, children absolutely do not resort to the help of the experimenter: they themselves easily change their articulation, pronouncing the word so as to listen to the desired sound, and then call it isolated. At the 5th stage it is impossible observe the process of making sound analysis of the word: the activity has been formed, the process has been curtailed - the child pronounces the word without resorting to the intonational selection of the desired sound, and after beyond that names the sound in isolation. But, apparently, even at this highest level average preschoolers "to themselves" resort to intonation. About it is evidenced by the fact that none of our subjects named the allocated sounds with a generalized name of a sound like "me", "be", but always kept at of the emitted sound, the specificity, which is determined by the position of this sound in word. For example, in the words “bear” and “walrus”, the sound “m” sounds differently: a soft phoneme in the first case and solid in the second. When naming an isolated first sound in these words all our subjects retained this softness and firmness.

When naming an isolated first sound in these words all our subjects retained this softness and firmness.

The level of mastering the activity is determined clearly the age of the subject. It also depends on the position of the sound in a word (first-last). When the last sound in the word is selected, all our subjects moved to a lower level of activity in comparison with isolating the first sound. Table 1 (see page 9) shows in percentage, how the answers of the subjects in the I and II series of experiments are distributed over the steps of activity. Great importance when highlighting a sound in a word, its articulatory characteristic also has. At it is very important that children do not experience any difficulties in isolating late assimilated and poorly articulated sounds - l, r, s, sh, f. All these sounds easily intoned and then called in isolation. If the subject is unable to pronounce any of these sounds, he pronounces the sound instead - substitute, and it does not interfere with sound analysis. We have a completely different picture. we see when a child should highlight a sound that is difficult to intonate - b, e, j. All subjects immediately turn to the experimenter for help, passing, thus, to a lower level of activity to isolate the sound in the word.

We have a completely different picture. we see when a child should highlight a sound that is difficult to intonate - b, e, j. All subjects immediately turn to the experimenter for help, passing, thus, to a lower level of activity to isolate the sound in the word.

Table 1

| Age test subjects | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | IV stage | V stage | |||||

| 1 series | 2 series | 1 series | 2 series | 1 series | 2 series | 1 series | 2 series | 1 series | 2 series | |

| 3-4 years | 39 | 92 | 58 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4-5 years | 7 | 5 | 55 | 88 | 33 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 5 - 6 years | 0 | 1 | 22 | 30 | 2 | 39 | 18 | 30 | 40 | 0 |

This indicates that the mechanism of sound analysis lies in the ability do an articulatory work different from that which the child does in his ordinary speech. Physiological readiness of the auditory and articulatory apparatus does not lead directly to the ability to conduct a sound analysis of words? Children's inability primary and secondary preschool age to make a sound analysis of words is not associated with physiological deficiencies of the auditory and articulatory devices, but with their lack of an appropriate mode of activity.

Physiological readiness of the auditory and articulatory apparatus does not lead directly to the ability to conduct a sound analysis of words? Children's inability primary and secondary preschool age to make a sound analysis of words is not associated with physiological deficiencies of the auditory and articulatory devices, but with their lack of an appropriate mode of activity.

So, we found that although intonation is the optimal means for highlighting sounds in a word by children of preschool age, but introducing it into as a means of sound analysis of words does not always give an unambiguous positive result. Successful use by preschool children intonation selection of sound in a word for the purpose of sound analysis due to their age characteristics and the nature of that speech material, which is given to children for analysis.

B 1 and 2 series of experiments, the selection of sound in a word was a means for children to solve the main game problem. At the same time, the activity of isolating sound in we had to specially form the word for our subjects. In the third series of experiments, the children were offered the actual speech game, process game with the word, in which the child had to realize the practical significance of the semantics of sound (in particular, 1 sound in word), any training in this series was removed.

In the third series of experiments, the children were offered the actual speech game, process game with the word, in which the child had to realize the practical significance of the semantics of sound (in particular, 1 sound in word), any training in this series was removed.

Subjects five identical dolls were offered, dressed in shirts of different colors. According to the color of the shirt, the dolls were named Jean (yellow shirt), Ban (white shirt), Kang (red shirt), Zan (green shirt) and San (blue shirt) shirt). The children had to learn to recognize the dolls by their names. Experiences were held in kindergarten No. 1065 in Moscow. For experiments, 10 children 6-7 years old, 18 children 5-6 years old and 16 children 4-5 years old.

All The subjects were divided into two groups: 1) coped with the task and 2) failed on the task. Since the behavior in the experiment of children included in one of the groups was exactly the same, regardless of age, we will present the results of the 3rd series of experiments not by age group, but by method actions. Group I included all subjects 6-7 years, seven subjects 5-6 years old and two subjects 4-5 years old. All these kids didn't during the experiments, not a single mistake, all the dolls were named correctly, and before naming the doll, the children called the color of her jacket: “Green, Zan."

Group I included all subjects 6-7 years, seven subjects 5-6 years old and two subjects 4-5 years old. All these kids didn't during the experiments, not a single mistake, all the dolls were named correctly, and before naming the doll, the children called the color of her jacket: “Green, Zan."

Subjects, included in the II group, could not isolate the relationship between the color of the jacket and the name of the doll. Even the introduction of intonation by the experimenter ("S-s-blue jacket - S-s-san") did not lead to a positive result.

Results III series of experiments turned out to be significantly lower than the results of series I. If in series I the task of highlighting the first sound in a word was completed all children, then in the III series of subjects 4-5 years old the task was completed by only 12 percent, and 5-6 years old - by 39 percent of children. Such the big difference, it seems to us, can be explained by the fact that in series III modeling by a child was completely excluded the sound composition of the word. If in series I intonation, which we offered to children, gave them the opportunity, as it were, to “feel” the first sound in a word, to dwell on it, then in the III series this possibility was excluded, the children were not taught by us way of isolating a sound in a word. Thus, even if sound analysis is the subject of the child's activity, children of the middle children of preschool age do not cope independently with the isolation of sound in a word. To conduct sound analysis, it is necessary to give children the means to perform this task, to teach them a special way of pronouncing a word with a modified articulation - intonation.

If in series I intonation, which we offered to children, gave them the opportunity, as it were, to “feel” the first sound in a word, to dwell on it, then in the III series this possibility was excluded, the children were not taught by us way of isolating a sound in a word. Thus, even if sound analysis is the subject of the child's activity, children of the middle children of preschool age do not cope independently with the isolation of sound in a word. To conduct sound analysis, it is necessary to give children the means to perform this task, to teach them a special way of pronouncing a word with a modified articulation - intonation.

Intonation sound isolation in a word is the means by which children preschool children can distinguish a certain sound in a word. intonation differs from normal, natural articulation in that it breaks natural syllabic way of pronouncing words. In the formation of this new actions with the word, the existing articulatory-syllabic pronunciation stereotype, natural syllabic quantization is overcome words, the child learns to control his own articulatory apparatus. Expanded pronunciation of a word with underlined, intoned, extended pronouncing individual sounds performs the function of orientation in the sound word composition. Thus, the pronunciation of a word from a performing action, serving communication, turns into a special, investigating sound composition the words. Isolation of a separate sound with emphasized intonation pronunciation leads to hearing it as a separate sound. Like any mental action, this action is formed as the most expanded, and then gradually abbreviated and transformed into an abbreviated, produced "in the mind"; rather, produced with silent, silent, without visible articular movements internal speaking.

Expanded pronunciation of a word with underlined, intoned, extended pronouncing individual sounds performs the function of orientation in the sound word composition. Thus, the pronunciation of a word from a performing action, serving communication, turns into a special, investigating sound composition the words. Isolation of a separate sound with emphasized intonation pronunciation leads to hearing it as a separate sound. Like any mental action, this action is formed as the most expanded, and then gradually abbreviated and transformed into an abbreviated, produced "in the mind"; rather, produced with silent, silent, without visible articular movements internal speaking.

However this creates only the necessary conditions for the sound analysis of the word. Sound word analysis involves not only the selection of a separate sound on the basis of pronunciation or recognition of a sound given in the form of a sample in a word. The main thing in sound analysis of the word - the establishment of relationships between the sounds that make up word. So, for example, the words "cat", "current" and "who" consist of the same sounds. But these are different words, and they are different precisely because the same sounds make up in them every time a peculiar structure, consisting in that temporal sequence, in which these sounds follow each other.

So, for example, the words "cat", "current" and "who" consist of the same sounds. But these are different words, and they are different precisely because the same sounds make up in them every time a peculiar structure, consisting in that temporal sequence, in which these sounds follow each other.

Using intonation, children of any preschool age, starting from the age of three, can distinguish the first sound in the word. But for conducting a complete sound analysis of the word, as shown by our preliminary experiments, intonation alone is not enough. Arises the need to teach children to combine more elemental, natural modeling the sound composition of a word (intonation) with a more complex, subject modeling proposed by D.B. Elkonin (sound diagram composition of words and chips).

A question of preschool education sound analysis of words is now becoming especially relevant in connection with introducing literacy elements into the Kindergarten Curriculum. Literacy classes are introduced in the preparatory group of the kindergarten (6-7 years). It is clear that if it were possible to transfer the training in sound analysis to the senior kindergarten group (5-6 years old), this would greatly facilitate the assimilation of reading in the preparatory group. We taught the action of full sound analysis of words senior group of children of kindergarten No. 1065 (teacher L.N. Eliseeva) with subsequent teaching of this group to read. The training took place in group sessions lasting 20 minutes each. Was used for training experimental primer created by D.B. Elkonin for schooling. The description of this training and its analysis is given in the third chapter of the dissertation.

It is clear that if it were possible to transfer the training in sound analysis to the senior kindergarten group (5-6 years old), this would greatly facilitate the assimilation of reading in the preparatory group. We taught the action of full sound analysis of words senior group of children of kindergarten No. 1065 (teacher L.N. Eliseeva) with subsequent teaching of this group to read. The training took place in group sessions lasting 20 minutes each. Was used for training experimental primer created by D.B. Elkonin for schooling. The description of this training and its analysis is given in the third chapter of the dissertation.

On We spent 17 twenty-minute sessions completely working out the action of the sound analysis of words. As a result of the training, it was found out what role the words play in the sound analysis by a five-year-old child, intonation, chips and a scheme of the sound composition of a word.

Intonation the selection of sound in a word is a means for conducting sound analysis, a way actions with the form of the word. The introduction of intonational emphasis on sounds for the first time gives the child the opportunity to isolate the form of the word as something different from the content, and select units in the form of a word - sounds. The effectiveness of intonation is explained in that it allows you to highlight sounds without destroying the structure of the form (i.e., the specificity of sound pronunciation is preserved, due to its position in word). Isolation of sounds in a word with the help of intonation is preparatory in relation to those forms of word modeling that were proposed D.B. Elkonin. This is due to the fact that the replacement of sound with a chip that is not similar to the sound being replaced, is a very high and complex form modeling approaching in its character to iconic modeling. AT Therefore, when working with younger children, there is the need to create the prerequisites for a higher stage by teaching children intonation highlight sounds and thus create a natural sound pattern composition of the word, obviously similar to the reproduced sample.

The introduction of intonational emphasis on sounds for the first time gives the child the opportunity to isolate the form of the word as something different from the content, and select units in the form of a word - sounds. The effectiveness of intonation is explained in that it allows you to highlight sounds without destroying the structure of the form (i.e., the specificity of sound pronunciation is preserved, due to its position in word). Isolation of sounds in a word with the help of intonation is preparatory in relation to those forms of word modeling that were proposed D.B. Elkonin. This is due to the fact that the replacement of sound with a chip that is not similar to the sound being replaced, is a very high and complex form modeling approaching in its character to iconic modeling. AT Therefore, when working with younger children, there is the need to create the prerequisites for a higher stage by teaching children intonation highlight sounds and thus create a natural sound pattern composition of the word, obviously similar to the reproduced sample.

Tokens record the results of such an analysis, and their the spatial arrangement on the diagram models the temporal sequence sounds in a word. Subject activity with chips, allowing any chip rearrange, remove, etc. enables the child to understand that the sounds in words can be rearranged, act with them, as with chips.

Scheme of the sound composition of the word, determining the number sounds in a word, allows the child to check whether the sound is correctly produced analysis of the word, i.e. whether all the sounds in it are highlighted. However, in the event of an error does not allow the child to know exactly what mistake he made, since the chips, the schemes placed in the cells are qualitatively indeterminate. Therefore, fixing mistake, the child must do all the work first, resorting to intonational extraction of sounds.

Teaching this group of children to read made it possible find out what role sound analysis plays in literacy education.

According to Elkonin, the formation of the action of the initial reading, includes three steps: 1) the formation of the action of sound analysis, 2) the formation of the action of inflection, 3) the formation of the action recreating the sound form of a syllable and a word.

Following this scheme, we moved to the second stage in the education of our children - formation of the action of inflection. The first stage of this action is in familiarizing children with the letters denoting vowel sounds - a, o, y, s, and. We introduced the children to these letters for five lessons - in each lesson children were shown one new letter. The second stage of action formation inflections - the formation of the action of changing the sound form of a word when change in one of the vowels that make up its composition. Continuing to teach children reading, using the methodology developed by D.B. Elkonin, we modified it by changing the stage of inflection. The meaning of this stage according to D.B. Elkonin, lies in the fact that, by producing the action of inflection, children, even before acquaintances with consonants, only on the basis of actions with vowels, should learn to recreate the sound form of a syllable, thus bypassing all difficulty merging sounds. Although inflection takes place on the basis of sound analysis, but its principle is different from the principle of sound analysis, since here, as in reading, there is a “reconstruction of the sound form of a word based on its graphic image". That is, between the stage of mastering the action of sound analysis and the stage of the actual reading by D.B. Elkonin inserts the stage of inflection, which is actually learning to read. We have replaced this kind of inflection others based only on the principle of sound analysis. The action of inflection proposed by D.B. Elkonin, lies in the fact that children who have disassembled the word with using sound analysis, it was proposed to change the vowel in it and say, what is the new word succeed. That is, acting in this way, the child performs an action similar to reading in the sense that he had to "read" a new word unknown to him.

Although inflection takes place on the basis of sound analysis, but its principle is different from the principle of sound analysis, since here, as in reading, there is a “reconstruction of the sound form of a word based on its graphic image". That is, between the stage of mastering the action of sound analysis and the stage of the actual reading by D.B. Elkonin inserts the stage of inflection, which is actually learning to read. We have replaced this kind of inflection others based only on the principle of sound analysis. The action of inflection proposed by D.B. Elkonin, lies in the fact that children who have disassembled the word with using sound analysis, it was proposed to change the vowel in it and say, what is the new word succeed. That is, acting in this way, the child performs an action similar to reading in the sense that he had to "read" a new word unknown to him.

At this stage, we gave word to the child and asked what sound needs to be replaced in it in order to receive such and such a specific, named word. Thus the word that should result from a change in the vowel sound, the child already knows he does not have to "recreate" its sound form on his own. In this case the child is dealing with the task of sound analysis: he must, having produced in his mind a sound analysis of both words given to him, to find out in what sound they differ from each other friend, and, finding these sounds, change them. Giving our children inflection in this form, we continued to train them in conducting sound analysis of words without teaching them anything else. So Thus, we were able to find out whether the ability to produce sound analysis words sufficient so that children of 5-6 years of age, having become acquainted with letters, immediately began to read. By introducing children to consonants, we found that all our subjects easily add any word consisting of from the letters they know, that is, they write it, but they cannot read it. The reason for this phenomenon lies in the fact that when folding from a split alphabet, the child actually does all the same sound analysis, only instead of chips puts letters.

Thus the word that should result from a change in the vowel sound, the child already knows he does not have to "recreate" its sound form on his own. In this case the child is dealing with the task of sound analysis: he must, having produced in his mind a sound analysis of both words given to him, to find out in what sound they differ from each other friend, and, finding these sounds, change them. Giving our children inflection in this form, we continued to train them in conducting sound analysis of words without teaching them anything else. So Thus, we were able to find out whether the ability to produce sound analysis words sufficient so that children of 5-6 years of age, having become acquainted with letters, immediately began to read. By introducing children to consonants, we found that all our subjects easily add any word consisting of from the letters they know, that is, they write it, but they cannot read it. The reason for this phenomenon lies in the fact that when folding from a split alphabet, the child actually does all the same sound analysis, only instead of chips puts letters. In this case, the child moves sequentially from the first sound to to the last and, therefore, from the first letter to the last. Reading is based on the exact opposite principle. When reading, as D.B. Elkonin, "in connection with the peculiarities of Russian consonantism (the presence of hard and soft consonants) to recreate the correct sound form of the word when choosing a phoneme and its variant, denoted by a letter, requires orientation to the subsequent given consonant vowel. Recreation of the sound form of a syllable and a word in Russian language is impossible without such an orientation. That is, when reading a syllable the child should read as if "back to front" - first look at the pas following vowel, then return to the consonant that preceded it, and only then read the syllable. That way of forming the action of inflection, which offers D.B. Elkonin introduces the child to the principle of positional reading before the child starts reading: in a word with one vowel, which the child “reads” at the same time, he gets used to reading the word, focusing not on the consonant, but on the vowel.

In this case, the child moves sequentially from the first sound to to the last and, therefore, from the first letter to the last. Reading is based on the exact opposite principle. When reading, as D.B. Elkonin, "in connection with the peculiarities of Russian consonantism (the presence of hard and soft consonants) to recreate the correct sound form of the word when choosing a phoneme and its variant, denoted by a letter, requires orientation to the subsequent given consonant vowel. Recreation of the sound form of a syllable and a word in Russian language is impossible without such an orientation. That is, when reading a syllable the child should read as if "back to front" - first look at the pas following vowel, then return to the consonant that preceded it, and only then read the syllable. That way of forming the action of inflection, which offers D.B. Elkonin introduces the child to the principle of positional reading before the child starts reading: in a word with one vowel, which the child “reads” at the same time, he gets used to reading the word, focusing not on the consonant, but on the vowel.

We deprived our subjects of this stage, thanks to which they received in their purest form moving from sound analysis to spelling. As a result, we can do conclusion: the actions of sound analysis of words, no matter how well it was worked out, far from enough to form a reading. The other side of learning is based on the sound analysis of words literacy - a letter that becomes orthographically correct only under the condition working out the action of sound analysis (we do not have here, of course, in mind the rules grammar). To teach reading, it is necessary to introduce children to by the principle of positional reading. Continuing the training of this group, we taught children to the principle of positional reading. For this, we used D. B. Elkonin manual, which he calls "strip". This is a piece of cardboard which has four slots. By setting in one window a letter denoting consonant sound (any), in the next window, in turn, change the letters denoting vowel sounds. All possible syllables with a given letter pass in front of the child - ha, go, tu, gy, gi. Because the consonant is fixed and therefore unchanged, the child involuntarily looks at changing vowel, thus acquiring the positional principle of reading.

Because the consonant is fixed and therefore unchanged, the child involuntarily looks at changing vowel, thus acquiring the positional principle of reading.

After such training with "Strip" (and from working with it, acquaintance with each new letter began) The children began to read very quickly.

For 60 20 minute sessions (including 18 sound training sessions) analysis of words and 11 lessons on the formation of a method of inflection, which in fact, they were a continuation of classes on working out the action of sound analysis words).

In the light of our findings, we must to state that in the course of preschool education, the child's capabilities in relation to his awareness of the sound side of the word is far from being fully used. In our children's institutions with children of preschool age do not work, associated with the sound characteristic of speech (an exception is speech therapy Work).

We showed that preschool children in certain situations take the task of formal speech analysis - the analysis of speech sounds - and successfully with it cope. Therefore, it would seem appropriate to train children's sound analysis of words at preschool age. Taking advantage of the special sensitivity of a child of primary preschool age to the sound side speech, relying on this "special linguistic talent", you need to teach children the way intonation selection of sound in a word already at a younger preschool age, C with the help of various kinds of "rhymes" you can organize special speech activities with children games, the purpose of which is to highlight a certain sound in words. So Thus, by the age of five, you can teach children a new way for them activities needed to teach literacy. Children who know the method of intonation highlighting a sound in a word, easily assimilate the action of a complete sound analysis words. All this will make it possible to completely transfer the teaching of elementary reading from schools to kindergarten.

Therefore, it would seem appropriate to train children's sound analysis of words at preschool age. Taking advantage of the special sensitivity of a child of primary preschool age to the sound side speech, relying on this "special linguistic talent", you need to teach children the way intonation selection of sound in a word already at a younger preschool age, C with the help of various kinds of "rhymes" you can organize special speech activities with children games, the purpose of which is to highlight a certain sound in words. So Thus, by the age of five, you can teach children a new way for them activities needed to teach literacy. Children who know the method of intonation highlighting a sound in a word, easily assimilate the action of a complete sound analysis words. All this will make it possible to completely transfer the teaching of elementary reading from schools to kindergarten.

Conducted the study allows us to draw the following conclusions:

1. The practice of verbal communication the child does not set before him the task of sound analysis of words, which arises only in connection with literacy.

The practice of verbal communication the child does not set before him the task of sound analysis of words, which arises only in connection with literacy.