Is reading an activity

25 Activities for Reading and Writing Fun

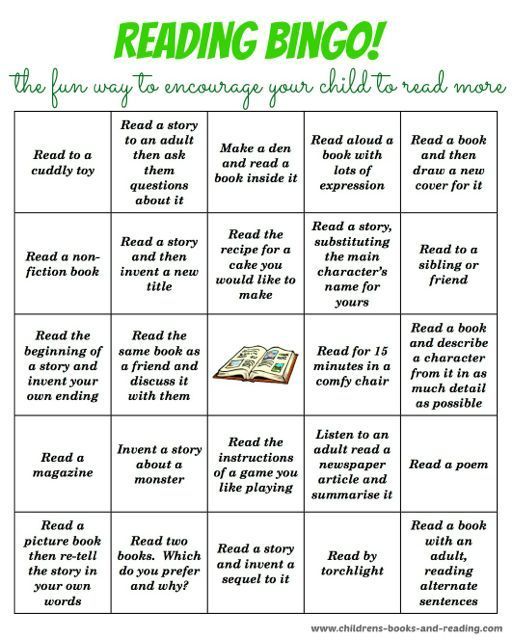

These activities have been developed by national reading experts for you to use with children, ages birth to Grade 6. The activities are meant to be used in addition to reading with children every day.

In using these activities, your main goal will be to develop great enthusiasm in the reader for reading and writing. You are the child's cheerleader. It is less important for the reader to get every word exactly right. It is more important for the child to learn to love reading itself. If the reader finishes one book and asks for another, you know you are succeeding! If your reader writes even once a week and comes back for more, you know you have accomplished your beginning goals.

Activities for birth to preschool: the early years

Activity 1: Books and babies

Babies love to listen to the human voice. What better way than through reading!

What you'll need:

Some books written especially for babies (books made of cardboard or cloth with flaps to lift and holes to peek through).

What to do:

- Start out by singing lullabies and folk songs to your baby. When your baby is about six months old, choose books with brightly colored, simple pictures and lots of rhythm in the text. (Mother Goose rhymes are perfect.) Hold your baby in your lap so he/she can see the colorful pages of the book. Include books that show pictures and names of familiar objects.

- As you read with your baby, point out objects in the pictures and make sure your baby sees all the things that are fun to do with books. (Pat the Bunny by Dorothy Kunhardt is a classic touch-and-feel book for babies.)

- Vary the tone of your voice with different characters in the stories, sing nursery rhymes, make funny faces, do whatever special effects you can to stimulate your baby's interest.

- Allow your child to touch and hold cloth and sturdy cardboard books.

- When reading to a baby, keep the sessions brief but read daily and often.

As you read to your baby, your child is forming an association between books and what is most loved – your voice and closeness. Allowing babies to handle books deepens their attachment even more.

Allowing babies to handle books deepens their attachment even more.

Activity 2: Tot talk

What's "old hat" to you can be new and exciting to toddlers and preschoolers. When you talk about everyday experiences, you help children connect their world to language and enable them to go beyond that world to new ideas.

What you'll need:

Yourself and your child

What to do:

- As you get dinner ready, talk to your child about things that are happening. When your 2- or 3-year-old "helps" by taking out all the pots and pans, talk about them. "Which one is the biggest?" "Can you find a lid for that one?" "What color is this one?"

- When walking down the street and your toddler or preschooler stops to collect leaves, stop and ask questions that require more than a "yes" or "no" answer. "Which leaves are the same?" "Which leaves are different?" "What else grows on trees?"

- Ask "what if" questions. "What would happen if we didn't shovel the snow?" "What if that butterfly lands on your nose?"

- Answer your child's endless "why" questions patiently.

When you say, "I don't know, let's look it up," you show how important books are as resources for answering questions.

When you say, "I don't know, let's look it up," you show how important books are as resources for answering questions. - After your child tells you a story, ask questions so you can understand better. That way children learn how to tell complete stories and know you are interested in what they have to say.

- Expose your child to varied experiences – trips to the library, museum, or zoo; walks in the park; or visits with friends and relatives. Surround these events with lots of comments, questions, and answers.

Talking enables children to expand their vocabulary and understanding of the world. The ability to carry on a conversation is important for reading development. Remember, it is better to talk too much rather than too little with a small child.

Activity 3: R and R – repetition and rhyme

Repetition makes books predictable, and young readers love knowing what comes next.

What you'll need:

- Books with repeated phrases (Favorites are: Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day by Judith Viorst; Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? by Bill Martin, Jr.

; Horton Hatches the Egg by Dr. Seuss; and The Little Engine That Could by Watty Piper.

; Horton Hatches the Egg by Dr. Seuss; and The Little Engine That Could by Watty Piper. - Short rhyming poems.

What to do:

- Pick a story with repeated phrases or a poem you and your child like. For example, read:

(Wolf voice:) "Little pig, little pig, let me come in."

(Little pig:) "Not by the hair on my chinny-chin-chin."

(Wolf voice:) "Then I'll huff and I'll puff and I'll blow your house in!" - After the wolf has blown down the first pig's house, your child will soon join in with the refrain.

- Read slowly, and with a smile or a nod, let your child know you appreciate his or her participation.

- As the child grows more familiar with the story, pause and give him or her a chance to fill in the blanks and phrases.

- Encourage your child to pretend to read, especially books that contain repetition and rhyme. Most children who enjoy reading will eventually memorize all or parts of a book and imitate your reading.

This is a normal part of reading development.

This is a normal part of reading development.

When children anticipate what's coming next in a story or poem, they have a sense of mastery over books. When children feel power, they have the courage to try. Pretending to read is an important step in the process of learning to read.

Activity 4: Poetry in motion

When children "act out" a good poem, they learn to love its rhyme, rhythm, and the pictures it paints with a few well-chosen words. They grow as readers by connecting feelings with the written word.

What you'll need:

Poems that rhyme, tell a story, and/or are written from a child's point of view.

What to do:

- Read a poem slowly to your child, and bring all your dramatic talents to the reading. (In other words, "ham it up.")

- If there is a poem your child is particularly fond of, suggest acting out a favorite line. Be sure to award such efforts with delighted enthusiasm.

- Suggest acting out a verse, a stanza, or the entire poem.

Ask your child to make a face the way the character in the poem is feeling. Remember that facial expressions bring emotion into the performer's voice.

Ask your child to make a face the way the character in the poem is feeling. Remember that facial expressions bring emotion into the performer's voice. - Be an enthusiastic audience for your child. Applause is always nice.

- If your child is comfortable with the idea, look for a larger setting with an attentive, appreciative audience. Perhaps an after-dinner "recital" for family members would appeal to your child.

- Mistakes are a fact of life, so ignore them.

Poems are often short with lots of white space on the page. This makes them manageable for new readers and helps to build their confidence.

Activity 5: Story talk

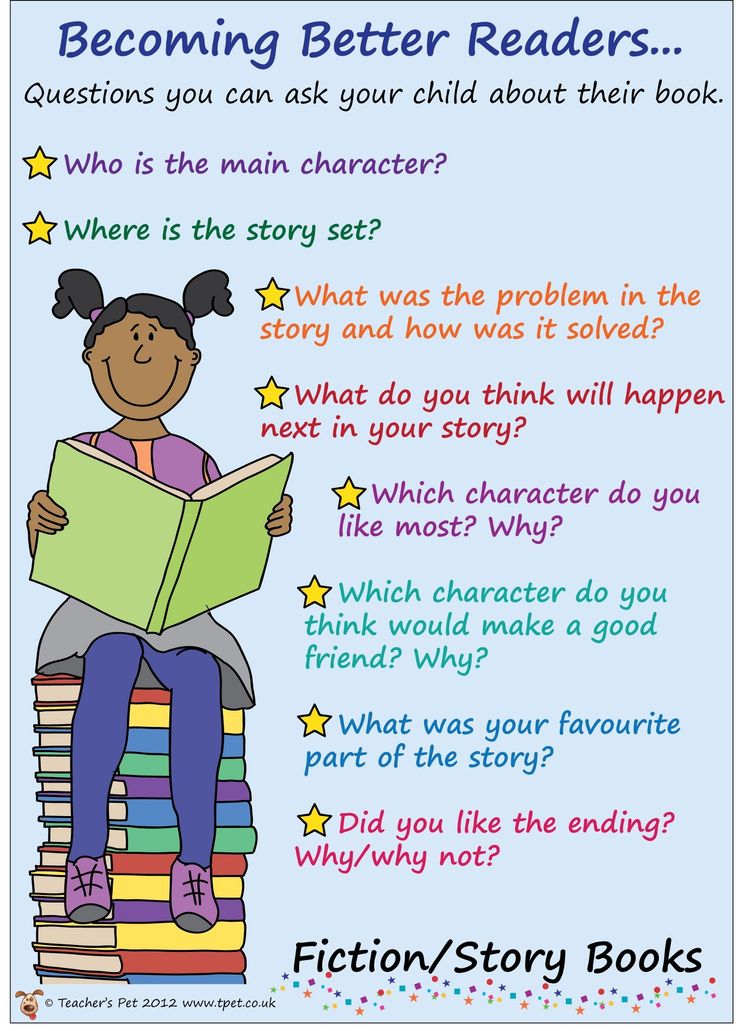

Talking about what you read is another way to help children develop language and thinking skills. You won't need to plan the talk, discuss every story, or expect an answer.

What you'll need:

Storybooks

What to do:

- Read slowly and pause occasionally to think aloud about a story. You can say: "I wonder what's going to happen next!" Or ask a question: "Do you know what a palace is?" Or point out: "Look where the little mouse is now.

"

" - Answer your children's questions, and if you think they don't understand something, stop and ask them. Don't worry if you break into the flow of a story to make something clear. But keep the story flowing as smooth as possible.

- Talking about stories they read helps children develop their vocabularies, link stories to everyday life, and use what they know about the world to make sense out of stories.

Activity 6: Now hear this

Children are great mimics. When you tell stories, your child will begin to tell stories, too.

What you'll need:

Your imagination

What to do:

- Have your child tell stories like those you have told. Ask: "And then what happened?" to urge the story along.

- Listen closely when your child speaks. Be enthusiastic and responsive. Give your child full attention.

- If you don't understand some part of the story, take the time to get your child to explain. This will help your child understand the relationship between a speaker and a listener and an author and a reader.

- Encourage your child to express himself or herself. This will help your child develop a richer vocabulary. It can also help with pronouncing words clearly.

Having a good audience is very helpful for a child to improve language skills, as well as confidence in speaking. Parents can be the best audience a child will ever have.

Activity 7: TV

Television can be a great tool for education. The keys to successful TV viewing are setting limits, making good choices, taking time to watch together, discussing what you view, and encouraging follow-up reading.

What you'll need:

A weekly TV schedule

What to do:

- Limit your child's TV viewing and make your rules and reasons clear. Involve your child in choosing which programs to watch. Read the TV schedule together to choose.

- Monitor what your child is watching, and whenever possible, watch the programs with your child.

- When you watch programs with your child, discuss what you have seen so your child can better understand the programs.

- Look for programs that will stimulate your child's interests and encourage reading (such as dramatizations of children's literature and programs on wildlife and science.)

Many experts recommend that children watch no more than 10 hours of TV each week. Limiting TV viewing frees up time for reading and writing activities.

It is worth noting that captioned TV shows can be especially helpful for children who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, studying English as a second language, or having difficulty learning to read.

Activities for preschool to grade two: moving into reading

Check out Reading Rockets' new summer website, Start with a Book. You'll find a treasure trove of themed children's books, parent–child activities, and other great resources for summer learning.

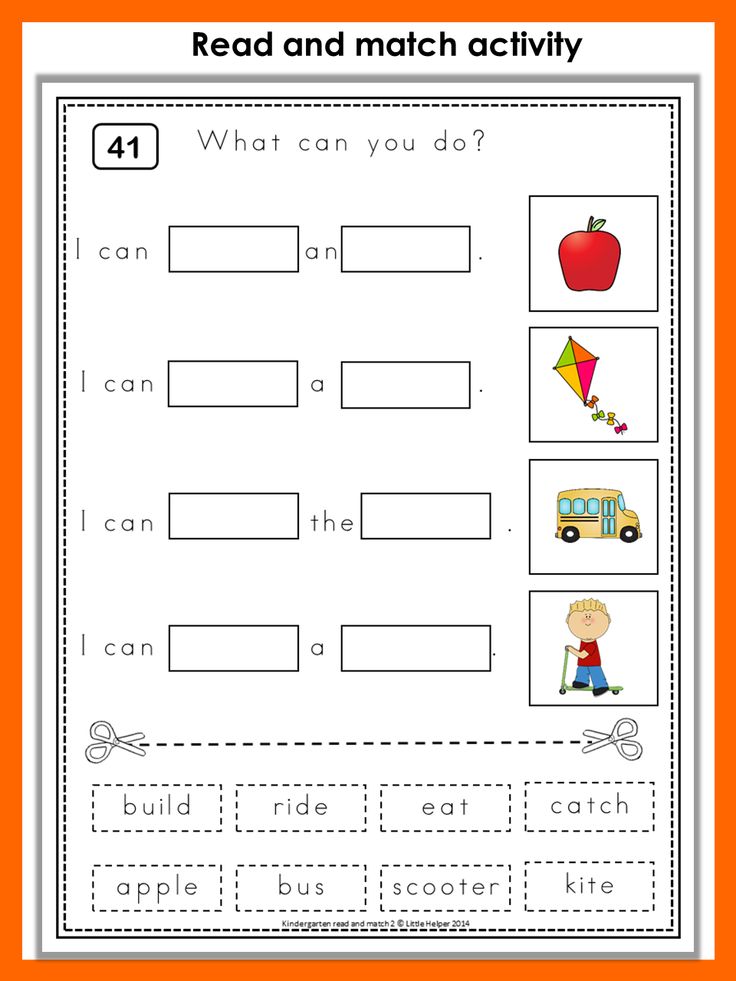

Activity 8: World of words

Here are a few ways to create a home rich in words.

What you'll need:

- Paper

- Pencils, crayons, markers

- Glue

- Newspapers, magazines

- Safety scissors

What to do:

- Hang posters of the alphabet on the bedroom walls or make an alphabet poster with your child.

Print the letters in large type. Capital letters are usually easier for young children to learn first.

Print the letters in large type. Capital letters are usually easier for young children to learn first. - Label the things in your child's pictures. If your child draws a picture of a house, label it with "This is a house." and put it on the refrigerator.

- Have your child watch you write when you make a shopping list or a "what to do" list. Say the words aloud and carefully print each letter.

- Let your child make lists, too. Help your child form the letters and spell the words.

- Look at newspapers and magazines with your child. Find an interesting picture and show it to your child as you read the caption aloud.

- Create a scrapbook. Cut out pictures of people and places and label them.

- By exposing your child to words and letters often, your child will begin to recognize the shapes of letters. The world of words will become friendly.

Activity 9: Write on

Writing helps a child become a better reader, and reading helps a child become a better writer.

What you'll need:

- Pencils, crayons, or markers

- Paper or notebook

- Chalkboard and chalk

What to do:

- Ask your child to dictate a story to you. It could include descriptions of your outings and activities, along with mementos such as fall leaves and flowers, birthday cards, and photographs. Older children can do these activities on their own.

- Use a chalkboard or a family message board as an exciting way to involve children in writing with a purpose.

- Keep supplies of paper, pencils, markers, and the like within easy reach.

- Encourage beginning and developing writers to keep journals and write stories. Ask questions that will help children organize the stories, and respond to their questions about letters and spelling. Suggest they share the activity with a smaller brother, sister, or friend.

- Respond to the content of children's writing, and don't be overly concerned with misspellings. Over time you can help your child concentrate on learning to spell correctly.

- When children begin to write, they run the risk of criticism, and it takes courage to continue. Our job as parents is to help children find the courage. We can do it by expressing our appreciation of their efforts.

Activity 10: Look for books

The main thing is to find books you both love. They will shape your child's first impression of the world of reading.

What you'll need:

Good books

What to do:

- Ask friends, neighbors, and teachers to share the titles of their favorite books.

- Visit your local public library, and as early as possible, get your child a library card. Ask the librarian for help in selecting books. Have your child join you in browsing for books and making selections.

- Look for award-winning books. Each year the American Library Association selects children's books for the Caldecott Medal for illustrations and the Newbery Medal for writing.

- Check the book review section of the newspapers and magazines for the recommended new children's books.

- If you and your child don't enjoy reading a particular book, put it aside and pick up another one.

- Keep in mind that your child's reading level and listening level are different. When you read easy books, beginning readers will soon be reading along with you. When you read more advanced books, you instill a love of stories, and you build the motivation that transforms children into lifelong readers.

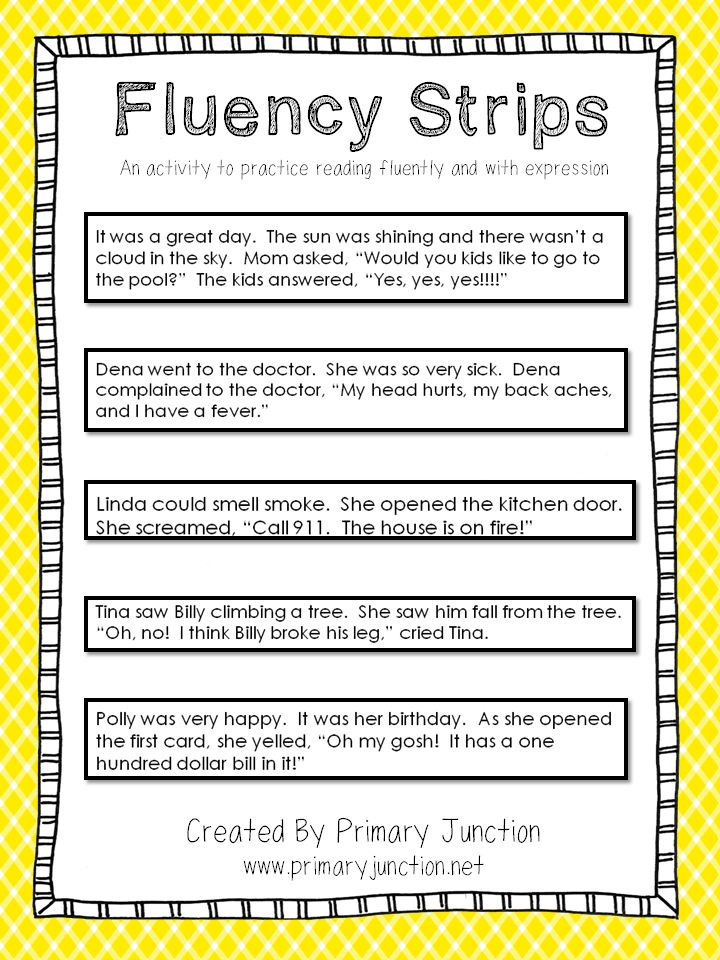

Activity 11: Read to me

It's important to read to your child, but equally important to listen to them read to you. Children thrive on having someone appreciate their developing skills.

What you'll need:

Books at your child's reading level

What to do:

- Listen carefully as your child reads.

- Take turns. You read a paragraph and have your child read the next one or you read half the page and your child reads the other half. As your child becomes more at ease with reading aloud, take turns reading a full page. Keep in mind that your child may be focusing more on how to read the words than what they mean, and your reading helps to keep the story alive.

- If your child has trouble reading words, you can help him or her in several ways:

- Ask the child to skip over the word, read the rest of the sentence, and then say what would make sense in the story for the missing word.

- Guide the child to use what he or she knows about letter sounds.

- Supply the correct word.

- Tell your child how proud you are of his or her efforts and skills.

Listening to your child read aloud provides opportunities for you to express appreciation of his or her new skills and for them to practice their reading. Most importantly, this is another way to enjoy reading together.

Activity 12: Family stories

Family stories enrich the relationship between parent and child.

What you'll need:

Time set aside for talking with your child.

What to do:

- Tell your child stories about your parents and grandparents. You might even put these stories in a book and add old family photographs.

- Have your child tell you stories about what happened on special days, such as holidays, birthdays, and family vacations.

- Reminisce about when you were little. Describe things that happened at school involving teachers and subjects you were studying. Talk about your brothers, sisters, or friends.

- Write a trip journal with your child to create a new family story. Recording the day's events and pasting the photographs into the journal ties the family story to a written record. You can include everyday trips like going to the market or the park.

- It helps for children to know that stories come from real people and are about real events. When children listen to stories, they hear the voice of the storyteller. This helps them hear the words when they learn to read aloud or read silently.

Activity 13: P.S. I love you

Something important happens when children receive and write letters. They realize that the printed word has a purpose.

What you'll need:

- Paper

- Pencil, crayon, or marker

What to do:

Language is speaking listening, reading, and writing. Each element supports and enriches the others. Sending letters will help children become better writers, and writing will make them better readers.

Activities for grades 3–6: encouraging the young reader

Activity 14: Good books make reading fun

Stories for young children should be of all kinds – folktales, funny tales, exciting tales, tales of the wondrous and stories that tell of everyday things.

What you'll need:

A variety of interesting books

What to do:

- An essential step in learning to read is good books read aloud. Parents who read aloud to their children are teaching literacy concepts simply by sharing books. Encourage your children to listen, ponder, make comments, and ask questions.

- Be flexible enough to quickly abandon a book that does not appeal after a reasonable try at reading it.

No one is meant to enjoy every book. And no one, especially a child, should be forced to read or listen to books that bore.

No one is meant to enjoy every book. And no one, especially a child, should be forced to read or listen to books that bore. - Even after children have outgrown picture books they still enjoy hearing a story read aloud. Hearing a good story read well, especially if it is just a little beyond a child's own capabilities, is an excellent way to encourage independent reading. Not all books are best read aloud; some are better enjoyed silently.

- There are plenty of children's books that are twice as satisfying when they are shared a chapter at a time before bed or during long car rides. There are some books that children should not miss, books that they will want to hear many times and ultimately read for themselves.

- Young children want to read what makes them laugh or cry, shiver and gasp. They must have stories and poems that reflect what they themselves have felt. They need the thrill of imagining, of being for a time in some character's shoes for a spine-tingling adventure.

They want to experience the delight and amazement that comes with hearing playful language. For children, reading must be equated with enjoying, imagining, wondering, and reacting with feeling. If not, we should not be surprised if they refuse to read. So let your child sometime choose the story or book that they want you to read to them.

They want to experience the delight and amazement that comes with hearing playful language. For children, reading must be equated with enjoying, imagining, wondering, and reacting with feeling. If not, we should not be surprised if they refuse to read. So let your child sometime choose the story or book that they want you to read to them.

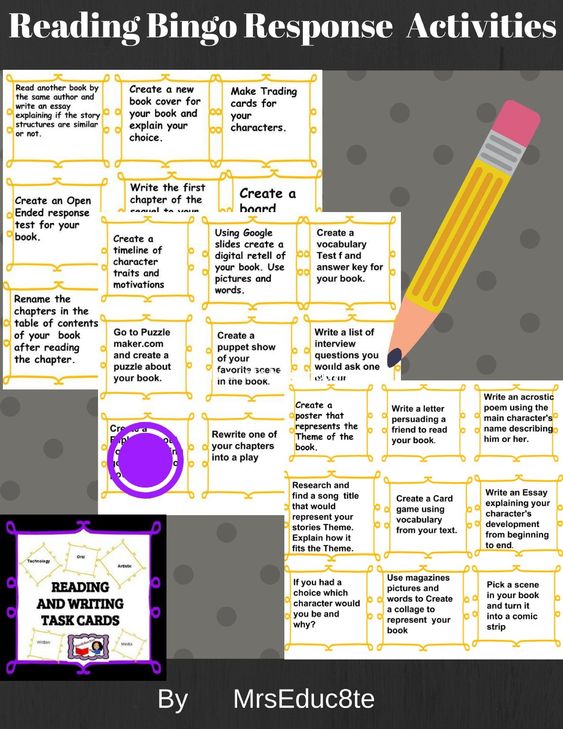

Give your child many opportunities to read and write stories, lists, messages, letters, notes, and postcards to relatives and friends. Since the skills for reading and writing reinforce one another, your child's skills and proficiency in reading and writing will be strengthened if you help your child connect reading to writing and writing to reading.

Activity 15: Artful artists

Children love to be creative when it comes to drawing, and illustrations add visual imagery to stories.

What you'll need:

- Drawing paper

- Pens and pencils

- Magic markers or crayons

What to do:

Find a fable, fairy tale, or other short story for your child to read. Then ask your child to illustrate a part of the story he or she likes best or describe a favorite character. Have the child dictate or write a few sentences that tell about this picture.

Then ask your child to illustrate a part of the story he or she likes best or describe a favorite character. Have the child dictate or write a few sentences that tell about this picture.

Activity 16: Shopping your way with words

Use your weekly shopping trip as an opportunity to help your child develop reading and writing skills.

What you'll need:

- Paper and pencils

- Newspaper ads

- Supermarket coupons

What to do:

As you make out your grocery shopping list, give your child a sheet of paper and read the items to him or her. If the child asks for spelling help, write the words correctly for him or her to copy or spell the words aloud as your child writes them.

Ask your child to look through the newspaper ads to find the prices of as many items as possible. Your child can write these prices on the list and then look through your coupons to select the ones you can use. Take your child to the supermarket and ask him or her to read each item to you as you shop.

Activity 17: Cookbooking

Cooking is always a delight for children, especially when they can eat the results!

What you'll need:

- Easy-to-read recipes

- Cooking utensils

- Paper and pencils

What to do:

Show your child a recipe and go over it together. Ask your child to read the recipe to you as you work, and tell the child that each step must be done in a special order. Let your child help mix the ingredients. Allow your child to write down other recipes from the cookbook that he or she would like to help make.

Activity 18: Dictionary words

A dictionary is a valuable learning tool, especially if your child makes up his or her own booklet of words that are challenging.

What you'll need:

- Paper and pencils

- A stapler

- Old magazines

- Newspaper and supplements

What to do:

Encourage your child to make a dictionary by putting together several sheets of paper for a booklet. Ask your child to write at the top of each page a new word he or she has recently learned. If the word can be shown in a picture, have him or her look through magazines and newspapers to find pictures that illustrate the words and paste them on the correct pages.

Ask your child to write at the top of each page a new word he or she has recently learned. If the word can be shown in a picture, have him or her look through magazines and newspapers to find pictures that illustrate the words and paste them on the correct pages.

Have your child write the meaning of each word and a sentence using each new word. Your child can then use some or all of these sentences as the basis for a creative story. Have your child read this story to you and other family members.

Activity 19: Journals

Keeping a journal is a way for your child to write down daily events and record his or her thoughts.

What you'll need:

Two notebooks - one for your child and one for you!

What to do:

Help your child start a journal. Say what it is and discuss topics that can be written about, such as making a new friend, an interesting school or home activity just completed, or how your child felt on the first day of school. Encourage your child to come up with other ideas. Keep a journal yourself and compare notes at the end of the week. You and your child each can read aloud parts of your journals that you want to share.

Keep a journal yourself and compare notes at the end of the week. You and your child each can read aloud parts of your journals that you want to share.

Activity 20: Greetings and salutations

Everyone loves to get mail, especially when the card has been personally designed.

What you'll need:

- Paper and pencils

- Crayons and magic markers

- Stamps and envelopes

What to do:

Ask your child to list the birthdays of family members, relatives, and friends. Show your child some store-bought birthday cards with funny, serious, or thought-provoking messages. Your child can then create his or her own birthday card by using a folded piece of paper, making an attractive cover, and writing a short verse inside. Then your child can mail the cards to friends and relatives for their birthdays.

Activity 21: Giving the gift of reading

Reading a book is more fun when you have a homemade bookmark to mark your spot.

What you'll need:

- Pieces of lightweight cardboard

- Pens and pencils

- Paper

- Crayons and magic markers

What to do:

Provide your child with a piece of cardboard about 6" long and 2" wide. On one side of the bookmark, have your child draw a picture of a scene from a book he or she has read. On the other side, ask your child to write the name of the book, its author, publisher, publication date, and a few sentences about the book. After making several of these bookmarks, you might ask the child to send them to friends and relatives as gifts accompanied by a short note.

On one side of the bookmark, have your child draw a picture of a scene from a book he or she has read. On the other side, ask your child to write the name of the book, its author, publisher, publication date, and a few sentences about the book. After making several of these bookmarks, you might ask the child to send them to friends and relatives as gifts accompanied by a short note.

Activity 22: Let your fingers do the walking

The telephone book contains a wealth of information and is a good tool for reading and writing.

What you'll need:

- A telephone book, including the yellow pages

- Paper and pencils

What to do:

Have your child look through the yellow pages of the telephone directory, select a particular service, and write a clever or funny ad for it. Have your child read this ad to you. Help your child to find your own or a friend's listing in the white pages of the telephone book. Explain the different entries (for example, last name and address), along with the abbreviations commonly used.

Activity 23: Map your way to success

Children love to read road maps and this activity actually helps them with geography.

What you'll need:

- A road map or atlas

- Paper and pencil

- Stamps and envelopes

What to do:

When planning a vacation, let your child see the road map and help you plan where you will drive. Talk about where you will start and where you will end up. Let your child follow the route between these two points. Encourage your child to write to the Chamber of Commerce for brochures about places you will see on your trip.

Activity 24: What's in the news?

Newspapers are a form of daily communication with the outside world, and provide lots of learning activities for children.

What you'll need:

- Newspapers

- Scissors

- Colored pencils

What to do:

- Clip out an interesting news story and cut the paragraphs apart. Ask your child to read the paragraphs and put them in order.

- Ask your child to read a short editorial printed in your local newspaper and to underline all the facts with a green pencil and all the opinions with an orange pencil.

- Pictures fascinate children of all ages. Clip pictures in the newspaper. Ask your child to tell you about the picture or list adjectives to describe the picture.

- Do you take your child to the movies? Have your child first look up the movie page by using the index in the newspaper. After a movie has been chosen, have your child study the picture or text in the ad and tell you what he or she thinks the movie is about.

- Have your child pick a headline and turn it into a question. Then the child can read the article to see if the question is answered.

- Ask your child to clip food coupons from the newspaper for your grocery shopping trips. First, talk about which products you use and which you do not. Then the child can cut out the right coupons and putt hem into categories such as drinks and breakfast items.

You can then cash in the coupons at the store.

You can then cash in the coupons at the store. - Pick out an interesting article from the newspaper. As you are preparing lunch or dinner, tell your child that you are busy and ask him or her to read the article to you.

- Many newspapers publish materials especially written for children, such as the syndicated "Mini Page," "Pennywhistle Press," and "Dynamite Kids." In addition, some newspapers publish weekly columns for children, as well as tabloids and summer supplements written by educators.

Activity 25: Using television to stimulate reading

What child doesn't enjoy watching TV? Capitalize on this form of entertainment and use TV to help rather than hinder your child's learning.

Some important ideas to consider before turning on the TV: Limit in some way the amount of TV your child watches so as to leave time for reading and other activities. Decide how much time should be set aside for watching TV each day.

Serve as an example by limiting the amount of TV you yourself watch. Have time when the TV set is off and the entire family reads something. You may want to watch TV only for special shows. Before the TV set is turned on, encourage your child to select the programs he or she wishes to watch. Ask your child to give you the reason for the choices made.

Have time when the TV set is off and the entire family reads something. You may want to watch TV only for special shows. Before the TV set is turned on, encourage your child to select the programs he or she wishes to watch. Ask your child to give you the reason for the choices made.

In addition, watch some of the same TV programs your child watches. This helps you as a parent share in some of your child's daily activities.

What you'll need:

- A TV

- A TV selection guide

- Colored highlighters

- A calendar page for each month

- Paper and pencils

What to do:

- Ask your child to tell you about favorite TV characters using different kinds of words.

- As your child watches commercials on television, ask him or her to invent a product and write slogans or an ad for it.

- Encourage your child to watch such programs as Reading Rainbow. Urge older children to watch such programs as 60 Minutes and selected documentaries.

These programs are informative. Discuss interesting ideas covered in the programs and direct your child to maps, encyclopedias, fiction, or popular children's magazines for more information.

These programs are informative. Discuss interesting ideas covered in the programs and direct your child to maps, encyclopedias, fiction, or popular children's magazines for more information. - Have your child name 10 of his or her favorite shows. Ask your child to put them into categories according to the type of show they are, such as family shows, cartoons, situation comedies, sports, science fiction, or news and information. If you find the selection is not varied enough, you might suggest a few others that would broaden experiences.

- Prepare a monthly calendar with symbols such as a picture of the sun to represent an outdoor activity or a picture of a book to represent reading. Each time your child engages in a daily free time activity, encourage him or her to paste a symbol on the correct calendar date. This will give you an idea of how your child spends his or her free time. It also encourages a varied schedule.

- Ask each child in your family to pick a different color.

Using the TV listing, have each child use this color to circle one TV program that he or she wants to watch each day. Alternate who gets first choice. This serves two purposes. It limits the amount of time watching TV and it encourages discriminating viewing.

Using the TV listing, have each child use this color to circle one TV program that he or she wants to watch each day. Alternate who gets first choice. This serves two purposes. It limits the amount of time watching TV and it encourages discriminating viewing. - Devise a rating scale from 1 to 5. Ask your child to give a number to a certain TV program and to explain why such a rating was given.

- Have your child keep a weekly TV log and write down five unfamiliar words heard or seen each week. Encourage your child to look up the meanings of these words in the dictionary or talk about them with you.

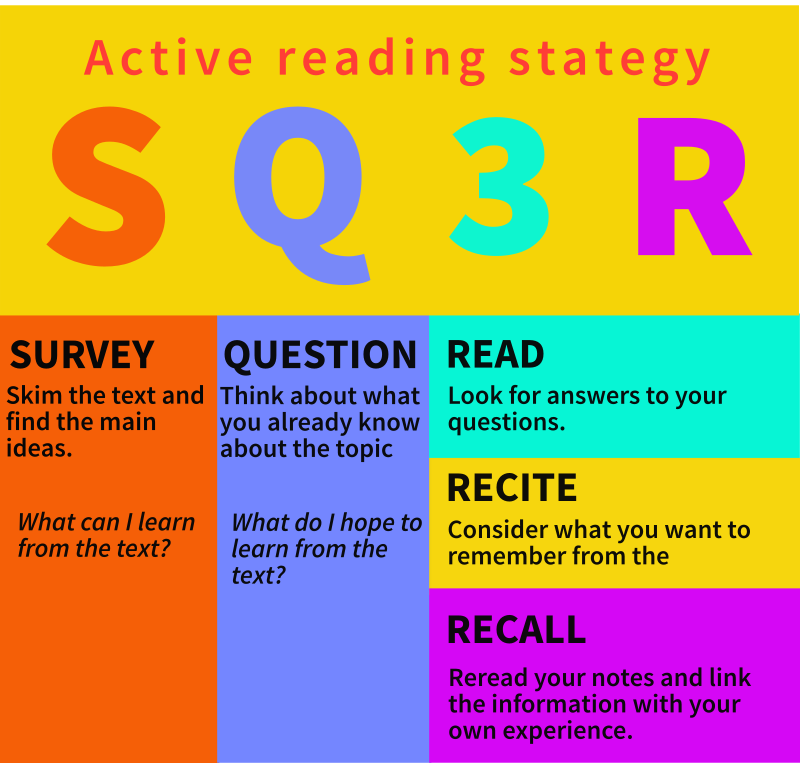

Is Reading an ACTIVE or PASSIVE activity?

When I ask this question in my training sessions, approximately 70% participants says it’s passive and 30% says it’s active. When I ask reason behind their answer, they say it is passive because we are sitting at one place and read the words written by author.

People who say reading is active activity are not able to give any strong reason for their answer. They themselves tend to be confused why they consider reading to be an active activity.

They themselves tend to be confused why they consider reading to be an active activity.

As a reader, let me ask you the same question, is reading is an active activity or passive activity? If active then why ACTIVE and if PASSIVE then why passive? Think on it…

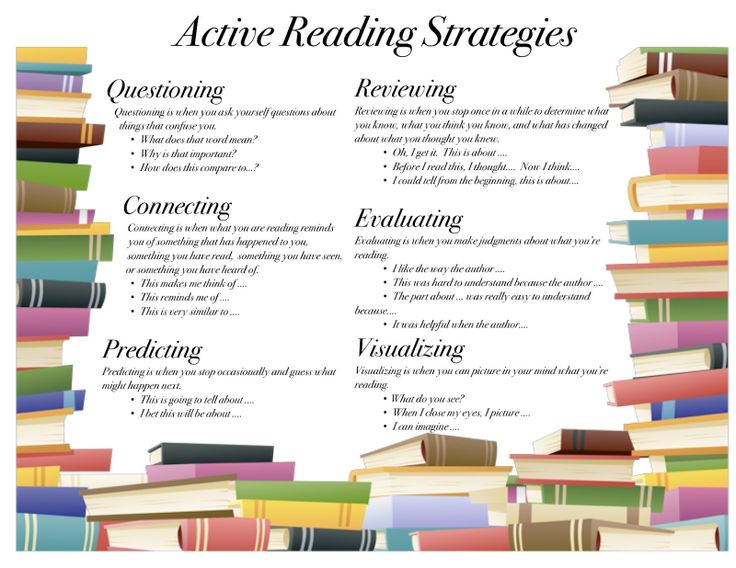

To answer that question I will put an extract from the book “How to Read a book” by Mortimer J. Adler. “Strictly, all reading is active. What we call passive is simply less active. Reading is better or worse according as it is more or less active. And one reader is better than another in proportion as he is capable of a greater range of activity in reading. In order to explain this point, I must first be sure that you understand why I say that, strictly speaking, there is no absolutely passive reading. It only seems that way in contrast to more active reading.

No one doubts that writing and speaking are active undertakings, in which the writer or speaker is clearly doing something. Many people seem to think, however, that reading and listening are entirely passive. No work need be done. They think of reading and listening as receiving communication from someone who is actively giving it. So far they are right, but then they make the error of supposing that receiving communication is like receiving a blow, or a legacy, or a judgement from the court.”

No work need be done. They think of reading and listening as receiving communication from someone who is actively giving it. So far they are right, but then they make the error of supposing that receiving communication is like receiving a blow, or a legacy, or a judgement from the court.”

I have explained it in a simpler way in my manual, “Read to Understand”

“Let me use the example of cricket. Catching the ball is just as much an activity as hitting it. The batsman is the giver here in the sense that his activity initiates the motion of the ball. The catcher or fielder is the receiver in the sense that his activity terminates it. Both are equally active, though the activities are distinctly different. If anything is passive here, it is the ball; it is bowled and caught. It is the inert thing which is written and read, like the ball, is the passive object common to the two activities which begin and terminate the process.

We can go a step further with this analogy. A good catcher is one who stops the ball which has been hit. The art of catching is the skill of knowing how to do this as well as possible in every situation. So the art of reading is the skill of catching every sort of communication as well as possible. But the reader as “catcher” is more like the wicketkeeper. The bowler signals for a particular ball. He knows what to expect. In a sense, the bowler and wicketkeeper are like two men with but a single thought before the ball is thrown. Not so, however, in the case of the batter and fielder. Fielders may wish that batters would obey signals from them, but that isn’t the way game is played. So readers may sometimes wish that writers would submit completely to their desires for reading matter, but the facts are usually otherwise. The reader has to go after what comes out into the field.”

A good catcher is one who stops the ball which has been hit. The art of catching is the skill of knowing how to do this as well as possible in every situation. So the art of reading is the skill of catching every sort of communication as well as possible. But the reader as “catcher” is more like the wicketkeeper. The bowler signals for a particular ball. He knows what to expect. In a sense, the bowler and wicketkeeper are like two men with but a single thought before the ball is thrown. Not so, however, in the case of the batter and fielder. Fielders may wish that batters would obey signals from them, but that isn’t the way game is played. So readers may sometimes wish that writers would submit completely to their desires for reading matter, but the facts are usually otherwise. The reader has to go after what comes out into the field.”

Reading is like catching the ball, and if you ask any fielder whether catching is an active or passive activity; I am sure that he/she will say it is ACTIVE.

Yes, reading is an ACTIVE activity. As reader you should know when to read fast and when to read slow. On which part of your reading material you should focus more and on which part less. How to make sure you are able to connect with the ideas of author and not just with his words.

___________________________________________________________________

To get these kind of short articles and stories via Whatsapp (more than 2100 people receive it) - message your name and "grow" to 91-8286-211-823 (Rupak) and save that number. You will get added to the broadcast list and not a group - so your number never gets shared with anyone.

______________________________________________________________________

How and why do they read our thoughts?

A mind-reading device based on brain activity has already been created: it is a “brain-computer” neural interface.

Reading minds is a fantastic idea, but feasible. How deep have scientists managed to penetrate into the human brain? And how can this option be useful for science and medicine? A guest of the Question of Science program tells the story, professor at Skoltech and Sechenov University, scientific director of the HSE Center for Bioelectrical Interfaces Mikhail Albertovich Lebedev.

What is a thought and how to read it?

In the experimental conditions in which we work, such a unit as one thought can be distinguished. For example, you can set a task for the subject: to choose the right or left picture according to some attribute. A person thinks for a while, hesitates, and finally makes a decision - at this moment his thought is expressed, and we can see what is happening at that time in the brain.

Experimental conditions, as a rule, look like this: there is a stimulus and there is a response. And between them there is a certain rule that the brain uses to translate the stimulus into a response. It is the activity of the brain that translates this stimulus into a response that is thought. It develops, of course: first you need to understand what you were shown, what kind of stimulus, then remember the rule that you need to apply, and, finally, develop an answer. The stimulus, the decision and the response are to some extent a sentence, because the stimulus is in some way the subject, the rules are some kind of adjectives, and already the verb is the decision itself (for example, open the window).

It is the activity of the brain that translates this stimulus into a response that is thought. It develops, of course: first you need to understand what you were shown, what kind of stimulus, then remember the rule that you need to apply, and, finally, develop an answer. The stimulus, the decision and the response are to some extent a sentence, because the stimulus is in some way the subject, the rules are some kind of adjectives, and already the verb is the decision itself (for example, open the window).

A neural interface is a device that reads thoughts from brain activity. For it to work, it is necessary that we can record brain activity and that there are not very many thoughts, otherwise we will not be able to determine which thoughts to read.

It is possible that in the future we will be able to read arbitrary thoughts. Now it is difficult for us, but if we understand the analysis of brain mechanisms further, then, in principle, we will also be able to read arbitrary thoughts, since there is hope that we will be able to isolate individual components, then classify them as belonging to a certain category of thoughts and then restore the whole chain of mental activity.

Now programs that recognize speech work perfectly. So why don't we recognize brain activity the same way we recognize speech? But there is a problem here: when we listen to sound and perceive speech, something is obviously encoded here. If you look at the graph of speech, a sound signal, then you will not be able to determine anything, but if you listen, you will immediately determine. Why? Because you know the code, you understand how to decode. With brain activity, everything is more complicated, because it obviously encodes something, but we simply do not know how it encodes.

There is undoubtedly something in common in the code that will allow deciphering brain activity, because otherwise, if everything was completely individual, we would not be able to understand each other. The problem is that we still have little understanding of what it is and how it works. This is not an encephalogram, although it looks like a sound recording during speech, it is something else. So far, for us, this is mostly noise that we cannot decode.

So far, for us, this is mostly noise that we cannot decode.

Although we have little understanding of how the brain works, this does not prevent us from claiming that we can already read thoughts, and this reading is based on correlation. Correlation, as you know, does not mean causation, so any correlation that can be captured, we use in such interfaces.

What are the pig and monkey thinking about?

Animals also have thoughts. You've probably heard of Elon Musk's recent experiments? He implanted about a thousand electrodes into the pig's brain in order to read its thoughts. For implantation, he used a special robot that worked like a sewing machine and literally stitched the animal's brain. To understand the experiment, you need to know at least a little about the structure of the brain of a pig. There are different regions in the brain representing different parts of the body. This, by the way, was known even before Elon Musk. So, the pig's brain is about 70% of the piglet, so, naturally, she thinks about what her piglet perceives. Elon Musk has a more ambitious goal: he wants to eventually repeat the experiment on people and learn how to read people's thoughts.

Elon Musk has a more ambitious goal: he wants to eventually repeat the experiment on people and learn how to read people's thoughts.

I have a positive attitude to this plan, because I myself have been doing this for many years: working on brain-computer or brain-machine interfaces. The idea is that we implant many electrodes in the brain (and the more the better), record multi-channel activity, decode it and send it to an external device, such as a mechanical arm, which moves at the behest of your thought. A mechanical arm can have sensors. For example, she feels various objects, and these sensations of a mechanical hand are transmitted to the brain, to the sensory areas of the brain, and cause tactile sensations. This program works well.

A monkey with a Neuralink chip in his brain plays video games. Photo: Neuralink/Ferrari Press/East News

Back in the 1970s, the Soviet Union thought about the development of bioelectric prostheses and created a myoelectric prosthetic arm. Viktor Semenovich Gurfinkel and his colleagues Tsetlin and Gelfand created a prosthesis that was controlled by the electrical activity of muscles, and a person with an amputation could use such a prosthesis.

Viktor Semenovich Gurfinkel and his colleagues Tsetlin and Gelfand created a prosthesis that was controlled by the electrical activity of muscles, and a person with an amputation could use such a prosthesis.

I have worked with monkeys for a long time. In our experiments, the monkeys had the ultimate goal of getting orange juice. But for this it was necessary to work hard. The monkey sat with a joystick in front of the screen and played an exciting game where she had to move the joystick and hit the targets. She did great with it. At the same time, we recorded the electrical activity of the brain, decoded it, and then, without using the joystick, the monkey could direct this cursor to different areas of the screen. We were helped by the fact that we were able to implant electrodes in different areas of the monkey's brain, representing the arms, legs, eyes, which are more responsible for mental activity. And in this way we read in some detail the thoughts - the motor intentions of the monkey. By the way, I think it would be useful for people as well. Let's say we go to a restaurant and get food for no reason...

By the way, I think it would be useful for people as well. Let's say we go to a restaurant and get food for no reason...

Monkeys, like us, think about the direction of movement. And it turns out that the direction of movement is very easy to read due to the activity of neurons. If you put an electrode into a computer, you will never understand how it works. And if you insert an electrode, roughly speaking, into the brain of a monkey, it turns out that the neurons are discharged, encoding the direction. For example, if a monkey moves its hand in one direction, then this neuron will be very active, and if in another, then it will be less active. Just by the activity of the neuron, we can decode the direction.

In fact, we have come a long way in the study of the brain: in the study of its individual networks, the properties of neurons, the channels that neurons have. So to say that we really don't know anything would be wrong. But as we accumulate knowledge, we need to know more and more, and this is like an infinite approximation.

The deaf will hear, the blind will see, the recumbent will walk

I think that before we learn how to decode, we will advance very significantly in the interfaces that send information to the brain. These kinds of devices stimulate the brain and cause sensations, and maybe even thoughts. Let's say that many people suffer from the fact that they are deprived of some senses, such as hearing. And in hearing prosthetics, we have advanced very far: hundreds of thousands of people around the world have received cochlear implants and with the help of them they hear again. The next task is more difficult: it is the restoration of vision for the blind. I think that in the next five to ten years there will be a significant advance: blind people will see again.

This is where the plasticity of the brain helps us. We insert an electrode, stimulate it, and this is a completely unusual signal for the brain, because normally it receives much more delicate signals. But if we stimulate and the brain thinks what we want from it, it will gradually plastically tune in to understanding this signal, and as a result, a person will acquire new sensations.

But if we stimulate and the brain thinks what we want from it, it will gradually plastically tune in to understanding this signal, and as a result, a person will acquire new sensations.

While reading a completely arbitrary thought is difficult, but certain simple thoughts are much easier. And this is very practical in relation to patients with brain lesions. Let's say a person has a stroke, he can't move his arm. There is a faint desire in his brain to move his hand, but he cannot do it. And with the help of the interface, we can amplify this desire. That is, firstly, we can record brain activity and capture signals associated with the desire to move the hand, and then we can send these signals to the exoskeleton that is attached to the hand, and we reproduce all the components of voluntary movement: first, brain activity, then its implementation in the form of movement. Thus, a person with a stroke gets the opportunity to train himself and gradually return to normal. It is already becoming part of the neurorehabilitation of such patients.

So far, not enough money is being invested in this, but the realization is gradually coming that it is in this direction that we need to move. Especially since brain diseases are becoming more and more of a problem, as human life expectancy increases and the brain ages, neurodegenerative diseases arise that lead to problems such as Parkinson's disease or dementia, and they need to be dealt with somehow. This is where neural interfaces come to the rescue.

Not only the impulse to move, but also abstract thoughts such as "I don't really like this person" can also be read in an experimental situation where you are shown pictures on a screen and watch how your brain reacts. But there are ethical issues here, because suddenly you would like to hide that you don’t like some person? And when they showed you the pictures on the screen, recorded the activity of the brain, then this thought of yours can no longer be hidden: “Yeah, you don’t like certain kinds of people, take note of that!” Such a device is possible. It will be analogous to a lie detector, but more advanced, based on a more detailed analysis of brain activity.

It will be analogous to a lie detector, but more advanced, based on a more detailed analysis of brain activity.

We have always tried to be pioneers in research, and in many cases what we did was the first time. For example, we created a mechanical hand that the monkey controlled, and this hand performed grasping movements: reach and grab. Then we gave the mechanical hand sensitivity: it touched external objects, we stimulated the brain, and the monkey felt these objects. Then we said: "Well, we have done enough work with the hand, let's try to decode walking." They decoded walking, which, by the way, was repeated by Elon Musk on a pig, but we did it on a monkey. Then we said: “Well, well, is it possible to restore some spatial encodings of the brain?” And we did an experiment in which a monkey rode around the room on a cart and guided its movements with brain signals.

What's next? It is believed that a completely insurmountable task is the treatment of people with spinal cord injuries: if the spinal cord is cut, then it does not germinate again. It is on this problem that our efforts are directed at the moment. While we are taking the first steps in this area: recording brain activity and directing it to a spinal cord stimulator, which helps those fibers that have not yet been torn to become functional. Indeed, we see good results. But ideally, when many disciplines converge here, perhaps we will achieve that the spinal cord regenerates and such people will be able to walk again.

It is on this problem that our efforts are directed at the moment. While we are taking the first steps in this area: recording brain activity and directing it to a spinal cord stimulator, which helps those fibers that have not yet been torn to become functional. Indeed, we see good results. But ideally, when many disciplines converge here, perhaps we will achieve that the spinal cord regenerates and such people will be able to walk again.

Forgetting is impossible to remember

A time machine in the nose: how smells awaken our memory

How a person turns off natural selection

The site may use materials from Facebook and Instagram Internet resources, owned by Meta Platforms Inc., which is prohibited on territory of the Russian Federation

-

The future is already here

-

Other tags

Tell your friends

-

- Science vs nature

Scientists have edited genes to make beer taste better

-

- Excavations

- What was before

Shrine with evidence of unknown rituals found in Egyptian temple

-

- Edible / Inedible

- Human device

- social animal

Study: Vegetarians are more likely to become depressed than meat eaters

-

- energy transition

Scientists of Tomsk Polytechnic University have found an uninterrupted way to get cheap "green" hydrogen

-

- What was before

In the DNA of a 7th-century girl from English Kent, 33% of West African genes were found

-

Sergey Korsakov / @serg_korsakov / Roscosmos

Russian cosmonaut shared fantastic photos from orbit

-

Illustration: Irina Lutseva

What will we eat in the future?

-

East News

The Large Hadron Collider accelerates to an unprecedented level of energy

-

Shutterstock

Hacking with penetration: biologists filmed for the first time how a virus infects a cell

-

Volland et al.

/ Science, 2022

/ Science, 2022 Largest bacterium found She's as long as an eyelash

Do you want to be aware of the latest developments in science?

Leave your email and subscribe to our newsletter

Your e-mail

By clicking on the "Subscribe" button, you agree to the processing of personal data

Meta* created a neural network that reads a person's thoughts by brain activity / Skillbox Media

#news

- 0

Its accuracy was 73%.

Vkontakte Twitter Telegram Copy linkDmitry Zverev

Lover of science fiction and technological progress. He combines well an abstruse techie and a refined humanitarian. He writes about IT and enjoys it.

He combines well an abstruse techie and a refined humanitarian. He writes about IT and enjoys it.

AI engineers at Meta* have developed a neural network that converts human brain activity into speech. It can recognize 73% of the 793 most common words in the English language.

The work of the neural network from Meta. Source: Meta blogPreviously, similar experiments used sensors sewn inside the head to analyze brain activity. This process was painful, but remained the only one available.

Now, in order for the neural network to work, you need to connect external sensors - EEG (electroencephalography) and MEG (magnetoencephalography). They look like a foil cap for an encephalogram. After that, the system starts immediately.

Developers from Meta* say that their neural network will help people who suffer from brain injuries and lose speech and other communication skills. Every year, 69 million people suffer from such diseases.

Every year, 69 million people suffer from such diseases.

Word recognition is the company's first step towards its main goal. She plans to develop a neural network in the direction of generating words based on the work of the brain. Such discoveries will allow patients with brain injuries to communicate with people in a familiar format, and developers will be able to use this as a new way to interact with computers.

Employees of the company say that they want to show the scientific community what opportunities AI opens up, especially for understanding how the brain works.

Researchers from Meta* wrote a large scientific paper and posted it in the public domain.

See also:

* The court decision prohibited “the activities of Meta Platforms Inc. on the sale of products - social networks Facebook and Instagram on the territory of the Russian Federation on the grounds for carrying out extremist activities.