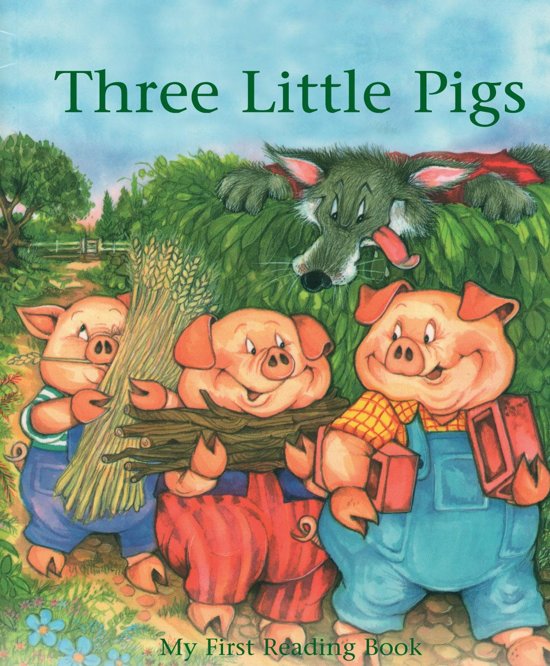

Is the three little pigs a fable

A Summary and Analysis of the ‘Three Little Pigs’ Fairy Tale – Interesting Literature

LiteratureBy Dr Oliver Tearle

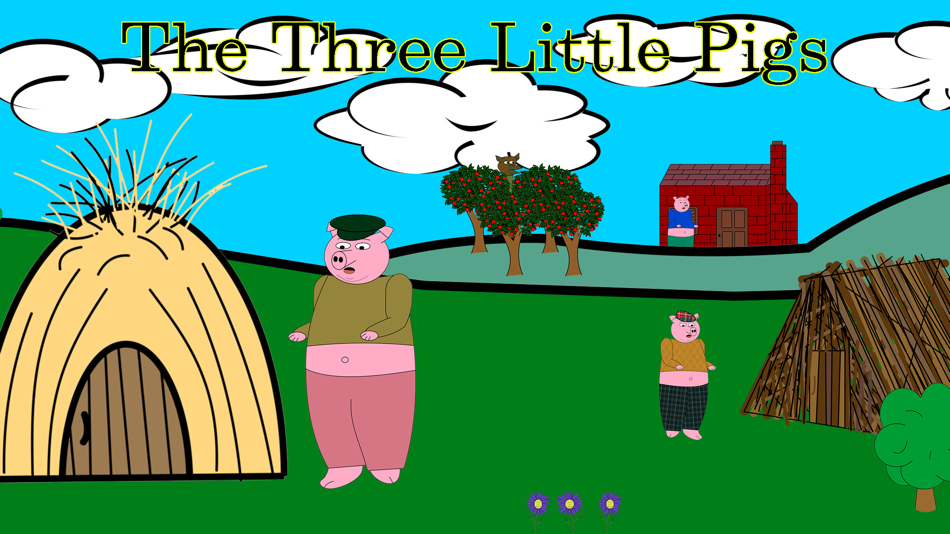

The anonymous fable or fairy tale of the Three Little Pigs is one of those classic anonymous tales which we hear, and have read to us, when we are very young. The fable contains many common features associated with the fairy tale, but there are some surprises when we delve into the history of this well-known story. Let us begin with a summary of the Three Little Pigs tale before proceeding to an analysis of its meaning and origins.

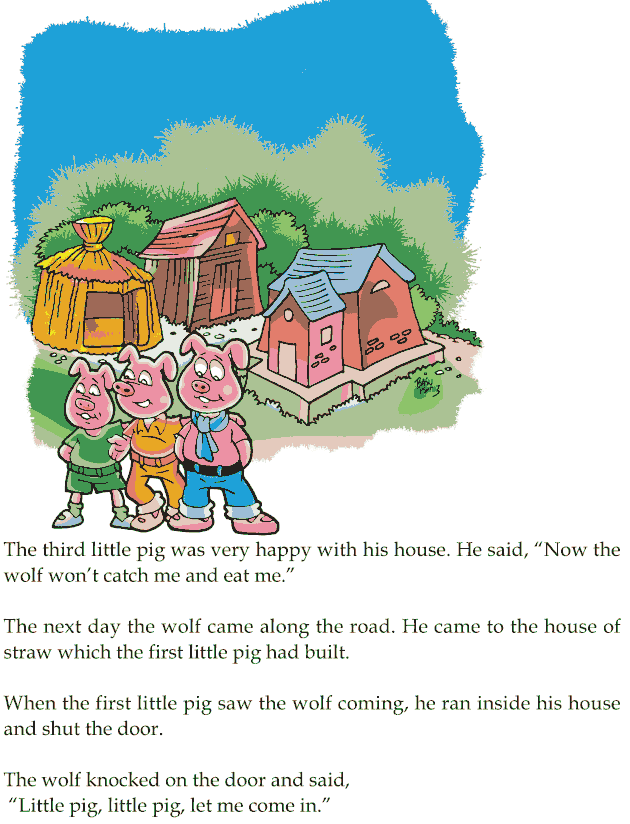

The Three Little Pigs: plot summary

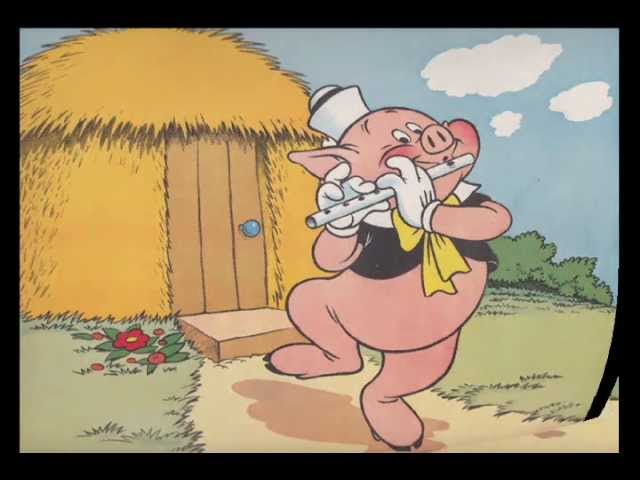

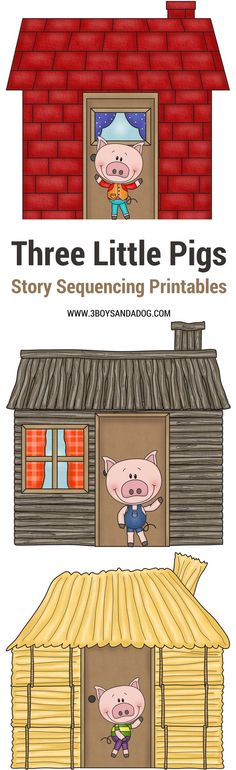

First, a brief summary of the tale as it’s usually told. An old sow has three pigs, her beloved children, but she cannot support them, so she sends them out into the world to make their fortune. The first (and oldest) pig meets a man carrying a bundle of straw, and politely asks if he might have it to build a house from.

The man agrees, and the pig builds his house of straw. But a passing wolf smells the pig inside the house.

He knocks at the door (how you can ‘knock’ at a door made of straw is a detail we’ll gloss over for now), and says: ‘Little pig! Little pig! Let me in! Let me in!’

The pig can see the wolf’s paws through the keyhole (yes, there’s a keyhole in this straw door), so he responds: ‘No! No! No! By the hair on my chinny chin chin!’

The wolf bares his teeth and says: ‘Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house down.’

He does as he’s threatened to do, blows the house down, and gobbles up the pig before strolling on.

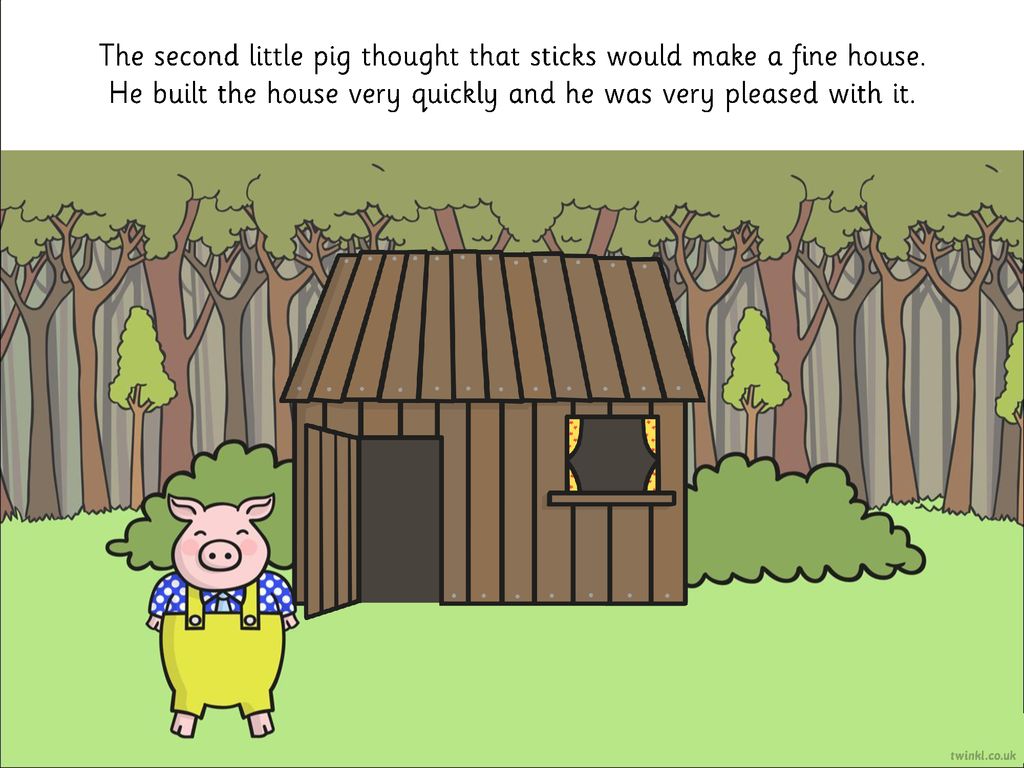

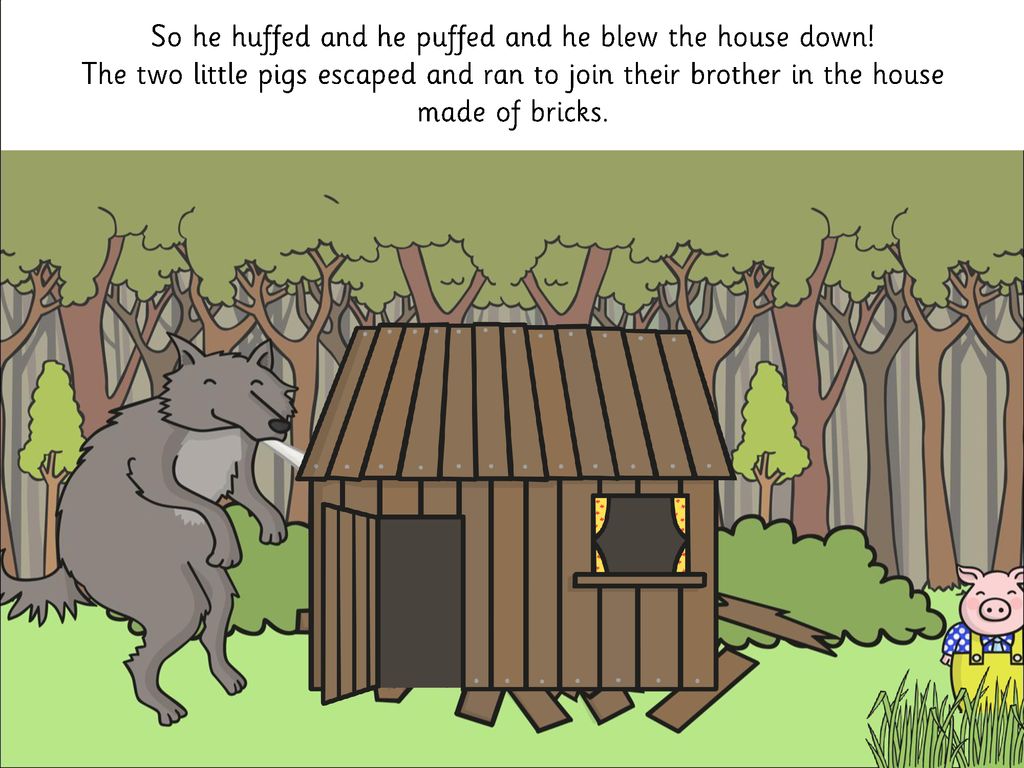

The second of the three little pigs, meanwhile, has met a man with a bundle of sticks, and has had the same idea as his (erstwhile) brother. The man gives him the sticks and he makes a house out of them. The wolf is walking by, smells the pig inside his house made of sticks, and he knocks at the door (can you ‘knock’ at a door made of sticks?), and says: ‘Little pig! Little pig! Let me in! Let me in!’

The pig can see the wolf’s ears through the keyhole (how can there – oh, forget it), so he responds: ‘No! No! No! By the hair on my chinny chin chin!’

The wolf bares his teeth and says: ‘Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house down. ’

’

He does as he’s threatened to do, blows the house down, and gobbles up the pig before strolling on.

Now, the final of the three little pigs – and the last surviving one – had met a man with a pile of bricks, and had had the same idea as his former siblings, and the man had kindly given him the bricks to fashion a house from. Now, you can guess where this is going.

The wolf is passing, and sees the brick house, and smells the pig inside it. He knocks at the door (no problem here), and says: ‘Little pig! Little pig! Let me in! Let me in!’

The pig can see the wolf’s great big eyes through the keyhole, so he responds: ‘No! No! No! By the hair on my chinny chin chin!’

The wolf bares his teeth and says: ‘Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house down.’

So the wolf huffs and puffs and huffs and puffs and huffs and puffs and keeps huffing and puffing till he’s out of puff. And he hasn’t managed to blow the pig’s house down! He thinks for a moment, and then tells the little pig that he knows a field where there are some nice turnips for the taking. He tells the pig where the field is and says he will come round at six o’clock the next morning and take him there.

He tells the pig where the field is and says he will come round at six o’clock the next morning and take him there.

But the little pig is too shrewd, so the next morning he rises at five o’clock, goes to the field, digs up some turnips and takes them back to his brick house. By the time the wolf knocks for him at six, he is already munching on the turnips. He tells the wolf he has already been and got them. The wolf is annoyed, but he comes up with another plan, and tells the wolf that he knows of some juicy apples on a tree in a nearby garden, and says he will knock for the pig the next morning at five o’clock and personally show him where they are.

The little pig agrees, but rises the next morning before four o’clock, and goes to the garden to pick some apples. But the wolf has been fooled once and isn’t about to be fooled twice, so he heads to the apple tree before five and catches the pig up the tree with a basket of apples. The pig manages to escape by throwing the wolf an apple to eat, but throwing it so far away that by the time the wolf has fetched it and returned, the little pig has escaped with his basket and gone home to his brick house.

The wolf tries one final time. He invites the little pig to the fair with him the next day, and the pig agrees; but he heads to the fair early on, buys a butter churn, and is returning home when he sees the big bad wolf on the warpath, incandescent with rage at having been thwarted a third time. So the pig hides in the butter churn and ends up rolling down the hill towards the wolf. The pig squeals in fear as he rolls, and the sound of the squealing and the speed of the churn rolling towards him terrifies the wolf, and he tucks tail and runs away.

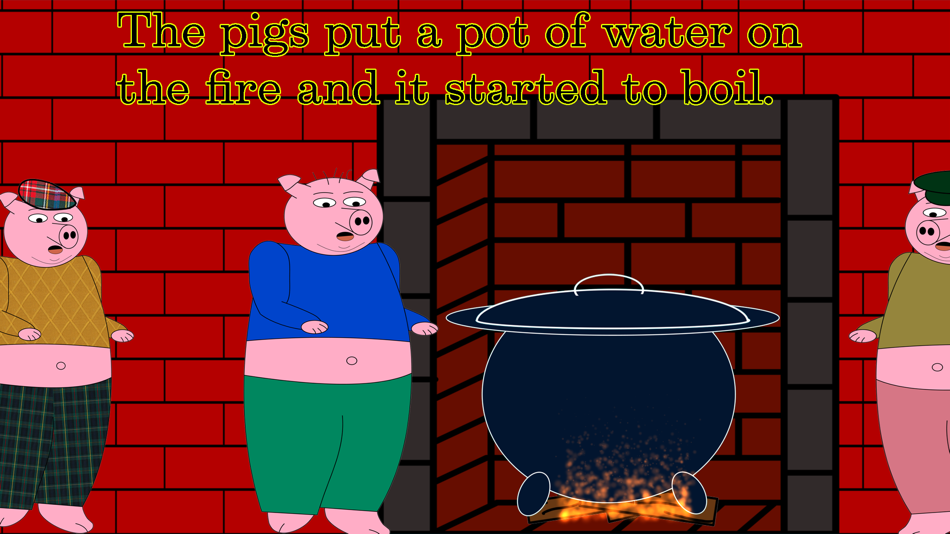

The next day, the wolf shows up at the little pig’s house, to apologise for not accompanying him to the fair the day before. He tells the pig that a loud, scary thing was rolling down a hill towards him. When the pig tells him that it must have been him inside the butter churn, the wolf loses his patience, and climbs on the roof, determined to climb down the chimney into the little pig’s house and eat him. But the pig has a pot of water boiling under the chimney, and when the wolf drops down into the house, he plops straight into the boiling hot water. The little pig puts the lid on the pot and cooks the wolf and then eats him for supper!

The little pig puts the lid on the pot and cooks the wolf and then eats him for supper!

The Three Little Pigs: analysis

We all know these essential features of the story: the three little pigs, the big bad wolf. Yet neither of these is an essential feature of the story, or hasn’t been at some point or other in the fable’s history. In one version – the earliest published version, from English Forests and Forest Trees, Historical, Legendary, and Descriptive (1853) – the little pigs were actually little pixies, and the wolf was a fox; the three houses were made of wood, stone, and iron. In another version, the Big Bad Wolf was actually a Big Kind Wolf. In at least one telling, the middle pig builds his house out of furze (i.e. gorse, a kind of shrub) rather than sticks.

As the Writing in Margins blog observes, an 1877 article published in Lippincott’s detailing folklore of African Americans in the southern United States outlines a story involving seven little pigs, which contains many of the details we associate with the Three Little Pigs tale, including the chimney-fire-pot finale and the chinny-chin-chinning. Joel Chandler Harris’ 1883 collection Nights with Uncle Remus contains a similar tale (featuring six pigs rather than three), suggesting that the tale was part of African-American folklore in the nineteenth century. Was the tale related to race relations in the United States during the antebellum (and immediate postbellum) era?

Joel Chandler Harris’ 1883 collection Nights with Uncle Remus contains a similar tale (featuring six pigs rather than three), suggesting that the tale was part of African-American folklore in the nineteenth century. Was the tale related to race relations in the United States during the antebellum (and immediate postbellum) era?

Perhaps, although it’s worth noting there were also Italian versions of the tale in circulation around the same time (with three geese rather than three pigs). The definitive English version – with all of the features of the story outlined in the plot summary above – appears to have made its debut in print only in 1886, in James Orchard Halliwell’s Nursery Rhymes of England.

This was a sort of hybrid version of the various tellings of the story in circulation, incorporating aspects of the Italian, African-American, and English versions. We recommend the Writing in Margins post linked to above for more information on the evolution of the story. Among other fascinating insights, the author suggests that the ‘pixies’ version of the tale arose from a mishearing of the Devon dialect word for pig, ‘pigsie’, as ‘pixie’. Certainly, no other version of the Three Little Pigs contains pixies, and the pixies in the story behave unlike the pixies found in other stories from English folklore.

Among other fascinating insights, the author suggests that the ‘pixies’ version of the tale arose from a mishearing of the Devon dialect word for pig, ‘pigsie’, as ‘pixie’. Certainly, no other version of the Three Little Pigs contains pixies, and the pixies in the story behave unlike the pixies found in other stories from English folklore.

1886 is rather late for the tale (as we now know it) to be making its debut in print. It feels much older, especially since it contains so many features we commonly associate with fairy tales and children’s stories. Indeed, it’s thought that the story is considerably older, and was perhaps circulated orally before it finally made its way into published books. Certainly, despite these slight differences between disparate versions of the tale, the raw narrative elements are those we are used to finding in fairy tales.

The rule of three – a common plot feature in classic fairy tales – is there several times over in the fable of the Three Little Pigs. There are three little pigs; there are three houses; the wolf tries to trick the last of the three pigs three times. In each case, the third instance acts as the decisive one: the first two pigs are eaten, but the third survives; the first two houses are insufficient to withstand the wolf, but the third is able to; and the third trick played by the wolf proves his ultimate undoing, since it is the last straw (no pun intended) which makes him erupt in rage and go on the offensive, with devastating consequences (for him).

There are three little pigs; there are three houses; the wolf tries to trick the last of the three pigs three times. In each case, the third instance acts as the decisive one: the first two pigs are eaten, but the third survives; the first two houses are insufficient to withstand the wolf, but the third is able to; and the third trick played by the wolf proves his ultimate undoing, since it is the last straw (no pun intended) which makes him erupt in rage and go on the offensive, with devastating consequences (for him).

This helps to build a sense of narrative tension, even if we suspect we know where the tale is going. And of course, there is a delicious irony (delicious in more than one sense) in the pig eating the wolf at the end of the fable, rather than vice versa.

But if fables are meant to have a moral message to impart, what is the meaning of the Three Little Pigs tale? In the last analysis, it seems to be that plucky resourcefulness and careful planning pay off, and help to protect us from harm. There’s also a degree of self-sufficiency: the mother cannot look after the three little pigs, so they must stand on their own two (or four) feet and make their own way in the world. (This is another popular narrative device in fairy tales: the hero must absent themselves from home early on and go out into the world alone.)

There’s also a degree of self-sufficiency: the mother cannot look after the three little pigs, so they must stand on their own two (or four) feet and make their own way in the world. (This is another popular narrative device in fairy tales: the hero must absent themselves from home early on and go out into the world alone.)

Of course, the third little pig survives not just by standing on his own feet but by thinking on his feet, too: it’s his quick thinking that enables him to outwit the wolf, himself not exactly a simpleton, even if he isn’t the sharpest straw in the hay-bale.

The author of this article, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others, The Secret Library: A Book-Lovers’ Journey Through Curiosities of History and The Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

Image: via Wikimedia Commons.

Like this:

Like Loading. ..

..

Tags: Analysis, Animal Fables, Children's Literature, Fairy Tales Analysis, Origins, Summary, Three Little Pigs

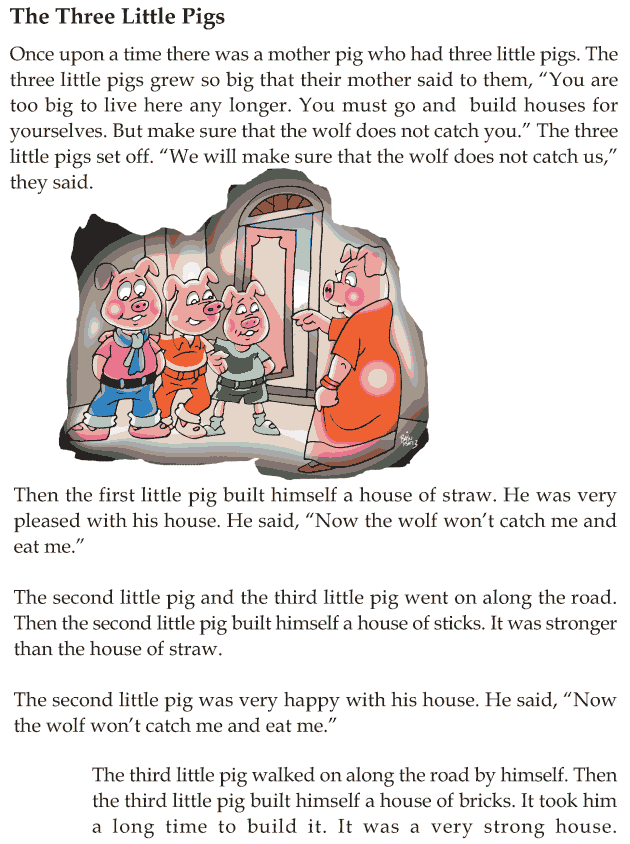

The Three Little Pigs

| Once

upon a time there were three little pigs, who left their mummy and daddy

to see the world.

All summer long, they roamed through the woods and over the plains, playing games and having fun. None were happier than the three little pigs, and they easily made friends with everyone. Wherever they went, they were given a warm welcome, but as summer drew to a close, they realized that folk were drifting back to their usual jobs, and preparing for winter. Autumn came and it began to rain. The three little pigs started to feel they needed a real home. Sadly they knew that the fun was over now and they must set to work like the others, or they'd be left in the cold and rain, with no roof over their heads. They talked about what to do, but each decided for himself.  The

laziest little pig said he'd build a straw hut. The

laziest little pig said he'd build a straw hut.

"It will only take a day,' he said. The others disagreed. "It's too fragile," they said disapprovingly, but he refused to listen. Not quite so lazy, the second little pig went in search of planks of seasoned wood. "Clunk! Clunk! Clunk!" It took him two days to nail them together. But the third little pig did not like the wooden house. "That's not the way to build a house!" he said. "It takes time, patience and hard work to build a house that is strong enough to stand up to wind, rain, and snow, and most of all, protect us from the wolf!" The days went by, and the wisest little pig's house took shape, brick by brick. From time to time, his brothers visited him, saying with a chuckle. "Why are you working so hard? Why don't you come and play?" But the stubborn bricklayer pig just said "no".

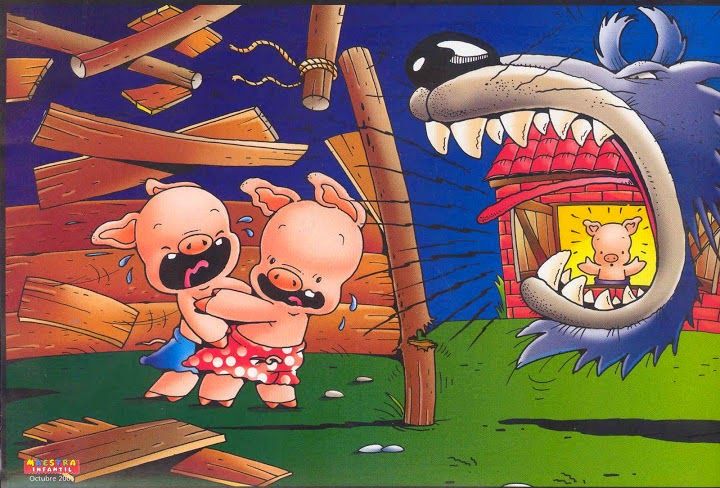

"I shall finish my house first. It must be solid and sturdy. And then I'll come and play!" he said. "I shall not be foolish like you! For he who laughs last, laughs longest!" It was the wisest little pig that found the tracks of a big wolf in the neighborhood. The little pigs rushed home in alarm. Along came the wolf, scowling fiercely at the laziest pig's straw hut. "Come out!" ordered the wolf, his mouth watering. I want to speak to you!" "I'd rather stay where I am!" replied the little pig in a tiny voice. "I'll make you come out!" growled the wolf angrily, and puffing out his chest, he took a very deep breath. Then he blew with all his might, right onto the house. And all the straw the silly pig had heaped against some thin poles, fell down in the great blast. Excited by his own cleverness, the wolf did not notice that the little pig had slithered out from underneath the heap of straw, and was dashing towards his brother's wooden house.  When he realized

that the little pig was escaping, the wolf grew wild with rage. When he realized

that the little pig was escaping, the wolf grew wild with rage.

"Come back!" he roared, trying to catch the pig as he ran into the wooden house. The other little pig greeted his brother, shaking like a leaf. "I hope this house won't fall down! Let's lean against the door so he can't break in!" Outside, the wolf could hear the little pigs' words. Starving as he was, at the idea of a two course meal, he rained blows on the door. "Open up! Open up! I only want to speak to you!" Inside, the two brothers wept in fear and did their best to hold the door fast against the blows. Then the furious wolf braced himself a new effort: he drew in a really enormous breath, and went ... WHOOOOO! The wooden house collapsed like a pack of cards. Luckily, the wisest little pig had been watching the scene from the window of his own brick house, and he rapidly opened the door to his fleeing brothers.  And

not a moment too soon, for the wolf was already hammering furiously on

the door. This time, the wolf had grave doubts. This house had a much more

solid air than the others. He blew once, he blew again and then for a third

time. But all was in vain. For the house did not budge an inch. The three

little pigs watched him and their fear began to fade. Quite exhausted by

his efforts, the wolf decided to try one of his tricks. He scrambled up

a nearby ladder, on to the roof to have a look at the chimney. However,

the wisest little pig had seen this ploy, and he quickly said. And

not a moment too soon, for the wolf was already hammering furiously on

the door. This time, the wolf had grave doubts. This house had a much more

solid air than the others. He blew once, he blew again and then for a third

time. But all was in vain. For the house did not budge an inch. The three

little pigs watched him and their fear began to fade. Quite exhausted by

his efforts, the wolf decided to try one of his tricks. He scrambled up

a nearby ladder, on to the roof to have a look at the chimney. However,

the wisest little pig had seen this ploy, and he quickly said.

"Quick! Light the fire!" With his long legs thrust down the chimney, the wolf was not sure if he should slide down the black hole. It wouldn't be easy to get in, but the sound of the little pigs' voices below only made him feel hungrier. "I'm dying of hunger! I'm going to try and get down." And he let himself drop. But landing was rather hot, too hot! The wolf landed in the fire, stunned by his fall.

The flames licked his hairy coat and his tail became a flaring torch. "Never again! Never again will I go down a chimney" he squealed, as he tried to put out the flames in his tail. Then he ran away as fast as he could. The three happy little pigs, dancing round and round the yard, began to sing. "Tra-la-la! Tra-la-la! The wicked black wolf will never come back...!" From that terrible day on, the wisest little pig's brothers set to work with a will. In less than no time, up went the two new brick houses. The wolf did return once to roam in the neighborhood, but when he caught sight of three chimneys, he remembered the terrible pain of a burnt tail, and he left for good. Now safe and happy, the wisest little pig called to his brothers. "No more work! Come on, let's go and play!" |

"Three Little Pigs" fairy tale by Sergei Mikhalkov

Once upon a time there were three little pigs in the world. Three brothers. All the same height round, pink, with the same cheerful ponytails.

Three brothers. All the same height round, pink, with the same cheerful ponytails.

Even their names were similar. The piglets were called: Nif-Nif, Nuf-Nuf and Naf-naf. All summer they tumbled in the green grass, basking in the sun, basked in the puddles.

But autumn has come.

The sun was no longer so hot, gray clouds stretched over yellowed forest.

- It's time for us to think about winter, - Naf-Naf once said to his brothers, waking up early in the morning. - I'm shivering from the cold. We may catch a cold. Let's build a house and winter together under one warm roof.

But his brothers didn't want to take the job. Much nicer in the last warm days to walk and jump in the meadow than to dig the ground and drag heavy stones.

- Have time! Winter is still far away. We will take a walk, - said Nif-Nif and rolled over his head.

- When necessary, I will build myself a house, - said Nuf-Nuf and lay down in puddle

- Me too, - added Nif-Nif.

- Well, as you wish. Then I will build my own house, - said Naf-Naf. - I won't wait for you.

It was getting colder and colder every day.

But Nif-Nif and Nuf-Nuf were in no hurry. They didn't even want to think about work. They were idle from morning to evening. All they did was play their pig games, jumping and somersaulting.

- Today we will take a walk, - they said, - and tomorrow in the morning we will take for the cause.

But the next day they said the same thing.

And only when a large puddle by the road began to cover in the morning thin crust of ice, the lazy brothers finally set to work.

Nif-Nif decided that it would be easier and most likely to make a house out of straw. Neither with without consulting anyone, he did so. By evening, his hut was ready.

Nif-Nif put the last straw on the roof and, very pleased with his house, sang merrily:

- You can get around half the world,

You will go around, you will go around,

You won't find a better home,

You won't find it, you won't find it!

Singing this song, he went to Nuf-Nuf.

Nuf-Nuf was also building a house not far away.

He tried to put an end to this boring and uninteresting business as soon as possible. At first, like his brother, he wanted to build a house out of straw. But then I decided that in such a house it would be very cold in winter. The house will be stronger and warmer if it is built from branches and thin rods.

So he did.

He drove stakes into the ground, intertwined them with rods, piled dry leaves, and by evening the house was ready.

Nuf-Nuf proudly walked around him several times and sang:

- I have a nice house,

New home, solid home,

I'm not afraid of rain and thunder,

Rain and thunder, rain and thunder!

Before he could finish the song, Nif-Nif ran out from behind a bush.

- Well, your house is ready! - said Nif-Nif brother. - I said that we and we'll do it alone! Now we are free and we can do whatever we would like!

- Let's go to Naf-Naf and see what kind of house he built for himself! - said Nuf-nuf. - We haven't seen him for a long time!

- We haven't seen him for a long time!

- Let's go and see! - agreed Nif-Nif.

And both brothers, very pleased that they didn't need anything else take care, hid behind the bushes.

Naf-Naf has been busy building for several days now. He coached stones, kneaded clay, and now slowly built himself a reliable, durable house, in which could be sheltered from wind, rain and frost.

He made a heavy oak door with a bolt in the house to keep the wolf out neighboring forest could not climb to it.

Nif-Nif and Nuf-Nuf found their brother at work.

- What are you building? - in one voice shouted the surprised Nif-Nif and Nuf-nuf. - What is it, a house for a piglet or a fortress?

- Piglet's house should be a fortress! - calmly answered them Naf-Naf, continuing to work.

- Are you going to fight with someone? - cheerfully grunted Nif-Nif and winked at Nuf-Nuf.

And both brothers were so merry that their squeals and grunts carried far across the lawn.

And Naf-Naf, as if nothing had happened, continued to lay the stone wall of his at home, humming a song under his breath:

- Of course, I'm smarter than everyone,

Smarter than everyone, smarter than everyone!

I build a house of stones,

From stones, from stones!

No animal in the world,

Cunning beast, terrible beast,

Will not break through this door,

This door, this door!

- What animal is he talking about? - asked Nif-Nif from Nuf-Nuf.

- What animal are you talking about? - Nuf-Nuf asked Naf-Naf.

- I'm talking about the wolf! - answered Naf-Naf and laid another stone.

- Look how afraid he is of the wolf! - said Nif-Nif.

- He's afraid of being eaten! - added Nuf-Nuf.

And the brothers cheered even more.

- What kind of wolves can be here? - said Nif-Nif.

- There are no wolves! He's just a coward! - added Nuf-Nuf.

And they both began to dance and sing:

- We are not afraid of the gray wolf,

Gray wolf, gray wolf!

Where do you go, stupid wolf,

Old wolf, dire wolf?

They wanted to tease Naf-Naf, but he didn't even turn around.

- Let's go, Nuf-Nuf, - said then Nif-Nif. - We have nothing to do here!

And two brave brothers went for a walk.

On the way they sang and danced, and when they entered the forest, they made such a noise, that they woke up the wolf, who was sleeping under the pine tree.

- What's that noise? - An angry and hungry wolf grumbled displeasedly and galloped to the place from which came the squealing and grunting of two small, stupid piglets.

- Well, what kind of wolves can be here! - said at this time Nif-Nif, who saw wolves only in pictures.

- Here we will grab him by the nose, he will know! - added Nuf-Nuf, who I have never seen a live wolf either.

- Let's knock down, and even tie, and even with a foot like this, like this! - boasted Nif-Nif and showed how they would deal with the wolf.

And the brothers rejoiced again and sang:

- We are not afraid of the gray wolf,

Gray wolf, gray wolf!

Where do you go, stupid wolf,

Old wolf, dire wolf?

And suddenly they saw a real live wolf!

He was standing behind a large tree, and he looked so scary, such evil eyes and such a toothy mouth that Nif-Nif and Nuf-Nuf have their backs a chill ran through and thin ponytails trembled finely.

The poor piglets couldn't even move for fear.

The wolf prepared to jump, snapped his teeth, blinked his right eye, but the piglets suddenly came to their senses and, squealing throughout the forest, rushed to their heels.

They have never run so fast!

Sparkling with their heels and raising clouds of dust, the piglets rushed each to their own home.

Nif-Nif was the first to reach his thatched hut and barely managed to slam the door in front of the wolf's nose.

- Unlock the door now! the wolf growled. - Otherwise, I'll break it!

- No, - grunted Nif-Nif, - I won't unlock it!

The breath of a terrible beast was heard outside the door.

- Unlock the door now! the wolf growled again. - Otherwise, I will blow like that, that your whole house will shatter!

But Nif-Nif, out of fear, could no longer answer anything.

Then the wolf began to blow: "F-f-f-w-w-w!"

Straws flew from the roof of the house, the walls of the house shook.

The wolf took another deep breath and blew a second time: "F-f-f-w-w-w!"

When the wolf blew for the third time, the house flew in all directions, as if a hurricane hit him.

The wolf snapped his teeth in front of the little piglet's snout. But Nif-Nif deftly dodged and rushed to run. A minute later he was at the door. Nuf-nufa.

As soon as the brothers had locked themselves in, they heard the wolf's voice:

- Well, now I'll eat you both!

Nif-Nif and Nuf-Nuf looked at each other in fear. But the wolf is very tired and therefore decided to go to the trick.

- I changed my mind! - he said so loudly that he could be heard in the house. - I I won't eat those skinny piglets! I better go home!

- Did you hear? - asked Nif-Nif from Nuf-Nuf. - He said he wouldn't. we have! We are skinny!

- It's very good! - Nuf-Nuf said and immediately stopped trembling.

The brothers became cheerful, and they sang as if nothing had happened:

- We are not afraid of the gray wolf,

Gray wolf, gray wolf!

Where do you go, stupid wolf,

Old wolf, dire wolf?

And the wolf didn't even think of going anywhere. He just stepped aside and hid. He was very funny. He could hardly restrain himself from laugh. How cleverly he deceived two stupid little pigs!

He just stepped aside and hid. He was very funny. He could hardly restrain himself from laugh. How cleverly he deceived two stupid little pigs!

When the piglets were completely calm, the wolf took the sheep's skin and carefully crept up to the house.

At the door he covered himself with skin and knocked softly.

Nif-Nif and Nuf-Nuf were very frightened when they heard a knock.

- Who is there? they asked, their tails shaking again.

- It's me-me-me - poor little sheep! - in a thin, alien voice squeaked wolf. - Let me spend the night, I strayed from the herd and very tired!

- Let me in? - the kind Nif-Nif asked his brother.

- You can let the sheep go! - Nuf-Nuf agreed. - A sheep is not a wolf!

But when the pigs opened the door, they saw not a sheep, but all that or a toothy wolf. The brothers slammed the door and leaned on it with all their might, so that the terrible beast could not break into them.

The wolf got very angry. He failed to outsmart the pigs! He dropped off his sheepskin and growled:

He failed to outsmart the pigs! He dropped off his sheepskin and growled:

- Wait a minute! There will be nothing left of this house!

And he began to blow. The house leaned a little. The wolf blew a second, then a third, then a fourth time.

Leaves were falling from the roof, the walls were trembling, but the house was still standing.

And, only when the wolf blew for the fifth time, the house staggered and collapsed. Only one door still stood for some time in the middle of the ruins.

The pigs ran away in terror. From fear, their legs were taken away, every bristle trembled, noses were dry. The brothers rushed to the house of Naf-Naf.

The wolf overtook them with huge leaps. Once he almost grabbed Nif-Nifa by the back leg, but he pulled it back in time and added speed.

The wolf also pressed on. He was sure that this time the pigs from him were not run away.

But he was out of luck again.

The piglets quickly rushed past a large apple tree without even hitting it. BUT the wolf did not have time to turn and ran into an apple tree, which showered him with apples. One hard apple hit him between the eyes. A big shot jumped up at the wolf on the forehead.

BUT the wolf did not have time to turn and ran into an apple tree, which showered him with apples. One hard apple hit him between the eyes. A big shot jumped up at the wolf on the forehead.

And Nif-Nif and Nuf-Nuf, neither alive nor dead, ran up to the house at that time Naf-nafa.

The brother quickly let them into the house. The poor pigs were so scared that they couldn't say anything. They silently rushed under the bed and hid there. Naf-Naf immediately guessed that a wolf was chasing them. But he had nothing to fear in his stone house. He quickly closed the door with a bolt, sat down on stool and sang loudly:

- No animal in the world,

Cunning beast, terrible beast,

Will not open this door,

This door, this door!

But just then there was a knock on the door.

- Who is knocking? - Naf-Naf asked in a calm voice.

- Open without talking! came the rough voice of the wolf.

- No matter how! And I don't think so! - Naf-Naf answered in a firm voice.

- Oh, yes! Well, hold on! Now I'll eat all three!

- Try it! - answered Naf-Naf from behind the door, without even getting up with his stools.

He knew that he and his brothers had nothing to fear in a solid stone house.

Then the wolf sucked in more air and blew as hard as he could!

But no matter how much it blows, not even the smallest stone moved out of place.

The wolf turned blue from the effort.

The house stood like a fortress. Then the wolf began to shake the door. But the door is not succumbed.

The wolf, out of anger, began to scratch the walls of the house with his claws and gnaw on stones, from which they were folded, but he only broke off his claws and ruined his teeth. The hungry and angry wolf had no choice but to get out.

But then he raised his head and suddenly noticed a large, wide pipe on roof.

- Aha! Through this pipe I will make my way into the house! - the wolf rejoiced.

He carefully climbed onto the roof and listened. The house was quiet.

The house was quiet.

"I'm still going to eat some fresh piglet today!" thought the wolf and licking his lips, climbed into the pipe.

But as soon as he began to descend the pipe, the piglets heard a rustle. BUT when soot began to pour on the lid of the boiler, smart Naf-Naf immediately guessed that than the case.

He quickly rushed to the cauldron, in which water was boiling on the fire, and plucked cover it.

- Welcome! - said Naf-Naf and winked at his brothers.

Nif-Nif and Nuf-Nuf have already completely calmed down and, smiling happily, looked at their smart and brave brother.

The piglets did not have to wait long. Black as a chimney sweep, wolf splashed right into the boiling water.

Never before had he been in so much pain!

His eyes popped out on his forehead, all his hair stood on end.

With a wild roar, the scalded wolf flew up the chimney back to the roof, rolled down it to the ground, rolled over four times over his head, rode on his tail past the locked door and rushed into the woods.

And three brothers, three little pigs, looked after him and rejoiced, that they so cleverly taught the evil robber a lesson.

And then they sang their cheerful song:

- Even if you go around half the world,

You will go around, you will go around,

You won't find a better home,

You won't find it, you won't find it!

No animal in the world,

Cunning beast, terrible beast,

Will not open this door,

This door, this door!

The wolf from the forest never,

Never never

Will not return to us here,

To us here, to us here!

Since then, the brothers began to live together, under one roof.

That's all we know about the three little pigs - Nif-Nifa, Nuf-Nufa and Naf Nafa.

First published under the title "The Tale of the Three Little Pigs" in the newspaper "Pionerskaya Pravda" (1936, April 16). The first edition as a separate book has the subtitle: "Text and drawings by the W. Disney studio. Translated and processed by S. Mikhalkov" (M.-L., 1936). The book is illustrated with individual frames of the wonderful film by W. Disney. The plot of the tale is borrowed from English folklore.

Disney studio. Translated and processed by S. Mikhalkov" (M.-L., 1936). The book is illustrated with individual frames of the wonderful film by W. Disney. The plot of the tale is borrowed from English folklore.

"The ways in which Mikhalkov's books sometimes reach a foreign reader are amazing. Thus, in 1968 in Edinburgh," critic B. Begak wrote, "an English edition of The Three Little Pigs was published, translated ... from German (apparently , from Berlin edition 1966). No matter how ridiculous it is to translate from German into English a Russian book that has an Anglo-American primary source, this paradox can serve as a kind of indirect proof of the originality of the Mikhalkov version of the fairy tale. "(Begak B. Mikhalkov in foreign literature. - In the book: Uncle Styopa - Mikhalkov. M., Det. lit., 1974, pp. 105-106).

The book went through more than twenty editions. Illustrated by K. Rotov, S. Kalachev, I. Offengenden and others. Based on the fairy tale, the author wrote a play: "Three little pigs and a gray wolf. "

"

Why does the pig have a name? | Papmambuk

In the middle of the last century, the well-known child psychotherapist and psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim wrote the book On the Benefits of Magic, which interprets the plots of European folk tales. In particular, the English fairy tale "Three Little Pigs" ("Three Little Pigs").

Three pigs, according to Bettelheim, symbolize different stages of a child's development.

The life of a small child, according to the ideas of psychoanalysts, is subject to the principle of pleasure: I strive for what gives me pleasure. Getting pleasure is the main driving stimulus of life. At the same time, I demand pleasure immediately and do not understand, do not accept any delay in receiving pleasure.

With age, this principle of existence must be replaced by another: the child must learn to act on the principle of reality. Each of us wants to enjoy life. But the satisfaction of our desires may not always be instantaneous. Moreover, most often it is delayed. And, striving for pleasure, we must reckon with circumstances and with other people. Pleasure is not given to us just like that: in order to enjoy it, you need to make an effort.

Moreover, most often it is delayed. And, striving for pleasure, we must reckon with circumstances and with other people. Pleasure is not given to us just like that: in order to enjoy it, you need to make an effort.

This difficult transition from the pleasure principle to the reality principle, according to Bruno Bettelheim, is the story of the fairy tale "Three Little Pigs".

Two little pigs build their house from fragile materials: one from straw, the other from twigs. Both try to spend as little time and effort on this activity as possible and leave it at the first opportunity - to play. Two little pigs do not want (cannot) think about the future, about possible dangers. The main thing in their life is the momentary and quick satisfaction of emerging desires. True, the tale notes that the second piglet is still trying to build a house from something more solid than the younger one - there are signs of growing up! But they are not yet sufficiently expressed.

Only the third, oldest, piglet can already restrain his desires, can postpone the game for the sake of business. He is able to foresee the future and possible dangers. The older pig is even able to predict the behavior of the wolf. The wolf is an enemy, an insidious stranger who wants to seduce the pig, lure him into a trap. The wolf personifies everything asocial and unconscious and therefore has a terrible destructive power.

He is able to foresee the future and possible dangers. The older pig is even able to predict the behavior of the wolf. The wolf is an enemy, an insidious stranger who wants to seduce the pig, lure him into a trap. The wolf personifies everything asocial and unconscious and therefore has a terrible destructive power.

But the little pig is able to resist him - as our consciousness is capable of resisting our own unconscious impulses. The piglet, with its reasonable, conscious actions, frustrates the plans of the enemy, far superior to him in ferocity and cruelty.

In each of us, says Bettelheim, live a wolf and a pig. And our psyche is the place of their competition in strength. The fairy tale informs the child about this in a figurative, fascinating form.

The actions of the piglets and the wolf are described tensely and dynamically: here the piglet is running away from the wolf, the wolf is chasing him. Here is a pig hiding in a house. The wolf puffs out his cheeks, blows, destroys the fragile pig house. .. All actions are understandable to the child, everything is imaginable - including the actions of the wolf. After all, the baby knows from his own experience what it means to destroy houses (for example, houses made of cubes). Therefore, he follows what is happening with awe and delight.

.. All actions are understandable to the child, everything is imaginable - including the actions of the wolf. After all, the baby knows from his own experience what it means to destroy houses (for example, houses made of cubes). Therefore, he follows what is happening with awe and delight.

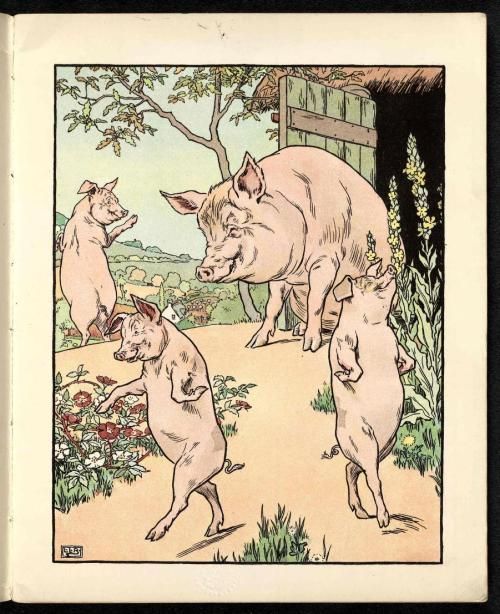

In an English folk tale, an evil wolf not only destroys a straw house, but also eats its owner, the first pig. Then he destroys the house of branches and eats the second pig. Only the third piglet manages to escape. Bettelheim believes that the defeat and disappearance of the first two piglets in the perception of the child is compensated by the fate of the third piglet: the first two, younger piglets must certainly disappear, as they represent the two early stages of development that the child must overcome.

The third piglet is perceived by the child as a successful transformation of the first two: if we want to rise to a higher level of development, we must part with early forms of behavior. The fact that the pigs in the folk tale do not have names helps the child to identify them with each other - and with himself. And "save" from the wolf in the form of the third pig.

The fact that the pigs in the folk tale do not have names helps the child to identify them with each other - and with himself. And "save" from the wolf in the form of the third pig.

The wolf fails to eat the third pig. This piglet - due to the fact that he is smarter and more mature than the first two - knows how to defend himself from the enemy. For the child listener, this is a comforting prospect: growing up is not bad at all.

True, in an English fairy tale, a solid house does not give an absolute sense of security: the wolf does not stop trying to eat the pig. He knows that the piglet is greedy for tasty things, and he tries to lure him out of the safe stone house: first he invites him to go to the garden where the turnip has grown (and the owner is away), then to the garden where the apples have ripened, and finally to the fair, where there are a lot of temptations. But the piglet does not give in. He unravels the wolf's tricks and each time manages to get ahead of the wolf.

Unable to deceive the pig, the wolf decides to climb into his house through the pipe. He expects that the pig does not suspect anything and calmly went to bed. But he guesses about the intrigues of the wolf, melts the fireplace at an inopportune time and puts a cauldron of boiling water on fire. The wolf that climbed into the chimney falls into this cauldron. The pig tightly closes the cauldron with a lid, and the wolf turns ... into boiled meat for the pig. Piglet, tying a napkin around his neck and armed with a knife and fork, dine on wolf meat. (There is nothing incredible about this, given that pigs are omnivores.)

Bettelheim states that children perceive such an ending as a happy one. After all, the wolf had eaten two little pigs before. When he himself becomes food for the piglet, this is just retribution. The child agrees with such punishment. After all, the wolf is definitely bad. Moreover, the wolf personifies the bad that exists in the child himself. After all, a small child is familiar with the desire to destroy (as already mentioned, he watches the wolf with mixed feelings when he destroys the piglets' houses). But even a small child from some point is already able to feel: such a desire can turn into trouble for the destroyer. This feeling, this “guess”, the tale of the three little pigs confirms: one cannot be a greedy “devourer”.

But even a small child from some point is already able to feel: such a desire can turn into trouble for the destroyer. This feeling, this “guess”, the tale of the three little pigs confirms: one cannot be a greedy “devourer”.

The fairy tale "Three Little Pigs" makes the child think about his behavior, but does it gradually, without any moralizing. The child is given the opportunity to draw his own conclusions. “Only such a position contributes to the proper maturation of the child. To tell him directly how to behave means to burden the fetters of childish immaturity with the slavish fetters of the dictates of adults, ”writes Bettelheim.

Therefore, one should speak with a child in the language of a fairy tale, and not in the language of moralizing.

***

The Soviet child was not familiar with the version of the fairy tale that Bruno Bettelheim analyzed in such detail. The "classic" version known to us belongs to Sergei Mikhalkov and is called "The Three Little Pigs". And this is a completely different story.

And this is a completely different story.

Pigs have names: Nif-Nif, Nuf-Nuf and Naf-Naf. And this author's decision leads to a semantic shift and a change in the plot.

Pigs that have names also have characters. The author - albeit in a few words - reports that Nif-Nif and Nuf-Nuf are frivolous and love to play. And Naf-Naf is serious and hardworking. That is, Mikhalkov's piglets have individuality. Compared to them, the piglets from the folk tale are “under-incarnated” shadows. But it is precisely because of this non-incarnation that they can "merge" with each other in the child's imagination. That is why their disappearance is not a tragedy for the reader. And the child easily (as it seems to Bettelheim) should switch to the third pig, with which he is identified. Moreover, in the disappearance of the first two pigs, as already mentioned, there is a deep meaning.

But letting a wolf eat a pig with a name and character is completely impossible - even if the pig is misbehaving. If the wolf in Mikhalkov's fairy tale had swallowed a piglet, this would have been perceived not as a logical consequence of unreasonable behavior, but as an adult's cruel treatment of a child (a piglet is a small child; a wolf is an adult, big and strong, who punishes the child). After all, the child-listener also often behaves badly or incorrectly. Is that what they eat? And in the fairy tale, moreover, bad behavior lies in the fact that the piglets want to play - that is, they do what is characteristic of the child and what is organic for him. Such a turn of events would be truly terrible. And it is unlikely that the child found the strength to perceive the tale as instructive: the image of cruelty has the property of capturing attention, fixing it on itself - that is, it is a very strong experience that obscures everything else.

If the wolf in Mikhalkov's fairy tale had swallowed a piglet, this would have been perceived not as a logical consequence of unreasonable behavior, but as an adult's cruel treatment of a child (a piglet is a small child; a wolf is an adult, big and strong, who punishes the child). After all, the child-listener also often behaves badly or incorrectly. Is that what they eat? And in the fairy tale, moreover, bad behavior lies in the fact that the piglets want to play - that is, they do what is characteristic of the child and what is organic for him. Such a turn of events would be truly terrible. And it is unlikely that the child found the strength to perceive the tale as instructive: the image of cruelty has the property of capturing attention, fixing it on itself - that is, it is a very strong experience that obscures everything else.

Therefore, there is something terrible in the fairy tale (the wolf is still terrible), but it is weakened. The wolf never achieves its goal and in the end suffers a complete defeat, falling into the cauldron.![]() However, here the author follows the principle of humanism: the scalded wolf safely jumps out of the cauldron and runs into the forest. The main result of the struggle: the wolf no longer annoys the piglets. About the pigs, it is reported that they understood everything, were re-educated and began to live together. Absolutely happy ending.

However, here the author follows the principle of humanism: the scalded wolf safely jumps out of the cauldron and runs into the forest. The main result of the struggle: the wolf no longer annoys the piglets. About the pigs, it is reported that they understood everything, were re-educated and began to live together. Absolutely happy ending.

From the point of view of philosophy, the author's tale obviously loses depth in comparison with the folk tale. But in this case, if necessary, we can easily answer the disgusting school question: what is the story about and what does it teach? The answer is on the surface: you need to be hardworking, diligent, positive - like a Naf-Naf pig. In general, labor created man, and even a pig can do something decent.

When the content of a fairy tale is easily translated into the language of morality, it is no longer a fairy tale, but a fable. And if the "main idea" and "morality" were the main advantages of Mikhalkov's work, it would not be worth talking about him.

***

But put before us two versions of a fairy tale - folk and Mikhalkov's - which one will we choose for today's child?

I personally am Mikhalkovsky. With all my reverent attitude towards Bettelheim. Moreover, Bettelheim's book for me is a textbook on understanding fairy-tale material and the ability to measure it with the child's psyche.

For a child of two and a half - three years old, I will choose the Mikhalkov version, where funny piglets are described so colorfully and vividly; where they, having defeated the wolf, do not eat it, but sing a song. I think that the English folk tale was originally addressed not to small children, but to adults. When she entered the circle of children's reading, it was also not about toddlers, but about children who had reached at least five years of age, or even six years of age - the period when, on the one hand, the idea of the principle of reality becomes relevant, and on the other hand, there is a request for scary tales.

The shift made by Sergey Mikhalkov allowed the fairy tale about piglets to descend to the lower age level. The story has been redirected. Now it is best to read it to three-year-olds. And three-year-olds will most safely ignore the moralism of the Soviet version. For them - people with psychomotor intelligence and cognizing the world around them through movement - it is important that there are many exciting actions in the fairy tale. Pigs play, build houses, run away from the wolf, hide; the wolf breaks houses, climbs somewhere, falls somewhere and also runs away - and all this is recognizable, interesting, dynamic. This is a real adventure story, a thriller for the little ones. And a happy ending - an unconditional happy ending - is another confirmation of the stability of the world. No creature that has a name should disappear from it. No play-loving pig.

And I will also choose the Mikhalkov version for the very individualization of the images that the author carried out when retelling a folk tale.

Folklore can be considered the soil from which literature in general and children's literature in particular grew (this was brilliantly proved in their time by K. Chukovsky and S. Marshak). But modern literature cannot but take into account the new psychological demands of the reader. And these requests are connected with the awareness of one's own separateness, individuality and its value. Therefore, endowing the characters with individual characteristics and characters is the main trend in the development of a fairy tale in the 20th century.

As for the folk tale, it seems to me that it would be right and interesting to offer it for comparison with the Mikhalkov version for children of nine or ten years old. Why not an introduction to literary criticism?

Marina Aromshtam

The English folk tale described by Bruno Bettelheim has not been translated into Russian. Only her adapted retellings exist. So, for example, the Ripol Classic publishing house published the fairy tale The Three Little Pigs (illustrations by E.